CHAPTER 4

ON JANUARY 1, 1945, Hans Heinrich Fuge, head (Lagerleiter) of the Dzierżązna subcamp, reported positive tidings regarding the state of affairs on this agricultural estate 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) from Łódź.1 The Dzierżązna subcamp of the Polish Youth Custody Camp of the Security Police (Polen-Jugendverwahrlager der Sicherheitspolizei) in Litzmannstadt, opened in early 1943, held two hundred prisoners at its high point.2 This small and little-known camp was still operational on the date of Fuge’s report, New Year’s Day 1945.3“In the residential building of farm II, all the stairways were fixed and the house freshly painted. The heating system for the chicken coop, laundry room, and workshop was repaired and the flooring replaced in all the areas referred to,” wrote Fuge. “We did all the above-mentioned work by ourselves, without any outside help,” he added, meaning, we can presume, the adolescent Polish inmates of the camp performed the described labor.4 At the time of his report, with the war lost and the Third Reich months from collapse,5 Fuge seemed blissfully or perhaps willfully unaware of how bankrupt the racial ideals of the Third Reich had become. In condescendingly describing his so-called pupils (Zöglinge), he noted (twice) that the Polish people suffered from a disinclination to work (Arbeitsunlust) and that his “pupils” were no different. “One must bear in mind,” he wrote, “that the workers involved are only Poles, who accomplish nowhere near what a German worker does. The Polish pupils also are not to be rated as full-fledged workers, as they are youngsters (girls) twelve to fifteen years old.”6

The year 1945 marked the demise of the Nazi and Axis regimes and a rebirth for liberated nations and peoples caught up in World War II and the Holocaust. Thus far, scholars have paid great attention to the notion of a Stunde Null, or “hour zero,” for Germany as a nation and for former Nazi sympathizers, collaborators, and Germans not targeted by the Nazi regime.7 Documents held by the International Tracing Service (ITS) allow us to view 1945 through a variety of lenses, not just from the perspective of a vanquished Germany or of humbled former Nazis and their beneficiaries. As we have seen in previous chapters, what Daniel Blatman terms “the Nazi oppression machine”8 produced victims among all the nationalities in Europe, Jewish and non-Jewish, caught up in all manner of camps and prisons, forced military service or forced labor, or in hiding. The year 1945 saw the liberation of all these sites of terror, unjust punishment, and utter brutality. Millions of victims in poor mental, physical, and emotional health fell to the care of bewildered Allied forces, governments, and aid organizations. The year also saw the first efforts to recover, rebuild, return, and consider retribution. The period from January 1 to December 31, 1945, is a remarkable analytical lens through which to view a Europe in the remaking.

In a secret January 3, 1945, report provided to Supreme Headquarters/Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) by the British War Office, a “Polish officer,” never identified by name, tried to describe what he had heard about the gas chambers in Auschwitz.9 In what we now know is an inaccurate account, he wrote, “The condemned prisoners, usually Jews, are first given a hot bath to open the pores of the skin and are then herded into a large room equipped with overhead sprays.”10 The author had never been in the Auschwitz camp complex himself, and the War Office was skeptical about the reliability of the details in the report. A cover letter remarked, “No attempt has been made to evaluate the information contained in it and no guarantee of its accuracy can be given.”11 The report is not historically valuable for its accuracy, as the reference to Jews being given a “hot bath” before their murder in the gas chambers of Birkenau already tells us it is flawed. However, the manner in which this anonymous Polish officer described the so-called Sonderkommandos12 of Auschwitz, at this late date in the extermination process, is fascinating:

The bodies are cleared from the room by a special squad of prisoners [. . .] composed of Jewish men selected for their strength and physique. They serve a three months [sic] tour on gas chamber duties and during that time receive excellent treatment. Working hours are short, discipline lax, food and tobacco in abundance. At the end of the 3 months they in turn go into the gas chambers and in due course their successors tumble their bodies into the furnace. Nevertheless in spite of this grim condition, there is never any lack of volunteers for the gas chamber squad and the camp guards can pick or choose at their will from the innumerable applicants.13

This inaccurate report—out of context and even accusatory, with its mention of no “lack of volunteers for the gas chamber squad” and guards who could “pick or choose at their will from the innumerable applicants”—was disseminated to a long list of SHAEF14 offices in sets of multiple copies in the first days of 1945.15 It gives us a sense of the distinct lack of empathy Jews who managed to survive the Holocaust would face in the long months ahead.

In the last days of January, forty-year old Gertrud Leppin worked at the post office in the small German village of Sonnenburg (today, Słońsk, Poland). A Berliner by birth, as a so-called Mischling (person of “mixed race”) born to a Jewish mother, she moved to Sonnenburg in November 1943 because her former home was “bombed out” and she “did not want to get into trouble” on account of her racial status. She lived at Münzstrasse 21, “200 meters [656 feet]” from the town’s prison. “Sonnenburg is a small place in which the prison played a large role,” she testified.16 Established in the early nineteenth century as a royal Prussian penitentiary, it was located 600 meters [1,969 feet] outside the town on the major road leading to Poznań. Able to hold “637 inmates” and “economically significant for the town,” the prison was closed in 1931 “due to catastrophic sanitary conditions.” In early 1933, it became one of the first Nazi concentration camps; by 1945, it had returned to its function as a penitentiary.17

Leppin recollected the penitentiary as quite full that bitter winter. She guessed that approximately a thousand prisoners were incarcerated there and worked either in the town or in surrounding villages, sometimes with and sometimes without supervision. She thought it was the night of January 29 or 30 on which she heard gunfire and assumed Russian troops had arrived. But she did not hear machine-gun fire; rather, she heard single shots, one after another, over two or three hours. She opened her window and, hearing no more shots, walked out of her house toward the prison. “I could not hear any cries,” she wrote, but she verified that the shots were coming from the penitentiary. Upset, she went to her neighbors, then to her in-laws, but could learn nothing. So she went to another neighbor, one “Schenkwitz,” a guard at the penitentiary, and asked him “what was going on” (was los war).18

Schenkwitz was packing. “SS,” he told Leppin, were shooting political prisoners (politische Gefangene). In fact, he told her, the SS ordered the regular staff of the penitentiary to take part, and they (he claimed) “all refused.” She was not able to ask Schenkwitz further questions as he was “very upset” (sehr aufgeregt) and in a hurry to leave (wollte schnell weg). She felt the need to add that Schenkwitz was “no National Socialist.” On the following day, she heard that “all the SS together with the wives of the high-ranking regular prison staff” had fled. Local German Sonnenburgers would have been glad to go with them, she claimed, but the SS left them behind. Russian troops arrived on February 2, 1945. They told Leppin that “the SS” had “committed atrocities” in the penitentiary; bodies were piled up on the ground and in the cells. Not one prisoner survived, they said. Rumors circulated in the town that beyond the “815” “political” prisoners, the “SS [had] murdered women and children from Grodno.” But Russian troops did not confirm this, Leppin noted in her affidavit.19

Leppin did not have it exactly right: in fact, the shootings took place on the night of January 30 and into the early hours of January 31, 1945. The victims were not women and children from Grodno but rather male detainees from Belgium, Denmark, France, Holland, Luxemburg, Norway, Poland, Russia, Ukraine, and Yugoslavia. The number of prisoners murdered on that night, as cited to Leppin by Russian soldiers, was approximately correct (in the neighborhood of eight hundred). Following the transfer of approximately eight hundred so-called Night and Fog prisoners20 out of Sonnenburg to Oranienburg on November 11, 1944, prisoners sentenced by Wehrmacht military tribunals for desertion took their place. Gestapo men, who controlled the prison, did the shooting.21 Leppin’s testimony illustrates a different point: the brutality and chaos of that time and the response of local Germans to open murder in their midst, which, generally speaking, ranged from a lack of intervention to participation.

ITS holdings are rich in material pertaining to gender and the Holocaust, including but not limited to the role of women from small towns, eager for opportunities and adventure that led to collaboration in the Nazi system.23 In Ruth Kleinsteuber’s experience, even in the early months of 1945, for Germans the Nazi oppression machine still brought career opportunities for those not targeted by the regime. Born in 1922 in the small town of Aschersleben (Saxony), Kleinsteuber began to work in the local textile factory, the Junkers Werke, as an embroiderer in 1936. She was fourteen. Eight years later, in December 1944, the factory manager asked her whether she might be interested in training as an SS Aufseherin (prison guard). She was indeed interested. Dressed in a grey SS uniform and trained for four days at the Ravensbrück concentration camp, in mid-December 1944 she was assigned to the work education camp (Arbeitserziehungslager)24 Nordmark in Kiel (Schleswig-Holstein).25 In February 1945, she was promoted from guard to platoon leader and, by her own testimony, essentially functioned as overseer of all the female guards (Oberaufseherin), with authority over approximately one hundred female inmates.26 “Most of the female prisoners had to work eight to ten hours per day with a mid-day break of one, and later one-half hour,” she stated. As to mistreatment of prisoners in that camp, she had “never seen a female guard beat prisoners. But female guards, whose names I can no longer remember, told me they slapped faces of female prisoners,” she added. As to her own behavior, she wrote, “I myself have boxed the ears of two prisoners slightly.” She acknowledged that most of the guards, male or female, “carried wooden sticks in camp.” She claimed not to have done so herself. In January 1945, within her first month at the camp, she saw a male guard “beat a female prisoner.” “I believe,” she added, “he had a stick in his hand. But it was none of my business.”27 British officials did not agree and tried her for war crimes in Hamburg in 1947. It is a case in point of a young and ambitious German woman who, even in early 1945, with the war lost and the Nazi regime weak and discredited, was willing to take part in its terror apparatus.

