A EUROPEAN SUMMER: WELLS AND SALISBURY

August 1872

THE PLEASANTEST THINGS IN LIFE, AND PERHAPS THE RAREST, are its agreeable surprises. Things are often worse than we expect to find them, and when they are better, we may mark the day with a white stone. These reflections are as pertinent to the fortunes of man as a tourist as to any other phase of his destiny, and I recently had occasion to make them in the ancient city of Wells. I knew in a general way that it had a grand cathedral to show, but I was far from suspecting the precious picturesqueness of the little town. The immense predominance of the minster towers; as you see them from the approaching train, over the clustered houses at their feet, gives you indeed an intimation of it, and suggests that the city is nothing if not ecclesiastical; but I can wish the traveller no better fortune than to stroll forth in the early evening with as large a reserve of ignorance as my own, and treat himself to an hour of discoveries. I was lodged on the edge of Cathedral Green, and I had only to pass beneath one of the three crumbling Priory Gates which enclose it, and cross the vast grassy oval, to stand before a minster-front which ranks among the first three or four in England. Wells Cathedral is extremely fortunate in being approached by this wide green level, on which the spectator may loiter and stroll to and fro, and shift his standpoint to his heart’s content. The spectator who doesn’t hesitate to avail himself of his privilege of unlimited fastidiousness might indeed pronounce it too isolated for perfect picturesqueness—too uncontrasted with the profane architecture of the human homes for which it pleads to the skies. But, in fact, Wells is not a city with a Cathedral for a central feature; but a Cathedral with a little city gathered at its base, and forming hardly more than an extension of its spacious Close. You feel everywhere the presence of the beautiful church; the place seems always to savor of a Sunday afternoon; and you fancy that every house is tenanted by a canon, a prebendary, or a precentor.

The great façade is remarkable not so much for its expanse as for its elaborate elegance. It consists of two great truncated towers, divided by a broad centre bearing beside its rich fretwork of statues three narrow lancet windows. The statues on this vast front are the great boast of the Cathedral. They number, with the lateral figures of the towers, no less than three hundred; it seems densely embroidered by the chisel. They are disposed in successive niches, along six main vertical shafts; the central windows are framed and divided by narrower shafts, and the wall above them rises into a pinnacled screen, traversed by two superb horizontal rows. Add to these a close-running cornice of images along the line corresponding with the summit of the aisles, and the tiers which complete the decoration of the towers on either side, and you have an immense system of images, governed by a quaint theological order and most impressing in its completeness. Many of the little high-lodged effigies are mutilated, and not a few of the niches are empty, but the injury of time is not sufficient to diminish the noble serenity of the building. The injury of time is indeed being handsomely repaired, for the front is partly masked by a slender scaffolding. The props and platforms are of the most delicate structure, and look in fact as if they were meant to facilitate no more ponderous labor than a fitting-on of noses to disfeatured bishops, and a rearrangement of the mantle-folds of strait-laced queens, discomposed by the centuries. The main beauty of Wells Cathedral, to my mind, is not its more or less visible wealth of detail, but its singularly charming tone of color. An even, sober, mouse-colored gray covers it from summit to base, deepening nowhere to the melancholy black of your truly romantic Gothic, but showing, as yet, none of the spotty brightness of “restoration.” It is a wonderful fact that the great towers, from their lofty outlook, see never a factory chimney—those cloud-compelling spires which so often break the charm of the softest English horizons; and the general atmosphere of Wells seemed to me, for some reason, peculiarly luminous and sweet. The Cathedral has never been discolored by the moral malaria of a city with an independent secular life. As you turn back from its portal and glance at the open lawn before it, edged by the mild gray Elizabethan Deanery and the dwellings hardly less stately which seem to reflect in their comfortable fronts the rich respectability of the church, and then up again at the beautiful clear-hued pile, you may fancy it less a temple for man’s needs than a monument of his pride—less a fold for the flock than for the shepherds—a visible sign that beside the actual assortment of heavenly thrones, there is constantly on hand a choice lot of cushioned cathedral stalls. Within the Cathedral this impression is not diminished. The interior is vast and massive, but it lacks incident—the incident of monuments, sepulchres, and chapels—and it is too brilliantly lighted for picturesque, as distinguished from strictly architectural, interest. Under this latter head it has, I believe, great importance. For myself, I can think of it only as I saw it from my place in the choir during afternoon service of a hot Sunday. The Bishop sat facing me, enthroned in a stately Gothic alcove, and clad in his crimson band, his manches bouffantes, and his lavender gloves; the canons, in their degree, with the archdeacons, as I suppose, reclined comfortably in the carven stalls, and the scanty congregation fringed the broad aisle. But though scanty, the congregation was select; it was unexceptionably black-coated, bonneted, and gloved. It savored intensely, in short, of that inexorable gentility which the English put on with their Sunday bonnets and beavers, and which fills me—as a purely sentimental tourist—with a sort of fond reactionary remembrance of those animated bundles of rags which one sees kneeling in the churches of Italy. But even here, as a purely sentimental tourist, I found my account: one always does in some little corner in England. Before me and beside me sat a row of the comeliest young men, clad in black gowns, and wearing on their shoulders long hoods trimmed with white fur. Who and what they were I know not, for I preferred not to learn, lest by chance they should not be as mediaeval as they looked.

