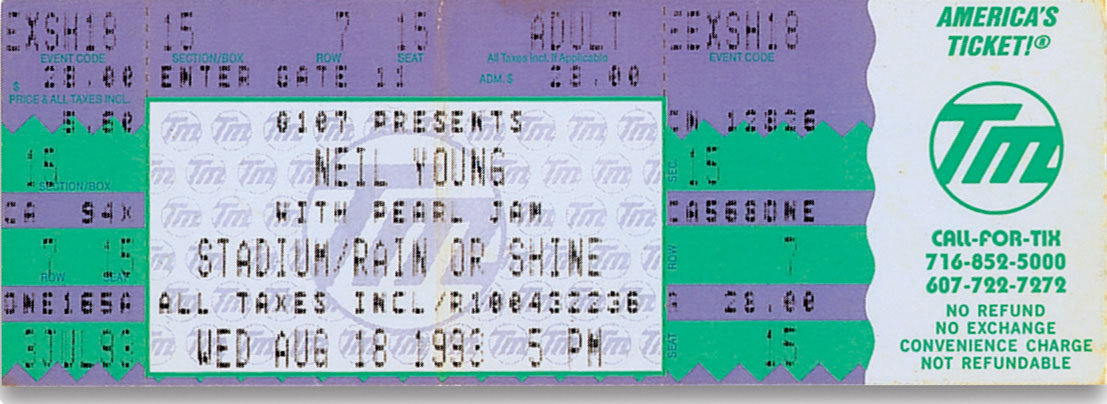

In 1997, Buffalo Springfield was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but Young was a no-show. He protested the ceremony’s shift from a Friar’s Club–style insider’s party to a VH1 broadcast. “So, Rich,” Stephen Stills quipped to bandmate Richie Furay at the podium, “he quit again.”

Young, it turned out, was intent on celebrating the Springfield in another fashion. For years he had been working on his magnum opus, a multi-disc box set that was originally titled Decade II but eventually came to be known as Archives. In an act of ego that would qualify as a delusion of grandeur had he not gone on to do such great work, Young had saved all his recordings so one day he’d be able to piece together his own musical history rather than rely on someone else to do it. Of course, that history included Buffalo Springfield, so he sifted through the band’s material with an eye toward compiling a box set separate from his own. He invited Stills to his ranch to hear what he’d done. The two “laughed, cried, and hugged each other,” Young recalled.

At some point, Stills brought out a guitar and played a song he’d just written. Young liked it so much that he volunteered to play guitar on it, and a full CSNY reunion blossomed from there. Young recalled:

I came into the studio and discovered that they were in here working on a record by themselves, and they weren’t using a record company. They had to finance it themselves, so obviously they were really into it. That’s the only real good reason to play music. So it was just a good feeling again; it was three guys who have been making music together for thirty years, and they still want to do it enough to take out bank loans or whatever. That’s why someone would want to be involved in that energy. It was all positive, and the music was really great.

