A EUROPEAN SUMMER: LICHFIELD AND WARWICK

June 11, 1872

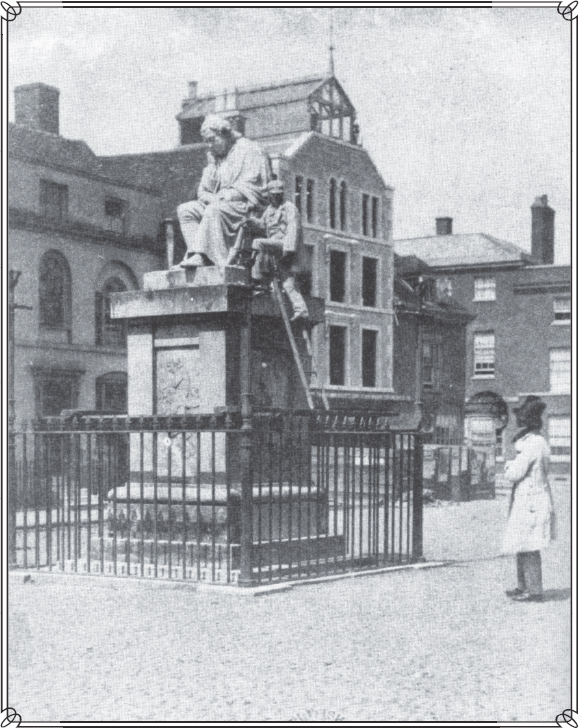

The Samuel Johnson statue in Lichfield, with the artist, 1859.

TO WRITE AT OXFORD OF ANYTHING BUT OXFORD REQUIRES, on the part of the sentimental tourist, no small power of mental abstraction. Yet I have it at heart to pay to three or four other scenes recently visited the debt of an enjoyment hardly less profound than my relish for this scholastic paradise. First among these is the cathedral city of Lichfield. I say the city, because Lichfield has a character of its own apart from its great ecclesiastical feature. In the centre of its little market-place—dullest and sleepiest of provincial market-places—rises a huge effigy of Dr. Johnson, the genius loci, who was constructed, humanly, with very nearly as large an architecture as the great abbey. The doctor’s statue, which is of some plaster-like compound, painted a shiny brown, and of no great merit of design, fills out the vacant dulness of the little square in much the same way as his massive personality occupies—with just a margin for Garrick—the record of his native town. In one of the volumes of Croker’s “Boswell” is a steel plate of the old Johnsonian birth-house, by the aid of a vague recollection of which I detected the dwelling beneath its modernized frontage. It bears no mural inscription, and, save for a hint of antiquity in the receding basement, with pillars supporting the floor above, seems in no especial harmony with Johnson’s time or fame. Lichfield in general appeared to me, indeed, to have little to say about her great son, beyond the fact that the dreary provincial quality of the local atmosphere, in which it is so easy to fancy a great intellectual appetite turning sick with inanition, may help to explain the doctor’s subsequent, almost ferocious, fondness for London. I walked about the silent streets, trying to repeople them with wigs and short clothes, and, while I lingered near the cathedral, endeavored to guess the message of its Gothic graces to Johnson’s ponderous classicism. But I achieved but a colorless picture at the best, and the most vivid image in my mind’s eye was that of the London Coach facing towards Temple Bar, with the young author of “Rasselas” scowling nearsightedly from the cheapest seat. With him goes the interest of Lichfield town. The place is stale, without being really antique. It is as if that prodigious temperament had absorbed and appropriated its original vitality.

If every dull provincial town, however, formed but a girdle of quietude to a cathedral as rich as that of Lichfield, one would thank it for its unimportunate vacancy. Lichfield Cathedral is great among churches, and bravely performs the prime duty of a cathedral—that of seeming for the time (to minds unsophisticated by architectural culture) the finest, on the whole, of all cathedrals. This one is rather oddly placed, on the slope of a hill, the particular spot having been chosen, I believe, because sanctified by the sufferings of certain primitive martyrs; but it is fine to see how its upper portions surmount any crookedness of posture, and its great towers overtake in mid-air the conditions of perfect symmetry.

