ONCE UPON A TIME in the movies, women walked in beauty like the night, trailing behind them—well, whatever. Usually a lot of yardage trimmed in fur. During the silent film era, the concept of woman as an object of great beauty, great mystery, and great outfits was commonplace. Once the motion picture was invented, it gave men and women a place to sit in the dark and have secret thoughts and secret experiences. Movies freed the mind if not the self, presenting their audiences with new opportunities for turning both men and women into sex objects. Sometimes both sexes were wholesome and lovable, and sometimes they were pure and virginal, and sometimes they were “ordinary” and “believable”—and then, sometimes, they were wildly peculiar, living in strange places and walking around in clothes never seen anywhere on the globe in any possible situation. They were exotic. This explains how we watch Gloria Swanson, a lively and cute young girl, turn into an actress who stands about with a long cigarette holder, wearing what appears to be a lampshade on her head. She had become exotic. “Exotic” didn’t mean that a heroine wouldn’t fall in love, or suffer, or dance the waltz. It didn’t mean she couldn’t live in the United States of America, either. It didn’t mean she couldn’t get married and settle down, be a mother, or preside at a dinner table. It meant that she wasn’t commonplace. She was the Other. She wasn’t going to be washing dishes, and she wasn’t going to be explained. She was desirable, even dangerous (the vamp was an exotic), but above all, she was about physical things. Her looks. Her figure. Her hairdo. Her wardrobe. It was a type that cried out for one of its later representatives, Hedy Lamarr, the perfect exotic. Too beautiful to be imagined, with thick black hair, alabaster white skin, full luscious lips, wide sparkling eyes, and a slender figure, Lamarr had an authentic foreign accent to lend credibility to her status. She was born to stand around, and she wore a turban better than anyone in the history of the cinema.

The silent era defined the type, and from the very beginning there were many exotics, the most famous early one being the highly original Theda Bara. Born Theodosia Goodman in Cincinnati, she found stardom in 1915 playing in the accurately named A Fool There Was. The name Theda Bara was said to be an anagram for “Arab death,” and since her role in the film was based on Kipling’s “The Vampire,” the jazzed-up label of “vamp” soon stuck to her.

Some of the most beautiful of these women were Barbara LaMarr (called “too beautiful to live” and not to be confused with Hedy), Valeska Suratt, Louise Glaum, and Alma Rubens—all names barely known today, and for a good reason: an exotic beauty was good to look at, but after a while, she wasn’t all that interesting. The careers of Bara, Glaum, LaMarr, and the others didn’t last long, because men got tired of looking at them and women felt no connection to them. Around 1915, however, two women got their movie careers going who really knew what to do about that last problem—Gloria Swanson and Pola Negri. Swanson and Negri knew how to be exotic in ways that made it last: first, they connected their strangeness to the ordinary woman in the audience by translating it into a form of pseudoliberation; and second, they started playing the role off-screen as well as on. They were exotics who became divas, and, more importantly, they came to represent “the modern woman.” They played good women and bad, in contemporary settings and historical ones, in comedy and drama, but they played their roles to the hilt and took them home with them at night.

Swanson and Negri were on their own very early in their lives, and when they came into the new art form of motion pictures, they seemed to understand instinctively that, despite the glamour and the fame, the movies were nothing more than a business. So they became businesswomen whose business was performance. On-screen, Swanson played a modern woman who was independent and/or who questioned the traditional value system that victimized women, while Negri challenged the old sexual double standard. Off-screen, Swanson played it straight. She was outspoken and shockingly frank, knocking everyone over with her liberated ideas. Negri went for the European version: “I-am-a-passionate-artiste-and-thus-might-just-go-mad-and-do-anything.” They combined their movie roles with colorful off-screen antics. They married royalty, demanded extravagant salaries, conducted a famous feud with each other, had affairs with such men as Joseph Kennedy (Swanson) and Rudolph Valentino (Negri), and gave outrageous quotes to the fan magazines. Ambitious, talented, and smart, they became a form of surrogate escape for American women, who followed their every move and checked out their every hat. They were so very convincing that today people confuse their crazy publicity with who they really were, which is unfortunate because who they really were matters. They were modern women, career pioneers who lived liberated lives. They were women of the world.

Gloria Swanson is yet another of those dinky little women who became great silent film stars. Only four feet eleven inches tall, she managed to strut across the screen in outfits that would have overwhelmed many a larger leading lady. I’ll say this for her: she may have been short, but she acted tall. (And she knew the difference, once saying to a fan who had gushed about “finally meeting” her, “And I bet you were surprised at what a sawed-off little shrimp I really am.”) Like all silent film stars, Swanson knew how to use her entire body. Mary Astor, in her autobiography, described Swanson as having “expressive shoulders,” an astute observation from a rival actress. Swanson always made the most of everything she had, and this drive and determination turned her into one of the very biggest stars of the silent era.

She was born Gloria Josephine May Swanson on March 27, 1898 (she said 1899), in Chicago, an only child whose father, a military man, moved his family around frequently. She made her debut in movies in 1915 at Essenay in Chicago and very soon came out to Hollywood and signed with Mack Sennett to play in two-reelers at Keystone. Since she posed for publicity stills at Sennett wearing one of the typical bathing girl costumes of the day, Swanson was often said to have been one of Sennett’s Bathing Beauties. This she denied vehemently all her life, in almost every interview she gave as well as in her excellent autobiography, Swanson on Swanson (published in 1980). Since she had been a featured player with Sennett, she felt demeaned by the idea that she had been just another pretty face among a troop of bathing beauties. She had acting experience before ever arriving at Sennett. Her Essenay roles in 1915 had included The Fable of Elvira and Farina and the Meal Ticket (said to be her debut), in which she plays a young girl with social aspirations; Sweedie Goes to College (opposite her future husband Wallace Beery—he plays a big Swedish maid and she plays a deb in a girls’ dormitory); The Romance of an American Duchess (she has the title role, perhaps her first moment on-screen in the kind of glamorous roles she would later make famous); and The Broken Pledge (as one of a trio of young girls who vow to become old maids until a camping trip—and three good-looking guys—change their minds).

Swanson’s first Sennett-Keystone movie was A Dash of Courage (1916), and after that she was in a series of comedy two-reelers with names like Hearts and Sparks, Love on Skates, and Haystacks and Steeples, all in 1916. Her best-known comedy from this period is the likable Teddy at the Throttle (1917), in which she costars with Bobby Vernon, Beery, and Teddy, the famous dog star of the Sennett menagerie. (Swanson had married Beery in 1916, but the marriage lasted only a month, although they didn’t officially divorce until three years later.) Teddy at the Throttle is a terrific comedy in the Sennett tradition, with a slam-bang story of skulduggery in which Beery ties Swanson to the railroad tracks and Teddy has to save the day by jumping up and taking over the throttle, stopping the train just in time to rescue Gloria. Swanson is lively and animated in this film, a respectable rival to Sennett’s great star comedienne, Mabel Normand, and appears totally unrelated to the staid clotheshorse she would become in just two years.

Gloria Swanson, under contract for Sennett, posing at the beach. The actress pulling the boat ashore is sometimes identified as Phyllis Haver, sometimes as Marie Prevost. (photo credit 6.1)

A lesser-known film from the same year, The Pullman Bride, paired her with the comedy greats Chester Conklin and Mack Swain in a romp that takes place largely on a speeding train. Swanson is exceptionally pretty, and her little well-dressed body seems almost detached from the chaos of the action. She looks surprisingly modern, in a smartly cut suit and flower-bedecked hat. As the action unfolds (the film is wild, charmingly vulgar, and really funny), Swanson is like a calmer, less physical version of Normand, maintaining perfect comic consistency in her part as the unhappy, slightly reluctant bride. She takes her falls—most notably an amazing backward drop that she does without hesitation, falling flat, her body like a stiff board—but she holds down her role, which is that of the comedy ingenue lead. Swanson already has that charisma that great stars all exhibit in their earliest work. You can’t help looking at her, and not just because you know she’s Gloria Swanson. Even in her earliest years, and with less of the comedy action belonging to her, Swanson makes her mark.