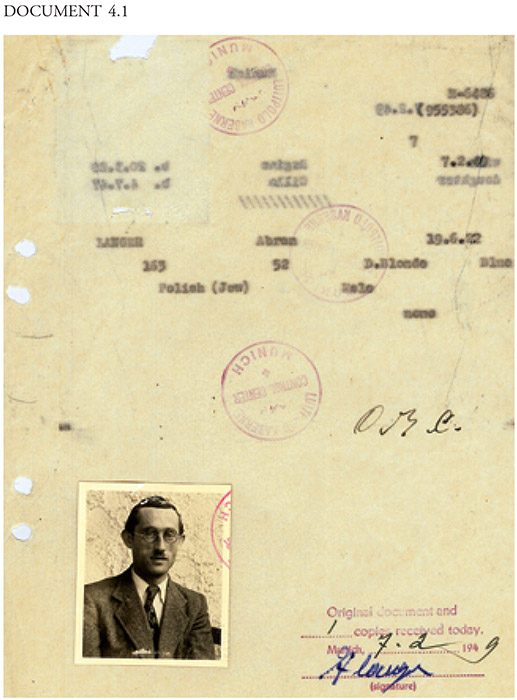

On January 27, 1945, US Air Force Lieutenant John C. Brown was marched with other prisoners of war. (POWs) from the famous Stalag (Stammlager) Luft III near Sagan28 (now Zagań, Poland) to Spremburg “in the snow, rain and regular winter weather of Silesia.”29 “I arrived at Nure[m]berg with the first group to set up the camp, and here I stayed until we marched out of there on the 4th of April,” he wrote.30 “In this time I had three showers, one of which was a delousing shower.” “The conditions were rotten,” he added, and one has to smile at his American euphemism. He went on to describe the lack of adequate food and shelter. In fact, prisoners “tore down outside washhouses to provide fuel for cooking and heating.”31 Abraham Langer (see document 4.1.32) was incarcerated in the forced labor camp for Jews in the forested village of Kretschamberg/Kittlitztreben in Silesia when he and other prisoners33 were marched to Buchenwald in February 1945.34 He had arrived in the Kretschamberg/Kittlitztreben camp in March 1944.35 He was one of nearly one thousand prisoners on the long march to Buchenwald.36 Due to the impending arrival of Russian troops, German inhabitants of Kittlitztreben were evacuated at 7 a.m. on the morning of February 9, amid the chaos of German aircraft firing on Russian tanks. Elderly villagers and women with small children were allowed to evacuate via train. One local villager’s otherwise detailed account makes no mention of the huge column of prisoners who were also evacuated. The account does mention two villagers from Kittlitztreben who perished: Charlotte Glauer, the local butcher’s daughter, and Berta Stammwitz, who both died of heatstroke in the train station.37

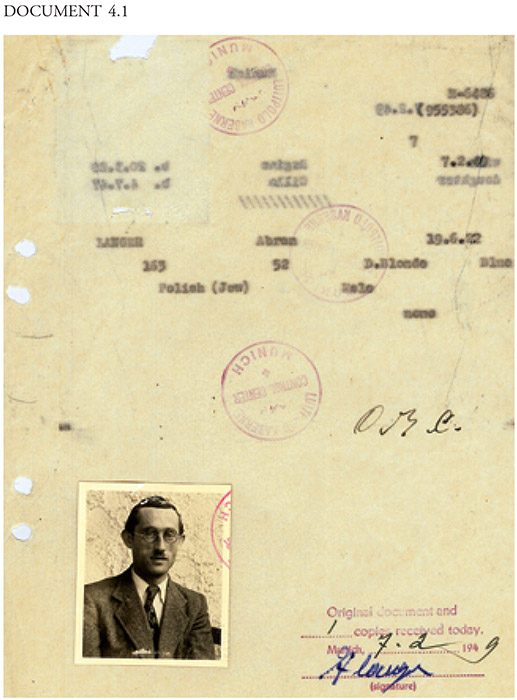

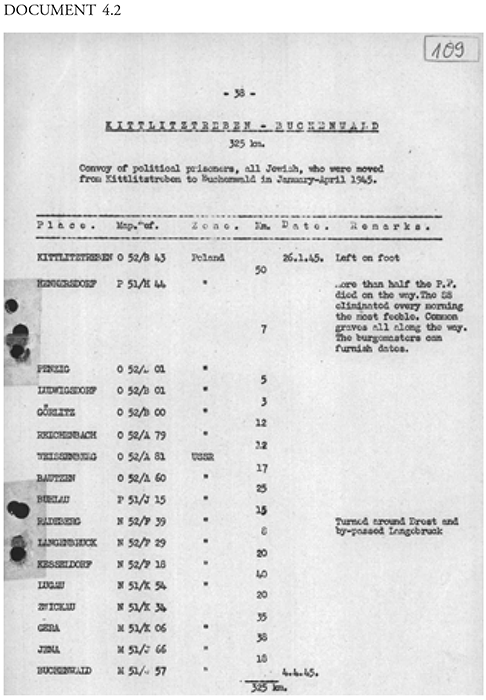

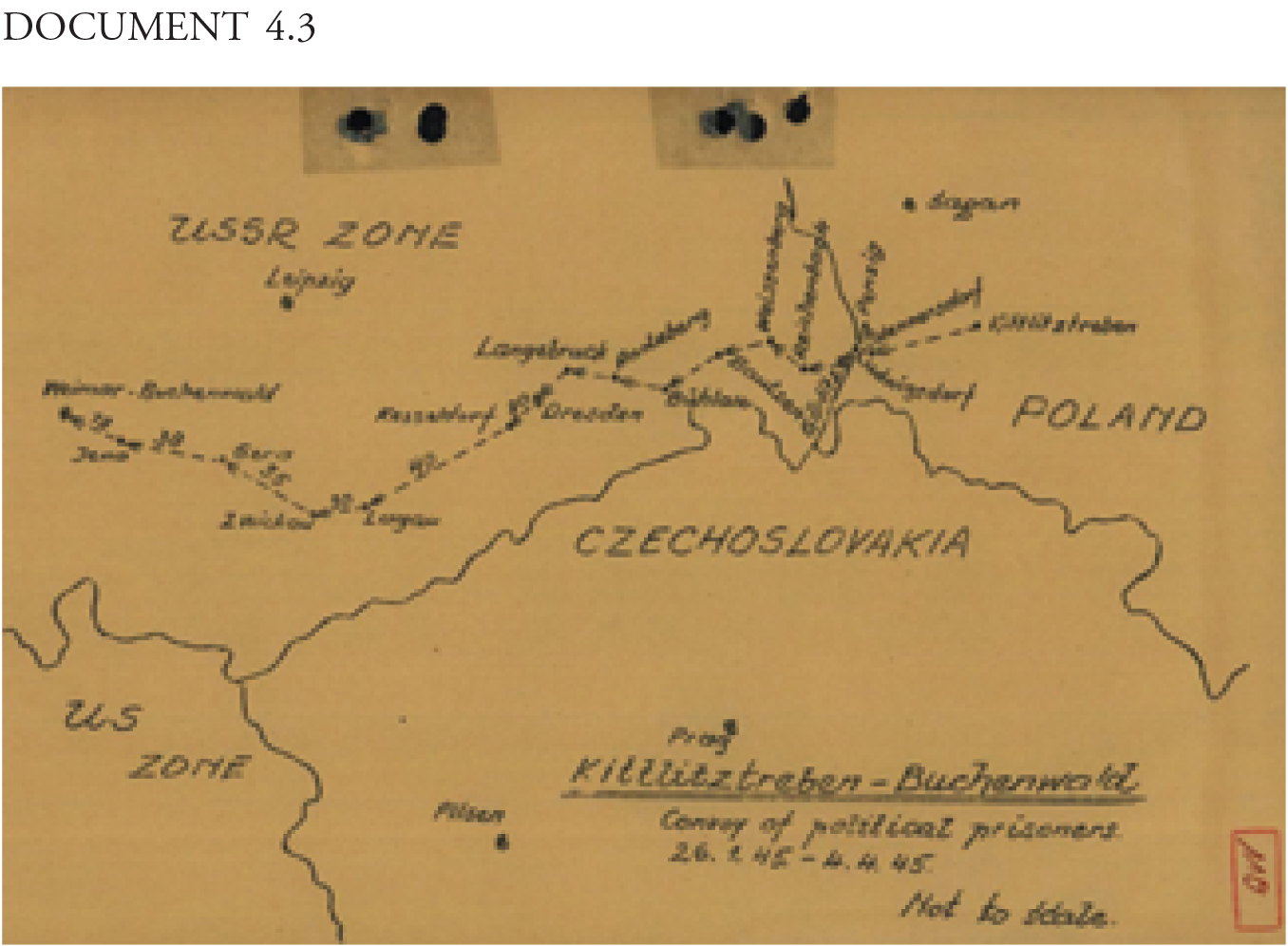

As to the Jewish prisoners, because of ITS documents, we can reconstruct this death march with some precision. (See documents 4.2 and 4.3.38) The death march from Kittlitztreben to Buchenwald, a distance of 325 kilometers (202 miles), consisted entirely of Jewish prisoners. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) Central Tracing Bureau investigations cite a start date of January 26 rather than February 9.39 All sources agree that the prisoners reached Buchenwald on April 4, 1945. In all, the prisoners made sixteen stops after setting off from Kittlitztreben on foot: first Hennersdorf, then Penzig (Pieńsk), Ludwigsdorf (Ludwikowice Kłodzkie), Görlitz, Reichenbach (Dzierżoniów), Weissenberg, Bautzen, Bühlau, Radeberg, Brest, Kesseldorf, Lugau, Zwickau, Gera, Jena, and finally Buchenwald.40 UNRRA investigators noted, “More than half the prisoners died on the way. The SS eliminated every morning the most feeble. Common graves [are] all along the way. The mayors [in these villages and towns] can furnish dates.”41