The close is a singularly pleasant one. A long sheet of water expands behind it, and, besides leading the eye off into a sweet green landscape, renders the inestimable service of reflecting the three spires as they rise above the great trees which mask the Palace and the Deanery. These august abodes cope the northern side of the slope, and stand back behind huge gateposts and close-wrought gates which seem to enclose a sort of Georgian atmosphere. Before them stretches a row of huge elms, which must have been old when Johnson was young; and between these and the long-buttressed wall of the cathedral, you may stroll to and fro among as pleasant a mixture of influences (I imagine) as any in England. You can stand back here, too, from the west front further than in many cases, and examine at your ease its lavish decoration. You are, perhaps, a trifle too much at your ease; for you soon discover what a more cursory glance might not betray, that the immense façade has been covered with stucco and paint, that an effigy of Charles II, in wig and plumes and trunk-hose, of almost Gothic grotesqueness, surmounts the middle window; that the various other statues of saints and kings have but recently climbed into their niches; and that the whole expanse, in short, is a pastiche. All this was done some fifty years ago, in the taste of that day as to restoration, and yet it but partially mitigates the impressiveness of the high façade, with its brace of spires, and the great embossed and image-fretted surface, to which the lowness of the portals (the too frequent reproach of English abbeys) seems to give a loftier reach. Passing beneath one of these low portals, however, I found myself gazing down as noble a church vista as any I remember. The Cathedral is of magnificent length, and the screen between nave and choir has been removed, so that from stem to stern, as we may say, of the great vessel of the church, it is all a mighty avenue of multitudinous slender columns, terminating in what seems a great screen of ruby and sapphire and topaz—one of the finest east windows in England. The Cathedral is narrow in proportion to its length; it is the long-drawn aisle of the poet in perfection, and there is something grandly elegant in the unity of effect produced by this undiverted perspective. The charm is increased by a singular architectural phantasy. Standing in the centre of the doorway, you perceive that the eastern wall does not directly face you, and that from the beginning of the choir the receding aisle deflects slightly to the left—in suggestion of the droop of the Saviour’s head on the cross. Here, as elsewhere, Mr. Gilbert Scott has recently been at work—to excellent purpose, from what the sacristan related of the barbarous encroachments of the last century. This extraordinary period expended an incalculable amount of imagination in proving that it had none. Universal whitewash was the least of its offences. But this has been scraped away, and the solid stonework left to speak for itself—the delicate capitals and cornices disencrusted and discreetly rechiselled, and the whole temple aesthetically rededicated. Its most beautiful feature, happily, has needed no repair, for its perfect beauty has been its safeguard. The great choir window of Lichfield is the noblest glass-work I remember to have seen. I have met nowhere colors so chaste and grave, and yet so rich and true, nor a cluster of designs so piously decorative, and yet so pictorial. Such a window as this seems to me the most sacred ornament of a great church—to be, not like vault and screen and altar, the dim contingent promise of heaven, but the very assurance and presence of it. This Lichfield glass is not the less interesting for being visibly of foreign origin. Exceeding so obviously as it does the range of English genius in this line, it indicates at least the heavenly treasure stored up in continental churches. It dates from the early sixteenth century, and was transferred hither sixty years ago from the suppressed abbey of Heckenroode, in Belgium. This, however, is not all of Lichfield. You have not seen it till you have strolled and restrolled along the close on every side, and watched the three spires constantly change their relation as you move and pause. Nothing can well be finer than the combination of the two lesser ones soaring equally in front, and the third riding tremendously the magnificently sustained line of the roof. At a certain distance against the sky, this long ridge seems something infinite, and the great spire to sit astride of it like a giant mounted on a mastodon. Your sense of the huge mass of the building is deepened by the fact that though the central steeple is of double the elevation of the others, you see it, from some points, borne back in a perspective which drops it to half their stature, and lifts them into immensity. But it would take long to tell all that one sees and fancies and thinks in a lingering walk about so great a church as this. There are few deeper pleasures than such a contemplative stroll.

