AMERICANS ARE THE PEOPLE WHO, when the French decided that Jerry Lewis was a genius, never stopped to ask why but immediately branded France a nation of idiots. (That may well be, but not because they like Jerry Lewis.) It’s safe to say that almost all of American comedy except Chaplin and Keaton is undervalued due to our depressing national tendency to award our prizes and honors to anything perceived as “serious.” Lip service is paid to our great tradition of “slapstick,” but no one actually knows much about who did it and what it really was. Although a Mack Sennett chase has become a symbol of silent film comedy, the true brilliance of the work is not generally appreciated and not enough credit is given to two glories of the old Sennett gang, the beautiful and intrepid comedienne Mabel Normand, and those truly amazing Keystone Kops … Mabel and the Kops.

The Kops! Ah, the Kops. On the road and out of control. See how they run, or, more to the point, see how they drive, steering firmly but dangerously over curbstones, around trolley cars, through plate glass windows, and on top of a row of terrified ditchdiggers who drop their shovels and duck. Ignoring not only all traffic laws but the laws of gravity and sanity as well, the Kops are out there doing what we all secretly long to do: not giving a good god-damn as they relentlessly pursue their goal. Oh, those Kops. How rewarding it is to watch them. How little they care about their fellowman, and—oh, boy—what a good time they’re having at very, very high speeds.

And Mabel. The whoop-de-doo girl, a tiny creature who could ride a horse, drive a car, fall on her butt, clamber over a rooftop, and still look like a million bucks when she was through. Mabel was the babe who got tied to the railroad tracks while the villain twirled his mustache—but only in jest. She was a figure of delicious liberation who made a joke out of the idea of a damsel in distress. When Mabel showed up, it was everyone else who was potentially in distress, because nothing stopped her, nothing slowed her down.

No discussion of Mabel and the Kops can begin without first considering the King of Comedy, the man whose work first presented us with the three noblest inventions of movie comedy—the pie, the banana peel, and the car: Mack Sennett, who once proclaimed his philosophy of comedy as “slap ’em down good.” Under Sennett’s guidance, Mabel and the Kops achieved phenomenal popularity, as did many more of Sennett’s comedy stars, including at one time or another Charlie Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, Chester Conklin, Mack Swain, Marie Prevost, Marie Dressler, and Gloria Swanson.

Sennett is certainly acknowledged to be the great pioneer of silent film comedy, but not always recognized is the startling quality of his fantastical movies, the bizarre and surrealistic nature of his world. The critics of his own time had a keen appreciation of his comedy that is much broader than the one generally held today. In a 1928 issue of Photoplay, the novelist Theodore Dreiser, who was also a film critic and fan, called Sennett “a master” and “Rabelaisian.” His movies are a world unto themselves—a world that’s always falling apart, collapsing out from under its hapless characters. No one has described it better than Dreiser, who, after praising “the pie throwers, soup spillers, bomb tossers,” went on to pay tribute to

bridges, fences, floors, sidewalks that give way under the most unbelievable and impossible circumstances. The shirt-collars, too tight during attempts to button them, which take flight like birds. The houses which spin before the wind, only to pause with a form of comic terror on the edge of a precipice, there to teeter and torture all of us. The trains or streetcars or automobiles that collide with one another and by sheer impact transfer whole groups of passengers to new routes and new directions. Are not these nonsensicalities illustrations of that age old formula that underlines humor—the inordinate inflation of fantasy to heights where reason can only laughingly accept the mingling of the normal with the abnormal?

Mack Sennett is one of the great artists of the early cinema, although art was never his goal. His high-speed comedies of people chasing each other exist in a kind of free-floating universe of action detached from anything natural. They contain characters with wonderful names like Marmaduke Bracegirdle and Mr. Whoosiz, and they have plots in which anything imaginable—and much that isn’t—can happen. They have endearing intertitles that comment on “a mother-in-law who never lost an argument”; or, about a character presumed deceased who suddenly starts breathing—“not so darn dead!” The world of Sennett is one in which machinery fails you or runs away with you, and characters are loose in a wild and unpredictable landscape populated with crooks and con artists. Everyone is busy getting hold of money in any way possible, yet policemen are everywhere, standing on every corner, under every tree. There is a clear line drawn between the rich and the poor, but jumping across that line can be accomplished through daring, danger, and driving very fast.

This doesn’t mean there are no rules. It’s axiomatic that if anyone is wearing polka-dot underwear, his pants are sooner or later going to fall down and reveal all. And if a cook is hired, she won’t know how to fire up the stove, and a chauffeur is probably a burglar in disguise. Furthermore, if one man chased by a bear is funny, two men chased by two bears is funnier. Twelve men chased by two bears, three goats, four policemen, two hyenas, and a giraffe is hysterical. The Sennett comedies are always physical. Since they were made at a time when Americans performed real labor (as opposed to today’s more cerebral daily work), this makes sense; the characters are all attempting to do things: cook, drive, build, repair, feed the animals. At the same time, these practical souls are being undermined by others, less practical, who hope to gain by doing nothing at all, so they scheme, plot, plan, foil, and seduce. The stories seem to develop spontaneously because, in fact, they were spontaneous, often improvised on the spot. The bottom line about all these movies is that they were—and are—universally understood.

Mack Sennett’s accomplishment was that he defined the American version of slapstick by making physical comedy cinematic. To the old forms of burlesque and carnival, he added the tricks only movies can provide, using editing, fast cranking, camera angles, and dissolves to create a fresh new approach to the genre. For instance, for the Kops Sennett developed a wonderful set of routines, including one in which a patrol wagon, like the Marx Brothers’ stateroom that would postdate it, unloaded an unbelievably endless supply of Kops, or the one in which a hapless Kop was dragged down the street behind a speeding auto. In the former, each Kop just disappeared out of camera range, at which point the camera was stopped so that he could return to the wagon and disembark again. In the latter, the cameraman operated at a speed that appeared to be much faster when it was shown on the screen, and the actor actually was riding a small platform mounted on wheels. Sennett also discovered that by editing out every third or fourth frame, a sequence seemed to move even faster when screened.

There may have been chases in films before Sennett, and, in fact, most people think the idea originally came from French cinema, Méliès or Pathé, but it is Sennett who lifted the chase into an art form and made it an American event. Obviously, the grand chase over a landscape as a finale to the theatrical process couldn’t have happened before the invention of film. And film without the encumbrance of sound meant that the chase could really cover ground, over hill and dale, in ways that staggered the imagination. If people think the chase as practiced by Sennett is not an art form, they have only to look at the highly capable chases in It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and The Pink Panther to realize how very much better Sennett’s were. It’s the precision timing, the careful orchestration of action, and the ever-escalating chaos that is remarkable. No one today seems able to do it at the same pace, with the same energy, and with the same wild abandon. Perhaps we’re all too conscious of the actual dangers involved for the actors, animals, automobiles, and various other objects involved. Today we can imagine the ASPCA standing by to make sure the horses clopping ahead of the fire wagon aren’t being mistreated, or the actress’s hairdresser demanding that the pace be adapted to her hairdo, or the actor himself insisting on either his double doing the work or that he be paid extra and protected in the close-ups. Back then, they just hopped in and drove. They were getting paid, and what the hell?

There are chases of all kinds in the Sennett films, involving men and women and animals and vehicles on the land, in the air, and on the water, with an assortment of impediments along the way: flying bricks and stones, detours that appear out of nowhere, mud holes deep enough to sink the Titanic, innocent street-crossers, chicken coops full of cluckers, houses, windowpanes, and, of course, the railroad tracks. If an automobile full of characters was barreling down the highway and had to cross a railroad track, the railroad ties, through some mysterious force known only to movie magic, would stall the car—and always just at the moment an express train was bearing down. But Sennett knew how to establish the joke—car on railroad track—use it well, and next time, vary it. The train switches to another track, or the people jump out of the car, or the train actually hits the car, or whatever. Sennett always came up with a new twist, a new madness. He understood the audience, knowing how to surprise them, repeat something for renewed laughter, and then switch to a newer, more sophisticated variation on the laugh. Sennett worked with his audience—and against them—with true genius.

