ONCE UPON A TIME, and that time was not so very long ago, when little boys dreamed of grand heroes who dared and dueled, who fought and won, who leaped and flew through the air, and who always, but always, carried the day, their dreams came true in the form of Douglas Fairbanks. As Frank Nugent’s obituary tribute in the New York Times of December 17, 1939, said:

Doug Fairbanks was make-believe at its best, a game we youngsters never tired of playing, a game—we are convinced—that our fathers secretly shared … There wasn’t a small boy in the neighborhood who did not, in a Fairbanks picture, see himself triumphant over the local bully, winning the soft-eyed adoration of whatever ten-year-old blonde he had been courting, and wreaking vengeance on the teacher who made him stand in the corner that afternoon.

Douglas Fairbanks was a macho dream come true—the hero who was brave and honorable, clean and gallant, full of optimism and conviction. Although he had many imitators in a later age, there was never anyone quite like him.

Fairbanks is not forgotten, and he isn’t unappreciated—but he is remembered as much less than he really was. His career, one of the greatest in film history, has separate halves. Up until 1920, he made energetic comedies in which he played young men who personified the optimism of America in the teens—always on the move, always pursuing a goal, and always the winner of the brass ring through determination and perseverance. After 1920, he stepped out of that pseudorealistic world of the all-American man-boy and began making highly romanticized adventure movies. Today, he is remembered for the latter, and few realize he began as a comedy star, and that it is his comic timing and energy that make his adventure movies great.

It is ironic that Douglas Fairbanks’s career took him forward into a never-never land. Instead of aging into King Lear, he aged into Robin Hood. Instead of beginning to play the fathers of the leading ladies he once courted, he grew ever younger, casting aside all pretense of modern life and carrying the viewer into a land of visual enchantment. For a star with less to offer, such a career move would have meant disaster, but it makes Fairbanks unique. Inside his original movie persona—a young man running down the streets of old Los Angeles, leaping over rooftops, clambering aboard moving trains—was contained a spirit wanting to be free. And free it gets. He steps out of business suits and drawing-room sets into Sherwood Forest … or onto a magic carpet … or a pirate ship … or the streets of old Paris. Boys will be boys, Fairbanks seemed to say … and so will men.

On-screen, Douglas Fairbanks appears as very vital, very virile. He wasn’t a large man, though he wasn’t tiny like some of Hollywood’s male stars. His height is variously listed as between five feet seven inches and five feet ten, and his weight between 145 and 155 pounds. He had dark brown hair and piercing gray-blue eyes. He was somewhat of a health nut, and certainly an early advocate of physical fitness (although off-screen he was a heavy smoker). He kept himself deeply tanned year-round, which not only made him look healthier both on- and off-screen, but seemed to turn him into a magic person from another world where the sun was always shining. (Cary Grant was said to have patterned his own year-round tan on that of Douglas Fairbanks, the man whose style and look he most admired.) He has the kind of physical radiance that is usually associated with female performers, although he is quintessentially masculine. He has it. Sometimes he reminds me of the equally exuberant Al Jolson of The Jazz Singer, Mammy, and The Singing Fool. Like Jolson, he jumps around gracefully, swinging his arms, making broad gestures. He seems about to erupt in song but, unlike Jolson, he erupts by leaping up onto something. One of Fairbanks’s most distinctive physical movements is his upward jump, sometimes facilitated by a trampoline or a springboard, sometimes enhanced by a fence or wall designed to look much higher than it actually is. Everything he did to “act” was physical—the word most commonly used to describe his performances at the time was “exuberant”—and this acting style was perfect for silent films because it was all about using the whole body to express character, attitude, and emotion.

Fairbanks is a joy to watch. He has a light, unpretentious touch. The reviewers of his day always refer to his gusto, his energy, and to his combination of robust and romantic traditions. He appeals “to the young,” they said, and also “to the young in heart.” Inside that cliché lies one of the secrets of the Fairbanks stardom—his ability to connect with grown men as well as with little boys. He understood the male desire for escape, and his movies are a kind of “man’s movie” not unlike the old women’s pictures that gave women a form of pseudoliberation and lots of terrific clothes and furniture to ogle. He welcomed the grown-up masculine viewer into a world of games and exploits, but without asking him to surrender his dignity. It’s highly unlikely that any star could reach the heights that Fairbanks reached and stay at the top as long as he did without having some sense of himself, some sense of the business, and some sense of the medium itself. Fairbanks had all three but was particularly smart about how to reach the adults in his audience. Male stars who have lasted for decades at the box office all had a sense of humor about their image, and have put a touch of irony into their macho heroes.

The three top male box office stars of the sound era, John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, and Bing Crosby, all offered the audience a private wink at their images. Wayne’s swagger and raised eyebrows, Eastwood’s squint and laconic dialogue, and Crosby’s casual ad-libs were the equivalent of Douglas Fairbanks’s mocking laughter. With his head thrown back and his fists on his hips, he is not only embodying the male hero but also laughing joyously at the very ridiculousness of it all. Fairbanks is not cynical the way Eastwood is, but he radiates self-humor. He communicates directly with the audience, suggesting that we’re all in it together, to take things seriously but only as serious escape. Serious fun.

Fairbanks was also a good businessman and a shrewd judge of his own abilities. Griffith, Pickford, and Chaplin, he said, were geniuses, but “I am not a genius.” He knew he pleased crowds, but he also knew his range was narrow. To compensate—and because it was good business—he learned everything he could about making movies, and he surrounded himself with the best of everything. He became a consummate craftsman, with a thorough knowledge of the filmmaking process. Joseph Schenck, the producer, said of him, “This fellow knows more about moviemaking than all the rest of us put together.” Fairbanks hired excellent character actors, none of whom threatened him and all of whom enhanced him. He spent money, especially on his later films, building gigantic sets so that the pageantry of his stories was supported visually. He made furniture and sets and costumes to delight the eyes of his audience, and he was clever enough to realize that such money spent brought double value—these things looked impressive in themselves but they also served as props for his adventure stunts. He always hired the best—the top-ranked directors, writers, designers—and he knew how to get good value out of them for his money, treating them to saunas and sleeping quarters at his mansion (Pickfair), and having his chauffeur drive them to work.

When you went to a Fairbanks picture, you often got more than one Doug Fairbanks. He was constantly donning disguises, assuming different walks and attitudes, undertaking masquerades. He liked to play two versions of the same character—old and young, effete and strong—and besides giving a marvelous performance, he did exciting stunts and acrobatics, anything physical he could think of to do. When all his character variations were supplemented by excellent supporting actors, beautiful leading ladies, superbly designed sets and costumes, lavish production values, solid writing and directing, he had a full house. And there were also imaginative and innovative tricks of cinematic technique to wow the audience even more.

Fairbanks put his knowledge of cinema to good use, coming up with a bag of sly visual tricks. He shortened the legs of a table he was going to jump over so that he would appear to soar. He could easily and swiftly whoosh down a hanging tapestry, because a slide had been built and concealed inside the fabric. He found just the right number of frames to use per minute in a sequence to give added pace and acceleration. Although he spent significant sums of money on clothes and props and sets, he tried never to hire a double. “Don’t cheat the audience of yourself” was one of his rules. (Cheat them the respectable way—through top-notch special effects.)

Above all, Fairbanks became a master of scale. When he leapt from the floor up onto a table, or from a window onto a tree trunk, he knew how to make the leap look more impressive than it actually was. By building huge sets, he made all his feats look bigger and grander than they were … although they were, in fact, pretty big and grand. His ideas were inherently cinematic and he used the medium in bold ways. For instance, in The Mollycoddle (1920), his character is put belowdecks on a ship to stoke the furnaces. Not used to such labor, he collapses from exhaustion. Suddenly, the audience is shown the other stoker as Fairbanks’s character would see him (in an imaginative point-of-view shot): the stoker with his shovel, the flaming furnace, the pile of coal—all revolve around in a circle, as if encased inside a drum.

If Doug Fairbanks had possessed only his athlete’s agility, a little humor about himself, and a strong business sense, he might never have become popular. But he had something else that every star must have: magnetism. When Fairbanks is on the screen, you don’t feel like looking at anyone else. He glows with good health and that oft-remarked-on energy. He commands attention. He is—quite simply—a likable fellow who’s very hard to resist.