To walk in quest of any object that one has more or less tenderly dreamed of—to find your way—to steal upon it softly—to see at last, if it is church or castle, the tower-tops peeping above elms or beeches—to push forward with a rush, and emerge, and pause, and draw that first long breath which is the compromise between so many sensations—this is a pleasure left to the tourist even after the broad glare of photography has dissipated so many of the sweet mysteries of travel—even in a season when he is fatally apt to meet a dozen fellow-pilgrims returning from the shrine, each gros Jean comme devant, or to overtake a dozen more, telegraphing their impressions down the line as they arrive. Such a pleasure I lately enjoyed, quite in its perfection, in a walk to Haddon Hall, along a meadow-path by the Wye, in this interminable English twilight, which I am never weary of admiring, watch in hand. Haddon Hall lies among Derbyshire hills, in a region infested, I was about to write, by Americans. But I achieved my own sly pilgrimage in perfect solitude; and as I descried the gray walls among the rook-haunted elms, I felt not like a tourist, but like an adventurer. I have certainly had, as a tourist, few more charming moments than some—such as any one, I suppose, is free to have—that I passed on a little ruined gray bridge which spans, with its single narrow arch, a trickling stream at the base of the eminence from which those walls and trees look down. The twilight deepened, the ragged battlements and the low, broad oriels glanced duskily from the foliage, the rooks wheeled and clamored in the glowing sky, and if there had been a ghost on the premises, I certainly ought to have seen it. In fact, I did see it, as we see ghosts nowadays. I felt the incommunicable spirit of the scene with almost painful intensity. The old life, the old manners, the old figures seemed present again. The great coup de théâtre of the young woman who shows you the Hall—it is rather languidly done on her part—is to point out a little dusky door opening from a turret to a back terrace as the aperture through which Dorothy Vernon eloped with Lord John Manners. I was ignorant of this episode, for I was not to enter the Hall till the morrow; and I am still unversed in the history of the actors. But as I stood in the luminous dusk weaving the romance of the spot, I divined Dorothy Vernon, and felt very much like a Lord John. It was, of course, on just such an evening that the delicious event came off, and, by listening with the proper credulity, I might surely hear on the flags of the castle-court the ghostly foot-fall of a daughter of the race. The only footfall I can conscientiously swear to, however, is the by no means ghostly tread of the damsel who led me through the mansion in the prosier light of the next morning. Haddon Hall, I believe, is one of the places in which it is the fashion to be “disappointed”; a fact explained in a great measure by the absence of a formal approach to the house, which shows its low, gray front to every trudger on the high-road. But the charm of the place is so much less that of grandeur than that of melancholy, that it is rather deepened than diminished by this attitude of obvious survival and decay. And for that matter, when you have entered the steep little outer court through the huge thickness of the low gateway, the present seems effectually walled out, and the past walled in—like a dead man in a sepulchre. It is very dead, of a fine June morning, the genius of Haddon Hall; and the silent courts and chambers, with their hues of ashen gray and faded brown, seem as time-bleached as the dry bones of any mouldering organism. The comparison is odd; but Haddon Hall reminded me perversely of some of the larger houses at Pompeii. The private life of the past is revealed in each case with very much the same distinctness and on a small enough scale not to stagger the imagination. This old dwelling, indeed, has so little of the mass and expanse of the classic feudal castle that it almost suggests one of those miniature models of great buildings which lurk in dusty corners of museums. But it is large enough to be deliciously complete and to contain an infinite store of the poetry of grass-grown courts looked into by long, low oriel casements, and climbed out of by crooked stone stairways, mounting against the walls to little high-placed doors. The “tone” of Haddon Hall, of all its walls and towers and stonework, is the gray of unpolished silver, and the reader who has been in England need hardly be reminded of the sweet accord—to eye and mind alike—existing between all stony surfaces covered with the real white rust of time and the deep living green of the strong ivy which seems to feed on their slow decay. Of this effect and of a hundred others—from those that belong to low-browed, stone-paved empty rooms, where countesses used to trail their cloth-of-gold over rushes, to those one may note where the dark tower stairway emerges at last, on a level with the highest beech-tops, against the cracked and sunbaked parapet, which flaunted the castle standard over the castle walls—of every form of sad desuetude and picturesque decay Haddon Hall contains some delightful examples. Its finish point is undoubtedly a certain court from which a stately flight of steps ascends to the terrace where that daughter of the Vernons whom I have mentioned proved that it was useless to have baptized her so primly. These steps, with the terrace, its balustrade topped with great ivy-muffled knobs of stone, and its vast background of lordly beeches, form the ideal mise en scène for portions of Shakespeare’s comedies. “It’s Elizabethan,” said my companion. Here the Countess Olivia may have listened to the fantastic Malvolio, or Beatrix, superbest of flirts, have come to summon Benedick to dinner.

