Unshackled from Buffalo Springfield, Young sought to distance himself from the hectic Hollywood music scene he’d helped expand. He signed a solo deal with Warner/Reprise Records and used the advance money to buy a house in Topanga Canyon, a bucolic artist enclave and hippie hangout just outside Los Angeles. He also met and married Susan Acevedo, an earthy, no-nonsense woman eight years his senior who ran a local diner called the Canyon Kitchen.

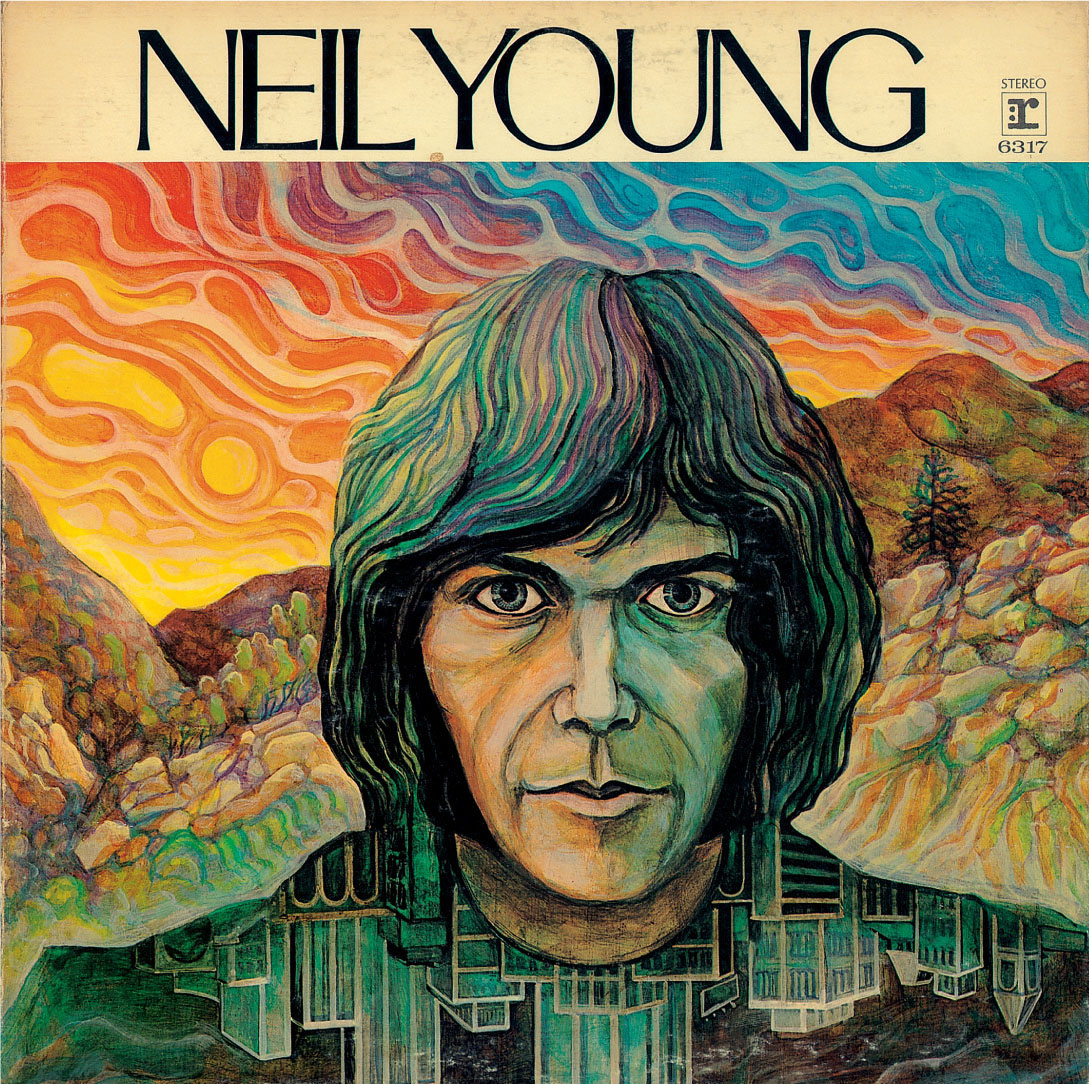

As much as it was his intention to “get out to the sticks and just relax,” as he told Rolling Stone, Young quickly began work on his first solo album. Jack Nitzsche, whose production and arranging skills served Young so well near the end of the Springfield era, helped him painstakingly create the lush, layered soundscapes of “The Old Laughing Lady” and “I’ve Loved Her So Long.”

Another long-term collaborator soon entered the mix: producer David Briggs, who first met Young in 1968 when he saw the scraggly guitarist hitchhiking on the side of the road and offered him a ride. A wildman denizen of Topanga and staff producer for Bill Cosby’s Tetragrammatron label, Briggs had his own ideas about how to produce rock ’n’ roll records. But the loose, spontaneous style he would develop with Young as years progressed is not in evidence on Neil Young. Instead, the basic tracks—featuring Springfield bassist Jim Messina and George Grantham, the drummer from Messina’s new band, Poco—were recorded in standard fashion in several L.A. studios, with strings, keyboards, and Young’s vocals added later.

