CHAPTER FOUR:

YOU CAN’T DO GENDER IN A RIOT

Early in December of 2000, members of the ACME Collective issued a communiqué to the nascent anti-globalization movement. With the Battle of Seattle—and the Black Bloc actions that took place there—still fresh in people’s minds, ACME’s dispatch became a lightning rod for discussions about strategy and tactics. Marking the first public effort on the part of an anti-globalization-era US Black Bloc contingent to address the movement as a whole, the communiqué spoke primarily to a series of popular misconceptions about riotous actions. By compiling and then responding to “10 Myths About the Black Bloc,” ACME helped to frame a discussion about the merits of property destruction at demonstrations in the cosmopolitan centers of the global north.

In addition to addressing their critics’ concerns that the Black Bloc had not participated in planning the anti-WTO actions and that they had little grasp of the issues, ACME pointed out that many of their detractors believed that the Seattle rioters had simply been “a bunch of angry adolescent boys” and, hence, that their actions were inadmissible within the realm of serious politics. In repudiating this perspective, ACME pointed to its analytic superficiality. “Aside from the fact that it belies a disturbing ageism and sexism,” said ACME of the adolescent boys theory, “it is false.”

Property destruction is not merely macho rabble-rousing or testosterone-ridden angst release. Nor is it displaced and reactionary anger. It is strategically and specifically targeted direct action against corporate interests. (2001: 117)

With the tempest out of the teapot, anti-globalization activists began trying to make sense of the new political terrain. During this period, the Black Bloc (which, in Canada and the US, had been virtually unknown prior to Seattle)

24 quickly became an important site of gender struggle. Seeming to collect many of the most pressing contradictions of gendered experience and expressing them in one explosive moment, the Black Bloc forced activists to contemplate the gender of the riot. Initially, these discussions drew upon well-established debates about the problem of representation. Did the Black Bloc exclude women, as many activists held to be the case, or did it include them as some others had proposed?

25 Should women join in Bloc actions to make them more representative of the gender diversity of the movement, or should they condemn them as a persistent site of exclusion?

For activists in the movement, these questions—and the terms in which they’d been articulated—could not be avoided. Criticisms of the movement’s perceived maleness resonated strongly with activists who sought to prevent their struggles from replicating the worst elements of the system they opposed. But despite almost endless discussions about the problem of exclusion, activists came to little agreement about what the solution—the ever-elusive inclusion—would actually look like. Could inclusion be achieved by opening up existing spaces and practices, or did it require changes in the practices themselves? Could women’s participation be solicited, or were such efforts bound to be coercive and tokenistic? Despite the ambiguity of this new political terrain, for many activists one thing was certain: Black Bloc rioting and the politics of inclusion mixed about as well as petrol bombs and calming ponds.

In his position paper responding to the ACME communiqué, Brian Dominick pointed out that—despite the fact that ACME felt their actions resonated more with oppressed people than did the theatrical tactics adopted by other demonstrators—“the vast majority of oppressed people in this country didn’t have the privilege to be in Seattle for this demo, even if they wanted to, and typically don’t have the privilege of risking arrest at all.”

26 In order to emphasize his point, Dominick concluded by remarking how “one is pretty privileged if one chooses to risk arrest in the way black bloc participants did” (2000).

As Dominick’s position makes clear, the exclusion of marginalized people from political protest strikes most activists as unacceptable.

27 Consequently, if the paradigm of struggle works to exclude people of color, women, and other oppressed groups (as Black Bloc actions were thought to do), it becomes necessary to change the means by which struggle is conducted. This perspective quickly became commonsensical in certain movement circles.

I take issue with this commonsense on three grounds. First of all, the argument is based on the belief that women do not riot. History, however, does not bear this out. Second, the call to inclusion has tended to reify “woman” as a conceptual abstraction and has reinforced a representational logic at odds with genuine political transformation. This problem derives from mainstream conceptions (where the category “woman” still continues to enjoy relative stability) but also from tendencies within feminism that hold “representation” to be the principal field of political engagement. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the movement’s ongoing allegiance to “representation” (and its operational correlate, “inclusion”) has tended to occlude the opportunities for gender abolition signaled by the anti-globalization riot.

Looking for representations of women in the history of rioting can be a disorienting affair. With the exception of a few early twentieth century sketches by German expressionist Kathe Kollwitz that depict women leading large crowds of starving peasants, women have tended to be represented in the European oil painting tradition and its derivative genres—if at all—either as the victims or muses of political action.

