FOREWORD

As a twelve-year-old, lo those many decades ago, I would sneak away from my school’s expeditions to the public library and set up camp in the adult section—especially the science fiction and fantasy section, where I would read through any number of pulp magazine anthologies. The Best of Galaxy was a particular favorite of mine because the stories were so weird, and often mysterious—a fair number of them might even be called science fantasy.

Whether it was flying coffins invading earth, a misdelivered anatomy package from the future wreaking mayhem, or a future under-earth populated with talking animals, I was transported by amazing imaginations and ingenious stories. I discovered writers that I still read to this day, some of them mentioned in this volume, like Cordwainer Smith and Jack Vance. To me, as a kid, speculative fiction was mysterious and, yes, a secret experience.

This feels like the right way to have been introduced to science fiction and fantasy, long considered low and debased genres, not at all “serious.” Many of us had to sneak off to read it outside of class, which was generally bereft of such material except in the most boring and unexciting iterations. How, as a teenager, I would have loved to read a book like Lost Transmissions—a guide to a wealth of unusual treasures.

Because the thing about science fiction and fantasy is this: They always need more histories and more books that reclaim or examine what has been hidden or forgotten. Science fiction in particular started out as a kind of mom-and-pop genre, which lends itself to a “secret history” as well—a fan-based, pulp-book culture, a genre that allows for mash-ups of all kinds and whose collective history might be relegated at times to mentions in mimeographed fanzines.

Fantasy could always fall back on the world of myth and legend for legitimacy, but the term “science fiction” more or less came from the US pulp magazines of the 1920s that mostly published startling adventure stories set in space, by a very white and male set of authors. Within certain constraints, however, science fiction also allowed for the flourishing of unique and bizarre imaginations. In fact, the state of the field has always been more complex than memory suggests, sustaining ebbs and flows of acceptance of certain types of writers. For example, translated SF and work from outside of core genre gained more acceptance in the 1960s and 1970s, under the aegis of editors like Frederik Pohl and Damon Knight and Michael Moorcock—with the 1980s also seeing a flowering of translations of Soviet SF in anthologies published by McGraw-Hill and championed by Theodore Sturgeon. This is not to mention the rise of feminist science fiction and fantasy in the 1970s and the more recent influx of nonwhite writers into the field, both pivotal moments that utterly transformed science fiction and fantasy into something ever richer, more imaginative, and more open to all readers.

The book you hold in your hands provides an admirable introduction to the secret history of science fiction and fantasy—not just through my entry point (books!) but other media as well—guided by an able assemblage of contributors providing an abundance of points of view. (The work of those contributors could itself form an amazing speculative anthology worthy of further exploration, including wonderful creators like John Jennings, Ekaterina Sedia, and Charlie Jane Anders, to name just three.)

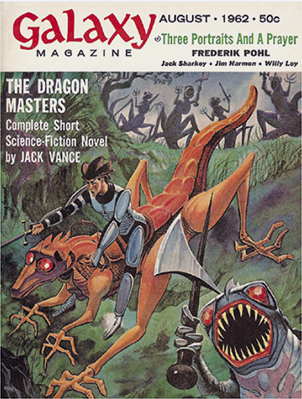

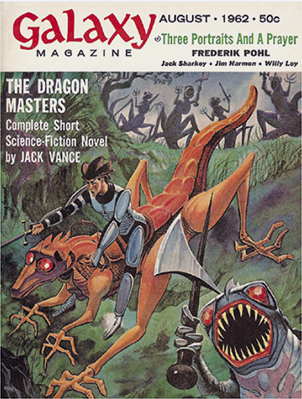

Galaxy Science Fiction ran from 1950 to 1980. Under the guidance of editors H. L. Gold and Frederik Pohl, Galaxy became possibly the most influential SF magazine of the era, publishing luminaries such as Alfred Bester, Ray Bradbury, Harlan Ellison, Cordwainer Smith, and Jack Vance.

The joy of a compilation like Lost Transmissions is that it is itself a kind of secret eccentricity, cataloguing misfits and ne’er-do-wells possessed of astonishing imaginations. As an editor of reprint anthologies of science fiction and fantasy I am always struck by the unjustness of who becomes successful and who does not—the luck, bad fortune, and other factors—and thus the immense responsibility of reclaiming the underappreciated, the misunderstood, the forgotten.

This book conjures up not just a sense of wonder for its work in that regard, but also gives readers the sweet regret of might-have-beens. What if this film had been made or that book written? (We cannot, of course, know how many existing books and movies once teetered on the edge of oblivion, of never reaching an audience.) So, in a sense, Lost Transmissions is itself a science-fiction narrative, daring us to imagine other timelines and other universes in which things turned out differently and, for example, William Gibson made an Aliens movie.

And yet, no secret history can include the secret history entire. One reason for this is that one person’s perception of “secret” is so different from another’s. Take my treasured memories of childhood reading in the library. Cordwainer Smith was a giant in my mind, someone I just assumed everyone knew and read, while I never would have guessed, to be honest, when I first encountered Isaac Asimov, that he was practically a household name. We create by our enthusiasms and our passions the secret history we need and deserve, and, you, dear reader, are no different.

If you know nothing of science fiction and fantasy, Lost Transmissions will be an utter revelation; for others, it will be an affirmation of favorites you’ve carried a torch for, for years or even decades. Some readers may even curse and say, “What about X, Y, and Z?,” for that is the joy of cultivating eccentric tastes. But what this book provides for all readers is a beautifully illustrated and edited jumping-off point for your own memory cathedral—your own secret history.

I hope you think of this book not as a destination but as part of a continuous and fulfilling journey, one of unexpected discoveries and storytelling joys that grows in the imagination and fuels your curiosity and passion. And with that good thought, I will get out of the way to let you enjoy the book before you.

Jeff VanderMeer

Tallahassee, Florida

February 2019

The King in Yellow by Vicente Valentine (tribute to Robert W. Chambers).