And then there was the pie. Mack Sennett and the pie, an American love story. At some point in the history of the Sennett company, the first pie was thrown into the first face. Mabel Normand was reputed to have been the initial pie thrower and credit was given to her for inventing the idea. Certainly, A Noise from the Deep (1913) has Mabel tossing a pie into the round and startled face of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. There is something deeply poetic about the fact that the first movie pie was probably thrown by a woman, Mabel Normand, into the face of a surprised male actor. It’s a great feminist statement—the revolt of the pie maker. (The pie was a constant Sennett joke. In Tillie’s Punctured Romance, her rich uncle is described as “a pie manufacturer.”)

The Sennett pie was not a pie as we mortals know it. It was a concoction of paste that would hold together as it flew through the air, and there was an art to tossing it. It couldn’t be crudely heaved; it had to be pushed forward with balance, form, and a smooth follow-through. Expert opinion had it that six to eight feet was the ideal distance, and Fatty Arbuckle was hailed as an ambidextrous pie thrower who amazed everyone because he could launch from as far back as ten feet. The banana peel—the other key comic foodstuff—was manipulated to advantage by everyone connected to silent film comedy, not just by Sennett and his troupe, though he played his part by escalating the pratfalls generated by the slippery item.

Mack Sennett as an actor in Stolen Magic (photo credit 2.1)

Where did Sennett come from, that he understood comedy so perfectly and could adapt it to the new medium with such panache? Mack Sennett entered movies early, and as an actor. He was born Michael Sinnott in Canada, probably in 1880, to an Irish Catholic family who were not wealthy. He had a marvelous bass singing voice, and after working as a laborer, he resolved to go to New York City (in about 1902) and try to get into the Metropolitan Opera. Instead, he got a job at a burlesque theatre and soon gave up his singing ambitions and began playing comedy on the burlesque circuit. Most biographical entries on Sennett suggest that he entered films in 1909, but there are scholars who think that by that date he had already acted in approximately twenty-two movies for D. W. Griffith. There are records that indicate that he made twenty-three movies in 1908 (only seven of which are comedies). In 1909, he appeared in approximately fifty-eight dramas and thirty-five comedies, almost two a week. In 1910, there were twenty-five dramas and twenty-four comedies, and finally, in 1911, he began to direct. By August of that year, Mack Sennett was solidly established as a successful maker of comedies. What is important about these early years is that he was under hire to Biograph. Sennett once said, “I learned all I ever learned by standing around and watching people who knew how,” and one of the people he was watching definitely knew how—Biograph’s D. W. Griffith, who befriended him in his first years in the movie business.

Throughout 1911 and 1912, Sennett cranked out movies, among them two films that are considered possible forerunners to the concept of the Kops, When the Firebells Rang (the hapless professionals are firemen, not police) and The Would-Be Shriner, in which a parade of Shriners is constantly interrupted by policemen. In 1912, Sennett joined two film producers, Adam Kessel and Charles Bauman (owners of the New York Motion Picture Company), to form the Keystone Film Company, which gave him the freedom to do whatever he wanted to in production. Under contract was not only Sennett but Mabel Normand, among others. An ad was run in the trades: “KEYSTONE FILMS. A Quartet of popular fun makers. Mack Sennett, Mabel Normand, Fred Mace, Ford Sterling, supported by an all-star company in split-reel comedies. A Keystone every Monday.” From that point on, Sennett was a major creator of comedies, some of which starred Charlie Chaplin, who came to Keystone in late 1913 and remained for a year; he had been brought in as a potential replacement for a disaffected Ford Sterling. Although he made thirty-five comedies for Keystone, Chaplin was reputedly unhappy there, even though his Little Tramp character was perfected during this time. (Some historians feel that Chaplin never gave Sennett and Mabel enough credit for the Tramp’s development.) By the fall of 1914, Chaplin was becoming a real star and was advertised as one of Sennett’s trio of popular comics, along with Arbuckle and Mabel: an issue of Photoplay presented a comic “menu” that offered “Chaplin Supreme, Stuffed Arbuckle, and Normand, Scrambled.” Chaplin left Sennett largely because he had a star’s mentality and did not like taking orders from others. Furthermore, his personal style of comedy was grounded in a burlesque of real life, and Sennett’s was surrealistic.

Sennett went on making films for Keystone until 1917, when he took control of the company, changed its name to the Mack Sennett Comedies Corp., and began releasing his movies through Paramount. The actual “Keystone Comedies” were made between 1912 and 1917. Typical is Love, Speed, and Thrills (1915), a title that says it all, and it more than lives up to its name. Mack Swain and Chester Conklin play characters they portrayed in a number of Sennett’s works, Ambrose (Swain) and Walrus (Conklin). The film builds toward a magnificent chase, in which a man on a horse, three cops on foot, and a woman riding in the sidecar of a motorcycle driven by the villain (Walrus) tear across the countryside. Later in the action, the cops commandeer a rowboat, just in time to collect the villain as he falls off a huge bridge. The girl, also falling, has been lassoed and saved by the man on the horse (Ambrose, her husband). As the chase plays out, the horse gallops alongside the sidecar, and the heroine is swept up onto it, but when the horse and two riders collapse and turn over, the motorcycle speeds by, tipping the woman back into the sidecar. Everybody falls down. Everybody switches from foot to car and from car back to foot, and it’s fast, funny, inventive, and amazing. This is the essence of Mack Sennett’s silent comedy.

These movies are not always politically correct. Toplitsky and Company (1913) contains a blatant stereotype of a Jewish store owner within a farce that concerns the leading character’s attraction to his partner’s wife. The resulting mixup, in and out of bedrooms, is not viciously anti-Semitic, but it’s uncomfortable viewing today. The villainous store owner jumps out of the wife’s bedroom window and goes on the run, taking refuge by running into a bathhouse to hide. (Why a bathhouse?) During the escape, he runs past a large black bear tied up on a chain outside a suburban house. Hence, the surreal: why is a bear on a chain outside an ordinary home? Later the bear gets loose (“Trouble,” says the succinct title card) and, naturally, wanders into the bathhouse, chasing everyone out and down the street. The combination of black bear, husband, store owner, wife, and bathhouse … well, it’s crazy, isn’t it?

Another early Sennett comedy, One Night Stand (1915), is set on a stage in a little theatre. On the walls are written warnings such as ASBESTUS (sic), NO SMOKING, DO NOT TOUCH LINES, and DO NOT SEND YOUR LAUNDRY OUT TILL WE SEE YOUR ACT. Throughout the action, the characters are constantly smoking, touching things, and, we presume, sending their laundry out. Certainly they ignore the big one: WATCH YOUR STEP. Chaos reigns. All the stage flats fall down, and offstage characters poke sharp objects through them, sticking those trying to perform on stage, a kind of crude early Noises Off concept. The stagehands finally attack the actors, and everyone runs around, both offstage and on, bopping everyone else. Seen today, it’s a great visual metaphor: film comedy destroys Victorian theatre.

In the 1915 Love, Loot, and Crash (a perfect title), a banker and his daughter have no cook and cannot cope on their own. They run an ad in the paper, and two crooks read it, deciding that one of them will dress up as a woman and get the job so they can loot the place later. (“Put on your frills, and grab the job.”) Meanwhile, the girl loves a boy her father doesn’t approve of, and keeps jumping out the window to meet him, but Dad always stops her. Eventually the fake cook, the father and the girl, and the friendly neighborhood cop who drops in for coffee are all inside the house together. Outside are the boyfriend, arriving to elope with the girl, and the other crook, arriving to help burgle the joint. All three actions ingeniously entwine. The boyfriend drives up on a motorcycle, and the fake cook (still in drag) jumps out the window to escape the cop and gets on the motorcycle. He thinks it’s his cohort, and the boy thinks it’s the girl. Off they go! A stolen car arrives, driven by the cohort, and the girl jumps in, thinking it’s the boy. The cop has been trapped in the kitchen by the cook, but now he breaks out and takes off after them. He and his fellow cops commandeer a vehicle to chase the stolen car, and all three groups race off at top speed, with various disasters along the way, down to the seaside. Everyone falls in the water except the girlfriend, who watches from the boardwalk, and the movie ends.

A Muddy Romance (1913) is a madcap romp featuring the “water police,” who leap into a rowboat to stop a marriage ceremony that is taking place in another boat in the middle of a lake. They row wildly forward, firing their guns and falling into the water, until some distant force shuts off the water source, draining the lake and dumping all the participants into thick, viscous mud, in which they wallow helplessly.

