Let us fight the Monster, let us beat the Monster down

Queen Louise of Prussia on Napoleon

A woman with a pretty face, but little intelligence and quite incapable of foreseeing the consequences of what she does

Napoleon on Queen Louise of Prussia

Butterflies are not associated with battlefields (although they may actually be found there, fluttering incongruously amid the trampled corn and wildflowers of a long hot bloodstained summer’s day). Napoleon Bonaparte thought that women did not belong there either: he had a profound dislike of anything approaching the Amazon in womankind, and theoretically even intriguing women met with his censure. As he assured his first wife Josephine, he liked women to be ‘bonnes, douces et conciliantes’ and on another occasion ‘bonnes, naïves et douces’; adding, with more tact than accuracy, that that was because such good, sweet, naïve, soothing women resembled her.1

The object of Napoleon’s disapproval was Queen Louise of Prussia. Ironically enough, she was by nature quite as gentle and submissive as the most exigent male could require, as well as being as lovely a princess as ever won the heart of a king. It was cruel destiny – a destiny incarnated by Napoleon himself – which transformed this harmless and iridescent creature into a Warrior Queen ‘dressed as an Amazon’ as Napoleon termed her in 1806, in the uniform of her regiment of dragoons: writing twenty incendiary letters every day, ‘an Armida in her madness destroying her own palace with fire’. The reference was to Gluck’s opera Armide, popular with both French and Prussian audiences: it was in fact performed in Berlin for Louise’s own wedding day. The eponymous heroine was a princess of Damascus at the time of the First Crusade, founded on Tasso’s ‘wily witch’ in Jerusalem Delivered who, foiled of her lover, ended by calling on demons: ‘destroy this palace!’2

Queen Louise’s tragedy, in one sense, lay in the fact that she found herself matched against a man whom the Queen and her circle were inclined to sum up in one simple expression of horror as the ‘Monster’. This was of course too simple a judgement: the real threat was not so much in Napoleon’s perceived monstrosity of nature as in the brilliance of his military talent. Even one of Louise’s staunchest confidantes ruefully admitted that war was Napoleon’s trade: ‘he understands it and we do not’.3

But there was another deeper layer to Louise’s tragedy, which made of her a genuine martyr to her people’s own zeal at the time, as well as a patriotic heroine and martyr to the generations which followed. If Napoleon was indeed a monster, then it was optimistic at best to match the frail Queen Louise against him. Why did the fact that she emerged crushed from the encounter, failing to save Prussia from his depredations, generate surprise as well as despair? This was a development which must always have been expected along a level of common sense. The answer lies in the false but exciting expectations sometimes aroused in the human breast by the sight of one type of Warrior Queen: ‘sainted’ and ‘possessed of angelic goodness’ – descriptions freely applied to Queen Louise – this Holy Figurehead of the Prussian armies must surely bless her people with victory over the forces of evil.

It is true that the Queen did have, apart from her beauty, the natural appeal of a female in distress, to which male soldiers traditionally reply by springing to arms. It is a point of view most famously expressed by Edmund Burke in his lament for another tragic queen, Marie Antoinette: ‘I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult’. In similar if less exotic terms Robert Wilson, a young British envoy at the Prussian court, wrote movingly of the spectacle of Louise’s melancholy following the defeat at Jena in 1806: ‘but soldiers must not reflect, and a beautiful woman in misfortune should animate to enterprise’. Besides, Louise’s grief was a potent symbol of her nation’s woe, for which reason ‘a queen in distress is universally acknowledged to be a more tragical sight than the more disastrous and general calamities of the commonalty’.4

Despite this inspiration, Queen Louise’s own powers as a Warrior Queen were, if challenged by the brutal reality of conflict and disaster, a mere illusion, vanishing into the mists of romance and chivalry from whence they came. Her story illustrates how the ‘fancy dress’ aspect of a Warrior Queen, so brilliantly developed by Elizabeth I at Tilbury to mask the possible weaknesses of her position as a female ruler in time of war, might come to be mistaken for the real thing: a passive queen allows herself to be used, ignorant of the true hollowness of her position because she has been trained by upbringing to female impotence, just as Boadicea, a doughty battling queen in literature at the end of the sixteenth century, becomes a modest and delicate princess two hundred years later, who conquers with a blush not a spear, rides in a litter not a chariot.

Under different circumstances – and with a different character involved – the ‘distress’ of a queen could indeed be used to good effect. Robert Wilson, suggesting that Louise’s misfortunes should spur her supporters to military action on her behalf, recalled the example of Maria Theresa sixty years before: ‘So thought and felt the nobles of Hungary, and Maria Theresa retrieved the fortunes of her house.’ The reigns of two great empresses, Maria Theresa of Austria and Catherine the Great of Russia, spanned altogether over seventy years, 1740 to 1780 and 1762 to 1796 respectively. Gibbon was well able to write in his Decline and Fall, first printed in 1776, of those ‘illustrious women’ able to bear the weight of empire: ‘nor is our own age destitute’.5

These great tracts of time were matched by the vast tracts of land over which each woman presided. At first sight, however, the resemblance between the two stops there; not only their characters but the circumstances which brought them to power were certainly very different. The Archduchess Maria Theresa was a young married woman of twenty-three when the death of her father the Emperor Charles VI brought the male Habsburg succession to an end; but by that treaty of 1713 known as the Pragmatic Sanction, the right of his eldest daughter to succeed had been theoretically accepted. Sophie-Auguste of Anhalt-Zerbst, born in 1729 and thus twelve years younger than Maria Theresa, was on the other hand an obscure German princess before her marriage to the Grand Duke Peter, heir to the Tsarina Elisabeth of Russia. By this union she was transformed first into the Grand Duchess Catherine, and then, following a dramatic coup in which her doltish husband was deposed, into the Tsarina Catherine II; she was by now in her early thirties, someone who could claim to have contributed strongly to her own surprising exaltation.

When time and various military endeavours had combined to establish Maria Theresa securely on her hereditary throne of Hungary, with her husband Francis of Lorraine beside her as the elected Holy Roman Emperor, she displayed in private a love of cosy royal family life with her apparent infinity of children. Personally chaste, she also showed an austerity, even puritanism of temperament which recalls the ‘sainted’ Isabella of Spain. The pleasures of Catherine II were, notoriously, rather different. This was Voltaire’s ‘Semiramis of the North’, the Warrior Queen with a taste for magnificently strong guards officers as lovers, who in her day created a sensation for her debauchery: ‘excesses which would dishonour any woman whatever her station in life’ in the disapproving opinion of the British Ambassador to her court. She herself actually believed, engagingly enough, in frequent (and incidentally straightforward) sexual activity as a means to health; but she never denied that it was also enjoyable, and as such should be welcomed. ‘Nothing in my opinion is more difficult to resist than what gives us pleasure’, wrote Catherine. ‘All arguments to the contrary are prudery.’ It was a hedonistic point of view shared in no way by the pious and self-abnegatory Maria Theresa.6

Yet there was a further interesting resemblance between the two rulers despite their opposing personal morality. Both the Queen-Empress and the Tsarina encountered that familiar problem for a reigning female, the need to exert military leadership, or at least some kind of leadership in war (although the Russian Empire, unlike Austria, had known the rule of other women autocrats, including Catherine’s own mother-in-law Elisabeth). In both cases, they made use of the skilful technique of Elizabeth I, putting on a show of glory, in which the appealing femininity was artfully contrasted with stern and indeed noble patriotic resolve. And neither of them, despite presiding over military victories, had that heroic love of war for its own sake which has marked so many male rulers: Louis XIV, who boasted in 1662 that glory was the principal aim of all his actions, recommended his great-grandson on his deathbed half a century later, ‘Do not imitate my love of war.’7

