Can a costume tell a story? Can clothes be “science fiction?” And what mark have textiles made in the grand tradition of SFF worldbuilding (aka the art of imagining the day-to-day details of life in other dimensions)? As a traditionally feminine craft, textile arts have been even more neglected within the pantheon of science fiction—and sometimes intentionally made secret—than have other crafts such as design and architecture. And yet, like every lost thread, the way we dress has plenty to say about the way we live, in our imagined futures and imaginary pasts.

In this chapter, we explore the contributions of forward-thinking fashion designers who defined the look of The Future. Though their art was showcased on the catwalk instead of cosplay conventions, their expansive visions nonetheless seeped into fiction, film, and television, seeding and crosspollinating with the work of costume designers (and sometimes they were one and the same).

In the vein of costume design, we take a closer look at a lost aspect of SFF worldbuilding: the mundane yet crucial question of what people wear, and where they get it. In some lands, the women have plenty of pockets. In others, they craft with magic threads. In our own dimension, contemporary fashion icons engage in uncanny creations, weaving images with apparel that are both savage and strange.

PENNY A. WEISS and BRENNIN WEISWERDA

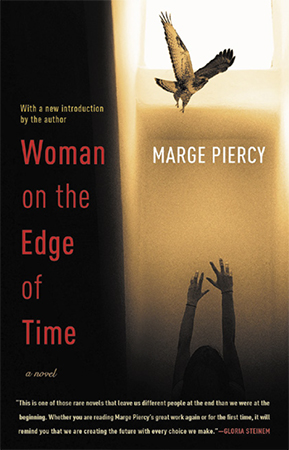

Compliment a woman on her outfit and she’s likely to tell you three things: she’ll thank you; she’ll share where she got it from, and the deal she got if it was on sale; and, if it has pockets, she’ll tell you about them. These three elements—pleasure in appearance, availability and sustainability of fashion, and functionality of design—are creatively and purposefully utilized in the feminist utopian visions of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland (see this page) and Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time.

In Gilman’s utopian novel, three male visitors are approaching the hidden community that they’ve named Herland, musing about the fashion they will find:

“Suppose there is a country of women only,” Jeff had put it, over and over. “What’ll they be like?” . . . We had expected them to be given over to what we called “feminine vanity”—“frills and furbelows.”

Yet what they find overturns their preconceptions and ultimately pleases them. The women had “evolved a costume more perfect than the Chinese dress, richly beautiful when so desired, always useful, of unfailing dignity and good taste.” The men begrudgingly admit that “[t]hey have worked out a mighty sensible dress.” One of the things that make the dress “sensible,” in addition to layers that change with temperature and task, is a stunning array of pockets:

“As to pockets, they left nothing to be desired. That . . . garment was fairly quilted with pockets. They were most ingeniously arranged, so as to be convenient to the hand and not inconvenient to the body, and were so placed as at once to strengthen the garment and add decorative lines of stitching.”

Women’s clothing in Gilman’s time was characterized by restrictions. Their traditional dress—corsets, fanciful hats, layers, ruffles—meant a mincing step, and preoccupation with what men deemed the “frivolities” of fashion—was used as justification for dismissal. The implications of clothing, Gilman knows, are political and omnipresent. The garb in Gilman’s utopian Herland has a functional, graceful simplicity, and especially emphasizes freedom of movement.

Gilman suggests that a society free from men for millennia would also be free from the patriarchal norms and limitations of masculinity and femininity; in their place is Gilman’s nuanced reimagining of motherhood. As one of the visitors notes:

“These women, whose essential distinction of motherhood was the dominant note of their whole culture, were strikingly deficient in what we call ‘femininity.’ This led me very promptly to the conviction that those ‘feminine charms’ we are so fond of are not feminine at all, but mere reflected masculinity—developed to please us because they had to please us, and in no way essential to the real fulfillment of their great process.”

This link between patriarchal pressure and toxic femininity in fashion is revelatory both to the outsiders and to Gilman’s readership. Performative femininity results from patriarchal pressure; in the absence of a male gaze, women don’t much care what they look like.