In later interviews, Swanson said, “I hated comedy, because I thought it was ruining my chance for dramatic parts. I didn’t realize that comedy is the highest expression of the theatrical art and the best training in the world for other roles … The mark of an accomplished actor is timing, and it can be acquired only in comedy … Comedy makes you think faster, and after Keystone I was a human lightning conductor.” At the time, however, she wanted to be more like the emerging Norma Talmadge, so she left Sennett and moved to Triangle Studios, making her first film there in 1918, Society for Sale, directed by Frank Borzage and costarring her with William Desmond. She went on to make a group of movies with typical titles of the time: Her Decision, You Can’t Believe Everything, Every Woman’s Husband, Station Content, Secret Code, and Wife or Country—all in 1918. Her other Triangle release of the year was Shifting Sands, which represents her work of this period very well. It has a twisted plot stuffed with events that swamp the poor heroine. First she’s a slum girl trying to earn a living painting (though she has no talent). Then she’s attacked by the rent collector when she can’t pay, and refuses to give him her “favors” in exchange. After dropping his wallet as they struggle, he comes back to arrest her for the theft. She goes to prison, and comes out with a baby! (Who knew?) After she gives this child up to the Salvation Army, they hire her, and the next thing you know she’s married a very rich young man because, as we all know, very rich young men frequent Salvation Army headquarters. (Actually, he invites her to his estate, telling her to bring the poor kiddies she takes care of for a picnic.) As a rich wife, she looks lovely in white organdy with a satin bow, but good clothes do not put an end to her troubles. Counterfeiters turn up to blackmail her (some accounts say German spies but they were counterfeiters in the version I saw). All mercifully ends well, but a modern audience might question Swanson’s judgment, wanting to play in junk like this instead of the delightful Sennett comedies.

Her performance style in these 1918 films is restrained and subtle, sensibly underplayed. She can’t summon up the radiant suffering of a Lillian Gish or the passionate histrionics of a Negri, but she’s very appealing. She seems to have a kind of real American honesty—plain and simple, straightforward and direct. Variety paid her tribute, saying, “Miss Swanson gets all she can out of the part.” Precisely. Swanson elevated herself out of the slapstick world of Mack Sennett by participating in these less-than-stellar movies. Her next goal was to take another step up the ladder of success by finding some good serious material, and it didn’t take her long; the next rung was waiting. In 1919, she left Triangle to make her first movie with Cecil B. DeMille at Artcraft (which released its movies through Paramount). DeMille was already a big name, and coming under his aegis was a giant step for a young actress like Swanson, who had only four years of moviemaking experience behind her. Yet she didn’t come to DeMille empty-handed; from her slapstick years, she had learned timing and professionalism. At Triangle, she had found two kinds of roles for herself—the poor working girl who rises and the bored society woman who has to learn a moral lesson. Swanson was ready for her DeMille close-up. Furthermore, she had driving ambition and a willingness to work herself to death. And she had something that DeMille certainly noticed—she was a very beautiful young woman.

Swanson in her Keystone years: Teddy at the Throttle … (photo credit 6.2)

Today it’s often said that DeMille discovered Swanson and developed her into a star. The truth is more complicated, in that Swanson had already played leading roles. She hadn’t, however, become a name, and she had no real persona of her own. It was DeMille who found the Swanson definition. In their six films together from 1919 to 1921, he turned her into a symbol of a particularly new kind of American woman: sophisticated, soignée, and definitely not a virgin. Although young, this woman was married, so she already knew about the birds and the bees. She was rich, magnificently and luxuriously dressed, with jewelry to knock ’em dead in Peoria. She was not to be found sitting home by the fireside; she was out in the world, ready for something to happen, riding in fast cars, shopping, dancing, smoking, doing pretty much whatever she felt like. One thing was certain—she was meeting lots of men. There was no implication that she was wicked, or promiscuous, but she was out there, and thus possibly available. There was a sense that anything could happen to her—and in the DeMille plots, it did. There was also the sense that the Gloria Swanson woman might even think for herself, no doubt a thrilling idea for her female fans.

… and a typical 1917 release (photo credit 6.3)

With DeMille, Swanson’s career took off. DeMille appreciated her style, and he knew she had that extra something that stars must have. He said that one of the first things he noticed about her was “the way she leaned against a door … She showed complete poise, repose and grace.” Their first film together, in 1919, was Don’t Change Your Husband (advice she herself ignored). In this cautionary tale, Swanson plays a dutiful wife who has to ask permission from her husband to buy a new dress. Granted, the dress is a haute couture frock made of pure silk and dusted with precious beading, but still … why should a woman have to suffer like that? In all the DeMille films, Swanson is awash in the world of fashion but also trapped in a world dominated by husbands, most of whom don’t have a clue. The main events in the lives of the Swanson women are Fashion and Husbands, Husbands and Fashion, but of the two it’s Fashion that’s the more potent force. A dress is everything. In For Better, For Worse (1919), she plays a rich young girl who calls her lover a coward when he chooses to stay out of World War I and care for crippled children, only to learn his true worth much later on. Her nobility is primarily expressed by her superb taste in clothes.

Swanson’s first DeMille film, Don’t Change Your Husband, with Lew Cody. A proper little wife … (photo credit 6.4)

One of her greatest hits under DeMille was Male and Female (1919), based on James M. Barrie’s The Admirable Crichton, and featuring her in a famous prolonged scene in which nothing happens except her bath. In a presentation that might be thought of as extended foreplay, the audience is first prepared for the delicious thrill it’s about to have by a card that says, “Humanity is assuredly growing cleaner—but is it growing more artistic? Women bathe more often, but not as beautifully as did their ancient Sisters. Why shouldn’t the Bath Room express as much Art and Beauty as the Drawing Room?” Why, indeed? Especially when the viewer is going to be allowed to peep in and watch the beauty disrobe and enter her tub. First, two attendants prepare Swanson’s bath—dropping in bath salts, adjusting the water temperature, and putting rose water into the shower she will take afterward. The narrative flow stops dead while Swanson enters and prepares to step into the sunken tub. Carrying loofahs and huge towels, the two attendants step regally forward to assist her in dropping her dressing gown to reveal the very white skin of her lovely back. As they raise a huge towel to cover her, she lowers herself majestically into the water with all the aplomb that a four-foot-eleven-inch woman in a Hollywood bathtub scene can possibly summon.

Gloria Swanson is not being presented as a mere sex object; she’s being presented as the representative luxury bather for the entire audience, male and female. (Everything about the movie—a kind of Upstairs, Downstairs story about the mingling of the classes on a desert island—stresses wealth and consumer goods.) She’s first seen following an introductory title card that presents her character name, Lady Mary, against the background image of a peacock with a fully spread tail. Her undergarments are shown in close-ups, spread out on a chair for the camera to linger over lovingly: lace underwear, silk stockings, frilly garters. The audience is given a look at her fancy silk shoes with enormous buckles being delivered outside her door by a houseboy, and our first sight of her presents her sleeping in a magnificent bed of silk and satin.

… and a glamorous figure of fashion and power (photo credit 6.5)

After her bath, further details of her ritzy life are depicted in an extended scene in which she does nothing except eat her breakfast. A butler, three maids, and a footman arrive to serve. One carries the tray, and another carries the little silver box that keeps her toast warm. The butler has to oversee everything, and one of the maids has to lift Swanson’s elbow and place a tiny pillow embroidered with little roses under it. There’s silver and crystal aplenty, and while Swanson lounges, the camera makes sure to show us her little feet in their beautiful stockings and white shoes. Everyone scurries around, indicating that this outrageous pampering is a daily routine.

It’s no wonder Gloria Swanson finally wanted out of these DeMille epics. Although later in the film she has more to do, and there’s exciting action involving a shipwreck and survival on the island, she was primarily being used as a clotheshorse, a female fantasy figure. Even on the deserted island, she’s decked out in a couple of fetching numbers made of leaves and twigs and skins, both of which have matching hats. She might also have wanted to leave DeMille while she could escape with her life. Male and Female is the movie with the famous scene in which Swanson lies down and lets a real lion put his paw on her back. In a “flashback” to Babylonian times, Swanson, a captive in chains and an excellent leopard skin, refuses the lust of the Babylonian king by biting him viciously on his hand. As a result, the “sacred lions of Ishtar” have to be trundled out so that Gloria, in yet another dramatic getup, can be carried in on an elaborate litter and tossed to them. (“I’ll tame her,” threatens the king …)*

During 1919, Gloria Swanson began to be a favorite with fan magazines, especially in fashion layouts. Motion Picture of August 1919 carried an article entitled “HATS! HATS! HATS!” in which she models a series of really bizarre chapeaus. “Gloria Swanson,” gushes the article, “is a svelte, stylish little person.” Gloria poses in beautiful close-ups in a “shopping hat” (which looks like a cereal bowl turned upside down, with a fern growing out of its bottom), an “afternoon hat,” a “boudoir cap,” a “bathing cap,” a “sport hat,” and a fish-scale turban that flaunts “gorah [sic] feathers.” (The turban has no specific function, except possibly to frighten people.) In the final portrait, “Gloria is not wearing a hat, but a unique hair arrangement which resembles her favorite turbans.” She looks dwarfed under a tower of hair, and highly uncomfortable.