The typical Sennett comedy is full of inventive action, and props and sets are equally inventive, such as a real swimming pool built on the set and, for Astray from the Steerage (1921), a chair that twirls (for which Sennett came up with an optical effect that showed the point of view of the character who was spinning). Titles are also an inventive part of Sennett’s comedy—“All your fault—as usual” and “Enjoying her jealousy in a woman’s way.” And some are slightly off-color, such as a tasteful introduction of today’s comedy favorite, the fart joke: “The cheese makes itself known,” with all the characters delicately holding their noses, not daring to look at each other. Mostly, however, the characters run around, fall down, and accuse each other in a series of bizarre events. In The Surf Girl, an ostrich swallows the heroine’s locket. Like the bear outside someone’s home in Toplitsky and Company, this ostrich is conveniently available.

Sennett not only incorporates unlikely animals and ordinary cars into his stories, he also makes use of any other conveyance he can put his hands on: boats, trains, wagons, bicycles, anything that moves. As new inventions appear, movies always incorporate them into the plot. Today we have computers. Heavily muscled heroes and heroines who’ve worked out in the gym all day to perfect those bodies sit down at a computer terminal, loom heavily over the machine, and brilliantly type in questions that will not only resolve the plot but will explain EVERYTHING. (And the actors never have trouble figuring out access codes.) In the days of the Sennett comedy, things were reversed. Little people, looking overwhelmed and confused, struggled with cook stoves that belched sooty smoke all over them. They burned the eggs. Their clothes were ruined. They couldn’t cope. Today, the questions are big but easily solved. Then, the questions were small but required heroic individual effort to figure out. We’ve progressed from brave little humans tackling small troubles and prevailing to big humans tackling imaginary woes (aliens and dinosaurs) and blowing them to kingdom come, the final resolution.

These early comedies set up a situation, vary it, milk it, take it to its moment of highest chaos, and then leave it unresolved. For instance, Toplitsky and Company ends when all the characters are fighting each other in the bedroom and the bed collapses. In Love, Loot, and Crash, the movie is over once everyone falls into the water. Critics often complain that American comedies set up hilarious premises but are unable to resolve the action in an equally funny way. It’s interesting to note, watching Sennett, that a sensible narrative resolution was never part of the American comic tradition. With Sennett, the explosion of utter chaos was the resolution, and there was no better way to achieve it than through the rapid chase. What the big number with 200 blonde tap dancers, 100 roller skaters, and 50 American flags is to the musical, what the final shoot-out in dusty streets is to the western, the chase is to the Sennett comedy. Down the road, over the bridge, under the viaduct, across the landscape, off the pier, and into the water is the final resolving action. Logic plays no part in the setup and thus has no role in the payoff.

Between 1913 and 1915, Sennett made comedies in which both Mabel Normand and the Keystone Kops emerged as audience favorites, and of the two, the Kops—at least in name—are the better known today. Kalton C. Lahue and Terry Brewer, in their book, Kops and Custards: The Legend of Keystone Films, state flatly, “The Keystone Kops were Sennett’s major contribution to Americana and to the American language.” They explain that the Kops were not born on-screen as a unit but rather emerged after a gradual evolution of an idea that Sennett nurtured for years. The book dates the first “recorded existence of a Kop picture from Keystone as the December 23, 1912, release of Hoffmeyer’s Legacy,” and adds, “From this point on, one or more policemen were in nearly every comedy.” Throughout 1913, new comics who signed on with Keystone were given a trial period in a Kop uniform, so that, Lahue and Brewer explain, it was “quite easy for Sennett to determine whether the man actually had what it took to be a true Keystone comedian … if he had the stamina to stand up under the sometimes brutal punishment and still come across as being funny.”

The Bangville Police (1913) is a perfect introduction to the Kops. The guys are a bunch of rubes in straw hats, clunky shoes and boots, and non-matching outfits. They ride to farm girl Mabel Normand’s rescue, she mistakenly believing that thieves are lurking about her homestead. As they rush forward, the Kops fall down in the dusty street, tripping over each other and their own feet, before they clamber aboard their lone automotive pursuit vehicle (ridiculously marked with the number 13, although the first twelve vehicles are nowhere to be seen). The chief summons this motley group by firing his pistol into the ceiling. Some come on foot, carrying shovels as their weapons, and others run straight to the scene of the “crime.” The fast-paced comedy mixes parallel story lines in which Mabel mistakes her own family for the bad guys, and the family mistakes her for those typical silent film villains, “Burglars!”, when she hides from them. The Kops arrive and add to the confusion, but everything is, as usual, wrapped up within minutes.

The Keystone Kops on the job: running … (photo credit 2.2)

… crashing … (photo credit 2.3)

… and living up to their reputation for crime-fighting (photo credit 2.4)

With the Kops, there was always frenzied activity. In 1958, when Sennett was in his late seventies, he gave an interview to Newsweek magazine in which he defined comedy: “The key is comic motion, which is sometimes like lightning. You see it, but you don’t hear the thunder until seconds later … A wise guy once asked me, ‘What exactly did you have to know to be a good Keystone cop?’ I said, ‘You had to understand comic motion.’ ”

Most experts agree that the high point of Kopdom was the 1914 two-reeler In the Clutches of the Gang. The Kops are called in on a kidnapping case, and their bumbling Chief Teheezel (the admirable Ford Sterling) urges his inept crew forward with the usual incompetence. Paying no attention to their leader, and more or less bungling everything they try, the gang end up arresting the mayor in one of their larger miscarriages of would-be justice.

The Kops were always a collective unit, famous for being the Kops, sort of like Our Gang and the Dead End Kids. Audiences knew some of their individual names but probably not all. They were like one actor, a unit of movie meaning and pleasure, not distinct from one another. The original seven Keystone Kops were Charles Avery, Bobby Dunn, George Jesks (who became a screenwriter), Edgar Kennedy (famous for his slow burn, which he carried over into sound), Hank Mann (with the walrus mustache and the droopy look), Mack Riley, and Slim Summerville (the skinny, homely guy who not only went on to sound as an actor and director, but who gained immortality when a studio head described Bette Davis as having “as much sex appeal as Slim Summerville.”) As time passed, other comics came and went in the Kops aggregation: Fatty Arbuckle, Chester Conklin, Charlie Chase, James Finlayson, Henry Lehrman, Eddie Sutherland, Eddy Cline. The great chief of the Kops, the bearded man who presided over the chaos, was Ford Sterling.

The Kops … a cake … (photo credit 2.5)

The Kops are a brilliant concept. To take a gaggle of inept policemen and display them over and over again in a series of riotously funny physical punishments plays equally well to the peanut gallery and the expensive box seats. People hate cops. Even people who have never had anything to do with cops hate them. Of course, we count on them to keep order and to protect us when we need protecting, and we love them on television shows in which they have nerves of steel and hearts of gold, but in the abstract, as a nation, collectively we hate them. They are too much like high school principals. We’re very happy to see their pants fall down, and they look good to us with pie on their faces. The Keystone Kops turn up—and they get punished for it, as they crash into each other, fall down, and suffer indignity after indignity. Here is pure movie satisfaction.

… and the inevitable (photo credit 2.6)

The Kops are very skillfully presented. The comic originality and timing in one of their chase scenes requires imagination to think up, talent to execute, understanding of the medium, and, of course, raw courage to perform. The Kops are madmen presented as incompetents, and they’re madmen rushing around in modern machines. What’s more, the machines they were operating in their routines were newly invented and not yet experienced by the average moviegoer. (In the early days of automobiles, it was reported that there were only two cars registered in all of Kansas City, and they ran into each other. There is both poetry and philosophy in this fact, but most of all, there is humor. Sennett got the humor.)

The Kops go fast because they can. They whiz along, as when they’re dragged on their bellies, single file on a rope, behind a speeding automobile that takes a fast corner and inadvertently wraps them around a telephone pole, breaking the rope and setting them loose. Along comes another car, however, and it accidentally reattaches them, jerking them off the pole and back out onto the highway, again on their bellies at top speed. The miracle is not that we laugh but that they weren’t killed.