My fancy found its account even better in the singular quaintness of the little precinct known as the Vicars’ Close. It directly adjoins the Cathedral Green, and you enter it beneath one of the solid old gate-houses which form so striking an element in the ecclesiastical furniture of Wells. It consists of a narrow, oblong court, bordered on each side with thirteen small dwellings, and terminating in a ruinous little chapel. Here formerly dwelt a congregation of Vicars, established in the thirteenth century to do curates’ work for the canons. The little houses are very much modernized; but they retain their tall chimneys, with carven tablets in the face, their antique compactness and neatness, and a certain little sanctified air, as of cells in a cloister. The place is deliciously picturesque, and approaching it as I did, in the first dimness of twilight, it looked to me, in its exaggerated perspective, like one of those “streets” represented on the stage, down whose impossible vista the heroes and confidants of romantic comedies come swaggering arm-in-arm, and hold amorous converse with the heroines at second-story windows. But though the Vicars’ Close is a curious affair enough, the great boast of Wells is its Episcopal Palace. The Palace loses nothing from being seen for the first time in the kindly twilight, and from being approached with an unexpectant mind. To reach it (unless you go from within the Cathedral by the cloisters), you pass out of the Green by another ancient gateway into the market-place, and thence back again through its own peculiar portal. My own first glimpse of it had all the felicity of a coup de théâtre. I saw within the dark archway an enclosure bedimmed at once with the shadows of trees and heightened with the glitter of water. The picture was worthy of this agreeable promise. Its main feature is the little gray-walled island on which the Palace stands, rising in feudal fashion out of a broad, clear moat, flanked with round towers, and approached by a proper drawbridge. Along the outer side of the moat is a short walk beneath a row of picturesquely stunted elms; swans and ducks disport themselves in the current and ripple the bright shadows of the overclambering plants from the episcopal gardens and masses of purple valerian lodged on the hoary battlements. On the evening of my visit, the haymakers were at work on a great sloping field in the rear of the Palace, and the sweet perfume of the tumbled grass in the dusky air seemed all that was wanting to fix the scene for ever in the memory. Beyond the moat, and within the gray walls, dwells my Lord Bishop, in the finest palace in England. The mansion dates from the thirteenth century; but, stately dwelling though it is, it occupies but a subordinate place in its own grounds. Their great ornament, picturesquely speaking, is the massive ruin of a banqueting-hall, erected by a free-living mediaeval bishop, and more or less demolished at the Reformation. With its still perfect towers and beautiful shapely windows, hung with those green tapestries so stoutly woven by the English climate, it is a relic worthy of being locked away behind an embattled wall. I have among my impressions of Wells, besides this picture of the moated Palace, half a dozen memories of the pictorial sort, which I lack space to transcribe. The clearest impression, perhaps, is that of the beautiful church of St. Cuthbert, of the same date as the Cathedral, and in very much the same style of elegant, temperate Early English. It wears one of the high-soaring towers for which Somersetshire is justly celebrated, as you may see from the window of the train as you roll past its almost top-heavy hamlets. The beautiful old church, surrounded with its green graveyard, and large enough to be impressive, without being too large (a great merit, to my sense) to be easily compassed by a deplorably unarchitectural eye, were a native English expression, to which certain humble figures in the foreground gave additional point. On the edge of the churchyard was a low-gabled house, before which four old men were gossiping in the eventide. Into the front of the house was inserted an antique alcove in stone, divided into three shallow little seats, two of which were occupied by extraordinary specimens of decrepitude. One of these ancient paupers had a huge protuberant forehead and sat with a pensive air, his head gathered painfully upon his twisted shoulders, and his legs resting across his crutch. The other was rubicund, blear-eyed, and frightfully besmeared with snuff. Their voices were so feeble and senile that I could scarcely understand them, and only just managed to make out the answer to my enquiry of who and what they were—“We’re Still’s Almshouse, sir.”