The first challenge to Maria Theresa occurred when Frederick the Great of Prussia snatched her province of Silesia only seven weeks after her father’s death. To Carlyle, this act of territorial rape, contrary to Frederick’s promised word, was merely the Prussian King grabbing bravely at Opportunity as at a wild horse: ‘rushing hitherward, swift, terrible, clothed with lightning like a courser of the gods; dare you catch him by the thunder-mane and fling yourself upon him …’. Many may prefer the cooler estimate of Macaulay concerning the War of the Austrian Succession: ‘The selfish rapacity of the King of Prussia gave the signal to his neighbours. The whole world sprang to arms …’. (We might forgive Carlyle for his blithe cruelty towards one Warrior Queen, for the sake of that bright suggestion made to the young Miss Jane Welsh that Boadicea would be the ideal subject for her initial ‘literary effort’, with the comforting rider that ‘she need not be “big” or “grim” unless you like’ – except for the fact that bigness and grimness were the qualities that Carlyle evidently admired.)8

The young Maria Theresa was hailed as Queen of Hungary by her loyal subjects in that country, or rather by an oxymoron of a title – domina et rex noster (our mistress and our king), another variant of that familiar theme of gender transference. In her beleaguered state, the domina–rex was at least armed with one important weapon in the shape of an infant male heir; and she was quick to play upon the appealing possibilities of the image of the Warrior Queen as Young Mother. Sending a picture of herself and the child to General Khevenmüller in 1742 just after he had taken Munich on her behalf, Maria Theresa wrote this accompanying letter: ‘Dear and faithful Khevenmüller – Here you behold a queen who knows what it is to be forsaken by the whole world. And here also is the heir to her throne. What do you think will become of this child?’9 The next day the troops at Linz were shown both the picture and the letter, amid outbursts of wild enthusiasm.

At her coronation at Pressburg (Bratislava) in Hungary Maria Theresa mounted a huge black charger, and according to immemorial custom drew her sword to the four points of the compass, to signify her role as Hungary’s protector. This was once again Elizabeth I at Tilbury, making the show stand for the substance, especially as Maria Theresa had to learn to ride astride specially for the event: furthermore, she had only just over a month in which to do so (following the invitation to Pressburg) and was in the process of recovering from the birth of her first son. Thereafter Maria Theresa continued to enjoy all the spectacles of military life such as reviews, parades and manoeuvres in which she could similarly display herself. She designed a uniform for herself and her ladies on these occasions which combined the practical chamois leather breeches and boots of the rex beneath, with the voluminous skirts of the domina above.

None of this amounted to a predilection for warmongering. The frequent battles she had to fight were more likely to be in defence of her own inheritance than in pursuit of others’. Indeed the Queen (in her own right) and Empress (by virtue of her husband’s election) displayed on occasion a consciousness of the sheer immorality of national aggression which seems to have been rooted in her own personal piety. When the Polish Partition of 1772 was first suggested, Maria Theresa protested against the robbing of an innocent nation ‘that it has hitherto been our boast to protect and support’, adding ‘The greatness and strength of a state will not be taken into consideration when we are called to render our final account.’ Towards the end of her life the Empress protested vehemently against Austria’s attempt to annex Bavaria: ‘Let them call me a coward, a weakling, a dotard if they like [she was approaching sixty], nothing shall prevent me from extricating Europe from this perilous situation.’ Afterwards she said: ‘For me it is an inexpressible happiness to have prevented a great effusion of blood.’

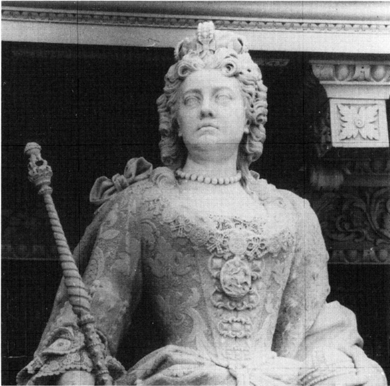

More symbolic of her personal style than the image of the young Queen on the black charger at the beginning of the reign, is that presented by the statue erected in the nineteenth century opposite the Hofburg in Vienna. Here the Empress – ‘the General and first Mother of the said Dominions’, as she described herself – is seen presiding like an enormous benevolent muffin in her long dress and ceremonial robes (there is no glimpse of those practical chamois leather breeches and boots).10 All about her, at the four corners of the statue, prance on horses, her male generals and ministers, both smaller and more active.

Unlike Maria Theresa, Catherine the Great did have, it is true, a penchant towards glory. When she told her adoring correspondent Voltaire in 1771 that ‘the nation’s glory is my own, that is my principle’,11 she summed up an intelligent philosophy which explained how she had come to rule the unwieldy Russias so successfully for the last nine years. This little German Princess had loved rough games as a child, hating to be fobbed off with dolls and cots instead of riding and shooting birds with the local children. As the unheeded bride of the Grand Duke Peter – their marriage was not consummated for nine years – she took her chief pleasure in riding, even in bed, by her own account, where she galloped away her frustration as ‘a postilion on my pillow’.12 When the Tsarina Elisabeth protested that riding like a man on a flat saddle led to sterility, the neglected wife replied pointedly that the more violent the exercise, the more she liked it. As Tsarina herself, Catherine put this caged energy to good use.

The coup against Catherine’s husband, who had succeeded as the Tsar Peter III at the beginning of 1762, took place six months later. It was ten o’clock of the light northern night on 29 June, according to the Russian style of dating; there was thus scarcely any darkness to shroud the startling spectacle of the Grand Duchess Catherine, dressed in uniform, at the head of the rebel regiments whose members included prominently her current lover Grigory Orlov and his brother. When these rebels – disgusted by the Tsar’s pro-German policies – had come for Catherine, she had borrowed the green and red uniform of a young officer, Captain Talietzin, in the Semeonov-sky regiment, who was slight enough for his clothes to fit her. Her lady-in-waiting Princess Dashkova took the uniform of another young officer, Lieutenant Poushkin. According to the Princess’s memoirs, it was she, Dashkova, who suggested that her mistress should now substitute the Order of St Andrew for that of St Catherine worn over her uniform: the order of St Andrew was theoretically worn only by the reigning sovereign, and the substitution was thus a dramatic gesture indicating the assumption of command.13

‘For a man’s work, you needed a man’s outfit’ was Catherine’s official explanation for her masculine attire14 (although since she had been accustomed to steal out of her palace in man’s costume to meet her lover Stanislaus Poniatowski, it could clearly be used for a woman’s work as well). The former tomboy easily mounted the mettlesome grey stallion brought for her use and mastered it. With her drawn sword and her long flowing hair beneath her black three-cornered hat lined with sable and decorated with oak leaves, the symbols of victory, Catherine now presented a very passable goddess of war at the head of her troops. The loyalty inspired by the sight was epitomized when a young NCO rushed forward to present her with a pennant for her naked sword. His name was Grigory Potemkin.

