Neil Percival Young was born November 12, 1945, in Toronto. His father, Scott Young, was a fledgling journalist who would find fame as a sportswriter, newspaper columnist, TV commentator, and writer of fiction. Neil’s mother, Edna “Rassy” Ragland, was, as Scott recalls in Neil and Me, “a good tennis player and golfer and all around noticeable young woman” when she caught his eye in Winnipeg. They married there on June 18, 1940, and moved to Toronto when Scott secured a job with the Canadian Press news agency. Their first child, Bob, was born April 27, 1942.

Scott Young remembers Neil—“Neiler” in the family parlance—as being smitten with music early on. In his crib, he would “jig to Dixieland even before he could stand up.” In 1949, the Youngs moved to Omemee, a small town in north Ontario that Neil would memorialize in his song “Helpless.” He led a happy and active existence there, fishing, catching turtles, watching TV, and playing with his train set. “Omemee’s a nice little town,” Young told Jimmy McDonough, author of Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography. “Sleepy little place. . . . Life was real basic and simple in that town. Walk to school, walk back. Everybody knew who you were. Everybody knew everybody.”

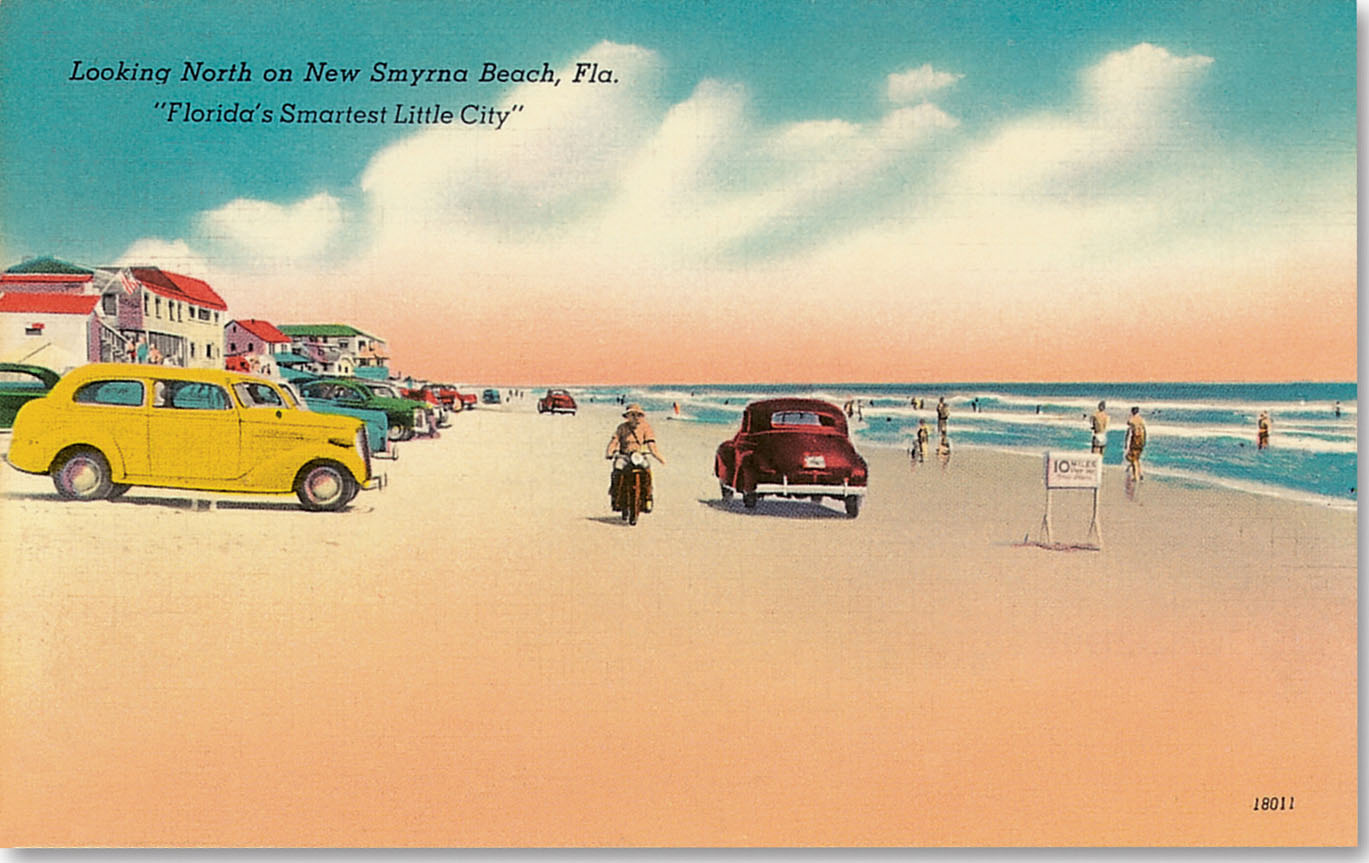

In 1951, Neil fell victim to an outbreak of polio. The dreaded disease, which often killed its victims or left them paralyzed or crippled, left him with no lasting effects beyond fatigue. The family spent half of 1952 in Florida to let Neiler heal in the warmth of the sun.