The camp commandant at Kittlitztreben, recollected Langer, was SS Oberscharführer Otto Weingärtner.42 Weingärtner was, said Langer, “about twenty-eight to thirty years of age, tall, slender, black hair, [with] a scar on [his] right cheek.” Weingärtner “killed two Jews during the march on February 9, 1945. The name of the one was Berek Wellner, I saw it with my own eyes,” Langer said. “Five weeks later I saw that [Weingärtner] shot [a prisoner named] Ziegler.” The “prisoner chief of the barrack, Chaim Zylberberg,” also behaved murderously, according to Langer, who said Zylberberg “was especially angry” with Hungarian Jews. “During the march from the camp [Kretschamberg] to Buchenwald [. . .] Zylberberg was in charge of barrack five, while I was assigned to the sixth barrack,” Langer continued. “I saw that Zylberberg struck with a big stick chiefly those who fainted during the march. The mistreated persons were put on a wagon and brought to the next barn where we passed the night. Daily many of them died. Before we arrived at Buchenwald, he [Zylberberg] hurt the prisoner Leichter, who died the following day.”43

When Langer arrived at Buchenwald, the camp was days from liberation. Liberation was a moment no one could forget, and among the most poignant testimonies are those taken by Allied soldiers in the days immediately following their arrival in the camps. Captain Alfred T. Bogen Jr., assistant army inspector general, First US Army, took one such testimony at the 51st Field Hospital in Nordhausen44 on April 14, 1945. Captain Bogen interviewed Christian Guy, a Belgian prisoner from Malines (Mechelen) brought from Gross-Rosen to Nordhausen via open railway car in February 1945, who had been there ever since.45 In Guy’s recollection, Allied bombs began to rain on Nordhausen “at 4:30 on April 3,” and on April 4 he and several hundred other prisoners hid themselves in a cellar. Here they remained, subsisting on bread pilfered “from the German kitchens.” On April 11, “in the morning, one of the boys came in and like a madman called, ‘There is an American with a car against the gate.’ All the comrades in the cell[ar] started yelling and weeping. They were mad. I could not move at the moment or believe it. I was astonished but a few hours later I had to accept it. The day after this we were taken away to city houses and then I was evacuated to this American field hospital.” He then added, “I am glad you arrived and wish you all success and hope that you get as many Germans as you can. I am sorry I cannot help you boys to do my part.”46

Stunned and disconcerted liberating armies and their helpers struggled first to size up the situation in a given camp and then to act. ITS-held documents contain many reports written by Allied authorities that summer, giving their impressions of those first days of liberation and the many problems that would follow. The report by Miss I. Hillers, active in the Prisoners of War and Displaced Persons Division of the British Red Cross Society at the Sandbostel camp,47 is a case in point.48 British troops liberated the camp on April 29, 1945. Hillers composed this particular report on the basis of “war diaries of all medical units operating in the British Liberation Army from April to June, 1945.”49 Father Dewar-Duncan, Medical Unit 10, Casualty Clearing Station, wrote, “As you can appreciate things in Sandbostel in May 1945 were rather chaotic and it may well be that a mistake in identity could have occurred. The patients in their weak state would very often change beds, and with an inadequate staff and the added difficulty of language it was sometimes impossible to keep track of who was who.”50

“Typhus and open T.B. [tuberculosis] were rife,” a member of the Medical Unit 11 Field Dressing Station wrote, adding that “typhus, T.B. and [the] unclassified sick were segregated and identified by the employment of yellow, blue and pink labels tied to the person. This proved very necessary owing to the wandering propensities of many patients who[,] in spite of their weak condition[,] would step out of bed and wander about in the nude.”51 Thousands of such testimonies and early reports, written from the viewpoints of both the liberated and the liberators in the days and weeks after liberation, span the range of sites of detention in the ITS holdings. The ambitious scholar might consider a monograph-length study of prisoners’ impressions in these first days of liberation as portrayed in ITS-held documents.

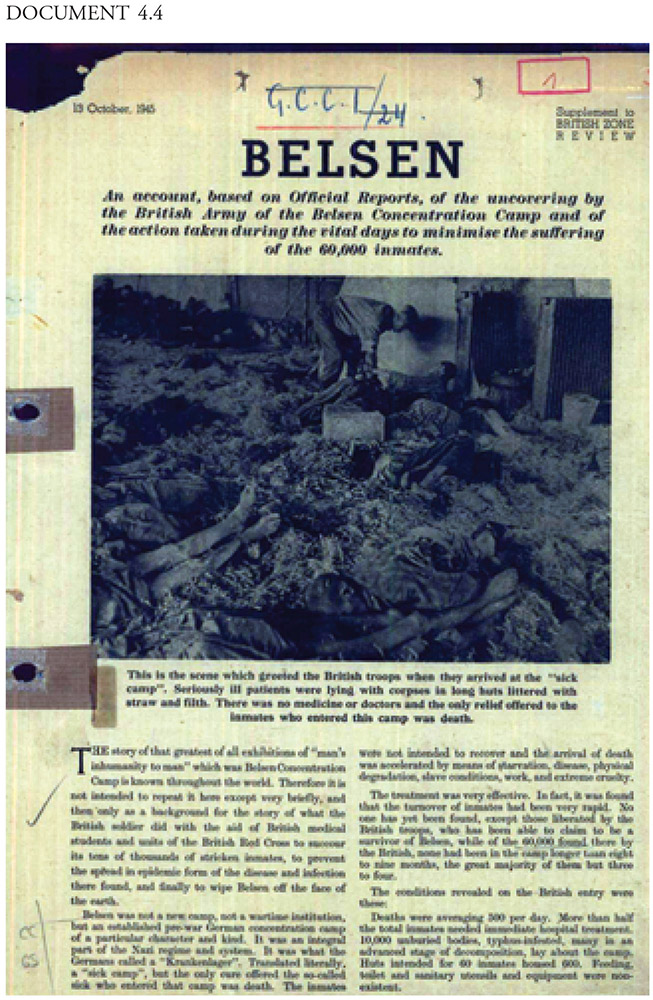

ITS-held documents detail mass death and convalescence in the camps within the first month of liberation. A copy of the supplement to the British Zone Review titled “Belsen,”53 available in the ITS holdings, is a case in point.54 When British troops liberated Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945, they estimated that sixty thousand prisoners were in the camp.55 (See document 4.4.56) “The conditions revealed on the British entry,” notes the supplement, “were these: deaths were averaging 500 per day. More than half the total inmates needed immediate hospital treatment. There were ten thousand unburied bodies, typhus-infested, many in advanced stages of decomposition strewn about the ramp. Huts intended for 60 inmates housed 600. Feeding, toilet, and sanitary utensils and equipment were non-existent[. . . . T]here had been neither food nor water for five days preceding the British entry. Evidence of cannibalism was found. The inmates included men, women and children.” We read, too, a not uncommon description of the prisoners themselves: “The inmates had lost all self-respect, were degraded morally to the level of beasts. Their clothes were in rags, teeming with lice, and both inside and outside the [prisoner] huts was an almost continuous carpet of dead bodies, human excreta, rags and filth,” stated the supplement.57

From this chaos and human misery, Allied authorities began to create stability. Convalescence is an interesting and understudied aspect of that summer of 1945, and ITS-held documents are rich with material on this very specific aspect of prisoners’ experience.58 One way to approach this issue would be to study the voluntary agencies that approached UNRRA and subsequently the International Refugee Organization (IRO), offering their services. There were many such agencies, including national-level Red Cross offices and national and international Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant faith-based agencies such as the Church World Service,59 the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA)/Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA)60 (see document 4.5.61), the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee (UUSC, formerly known as the Unitarian Service Committee),62 and many others, such as the Jewish relief agencies referred to in chapters 1 and 3.

ITS holdings describing the work of the Child Projects Department of the UUSC capture well the mission of such voluntary agencies. “The time between [children’s] liberation from Nazi terror and their final placement will be very decisive for the future development of displaced children, determining whether they will become healthy, happy individuals, delinquents or neurotic wrecks, and whether they will prove an asset or a danger to society,” wrote Ernst Papa-nek, director of child projects for the UUSC in the summer of 1945.63 (See document 4.6.64) Margaret J. Newton, child welfare specialist for UNRRA District Office No. 2 in Wiesbaden, was delighted and accepted the offer of help. “We have just received your letter informing us that staff would be available from the Unitarian Service Committee. We would be grateful for the services of six or seven workers, who would be used as case workers with United Nations65 children living in German families or in German institutions. We have a real need for additional help,” she wrote.66

In the summer of 1945, Jewish refugees, including Jewish children, faced antisemitism still. “The U.S. Zone has been working for several weeks on the location of unaccompanied children who might be eligible for haven under the invitation extended by the British government,” wrote Vernon Kennedy, Director, American Zone Austria, to E. Rhatigan in UNRRA’s Frankfurt office on August 16, 1945. “As you know,” Kennedy continued, “the English offer includes 1,000 children under the age of 16 years who have been in concentration camps[. . . . A] high percentage of these children are Jewish. We want to be sure that this is understood by the British government before the children are moved.” Kennedy was also sensitive to the needs of German Jewish children, adding, “First consideration should be given to children from concentration camps, including children of enemy nationality who were in concentration camps as a result of racial or political persecution.”67 Even after the Holocaust, Jewish children could still be hard to place and, when finally given a home, were not always welcomed.68