During her long reign, her triumphant progress towards military victories galore – she listed seventy-eight of them – Catherine never failed to present herself wherever possible in the same heroic light. When the French diplomat the Comte de Ségur first saw her in 1785, he found her ‘richly attired, her hand resting on a column’. Her majestic air, the pride in her expression and her ‘slightly theatrical pose’ so took him aback that he forgot his speech of welcome. So successful was this projection that the portrait painter Madame Vigée Le Brun, meeting her during a tour of Russia, was amazed to discover that the Tsarina was actually very short: ‘I had fancied her prodigiously tall, as high as her grandeur’.15

Ségur described her in the course of that triumphal procession to Kiev of 1787 arranged by Potemkin, following the defeat of Turkey and Russia’s annexation of the Crimea, which brought her both the fruitful steppes of the south and an invaluable access to the Black Sea. Stout and tiny in her military uniform, she was nevertheless ‘a conquering empress’. The descendants of the Tartars who had once swept across this territory (putting an end to the Georgian empire of Tamara) now prostrated themselves before ‘a woman and a Christian’.16 When a Georgian prince from Colchis brought presents to the foot of the Russian Tsarina Catherine’s throne, it might be argued that the memory of Queen Tamara, in her sex if not her nationality, had been avenged.

Catherine, like Tamara six centuries before, understood how to make use of that deep mystical Slavic feeling towards the mother goddess, as well as the conquering goddess of war. To Orlov she was ‘little mother’ as well as ‘most merciful sovereign lady’. To the later lover Potemkin she was ‘Mother Tsarina Catherine … far more than a mother to me … my benefactress and my mother’. On the other hand, like Queen Elizabeth I, she did not consider that she belonged (unlike most mothers) to the ‘weak, frivolous, whining species of women’; in this respect she was certainly the Warrior Queen as an honorary male. When Catherine founded an orphanage, for example, she ordered that the girls should learn to cook and make bread, following the much praised women of the Bible and those hard-working ones celebrated by Homer17 (by which she definitely did not mean the Bible’s sword-wielding Judith or Homer’s flashing-eyed Athene, felling the war-god Ares with a stone).

At her accession, in fact, Catherine suffered from the same prudent dislike of war as Elizabeth I and for the same reason: the debts incurred by Russia during the Seven Years’ War, which ended a year later in 1763. Even in 1770, after a successful campaign against the Turks, Catherine believed peace to be a fine thing, though she now admitted that war also had its ‘fine moments’.18

Voltaire’s correspondence with Catherine concerning the Turks was on a far more rambunctious level and there is a nice flavour of chivalry too: ‘these barbarians deserve to be punished by a heroine for the lack of respect they have hitherto had for ladies’, he wrote to the Tsarina in November 1768, a month after war had been declared by the Turks. ‘Clearly, people who neglect all the fine arts and who lock up women, deserve to be exterminated.’ A year later he was admonishing his ‘Semiramis’ and his ‘Northern Star’ in still more ardent terms: ‘Come now, heir to the Caesars, head of the Holy Roman Empire, defender of the Latin Church, come now, this is your chance.’ When there was news of a victory, he described himself as jumping out of bed in ecstasy: ‘Your Imperial Majesty has brought me back to life by killing the Turks.’ Voltaire’s subsequent salute was a weird parody of the language of religion: for he began by crying ‘Allah! Catherine!’ and went on to sing ‘Te Catharinam laudamus, te dominam confitemur’.19

Catherine herself had a more controlled appreciation of these tumultuous events. Did they serve the interest of Russian greatness (with which of course she identified herself)? That was her persistent concern. She had her own well-developed sense of Russian national pride – Russia, the country she had so successfully adopted. Not only did she display a taste for operas which celebrated Russian history, she also littered the imperial grounds at Tsarskoe Selo with monumental reminders of Russian military triumphs including obelisks and marble columns as well as war memorials. In 1771 she agreed with Voltaire that ‘this army will win Russia a name for herself’. But when she declared that ‘great events have never displeased me and great conquests have never tempted me’, the second half of her statement was not quite as disingenuous as the list of her achievements and territorial acquisitions might indicate.20

Her own nominee on the throne of Poland and some of its territory annexed by Russia, further acquisitions on the Alaskan coast, to say nothing of the defeat of Turkey and Russia’s surge into the Crimea, her revenues mightily increased: all this was brought about by only six years of war in her twenty-five-year reign. Nor, in all this, was Catherine a mere glittering figurehead of a Warrior Queen. Where military and naval matters were concerned, she played an active directing part. Attending twice-weekly meetings of the seven-man council which directed the war during the Crimean campaign, she herself was probably the originator of the daredevil plan whereby the Russian fleet in the Baltic sailed five thousand miles round the coasts of Western Europe to engage the Turks.

The results of this brilliantly executed expansionist policy for Russia were extraordinary: twenty million subjects owed Catherine loyalty at her coronation, compared to thirty-six million in 1795 shortly before her death. It was however expansion, not war itself with its manufactured heroics, which interested her, even if she could manufacture heroics herself with a will, where necessary. ‘We need population not devastation’: that was her philosophy. In short, as she herself declared, ‘peace is necessary to this vast empire’:21 a perceptive comment on the vast Russian ‘empire’ at any stage of its history.

Where Warrior Queens are concerned, we return from the users – Maria Theresa and Catherine – to the used – Louise of Prussia. Although described by Napoleon as an ‘Armida’, there was by temperament nothing of Tasso’s ‘wily witch’ and Gluck’s destructive enchantress about Queen Louise of Prussia. ‘Every day I realize that I am a weak woman,’ she wrote during her early carefree years, ‘and I am weak because I am kindhearted. I want everyone to be happy, and so I forgive, forget, and fail to scold when I should …’.22

Canossa in 1077; Countess Matilda of Tuscany extends a supplicating hand to Pope Gregory VII, on behalf of the kneeling, penitent Emperor Henry IV; from Donizo’s contemporary Vita Mathildis. (ill. 17)

Fifteenth-century depiction of the Empress Maud (Matilda), claimant to the throne of England, from a history of England written by monks at St. Albans. (ill. 18)

A nineteenth-century Belgian evocation of Countess Matilda at Canossa, painted by Alfred Cluysenaar. (ill. 19)

Queen Tamara of Georgia; an engraving published in 1859. (ill. 20)

The monogram of Queen Tamara, formed from the letters TAMAR in the Georgian knightly hand, and employed in the copper coinage of her realm. (ill. 21)

Queen Isabella of Spain; a detail from the painting The Madonna of the Catholic Kings. (ill. 22)

Medal (c. 1480) showing Caterina Sforza, the spirited daughter of the Duke of Milan; her fate, as a would-be female ruler of Forlì, contrasted unhappily with that of Isabella of Spain. (ill. 23)

Triumphal entry of Ferdinand and Isabella, ‘the Catholic kings’ of Spain, into Granada in January 1492 following the conquest of the last Moorish kingdom; a bas-relief on the altar of the Royal Chapel in the cathedral. (ill. 24)

The earliest loose popular print of Queen Elizabeth I: William Rogers’ Eliza, Triumphans of 1589 (the year following the defeat of the Spanish Armada) shows the Queen as Peace, with an olive branch in her hand, while Victory and Plenty proffer her their crowns. (ill. 25)