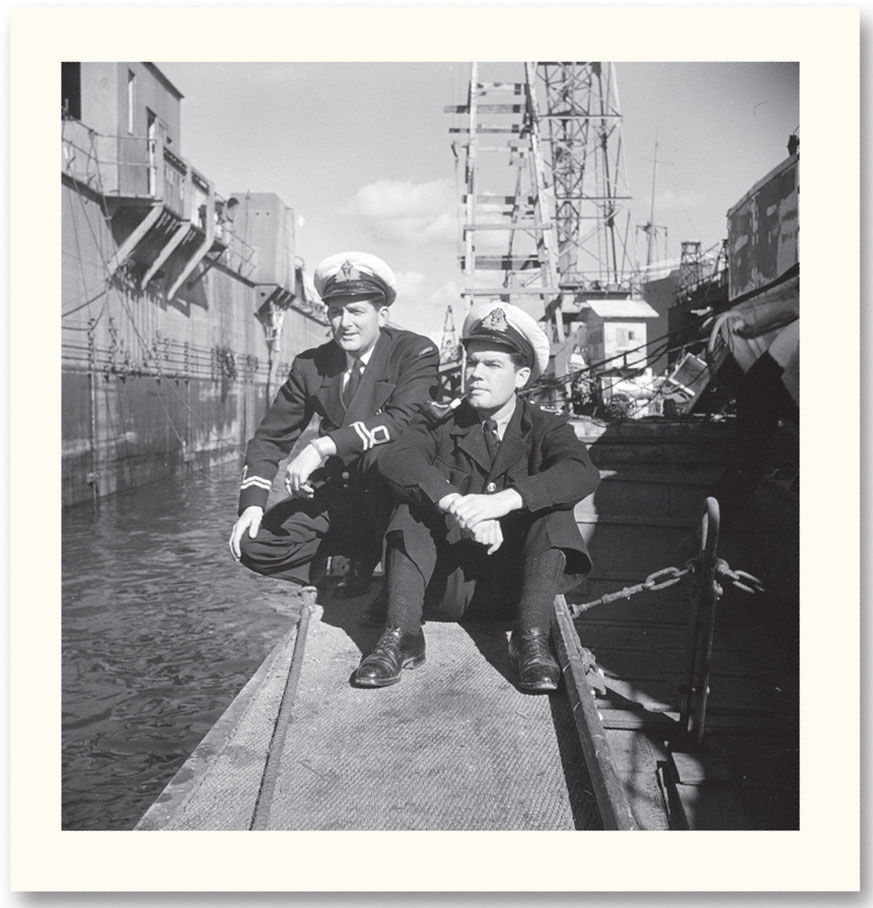

Lieutenant Scott Young (right) of HMCS Prince Henry, Taranto, Italy, October 1944. Library and Archives Canada/Department of National Defence fonds/PA-188925

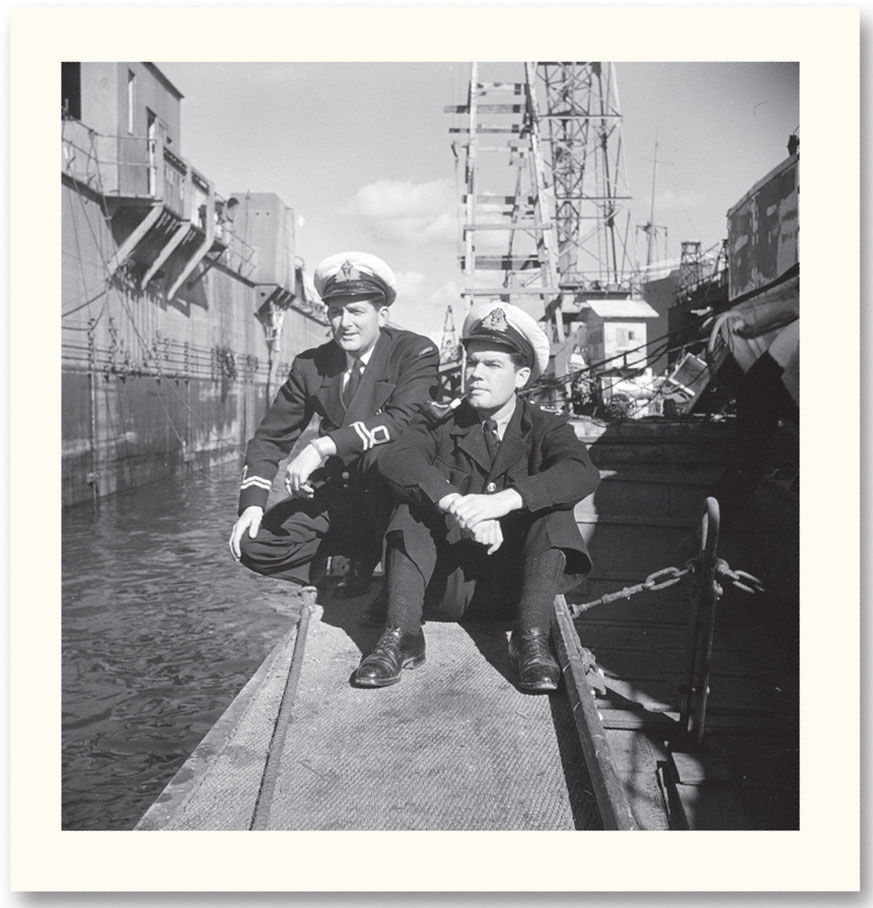

Neil Young, age two, Ontario, August 18, 1948.