The critics of his time, who were almost universally male, definitely could not resist him. They appreciated and loved Fairbanks. (Their affection is in stark contrast to their hatred of Rudolph Valentino.) The first significant criticism started to appear only in 1930, when the scholar Paul Rotha’s assessment of Fairbanks’s persona hinted at the limitations that were built into his work: “Fairbanks, one feels, realizes only too well that he is neither an artist nor an actor in the accepted understanding of the terms. He is on the contrary (and of this he is fully aware) a pure product of the medium of the cinema in which he seeks self expression … his rhythm, his graceful motion and perpetual movement … Fairbanks is essentially filmic … No other talent than his rhythm and his ever present sense of pantomime, except perhaps his superior idea of showmanship and overwhelming personality.”

One of the few to discuss his limitations seriously was Gavin Lambert, who, writing a full decade after Fairbanks’s death, said that “Fairbanks had the exuberance of the virtuoso, but there is no poetry in his movements, agility and vigor rather than grace. The Thief of Bagdad showed his feeling for the exotic to be ludicrously undeveloped.” (Fairbanks’s sense of “the exotic” was never sexual or decadent; it was fanciful and playful. On that basis, perhaps it is not exotic at all, but it certainly was well developed.) In fact, the primary appeal of Fairbanks lay in his quintessentially American, and therefore unthreatening, presence. He was closer to imaginary male heroes like Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy, the lads of Horatio Alger, or even the Lone Ranger, than he was to someone like Valentino, who was erotic, foreign, and sexually ambivalent. Fairbanks was a man’s man, and he stood for fair play, decent behavior, and rapidly evolving upward mobility.

FAIRBANKS WAS BORN Douglas Elton Thomas Ulman to Hezekiah Charles Ulman, a New York lawyer who was the son of a wealthy Pennsylvania family, and Ella Adelaide Marsh of New Orleans. Ulman had met his wife when he helped her settle her affairs after the sudden death of her first husband, John Fairbanks. (He then helped her obtain a divorce following a disastrous second marriage.) The couple settled in Denver, where the restless Ulman practiced law but also unsuccessfully tried his hand at gold mining. Two children were born, Robert in 1882, and Douglas in 1883. Five years later, Ulman disappeared and never came back, becoming yet another of the disappearing fathers who mark the lives of so many silent film stars. The bitter wife changed her name back to that of her first husband, Fairbanks, and Douglas never saw Ulman again except once when he showed up to cadge drink money after Douglas had become a successful stage star.

Fairbanks showed an interest in performing at an early age. A November 19, 1898, program for “Living Pictures,” a children’s matinee sponsored by the woman’s club and art leagues of Denver, names a “Master Douglas Fairbanks,” a pupil of the Tabor School of Acting, as presenting a “selected recitation.” In 1899, when he was just sixteen, Fairbanks went on tour with Frederic Warde’s famous Shakespeare company, and a year later, he was on Broadway. During the next fourteen years he established himself solidly as a leading man. In 1906, with his appearance in Man of the Hour, he officially became a star. By 1919, a theatrical journal referred to him as “generally regarded as the leading exponent of light boys and young men of today … He has an ingratiating personality, charged with health, directness, breeziness, and a certain patrician quality which contributes an attraction to any part he plays.”

In 1907, Fairbanks married Beth Sully, a stagestruck heiress, and he gave up theatre for a one-year period to work for her father’s soap company. (On December 9, 1909, the couple had a son, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., who would himself become a successful film and stage star.) Fairbanks did not like business, and returned to the stage, eventually being lured west to make movies by Harry Aitken of the Triangle Film Corporation, who also had under contract the Gish sisters, the Talmadge sisters, Bessie Love, and others, including the prize catch, the renowned stage actor Sir Herbert Beerbohm-Tree. Fairbanks made his film debut in Triangle’s The Lamb in 1915.

In this first feature—playing a starring role—he was directed by Christy Cabanne and costarred with Seena Owen in a story written by “Granville Warwick” (a pseudonym for D. W. Griffith). The question naturally arises—when The Lamb is shown today, does it look as if a star is being born? Definitely. Like Clara Bow and Valentino, who would come along later, Fairbanks stands out in the frame, causing those around him to pale by comparison. Unlike Bow and Valentino, however, Fairbanks had more than just his fabulous looks and the kind of vitality the camera responds to: he had stage presence, physical skills, and a solid comic ability. He plays a “son of the idle rich” who is “the lamb” of the title. The first sight of the soon-to-be star finds him looking perhaps a bit stocky but very fit and well dressed, giving a fully developed performance as a silly and somewhat fuddled young man. Flashing his million-dollar smile, Fairbanks seems totally at home within the frame, easily deploying his acrobatic skill to portray a physical bumbler who, though he can jump with ease over a hedge, has to take boxing lessons (with a “white hopeless”) and jujitsu instruction to become “manly.” Peppered with current slang and snappy one-liners (he’s going to get married and become a “lamb led to the halter”), The Lamb tells a rollicking tale of Fairbanks in one dilemma after another. On his way to Arizona, he gets rooked by Indian traders, left behind by his train, taken out into the desert to be robbed and dumped by crooks, and finally embroiled in a fight between Yaqui braves and Mexican bandits. Naturally, all ends well, as he rescues Owen and proves his mettle.

The Lamb set the pattern for Douglas Fairbanks’s early years as a star—he’s a resolutely cheerful go-getter, a kind of all-American guy who always comes out on top no matter what the odds. He’s almost a straightforward version of Harold Lloyd, but he plays his early comedies to emphasize excitement over laughs, whereas Lloyd stressed laughs over excitement. Both were masters of presenting young men who were faced with physical and social obstacles to overcome, and both represented the essential optimism of their era. Doug’s character in The Lamb starts out as a jerk, but he finds out, under duress, that he has good stuff in him and that, in fact, he secretly harbors the heart and soul of a hero. This idea—that ordinary people were really special if only life would give them a chance—was an idea that America was ready to embrace. His was the Zeitgeist of the optimistic post–World War I era, and no other star represents it as well as he does, both on- and off-screen.

Between 1915 and 1920 (when he released his first big costume film, The Mark of Zorro), Fairbanks appeared in twenty-nine movies. Except for The Half Breed (1916), which was purely a love story, all were about comedy, romance, and adventure. Sometimes it was romantic adventure, and sometimes it was romantic comedy, and sometimes it was comedy adventure. For instance, Arizona (1918) was a romantic drama set in the West, When the Clouds Roll By (1919) was an action romance, culminating in a huge flood sequence, and The Good Bad Man (1916) was a romance about a Robin Hood of the Old West. A Modern Musketeer (1918) was a fantasy-comedy, and The Man from Painted Post (1917) was a romantic comedy melodrama … the mix was slightly different from movie to movie, but the basic ingredient was always Doug Fairbanks doing his thing. At some point, he would scale a wall, climb a tree, jump off a building, sock the villain, and rescue the girl and save the day. It was an excellent formula which he executed to perfection, and with great joy and panache.

All these early comedies are peppy exercises in how Doug Fairbanks Can Solve His Problem. He charges through the plots, always seeming to be genuinely enjoying himself. Watching Fairbanks in these movies, it isn’t hard to see why he became so popular. He is the very definition of what makes a great film star: he and his screen character seem totally unified. It’s impossible not to believe that we aren’t watching Doug Fairbanks be himself. There is no distance between a film viewer and this character. Fairbanks, however, was not really playing himself, but a character he devised for himself. People could come to the movies and watch a good-looking young man having a great time up on the screen chasing and catching crooks, becoming rich and successful, winning the girl. How reassuring and how satisfying. And what fun!

Fairbanks himself described his second film, Double Trouble (1915), by saying, “In my second picture I ran a car off a cliff, had six rounds with a pro pugilist, jumped off an Atlantic liner, fought six gunmen at once and leapt off a speeding train.” Both The Lamb and Double Trouble were supervised by D. W. Griffith, but the artistry of Griffith and the exuberance of Fairbanks were not really compatible. Fairbanks said, “D. W. didn’t like my athletic tendencies. Or my spontaneous habit of jumping a fence or scaling a church at unexpected moments which were not in the script. Griffith told me to go to Keystone comedies.” (Both movies were Triangle features. Triangle’s creative force was Griffith, Thomas Ince, and Mack Sennett, the three producers who had each signed a contract to release a three-hour program every week.) At Triangle, the writing-directing team of John Emerson and Anita Loos was also unpopular with Griffith, who considered Loos’s titles altogether too snappy, so Loos and Emerson began working with Fairbanks. They were a highly effective trio, and they started right out with a hit, Fairbanks’s third movie, His Picture in the Papers (1916).

