![]() 2

2

![]()

Refuge in Belgium, 1938–1940

Our Children Became Just Letters—The Rescue of Jewish Children from Nazi-Germany” (“Aus Kindern wurden Briefe—Die Rettung jüdischer Kinder aus Nazi-Deutschland”). That was the title and theme of a historic exhibition held in Berlin from September 29, 2004, to January 31, 2005.

“Our children are gone; all we now have is their letters.” Nothing could better describe the heart-rending decisions that my family and thousands of other frightened Jewish parents faced in Germany and Austria following the terror of Kristallnacht. In desperation they searched, begged, and cajoled their local and national Jewish social service agencies, as well as those in nearby countries, to accept their children for emigration, and probably to save their lives.

Mrs. Julie Rosenthal wrote to the “Rescue Committee” in Brussels on December 3, 1938, “My husband was arrested in our apartment in Vienna on November 10 and is now in Dachau. Because my husband (who had been working in Yugoslavia) had been unable to send support for me and for our child (we are living with my in-laws) and I could not find any employment in Vienna, I had to sell our furniture in order to live on the proceeds. In order to save my poor child from the worst fate, I beg you with all my heart to accept her so that she might soon be in more favorable circumstances and in the hands of good people. You know how difficult it is for a mother to give up her beloved child, but I hope that with God’s help to soon find the possibility of emigrating with my husband so that we can be reunited with her.”1

Arnold Schelansky of Berlin-Wilmersdorf also wrote to the Belgian Committee on December 19: “This morning I was summoned to the emigration office and was ordered to leave Germany with my family within four weeks. Considering this horrible situation, I beg you from all my heart to allow the immediate acceptance of our two sons in Belgium (born in 1922 and 1926). It would be a great relief to know they are safe outside Germany.”2

Iakar Reiter of Dortmund, Germany, wrote to the committee on March 16, 1939, seeking to place his two sons, aged thirteen and eighteen. “On November 10, 1938, I was taken into protective custody [Schutzhaft] and kept in a concentration camp until the end of December. Now I have no more possibility of earning money and we must give up our apartment in April. It will then no longer be possible to keep our children. I therefore beg you most humbly to do all possible to bring our younger son Leo (thirteen years [old]) to Belgium.”3

No one knows how many such letters were sent by desperate parents to foreign countries, although the partial archives of the Belgian Rescue Committee at Centre National des Hautes Études Juives (CNHEJ) alone contain many—all with similarly urgent pleas.

The cruel events of the Kristallnacht pogrom were widely reported in foreign countries and drew special attention and action in Jewish circles. In England, Jewish leaders persuaded the government to authorize the immigration of unaccompanied children, which became known as the “Kindertransports” (children transports). Some 10,000 children from Germany, Austria, and eastern European countries were brought to England in 1938 and 1939 under this special permission.

One can only guess at the fears and heartaches of the parents and relatives who were anxious to send their children to a strange land where they did not speak the language, where they were in the hands of strangers, and at an age when family care and love are most needed and valued. “Into the Arms of Strangers” is the appropriate name of a movie about these Kindertransports to England.

In Belgium, Max Gottschalk, a prominent attorney and Jewish leader, launched a special mission immediately after Kristallnacht, with far-reaching results. He had already occupied prominent positions in the Belgian government and in academia, as well as on the Geneva-based Bureau International du Travail (International Labor Office). Beginning in 1933 he created and presided over the Comité d’Aide et d’Assistance aux Victimes de l’Antisémitisme en Allemagne (CAAVAA, or Aid and Assistance Committee for Victims of Anti-Semitism in Germany).4

Immediately after Kristallnacht, Gottschalk founded a new committee composed of about a dozen well-to-do and highly placed Belgian Jewish women whose aim became the rescue of Jewish children from Germany and Austria. Known as the Comité d’Assistance aux Enfants Juifs Réfugiés (CAEJR, or Jewish Refugee Children’s Aid Committee), it was first chaired by Mme Renée deBecker-Remy, the daughter of Belgian financier Baron Lambert and, through her mother, a descendant of the Rothschild banking family.

Although she remained very active, Mme deBecker-Remy was soon succeeded by Mme Marguérite Goldschmidt-Brodsky, the wife of Alfred Goldschmidt, who was a prominent industrialist and the treasurer of the Belgian Red Cross. A brother-in-law, Mr. Paul Hymans, was a Belgian cabinet minister.5

Another prominent committee member was Mme Lilly Felddegen, Swiss-born (and non-Jewish) spouse of another Belgian Jewish business leader. Her extensive private archive of these and later events became a vital resource for this book.

The activism, high-level relationships, and incredible devotion of these prominent women became important factors in the fate of the Children of La Hille. Our story begins with the creation of the women’s committee.

Very little has been known of their vital role in the Holocaust until now—rescuing and then safeguarding nearly 1,000 Jewish children from Germany and Austria. Throughout the committee’s activities, Gottschalk remained a vital supporter and connector for their work, almost like a godfather (in the best sense of that term).

As soon as the committee opened its office in November 1938 on rue DuPont next to the main synagogue building of Brussels, pleas from German and Austrian parents, such as those quoted above, started to pour in. As in other countries, the political climate for accepting refugees was not favorable in Belgium because unemployment and the Nazi aggression against their Austrian and Czech neighbors preoccupied the population and the politicians.