Fan magazines featured her as a major spokesperson for their female audiences. In the December 1919 issue of Motion Picture, there is an article entitled “Gloria Swanson Talks On Divorce.” Gloria, aged twenty at the time, holds forth: “I not only believe in divorce, but I sometimes think that I don’t believe in marriage at all … After all, marriage is just a game. The more elastic the rules, the less temptation there is for cheating. I think that divorce should be made more easy, instead of more difficult. Yes, I believe in divorce as an institution!” (Swanson took the advice she gave her readership and used the institution of divorce herself a solid five times.) After all this, the magazine reminded readers that Cecil B. DeMille had personally chosen Gloria Swanson to represent the typical society woman in his “exquisite satires—satires that are doing their share towards forming a literature of the screen.”

As the calendar turned over from the teens to the twenties, ushering in the Jazz Age, Gloria Swanson was front and center as the representative of the modern American woman with style. Audiences loved her, and off-screen, Miss Gloria Swanson was strutting her stuff. Showing an amazing disregard for what others might think, she had begun to live a life similar to that of the glamorous women she played on-screen, women who pretty much did what they pleased. Having been married at so young an age to Beery, she now took on husband number two, Herbert K. Sonborn (in 1919), and made no attempt to hide the fact that she gave birth to his daughter, Gloria, even though motherhood was thought to diminish a star’s appeal in those years. In her autobiography, Swanson refers to the escalating troubles in this marriage (“I finally snapped over a remark he made about the number of internal baths I took”) and says she moved out on Sonborn in May 1920. (“In May The Great Moment was a huge success and I broke up my marriage with Herbert.”) She had barely passed her teenage years, and had already married twice and become a mother. Even more shocking, on her own during this time period she adopted a baby boy she named Joseph. For years, the rumor mill implied that this son was actually Swanson’s illegitimate child by Joseph Kennedy, father of the future president. In her autobiography, Swanson is very vague about the dates of her marriages, births of her children, and of this adoption, but most sources indicate that she hadn’t yet met Joseph Kennedy when she brought Joseph home, and that he was named for her own father.

Male and Female: first waited on hand and foot, fulfilling the audience’s dreams of luxury (photo credit 6.6)

But later paying her dues, shipwrecked, reduced to rags, and doing the waiting herself (photo credit 6.7)

In 1920, her fourth film with DeMille, Why Change Your Wife?, was released to great success. Swanson played a rich man’s unglamorous wife, who learns a great fashion lesson when her husband is stolen from her by a well-dressed rival. The implication is very clear: if she had worn better clothes, this calamity would not have taken place. To get her husband back, the wife has to subject herself to ostrich feathers and furs and long ropes of pearls.

Her last DeMille in 1920 was Something to Think About, in which she’s a poor blacksmith’s daughter. It’s an interesting film to watch because its plot is what many people believe all silent films to be—a melodramatic, old-fashioned story with religious overtones. Yet, recounting the events of the movie in no way gives a sense of how effective Swanson makes the material. Cast as the smith’s daughter, Ruth (“the flower of the forge”), she is at first only a schoolgirl. Her transformation from this happy creature (who jumps around hugging everyone) into a lovely young woman—and ultimately into an elegant matron—has the influence of Mary Pickford all over it. DeMille uses one of his favorite leading men, the popular Elliott Dexter, as a crippled philosopher (conveniently wealthy) who pays for Swanson to go away to school and proposes marriage to her when she returns home.

Swanson and Dexter plan to wed, but trouble arrives in the form of “strong young manhood” from a “straight and faultless mould.” Played by Monte Blue, Jim cannot stop himself from loving Ruth—and the two run away to the city on the eve of her marriage. Her father (famous character actor Theodore Roberts) is humiliated, and as he pounds out a horseshoe, he cries out, “I pray God I may never see her ungrateful face again.” Sparks fly up, and he is instantly blinded, or as a tart title card reminds the audience, “If we ask a curse—we got a curse!” Swanson’s husband, a sandhog, dies a hero’s death saving his comrades from the collapse of an underwater tunnel, while at home Swanson makes a pie. Left pregnant and alone, she returns home. Her father throws her out, but as she considers hanging herself in the barn, Dexter rescues her by generously offering a marriage “in name only.” Years pass, and Swanson grows to love her husband, but he gives her only coldness. (Meanwhile, her dad is blind in the poorhouse.) Suddenly, things are neatly wrapped up. Dexter’s faithful servant (Claire McDowell) has been lurking around, reminding everyone to have faith. She collects Swanson and the two do some serious praying, with excellent results. Dexter finds he can walk without crutches, and Grandpa, fishing blindly down at the stream, is united with Swanson’s little son. Sunshine floods the world.

Swanson with Wallace Reid in DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol (photo credit 6.8)

No recital of a story like this can possibly do justice to the competence of the filmmakers, the visual imagination that is employed in the storytelling process, and particularly to Swanson’s graceful ability to make her character attractive and believable. She wears only a few beautiful outfits in this movie, and is called on to prove she can act. She more than meets the challenge, and Something to Think About fueled her desire to do more, and to be taken seriously as something other than a clotheshorse.

Her last DeMille, The Affairs of Anatol (1921), loosely based on Arthur Schnitzler’s play, took her back to the more typical DeMille formula. She suffers the affairs of a philandering husband, always nobly taking him back, until he finally learns his lesson. In all such soap operas, Swanson never plays the other woman; she is always the focal point of sympathy for the audience—the wronged wife or the dutiful daughter—so that women in the audience could sympathize with her, while considering her the absolutely last word in chic. Swanson worked very hard for DeMille, cooperating fully with anything he asked her to do. At the time, she said, “I have gone through a long apprenticeship. I have gone through enough of being nobody. I have decided that when I am a star, I will be every inch and every moment the star! Everybody from the studio gateman to the highest executive will know it.” And she kept her word. “She is a sullen, opaque creature, an unknowable, but as enkindled as a young lioness,” said Adela Rogers St. Johns.

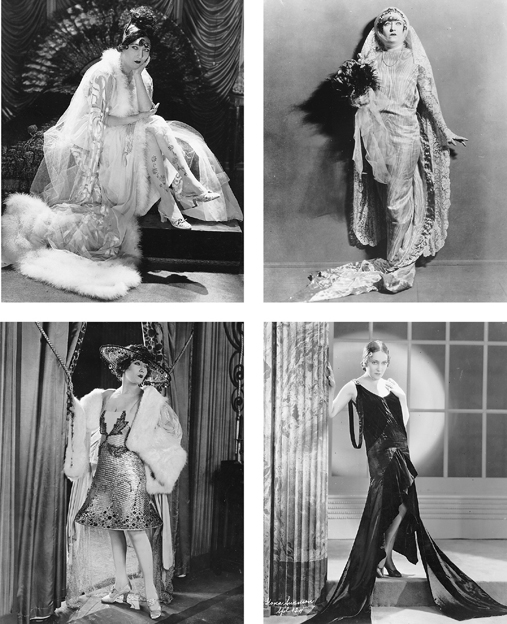

The DeMille/Swanson films are considered highly significant for providing modern audiences an insight into the manners and morals of their time. But they’re really about only three things: sex, women, and clothes. They reflect a flirtation with a new morality, and in particular, they begin to show a subtle questioning of the double standard, so they’re definitely about sex, but always in good taste—so good that sometimes the issue gets lost. In all of them, Gloria Swanson wears incredible outfits: fur-trimmed lounging robes; long necklaces with crystals, onyx, and jet; turbans with feathers and plumes; evening gowns with long trains covered in beads and bands of ermine. She wears her hair piled high on her head, skyscraperish (partly because this gave her height), with these elaborate structures decorated with silk bands, golden stars, and tiny white pearls. Many of her costumes have an oriental flavor, and others are art deco with angular cuts and matching headdresses of jeweled material. She sleeps in beds of satin and ruffles, and when she sits down, she sits on brocaded chairs. But best of all, when she takes one of her baths—and these bathroom scenes became a Swanson/DeMille trademark—she enters a chamber as big as a football field, luxuriously decorated with chinchilla rugs and black marble fixtures. The public loved her, but it also loved the clothes, the beds, the chairs, and especially the bathrooms. “The public, not I, made Gloria Swanson a star,” said DeMille, but he and his bathrooms played a major role in her success. He always showcased her, calling her his “young fellow” and praising her professionalism.