Fairbanks and D. W. Griffith (photo credit 3.1)

The Douglas Fairbanks movies of 1915–20 all have certain things in common: Doug, of course, looking handsome, suave, and bursting with energy; a very pretty girl who has relatively little to do; and a full-scale action sequence in which Doug performs acrobatics, stunts, and various forms of derring-do. Usually these films have more than a little comedy, and some are out-and-out spoofs or farces. The plots follow a pattern, basically, adding up to snappy entertainment with little depth. Seen today, they are endearing for their innocence and zest, for their boundless enthusiasm for the possibilities of life. The great thing about Douglas Fairbanks on film was that he not only conquered his world but also made it seem as if anyone could do the same.

In 1916 alone, he made eleven films, five of which involved either Emerson or Loos in some capacity. In His Picture in the Papers, he is the son of a health-food magnate, but he hates health food. He conceals the fixings for his cocktail shaker inside a box of Prindle’s Toasted Tootsies, and after a family vegetarian dinner, he dashes to the nearest restaurant for a bloody steak. The film’s opening title warns that “Publicity at any price has become the passion of the American people,” and Fairbanks is put to the test when he falls in love with a vegetarian’s daughter. (She, too, sneaks out for a little red meat now and then.) The girl’s father tells him that he cannot marry her unless he claims his rightful inheritance—half his father’s business. When he goes to his father, he’s told he can have the money only if he can publicize “Prindle’s 27 Vegetarian Varieties” by getting his picture in the papers. Thus a typical Fairbanks comedy dilemma is set up—he sets out to get publicity of any kind and can’t even get arrested. Nothing works. In the end, after much dashing about, he rescues a train and makes the grade. The little moral about the emergence of celebrity, and how ludicrous the concept of celebrity really is, gets lost in the rush, and everyone has a good time. (Variety liked what it saw in His Picture in the Papers, writing, “Douglas Fairbanks again forcibly brings to mind that he is destined to be one of the greatest favorites with the film-seeing public.”) In this early movie, the power of the Fairbanks personality is stunning. It’s also evident that he was playing in a somewhat superficial mode. This shows up again in Reggie Mixes In, also from 1916. Although he has real charm, he is clearly letting his good looks, strong body, and athletic ability carry his performance and stand for his character.

The timing and flow of the chase sequences that Fairbanks participates in for all these early movies are perfect, and it’s startling to realize how common such first-rate comedy action was in those years. Variety, for instance, stated flatly about Flirting With Fate (1916): “There is nothing unusual about the feature.” Today a sequence like the one that Fairbanks executes so easily would require stunt doubles (unless it involved Jackie Chan) and would be tarted up with explosions, fake camera angles, and computer assists. Fairbanks just steps out and does it. This chase is a particularly good one, and is the central action of the movie, which uses three reels to set up a plot and two reels to do nothing but run and chase. Fairbanks plays an unsuccessful artist who, dejected at the way his life is going, hires an assassin to sneak up on him and kill him. Suddenly, his luck changes. He sells a painting, gets the girl, and inherits a fortune! Now he’s got to evade his killer, but he has no idea what the guy is going to look like, since he has ordered the assassin to wear a disguise. (This plot is similar to Warren Beatty’s 1998 Bulworth.) Obviously, Fairbanks spends the rest of the movie running … from everyone. (I am highly partial to the assassin, who turns out to have a conscience and a dying mother. “Even assassins have mothers,” he weeps to the Salvation Army workers who reform him.) In the freewheeling chase, Fairbanks jumps up from the sidewalk onto a store balcony, jumps into the back of a fast-moving automobile, jumps from a moving car onto the back of a second one that drives up alongside, scampers over rooftops, and leaps up things and over things in a lumberyard. Despite Variety’s quibble about the chase being old hat (which it isn’t), the review praised him: “Mr. Fairbanks is a comedian first, last, and always.”

All the early Fairbanks chase scenes take place across actual landscapes and city streets—they’re inventive, well shot, and played out in the most natural yet sophisticated way possible. Two of the finest are in the 1916 releases Manhattan Madness and The Matrimaniac (one of the best of his titles). In Manhattan Madness, he assaults a mansion to rescue his girl. On location in an actual three-story house, Fairbanks climbs in and out of windows, clambers up to the rooftop, struggles with a villain, jumps off the roof into a tree and shimmies down it. The house has a wide eave at every floor, so that he and his adversaries can go in and out of windows, run around, and leap down from one eave to another in an amazing burst of action which the viewer can see is honestly dangerous. Fairbanks even climbs up this house from the ground floor … and the reward is all his. In the end, he sets his beautiful prize on a horse, and the two lovers gallop away to happiness.

Matrimaniac presents an elopement. Constance Talmadge and Fairbanks run away to be married, only to confront a series of disasters that separate them. He spends the entire remaining running time of the movie trying to get to the girl in time to marry her before her father catches up with them. With a justice of the peace in tow, he chases madly by train, car, reluctant mule, and on foot—all with both the police and Daddy in pursuit. It is a buoyant, joyous romp across logic and through time and space. Doug has to leap across buildings, climb trees, walk a tightrope, and tiptoe (literally) along a telephone wire.

Less fun, though successful, was The Americano (1916), a romantic adventure story set in “the little Republic of Paragonia” which is “hidden in a bend in the Caribbean.” Fairbanks plays a young mining engineer who falls in love with the president’s daughter (the languid Alma Rubens, looking as if she’s in a tragedy). He ends up rescuing her from an unwanted marriage and her father from death in prison at the hands of revolutionaries.

The eleven 1916 movies that made Fairbanks a household name had one bizarre entry among the titles. John Emerson directed Fairbanks in The Mystery of the Leaping Fish, taken from a story by Tod Browning. When modern audiences come across it, they’re usually astonished at its joking references to drugs, as Fairbanks plays “the world’s greatest scientific detective, Coke Ennyday.” Obviously intended as a satire on Sherlock Holmes and his 7 percent solution, the movie opens with Fairbanks sitting beside a large container clearly marked COCAINE, and he is repeatedly seen injecting himself. This may have seemed appropriate material for comedy in 1916, but it’s a bit unsettling today. The story itself is rather fevered, involving counterfeiters, Japanese opium dealers, and “the little fish blower of Short Beach,” the leading lady “Inane,” played by Bessie Love. Fairbanks ends up as a sort of human submarine, but there’s a visually imaginative use of large inflated fish, which swimmers use to ride the waves at the beach and the smugglers use to hide their drugs in.

Fairbanks’s string of hit movies continued with five releases in 1917, seven in 1918, and three in 1919. All these followed the established pattern. Four typical examples of the work in this period are Wild and Woolly and Reaching for the Moon (both in 1917), and His Majesty, the American and When the Clouds Roll By in 1919. Wild and Woolly is one of the favorite Fairbanks comedies with fans today. With a script by Anita Loos and direction by John Emerson, it is a completely wonderful spoof of westerns. (It is interesting to note that western movie conventions were firmly in place by 1917, probably based on dime-novel awareness, so that the traditional action could be spoofed with audience understanding and participation.) Once again Fairbanks plays the wealthy son of a tycoon (this time, a railroad baron), and once again he will be tested in a great finale of action, comedy, and excitement. He is first seen sitting beside a campfire outside a teepee, cooking his stew in an iron pot, wearing a large cowboy hat. As the camera slowly pulls back, it is revealed that he is in his own bedroom, which is decorated with guns, western gear, and drawings and paintings of the Old West. He is a romantic—dreaming of the glory of the Old West and firmly believing that his vision is exactly what it’s still like out there. When his father is offered the opportunity to build a railroad spur to a mining camp in Bitter Creek, Arizona, he sends his son to look into the situation. Meeting the camp representatives in New York, Fairbanks mistakenly thinks they’ve dressed up like “easterners” for their trip; and they understand that his vision of their modernized western town is a fantasy. In order to win the father’s support, the entire town decides to stage a real “western” for Fairbanks when he arrives. They dress in costumes, don guns, erect new signs, redecorate everything to make their town look like a western movie set. When Fairbanks arrives, they even start talking western talk: “Wish you’d a come last Thursday. Thar wasn’t a killin’ all day.” When their fake holdup goes awry because of some real crooks, Fairbanks, who has been practicing his western tricks by roping the butler back home, rises to the occasion. In a grand finale—with a bunch of Indians running across country on foot intercut with a gaggle of mothers with crying babies rushing around town—he executes a splendid crescendo of activity. The film has a witty ending. As Fairbanks leaves town, waving good-bye gamely to the little gal he fell for, a title says, “But wait a minute, this will never do! We can’t end a western romance without a wedding. Yet—after they’re married, where will they, shall they live? For Nell likes the east—and Jeff likes the west—so where are the twain to meet?” In a comic finale, Jeff and Nell come downstairs in their mansion, with two footmen standing by. They are dressed in classic English riding style, but when their front doors are opened, outside is a typical western street.

