CHAPTER TWO

DRIVE-BY STRIKES

Throughout the Vietnam War the US Navy had used the same aircraft paint scheme of gloss light gull grey over white that it had adopted in 1956. While the USAF had gone to camouflage for its tactical aircraft early on in the conflict, the US Navy seemed to revel in bright, vivid paint schemes where some squadrons tried to out-do each other in the spectacular use of colour. The message was clear – ‘We don’t care what you see. Come and get us.’

Although they called it ‘All-Weather A Coral Sea between flights. When this photograph was taken the ship was swinging through the Bering Sea off Alaska at the start of its 1983 ‘Around the World’ cruise as it transferred to the Atlantic Fleet. ‘Milestone 507’ BuNo 157017, on the left, is an A-6E CAINS, while ‘Milestone 514’ BuNo 151592 is a KA-6D (US Navy)

That all changed in the late 1970s when Naval Aviation came to the conclusion that being less visible was probably not a bad idea. Within the fighter community it was realised that delaying visual detection offered a serious advantage in the aerial arena against both air and ground threats. The shift in thought quickly went fleet-wide. It therefore started a multi-year campaign to reduce the visual signature of its aircraft. What the service ended up with was named Tactical Paint Scheme (TPS), which was codified in the document Mil-STD-2161(AS) ‘Paint Schemes and Exterior Markings for US Navy and Marine Corps Aircraft’. The long-standard grey and white aircraft finish was replaced by TPS, which was described as ‘a color scheme to reduce visual detection comprised of shades of flat gray with exterior markings in a contrasting shade of gray’.

As originally mandated, the Intruder received a two-tone dull grey motif in Federal Specification (FS) shades 36320 and 36375. The instruction also specified that all other markings had to be in the opposite colour, which meant, at least initially, an end to the full-colour schemes that had graced carrier aircraft since the mid-1950s. While there was a proviso for painting no more than one aircraft per squadron (suggesting a ‘CAG bird’ or ‘Easter Egg’) with squadron markings in full colour, it had to be approved by the local Type Commander, who was not always agreeable. KA-6Ds were specifically authorised to keep the existing grey and white scheme in order to aid tanker recognition, although some Oceana units actually re-painted a small number of KA-6Ds into overall grey on their own initiative in the mid- to late 1980s.

The narrow limits of the direction soon caused issues in the fleet as freshly painted aircraft quickly weathered under the sun and salt-air environment and the dull paint had a habit of seemingly absorbing dirt. The result was aircraft turning into an ugly mass of blotched greys and light blues as squadron corrosion shops worked hard to keep up with their work using whatever paint they could find. As was commonly stated in the fleet, ‘if the aircraft don’t come home from cruise looking awful then you’re not doing your corrosion work right’. Over time the TPS instruction was modified to reflect reality in that side numbers were soon changed to black or very dark grey, as the original shades faded into each other. Improved paint quality and application methods eventually helped the overall look of US Navy aircraft so that by 1990 the ‘leper’ appearance was greatly reduced and small areas of colour were tolerated by higher authority for safety or morale purposes.

‘HAZE GRAY’ AND UNDERWAY

By 1980 the nation had been largely at peace for almost seven years. This started changing as new threats emerged and evolving US foreign policy moved towards applying limited force on specific targets, frequently using the military to achieve political goals in a Clauswitzian sense.

During the mid-1980s Naval Aviators started training regularly with USAF ‘big wing’ tankers in order to understand Air Force procedures and the challenges of duelling with the KC-135’s hard ‘Iron Maiden’ refuelling basket, which was much trickier to deal with than the soft US Navy basket they were used to. This familiarity would pay off later during Desert Storm. Here, a virtually anonymous VA-196 A-6E is plugged into KC-135A 56-3646 from the 92nd Bomb Wing (BW) while over central Washington on 28 April 1984 (Author)

Within the US Navy the term ‘drive-by strike’ was coined for those raids that typically lasted only one day, where sustained military operations were neither needed nor desired. Not surprisingly, the service’s deployed carrier force was perfect in this role. It was during this period that the noted point was made that whenever trouble arose in the world, the first thing the President famously asked was ‘Where are the carriers?’ And the Intruder had a critical role in this effort. The rise of certain nations and specific non-state actors hostile to the United States in the 1970s drove a rapid change to the way the fleet deployed. The days of ships spending more time in port than underway was over and air wings began to look at potential enemies other than the Soviet Union. According to one retired A-6 B/N;

‘Every carrier that chopped to Sixth Fleet [in the Mediterranean] prepared detailed folders on a variety of potential targets throughout the region, typically focusing on what were now being regarded as “terrorist” nations. Most had to be briefed up to the flag level for approval, with some of them involving strikes deep into certain countries – so deep it was going to be Intruders only as the F-14s and (later) the F/A-18s didn’t have the range.’

Occasionally referred to as the US Navy’s ‘Foreign Legion’, CVW-5 remained forward deployed with Midway from 1973 through to 1991. Here, VA-115 A-6E NF 511 BuNo 159579 is launched off cat two with a load of Mk 76 practice bombs on the centreline in 1981 (US Navy)

Targeting was also improved as the new generation of ‘smart’ weapons, soon combined with the A-6E TRAM, provided options that had never been available before. As one senior A-6 pilot put it, ‘where we used to have to take a division of Intruders with racks of Mk 82s each, we now planned for LGBs, where one or two aircraft could do the same job’. Specifically, where strike planners once had to count on a string of ‘dumb bombs’ to take out a target, they were soon talking about which specific window of a building they were going to put their LGBs through to achieve the desired effects. Nonetheless, the Mk 82 and Mk 20 Rockeye retained utility for many target sets, and would remain in the Intruder’s weapons lockers until the end.

One of the first international crises that had to be monitored was the Iranian Revolution, which had been brewing for years as the US-supported Shah of Iran dealt with ever increasing civil disruption. Suddenly, the Indian Ocean (‘IO’) became relevant, and ships started routinely deploying in this region. The first carrier to conduct flight operations from what would soon be known as ‘Gonzo Station’ (an acronym adopted by the US Navy for the Gulf of Oman Naval Zone of Operations) was USS Constellation (CV-64), with CVW-9 (and VA-165) embarked. The carrier had departed the South China Sea on 2 February 1979 on what was officially described as ‘Contingency Operations’ to support US citizen evacuation as the country descended into chaos.

Despite the logistical problems associated with manning ‘Gonzo Station’, the US Navy started an almost continuous presence in the ‘IO’ with battle groups centred on the aircraft carrier. For ships’ crew the change meant a lot more time underway and a lot fewer liberty ports to visit. In the ‘IO’ the US Navy turned the small archipelago at Diego Garcia into a supply hub to support the fleet’s presence on ‘the far side of the world’. Single carriers continued to operate in the Gulf of Oman or off Yemen through to 4 November 1979, when ‘students’ took over the US embassy in Tehran, capturing 53 American diplomats and military personnel in the effort.

One immediate response from the US government was to order the deployment of a second carrier to the area, with USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63) (CVW-15/VA-52) joining Midway (CVW-5/VA-115) on 21 November. While the Carter administration publically insisted that diplomacy would be used to free the American prisoners, the presence of two carrier battle groups seemed to imply that there were other, more violent, options that were not out of the question.

By the spring of 1980, the US Navy’s two carriers on station were Coral Sea (CVW-14/VA-196) and Nimitz (CVW-8/VA-35), the latter being the first Atlantic Fleet ‘flattop’ to sail in the Arabian Sea. Both were now waiting for the National Command Authority to authorise an audacious raid to attempt the rescue of the captured Americans. Unbeknownst to practically anyone outside those on ‘Gonzo Station’, the US Navy had sent a squadron of RH-53D Sea Stallion helicopters into the region, the machines, belonging to anti-mine squadron HM-14, having been secretly flown aboard Kitty Hawk from Diego Garcia. Eventually transferred to Nimitz, the US Navy helicopters would perform a critical role in the upcoming event.

On the night of 24 April 1980, the RH-53Ds departed Nimitz with US Marine Corps flight crews at the controls, thus signalling the start of the US Navy’s contribution to Operation Eagle Claw – a complex event that would require detailed timing and involve men from every service. On board the two carriers, aircrew prepared for strikes well into Iran, up to and including Tehran. Their purpose would be to support the egress of the transports that were going to be used to bring the hostages and a US Army rescue team out of country. Contrary to what President Jimmy Carter told the country, US Navy and US Marine Corps flyers (Coral Sea having F-4N-equipped VMFA-323 and VMFA-531 embarked) knew that the prospect of civilian casualties was actually high.