Figure 6: Kathe Kollwitz, “Outbreak” (1903)

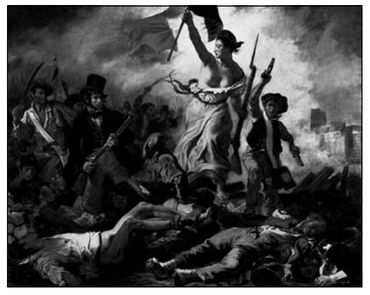

Among the tradition’s muses, perhaps the most famous is Eugène Delacroix’s heroine in La liberté guidant le peuple. Depicting the ousting of Bourbons from Paris in 1830, Delacroix’s painting places a woman at the center of the conflict. Liberté draws the mob into battle and, if we follow the narrative conventions of the genre, seems to assure their victory by her very presence. The work establishes a strong dramatic tension between eros and thanatos—a symbiotic but fraught interaction between the life-giving spirit of Woman and the capacity for men to bring death. The muse, as representational ambassador of the transcendental Idea, has always been on hand to soften harsh realities. Nevertheless, this slaughter (like every other) was not achieved by the muse but by “the people”—who in this depiction are, in fact, a cross-class alliance of men.

Figure 7: Eugène Delacroix, “Liberté guidant le peuple” (1846)

So while Liberté might be the purported reason that these Parisians were compelled to fight (and men have long deluded themselves into believing that they fight

for Woman), the fight itself does not taint her. In an otherwise dark composition, and for no other reason but to highlight her goodness, Delacroix’s muse is enveloped in a light that seems to emanate from her very being.

28 Surrounded by armed Parisians, Liberté seems to float over the bodies of the fallen. Carrying the French flag, she is bound to the new republic even as she conceals the force that made it possible. Nowadays, Delacroix’s image is more likely encountered as kitsch than as a serious political statement. And few will be surprised to find an image from the European oil painting tradition drawing on questionable metaphors and gender stereotypes. Nevertheless, by placing Liberté at the front of the insurrection “leading the people,” Delacroix’s image discloses an important debt to historical reality. And it is precisely for this reason that—even though she refuses both the muse and the transcendental feminine—Kollwitz has the woman in “Outbreak” occupying a similar place within the field of action.

Representations, no matter how distorting in their transcendental conceits, must nevertheless “represent” something. It’s therefore not surprising to discover that, when one ventures beyond the frame of the art world, the historical record admits an impressive number of women—some well known, others lurking in the darkened corners of the archive—who have engaged in political violence. In Labour in Irish History, James Connolly (1987) rummages through the shadows to remind us how riots were often carried out in the name of women leaders. Describing the activities of Irish peasants in the middle of the eighteenth century during the establishment of British enclosures, Connolly recounts how “there sprang up throughout Ireland numbers of secret societies in which the dispossessed people strove by lawless acts and violent methods to restrain the greed of their masters, and to enforce their own right to life.”

They met in large bodies, generally at midnight, and proceeded to tear down enclosures; to hough cattle; to dig up and so render useless the pasture lands; to burn the houses of shepherds; and in short, to terrorise their social rulers into abandoning the policy of grazing in favour of tillage, and to give more employment to the labourers and more security to the cottier. (42)

Connolly mentions that the secret organizations conducting these acts of terror were very diffuse and often disappeared as quickly as they appeared. He does, however, draw special attention to the Whiteboys, a group that sought vengeance and justice in the South of Ireland. Wearing white shirts over their clothes in order to create an ominous uniform appearance while causing havoc at night, the Whiteboys are intriguing from our current vantage for their anticipation of the sartorial strategies favored by the Black Bloc. Connolly’s interest, however, was piqued for different reasons. “About the year 1762,” he mentions, “[the Whiteboys] posted their notices on conspicuous places in the country districts… threatening vengeance against such persons as had incurred their displeasure as graziers, evicting landlords, etc. These proclamations were signed by an imaginary female, sometimes called ‘Sive Oultagh’, sometimes ‘Queen Sive and her subjects’” (42).

Although women are representationally absent from Connolly’s history,

29 they are nevertheless conceptually present as imaginary leaders. The rioting Whiteboys were

subject to Queen Sive, who might therefore be cast as an older sister to Liberté. But what sort of concrete situation might have allowed figures such as these to emerge? We can find hints in the riots themselves. Enclosure meant the separation of families from the land. Historically burdened with the responsibilities of home and family, the women of Ireland’s pre-capitalist peasantry can truly be understood as motive forces behind the enclosure riots. It is therefore not surprising that the tumult should have been carried out in their name. For his part, Connolly presumed that Queen Sive—like her younger brothers Captain Swing and General Ludd—was imaginary. Though the riots may have been conducted

for and

at the behest of Ireland’s women, it did not follow that it was therefore women

themselves who conducted them. But whether or not there was an actual Queen Sive, historians since Connolly—Sheila Rowbotham notable among them—have affirmed that there were certainly women who rioted.