The glories of Chatsworth, which lies but a few miles from Haddon, serve as a fine repoussoir to its more delicate merits, just as they are supposed to gain, I believe, in the tourist’s eyes, by contrast with its charming, its almost Italian shabbiness. But the glories of Chatsworth, incontestable as they are, were so effectually eclipsed to my mind, a couple of days later, that in future, when I think of an English mansion, I shall think only of Warwick, and when I think of an English park, only of Blenheim. Your run by train through the gentle Warwickshire landscape does much to prepare you for the great spectacle of the castle, which seems hardly more than a sort of massive symbol and synthesis of the broad prosperity and peace and leisure diffused over this great pastoral expanse. The Warwickshire meadows are to common English scenery what this is to that of the rest of the world. For mile upon mile you can see nothing but broad sloping pastures of velvet turf, overbrowsed by sheep of the most fantastic shagging, and ornamented with hedges out of the trailing luxury of whose verdure, great ivy-tangled oaks and elms arise with a kind of architectural regularity. The landscape, indeed, sins by excess of nutritive suggestion; it savors of the larder; it is too ovine, too bovine, too succulent, and if you were to believe what you see before you, this rugged globe would be a sort of boneless ball, neatly covered with some such plush-like integument as might be figured by the down on the cheek of a peach. But a great thought keeps you company as you go and gives character to the scenery. Warwickshire was Shakespeare’s country. Those who think that a great genius is something supremely ripe and healthy, and human, may find comfort in the fact. It helps materially to complete my own vague conception of Shakespeare’s temperament, with which I find it no great shock to be obliged to associate ideas of mutton and beef. There is something as final, as disillusioned of the romantic horrors of rock and forest, as deeply attuned to human needs, in the Warwickshire pastures, as there is in the underlying morality of the poet.

With human needs in general, Warwick Castle may be in no great accord, but few places are more gratifying to the sentimental tourist. It is the only great residence that I ever coveted as a home. The fire that we heard so much of last winter in America appears to have consumed but an inconsiderable and easily-spared portion of the house, and the great towers rise over the great trees and the town with the same grand air as before. Picturesquely, Warwick gains from not being sequestered, after the common fashion, in acres of park. The village-street winds about the garden walls, though its hum expires before it has had time to scale them. There can be no better example of the way in which stone-walls, if they do not of necessity make a prison, may on occasions make a palace, than the tremendous privacy maintained thus about a mansion whose windows and towers form the main feature of a bustling town. At Warwick the past joins hands so stoutly with the present that you can hardly say where one begins and the other ends, and you rather miss the various crannies and gaps of what I just now called the Italian shabbiness of Haddon. There is a Caesar’s tower and a Guy’s tower and half a dozen more, but they are so well-conditioned in their ponderous antiquity that you are at loss whether to consider them parts of an old house revived or of a new house picturesquely superannuated. Such as they are, however, plunging into the grassed and gravelled courts from which their battlements look really feudal, and into gardens large enough for all delight and too small, as they should be, to be amazing; and with ranges between them of great apartments at whose hugely recessed windows you may turn from Van Dyke and Rembrandt, to glance down the cliff-like pile into the Avon, washing the base like a lordly moat, with its bridge, and its trees, and its memories—they mark the very model of a great hereditary dwelling—one which amply satisfies the imagination without irritating the conscience. The pictures at Warwick reminded me afresh of an old conclusion on this matter, that the best fortune for good pictures is not to be crowded into public collections—not even into the relative privacy of Salons carrés and Tribunes, but to hang in largely-spaced half-dozens on the walls of fine houses. Here the historical atmosphere, as one may call it, is almost a compensation for the often imperfect light. If this is true of most pictures, it is especially so of the works of Van Dyke, whom you think of, wherever you may find him, as having, with that immense good-breeding which is the stamp of his manner, taken account in his painting of the local conditions, and predestined his picture to just the spot where it hangs. This is, in fact, an illusion as regards the Van Dykes at Warwick, for none of them represent members of the house. The very finest, perhaps, after the great melancholy, picturesque Charles I.—death, or at least the presentiment of death on the pale horse—is a portrait from the Brignole palace at Genoa, a beautiful noble matron in black, with her little son and heir. The last Van Dykes I had seen were the noble company this lady had left behind her in the Genoese palace, and as I looked at her, I thought of her mighty change of circumstance. Here she sits in the mild light of Midmost England; there you could almost fancy her blinking in the great glare sent up from the Mediterranean. Picturesque for picturesque, I should hardly know which to choose.