© El Scan/ Toronto Star/Zuma Press

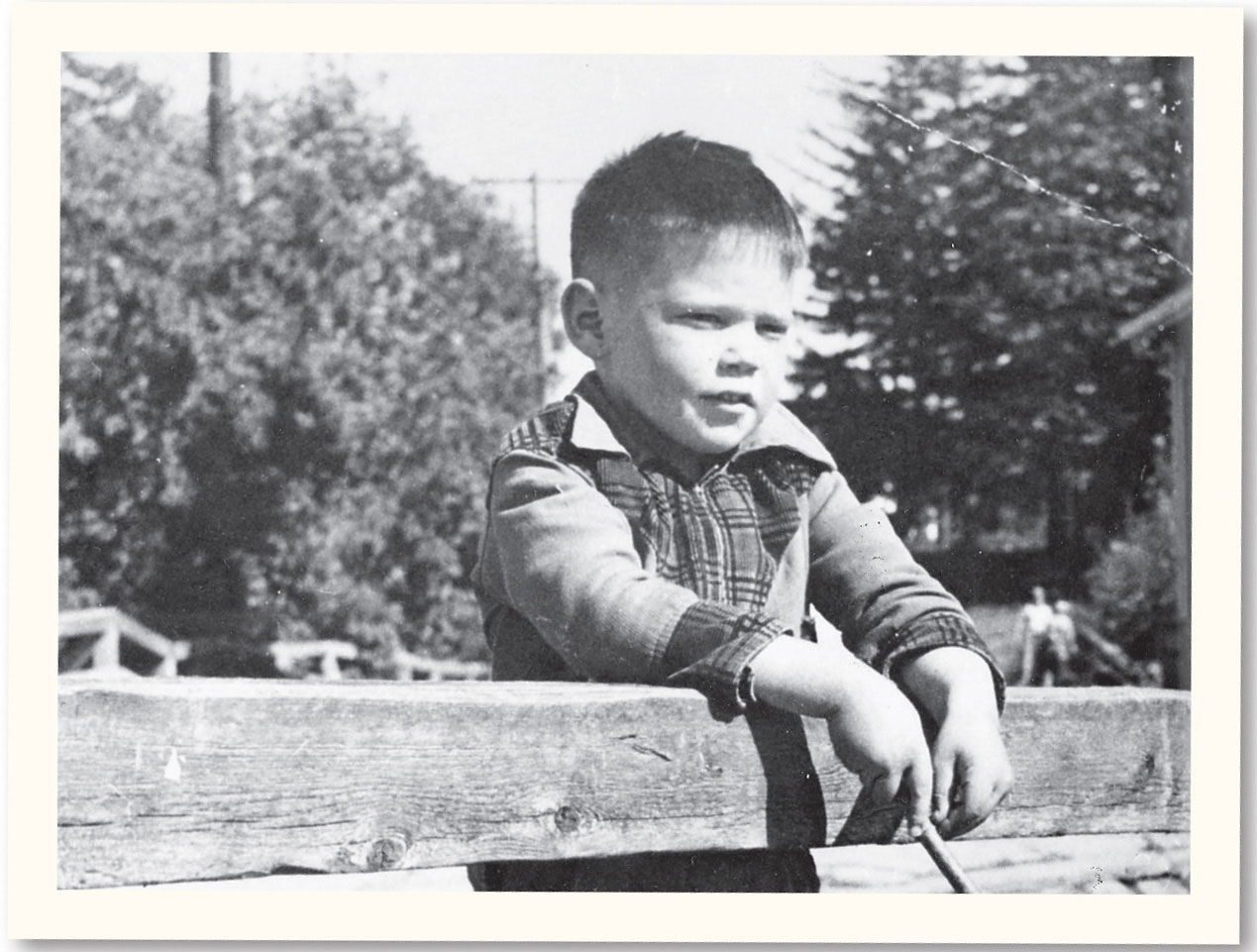

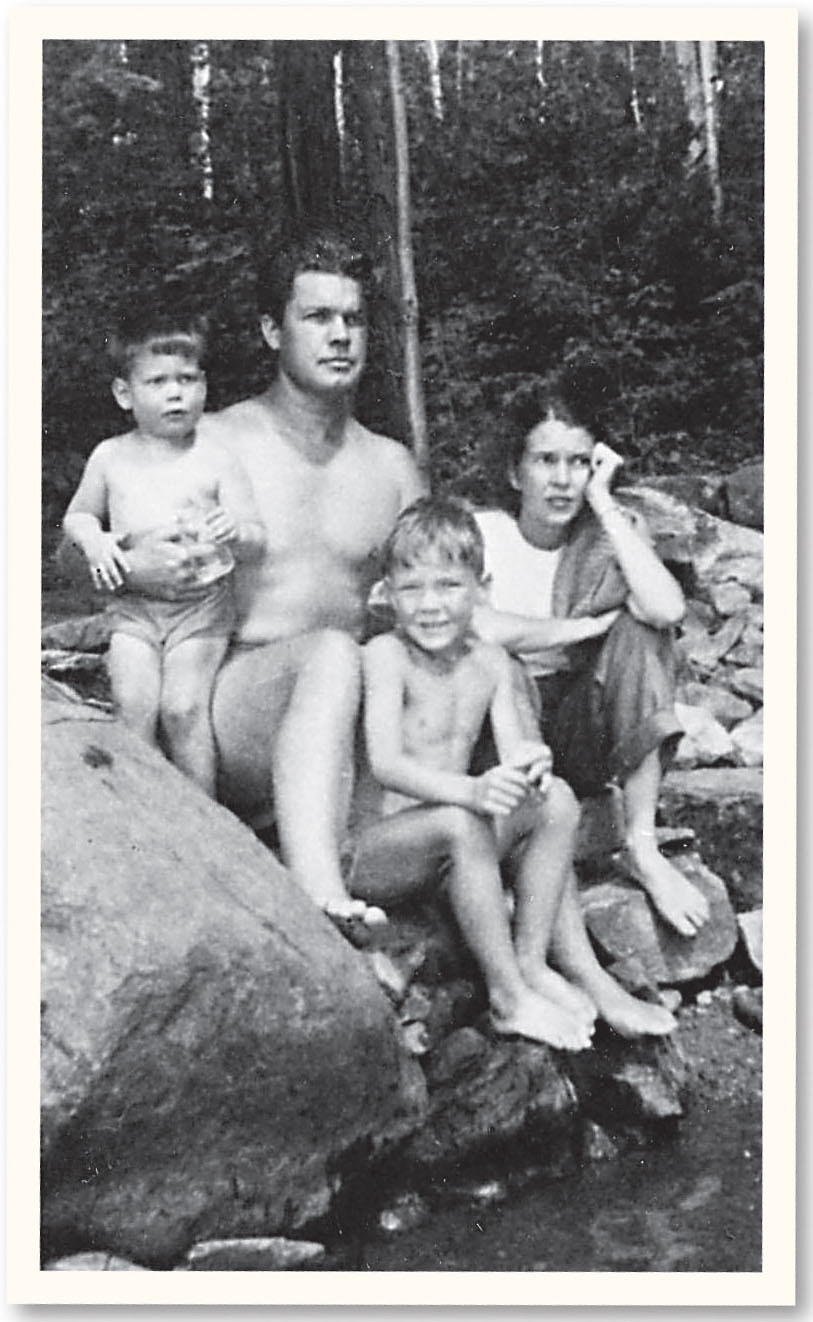

Two-year-old Neil Young with father Scott, mother Rassy, and older brother Bob in Ontario, August 18, 1948.

© El Scan/ Toronto Star/Zuma Press

The Toronto hospital where Young was born.

The Toronto hospital where Young was treated for polio in 1951.

To help Young recover from polio, the family retreated to New Smyrna Beach, Florida, in 1952.