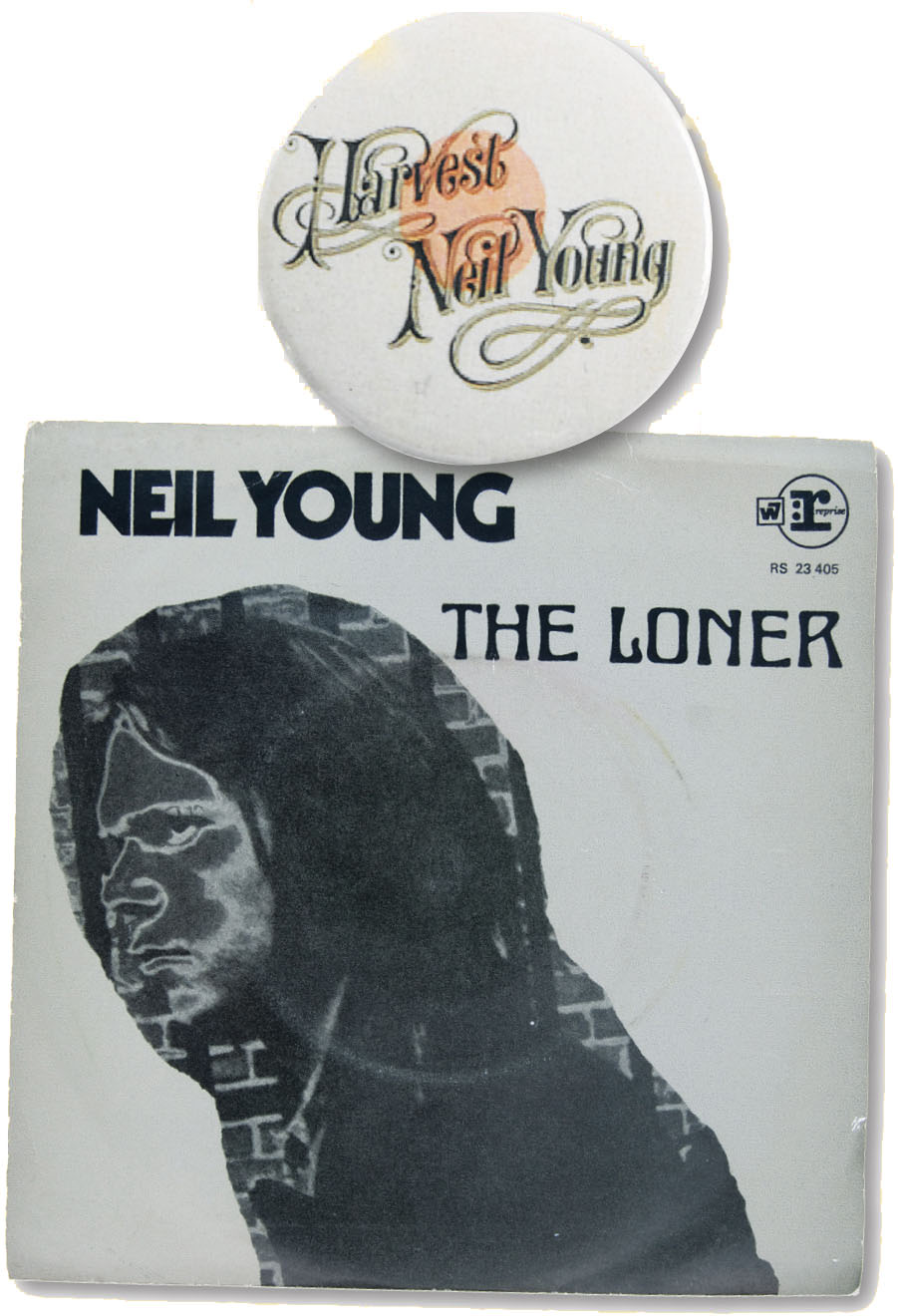

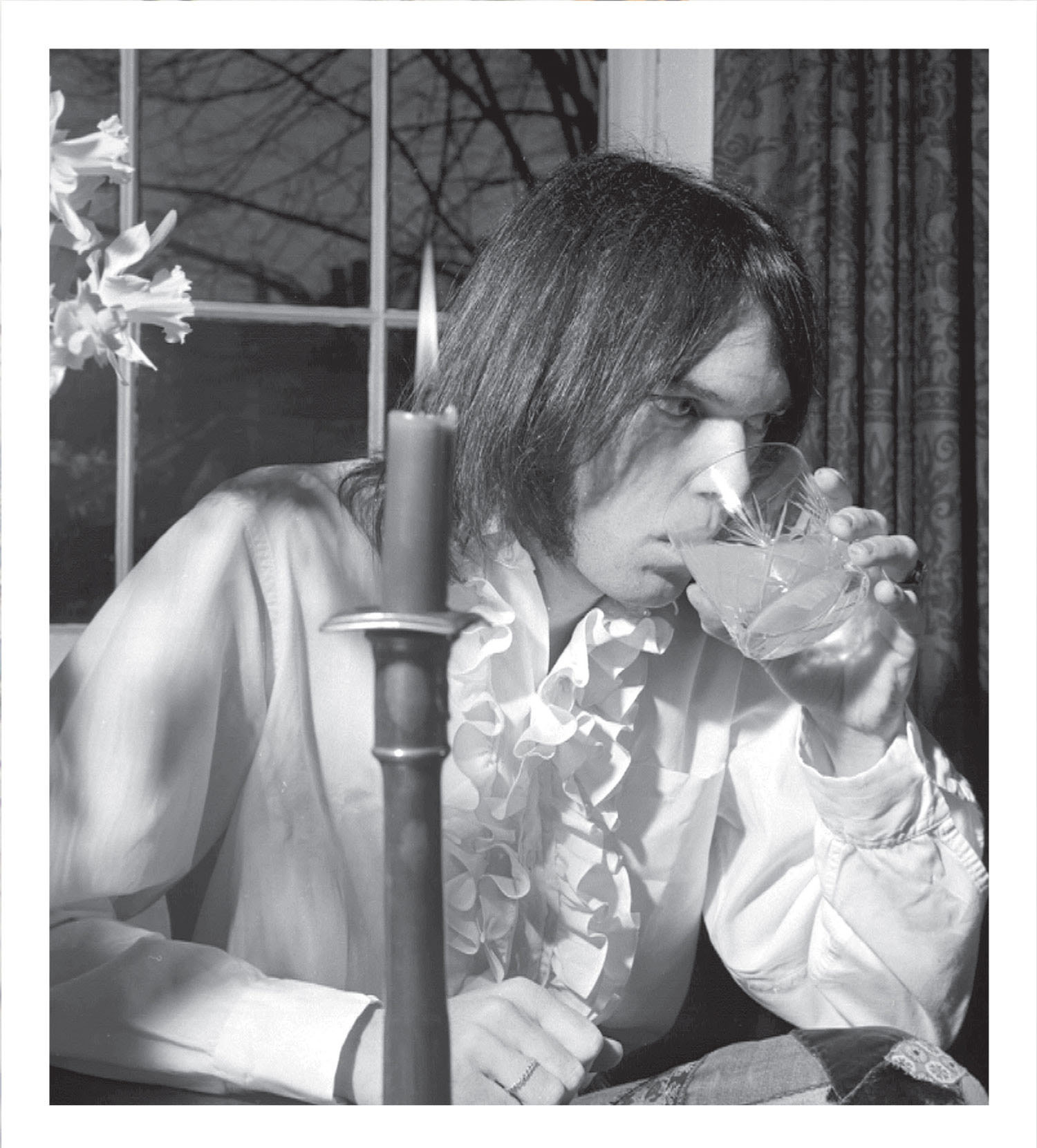

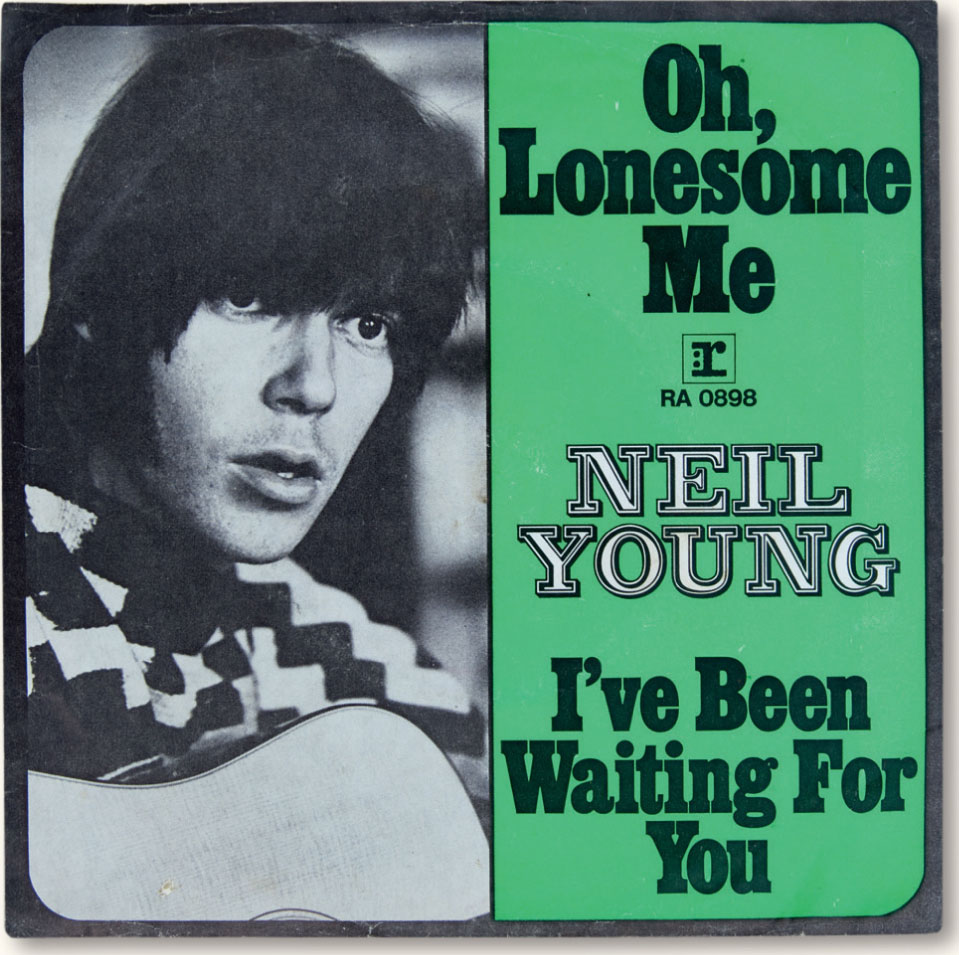

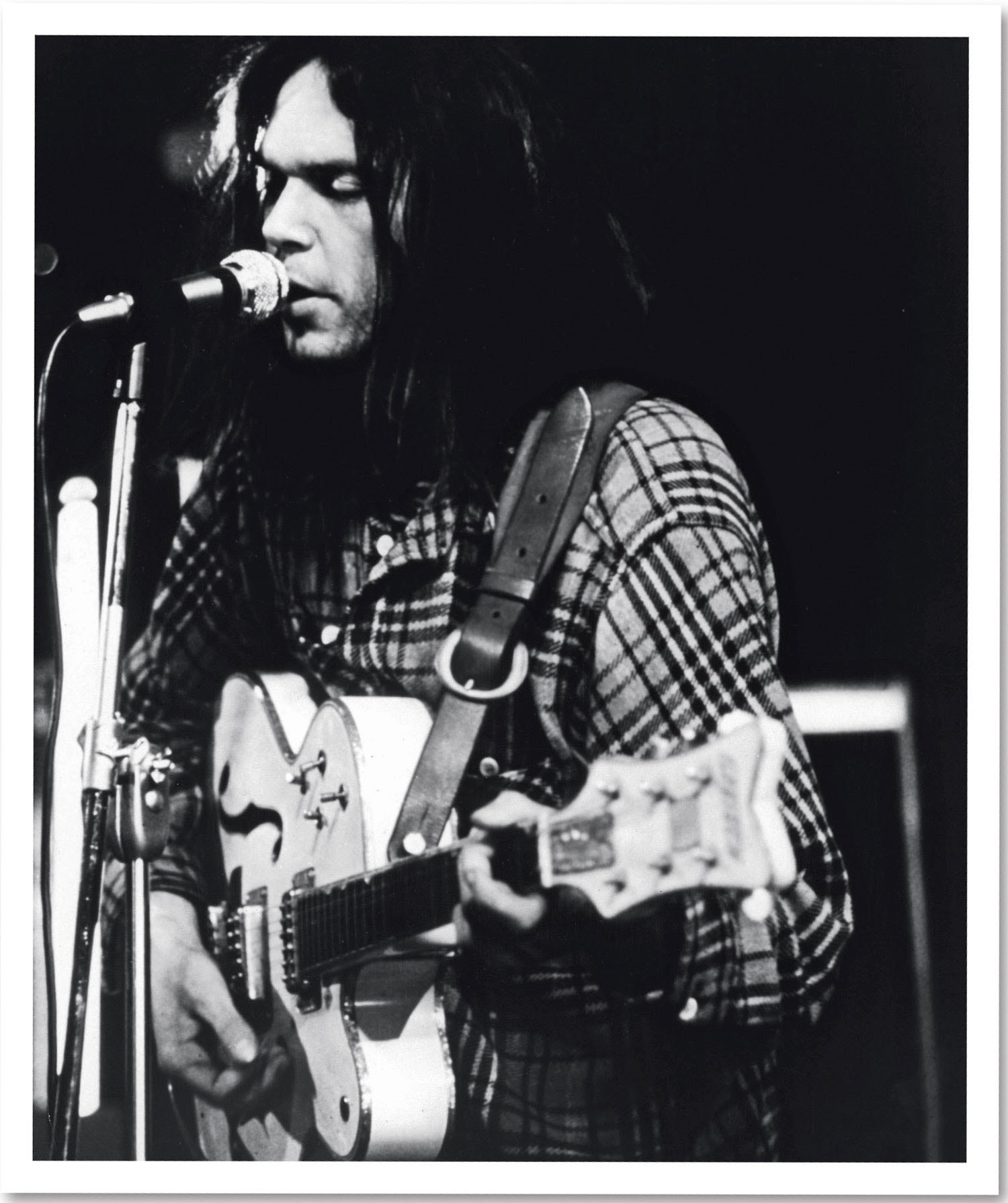

U.K., 1968. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

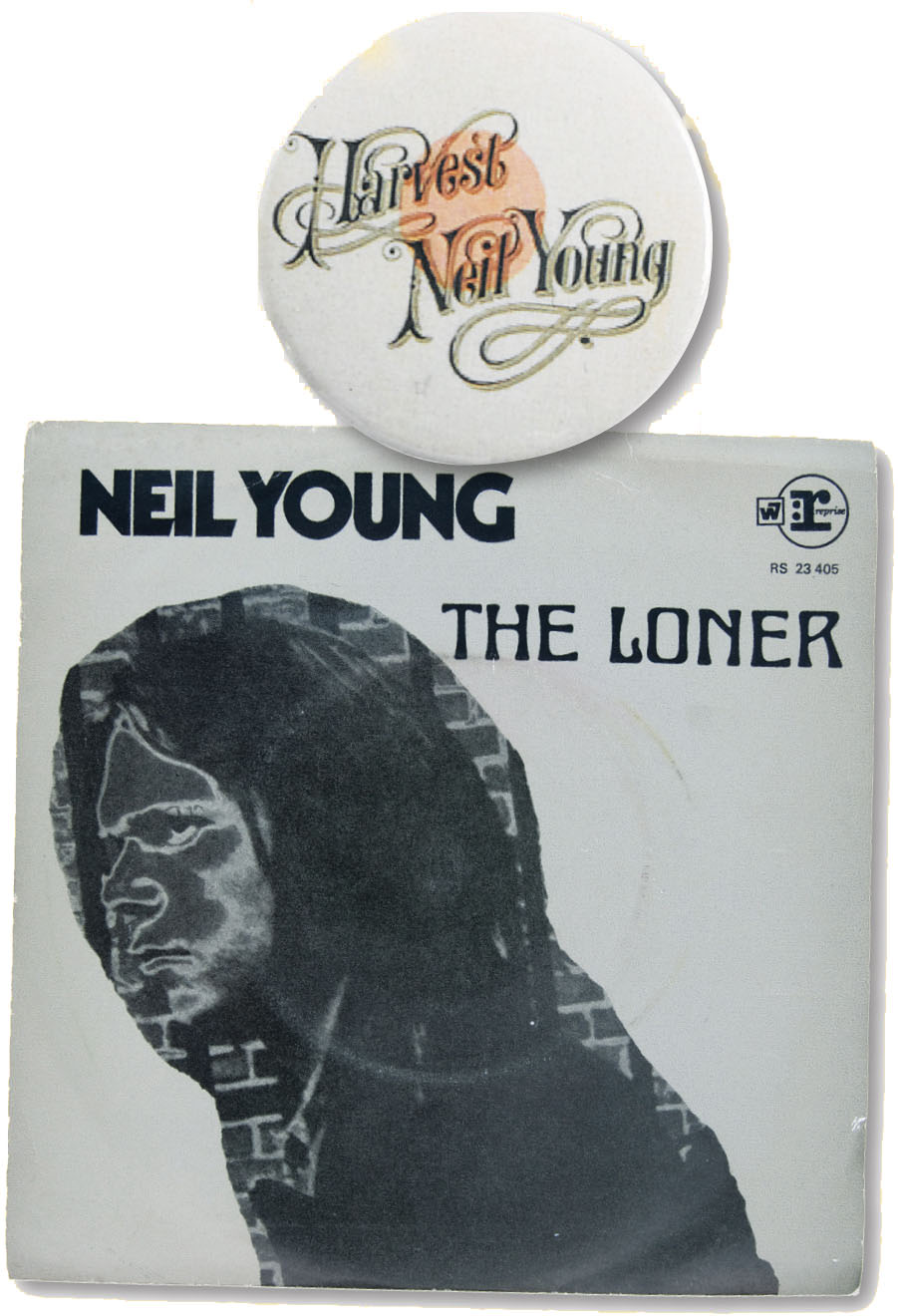

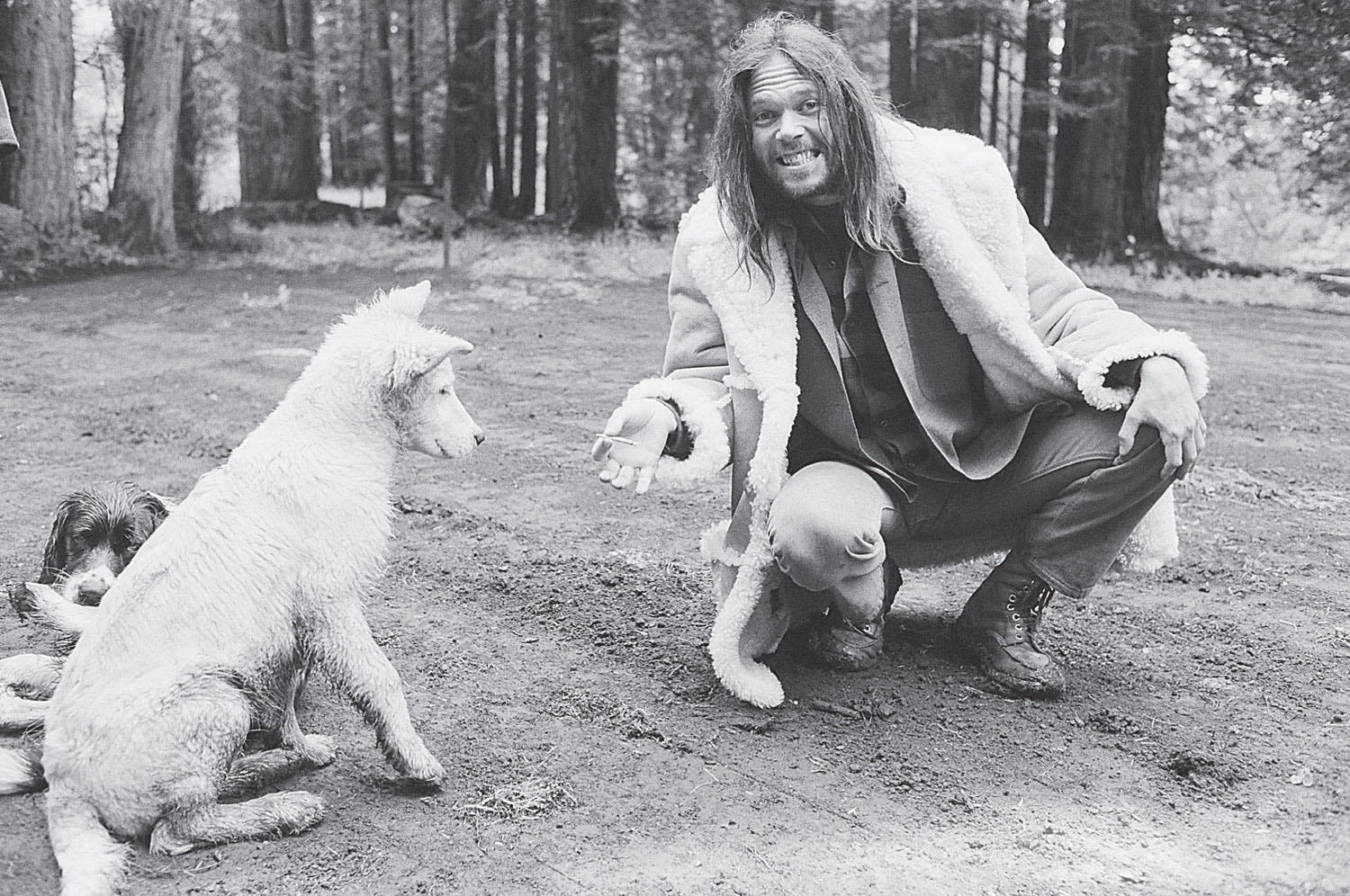

California, 1969.

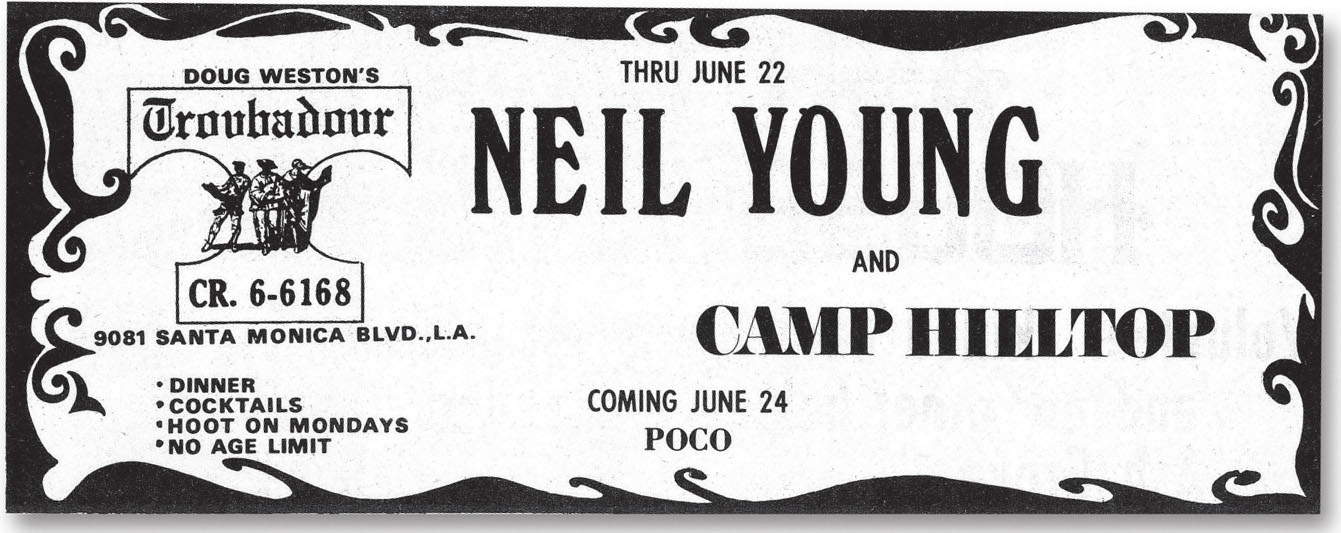

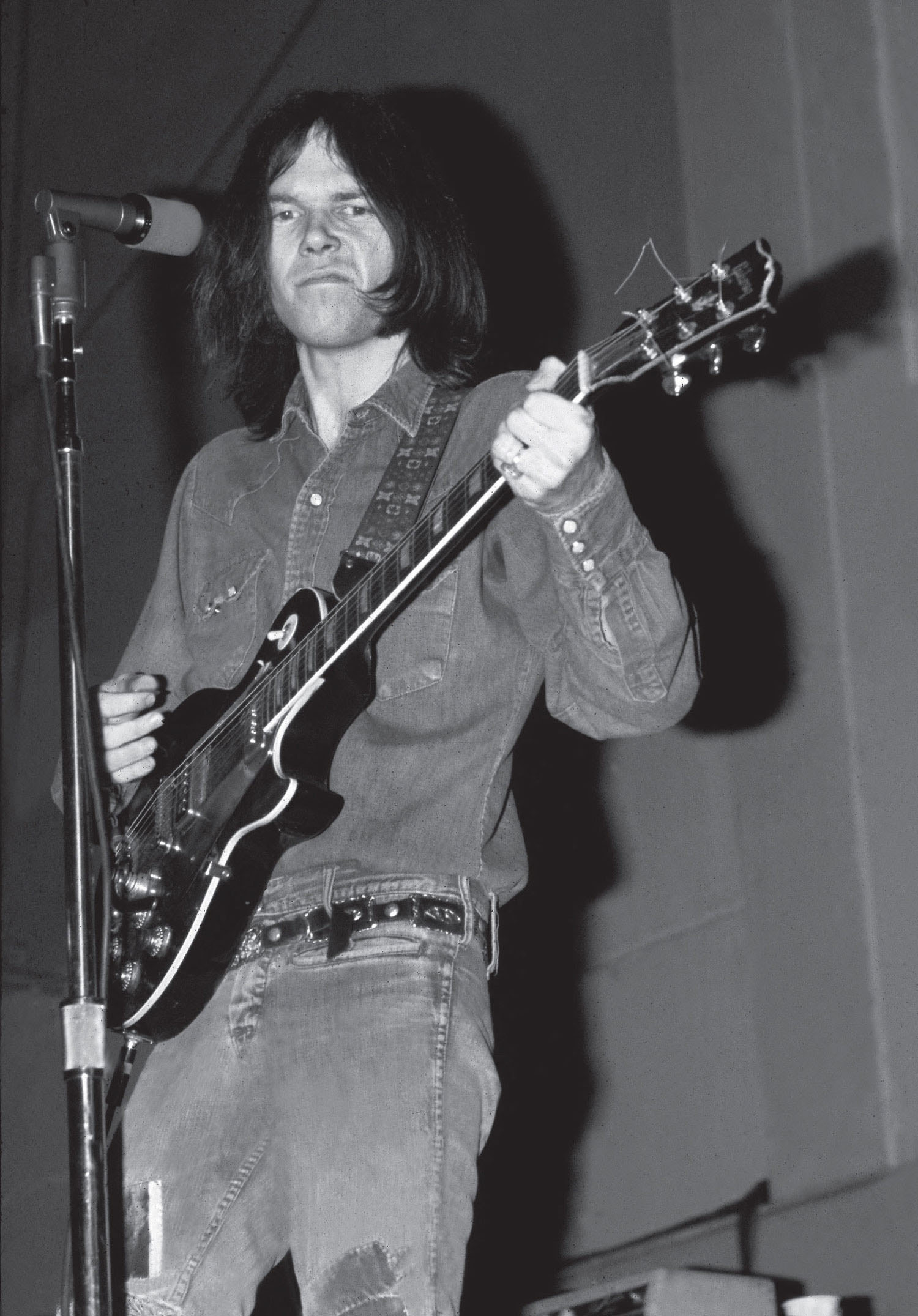

Toronto, Ontario, 1969. Courtesy John Einarson

Young would come to characterize his solo debut as “overdub city.”

Each side of the LP begins tentatively, with an instrumental track: side one with “The Emperor of Wyoming,” a polite, Western-inflected number, and side two with Nitzsche’s moody composition “String Quartet from Whiskey Boot Hill.” Some classic numbers emerge along the way, however, including “The Loner”—a bit of self-mythologizing on Young’s part, perhaps, as it concerns a menacing (but emotionally vulnerable) figure who is “the unforeseen danger, the keeper of the keys to the locks.” “The Old Laughing Lady” is given both grandeur and grit by Nitzsche’s use of strings complemented by the middle section’s haunting tribal chant, courtesy of a chorus of female singers that included Merry Clayton and Nitzsche’s wife, Gracia. Perhaps Briggs’ most substantial contribution to the proceedings is Young’s electric guitar tone on “The Loner” and “I’ve Been Waiting for You.” It’s fat, frenzied, and fuzzed out—a hint of the souped-up sonics to come.

When the album was released, it made minimal impact, hampered in part by a cover that didn’t include Young’s name. There was only a painting—and a slightly creepy one at that—of Young’s visage, with hills and a fiery sunset in the background, plus upside-down skyscrapers surreally reflected in his clothes. It was painted by Topanga artist Ronald Diehl, a friend of Acevedo’s.

More significantly, the sound of the music was off, too, since it had been run through an experimental mastering process without Young’s consent. A second pressing of the disc eliminated the sonic flaws and included Young’s name on the cover. Still, Young himself took responsibility for the album’s overly cautious approach. “If I had left it alone at an earlier stage, it would have been better,” he told Jimmy McDonough. “Like a lot of that Buffalo Springfield stuff—I went on working and fucked it up. I don’t do that anymore. Thank God I got that out of my system at an early age.”

Soon enough, Young would find the band he needed to create music that was ragged, yes, but undeniably right. In fact, he’d found it already.

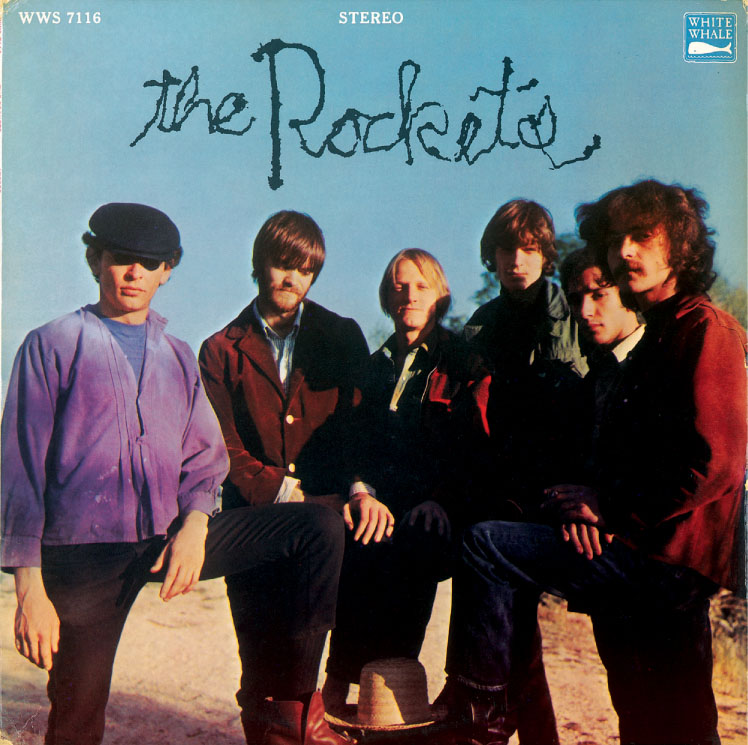

Sometime in the hazy days of the Springfield’s rise to fame, Young met the Rockets and jammed at the group’s Laurel Canyon “headquarters.”

Danny Whitten, Billy Talbot, and Ralph Molina had relocated to California from the East and formed the vocal group Danny and the Memories. They recorded a single that went nowhere before moving to San Francisco and picking up instruments—guitar, bass, and drums, respectively. They recorded another single, this time as the psychedelic Psyrcle, but failed to break through once again. Back in L.A., they joined with violinist Bobby Notkoff and guitarist Leon Whitsell—later adding his brother George, another guitarist—and formed the Rockets.

Young heard the band’s 1968 self-titled debut album and agreed to sit in when the Rockets played the Whisky. For the occasion, he broke out his new guitar—a sonically unwieldy 1953 Gibson Les Paul that had previously belonged to Jim Messina. It had been daubed with black paint and christened Old Black. Matched with a vintage Fender Deluxe amplifier, the guitar would inspire Young to create some of the most exciting electric music of his career. And so would the Rockets. “They were real primitive, but they had a lot of soul,” he told PBS’s American Masters.

