THE INNER CIRCLE

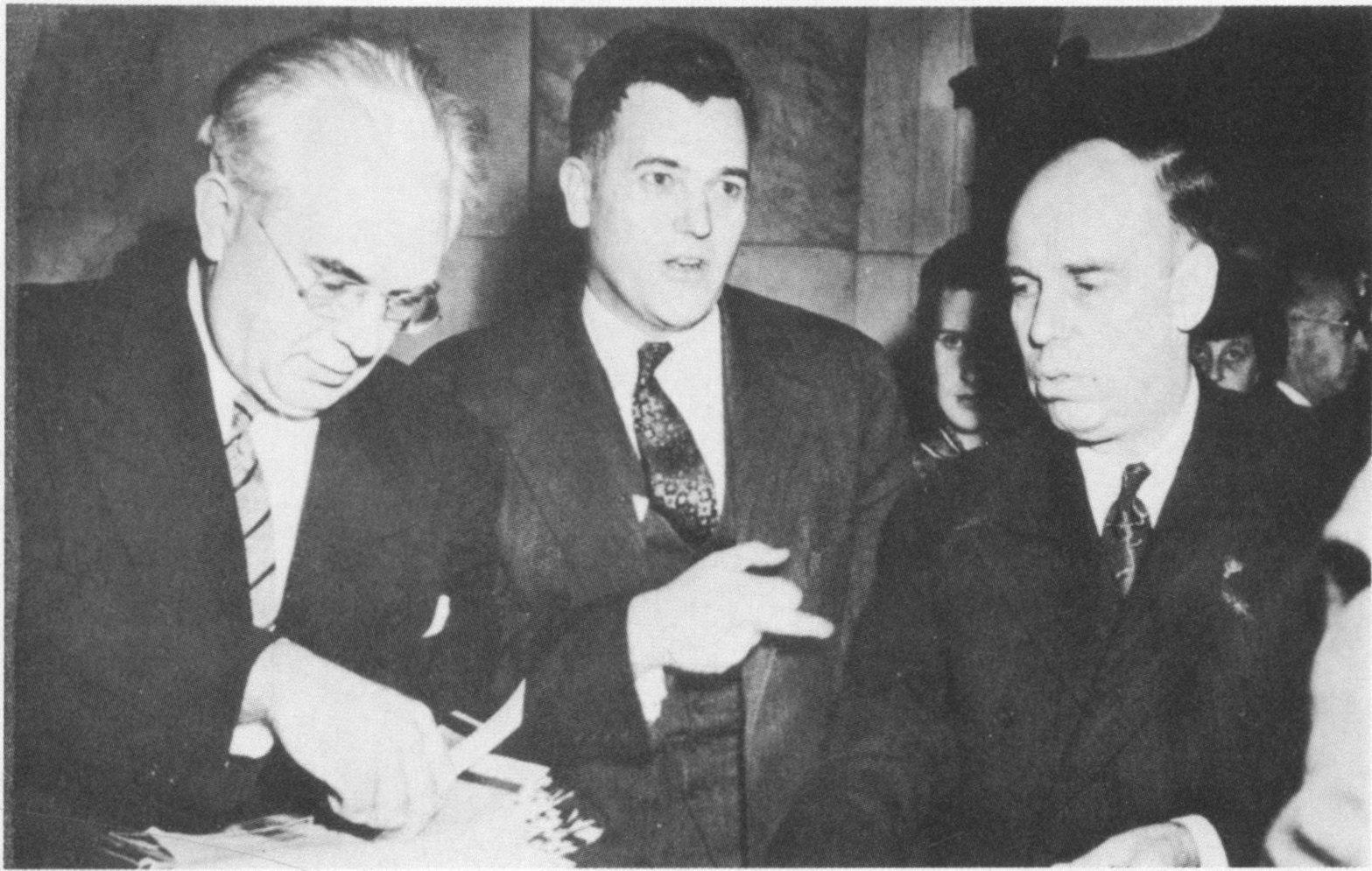

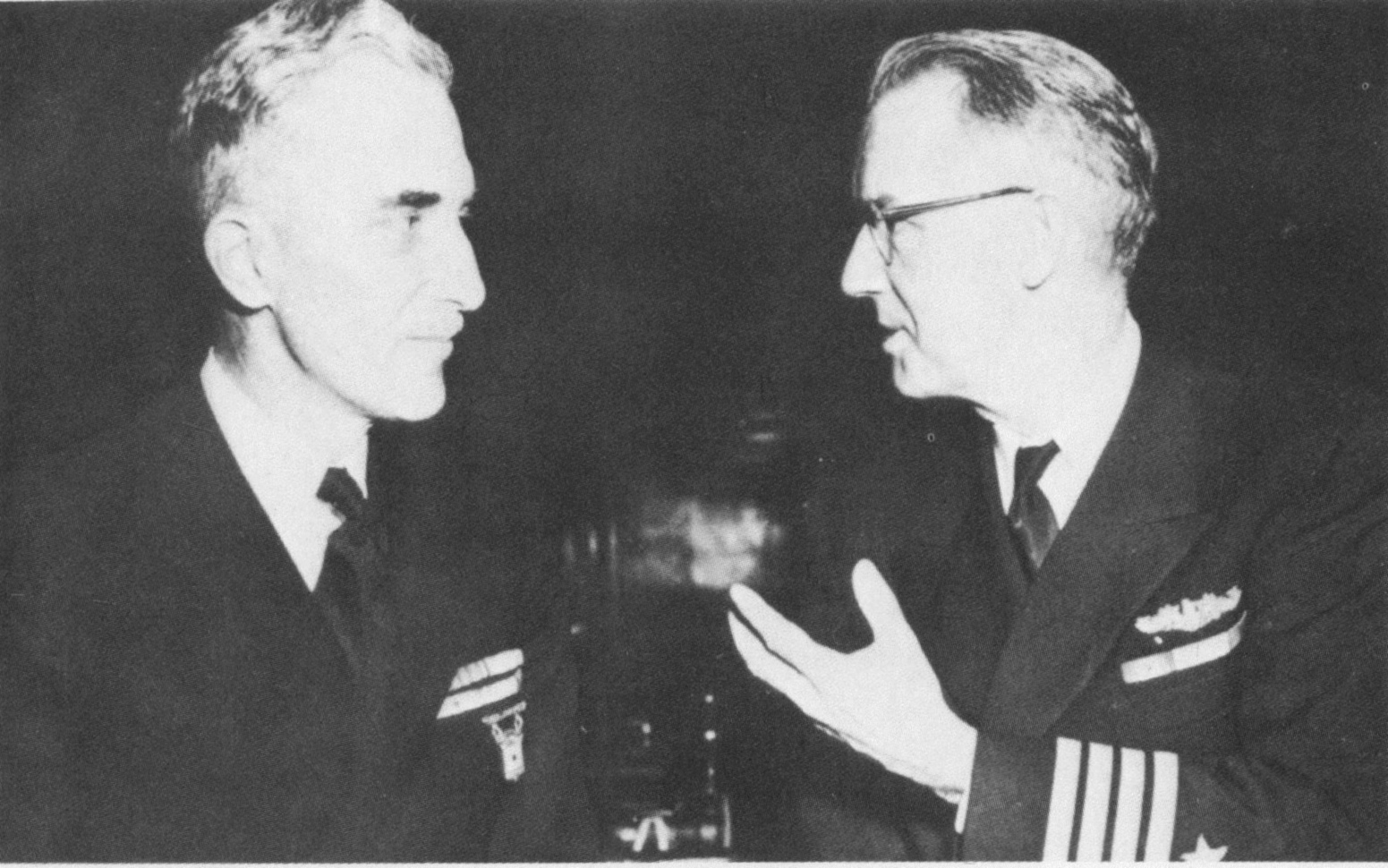

Admiral J. O. Richardson (extreme right), commander of the U. S. Pacific Fleet. He is forcefully protesting to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox on October 10, 1940, that continued basing of the fleet at Pearl Harbor is not a deterrent but an incitement to Japanese aggression in the Pacific. Roosevelt disagrees, and Richardson is replaced by Admiral Husband Kimmel. To Knox’s right, Admirals Harry Yarnell (left) and Harold Stark. (Naval History)

The Atlantic Charter is signed, August 1941, aboard the British battleship Prince of Wales. Roosevelt and his advisers also agree to join Britain in preventing “further encroachment by Japan in the southwest Pacific” even though such measures “might lead to war.” Left to right: General George Marshall, Army Chief of Staff; Franklin Roosevelt; Winston Churchill; Admiral Ernest King, commander of the Atlantic Fleet, and Admiral Stark, Chief of Naval Operations. (National Archives)