Queen Elizabeth and the Three Goddesses (Juno, Pallas Athene, and Venus seen against a background of Windsor Castle), attributed to Joris Hoefnagel, 1569; it has been suggested that this allegorical picture refers to the Queen’s suppression of the Northern Rebellion, the first military initiative of her reign. (ill. 26)

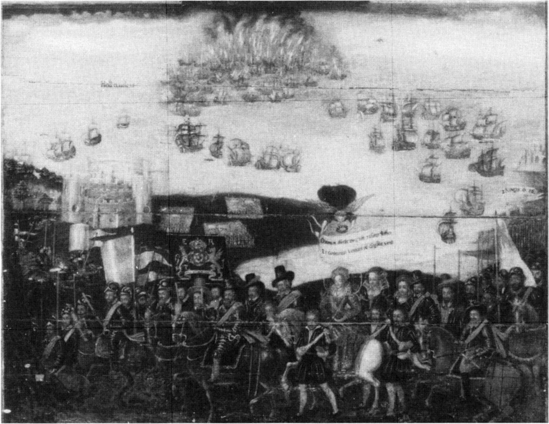

Panel from St. Faith’s Church, King’s Lynn, showing Queen Elizabeth reviewing her troops at Tilbury in 1588. (ill. 27)

A group of illustrations of the life of Jinga Mbandi, the seventeenth-century Queen of Angola, from Relation Historique de l’Ethiopie Occidentale by Father J. P. Labat, 1732.

Queen Jinga being received by the Portuguese Governor, Correira de Sousa, in about 1622; according to one of the best-known legends about her, she commanded one of her servants to form a seat when the Governor failed to offer her a chair.(ill. 28)

(ABOVE, LEFT) Queen Jinga receives Christian baptism as the Lady Anna de Sousa (in honor of the Governor); she subsequently returned to her tribal name, variously given as Zhinga, Nzinga, and Jinga. (ABOVE, RIGHT) Queen Jinga venerates the bones of her brother, whom she succeeded as ruler. (Some stories hold that she had him murdered.) (ill. 29) (ill. 30)

Statue of Queen Anne by Rysbrack at Blenheim Palace; the reality of her appearance was very different from this august image. (ill. 31)

The Empress Catherine II of Russia, after a portrait by V. Erichsen painted in 1762, the year of her coronation; this followed the coup by which, at the head of the rebel regiments, she supplanted her husband Tsar Peter III. She borrowed a uniform to do so: ‘For a man’s work, you needed a man’s outfit’, she wrote. (ill. 32)

The Empress Maria Theresa of Austria at her coronation as Queen of Hungary at Pressburg in 1742; she mounted a charger and drew her sword to the four points of the compass to signify her role as Hungary’s protector, according to the ancient tradition of the Hungarian kings. (ill. 33)

Nineteenth-century monument to Maria Theresa opposite the Hofburg in Vienna, showing her towering majestically above her male ministers and generals. (ill. 34)

Queen Louise of Prussia, painted by Grassi in 1802 when she was twenty-six. ‘There prevails a feeling of chivalrous devotion towards her’, wrote an English diplomat at her court; ‘a glance of her bright laughing eyes is a mark of favour eagerly sought for’. (ill. 35)

The celebrated print of King Frederick William III of Prussia and the Tsar Alexander I swearing brotherhood over the tomb of Frederick the Great, watched by Queen Louise; after Napoleon’s occupation of Berlin a cruel caricature of the same print was issued, with the Tsar as Nelson and Louise as Lady Hamilton, currently notorious in Europe as Nelson’s mistress. (ill. 36)

Napoleon receiving Queen Louise at Tilsit, 6 July 1807; the Queen is supported by her husband and watched by the Tsar. A detail from a picture by N. L. F. Gosse. (ill. 37)

The Rani of Jhansi, a watercolour from Kalighat, 1890. (ill. 38)

Contemporary painting, by an unknown artist, of Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi; both Indian and British sources bear witness to her striking appearance. (ill. 39)

The site of the massacre of Europeans at Jhansi on 7 July 1857; the Rani was subsequently blamed—unjustly—for betraying them. (ill. 40)

Hindu mythology contains several warrior goddesses; here Durga, wife of Siva, is seen seated on her tiger, slaying the demon Mahesasura with the aid of her ten arms; unlike Kali, another of Siva’s wives and the goddess of destruction, Durga (to whom both the Rani and Mrs. Gandhi were compared) is portrayed as beautiful and basically benevolent, despite her capacity for aggression. (ill. 41)

Statue of the Rani of Jhansi at Gwalior; she was killed here on or about 17 June 1858, leading her men in a battle to defend the fortress from the British assault under Sir Hugh Rose. (ill. 42)

Mrs. Golda Meir salutes the detachment commander of Israeli paratroops; her own ‘grandmotherly’ uniform includes a handbag. (ill. 43)

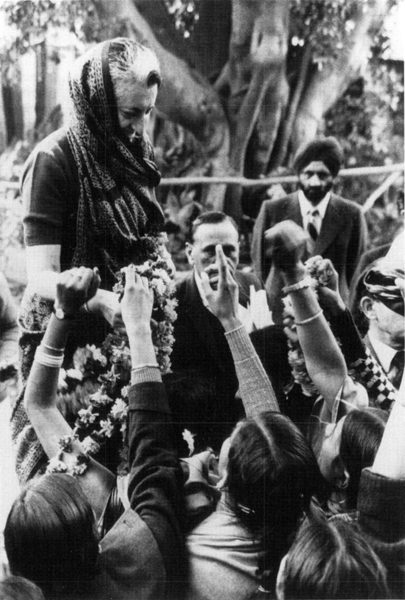

Well-wishers present garlands to Mrs. Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister of India and Leader of the Congress Party. (The newspaper caption to this photograph read ‘Garlands for Mother Indira’.) (ill. 44)

Mrs. Margaret Thatcher with a model of a Chieftain tank in 1987. (ill. 45)

Her majesty Queen Elizabeth II in military uniform at the Trooping of the Colour, enacting the purely ceremonial role of the ‘Armed Figurehead’. (ill. 46)

Mrs. Thatcher at the dinner held on 26 January 1988 to celebrate her record as the longest-serving Prime Minister in twentieth-century Britain; she is surrounded by members of her cabinet (her husband Denis Thatcher is on her left); it is noticeable that there are no female Cabinet ministers to distract attention from the central figure in her glittering brocade costume, amid the attendant dinner-jacketed males. (ill. 47)

A June 1982 cartoon of Mrs. Thatcher in Boadicean breastplates and driving a chariot (Ronald Reagan is seen, somewhat smaller, as a cowboy). It was published in the Daily Express following Mrs. Thatcher’s appearance on American television after the conclusion of the Falklands War, in which she described herself as having the ‘reputation of being the Iron Lady’. (ill. 48)

Like Catherine a minor German princess, Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz possessed, apart from this sweet feminine pliancy, the gift of beauty. On Louise’s exquisite looks there is a remarkable agreement of testimony. In 1793, when she was seventeen, her ravishing appearance captured the heart of Frederick William, the shy young heir to the throne of Prussia: ‘it is she, and if not she, no other creature in the world’, he is reputed to have exclaimed at the mere sight of her (much as Isabella of Castile is supposed to have greeted Ferdinand). A decade later, seeing the Prussian Queen dressed as Statira, the Persian bride of Alexander the Great at a fête in Berlin, Madame de Staël was ‘struck dumb by her beauty’. In 1801 Madame Vigée Le Brun, whose observant painter’s eye was disappointed in the stature of Catherine the Great, alleged that her pen failed her in trying to describe Louise. The Queen happened to be in deep mourning on their first encounter, but her coronet of black jet served only to set off the dazzling whiteness of her complexion; as for the beauty of her ‘heavenly’ face Madame Vigée Le Brun compared it to that of a sixteen-year-old girl, with the perfect regularity and delicacy of the features, the grace of figure, neck and arms: ‘all was enchanting beyond anything imaginable!’23