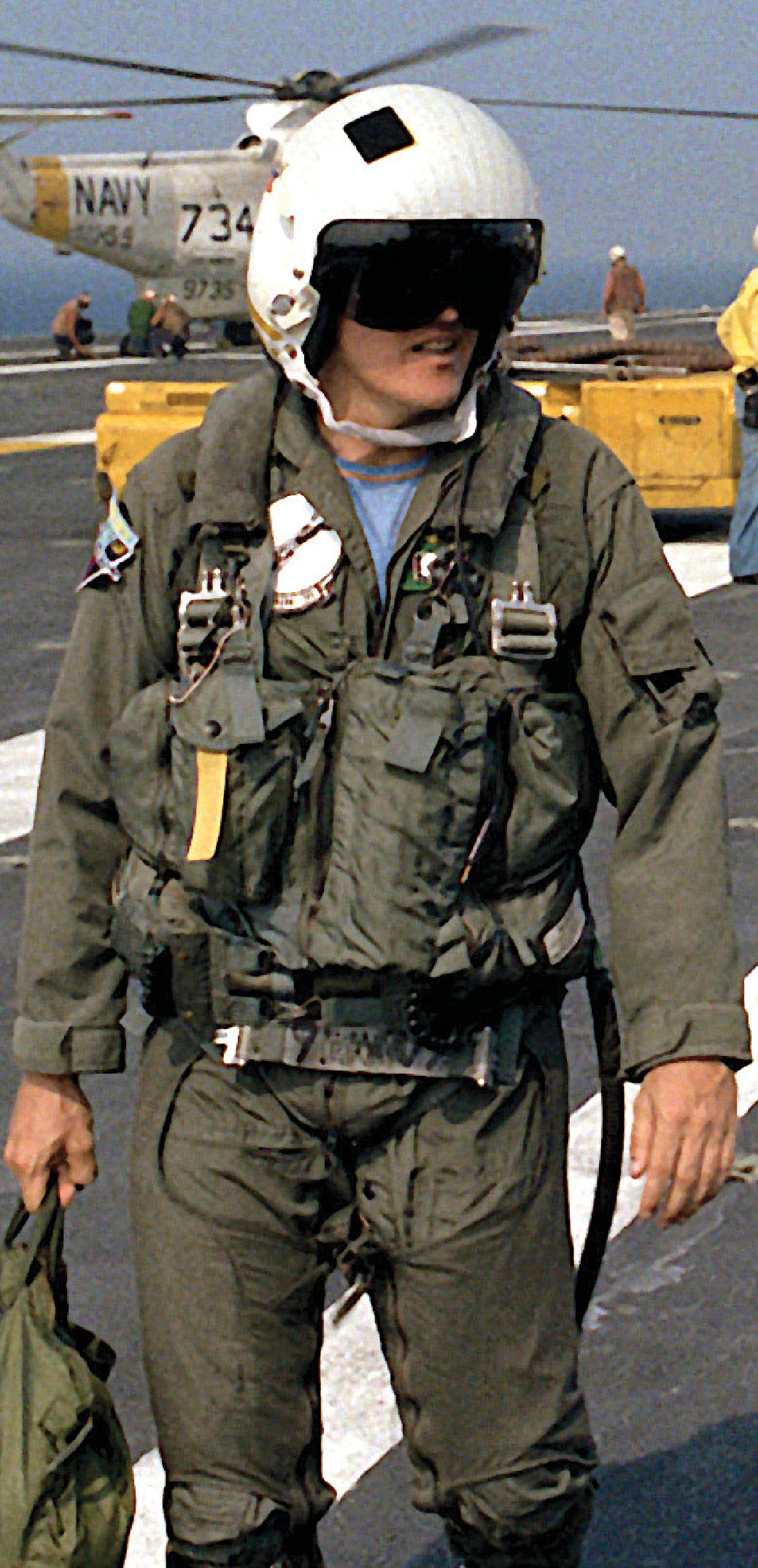

John Lehman, a Naval Reservist and qualified A-6 B/N, became Secretary of the Navy in 1981 and immediately made an impact on the vision and direction of the service. He continued to fly as time allowed, and is shown here on the flightdeck of Nimitz after trapping in a VA-42 aircraft in July 1981 (US Navy)

Both air wings had painted ‘invasion stripes’ on their aircraft in order to ensure visual identification against a potential enemy that also flew F-4s and F-14s. The word to prepare for launch came and crews were ready to fly wherever needed to help support what they now knew was an attempt to rescue the hostages in Tehran by force. And then they had to stand by as the entire affair was aborted due to the calamity in the desert at a location now known as ‘Desert One’, where attempts to refuel the rescue helicopters from USAF EC-130s went badly wrong resulting in the loss of eight servicemen. In the end neither carrier nor air wing would launch a single strike into Iran. And the hostages would have to wait until January 1981 to be released.

JOHN LEHMAN AND INTRUDER GROWTH

In 1981 newly inaugurated President Ronald Reagan named John Lehman the 65th SECNAV. Lehman, a remarkably self-assured, Ivy League-trained man who was also an officer in the Naval Reserve, qualified as an NFO and A-6 B/N. He quickly became the lead proponent for a ‘600-ship Navy’, with its centrepiece being a force of 14 nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. Within this strategy was an increase in the number of Intruders assigned to the air wings, with a goal of having two Medium Attack squadrons on each ship.

The new requirement was for an additional 12 squadrons, with air wings taking one of three forms, depending on the ship they were assigned to;

- Coral Sea air wing – Intended for the two remaining Midway -class ships, with two eight-aircraft VA(M) units and three 12-aircraft VFA squadrons flying F/A-18A Hornets. Both Midway (with CVW-5) and Coral Sea (CVW-13) would deploy with this arrangement.

- ‘All-Grumman’ air wing – Also called the ‘ Kennedy air wing’, described as an ‘experimental’ structure with two large VA(M) units and no light attack or strike-fighter assets. The term ‘All-Grumman’ was commonly used as only 24 F-14 and 24 to 28 A-6 aircraft were assigned, as well as EA-6Bs and E-2s, while ignoring the ten S-3s also onboard. Within the US Navy there was some belief that this plan had a secondary goal to show McDonnell Douglas that it might not need ‘short-ranged’ F/A-18s to have a powerful CVW. John F Kennedy (CVW-3) and Ranger (CVW-2) would be the only two carriers to deploy with this arrangement.

- Notional air wing – In what was said, for a short period, to be the ultimate air wing, the ‘Notional’ CVW featured two squadrons of ten to twelve aircraft each of VF, VA(M) and VFA, along with the ‘cat and dog’ units (VAQ, VAW, VS and HS) for 86 aircraft in total. While at one time the US Navy officially planned to make this the standard for the entire fleet, the cost and size of the effort led to only one CVW ever being formed under its blueprint, with CVW-8 and USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) making only two deployments as such, before reverting to the older standard, with only one A-6 unit onboard.

Lehman’s ambitious plan was to have, by 1992, 28 VA(M) squadrons flying Intruders with one Midway, 11 Notional and two Kennedy wings assigned to 14 aircraft carriers. On 7 October 1983 VA-55 was established at Oceana as the first of the new squadrons. It adopted the nickname and insignia of the previous VA-55, which had been disestablished as an A-4F-equipped unit in 1975. The ‘War Horses’ joined the equally new CVW-13, bound for Coral Sea, which was slated to end its years in the Atlantic Fleet. While intended as part of a two Intruder squadron air wing, VA-55’s first deployment would be with four F/A-18A squadrons.

The ‘Lehman Plan’ continued in 1986-87 as three more Intruder squadrons were quickly established, being led off by VA-185 at Whidbey on 1 December 1986. The ‘Night Hawks’ carried a new designation with no historical predecessor. While originally planned for new (and short-lived) CVW-10, it soon moved to Japan to join VA-115 in CVW-5. Three months later, on 6 March 1987, VA-36 broke its flag out at Oceana. The ‘Roadrunners’ bore the title of another past A-4 unit, which had been disestablished in 1969. The squadron was assigned to CVW-8 as part of the first (and only, as it turned out) ‘Notional air wing’, joining the ‘Black Panthers’ of VA-35.