By guaranteeing that the children would stay in Belgium only until they could be accepted in other countries and that the committee would closely supervise their care and placement, the women initially were able to obtain entry permits for 250 children up to age fourteen.6

Although a small paid staff worked at its rue Dupont office, the committee members were personally involved in all phases of the selection and daily care of the children.7

Correspondence in the committee records indicates that hundreds of German and Austrian Jewish families made direct contact with the committee, as did local Jewish welfare offices of the two countries on behalf of families of their city or area. The “grapevine” network of desperate parents who discovered the Belgian “Comité” through family friends and relatives probably played a major role in the selection of the children. This interaction emerges from letters in the committee files written by Bavarian parents known to the author.

Nearly 1,000 Jewish children were brought to Belgium or cared for by the Committee between November 1938 and May 1940 (when the Germans invaded Belgium). Exact numbers are difficult to establish but different reports and correspondence support this estimate. Correspondence between Belgian Justice Minister Joseph Pholien and Prime Minister Paul-Henri Spaak documents that Minister Pholien twice authorized quotas of 250 immigrant children, plus an unannounced additional 250.8

The age limit was fourteen and the committee was held responsible for the children’s upkeep and suitable placement. Each refugee child was required to be registered with the local police and local authorities had to be notified when a child was moved to a different location.

The archives of the Sureté Publique (Public Security) in Brussels contain records of many of these children, with each assigned an identification number. In the final organized “transport” that arrived on June 15, 1939, the last child (David Blayman of Bonn, Germany) was issued Number 678.9 On December 10, 1939, committee staff reported to Mme Felddegen (who by then had emigrated to New York) that 570 children were then already under the committee’s care.10

Typically, German and Austrian families were notified to send their children to the Jewish Welfare Office at Rubensstrasse 33 in Cologne on a specified date, where the group would be assembled and sent by train to Brussels, accompanied by personnel from the Belgian Red Cross. The last such transport, on June 15, 1939, was composed of twenty-nine girls and boys. Toni Steuer from Essen, Germany, and Hans Bock from Berlin were almost three years old, while the oldest, Eleonore Fischbein, also from Berlin, was eighteen years old. Nine of this group would remain together for several years as part of the “Children of La Hille,” including the author.11

It is not known how many times such organized groups were assembled in Cologne for the trip to Brussels. In fact, many of the children under the committee’s care had crossed the Belgian border illegally, while others had come to Belgium with a single parent who could not take care of them, or they had been sent to relatives who placed them with the committee for various reasons. Because these single arrivals often were not recorded as “immigrants” by the authorities, their total number is not traceable.

From January 2 through 8, 1939, at least seventy Jewish children crossed the Belgian border illegally at Herbestal, carrying one-way train tickets to Brussels and Antwerp. All were turned back to the Aachen, Germany departure point.12 Children who arrived illegally often were brought to the Salvation Army in Brussels and transferred to CAEJR for assignment to private homes or to one of its several children’s homes. Mme deBecker-Remy negotiated with Justice Minister Pholien about “legalizing” twenty-eight of the clandestine arrivals by counting them as part of the 250 children specified in the immigration quota.13 In return for granting the third contingent of 250 children, “Mme deBecker promised not to ask for any additional permissions during the next three months,” Mr. Pholien reported to Mr. Spaak.14

Committee and government negotiations made the organized escapes possible, but they could not calm the trauma and anguish of the children and of their parents. The parents—who had done everything possible to send them away—were especially worried that they might never see their beloved children again. A few examples of the departure from home of some La Hille children illustrate the desperation and the trauma:

Ilse Wulff Garfunkel recalls that when she was thirteen, “We lived in Stettin and my parents accompanied me to Berlin where we said good-bye to each other before I continued by train to Cologne. At that time, my parents knew they were going to Shanghai, but they had not told me about their plans. They felt I had a better chance to grow up in ‘civilized’ Europe.”

“Much later I realized how difficult our separation must have been for my parents, who probably wondered whether they would ever see me again. On the train a girl who sat next to me was crying bitterly and it took a great deal of willpower on my part not to do the same.”15

Susi Davids, daughter of Paul and Irma Davids, lived in Wuppertal-Elberfeld (in Germany’s Ruhr area). “After Kristallnacht my parents did not let my brother Gerd or me out of the house except to buy us new clothes with which to leave Germany,” she recalls. “In December 1938 we [Susi and brother Gerd, age eleven] were put in a compartment that was completely full. I did not cry, nor did any other child. I was far too busy examining and eating my favourite chocolates. I was delighted to receive a whole box to myself, as sweets were always controlled at home by my parents. I just remember saying good-bye to my parents among a crowd of other parents.” At that time, Susi was just eight years old.16

Else Rosenblatt, oldest of four sisters, explained the dilemma faced by her parents in an interview with German cable channel 34 at a reunion in France in 1993: “I remember that we had to go from Garzweiler to Aachen and the meeting point was Cologne. That is where I saw my parents for the last time. At that time we hoped that we would be reunited later. I was thirteen years old and my three sisters were younger. . . . My mother did not want us to leave but my father stated that things in Germany would only get worse. ‘You have to leave. You cannot stay here because it is much too dangerous. Your mother won’t leave and I will stay with her, but you must go’. And that’s how we arrived in Belgium.”17