From the eighteenth century onward, there is an observable trend in women’s participation in riots and other forms of political violence. Despite being representationally absent in many historical accounts, Rowbotham (1974) has noted that women were present in large numbers during historically celebrated moments like the storming of the Bastille.

30 Similarly, women were arrested in large numbers when the barricades of the Paris Commune finally fell. Many of them—women like Louise Michel, but also innumerable unknown ones as well—were subsequently exiled or executed.

Describing the early nineteenth century political scene in Women, Resistance & Revolution, Sheila Rowbotham (1974) recounts how women often participated in riots in a manner that reaffirmed their status as women. Since the majority of riots in England during the proto-capitalist period were compelled by what Rowbotham calls “consumption issues,” they were intimately bound to the daily concerns of peasant women’s lives. Torn between an earlier peasant experience and the dynamics of the new conditions, rioters often sought basic necessities. Very often, they would be thrown into action by fluctuations in the price of bread. Describing the tumult of one event in Nottingham in the year 1812, Rowbotham recounts how “mobs set to work in every part of the town.”

One group carried a woman in a chair who gave the word of command and was given the name of “Lady Ludd.” Such actions were half ritual, half political. They came naturally from the role of women in the family. Their organization was based on the immediate community. They did not require a conscious long-term commitment like joining a union or party, nor were they feminist in any explicit sense. (103)

According to Rowbotham, even though these women were resisting the tyranny of their rulers, they were not yet challenging the system or their role within it. Often, peace could be reestablished through the market. With the price of bread set once again at the level determined by custom, things would often return to normal. “However,” Rowbotham points out, “during the nineteenth century the context of the food riot changed because of the development of other forms of political action.” Eventually, “the traditional action of women in relation to consumption became intertwined not only with revolutionary events and ideas but also with the emerging popular feminism of the streets and clubs” (103). In this way, the riot helped to inaugurate new forms of political subjectivity for women. Addressing immediate needs through violence translated, over time, into the capacity to be political and to begin envisioning a future beyond the family-consumption horizon.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the violence of the British suffragette movement effectively transcended the logic of the consumption issue riot. Although suffragettes drew upon the spontaneous feminism of prior moments, the struggle for suffrage saw women riot not so much to preserve that which they required (or to which they felt entitled by custom) but rather to transform themselves into new beings. Through riotous action, women produced the conditions for full citizenship within the representational paradigm of democratic liberalism. Much broken glass and unladylike behavior punctuated these years. Historian Trevor Lloyd (1971) recounts how, in the year 1913, militant suffragettes “burnt a couple of rural railway stations … placed a bomb in the house being built for [British Cabinet Minister] Lloyd George at Walton Heath in Surrey, and … wrote ‘Votes for Women’ in acid on the greens of some golf courses.” What’s more, “these attacks were meant to hurt.”

Previously women who had been breaking the law, whether in a peaceful way or by marching in procession without police permission, or violently by breaking windows or trying to force their way into the Commons, had intended to be arrested in order to show that they took their beliefs seriously, and to make a speech from the dock in defense of their beliefs at the trial. But by [1913] the suffragettes were no longer looking for opportunities for martyrdom. They wanted to fight against society. (89)

Contemporary activists will recognize the transition outlined by Lloyd as bearing a striking resemblance to the recursive interval between the moment of civil disobedience and engagement in direct action.

31 It’s therefore not surprising that, just as in other instances when protestors have moved from martyrdom to confrontation, the suffragettes’ turn to militancy led to harsh criticism. Violent action, many suggested, annulled the benefits of mythic feminine status—that gift that “enabled” women to transcend dirty politics through ontological purity. By refusing the status of both victim and muse, the suffragette became nothing short of a political and symbolic anomaly. She appeared on the world stage by defiantly extricating herself from the rubble of a historic contradiction that has yet to be resolved. Producing a new and intelligible category from the nineteenth century antinomy between “Woman” and “the political” required decisive action. And so, even as they sought recognition from constituted power, the suffragettes nevertheless understood that “Woman” as representational category needed to be more than a myth, a muse, a node in the organization of consumption.

Through systematic and uproarious interjection, this new woman entered history not as an abstract universal but as a conscious actor—a force to be both recognized and reckoned with. According to historian Melanie Philllips, suffragettes like Teresa Billington-Greig began to recognize the ontological scope of their claims when their actions led them into direct conflict with the state. Sitting in Holloway prison for assaulting a cop at a demonstration, Billington-Greig concluded that, since women were denied the rights of citizenship, “logically they had to be outlaws and rebels” (2003: 182). Billington-Greig refused to testify at her trial, arguing that the court had no jurisdiction over those it did not—and could not—recognize as its citizens.