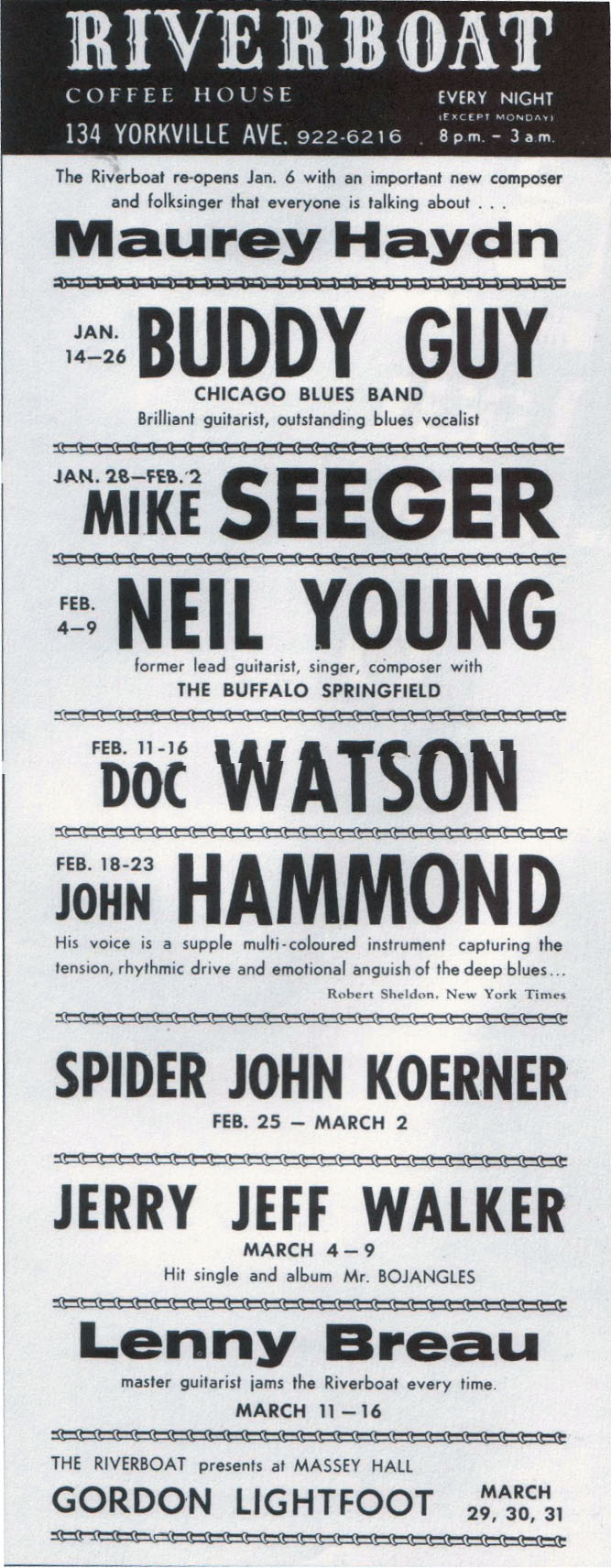

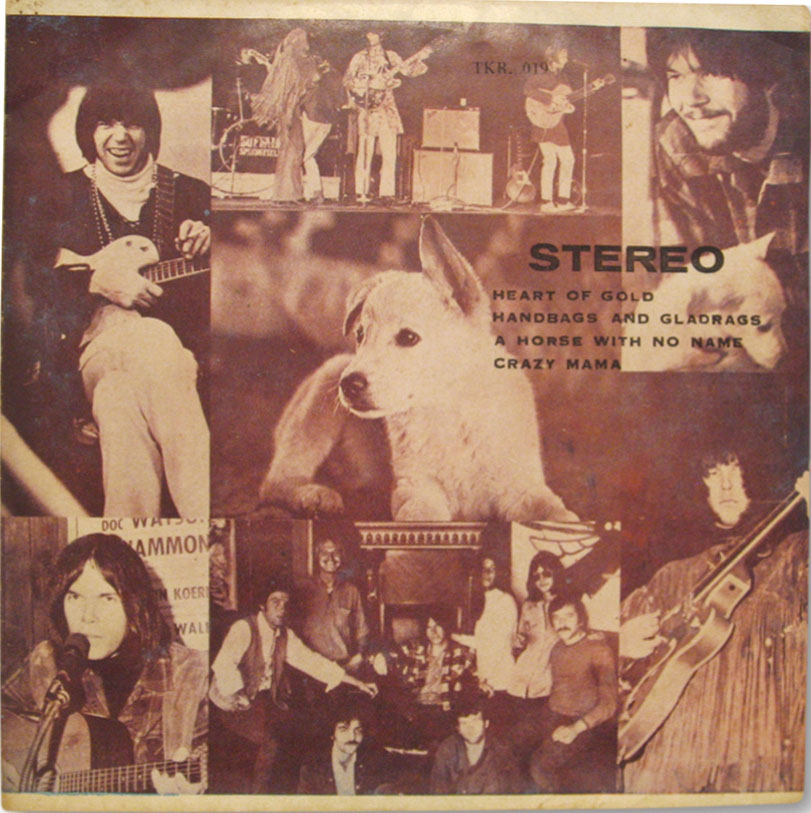

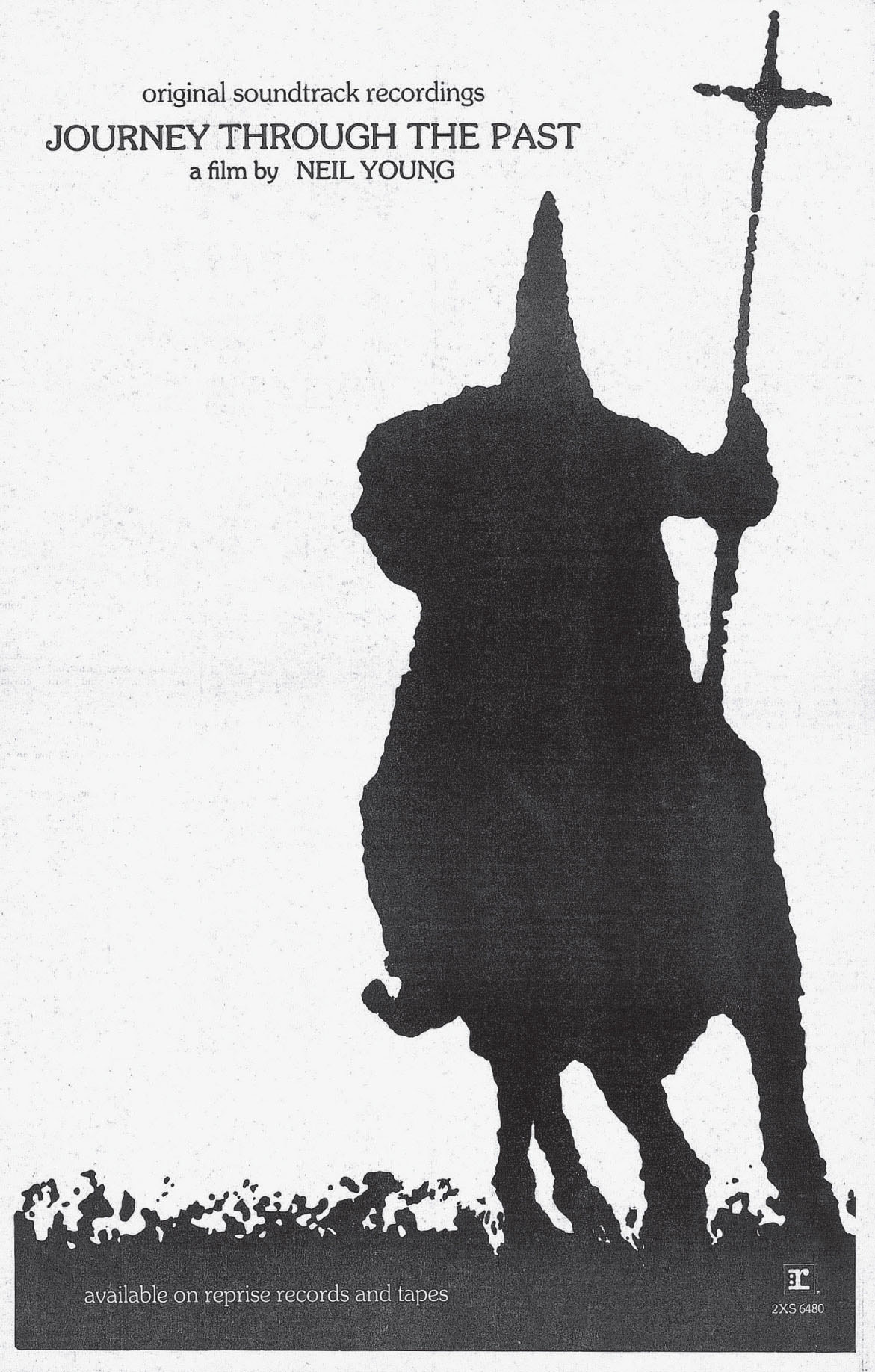

Neil Young and Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere compilation double LP.

After inviting Whitten, Talbot, and Molina to jam at his house in Topanga, Young sensed the moment was there to be captured and booked studio time immediately. As a consequence, the Rockets were history. The new band was called Crazy Horse.

“I think I went in there and I asked those three guys to play with me as Crazy Horse,” Young recalled in the film Year of the Horse. “And I thought the Rockets could go on, too. But the truth is, I probably did steal them away from the other band, which was a good band. But only because what we did, we went somewhere. What they were doing, it didn’t go anywhere at that time, so this thing moved, this thing took off, and the other thing didn’t. But the other thing could have gone on, I guess. That’s the hardest part, is the guilt of the trail of destruction that I’ve left behind me.”

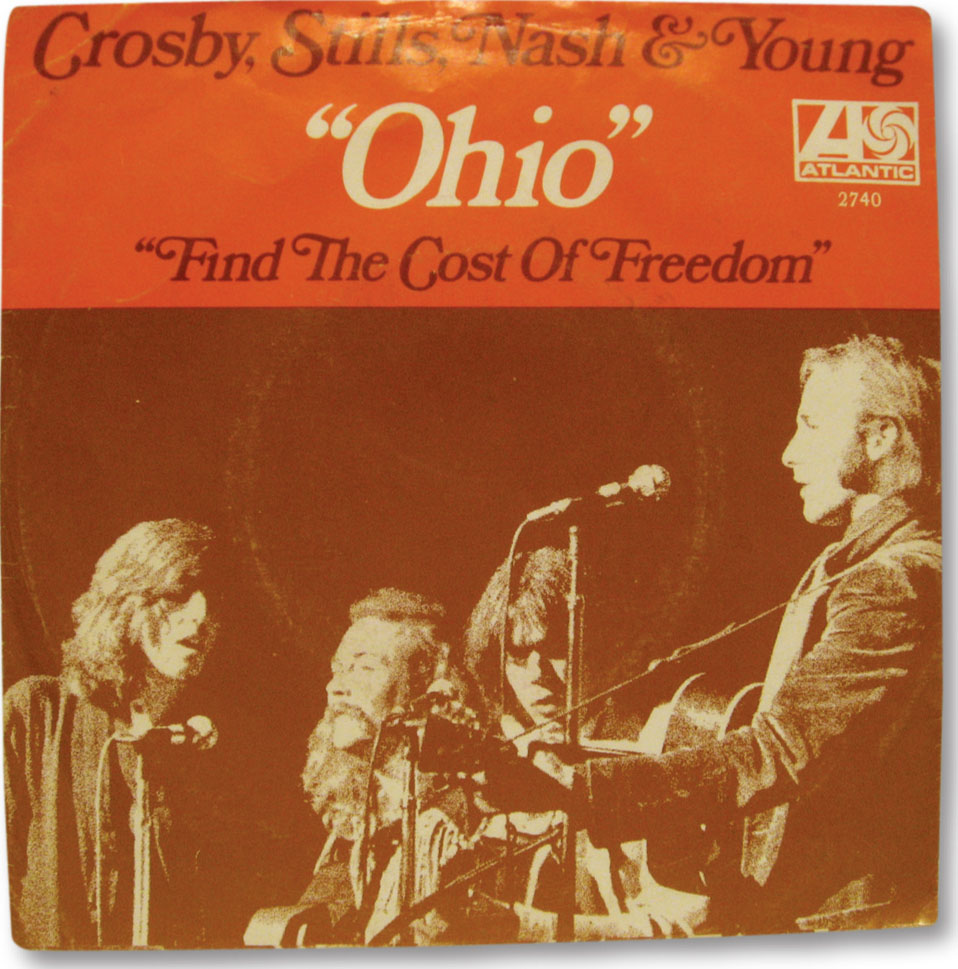

CSNY with drummer Dallas Taylor and bassist Greg Reeves, July 14, 1969. © Henry Diltz/Corbis

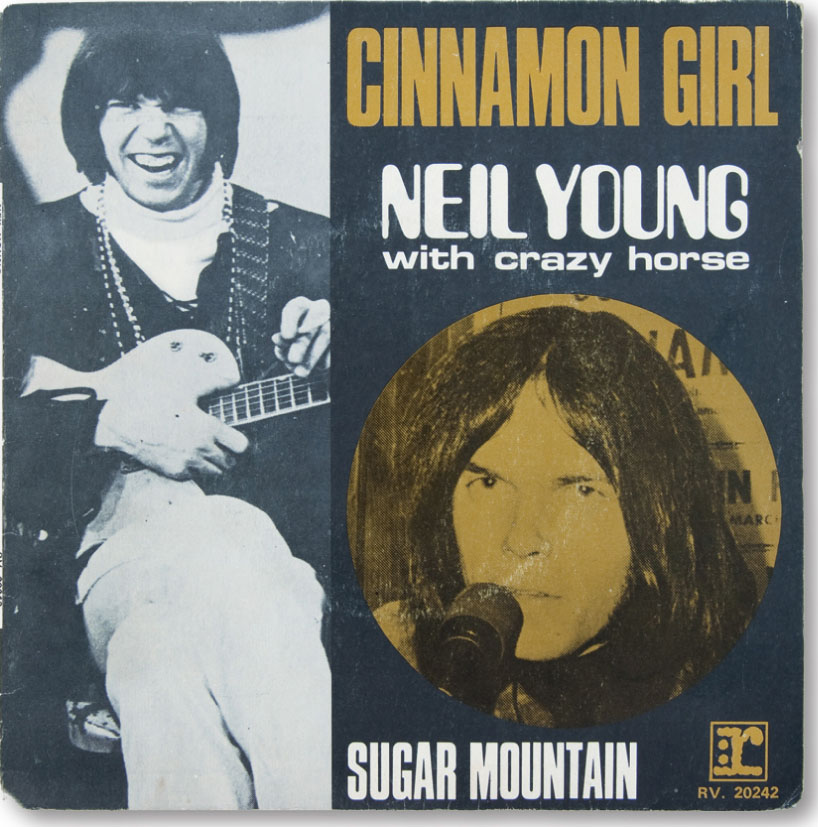

Wherever the Rockets might have gone, it seems unlikely that the band could have reached, on its own, the heights to which Young took Crazy Horse on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. Recorded quickly with the band playing live and loud in the studio (although the vocals were still overdubbed), it’s the antithesis of Young’s debut album. Among the songs are several of his most enduring classics: “Cinnamon Girl,” “Cowgirl in the Sand,” and “Down by the River,” all of which were written in a single day while Young was sick with the flu and a high fever. In the liner notes to Decade, Young said he wrote “Cinnamon Girl” “for a city girl on a peeling pavement coming at me, thru Phil Ochs’ eyes playing finger cymbals. It was hard to explain to my wife.”

No doubt.

The title track reflects Young’s desire to escape the empty hustle of the L.A. scene, while two songs, “Round & Round” and “Running Dry,” pay their respects to two bands—the Springfield and the Rockets, respectively—that died in part because of his actions.

“River” and “Cowgirl,” the album’s true showcase numbers, unwind into extended jams, allowing Young to fly high and far on Old Black, safe in the knowledge that he is tethered to the earth by the Horse’s leaden, locked-in groove. And it’s not just his playing that’s improved here. Bolstered by the vocal harmonies of the Horse, he sings with heretofore unheard confidence. “There’s a chemistry when I play with [Crazy Horse] that frees me to go places I don’t go with anybody else,” Young told American Masters. “It’s just a matter of choosing the ride.”