The summer months of 1945 saw the return of some of those children kidnapped by the Nazis and subjected to so-called Germanization as part of the Lebensborn program (see chapter 1).69 In July 1945, Polish aid workers came to the home of Therese Grassler in Salzburg, Austria, to take ten-year-old Henderike Goschen70 back to her native country.71 Therese met Henderike in August 1943, when the latter was eight. On August 23, at the Regional Youth Office Salzburg, claimed Therese, “I picked out the eight and half year old girl Henderike Goschen.” Therese was told, she claimed, that Henderike “was an orphan from the German east who had lost both parents.” The little girl “looked quite different from the children in this part of the country; she was short and squat, had dark blond hair, but her eyes were blue.” When questioned about the child’s Polish heritage, Therese responded, “Henderike told me that she came from the vicinity of Lódź [and] that she had been in an orphanage there.”72

Henderike was a Polish child kidnapped and turned over to the Lebens-born. Therese acknowledged this in a roundabout way only, telling US Assistant Defense Counsel Ernst Braune, “Whilst the arrangements were being made for transferring the child to a foster home, I had no dealings with the Lebensborn society, and all arrangements were made by the Regional Youth Office [Salz-burg] exclusively. Later on I was never approached by the Lebensborn but for one exception: I once received a letter from the Lebensborn asking how the child was behaving with me. I did not reply to this as I did not know what the Lebensborn really was, and since then I heard no more from them.”73 Their parting in July 1945 was a difficult one for Therese and, according to her foster mother at least, also for Henderike.74 After being taken from her temporary home with Therese in Salzburg, Henderike was placed in a children’s home in Łódź, where she was reunited with her brother.75 As mentioned in chapter 1, the Nazi Lebensborn program is a new and growing subject of study by scholars, accompanied by memoir literature by Lebensborn children. These memoirs have yet to be systematically analyzed for the impact of the Lebensborn program on the children affected, their adoptive parents, their families of origin, and their own siblings and children when this family history is unearthed.76

As loved ones sought one another, governments sought their missing nationals, and the Allies sought perpetrators and collaborators, practical frustrations and difficulties abounded. A mention of the various tracing service structures in existence by the end of 1945 is necessary here. In 1944, UNRRA (discussed in chapter 1) had already proposed both establishing national tracing bureaus (NTBs) like the existing British Red Cross Tracing Bureau and also setting up one central tracing bureau. No agreement on the proposal was reached until April 1945, and in the meanwhile some countries set up NTBs. Key NTBs included the British Red Cross Tracing Bureau in London; the Belgian Service d’Identification et de Recherches, established by the Commissariat Belge au Rapatriement in June 1944; the Commissariat au Rapatriement of Luxemburg, established in August 1944; the Polish Red Cross–founded Biuro Informacyjne, reopened in April 1945; the Bureau National Français des Recherches, established in the summer of 1945; the Informatiebureau van het Nederlandse Rode Kruis, established by the Netherlands Red Cross in September 1945; and the Central Location Index. Still others were established in 1946 and thereafter.77

On April 27, 1945, SHAEF “officially assumed the responsibility for the processing of tracing” and, the following month, established its Tracing and Locating Unit in Versailles. Then tiny, this unit was “supervised by a representative of the UNRRA liaison staff.”78 On June 28, US forces active in SHAEF moved to the headquarters of the US Forces, European Theater (USFET), located in Frankfurt am Main.79 USFET headquarters opened on July 1, 1945.80 SHAEF was dissolved in mid-July 1945 along with its Tracing and Locating Unit. Its responsibilities passed to the Combined Displaced Persons Executive (CDPX) of the Allied Control Council.81 CDPX in turn comprised two parts: the Central Records Office and the Central Tracing Bureau.82 UNRRA staff worked within the CDPX.83

Lack of staffing was a grave problem. “On 26 June there were five members of the [CDPX-run Central Tracing Bureau] staff; to this number six were added on July 3, four from 4 July to 20 August, and eleven on 23 August,” noted one report.84 Further, the proliferation of different national offices and the near-constant mutation of a central tracing effort caused much confusion. Chaos often reigned supreme that first summer. On August 25, R. Oungre of the UNRRA office in Neuilly-sur-Seine (a western suburb of Paris) wrote to Colonel A. H. Moffitt in the USFET headquarters in Frankfurt. (See document 4.7.85) “I should like to take the opportunity of asking whether I should direct my enquiries regarding lost relatives to you or to Miss de la Pole who, we have been told, is in charge of the tracing bureau, but from whom we have never received any reply,” wrote Oungre.86 Even routine matters like mail delivery were problematic. “You will observe that this letter was written on the 17th of May [1945], posted through the US Army Postal Service on the 22nd of May. It does not appear to have reached this country until the 30th of July,” wrote Colonel L. W. Charley, deputy chief programs officer, Displaced Persons (DP) German Planning Branch in the United States, writing to E. E. Rhatigan at UNRRA’s Frankfurt office. “It will be interesting to know where this unconscionable delay has occurred,” he added.87 Challenges were far greater, of course, than the lack of a speedy postal system.

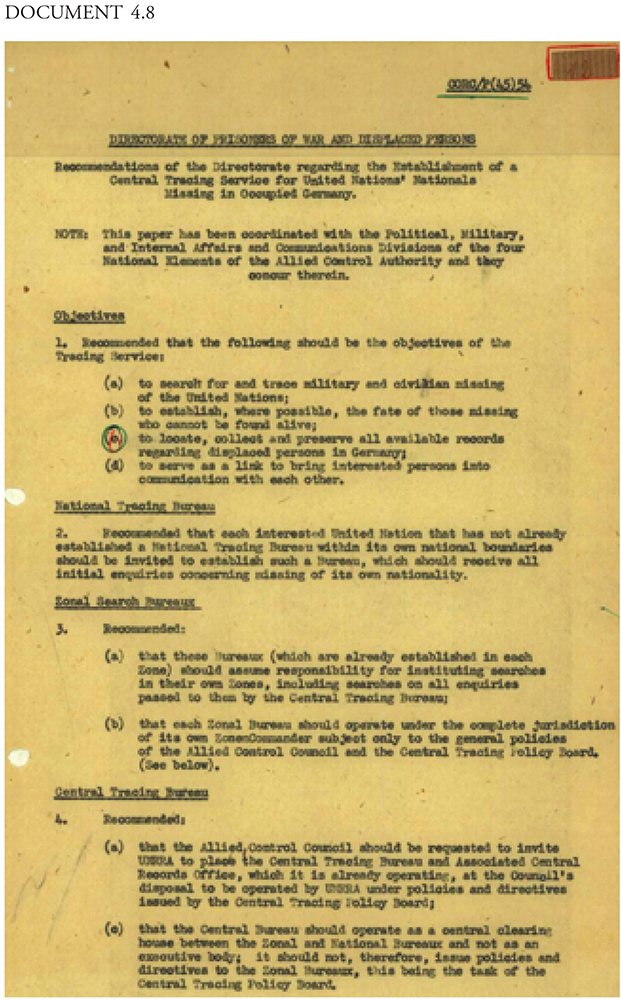

In August 1945, various actors hardly knew whom to write in their pursuit of the missing. By summer’s end in 1945, the American, British, French, and Soviet counterparts of the Allied Control Council in Berlin-Schöneberg found they could agree on establishing a much-needed Central Tracing Service.88 (See document 4.8.89) Issued September 13, 1945, directive CORC/P (45) 54 established such a service with four objectives: (1) “to search for and trace military and civilian missing of the United Nations”; (2) “to establish, where possible, the fate of those missing who cannot be found alive”; (3) “to locate, collect and preserve all available records regarding displaced persons in Germany”; and (4) “to serve as a link to bring interested persons into communications with each other.”90 The CDPX was to be dissolved on October 1, and UNRRA would then assume responsibility for the newly created Central Tracing Service.

Here was the size of it: “Although it had been clearly requested that a staff of 89 would be necessary before 1 October 1945 when UNRRA was to assume the entire responsibility for the operation, only 34 UNRRA employees were available at that time, assisted by six Class II employees and 18 displaced persons.”91 The UNRRA Central Tracing Bureau was formally established on November 16, 1945, subordinate to the Allied Control Council’s Central Tracing Policy Board.92 Then and in the years ahead, Allied authorities struggled to keep accurate lists of DPs, both inside and outside camps.93 (See document 4.9.94) ITS-held documents leave one with a sense of the overwhelming nature of the task, at the level not only of heads of state or major international relief organizations but also of ordinary men and women facing this work daily. (See document 4.10.95) “Search activities in Belsen [. . .] began in December 1945,” wrote Lieutenant H. François Ponet, the French search officer in that camp. “Originally the number of enquiries [. . .] averaged thirty to forty a week,” he wrote. They would quickly increase to over one hundred per week. “It soon became obvious that with the means at my disposal, that is two employees, I could not cope effectively with the number of enquiries I was receiving,” he lamented. “The enquiries [. . .] necessitate a number of investigations and check[s], and it proves impossible for only three people to deal with more than three or four cases a day, if these are to be investigated with accuracy and thoroughness,” he acknowledged.96

ITS-held documents illustrate the role of prisoners both in administering the Nazi concentration camp universe and, after war’s end, in aiding the Allies to rehabilitate former prisoners. Not yet examined by scholars is the role that former prisoners themselves played in the tracing process. A case in point is the International Information Office (IIO) at Dachau.97 Its amazing story begins with the so-called camp registration office (Lagerschreibstube), “as old as the camp itself, the first records [originating] in 1933.”98 As of November 1, 1944, the “first camp writer [clerk]” for the Lagerschreibstube was Dachau prisoner Jan Domagała. Working with him were “three camp messengers, one Pole, one German, and one Austrian.” In the days before Dachau was liberated on April 29, 1945, these prisoners hid the original records from camp authorities to save them from destruction, an act of tremendous resistance and bravery given the violence of those last days of Nazi domination. A report on the history of the IIO describes this chain of events thusly: “At the camp’s liberation, the first camp writer [Domagała] understood [the need] to save the records of the Lager-schreibstube, excluding only a few camp records [. . .] as the SS destroyed all files of other offices. The Lagerschreibstube was in possession of all the records concerning the strength and feeding of the camp. The concerned prisoners [Domagała and the camp messengers] were responsible for the total [reporting regarding] the strength [i.e., population] of the camp.”99