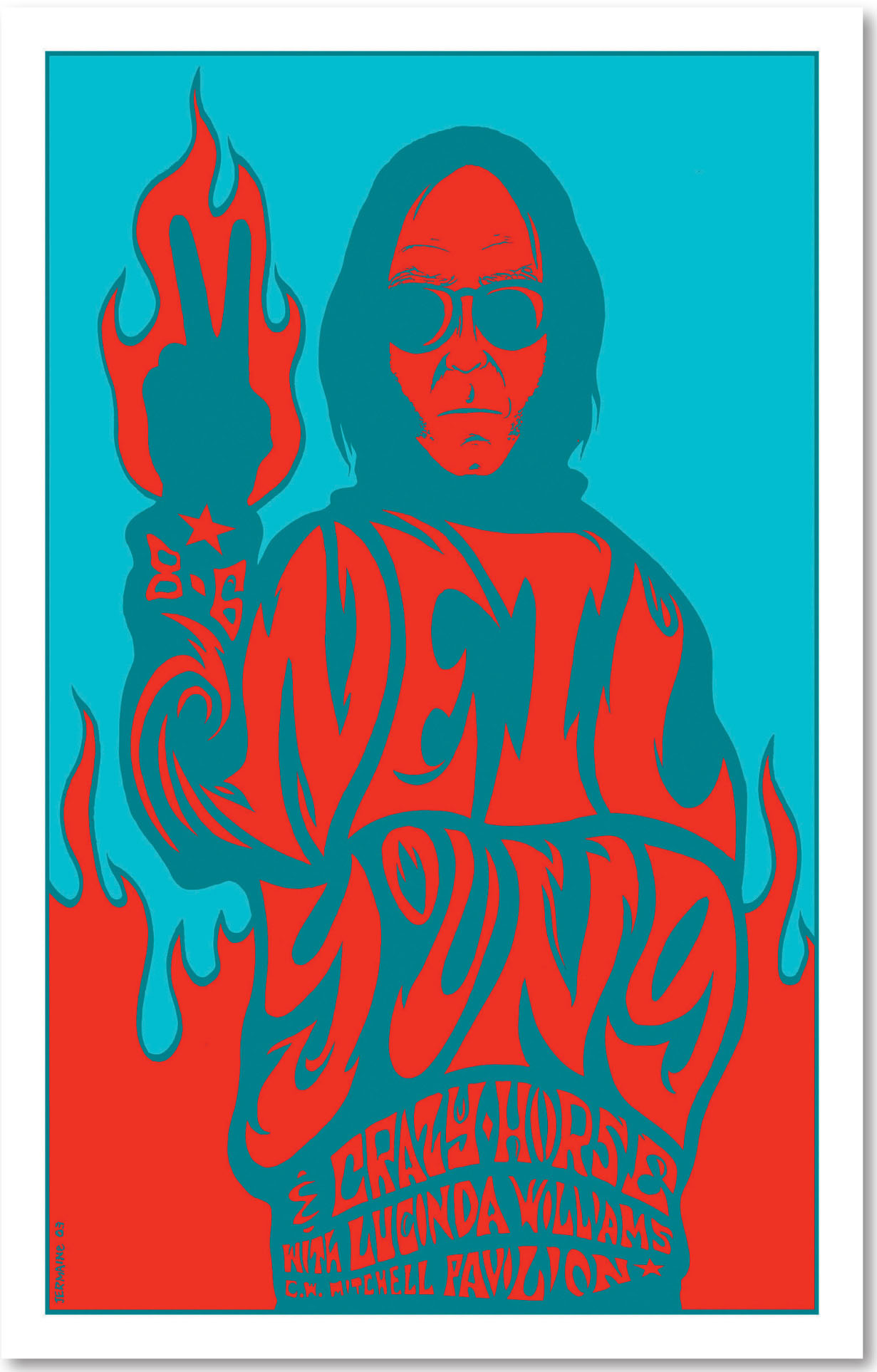

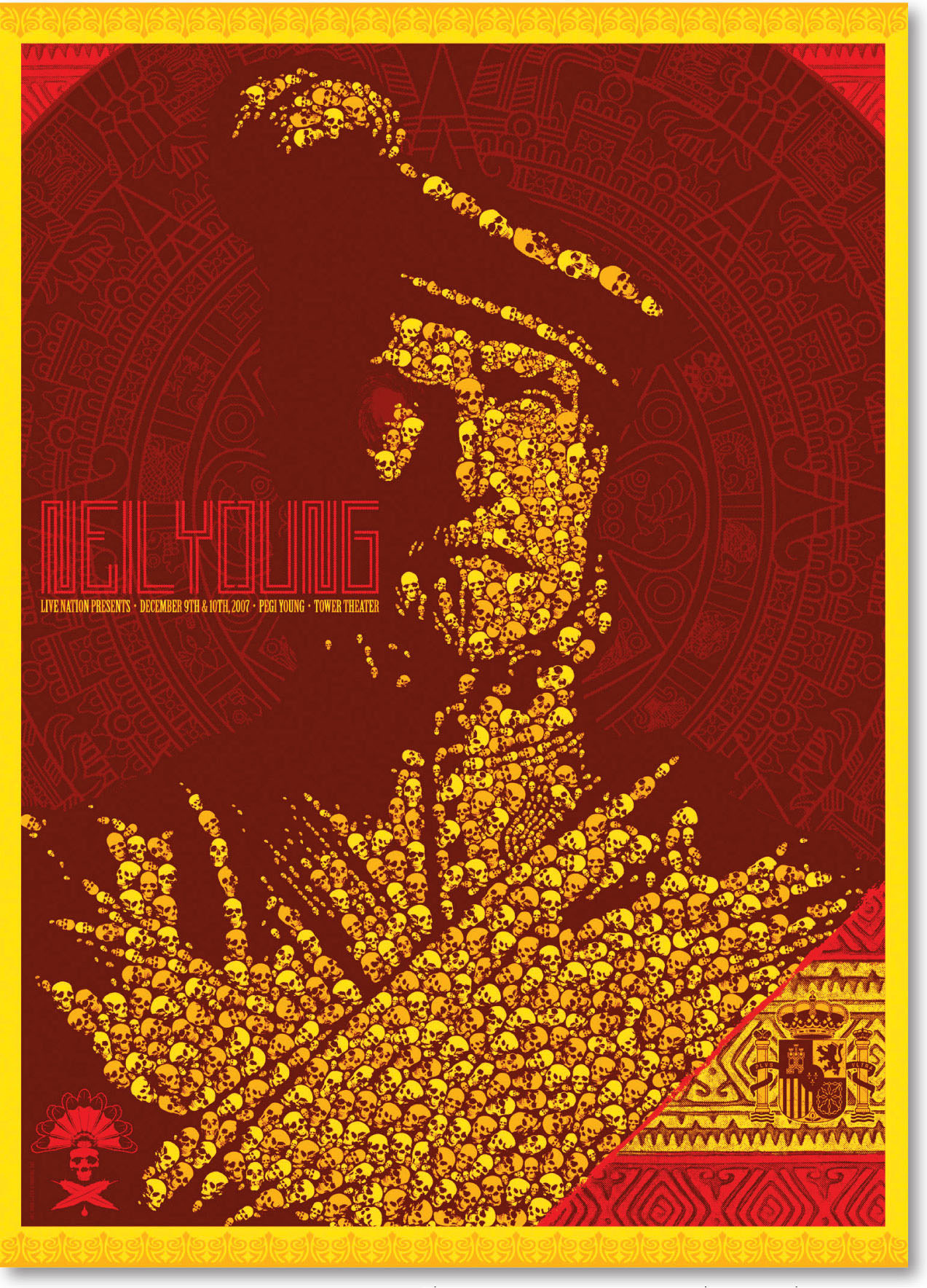

Artist: Jermaine Rogers (www.jermainerogers.com)

Bridge School Benefit, Shoreline Ampitheatre, Mountain View, California, October 31, 1999. Photo by Tim Mosenfelder/ImageDirect/Getty Images

Young had been working on an acoustic album called Silver & Gold, but he told his partners they could mine any of the songs they liked for the CSNY album. They picked four: “Slowpoke,” “Out of Control,” “Queen of Them All,” and the eventual title track, “Looking Forward.” Stills took three writing credits on the album, and Crosby and Nash took two apiece.

Past CSNY endeavors had ended in acrimony, tears, fistfights, and name-calling. This time things were different because, as Crosby noted, “There’s no chemical baggage.” Crosby had cleaned up in prison and was the recipient in 1994 of a liver transplant. He also had a reputation to uphold as a celebrity sperm donor (to Melissa Etheridge and Julie Cypher); the term “sperm whale” was tossed around during the sessions and subsequent tour rehearsals. Even Stills had beaten his primary demon, cocaine. But despite all the love in the room, Looking Forward was largely a critical and commercial disappointment. Still, the quartet could point to a sold-out arena tour—its first tour of any kind since 1974—as evidence of its continued appeal. Kicking off as it did just after the turn of the millennium, the tour was dubbed CSNY2K.

CSNY2K Tour, Staples Center, Los Angeles, February 12, 2000. AP Photo/E. J. Flynn

He’s only one of the great, historically correct artists of all time. Him and Tom Petty and Bob Dylan and Emmylou Harris, these kinds of artists are the foundation of our culture. These people have created the grid that we all can follow, and that’s what’s beautiful, because he never followed the herd. He’s completely original.

—Nancy Wilson, Heart

Promo cigar box, Silver & Gold, 2000. Courtesy Robert Ferreira

Young, having given what he called “the cream of the crop” of his songs to CSNY, still managed to salvage Silver & Gold, pulling together songs from a variety of sources. “Some of them are pretty old, some of them are brand new,” he said. “They’re written in the same state of mind, I think, over the years.”

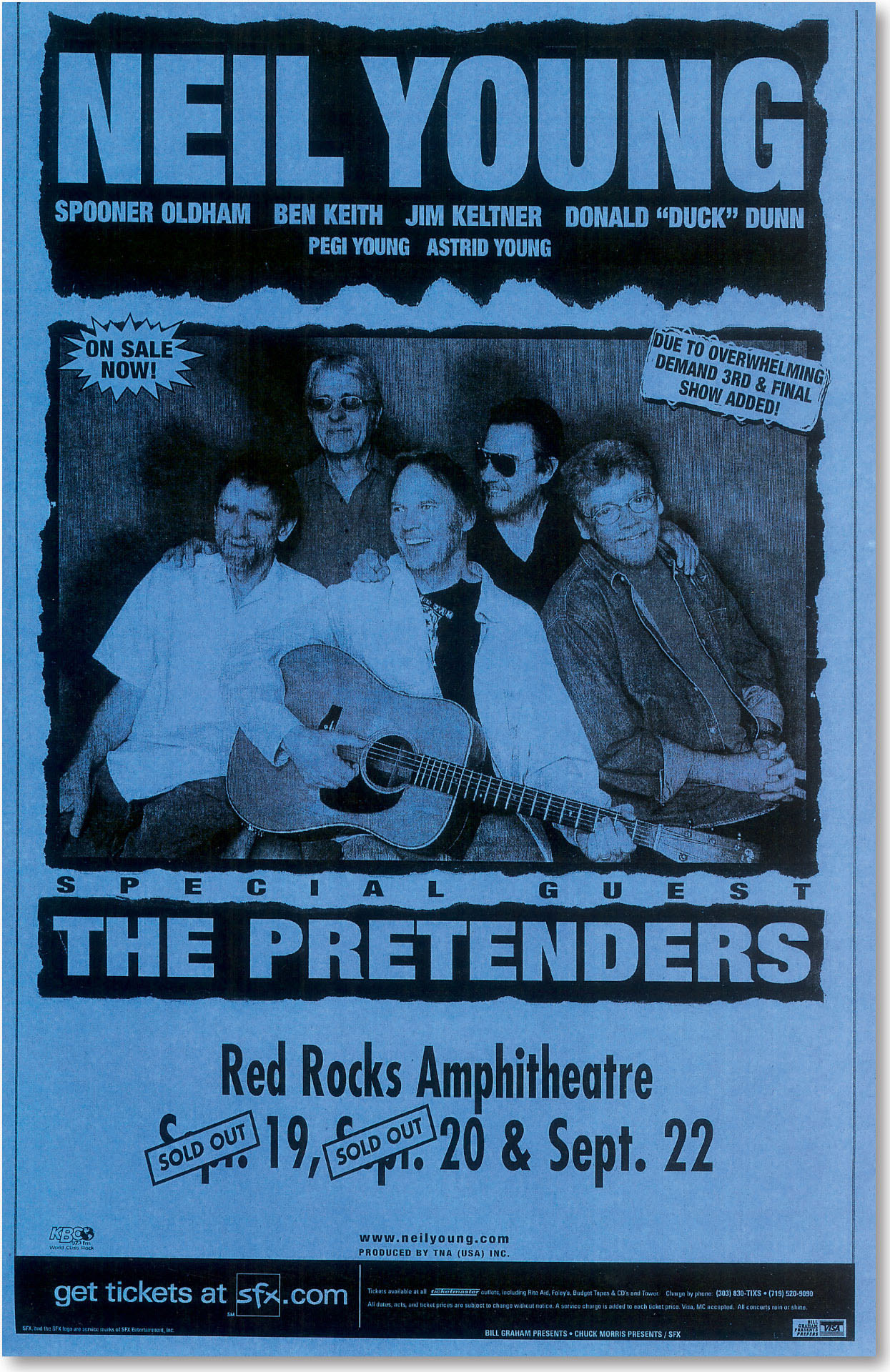

It’s still an acoustic album as originally envisioned but with the addition of some sidemen, including Ben Keith, Spooner Oldham, drummer Jim Keltner, bassist Duck Dunn, and vocalists Emmylou Harris and Linda Ronstadt. The picture that emerges from songs such as the title track, “Daddy Went Walkin’,” and “Razor Love” is one of family values, middle age, and contented domesticity. “Love and a razor may not be an easy analogy to draw,” Young said of the latter song, “but they’re really quite similar because your love is inside something, and a razor or a blade, it cuts right to the point. But there’s no hate in there. It’s not about violence. It’s about cutting to the quick, about getting through all the things that get in the way of love.”