Watching a Keystone Kops chase today is almost like watching a dream sequence, in that many prints have no musical accompaniment and one sits in deep silence as people fly through space, suffer falls, collisions, and bumps apparently without harm. These movies have a manic quality, a terrific pacing in which, as the speed escalates, they almost seem to fall away into a kind of serene flow of safe movement, a warp speed of comedy. Nothing bad is going to happen here, but everything that can go wrong is going to go wrong. You’ll fall down—but get up. You’ll be knocked off the pier—but not drown. You’ll be chased by bad guys—but get away. Perfect timing safely presents characters in a weird and abstract world, a Caligariesque place. A dreamlike state at high speed. It’s the American dream, all right: just keep moving and everything will turn out fine. As the great Satchel Paige famously observed, “Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you,” and with the Kops, it always is. (One of the Kops once allegedly remarked, “I was even kicked by a giraffe.”)

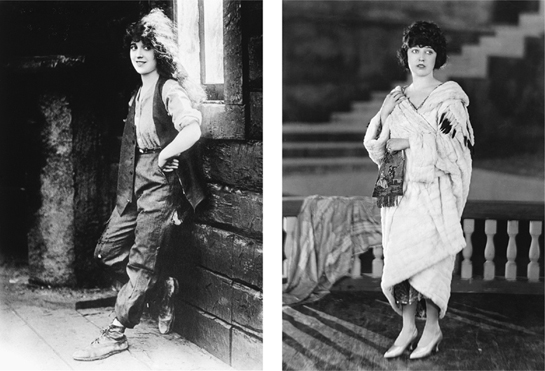

ALTHOUGH THE KEYSTONE KOPS didn’t achieve top fame individually, Mabel Normand became Sennett’s biggest and best attraction. There is still nobody quite like her, because she was everything at once. Another of the tiny women of silent film, Mabel could nevertheless project herself into tall if she had to, even suggesting a willowy, elegant mannequin if the part called for it. She could also become a little boy, a pretty young girl, and a daredevil stuntwoman. What she had was plenty of talent, with the good looks the visual medium required and comedy timing that was nothing short of perfection.

Watching Mabel Normand is a challenge. In one movie, she looks like Buster Keaton (or maybe Stan Laurel), and in the next she’s Gloria Swanson. She wasn’t one of the little boy–girls of the silent era, because she had the body of a sex symbol: bosomy, curvaceous, and well formed. Yet because she was so small, she could disguise herself as a boy in baggy pants, a flannel shirt, and a loose cap, and because of her athletic ability, get away with it. But she could also, as a comic once said, “clean up real good,” swanning out with a fur muff, a diamond necklace, and a hat with an ostrich feather on top. Her glamorous shape, which made her a beauty and a desirable woman, was undercut by her big head (which looked even bigger with the enormous poundage of hair that women wore in those years) and a big pair of clown’s feet. She was by nature a contradiction perfect for comedy: a sexy, full-bodied woman with the head and feet of a clown. In other words, Mabel Normand is a true comic, but a beautiful one, who looked elegant one minute and hoydenish the next. She isn’t in the tradition of the actress who becomes a comedienne because she’s basically homely and can never play romantic leads. She wasn’t driven to comedy because her nose was too big, her teeth too bucked, or her voice too gravelly (anyway, audiences couldn’t hear her speak). As the beautiful comedienne who wears gorgeous clothes but also does pratfalls, Normand is the forerunner of a comedy tradition that American women excel at: the female comedy hero, like Lucille Ball, Betty Hutton, and even Carole Lombard, who took plenty of slapstick hits in her time. In America, we ask our women to sacrifice glamour if the situation calls for it, because we prize the “good Joe” quality in women. A heroine needs to be able to roll with the punches, take it on the chin, and dish it out as necessary. Mabel Normand could and did do all this in spades, and she more or less defined the tradition.

Unlike many of the early stars of the silent era, Mabel Normand wasn’t trained in the theatre. She was never taught how to project, or declaim, or gesture. She entered the movies in a natural state—and she retained that naturalism. She just wheeled in, full of high spirits, afraid of nothing and no one, and with no sense of herself as a great actress worried about her dignity. The people she fell in with most closely shared her love of life, practical jokes, and high living, and most of them were making comedies. Mabel was like one of those characters who are standing innocently on the street corner when the Keystone Kops roar by at what looks like a hundred miles an hour. The car sideswipes her and inexplicably she falls inside, drawn into the chase, hanging on to her hat but game for the ride. As it turned out, Mabel was more game than anyone else. Her ride was a wild one, but, alas, it was also a short one.

All the silent film stars fell prey to the fanciful biographical invention that the fan magazines loved to create for the adoring public. Just as Tom Mix was supposed to have been born in a log cabin in Texas, and Valentino was the son of a nobleman, Mabel had her own tall tales. The chief difference was that she tended to invent them herself. According to her biographer, Betty Harper Fussell, Mabel liked to say that she “had set off for Manhattan from Boston after inheriting a legacy from a seafaring uncle enriched by the Oriental trade” or that her mother had sent her out when she was “only thirteen, to bear her share of earning for the needy household.” What really happened was that Mabel sent herself out in about 1908 to seek her own fortune, knowing she could rely on herself better than on anyone else she knew. She had been born in Boston in 1892 (her crypt claims 1895), an uncommonly pretty little girl with a strong will. She went to New York City and became a successful advertising model, stepping up to the more prestigious label of “artist’s model,” posing for the covers of such magazines as the Saturday Evening Post. Nevertheless, money was always tight, so when she heard about the good pay for appearing in movies at Biograph, she took the trolley downtown to Fourteenth Street, climbed the stairs, and met a man who turned out to be D. W. Griffith’s assistant. She was soon hired, but only as an extra girl. However, she also met someone who was going to be very important to her future—Mack Sennett, who had been working for Griffith for about two years, and who was at least twelve, perhaps fourteen, years older than she was.

When the Biograph company made its first move to California, in 1909, Mabel Normand was not invited to come along. It’s easy to see that she wasn’t D. W. Griffith’s type, hardly being a Victorian maiden and having no experienee of serious acting. Griffith suggested that she try finding work at the Vitagraph Studios in Brooklyn, and her first movies are listed by Fussell as 1910 Vitagraphs: The Indiscretions of Betty, Over the Garden Wall, Willful Peggy, and Betty Becomes a Maid. When Sennett returned to New York with Biograph, in 1911, he talked Griffith into hiring her, making the point that Griffith could use her in his dramas and he himself could put her to work in his comedies. The first movie Mack and Mabel made together was The Diving Girl, in August of 1911, and it showcased everything Mabel had to show. Wearing a bathing costume with black stockings and slippers and a kerchief on her head, Mabel strikes a blow for the all-American female of the twentieth century. She plays a tomboy who likes to dive, and Sennett let her pose at the end of a diving board like a little goddess. The story concerns the effect she has on everyone, until her uncle persuades her to go inside. Mabel is fresh and perky. Instead of peeking into a nickelodeon to see some hootchy-kootchy dancer of an advanced age wiggle her rear, Americans got to see a pretty young girl strut her stuff. And Mabel could strut. It was the beginning, not only for Mabel the star but for Mack and Mabel, the comedy team, and somewhere along the line, Mack and Mabel, the lovers.

One of Keystone’s handouts for fans: Mabel Normand, the “Keystone Girl” (photo credit 2.7)

Sennett once said that the essence of comedy was “contrast and catastrophe involving the unseating of dignity.” By that definition, Mabel Normand was a perfect leading lady for Sennett because she carried within her an inherent dignity and beauty that she wasn’t afraid to toss to the four winds, thus providing her own contrast. Mabel could run very fast, jump very high, and fall down very hard. Mabel could dive from a high rock, and hang out of an airplane with a smile on her face. Mabel could steer a car with pie on her face, and drive fearlessly at high speed. Mabel could do it all, and she did. (Unfortunately, as it turned out, she did a little too much of everything off-screen, too.)

Griffith also used Mabel, most particularly in the 1912 Mender of Nets, which costarred her with Mary Pickford. It was the first film Mabel made in California, having just arrived there. (By the time she returned to New York again, it would be New Year’s Eve in 1915, and she would step off the Twentieth Century Limited train a tremendous star, rich and famous and adored, and known everywhere as “Keystone Mabel” or “The Sugar on the Keystone Grapefruit.”) Mabel and Mary make a perfect contrast—Mabel’s dark hair and Mary’s blond, Mabel’s sexy body and Mary’s little-girl form. Mabel steals Mary’s beau but dies after giving birth. Mary proves her worth by caring for Mabel’s child. The movie was dubbed “a seaside romance,” and Mabel was cast as “The Weakness: His Old Infatuation.”