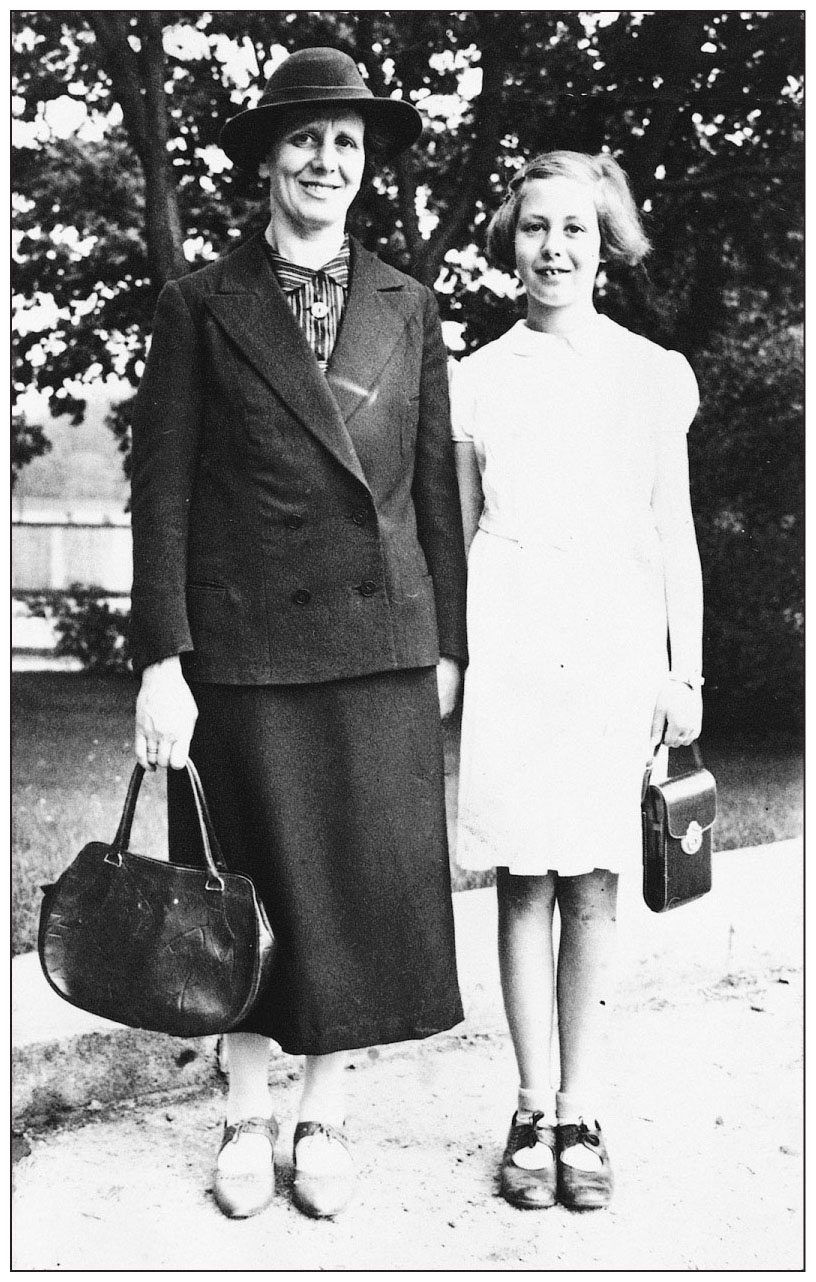

1. Ilse Wulff with her mother in Stettin, Germany, 1938. Reproduced with permission from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archive.

Herbert Kammer came to Belgium with his father Georg from their home in Vienna. He was seven years old. His mother was able to emigrate from Vienna to England and work as a domestic (as did some other mothers, but they could not bring their children). Eventually Herbert came under the care of the committee and was able to flee with the Children of La Hille.18

Friedl Steinberg of Vienna says she “did not arrive in Belgium via a Kindertransport.”19 “I walked from Aachen to Eupen [then in Belgium] on foot. We were arrested by the German border police at the ‘Dreiländerblick’ [Three-Countries Vista] at the Belgian border, detained and questioned and sent on our way to Belgium, the laughter of the German border police following us.”

“I was in the company of a clever young boy from Berlin who had offered my mother [she was waiting at an Aachen hotel for a ‘passeur’—an illegal border guide] to take me for a walk because I had felt very ill. This ‘walk’ in Aachen turned into a ten-hour hike through fields and woods, with border police dogs barking like mad. My mother, who had stayed in Aachen, had no idea what happened to us until I could send her a telegram three days later. There was a quota for children coming to Belgium and I probably replaced one on the quota who did not come,” said Friedl, who was fourteen years old at the time of these events.

Emil (Émile) and Joseph Dortort (fifteen and eleven years old), from Bottrop, Germany, were picked up by Belgian police after they crossed the border illegally. “They brought them to me and I did what I could for them,” wrote Mme Lilly Felddegen to their cousin in Philadelphia. “The older (boy) is so serious and watches so well on the younger brother.”20

On Christmas day 1938 Mrs. Findling of Cologne accompanied her three little boys (aged eleven, eight, and six) and her nine-year-old daughter Fanny by train to Aachen. From there she sent them alone with round-trip tickets to Brussels. The oldest son, Joseph, had tried to escape to Holland with a one-way ticket shortly before Kristallnacht, but was turned back by Dutch border officials. The children’s father, born in Poland, had been deported to the German-Polish border area as part of the roundup that led to the Paris embassy murder and to Kristallnacht.

At the Belgian border, the siblings’ cousin Sala met the children and turned them over to the committee in Brussels. In desperation, Mrs. Findling drugged her youngest daughter, two-year-old Regina, and smuggled her into Belgium by train with a (possibly unknown but willing) stranger. Mrs. Findling then crossed the border illegally with a paid illegal guide and lived in Antwerp for a time with daughter Fanny.