Alexander Walker described the Swanson role in DeMille films as that of “the playmate wife,” and historians cite her character as the modern female of the post–World War I years in America, the one most admired by American women. Swanson’s success in representing this creature was due both to her midwestern solidity and comic timing, which made her seem down-to-earth and basically good, and to her ability to dress up in exotic clothes, wield a cigarette holder, and look and act incredibly worldly-wise and sophisticated. (DeMille had been right—she knew how to lean against a door.) She effectively straddled the fence between realistic and fantastic, which was what the DeMille films made a fortune doing. (His method was shrewd. Show an orgy, and then put the idolators to death. Tempt the good wife and take her right to the edge, but let her come to her senses at the last moment. Have it both ways for the audience, the hallmark of the Hollywood film.) The DeMille/Swanson films are key to an understanding of the evolution of the female role in movies.

By the end of 1920, Gloria Swanson had become a household name and a top box office draw. Her movies with DeMille had all been first-class: well directed, brilliantly produced, and written with clarity and imagination. They had costarred her with such solid silent film names as Elliott Dexter, Lew Cody, Thomas Meighan, Theodore Roberts, Monte Blue, and Wallace Reid and contrasted her favorably with the other women in the cast—Julia Faye, Wanda Hawley, Bebe Daniels, Lila Lee. Swanson, however, wanted more, and when she got more, she wanted even more than that. She began to feel that DeMille was limiting her growth. (Certainly he stifled her considerable comic gifts, which were being put to no use.) Swanson had also learned about money, as Sonborn had shown her how to read a contract, shrewdly pointing out that DeMille might be her mentor, but he was not paying her the top salary that other stars were getting, or even always giving her star billing.

She left DeMille and began making movies exclusively for Artcraft’s parent company, Famous Players–Lasky/Paramount, where she would remain until 1926. Her first starring vehicle, in which her name appeared above the title, was The Great Moment in 1920.† It was an original Elinor Glyn story—the mark of 1920s class—and paired her with handsome Milton Sills, a matinee idol of his time. She plays a noble young English girl who falls in love with an American engineer. The high point, a tribute to Glyn’s idea of romance, occurs when a rattlesnake bites Swanson on the breast and the hero has to suck the poison out to save her life. Just how that pesky rattler got up there without her noticing is a bit of a puzzle, but it was hot stuff for an audience under the Glyn influence. Swanson appeared in two films in 1921, Under the Lash and Don’t Tell Everything. In 1922, she made Her Husband’s Trademark, Beyond the Rocks (which paired her with the up-and-coming Rudolph Valentino), Her Gilded Cage, and The Impossible Mrs. Bellew. At this point, she began to take full charge of her own career, and assert her independence. She made herself constantly available for publicity, and throughout 1922 countless articles about her life, her clothes, and her films appeared everywhere. The April issue of Motion Picture presented a large layout of photographs from My American Wife, which was planned for a 1923 release and would costar her with popular Antonio Moreno. The full story of the film is reprinted, from start to finish—Swanson was to play a young daughter of a Kentucky gentleman, a character who was “for all of her lack of years, a woman of the world.” She loves horses and horse racing and has captured blue ribbons around the world, racing as “N. H. Chester,” a name everyone knew but that “comparatively few people knew … was a woman.” Going to Argentina, she meets and falls in love with Moreno, whose mother cries out, “Never! Never while I live shall a LaTassa marry a woman of the race tracks!” (The photo caption above a shot of lovely Swanson dressed to the nines and holding a bunch of flowers answers back, “Gloria tosses her flowers in gay abandon.”) After it’s all settled, they get married and Moreno becomes ambassador to the United States, promising to “glorify the Argentine Republic with the aid and inspiration of my American wife.” So much for Mama LaTassa! All these photographs feature Gloria carefully posing to show off all the details of each outré outfit.

The 1922 fan magazines reveal two things about Swanson’s image. One is that she had a strong group of detractors, and the other is that everyone in the business was aware of her driving ambition (which she herself never tried to keep secret). In Picture-Play of September 1922, a writer named Ethel Sands comments on Swanson, “Either you are fascinated by her … or you don’t like her at all. People … argue about her … pro-Gloria and anti-Gloria. She’s called weird and freakish by many.” Some even thought she wasn’t very attractive. Adela Rogers St. Johns, who first met her at Triangle in 1917, later described her this way: “She was awful. Short and inclined to be dumpy. A strange face dominated by sullen grey eyes, with a long nose tilted upward, and a defiant mouth, whose upper lip seemed too short to cover her big strong white teeth.”

Motion Picture of June 1922 comments on Swanson’s ambition and her hard business sense with a thinly veiled critique: “Much as she loves her baby and her husband and her home, they could never mean everything to Gloria. Her career, her work in the studio is as vital to her as the oxygen she breathes … She is beautiful, as flawlessly beautiful as a diamond—and as cold.” To find such overt criticism of a star in a movie magazine of the 1920s is rare, although sly attacks were fairly common. About Swanson they came right out in the open. This article nails her, saying, “Gloria loves clothes, loves luxuries, loves fame. [She is] possessed of a will to get and keep the luxuries of this life … She is a dominating little woman … maneuvering her course with a careful rudder.”

Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife: glamour post-DeMille (photo credit 6.9)

The lady herself seemed unfazed by any of this. She never apologized for her ambition, later saying, “I’ve always been my own business manager and agent. Mary Pickford had her mother, Chaplin had his brother, Lloyd had his uncle, the Talmadges had Schenck, the Gishes, Griffith. I was always alone.” (Those who might want to point out that Swanson had plenty of business support from the powerful Joe Kennedy would do well to remember that he made a series of ruinous investments for her from which she almost didn’t recover financially.)

In 1923 and 1924, she went on making the kind of romances that audiences liked her in, but she also made a successful return to comedy, and found a director, Allan Dwan, whom she liked and felt understood her abilities. By 1923, she had worked out a new contract, which raised her salary to an astronomical $5,500 per week, and that allowed her to move to New York City and make her movies there. Swanson’s 1923 releases included the aforementioned My American Wife, plus Prodigal Daughters and Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife, and along with Zaza and Manhandled, she released The Humming Bird, A Society Scandal, Her Love Story, and Wages of Virtue in 1924.‡

One of the most successful of these movies was a Dwan film and the first of her New York–made movies: Zaza. The story of an actress, Zaza shows how intelligent Swanson was about her own image. She selected a story that contains humor and lively action—at one point she takes on another woman in a fight scene—but doesn’t forget the clothes and glamour that had lifted her to stardom with DeMille. After her six DeMille features, she understood how important clothes were to a visual characterization, and she knew what her fans expected. Zaza starts out as a rather low-class cabaret star, dressed in gaudy emblems of her success. She wears a diamond bracelet set with two big Z’s and has huge monogrammed Z’s on her gloves. She also wears a flashy necklace with a chain holding another big Z and her hair holds little crystals with tiny triangles at the base of them. These hang out of her puffy curls, catching the light so that Swanson is literally sparkling. She looks fabulous. Seven years later in the plot, her clothes have become very simple and elegant, signaling to viewers that Zaza has changed. She’s now a sophisticated lady, with a finer understanding of life because, after all, clothes make the woman.

During these years of success, fan magazines continued to point out that Swanson incited negative as well as positive feelings in moviegoers. The February 1924 issue of Picture-Play ran an article called “WHAT DO YOU THINK OF GLORIA?” by Norbert Lusk. The answer was ambivalent: “Either you rave about Gloria Swanson or you rage against her.” Referring to the many letters the magazine received regarding her stardom, Lusk said fans wrote either that “Gloria is a great actress or a terrible one,” that “she is endearing or repellant, beautiful or otherwise, and so on.” (As for himself, he comments that he found Gloria’s eyes “cryptic” because when he “looked into them, they told me nothing.”) Swanson was masterful at publicity, but she cut no slack for anyone, not even when she knew she was deliberately under scrutiny. Lusk interviewed Swanson in person, and he points out that although her day had begun at 6 a.m., it was nearly midnight by the time she could see him. He asks her boldly why some people hate her, and she replies with wonderful evasion: “Oh, it’s because it’s a matter of vibrations.” Not to be sidetracked, he presses on, “How much of your real self do we see on the screen?” To this, Gloria fires off, “Oh, do you mean am I a clotheshorse or just pretending to be one because it’s the most I can do? I love clothes—beauty—luxury—extreme styles. The urge for these is a part of me. It is what you might call my real self, I suppose, though there are other things in life. Don’t think I walk around in twelve-foot trains at home.” In conclusion, she reminds her interviewer that her pictures sell. For himself, he is willing to admit that Gloria Swanson is “polite,” but he adds that like “all these actresses,” she is definitely “different” from an ordinary person. (Wasn’t that the point?)