In life this perfect regularity of feature and the supple slender figure often led to Queen Louise being compared to a Greek statue. For once, the art by which later generations must judge confirms and does not disappoint: there is something neo-Hellenic about the many representations of her which have survived, enhanced naturally by the clinging Grecian style of contemporary fashion which suited her so well. We can accept with relief the verdict of the English diplomat Sir George Jackson that the Queen was ‘really a beauty and would be thought so even if she did not sit upon a throne’. The chivalry she inspired is equally easy to understand: ‘among the younger men especially’, wrote Jackson, ‘there prevails a feeling of chivalrous devotion towards her; and a sunny smile, or glance of her bright laughing eyes, is a mark of favour eagerly sought for’.24

At first it was all lightness at the Prussian court, Frederick William succeeding his father in 1797, four years after his marriage. Perhaps the Queen – who was after all young – danced a little too much (she danced at a court ball in 1803 within hours of giving birth) and she was also lightheartedly unpunctual. There are unpublished passages in the diary of Countess Sophie von Voss, Louise’s battleaxe of a lady-in-waiting (already in her seventies, with a father who fought against Marlborough at Malplaquet) that criticize the Queen’s frivolity and even her petulance in these early years; but Countess Voss’s final verdict was to be very different: ‘all the loveliest virtues of woman and the most pleasing to God’.25

On the other hand Louise’s surely admirable attempts at enlarging her perfunctory education with a study of German literature, to which more intellectual ladies-in-waiting introduced her, were greeted with boorish mockery by Frederick William. He described one of these intellectuals, Caroline von Berg, as ‘vain, trivial … and forever gushing poetry’. Nor was the reputation of Goethe sacred to the Prussian King. ‘Wha’s ’is name, t’great man from Weimar?’ Frederick William would enquire, aping the local dialect. Another of these ladies, Marie von Kleist, aunt by marriage to the poet and playwright Heinrich von Kleist, persuaded the Queen to patronize her nephew; he received an honorarium under oath of secrecy.26 Schiller became a special favourite: the Queen wanted him as Poet Laureate. She also read Shakespeare in translation.

The Queen’s tentative efforts at intellectual independence had however little in common with that kind of Amazonian behaviour described with all the richness of sexual violence in Kleist’s Penthesilea: ‘A nation has arisen, a nation of women, Bound to no overlord …’.27 Louise’s submissiveness, her wifely wish to please, was most notably demonstrated by the continuous procession of children that she bore. Ten years after her marriage she had already born seven; two of the children had died and there were also various miscarriages. Louise gave birth to a total of nine children in fourteen years, the last of them less than a year before her death.

When Madame Vigée Le Brun met the Queen in 1801, she could not make an appointment before noon because, as Louise explained, ‘the King reviews the troops at ten every morning and likes me to attend’. The only blight on this picture of domestic and marital bliss appeared to be the plain looks of Louise’s numerous children. ‘They are not pretty’, murmured the Queen sadly. ‘Their faces have a great deal of character’, was the painter’s tactful comment. Privately, she thought the youthful princes and princesses of Prussia downright ugly.28

But for Prussia and its king – if not yet its queen – already problems existed along more serious lines than those of a military review or a homely royal family. The rise of Napoleonic France had placed Prussia in a quandary: neutrality? And if not neutrality, alliance with which of the various great powers involved? It was a profound Prussian conviction of the time that its army, built up by Frederick William’s great-uncle Frederick the Great, remained the finest in Europe. Time would test the validity of that belief. In the meantime Frederick William’s indecisive nature led him to see his fine army as a bastion of Prussia’s neutrality rather than as anything more aggressive.

The King’s personal quandary however – neutrality versus alliance – remained. And it was this quandary, finally, which brought Louise to play the role of Warrior Queen. In 1803 the French forces occupied Hanover, a state which on the one hand Prussia was pledged to protect as a neutral zone, and on the other coveted for itself. Prussia was offered Hanover in return for a treaty with France. Frederick William hesitated unhappily. Napoleon made good use of his dilemma of conscience. The French judicial murder of the young Bourbon Prince the Duc d’Enghien on 21 March 1804 for alleged conspiracy horrified all royal Europe: but Louise was persuaded not to wear mourning for the Duc by the new Prussian Foreign Minister, the veteran statesman Carl-August von Hardenberg, who hoped to secure Hanover peaceably.

Louise’s martial instincts were still nascent. Placatory gifts of dresses from the newly created Empress Josephine (Napoleon assumed the title of Emperor on 18 May) were accepted: pale grey satin magnificently embroidered with steel, and white satin embroidered with gold thread, further adorned with Alençon lace and Brussels point. The Queen’s attempts at influencing the King towards war were dated nearly a year later by Sir George Jackson to February 1805. It was not until September of the same year that she was generally reputed to head the ‘war party’.29

What brought about the transformation? Napoleon himself angrily and publicly ascribed the change to another charismatic man: the Tsar Alexander I. There had been that magic summer at the Baltic coastal resort of Memel in 1802, the year following the accession of the young Tsar. The grandson of Catherine the Great, Alexander was an intensely attractive figure: even the crabby Countess Voss found him at this stage ‘irresistible’, with his handsome appearance and striking fair colouring (he was of course genetically far more German than Slav, his mother like his grandmother having been born a German princess).30 Memel, symbolically enough, was not only on the Baltic, but also on the borders of Prussia and Russia: here the two courts mingled and the two youthful royal families – already interrelated – relaxed together.

Louise flowered. ‘She was today more beautiful than ever’, wrote Countess Voss of one particular June evening. There was dancing every night, and presents for Louise from the Tsar including earrings of her favourite pearls (even Countess Voss got a pearl necklace). No wonder the Countess wrote that she was ‘quite grieved that these pleasant days should come to an end’.31 But further delightful co-celebrations were planned by Alexander, such as a pageant based on the happy days at Memel for Louise’s birthday the following March; Louise’s current baby would be named Alexandrina with the Tsar as her godfather.

For all Napoleon’s subsequent excoriations in which he vowed that the Prussian Queen had been ‘so good, so gentle’ until the Tsar’s baleful influence made her desert ‘the serious occupation of her dressing-table’ for politics,32 the story of an actual affair between Alexander and Louise was certainly a calumny. That primitive desire to find a Warrior Queen either preternaturally lustful or preternaturally chaste (Louise came in for both charges) may have played its part. The truth of Louise’s feelings for Alexander was probably subtler. What a contrast the romantic young Tsar – born in 1777, he was a year younger than Louise – presented to the vacillating and uncultured Frederick William! For Louise, well knowing her duty both as a wife and a queen, her unacknowledged sentimental devotion to the Tsar could be safely expressed in a public admiration for his policies and a trust in his political objectives. ‘I believe in you as I believe in God’, she wrote to Alexander at one point:33 this idolatry was not the outburst of a voluptuous and satisfied woman.