Cordell Hull, Secretary of State. Hull, Stimson, Knox, Marshall and Stark constituted Roosevelt’s War Cabinet. (National Archives)

Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War. (National Archives)

Harry L. Hopkins, the President’s close friend and adviser. (National Archives)

BEFORE THE ATTACK

Admiral Kimmel, commander of the Pacific Fleet in 1941, conferring with his chief of staff, Captain William Smith, right, and his operations officer, Captain W. S. DeLany. (Naval History)

By early December 1941 Kimmel has raised the Pacific Fleet to battle efficiency. (Naval History)

Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, commander of the U. S. Army ground and air forces in Hawaii. (National Archives)

Aerial view of Pearl Harbor from the north, showing the Pacific Fleet clustered near Ford Island. Battleship Row is on the east side of the island. Ensign Takeo Yoshikawa, the lone Japanese naval spy in Hawaii, posing as a consular employee, took similar pictures from a sightseeing plane. (National Archives)

THE ATTACK

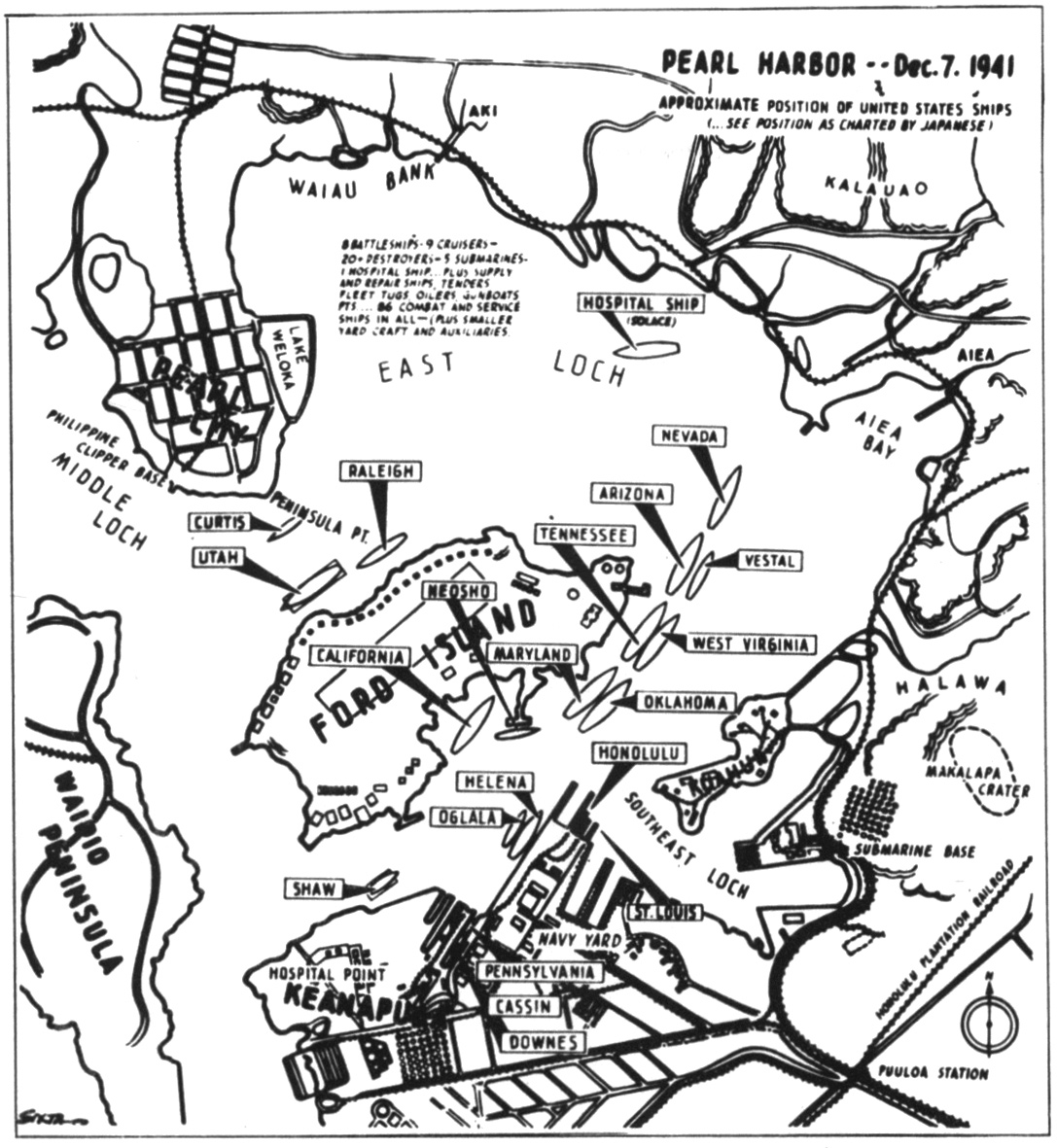

Chart of Pearl Harbor as it was on the morning of December 7, 1941. (National Archives)