Zaza (photo credit 6.10)

Picture-Play claimed that such movies as her earlier Don’t Change Your Husband were popular only with women, not men. In assessing Swanson, the magazine once again refers to her “hard-driving career,” but adds that she “represents sophistication combined with freedom and extravagance and success with men.” In a perceptive discussion of her acting, the author, hostile to Swanson personally, pinpoints her ability by saying that her acting skills are “spontaneity, fire, mood, feeling, unselfconsciousness.” He concludes, however, by describing her as “grimly ambitious … just as determined now to be a great actress as she was once to get out of slapstick comedies. [Hers is] not a yielding nature, and she wants to hold on to what is hers.” Reading an article like this, one feels that all this is exactly why women and girls adored Gloria Swanson. Somehow she didn’t care what anyone thought of her. It wasn’t that she was insensitive, but she knew that for a woman to be successful she was going to have to forgo the idea that everyone in the whole world would love her and approve of her.

Gloria Swanson, Queen of Bizarre Fashion. (photo credit 6.11)

The costume that got away—Bebe Daniels in The Affairs of Anatol (photo credit 6.12)

Swanson lived lavishly and didn’t care who knew it. Once described as “the second woman in Hollywood to make a million [Pickford would have been the first], and the first to spend it,” she liked to give parties and have fun. “Oh, the parties we used to have!” she said. “It was not uncommon to have 75 or 100 people for a formal, sit-down dinner. But they weren’t stuffy. We all knew each other, and we had fun. In those days they wanted us to live like kings and queens … so we did. And why not? We were in love with life. We were making more money than we ever dreamed existed, and there was no reason to believe that it would ever stop.” In 1924, Photoplay reported on the ways Swanson spent her money one year: purses, $5,000; furs, $5,000; lingerie, $5,000; silk stockings, $5,600; perfume, $5,000; and gowns, $5,000. As for jewelry, she rented it at 10 percent of its total cost, running up a bill for $5,000 in one year alone. (Swanson also made some significant purchases. Her legendary one-inch-thick bangle bracelets made of rock crystal disks with circular and baguette-cut diamonds and crystal beads threaded on elastic were displayed alone in a specially designed case at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cartier show in the spring of 1998.)

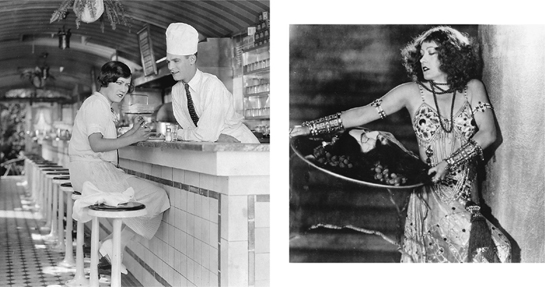

The two best Dwan/Swanson comedies are Manhandled in 1924 and Stage Struck in 1925. In both, Swanson manages to utilize her considerable comedic skills, send up her DeMille image with grace (but without malice), and deliver a heroine who wins the man of her dreams. Manhandled begins with a title that lays its morality out clearly: “The world lets a girl think that its pleasure and luxuries may be hers without cost—that’s chivalry. But if she claims them on this basis, it sends her a bill in full, with no discount—that’s reality.” Gloria plays “Tessie McGuire, one of the mob,” a low-level sales-clerk in the basement of Thorndyke’s department store. This movie connects her directly to her female fans in the audience—the ordinary young girls who admired her for her glamour and grit—through the device of having her play one of them. The opening sequence, one of her best comedy scenes, has Tessie, tired at the end of her day, struggling with her journey home on a crowded subway. Swanson skillfully plays out the role of the little person, buffeted and wedged in by bigger riders. First, she has trouble just getting through the turnstile, as others keep shoving her aside. Once she’s on the train, she keeps up her spirits as best she can, energetically chewing her gum and trying to hang on. Her hat keeps getting knocked down over her eyes, and her feet are constantly stepped on. Finally, she drops her purse. All the contents spill out and as she bends down to retrieve things, two men also bend to help her, so that her arms become entangled with their elbows. When they stand up to grab the subway straps they had been hanging on to, Swanson is lifted off her feet into the air, a prisoner. Later she is squashed on all sides, bumped back and forth as the car roars onward; her hat is knocked off and stepped on and the grapes it had been so ridiculously adorned with are ripped off. Then comes the final indignity—a guy winks at her. She pulls herself up into a pose worthy of one of her baroness roles and cold-shoulders him. At her station, she can’t get through the door because she’s so small. Every time she pushes toward the exit, she’s carried backward by the incoming rush of humanity. Finally, she makes it, flopping down over the turnstile as she exits.

Swanson in her famous subway sequence in Manhandled (photo credit 6.13)

By beginning Manhandled this way, Gloria Swanson, the great and glamorous star, shows what a swell fella she really is. Having objected to slapstick in her Sennett days, she now was a big enough star to feel she could get away with it. She had already proved her dramatic ability and sealed her image as a glamour queen. There’s also a sly subtext, a private conversation between Gloria and the shopgirls in the audience. “This is what men do to me, even though I’m Gloria Swanson. I just have to pick myself up and keep on going.”

As the story proceeds, she gets bored because her true love, Jimmy the garage mechanic (Tom Moore), is so caught up in work he never takes her out. She goes to a party with “Pinkie, who believes heaven will protect the working girl and send some bracelets, enough to keep her wrists warm.” At the party, Swanson is shown eyeballing the “ladies,” who are beautifully dressed and very sophisticated. Swanson admiring Swanson-ites! She ogles the “name” guests, such as Ann Pennington, a star from the Follies, who plays herself in a cameo role. Pennington, who is even smaller than Swanson, does her famous dance, and Swanson later gives a brief imitation, but her underpants fall down. Eventually, she moves up out of Thorndyke’s. First she becomes an artist’s model, striking a pose that presents her in elaborate oriental garb. She looks like the DeMille Gloria, serene and mysterious in an outlandish headdress and gold-embroidered costume, but after holding this pose for a while she’s told she can rest, and then she swiftly turns into an entirely different person with a comic stretching of her limbs and a funny little shake.

In the end, of course, she learns that the rich life is not for her, just as her Jimmy returns from Detroit, where he’s sold an invention that makes him a millionaire. (He enters the apartment house and instructs the landlady: “Step aside, madam! I’m a millionaire!”) Later, seeing Swanson dressed up like a Gloria Swanson glamour figure, he suddenly spurns her, saying: “You’re like the goods you hated to sell in Thorndyke’s basement—rumpled—soiled—pawed over—MANHANDLED!” Everything gets sorted out, needless to say, and the two end up in each other’s arms. Manhandled is one of Swanson’s most representative films because it shows us all possible Swansons: the elegantly dressed clotheshorse, the exotic mannequin, the lovely leading lady, and the deliciously comic little girl.

Swanson as a waitress who dreams in Stage Struck, with Lawrence Gray … and what she dreams of—beads, bracelets, and victim (photo credit 6.14)

In Stage Struck, Swanson is wonderful. Working as a waitress in a pancake house, she is seen flipping a pancake onto her own head, juggling trays, getting kicked in the seat of the pants, and, amazingly, donning a mask and boxer’s outfit to enter the fight ring as “Kid Sockem” so she can knock the block off Gertrude Astor in a boxing match. It’s pure slapstick comedy. (Those who think Gloria Swanson is nothing but Norma Desmond have to see this movie.) The shrewdness about her image is again on display. The movie opens with magnificent color sequences (color by Technicolor) in which she is seen in a series of fabulous costumes, supposedly portraying a famous actress who is re-creating the great roles of theatre and history, such as Salome. This turns out to be a dream sequence, and the little pancake waitress is then introduced in plain clothes, hilariously practicing her acting lessons in front of a distorting mirror. Everything Swanson does is very precise, very small, very on the mark—she’s a controlled pantomimist and a good mimic. She’s a natural clown, a kind of female Charlie Chaplin due to her small stature (which is why she could imitate Chaplin so well in Sunset Boulevard).