In Again, Out Again (1917), with Arline Pretty (photo credit 3.2)

He Comes Up Smiling: the perfect modern hero of 1918 (photo credit 3.3)

Reaching for the Moon demonstrates the classic silent-film-era format of “two for the price of one”—Fairbanks starts out as a button-factory worker and grows into the king of Vulgaria. Such transformations obviously appeal to the audience, who saw themselves similarly elevated, transported, or liberated, but they are also an extension of one of Fairbanks’s primary trademarks: movement. His ascents to glory were symbolized by his performing a stunt that looked unperformable for an ordinary person—a jumping up, as it were, out of poverty to wealth or from ineptness to agility—visualized as a leap from ground to tree branch.

Reaching for the Moon’s button maker is “a young man of boundless enthusiasm.” In other words, he is Doug Fairbanks. He yearns for wealth and royalty, but when he turns out to be the heir to a throne and is placed in a series of comic situations in which the forces of evil in Vulgaria try to murder him, he just keeps on surviving. (“Long live the king!” his subjects are always shouting, just as he once again narrowly escapes a would-be assassin.) Of course, his royalty in the end turns out to be that solid plot device of American movies and television—nothing but a dream. When he wakes up, he learns the movie’s moral—“Keep your feet on the ground and stop reaching for the moon”—and settles down in a little cottage in New Jersey: talk about keeping your feet on the ground! (This movie should not be confused with the sound film of the same title that Fairbanks made in 1931.)

The polish and confidence of the Fairbanks comedies reached its peak with the release His Majesty, the American. It’s a perfect title for the Fairbanks franchise: the elevation of an ordinary American go-get-’em guy to royal status. Audiences were treated with a special opening: Doug breaking through the titles to proclaim His Majesty, the American to be the very first picture to be brought to them by the newly formed United Artists. The movie presents Doug as yet another enterprising American loaded with energy and optimism. This time, he’s the millionaire version of his persona, a “Fire-eating, Speed-loving, Space-annihilating, Excitement-hunting Thrill Hound.” He spends his free time—which his wealth gives him plenty of—participating as a member of the police (capturing a criminal) and the fire department (he rescues helpless victims from a blazing tenement fire). Those colorful events, however, are only appetizers—later, he takes a trip to Mexico and gets involved with Pancho Villa. But the heart of the plot takes place in “Alaine,” an imaginary European kingdom, where “agitating demagogues have changed a peace-loving people into a rioting succession of mobs.” In order to straighten out Alaine—and find his secret destiny—Fairbanks runs up the sides of buildings, jumps around all over the place, and shows himself to be the most self-confident of performers, a star who knows what he has to offer the public and how to give it to them.

By the end of 1919, everyone loved the well-established Fairbanks comedy persona. The August 30, 1919, issue of Picture and Picturegoer defined it: “Doug is, perhaps, the type par excellence of the modern American—restless, dissatisfied, a little careless and fond of getting-there-quick, but cheerful, persevering, resourceful and clean.”

The Man from Painted Post (photo credit 3.4)

Mollycoddle (1920) and The Nut (1921) are like parentheses around The Mark of Zorro (1920), one released immediately before and one immediately after. They are his final comedies, the last hurrah of his original modern movie persona. Mollycoddle, as reviewed by Variety, is indeed “one peach of a picture.” Directed by Victor Fleming, the movie presents Fairbanks as the son of a succession of brave Americans, from a Revolutionary War hero to a pioneer to a cowboy, etc. However, the family has become rich, and this new generation’s representative has been raised abroad and is something of a “mollycoddle.” Doug’s given a perfect plot for undergoing one of his character changes. In the early scenes, in which he is the Europeanized American, he uses his excellent physical control to create a new walk, in which he bends slightly forward, sticks a cane under his arm, tightens up and tenses his body as if he were a bit of a stiff, a man out of shape and not entirely comfortable with his body. When confronted with the movie’s plot problems, in the shape of Wallace Beery as the seemingly grand “Van Halker,” who is really a diamond smuggler, Fairbanks rises to the challenge, and becomes loose, free and easy, full of fight. Beery mistakes Fairbanks for a Secret Service agent (who is actually the leading lady, played by Ruth Renick) and smuggles him aboard his yacht to America. Fairbanks performs the usual list of exciting acts, including being put overboard to drown, disguising himself as an Indian, falling off a mountain, and going over a waterfall. Mollycoddle is typical of the boisterous comedy years, a kind of summing up. It’s fun, fast-paced, and provides an opportunity for Doug to do his acrobatic stunts and act out a kind of Charles Atlas ad come to life.

The Nut was his final modern comedy, and it is a magnum opus, a fitting finale for the first phase of his work. He pulls out all the stops, and his comic play is a cross between Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times (several years before that film was made, of course) and Buster Keaton’s gadget-obsessed two-reelers. The opening sequence is one of his most original and best-sustained sight gags; his timing, excellent pantomiming, and mastery of physical shtick are beautifully combined. Fairbanks plays an inventor. (“He invented ways of pleasing his girl and then he invents ways of getting out of the trouble caused by his inventions.”) The first scene carries a title card that charmingly sets the tone of the movie: “Chapter I. In which we introduce our hero—” The audience is presented with a straightforward view of a set—there is a floor, a rug, two arched windows, a vase of flowers on a sill, a standing birdcage, with bird, and a bed. Lying facedown on the bed is a man who is sound asleep. Suddenly, a close-up of the bird shows a cartoonlike caption in which the bird is singing out, “Ten o’clock!” The man’s eyes fly open. Immediately, covers are raised off his body by a set of automatic strings that hoist them to some imaginary space above. The mattress section of his bed slides forward and is revealed to be on wheels. The sleeper is rapidly rolled forward to a sunken bathtub, with the bed conveniently upending itself at tub’s edge in order to slide him, pajamas and all, into the waiting water. In his bath, he removes his pajamas (revealing a heavily muscled back), and an automatic arm with three giant sponges attached begins to whirl and wash him. As he finishes his bath, he moves to the end of the tub and begins to get out of it. As his presumably naked body rises up out of the water, a large roll of towel on a spindle rises up in the foreground, neatly covering him. The roll, like the sponges, whirls around, drying him from head to toe, while he turns back and forth. Dry, he steps out from behind the protection of the spindle, but before we can see him, a title card cleverly interjects some information: “He isn’t lazy. He’s just different and eccentric—but then—so were Christopher Columbus—Sir Isaac Newton—Lydia Pinkham—and Ponzi.” When the card disappears, Fairbanks has miraculously progressed to a semidressed state. He is combing his hair and wearing an undershirt, shorts, black shoes, and socks and garters. He presses a switch, and a conveyor belt carries him toward a long closet marked by a series of panels that open automatically by sliding upward and then back down. The first panel opens and hands out a clean white shirt … the second a pair of pants. Another cleverly placed title card (“Maybe necessity is the mother of invention—but the father of these is a nut”) masks the progress of the dressing man. The next time we see him, he is tying his tie, then donning his jacket, and completing the effect with a pocket handkerchief. However, the first hanky that comes out he rejects—a neat little touch. It goes back in and a second choice emerges. In this excellent opening, Fairbanks and his team have understood that they are working a one-joke gag, and while it is inventive as it proceeds from bed to bath to closet, they must shorten the time presentation to keep the pace moving and the comedy fresh. By working with the audience’s desire to see Fairbanks emerge naked from his bath, they hold interest, but jump forward over a cut—a little joke on the audience. This is an example of Fairbanks’s brand of physical comedy. Granted, he’s not as skilled at moving the narrative smoothly forward or as inventive in his action as Keaton, nor is he as talented a pantomimist as Chaplin, but he’s good. And he’s a legitimate romantic leading man in a way neither Chaplin nor Keaton could ever be.