On 1 September 1987 the second new Whidbey unit was formed as the ‘Silver Foxes’ of VA-155 were established, returning a designation last used by a Lemoore-based A-7 squadron. Initially assigned to CVW-10, it became the only unit in that wing to survive its June 1988 closure. The ‘Foxes’ then joined CVW-17 for a short trip around the Horn in USS Independence (CV-62), before moving to CVW-2 to replace US Marine Corps Intruder unit VMA(AW)-121 in that ‘All-Grumman’ air wing.

VA-36 was newly formed during the 1980s, adopting the name and traditions of an A-4 unit disestablished in 1969. Assigned to CVW-8, the squadron would make all four of its cruises on board Theodore Roosevelt. VA-36 never deployed with KA-6Ds, instead equipping a number of its A-6E TRAMs with buddy stores as and when required. Here, AJ 540 BuNo 158538 trails a hose out of its buddy store in November 1990. The jet is carrying four additional external fuel tanks in what was referred to as ‘maxi-tanker’ configuration. If it had only a single tank under each wing the A-6 was set up in ‘mini-tanker’ configuration (Author)

By late 1987 reality set in as it was obvious that the US Navy did not have enough money or people to continue building ‘Notional air wings’ and had to eventually go back to a standard five-squadron two VF, two VFA/VA(L) and one VA(M) configuration for its air wing core. Not only did four CVWs eventually disestablish (CVW-13, CVW-6, CVW-15 and CVW-10, the last of which had never fully formed), but the Lehman goal of 24 Intruder squadrons evaporated as well. When the decision was made, Oceana was preparing to establish the ‘Ubangis’ of VA-12 as a new Intruder unit and Whidbey had plans to form VA-164 as its next Medium Attack squadron. Official correspondence inside the Whidbey wing indicated that the next four would have been VA-212, -215, -56 and -93, all former light attack designations. In the end it was not to be, the result being that the regular US Navy’s Medium Attack community reached its apogee at 16 squadrons in 1987.

As of March 1988 there were 410 Intruders in the inventory – 342 A-6Es and 68s KA-6D. The production line remained open, with 12 to 24 new aircraft ordered annually for at least four more years. However, John Lehman’s April 1987 resignation and the end of the Reagan-era defence budgets forced the US Navy to completely re-think its acquisition and growth strategy during the late 1980s. Despite the reduction in funding, the legacy of Lehman’s efforts would soon be seen in action in the deserts of the Middle East as, notably, the final three of the ‘dual A-6’ air wings would fight in Operation Desert Storm as part of the same Task Force.

URGENT FURY

Independence departed Norfolk on 18 October 1983, with the ship and CVW-6 expecting to proceed to the Med to relieve Eisenhower. Instead air wing personnel soon realised that they were heading south, not east. Their new destination, which had been a closely kept secret, was the small Caribbean island of Grenada, located about 80 miles north of Venezuela. The Reagan administration had determined that the ‘New Jewel Movement’ government of Grenada had moved too far towards the communist sphere and become too cosy with Cuba in particular. There was also the concern that expansion at the island’s primary airport would allow use by Soviet long-range bombers. Therefore, the regime had to be overthrown.

A dramatic shot of VA-95 A-6E NH 502 BuNo 161090 flying a low-level route in eastern Washington in August 1985, this photograph being taken out of his wingman’s B/N’s window. The aircraft appears to be at least 500 ft above the ground – in a tactical situation Intruders flew as low as feasible, with many crews being comfortable down at 200 ft, or less, even at night (Bruce Trombecky)

‘Indy’ and its battle group arrived off the island to begin operations on 25 October in support of what was now called Operation Urgent Fury. US forces, including Marines (from the 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit, centred on the amphibious assault ship USS Guam (LPH-9)), US Army troops and special forces came ashore by helicopter and parachute to take control of the island and rescue a group of American students at a medical school.

Embarked as CVW-6’s Intruder unit was Cdr Mike Currie’s VA-176, which provided CAS for US forces while also carrying out tanking and sea control functions. The air wing’s two A-7E squadrons (VA-15 and -87) were even more heavily involved. The fight for Grenada was short, with the situation being declared over by 2 November. While CVW-6 had taken no losses, the operation had still cost the lives of 18 American troops and resulted in the destruction of two US Marine Corps helicopters.

DEBACLE IN LEBANON

With Grenada wrapped up, the ‘Indy’ pressed on to the Mediterranean, where it finally relieved Eisenhower (CVW-7/VA-65), which headed for home. These were still the days of Sixth Fleet having two carriers assigned, and CV-62 joined John F Kennedy, which had CVW-3 – the first ‘dual A-6’ air wing – embarked. The senior officer on board CV-67 was the legendary Vice Adm Jerry O Tuttle, a short, fiery Naval Aviator with a light attack pedigree who was double-hatted as Commander, Carrier Group Two as well as Commander, Battle Fleet Sixth Fleet.

Foremost on the international stage at this point was the disintegration of Lebanon, as what had once been called ‘the Paris of the Middle East’ degenerated into violence and chaos involving multiple groups using assorted religious justification. The US government, fearing a much bigger war involving Syria and Israel, put Marines ashore in Beirut in order to help stabilise a situation that was rapidly headed south. It also placed two carriers off the beach to show national resolve.

According to one of Tuttle’s staff officers, Lt Cdr Joe Hulsey, ‘we had been on constant alert for weeks, with one carrier being in “alert 30” with aircraft fully loaded and crews briefed, while the other flightdeck conducted normal flight ops. This changed every 24 hours in order to share the load. The force was ready, having prepared more than 300 potential targets in the region. We had timing and weapons loads planned for all of them, and all of this information was sent up the chain to Sixth Fleet and CINCEUR [Commander in Chief, US Forces Europe] so that they’d know what we were prepared to do. On top of that, we had Jerry Tuttle in charge. He was exactly who you’d want in that position if you were going over the beach.’

The hair-trigger condition continued until about 1 December, when the carriers received direction to stand down from constant alert. Then, at about 0300 hrs on the morning of the 3rd, a Flash order arrived from Sixth Fleet to execute strikes against six specific targets in Lebanon, with a time on target (ToT) of only four hours later. The order was initially believed by the staff to have been sent in error, but as messages and voice traffic flashed between the ships and Sixth Fleet it became obvious that ‘somebody’ much higher had decided on military action with absolutely no regard for what it took for the operational forces to actually execute it.

The first deployment of a ‘dual A-6’ air wing occurred in 1983 when VA-75 and -85 embarked in Kennedy with CVW-3. The US Marine Corps took the ‘Black Falcons’’ spot for the following two Mediterranean cruises, with the ‘Nighthawks’ of VMA(AW)-533 doing the honours. In this action photograph, a launch is in progress off ‘Big John’s’ catapult one, with nothing but Intruders in sight. A KA-6D from VA-75 (it was the only Intruder unit in CVW-3 equipped with the KA-6 at that time) is clearing the bow while Marine aircraft AC 550 BuNo 158529 waits its turn behind the jet blast deflector. Note how the markings on this aircraft are barely legible from this angle due to the heavily weathered TPS. AC 507 BuNo 155716 is a VA-75 A-6E TRAM with a MER-full of Mk 76 practice bombs (Rick Burgess)

Aircraft were not ready or correctly spotted on the flightdeck, proper ordnance was not loaded and crews were not briefed. On top of that, only one of the six specified targets had actually been prepared by the ships, and the other five, considered militarily irrelevant, were all new. While the ships rapidly woke up, it was confirmed that the ToT was an absolute that had to be met, which led to an all-hands effort to carry out their orders.

What followed was a disaster.

Kennedy launched 12 Intruders (seven from VA-85 and five from VA-75) and Independence sent five aloft, along with several KA-6Ds. A-7Es from ‘Indy’ went as well, as did Tomcats and Prowlers from both carriers. Ordnance loads were limited by time available and, in most cases, were not optimum for their targets – Syrian tanks and AAA sites in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, close to the Syrian border. Only one Intruder from Kennedy got off with a full bomb load. Aircraft went feet dry at medium altitude at dawn, and almost immediately were engulfed by AAA and missiles. While EA-6Bs appeared to render any radar-guided SAMs ineffective, the sky was full of infrared-guided weapons blind to the Prowlers’ magic.