In 1925 Gloria made off-screen history by being officially the first big star to marry European aristocracy. On February 5, she wed Henri, the Marquis de la Falaise de la Coudraye, husband number three, and on her way back to Hollywood from Europe, sent Adolph Zukor a famous cablegram: “Am arriving with the Marquis tomorrow. Please arrange ovation.” The arrival was indeed something. She was met by a brass band, and she and her prize-catch husband (and Louella Parsons) drove in an open car through the streets from the station to the studio. Gloria stood up in the backseat holding huge bouquets of flowers and blew kisses to her loyal fans who lined the streets and cheered their heads off. (This marriage ended in divorce in 1930, after which the Marquis went on to marry another glamorous movie star, Constance Bennett.) Of her many failures in marriage Swanson would say, “The mess I made of marriage was all my own fault. I can smell the character of a woman the instant she enters a room, but I have the world’s worst judgment of men. Maybe the odds were against me. When I was young, no man my age made enough money to support me in the style expected of me. There’s no sense kidding myself—I loved all the pomp and luxury of that style. When I die my epitaph should read: She Paid The Bills. That’s the story of my private life.”

Swanson had met her marquis on the set of one of her movies. She had always wanted to play the role of Madame Sans-Gêne from the successful play by Victorien Sardou and had managed to persuade Adolph Zukor, her boss, that she would not only be perfect in the role but that it would be a financial blockbuster. He had acceded, and in November 1924 she traveled to Europe for the authentic French locations. The marquis was hired to be her interpreter, since the movie’s director, Leonce Perret, spoke very poor English. Madame Sans-Gêne was the most ambitious screen role Swanson had undertaken.

The plot sounds like a perfect Swanson story.§ According to reviews, she begins at the bottom, as a little laundress who does the young Napoleon’s washing. She’s all sympathy and support when he can’t pay his laundry bills, stealing stockings from other customers for him and mending his shirts and darning his hose. Reviews indicate that Swanson’s gift for comedy is well used, and that she’s lively and clever—an altogether appealing laundress. Later, she emerges into her other Swanson self: the well-dressed duchess of Dantzig, very beautiful and elegant but not without her comedy touches. The duchess loses her petticoat when she climbs into her carriage (no other star ever had as much trouble with undergarments as Gloria Swanson), and happily sheds her elegant shoes when they pinch her feet.

Variety, like the Times, spent more time reviewing the audience than the film itself, which they dismissed with a coldhearted “If it were not Gloria Swanson appearing in the title role … Famous Players would have nothing to brag about as far as motion picture entertainment is concerned. Gloria … does make it possible for one to sit through the feature.” According to Variety, the publicity and exploitation campaign behind the movie were unprecedented.

The famous lost film, Madame Sans-Gêne (photo credit 6.15)

Never has Broadway seen a splash such as was given to this star. Her name in the largest electric letters ever given to an individual on Broadway decorates the facade of the Rivoli; the house is shrouded in the tri-color of France and the Stars and Stripes, and all the other buildings on both sides of Broadway from 49th to 50th streets are similarly decorated with the result that one can hardly get standing room in the theatre … Outside the theatre the police reserves from the West 30th and West 47th street police stations were trying to hold back the frantic mob of the sightseers who were trying to glimpse the star … So intent on rubbering were they that they did not notice the dips working in the crowd, and many a one went home lighter in pocket because of the light-fingered gentry present.

(There was a similar crush when the film opened in Los Angeles shortly afterward.) How did Swanson feel about the adulation? Ever the realist, she wrote in her autobiography that she had been thinking, “I’m just twenty-six. Where do I go from here? … I was thinking that every victory is also a defeat. Nobody gets anything for nothing.”

In 1926, Gloria Swanson did something that few actresses had dared to do—she left the security of Paramount and went out on her own to produce her own features, forming Gloria Swanson, Inc., with her movies to be released by United Artists. In order to make the break from Paramount, she had turned down an impressive million-dollar offer from Zukor, so she felt she should make the most of her freedom and resolved to try artistically bold movies.

Unfortunately, her reputation as nothing but a clotheshorse is partly substantiated by the first of these, The Loves of Sunya (1927), a story about a woman who has no fun being a dutiful wife but who also has no fun being a career woman. (The life of a woman, it seems, just isn’t much fun.) Sunya’s compensation, however, is that she can wear very good clothes and particularly dramatic jewelry, all of it made of diamond-designed triangles, circles, and squares, very art deco in style. Swanson again gets to present her screen character in several different modes. At first, she’s a sweet young girl learning from a traveling soothsayer what her future might be, according to the choices she makes regarding her life. What she sees inside his crystal gives her a chance to be pure, then sophisticated, then remorseful, and finally downtrodden. In particular, she plays a terrific drunk scene as a soused opera star who has to go on to sing Tosca. “Once we have made our choice,” the movie tells women, “we must be honest. If it were not for that … what?” Swanson lives out the various female choices in great style on behalf of her audience—and she knew what her audience wanted from her. Heavy publicity combined with her glamour to draw big audiences; her company netted a hefty $5,370. Gloria Swanson, Inc., was off to a strong start.

Two of her best movies, both made in 1928 for her own company, are available today in incomplete forms, Sadie Thompson and Queen Kelly. Many feel that her Sadie Thompson is not only the best version of the Somerset Maugham story ever filmed, but also her best performance. The last scenes are missing from the only existing print, but Dennis Doros of Milestone Films has restored and released the film using stills, remaining footage, and the original script to guide him. This affords today’s audience a chance to see the mature Gloria Swanson at the peak of her career and her beauty, performing confidently in a role that uses all her potential. Swanson was at this point totally unafraid to look and dress cheap; after all, she had more than proved herself as a fashion plate. Her eloquent and expressive face is used equally well for scenes of flirtatious behavior, comic playfulness, desperate fear, and passionate anger. Swanson exudes a healthy sexuality, a wholesome sense of herself as a woman. She doesn’t simper or vamp in her scenes as the sexy Sadie; rather, she just moves forward in the frame as if she were an attractive woman who knows she’s attractive, and who knows, understands, and likes men. When she and Captain Tim O’Hara, played by a roguish Raoul Walsh, who also directed, grow attracted to each other, their desire takes a playful form. (Walsh is excellent as the simple hero who, as someone remarks, “is a beautiful bird, but he flies straight.”) Swanson hides his hat behind her back, and he pushes her forward across the room in mock battle, the two of them sparring and playing and flirting in high spirits and with obvious pleasure. Theirs is not steamy sex, as depicted in the 1953 Miss Sadie Thompson starring Rita Hayworth, and it’s not low-down and cash-on-the-barrelhead sex as in the 1932 Joan Crawford version, Rain. When Sadie repents, Swanson plays it in a highly original way—she just lets all the life go out of the character. She deflates Sadie, makes her into what is almost a collapsed bag of a woman. She’s still beautiful enough to tempt Reverend Davidson, but it’s as if the essence of who and what she was had been killed. Lionel Barrymore, in the role of the twisted reverend who temporarily crushes Sadie’s spirit, is austere, with an almost evil cunning about him. Barrymore isn’t yet debilitated by his arthritic condition, so he stands ramrod tall, rigid, unbending.

As Sadie Thompson: happy before conversion … and miserable afterward, with Lionel Barrymore as Reverend Davidson (photo credit 6.16)

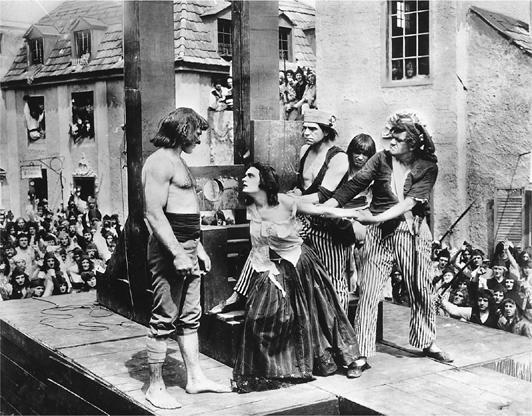

Swanson’s notorious lost epic, Queen Kelly, was begun in 1928, as sound hovered over Hollywood. If the film had been finished, it would have run for thirty reels, or approximately five hours. The movie was a “Gloria Swanson Pictures Corporation” production, with Swanson in partnership with her lover, Joseph Kennedy. Direction was under the leadership of the great Erich von Stroheim, creator of such masterpieces as Greed, The Merry Widow, and Blind Husbands. Had it been completed, it would have been von Stroheim’s eighth movie; as it turned out, it was his final silent film. Infuriated by what she considered his excesses, Swanson closed down production after approximately one-third of the script had been shot, and based on what is available for viewing today, the stoppage was a major loss to film history. Eventually, Queen Kelly was handsomely restored to a ninety-seven-minute version, using remaining footage, stills, and the original full orchestral score that was discovered during restoration. (In 1985, Dennis Doros, who had also directed the restoration of Sadie, made available to audiences the most complete version of Queen Kelly ever assembled.)

