A EUROPEAN SUMMER: NORTH DEVON

July 1872

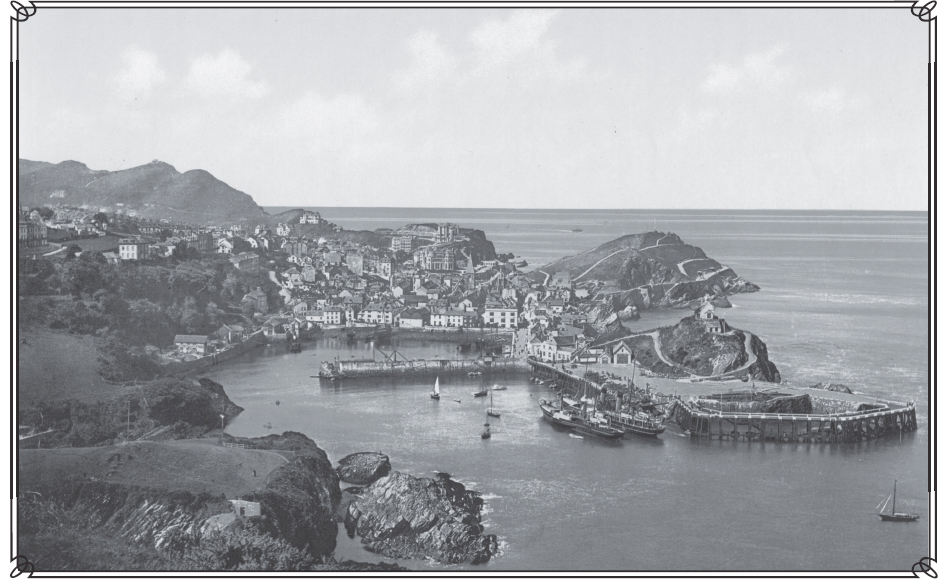

Illsborough, Ilfracombe, England, ca. 1890.