The next few years were turbulent, as Scott and Rassy separated and reunited several times. They moved back to Toronto, where Scott wrote a sports column for the Globe and Mail and became the intermission host for Canadian TV’s most popular show, Hockey Night in Canada.

Eleven-year-old Neil thrived, though, earning money by raising chickens and selling eggs. In a school essay about his lucrative hobby, he wrote, “When I finish school, I plan to go to Ontario Agricultural College and perhaps learn to be a scientific farmer.”

At the same time, Neil fell in love with rock’n’ roll. His transistor radio, a constant companion under his covers at night, played local station CHUM but also pulled in far-flung stations from around the United States. Rockers Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Elvis Presley were among his favorites, along with the country sounds of Johnny Cash, Ferlin Husky, and Marty Robbins. There were no musical instruments around the house until late 1958, when Scott and Rassy bought Neil a plastic ukulele. “He would close the door of his room at the top of the stairs,” Scott recalled, “and we would hear plunk, pause while he moved his fingers to the next chord, plunk, pause while he moved again, plunk.”

The family fell apart once and for all when Scott went on a long assignment for the Globe and Mail and met publicist Astrid Mead. He split from Rassy, taking Bob with him. Scott and Mead would marry in 1961. Neil and his mother, meanwhile, returned to Winnipeg, a painful journey recounted in the first verse of Young’s “Don’t Be Denied.”

Young’s first year in Winnipeg. Young is in the third row from the bottom, third photo from the left. Future Squire bandmate Ken Koblun is in the second row from the bottom, fourth photo from the left. Courtesy John Einarson

“If you look at a map of North America, dead center is the town of Winnipeg, Canada,” Guess Who/Bachman Turner Overdrive guitarist (and Winnipeg native) Randy Bachman told PBS’s American Masters. “It’s dead center, so it’s the middle of everywhere or the middle of nowhere, depending on how you look at it. The nearest city of consequence is three or four hundred miles. So when you’re in Winnipeg, you’re in Winnipeg. . . . The winters are six or seven months long.”

Neil’s plastic ukulele was succeeded by a baritone uke, a banjo, and finally an acoustic guitar. He formed his first band, the Jades, which performed one gig at the local community center. At Kelvin High School, he was something of a loner, drawn into himself by his family’s disintegration. When he was picked on by some bullies, though, he became determined to stand his ground.

“The guy who sat in front of me turned around and hit my books off the desk with his elbow,” Young told Rolling Stone. “He did this a few times. . . . I went up to the teacher and asked if I could have the dictionary. This was the first time I’d broken the ice and put my hand up to ask for anything since I got to the fucking place. Everybody thought I didn’t speak. So I got the dictionary, this big Webster’s with little indentations for your thumb for every letter. I took it back to my desk, thumbed through it a little bit. Then I just sort of stood up in my seat, raised it up above my head as far as I could and hit the guy in front of me over the head with it. Knocked him out.”

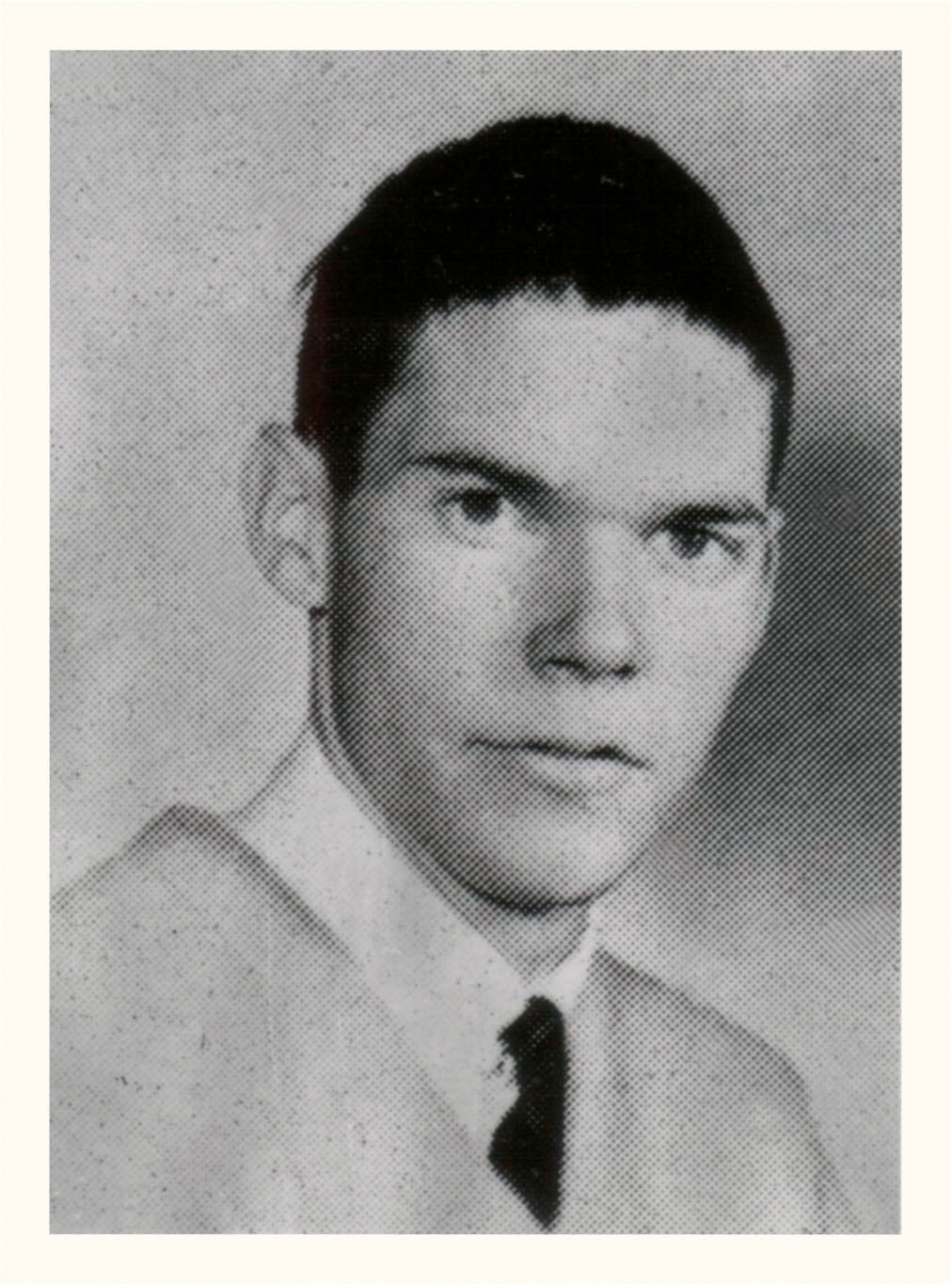

Young’s last yearbook photo, Kelvin Technical High School, Winnipeg, 1963. Courtesy John Einarson