The one fully loaded Intruder, ‘Buckeye 556’ (BuNo 152915), found itself working hard to keep up with the rest of its formation. On board were pilot Lt Mike Lange and B/N Lt Bobby Goodman. Infrared decoys and flares filled the sky as aircraft tried to avoid the SAMs coming up from the ground. ‘Buckeye 556’ was soon hit, probably by a Syrian 9K31 Strela-1 or Strela-2 infrared-guided SAM. The crew ejected, and Lange soon succumbed to injuries suffered in the process of leaving the aircraft. Goodman was turned over to Syrian troops and duly spent several weeks in a jail near Damascus. He would be released after a flurry of diplomatic work that included the appearance of The Reverend Jesse Jackson.

Through the hail of fire, the Intruders and Corsair IIs delivered ordnance on their assigned targets, the ‘Thunderbolts’ specifically dropping 25 Mk 82s, 23 Mk 83s and 30 Rockeyes.

CAG-6, Cdr Ed Andrews, was flying VA-15 A-7E ‘Active Boy 305’ (BuNo 157468) and he took over as on-scene search and rescue commander for the downed Intruder. He was soon hit by an infrared-guided SAM himself and had to eject off the coast, where he was picked up by friendly fishermen and eventually returned to the US Navy. VA-15 Corsair II ‘Active Boy 314’ (BuNo 157458) was also hit, but its pilot was able to recover aboard Independence.

As stated by Lt Cdr Hulsey, ‘even six more hours would’ve made all the difference in the world, but they wouldn’t give it to us. We found out later that the source (presumably out of Washington, D.C.) didn’t even get the time zone conversion right in the message, which cost us at least two more hours to prepare.’ As the saying goes, ‘Success has a thousand fathers while failure dies an orphan.’ In this case, who actually picked the targets and ToT is still unknown. While bombing results were officially described as ‘effective’, on board both ships, and throughout carrier aviation, there grew a rapid and long-lasting bitter taste over the strike. Professionally, the event was viewed as nothing short of a failure that would eventually lead to a number of changes, including the formation of ‘Strike U’ at Fallon to develop and teach more effective air wing tactics.

ENTER THE ‘BUG’

In 1983 the McDonnell Douglas F/A-18A Hornet joined the fleet to much fanfare. The new ‘Strike Fighter’ would soon replace the last F-4 Phantom IIs in the US Navy, as well as beginning an eight-year march that eventually killed the dedicated Light Attack (A-7) community.

Another Intruder down low, in this case VA-196 A-6E TRAM NK 511 BuNo 152610 on a CVW-14 ‘raid’ on China Lake, California, in January 1985, with the Sierra Nevadas as a backdrop. The Intruder was carrying a MER with six Mk 76 practice bombs underneath its port wing. The escort F-14As from VF-21 were actually lower than the A-6 on this occasion, the fighters tangling with adversaries from VF-126 as the strike package neared the target (Author)

What the Hornet had was ‘flash’. It was new, sexy and featured a good mix of air-to-air and air-to-ground capability. What it did not have was range, quickly proving no longer-legged than the Phantom IIs it replaced and having nowhere near the combat radius of the A-7, let alone the A-6. It also did not have, at least initially, the same sensor and ‘all-weather’ capability of the Intruder – but then it was not supposed to have this ability either. What it did have was a decent radar and much better self-defence capability, while also being considerably cheaper to operate than the A-6.

CVW-14 would be the first US Navy air wing to get the Hornet when it welcomed Strike Fighter Squadrons (VFA) -25 and -113 aboard in 1983. The air wing’s VA(M) role was covered by the ‘Main Battery’ of VA-196, Cdr Bud Jupin’s unit taking nine A-6E TRAMs and a quartet of KA-6Ds to WestPac in Constellation from 21 February 1985. VA-196 worked hard on a cruise that went into the ‘IO’, being determined to show that Medium Attack still had a critical role to perform on the carrier. With both Tomcats and Hornets now routinely requiring refuelling (and no A-7s to help carry the load nor S-3s qualified at that point), the ‘Milestones’ found themselves covering 100 per cent of the air wing’s aerial refuelling needs, so therefore practically every Intruder that launched carried a buddy store for tanking. The reality of the arrangement was demonstrated by an incident while heading west across the Pacific, as a B/N from VA-196 explained;

‘Early in cruise we were in the “Bear Box” off Guam, this being the area in the mid-Pacific where you usually encountered Soviet Tu-95 “Bears” coming out of Siberia to find the carrier. The Russians had sent a pair of them out to look for us and we’d spent the entire day tanking Tomcats and Hornets, which were escorting them while in the area. Then the sun set and VA-196 was scheduled to fly several events to drop Mk 76 practice bombs at night on targets in the Marianas. We launched several aircraft and then, without warning, were ordered to return to the carrier as tankers because the word had gone out that the Russians were back in the area.

‘The ship launched CAP and we re-set the fighter grid as they sorted things out. NOBODY had ever heard of the Soviets having recon in this part of the ocean after dark – their goal was, after all, to observe and shoot photos of the carriers. We did as we were told, passed gas and stooged around in the dark for a while, before being told to come home with no other activity. It turned out some knucklehead in the VAQ squadron saw what he thought was Tu-22 “Blinder” – an aircraft NEVER seen out this far – radar activity that turned out to actually be a search radar on one of our cruisers. The entire force had practically gone to GQ [General Quarters] over it.’

Nonetheless, the ‘Milestones’ went on to have an excellent cruise, which ended in August 1985.

The Intruder found its way onto the big screen in two notable motion pictures during its final years in service. In 1979, VA-35 had a bit part in the 1980-release The Final Countdown – a science fiction film where Nimitz went through a weather anomaly and ended up off Hawaii on 6 December 1941. The ‘Black Panther’ role was largely kept to tanking VF-84 F-14As. In 1991, The Flight of the Intruder debuted, this being the film version of former VA-196 pilot Steven Coonts’ novel about Vietnam. For this effort the US Navy used VA-165 aircraft re-marked as ‘Milestones’, with most of the filming being done on Independence and over Hawaii.

LIBYA 1986

If the 1970s had started calmly in the Mediterranean for US forces, this rapidly changed as the decade progressed due to recurring, and escalating, stages of warfare between Israel and its Arab neighbours, as well as the emergence of a number of non-state terrorist groups. In Libya, Col Muammar Gaddafi had seized control via a coup in 1969, and over time he established a revolutionary government hostile to the west and the United States in particular. His actions would lead to several years of conflict with neighbours and two significant operations involving A-6s.

In 1974 Gaddafi declared that the Gulf of Sidra, the portion of the Mediterranean south of the 32o 30’ North latitude, was sovereign Libyan water and therefore off-limits to all other shipping. The US government refused to accept the claim and the Sixth Fleet became the obvious tool to dispute the issue. The US Navy responded by what was described as ‘Freedom of Navigation Operations’, or FONOPs, where ships and aircraft would routinely operate in the disputed waters. Libya’s answer was initially muted, and it would take seven years before things really heated up.

In August 1981 F-14As flying from Nimitz downed two Libyan Su-22 ‘Fitters’ that had attempted to engage them over the Gulf of Sidra. Libya’s apparent response to what it viewed as US aggression was to support a series of terrorist attacks in Lebanon and Europe by surrogate groups. By January 1986 President Reagan had declared Libya to be an ‘unusual and extraordinary’ threat to the United States that had to be dealt with. Sixth Fleet now consisted of two carrier battle groups, USS Saratoga (CV-60) (CVW-17/VA-85) having just returned from the ‘IO’, and Coral Sea (CVW-13/VA-55), which had been on station for several weeks. Back in Norfolk, America (CVW-1/VA-34) was preparing for a March departure to join them.