FOR THOSE FANCIFUL OBSERVERS TO WHOM BROAD ENGLAND means chiefly the perfection of the rural picturesque, Devonshire means the perfection of England. I, at least, had so complacently taken it for granted that all the characteristic graces of English scenery are here to be found in especial exuberance that before we fairly crossed the borders I had begun to look impatiently from the carriage window for the veritable landscape in watercolors. Devonshire meets you promptly in all its purity. In the course of ten minutes you have been able to glance down the green vista of a dozen Devonshire lanes. On huge embankments of moss and turf, smothered in wild-flowers and embroidered with the finest lace-work of trailing ground-ivy, rise solid walls of flowering thorn and glistening holly and golden broom, and more strong, homely shrubs than I can name, and toss their blooming tangle to a sky which seems to look down between them in places from but a dozen inches of blue. They are over-strewn with lovely little flowers with names as delicate as their petals of gold and silver and azure—bird’s-eye and ring’s-finger and wandering-sailor—and their soil, a superb dark red, turns in spots so nearly to crimson that you almost fancy it some fantastic compound purchased at the chemist’s and scattered there for ornament. The mingled reflection of this rich-hued earth and the dim green light which filters through the hedge, forms an effect to challenge the skill of the most accomplished watercolorist. A Devonshire cottage is no less striking a local “institution.” Crushed beneath its burden of thatch, coated with a rough white stucco, of a tone to delight a painter, nestling in deep foliage, and garnished at doorstep and wayside with various forms of chubby infancy, it seems to have been stationed there for no more obvious purpose than to keep a promise to your fancy, though it covers, I suppose, not a little of the sordid misery which the fancy loves to forget. I rolled past lanes and cottages to Exeter, where I found a cathedral. When one has fairly tasted of the pleasure of cathedral-hunting, the approach to each new shrine gives a peculiarly agreeable zest to one’s curiosity. You are making a collection of great impressions, and I think the process is in no case so delightful as applied to cathedrals. Going from one fine picture to another is certainly good, but the fine pictures of the world are terribly numerous, and they have a troublesome way of crowding and jostling each other in the memory. The number of cathedrals is small, and the mass and presence of each specimen is great, so that, as they rise in the mind in individual majesty, they dwarf all common impressions. They form, indeed, but a gallery of vaster pictures; for, when time has dulled the recollection of details, you retain a single broad image of the vast gray edifice, with its towers, its tone of color, and its still, green precinct. All this is especially true, perhaps, of one’s memory of English cathedrals, which are almost alone in possessing, as pictures, the setting of a spacious and harmonious Close. The Cathedral stands supreme, but the Close makes the scene. Exeter is not one of the grandest, but, in common with great and small, it has certain points on which local learning expatiates with peculiar pride. Exeter, indeed, does itself injustice by a low, dark front, which not only diminishes the apparent altitude of the nave, but conceals, as you look eastward, two noble Norman towers. The front, however, which has a gloomy picturesqueness, is redeemed by two fine features: a magnificent rose-window, whose vast stone ribs (enclosing some very pallid last-century glass) are disposed with the most charming intricacy; and a long sculptured screen—a sort of stony band of images—which traverses the façade from side to side. The little broken-visaged effigies of saints and kings and bishops niched in tiers along this hoary wall are prodigiously black and quaint and primitive in expression, and as you look at them with whatever contemplative tenderness your trade of hard-working tourist may have left at your disposal, you fancy that somehow they are consciously historical—sensitive victims of time; that they feel the loss of their noses, their toes, and their crowns; and that, when the long June twilight turns at last to a deeper gray, and the quiet of the Close to a deeper stillness, they begin to peer sidewise out of their narrow recesses, and to converse in some strange form of early English, as rigid, yet as candid, as their features and postures, moaning, like a company of ancient paupers round a hospital fire, over their aches and infirmities and losses, and the sadness of being so terribly old. The vast square transeptal towers of the church seem to me to have the same sort of personal melancholy. Nothing in all architecture expresses better, to my imagination, the sadness of survival, the resignation of dogged material continuance, than a broad expanse of Norman stonework, roughly adorned with its low relief of short columns, and round arches, and almost barbarous hatchet-work, and lifted high into that mild English light which accords so well with its dull-gray surface. The especial secret of the impressiveness of such a Norman tower I cannot pretend to have discovered; it lies largely in the look of having been proudly and sturdily built—as if the masons had been urged by a trumpet-blast, and the stones squared by a battle-axe—contrasted with this mere idleness of antiquity and passive lapse into quaintness. A Greek temple preserves a kind of fresh immortality in its concentrated refinement, and a Gothic cathedral in its adventurous exuberance; but a Norman tower stands up like some simple strong man in his might, bending a melancholy brow upon an age which demands that strength shall be cunning.