Mabel in action (photo credit 2.8)

When Griffith again returned east with Biograph, Sennett, Kessel, and Bauman stayed behind and started Keystone, and Mack and Mabel were off on their wild comedy ride. Their first two movies were The Water Nymph and Cohen Collects a Debt, in 1912. Betty Fussell eloquently describes the formula they were going to follow by saying that “from the beginning, sex, crime, and money were the source of the Keystone comedy and the context of their lives. Mabel provided the sex, the male clowns provided the crime, and the combo brought in the money.” The formula worked. The troupe ground out the two-reelers: Mabel’s Lovers, A Midnight Elopement, Saving Mabel’s Dad, The Mistaken Masher, A Red Hot Romance, and many more, fifty-three pictures within the first Keystone year (1912–13). However, according to Fussell, only seven of them exist today. One is the aforementioned Bangville Police and another is Barney Oldfield’s Race For A Life (1913). Barney Oldfield, a famous race car driver of the era, plays himself in a delightful example of the Mack and Mabel style. Mabel plays “Mable, Sweet and Lovely,” and Mack plays “a bashful suitor.” Cleverly using familiar ploys from the popular melodramas of the day, the movie provides a comic variation of the damsel-in-distress story, with Mabel ending up tied to the railroad tracks while the villain twirls his mustache, and Mack and Oldfield racing to the rescue in Oldfield’s famous car. One of the great treats of the movie is a scene in which Mack woos Mabel, shyly handing her a flower. They are both young, slim, healthy, full of beans—and clearly in love with each other. It’s a golden moment frozen in time.

Mack and Mabel were on a roll, making other 1913 hits such as Mabel’s Awful Mistake, Mabel’s Dramatic Career, The Gusher, The Speed Queen, Mabel’s Heroes, and For the Love of Mabel. In the first of these appears one of those images automatically associated with silent film: Mabel and a buzz saw! A handsome man persuades her to elope with him, even though he already has a wife and a bunch of kids. Her boyfriend follows the elopers, and watches outside while poor Mabel is tied to the table with the buzz saw coming at her. This scene had already become a cliché, having been fully explored in the serials starring the intrepid heroines of The Perils of Pauline and The Exploits of Elaine. Sennett and Mabel and the gang send up the idea, spoofing those heroines and turning the villain into an exaggerated cartoon. The genius of this plan was that the send-up is funny, yet still tense and scary. The audience got more bang for its buck. (Sennett never forgot that comedy was partly rooted in tension, and that frightening situations followed by the release of a laugh always pleased a crowd.)

In Mabel’s Dramatic Career, Mabel plays a hired girl who becomes a movie queen. Her coplayers are Mack Sennett, Ford Sterling, and Fatty Arbuckle. The film is particularly interesting because in it, Sennett, as her former boyfriend, goes to see a Keystone Comedy that Mabel is starring in. (The title of the movie-within-the-movie is Mabel and the Villain.) The Sennett character, who loves her, starts waving at the screen and shouting, eventually shooting at it because Mabel is in danger before the Kops arrive to save her. (In the movie-within-the-movie they are called the “Keystone Kids.”) After the movie is over, Sennett walks out and sees the actor who played the villain—actually a mild-mannered family man—and takes out after him. This Pirandellian concept is very modern. A similar idea would be used in 1916’s A Movie Star, which shows great sophistication in its send-up of the popular westerns of the era. Mack Swain plays a movie star who poses outside a theatre, standing by his own photo, until his female fans finally notice him. This movie has a film-within-a-film called Big Hearted Jack, and Swain loves watching it with the audience. The females continue to mob him—until his wife and kids show up. It’s interesting that as early as 1916 there was a complete awareness of what the movie star’s problem was going to be: the contrast between image and reality!

In The Gusher, Mabel copes with an out-of-control oil well and various attempts to poach on her discoveries. In The Speed Queen, she’s arrested for speeding, and in For the Love of Mabel, she has to be rescued from a dynamite bomb. In all these movies, Mabel worked like a Trojan, never shying away from the thick of the wildest action. She was a true daredevil, evolving from the pretty youngster originally billed as “the Venus diving girl” into a slapstick comedy queen who executed stunts that would have stopped any other movie star in her tracks. There was no trick to Mabel Normand. She went out on her own and did it all, without gimmicks, without camera cheats, and without, presumably, any real fear.

In 1914 Sennett undertook a highly ambitious project: Tillie’s Punctured Romance, advertised as “The ‘Impossible’ Attained—A SIX REEL COMEDY!” Sennett’s idea was to make a comedy that had status. Griffith had begun shooting a full-length feature, Birth of a Nation, on July 4 (to be released in early February 1915). If Griffith could make a film like Birth of a Nation, why couldn’t he, the King of Comedy, lift comedy movies to the same heights? Tillie’s Punctured Romance was one of the greatest hits of the Sennett troupe, with Chaplin, Normand, the Kops, and Marie Dressler all appearing together. Often referred to as “the first feature-length comedy,” it is a full six reels. Sennett’s backers thought he had gone mad, but the film was an immediate winner.

Chaplin plays a bounder whose accomplice in fleecing naive women is his girlfriend, Mabel. Their target is the hapless farm girl, Tillie, played magnificently by Dressler, a major stage star who had made a big success on Broadway in a comedy called Tillie’s Nightmare. Sennett had the story adapted for the screen, and to fill out the expanded running time, he comes up with trick after trick. Despite the competition of Chaplin and Normand, Dressler makes the film her own. Her large size is played with, as she goes about bumping into things (shattering them). When she playfully tries to flirt with Chaplin by slinging a sexy hip out toward him, she knocks him flat. She goes with Chaplin to the city dressed in an outfit that belongs in the Smithsonian: a print monstrosity covered with ruffles and a long string of beads, topped off by the world’s most improbable hat with a duck—or is it a goose, or perhaps a swan or a chicken?—smack dab on top of it. Mabel plays Dressler’s opposite: cool, elegant, and dressed in great taste—well, great comedy taste, anyway. She’s very glamorous. Mabel has a wonderful scene in which she and Chaplin go to a movie entitled The Thief’s Fate, and she sees the girlfriend of the thief get arrested. This starts her thinking, and after much action, including a ballroom dance between Dressler and Chaplin that is a direct satire on Vernon and Irene Castle, and a great chase in which Dressler falls off a pier, the movie ends with an ironic look at Chaplin. “Curse the beauty that holds women slaves to such men,” jokes a title, and suddenly, Normand and Dressler, two great queens of silent film comedy, embrace, throw Chaplin out, and declare, “He ain’t no good to either of us.”

Mabel and her popular partner Fatty Arbuckle, in Mabel, Fatty and the Law (photo credit 2.9)

The years 1914–16 brought more of the same Sennett fare for Mabel, including Mabel’s Nerve, where she rides a bucking bronco, and Mabel at the Wheel, in which Chaplin tries to sabotage a road race but Mabel saves the day by taking the wheel herself and driving madly to victory. In movies like this, Mabel was a kind of pratfall Pearl White, combining her athletic ability, her nerve, and her beauty to make her the comic relief, the romantic lead, and the stuntwoman all in one person.

Mabel in the big hit Tillie’s Punctured Romance (photo credit 2.10)

Mack Sennett not only made Mabel Normand a star but was instrumental in combining her with a great comic foil, the underrated genius Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, a Jackie Gleason/Oliver Hardy prototype. Arbuckle started working with Sennett in 1913 for five dollars a day, and Mabel—a shrewd judge of talent—saw his potential. Watching him work, she noticed how many different things he could do, and in particular realized that he was amazingly light on his feet. She talked Sennett into starring her with Fatty, and within a short time the two comedians were Keystone’s most popular team.

Fatty was five feet ten inches to Mabel’s barely five feet, and 266 pounds to her less than 100. Together in the frame, they were a great visual joke: a big, fat guy and a tiny woman. Just the way they looked standing side by side could get a laugh, and their contrasting size and shape were exploited for all kinds of comic variations. Arbuckle was also an excellent acrobat, so he could match Mabel’s athletic ability. Their work together was a glorious blend of compatible comic styles. Fatty could fume and Mabel could flounce.