The song “Buffalo Springfield Again,” meanwhile, heads in another direction, giving a shout-out to his old band and offering hope for a reunion. “Maybe now we can show the world what we got,” Young sings. The reunion never happened (except, according to Young, in private), but the box set—named, perhaps a tad too matter-of-factly, Box Set—did.

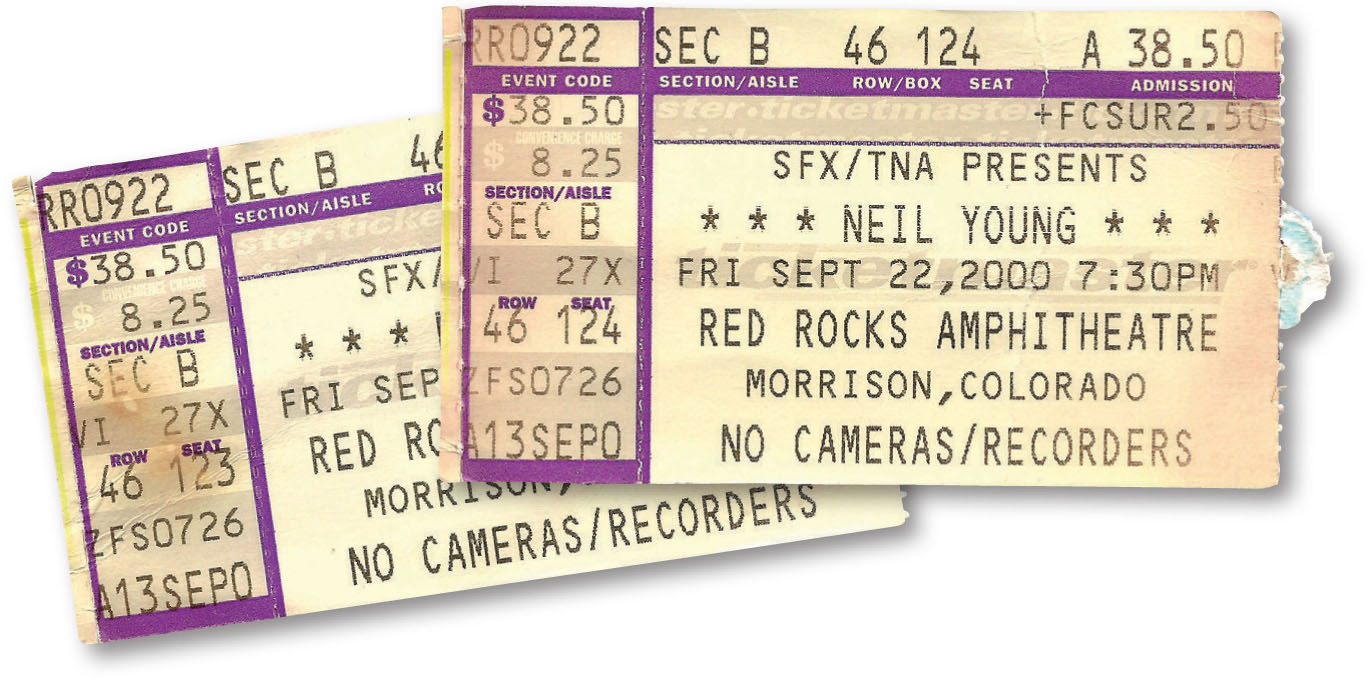

Young kept the Silver & Gold band together, substituting wife Pegi and half-sister Astrid for Harris and Ronstadt, and hit the road. The series of shows resulted in a live album, his third and least impressive such effort of the decade. Road Rock V1: Friends and Relatives features just one new song—“Fool for Your Love,” a remnant from the Bluenotes era—plus a cover of Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” with a guest appearance by the Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde.

Music in Head Tour, 2000.