In The Nut, Fairbanks fully indulges his interest in movie special effects. In an extended sequence, the hero and the leading lady (Marguerite De La Motte) are shown climbing through the heating pipes of a house via trick photography. The audience is allowed to look through the walls, as it were, to see them climbing up and down inside the pipes and the furnace. There’s also an excellent scene in a wax museum in which he pretends to be a dummy; a routine with a wax “cop” he loses in the street; and a marvelous visual joke in which he performs for guests by impersonating Lincoln, Napoleon, and others, including Charlie Chaplin. Each time he goes behind a screen to transform himself into a historical person, another actor comes out who is short, or tall, or whatever the impersonation requires, with the grand climax being Chaplin himself in his surprise cameo. (It was probably no accident that Fairbanks’s character’s name in The Nut is “Charlie.” The two men were very close friends.) It was almost as if Fairbanks had stored up a bank of comedy routines and decided to use them all in The Nut.

The reviews that Fairbanks received for his comedies from 1915 to 1920 trace his rise and help define his popularity. As early as Reggie Mixes In, a Variety review pointed out that “D’Artagnan and other swashbuckling heroes were mere children alongside the physical prowess of Douglas Fairbanks in his latest Fine Arts Feature … Some scrapper that Doug Fairbanks. Jess Willard has nothin’ on him.” Matrimaniac was dubbed “a great picture for the Fairbanks fans … The picture will get the money.” The New York Times referred to The Americano as “a typical Douglas Fairbanks film, with the star as his irresistible, athletic self.” By the time of The Mollycoddle in 1920, reviews pay tribute to Fairbanks as the be-all and end-all of his movies, and to his contributions to the entire production: “One reason why the Douglas Fairbanks pictures hold their popularity is that Mr. Fairbanks does not depend entirely upon himself, nor upon a hackneyed story, to keep the public interested. In nearly all of his productions there are extraordinary scenes that could be shown in no way except by motion pictures and are conspicuously within the scope of the motion picture cameras.”

THE THIRTY COMEDY MOVIES are the films that made Fairbanks a star. When he expanded his movie universe into the swashbuckling films he is more readily identified with today, he was smart enough not to abandon his original successful persona: he simply took his comedy self and moved it to another part of town. With The Mark of Zorro, Fairbanks lifted his daring young man out of the ordinary and into history. It was not that the mythical kingdoms of some of his comedies (such as “Paragonia” and “Alaine”) were realistic, or that he was presenting a documentary approach to the West, or to daily life in the teens. His millionaires and playboys and enterprising button clerks were hardly the stuff of realism. But his comedies were connected directly to the daily life of people in the audience, and they had modern settings, however fanciful or decorated or embellished. With Zorro, Fairbanks went where he was always destined to go: into the realm of adventure fantasy, that particular place little boys long to inhabit. He took the well-cut suit of clothes off his hero and dressed him up in a hat with a feather, or an earring, or a set of Arabian Nights pantaloons, but he didn’t let go of the comedy. As Gavin Lambert put it, writing in Sequence in 1949, “He will be remembered as the only figure of his time to attempt a revival of the heroic spirit in popular terms. What was overlooked, perhaps, in the excitement of the moment, was that Fairbanks had to create an old fashioned world to contain his antics.” His great gift was understanding that these hammy macho men would be totally irritating if they weren’t ingratiatingly amusing. He knew that the swashbuckler must be fun—a kind of comedy character in costume—and that the audience must feel that, underneath, he is totally wise to himself.

All eight Fairbanks silent swashbucklers have in common excellent production values, exciting action, large doses of good-natured comedy, a dash of satire, and at the center, Douglas Fairbanks, who had already created his persona and was now about to create a genre. Before he became a movie star, Fairbanks spent more than fourteen years as a stage actor, and his theatrical instincts were strong. He knew how to make an entrance in the dramatic traditions of the stage. The Mark of Zorro, the first of the swashbucklers, opens inside a busy tavern on a rainy night. The patrons are discussing the dreaded Zorro, who has carved his trademark Z on the cheek of one of the hapless drinkers. Suddenly, the door swings open, revealing the darkness and the pounding rain outside. Out of the inky blackness, stepping slowly inside, comes a pair of boots protected from above by a gigantic black umbrella, slick with rain and shiny from the lights reflecting off it. All action stops. The audience watches intently: an umbrella and a pair of boots. When the umbrella is slowly, slowly lowered, we do not see the dashing Zorro, with his cape and sword, but instead his alter ego, the foppish Don Diego. It is very effective filmmaking, delivering the unexpected, but it also could have taken place on the proscenium-arch stage.

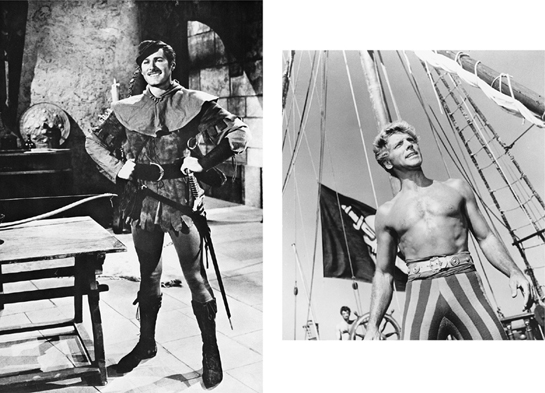

The disguised fop … (photo credit 3.5)

Zorro took the audience by storm. Everyone loved it, and critics raved. “Here is romance and into the bargain a commercial film,” said Variety, adding that “Douglas Fairbanks is once more the Doug that crowds love.” The New York Times added, “There’s no fault to find.” (However, in true critical tradition, the reviewer did find fault, pointing out that whereas the comedy films were lean and mean, Zorro’s action was slower to incorporate the more complex plot, the romance, and the beautiful scenery. It was also pointed out that the action was “tamer” because there were no mountain slides or floods.) The Mark of Zorro presented an extravagant Fairbanks, a larger-than-life figure, in keeping with the status he now occupied as a superstar. There were races, pursuits, entrances and exits, disappearances and reappearances, splendid quick changes, marvelous dueling scenes, and a fully developed romantic love story, pairing him once more with the beautiful Marguerite De La Motte. If The Mark of Zorro seemed tailor-made for Fairbanks, it was. Not only was it a United Artists/Douglas Fairbanks production, with him in total control of all aspects of production, but he wrote the script under his pseudonym, Elton Thomas. (Fairbanks had written scripts throughout his career, and all his adventure films, except Don Q, would be written by him. Elton Thomas was part of his real name, as he had been born Douglas Elton Thomas Ulman.)

… and the masked hero of The Mark of Zorro, with Marguerite De La Motte and Robert McKim (photo credit 3.6)

Off-screen, 1920 was the year Fairbanks married one of the few stars whose fame was even greater than his own—Mary Pickford. They were wed quietly on March 28, 1920, and it was probably the last moment of quiet they ever had except when they could hide out together in Pickfair. Fairbanks and Pickford were American royalty. By 1919, he had become the nation’s number one male box office attraction, and she was even bigger—the absolute number one of all stars, male or female. Their wedding—the marriage of two superstars—remains unprecedented in film history. (Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh were stars, but not nearly the equivalent of Fairbanks and Pickford, and that is also true of Bruce Willis and Demi Moore. Elizabeth Taylor was a superstar, but Burton wasn’t one when they wed, and never became one.) It is hard to imagine today what such a wedding meant to the media of 1920. Stardom was new to the world, celebrity was still an emerging concept. (When William S. Hart visited a camp of German prisoners of war and they called out his name, he was astonished … and more than a little upset.) Alistair Cooke assessed their union by saying, “Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford came to mean more than a couple of married film stars. They were a living proof of America’s chronic belief in happy endings.” At the time of their marriage, both were at the very top of their popularity and success, and the wealth they accumulated in the decade of the 1920s lifted them to the heights. They were the richest, the most famous, the most talented and successful, and the most physically beautiful and beloved of their era. Nothing like them had been seen before or really ever would be again. Their celebrity mattered; it wasn’t the fifteen-minute kind.

The fans’ couple, “Little Mary” and “Swashbuckling Hero,” and the couple in real life, suave Doug and chic Mary (photo credit 3.7)

After The Mark of Zorro, all of the Fairbanks silent movies were swashbucklers. His next was The Three Musketeers, and he, of course, played D’Artagnan. (In 1918, he had succeeded in a comedy called A Modern Musketeer, in which he played a young man who dreams of being D’Artagnan. It was a role that many had thought would be perfect for him.) In September 1921, the Variety review describes how a huge crowd had lined the sidewalks on both sides of the street outside the theatre for more than an hour in advance, because both Doug and Mary were to make a personal appearance at the opening. Unexpectedly, Charlie Chaplin and Jack Dempsey also appeared, and the mob went wild. The movie tickets, which cost an astonishing two dollars, were being scalped for as high as five, as people pushed and shoved to get inside. Fairbanks spoke before the film, during the intermission, and at the end—all at the insistence of the audience, who clamored to see him. The review was positive, saying that “Fairbanks and D’Artagnan are a happy combination, the character providing the star with what will probably go down in film lore as his best effort, for Fairbanks is just a modern bust of the mold of the Dumas hero.”