The North Devon coast, whither it was my design on coming to Exeter to proceed, has the primary merit of being, as yet, virgin soil as to railways. I went accordingly from Barnstaple to Ilfracombe on the top of a coach, in the fashion of elder days; and, thanks to my position, I managed to enjoy the landscape in spite of the two worthy Englishmen before me who were reading aloud together, with a natural glee which might have passed for fiendish malice, the Daily Telegraph’s painfully vivid account of the defeat of the Atalanta crew. It seemed to me, I remember, a sort of pledge and token of the invincibility of English muscle that a newspaper record of its prowess should have power to divert my companions’ eyes from the bosky flanks of Devonshire combes. The little watering-place of Ilfracombe is seated at the lower verge of one of the seaward-plunging valleys, between a couple of magnificent headlands which hold it in a hollow slope and offer it securely to the caress of the Bristol Channel. It is a very finished little specimen of its genus, and I think that during my short stay there, I expended as much attention on its manners and customs and its social physiognomy as on its cliffs and beach and great coast-view. My chief conclusion, perhaps, from all these things, was that the terrible summer question which works annual anguish in so many American households would be vastly simplified if we had a few Ilfracombes scattered along our Atlantic coast; and furthermore, that the English are masters of the art of uniting the picturesque with the comfortable—in such proportions, at least, as may claim the applause of a race whose success has as yet been confined to an ingenious combination of their opposites. It is just possible that at Ilfracombe the comfortable weighs down the scale; so very substantial is it, so very officious and business-like. On the left of the town (to give an example), one of the great cliffs I have mentioned rises in a couple of massive peaks, and presents to the sea an almost vertical face, all veiled in tufts of golden brown and mighty fern. You have not walked fifty yards away from the hotel before you encounter half a dozen little signboards, directing your steps to a path up the cliff. You follow their indications, and you arrive at a little gate-house, with photographs and various local gimcracks exposed for sale. A most respectable person appears, demands a penny, and, on receiving it, admits you with great civility to commune with nature. You detect, however, various little influences hostile to perfect communion. You are greeted by another signboard threatening legal pursuit if you attempt to evade the payment of the sacramental penny. The path, winding in a hundred ramifications over the cliff, is fastidiously solid and neat, and furnished at intervals of a dozen yards with excellent benches, inscribed by knife and pencil with the names of such visitors as do not happen to have been the elderly maiden ladies who now chiefly occupy them. All this is prosaic, and you have to subtract it in a lump from the total impression before the sense of pure nature becomes distinct. Your subtraction made, a great deal assuredly remains; quite enough, I found, to give me an ample day’s entertainment, for English scenery, like everything else that England produces, is of a quality that wears well. The cliffs are superb, the play of light and shade upon them a perpetual study, and the air a delicious mixture of the mountain-breeze and the sea-breeze. I was very glad at the end of my climb to have a good bench to sit upon—as one must think twice in England before measuring one’s length on the grassy earth; and to be able, thanks to the smooth footpath, to get back to the hotel in a quarter of an hour. But it occurred to me that if I were an Englishman of the period, and, after ten months of a busy London life, my fancy were turning to a holiday, to rest, and change, and oblivion of the ponderous social burden, it might find rather less inspiration than needful in a vision of the little paths of Ilfracombe, of the signboards and the penny-fee and the solitude tempered by old ladies and sheep. I wondered whether change perfect enough to be salutary does not imply something more pathless, more idle, more unreclaimed from that deep-bosomed Nature to which the overwrought mind reverts with passionate longing; something in short which is attainable at a moderate distance from New York and Boston. I must add that I cannot find in my heart to object, even on grounds the most aesthetic, to the very beautiful and excellent hotel at Ilfracombe, where such of my readers as are perchance actually wrestling with the summer question may be interested to learn that one may live en pension, very well indeed, at a cost of ten shillings a day. I have paid very much more at some of our more modest summer resorts for very much less. I made the acquaintance at this establishment of that somewhat anomalous institution, the British table d’hôte, but I confess that, faithful to the duty of a sentimental tourist, I have retained a more vivid impression of the talk and the faces than of our entrées and relevés. I noticed here what I have often noticed before (the fact perhaps has never been duly recognized), that no people profit so eagerly as the English by the suspension of a common social law. A table d’hôte, being something abnormal and experimental, as it were, it produced, apparently, a complete reversal of the national characteristics. Conversation was universal—uproarious, almost; and I have met no vivacious Latin more confidential than a certain neighbor of mine; no speculative Yankee more inquisitive.