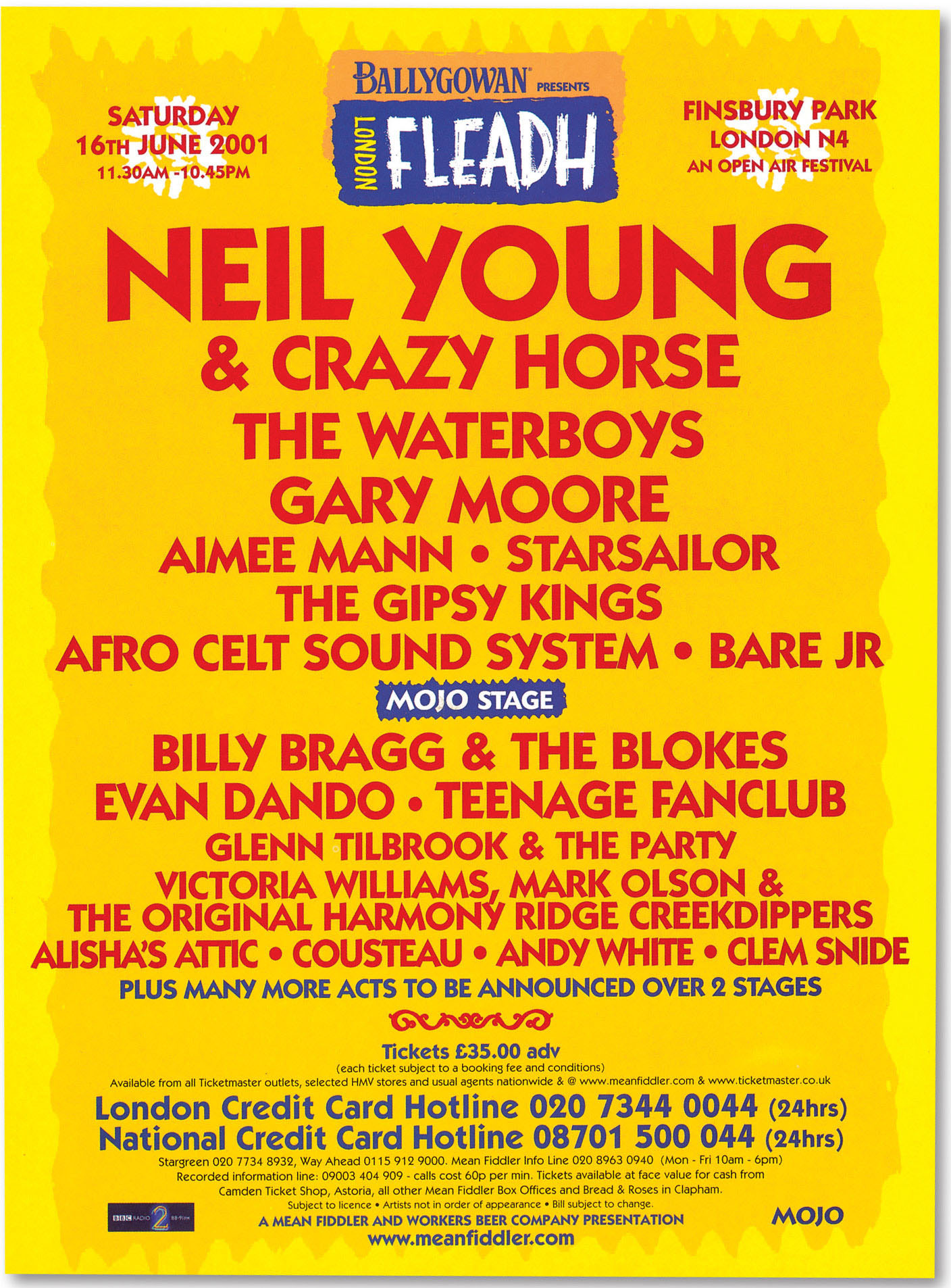

Fleadh Festival, Finsbury Park, London, June 16, 2001. © Richard Skidmore/Retna

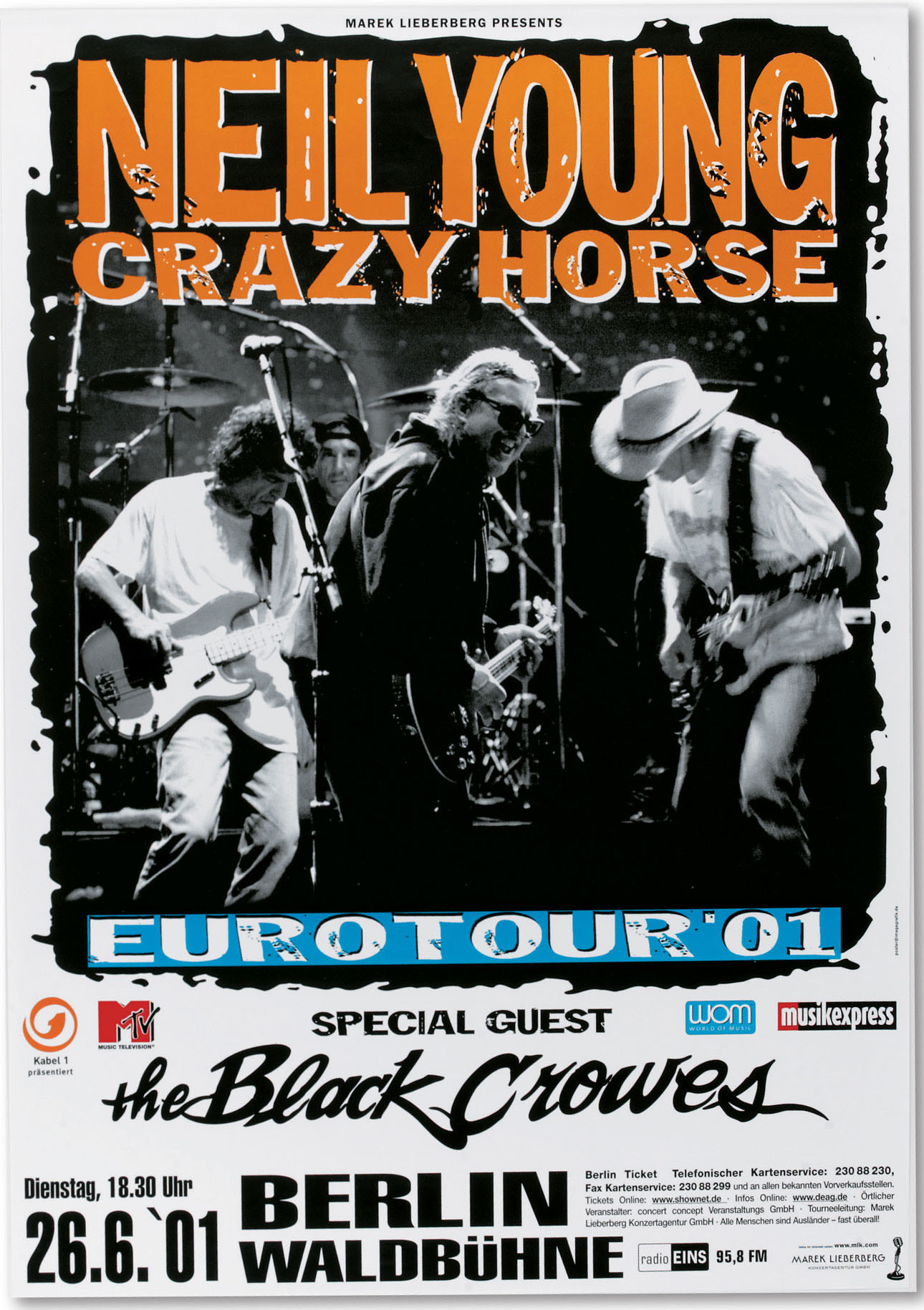

Crazy Horse Eurotour, Berlin, Germany, 2001.

I love the guy, and sometimes he makes my head turn a little bit because I feel like he releases everything, and I love that about him. “Here’s the next album I’m putting out right now,” and he releases his Archives of everything. He really wants you to be part of his entire journey, his entire process, without caring about the criticism or anything that could come with it. I find myself in a position where people are always saying, “Don’t put that out right now. You gotta wait,” or “You don’t want to put that out right now ’cause people might think this or that.” And when I look at Neil Young and the career retrospective that he offers, he’s doing all kinds of crazy stuff, constantly, and he never stopped. He just kept releasing, kept releasing, kept releasing, and to me that’s what we should be doing. And he really is a rocker; I saw him at Glastonbury, and that guy’s still playing like he was in “Cortez the Killer,” just really shredding and doing lengthy jams and taking people on journeys. I have nothing but the utmost respect for the guy. I kinda want to understand his secret to longevity.

—Jason Mraz

The album’s real flaw, though, is that the band, built for the subtle acoustic stylings of Silver & Gold, is ill-suited for the long guitar freakouts of “Cowgirl in the Sand” (clocking in at eighteen minutes), “Words” (eleven minutes), and “Tonight’s the Night” (ten and a half minutes).

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Young lent his voice to the chorus of support given to victims’ families by artists including Bruce Springsteen, U2, Billy Joel, Dave Matthews, and Alicia Keys. He sang a plaintive rendition of John Lennon’s “Imagine,” a performance that can be found on America: A Tribute to Heroes.

Conjuring the spirit and immediacy of “Ohio” three decades prior, Young also wrote “Let’s Roll,” which he released just weeks after the attacks. The song takes its title from words spoken by United Airlines Flight 93 passenger Todd Beamer, one of the doomed travelers believed to have overpowered the hijackers before the plane crashed in a Pennsylvania field. “You got to turn on evil when it’s coming after you,” Young sings grimly. “It struck me as heroic in a legendary way,” he said. “These guys weren’t doing this to be martyrs or because they thought they would get a payback.” He figured, though, that someone else would tell the story in a song before he would:

I said to myself, “There’s gonna be ten people that come out with songs called ‘Let’s Roll’ next week—there’ll be two country ‘Let’s Rolls’ and a rock and roll ‘Let’s roll’ and an R&B ‘Let’s Roll.’ They’ll be everywhere.” So I sat back and waited for six weeks or so, and nothing happened. And then [President George W.] Bush goes on TV and says, “Let’s roll,” and for me that was the last straw. I said, “I just gotta do this. I don’t care if it’s the most obvious thing that ever happened.”

He performed the song with CSNY when the band went on tour again in 2002. Young thought the quartet’s presence in the wake of 9/11 would offer fans “some kind of feeling of comfort . . . seeing that we’re still here, and everybody’s still here, and we’re still doing what we do.”

I just gotta do this. I don’t care if it’s the most obvious thing that ever happened.

“Let’s Roll” eventually found its way onto Young’s album Are You Passionate? Except for one Crazy Horse track, the album was recorded with Booker T. and the MGs, who Young had first played with at Bobfest. As for favoring the seasoned Stax band over his traditional backing unit, Young said, “It’s just that the groove and the feeling and the vibe of the music was more uplifting.” True, the album opened him up to criticism of returning to his old days of genre exercises, positing himself this time as a Southern soul man. But the combination of Young and the MGs turned out to be no more audacious than his signing to Motown Records as a member of the Mynah Birds in the ’60s. Though it’s surfaced in many different ways over the years, Neil Young has always had soul.