The late summer of 1805 brought persistent murmurs of war in the Prussian capital of Berlin. How could Prussia stand aloof while the French devoured half Europe? Frederick William reflected gloomily concerning his impossible position on 12 September: ‘Many a king has fallen because he loved war too well, but I may fall because I am in love with peace.’34 There was no doubt that the general Prussian mood veered towards war. Napoleon’s enemy the Tsar was cheered wildly at the opera in Berlin (the performance incidentally was of Armide). And when a secret pact was finally concluded between Russia and Prussia, agreeing to send an ultimatum to Napoleon, Louise’s influence over Frederick William was generally believed by those in the know to have brought it about. The treaty was signed on 3 November 1805. That night the three friends – Alexander, Louise and Frederick William – went secretly together to visit the tomb of Frederick the Great at the Tsar’s request (a popular contemporary print would depict them standing reverently beside the historic sepulchre). The episode represented the romantic culmination of Louise’s hopes that war would not only stop the unstoppable Napoleon, but bring honour to the Prussian King at last, by uniting him with the brave and honourable Tsar of Russia.

At the beginning of the next month it was Louise’s turn to be cheered wildly as she stood on the palace balcony to watch the Prussian troops leaving Berlin, the banners dipping as they passed. Her popularity with the army at this point knew no bounds. Here was their beloved patroness, she who had in peacetime attended those morning parades, danced at their balls, befriended young officers in trouble; now she was to be not only their queen but their goddess of victory. Moreover Louise herself had always reciprocated these feelings. When the Tsar praised her good relationships with the military, the Queen replied that ‘such a respected estate, whose vocation brought such toil and changes of fortune could not be admired enough’.35

Unknown to the Queen on her balcony, one of those swift changes of fortune which would affect the destiny of the bonny Prussian soldiers beneath her had already taken place. In late October Napoleon had secured the capitulation of the Austrians at Ulm; on 13 November he entered Vienna; on 2 December, in a brilliant striking manoeuvre, he had utterly crushed the Austrian and Russian forces at Austerlitz. When the news reached the Queen in Berlin, she exclaimed that ‘no one who is a German can hear of this and not be moved’. She was right to see the chilling significance of the defeat. Prussia for her part was simply told she must accept the territorial changes imposed: Hanover for example could be retained, but Ausbach (‘the cradle of the Hohenzollern race’ as Louise tearfully told Frederick William), Neuchâtel and Cleves with its fortress of Wesel must be given up. In June 1806 the Holy Roman Empire would be brutally ended, the Confederation of the Rhine put in its place.

The Queen, passionately opposed to the ratification of this Treaty, wrote: ‘There is only one thing to be done, let us fight the Monster, let us beat the Monster down, and then we can talk of worries!’36 Her words became a patriotic slogan for the party still resolutely opposed to dealing with Napoleon, just as the Queen herself was increasingly credited with all the qualities of inspiration the King so signally lacked. Prince Louis Ferdinand, Frederick William’s clever raffish cousin, remarked that if the people knew how much Louise had done, they would raise altars to her everywhere. Even without the benefit of altars, popular admiration expressed itself in a thousand ways. One unit demanded that its name be changed to the Queen’s Cuirassiers! Let Louise lead them!

With a weak king and a valiant queen, there was the inevitable emergence of the Better-Man Syndrome. After this period of debate and anxiety was over, Hardenberg would quote the famous words of Catherine de Foix to her husband Jean d’Albret: ‘If we had been born, you Catherine and I Don Jean, we would not have lost our kingdom.’ Queen Louise, he said, had an equal right to address her husband thus.37

It was not until the autumn of 1806 that the Prussian King’s hopes of treating with France were formally abandoned; he agreed at last to combine with the allies including Russia, Austria and England, to try to beat the ‘Monster’. By this time Queen Louise’s personal fixation against Napoleon as the source of all their woes had begun to be matched by the anger of the Emperor at what the Prussians considered her patriotic fervour but he deemed her womanly interference in dragging Prussia away from France. The Bulletin of the Army, an official propaganda publication, printed a conversation Napoleon was said to have had with Marshal Berthier: ‘a beautiful queen wants to see a battle, so let us be gallant. Let us march off at once to Saxony.’ It went on to report Napoleon’s outburst quoted earlier concerning the Queen with her army ‘dressed as an Amazon’. On another occasion: ‘So – Mademoiselle de Mecklenburg [an allusion to Louise’s birth outside Prussia] wants to make war on me, does she? Let her come! I am not afraid of women.’38

This elevation of Queen Louise to something more than a pretty woman attired from time to time in a becoming adaptation of military uniform suited both sides, in fact. But the Queen’s true intentions were probably better interpreted by Thomas Hardy later in his poetic drama The Dynasts, than by Napoleon. Here Hardy has the loyal Berliners protest against Napoleon’s insulting epithet of Amazon: ‘Her whose each act Shows but a mettled modest woman’s zeal … To fend off ill from home!’39 Alas, the mettled but modest Louise, like Armida, but for very different reasons, would all too soon find that very home laid low.

The French victory over Prussia at the double battle Jena-Auerstädt on 14 October 1806 virtually obliterated the Prussian army, that force which had, under Frederick the Great – dead only twenty years before – terrorized Europe. In the wake of the general destruction, the Queen found herself enquiring wildly for her husband: ‘Where is the King?’ ‘I don’t know, Your Majesty.’ ‘But, my God, isn’t the King with the army?’ ‘The army? It no longer exists.’40 The Prussian army, Prussia itself and for that matter Queen Louise were none of them ever to be quite the same after this ghastly day of national humiliation. (The French Marshal Davout would be made Duc d’Auerstädt for defeating an army twice his own strength.) A week before the battle, Frederick von Gentz, the philosopher–politician, had an interview with the Queen at the Prussian war camp in which she expressed herself ‘with a precision, a firmness and energy, and at the same time with a restraint and wisdom, that would have enchanted me in a man’.41 Afterwards, the Queen was transformed into both a fugitive and an invalid.

Her flight from the French was real enough. Napoleon had hoped that the Queen who had defied him would be captured. Although he was cross that she had escaped, he was at least able to exult in the Bulletin of the Army: ‘She has been driven headlong from danger to danger … she wanted to see blood, and the most precious blood in the kingdom has been shed.’ As for Louise’s health, that finally collapsed as she made her painful way via Berlin and Königsberg to Memel, safe on the borders of Russia but already wrapped in the Baltic winter. Snow was falling in heavy flakes as her husband’s cousin Princess Anton Radziwill watched Louise depart from Königsberg, lying down in her coach, barely able to wave a hand in farewell.42

What was the Queen doing at the war camp in the first place? The Duke of Brunswick, the Commander-in-Chief of the army, was appalled to find her there, on the scene of battle, in her little carriage. ‘What are you doing here, Madame? For God’s sake, what are you doing here?’ he exclaimed. Then he pointed at the fortress occupied by the French: ‘Tomorrow we will have a bloody decisive day.’ The Queen departed very early the next morning with the noise of the cannonades in her ears: already the French could distinctly perceive her amid the Prussian lines, and in the event missed capturing her by a mere hour. (Later the Queen would remark wryly that the Duke of Brunswick’s order to retreat was the first time she ever heard him express himself either positively or energetically.)43

Queen Louise’s official explanation for her presence was the King’s need of her support; Gentz at least accepted this, as did General Kalkreuth. She propped up the King’s waning confidence, he believed, and besides her presence had its usual encouraging effect on the soldiers. Kalkreuth’s reasoning was undoubtedly correct. Yet the grim truth was that on a battlefield, for the Prussians, King and soldiers alike, the encouragement of their goddess could avail little against the superior French. And a fancy-dress Warrior Queen, however patriotic, had little place there, when she might have been captured and given cause for still further exultation on the part of her enemies.