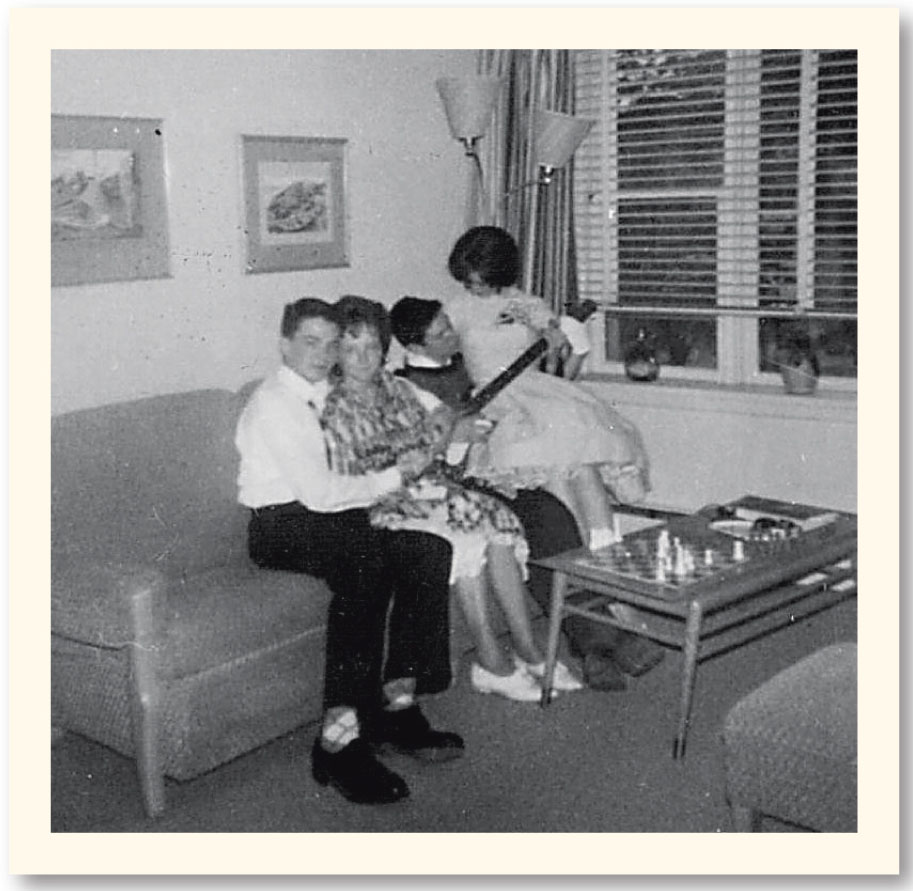

Young escorted Jacolyne Nentwig to the 1962 Humpty Dumpty Ball, River Heights, Winnipeg. Courtesy John Einarson

Young with his first electric guitar, Gray Apartments, Winnipeg junior high school graduation, 1961. Courtesy John Einarson

He was temporarily expelled for his actions, but the word was out on Neil Young. “That’s the way I fight,” he said. “If you’re going to fight, you may as well fight to wipe who or whatever it is out. Or don’t fight at all.”

Young took further refuge in music, making friends with a boy named Comrie Smith, who had more rock’n’ roll records than Young as well as a set of bongos. They formed a band, only to realize that they couldn’t really play. But there would be other bands. Young was captivated by groups on the local community center circuit—including Chad Allen and the Expressions, which included Randy Bachman and would one day morph into the Guess Who—and obsessed by British outfits such as the Shadows, which featured the echo-laden guitar stylings of Hank B. Marvin. Young practiced feverishly, mostly to the detriment of his studies.

He signed on with a band called the Esquires but was forced to quit by his mother, by then something of a local celebrity as a panelist on the TV quiz show Twenty Questions. But Young persisted, forming the Stardusters and then the Classics with another friend, bassist Ken Koblun. With drummer Jack Harper (soon to be replaced by Ken Smythe) and guitarist Allen Bates, Young and Koblun would form the Squires, not to be confused with the similarly named (and at the time, still extant) Esquires.

The Squires’ repertoire consisted of old pop tunes and instrumental rock’n’ roll songs that spotlighted Young’s guitar. “I always like the primitive in rock’n’ roll,” he told American Masters. “Link Wray: He’s a great player. He was the beginning of grunge way before anybody, you know. . . . There was quite an influence from the Shadows and the Ventures and the Fireballs from Texas. There were these surf bands that played instrumentals that were really good. We were mostly an instrumental band at first, so we paid a lot of attention to them.”

“I think our main influence was definitely the Shadows,” Allen Bates recalled. “I think our bass player, Kenny Koblun, lived with an English family in Winnipeg, across from Churchill High School. He received these beautiful British rock’n’ roll records before the rest of Canada did, so we were able to copy them or imitate them and go play at a community club and people would’ve thought they were ours. Later on, Neil started writing tunes, instrumental tunes that were surely as good as the Shadows. We were only sixteen and we were damn good.”

Rassy Ragland Young (bottom) on the quiz show Twenty Questions. Courtesy John Einarson

“The Sultan” backed with “Aurora,” 1963. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

Winnipeg 1964. Courtesy John Einarson

Churchill, Manitoba, where the Squires played in 1964.