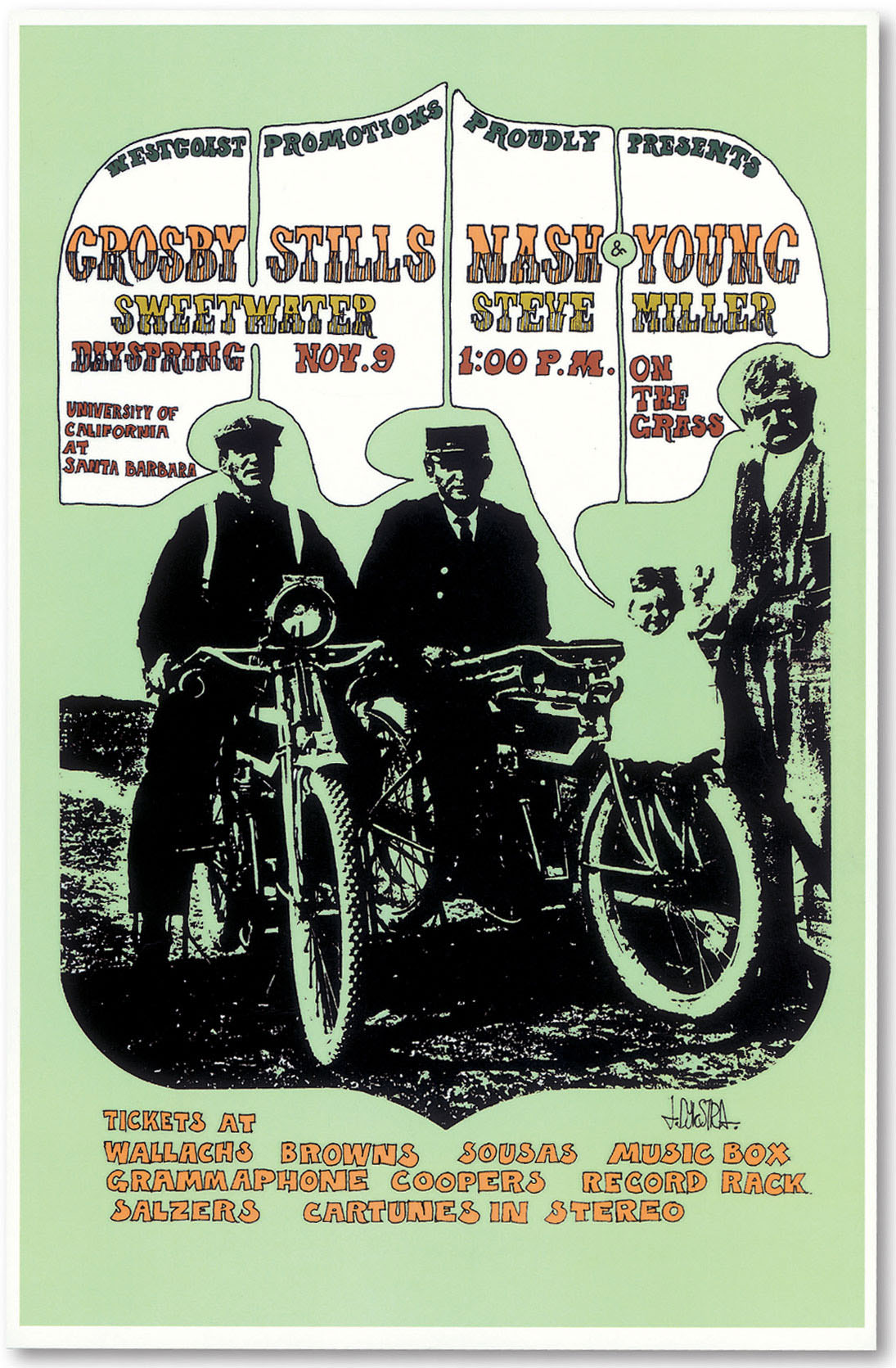

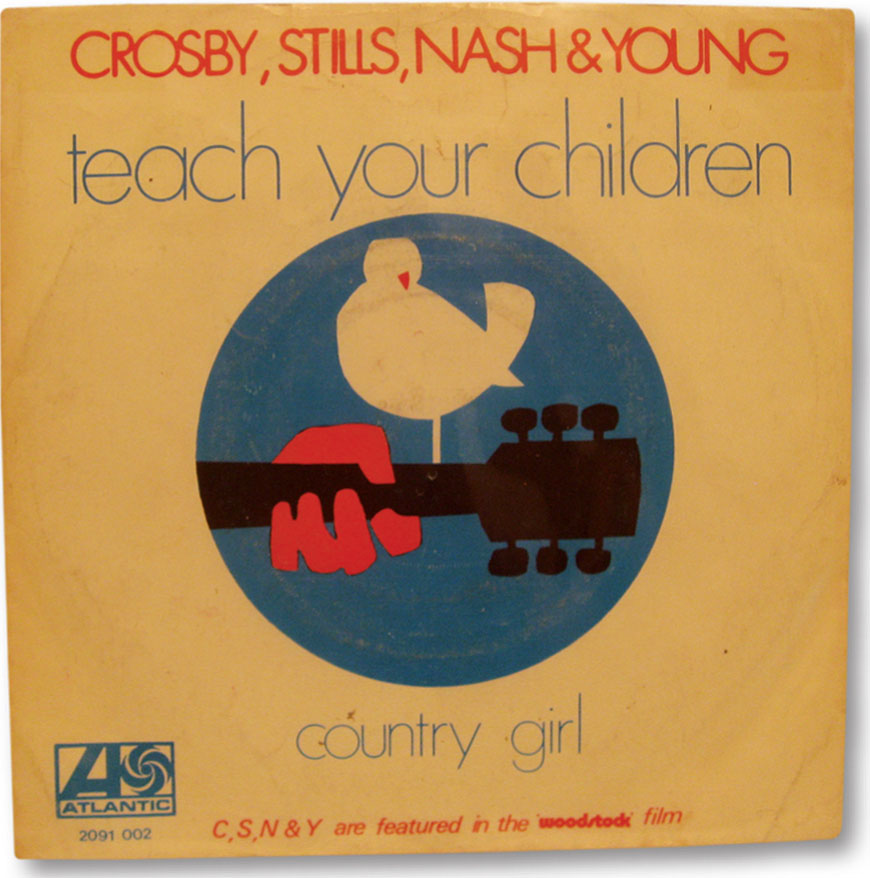

With the Horse in full gallop, Young’s next move proved nothing short of astonishing. He set the band aside and agreed to work again with his chief Springfield antagonist, Stephen Stills. This time, though, it would be in the context of the most popular band in the land: the newly constituted Crosby, Stills & Nash.

In the wake of the Springfield’s demise, Stills had taken up with former Byrd David Crosby, who had been cast out of that band over creative and personal differences, and Graham Nash of the Hollies, who felt the staid English group was holding him back creatively. Brought together by Crosby’s then-girlfriend Joni Mitchell and musical matchmaker Mama Cass Elliot (although that tale, like Young and Stills’ cute meet on Sunset Boulevard, has its own variations), the trio instantly recognized its potential and joined forces. Their album Crosby, Stills & Nash was a smash hit out of the gate. But the idea of touring presented a problem: Stills had played most of the instruments in the recording studio; in concert, they’d need a band.

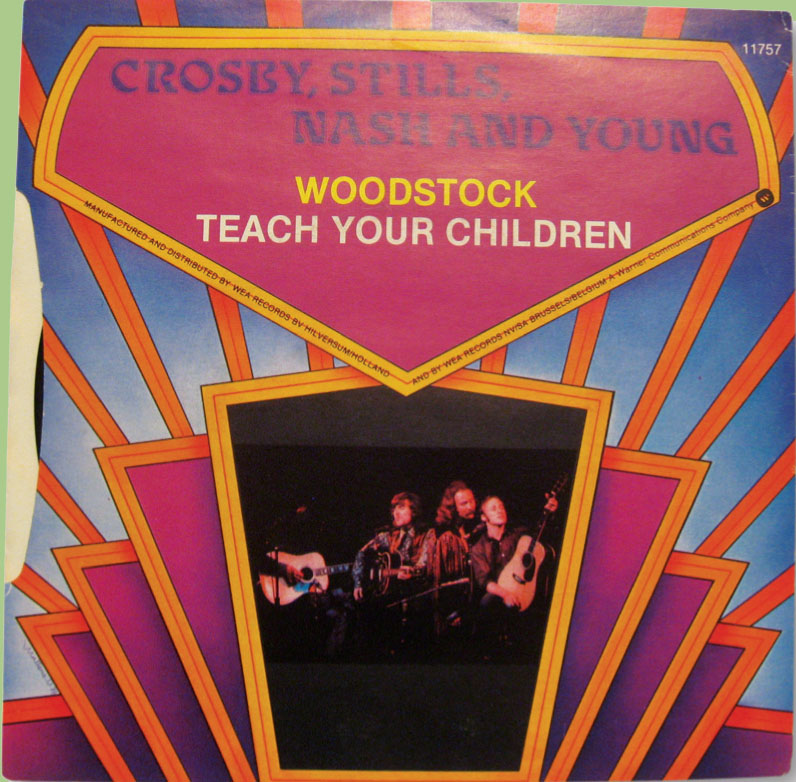

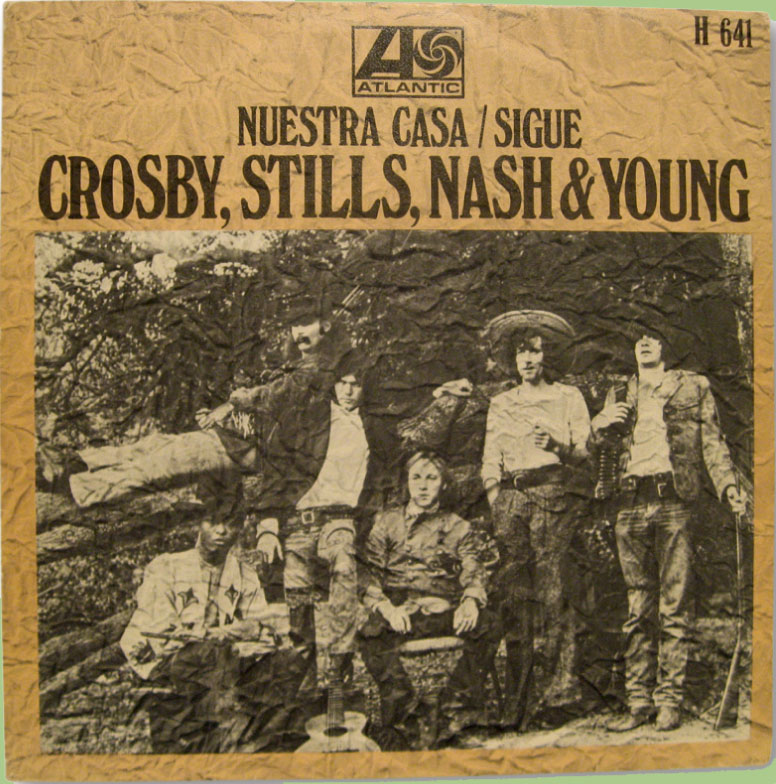

France, 1970.

Germany, 1972.

Both courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

With the Horse in full gallop, Young’s next move proved nothing short of astonishing. He set the band aside and agreed to work again with his chief Springfield antagonist, Stephen Stills.

Despite their fractious past, Stills wanted Neil Young for the job. As offered, it was something less than a full partnership. Young rejected that proposal and had manager Elliot Roberts inform CSN that if he were to join, they’d have to add a Y to the group name.

Choosing to remember the good times, Young claimed that reuniting with Stills was a major factor in his decision to join the group. But he also acknowledged that the job put him in the catbird seat: There was much to gain and little to lose in joining a group already on top. Young told

Rolling Stone:

I knew it would be fun. I didn’t have to be out front. I could lay back. It didn’t have to be me all the time. They were a big group and it was easy for me. I could still work double time with Crazy Horse. With CSNY, I was basically just an instrumentalist that sang a couple of songs with them. It was easy. And the music was great. CSNY, I think, has always been a lot bigger thing to everybody else than it is to us. People always refer to me as Neil Young of CSNY, right? It’s not my main trip. It’s something that I do every once in a while. I’ve constantly been working on my own trip all along.

His refusal to commit 100 percent to the band gave Young an inordinate amount of power, and he had no misgivings about wielding it. At the freshly minted supergroup’s second gig, the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in Bethel, New York, Young refused to allow filmmakers to document his portion of the performance. As a result, only CSN are seen in the resulting movie. Young told Mojo:

I didn’t allow myself to be filmed because I didn’t want [the cameramen] on the stage. Because we were playing music. I thought, if they were going to film they’d have to stay off the stage—get away, don’t be in my way, I don’t want to see your cameras, I don’t want to see you. I’m still very much the same way. I really didn’t see what television and films had to do with making music. To me it was a distraction—because music is something that you listen to, not that you look at. You’re there, you’re playing and you’re trying to get lost in the music, and there’s this dickhead with a camera right in your face. So the only way to make sure that that wouldn’t happen is tell them that I wouldn’t be in the film, so there was no sense in filming me—avoid me, stay away from my area. And it worked.

As the band’s popularity grew, so did the quartet’s individual egos. As vocalists, CSN (and sometimes Y) were capable of tight and gorgeous harmonies. As instrumentalists, Stills and Young’s guitar duels—whether born of camaraderie or competition—became the stuff of legend. But inevitably, it all went to their heads, as did, in the case of Crosby and Stills in particular, copious amounts of cocaine and other drugs. “The reaction to CSNY was ridiculous,” Young told American Masters. “It was so over the top, and then we all became distracted by that. We were just showy. And it was because we had no idea what we were doing. It’s not because there was anything wrong with anybody in the band. It’s just that what we were confronted with . . . changed us. The crowd, the adulation, the roaring sound. It changed us.”

The group also angered Young by signing on for glitzy showbiz gigs, such as two appearances on TV’s This Is Tom Jones. Young, after all, once left Buffalo Springfield temporarily because he didn’t want to appear on the far more legit Tonight Show. On the second Jones show, the ultraswanky host even joined the band to sing, “Long Time Gone.” Neil reluctantly showed up for the TV appearances.

Through all the ego trips, arguments, and temporary breakups—as well as more serious matters, such as the death of Crosby’s girlfriend, Christine Hinton, in an auto accident—the band did manage to record the album Déjà Vu. Predictably, it was a torturous experience. “I remember one session towards the end of the Déjà Vu record where we were arguing,” Nash told American Masters. “There were too many drugs involved. Stephen was staying up all night trying to write and trying to create. And there was one point towards the end there where I started crying and I said . . . that we’re blowing this.”

Artist: Peter Pontiac (www.peterpontiac.com)

CSNY, Woodstock Music & Art Fair, Yasgur’s Farm, White Lake, New York, August 17, 1969. Photo by Barry Z Levine/Getty Images

CSNY rehearses “Down by the River” for the premiere episode of ABC’s Music Scene, Los Angeles, September 22, 1969. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“Young guys, big egos,” Crosby concurred. “Lots of money. Very easy, very unstable, very easy for us to come unglued at any point. ‘Well, I don’t need that sonofabitch.’ . . . In my case, hard drugs were damaging me enormously at that point and made it difficult for me to do a good job or be a good brother to my brothers.”

As for Young, he remained reticent throughout the sessions, hoarding songs for his future solo releases.

He also chafed at the method of recording, which emphasized overdubbed perfection over the live, on-the-fly method he now preferred. Young told Rolling Stone:

The band sessions on that record were

“Helpless,” “Woodstock” and “Almost Cut My Hair.” That was Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. All the other ones were combinations, records that were more done by one person using the other people. “Woodstock” was a great record at first. It was a great live record, man. Everyone played and sang at once, Stephen sang the shit out of it. The track was magic. Then, later on, they were in the studio for a long time and started nitpicking. Sure enough, Stephen erased the vocal and put another one on that wasn’t nearly as incredible. They did a lot of things over again that I thought were more raw and vital sounding. But that’s all personal taste. I’m only saying that because it might be interesting to some people how we put that album together. I’m happy with every one of the things I’ve recorded with them. They turned out really fine. I certainly don’t hold any grudges.