Reflecting on a similar feeling of ontological transformation a few years prior to Billington-Greig’s arrest, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence could not help but to feel inspired. Suffragette action had changed her: “Gone was the age-old sense of inferiority, gone the intolerable weight of helplessness in the face of material oppression… And taking the place of the old inhibitions was the release of powers that we had never dreamed of,” she wrote (2003: 172). Despite the remarkable differences in their objective circumstances, Pethick-Lawrence expressed a sentiment that neatly anticipated the dynamite that Fanon would commit to paper 60 years later.

32 It’s therefore not surprising that, according to Phillips, by 1908 “civil disobedience gave way to threats to public order.” These included “destruction of property such as window-breaking and occasional violence against members of the government” (189).

During this period, many suffragettes argued that violence was not the antithesis of rights (as many liberals had claimed) but rather their precondition . This perspective resonated strongly with leading suffragette Christabel Pankhurst as she witnessed police break up a Manchester labor meeting assembled to address unemployment. Pankhurst concluded that it was only through violence that people would be recognized as people. From the perspective of the rights-granting state, violence seemed to be the precondition to political intelligibility (2003: 174). Arriving at similar conclusions, Frances Berkeley Young noted in 1912 that the actions of suffragettes conformed in every detail to England’s cherished history of struggle for equal rights and liberal freedoms. “Need I recall to any student of history,” Young asked rhetorically, “the serious rioting and destruction of property which has preceded every advance in the liberties of which England is so proud” (cited in Neumann 2001: 111).

The history of the struggles against enclosure and for suffrage makes it possible to question the commonsense that draws logical correspondences between rioting and masculinity. By paying attention to the gender of rioters throughout the history of capitalism in the West, it becomes possible to dispel the myth that rioting has been a purely masculine pursuit. Correspondingly, though it might empirically be the case that women did far less rioting than did men at anti-summit actions, this cannot be said to be the result of some natural—or even some politically expedient—arrangement. Women have been rioters in the past. They have recognized the importance of rioting in pursuit of political objectives and even of political being. And while contemporary detractors of the Black Bloc have done their best to discredit the Bloc’s actions as macho rabble rousing, the historic gender of the riot has been both masculine and feminine.

At the same time, the history of riots from the nineteenth century onward reveals the extent to which the meaning of the category “woman” underwent significant transformations as a result of the emergent relationship between violence and liberal democracy. As Rowbotham explains, “the new conception of commitment” that arose in moments of political violence “could upset what had been regarded as the women’s sphere” (1974: 104). As a phenomenon pertaining to a way of being rather than to a prescribed content (as a concept that enabled people to adopt the standpoint of the project rather than that of a narrowly conceived interest), “commitment” became the vehicle for self-realization and becoming. In this formulation, committed people act on the basis of what their act demonstrably produces rather than on the basis of what it is thought to mean within a fixed frame of reference. Because the social organization of gender relied (and relies) extensively on the register of signification, the turn toward committed action (where recognition is demoted to a place of secondary importance) can be seen as an opening move in the war on gender itself.

As Rowbotham, Young, and others make clear, the history of riots against property and profit has been indelibly marked by women’s participation. It’s therefore not surprising to discover that (despite all claims to the contrary) women were active participants in anti-globalization riots as well. Writing about her experiences in the Black Bloc at demonstrations against the G8 meetings held in Genoa during August of 2001, “Mary Black” goes so far as to directly address the limitations of the riot = masculine equation:

I think the stereotype is true that we are mostly young and mostly white, although I wouldn’t agree that we are mostly men. When I’m dressed from head to toe in baggy black clothes, and my face is covered up, most people think I’m a man too. The behavior of Black Bloc protestors is not associated with women, so reporters often assume we are all guys. (Black 2001)

In her investigation of the ambiguous feminist character of the anti-globalization movement, Judy Rebick (2002) quotes activist Krystalline Kraus expressing a similar sentiment: “‘Blocking up’ to become the Black Bloc is a great equalizer. With everyone looking the same—everyone’s hair tucked away, our faces obscured by masks, I’m nothing less and nothing more than one entity moving in the whole…” (Rebick 2002). However, as Kraus points out, this moment of release from the constraints of gender lasts only as long as the riot itself. Before and after the action, at public meetings and at the bar, movement debates continue to be the preserve of men. But if the riot is a “great equalizer” because of the exigencies of commitment, it’s worth considering how it might also stand as the inaugural moment of a post-representational politics. If the contemporary riot brings with it a moment of gender abolition, where one becomes nothing more than “one entity moving in the whole,” how might we extend its effects into regions of life where the logic of representation remains dominant? Can we enter the space opened up by the riot and never leave it?