The Three Musketeers (photo credit 3.8)

It was clear from the success of Musketeers and Zorro that Douglas Fairbanks had found his perfect niche in portraying the romantic heroes of legend and literature. His next choice for a role was inevitable—the bandit of Sherwood Forest. With Robin Hood, in 1922, he moved toward a spectacle on the grandest scale … so much so that he almost outsmarted himself. Wilfred Buckland, the art director who created the huge castle set, reported that when Fairbanks first saw it, he was momentarily dismayed: “I can’t compete with that!” he cried. But, of course, he could—and did. The sets, the pageantry, the costuming added up to supreme movie grandeur, and the film had an enormous impact. But although everyone agrees that Robin Hood is spectacular, it may be the least appreciated of the eight adventure movies. Sometimes Fairbanks looks like a midget, hopping around on the huge sets, and there is a slight odor of Peter Pan. Critics of the day complained of a “slow first part” and declared it “a great production but not a great picture.” One critic nailed down the pageantry: “Where once he danced on air, Doug now stands on ceremony.” However, Robin Hood has a splendid cast and excellent direction (by Allan Dwan), and when the action starts moving in the second half, it takes off. The massive sets—the drawbridge, the castle, the convent, the banquet room—are all stunning, and the costumes, by Mitchell Leisen, are outstanding.

It was Leisen who made the enormous drapery that Fairbanks slid down in his most spectacular stunt in the movie. The drape was seventy feet long, and according to film historian David Chierichetti’s book Mitchell Leisen: Hollywood Director, “It hung from the top of the set and had to be carefully arranged to conceal the slide in back of it which was really how Doug got down. There was nowhere to buy any cloth that large. Mitch made it out of burlap and painted it himself to look like tapestry.” Leisen remarked that “Fairbanks was really … fascinated by the period and was very knowledgeable about everything in it. Once he got wound up in a project he couldn’t stop.”

A way of understanding Fairbanks’s appeal is to compare his Robin Hood to Errol Flynn’s. In the Fairbanks version, the star is introduced at the beginning of the film at a jousting tournament. He enters the frame dramatically, in the Fairbanks tradition, as a romantic medieval knight. A title card announces “The other contender for the championship—the favorite of King Richard—The Earl of Huntington, Douglas Fairbanks.” He moves into the frame wearing the armor of knighthood. His full-face helmet is lowered over his countenance, and over his head a huge white plume is flying. He pauses in the frame for a moment, obviously giving the audience a chance to observe him and think: “It’s Fairbanks!” Seen from his waist upward, his gloved hands on his hips, he surveys the scene through his helmet’s eyeholes. Suddenly his head begins to twitch, but he cannot reach inside the helmet with his large gauntlets. He pulls the elaborate headdress off, revealing the handsome, mustached face of Douglas Fairbanks; he then looks at his own reflection in the shiny armor of the cuffed gloves he wears, rubs his mustache, and laughs. It is a perfect blend of stagy drama, romantic costuming, and low-level physical humor. A storybook knight with an itch!

The Fairbanks Robin Hood stresses spectacle. The story line contains a fully developed Crusades sequence, and the first appearance of Fairbanks as the traditional Robin Hood appears well into the film. It, too, is a dramatic entrance, almost of a second character. In this sequence, his entrance is not announced by a title card but by a swiftly flying arrow that whizzes through the window of Prince John’s castle and pins a writ of capture for Robin Hood to the desk on which it is being scribed. At an open high window, Fairbanks is seen leaping onto the ledge, turning, and jumping down out of sight. When everyone in King John’s large hall turns to look, he is gone. Outside, a hand is shown, shaking a large vine to test its strength. Suddenly Robin Hood swings across the frame, and up onto the window ledge again. “Robin Hood!” cries out a servant, and he is seen laughing, dressed in the traditional garb associated with the character, carrying his bow and arrow and casually eating an apple. A marvelous action sequence follows in which Robin Hood romps through the king’s castle, leaping up and down, running up and down, and descending from a high parapet to the floor below via that famous and unbelievably long drapery. It is a passage of humor, robust athleticism, and dangerous action, and it gathers speed as it goes.

Errol Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) is enhanced by glorious color, natural settings, and one of movie history’s best musical scores, by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Flynn’s entrance is somewhat simpler. He is seen riding with Will Scarlet, moving into frame for the typical star close-up of the time. In the sequence that follows, he rides to the rescue of an ordinary Saxon who is being persecuted for having killed one of the king’s deer to feed his family. Flynn is already dressed as the genre’s typical Robin Hood, and this film contains no pageantry of knighthood or Crusades scenes. It’s as if everyone had watched the Fairbanks version and said, “Bag the knights. Keep the forest.” However, the action is all in the tradition of the Fairbanks mode: Flynn jumps up on tables, climbs up vines outside the castle, swings across the frame and poses atop a tree trunk. He does acrobatics and employs props in the same imaginative way Fairbanks does. He’s called “impudent” and “a bold rascal”—typical Fairbanks phrases. He puts his hands on his hips, smiles broadly, and brings humor and his own robust athleticism to the part. Flynn’s Robin is certainly as handsome as Fairbanks’s, and he wears a similar wig and an identical mustache.

Just as the Fairbanks influence on the costuming and makeup of the character is clearly felt, the Fairbanks influence on the acting style is there, too. Errol Flynn is himself a master of this type of role, and he is a big star in his own right. In no way does the shadow of Douglas Fairbanks diminish him; rather, he pays homage to it, showing how much Fairbanks has influenced the concept. The latter-day Robin Hood has shed the more old-fashioned, stilted aspect of the earlier film, and concentrated on the cheeky aspects of the character. The addition of sound allows for dialogue that modernizes the character, defusing anything out-of-date with snappy repartee. Furthermore, the addition to the story of a strong social conscience—much emphasis on the starving peasants—moves the story into the 1930s.

One of the most important aspects of the silent cinema is spectacle, and no film of Fairbanks’s presented a greater spectacle than The Thief of Bagdad, his magnum opus of 1924. Having dazzled audiences with his enormous sets for Robin Hood, he chose to outdo himself for his Arabian Nights movie. Working with William Cameron Menzies, Fairbanks oversaw the construction of a city with domes and minarets, a palace of enormous size, and tiny streets with archways, bridges, stairways, and passageways to nowhere that seem to rise up, up, and away into the very heavens themselves. It was a dream city out of a fairy tale, and was specifically designed to give the impression that it was floating over its own streets, a weightless universe of the imagination. The final touch was the Adventures of the Seven Moons sequence, in which trick photography and animation were put to ingenious use.

Fairbanks’s mastery of spectacle: the huge castle set of Robin Hood (photo credit 3.9)

The flying carpet of The Thief of Bagdad (with Julanne Johnston) (photo credit 3.10)

“Our hero,” Fairbanks was quoted as saying, “must be every young man of this age and any age who believes that happiness is a quantity that can be stolen, who is selfish, at odds with the world and rebellious toward conventions on which comfortable human relations are based.” And so Aladdin, the hero, becomes the kind of happy-go-lucky rogue that Fairbanks was so adept at embodying, a handsome young man who dares to dream and to fight for the hand of the fair caliph’s daughter even though he is not much more than a common thief. After he wins his fair maiden, they disappear into the heavens and the stars spell out a beautiful title that reads, “Happiness Must be Earned.” The movie—superbly directed by Raoul Walsh, and costarring Fairbanks with the lovely Julanne Johnston as the princess, Anna May Wong as the princess’s slave, and Snitz Edwards as his faithful companion—is a masterpiece of romantic fantasy, possibly the greatest Arabian Nights movie ever made (although the 1940 Technicolor remake, also called The Thief of Bagdad, and directed by Michael Powell, is a great movie as well).

On the one hand, The Thief of Bagdad is a movie you want to have seen as a kid, when its wonderful special effects can work their best magic. On the other hand, its magnificent design, its sophisticated sense of Arabian Nights fantasies, and its tongue-in-cheek star may best be appreciated by adults. In other words, it’s a film for all ages and for all decades. It’s a feast for the eyes, a humor-filled adventure story, and a great star vehicle.