Japanese planes begin taking off from six carriers at 6 A.M. (National Archives)

Through Japanese Eyes

(Pictures, sketches, diagrams and translated captions as published in Japan) (National Archives, Suitland)

Karl Boyer, radioman at the Wailupe naval radio station near Pearl Harbor. At 7:58 A.M., Hawaiian time, he tapped out the signal heard around the world: AIR RAID ON PEARL HARBOR. THIS IS NO DRILL. (Karl Boyer)

Lieutenant Earl Gallaher, pilot of a scout bomber from the carrier Enterprise, approached Pearl Harbor during the attack. He reported that the Japanese were returning on a northwesterly course. But conflicting information sent the U.S. search to the south. At the Battle of Midway, Gallaher’s bomb hit among the parked planes on the carrier kaga. As he saw his bomb explode he thought, “Arizona, I remember you!” Later in the day he led the bombers that sank a second carrier, Hiryu. (Rear Admiral Earl Gallaher)

Admiral Kimmel watched the attack from the second floor of the submarine base. A spent Japanese bullet came through an open window and struck Kimmel in the chest. “I wish it had killed me,” he said. (Naval History)

Through American Eyes. (U. S. Navy)

AFTER THE ATTACK

The Arizona, sunk and still burning, but with her flag flying. Nearly half of the 2,403 killed on December 7 were lost on this battleship. (National Archives)

“Yesterday,” Roosevelt tells Congress, “December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked.…” (National Archives)