Although it’s been the subject of endless political debate, activists have often had difficulty clearly describing what they intend by “inclusion.” Because it’s an ontological and not a political category; because it tends to valorize the filiative bonds of present tense

being over the affiliative impulses of future tense

becoming; because, finally, it traces the movement of entities from spaces of exteriority into some predetermined inside, “inclusion” has posed real difficulties for radical politics.

33 Whether carried out in an aggregative fashion or (with more nuance) in an effort to induce an elected (and often predetermined) self-transformation, “inclusion” has often seemed to assume that the space of inclusion is itself a nearly perfect universal.

In opposition to this perspective, feminist writers concerned with anti-imperialist struggles have shown how inclusion has worked against political projects cognizant of the need to seize power and transform the world. Chandra Mohanty (1995) is unequivocal on this point in her assessment of Robin Morgan’s mid-nineties call for a “planetary feminism.” For Mohanty, the politics of inclusion inevitably leads to an abstract “universal sisterhood” (a condition that reiterates many of the features granted to Liberté). Although envisioned as a container into which all difference can be subsumed, Mohanty recounts how—in practice—“universal sisterhood” has disclosed an uncanny allegiance to the particular interests of white middle class women.

Universal sisterhood, defined as the transcendence of the “male” world, thus ends up being a middle class, psychologized notion which effectively erases material and ideological power differences within and among groups of women, especially between First and Third World women (and, paradoxically, removes us all as actors from history and politics). (77)

Because it removes women from the political sphere, it’s doubtful that “sisterhood” could provide the epistemic or tactical bases for resistance. As an abstract relation prompted by recognition of an equally abstract category, “inclusion of woman” necessitates that the category “woman” be given content. But who will be included? Because the moment of recognition becomes the moment of inscription, women who act in ways that exceed the normative grounds of the category cease to be intelligible. Or, to put it another way, since Morgan’s “sisterhood” presupposes norms that are potentially antithetical to Krauss and Black’s actions; since Krauss and Black seem to act like men and refuse to transcend the field of ruthless masculine politics, “sisterhood” may be left with no option but to expel them from its bounds.

Then again, in a moment of compromise, “sisterhood” might acknowledge the contradictions that arise from its aggregative constitution and make an exception. But what happens to a normative category that allows exceptions? At its logical limit, inclusion of exceptional content makes the category into which the content is subsumed wholly superfluous. By making the distinction between inside and outside (friend and enemy) impossible, “exceptional inclusion” of this kind ends by undermining the minimum requirements of political thought and action. Although inclusion brings with it a number of benefits (and here we might think of the possibility of forging a collective “we” prior to the resolution of contradictions within the assembled body), it also highlights a number of ontological lacunae that cannot be perpetually deferred.

By deferring the resolution of its ontological lacunae, contemporary feminism has been subject to an increasingly frequent return of the repressed. From Sojourner Truth to Audre Lorde, the history of feminist action has been shaped by confrontations with the limits of the category “woman.” These confrontations have for the most part (and up until recently) taken the form of attempts to expand the category so as to include the experiences of those who had previously gone unrecognized. These efforts have been important. However, they bring with them the challenge of determining how to constitute a political “we” at the point where the distinction between inside and outside dissolves. This problem is surmountable; however, it requires that we recognize how the goal of inclusion is itself too narrow to encapsulate the opportunities signaled by the anti-globalization movement’s riotous actions. These events highlighted a place where stable gender categories (and even genders themselves) might begin to fall apart.

In moments like the riot (in moments when people choose to reject, or fail to approximate, established norms), representational certainties begin to unravel. It’s therefore not surprising to find media commentators, state officials, and (occasionally) activists themselves doing their utmost to make the new scene intelligible by inscribing the riot as male. The goal of this work is not “truth” but conceptual intelligibility. And with conceptual intelligibility comes the possibility of induction into the logic of ruling relations. As Mary Black points out, one of the most cherished gender norms applied to women—a norm applied with stunning regularity in both mainstream and popular feminist accounts—is that they are ontologically anti-violent. Because of this, recognizing women in the riot would mean destabilizing the intelligibility of the category “woman” itself.

In mainstream accounts, violence is often viewed as the natural preserve of men. Women are thus cast as victims incapable of mobilizing violence or as muses unwilling to consider it on account of their moral superiority. Given this restrictive framework, it has often been difficult for women to imagine using violence in order to accomplish goals—even when it can be demonstrated to be in their interest to do so. It’s understandable that the patriarchal mainstream has sought, out of sheer self-interest, to make violence unthinkable for women. However, it’s more difficult to grasp why this tendency has been such a recurrent feature of feminist thought.

Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz (1992) has pointed out how dangerous the feminist love affair with the victim has been in light of the need to resist violence against women. While many women do not feel comfortable being violent, Kantrowitz notes, this should not be confused with the idea that women are naturally non-violent or that victim status is the only basis for political recognition. Women, she argues, have been systematically deprived of access to violence—first, by a masculine culture that declares violence to be its unique and sovereign entitlement, and second by a tendency within feminism to draw natural associations between violence and the oppressor. However, for Kantrowitz, “the idea that women are inherently non-violent is … dangerous because it is not true.”

Any doctrine that idealizes us as the non-violent sex idealizes our victimization and institutionalizes who men say we are: intrinsically nurturing, inherently gentle, intuitive, emotional. They think; we feel. They have power; we won’t touch it with a ten-foot pole. Guns are for them; let’s suffer in a special kind of womanly way. (24)

Why has it been difficult for feminists to imagine violence as a viable strategy for political transformation? Why, despite a documented history of women’s violent struggle, have women tended to disavow their capacity for violence? Part of the answer can be found in the representational habit of positing resistance as the logical negation of the thing being resisted. In the case of violence, this means that—since men wield violence against women in an effort to maintain relations of domination—the use of violence by women would only serve to strengthen the logic of domination itself. Rachel Neumann confirms this tendency when she describes the feelings that some anti-globalization activists had with respect to the Black Bloc riot. In her account, protestor violence seems to reiterate existing power imbalances. “Property destruction,” she notes, “has often been linked with larger uses of violence.”

Because of the way that men in particular are taught to repress and vent their anger, it often comes out as an exaggerated representation of masculinity, reproducing instead of contradicting the existing power structure. (111)

According to this logic, by using violence to smash the violent system, activists end by reinforcing the system itself. Here, violence is construed as a logical quantity, a sign that can only be negated by siding with its representational antithesis. But Neumann’s formulation says more about the state of our current political impoverishment (where everything is subsumed within the representational sphere) than it does about violence itself. And while it can be easily transposed into the field of representation, violence itself is not merely a representational act. Its political effects can’t be measured on a balance sheet of stable significations. By abstracting violence from its social context, by distilling it into a representational essence and disconnecting it from the world of lived experience, activists run the risk of foreclosing the possibility of even contemplating the political use of violence.

In order to justify violence’s political inadmissibility, activists have sometimes made use of an idea popularized by Audre Lorde: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (1984: 110).

34 There is no doubt that maxims like these are seductive. However, they rarely provoke a material reckoning with the world. Which tools, precisely,

belong to the master? Furthermore, how did these tools end up in his hands and not ours? Drawing upon a documented history of struggle, Kantrowitz points out that violence has been women’s tool too. To make arguments to the contrary requires deliberate and exhausting self-deception (1992: 23). Worse, the urge to relinquish violence so as to avoid identity with the master reduces

social relations to a constellation of abstract concepts and

resistance to a process of conceptual negation. Such an orientation makes it nearly impossible to imagine a field of struggle that is not bound in advance by the claustrophobic universe of representational logic. Practically, it means that the consolidation of male power leads women toward ever-greater identification with the unattainable transcendental realm.

By positing violence wholly within the purview of a masculinist discourse of social domination, the inverse set of propositions is thus simultaneously secured: by virtue of being the antithetical term, to be female means defining oneself against dominant masculinist practice. Consequently, victimization becomes a central aspect (and defining feature) of the feminine. As a political figure, “Woman” thus becomes representationally coherent by way of her marginality and the restitution this condition solicits from constituted power.

Viewed as a hyperbolic representational negation (victim) or as an un-achievable ideal (muse), “Woman” as we know her today indeed does not riot. History, however, contradicts this claim. In opposition to “Woman,”

women are demonstrably capable of enacting violent and powerful practices rather than simply being their victims.

35 Indeed, the history of violent political struggle since the 1960s is impossible to imagine without recalling the women who refused to be either victims or muses, who refused to live the proxy life of categorical abstraction.

Women’s possibilities for asserting political power have diminished in inverse proportion to men’s historical efforts to encapsulate politically powerful practices within a normative and coherent masculine identity. Unless they adopt “common” tactics, women are left with few options but to valorize the antithetical term of the gender binary.

36 Of these two courses of action, only the former allows us to consider how appropriation of our adversary’s tactics is not simply mimetic. Consequently, laying claim to the capacity for violence is not only about expanding women activists’ arsenal of available tactics. It is, more pressingly, about provoking a breakdown in normative male/female gender designations and relations themselves.