Fashion is also a means to display wealth, especially for the upper-class visitors. The visitors attempt to bribe the Herlanders with jewelry and expensive trinkets, but the Herlanders’ instinct is to put the pieces in their museums for study, not on their bodies for display. There are no class divisions in their utopia, and that carries through their fashion. There are no cheap, ill-fitting garments, and no ornate ones, either.

If there is fashion in Herland, there is a fashion, with changes dictated more by functionality or efficiency than by changing tastes or personal preference. There is no profitable industry manipulated by capitalist and patriarchal interests. The only changes or variations to clothing are to improve it; the same way their ecosystems become more balanced, or their educational games become more sophisticated, so their clothing might become ever more comfortable and practical. “In [fashion], as in so many other points we had now to observe, there was shown the action of a practical intelligence, coupled with fine artistic feeling, and, apparently, untrammeled by any injurious influences.” Gilman is finely attuned to functionality in fashion, and also pays attention to aesthetics. There is equal access to good clothing and, of course, pockets.

We find another critique of traditional women’s fashion and the fashion industry in Marge Piercy’s classic Woman on the Edge of Time. In Piercy we especially see the costs to disadvantaged women, centering the financial burden more than the physical discomfort of fashion. Unlike Gilman’s single-sex community, Piercy’s utopia, Mattapoisett, offers multiple options for individual expression irrespective of sex or gender.

Woman on the Edge of Time takes place partly in the present and partly in the future. At its center is Connie, a thirty-seven-year-old Hispanic woman living in 1970s New York, a quasi-dystopian reality that still exists today—especially for poor women of color. Connie, who struggles to get by on welfare, prizes her muchpatched purse, single tube of lipstick, and precious plastic comb. She strives to be visually acceptable and appropriately feminine to her social worker, who holds Connie’s fate in her hands, and to her well-off brother, who is another key to her freedom. The task can be overwhelming.

Connie’s niece, Dolly, is a prostitute, and fashion places similar demands on her. In order to please her pimp and attract clients, she spends her hard-earned money on the clothes, shoes, makeup, and the plastic surgery needed to meet their standards.

Piercy, and Connie, are both explicitly and eloquently critical of prostitution. Geraldo, Dolly’s pimp, “took away the money squeezed out of the pollution of Dolly’s flesh to buy lizard boots and cocaine and other women.” Geraldo’s ostentatious if “elegant” display of wealth from questionable sources is meant to increase his power, and feeds an industry that exploits divisions of wealth. Here we see the struggles that poor women have in keeping up with the demands of fashion—demands laid out not only by the fashion industry but also by welfare workers and johns, and anyone else with power they have to please.

Connie stands up for Dolly, intervening in Geraldo’s physical assault of her niece by striking him. Geraldo, seeing Connie as a threat to his control, commits her to a mental asylum. Women in the insane asylum long for their own clothing, makeup, and hair products, but such items are privileges often withheld. This dehumanizing means of control lays out with stark clarity how precious that self-sufficiency and self-expression is. “She had had too little of what her body needed and too little of what her soul could imagine.”

It’s from inside the dreary, unrelentingly gray walls of the asylum that Connie forms the mental link with Luciente, a “sender,” and travels to the colorful future of Mattapoisett. Piercy imagines—for us and for Connie—a utopia free from the constraints of class and sex roles dictated by the capitalist patriarchy.

Individual expression is found in everything from the style of someone’s hair to the tattoos on their bodies. Importantly, everyone has access to what they need: “We all have warm coats and good rain gear. Work clothes that wear well.”

The opportunities for fashion beyond function are limited only by imagination and responsible use of communal resources, and take the form of “flimsies” and costume pieces. As Luciente explains, “A flimsy is a once-garment for festivals. Made out of algae, natural dyes. We throw them in the compost afterward. Costumes you sign out of the library for once or for a month, then they go back for someone else.” Flimsies can be sensual, theatrical, or fantastical—there is no fashion industry, yet every party could be another fashion show. “Part of the pleasure of festivals is designing flimsies—outrageous, silly, ones that disguise you, ones in which you will be absolutely gorgeous and desired by everybody in the township!” For Gilman, the absence of both men and the male gaze correlates with an absence of sensuality; Piercy imagines a sensuality for all genders that is still free from the oppressive male gaze.