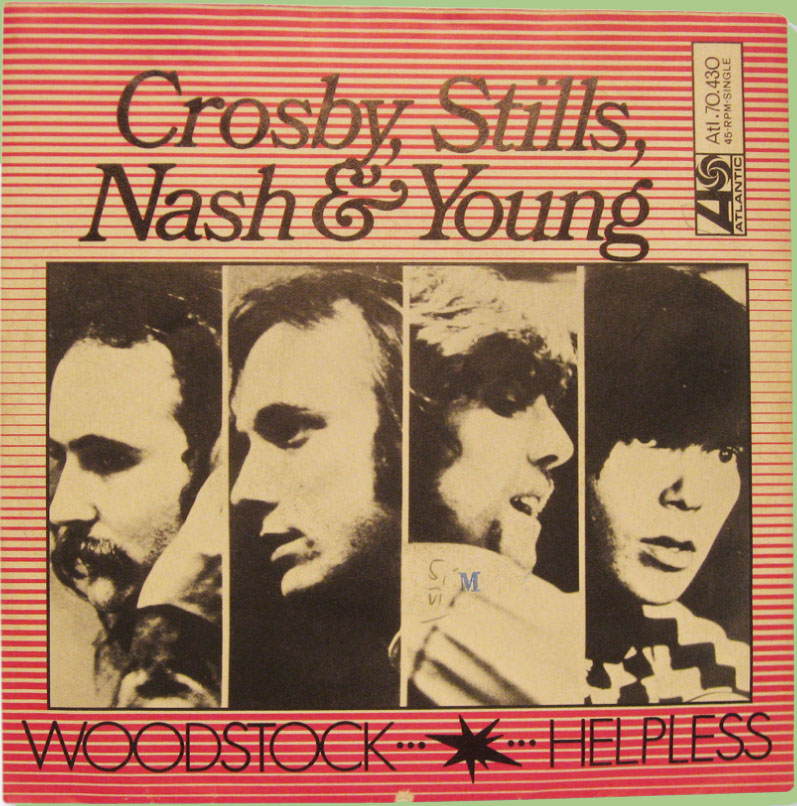

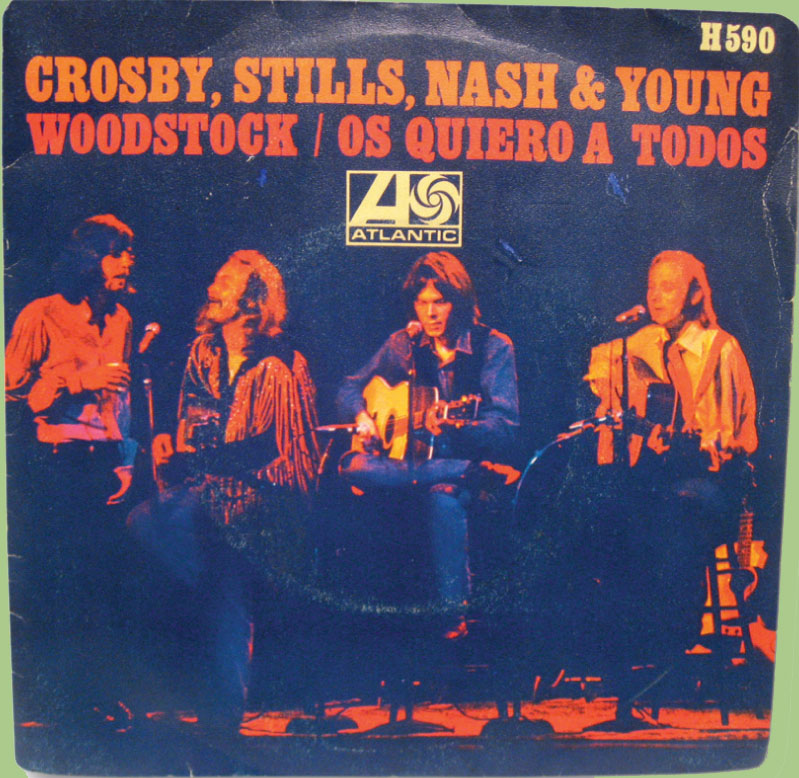

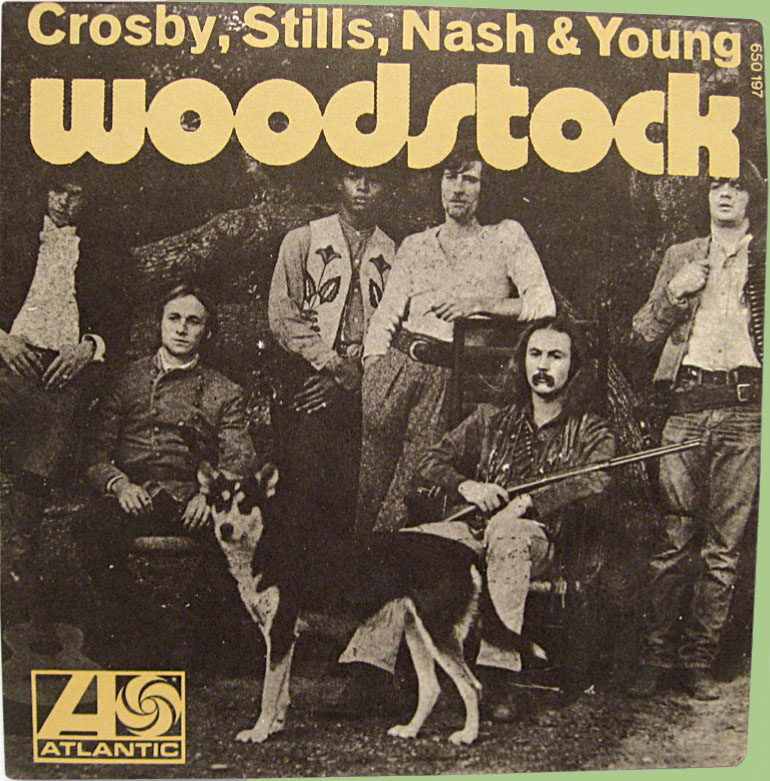

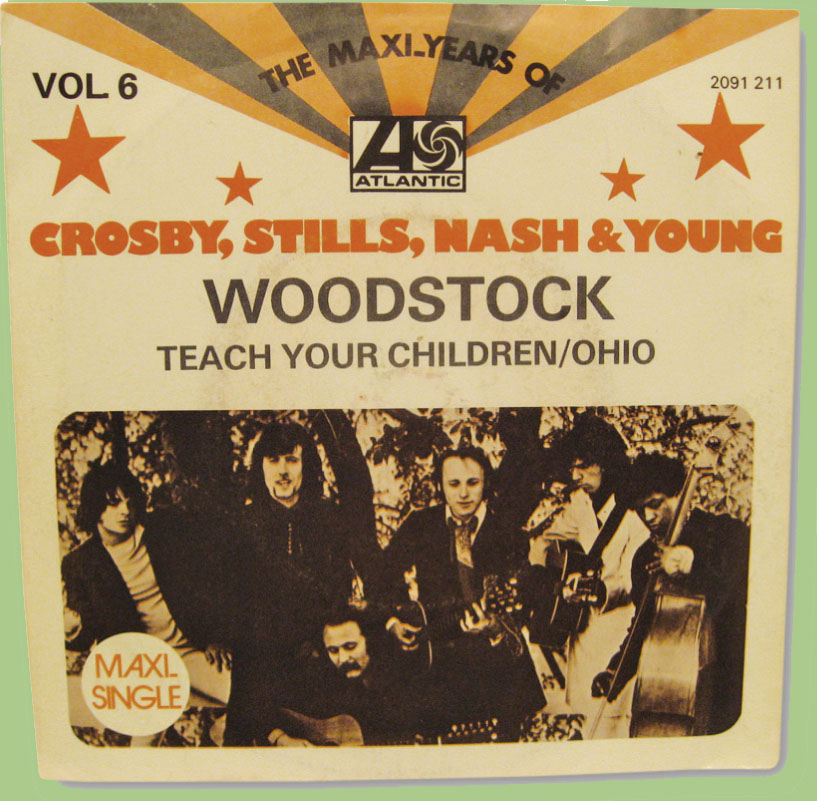

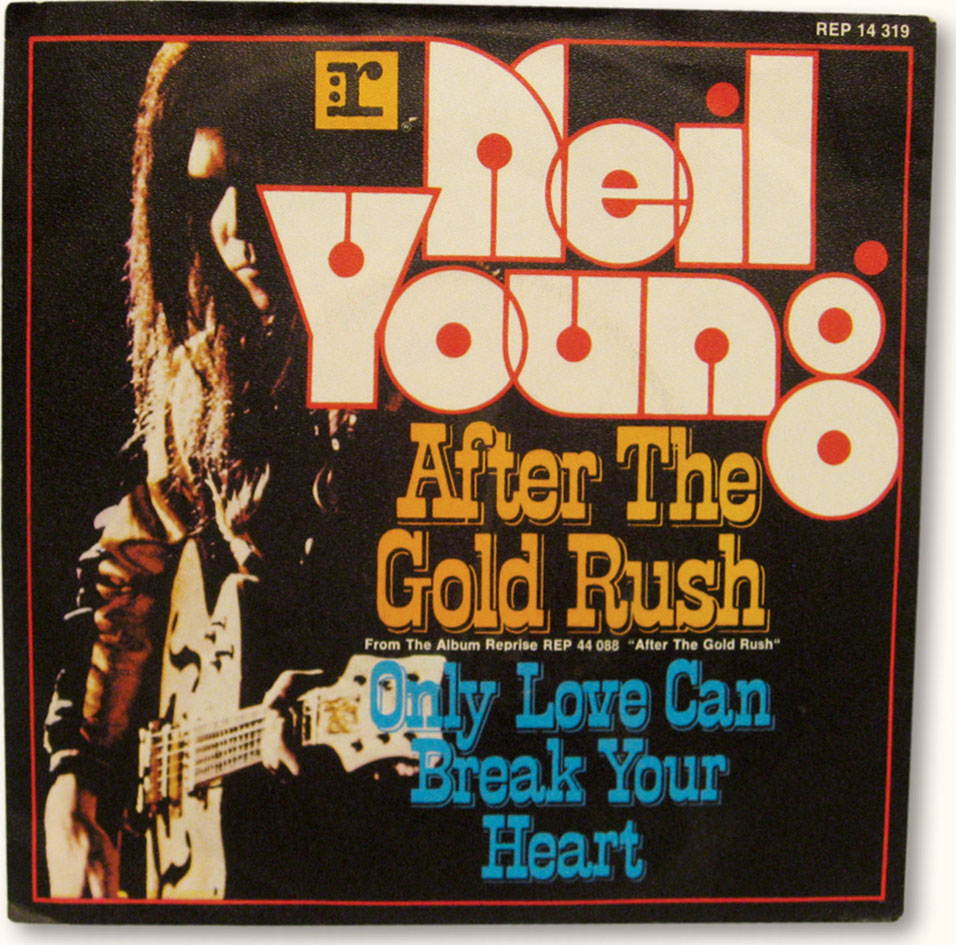

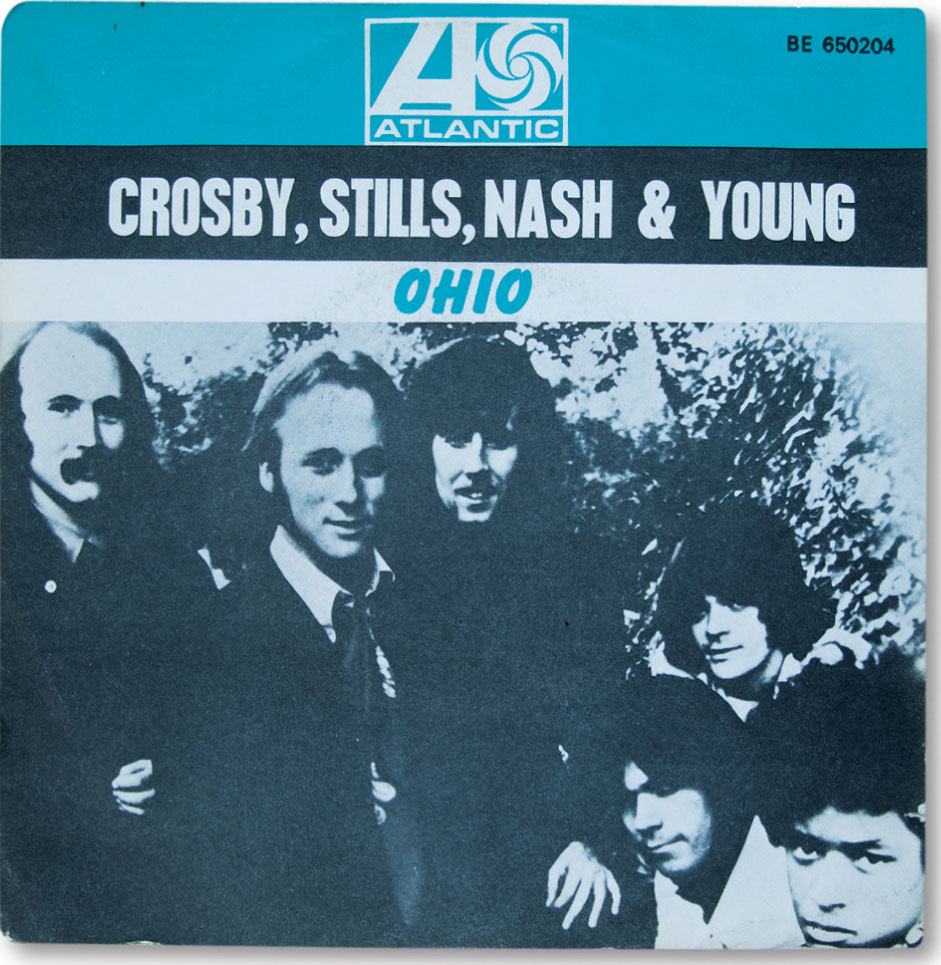

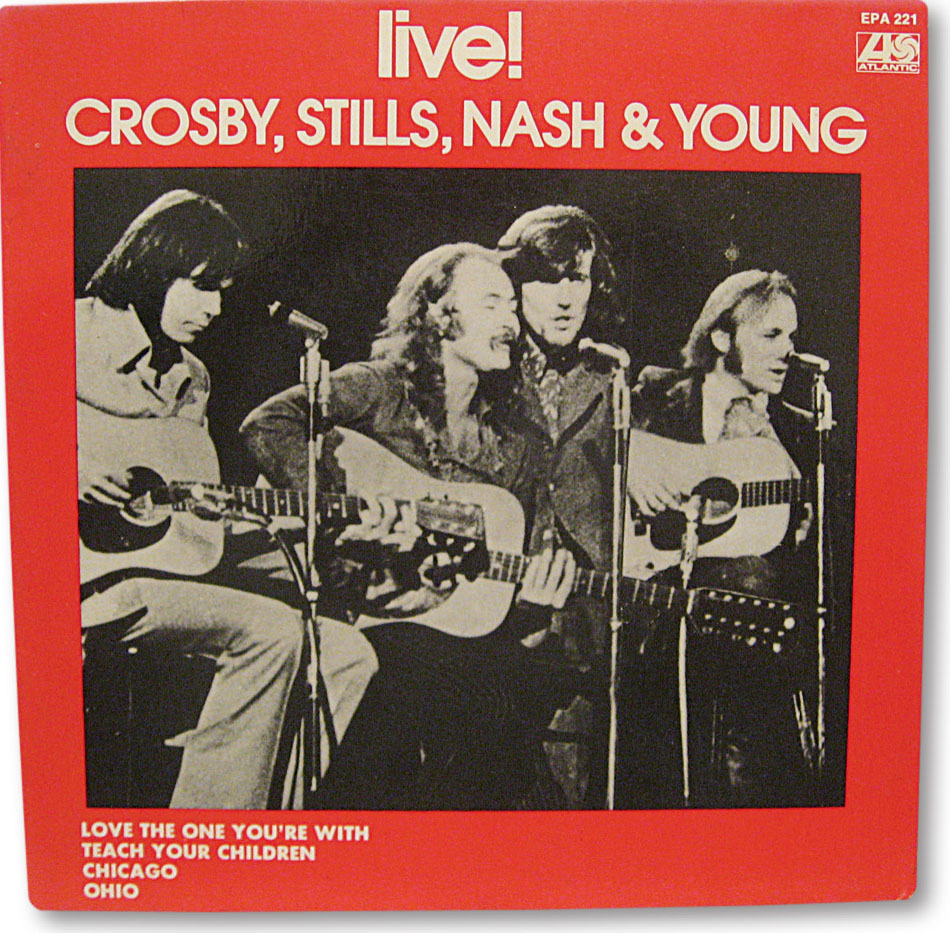

U.K., 1970.

France, 1970.

Germany, 1970.

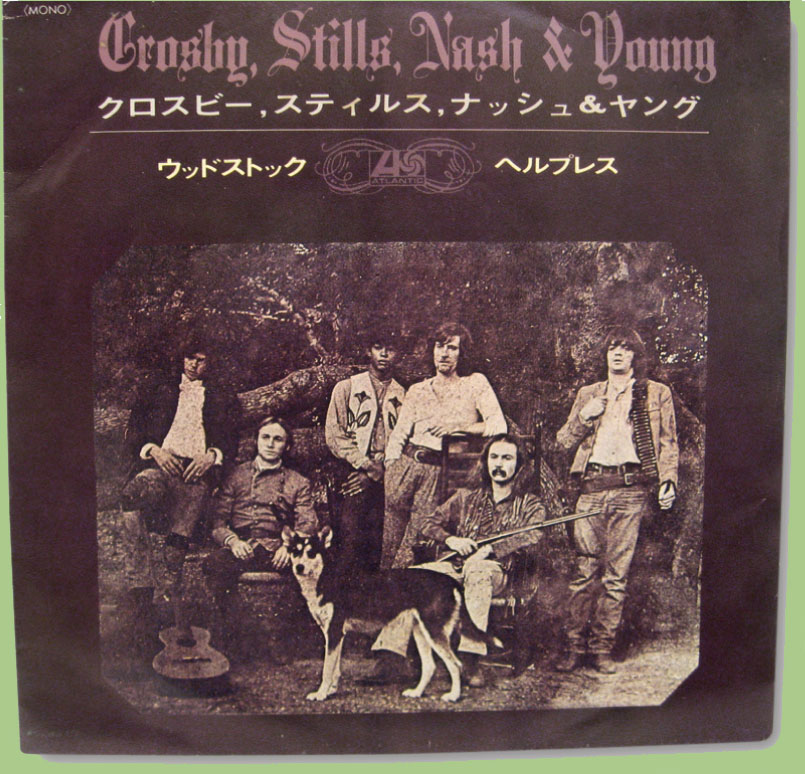

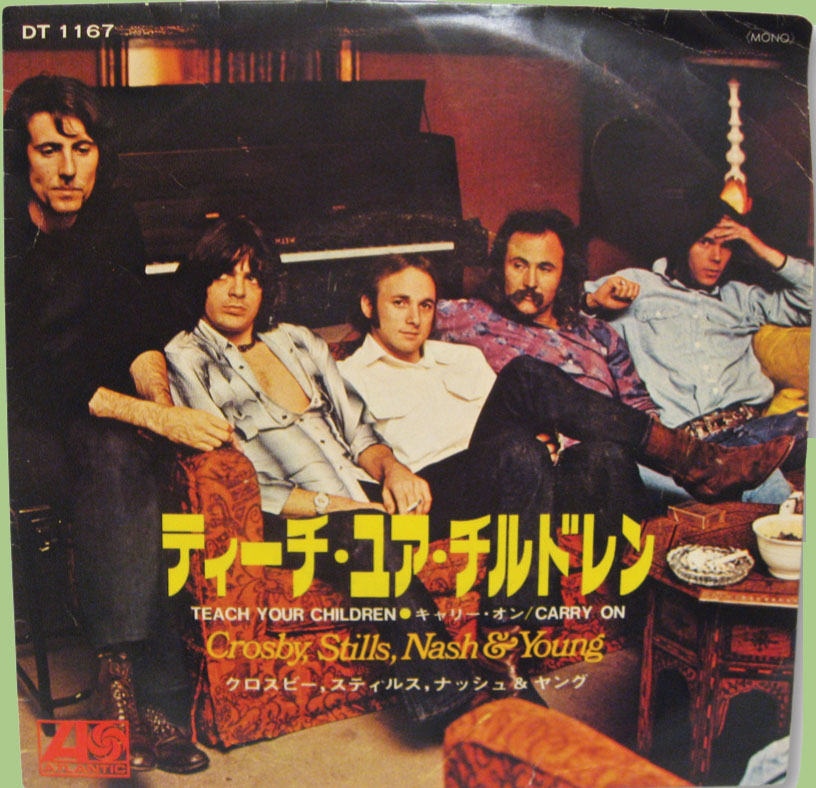

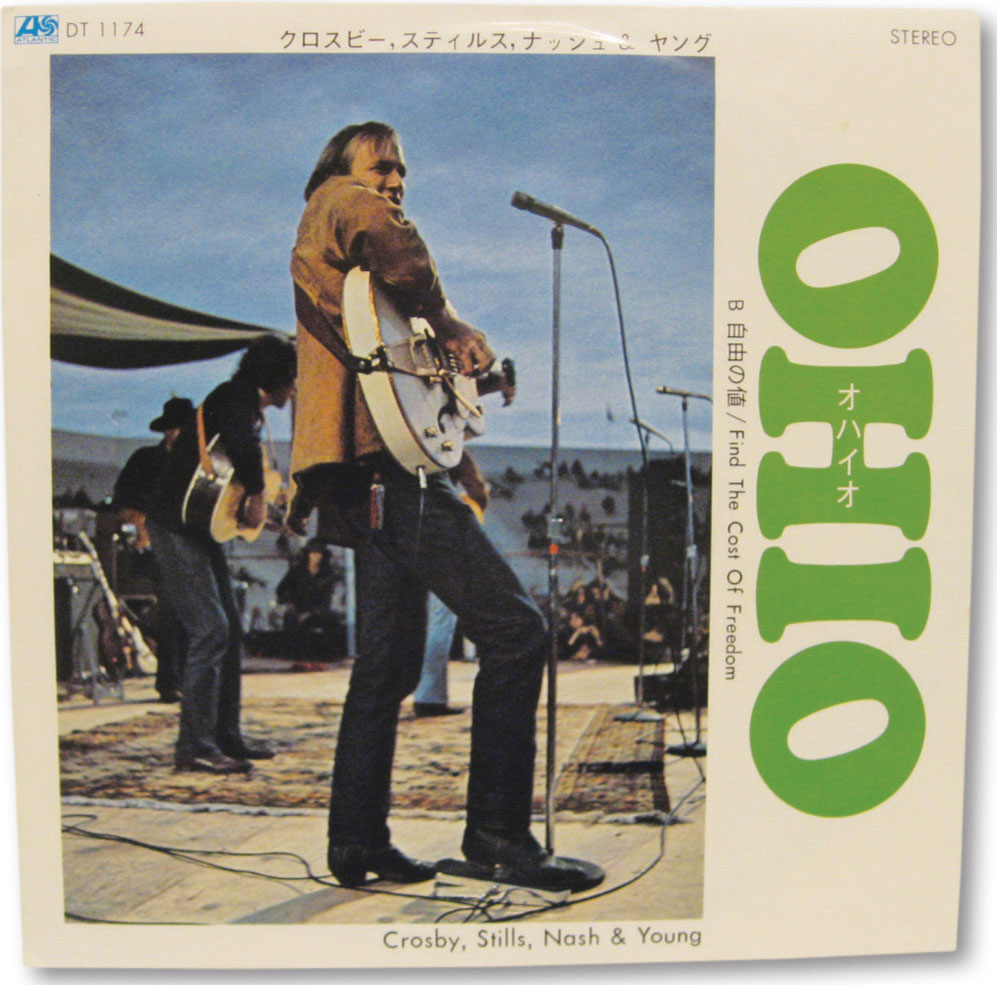

Japan, 1970.

All courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

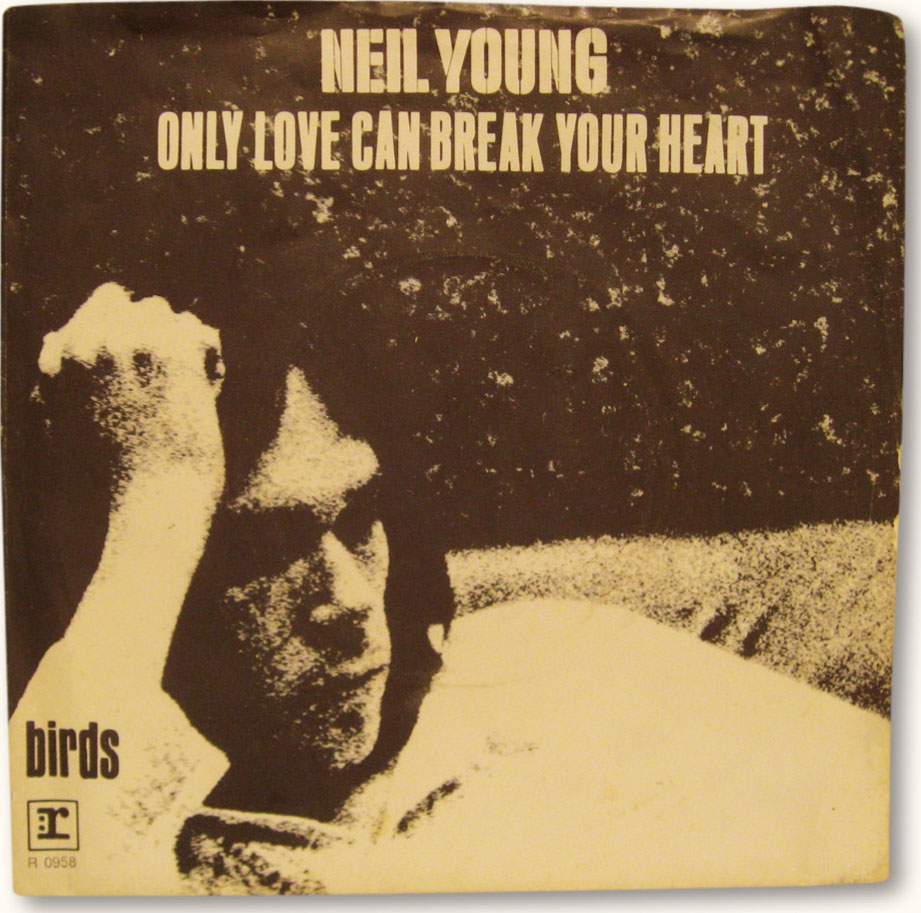

Portugal, 1970.

The Netherlands, 1970.

Spain, 1970.

Germany, 1970.

Spain, 1970.

Backed with “Helpless,” France, 1970.

Japan, 1970.

All courtesy Robert Ferreira

The Netherlands, 1970.

Japan, 1970.

Young’s contributions were the exquisite “Helpless,” his loving tribute to Omemee, the “town in North Ontario” where he most enjoyed growing up; and “Country Girl (I Think You’re Pretty)”—a suite of songs that, despite Young’s claims of satisfaction, suffered a bad case of “overdub city.”

Divisiveness often threatened to swallow CSNY whole, but Young tried to separate the creative friction from outright hostility. “Everyone always concentrates on this whole thing that we fight all the time among each other,” he told Rolling Stone. “That’s a load of shit. They don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about. It’s all rumors. When the four of us are together it’s real intense. When you’re dealing with any four totally different people who all have ideas on how to do one thing, it gets steamy. And we love it, man. We’re having a great time.”

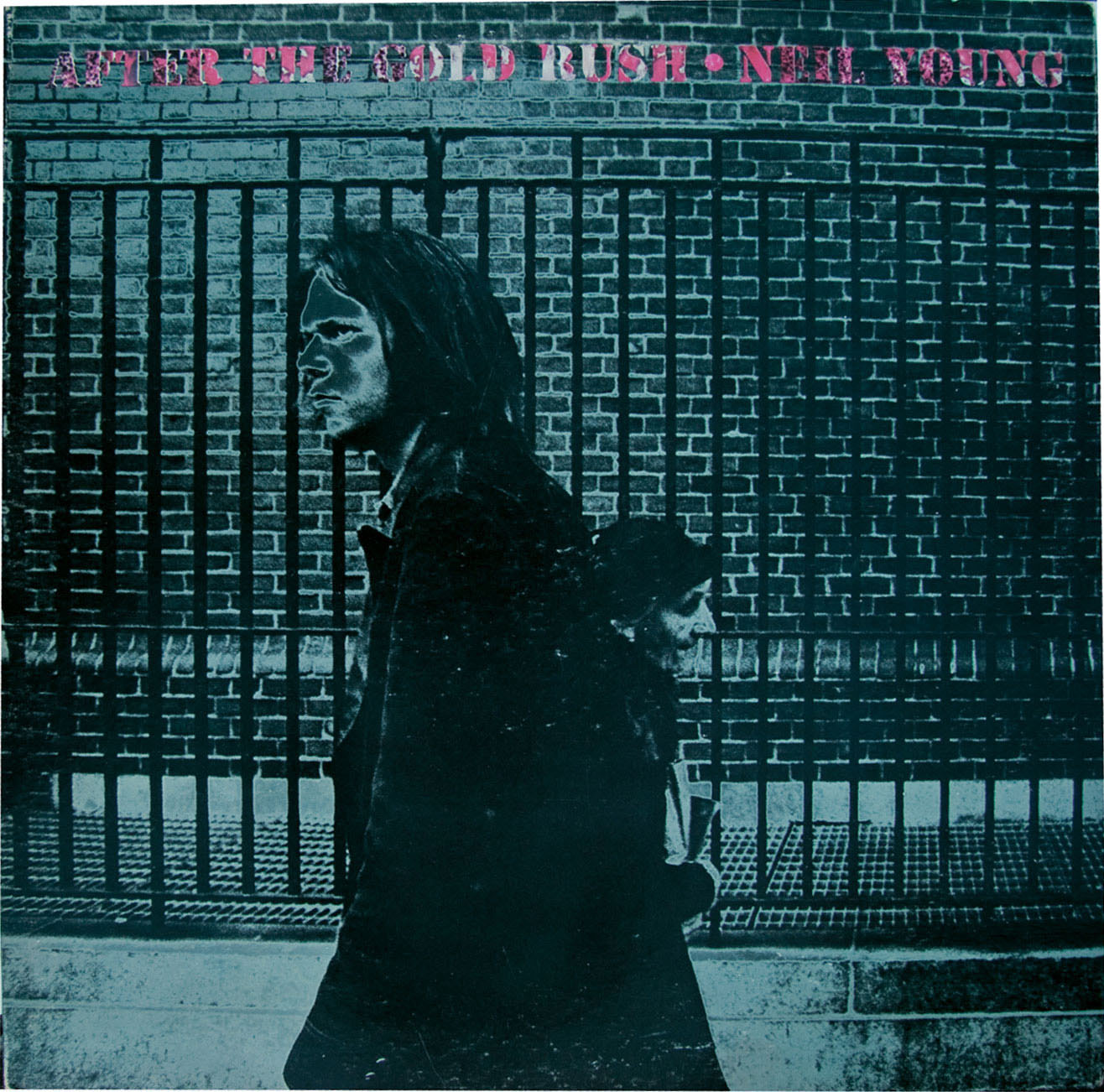

Young shuttled back and forth between CSNY and Crazy Horse, recording a batch of songs intended for his next album, After the Gold Rush. The title and the inspiration for some of the songs was a script written by actor and Topanga resident Dean Stockwell. Young told Mojo:

It was all about the day of the great earthquake in Topanga Canyon when a great wave of water flooded the place. It was a pretty “off-the-wall” concept, they tried to get some money from Universal Pictures. But that fell through because it was too much of an art project. I think, had it been made it would stand as a contemporary to Easy Rider and it would have had a similar effect. The script itself was full of imagery, “change.” . . . It was very unique actually. I really wish that movie had been made, because it could have really defined an important moment in the culture.

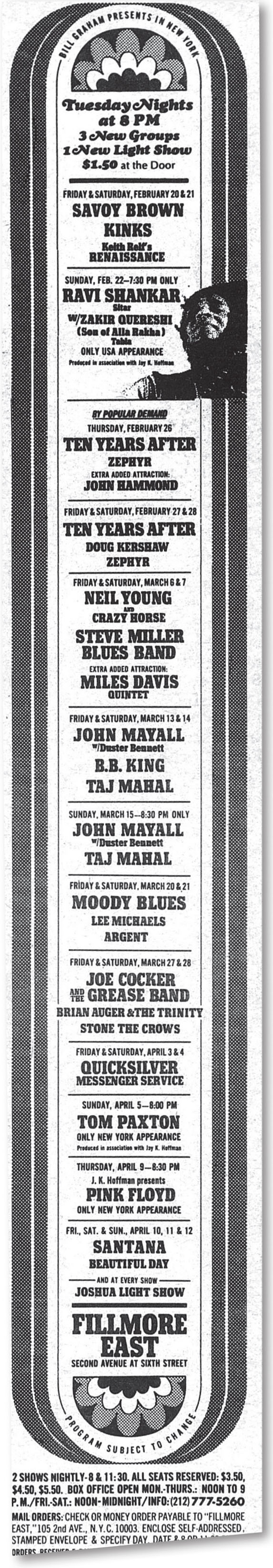

On tour, the Horse was joined by Jack Nitzsche on piano and played some torrid concerts, including two in New York that would eventually see the light of day as Live at the Fillmore East March 6 & 7, 1970. The shows represent the original Crazy Horse at its creative peak.

But it was short-lived. Danny Whitten had begun using heroin, and his ability to play—and indeed, to even maintain—atrophied quickly. When Whitten nodded off onstage, Young became resolved; as soon as the tour ended, he fired the band.

After scrapping most of the earlier sessions with Crazy Horse, Young began the Gold Rush album again, this time recording in the basement of his house in Topanga. Along for the ride this time were Ralph Molina, CSNY bassist Greg Reeves, and Nils Lofgren, a seventeen-year-old guitarist from Washington, D.C., whom Young had taken under his wing. The songs were cut live, including the vocals, giving Young the sense of immediacy and spontaneity he’d always craved. As if to up the ante, Young asked Lofgren to play piano on the album—something Lofgren didn’t know how to do.

London, January 1970. Photo by Dick Barnatt/Redferns/Getty Images

California, 1970.

New York, 1970.

With Crazy Horse, California, March 1970.© Robert Altman/Retna Ltd.

CSNY Carry On European Tour, Falkonercentret, Copenhagen, Denmark, January 16, 1970.Photo by Jan Persson/Redferns/Getty Images

Germany, 1969. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

This group is like juggling four bottles of nitroglycerin.

—David Crosby

Yeah—if you drop one, everything goes up in smoke.

—Graham Nash

We knew who we were. We knew nobody in the world was doing what we were doing. No one had four guys writing those kind of songs that were also that good as musicians, all at the same time. There was nobody like us. So we were a little punkish about it. We thought we were kings of the world, so it was exciting to us.

—Graham Nash

A large part of our job is to just make you boogie, to be a party, but another part of it is to be the troubadour, the town crier—“It’s 11:30 and all’s well!” or “It’s 12 o’clock and there’s a chimpanzee loose in the White House and things aren’t too good!” That’s part of our job, has been for thousands of years.

—David Crosby

I don’t like to compare us to other bands. We are who we are. When I play in this band, it’s a special thing. It goes back to our roots; we’ve been friends for a long time, Stephen and I, and then the other guys. When they got together with Stephen, and I came and joined them, we already had our history. We already had roots in playing together and developing our music styles and learning how to play guitars together, Stephen and I.

—Neil Young

Our chemistry is really deep respect. We do best when it’s the two of us, especially on electric [guitar]. With the Horse he plays differently ’cause he’s by himself. When he plays with me, he’s really after a balance. It takes us a few rehearsals to get back to our thing, but when we start playing together it’s just as cool as when I played with Jimi [Hendrix] and Eric [Clapton] and every other great guy.

—Stephen Stills

We’re more than friends. We’re brothers. And, unfortunately, brothers fight occasionally. But it’s been [more than] 30 years; something’s going on.

—Graham Nash

There’s a lot of unfinished business. I don’t think we really reached our potential, and so we have a lot of things to show and a lot of things to do. This is why it’s so exciting. I mean, this band can sing like the Byrds and jam like the Dead . . . and hopefully we can get the audience turned on to what we’re doing and have it just be a music thing.

—Neil Young

The reason I play with CSN is because . . . I don’t have to sing every song, because I like playing with them. I like being with guys I’ve known for [so many] years that have gone through so much with me. It’s a rewarding experience. It’s fun to look around and see those guys.

—Neil Young

California, 1969.

Some of the ridiculous little kid games we used to play with each other . . . were really ridiculous and just beyond belief.

—Stephen Stills

Stephen plays a great guitar. I know how to support his guitar playing. I have no problem finding things that will make him sound better just by finding certain little things underneath it that support it. And when I feel like playing lead, he can support me. That’s the way we’ve always done it. Sometimes we both play lead at the same time. I mean, this band can space out for 45 minutes.

—Neil Young

U.K., 1970. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

Oh, man, we loved him. We loved Buffalo Springfield; that was one of the inspirational bands we tried to copy. I love Neil Young and Crazy Horse and even with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, all the stuff they did. He’s one of our favorite writers and musicians, and he’s just an unbelievable influence to me, inspirational. He’s lasted all these years and keeps changing and going forth, then he’ll do his old tunes just like he used to and they’re still great. He’s just saying what he feels, that’s all. He’s like a rock god.

—Gary Rossington, Lynyrd Skynyrd

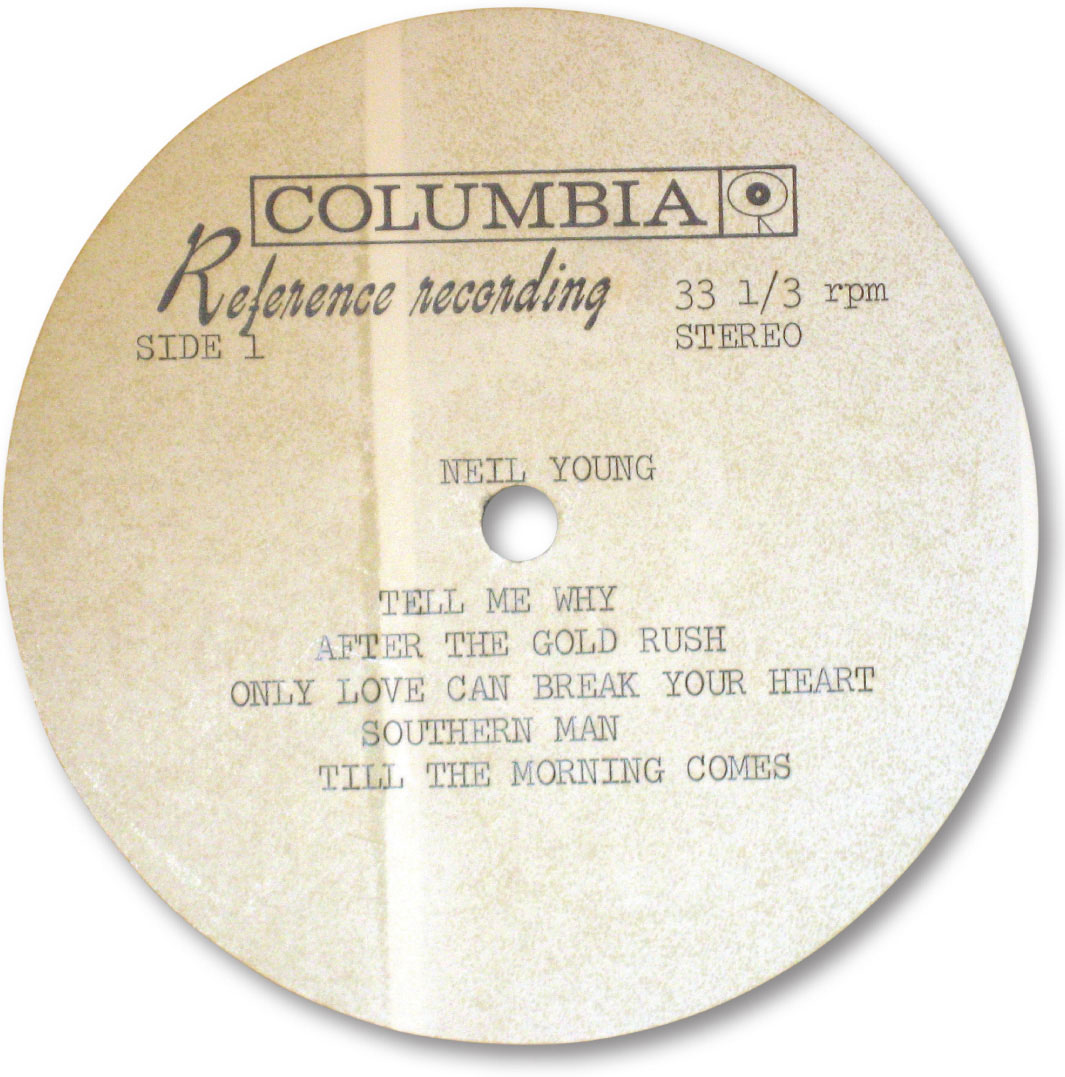

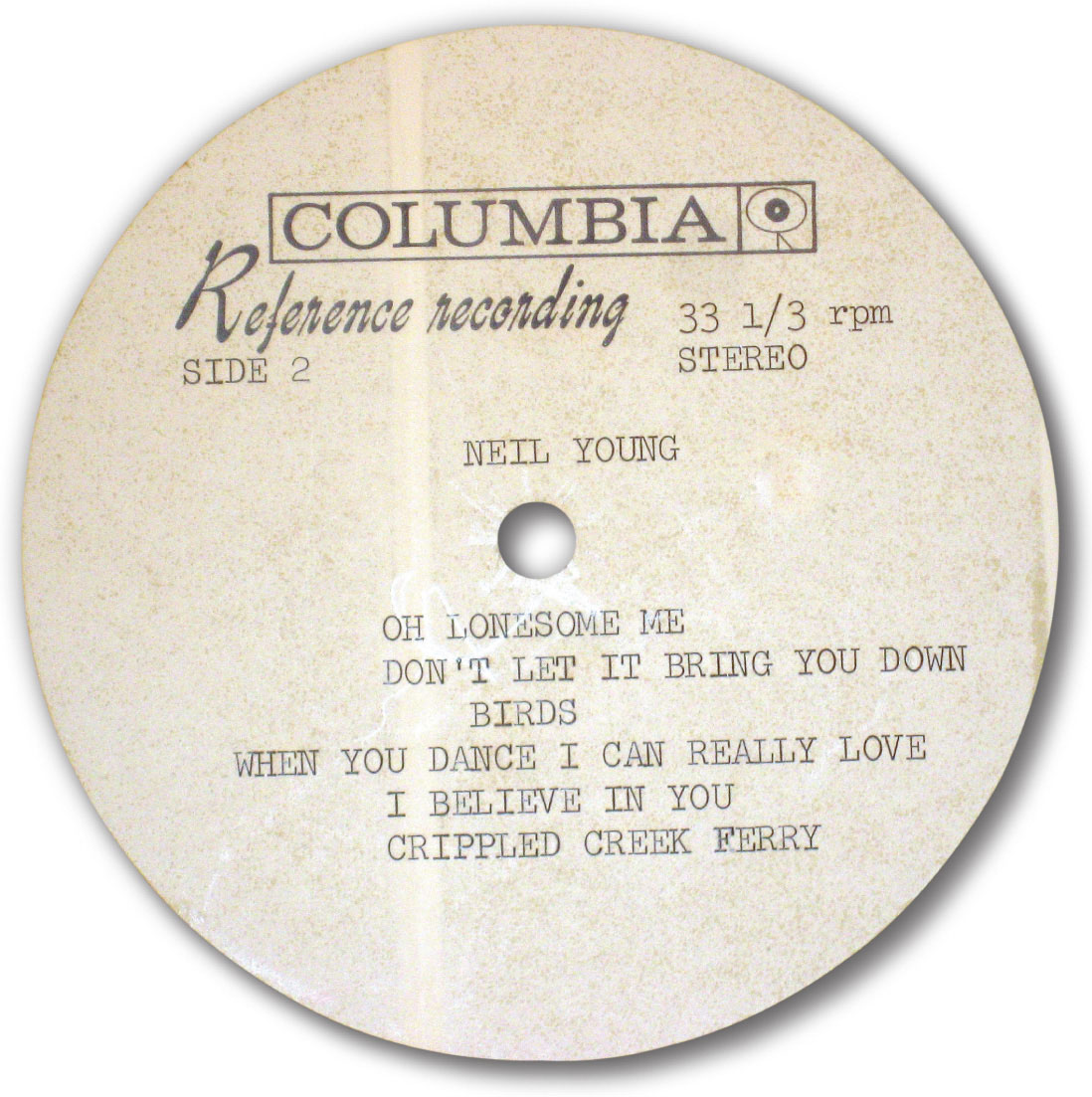

Test pressing of After the Gold Rush. Note the Columbia logo. Test-pressing labels with logos of record companies other than those of the artists reportedly were not uncommon. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