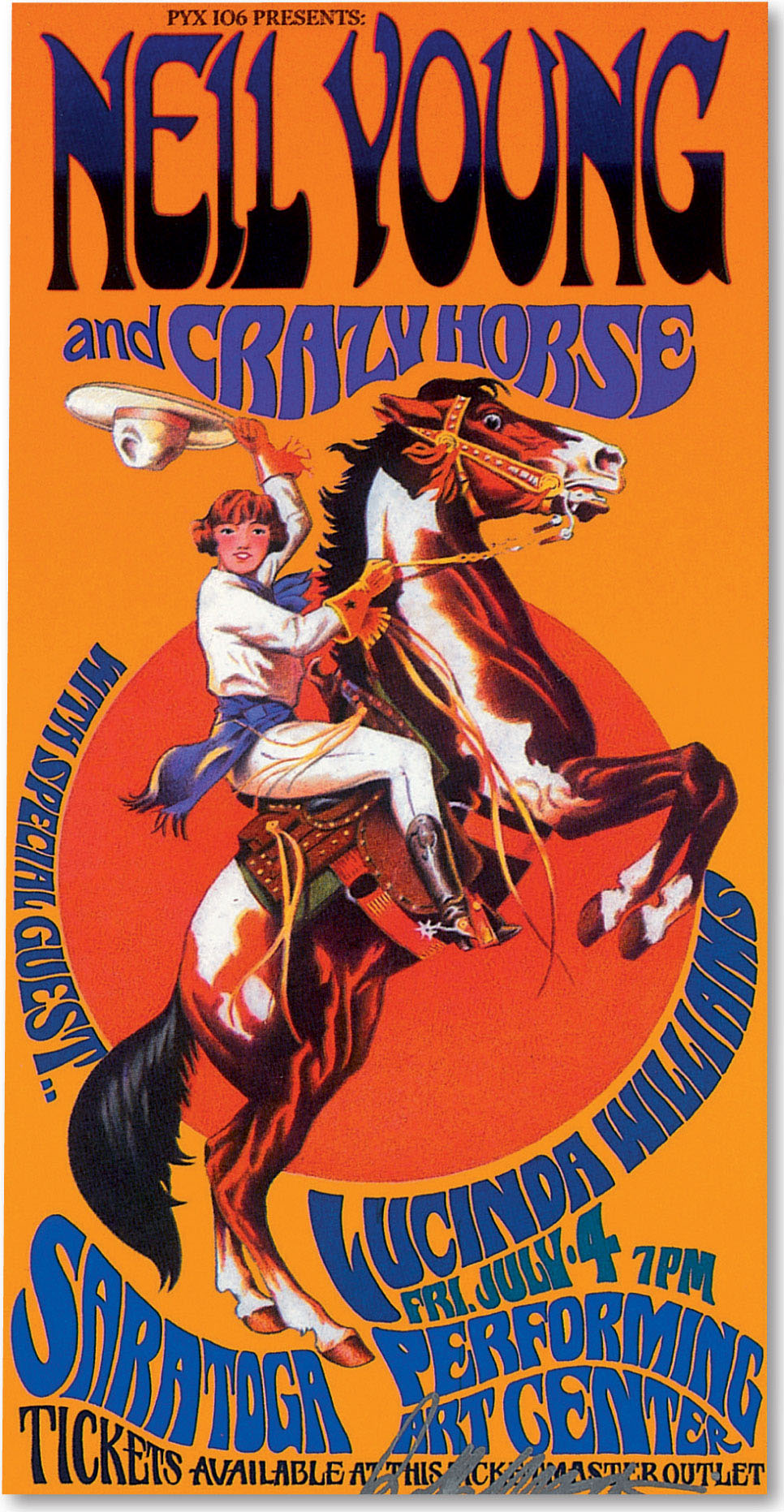

Greendale Tour, Saratoga Springs, New York, 2003. Artist: Bob Masse (bmasse.com)

Bonnaroo, Manchester, Tennessee, 2003. Artist: Pasty Poster Co.

His next project would take on a variety of dimensions. Greendale was a concept album–cum–rock opera that Young fleshed out more fully than almost anything he’d ever done. Beyond the album, there was a companion film—another low-budget flick in the spirit of Journey through the Past and Human Highway—plus a book and website. All of it was designed to tell the story of the Greens, a fictional small-town American family struggling with issues of corruption, violence, environmental destruction, and media overload. It’s a postmillennial rock ’n’ roll version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Young is backed by the Crazy Horse rhythm section of Molina and Talbot (with Sampedro hopping back on board for the tour).

When Young took the album on the road, his high-concept/low-budget show featured cardboard sets of the fictional town and a company of actors who lip-synched his lyrics while he and Crazy Horse played live onstage. Young told Rolling Stone:

These characters are all part of me, part of my family and my life—and part of the greater family, the American family. The beautiful thing about the Greendale show is that I’m standing there for an hour and a half, singing these new songs, and people are not looking at me. They’re looking all over. And in the film, I play the music. I sing everything. I see images I want to see, because I filmed a lot of them myself. But I’m not lip syncing, I’m not faking. I really hate that shit.

He was prepared for—and received—a drubbing from critics and fans alike, though, noting, “I’ve heard people saying, ‘This is worse than Trans.’”

Neil’s kind of an enigma to me. I’m very aware of Neil and what he does, old and new. I can’t figure the guy out—and I don’t really need to. Neil’s just awesome. He keeps doing his thing. I saw him when I was on tour with Bob [Dylan] and we were in Italy. We were playing a piazza and had a day off in this town, and Neil and Crazy Horse were playing and it was just unbelievable, particularly his solo part of the show. Neil is just part of that awesome handful of people, him or Joni or Bob or Neil Diamond or whoever; they do their thing, and they’re obviously lifers.

—Charlie Sexton, Arc Angels

Greendale was a surreal experience but nothing like what real life handed Young next. During the sessions for his album Prairie Wind, Young was shaving one morning and noticed an object, somewhat like a piece of broken glass, in his field of vision. No matter what he did, it wouldn’t go away. “So I went to my doctor,” Young told Time magazine, “had an MRI and the next morning I went to the neurologist, Dr. Sun—a Chinese guy, very funny guy. He says, ‘The good news is, you’re here, you’re looking good. The bad news is, you’ve got an aneurysm in your brain. You’ve had it for a hundred years, so it’s nothing to worry about—but it’s very serious, so we’ll have to get rid of it right away.’”

Young handled the situation with superhuman cool. Drummer Chad Cromwell said in the film Heart of Gold:

He said, “I got this brain aneurysm.” And I mean, the world stopped. It was just like, “You what?” He said, “Yeah, I got this brain aneurysm. I’m going to go to New York next Tuesday and they’re gonna do this thing.” He goes, “And it’s really wild what they’re gonna do. . . . They’re gonna go in there and they’re gonna put these little bitty springs in there. And they’re biodegradable and what that does, that makes the body produce this scar tissue which then negates the aneurysm.” I’m sitting there going, “Why are you sitting here? How is that? How can it be that you’re going there next Tuesday and we’re sitting here recording?”

He says, ‘The good news is, you’re here, you’re looking good. The bad news is, you’ve got an aneurysm in your brain. You’ve had it for a hundred years, so it’s nothing to worry about—but it’s very serious, so we’ll have to get rid of it right away.