The Thief of Bagdad opens on an extended action sequence featuring Fairbanks. Bare-chested, wearing gold hoop earrings and decorative pantaloons and sporting a handsome silver crescent-and-star design on his arm, Fairbanks looks tanned, muscular, and fit as a fiddle. He begins as if he’s asleep in the Bagdad city square, using the ruse to deftly pick the pockets of unwary citizens who stop to drink from the fountain he rests above. As they bend down to drink, he lightly lifts their money purses, then starts to move about, pantomiming in a broad and exaggerated style that is not just about silent film but about fantasy. Fairbanks is a beautiful man with a beautiful body, and he also exudes an amazing life force. Everything he does is fluid and graceful, and as he discovers a magic rope that can be thrown up into the air and climbed, he easily pilfers it, moving on to such activities as rolling under a wealthy woman’s carriage and hanging there until her hand, adorned with rings, droops down out of the vehicle. He then cleverly removes one of her rings and easily rolls off and away again. There’s always a new, somewhat comical piece of dashing action. He twirls about, flashes his grin, and lifts his arms joyously—it’s a magnificent dance of pantomimed action, almost a musical number or a brief ballet. At this point in his career he is forty-one years old, yet he looks youthful and performs energetically. There is no need for the audience to suspend disbelief as they watch an “older” star pretending to be young. Doug is young, boisterously so.

The scale of the objects gives the movie an impressive look—gigantic drums, huge oil jars, tall stairways, and high windows. Everything is enormous, with walls that dwarf Fairbanks, though he can still leap over them or climb them with the aid of his magic rope. Everything in the film is visually sumptuous yet modern in its stark settings, which emphasize interiors of great luxury set inside beautiful white spaces. The parade of thrilling effects is endless—from the wonderful processions of merchants and princes bearing gifts to the grand moment when Fairbanks becomes “invisible” inside a small triangle of movement. It’s all fresh and funny and stunningly beautiful.

Science and Invention magazine of May 1924 carried a two-page layout on “The Mechanical Marvels of ‘The Thief of Bagdad,’ ” pointing out how effective Fairbanks is in creating an illusion that takes away from the audience the easy explanation of the effect. For instance, the film presents “the magic rope” that miraculously rises into the air where it hangs suspended so Doug can climb up it. There is no support visible to the naked eye. The viewer immediately decides there’s a wire at the top of the rope that can’t be seen. Knowing this, Doug has his character hang on the rope and bend the top of it over, effectively demonstrating that there’s no wire attached. Of course, there really is a wire, and a property man to pull up the rope, and a clever use of photography to conceal what is manipulating the rope from above.

Thief of Bagdad also contains a “flying carpet”—on a wooden frame supported by steel piano wires—which was photographed against a black background so the film could be reexposed to show clouds painted on a rolling canvas fly by. To complete the effect, a large fan blew the fringe on the carpet edge to give a sense of motion. There is also “the cloak of invisibility,” “the flying horse,” a “magic chest,” and a highly effective monster. All these superb effects make the story magical, and they rely on the most innovative techniques, such as the use of black backgrounds, stop-motion photography, glass paintings, treadmills, wind machines, and double exposures. When you went to a Fairbanks film, you got your money’s worth. And as the years went by, he increased the ante, never settling for what he had done before but always pushing to create a greater illusion and a more entertaining film.

In Don Q, Son of Zorro (1925), Fairbanks dares to do the Valentino tango. It’s interesting to compare the two superstars and their versions of the Argentine dance, which is seldom seen anywhere outside a movie theatre. As Don Q, Fairbanks goes out on the town in Old Spain with some pals, visiting a dive, where they encounter a lovely woman dancing alone. Fairbanks joins her, and they tango wildly, energetically, and his tango is very, very good. He is extremely graceful, and has his entire body totally under masterful physical control, one of the primary requisites for the tango. But where Valentino’s dance is sexy and clearly focused on seducing the woman, Fairbanks’s is really not sexy at all. If it is sex, it’s that of two sixth graders whose idea of it is knocking each other around, each one more focused on self than on the other. Fairbanks’s interest in the woman barely exists. Where Valentino drew his woman closer and closer, bending her backward, looking deep into her eyes, pressing his body into hers, Fairbanks eventually ditches his woman to jump up on the table several times to do a solo set of masculine kicks and spins and jumps. The woman is a prop, not an object for seduction. Valentino’s dance is clearly only a prelude to a later, more satisfying physical action. In fact, both tangos are a prelude to a later physical action, but with Valentino, the postlude is never shown, only implied, as the point is to let the women in the audience (and/or the men) imagine it for themselves, later when they are at home, with themselves playing the partner. For Fairbanks, the dance is an introduction to an extended and highly imaginative action scene which becomes the on-screen release or postlude. He has to fight his way out of the bodega after the villain locks him in. The ingenious way he escapes—swinging on chandeliers, leaping through windows, tumbling out doorways, and dueling his head off—is a perfect release.

Son of Zorro is one of the best of the Fairbanks swashbucklers. It’s funny, lively, and exciting—full of satisfying title cards that say things like “For two pins, I would twist your nose!” The love interest is the exquisitely beautiful young Mary Astor, and two excellent character actors provide support: Jean Hersholt as a secondary villain, and Donald Crisp (who also directed) as the primary villain, Don Sebastian. Fairbanks’s sister-in-law, Lottie Pickford Forrest, plays Don Q’s servant girl, Lola, and Warner Oland plays the archduke. “It is Fairbanks as the public wants Fairbanks” and “designed for the Fairbanks fan,” said Variety.

Fairbanks handles the whip, Don Q’s main prop and weapon, with great aplomb, even flicking it into a burning fireplace to pluck a tiny spark with which to light his cigar. The action scenes, especially those involving the escape from the bodega and the capture of a mad bull, are extremely well presented. When Fairbanks is accused of murdering the archduke at the queen’s ball, he leaps up onto the sill of an open window, shouts, “My father always said, ‘When life plays you a trick, make it a trick for a trick,’ ” and pretends to stab himself to death, falling backward out of the large window, which is located high, high above a dangerously rushing river. (Of course, he lives.)

Fairbanks as Don Q has his hideout in the ruins of an old castle, complete with trapdoor, and all the settings are carefully designed and beautifully photographed. One of the high points of the movie is a scene that returns the audience to Old California so they can see the original Zorro, now an old man. He remembers how he threw his sword up into the ceiling “until he would need it again.” The movie then flashes back to a scene from the original movie, The Mark of Zorro, to show this happening. Upon returning to the present, the movie shows the old man pulling down the sword and going to help his son. As the two Zorros—and the two Fairbankses—fight side by side, with the father carving a Z on the cheek of the villain, it’s a great moment of a kind that comes along all too seldom: one in which the romance of an old movie is evoked to enhance another movie in which the same actor is still alive and kicking and on top of his form. (In 1926, Valentino would do a similar turn in The Son of the Sheik, playing both the title character and his father—the original from The Sheik—with a scene from the earlier movie included.)

By the time of The Black Pirate in 1926, the world was eagerly awaiting the next Fairbanks adventure. The ads screamed out the news, “Only Douglas Fairbanks could make such a picture … in glorious natural colors (Technicolor Photography).” Illustrated with beautiful photographs and drawings, the copy referred to “the rollicking zest of Doug himself!” and added, “Here is a film that will fill your lungs with the adventurous air of Pirate Days.” And, in fact, The Black Pirate went all out, and it is a particular favorite of many of Fairbanks’s loyal fans. Perhaps the most common image people have of Douglas Fairbanks today is his character from The Black Pirate. It is an especially dashing Fairbanks, with a head of thick, black, curly hair, an earring, short pants, a torn shirt, and seven-league boots turned over at the top into cuffs—all, of course, in darkest black. He is first seen standing on a ship’s rail, fists on hips and throwing back his head to give a hearty laugh that allows him to flash his beautiful teeth.