The flightdeck of Saratoga in February 1986 while conducting FONOPs off the coast of Libya. CVW-17 aircraft include VA-85 Intruders, A-7Es from VA-81 and -83, F-14s from VF-74 and -103 and a single S-3A from VS-30. The nose of a VQ-2 Det EA-3B peeks out from the right. The first Intruder, A-6E AA 501 BuNo 161685, carries a SUCAP load of Rockeyes, while the squadronmate behind it is KA-6D AA 521 BuNo 152611 (US Navy)

Operation Attain Document, a large FONOP, began on 15 January. Libya placed its forces on ‘full alert’ and declared that America was ‘practising state terrorism against a small, peaceful country’. Fighter aircraft from both sides jousted over the Gulf of Sidra but there were no shots exchanged this time. A month later, on 12 February, Sixth Fleet returned for Attain Document II, its vessels sailing across what was now being referred to as ‘The Line of Death’ due to Gaddafi’s frequently dire statements. Through it all the two Intruder squadrons present conducted surface search and tanker support for both air wings. Attain Document III, which began on 24 March, now included the recently arrived America, increasing Sixth Fleet’s strength to 26 warships and 250 aircraft, many of which were now operating well into the Gulf of Sidra in what was clearly viewed as a provocative act by Libya.

Shooting started at 1452 hrs on the 24th when Libyan SA-5 missile batteries at Sirte launched SAMs at orbiting Tomcats. The US Navy responded with radar jamming and HARM shots. This pre-planned action, now referred to as Operation Prairie Fire, continued until evening when, at 2100 hrs, an E-2C picked up a single Libyan patrol boat headed north towards the three carrier battle groups. The vessel, the 250-ton French-built La Combattante II-class missile craft Waheed, was engaged by VA-34 Intruders, which fired Harpoon missiles for the first time in combat. A section of VA-85 aircraft followed up with Mk 20 ‘Rockeye’ cluster bombs, which finished off the vessel.

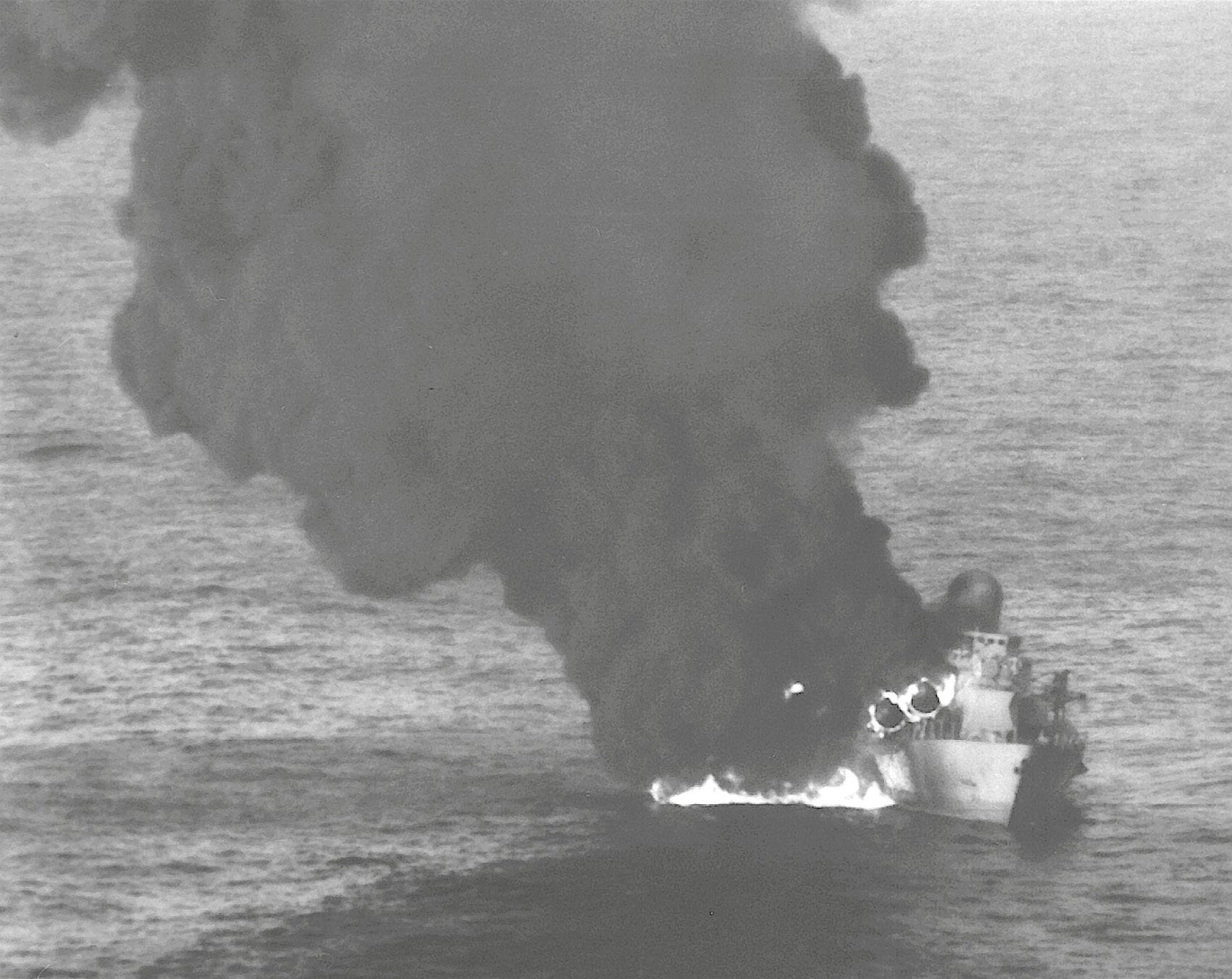

This widely distributed picture shows a Libyan Nanuchka-class corvette burning furiously after being hit by a Harpoon fired by a VA-85 Intruder during Operation Prairie Fire. It would eventually sink (US Navy)

While the Libyans continued to shoot the odd SAM at US Navy aircraft (none of which connected), at 2335 hrs a 560-ton Libyan Nanuchka-class corvette was engaged by Rockeye-dropping ‘Black Falcons’, which held their Harpoons back due to friendly surface traffic in the area. The heavily damaged warship was able to limp back into port. Finally, on the morning of the 25th, another of the Soviet-built Nanuchkas was attacked, this time by VA-55 aircraft off Coral Sea. The vessel took a pattern of CBU-59 Anti-Personnel/Anti-Material bombs and then a Harpoon ‘chaser’ from a VA-85 A-6E. The corvette, burning furiously, eventually sank.

The identities of the two Libyan corvettes have been confused ever since. Official US Navy documentation says the first ship was the Ain Zaquit and the second vessel – the one sunk – the Ain Mara. The authoritative Jane’s Group, however, states that the two names are reversed, and that Ain Mara was the first ship attacked and would subsequently travel to the USSR for repairs and eventually return to Libya in 1991 as the Tariq ibn Ziyad.

It was at about this point that both sides backed off and separated to catch their breath. Saratoga departed for home and the remaining two carriers went back to routine business. The apparent bloody nose his forces had received did not stop Gaddafi’s rhetoric, however, and he vowed to (paraphrase) ‘continue the struggle until victory’. On 5 April a nightspot in Berlin was bombed, killing two American servicemen. Libya was immediately implicated and the stage was set for the next action.

VA-34 ‘Blue Blasters’ figured predominantly in Operation El Dorado Canyon, hitting targets in Benghazi, Libya. Here a section of ‘Blaster’ A-6E TRAMs fly over the Fallon range in May 1987. At this point they were marked for CVW-7 and an upcoming Mediterranean cruise on board Eisenhower (Bob Lawson)

Ten days later US forces launched coordinated strikes into Libya itself. Referred to as Operation El Dorado Canyon, the event would involve Intruders from both remaining carriers and USAF F-111Fs flying out of Lakenheath, in Suffolk (see Osprey Combat Aircraft 102 – F-111 and EF-111 Units in Combat for further details). Targets would be in Tripoli and Benghazi. VA-34 would strike the al-Jamahiriya military barracks in downtown Benghazi while the ‘War Horses’ went after Benina airfield on the outskirts of Tripoli. The USAF’s goal was Tripoli airfield and specific political locations in the city itself. Backing up those going over the beach would be a huge array of support aircraft performing defence suppression, MiG CAP, tanking and command and control.