Queen Louise’s tribulations were not at an end with her flight to Memel. How freezing, how forlorn and how horribly crowded with refugees was beloved Memel now, compared to that sweet summer place where she had danced with the Tsar four years earlier! The Queen herself was ill most of the time. She was still recovering from typhus, while that combination of a weak heart and congestion of the lungs which would finally kill her was beginning to take its toll. Diplomatic negotiations to save something for Prussia from the wreck of its defeat caused her further anguish, as the Prussian King and his advisers struggled to conciliate France while not antagonizing Russia. Perhaps the Queen derived some ironic amusement from her riposte to the hated French Marshal Bertrand who asked her to use her influence to bring about a proper peace between France and Prussia. ‘Women have no voice in the making of war and peace’, replied the Queen, with dignity. When Frederick William sent her a soldier’s pigtail, to indicate that the sacred but old-fashioned costume of the Prussian army was at last being modernized, Louise both laughed and wept. But by June tears were constantly dripping down the Queen’s cheeks, ‘despite her brave little games’ as the British envoy, Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, noted.44

Meanwhile the ‘Monster’, in the Queen’s own room at Weimar, gloated over the notes and reports which he found in her drawers, mixed with the other more delicate objects of her toilette, still perfumed by the musk which was used to scent them. ‘It seems as if what they say of her is true’, he noted. ‘She was here to fan the flames of war.’ Then he dismissed Louise as ‘a woman with a pretty face, but little intelligence and quite incapable of foreseeing the consequences of what she does’. He even managed a kind of compassion: ‘Now she is to be pitied rather than blamed, for she must be suffering agonies of remorse for all the evil she has done to her country and to her husband, who, everyone agrees, is an honourable man, wanting only the peace and welfare of his subjects.’45

But at the City Hall in Berlin, Napoleon ranted on concerning the excellent example of the Turks who kept women out of politics (shades of Voltaire’s salute to that ‘woman and a Christian’, Catherine the Great!) and would not listen to two elderly ecclesiastics who praised their queen’s kindness and goodness. When the wife of Prince Hatzfeld pleaded on her knees for her husband’s life, on the other hand, Napoleon was pleased to grant the request and issued a picture commemorating the incident; that presumably was the proper position for a woman. Queen Louise was already suffering furious humiliation at Napoleon’s insinuations concerning her relationship with the Tsar. She burst out in a letter otherwise written in French: ‘Und man lebt und kann die Schmach nicht rächen’ (And one lives and cannot take revenge for the humiliation).46 She was now further punished by the issue of a very different picture. At the tomb of Frederick the Great, in a caricature of that secret night visit and its vows depicted in the popular print, Louise was shown in the guise of Lady Hamilton to the Tsar’s Nelson. Since Lady Hamilton was then notorious in Europe as the late Nelson’s mistress, the implication was clear.

It was at this time that Queen Louise was traditionally supposed to have transcribed this harpist’s song (set by Schubert) from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, with its mournful quatrain:

Who never ate his bread in sorrow

Who never spent the darksome hours

Weeping and watching for the morrow

He knows ye not, ye heavenly powers!47

But the greatest humiliation lay ahead. Its prelude was another crushing defeat: that of the Russian army under General Bennigsen at Friedland, twenty-seven miles south of Königsberg, on 15 June 1807. A week later it was the Tsar Alexander’s turn to negotiate a truce. This was the prayer of Louise to Alexander before the battle: ‘You are our only hope: do not abandon us, not for my sake, but for my husband’s sake, for the sake of my children, their future and their destiny.’ Her prayer would go for nothing compared to the crudeness of Realpolitik. Louise’s ‘only hope’ was indeed about to abandon them, as she would shortly discover.

At Tilsit, while the Emperor Napoleon of France and the Tsar Alexander of Russia met on an island in the middle of the river, King Frederick William of Prussia was condemned to await their summons standing in the pouring rain, on the shore. His unhappy stance perfectly illustrated the comment of the Austrian Prince Metternich: at Tilsit Prussia descended from the first rank ‘to be ranged among powers of the Third Order’.48 What was Prussia’s fate likely to be – what territorial sacrifices, what financial reparations would be demanded at a treaty negotiated under such unpromising circumstances?

It was at this point that someone at the Prussian court, convinced that the Queen’s ‘fascinating affability’ would win over ‘this Monster vomited from hell’ (the King’s phrase on this occasion), had the idea of sending for Louise. One German biographer suggests that it was Hardenberg and General Kalkreuth who decided to use the Queen. Another name proposed is that of Murat, working on Frederick William. But on the French side Talleyrand was certainly very much against it and, accepting Louise’s putative powers as an enchantress, enquired of Napoleon angrily: ‘Sire, will you jeopardize your greatest conquest for a pair of beautiful eyes?’49

We know from the testimony of those young British diplomats stationed at Memel – all of them half in love with the Queen – how reluctant she was to go. Her health alone might have precluded such an ordeal. To the King, however, Louise wrote that her arrival would be a proof of her love for him: for as she confided to her diary, ‘this burden is demanded’, whatever it might cost her to be pleasant and courteous towards Napoleon.50 Louise was condemned to the ‘burden’ by the romantic Prussian belief, which she herself obviously shared, that she could succeed where male diplomacy failed. Furthermore, hopeful signs elicited, as it seemed, from the ‘Monster’ only underlined the general atmosphere of expectation: he drank the Queen’s health and asked with some tenderness after her family’s welfare.

Perhaps it was as well that the Prussian courtiers could not read Napoleon’s reassuring letter to Josephine on the subject of the Prussian Queen’s ‘coquetting’: ‘I am like cere-cloth, along which everything of this sort slides without penetrating. It would cost me too dear to play the gallant on this subject.’ The Queen herself might have been more affronted by the merry gossip of the time in London where bets were being taken on whether she would get Napoleon to fall in love with her. The playwright Sheridan took, on the other hand, the cynical line that Louise would fall in love with Napoleon: from an empress to a housemaid, ‘all women are dazzled by glory, and sure to be in love with a Man whom they begin by hating and who has treated them ill …’.51

In the event what happened satisfied neither the optimists, the romantics nor the cynics. The Queen arrived in Tilsit on 6 July.52 Napoleon behaved extremely courteously all along, ending dinner especially early out of regard for her delicate health. When the Queen gently taxed him, ‘Sire, I know you accuse me of meddling in politics’, Napoleon responded gallantly, ‘Ah, Madame, you must not believe that I listen only to malicious gossip’ (thus splendidly ignoring the subject of his own Bulletins of the Army). Nor did Louise herself find the ‘Monster’ as odious as she had expected (although she certainly did not fall in love with him).