Operating from a region of social subordination to both the state and to individual men, neither women in specific nor activists in general can afford to presume that “violence is violence,” or that the “same thing” in a different context is really the same. Arguing against both the Stalinists and the bourgeois moralists of the 1930s, Leon Trotsky put it like this: “A slaveholder who through cunning and violence shackles a slave in chains, and a slave who through cunning and violence breaks the chains—let not the contemptible eunuchs tell us that they are equals before a court of morality” (1973: 38). “Contemptible eunuchs” notwithstanding, Trotsky encourages us to contemplate political action in a manner that shifts the focus from normative meaning to practical outcome.

Considered in light of our present argument, Trotsky’s position amounts to a commitment to resistance coordinated from the standpoint of powerful social practices rather than from within the predetermined borders of a socially-constituted female subjectivity. Following the argument one step further, we must conclude (along with Trotsky) that those who fawn “over the precepts established by the enemy will never vanquish that enemy” (45). At this point, it becomes clear that the “precept” is not violence (which is normally taken to be the preserve and not the precept of the enemy) but the category “woman” itself.

We can therefore re-read Lorde’s maxim recognizing that, as a tool, the moral precept—the constellation of established normative meanings that reaffirm the status quo—will indeed never dismantle the master’s house. The violence of conceptual abstraction conceals the concrete violence of the everyday world. Nevertheless, it remains evident that the state’s laws cannot be used to abolish the state any more than the production of commodities for profit can ever emancipate the producer.

The implication here is not, as has sometimes been claimed, that women must act “like men” in order to wield violence. Rather, it is that—by appropriating means of powerful political assertion to which they’ve historically been denied recourse—women tell the lie of the normative masculine identification with power. In Gender Trouble, Butler points out how a women’s repetition of a practice currently encoded as male can have the effect of transforming both the practice and the actor into something new. “To operate within the matrix of power is not the same as to replicate uncritically relations of domination,” she says. “It offers the possibility of a repetition of the law which is not its consolidation, but its displacement” (1990: 30). Women’s participation in the Black Bloc suggests as intriguing vector of displacement in Butler’s sense.

Other parallels can be drawn. As a moment of unmediated engagement with history, the riot breaks down individual certainties and encourages the formation of post-representational political subjectivities. In this respect, the riot provides a concrete expression of the disruptions anticipated by the surrealist insurgency that punctuated the early twentieth century. Searching for an avenue along which to launch an assault on the conceptual mystifications of the bourgeoisies, Walter Benjamin proposed in 1929 that—despite its lack of political clarity—surrealism could reconnect people with a zone of experience where things and their names would begin to correspond more directly.

“In the world’s structure,” he posits, “dream [the surrealist’s currency] loosens individuality like a bad tooth. This loosening of the self by intoxication is, at the same time, precisely the fruitful, living experience that allowed these people to step outside the domain of intoxication” (1978: 179). Like in Krauss’s account of her Black Bloc experience, where the tactical exigencies of the riot make a member of the Black Bloc “nothing less and nothing more than one entity moving in the whole,” Benjamin’s analysis emphasizes surrealism’s assault on the representational subject certainties of modern individuality. By passing through the deconstitutive moment, these figures initially intoxicated by dream reach a point of ecstatic clarity. The violent immediacy of the act thus stands as precondition to the production of the critical distance required for mediated analysis. Once unthinkable, the riot produces circumstances in which people begin to change themselves in the process of changing the world.

There are still other possibilities. Readers familiar with Frantz Fanon will undoubtedly recognize the dynamic under consideration as being similar to the one that he recounts in The Wretched of the Earth. In that book, Fanon (1963) describes how the native, upon passing through violence, takes history into his own person and, in the process, rediscovers the capacity to be political. Liberation is made possible by considering avenues that come into view only after the colonized choose that which had previously been unthinkable. Standing at the threshold between the thinkable and the unthinkable is violence. “At the level of the individual,” Fanon claims, “violence is a cleansing force.”

It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect… The action which has thrown them into a hand-to-hand struggle confers upon the masses a voracious taste for the concrete. (94-95)

This “taste for the concrete” moves the newly historicized political subject beyond the realm of representation. Violence rematerializes the world and its social relations. No longer do the oppressed seek the recognition of the colonizer. Their claims to freedom do not need his approval. In his introduction to Fanon’s work, Jean-Paul Sartre marveled at the way the anti-colonial struggle had changed the Algerians’ outlook: Europe was sinking but they didn’t care. All of this confirmed that they were becoming political.

Theoretical considerations and histories of struggle like the ones recounted above will undoubtedly seem remote from the experiences of privileged political contenders that, like the ACME collective, descended on the streets of Seattle in 1999. Nevertheless, from the standpoint of

epistemology, a very similar process to the one described by Fanon was at work in the anti-globalization riot. Many participants seemed to experience mass anti-summit actions as a date with history, an unmediated moment in which they become fully invested in the consequentiality of their actions.