With the UK-based F-111s having already been airborne for several hours, America began to launch aircraft at 0045 hrs on 15 April – six ‘Blue Blasters’ and an equal number of A-7Es (armed with AGM-45 Shrike or AGM-88 HARM) made up the strike group. While the Corsair IIs would remain over water keeping the Libyan air defence force’s heads down (they were ably assisted in this role by the EA-6Bs of VMAQ-2 Det Y, which was also part of CVW-1), the ‘Blasters’ would go over the beach. Among the NFOs serving with VA-34 on this deployment was Lt(jg) Joe Weston, a young B/N who had graduated from the University of Florida in 1981. He then entered VT-86 and wanted to be an A-6 B/N from the very start. He joined VA-34 just prior to cruise;

‘We were loaded with talent – our CO was Cdr Rich “Cool Breeze” Coleman, who’d flown combat with VA-35 in Vietnam in 1972. We also had, unknown to us at that time of course, four future Admirals in the ready room, namely Lou Crenshaw, Joe Kuzmik, Dee Mewbourne and “T C” Cropper. We went right into FONOPs on arrival in the Med, and planned for a number of potential targets in Libya. We weren’t actually told our final targets until the day of the strike, as higher authority split things up between the Navy and Air Force F-111s coming out of England.

‘VA-34 got the Jamahiriya barracks in downtown Benghazi. My pilot was Lt Steve Sullivan, and we were No 4 of six being launched. Our plan was to go as a “bomber stream” with six aircraft following each other at low altitude. Once we got back we realised that there was probably a better way to do this as we’d actually increased our predictability from the ground.’

Coral Sea ended its remarkable career deploying with the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean, the veteran carrier having a ‘front-row seat’ for operations off Libya in 1986. The vessel is seen here underway with CVW-13 embarked, apparently in late 1985 before the air wing was joined by five Prowlers from VAQ-135. At least 11 VA-55 ‘War Horse’ Intruders can be seen in this view (US Navy)

Nevertheless, their plan worked well that night.

‘We carried out a covey launch [rapidly shooting the division off from all four catapults], hit the tanker and proceeded to the target at 100-200 ft. This is what we’d trained for – low-altitude night penetration. I was in the radar boot most of the flight, only occasionally looking out. We had a load of 16 Mk 82 Snakeyes on board and a centreline tank, and we were supposed to be doing 450 knots. At some point I came out of the boot and saw that we were doing only 430. I asked “Sully” if the throttles were at military. He responded with something to the effect that they’d been at the stops since the tanker, and that was all the aircraft would do that night.

‘We had both Shrike and HARM shooters supporting us from VA-72 and VA-46, respectively, as well as Marine EA-6Bs from VMAQ-2. The actual time over the beach went well, with everyone dropping their weapons and making it back to the water. AAA wasn’t that heavy, and although we saw a couple of SAMs, they didn’t seem to be guiding. Once over the water we started climbing and the F-14s deloused us. That was about it.’

Joe Weston made two cruises with VA-34 and later flew with test and evaluation unit VX-5 from Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, in California, before leaving the US Navy.

All six of the ‘Blasters’ involved were able to drop their bombs, officially damaging the barracks as well as a MiG parts warehouse located nearby. They safely returned to the carrier.

Over on Coral Sea, by now dubbed the ‘Ageless Warrior’, eight VA-55 Intruders were catapulted into the night along with F/A-18A HARM shooters and VAQ-135 Prowlers.

Representative of the legion of men who kept the Intruder airborne was Charles ‘Chuck’ Berlemann, who spent almost his entire career in the A-6 community. Hailing from Collinsville, Illinois, he had enlisted in the US Navy in 1966 and opted for the Aviation Fire Control Technician rate. He was an early member of VAH-123’s A-6 department and moved to new Intruder RAG VA-128 when it was formed. After a couple of years out of the US Navy, Berlemann returned and joined the ‘Boomers’ of VA-165 at Whidbey – he stayed with the unit for six years, rising to Chief Petty Officer along the way. Berlemann subsequently served on the staff of the Whidbey wing, where he was heavily involved in the introduction of TRAM to the local A-6 squadrons. From there he transferred to Oceana for another sea tour, now with VA-34, and then helped establish VA-55 in 1983 as a Warrant Officer (WO).

VA-55 ‘War Horse’ A-6E AK 501 BuNo 159317 recovers aboard Coral Sea in an official photograph taken on 22 March 1986 while the carrier was operating off Libya. The aircraft carries a SUCAP load consisting of a Harpoon and two Rockeyes, as well as an AIM-9 for self-defence, an empty MER on station five and a centreline fuel tank. This combination was light enough for the jet to land back onboard the carrier without the crew having to jettison any ordnance in order to get down to recovery weight (US Navy)

‘I loved the Navy,’ Berlemann said. ‘I felt like I was part of a professional sports team, and that what I did really mattered. The night prior to the Libya strikes the skipper asked me to talk to the enlisted men in the shops and tell them that what they did mattered. We already had a reputation for having well prepared jets, and the aircraft that went over the target hit everything they aimed at. When we heard that all of our aircraft were feet wet after bombing Libya we were ecstatic.’

Chuck Berlemann retired as a WO3 in 1990.

While the men who flew the aircraft frequently got the most notice, working in the background were shops full of sailors who kept the Intruder’s complex systems ‘up’ and ready for flight. Frequently toiling in terrible conditions with variable parts support, the maintainers rarely got the credit they deserved for their part in making squadron operations successful. As was frequently stated, only half tongue-in-cheek, in reference to aircrew, ‘It takes a College education to break an Intruder and a High School education to fix it.’

For the ‘War Horses’, the results of their night’s work was a heavily cratered runway and the destruction or damage of multiple aircraft located on the tarmac, including several MiG-23 ‘Floggers’. The USAF F-111Fs hit their targets as well, and benefiting from a much better video recording system than the Intruder carried, had their FLIR imagery featured on news reports worldwide – a point noted by the US Navy. One F-111 was lost with its crew, while the remaining aircraft returned to England (with one diverting into Spain) after an impressive 15-hour combat flight.

While the US Navy quickly stated that El Dorado Canyon had achieved its limited objectives, the US State Department would later say that Gaddafi continued his sponsorship of international terrorism – a view that was supported by the destruction of a Pan Am Airlines Boeing 747 over Scotland on 21 December 1988. The violent loss of a French airliner over Chad the following year was also traced to Libyan agents. Nonetheless, the US government still asserted that ‘the United States had not only the means but the will to deal effectively with international terrorism’.

PRAYING MANTIS

While Sixth Fleet stood off Libya, other carriers continued making long deployments to the Indian Ocean to monitor Iran. Practically every Seventh Fleet carrier made a swing through the ‘IO’ between 1980 and 1990, with Atlantic Fleet ships reporting as well, frequently after a transit around the southern end of Africa. These cruises were typically long and monotonous for crews, with few liberty ports to break things up. Logistical support remained a challenge as things like fresh produce and milk would frequently run out while underway. Meanwhile, the US Navy continued to develop Diego Garcia as a forward support base and work with friendly local governments – generally those threatened by Iran – for improved facility access.

Tensions had been on an edge in the Persian Gulf region since the start of the Iran–Iraq War in September 1980. The eight-year conflict was noted for each side killing large numbers of its opponents, while the Western powers (and the United States in particular) tried to keep the Strait of Hormuz and Persian Gulf open for tanker traffic. By 1987 Iran was openly laying mines throughout the gulf, which resulted in several skirmishes between US and Iranian Revolutionary Guard (IRG) units. On 14 April 1988 the frigate USS Samuel B Roberts (FFG-58) hit an Iranian mine and was heavily damaged. Four days later the US Navy initiated Operation Praying Mantis as a response to Iranian actions. Centrepiece to this action would be the Enterprise battle group. The ‘Big E’ had left Alameda on 5 January with CVW-11/VA-95 on board, and it would eventually be positioned south of the Strait of Hormuz in the Gulf of Oman.

VA-95 participated in Operation Praying Mantis from Enterprise in April 1988. ‘Green Lizard’ A-6E NH 502 BuNo 152925 carries Mk 82 Snakeyes with steel nose plugs in this photograph. Note the ever present NATOPS pocket checklist in the B/N’s windscreen quarterpanel (US Navy)

At dawn on 18 April Praying Mantis kicked off with US warships and Marines seizing northern gulf oil platforms from which attacks were being launched against friendly shipping. The response by a single Iranian Navy patrol boat rapidly led to its demise by missiles launched by US naval ships.