Early After the Gold Rush sleeve that was printed in the wrong color, 1970.Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

Recent reissue of the 1970 TWENSerie After the Gold Rush picture disc originally issued in West Germany, 1970.Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

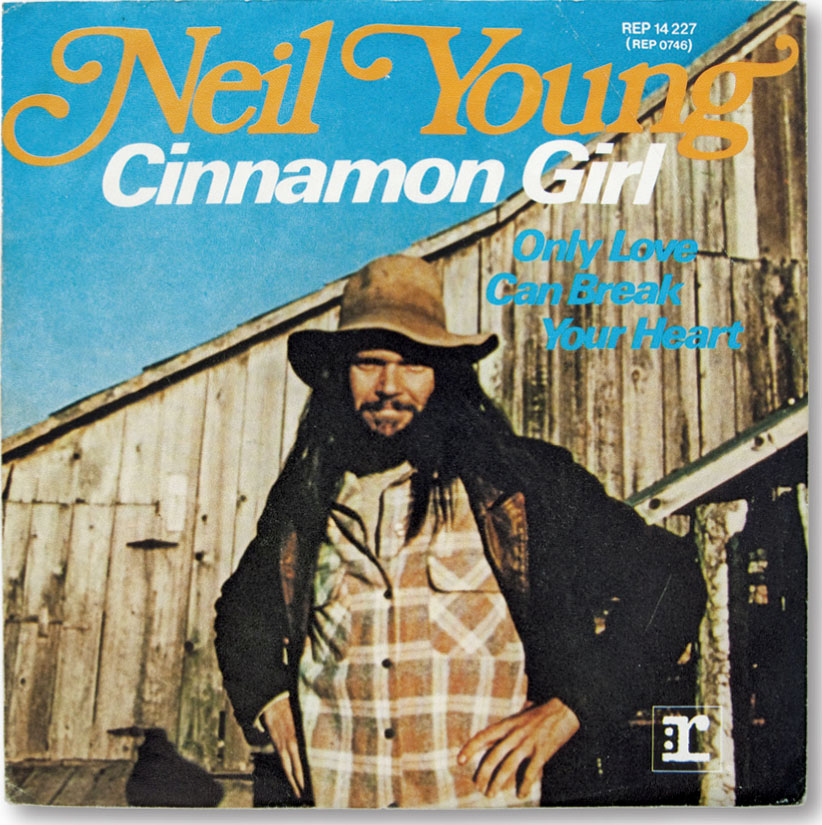

With the spare instrumentation, the songs were left to stand on their own, and Gold Rush is one of Young’s mellowest and most poetic efforts. Among its highlights are the fragile, futuristic title track; a pair of let-you-down-easy breakup tunes, “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” and “Birds”; “Don’t Let It Bring You Down,” a song guaranteed to do just that, as he’d later joke in concert; and a pair of rockers, “When You Dance I Can Really Love” and “Southern Man.” The latter earned Young a musical rebuke from the group Lynyrd Skynyrd, which sang in its hit song “Sweet Home Alabama,” “I hope Mr. Young will remember/A southern man don’t need him around anyhow.” To complete the album, Young pulled a pair of tunes from the sessions with the Horse: the pleading “I Believe in You” and a wonderfully self-pitying cover of Don Gibson’s country weeper “Oh Lonesome Me.”

Young told Rolling Stone that he felt Gold Rush “was a strong album. . . . A lot of hard work went into it. . . . After the Gold Rush was the spirit of Topanga Canyon. It seemed like I realized that I’d gotten somewhere.”

When Young returned to CSNY for another tour, turmoil continued to be the order of the day. Bassist Greg Reeves, emboldened perhaps by his extracurricular adventures with Young, wanted to play some of his own songs with CSNY. Crosby fired him on the spot. Reeves was replaced by Stills’ bassist, Calvin “Fuzzy” Samuels. After that, drummer Dallas Taylor, who had never been a favorite of Young’s, developed a heroin habit and had to go as well. Johnny Barbata, formerly of the Turtles, stepped in, and the show went on.

A reality check was on the way, however. At Kent State University in Ohio, four students were shot and killed by the National Guard during a Vietnam protest rally. Crosby showed Young the now-famous photo of a female student sinking to her knees, her arms outstretched over a fallen protester. Young wrote the song “Ohio” within minutes. It was quickly recorded and released as a single in just a few weeks. For reasons ranging from the way the song was recorded—live in the studio with the entire band present—to the way it allowed him to use music as a means of reportage, Young called it “the best record I ever made with CSNY.”

“Ohio” may have given the group a new sense of purpose, but the tour was the same ego-driven mess as the one before. Several dates were recorded for the bloated live album 4 Way Street. Young was represented on the set by acoustic renditions of “On the Way Home,” “Cowgirl in the Sand,” and “Don’t Let It Bring You Down,” plus electric takes on “Southern Man” and “Ohio.” The album was a huge hit, but the squabbling band members went their separate ways when the tour ended. It would be three years before they joined forces again.

Germany, 1975. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

Germany promo, 1970. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

Germany, 1970. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

Italy, 1970. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

U.S., 1970. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

France, 1970. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

Australia, 1971. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

Japan, 1970. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

Returning to California, Young was determined more than ever to remove himself from the public eye. But he didn’t go back to his house in Topanga. Instead, he bought a ranch just south of San Francisco and moved there—without his wife, Susan. Young’s unrelenting work schedule had driven a wedge between them, and she was put off by his massive fame. She filed for divorce in October 1970.

Young went on a solo tour that included two sold-out shows at Carnegie Hall. While on the road, he saw the film Diary of a Mad Housewife, starring Carrie Snodgress, and, as he’d note in the song “A Man Needs a Maid,” he “fell in love with the actress.” Diary took Snodgress to the peak of her career. She won two Golden Globe Awards for her performance and was nominated for an Academy Award. In a move befitting his status as rock royalty, a smitten Young sent two roadies as emissaries to ask her to call him.

When she did, Young was literally flat on his back. Working on his new property, he’d hurt himself moving a heavy piece of wood. He wound up in a back brace, zoned out on medication. Eventually, he’d require an operation to remove several discs. Still, Young and Snodgress met and quickly fell in love. She moved to the ranch and set about dismantling her career in favor of playing the role of Earth Mother. She became pregnant and even skipped the Academy Awards ceremony. Their son, Zeke, was born in September 1972.

Courtesy Robert Ferreira CSNY compilation, Japan, 1971.

CSNY rehearsal, 1970. © Henry Diltz/Corbis

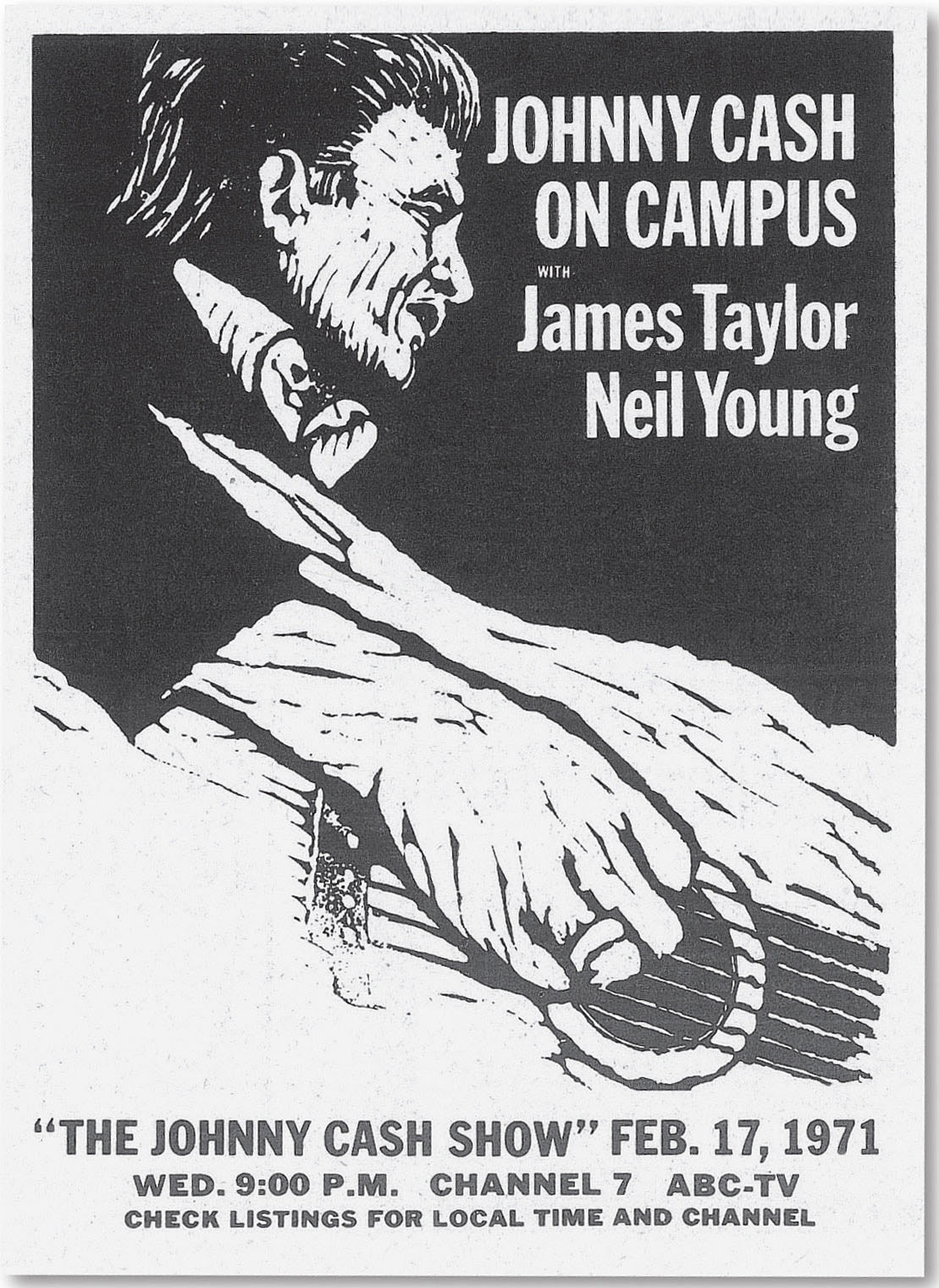

Back on tour, Young stopped in Nashville for an appearance on TV’s The Johnny Cash Show. While in town, he also booked Quadrafonic Sound Studios to record a raft of new songs. Among the musicians hastily pulled into the sessions were bassist Tim Drummond, a veteran of Conway Twitty’s band as well as James Brown’s; pedal steel player Ben Keith, who logged time with Faron Young and Patsy Cline; and drummer Kenny Buttrey, who had played on several Bob Dylan records. Young dubbed the assemblage the Stray Gators, a term associated with stoned musicians that Drummond had heard on James Brown’s tour bus. But Young’s desire for lots of sonic space on his records rubbed some of the Nashville pros the wrong way, especially Buttrey. “He hires some of the best musicians in the world and has ’em play as stupid as they possibly can,” he said.