37In addition to the ground clearing made possible by ecstatic action, the anti-globalization riot made a further break with representational politics by not advancing particular demands, by not asking for anything. State officials, whether politicians or police, frequently complained that anti-globalization activists were a cacophonous bunch. They did not seek to meet with leaders; they did not seek particular reforms. They did not even seek positive media coverage—and not infrequently did they attack the vehicles of corporate media outlets. Like a tormented parent dealing with a recalcitrant child, state officials were left to cry out in exasperation: “What do you want?”

The anti-globalization riot served as a means to break with the representational paradigm in one final way. Because of their task-oriented sensibilities (their “commitment,” in Rowbotham’s sense), activists—and this was most true of those who used the Black Bloc tactic—tended toward a uniform appearance that made recognition difficult. Starting from the standpoint of the task, rioters selected appropriate tools and clothes. As with their historic counterparts the Whiteboys, the practical consequence of activist commitment was sartorial uniformity. And, as in the past, emphasis fell not on what the uniform meant but rather on what it enabled.

Because it emphasized engaged and unmediated participation; because it broke with the politics of demand enshrined in democratic liberalism; because it placed emphasis on the politics of the act, where participants aimed to produce their truths directly, the anti-globalization riot uncovered a space where women might cause the kind of gender trouble esteemed by Butler. By helping to destabilize gender categories, rioting women prefigure a world in which the political-representational matrix of gender (where identity is the precondition for both subjectivity and regulation) begins to lose its salience. Even as a hypothesis, such a proposition is worthy of sustained consideration—not least because it provides a means of moving radical politics from its current focus on gender inclusion toward the more radical perspective of gender abolition.

Rather than seeking to include women, activists might use the riot to abolish “woman” as a significant social category. In the process, the category “man”—a category made intelligible only through its binary opposition to “woman”—is also desecrated. Feminists have contemplated this possibility before. In “The Accentuation of Female Appearance,” early twentieth century American feminist Laura (Riding) Jackson (1993) pointed out that, even though women of her period had begun to extend their activities into what had previously been male domains, they also began to aesthetically emphasize their femininity. As the distinctions between men and women began to break down in the sphere of practical activity, they became increasingly codified in the sphere of representation. As “the female role becomes more and more extended,” Jackson noted.

the dramatic duality of woman becomes more and more emphatic. And this duality is not only insisted on by women; it is equally insisted on by man. For if woman, as such, disappears from the drama, the drama itself collapses.” (114)

In this case, disappearing “as such” from the drama meant disentangling oneself from the binds of signification. Alternative representations, though they are often important, can only change what people perceive. In contrast, by abolishing representational distinctions through productive practices, activists could foster a radical break with the representational paradigm underlying contemporary ruling regimes. In this way, they could contribute to changing how people perceive.

More immediately, breaking with the representational paradigm challenges the centrality of identity to contemporary politics. These politics, although important for the developments they’ve entailed, have never been without contradiction. And, as most activists will attest, these contradictions have often been immobilizing. But while there have been numerous content-based critiques of identity politics over the last twenty years, it took Butler to point out how identity—since it provides the basis for social recognition—is itself a regulatory practice.

In Gender Trouble, Butler asks: “what kind of subversive repetition might call into question the regulatory practice of identity itself ” (1990: 32). Although she does not consider it, women’s participation in the Black Bloc is such a repetition. By circumventing the representational sphere and attacking the epistemic basis of political identity, and by recasting politics as a practice of production rather than one of signification, Black Bloc women anticipate a moment beyond the recognition-regulation matrix of today’s society of control.

To be clear, since they begin from within it, Black Bloc rioters cannot pretend to possess a tidy means of transcending representational stipulations. However, their practices do seem to unsettle some of these stipulations’ most cherished principles. By emphasizing unmediated engagement, a critical approach to the politics of demand, and a celebration of the act, the rioters’ commitment makes gender representation (and hence gender itself) less tenable. And so, while anti-globalization riots were not always tactically efficacious, their significance may in fact reside elsewhere. And so, while it doesn’t accord with the disciplined messaging of contemporary movements, we must keep the possibility of gender abolition in mind as we enter the next cycle of struggle. To the extent that this possibility was made visible during the anti-globalization movement, it stood as a meaningful prefiguration of the world we are struggling to create.

In this world, we can imagine subjects without identities and politics unbound by the stale conventions of recognition. These politics are made possible by a violent assault on conceptual abstraction and—their capitalist outgrowth—property relations. This is especially the case when conducted by a “woman” who is herself a conceptual outgrowth of those very relations. Most importantly, these politics anticipate a people who will exist whether or not we are represented. Through our activity, the world itself will confirm our being.