There is also more variety of self-expression in Piercy; in one small village we see shaved heads and intricate braids, for example, as well as men in dresses. Luciente explains what fashion can mean for her: “Sometimes I want to dress up beautiful. Other times I want to be funny. Sometimes I want to body a fantasy, an idea, a dream. Sometimes I want to recall an ancestor, or express a truth about myself.”

A common theme in Piercy and Gilman (and feminism overall) is sustainability. In Herland, resources are limited by their constrained geographical ecosystem, while in Mattapoisett people are still recovering from and making reparations for the damage caused by generations past. Sustainability comes through on all levels, in fashion as in food as in energy—everyday clothing is made to last, and everyone has enough; in Piercy, the flimsies are compostable and costumes are shared.

Fashion is more integral to feminist SFF than one might expect. Its minor role in Herland is as notable as is its vivid presence in Mattapoisett. Both Herland and Woman on the Edge of Time contain poignant critiques of contemporary femininity and the fashion industry that feeds it—and feeds on it. They come up with creative solutions to problems that continue to plague women—our pants are still not adjustable, our dresses still don’t have pockets, and fast fashion takes precedence over sustainability. Gilman and Piercy designed better futures, and better fashion, for us to work toward.

Science fiction is a genre offering visions of potential futures, and it is apparent that pretty much every medium of artistic expression has produced some version of futurism, either as a purely esthetic conceit or a more deliberate extrapolation. It is somewhat surprising to see, however, that we rarely treat fashion as a legitimate form of futuristic exploration, especially of the latter kind.

The boundary between art and fashion is at least permeable and in many cases nonexistent, so it is perhaps not surprising that the imagination finds expression through fashion—be it the Steampunk costuming community, or the surreal creations of Elsa Schiaparelli and Alexander McQueen, or the phantasmagoria of Rei Kawakubo. And yet, when it comes to science fiction, there is a notable divergence between space-era inspirations of the likes of Paco Rabanne that seem to treat the futuristic stylings and materials as mostly esthetic, and the true futurism embraced by Elizabeth Hawes and her protégé Rudi Gernreich; that is, they did not merely embrace the futuristic trappings, but genuinely grappled with what the future of humanity will be, and what will we wear when it finally arrives. What especially sets them apart is their understanding of fashion as the ultimate convergence of the human body and its role in societal change, from the labor movement to the sexual revolution.

Metallic dress designed by Paco Rabanne in the late 60s, from the collection of the Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation. Photo credit: Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation.

Elizabeth Hawes (1903–1971) was one of the greatest as well as one of the most thoroughly forgotten American fashion designers; she was a labor activist, a critic of the fashion industry, and a futurist, who could trace her fashionable roots to the Russian Constructivist movement (the esthetics of which are somewhat obscure now, but is recognizable in Bauhaus). She was a sharp-tongued and hilarious writer who criticized the fashion industry as well as the post-WWII attempt to push the female body back into domesticity, but she spoke mostly through clothes. She had designed some stunningly beautiful haute couture ensembles (a few of which, most famously her Pandora outfit, featured stylized labia), but later in her career she came out strongly in favor of agendered clothes, whose association with futurism started with Russian constructivists, such as Varvara Stepanova and Alexander Rodchenko, and was strongly aligned with the early Soviet concepts of a future society.

Constructivists saw clothing as strictly utilitarian, and believed that in the future it would be used to indicate professional affiliation rather than class or gender. It represented a move away from the past, where clothing denoted barriers and exclusion based on class. Hawes and her Russian antecedents envisioned a future where everyone was equal and where professional affiliation would be the only meaningful and visible divide. (Consider that early Communists also advocated free love as well as doing away with the institution of marriage altogether. While their record on equality between sexes is a lot more spotty, the association between the socialist movement and suffrage, as well as the work of Clara Zetkin and others, assured that there was at least lip service paid to gender-based justice.) Hawes herself was known to dress in turtlenecks under a buttoned shirt, worn with suspenders and men’s trousers, and flat shoes. And her commitment to functionality bore fruit when she designed the uniforms for the American Red Cross volunteers in 1942.