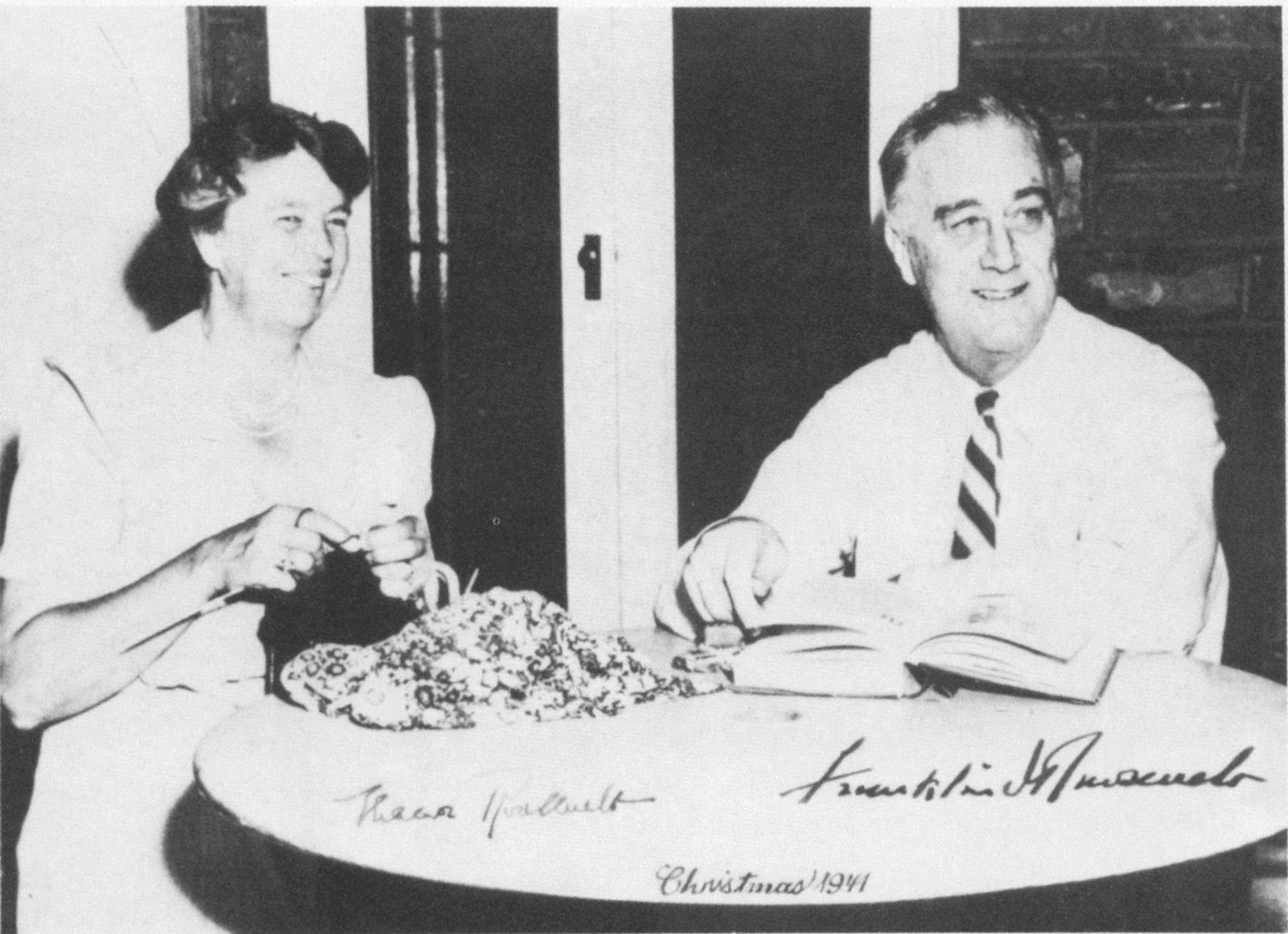

The Roosevelts’ Christmas card to friends. (Rear Admiral Lester Robert Schulz)

Admiral Chester Nimitz relieves Kimmel as commander of the Pacific Fleet twenty-four days after the attack. (Naval History)

Knox visits the new commander at Pearl Harbor. (Naval History)

MUTINY ON THE SECOND DECK

The Navy Building on Constitution Avenue, Washington, D.C. Here, on the second floor, took place the “mutiny” of October 1941.

Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, brilliant Chief of War Plans, nicknamed “Terrible Turner,” for his sulfuric temper. He refused the request of Captain Alan Kirk to send warning of possible attack on Pearl Harbor to Kimmel. Kirk was “detached” from his position as head of Navy Intelligence. (National Archives)

Rear Admiral Theodore “Ping” Wilkinson, Kirk’s replacement, was also bullied by Turner. This picture was taken in Japanese waters on September 21, 1945. He met a tragic death soon after testifying at the congressional investigation of Pearl Harbor when his car plunged off a ferry. (National Archives)

Commander (later Captain) Laurance Safford, one of the subordinates on the second deck who persisted in trying to send warnings of Pearl Harbor to Kimmel. A talented cryptoanalyst, he later risked his reputation and career to prove that Kimmel was innocent of responsibility for the Pearl Harbor debacle. (Commander Charles C. Hiles)

Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes, Chief of Navy Communications, also feuded with Turner. (National Archives)

Commander Charles C. Hiles, one of Safford’s closest postwar friends and confidants. Their voluminous correspondence, available at the Archive of Contemporary History, University of Wyoming, is an invaluable source for researchers. (Mrs. Charles C. Hiles)

William Friedman, a close friend of Safford’s and leader of the talented team of codebreakers that solved the Japanese Purple code. (George C. Marshall Research Foundation)

The machine constructed to break the Purple Code. (National Archives)

THE PEARL HARBOR INVESTIGATION, 1941-44

The Roberts Commission placed the burden of blame for Pearl Harbor on Kimmel and Short. Left to right: Major General Frank McCoy, Admiral William Standley, Associate Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts, Rear Admiral Joseph Reeves and Brigadier General Joseph McNarney. Standley, the highest-ranking officer on the commission, later felt he had been grossly betrayed by Roberts and called his performance as head of the commission “as crooked as a snake.” (Wide World)

Kimmel selected retired Navy Captain Robert Lavender as assistant defense counsel in his efforts to clear himself. Lavender, second from left, is shown as a member of the crew of one of three Navy planes involved in the historic transatlantic flight of 1919. (Naval History)

Admiral William Halsey, one of the many high-ranking defenders of Kimmel. He wrote Kimmel, “As you know I have always thought and have not hesitated to say on any and all occasions, that I believe you and Short were the greatest military martyrs this country has ever produced, and that your treatment was outrageous.” (National Archives)