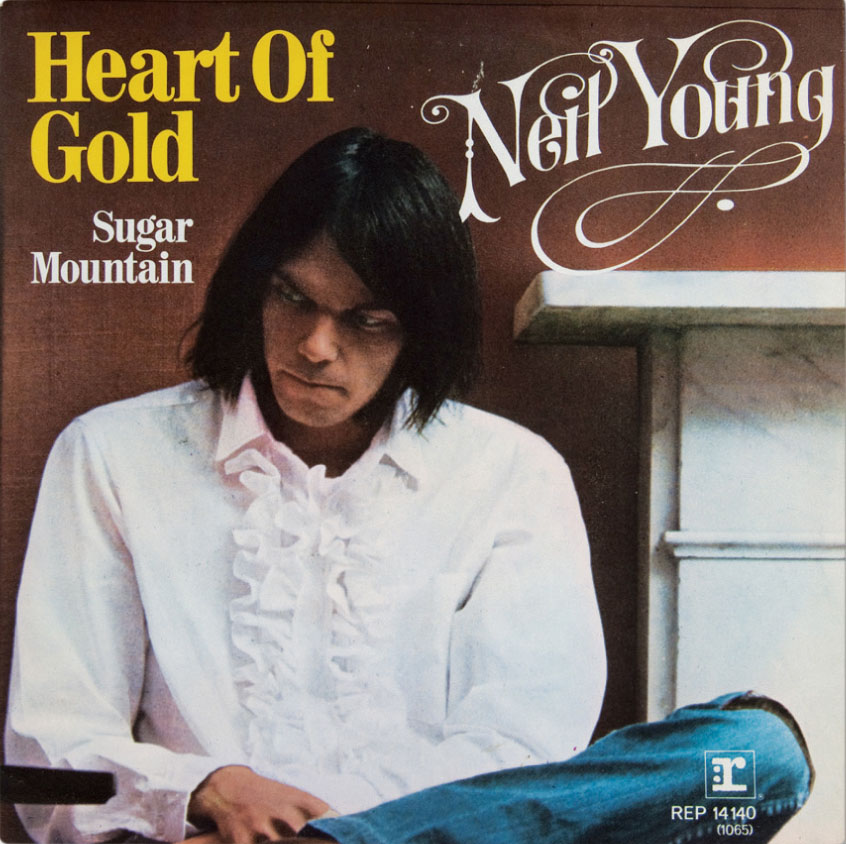

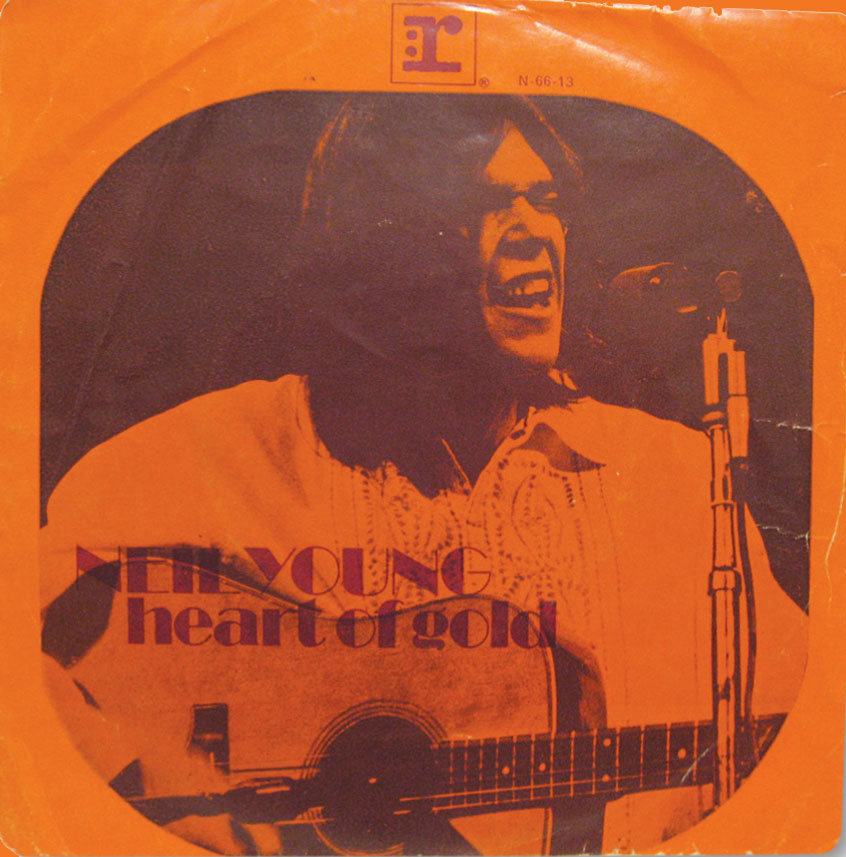

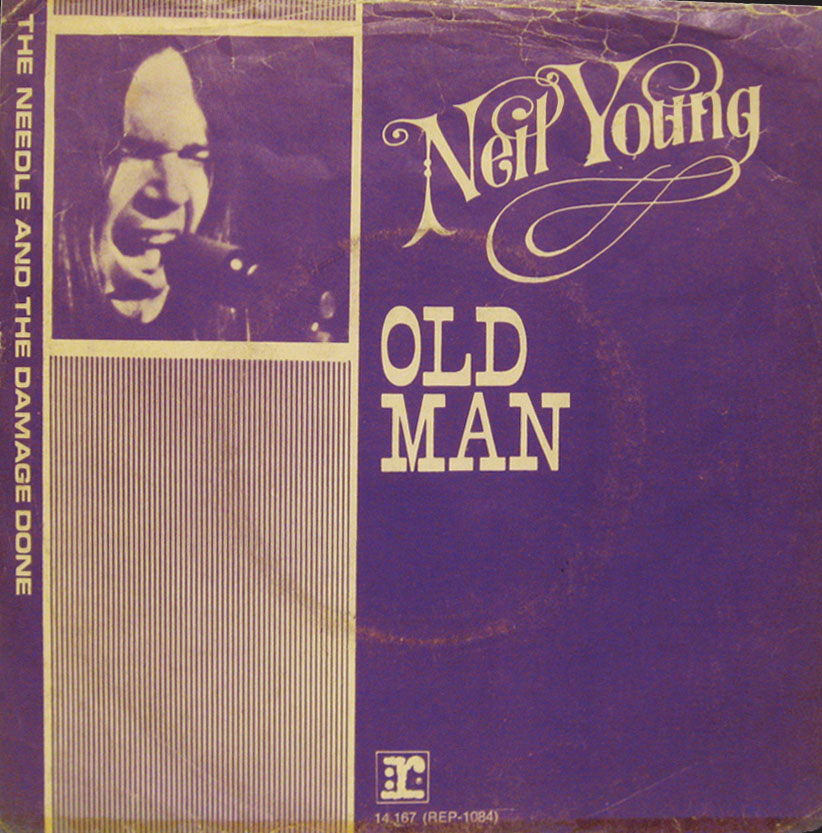

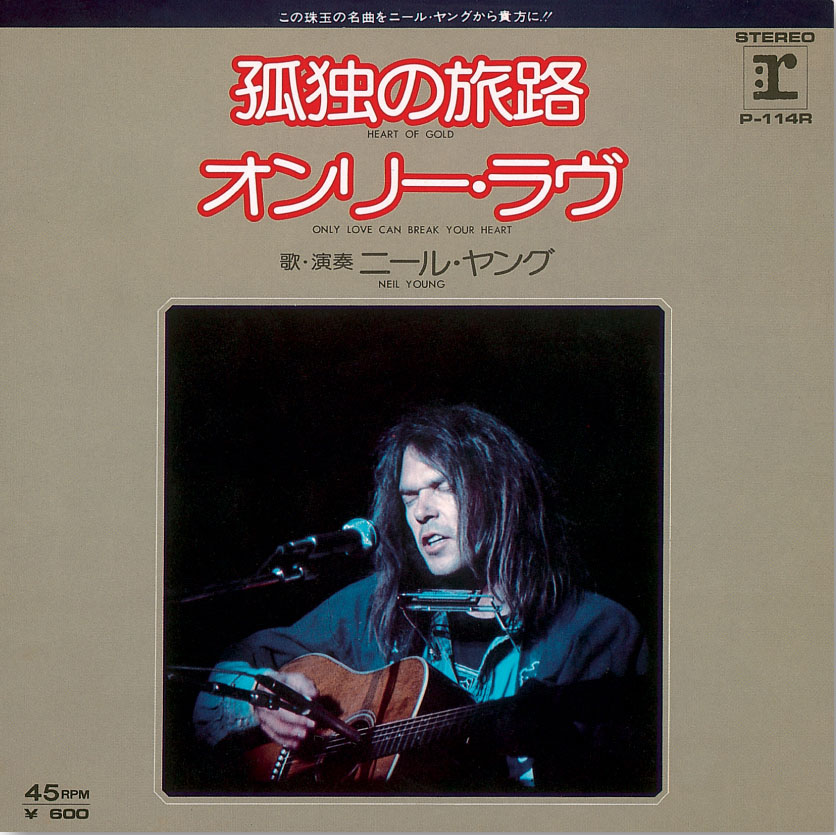

Among the songs they laid down were “Old Man,” which Young had written for Louis Avila, the caretaker on his cattle ranch, and “Heart of Gold,” which featured guest appearances by fellow Cash show guests James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt. In typical fashion, Young handed Taylor a banjo to play, the first time Taylor had ever touched one.

Broken Arrow Ranch, Redwood City, California, may 27, 1971 © Henry Diltz/Corbis

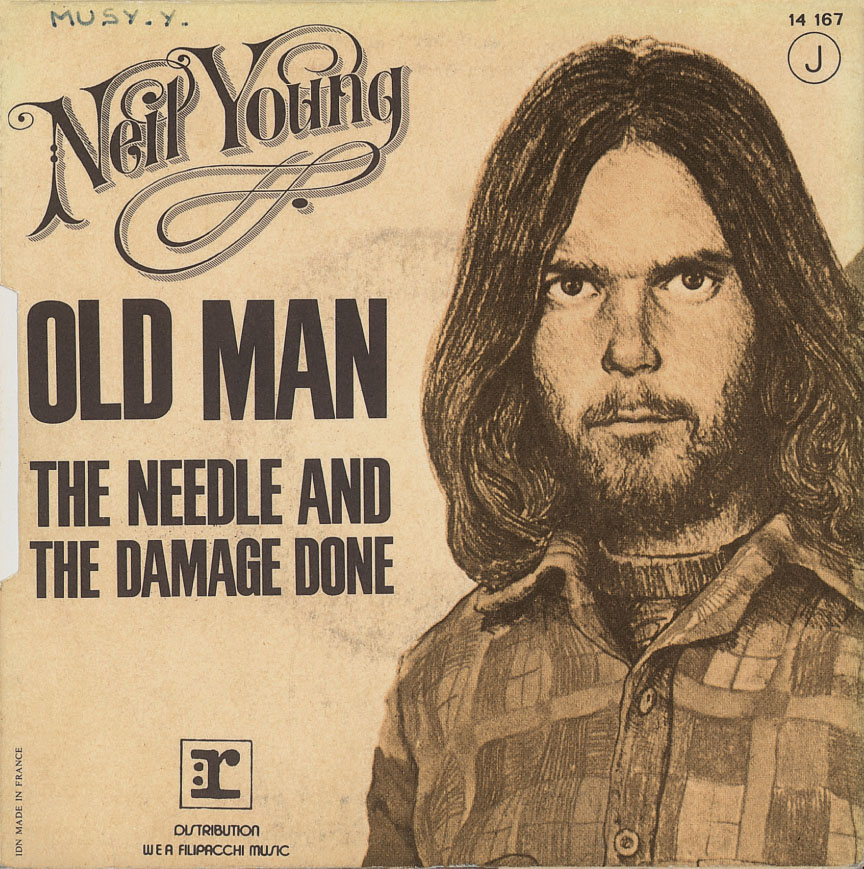

Young’s tour brought him to London, where Jack Nitzsche aided him in recording two songs: the startlingly honest, if chauvinistic, “A Man Needs a Maid” and “There’s a World” with the London Symphony Orchestra, adding a new, bombastic, and self-important aspect to his music. After that he returned to Nashville for more tracking and also built a makeshift studio in his barn at the ranch, where he recorded “Words,” “Alabama,” and “Are You Ready for the Country?” Another key song in the Young canon, “The Needle and the Damage Done,” written for Danny Whitten and other Young associates sidelined by hard drugs, was recorded live at UCLA’s Royce Hall.

Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

When it was released in February 1972, Harvest was an instant sensation, rising to No. 1 even as “Heart of Gold” topped the singles charts. Young described his Harvest experience to American Masters:

I can’t even remember if I enjoyed it. It was very intense. People saw something in me I didn’t see in me. But how many sensitive songs can you write before you’re just writing a sensitive song and it’s not sensitive ’cause it’s not real? And so you can’t live up to expectations.

The producer of Crazy Horse [David Briggs] felt like that was a sellout record. I did this for everybody else ’cause this is what everybody wanted. The fact is, nobody wanted it. I just did it because I was on tour and I toured and I got to Nashville and I met some people and I went into the studio and recorded the songs I’d done. And then I went home and went into the barn and then I went back to London and recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra. And that was Harvest, and I just kept going.

With Nils Lofgren, Tonight’s the Night Tour with the Santa Monica Flyers, London, 1973. © Gijsbert Hanekroot (www.gijsberthanekroot.nl)

Argentina, 1972. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

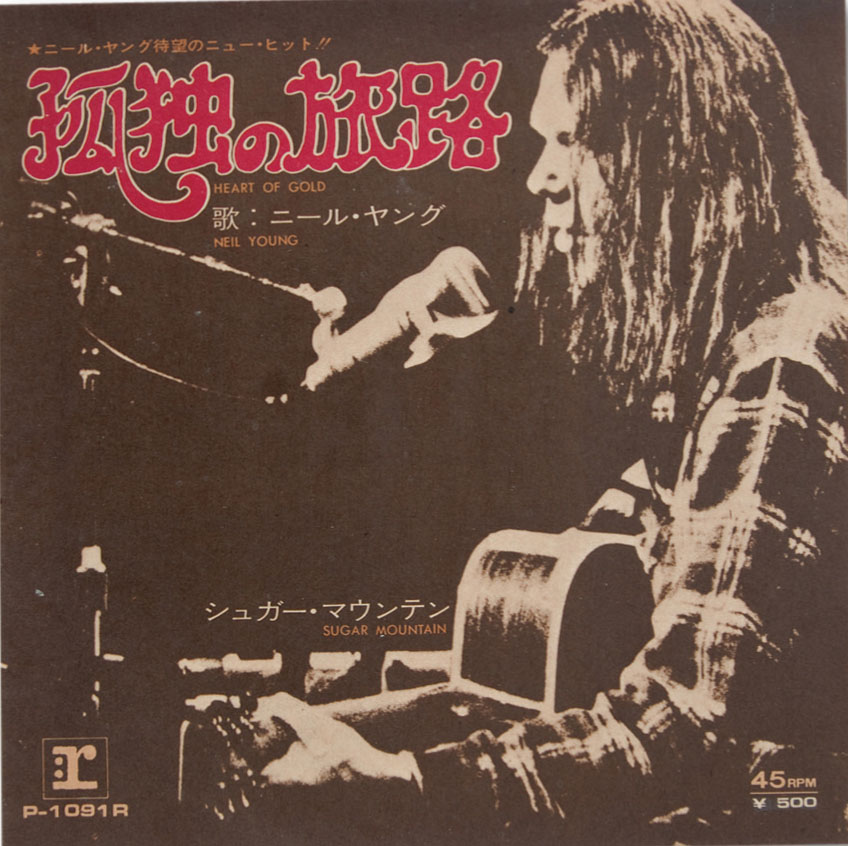

Backed with “Sugar Mountain,” Portugal, 1972.

Courtesy Robert Ferreira

France, 1972.

Japan, 1972. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

EP featuring “Heart of Gold,” “Handbags and Gladrags” by Rod Stewart, “A Horse with No Name” by Americian [ sic].and “Crazy Mama” by J. J. Cale. No country, circa 1972. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

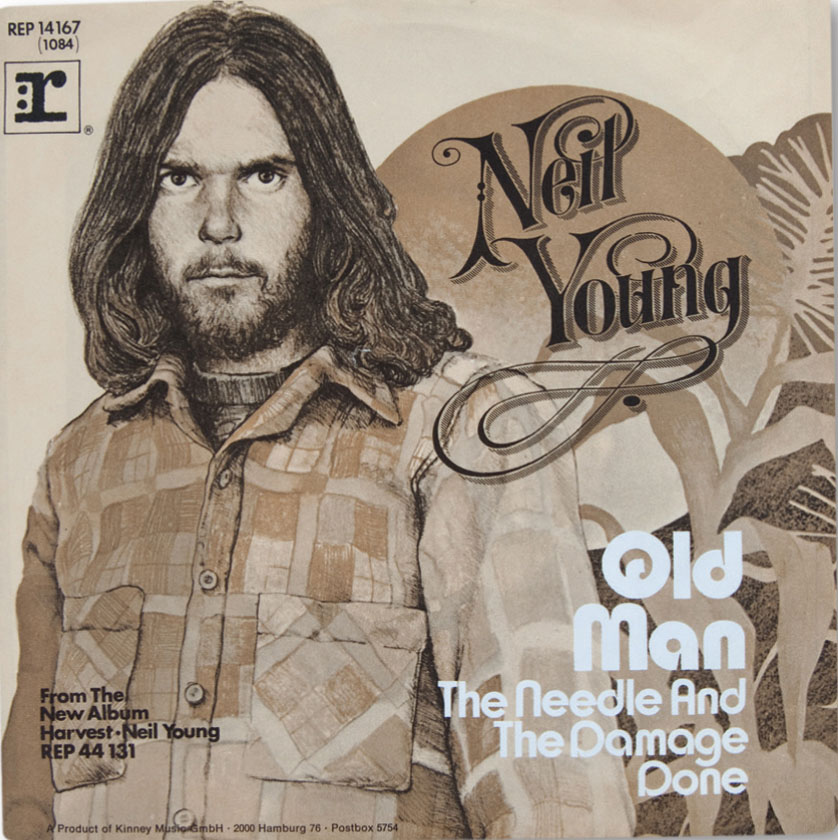

Germany, 1972. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

Neil Young’s been incredibly influential to me. Growing up, Harvest was one of the first albums that I really was affected by, and his work with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, of course, was just right there in my musical development. He’s just a fantastic guitar player and a great songwriter and singer.

—Geoff Tate, Queensrÿche

Germany, 1972. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

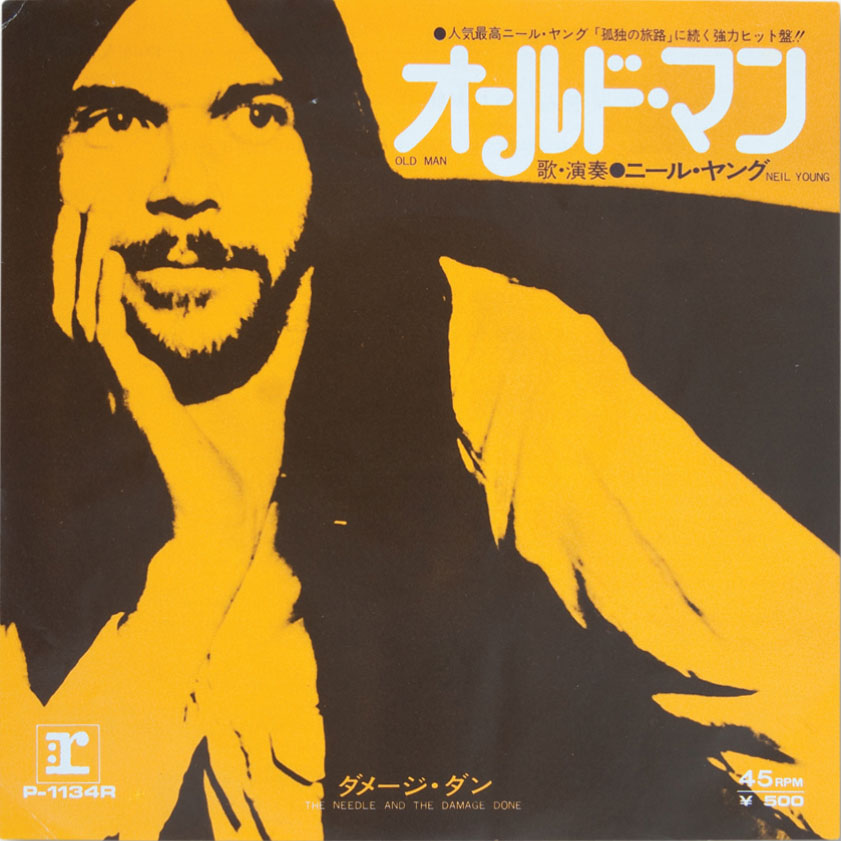

Japan, 1972. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

Japan, 1972. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

Germany, 1972. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

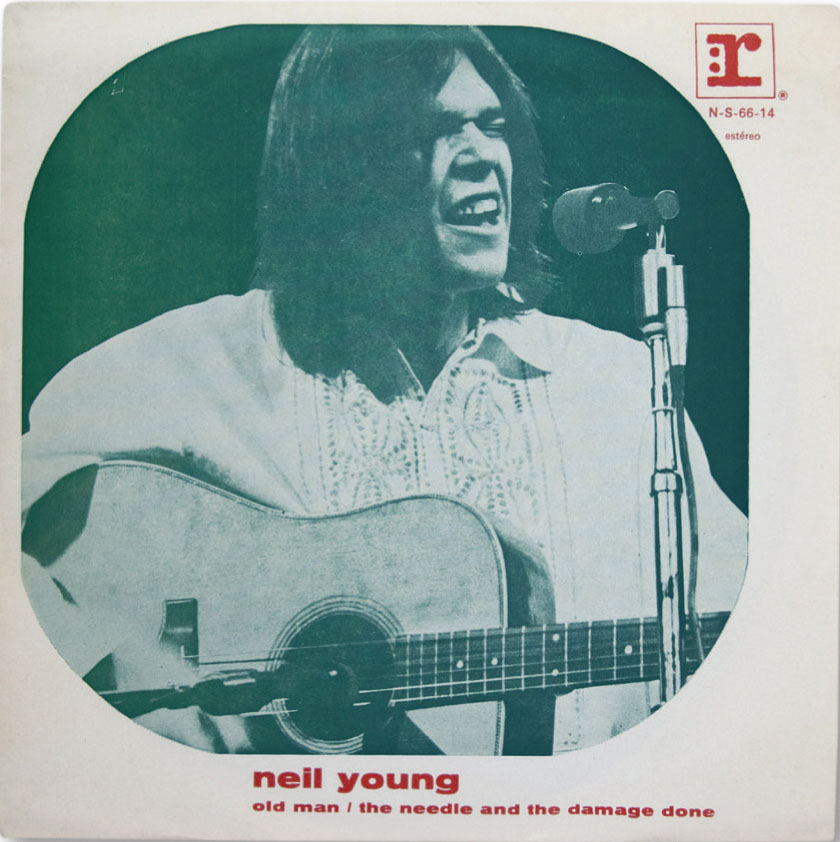

Portugal, 1972. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

Japan, 1976. Courtesy Cyril Kieldsen

In fact, fame made Young pull back further than ever. Experimenting with some film equipment he’d bought, Young began working on a loose set of scenes that would become his first filmic adventure, Journey through the Past. “I wanted to express a visual picture of what I was singing about,” he told Rolling Stone. Young filmed documentary footage of himself on tour as well as scenes concocted with some of his oddball neighbors. The process sucked in his CSN partners as well, and no one associated with the film acquitted themselves particularly well.

“It’s hard to say what the movie means,” Young told Rolling Stone. “I think it’s a good film for a first film. I think it’s a really good film. . . . It does lay a lot of shit on people though. It wasn’t made for entertainment. I’ll admit, I made it for myself. Whatever it is, that’s the way I felt. I made it for me. I never even had a script.”

As ever with regard to Neil Young, art imitates life.

Film still, Journey through the Past, 1972. Everett Collection/Rex USA