After World War II she took a long break from fashion to advocate for women’s and workers’ rights (socialism, suffrage, and labor movements were deeply intertwined still); was placed on the FBI watchlist (which later interfered with her attempts to relaunch her business by informing all her business contacts that she was a dangerous radical); moved to the U.S. Virgin Islands; knitted separates for her friends and herself; and traveled to California. Her effort to restart her fashion career there failed, but she met Rudi Gernreich, a protégé and a kindred soul.

Tunic by Paco Rabanne, created from chain-linked aluminum plates and metal wire. This piece is held in the permanent collection of the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Born in Vienna in 1922, Gernreich was among the Jewish refugees who arrived in the United States in 1938; his first job was at a morgue, where he washed bodies to prepare them for autopsies. (In the future, when a reporter asked if he ever studied anatomy—because his clothes were so body-conscious—he said, “You bet I studied anatomy.”) He later studied art at the Los Angeles City College, and apprenticed for a clothing manufacturer. He also did costume design for Hollywood but did not enjoy it. His claim to notoriety came from his radical use of new materials (he was the first to incorporate vinyl and plastic into clothing design), as well as his views of the human body, liberal even for the sixties.

Gernreich’s designs were conscious social commentary, as well as an attempt to create clothes for the “twentieth century and beyond.” He especially was interested in desexualizing the human body and making nudity normalized, not a subject of puerile voyeurism or puritanical shame. His monokini (swimsuit that exposed breasts) was famously scandalous; but he also gave us thongs, which he intended as unisex swimwear once California banned nudist beaches. He designed soft-cup bras and swimwear without built-in bras, dresses with cutouts, and short skirts. He also pushed for unisex clothing, including skirts for men. He showed his collections interchangeably on male and female models, in a way embracing true androgyny.

Constructivist gender-neutral fashion tended to be neither feminine nor masculine but rather childlike: colorful jumpsuits, simply cut tunics and pants, and emblems indicating professional affiliation were devoid of the weight of gendered expectations and designed for the ease of movement. Gernreich delighted in exposing the body for that very purpose—he was a dancer, and saw nudity as a way of freeing the body to move without inhibition; and despite the radical differences in the silhouette, the shared desexualizion marks both.

In 1970, Gernreich returned to costume design—the lovers of obscure SF may remember the British series Space: 1999 and its Moonbase Alpha uniforms designed by Gernreich. They are closer to what we normally associate with futuristic unisex clothing: matching sets and jumpsuits that conform closely to the wearer’s body. They shy away from imposing a male or female shape upon the wearer, both fitting and subverting the familiar futuristic imagery we know from hundreds of sci-fi films and shows.

In 1967, the Fashion Institute of Technology mounted an exhibit called “Two Modern Artists of Dress: Elizabeth Hawes and Rudi Gernreich.” The exhibit presented their work as a commentary on the evolution of fashion, and how quickly things like Hawes’s bias-cut, soft dresses and Gernreich’s trapezoidal shapes went from shocking to commonplace. But looking back at them fifty years later, we can appreciate that they still appear forward-looking, and we can recognize them as works of two visionaries who projected their social conscience directly onto the human shape.

Model Peggy Moffitt wearing a chevron-print jacket and skirt suit with oversize metallic buttons from the spring/summer ’68 collection by Rudi Gernreich. Photo credit: Sal Traina/Penske Media/Shutterstock.

David Bowie in concert in 1973 at the Hammersmith Odeon, London, Britain. Photo credit: Ilpo Musto/Shutterstock.

David Bowie was an artist in every sense of the word, but he was first and foremost an artist in the medium of self-image. There are few figures of the last century who are so commonly cited for their personal stylings and the effect they had on everything from trends in menswear to the look of science fiction/fantasy heroes and villains alike. And there are only a handful of others discussed with the same gravity when it comes to gender fluidity and the expression of identity through work and persona alike. In an era easily defined by toxic masculinity as a knee-jerk reaction to the sexual revolution, David Bowie remains a reminder that there is more than one way to be a man, and that fully automated luxury gay space communism can be ushered into the world purse-first.