Charles Rugg of Boston, the chief defense counsel for Kimmel. (Edward Hanify)

In early 1944 Admiral Thomas Hart began a one-man investigation. His principal witness was Captain Safford, who revealed that early in December 1941 he had seen the intercept of the Japanese “East wind, rain” message which meant that Japan was about to wage war on America. (David Richmond)

That July the three members of the Navy Inquiry are sworn in. Left to right: Vice Admiral Adolphus Andrews, Admiral Orin Murfin and Admiral Edward Kalbfus. When they learned to their amazement and indignation that Kimmel had been deprived of vital information they reversed the Roberts findings and exonerated Kimmel. (David Richmond)

Members of the Navy Inquiry talk with Admiral Nimitz (back to camera) at Pearl Harbor. (David Richmond)

The Army Pearl Harbor Board was simultaneously convening. The members were equally appalled by similar evidence. Moreover, two of General Marshall’s closest subordinates, Colonel (later General) Bedell Smith (left) and Brigadier General Leonard Gerow (right) were involved in controversial testimony. Consequently the Army Board also reversed the Roberts findings, placing much more blame on Marshall than on Short. (National Archives)

James Forrestal, successor to Knox as Secretary of the Navy, put an endorsement on the Navy Inquiry report repudiating its findings. Secretary of War Stimson did the same to the Army’s report. (National Archives)

Tyler Kent, right, in Russia prior to transfer to London as a code officer in the American Embassy. He was imprisoned by the British in 1940 for possession of secret Roosevelt-Churchill messages. (Tyler Kent)

Mrs. Anne Kent worked tirelessly to free her son. The revelation that he was still in a British prison caused a stir during Roosevelt’s campaign for the presidency in 1944. (Tyler Kent)

Vice-President Harry S. Truman also inserted himself into the campaign controversy by implying in Collier’s that Short and Kimmel were not on speaking terms prior to the Pearl Harbor attack; and he made the false statement that at no time did “Admiral Kimmel ask or receive information as to the manner in which the Army was discharging its highly important duty.” Kimmel wrote Truman for a correction of the mis-statements but never received a reply. (National Archives)

THE INVESTIGATIONS, 1945–46

In a special investigation conducted by Vice Admiral Henry Hewitt, Captain Safford charged that he was pressed to repudiate his previous testimony about the “East wind, rain” message. Captain Alwin Kramer, who had supported Safford in the Navy Inquiry, did reverse his testimony. (Naval History)

THE CONGRESSIONAL HEARINGS

Marshall testifying on December 6, 1945. The table for the congressional committee is perpendicular to Marshall. Percy Greaves (extreme left), chief researcher for the Republicans, leans over to confer with Senator Homer Ferguson. Next to Ferguson, almost obscured, is the other Republican senator on the committee, Owen Brewster. (Wide World)

Rear view. Behind Marshall are General Short’s counsel (hand to face), the general, and Counselor Rugg. Extreme right center, Admiral Kimmel leans back. Both Short and Kimmel show their disbelief of Marshall’s testimony. (Wide World)

Republican Congressman Frank Keefe chats amiably with Marshall, but moments later his aggressive cross-examination puts the general on the defensive. (National Archives)