The Black Pirate is greatly enhanced by its beautiful Technicolor photography (which Variety complained about, saying it’s good the running time is short “so that the eye strain doesn’t become too trying”). It has what reviews called “a corking underwater effect,” in which pirates sneak up on a ship. The underwater photography sequences were spectacular in their day, and are still highly effective. Fairbanks looks terrific in The Black Pirate, but he is beginning to pose more than perform, and a highly romantic, exaggerated style of acting is beginning to dominate his work. Where once he was natural and his hands-on-hips, big-grin routine looked fun and cocky, it all begins to seem like posturing. Yet he is still his old amazing self, especially when he executes a grand stunt in which he slides down a ship’s sail. He mounts to the cross-arms of the ship, pierces the white sail with his sharp sword, grabs the hilt, and plummets to the deck, the force of the descent tempered by the sword’s ripping of the canvas as he moves downward. (It’s not unlike his slide down the curtain in Robin Hood but is even more spectacular.) This effect is so good it’s repeated, and when the smiling and dashing image of the handsome Fairbanks performs it, it becomes not just spectacular but utterly memorable.

The Black Pirate was a huge hit, receiving both critical raves and box office patronage. Variety asked a good question, after complaining that the story was little more than an excuse for the action, as to why, if he wanted to make a pirate story, he didn’t use Captain Blood, the famous novel by Rafael Sabatini? That pirate story, said Variety, “was a Fairbanks set up if there ever was one.” (The young Errol Flynn would make his first big hit as the hero of Captain Blood in 1935.)

The Black Pirate, with Billie Dove (photo credit 3.11)

The Gaucho (1927) is the film that fans like least of the Fairbanks swashbucklers. This is no doubt due to a maudlin religious motif that crowds in on the action, and from time to time the action is stretched to a point that’s almost self-satirizing, as when an actual house is moved forward off its base by a string of a hundred horses—an elaborate plot setup that is barely worth it. The Gaucho opens with “a miracle” involving a small girl falling into a canyon. Her life is saved by the Virgin Mary, who appears in a vision and brings her back to life.* After this sequence, as Variety reported, “Doug Fairbanks is at it again.” He is indeed “at it again” with the usual acrobatics and spectacular scenes, including one in which cattle are stampeded, a real pip. Doug does his usual hop-skip-and-a-jump stuff, looking tanned and fit and very self-confident about what he is up to. The word “dashing” was invented for Fairbanks. In The Gaucho he dashes here, he dashes there, and he manages to turn the entire world of the movie into a kind of gymnasium for his stunts. What is different about The Gaucho is the leading lady. No longer a pure virgin, a damsel in distress who needs rescuing (there is one of those, but she’s not the Fairbanks love interest), this “mountain girl” is played by the fiery Lupe Velez. Her character is a definite departure for a female role in a Fairbanks movie—she plays a true hero. After betraying Fairbanks because she thinks he is leaving her for another woman (the grown-up “miracle” girl, who is actually busily helping him cure himself of leprosy by teaching him to pray—you can see why this movie is no one’s favorite), she rides to save him by alerting his band of men. She then beats up on his chief enemy, jumping him from a rock above, punching him repeatedly, pounding him into the ground, and winning the fight. Velez acts with her elbows, the apparent source of all her emotional response, but she looks fabulous—radiant with sexual tension and lush in her appeal. She acts out a female role that is a feminine version of Douglas Fairbanks, as she leaps around, matching him dido for dido. They also play out a sort of Petruchio/Kate match at a banquet, arguing, shoving, and bonking each other like a madcap variation on the Liz Taylor/Dick Burton version of The Taming of the Shrew. (Velez earned excellent reviews, such as “This baby goes over … She scores 100% plus … a beauty … a great sense of comedy value to go with her athletic prowess.”)

The Gaucho, with Lupe Velez (photo credit 3.12)

The last Fairbanks epic adventure was The Iron Mask (1929), directed by Allan Dwan, who was quoted years later as saying, “Doug seemed to be under some sort of compulsion to make this picture one of his best productions. He has always meticulously supervised every detail of his pictures, but in this one I think he eclipsed himself. It was as if he knew this was his swan song.” There were two reasons why Fairbanks might, indeed, have known The Iron Mask would be his silent-film-hero swan song: first of all, he was forty-six years old when he made it, and secondly, sound had taken over the industry. Whatever he may have felt, Fairbanks gave The Iron Mask everything he had. Once again, he wrote the story under his pseudonym, Elton Thomas, creating the screenplay out of two of Dumas’s novels, The Three Musketeers and The Man in the Iron Mask. And he assembled a wonderful cast, with Belle Bennett as the queen mother, the lovely Marguerite De La Motte as Constance, Rolfe Sedan as Louis XIII, and himself, of course, as D’Artagnan.

Fairbanks’s silent farewell, The Iron Mask (photo credit 3.13)

Fairbanks very much treated the movie as a sequel to the 1921 Three Musketeers. Critics loved it, saying, “photography and titling top grade,” “enjoyable screen material,” “a lilt and verve to his D’Artagnan,” and “a role which fits [him] like a glove.” The movie was advertised with the announcement that the star would TALK, although it didn’t say how much. Fairbanks’s voice was heard only in a minute and a half of prologues for the first and second halves of the picture. There was no dialogue at all in direct action, but the movie had a great many sound effects and a suitable score especially composed by Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld.

The Iron Mask has a great deal to recommend it. In particular, the early love scene between Constance and D’Artagnan is excellent. Constance is leaving to go to the palace, and D’Artagnan tries to find a private place in which to kiss her. He leaps gracefully upon a wall, swinging her effortlessly up by one arm, continuing the action over the wall as he leaps down with her to the other side. They then run here, run there, but everywhere they go they are spotted. Finally, in a hidden garden, they believe themselves to be alone at last, only to look up and see a washerwoman grinning down at them from the wall above. However, she turns out to be a helpful ally, dropping her wicker wash basket to cover their heads so they may kiss inside it. The audience can see only De La Motte’s little hand moving to embrace Fairbanks … until they finally stagger back out from under with De La Motte wiping her brow. It’s a charming scene, well handled by both players, who strike the right note of playful fun, innocence, and sex to make it interesting.

Perhaps the most famous example of Fairbanks’s theatrical flair is The Iron Mask’s finale. Seen today, it feels like an epitaph for his career. Fairbanks, playing a now-aged D’Artagnan, has returned to save the good king from his iron mask by mortally wounding the bad king. As everyone celebrates, he walks outside alone, reaching upward toward the open sky. The image of his three dead musketeer companions is superimposed above him, beckoning him to come up and join them. As he once again leaps “up,” the four of them are seen again as young, vigorous, and happy. It’s one of the last hurrahs of silent action and certainly the last great hurrah of Douglas Fairbanks. “Only think! And we live again!” they cry out to viewers. It can’t help but tug at a movie-lover’s heart.

THERE IS SOMETHING grand, something majestic, in these Fairbanks romantic costume films. They are beyond. They go to exotic locales, dress people in fantastical costumes, make everything bigger. Where a grand stairway leading from the city plaza up into the cathedral might logically be two flights of stairs, it becomes four. Where a tall ceiling might be twelve feet, it is built at twenty-four feet. Where a hero running up the trunk of a palm tree would be impressive at twenty feet, Fairbanks runs forty feet. Bigger. Grander. Beyond. And the acting styles have to match or the actors would be dwarfed. A Fairbanks picture is partly about size, which is partly about abundance, which is partly about excess, which is partly about America.

The tragedy, if there is one in a career that is such a huge success, is that time ran out. Not only did sound render the Fairbanks type of romantic adventure temporarily old-fashioned, but he himself aged past the point at which such roles felt right for him. The wonderful illusions he presented, and the escapist world of pirates and thieves and swashbucklers, passed over into the world of tough-talking gangsters, a new kind of western hero, and a more disillusioned audience.

After The Iron Mask, things came unglued. It was not that Fairbanks lost his money or his reputation or even his status as a beloved star. But things came to an end. (His storybook marriage to Mary Pickford was over in 1936, his career dead two years earlier.) His sound debut was swiftly made in 1929, following The Iron Mask, and it was an appearance costarring with Pickford in The Taming of the Shrew. His years as a stage actor prepared him for sound, and he had a good voice and could handle dialogue. But somehow the new medium wasn’t right for him, and he made only four more movies. In 1931 there was Reaching for the Moon (a modern romantic comedy with music) and Around the World in 80 Minutes, a comedy travelogue. In 1932 he made only Mr. Robinson Crusoe, a romantic comedy melodrama, and in 1934 he made his final screen appearance in the kind of feature his audiences loved, The Private Life of Don Juan, a costume drama about a man who falls in love with his own wife. Unfortunately, the title was a bit too prophetic—rumors of dalliances emerged and after he and Pickford divorced, he married Lady Sylvia Ashley, whom he had met while filming his final movie in London.

Fairbanks and Pickford in their only screen pairing, The Taming of the Shrew (photo credit 3.14)