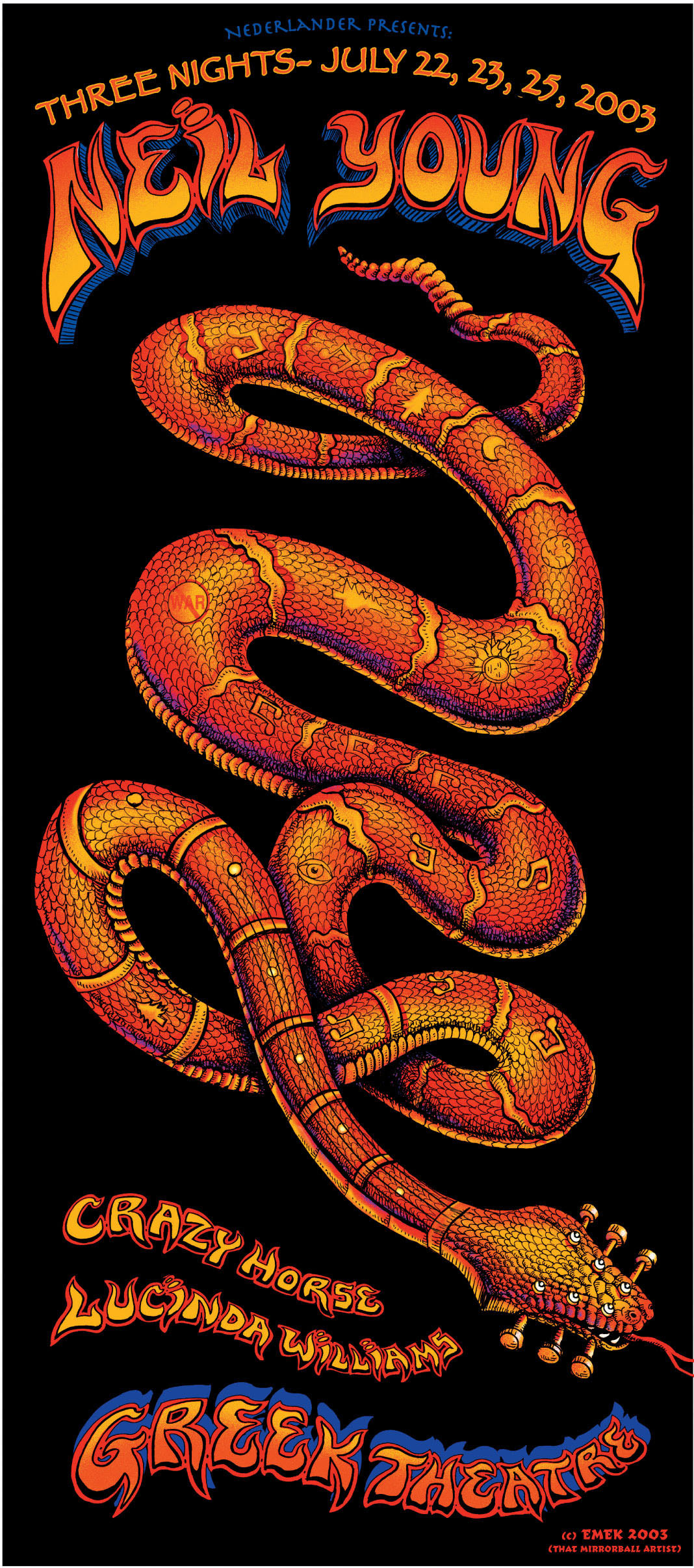

Greendale Tour, Los Angeles, 2003. Artist: Emek (www.emek.net)

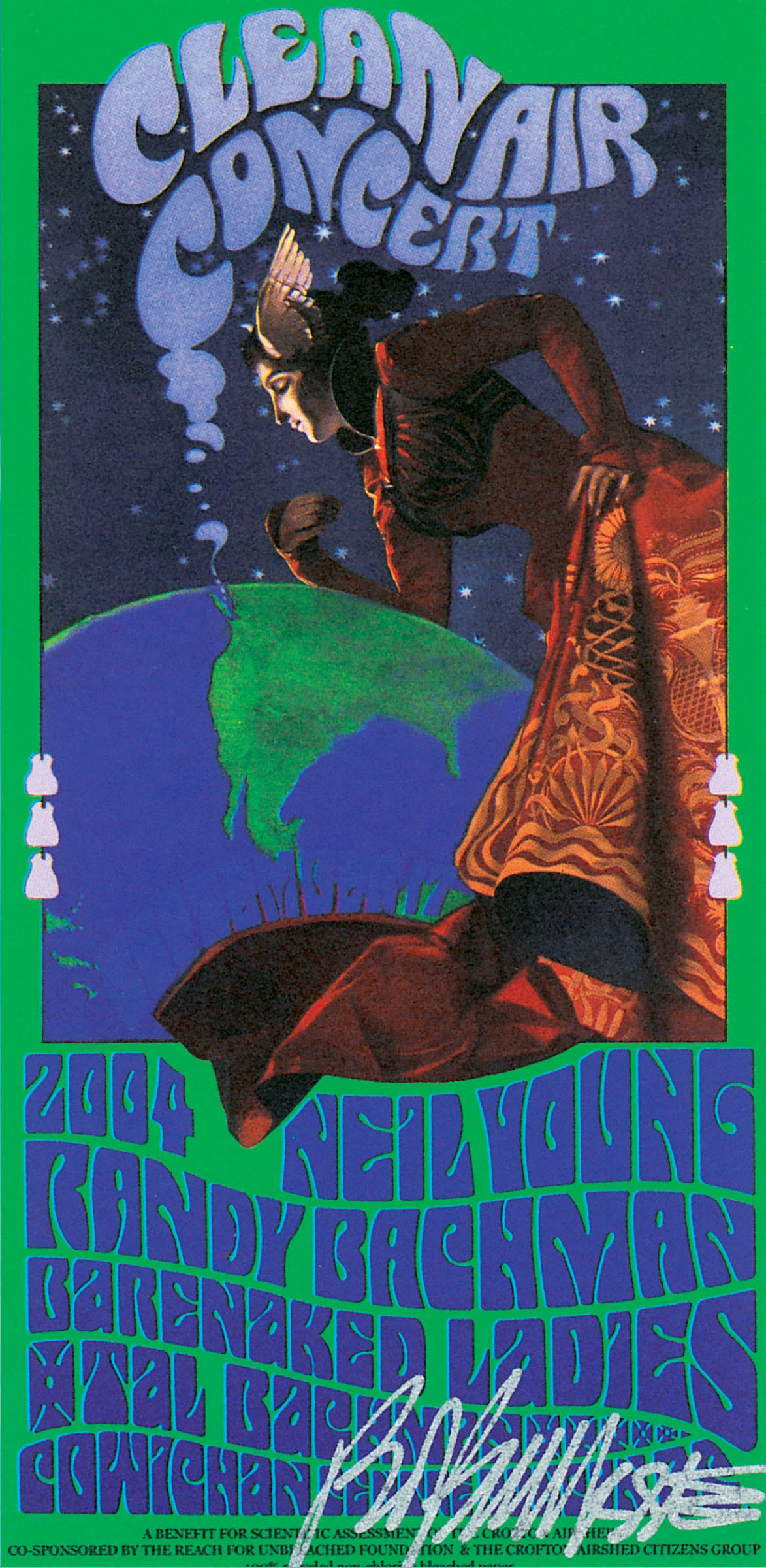

Duncan, British Columbia, September 17, 2004. Artist: Bob Masse (bmasse.com)

The operation was a success, the surgeons having accessed Young’s brain through his femoral artery. But a couple of days later, the artery burst, and he was rushed back to the hospital. He canceled a scheduled appearance at the Juno awards, forcing him to explain publicly what had happened—which he wouldn’t have done otherwise. “I came very close to no one ever knowing,” Young said. “I would have had an aneurysm, got rid of it, and no one would know the difference. It would have been so cool.”