Son Joseph says he discovered his little sister at the committee office by accident. All five Findling children survived the war, the boys as part of the La Hille group.

In 1943 their mother was deported and murdered in Poland and their father became a victim of the brutal German killing squads (Einsatzgruppen) in Poland.21

Before he embarked alone on the ill-fated trip to Cuba on the SS St. Louis in May 1939 (the ship’s odyssey across the Atlantic Ocean and back is infamous), Alfred Manasse of Frankfurt wrote to the Committee to thank it for harboring his sons Gustav and Manfred (then aged eight and four). After the aborted crossing Manasse and 213 others were admitted to Belgium and he lived in Brussels near his sons. Both Manasse parents were deported in 1942 and murdered in Poland. The Manasse boys became part of the La Hille group and survived the war.22

By the time brothers Julius and Kurt Steinhardt (ages eight and seven) from Aachen came under the committee’s care they had already experienced the worst of family tragedies. Father Max Steinhardt had fled alone from Germany to Brussels and in August 1939 went to meet his wife and sons as they were arriving in Liège. Through a mix-up they missed each other, the father suffered a heart attack from the trauma and died without seeing his family. Sophie Steinhardt, the mother, died in Brussels of tuberculosis on February 8, 1940. Both Steinhardt boys were placed at Home Speyer by the committee and thus became part of the La Hille colony.23

In Vienna fourteen-year-old Edith Goldapper vacillated about leaving her doting parents. As their only child, she was especially close to them. When other young girls at the millinery shop where she was apprenticing were emigrating, she too felt the urge to escape persecution in Austria.

“Almost daily I pestered my beloved parents to take steps to get me out of the country,” she writes in her diary. “Baroness Ferstel, a family friend and a relative of Belgian committee president Mme Goldschmidt, helps in the effort to get me to Belgium.” When word came that she was accepted, “my dear parents supplied good advice and kept up my courage by promising to join me soon. And that consolation kept up my spirits.”

“Otherwise I never would have left,” she recalls. Her parents and relatives came to see Edith off at the Vienna train station on December 19, 1938, for the trip to the assembly point in Cologne. “First Mama and I embrace, then Papa, then Mama again. For the first time in my life I see Papa crying. Tears stream from his closed eyelids (he was blinded as an Austrian soldier in World War I). Mutti [Mom] also is inconsolable. So am I! I had just turned fourteen years old and now I will get to know the world; but I think that the sooner you start, the better.”24

For Lixie Grabkowicz, also fourteen years old, the departure from Vienna to Antwerp was almost routine. “Leaving my family (mother, father, sister and grandmother) was not traumatic because I never anticipated it to become a very permanent and final separation. I had an invitation to come to my best friend’s house in Antwerp and was looking forward to going there. My family took me to the train station and we said our goodbyes. I don’t remember tears and wails. It was more like a trip to summer camp,” she recalls.

“The hard truth and then longing to be home again came later when the stay at my friend’s house became difficult.”25 Lixie was accepted at one of the Belgian committee’s girls’ homes.

For Werner Epstein, leaving his family in Berlin for Belgium at age sixteen also was more routine than tragic. “After Kristallnacht, I lost my job and decided, with my parents’ support, to leave the country. I sold my bicycle and took the train to the Belgian border. I will never forget being on the train to leave Berlin. All of my family—father, mother, sisters, uncles and nieces—were smiling at me.”

“I remember my mother tried to smile but her eyes were too wet. I was like a little kid going on vacation. I didn’t know what lay ahead of me and I didn’t realize that I would never see my family again. My biggest regret is that I never said good-bye.”26 Werner Epstein also was taken under the committee’s wing, was deported from France in 1943, and survived Auschwitz and other atrocities.

Like many of the children rescued by the committee after Kristallnacht, thirteen-year-old Inge Joseph of Darmstadt, Germany, was able to live with a relative, Gustav Wurzweiler (her father’s cousin) and his wife in a Brussels apartment.

In the book about her experiences, Inge: A Girl’s Journey through Nazi Europe, she and her nephew, author David E. Gumpert, describe her leave-taking on January 11, 1939. “The plan was for Mutti [Mom] to travel with me on the train to Cologne. From there I was to travel with other children from Germany who were part of the Kindertransport to Brussels.”

“Mutti carried on a conversation in a normal tone, as if she were merely escorting me to a relative’s for a few weeks away.”27 After a few months living with the relative and then with another host family, Inge was transferred to Home Général Bernheim in Zuen, a Brussels suburb where some thirty other refugee girls were housed by the committee (at 21 chaussée de Leeuw, Saint-Pierre—later renamed chaussée de Ruisbroek). She too became one of the Children of La Hille.

While many of the children rescued by the committee came to Belgium in organized and orderly fashion, the escape and arrival of the Schütz sisters—Ruth and Betty—from Berlin was among the most daring and hazardous of those who crossed the Belgian border illegally.

After their father, Joseph, had been seized and deported in the Nazi roundup of Polish-born Jews in 1938, the family’s life and livelihood had become precarious. After some relatives had succeeded in emigrating to England, thirteen-year-old Ruth beseeched her mother to let her and younger sister Betty try to emigrate to Israel or England.