CVW-11, meanwhile, had put up SUrface CAP (SUCAP) from sunrise, with A-6s and A-7Es ranging into the gulf to find and sink any Iranian warships that might be present. Cdr Bill Miller’s ‘Green Lizard’ jets were loaded with a mix of weapons to deal with almost any situation, including Harpoon and Skipper missiles, LGBs and Rockeye cluster bombs. Corsairs from stablemates VA-22 and -94 carried Walleye and Rockeye, among other weapons. Meanwhile, F-14s from VF-114 and -213 provided CAP in case of possible visits by Iranian F-4s out of Bandar Abbas and VAQ-135 EA-6Bs monitored the electronic domain for activity.

High on the list of potential targets was one of Iran’s Saam-class frigates, Sabalan, which had become noted for having a captain who mocked ships he was attacking over the radio. There were four of the class in the Iranian fleet, all of them 1200 tonners built by Vosper Thornycroft in Britain in the late 1960s.

Things kicked off for the ‘Lizards’ when a section was directed onto a group of Boghammers (Swedish-built small speed boats used by the IRG for fast attack within the gulf) near Abu Musa Island by an E-2C. The Intruder crews found their quarry and rolled in with Rockeye. As one B/N later put it, ‘someone had noted that they ALWAYS turned left to avoid bombs, so the gouge was to drop a little long and left’. The lead Boghammer did as advertised and was raked by the cluster weapons, causing the crews of the remaining four to lose their ardour and quickly return to Abu Musa.

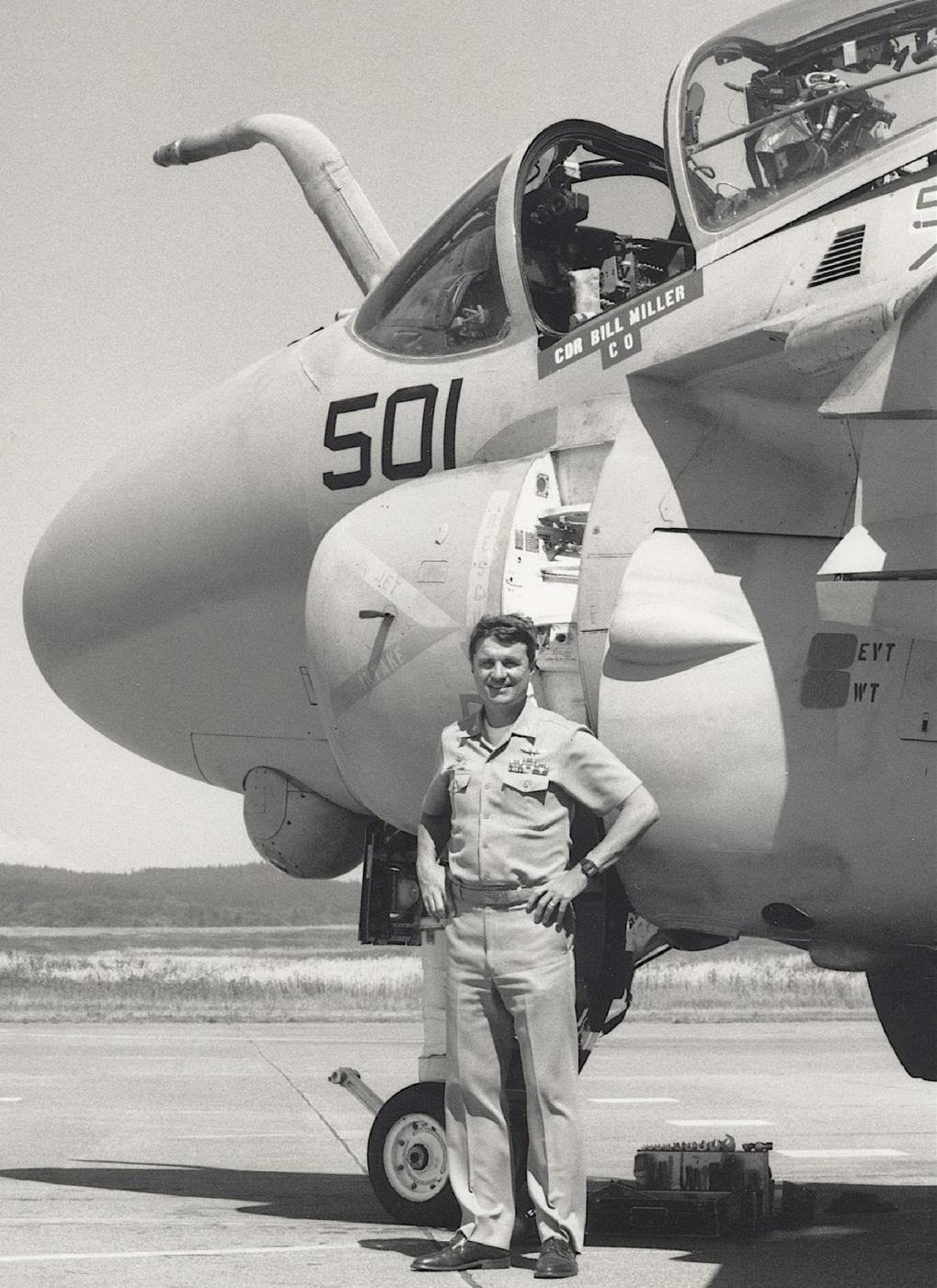

VA-95’s CO for its WestPAC, ‘IO’ and Arabian Gulf cruise on board CVN-65 in 1988 was Cdr Bill Miller, who is seen here with his aircraft at Whidbey Island in July of that year shortly after returning from the deployment. He and his B/N, Lt Cdr Joe Nortz, hit Sabalan when it ventured into the Arabian Gulf from Bandar Abbas harbour after Sahand had been attacked. The frigate was left dead in the water after Nortz guided a 500-lb LGB ‘right down the stack’ (Tony Holmes)

By mid-afternoon it became known that Iranian naval units were getting underway from Bandar Abbas. CVW-11 aircraft were directed to proceed and investigate, with the lead Intruder (NH 500 BuNo 156995) being crewed by the Deputy CAG, Capt Bud Langston (former CO of VA-145), and ‘Lizard’ junior officer B/N ‘Pappy’. The B/N quickly stated that he had a lot of radar returns that he started sorting through his FLIR. When he found one to be a probable warship Langston took the Intruder down to the deck while ‘Pappy’ made several calls on Guard frequency warning any Iranian units in the area that they were sailing into danger. Their first pass was ‘on the deck, over 500 knots and right down the ship’s port side’. It was at this point that ‘Pappy’ realised that his pilot had put the Iranian on his side of the aircraft in case they took fire. Flashes appeared from the bridge and stern – possible infrared-guided SAMs had been launched at them.

Their Rules of Engagement (they had to be fired on first before they could in turn return fire) having been met, Langston wheeled the Intruder away from the Iranian ship, dropping flares as he climbed rapidly to about 8000 ft. While he and his B/N knew the ship was one of the Iranians’ four Saam-class vessels, they were still unsure if it was the one they were really looking for. The ship turned out to be Sabalan’s sister-ship Sahand – not that it mattered at this point.

On their first pass Langston and ‘Pappy’ expended a 500-lb LGB in a 40-degree dive, the weapon impacting just off the port bow. Although it missed the ship, the bomb undoubtedly caused serious hull damage. Their next launch was their Harpoon, which was fired at a range of 15 miles and guided amidships, where it went off ‘high-order’. They then fired both of their AGM-123 Skipper IIs, with the B/N placing his laser spot ‘on the only part of the ship that wasn’t burning’, which was just forward of the bridge. The first one hit squarely on target, while the second one, apparently confused by the copious amounts of smoke being generated by the now burning wreck, missed. NH 500 then returned to Enterprise while other air wing aircraft arrived to deliver the coup de grâce, along with a single Harpoon fired by the veteran Charles F Adams-class destroyer USS Joseph Strauss (DDG-16).