ITS holds the original copies of these saved cards, which include, as seen in chapter 1, prisoner category, previous and current prisoner number and block assignment, date and place of birth, religion, occupation, and transfer or death date. In aggregate, scholars might carry out a statistical analysis of the prisoner population (nationality, occupation, age, fate) or changes in the camp’s administration and policies as evidenced by changes in these cards over time. More than that, scholars may discuss the development and operations of this fascinating prisoner-run tracing service, already functioning in the summer of 1945,100 and those first months of what became the IIO, initially run by Domagała himself as camp secretary, with former prisoner Walter Cieslik as his deputy.101

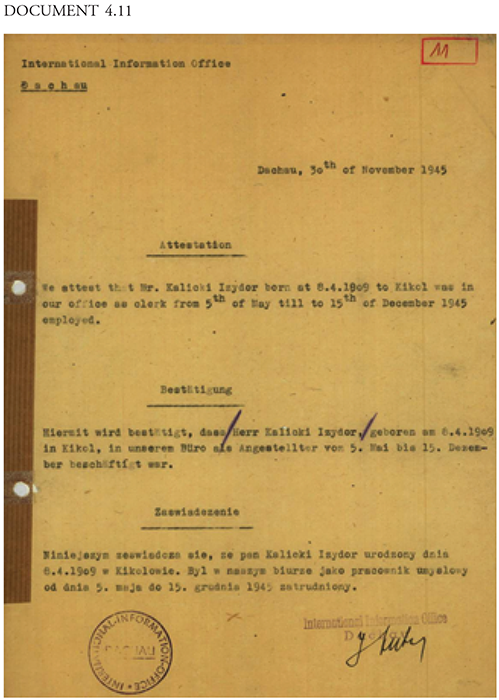

Established in June 1945 by order of the US military government in the city of Dachau102 and ultimately located on Schleissheimer Street,103 the IIO was “the only place which was able to care for evidence, information about [the] camp and [its] prisoners, and transports.”104 Specifically, this meant distributing “cards enabling survivors to receive double rations for eight weeks and disburs [ing] sums of money and items of clothing based on individual need to [. . .] local and traveling liberated inmates.”105 Given what we have seen concerning incredibly low numbers of staff engaged in tracing in those first fraught weeks and months,106 staffing of the IIO was rather astounding, “consisting of forty-two block writers, forty evidence writers and twenty-nine office writers.”107 The results were hundreds of documents like that dated November 30, 1945, in English, German, and Polish: “We attest that Mr. Kalicki Izydor born on 8.4.1909 in Kikól [a village in Poland] was in our office as clerk from 5th of May till 15th of December 1945.”108 (See document 4.11.109) Prisoners turned office clerks like Kalicki worked “day and night”110 and even created one of the first postwar exhibitions on the camp in its crematorium building in the fall of 1945.111

On November 20, 1945, the International Military Tribunal (IMT) opened in Nuremberg. Arguably the most famous and precedent-setting court of the twentieth century, the IMT consisted of the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. The IMT indicted twenty-four of the highest-ranking Third Reich leaders still alive and ultimately tried twenty-two select political leaders; eleven subsequent trials dealt with officers of the SS and Wehrmacht, policemen, judges, medical doctors, industrialists, and economists. The IMT charges against these defendants included crimes against peace, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and membership in criminal organizations.112 ITS holds partial copies of the so-called Nuremberg successor trials, which frequently reference the precedent set by the IMT. For example, ITS holds a copy of the opinion written by Robert M. Toms, presiding judge of Military Tribunal II (U.S. v. Oswald Pohl et al.), titled “Treatment of the Jews.” “This disgraceful chapter in the history of Germany has been vividly portrayed in the judgment of the International Military Tribunal,” stated Judge Toms and his colleagues. “Nothing can be added to that comprehensive finding of facts, in which this Tribunal completely concurs. From it we see the unholy spectacle of six million humans being deliberately exterminated by a civilized state whose only indictment was that its victims had been born in the wrong part of the world[,] to forbearers whom the murderers detested. Never before in history has man’s inhumanity to man reached such depths.”113

The year 1945 closed quietly, with the victims of the Nazi and Axis regimes slowly recovering their physical health and struggling to take faltering steps forward, with the Allies and the many agencies invested in aiding these steps struggling to keep up with the volume of their needs, and with the perpetrators of these criminal systems facing legal proceedings. The dramatic winter, spring, and summer settled into a fall characterized by the routine but difficult work that would face the Allies and their helpers for years to come. Scholars have not yet studied at the day-to-day operational level the dedicated men and women who carried out this work against enormous odds. The monthly report for the Child Welfare Division, Eastern Military District, gives eight lines about the work of Louise Pinsky in notes on December 7, 1945. Pinsky, regional child welfare officer for Regensburg, “continues to give conscientious service,” the report states. “She has now transported her 200th unaccompanied child to Indersdorf.” As 1945 came to a close, Pinsky worried, reporting that team regional child welfare officers like herself suffered from a “lack of time [. . .] to devote to [their] important work” and that, consequently, “many [officers were thus] delegating this responsibility to DP interviewers.”115

ITS-held documents allow us to look through the lens of 1945 and see far beyond studies of the so-called Hour Zero up to this point. In early 1945, many Germans in the privileged position of not yet counting themselves among the regime’s ever-increasing pool of victims did not understand or internalize that the war was lost, and with it, Nazism’s false ideals. Hans Fuge could still report with relish on his “lazy” camp inmates—Polish girls not yet sixteen—and Ruth Kleinsteuber could still volunteer for SS guard duty, as it seemed more promising than working for a ninth year as an embroiderer. Jews still alive in January 1945 could look forward to little sympathy or understanding as to the unique set of “choiceless choices” they faced and to even more unimaginable abuse at the hands of Nazis and their collaborators on the increasingly documented death marches. Civilians and captured military from all over Europe, including the United States, experienced the last months of the war as the most brutal.

Liberation, thus, was an unbelievable moment for the persecuted and incarcerated. “I was astonished, but a few hours later I had to accept it,” Christian Guy told Captain Alfred T. Bogen. Then came the shock—for the Allies, their helpers, and the world—of what they had managed to ignore or at least to view from a great distance until then: terrain formerly controlled by Germany, now littered with camps, mass graves, and murdered bodies. Everyone was disoriented, as captured in one British medic’s comment that patients at Sandbostel, “in spite of their weak condition[,] would step out of bed and wander about in the nude.” Death and disease still raged, and the Allies and charitable bodies of all sizes, denominations, and nationalities rushed to the scene. The work was desperate, and the need for some kind of centralized agency to trace missing persons and return the captured, kidnapped, and persecuted to their former homes (or new ones) became obvious almost immediately. Despite so many pressing concerns and human limitations, a Central Tracing Service was established. The many brave men and women, including former prisoners, who took up this work have yet to be studied and will be well worth attention in the future. The Allies and many victims of Nazism and its collaborators did not seek retribution in the end; rather, they hoped for justice. The IMT was a legal proceeding that forever changed the way the world would view the newborn concept of genocide.

For students and scholars, ITS-held documentation offers the opportunity to study the end phase of genocide and the beginning phase of recovery from the vantage point of every kind of actor, from perpetrator to witness to victim to rescuer. Any one aspect of that first year touched upon in this chapter merits broader and more systematic study of ITS-held documentation relating to everyone from German perpetrators, collaborators, beneficiaries, and witnesses, to victims struggling to hang on for just one more day, to the Allied soldiers and aid workers who came upon them and had to rebuild a broken nation, society, and infrastructure. The role of religious and secular aid organizations, including their motivations and the impact of gender within these organizations on the roles they took on, remains an understudied topic. Further, because ITS-held documentation spans the years of the Third Reich until today, any of these questions may be studied not only for 1945 but across decades.

DOCUMENT 4.1. Photograph of Abraham Langer contained in his CM/1 file, 3.2.1.1/79385447/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.2. “Extract from Report on Death Marches re: Kittlitztreben-Buchenwald,” 5.3.3/84619503/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.3. Hand-drawn map of the death march from Kittlitztreben to Buchenwald, 5.3.3/84619504/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.4. Cover sheet, “Belsen,” supplement to the British Zone Review, October 13, 1945, 1.1.3.0/82350807/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.5. World YMCA-YWCA organizational chart, US Zone, 1946, 6.1.2/82491687/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.6. Note by Margaret J. Newton, child welfare specialist, for Olive Biggar, relief services officer, UNRRA District Office No. 2, Wiesbaden, to G. K. Richman, assistant director, Relief Services Office, UNRRA, Pasing/Munich, July 19, 1946, 6.1.2/82491725/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.7. Letter from R. Oungre, 48 Boulevard Maillot, Neuillysur-Seine, France, to Colonel A. H. Moffitt, CDPX, c/o G-5 Division, USFET, August 25, 1945, 6.1.1/82496332/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.8. Extract from CORC/P (45) 54: Allied Control Authority Coordinating Committee for establishment of a Missing Persons Tracing Service, September 13, 1945, 1, 6.1.1/82500220/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.9. “Memorandum by US 3rd Army Military Government Regiment Regarding Displaced Persons and Foreign Workers Living Outside Camps,” October 5, 1945, 2.2.0.1/82392576/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.10. Extract from the report on the search in Belsen for the [Allied] Control Commission for Germany, Search Bureau Department, Belsen, June 10, 1946, 1.1.3.0/82350833/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

DOCUMENT 4.11. Attestation for Izydor Kalicki, International Information Office, Dachau, November 30, 1945, 1.1.6.0/82097119/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM (in English, German, and Polish).