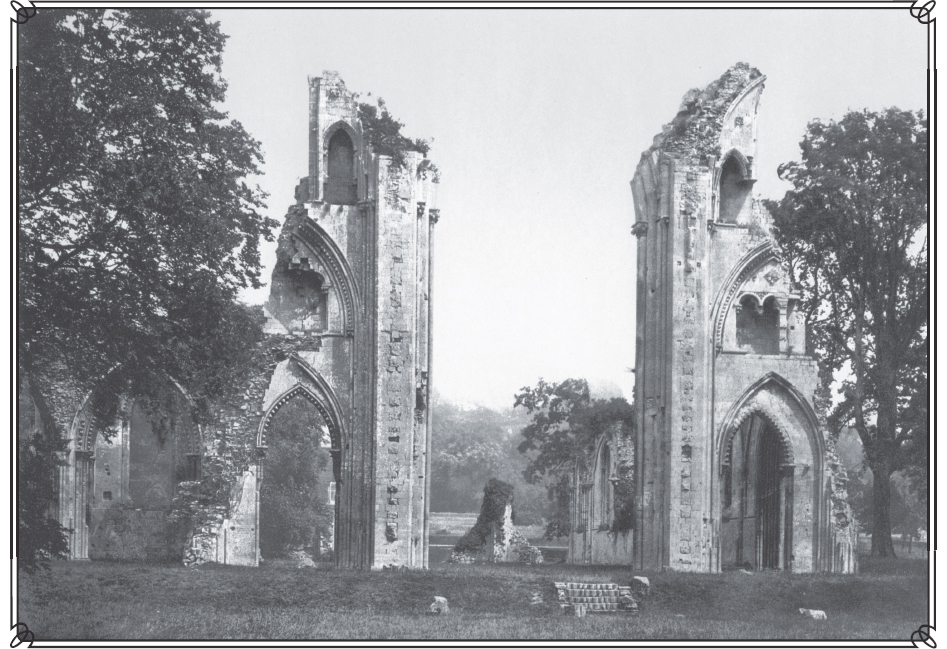

One of the lions, almost, of Wells (whence it is but five miles distant) is the ruin of the famous Abbey of Glastonbury, on which Henry VIII, in the language of our day, came down so heavily. The ancient splendor of the architecture survives, but in scattered and scanty fragments, among influences of a rather inharmonious sort. It was cattle-market in the little town as I passed up the main street, and a savor of hoofs and hide seemed to accompany me through the simple labyrinth of the old arches and piers. These occupy a large back-yard close behind the street, to which you are most prosaically admitted by a young woman who keeps a wicket and sells tickets. The continuity of tradition is not altogether broken, however, for the little street of Glastonbury has rather an old-time aspect, and one of the houses at least must have seen the last of the Abbots ride abroad on his mule. The little inn is a capital bit of picturesqueness, and as I waited for the ’bus under its low dark archway (in something of the mood, possibly, in which a train was once waited for at Coventry), and watched the barmaid flirting her way to and fro out of the heavy-browed kitchen and among the lounging young appraisers of colts and steers and barmaids, I might have imagined that the merry England of the Tudors was not utterly dead. A beautiful England this must have been as well, if it contained many such abbeys as Glastonbury. Such of the ruined columns and portals and windows as still remain are of admirable design and finish. The doorways are rich in marginal ornament—ornament within ornament, as it often is; for the dainty weeds and wild flowers overlace the antique tracery with their bright arabesques and deepen the gray of the stonework, as it brightens their bloom. The thousand flowers which grow among English ruins deserve a chapter to themselves. I owe them, as an observer, a heavy debt of satisfaction, but I am too little of a botanist to pay them in their own coin. It has often seemed to me in England that the purest enjoyment of architecture was to be had among the ruins of great buildings. In the perfect building one is rarely sure that the impression is simply architectural: it is more or less pictorial and sentimental; it depends partly upon association and partly upon various accessories and details which, however they may be wrought into harmony with the architectural idea, are not part of its essence of spirit. But in so far as beauty of structure is beauty of line and curve, balance and harmony of masses and dimensions, I have seldom relished it as deeply as on the grassy nave of some crumbling church, before lonely columns and empty windows, where the wild flowers were a cornice and the cloudy sky a roof. The arts certainly have a common element. These hoary relics of Glastonbury reminded me in their broken eloquence of one of the other great ruins of the world—the “Last Supper” of Leonardo. A beautiful shadow, in each case, is all that remains; but that shadow is the artist’s thought.