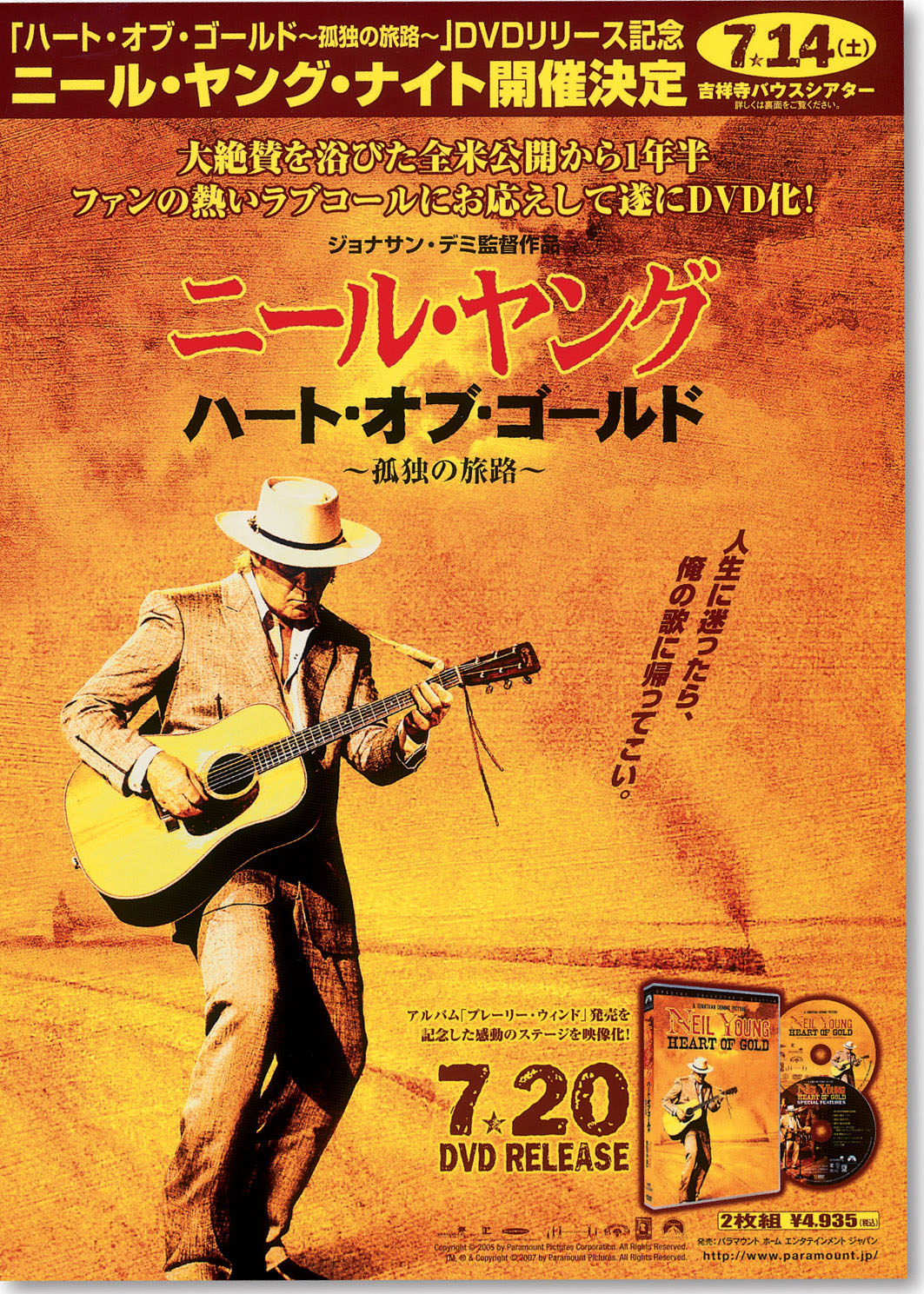

Cut in Nashville, Prairie Wind—as well as Heart of Gold, the sumptuous Jonathan Demme concert film that accompanied it—bears the marks of Young’s near-death experience. Both are deeply nostalgic and even a little sad as he says goodbye to some of his fellow travelers, including his father, who suffered from dementia before his death. “I had a great relationship with my dad, and I felt like everything was O.K. when he died, that I was at peace with him and everything was cool,” Young told Time. “Then I went to the service and completely broke down out of nowhere.”

On the Heart of Gold set with director Jonathan Demme, Ryman Auditorium, Nashville, Tennessee, August 18–19, 2005. © Paramount/Everett Collection/Rex USA

Prairie Wind’s closing song, “When God Made Me,” is a hymn questioning the creator’s motives—not in an angry fashion but a prayerful one. Young told PBS’s Charlie Rose the most significant way that his aneurysm had changed him:

It gave me more faith. . . . I know there are a lot of stories. There is the Bible. There is the Koran. There are all of these things. Everybody’s got one. Everybody has a faith. And there are stories that have gone through the ages, and I respect all of them. But I don’t know where I fit in. I just have faith.

God didn’t disappoint Young, but men still did. As the war in Iraq continued to rage, Young suddenly found that he’d had enough. He told Rolling Stone:

I went down to the coffee machine and there was USA Today. The cover showed a large military craft converted into a flying hospital. The caption said something about how we are making great strides in medicine as a result of the Iraq conflict. That just caught me off guard, and I went upstairs and wrote “Families” for one of those soldiers who didn’t get to come home. Then I cried in my wife’s arms. That was the turning point for me.

And there was no turning back. The songs for Living with War, which he called his “metal folk protest album,” poured out of Young, culminating in “Let’s Impeach the President,” a no-holds-barred attack on George W. Bush.

“You know, it is a sad thing,” Young acknowledged to Rose. “It is terrible to be involved in . . . criticizing the president and doing this and that, and talking about things in the first person and getting right in there.”

Young created an elaborate section on his website, neilyoung.com, called Living with War Today, a mock news site with stories about the war and its aftermath for soldiers and their families. There are also links to hundreds of protest songs and videos posted by musicians from all over the world. Young also took the album on the road, turning it into a CSNY tour dominated by the album. “We tried sprinkling my songs throughout the show and that didn’t work,” Young told Rolling Stone, “because they disturbed everything. We put them all together, basically, and isolated the other ones.”

With David Crosby, CSNY Freedom of Speech Tour, Red Rocks Ampitheatre, Denver, Colorado, July 17, 2006. © Scott D. Smith/Retna Ltd.

I think it was Peter Buck from R.E.M. and Neil Young, and they were doing an interview, and they were talking about music and talking about their love of vinyl and the analog sound compared to the digital sound and what a shame it was the industry kind of pushed it aside.

—Eddie Vedder, Neil Young’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction speech

The tour, captured by Young (under his nom de film, Bernard Shakey) in the documentary CSNY/Déjà Vu, reveals just how contentious the shows became.

Some audience members booed Young’s polemics or even walked out, while others sang along or cried while the band sang “Find the Cost of Freedom,” an anthem for another war made relevant once again. “It’s the real deal,” Young said. “I make a whole album about this war, and some people are still stupid enough to say that I just did it for the money because I’m an old fart. They’re out of touch. It’s not about the entertainment business, it’s about a fucking war that people are getting killed in.”

Having said his piece, Young slowly began rolling out samples of his massive Archives project. The first piece of the puzzle, Live at the Fillmore East: March 6 & 7, 1970, surfaced in 2006. It captures a raging concert performance by Crazy Horse, including the version of “Come On Baby Let’s Go Downtown,” with vocals by Danny Whitten, that had been culled for Tonight’s the Night. Live at Massey Hall 1971 arrived in 2007, offering an especially compelling solo show. Another solo concert, Live at Canterbury House 1968, was released in 2008. It contains the version of “Sugar Mountain” that was a long-ago B-side for Young and had made its album debut on Decade.

With Pegi, Fifth Annual Benefit for the Elton John AIDS Foundation, Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York, October 3, 2006. Photo by Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images

Chrome Dreams Tour, Northrup Auditorium, Minneapolis, Minnesota, November 8, 2007. © Tony Nelson (tonynelsonphoto.com)

Young continued recording new material even as he mined his past. Chrome Dreams II, in typical Youngian fashion, is a sequel to an album that was never released (the legendary Chrome Dreams that was raided for songs that eventually wound up on American Stars ’n Bars). Some of the Chrome II songs date back to the 1980s, notably the extended jam “Ordinary People,” which features the Bluenotes. Other tracks range from the gentle Harvest-style folk rock of “Beautiful Bluebird” to the meditative “The Way” to the slapdash garage rock of “Dirty Old Man.” Its specific connection to the original Chrome Dreams is unclear.

Hastily written and recorded, Young’s 2009 album Fork in the Road seems less like a cohesive album and more like a series of blog entries—which, in a way, it was. Inspired by his efforts to turn a vintage Lincoln Continental into a vehicle running entirely on alternative energy, Young had been posting his thoughts on the automobile industry—as well as some songs—on the news and opinion website Huffington Post. Songs like “Johnny Magic” (about his Linc/Volt partner Jonathan Goodwin), “Fuel Line,” and “Get Behind the Wheel” continue along the same themes. It’s not one of his most musically inventive albums—perhaps the innovation went into the car instead—but it’s one of his most immediate.

Soon after Fork, Young unloaded the massive Archives Vol. 1 box set, the first of four or five projected anthologies. He’d been working on the set so long, Wired magazine tittered “that the big news in the tech world when it was first announced was Windows 3.0.”

European Summer Tour, Firenze, Italy, 2008. Artist: Steuso (www.steuso.com)

Chrome Dreams Tour, Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, 2007. Artist: Todd Slater (www.ToddSlater.net)

New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, 2009. Artist: Jay Michael (FlyRightStudio.com)

He’s a brilliant artist, I think. I’m a big admirer of his singing and his music. He’s always made really good records. He’s always been a stickler for great recorded sounds. He’s a studio hound and a microphone hound and uses old equipment that sounds great. But yet he’s not so traditionally stumped in it that he can’t find something brand new.

—Ricky Skaggs

I always liked Neil from day one. He’s got a real honest, direct delivery. He never seemed to draw too much from anybody else but himself, his own observations. He’s not afraid to go out there and work with different people . . . and then he’s still rockin’, which is great.