Other writers will be happy to lead you through a gallery of Bowie’s most iconic looks; the aggressive femininity of his Ziggy Stardust years followed by the queer space pirate oeuvre of his Aladdin Sane period. The eighties when he wore menswear like a power lesbian are breathlessly followed in pictorial essays by the nineties, when he acted as the ultimate accessory to his extraordinarily beautiful wife, model and actress Iman. But let us examine the work that Bowie’s image did in the far-reaching influence of his futuristic fashion; let us define him through his legacy.

In the world of fashion itself, Bowie was both a direct and an indirect player. Hedi Slimane, former creative director of the formidable house of Yves Saint Laurent, dressed Bowie for multiple tours and brought that influence to the reigning trends in menswear, updating tired silhouettes to something slimmer and more daring than ever before, drawing on the inherent femininity of Bowie’s persona and unabashed presentation. Likewise, the late Alexander McQueen worked with the glam rocker and came back to his own house infected with new ideas. Such is the versatility of Bowie’s image as a medium that McQueen returned with the opposite direction from Slimane for designs based on the Grammy-winning artist: The wide and daringly masculine Union Jack vinyl coat that Bowie wears on the cover of his Earthling album was one of the notable results of their collaboration.

In music, there are recording artists who took their cue from Bowie in crafting an image that shocked and transgressed the masses: KISS, Marilyn Manson, and Lady Gaga (particularly her early meat-dress days), to name a few. With Bowie as their patron saint and pioneer, these folks were able to follow in a series of high-heeled footsteps that allowed them to defy gender norms (men in makeup, prosthetic breasts, and corsets in the case of the first two) and engage in the reinvention of the artist as a brand. (Lady Gaga’s trajectory from “Poker Face” to “Alejandro” is a master class in reinvention, with Professor Bowie advising her thesis.) Bowie’s example comes from a time when a singer could blithely rename himself without obliterating his online brand-building. His spiritual descendants have a different level of commitment to a personal brand, but still cannot help but follow the Pied Piper of preening when it comes to visually rebooting their public image.

In science fiction, Bowie’s influence is subtler and difficult to track, as it clearly runs two ways. Many of Bowie’s songs are science-fictional in nature, including lyrics about astronauts and other spacemen (“Space Oddity,” “Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps),” “Life on Mars”), while others engage with time travel and create speculative fiction (“Drive-in Saturday,” “Cygnet Committee”). Bowie lists some of the greats of science fiction among his influences: Michael Moorcock, Stanley Kubrick, Anthony Burgess, and George Orwell, to name a few. In all of this cross-pollination, Bowie’s queer aesthetic is at work in a genre that had been defined in the previous decades by a kind of cowboy masculinity; a James T. Kirk manliness that imagined all our future in space to be the purview of men in military uniforms accompanied by the sour-faced geeks who make it all possible with math. While Samuel R. Delany and Joanna Russ were writing to queer the soul of science fiction, Bowie was queering its image. Costumes for Luc Besson’s 1997 hit The Fifth Element bear the stamp of Bowie by way of designer Jean Paul Gaultier. Even his turn as Goblin King Jareth in Jim Henson’s 1986 musical Labyrinth, Bowie contributed to the queering of the fantasy villain/sex symbol. Jareth wasn’t just another evil fop turning coded queerness into menace; he played Jareth as a frighteningly sexual figure of magic and beguilement that led thousands of young LGBTQ viewers to begin to understand a hunger for which they had no name.

David Bowie as the Goblin King made a magical and captivating villain in Labyrinth (1986). Photo credit: Jim Henson Productions.

People throw around the word “iconic” an awful lot these days, but the thing that defines an icon is that it lasts. There are individual photos of some ragtag feather-trimmed leotards that David Bowie wore in 1974 as Ziggy Stardust that not only linger in the public consciousness, they continue to show up on runways and in science fiction costuming even now, forty-five years later. There is no other artist who can be said to have passed on a glamorous queer aesthetic to such disparate inheritors as NASA, Yves Saint Laurent, and Lady Gaga. No other singer can be credited with so substantially contributing to a popular American genre of fiction that its aesthetics are forever indissoluble from the image of their futuristic androgyny. No other person is an icon in the way that David Bowie will always be. His self-construction is his greatest, most enduring work of art.