The best title of all the Mabel and Fatty movies is the 1913 Passions, He Had Three (they were milk, raw eggs, and girls). Fatty is a doctor and Mabel is his elegant wife. In the brief running time, Fatty tries to tie his bow tie and Mabel has to help (a brilliant piece of physical comedy). Mabel’s old school boyfriend comes to dinner and Fatty gets jealous. They sit down to eat lobsters, which gives them nightmares that turn into dream sequences, and in the meantime that old favorite, a burglar (posing as a cripple), interrupts the meal and later tries to rob the house. It ends with everyone running up and down stairs and around the elegant house, showing off the furniture and providing hilarious pratfalls and entrances and exits.

Mabel continued to appear without Fatty during these years. Among these solo efforts was one of her most popular movies, Mabel’s Blunder (1914), in which both her boss and his son have designs on her. Again, an elaborate scenario plays out within a short running time: Mabel pretends to be her brother, her brother pretends to be her, her boyfriend kisses another girl but it’s really his sister, which Mabel doesn’t know, etc. Mabel, stylishly dressed, shows herself to be a master of comic pantomime. There’s a particularly superb moment in which, dressed as her brother in long coat and with a cap pulled down over her eyes, she swiftly pilots a big open-air car down the streets of Los Angeles, a simple act that shows exactly who and what she was: a modern girl of speed and daring, unafraid of the new machines.

The title cards of these comedies rely very little on detail. Instead, they speak simple facts: “A MISUNDERSTANDING,” or “TROUBLE ARRIVES.” The stories are complex, however, and one must pay attention. A lot of detail is never explained or presented, and the audience is asked to make assumptions and draw conclusions—or just go with the flow, waiting for the big chase scene. An actress like Mabel is essentially pantomiming a great deal of her character’s story, and this is not exactly the same as acting. What is remarkable about her is that she was able to grow, moving beyond such simple demonstrations in which the object is never subtle emotion but always the broad event for comic purposes.

Even while her career was thriving, Mabel was frequently ill with respiratory problems. She complained of sinus trouble, bad headaches, and a chronic cough, and was reported to be frequently hemorrhaging, a sign of tuberculosis. However, she made no effort to rest as a result of these problems. Rest was not a part of Mabel’s lifestyle. She partied all night, worked nonstop, and medicated herself with a concoction she referred to jauntily as her “goop,” a cough syrup available over the counter but which was laced with opium.

In December of 1914, Sennett announced that “Mabel Normand, leading woman of the Keystone Company since its inception, is in the future to direct every picture she acts in.” Mabel directed only movies in which she starred, but her accomplishment as one of the first female directors, and one of the few to do comedy, is singular. She and Mack Sennett had formed a true creative partnership—or so it appeared. By the end of 1915, their combined efforts were solidly established. They were not only a moviemaking team; they were also an item. However, a marriage planned for July 4, 1915, derailed at the last minute, allegedly because she walked in on him in bed with the beautiful Mae Busch shortly before the ceremony was to take place. They were soon quarreling both on and off the set.

Motion Picture World of July 1915 listed Mabel as one of the winners of a popularity contest to determine “The Great Cast.” Pickford won “leading woman,” Chaplin won “male comedian,” and Mabel, “female comedian.” Yet, Chaplin was given a raise at Essenay and would begin earning $5,000 per week. Pickford was raised to $5,000 per year, and she was earning a percent of profits, a six-figure bonus each year, and a generous weekly expense account. Mabel was paid $5 per week—and there was no increase in sight. But she had become a big star, and she wanted more: more money, more control of her films, more respect, and more opportunities to play romantic leading ladies in feature-length films. Disgruntled, she accompanied Fatty to New York at the end of 1915 to make a group of short films with eastern settings. When she returned to Hollywood in May of 1916, she demanded her own production company. Sennett reluctantly agreed, and established the Mabel Normand Feature Film Company.

With this newly acquired status, she reported to work at her own little studio that Sennett built for her, located just over the hill from his, and settled down in her own dressing room with a Japanese chef, an Oriental rug, and a canary. And she began work on a feature film that was designed to allow her to make the kind of transformation within the plot that Mary Pickford handled so successfully in her tailor-made movies: from tomboy little girl to romantic leading woman. The film was to be called Mickey, and from the minute that production began in 1916, it was a war of wills—and a fight for control—between Mack and Mabel. Filming was completed in the spring of 1917, and after shooting ended, Mabel left Sennett to sign with Samuel Goldwyn. “I decided I’d had enough of the Keystone Company,” she said.

Mickey, which was not released until August 1918, was an enormous hit. Mabel’s reviews were excellent: “Mickey and Mabel Normand are one and the same … She could not have appeared in a title role in which she was better suited … She is a wonderful little actress,” said Variety. Mabel is dressed, as so many silent film stars often were, in patched trousers, a flannel undershirt, and a coat way too big for her, which served to emphasize her tiny frame. She plays the perfect tomboy, always getting into trouble, who is sent east to live with rich relatives. Naturally, these are horrible people who turn her into a servant—a bad idea, since she wrecks everything she touches until, of course, she snags the handsome young man who appreciates her honest qualities and loves her, only her.

Even before the release of Mickey, everything Mabel did was news, and since she did so much, the fan magazines ate her up. She became famous for her beautiful clothes and her wild lifestyle, which included not only playing bizarre practical jokes on coworkers but also out-of-control drinking and partying. Mostly, the magazines paid tribute to her comedy skills. In June 1918, Motion Picture dubbed her “Thalia … the muse of comedy” in an article called “The Muses of Movie Land.” (Pickford was Calliope, the Muse of Eloquence.) But though the fan magazines cleaned up her act, they hinted at the erratic behavior in thinly veiled articles like one called “Mabel in a Hurry,” in the November 1918 Motion Picture. The interviewer tells us of his “thrilling day with Mabel Normand,” referring to her, however, as a “young lady of tempestuous moods and moments.” To illustrate, he cheerfully writes of how he waited for her on the set from 9:30 to 11:30 a.m. (To make sure the point gets across, he adds that the studio guide told him that Normand “never keeps an appointment. If she has an appointment for 4, it usually occurs to her to begin dressing for it at 4:30.”)

Mabel as the comic hoyden in Mickey … (photo credit 2.11)

Mabel, however, finally turns up. “In décolleté, partially hidden by a dressing robe,” she dashes in. “Rushed! Late! Back in a minute!” After her rehearsal, she does return to talk to the writer, telling him about her latest location shoot, about her new maid acquired from a millionaire’s home, about how her two greatest weaknesses are black lace stockings and dime savings banks, and how she cares only for purple flowers. She snaps at him when he wants to talk of other things, and he allows himself to write, “She has a chameleon personality.” At some point in the discussion, Mabel really takes off, telling him she once lived for thirty days on ice cream, that she thinks Charlie Chaplin is the screen’s greatest actor, and that she always signs her letters “Me” and calls people “Old Peach” if she likes them. (She does not call the reporter “Old Peach.”) She would rather do drama than comedy, but drama with an occasional smile. She always carries a tiny ivory elephant for good luck. As they conclude their conversation at 1:30 p.m., the interviewer really nails her, saying that in nearly four hours, they probably talked “fully eight minutes in all,” and adds that someone once told him Mabel Normand reminded him of a “dancing mouse, whirling madly all the time, but without purpose.” It’s hard to tell today whether Mabel was giving a performance or revealing her normal self. At one point, she tries for pathos, real or feigned, by saying that while she must seem ever so gay most of the time, she really isn’t. “I get terribly blue and sad. Life is such a rush.” But her final shot at the reporter probably gives the real picture. “Good-bye!” she suddenly sings out, dismissing him summarily. Turning to her maid, she then bellows out, “Gimme my grapefruit and a gas mask.”

… and as the would-be star in The Extra Girl (photo credit 2.12)

Mabel went increasingly out of control in her interviews. She was once reported to have said, in answer to a standard fan magazine query about what her hobbies were: “Say anything you like, but don’t say I like to work. That sounds too much like Mary Pickford, that prissy bitch.”