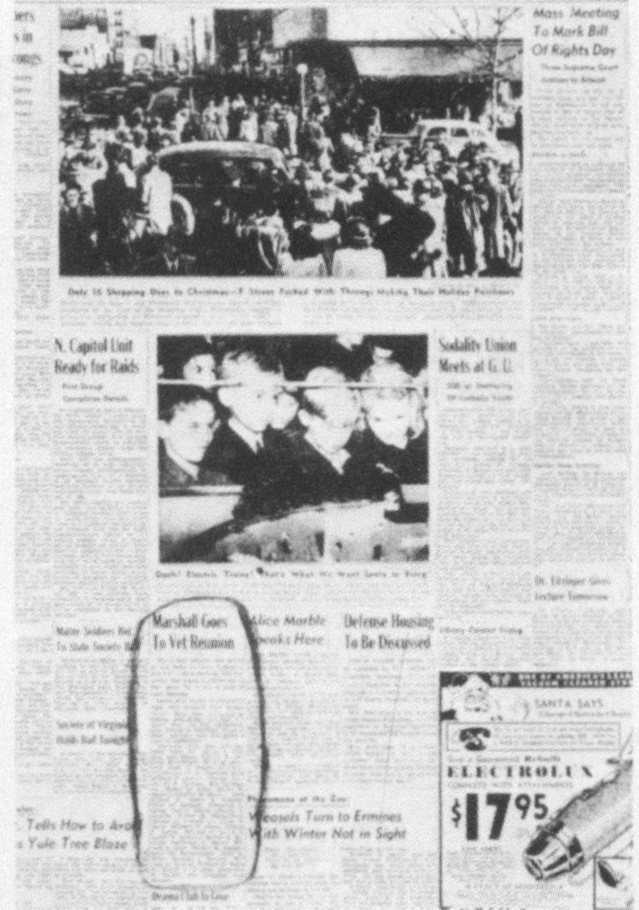

Marshall insists he cannot remember where he was on the night before Pearl Harbor. Investigators failed to check the December 7, 1941, issue of the Washington Times-Herald.

Percy Greaves with Senator Ferguson (left) and Senator Brewster (right). Greaves causes a tempest in a teapot on December 10 by smiling at something Democratic Senator Scott Lucas says. “I would like to know who the gentleman is,” storms Lucas, “and what right he has to sit alongside of the committee table and chuckle at a member of the United States Senate.” (Wide World)

At last, in early January 1946, General Short, weakened by illness, has his day in court. As he tells how his old friend of thirty-nine years, George Marshall, advised him “to stand pat,” tears come to Short’s eyes. “I told him I would place myself entirely in his hands, having faith in his judgment.” Until mid-1944 Short had regarded Marshall as his friend. Then Kimmel told him about the intercepted messages. “Short, Marshall is your enemy. Haven’t you found that out yet? He is doing everything he can to double-cross you and has been right from the very beginning.” (National Archives)

Chief Warrant Officer Ralph T. Briggs with his wife and her Seeing Eye dog. He told Captain Safford he had received the controversial “East wind, rain” message a few days before the attack. Briggs offered to testify at the hearings but was forbidden to do so by his commanding officer, who told him, “Maybe someday you’ll understand the reason for this.”

In 1960 Briggs, then officer in charge of all U. S. Navy World War II communications intelligence and cryptic archives, found what he believed to be his log sheet of the “East wind, rain” message. He felt he had no right to make a copy, but did write his comments on the bottom. At the request of the author, the classified Briggs material was released by the U. S. Navy.

Safford swears that his superiors ordered him to destroy all the notes he had made of the circumstances concerning the “East wind, rain” message (left). Other sensational revelations by Safford bring forth a savage, relentless cross-examination by Democratic Congressman John W. Murphy (right). “We haven’t touched the real meat of this,” the triumphant Murphy tells reporters after the session. “There’s real, genuine tenderloin in it.” The next day he continues his attack until Republican Keefe protests so eloquently that the onlookers spontaneously applaud. They do so twice more until rebuked by the chairman. (Wide World)

Safford chats with his friend Captain Kramer just before the latter testifies that there was no “East wind, rain” message. (Wide World)

Former Lieutenant Colonel Henry C. Clausen testifies that he had been “as free as the wind” in his one-man investigation for Stimson. He also denies charges that he had browbeaten witnesses, including Colonel Rufus Bratton, into changing their testimony. (Wide World)

Colonel “Togo” Bratton admits he was not browbeaten by Clausen—and then reveals new testimony damaging to his former chief, General Marshall. (Wide World)

Admiral Stark on a boat ride with the Krick family in 1939. On the last day of the hearings, Captain Harold Krick testifies that he recalls Stark’s telephoning the President late evening of December 6, 1941. (Harold Krick, Jr.)

Commander Lester Robert Schulz—pictured above with his wife and child when he was communications assistant to Roosevelt’s naval aide in 1941—causes a sensation on February 15 by revealing that on Pearl Harbor eve he had delivered an intercepted Japanese message to Roosevelt that caused him to say, “This means war.” (Rear Admiral Schulz)

Republican Congressman Bertrand Gearhart causes consternation among the Republicans when he signs the Democratic findings. He did so, according to Washington gossip, to save his seat in Congress that November. (Wide World)

TRACKINGS AND WARNINGS

C. A. Berndtson, Commodore of the Matson Fleet and captain of the luxury liner Lurline. His first assistant radio operator, Leslie Grogan, picked up suspicious Japanese signals as the ship headed toward Honolulu. (Matson Navigation Co.)