1. For a brief description of the Dzierzązna subcamp, see Joseph Robert White, “Polish Youth Custody Camp of the Security Police Litzmannstadt,” in The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, Vol. 1: Early Camps, Youth Camps, and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA), ed. Geoffrey P. Megargee (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press in association with USHMM, 2009), 1528.

2. Martin Weinmann, Das Nationalsozialistische Lagersystem (Frankfurt am Main: Zweitausendeins, 1990), 322.

3. Bericht über die Bewirtschaftung des Hofes Dzierzązna (Arbeitsbetrieb des Polenjugendverwahrlagers der Sicherheitspolizei in Litzmannstadt), 1.1.22.0/82115751–6/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. This report is a copy received by ITS in 1984 from Michael Hepp of the Verein zur Erforschung der nationalsozialistischen Gesundheits- und Sozialpolitik e.V. in Hamburg. Hepp is author of “Denn ihrer ward die Hölle. Kinder und Jugendliche im Jugendverwahrlager Litzmannstadt,” in Mitteilungen der Dokumentationsstelle zur NS-Sozialpolitik 11/12 (April 1986): 49–71.

4. Bericht über die Bewirtschaftung des Hofes Dzierzązna (Arbeitsbetrieb des Polenjugendverwahrlagers der Sicherheitspolizei in Litzmannstadt), 1.1.22.0/82115751/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

5. After the German defeat during the Battle of the Bulge (the German offensive campaign launched through the Ardennes region of Wallonia in Belgium, France, and Luxembourg from December 16, 1944, to January 25, 1945), the western Allied troops rapidly approached the German border from the west, while Soviet troops advanced from the east.

6. As of January 1, 1945, he reported thirty inmates in the Dzierz.ązna subcamp, down from 150 at some point in 1944. See Bericht über die Bewirtschaftung des Hofes Dzierzązna, 1.1.22.0/82115753 and 82115755/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

7. Extensive literature on the ways in which 1945 represented continuities and discontinuities in German political, economic, and cultural practices exists: Bernt Engelmann, Wir haben ja den Kopf noch fest auf dem Hals: Die Deutschen zwischen Stunde Null und Wirtschaftswunder: 1945–1948 (Göttingen: Steidl, 1997); Geoffrey Giles, ed., Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago (Washington, DC: German Historical Institute, 1997); Nina Grontzki, Gerd Niewerth, and Rolf Potthoff, Die Stunde Null im Ruhrgebiet. Kriegsende und Wiederaufbau: Erinnerungen (Essen: Klartext, 2005); Shane Brian Stufflet, “No ‘Stunde Null’: German Attitudes toward the Mentally Handicapped and Their Impact on the Postwar Trials of T4 Perpetrators” (PhD diss., 2006), inter alia.

8. Daniel Blatman, The Death Marches: The Final Phase of Nazi Genocide (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2011), 1.

9. Peter Hayes writes, “The grisly story of Zyklon B as a murder instrument is traced from its testing in barracks basements of the main camp in August-September 1941, through its application first in the crematorium there until December 1942, then in two converted farm houses at Birkenau (Bunkers I–II) from early 1942 to the spring of 1943, and finally in four specially built brick crematoria (II–V), which until the gassing stopped in early November 1944 consumed more than half the people who ever died at Auschwitz.” Peter Hayes, “Auschwitz, Capital of the Holocaust,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 17, no. 2 (2003): 337–38.

10. Report on German concentration camps, January 3, 1945, 1.1.0.6/82328950– 55/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. This document is original and was received by ITS in 1956 from an unidentified source.

11. Ibid, 82328951.

12. In the context of Auschwitz II–Birkenau, Sonderkommandos consisted of Jewish prisoners who worked around the gas chambers and crematoria. Their duties included removing the murdered from the gas chambers, retrieving valuables from the dead, and burning the dead in the crematoria or open pits. For an accurate rendering, see, among other rare and important memoirs, Jadwiga Bezwinska and Danuta Czech, Amidst a Nightmare of Crime: Manuscripts of Members of Sonderkommando, trans. Krystyna Michalik (Oświęcim: Auschwitz State Museum, 1973), and Filip Müller, Eyewitness Auschwitz: Three Years in the Gas Chambers, trans. and ed. Susanne Flatauer (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1979).

13. Report on German concentration camps, January 3, 1945, 1.1.0.6/82328955/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

14. SHAEF is the term for the headquarters of the commander of the Allied forces in northwestern Europe from late 1943 until the end of World War II. US General Dwight D. Eisenhower commanded SHAEF throughout its existence. SHAEF’s “wartime mission ended on V-E Day. The last residual mission, the redisposition into the zones, was completed on July 10, 1945, and the Supreme Command terminated on the 14th.” Earl F. Ziemke, The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany, 1944–1946 (Washington, DC: US Army Center for Military History, 1990), 317.

15. Report on German concentration camps, January 3, 1945, 1.1.0.6/82328951/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

16. Erklärung unter Eid (affidavit), Gertrud Leppin (geb. Grünberger), 1.1.0.6/82326797–8/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. Staff working in the Interrogation Branch, Evidence Division, Office of the Chief of Counsel for War Crimes (OCCWC), Office of Military Government–United States interviewed Gertrud Leppin on February 5, 1947, in Berlin, where she was living at that time. ITS staff received this document, a copy, in 1956. The original document is part of approximately fifteen thousand pretrial interrogation transcripts compiled by the OCCWC and used in the prosecution of 185 defendants in the so-called Nuremberg successor trials, twelve separate proceedings held before US military tribunals I–VI from 1946 to 1949 in Nuremberg. For the formation of the OCCWC and a broader background of US efforts to try Nazi criminals, see Donald Bloxham, Genocide on Trial: War Crimes and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 28–29. Specifically, Leppin’s affidavit was part of case number 3, the “Justice Case” (United States of America v. Josef Altstoetter et al., 1947). One of the sixteen defendants indicted was Herbert Klemm, undersecretary (Staatssekretär) in the Reich Ministry of Justice, who was responsible for Sonnenburg penitentiary in 1945. See the so-called Green series in Trials of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10, Vol. 3: Nuremberg: October 1946–April 1949 (Buffalo, NY: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1997), 1099.

17. The Nazis dissolved the Sonnenburg concentration camp in the spring of 1934, converting it to a penitentiary under the Reich Ministry of Justice. Kaspar Nürnberg, “Sonnenburg,” in Megargee, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1:163–65.

18. Erklärung unter Eid (affidavit), Gertrud Leppin (geb. Grünberger), 1.1.0.6/82326797–8/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

19. Ibid.

20. Night-and-Fog (Nacht und Nebel) prisoners were the remnant of those not immediately killed as a result of the Wehrmacht Night-and-Fog Decree. The decree, issued by General Wilhelm Keitel in December 1941, allowed the Gestapo and the SD to arrest “all those found guilty of ‘undermining the effectiveness of the German Armed Forces’ in occupied western territories.” Intending to “deter anti-Nazi resistance in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway,” German military courts “imposed death sentences or deportation to concentration camps” on resisters. See Geoffrey P. Megargee, Inside Hitler’s High Command (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2000).

21. André Hohengarten, Das Massaker im Zuchthaus Sonnenburg vom 30/31 Januar 1945 (Luxemburg: Verlag der St. Paulus Druckerei, 1979).

22. Deposition of Ruth Kleinsteuber, 5.1/82300809/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

23. See Wendy Lower, Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013); Elizabeth Anthony, “Representations of Sexual Violence in ITS Documentation: Concentration Camp Brothels” in Freilegungen: Spiegelungen der NS-Verfolgung und ihrer Konsequenzen, Jahrbuch des International Tracing Service, Bd. 4, ed. Rebecca Boehling, Susanne Urban, Elizabeth Anthony, and Suzanne Brown-Fleming (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2015), 49–60.

24. These were labor and disciplinary work camps.

25. For more about this camp, see, among other works, Fritz Bringmann, Arbeitserziehungs-lager Nordmark: Berichte, Erlebnisse, Dokumente (Kiel: VVN-Bund der Antifaschisten, 1982); Detlev Korte, “Vorstufe zum KZ: Das Arbeitserziehungslager Nordmark in Kiel, 1944–1945,” in Die vergessenen Lager, ed. Barbara Distel and Wolfgang Benz (Munich: DTV, 1994).

26. Kleinsteuber testifies, and other sources confirm, that in April 1945, transports from other camps, especially from the Fuhlsbüttel penal complex, increased the prisoner population to five hundred (in her estimation). These new prisoners were Russian, Polish, French, Dutch, and German, and food supplies became insufficient. See deposition of Ruth Klein-steuber, 5.1/82300809/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. These new prisoners also came from Mölln and Neustadt in Holstein, both subcamps of Neuengamme. See Christine Schmidt van der Zanden, “Mölln” and “Neustadt in Holstein,” in Megargee, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1:1164–65.

27. Deposition of Ruth Kleinsteuber, 5.1/82300809/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. This deposition was taken on August 1, 1947, by Sergeant G. Goddard, Field Investigation Section, War Crimes Group, British Army of the Rhine. ITS contains a set of copies of documents related to Arbeitserziehungslager Kiel (5.1, folder 0021) sent to Bad Arolsen in the decades after the British Military Tribunal Kiel Hasse Case, which took place in Hamburg from October 29 to December 9, 1947. Kleinsteuber was acquitted. Very little secondary source literature exists on this trial.