Queen Kelly showcases Gloria Swanson at her best. In a sense, it’s an overview of her career, an epic that allows her to go from being a playful, amusing convent girl (her Sennett days) to a beautifully turned-out young woman (her DeMille spectacles) and on into an actress of maturity and subtlety, a sophisticated woman of the world (the kind of roles she hoped her own production company would provide her). She is ravishingly beautiful in the footage, which includes the famous images of her in close-up, kneeling to pray amidst a screenful of lit candles. This scene was later used in Sunset Boulevard to show what Norma Desmond had been like as a young actress. “We had faces!” is a line inspired by Gloria Swanson in Queen Kelly.

Swanson as Patricia Kelly, or “Queen Kelly,” as her lover dubs her, has everything it takes to portray a character full of curiosity, life, and desire, but who is still innocent of love, though eager to be initiated. She is like a pure jewel inside the very, very oddball setting provided by the perverse talents of von Stroheim. His stunning images include the naked, wild-haired Queen Regina the Fifth (Seena Owen), drunk in her bed, cuddling her fluffy white cat (decked out in ribbons) to her naked body … Swanson, a virginal convent girl in white, with her bloomers down around her ankles, laughed at by the handsome prince and his troops because her elastic gave way … the kinky byplay in which Swanson boldly picks up these same undies and flings them in the face of the prince (Walter Byron), only to have him respond with delight, sniffing them delicately and claiming them as a token … the mad queen whipping Swanson, driving her out into the darkness in her white nightie … and Swanson’s arrival at her aunt’s brothel in Dar es Salaam (where she will end up as owner, a power figure dressed totally in black).

Von Stroheim’s gift was for detail, and Queen Kelly’s visual world of decadence and sophistication is unparalleled. The underpants scene is a perfect example of his talent for suggesting ripe sex mixed with a level of innocence and purity without which his particular brand of kinkiness doesn’t work. Swanson’s convent girl knows her undies should never be seen, particularly by a troop of soldiers, and she knows that above all else, she should never let a man handle any clothing that had touched her private parts. Yet her considerable fire and anger motivate her to toss the garments in the prince’s face. She wants to be rid of her innocence, and shows her penchant for passion, her fiery nature. Swanson plays her role perfectly, capturing all its anger, humor, sexual heat, and innocence. She was perfect material for von Stroheim to mold. In a sense, her career ended just as she hit her peak, and her gifts for comedy, tragedy, bizarre sexuality, and passion would not find a movie outlet again until she was fifty years old, in the hands of another German, Billy Wilder, in Sunset Boulevard.

In the film that was never finished, Queen Kelly: from convent girl with Seena Owen (photo credit 6.17)

The disappearance of Queen Kelly and Sadie Thompson for many years, so that modern viewers didn’t get to see them even in the rare instances when silent classics were revived, diminished Swanson’s reputation as an actress. (“I was a star at twenty-one,” said Swanson, “and a has-been at thirty-three.”) Although she is known as one of the four “fabulous faces” of American movies—along with Garbo, Crawford, and Dietrich—hers is often thought to be the least beautiful, least interesting face of the group. Seeing her animated, alive, and moving, and watching her magnificently expressive face at work reveals quite a different story. A touch of meanness settles around her mouth and eyes in still photos, but this disappears when she is involved in movement and action. (Arthur Bell, the poisonous but funny writer for the Village Voice, once wrote of Swanson, “I’m sick of seeing her mean little face all over town.”)

to brothel madame (photo credit 6.18)

Despite her best efforts, Swanson’s career floundered in the 1930s. It wasn’t because of sound, because she had a lovely speaking voice and could sing reasonably well. In her first sound movie, The Trespasser in 1929, she not only introduced the song “Love, Your Magic Spell Is Everywhere” (written especially for her), but she received her second Oscar nomination as Best Actress of the year. (Her first was for Sadie Thompson, and Sunset Boulevard was her third, but she would never win.) Her reviews were excellent, and she seemed to have glided smoothly from silence to sound, making possibly the easiest transition of any of the great 1920s names. She was only thirty-one years old, a tremendous star, and a two-time Oscar nominee. For reasons that are not entirely clear, however, nothing seemed to click for her ever again, except for Sunset Boulevard. She made What a Widow! in 1930, Indiscreet and Tonight or Never in 1931, A Perfect Understanding in 1933, and Music in the Air in 1934. None of these films was particularly successful, and none did anything to revitalize her career. She told David Chierichetti in 1975 that “the picture thing was very difficult for me at that time. It’s a long, tiresome story. They didn’t want stars to be producers.” Her strong will, her independence, and her very 1920s “modern woman” image may all have worked against her as the new decade took hold. Swanson also had other interests, and from 1934 on, she was off the screen for seven years, until Father Takes a Wife in 1941. After that, she didn’t appear again in movies (except in a compilation of clips from Sennett comedies called Down Memory Lane that was released in 1949) until Sunset Boulevard. (And for that matter, the latter didn’t do much for her, either. After her huge success in it, she made only Three for Bedroom C, a lackluster comedy in 1952, and Nero’s Mistress, a European mishmash in 1962. There was also a second compilation film, When Comedy Was King, in 1960.)

Sunset Boulevard, directed by Billy Wilder and written by him with Charles Brackett and D. M. Marshman, Jr., costarred Swanson with the young, handsome, and talented William Holden. Her old director, Erich von Stroheim, played a supporting role as Max, her former director now turned lifetime butler and confidant. The movie was an enormous success for everyone involved, and for Swanson it meant that she was back in the limelight again. Although she lost out in the Oscar race to Judy Holliday (who won for Born Yesterday), Swanson had come back after a long dry spell, and she came back at the very top.

Sunset Boulevard is about a silent film star who wasn’t just an ordinary silent film star but was unique, beautiful, talented, and legendary. (“Madame is the greatest star of them all,” intones Max.) There has always been much speculation as to just whom Norma Desmond was modeled on, but it was probably no one actress. She’s most likely a combination of the ego of Negri (who always knew what she was doing) and the genuinely crazy Mae Murray (who apparently never knew what she was doing). Having Swanson play the part verifies the character, and, in fact, gives the entire story a credibility it might not otherwise have. She’s magnificent. Who could know better than she did how to play an exotic diva from the era? Everything about her, from her leopard trim, her cigarette holders, her bangle bracelets, to her bed shaped like a golden swan and her outré open-air automobile seems completely authentic—because it is. And when Norma goes on the lot, to Swanson’s old studio Paramount Pictures, and meets her old director Cecil B. DeMille playing himself, everything rings true. For many people in the audience, it was an extraordinary blurring of fact and fiction, since for them it had been less than twenty-five years since it had all been real. Swanson herself was just past fifty years old, yet she and the world of the movie seemed to come from a time and place so remote that few could remember it. When Norma’s bridge group meets, and the other players include Anna Q. Nilsson, Buster Keaton, and H. B. Warner, older people in the audience gasped. (I know. I was there, ushering, watching it numerous times.) And, of course, being able to use clips from the never-released Queen Kelly not only gave viewers Norma as she authentically was as a younger woman, but also convinced them that it could have been Norma, not Swanson, in the part, because they themselves had never seen it as a Swanson film. This was heady stuff, and when you add in Swanson’s imitation of Charlie Chaplin, the superb writing and directing, the other members of the fine cast, the art direction and music, the moody cinematography—you have a masterpiece. Few actresses ever find a role like Norma Desmond. In truth, only one did, and she more than met the challenge. When Swanson rises up in the flickering light coming down from the screen, and with genuine passion—and considerable nuttiness—cries out, “We didn’t need dialogue! We had faces!”—her profile stops any arguments.

Swanson in her last great role, Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard (photo credit 6.19)

After Sunset Boulevard, Swanson’s name came alive to a new generation who did not know her and was born again for those who did. Yet the role of Norma Desmond was so powerful, and depicted such an obsessed character, that perhaps it doomed her. People began to think that Gloria Swanson was Norma Desmond. She never quite shook off Norma’s shadow. Even though she made comedy appearances on television, starred on Broadway in a revival of Twentieth Century (with Jose Ferrer), and took over another leading role on Broadway in Butterflies Are Free, her career was once again associated with tragedy and confused by the mingling of her personal life with her performance life. Gloria the Great finished her remarkable career on film in a way that was totally appropriate for her: her final role, in Airport 1975 (1974), is a cameo as herself—what could be more perfect than that? Hearing that the plane is going down, Swanson elects to forget her jewel case and save her autobiography—a shrewd business move by the character/movie star who had always known how to run her own business better than anyone else, and who was always a good judge of value for her money. And she looked youthful, slim, and still beautiful.