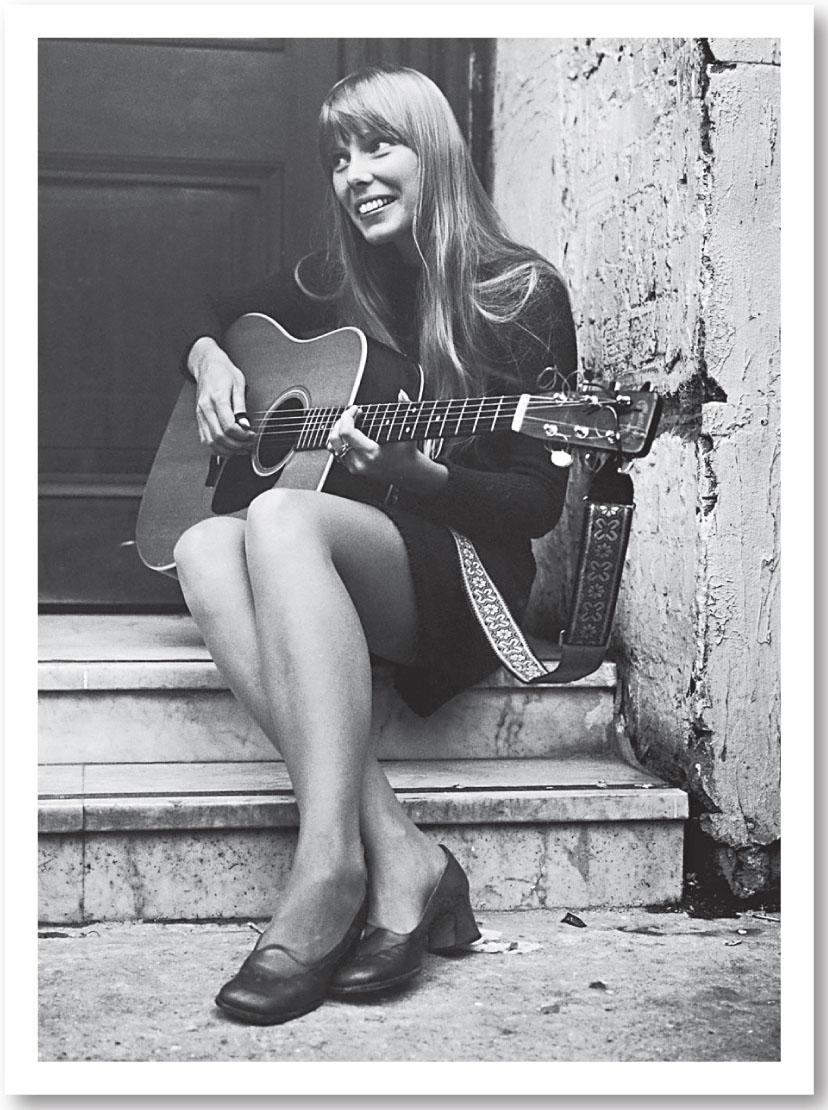

Joni Mitchell. Photo by Central Press/Getty Images

They were good enough, in fact, to catch the attention of CKRC deejay Bob Bradburn, who oversaw the Squires’ first recording session. On July 23, 1963, the band recorded two instrumentals, “The Sultan” and “Aurora.” Some weeks later, the single appeared on local label V Records.

Caught up by the spirit of Beatlemania, Young attempted to add vocals to the Squires’ sonic attack. During a gig, he warbled his way through covers of “It Won’t Be Long” and “Money.” “After exposing myself in that way, I think I heard the odd cry of ‘Boy, don’t do that again,’” Young told McDonough. “I don’t really remember the reaction, though—I remember more how I felt. I felt great, ’cause I’d sung.” When the Squires recorded again at CKRC, Young was ready to put his voice on tape as well, singing “I Wonder” and “Ain’t It the Truth,” though nothing ever came of the tracks.

But even as Young continued to put his rock ’n’ roll ambitions into motion, folk music started taking hold of him, too. He hung out at Winnipeg’s Fourth Dimension coffee house; discovered records by Bob Dylan, the Kingston Trio, and Ian and Sylvia; and dreamed of ways to combine the elements of folk and rock in his own music.

He also befriended nascent folkie Joan Anderson, who would later gain fame as Joni Mitchell. She was in Winnipeg performing at the Fourth Dimension. “I’ve known Joni since I was 18,” Young told Rolling Stone. “I met her in one of the coffeehouses. She was beautiful. That was my first impression. She was real frail and wispy looking. . . . I remember thinking that if you blew hard enough, you could probably knock her over. She could hold up a Martin D18 pretty well, though.”

Kelvin Technical High School fundraiser, 1964. Courtesy John Einarson

He bought a car that could accommodate the band’s equipment; it was a 1948 Buick Roadmaster hearse, nicknamed Mortimer Hearseburg. “It had rollers for the coffin in the back, so we just rolled our amps in and out,” Young said. “It was like they built it for us.”

The Squires pose with Mort before departing Winnipeg, Manitoba, for Fort William, Ontario, April 1965. From left: Ken Koblun, Neil Young, and Bob Clark. Courtesy Owen Clark

Vacationing at Falcon Lake, seventy-five miles from Winnipeg, Young managed to score the Squires a booking. But when two of his bandmates couldn’t make it, Young fired them, later reforming the group with Koblun, drummer Bill Edmonson, and pianist Jeff Wuckert.

“We just kept morphing and changing,” Young told American Masters. “People would join and we’d go do gigs out of town and they’d quit because they didn’t want to leave town. Eventually I got two other guys that wanted to leave town and were ready to take a chance. . . . Some of the guys that I wanted to take I couldn’t take because their parents would say, ‘You’re gonna screw up your life,’ and suddenly the thing would derail. Just good musicians who wouldn’t step out and take a chance got left behind.”

Young’s music blossomed, but his studies suffered, and he dropped out of high school. With financial help from his mother, he bought a car that could accommodate the band’s equipment; it was a 1948 Buick Roadmaster hearse, nicknamed Mortimer Hearseburg. “It had rollers for the coffin in the back, so we just rolled our amps in and out,” Young said. “It was like they built it for us.”