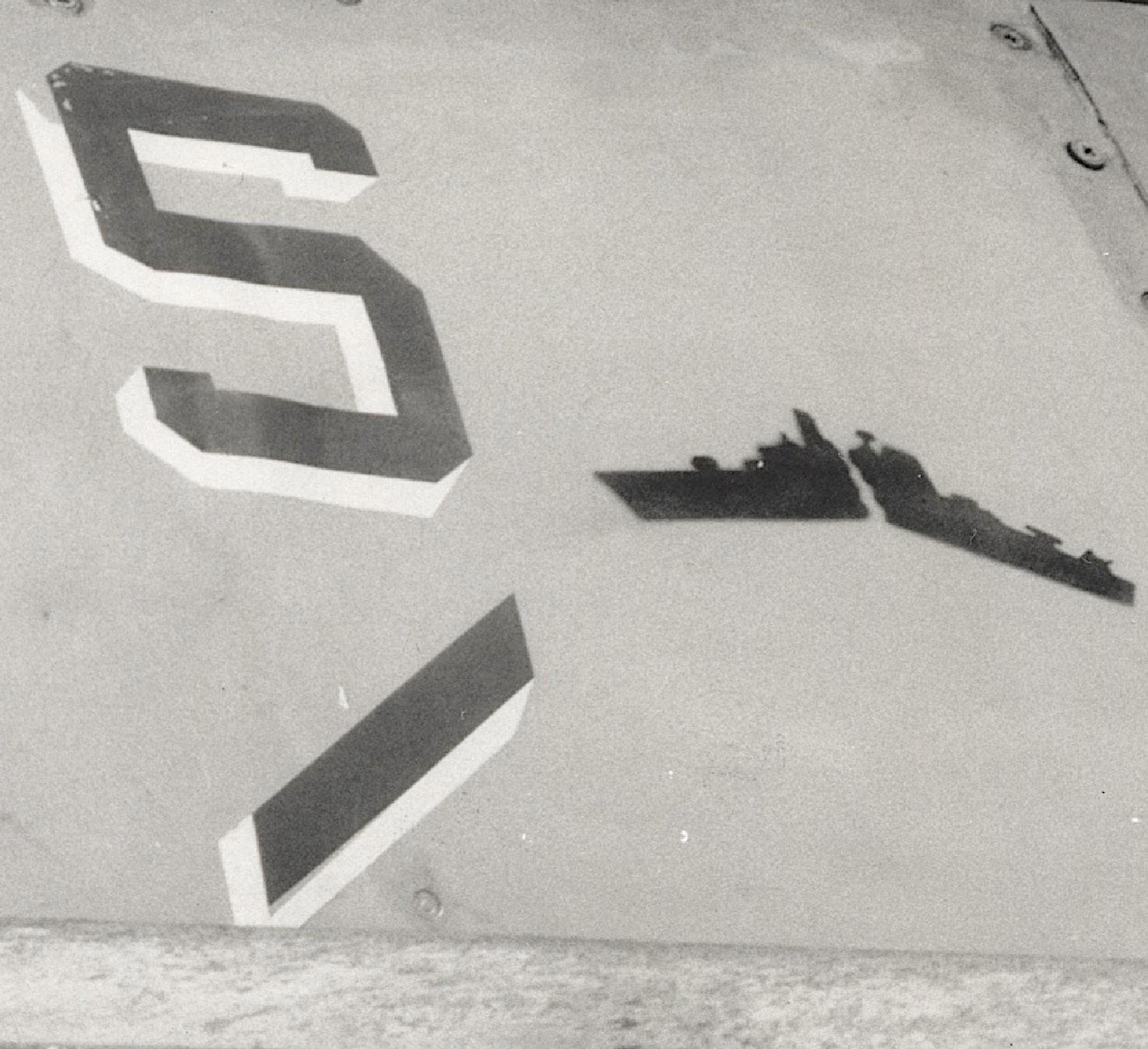

The shattered remains of the Iranian Saam-class frigate Sahand were photographed by a US Navy aircraft shortly after the vessel had been engaged by VA-95 on 18 April 1988. Built for the Shah’s navy by Vosper Thornycroft in Britain in the late 1960s, Sahand was pounded by various ordnance during the one-sided clash that resulted in the frigate being sunk. While Intruder units trained to take on vessels up to the 24,000-ton Soviet Kirov-class battlecruisers, the 1200-ton Sahand would be the largest warship the type ever sunk – VA-95 also crippled its sister-ship, Sabalan (US Navy)

While this was going on another Saam-class frigate was reported to be departing Bandar Abbas, and aircraft were despatched to investigate. This vessel turned out to be the high-interest Sabalan, and it was quickly hit by a ‘Lizard’-delivered 500-lb LGB ‘right down the stack’, which left it dead in the water. The ship attempted to defend itself by firing several infrared-guided SAMs, none of which connected. Additional aircraft were en route to sink the frigate when a ‘knock it off’ call came from the Pentagon, the point having been proven. Sabalan was towed back into port and Enterprise continued to monitor things in the gulf.

Praying Mantis was widely viewed within the US Navy as how to do business, being seen as a measure of vindication for warfighting improvements after the disastrous Lebanon raid. What nobody realised at this point of course was how busy the US Navy, and Intruders, would be in this area only two years later.

IMPROVEMENTS AND DEAD ENDS

Aircraft carriers had continued to deploy with Intruders on board through to the end of the 1980s. While air wings were rapidly replacing their Corsair IIs with Hornets, the A-6 community had introduced the System Weapons Improvement Program (SWIP) version of the TRAM aircraft. SWIP added digital enhancements that allowed the jet to employ new weapons, including AGM-65 Maverick, AGM-88 HARM and AGM-84E Stand-Off Land Attack Missile (SLAM), as well as the ALR-67 and ALQ-126B self-defence EW systems. Introduced in 1988, SWIP would be the final major modification to the Intruder series that would reach the fleet.

VA-95’s NH 500 BuNo 156995 was adorned with this modest Sahand victory silhouette near the ‘Safety S’ that was applied to all ‘Green Lizards’ jets at this time. This aeroplane was responsible for inflicting most of the damage on Sahand (Tony Holmes)

SWIP was developed parallel to plans to buy new wings for the Intruder, with the goal that they be made using modern carbon-fibre materials – routinely, if not quite correctly, called ‘plastic’ wings in the fleet. It was no secret in the Medium Attack community that after years of combat and high-G pull-outs, there was an issue with metal fatigue and brittleness in many of the A-6s. The loss of wings in several aircraft while dive-bombing only reinforced the seriousness of the situation. Boeing-Wichita got the contract for the new structures and immediately ran into production problems that meant the initial SWIPs would retain their original spans. The first Boeing-modified aircraft would fly in April 1989, and the new ‘plastic wings’ would soon flow to the fleet.

The final version of the A-6E to enter service was the SWIP, which introduced a number of system and weapon advances to the Intruder. Slightly delayed were new carbon-fibre wing sections built by Boeing in its Wichita plant in Kansas. BuNo 155682 was the first test aircraft to fly with the new wings, and it is seen here with test equipment installed during a flight over the Kansas countryside in April 1989. It also shows one of the primary visual differences for the SWIP – the two rear-looking antennas associated with the ALR-67 self-defence EW system extending from the wing trailing edge (US Navy)

Other tactical improvements entered the fleet throughout this period, including Night Vision Goggles (NVGs), also called Night Vision Devices (NVDs),which greatly enhanced crew situational awareness in the dark. The use of NVGs required a significant amount of crew training, as well as modifications to the cockpit lighting, but the move proved to be a good one. VA-65 became the first fully NVG-qualified squadron in September 1986.

Physical enhancements to the airframe were also being pursued. Grumman had long proposed a new version of the Intruder, designated the A-6F, which would include new General Electric F404 turbofan engines in place of the venerable J52 turbojets, as well as a fully digital weapons system, new cockpit displays and two additional wing stations. The first contract for the A-6F was let in Fiscal Year 1984, with up to 150 new aircraft promised by the end of the decade, as well as an aggressive E-model rebuild programme. The first A-6F flew in August 1987 and a second was delivered before the entire programme was cancelled as part of the Fiscal Year 1988 budget. The point was made that John Lehman, the aircraft’s primary sponsor, was no longer SECNAV, and that ‘there’s something better coming’ in the form of a very highly classified programme called the Advanced Tactical Aircraft (ATA). With only five airframes built, the A-6F got the chop in favour of ATA.

Attempts by the Intruder desk to move at least some A-6F capability into existing airframes quickly led to the proposed A-6G, which, among other system enhancements, would have put the Prowler’s J52-P-408 motors in the airframe. It too had died by 1990.

While these fights were going on inside the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and at NAVAIRSYSCOM, war clouds were again brewing in the Middle East, and the Intruder would be called on once more to go into the breach.