Ruth began to visit several Jewish emigration offices, but was told to come back a year later because she was too young. In the courtyard of a Berlin office building she became aware of children being briefed about a children’s group emigration to Belgium. “I returned to the courtyard every day until I had exact information on the date, the hour, and the train station from which this group of eighty children was supposed to leave for Belgium,” she writes in her autobiography Entrapped Adolescence.

She laid out her plan to her mother: “Betty and I will get on the train as if on our way to England, and on the way we will join the group of children and reach Belgium with them.”

“I was afraid that I would have difficulty convincing my mother to agree with my adventurous plan. But to my surprise, she too saw this as a chance for us to escape from Germany,” she recalls.

The 8th of February 1939 was a cold and clear day. Wearing a heavy winter coat, a scarf, and matching wool caps, we made our way to the train station. From afar I made out a group of children who were separating from their relatives. Mother hugged us and told us the things that are said when one separates at train stations. I didn’t feel any sadness at leaving her, and didn’t cry. I wanted to get on the train and put an end to the nightmare of waiting.

The train passed the outskirts of Berlin and we left the compartment and passed several others. When we finally heard the happy chatter of girls, we joined them and told them that we were traveling through Brussels to England, and we would be happy to travel with them. The chaperones moved from compartment to compartment, checking the girls and affixing a tag to the collar of each girl.

We were getting closer to the border and German policemen checked the documents that I showed them and walked away. The train moved, leaving Germany and stopped on the Belgian side. This time Belgian police boarded the train. They passed from compartment to compartment and stopped near us. On our lapels was no ticket like the rest of the girls. The policemen made a sign for us to get off the train into the station. I pointed to one of the chaperones and said that he should check with her what the problem is. I grabbed Betty, who was already on one of the steps, and started to run crazily through the cars. The train continued to move, and we were in Belgium. When the train stopped again, we had arrived in Brussels.

We descended with the rest of the girls and in a large hall men and women were waiting for their children.

The hall empties and we are left to stand, squeezed against the wall in a dark corner. “What is your name? To whom are you going? You’re not listed.” Confusion ensues around us.

“Where did you come from? We don’t have room for you. You have to go home.” And I stubbornly say: “We have no home, we have no address. We have nowhere to return to.” They consulted in whispers in French, and I’m trying to understand, and suddenly I hear, “Salvation Army.” They want to send us to stay overnight in the Salvation Army. At this point all the dams burst. I burst out crying [and] couldn’t be stopped. And Betty, in a large voice, cries after me, “No! Don’t send us to the Salvation Army!”

A large woman who was already on her way out with a girl that she had just received, asked, “What’s the problem?” After a discussion she turned to us and said, “Come on,” and we accompanied her outside. “Is this a dream?” I asked myself. A chauffeur opened the door of a car, and I jumped into the soft, comfortable seat. We traveled for quite a distance in the night.

“Here, we have arrived,” said the woman who was so kind to us, and before us was a grand villa. A young woman stood at the entrance. Around her waist was a small, white apron with a lace border, and on her head was a little white hat that gathered her hair. “Madame at your service,” she said.28

The Schütz sisters stayed with the Padawer family for a while, then were eventually transferred to the committee’s Home Général Bernheim.

Even at age seventy-eight, Henri Brunel, born in Cologne, vividly recalled the trauma. “It was wrenching for me to leave my poor parents. In spite of my young age [he was fourteen], I fully understood the frightening situation that lay ahead for them and I had the feeling that I would never see them again.”29

At this early stage of the saga of the Children of La Hille, it is evident that fright, panic, courageous parents, and the resourcefulness of young children—and especially good luck—all became intermingled as ruthless Nazi Germans enthusiastically enacted their hatred not only of Jewish adults, but also hatred of Jewish children of all ages.

A shameful example of Nazi atrocities against children occurred at the Jewish orphanage in the town of Dinslaken, near Düsseldorf. Approximately thirty resident children were frightened and brutalized by Nazi mobs during the Kristallnacht pogrom. They were herded into the yard while SA (Sturmabteilung) thugs destroyed the interior of their large building.

The children were forced to join other Jewish citizens in a humiliating parade through the town. Four of the oldest boys were ordered to pull an empty hay wagon loaded with the younger children through the streets as part of a “Jewish Parade” as spiteful spectators taunted them.

Some weeks later, the acting director of the home, Yitzhak Sophoni Herz, was able to resettle the children in a vocational school in Cologne. From there he succeeded in arranging their emigration to Holland and Belgium.30

Among the Dinslaken orphanage children who were accepted by the Belgian committee were trainees Inge Berlin and Ruth Herz (not related to the director), Alfred and Heinz Eschwege, Klaus Sostheim and Rolf Weinmann, as well as the Steuer children. Bertrand and Hanna Elkan and Inge and Heinz Bernhard were local Dinslaken children whom the committee also rescued.

A friendly Jewish social worker arranged to include Egon Berlin of Koblenz (younger brother of Inge Berlin) in the contingent from the Dinslaken orphanage.31 In Brussels, Mr. Dronsart, executive director of the Belgian Red Cross personally welcomed them at their hotel.32

Even though CAEJR members had no known prior experience with managing large numbers of children, they apparently learned quickly simply “by doing.” Between November 29, 1939, and March 31, 1940, the committee raised BEF 1,206,311 (Belgian francs), then worth US$723,787, and spent BEF 942,635 (or US$565,581), leaving a balance of BEF 263,676 (US$158,206) (currency values at 1939 rate).33 Where possible, they sought monthly support payments from the children’s relatives and family friends in other countries. The children’s parents were, in most cases, already in desperate financial straits and Germany would not let them send money to foreign countries.