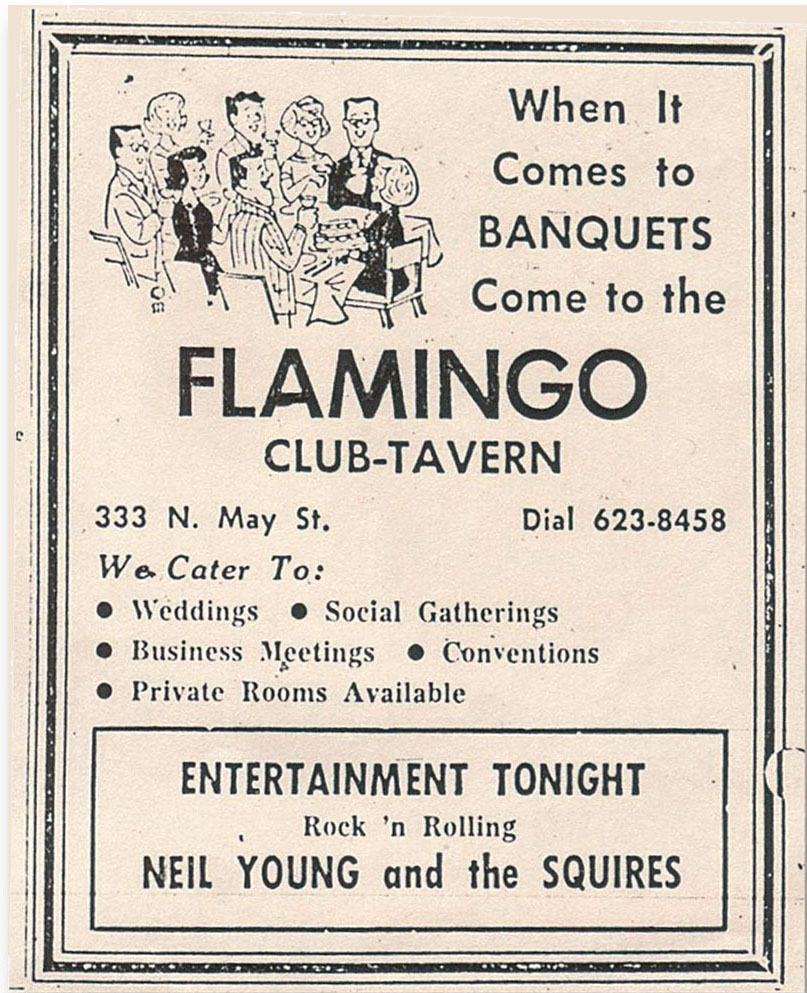

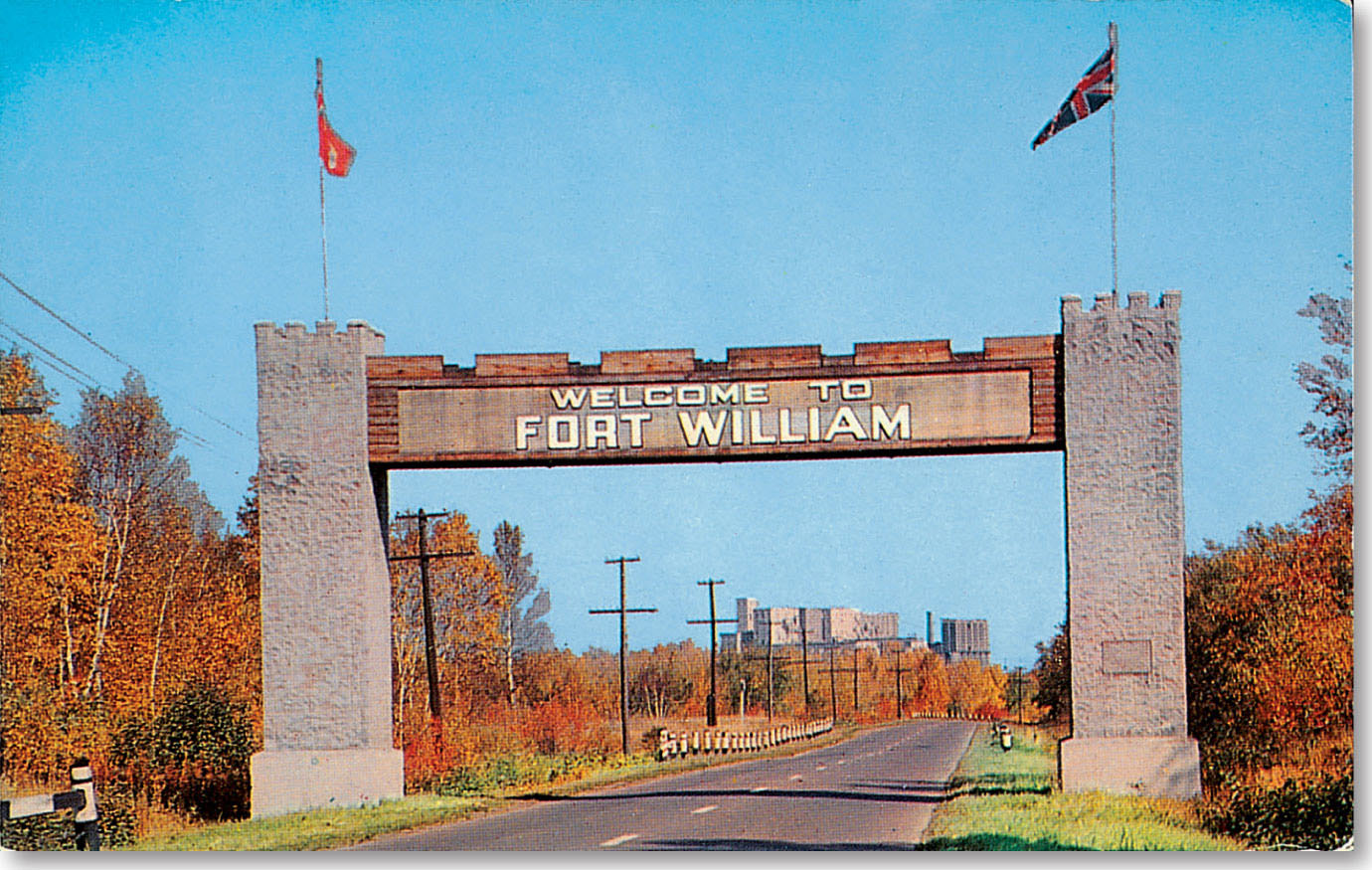

The Squires headed east. They landed in Fort William, Ontario, a working-class town that would later join with nearby Port Arthur to form Thunder Bay. There they found work at local clubs and hooked up with deejay Ray Dee (né Delatinsky), who would help guide the next part of the band’s career, booking gigs and manning the board for the recording of “I’ll Love You Forever.” The song is notable both for its use of double-tracking to make Young’s singing voice palatable and for its use of overdubbed surf sounds to cover instrumental flubs.