You’ve almost certainly read this scene before: female main character declares embroidery, sewing, or other needlecraft dull and glares enviously at her brothers who get to pick up a sword. She is going to be a hero.

Instead of a mundane and necessary part of survival in the Medieval Era–influenced fantasy landscape, much like hoeing turnips or tending to horses, needlework becomes a symbol for all that is beautiful but needless in traditional femininity—something to be rejected by the heroine in her path to glory.

This rejection of the traditionally feminine craft of needlework as boring and, more importantly, useless is at the heart of many a heroine origin story. They mark her as different from the rest of the giggling girls who have nothing more on their mind than pretty things and boys. From Terry Pratchett’s Magrat declaring that being queen is “all tapestry and walking around in unsuitable dresses” to Patricia Wrede’s Cimorene trying to escape “endless rounds of dancing and embroidery lessons,” heroines have been running away from frivolous feminine needlework for quite some time.

Often the rejection of needlework is overt, like that of the titular heroine of Margaret Peterson Haddix’s Just Ella spitting out, “Why not just stay locked in the castle, doing needlepoint forever?” But in other stories, such as Juliet Marillier’s Daughter of the Forest, the heroine is simply oblivious to the fact that “other girls of twelve were learning to do fine embroidery, and to plait one another’s hair into intricate coronets,” as she reads book after priceless book.

Despite being such a huge part of medieval life, the textile arts are rarely given the spotlight in the fantasy genre that takes so many of its cues from the Middle Ages (or at least, the Pre-Raphaelite conception of it). Even when pedants are picking apart the lack of farms in Middle-earth or the Seven Kingdoms, very few ask where is the army of women who spin and weave and embroider all those beautiful clothes and banners. It is rare that the embroidered surcoat is given as much elaborate description as the armor it would be worn under.

These feminine crafts can take on this symbolic value because their practical applications have faded from our cultural consciousness due to our modern economy and manufacturing methods. With machines taking over the spinning and weaving and sewing, as well as the labor being hidden in factories, clothes have become for many of us inexpensive, even disposable. As such, the act of crafting has become a hobby and a luxury rather than a necessity.

It is thus sometimes difficult to remember that every brightly colored scrap of bunting at a medieval tournament has to be made by hand. We do not always see how tournaments demonstrate power and wealth: that it is worn upon the body of the knight as much as it is the body of the knight.

But in rare cases, fantasy worldbuilders do find ways to give the textile arts their due. Though embroidery is dismissed by the antagonist monarch of Brandon Sanderson’s Elantris as merely something that entertains and occupies women, its heroine finds allies in the queen’s sewing circle. It is those women who support her and that she leads into her reformation of the monarchy. It is also those same women who join her in practicing fencing, which she claims as feminine sport.

Brave appears at first to be a story treading old ground with a princess, Merida, who rejects the traditional trappings of femininity, preferring archery to tapestry and needlepoint. But the narrative twists to dwell on the importance of a queen’s oratory skills and how she keeps the peace among her people. The Anglo-Saxon idea that women are “peaceweavers” is echoed here, the imagery evident in her grand act of sewing together her mother’s tapestry to break the curse.

Jen Wang’s The Prince and the Dressmaker stands out as an exception as it builds an intricate world of dresses and pageantry around its central relationship of prince and dressmaker with the plot culminating at a glorious fashion show. It positions beautiful clothes not as an epitome of femininity to be rejected but instead it is to be embraced and celebrated. Department store off-the-rack clothing becomes a leveling force in society as the king asks, “In a world where department stores exist, where do kings and princes even fit anymore?”

Textile arts have an astonishing history from the smuggling of silk worms out of ancient China to the “knitted” code of the computer that went to the Moon. Half of England’s wealth was on the backs of sheep. But little of this makes its way into our fantastical worlds. Ever since Tolkien edited out the Lothlórien elves embroidering and spinning mist into rope in the early drafts of The Lord of the Rings, textile arts have become a part of fantasy’s hidden history.

“I find beauty in the grotesque, like most artists. I have to force people to look at things.”