Funds were also raised from the Belgian government and private donations. Mme Goldschmidt-Brodsky and Senator Herbert Speyer visited Belgium’s Queen Elisabeth in the spring of 1939 to ask for assistance. The Queen personally donated 5,000 Belgian francs (then worth some US$3,000) to the committee, “to buy clothing and toys for the children.”34

An organization willing to lend financial support was the Comité des Avocates (Women Lawyers Committee), whose honorary board included one-time justice minister Paul-Emile Janson, Camille Huysmans, and several university presidents.35

Many of the young refugees were not subsidized by relatives or friends, but host families accepted them—some with pay and many without (in early April 1940, forty-two children lived with private families without any payment, and forty others with families whom the committee paid).36 A committee report dated December 10, 1939, shows that 330 of its children were then housed with their own parents or with relatives living in Belgium.37

Efforts were made to match the children with families whose values or occupations were similar to the selected child’s family. Where possible, siblings were placed together. But there also were incidents where very young children had to advocate for themselves.

Helga Schwarz Assier recalls her anguish when her younger brother Harry was selected by a well-meaning couple. “No!” she cried, “you’ll take both or none.” As none of the families present was ready to take two children, they were placed in a group home. “And we were happy to be staying together,” she recalls. Years later, with children of her own, she appreciated how distraught her parents must have been to send their children into the unknown.38

Committee members also attempted to place children from Orthodox Jewish families into similar environments. Insofar as possible, the committee preferred to place the children in private homes, and Mme Alfred (Louise) Wolff and other committee members toured the country to seek host families.39 Committee members also kept a few refugee children in their own homes.40

2. Home Speyer building in Anderlecht, Belgium, with “A Vendre” sign, 1939. From the author’s personal collection.

More than 100 children were lodged in several foyers (children’s homes). About forty-five boys were housed at Home Herbert Speyer, a multi-story attached house in the Anderlecht suburb of Brussels. This facility belonged to, and was operated by, the long-established Foyer des Orphelins, a not-for-profit organization for orphans.41 More than thirty girls were placed in the Home Général Bernheim in Zuen, at the northern edge of Brussels.42

Heide-lez-Anvers in Antwerp cared for twenty older boys and ten were placed in the care of teachers Mr. and Mme Korytowsky in Schaerbeek. Others were housed in Wezembeek, a Brussels suburb, on the estate of the Lambert banking family.

The “Foyer des Orphelins” (orphanage)—with facilities on rue de Korenbeek, at the English Channel resort of Middlekerke, on rue du Geomètre in Brussels, and also in Louvain—played an important role as the committee’s children were housed in their facilities for a time.43 (During the German occupation of Belgium, this multi-site foyer provided refuge for a number of the committee’s children who survived the war there. It employed the DeWaay couple after they returned from France in the fall of 1940.)44

The Salvation Army was often the first stop for children who had entered Belgium illegally (see the Schütz sisters’ arrival). When the required paperwork with the Sureté Publique was completed, these children, housed temporarily at the Salvation Army, were placed with families or at the committee’s children’s homes.

Finding and monitoring qualified caregivers for so many children in its several facilities was another task for the leaders of the committee. At Home Général Bernheim the directrice (woman manager) was Elka Frank, just twenty-three years old, assisted by her twenty-five-year-old husband, Alexandre (Alex). Elka was born in Berlin; Alex in Belgium. They had met and married in Palestine, then returned to Belgium.45 Neither had previous experience for their assignment at Home Général Bernheim.

Mrs. Flora Schlesinger, a refugee from Austria, was engaged as the cook and became a motherly friend for many of the girls. Her husband, Ernst Schlesinger, did yard and garden work and their young son Paul also lived at the home.

At Home Speyer, Gaspard DeWaay (“Oncle Gaspard”) was appointed manager in January 1939. His wife, Lucienne (“Tante Lucienne”), supervised the kitchen and housekeeping. Gaspard, then twenty-eight years old (born November 15, 1910, in Verviers), had been a streetcar conductor in his hometown.46 Lucienne was twenty-five years old (born October 24, 1913, also in Verviers), with a young daughter, when Mr. de Gronckel, general secretary of the Foyer put them in charge of Home Speyer.47

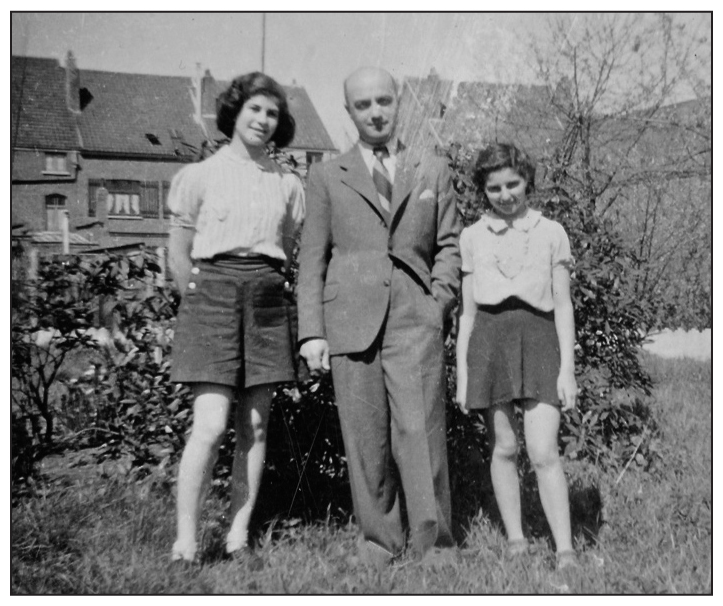

3. Three older girls at Home General Bernheim in Zuen, Belgium, 1939. From left: Else Rosenblatt, Lotte Nussbaum, Ruth Klonower. From the author’s personal collection.