After Mabel left Sennett for Goldwyn, the interviews became even more erratic. She told reporters such things as “I love to punch babies and twist their legs” or, in describing her ideal man, “A brutal Irishman who chews tobacco,” or “I love dark, windy days when trees break and houses blow down.” There is anger in her words, and she began to be late to the set and behave erratically with people, going out to lunch and ordering nine martinis and a baked Alaska. She spent money recklessly, and during her Goldwyn years she perhaps went beyond her “goop” and fell under the spell of drugs, never fully to recover her health again.

In the wake of her huge success with Mickey, Mabel was at the top of her stardom, and Goldwyn promoted her heavily. She made a series of popular films for him, many of which have titles that sound like ideal Mabel movies: The Pest, Peck’s Bad Girl, A Perfect 36, Sis Hopkins, Jinx, and Slim Princess, among others. The only one available for viewing today is the 1921 What Happened to Rosa? Directed by Victor Schertzinger, it presents Mabel as a little department store clerk, “Mayme Ladd,” a dreamer whose “dull, drudging life has never been brightened by a single gleam of romance.” Mabel is perfectly cast as the little comic loser, her big eyes rolling and her hair hanging in her face. Her expressive body and excellent timing are put to good use in her comedy scenes, and her true beauty is drawn on when she turns into Rosa. Mabel’s character consults a psychic who gives her a “prelim spirit shampoo,” tells her she is inhabited by the spirit of “Rosa Alvaro, a beautiful Spanish maiden,” sticks a rose in her teeth, and says calmly, “That will be five dollars.”

Mabel looks tired, but she’s still up to the down-and-out clowning. She plays out an extended comic sequence in which she wrestles with putting silk stockings on the legs of a store mannequin, and after having to swim to shore off a pleasure boat, she makes a comic tour de force out of pulling a fish from her blouse. It is obvious in this film what a compelling personality Mabel Normand really was, especially when she portrays the beautiful Rosa. Such a romantic beauty is well within her range, not just because she is good-looking but because she has considerable dramatic ability. (Many thought that she could have been the greatest dramatic actress of her time had she so chosen.) When the action calls for her to dress up as a boyish street urchin, her physical comedy reaches a high point, and she can still do it with great energy. Rosa, however, was not a big success, and everyone realized that Mabel Normand was ill. Her life had taken on an even faster pace, the acceleration appearing somewhat the way the old Sennett chases were conducted: start slow, move out, then take off at high speed and never let up until the chaos explodes and there’s no future.

Mabel had made no real progress. Now she was grinding out movies for Goldwyn the same way she had once ground them out for Sennett. In the beginning, Goldwyn had promoted her the way she wanted to be promoted, wearing lovely clothes and romantically photographed; he treated her with what she thought of as class. He had promised her he would present her in “artistic” movies, and her first film was a serious drama, with some comedy, Joan of Plattsburg, in which she played an orphan who imagines she’s Joan of Arc reincarnated. Filming went badly, and Goldwyn shelved it, shoving Mabel into a full comedy, Dodging a Million. When Joan was later released (in May 1918), the miscast Mabel was criticized by Variety as not having the required “spirituality.” After that, Goldwyn fell back on the popularity of her character from Mickey. The rest of the sixteen features she made for him over the next three years were slapstick romantic comedies. Disenchanted, Mabel began to give Goldwyn and his staff the same kind of hard time she had once given Sennett. “Oh, what a little devil she was,” said Abraham Lehr, Goldwyn’s manager.

In 1920, the Goldwyn Pictures Corporation collapsed, and Mabel completed her filming for him by the end of that year.* Shortly after, Sennett announced that Mabel Normand would return to his company. These years of Mabel’s life are hazy. Her biographer, Fussell, whose research was thorough, admits, “I was confused about Mabel’s chronology” because “until [the fall of 1919] Mabel was turning out a feature every two or three months. Then there were long stretches between films.” Fussell feels that, during this time period, Mabel went to what fan magazines and friends called “a small New England village” to rebuild her “wrecked nervous system.”

In 1921 she made Molly O’, and in 1922 Suzanna, both with Sennett. Both were Mickeyish stories. The former is a Cinderella plot in which a sweet girl marries a rich hero, and the latter is a costume film set in Spanish California, also in the Cinderella mode. She received excellent reviews for the first, with Variety reporting, “Mabel Normand does manage to get to the audience … The picture will get patronage.” The New York Times also predicted the masses would like it, but gave Mabel credit by saying the film’s success was “due chiefly to the pantomime of Mabel Normand.” For Suzanna, Variety said Mabel’s performance was “a worthy feature” of the story, also pointing out that she had been toned down, and was playing a more refined heroine than usual, but not without losing all of her tomboy mannerisms. It seemed that Mack and Mabel were trying to compromise—give her a little romance and a little slapstick, mixed together.

Mabel continued her by now established pattern of work hard, play hard. Explaining herself as “shanty Irish,” she reeled along through life and got away with it because she was generous and lovable. Blanche Sweet said, “We all granted her the license of an enchanted princess … When she spoke, toads came out of her mouth, but nobody minded.”

The public, however, was about to start minding. While Mabel was becoming more and more famous for her fancy clothes, big spending, out-of-control interviews, and wild life, the public’s romantic vision of Hollywood and its stars started to come apart. The first big scandal occurred in September of 1921, just before the release of Molly O’, and it involved Mabel’s old costar, Fatty Arbuckle, who was accused of a particularly obscene rape which resulted in a starlet’s death. Although Fatty was ultimately acquitted after three successive trials, his career as a charming fat comic was virtually ended. Then in 1922, while she was filming Suzanna, the handsome director William Desmond Taylor was shot to death, and rumors said he was wearing a silver locket containing Mabel’s picture. Mabel, the last person to see him alive, had her name drawn into the mess, as she had been involved with him. Perhaps to rest and perhaps to escape the scandals, which had taken a harsh toll on her, Mabel left Hollywood and fled to Europe in 1922 on an extended “grand tour.” When she returned, things seemed to be getting back to normal until—ten days following the successful release of Suzanna—another scandal occurred. On January 14, 1923, the handsome Wallace Reid, known as an all-American, clean-cut actor, suddenly died and was revealed to have been a drug addict. Although Mabel had no direct connection to Reid, the known presence of drugs in Hollywood made Mabel and her environment subject to even closer scrutiny and newer, deeper criticisms. But the worst was yet to come.

First, however, came The Extra Girl (1923), one of Mabel’s best movies, although not a huge success at the time. With a story written for her by Sennett, Mabel plays a small-town girl who tries to get into the movies, but fails. She’s given a job as prop girl, and in one excellent sequence she places a lion’s head on a dog—the usual way the cheapo outfit she works for creates a lion—only to have a real lion show up, a case of mistaken identity similar to the leopard charade in Bringing Up Baby. Mabel ambles around the studio dragging the lion behind her, pushing it, cajoling it, and bossing it around with total confidence. She’s both hilarious and touching, and the action plays out in a way that affords her the chance to show her stuff at the highest level.

Finally, just after the release of The Extra Girl, on New Year’s Day, 1924, another big scandal hit Mabel. Her chauffeur, Joe Kelly, shot the playboy Courtland Dines, and “Kelly” turned out not to be his real name; he was an ex-con named Horace Greer. Although Dines didn’t die, Greer had shot him with Mabel’s own gun while Mabel and Edna Purviance were in his bedroom changing their clothes for dinner. Various reports of drunkenness were included in the different versions of the story people put forth regarding this event. A definitive statement was made by the state attorney general of Ohio, as he announced the state’s banning of Mabel’s movies: “This film star has been entirely too closely connected with disgraceful shooting affairs.”

A spunky Mabel in Mickey, and showing some effects of her high living in Molly O’ (photo credit 2.13)

The story of the life of Mabel Normand becomes increasingly visible on her face as the years go by. She begins to look thin. Circles appear under her eyes, and she has the nervous, slightly askew look that might be associated with mental illness, a physical malady—or alcoholism and drug use. Comparing a series of photographs of her shows clearly what was happening to her, and how rapidly it was happening. In 1916, as she prepares to shoot Mickey, she poses in her costume for the film. Relaxed and smiling, she leans against a cabin wall by a window. Her hair is thick and long and full, her eyes dark and mischievous. She wears a man’s shirt, vest, and pants, with a pair of old shoes on her big feet. Her hand is on her hip. She looks saucy and ready for anything. A photo taken in February of 1920 on location for Pinto shows her in a similar outfit: pants, plaid shirt, and boots. She’s reading a newspaper and looks haggard, dark circles under her eyes and an obvious tension around her mouth. A third photo, taken in the late twenties, reveals her as a sad-eyed woman without a smile, dressed in expensive silks and satins, studded with jewels, a fur coat loosely draped about her shoulders. There is a bored look to her, but also a haunted, gaunt quality. Still quite young, she’s already looking burned out.