Gloria Swanson was a true film phenomenon. She endured past the end of her movie career in ways that few of her silent contemporaries could match. Always a capable businesswoman, she found an outlet for her energy and intelligence in many ventures. There were her fashion designs (“Gowns by Gloria”) and her health food lectures. Swanson was famous for having become a health nut very early, a nutritionist before it was fashionable. Sometime in the 1920s she stopped eating salt, red meat, and dairy products, existing on a diet of seaweed, bread, herb tea, and organically grown vegetables cooked in her own pressure cooker, which she hauled everywhere with her. (Scoffers should consider that she lived to the healthy old age of eighty-four or eighty-five, dying in 1983 at home in New York, still looking slim, energetic, and smooth-skinned.) She also married three more times, and gave birth to another daughter, Michael, and remained devoted to her children.‖

In fact, one of the most interesting aspects of Swanson’s career is her motherhood. More than any other actress of her time, she was charged with having a raging ambition that bordered on ruthless; like Mary Pickford, she had tried to direct her own career, shape it, and control it. Yet despite this, plus all the foolishness of her personal life with its luxury, publicity, rumors, and marriages and divorces, she raised two daughters and a son and never made any attempt to hide them away or deny her motherhood. And then she openly celebrated becoming a grandmother to seven grandchildren. Swanson, the woman who had had it all, claimed that the most exciting moment in her life was the first time she held “my child in my arms. I wanted children more than anything else,” she said. “Oh, I could say it was coming back from Paris with a new husband, the marquis, and taking a private train across the country, or I could mention the film festival in Belgium, where every theatre was playing a Swanson picture. But when you come right down to it, and you get old and they put you out to pasture, who’s around? Your family and your dear ones, that’s who.” (Yes, it was the family, but she threw in Paris, the private train, and the film festival.)

Swanson’s movie career, as Richard Koszarski points out in An Evening’s Entertainment, is not one that displays a “conventional arc of achievement,” but rather a “series of plateaus.” She isn’t easily categorized, and she doesn’t have a single dominant persona … other than that of Gloria Swanson, Movie Star, her off-screen self (or possibly the erroneous “Norma Desmond” label). Over the years, she received many accolades, among them a tribute at Eastman House in Rochester, New York, where at her retrospective in 1966 she proved herself still a colorful quote machine, saying, after the films were shown, “I must say I got fed up looking at this face of mine. First it was a pudding, then it was an old dumpling. Talk about the face that launched a thousand ships—this was a thousand faces that launched I don’t know what—a career, I guess.” She also showed her serious side by saying, “Failure is never easy to deal with. Success is impossible unless you’ve had the experience. I like making movies better than anything else.”

Although she was probably associated with the silliness of movie stardom as much as anyone in the business, there was always something profoundly sensible about Swanson. (“I guess I’m an old ironsides,” she once said.) No matter what, she always kept her head straight and her feet on the ground. Instead of relying on men to make her deals, she became her own agent and learned how to handle her own business. She was as colorful and quotable and demanding of her rights as any star, but she was always practical and cut her losses. She kept advancing her product, improving it, updating it—the product being herself, Gloria Swanson. “I saved my own career,” she said.

To the end of her life, Gloria Swanson knew how to play her part. No Norma Desmond, she was nevertheless always ready for her close-up. When she was eighty, she was still walking around grandly, carrying a single red rose and demanding that her theme song, “Love, Your Magic Spell Is Everywhere,” be played. (“Her greed for fame is amazing,” wrote James Robert Parish.) And yet she never became one of those aging movie stars for whom there is no life, no laughter, no honest human contact. Somewhere deep inside her there still seemed to live that little clown from her Keystone years. No matter how grand she acted, or how expensive her clothes were, no one could possibly believe that she was really from the upper echelons of society. Like Joan Crawford, who took her place as the representative shopgirl aspiring to wealth and society, Swanson was common clay. The audience knew it, but they loved her lifelong performance as the crazy movie star. Furthermore, they forgave her for it in the end, and let her escape from it.

That would not be as true for Pola Negri.

Pola Negri may have been the most colorful star ever to appear in silent films. Her over-the-top antics off-screen seem to have totally obscured her actual career, and certainly her talent. She was an excellent actress, capable of playing with real passion and fire, but her shenanigans turned her into the fundamental caricature of a silent movie star, almost a real-life Norma Desmond. (It’s rumored that Billy Wilder first offered the role of Desmond to Pola, who is said to have thrown him out. She took her career seriously, and to lampoon herself was unthinkable to her.) Although her remaining fans are still loyal, even fanatical about her, Pola Negri today is almost entirely forgotten.

One contemporary critic called Pola “all slink and mink,” and another wrote, “You had the feeling that the back of her neck was dirty,” by which he was making a clumsy attempt to say that Pola Negri seemed earthy, like an early Anna Magnani. Whatever she was, she knew how to sell it. She had a real talent for front-page publicity, and she represented, as well, that inevitable lure for Americans—the European sensibility. She was foreign, and that meant unencumbered by puritan ideals.

The story of Pola Negri, like its leading lady herself, is a colorful one. Her birth date, as with so many birth dates of female movie stars, is subject to negotiation. Some say she was born in 1894, others in 1899, but the general idea is that she was born during those last years of the nineteenth century. There are many versions of her story, and which of them (including her own) is true is hard to decide. Here’s one of them: She was born with the impossible name of Barbara Apollonia Chalupiec in Janowa, Poland. She studied at the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg and at the Philharmonia Drama School in Warsaw, and made her debut in Poland as an ingenue at the Rozmaitoczi Theatre. She received excellent notices, particularly for her performances as Hedvig in Ibsen’s Wild Duck and the title role in Gerhardt Hauptmann’s Hannele. These successful appearances led her to be invited to make films in Poland, and her movie debut is assumed to have been in 1914, in Niewolnica Zmyslow (no American title). She became a top star quickly, and during this period she also appeared in Max Reinhardt’s celebrated stage pantomime Sumurun, first in Poland and later in Berlin. Arriving in Berlin in 1917, she made a series of films there, some of them wonderfully comic shorts. For five years, she was at the very top of the German film industry, and also became a favorite stage actress. The most important thing that happened to her, however, was meeting the great actor/director Ernst Lubitsch. Together, Negri and Lubitsch made a series of films in Berlin that included The Eyes of the Mummy and Carmen in 1918; Madame Du Barry in 1919; the filmed version of Sumurun in 1921 (with both Negri and Lubitsch repeating their stage roles); The Wild Cat (also 1921); and finally Die Flamme (called Montmartre in the United States) in 1922.

Negri and Lubitsch found popularity with American audiences when three of these films were released in the United States: Carmen in 1921, retitled Gypsy Blood; Madame Du Barry in 1920, retitled Passion; and Sumurun in 1921, retitled One Arabian Night. When these imports arrived on American screens, audiences were bowled over by Negri’s strong sexuality, her fearless portrayals of passion, and her animal magnetism. She was promoted as a descendant of Polish Gypsies, the implication being “and that means she’s not bound by our rules.” Pola Negri brought Americans her own kind of “new modern woman”—an openly sexual and sensuous creature who made absolutely no apology for it.

Negri’s German films by Lubitsch represent her early years very successfully. Her talents are easily observable in Passion. She holds a viewer’s attention, and she plays a fully developed character. In the silent era, glamour girls were usually one thing or another—good or bad. Stars were divided into those who scampered and those who simpered, the virgin or the whore, the girlishly attractive or the womanly seductive. Negri in Passion is everything. She is scintillating and extremely attractive, with the implication that men are drawn to her not for her decadence or erotic posturing but for her impulsive, hearty sexuality, which they long to experience. She’s unafraid of sex, and makes it clear she wants it, too. (Negri will not be jumping off any balconies to avoid a “fate worse than death.”) The men in her movies can’t resist her. They drop like flies. Imagine the impact it must have had on audiences in 1921 when they saw Pola Negri, as Madame Du Barry, and Emil Jannings, as King Louis XV, enact the real thing in Passion. While Negri leans back sensuously on her luxurious bed, King Louis is seen slipping her little shoes on and off her feet. (She won’t get up until she’s properly shod, and properly shod means a king must do the job.) Louis kisses her feet and calves, licking one toe. Then he clips her fingernails for her … and you didn’t see that every day of the week (and still don’t). When Dan Duryea paints Joan Bennett’s toenails in Scarlet Street (1945), directed by another German, Fritz Lang, the scene is chillingly decadent, sinister in its implications. In Passion, Jannings playing with Negri’s feet and nails may seem slightly besotted, or possibly hilarious, but it also seems like real love.