These are meagre memories, however, compared with those which cluster about that enchanting spot which is known in vulgar prose as Lynton. I am afraid I should seem an even more sentimental tourist than I pretend to be if I were to declare how vulgar all prose appears to me applied to Lynton with descriptive intent. The little village is perched on the side of one of the great mountain cliffs with which this whole coast is adorned, and on the edge of a lovely gorge through which a broad hill-torrent foams and tumbles from the great moors whose heather-crested waves rise purple along the inland sky. Below it, close beside the beach, where the little torrent meets the sea, is the sister village of Lynmouth. Here—as I stood on the bridge that spans the stream and looked at the strong backs and foundations and overclambering garden verdure of certain little gray old houses which plunge their feet into it, and then up at the tender green of scrub-oak and ferns and the flaming yellow of golden broom climbing the sides of the hills, and leaving them bare-crowned to the sun, like miniature mountains—I could have fancied the British Channel as blue as the Mediterranean and the village about me one of the hundred hamlets of the Riviera. The little Castle hotel at Lynton is a spot so consecrated to delicious repose—to sitting with a book in the terrace garden among blooming plants of aristocratic magnitude and rarity, and watching the finest piece of color in all nature—the glowing red and green of the great cliffs beyond the little harbor-mouth, as they shift and change and melt the livelong day, from shade to shade and ineffable tone to tone—that I feel as if in helping it to publicity I were doing it rather a disfavor than a service. It is in fact a very charming little abiding-place, and I have never known one where purchased hospitality wore a more disinterested smile. Lynton is of course a capital centre for excursions, but two or three of which I had time to make. None is more beautiful than a simple walk along the running face of the cliffs to a singular rocky eminence where curious abutments and pinnacles of stone have caused it to be named the “Castle.” It has a fantastic resemblance to some hoary feudal ruin, with crumbling towers and gaping chambers, tenanted by wild sea-birds. The late afternoon light had a way, while I was at Lynton, of lingering on until within a couple of hours of midnight, and I remember among the charmed moments of English travel none of a more vividly poetical tinge than a couple of evenings spent on the summit of this all but legendary pile, in company with the slow-coming darkness, and the short, sharp cry of the sea-mews. There are places whose very aspect is a story. This jagged and pinnacled crust-wall, with the rock-strewn valley behind it, into the shadow of one of whose boulders, in the foreground, the glance wandered in search of the lurking signature of Gustave Doré, belonged certainly, if not to history, to legend. As I sat watching the sullen calmness of the unbroken tide at the dreadful base of the cliffs (where they divide into low sea-caves, making pillars and pedestals for the fantastic imagery of their summits), I kept for ever repeating, as if they contained a spell, half a dozen words from Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King”:

“On wild Tintagil, by the Cornish Sea.”

False as they were to the scene geographically, they seemed somehow to express its essence; and, at any rate, I leave it to any one who has lingered there with the lingering twilight to say whether you can respond to the almost mystical picturesqueness of the place better than by spouting some sonorous line from an English poet.

The last stage in my visit to North Devon was the long drive along the beautiful remnant of coast and through the rich pastoral scenery of Somerset. The whole broad spectacle that one dreams of viewing in a foreign land, to the homely music of a post-boy’s whip, I saw on this admirable drive—breezy highlands clad in the warm blue-brown of heather-tufts, as if in mantles of rusty velvet, little bays and coves curving gently to the doors of clustered fishing-huts, deep pastures and broad forests, villages thatched and trellised as if to take a prize for local color, manor-tops peeping over rook-haunted avenues. I ought to make especial note of an hour I spent at mid-day at the little village of Porlock, in Somerset. Here the thatch seemed steeper and heavier, the yellow roses on the cottage walls more cunningly mated with the crumbling stucco, the dark interiors within the open doors more quaintly pictorial, than elsewhere; and as I loitered, while the horses rested, in the little cool old timber-steepled, yew-shaded church, betwixt the grim-seated manorial pew and the battered tomb of a crusading knight and his lady, and listened to the simple prattle of a blue-eyed old sexton, who showed me where, as a boy, in scantier corduroys, he had scratched his name on the recumbent lady’s breast, it seemed to me that this at last was old England indeed, and that in a moment more I should see Sir Roger de Coverley marching up the aisle; for certainly, to give a proper account of it all, I should need nothing less than the pen of Mr. Addison.