But while Louise saw it as her role to plead with him, as the traditional Queen-in-distress – ‘I am a wife and mother and it is by these titles that I appeal for your mercy on behalf of Prussia’ – Napoleon responded blandly with compliments on her white embroidered crêpe de Chine dress made in Breslau, and the superb collar she wore of her favourite pearls. After Louise’s death, Countess Voss would comment sadly on the Queen’s love of pearls, with their connotation of tears, as opposed to diamonds, which stood for prosperity; certainly there were tears enough to be shed on this occasion. Again and again the Queen tried to steer the conversation away from clothes back to the fate of Prussia itself. Privately, Napoleon rather admired her for her polite tenacity, how she always got back to her subject: ‘perhaps even too much so, and yet with perfect propriety and in a manner that aroused no antagonism’. He even went as far to admit that ‘In truth, the matter was an important one to her …’. Publicly, he would have none of it.

There is a celebrated story concerning the occasion following the dinner when Napoleon went to call on Louise in her Tilsit lodgings; like many celebrated stories which sum up the popular image of a particular character (or characters) – the story of Queen Jinga and her royal ‘chair’ is another noted example – it has several variants. It seems that the Queen pleaded with Napoleon to exclude certain Prussian possessions from the confiscation which was planned as part of the peace treaty. Those to be reallocated included all the Prussian territories west of the Elbe, not omitting Magdeburg itself, on the river, most of Prussian Poland (to be reconstituted as the Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw) and the Silesian fortresses. It is not known for certain exactly which provinces the Queen named to Napoleon, but attention has generally focused on Magdeburg.

The most colourful version of the story has Napoleon asking for a single rose from the Queen’s arrangement of flowers. In reply, the Queen asked for an exchange: ‘A rose for Magdeburg, Sire.’ Some biographers have found this behaviour on the part of the Queen to be uncharacteristically arch. In another version (which accords better with Napoleon’s own description of Louise as relentless – but dignified – in pursuit of her aims) the Queen struck a tragic note more or less on Napoleon’s arrival: ‘Sire, Justice! Justice! Magdeburg! Magdeburg!’ There is no dispute however about the Queen’s lack of success in securing from Napoleon even the slightest diminution of the harsh terms imposed upon Prussia, including an enormous bill of financial reparation. (Ironically enough, her reproaches to the Tsar for abandoning them did move him guiltily to plead for an alleviation of the Prussian punishment;53 Louise, however, had been brought to Tilsit to woo Napoleon, not to reproach the Tsar.)

Everyone had been wrong: Frederick William, Hardenberg, General Kalkreuth, all those who had pinned their hopes on the ‘fascinating affability’ of their Queen. Three years before, seeing Louise dressed as Statira, wife of Alexander the Great (on that same occasion when she had struck Madame de Staël dumb with her beauty), Sir George Jackson had reflected that ‘our queen of beauty’ too would have conquered Alexander, ‘had the hero the happiness of seeing her’. But the Queen of beauty had not conquered the Alexander of the hour: Napoleon. Much later, on St Helena, Napoleon referred to her ‘winning ways’ as well as her attempts to win him over. The Queen on the other hand wept bitterly and continuously afterwards, according to Countess Voss, referring over and over again to her ‘deception’ and reading her favourite Schiller (The Thirty Years’ War) for comfort. ‘In that house’, she told one of the young Englishmen at Memel, referring to Tilsit, ‘I was cruelly deceived.’54 Napoleon had become once more the ‘Monster’, ‘this inhuman being’ who must be beaten down for the sake of the future of Prussia, of her husband and of her children.

Queen Louise did not survive to see the ‘Monster’ beaten down, although Frederick William did. She died of a pulmonary embolism in July 1810, having given birth to two more children, on 1 February 1808 – she must have been once again in the early stages of pregnancy at Tilsit – and 4 October 1809. But it was widely thought that she had died of a broken heart, to which her humiliation at Tilsit, symbolizing the humiliation of Prussia, had contributed. Her last years were marked by the inevitable sorrow of Prussia’s grievous political situation, as well as by her persistent attempts to bolster up Frederick William. Heinrich von Kleist gives a moving picture of her at this time: ‘She has developed a truly royal character … She, who a short time ago had nothing better to do than amuse herself with dancing or riding horseback, has gathered about her all our great men whom the King neglects and who alone can bring us salvation. Yes, it is she who sustains what has not collapsed.’55

The Queen also made earnest attempts to study history – Hume, Robertson and Gibbon – as though to try to make sense of the great if tragic events she had lived through. As with the whole of Louise’s brief life – she was thirty-four when she died – there is a touching quality about the enterprise. ‘I am so stupid and I hate the stupidity’, she exclaimed. ‘What was the Punic War? Was it against Carthage? Who were the Gracchi and what were their troubles? What does hierarchy mean?’ Even here, patriotism was never forgotten: Louise admired Theodoric for instance as ‘a genuine German’, with his love of justice, his upright character and his magnanimity.56

Like Queen Jinga of Angola, however – albeit a very different kind of Warrior Queen – Queen Louise of Prussia was to have another whole life as a national heroine, far more enduring than her actual life on earth. To the grieving King, she quickly became his ‘sainted Louise’, while he was always firm against charges of political interference: she had ‘never quitted her own sphere of feminine usefulness’. Her popularity with the army was deliberately invoked when he instituted the order of the Iron Cross for military valour on the anniversary of her birth in 1813. (The Luisenorde for ladies, on the other hand, instituted on his own birthday – ‘we are determined to do honour to the female sex’ – concentrated on women who relieved suffering, not warriors; and the medal showed the late Queen in silver on a pale blue background, with a crown of stars – not in military uniform). When the ‘Monster’ was despatched to Elba, a hymn was composed in the Queen’s honour beginning: ‘Oh Saint in bliss … Thy tears are dried at last’ and ending with the refrain:

Louise, the protectress of our right,

Louise, still the watchword of our fight.57

Classically, the ordinary soldiers in the Prussian army refused to believe in their beloved Queen’s death for years afterwards; as for the rest of the nation, Princess Anton Radziwill wrote that twenty-five years later ‘still the same regrets are given to the memory of that angel of goodness!’ And an English author, Mrs Charles Richardson, who toured Prussia in the 1840s, subsequently dedicating her biography of Louise to Queen Victoria as another one distinguished ‘for pre-eminence in female excellence’, found many local traditions of the Queen as a guardian angel in time of war, ‘a lovely vision’ who appeared and then disappeared back to heaven.58

Nor did the cult of the holy and patriotic Warrior Queen stop there. Queen Louise may claim to have possessed a genuine sense of Prussia’s importance as part of the German whole: she was not after all born a Prussian, and throughout Prussia’s troubles retained a conviction that its triumph or defeat should be seen as affecting Germany itself (her remark concerning Theodoric was not uncharacteristic). It was therefore not inappropriate that in the late nineteenth century, continuing into the twentieth, she should come to be regarded as the Holy (departed) Figurehead of the resurgent and mighty Prussian-led Germany. On the sixtieth anniversary of her death, 19 July 1870, her son, then still King William of Prussia, went to pray at her grave; this was the day on which war was declared against France, that war from which he would return as German Emperor. Louise’s son was convinced that he had thus fulfilled her dearest dreams and hopes, she who could be viewed ‘as a martyr to her love for the Fatherland’.59

The Queen’s verdict on herself was both more modest and more poignant.60 ‘If posterity will not place my name amongst those of celebrated women [she might have instanced Maria Theresa or Catherine the Great] yet those who were acquainted with the troubles of these times, will know what I have gone through and will say “She suffered much and endured with patience”.’