After the Dines scandal, Mabel’s career began to fall apart. She began to drift even more, spending money recklessly, drinking even more heavily, and finally leaving Hollywood for an unsuccessful attempt at a stage career in New York. Although her fans turned out loyally, her reviews were not good. She returned to Hollywood in 1926 at the invitation of Hal Roach, who gave her a three-year contract for eight short comedies and eight features. Sadly, she completed only five of the shorts before her contract was terminated: The Nickel-Hopper, Raggedy Rose, Anything Once, Should Men Walk Home?, and One Hour Married. Nickel-Hopper and Raggedy Rose (both in 1926) are typical examples.

In Nickel-Hopper, she effectively plays a little slum girl who works all day scrubbing floors and baby-sitting, and all night as a dance instructor who gets “2½ cents a dance.” She’s on top of her comedy action as she’s twirled around the floor at top speed by a series of dangerous partners (or, as the bandleader puts it when the dance begins, “Choose your opponent”). A young Boris Karloff is one of her would-be suitors, but the showstopper is an elderly man with a long beard who dances up a storm. “You’ve been eating too much reindeer meat, Santa Claus,” she tells him. An effective comedy chase and a madcap marriage wrap up the plot.

In Raggedy Rose, Mabel Normand is carrying the ball alone. There’s no Chaplin, no Fatty, no Keystone Kops, and she is clearly taking herself more seriously as an artist. In a frail story about a little ragamuffin who works for a junk dealer, she’s partly reminiscent of Chaplin’s Little Tramp and partly a satire on the waifs with fluttering hands played by Lillian Gish. (In some scenes, she looks a bit like Giulietta Masina.) Her comedy playing is, as always, perfectly timed, sharp, and precisely delineated. When Mabel is given the typical Keystone comedy routine to do, she’s superb. Having heard that a friend of hers who got run over by a car was given a thousand dollars and put in a hospital where she could “eat anything” she wanted, Mabel sets out to get the same treatment. Standing in front of a speeding open-air automobile, she is firmly resigned. The car, a rattletrap, slams on its brakes and falls totally to pieces, and the driver gets out and bops Mabel with one of the fenders. She starts a pillow fight with a rival and her mother, jumps in and out of bed, and does a splendid routine in which she finds a dime in the pocket of one of the old coats she is gathering in her rag-picking work. And there is a glamorous moment in which she dreams of herself dressed beautifully in one of the dresses she’s collected, an elaborate costume with ruffles. In her mind, she dances with her dream prince, wearing the dress and a beautiful hat.

During these years, Mabel’s private life continued to spiral downward. On September 17, 1926, she suddenly and inexplicably married the actor Lew Cody, a heavy-drinking disaster of a man who allegedly proposed to her in a drunken state and was accepted in the same condition. Descriptions of their wedding party, in which they zoom to a justice of the peace with a motorcycle escort and their dinner guests falling out of their overcrowded car, sound suspiciously like a Mack Sennett comedy chase scene. The elopement of two well-known drinkers was met with nothing but cynicism on the part of their friends, the press, the film business, and even the bride and groom themselves. (On the morning of September 18, Cody showed up at a Breakfast Club broadcast in the Hollywood Bowl. He was late, a mess, and dressed in his dinner clothes from the night before. “Fellas,” he admitted, “I went to a party last night … I married Mabel Normand.”)

After her marriage to Cody, Mabel’s career slowly dried up. Her last movie was One Hour Married, released in February of 1927. In 1928 she made no movies at all. By 1929, sound had taken over the industry, and Mabel had other problems anyway: She had been diagnosed early in the year with a serious tubercular infection. About the same time, Cody collapsed with a heart attack and was himself hospitalized. In August, Mabel was taken to Pottenger’s Sanitorium in Altadena, California, and on February 23, 1930, she died. In one of her diaries, dated February 1927, Mabel had written her own best obituary: “WHO CARES?” It was both a plea and a cynical shrug.

The early death of the beautiful and talented Mabel Normand is one of the greatest of all the silent film star tragedies. Wasted and ill, her career more or less in ruins, Mabel died at the age of thirty-seven. The diagnosis was pulmonary tuberculosis. Mack Sennett, on the other hand, lived to a ripe old age, dying at eighty on November 4, 1960. Whereas Mabel hardly had time to put anything in perspective, Sennett lived to write his autobiography, an “as told to” series of inaccurate memories published in 1954. He began his book—and thus the story of his life, with all its events, successes and failures, and parade of celebrities—by saying, “I am an old storyteller, long in the tooth and willing. Once upon a time I was bewitched by an actress who ate ice cream for breakfast.” In other words, when he added it all up, it was Mabel Normand who was on his mind. He called her the “most important thing in my life.” For film fans and scholars, the question is always, Why, finally, did Mack and Mabel never wed? The mystery of their romance and why it failed them is one of Hollywood’s saddest ironies. In their personal relationship, their timing—always so impeccable on film—was obviously way, way off.

Of their famous romance, Mabel Normand said little other than “I made a tremendous fortune for that Irishman.” Sennett was more revealing, saying, “The worst predicament of all is to fall in love with an actress with whom you are in business.” Whatever their relationship off-screen, in the business, it was a power struggle between two artists, each of whom felt entitled to control and to a superior status. Sennett was the driving force behind Mabel’s success, but it was Mabel who was adored by the public. She wanted the kind of growth a big star needs to remain popular. That meant feature films, possibly even dramatic parts, and the same status as others like Mary Pickford and Norma Talmadge, two of her chums when she first entered the business. Sennett was a businessman, and he wanted to keep things low-cost. And he was a down-to-earth maker of comedies who was determined to give the public what it clamored for. It was the age-old Hollywood argument. From Sennett’s point of view, why should he pay Mabel a fortune or let her make decisions? It was also his style not to put stars under contract or let them demand exorbitant salaries. (Over the years, a wealth of talent moved through the Sennett studios, going on to better salaries and star status, if not always better material.) Mabel’s attitude was based on what she knew to be her worth.

Sennett’s book reveals his appreciation of how special Mabel really was. “When Mabel Normand went anywhere at all, or did anything at all, it was with all flags flying. When she bought hats, she bought thirty, wore one, and gave the others away. When she had those French people make her gowns and evening dresses, she ordered by the dozen—and wore only one. Mabel was like—she was like so many things. She was like a French-Irish girl, as gay as a wisp, and she was also Spanish-like and brooding. Mostly she was like a child who walks to the corner on a spring morning and meets Tom Sawyer with a scheme in his pocket … Mabel was all about emotion.” Obviously he loved her. When asked why he never married her, he said, “I can’t explain it, even to myself.” In the very last interview of his life—June of 1960—he said, “I’ve always regretted not marrying her.”

There is an explanation of sorts. Mabel wasn’t just a girl who ate ice cream for breakfast. She was also a girl who partied all night, came to work late, and disappeared for days on end. She was involved in the scandals of William Desmond Taylor’s murder, of her chauffeur’s shooting of her boyfriend, of the rumors of drugs and the curse of bad health; she was tubercular, and clearly burned the candle anyplace she could get it lit. For whatever reasons, the perfect comedy marriage never took place, and Mack Sennett died a bachelor. Their story is a kind of warped Citizen Kane of comedy, only Mabel really has talent, unlike Susan Alexander, and they never marry. But Kane/Sennett ends up old and alone, remembering, and whispering his last fond memory. And it’s … “Mabel,” his Rosebud. It’s hard to fashion a comedy out of the private lives of Mack and Mabel, but everything else about all of them—Mack and Mabel and the Kops—is as wonderfully funny today as it ever was. They are the geniuses of American movie chaos.

The quintessential Mabel in full crisis (photo credit 2.14)

* Her final Goldwyn films were released later, in 1921 (What Happened to Rosa?) and 1922 (Head Over Heels).