Salisbury Cathedral, to which I made a pilgrimage on leaving Wells, is the very reverse of a ruin, and you take your pleasure there on very different grounds from those I have just attempted to define. It is perhaps the best known cathedral in the world, thanks to its shapely spire; but the spire is so simply and obviously fair that when you have frankly made your bow to it you have anticipated aesthetic analysis. I had seen it before and admired it heartily, and perhaps I should have done as well to let my admiration rest. I confess that on repeated inspection it grew to seem to me the least bit banal, as the French say, and I began to consider whether it doesn’t belong to the same range of art as the Apollo Belvidere or the Venus de’ Medici. I incline to think that if I had to live within sight of a cathedral and encounter it in my daily comings and goings, I should grow less weary of the rugged black front of Exeter than of the sweet perfection of Salisbury. There are people who become easily satiated with blonde beauties, and Salisbury Cathedral belongs, if I may say so, to the order of blondes. The other lions of Salisbury, Stonehenge and Wilton House, I revisited with undiminished interest. Stonehenge is rather a hackneyed shrine of pilgrimage. At the time of my former visit a picnic party was making libations of beer on the dreadful altar-sites. But the mighty mystery of the place has not yet been stared out of countenance, and as on this occasion there were no picnickers, we were left to drink deep of the harmony of its solemn isolation and its unrecorded past. It stands as lonely in history as it does on the great plain, whose many-tinted green waves, as they roll away from it, seem to symbolize the ebb of the long centuries which have left it so portentously unexplained. You may put a hundred questions to these rough-hewn giants as they bend in grim contemplation of their fallen companions; but your curiosity falls dead in the vast sunny stillness that enshrouds them, and the strange monument, with all its unspoken memories, becomes simply a heart-stirring picture in a land of pictures. It is indeed immensely picturesque. At a distance, you see it standing in a shallow dell of the plain, looking hardly larger than a group of ten-pins on a bowling-green. I can fancy sitting all a summer’s day watching its shadows shorten and lengthen again, and drawing a delicious contrast between the world’s duration and the feeble span of individual experience. There is something in Stonehenge almost reassuring, and if you are disposed to feel that life is a rather superficial matter, and that we soon get to the bottom of things, the immemorial gray pillars may serve to remind you of the enormous background of Time. Salisbury is indeed rich in antiquities. Wilton House, a most comely old residence of the Earl of Pembroke, preserves a noble collection of Greek and Roman marbles. These are ranged round a charming cloister, occupying the centre of the house, which is exhibited in the most liberal fashion. Out of the cloister opens a series of drawing-rooms hung with family portraits, chiefly by Van Dyck, all of superlative merit. Among them hangs supreme, as the Van Dyck par excellence, the famous and magnificent group of the whole Pembroke family of James I’s time. This splendid work has every pictorial merit—design, color, elegance, force, and finish, and I have been vainly wondering to this hour what it needs to be the finest piece of portraiture, as it surely is one of the most ambitious, in the world. What it lacks, characteristically, in a certain uncompromising solidity it recovers in the beautiful dignity of its position—unmoved from the stately house in which its authors sojourned and wrought, familiar to the descendants of its noble originals.