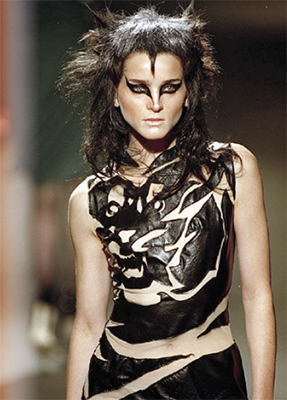

Traditionally, an evening or bridal gown closes a runway show—one last remarkable look not to be forgotten. In Alexander McQueen’s (1969-2010) fall 1998 show, inspired by Joan of Arc, the final look was a bodysuit dripping with red beads. The model’s face is completely hooded, and she stands, head thrown back, hands held stiffly palmout, within a ring of fire. The evening gown is martyrdom. The bride’s flesh is melting.

Theatricality (and the Gothic morbidity that often accompanied it) became McQueen’s calling card, and much of his work was influenced by fairy tales, movies, and contemporary art. He designed collections inspired by The Birds, The Hunger, Picnic at Hanging Rock, The Island of Dr. Moreau, vampires, and fairy stories. But his sensibility went beyond homage or spectacle, and these shows moved into the realm of storytelling in their own right. They reflected—and became—the speculative. Some beats were clearly science fiction—a model in a white dress spray-painted on the runway by robot arms, or a hologram of Kate Moss in a fluttery gown, hovering above the stage. Others suggested an uncanny connection between the human and the animal; in his “Widows of Culloden” show, a bride sported antlers that plowed through her veil. But the varied methods reflected the same story: all things are beautiful; all things are strange; all things are doomed.

Alexander McQueen Collection at London Fashion Week, February 28, 1997. Photo credit: Ken Towner/Evening Standard/Shutterstock.

This slightly fantastical sensibility is the designer’s legacy, a sense of story that gave cultural weight to the tailoring. (We appreciate a lovely dress; we remember a dress with a story.) And his embrace of the Gothic monstrous explored the industry’s own preconceptions of acceptable beauty, which collided frequently with his passion for the uncanny. At the end of his spring 2001 show, glass walls dropped to reveal writer Michelle Olley, naked save for a gas mask, amid a cloud of live butterflies and moths in an homage to photographer Joel-Peter Witkin’s “Sanitorium.” During “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?,” which recreated a Depression-era dance contest, the final model ‘died’ on the dance floor, and stayed there until after the bows (when McQueen helped carry her offstage). For his Spring 2007 collection, he sent a gown of real flowers down the runway, which fell apart as the model walked; fashion, nature, youth, and other fleeting things.

McQueen, in the exploration of these stories, designed his share of unwearable garments; among the finely-tailored blazers and carefully-draped dresses were challenging, restrictive pieces that required a body as a sacrifice as much as for a model. (This is a man who interpreted vampires via a transparent bustier filled with worms, and commissioned a metal spine-and-ribcage corset as a couture exoskeleton.) But as his runway shows garnered attention and his gowns became red-carpet staples, the more his Gothic-couture aesthetic was accepted by the mainstream.

Even if you think you haven’t seen a McQueen, you may well have. Works from McQueen’s latter collections were so aligned with current ideas about fantastic fashion—a sensibility he helped craft with a decade of conceptual shows—that his pieces sparked several onscreen homages. Look no further than Fleur’s wedding dress in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part One (a near-direct copy of a piece from the Fall 2008 collection) and Queen Ravenna’s cape in The Huntsman: Winter’s War (inspired by a gold feather coat from the Fall 2010 collection—the last he designed).

McQueen wasn’t free of controversy; a designer who tried so deliberately to provoke was occasionally bound to do it. (In his spring 1997 show, he sent Black model Debra Shaw down the runway in a square shackle that hemmed in her elbows and knees; he insisted it was commentary on constrained bodies, but for obvious reasons, debate raged.) But his darkly-fantastic speculative collections, and the shows that accompanied them, are his most visible and enduring legacy. He died in 2010; the last collection he completed was “Plato’s Atlantis” (featuring the ‘armadillo boots’ Lady Gaga made infamous). The concept itself was science fiction: climate change so severe it prompts a new era of human evolution—into sea creatures. “When the waters rise,” he noted, “humanity will go back to the place from whence it came.” It was beautifully doomed—with McQueen, what else would it be?