—Taj Mahal

Artist: Jake Early (jakeearly.com)

I like the way he is uncompromising and constantly reinvents himself. He’s like a musical brother to me in a way. And of course I got more respect for him when he played on my album than I had before. He was just amazing and played brilliantly and with so much heart, and he did it so quickly. I always knew he was a good musician, but I didn’t know he had that much fast musical acumen, which was a surprise. His own stuff might be a little more introspective and maybe take a little more time, but he worked very quickly on my album. He allowed me to cop his sound, which is very generous to let somebody do that.

—Booker T. Jones

Trade advertisement, 2008.

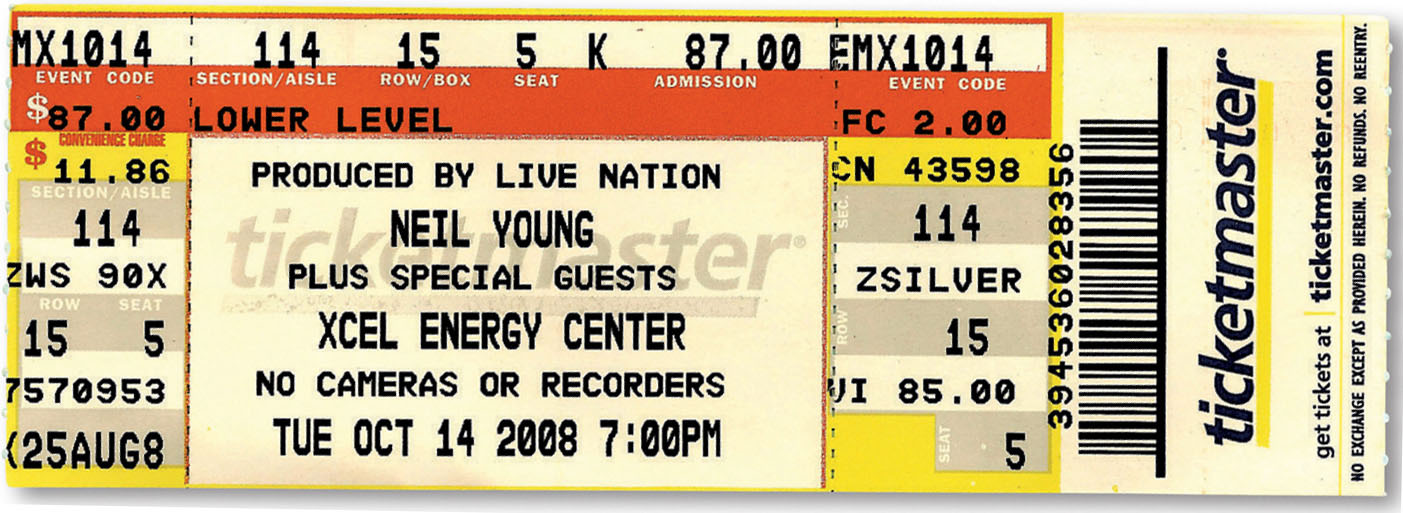

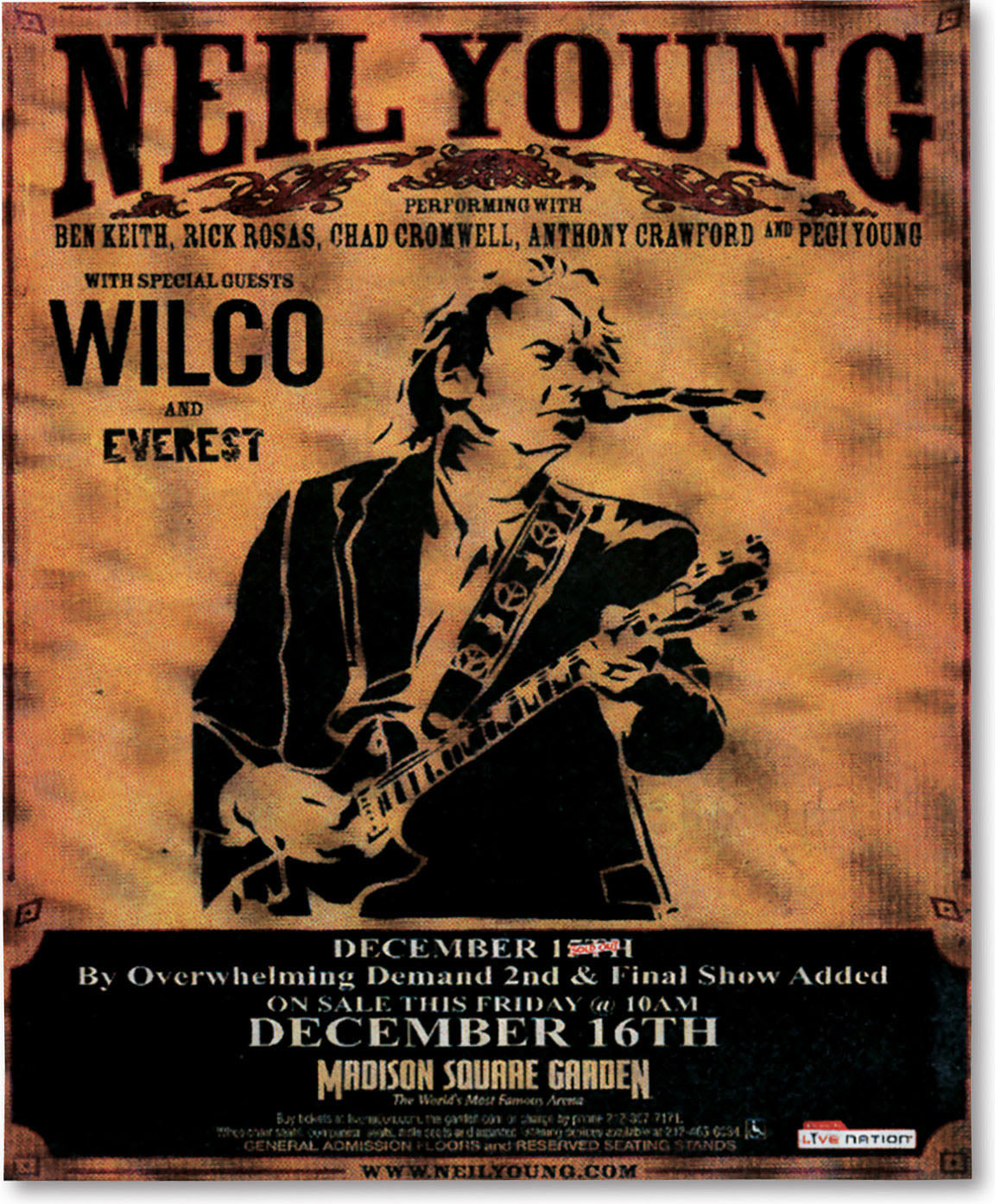

U.S. and Canada Fall Tour, Madison Square Garden, New York, December 15, 2008. AP Photo/Jason DeCrow

Released on CD, DVD, and Blu-ray, Vol. 1 spans the years 1963 to 1972 and tells his history the way Young wants it told: warts and all. “You hear the good and the bad,” Young told Rolling Stone. “A lot of people will say, ‘Well, there’s a lot of trash on this thing.’ But if you take it as a whole, it tells a story. And that’s what I like to do.”

Telling stories has always been Neil Young’s specialty. And despite having entered his sixties, he is still attitudinally true to his family name. No one, not even his hero Bob Dylan, has kept pace with him in terms of keeping his music young, fresh, vital, and forward looking. Young has, at times, faltered and even failed, but he has always remained a thoughtful songwriter, an ever-curious multimedia artist, and a live performer of the highest magnitude.

His wife, Pegi, remains his rock. Young told Charlie Rose:

Look what I have done in thirty years of marriage. How creative have I been? I have been able to do all kinds of different things, take on different characters, take on different personalities, do wacky things, get totally out of my mind, you know, drinking tequila to get into one thing, doing this and doing that, doing all of these things for all of these characters that I had to live my way through. And yet, she was sticking with me all the way through that. She deserves a medal for being open and free enough to allow me to be myself. Do you know how many people when they get married, they change, they adjust. I have not had to make an adjustment. She has allowed me to be free and taught me the beauty of the family—so I am very fortunate. Behind everyone who, you know, is doing something, there is a partner, somebody like that, a partner.

With family keeping him grounded and a little help from the great beyond, Neil Young is unafraid to fly. “We’re gonna get in there and let the muse have us,” he says as he prepares to take the stage in Heart of Gold. “Take a shot. Send it out.”