28. About 160 kilometers (100 miles) southeast of Berlin, Stalag Luft III, a POW camp for captured air force servicemen run by the German Luftwaffe, is well known for two prisoner escapes. See Arthur A. Durand, Stalag Luft III: The Secret History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988).

29. Transcription, sworn statement of 2nd Lt. John C. Brown, 1.1.5.0/82065162/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. Eleven thousand POWs were marched out of Stalag Luft III before midnight on January 27, 1945, due to the proximity of Soviet troops. Temperatures were below freezing, and six inches of snow lay on the ground. The march was a total of eighty kilometers (fifty miles), with a stop in Bad Muskau. See Durand, Stalag Luft III, 332–33.

30. Durand explains that at Spremberg, the prisoners were divided; Americans from Stalag Luft III’s West Compound “went to Stalag XIII D outside Nuremberg.” Durand, Stalag Luft III, 335.

31. Transcription, sworn statement of 2nd Lt. John C. Brown, 1.1.5.0/82065162/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

32. Photograph of Abraham Langer contained in his CM/1 file, 3.2.1.1/79385447/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

33. A keyword search using the term ‘Kretschamberg’ in ITS across all archival units allows us to identify other Jewish prisoners also on this death march from Kretschamberg to Buchenwald. See the “Attributes” tab for Michael Potasch, 0.1/50585686; Leon Nass, 0.1/51393554; Baruch Brechner, 0.1/51835833; Fiszel Rabinowicz, 0.1/51904969; and Leib Goldman, 0.1/52206493/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. Each has a T/D file as well, detailing efforts to obtain documentation for reparations/compensation.

34. Sworn statement of Abraham Langer, Buchenwald, June 17, 1945, 1.1.5.0/82065532/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. This document is a copy of a set of sworn statements by former Buchenwald prisoners taken in June 1945 by the Judge Advocate Section, War Crimes Branch, US Third Army. ITS acquired copies in 1956. Ultimately, the statements were utilized for the US Army trial United States of America v. Josias Prince of Waldeck et al. (Case 000–50–9), the so-called Buchenwald Trial, which took place in Dachau from April to August 1947. In all, thirty-one defendants were indicted for war crimes related to the Buchenwald concentration camp and satellite camps, including Bad Arolsen’s own Prince Josias zu Waldeck und Pyrmont (1896–1967). Heinrich Himmler had appointed Waldeck the Höhere SS-und Polizeiführer (higher SS and police chief) of Weimar, giving him “supervisory authority over the concentration camp at Buchenwald.” General George Patton’s forces captured Waldeck at Buchenwald on April 13, 1945, a little over two months before Langer gave his testimony. In the trial, Waldeck was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. He was later amnestied under US High Commissioner John J. McCloy and released on November 29, 1950. He lived out the remainder of his life a wealthy man and died in his castle, Schloss Schaumburg (Diez an der Lahn), at the age of seventy-one. See Jonathan Petropoulos, “Prince zu Waldeck und Pyrmont: A Career in the SS and Its Murderous Consequences,” in Lessons and Legacies, Volume IX: Memory, History, and Responsibility: Reassessments of the Holocaust, Implications for the Future, ed. Jonathan Petropoulos, Lynn Rapaport, and John K. Roth (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2010), 169–84. Records relating to the Buchenwald and other US Army trials are available at the US National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

35. He must have been among those two hundred prisoners transported from Görlitz to the camp in March 1944. See Danuta Sawicka, “Kittlitztreben,” in Megargee, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 753.

36. Sawicka, “Kittlitztreben,” 754.

37. Fragebogenberichte zur Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa (Gemeindeschicksalsberichte) VI. Schlesien, 1.2.7.11/82191577/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. These materials are copies from the German Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv) acquired by ITS in 1972.

38. “Kittlitztreben-Buchenwald,” 5.3.3/84619503/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM; hand-drawn map of the death march from Kittlitztreben to Buchenwald, 5.3.3/84619504/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

39. The Commissariat Belge au Rapatriement created a map of this death march that is part of ITS holdings in Bad Arolsen. It gives a start date of January 21, 1945, for this death march. See Evacuation de Kittlitztreben à Buchenwald, Signatur (Reference Code) KP 12, ITS, Bad Arolsen.

40. Frustratingly, the questionnaires that the Allies sent to mayors across territories that had seen death marches (see “Investigations of the Allies,” 5.3.1) do not include any reports or witness testimonies from these locations. For a clear and thorough explanation of why this was so, see Daniel Blatman, “On the Traces of the Death Marches: The Historiographical Challenge,” in Freilegungen: Auf den Spuren der Todesmärsche, ed. Jean-Luc Blondel, Susanne Urban, and Sebastian Schönemann. Jahrbuch des International Tracing Service I (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2012), 85–107.

41. “Kittlitztreben-Buchenwald,” 5.3.3/84619503/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

42. Otto Weingärtner does not have the luxury of remaining anonymous in ITS. He can be found in a document ITS received in copy form from the Zentrales Staatsarchiv in Ludwigsburg. See p. 5 in the report “Übersicht über Verfahren wegen NS-Gewaltverbrechen: Stand vom 1.12.1961,” 5.1/82301475/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

43. Sworn statement of Abraham Langer, Buchenwald, June 17, 1945, 1.1.5.0/82065532/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

44. For more on Nordhausen, see Michael J. Neufeld, “Mittelbau (Dora) Main Camp,” in Megargee, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1:965–72.

45. Testimony of Christian Guy, civilian, Malines, Belgium, interviewed by Captain Alfred T. Bogen, Jr., assistant army inspector general, First US Army, 51st Field Hospital, Nordhausen, April 14, 1945, 1.1.27.0/82121869/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. These testimonies are copies from the State Archive (Staatsarchiv) of Nuremberg made in 1978. See 1.1.27.0/82121642/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

46. Ibid., 82121870.

47. Sandbostel (Stalag X-B) was a POW and prisoner reception camp in Lower Saxony. However, Sandbostel was flooded with thousands of concentration camp prisoners in April 1945, sent from the Neuengamme subcamps. At the time of liberation, sixty-eight hundred prisoners among the eight- to nine-thousand-strong prisoner population remained alive. See Marc Buggeln, “Neuengamme Subcamp System,” in Megargee, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1:1081.

48. Report on missing persons for Sandbostel Camp, Miss I. Hillers, BRCS, POW and DP Division, Control Commission for Germany, 55 Search Bureau, Göttingen, BAOR, July 18, 1946, 1.1.13.0/82111873–77/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. The report appears to be an original acquired by the ITS in 1956. Only the first eight pages of the report are in ITS.

49. Ibid., 82111874.

50. Ibid., 82111875.

51. Ibid.

52. “Belsen,” supplement to the British Zone Review, October 13, 1945, 1.1.3.0/82350807/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

53. For a summary of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, see Thomas Rahe, “Bergen-Belsen Main Camp,” in Megargee, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1:278–81.

54. “Belsen,” supplement to the British Zone Review, October 13, 1945, 1.1.3.0/82350807–10/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

55. Ibid., 82350807.

56. Ibid.

57. Ibid., 82350807-8.

58. Postliberation hospital records, consisting mainly but not exclusively of lists of prisoners and biographical detail about them, abound in ITS. For example, see 2.1.3.2 (Hospital Files, French Zone), 2.1.4.3 (Lists of Inpatients of Hospitals in the Soviet Zone), 2.1.4.4 (Hospital Files, Soviet Zone), 2.1.5.2 (Lists of Inpatients of Hospitals in Berlin), 2.1.5.3 (Hospital Files, Berlin), 2.3.3.2 (Card file of Persecutees Treated in Hospitals on the Territory of the Later French Zone), 10.7.41 (American Hospitals Files/Prisons), and many other subunits in which the treatment and convalescence of child and adult victims can be found interspersed with other kinds of material.

59. The Church World Service was founded in 1946. Seventeen Catholic and Protestant denominations came together to form an agency to “feed the hungry, clothe the naked, heal the sick, comfort the aged, shelter the homeless.” See “History,” Church World Service, www.cwsglobal.org/about-us/history.html (accessed July 7, 2015).

60. Headquartered in Geneva, the YMCA-YWCA was founded in 1844 with the mission “to bring social justice and peace to young people and their communities, regardless of religion, race, gender or culture.” See “Who We Are,” World YMCA, www.ymca.int/who-we-are (accessed June 17, 2014).

61. World YMCA-YWCA Organizational Chart, US Zone 1946, 6.1.2/82491687/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

62. The UUSC was founded in 1945 to support relief work in Europe. The USHMM holds archival records for the UUSC that would complement well the study of ITS documents pertaining to the UUSC. See RG 67.012 and 67.028, USHMM.

63. Statement by Ernst Papanek, director of child projects, Unitarian Service Committee, New York, 1945, 6.1.2/82491726/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

64. Margaret J. Newton, child welfare specialist, for Olive Biggar, relief services officer, UNRRA District Office No. 2, Wiesbaden, to G. K. Richman, assistant director, Relief Services Office, UNRRA, Pasing/Munich, July 19, 1946, 6.1.2/82491725/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

65. At that time, the term referred to the Allied powers that had fought against the Nazis and Axis powers in World War II.

66. Margaret J. Newton, child welfare specialist, for Olive Biggar, relief services officer, UNRRA District Office No. 2, Wiesbaden, to G. K. Richman, assistant director, Relief Services Office, UNRRA, Pasing/Munich, July 19, 1946, 6.1.2/82491725/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

67. Letter from Vernon Kennedy, director, American Zone Austria, Salzburg, to E. Rhatigan, UNRRA, Frankfurt, August 16, 1945, 6.1.1/82502593–4/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

68. See, among others, Beth B. Cohen, Case Closed: Holocaust Survivors in Postwar America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007).