It was in Fort William’s Victoria Hotel on or near his nineteenth birthday that Young wrote his coming-of-age classic “Sugar Mountain.” But the most important association Young would make in the city was with Stephen Stills, a Texas-born guitarist who had migrated to New York’s Greenwich Village and sang in a vocal ensemble called the Au Go Go Singers. A splinter version of the group, the Company Singers, was performing in Fort William. “He was doing exactly what I wanted to do, which was play folk songs on an electric guitar and songs that he’d written himself,” Stills told American Masters. “Mainly, he was the funniest person I’d met in years. He didn’t have another gig until the next weekend, so he stayed in Thunder Bay and we played and he took us to see buffalo. We lived on A&W cheeseburgers and root beer. Very Canadian.”

Aware of the fact that Fort William was a dead end, Young wanted to go to England to pursue his musical dreams—or, failing that, Los Angeles. He saw Toronto as a steppingstone, and the band packed into Mort. But the car died in Blind River, Ontario, its transmission splayed out all over the road. (Young would later memorialize the event in his song “Long May You Run.”) For all practical purposes, the band was dead, too, as Young left his bandmates to fend for themselves while he hitchhiked the rest of the way to Toronto. He stayed at his father’s house until getting his own place in the city’s bohemian quarter, Yorkville.

Fort William, Ontario, April 1965. Courtesy Owen Clark

The Squires, Fourth Dimension coffee house, Fort William, Ontario, May 1965. Courtesy John Einarson

I admire him a lot. It sort of freaks me out that he wrote “Sugar Mountain” when he was, what, 17 years old? That’s not fair. And he didn’t quit then; he challenged himself and challenged his audience to the point of risking losing them. I admire that a lot.

—Rhett Miller, Old 97’s

Blind River, Ontario, where Mort—and the Squires—expired.

Stephen Stills and Neil Young, 1967. The bandmates first met in Fort William, Ontario, in 1963. © Henry Diltz/Corbis

Toronto subway.

In Toronto, Young reconnected with Comrie Smith, his friend from Winnipeg, and dove into the local folk scene. With no gigs to be had, though, he got a job in a bookstore stockroom, though it lasted only two weeks. “I got fired for irregularity,” he told an audience at the Canterbury House in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in November 1968, “because I couldn’t be depended on to be consistent ’cause every once in a while this girl I knew . . . would lay one of these little red pills on me. . . . She said they were diet pills, but they were really great diet pills.” He continued writing, coming up with “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing,” and he and Smith recorded a handful of tunes, including the Jimmy Reed–style blues “Hello Lonely Woman,” in Smith’s attic.

The Squires—under a new moniker, Four to Go—reunited for one last gig, at a ski resort in Vermont. Once in the States, Young and Ken Koblun decided to head for New York City, where they hoped to find Stephen Stills, who, it turned out, had already left for California. Instead, they met Stills’ friend Richie Furay, to whom Young taught his song “Clancy.”

Several months later, Young was back in New York, having scored an audition with Elektra Records. Rather than a proper studio setup, Young was given a tape recorder and sent to lay down the tracks in a tape vault. The demos went nowhere. Back in Toronto, a new opportunity popped up when Bruce Palmer, an established figure on the city scene and a fellow Canadian, bumped into Young, who was walking down the street carrying a guitar and an amplifier. Palmer’s band, the Mynah Birds, happened to be without a guitarist and invited Young to join.

The Mynah Birds were fronted by an American, Ricky James Matthews, who would one day gain fame as ’80s funkster Rick James. The band was backed financially by John Craig Eaton, scion of the Eaton’s Department Store family. Incredibly, the Mynah Birds landed a recording deal with Motown Records. Palmer told Scott Young that the Mynah Birds “were the first white group Motown ever signed.” Reminded that Rick James was, in fact, black, Palmer quipped, “He’s getting blacker all the time but as far as we knew he was white then.”

Young recorded a handful of songs with the Mynah Birds, but the prospective album—and indeed, all of their plans—came crashing down when it was discovered that Matthews was AWOL from the U.S. Navy. He landed in prison.

“Probably 90 per cent of the acts there were better groups than the Mynah Birds,” Palmer told Scott Young. “But we were weird, we were really different. We were the only group with a twelve-string guitar on Motown. Playing a country twelve-string with this rock beat. And actually, they kind of liked the sound of it.”

Still in possession of the Mynah Birds equipment (which technically belonged to investor John Craig Eaton), Young sold it for money to make a break for California, where he hoped to locate Stills. He bought a 1953 Pontiac hearse that he named Mort Two, loaded up Palmer and some other friends, and took off for Los Angeles, using a circuitous route that would arouse the least suspicion about a bunch of kids with no work permits or money.

Along the way, Young resisted letting anyone else behind the wheel of Mort Two, the better to nurse the hulking but temperamental beast across the country. Fatigued and annoyed at the ragtag bunch, Young ordered everyone out of the car in Ohio, threatening to leave them on the side of the road. He relented and let them back in, driving on to Albuquerque, where he went into convulsions and passed out on the floor for several days.

Young recovered, and the car and some—but not all—of its inhabitants made it to L.A., the others being left behind in Albuquerque. But the picture was far from rosy at that point. Young and Palmer were broke and knew no one. Stills was nowhere in sight. For a few days, they made ends meet selling rides in the hearse. They were about to give up and head north to San Francisco when fate intervened in an L.A. traffic jam.

Buffalo Springfield, Ondine’s, New York, December 31, 1966–January 9, 1967. © Nurit Wilde (WildeImages.com)