Home Speyer was named after former Belgian Senator Herbert Speyer, who had donated nearly BEF 500,000 to support Comité d’Aide et d’Assistance aux Victimes de l’Antisémitisme en Allemagne (CAAVAA, or Support and Aid Committee to Victims of Anti-Semitism in Germany).48

When some of the children became ill, the committee and its staff saw to it that adequate care was provided. Kurt Moser was in isolation at the Schaerbeek Hospital for three months because of an infection, as was Rolf Loewenstein at Sainte Elisabeth Hospital.49 At least ten children were given “kinésique” (posture) physical therapy treatments for several months at the Willy B. Cox studio in Brussels, which also provided gymnastics lessons at Home Speyer, arranged and paid by the committee.50

For the children, now separated from their families and native homes, life in Belgium had pleasant, as well as difficult outcomes. Living with strangers or in group homes added more stress to the trauma of separation from parents and siblings, especially for the younger boys and girls. Adjusting to life where they did not understand the language (French or Flemish, depending on the region), having to eat foods to which they were not accustomed (endive—called chicorée—and no more home-cooked German or Austrian dishes), and going to school with children who readily tabbed them as foreigners, created emotional problems. These difficulties were offset, however, because the children (including the author) were now free of the ever-present anti-Semitic harassment in our home countries.

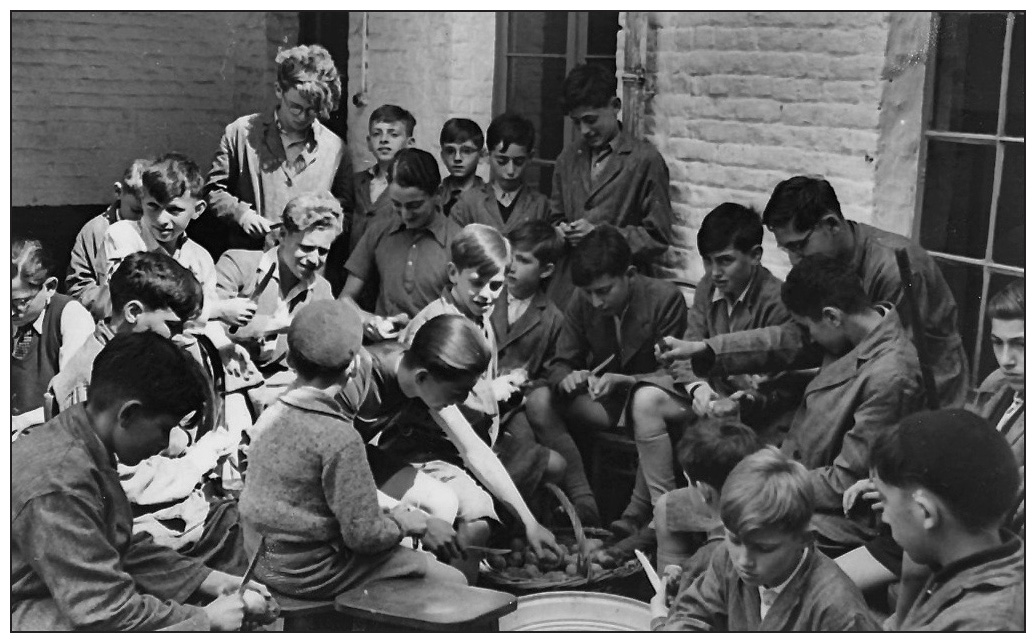

4. Group of boys at Home Speyer in Anderlecht, Belgium, 1939. Mme Lucienne DeWaay is in center; Mr. Becker, counselor from Switzerland, at left, rear. From the author’s personal collection.

Correspondence was still possible with our parents who were left behind in Germany and Austria. Some of us also could visit relatives who had emigrated to Belgium. For others, living with children from different backgrounds and with “strange” habits required adjustment, but it also educated us to the idea of tolerance and respect. Most of the children came from families of modest means and many of their parents had been emigrants from Poland and other eastern countries.

5. Group of boys peeling potatoes at Home Speyer, 1939. In center with arm reaching into basket, author Walter Reed (Rindsberg). From the author’s personal collection.

Luzian (Lucien) Wolfgang, who hailed from Vienna, told a German television reporter in 1993 “some of us came from well-to-do, advantaged families, but others, like me, from very poor families. My father was unemployed for many years.”51 With the number of children involved, it was inevitable that some would have behavior problems and others were placed with families who were not ideal hosts. Thus it was not unusual that the committee ladies shifted children between host families and group homes, because either the children or the hosts complained.

“In Brussels I worked as a ‘mother’s helper’ for a Christian family,” recalls Ruth Herz Goldschmidt, then seventeen years old, who had been an aide at Dinslaken. Actually I was the maid and slaved from dawn to late at night doing all the housework, yard work and supervising several school-age children.”52

Some of the children were moved from group homes to families and back all too frequently and for various reasons. Edith Goldapper Rosenthal’s diary of 1943 gives a vivid account—arriving in Brussels from Vienna in December 1938, she was personally welcomed by Mme Goldschmidt-Brodsky, and later by Mme Felddegen.