69. See also Johannes-Dieter Steinert, “Germanisierung, Kollaboration und militärische Aktionen,” in Deportation und Zwangsarbeit: Polnische und Sowjetische Kinder im Nationalsozialistischen Deutschland und im besetzten Osteuropa, 1939–1945 (Essen: Klartext, 2013), 97– 108; Roman Hrabar, “Lebensborn”: Czyli, źródło ၼycia (Katowice: Wydawn. “Śląsk,” 1980), and other works by Hrabar on the kidnapping of Polish children.

70. Her real name was Henryka Gozdowiak; she was born on either December 12 or November 16, 1934. See 6.3.2.1/84247777/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

71. Copy, affidavit of Therese Grassler, Document Book X for Max Sollmann in the proceedings against Ulrich Greifelt and others submitted to Military Court I by Dr. Paul Ratz, Nuremberg. Dr. Ernst Braune, assistant defense counsel, American Military Tribunal Case 8, took this affidavit in Grassler’s home on Ganzhofstrasse 19 in Salzburg-Maxglan on December 26, 1947. See 4.1.0/82480770–73/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. This is one in a set of copies pertaining to Nuremberg Successor Trial Number 8, U.S. v. Ulrich Greifelt, the so-called Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt Case from October 10, 1947, to March 10, 1948. These documents are the original reproductions used in the case, given to ITS in 1956.

72. Affidavit of Therese Grassler, 4.1.0/82480771/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

73. Ibid., 82480772. Other evidence in ITS-held documents confirm that Henderike was deported to the Lebensborn facility Hochland in Steinhöring, near Munich, on April 16, 1943. See 6.3.2.1/84247777/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

74. Affidavit of Therese Grassler, 4.1.0/82480773/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

75. See ITS Child Search Case Goschen, Henderike, 6.3.2.1/84247776–81/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

76. For example, see, among others, Anne-Maria Lenhart, Eine Darstellung der Organisation “Lebensborn e.V.” (Hamburg: Diplomica, 2013); Per Meek and Arne Löhr, Lebensborn 6210 (Kristiansund: Ibs Forlag, 2001); Dorothee Schmitz-Köster, “Deutsche Mutter, bist du bereit—”: Alltag im Lebensborn (Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag, 1997); Dorothee Schmitz-Köster, Kind L 364: Eine Lebensborn-Familiengeschichte (Berlin: Rowohlt, 2007).

77. Uwe Ossenberg, The Document Holdings of the International Tracing Service (Bad Arolsen: ITS, 2009), 2–3.

78. “The Tracing of Missing Persons in Germany on an International Scale, with Particular Reference to the Problem of UNRRA: Study Prepared by UNRRA Administration,” June 1, 1946, 6.1.1/82492879/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

79. At the time of the transfer, “the UNRRA staff [of the CDPX Central Tracing Bureau] had increased to only five.” “The Tracing of Missing Persons in Germany on an International Scale, with Particular Reference to the Problem of UNRRA: Study Prepared by UNRRA Administration,” June 1, 1946, 6.1.1/82492879/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

80. Separate and distinct from SHAEF, USFET commanded only US troops. Under Eisenhower as theater commander, when it opened in Frankfurt on July 1, and “when its increments from European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army (ETOUSA), SHAEF, and the 12th Army Group were fully assembled,” it consisted of 3,885 officers and 10,968 enlisted men. Its sphere of responsibility, notes Earl F. Ziemke, extended to US troops in “England, France, Belgium, Norway, and Austria.” Two military government staffs governed the US Zone of Occupation: the US Group Control Council and the theater G-5 (Civil Affairs– Military Government Section). See Ziemke, The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany, 317, 458.

81. Established on August 30, 1945, the Allied Control Council (Allied Control Authority) was the military occupation governing body of the Allied occupation zones in Germany. The members were the Soviet Union, United States, and United Kingdom; France was later added with a vote but had no duties.

82. Ossenberg, The Document Holdings of the International Tracing Service, 3–4.

83. In July 1945, UNRRA had “2,656 persons in 332 DP teams deployed throughout the western zones.” Ziemke, The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany, 318.

84. “The Tracing of Missing Persons in Germany on an International Scale, with Particular Reference to the Problem of UNRRA: Study Prepared by UNRRA Administration,” June 1, 1946, 6.1.1/82492879–80/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

85. Letter from R. Oungre, 48 Boulevard Maillot, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, to Colonel A. H. Moffitt, CDPX, c/o G-5 Division, USFET, August 25, 1945, 6.1.1/82496332/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. This document is original to ITS.

86. Ibid.

87. Cable on postal service for displaced persons from Colonel L. W. Charley, deputy chief programs officer, DP German Planning Branch, to Mr. E. E. Rhatigan, UNRRA/CDPX, c/o G-5, USFET, Frankfurt, August 20, 1945, 6.1.1/82496301/ITS Digital Collection, USHMM. This document is original to ITS.

88. CORC/P (45) 54: Allied Control Authority Coordinating Committee for establishment of a Missing Persons Tracing Service, September 13, 1945, 6.1.1/82500219–22/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

89. Ibid., 82500220.

90. Ibid.

91. “The Tracing of Missing Persons in Germany on an International Scale, with Particular Reference to the Problem of UNRRA: Study Prepared by UNRRA Administration,” June 1, 1946, 6.1.1/82492880/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

92. Ossenberg, The Document Holdings of the International Tracing Service, 6.

93. Ibid. Chapter 2 discusses the scholarly value of such lists.

94. “Displaced Persons and Foreign Workers Living Outside Camps,” October 5, 1945, 2.2.0.1/82392576/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

95. Report on the search in Belsen for the [Allied] Control Commission for Germany, Search Bureau Department, Belsen, June 10, 1946, 1.1.3.0/82350833/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

96. Ibid. The author is Lieutenant H. François Ponet, the French search officer.

97. For broad analysis of the history of the Dachau site postwar, see Harold Marcuse, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933–2001 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

98. For the history of the Dachau Schreibstube, see “History of the International Information Office Dachau,” 1.1.6.0/82089047–59/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. The report is undated, and its author is not identified. This document is original.

99. “History of the International Information Office Dachau,” 1.1.6.0/82089047–59/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. See also Jan Domagała, Ci, którzy przeszli przez Dachau (Warsaw: Pax, 1957).

100. For an account of how these documents came to rest with the Central Tracing Bureau, see 6.1.1/82510716/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. The accession notes for 1.1.6.7 (Office Cards Dachau) only make note of copies of a limited number of cards received from the Dachau memorial.

101. Marcuse (Legacies of Dachau, 66) is erroneous in calling Cieslik the first “head” of the IIO. In fact, Domagała was its first head, from June until September 1945, when he returned to Poland. He was succeeded by the head of the IIO press office, Mr. Husareck, who retired in May 1946. Only then did Cieslik assume this role. See “History of the International Information Office Dachau,” 1.1.6.0/82089049/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

102. Ibid. According to the report on the IIO, “General Adams” confirmed the transformation of the Schreibstube into the IIO, as did the commanding officer stationed at Dachau at the time, Colonel Bill Joyce. IIO staff reported directly to the US Army camp officer, Lieutenant Rosenbloom, who was succeeded by Captain Schmitt and finally Captain Deal.

103. Ibid. Marcuse (Legacies of Dachau, 66) correctly notes the location of the IIO when it officially became known as such. An added detail from the ITS report is that during the operation of the camp, and at the time the records were preserved, the Lagerschreibstube was in “hut one” of the camp. After liberation, the nascent IIO was placed in the former Dachau commandant’s building and only then moved to Schleissheimer Street.

104. Ibid., 82089048.

105. Marcuse, Legacies of Dachau, 66.

106. As the report on the IIO put it, “At that time [June 1945] nobody cared, and there was no time for [tracing efforts].” “History of the International Information Office Dachau,” 1.1.6.0/82089049/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

107. Ibid., 82089048.

108. Ibid.

109. Attestation for Izydor Kalicki, International Information Office, Dachau, November 30, 1945, 1.1.6.0/82097119/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

110. “History of the International Information Office Dachau,” 1.1.6.0/82089048/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

111. See Marcuse, Legacies of Dachau, 170.

112. The literature on the IMT and its impact on legal practice is vast. Among the best sources are Lawrence Douglas, The Memory of Judgment: Making Law and History in the Trials of the Holocaust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), and Bloxham, Genocide on Trial, among many other excellent works by both authors.

113. See “Excerpt from the Opinion and Judgment of United States Military Tribunals Sitting in the Palace of Justice, Nuremberg, Germany, at a Session of Military Tribunal II, Held 3 November 1947,” 1.1.2.0/82349440–41/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. This document is a copy received by ITS in 1978 from the Staatsarchiv Nürnberg.

114. Memorandum from Louise Pinsky to Eileen Davidson, Regensburg, October 18, 1945, 6.1.2/82487052/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

115. Child Welfare Division monthly report, Eastern Military District, December 7, 1945, 6.1.2/82487236/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. For documents confirming Pinsky’s role, see 6.1.2/82486994 and 82487011. For a report she wrote on differences she observed between Jewish and non-Jewish children under her care, see letter from Pinsky to Eileen Davidson, Regensburg, October 18, 1945, 6.1.2/82487052/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM. On Indersdorf, see chapter 3. For more on the activities of the Eastern Military District, see “Child Welfare Report on Activities in Eastern Military District,” November 28 to December 9, 1945, 6.1.2/82486985–89/ITS Digital Archive, USHMM.

*Original with hole punches and cut off at the bottom.