On December 2 Lieutenant Ellsworth A. Hosner and his assistant, of 12th Naval District Intelligence, get cross bearings on mysterious signals in the Pacific. Figuring these might be from the missing Japanese carrier task force, they alert their chief, Captain Richard T. McCollough, a personal friend of the President. By December 6 the unidentified task force is tracked to a position approximately 400 miles north-northwest of Oahu. (Seaman First Class Z)

On December 3, 1941, the Lurline docks near the Aloha tower. Grogan and the chief operator walk the few blocks up Bishop Street to the downtown Intelligence office of the 14th Naval District and turn over their data to a naval officer. (Matson Navigation Co.)

Hosner’s assistant, Seaman First Class Z, an electronics expert at twenty, had already designed a device being used on all U. S. Navy landing craft. (Seaman First Class Z)

Hosner’s office on the seventh floor of 717 Market Street, San Francisco. (Seaman First Class Z)

THE DUTCH CONNECTION

On December 2, 1941, Captain Johan Ranneft, the Dutch naval attaché in Washington, is informed by U.S. Naval Intelligence that two Japanese carriers are proceeding east and are now about halfway between Japan and Hawaii. On December 6 Ranneft again visited the Office of Naval Intelligence and asked where the two Japanese carriers were. An officer put a finger on the wall chart some 300–400 miles west of Honolulu. Ranneft reported all this to his ambassador and to his superiors in London. (Rear Admiral Johan Ranneft)

Excerpt from Captain Ranneffs official diary, supplied to the author by the Historical Department of the Netherlands Ministry of Defense. After the U.S. officer pointed out the position of the carriers just northwest of Honolulu, Ranneft reports: “I ask what is the meaning of these carriers at this location: whereupon I receive the answer that it is probably in connection with Japanese reports of eventual American action. No one among us mentions the possibility of an attack on Honolulu. I myself do not think about it because I believe that everyone in Honolulu is 100 percent on the alert, just like everyone here at O.N.I.”

Soon after the war, Ranneft, now a rear admiral, is presented the Legion of Merit for outstanding service to the United States by Admiral Nimitz. (Rear Admiral Johan Ranneft)

In early December 1941 General Hein Ter Poorten, Commander of the Netherlands East Indies Army, informs Brigadier General Elliott Thorpe, the American Military Observer in Java, that a Japanese message in the consular code has just been intercepted informing their ambassador in Bangkok that attacks would soon be launched on Hawaii, the Philippines, Malaya and Thailand. The signal for war against the United States would be “East wind, rain.” (Netherlands Department of Defense)

In 1943 General Albert C. Wedemeyer was told by Vice Admiral Conrad E. L. Helfrich that the Dutch knew the Japanese were going to attack Pearl Harbor and that his government had warned the United States. (General A. C. Wedemeyer)

Some of the Javanese students who helped Dutch Colonel J. A. Verkuhl and his wife solve the Japanese consular code. (Karel Rink)

General Thorpe (pictured here with MacArthur [center] in 1945) transmitted the full information from Ter Poorten to Washington. There is no record that this, or a second message, was ever received. No one ever admitted seeing them. A few days later Thorpe sent a third message through the American consul, but the latter omitted mentioning the location of the attacks and added that he “attached little or no importance” to the intercept. Thorpe sent out a fourth message a few days before the attack, which was acknowledged by Washington. He was ordered to send no more dispatches on the subject. The fourth message was found in War Department files, but the paragraph warning of the Hawaii attack was, curiously, deleted in transmission. (General Elliott Thorpe)

Early in December 1941 FBI agent Robert L. Shivers (seen here with Colonel Kendall Fielder, General Short’s Intelligence officer) warned Lieutenant John A. Burns of the Honolulu police that Pearl Harbor was going to be attacked in a few days. (Brigadier General Kendall Fieldeé)

Burns, head of the Honolulu Espionage Bureau, later became three-time Governor of Hawaii. (Mrs. John A. Burns)

In Cairo on December 6, 1941, Colonel Bonner Fellers (foreground), later MacArthur’s Military Secretary, was told by the British Air Marshal in charge of the Middle East: “We have a secret signal Japan will strike the United States in twenty-four hours.” (Collection of Mrs. Bonner Fellers)

At the emergency Cabinet meeting on the evening of December 7, 1941, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins was extremely perturbed by the President’s strange uneasiness. “I had a deep emotional feeling that something was wrong, that this situation was not all it appeared to be.… His surprise was not as great as the surprise of the rest of us.” (National Archives)