Her first placement was at the suburban Maison de Cure (previously a convalescent home) at Wezembeek-Oppem, where she met boys and girls with whom she would be associated again in the following years. Mme Goldschmidt-Brodsky personally moved her to a wealthy Russian-born host family in Antwerp. When the mother became ill and fourteen-year-old Edith was terribly homesick, she was transferred to the Home Général Bernheim in suburban Brussels.

The older children took advantage of their new environment, learning French or Flemish and also English, which was encouraged by the committee. Learning English was desirable because the main purpose of their stay in Belgium was to await permanent settlement in the United States, Canada, and other countries.

The language problem also had its lighter side. Kurt Klein, age thirteen, from Austria, always stumbled over the French word onze (eleven). Instead of pronouncing it “ohnz,” as the French do, he pronounced the letters as they would be in German: “on-tze.” Forever after his companions forgot his real first name and he became “On-tze” Klein, even when he joined the French Resistance in 1944. Fortunately, “Onze” always was full of fun and jokes, the camp clown, an attribute that would become an asset when his life was in the balance just a few years later.53

Committee staff reported that the children at Home Speyer and Home Général Bernheim received a “medical visit” once a month and that “Rabbi Ansbacher provided Jewish religion lessons.” In 1939 the Hanukkah holiday was celebrated with a theater visit arranged by Mme deBecker-Remy and presents were handed out to all the children, “who were in seventh heaven.”54

6. At Home General Bernheim in Zuen, Belgium, 1939. From left: Hanni Schlimmer, CAEJR Committee staff member Elias Haskelevicz, and Dela Hochberger. Reproduced with permission from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archive.

The children of school age were enrolled in Belgian schools, some of the boys in a vocational school, specializing in skills like carpentry, horticulture, and locksmithing.55 The older girls from Home Général Bernheim also attended a vocational school.

On many weekends the ladies of the committee took children of the group homes for outings to Brussels museums and to special events, often in their chauffeur-driven luxury cars. This had varying effects on the children. Some enjoyed the experience; others have complained even sixty-five years later that the women were “showing off” and made the children uncomfortable when they visited their elaborate homes—obviously not what the kindly hostesses intended. Many of the children also were taken on outings and excursions to the Belgian countryside, including some of the lovely vacation spots in the Ardennes forest. Gaspard DeWaay practiced a kind of discipline at Home Speyer that grated on the older boys who may have been spoiled at home and were advancing into their teenage years. His overly strict methods for dealing with children may have been acceptable to some at the time, but his approach was not well suited for the management and guidance of refugee children.

The recollection of the children and some of the correspondence of committee members reflect the tension that prevailed at times at Home Speyer.56 On the other hand, Home Speyer and the other sites had counselors like Mr. Becker from Switzerland, who related well to the youngsters and operated without friction.57 The Home Speyer boys also interacted well with “Tante Lucienne” (Mme DeWaay) who did her best to act as substitute mother for the refugee children under her care.

The last known “transport” of children from Nazi Germany arrived in Brussels on June 15, 1939. Some of its twenty-nine girls and boys were destined to stay together throughout the adventures of the next four years. All child refugee transports to Belgium were being halted and it was only with determined effort that this final small number of children could be admitted, states a letter from the committee to the Jewish congregation of Leipzig, Germany, dated June 8, 1939.58 Inge Helft, age thirteen of Wurzen, was the only “lucky child” of the Leipzig group to be included, the letter states.

While life in Belgium was a great improvement over the children’s experiences under the German-Austrian regime, new concerns would soon arise. The German invasion of Poland in September 1939 produced the “phony war” (declared, but not pursued by France and England) and was regarded with apprehension by Belgian citizens. It also became worrisome for the older refugee girls and boys who retained unpleasant and vivid memories of their lives in Germany and Austria.

Confident propaganda by Western countries, which extolled the deterrent of the French Maginot Line and the “impenetrable” Fort Eben-Emael near Liège in Belgium, bolstered Belgium’s hope to defend the border against a German attack. The young Jewish refugees soon learned and joined in singing the popular refrain, “Nous allons pendre notre linge sur la Ligne Siegfried” (“we’ll be hanging our laundry on the Siegfried Line”—the German counterpart of the Maginot Line).

More than 100 of the children on the committee’s lists succeeded in emigrating from their temporary Belgian refuge in 1939–40, as intended by their host government and by the Belgian caretakers.59 At least 47 went to England, 25 to the United States, 7 to Holland, 5 to Palestine, 4 to Chile and 1 to Shanghai.60 Among those who received US visas and emigrated were Rainer Laub, Adolf Herbst, Karl-Heinz Goldschmidt, Gerhard Hirsch, two Jülich brothers (Otto and Karl), Henriette Hahn, Marianne Scheuer, Helmuth Cohn, and Hannelore Kaufmann.61

Fate, more than planning, sometimes played a major role in the children’s lives. Susie Davids’s mother, Irma, was able to leave Germany by finding a job as a domestic for a well-placed couple in the English countryside near Birmingham. Her father, Paul Davids, was living with in-laws in Belgium. In August 1939 the mother’s English employer brought Mr. Davids, Susie, and her brother Gerd to England for a two-week vacation. They were preparing to board the channel ferry at Dover on September 4 to return to Belgium. When England declared war against Germany on September 3, they were “stranded” and fortunately stayed in England.62