Sunday was a quiet day for the parties involved in the Theora Hix murder. Melvin Hix arrived in Columbus from Bradenton, Florida, to claim his daughter’s body and was shocked to learn from police of Theora’s relationships with Meyers and Snook. “I have nothing left but a broken heart,” Hix told reporters when he left the Meyers mortuary after viewing his daughter’s body.

The various suspects, persons of interest and others connected to the crime used the rest of the weekend to find lawyers, as did the Hix family.

On Monday morning, Prosecutor Chester convened the Franklin County grand jury, prompting speculation that a murder arrest was near. In fact, the grand jury met every Monday, as the Ohio Constitution requires that every felony case be presented to the grand jury for indictment. Chester used the grand jury summons to bring in the minor players connected to the Hix case, getting their statements on the official record. The grand jury adjourned in the early afternoon once its regular business was finished and no indictments related to Theora’s murder were handed up. One of the witnesses before the grand jury was Melvin Hix, who refused to accept the statutory one-dollar compensation for a grand jury appearance.

John Chester Jr., described by the press as “the boy prosecutor,” was young and new on the job as prosecutor, but he was not inexperienced in representing the people. Before beginning his service as the Franklin County prosecutor in January 1929, he served as prosecutor in the Columbus police court. There was no doubt in his mind, however, that the Hix murder was the biggest case he had ever faced, and he attacked it with dogged determination.

A more seasoned prosecutor would have allowed the police to do their job, but Chester was fanatical in his pursuit of a solution to the case. Under normal circumstances, the prosecutor, although he is the chief law official in an Ohio county, does not conduct the criminal investigations—that is the role of the police. However, Chester inserted himself into the middle of the Hix murder investigation almost immediately. He was present during most interrogation sessions, and rather than serving as the department’s legal advisor during this phase of the case, Chester usurped control from Chief Harry French and commanded the investigation. There were any number of reasons why Chester would step in where he was not needed, none of which reflect very charitably on him. Perhaps he wanted to establish himself as the chief law officer in Franklin County in more than just name or because the high-profile nature of the case could open the door to more and better things. In any event, French stepped aside and let Chester call the shots.

The boy prosecutor may have been a great legal mind and a more than competent lawyer—one of the preeminent Ohio law firms bears his name—but he was not a cop, and he did not have a detective’s instinctual ability to know how to question a suspect. At the time, Chester knew only one way to get the information he wanted: the aggressive cross-examination of a prosecutor.

Chester set the tone for his relationship with Snook’s defense team when he denied Snook’s lawyers, retired judge John Seidel and E.O. Ricketts, an opportunity to talk to their client. At first, Chester refused to allow the lawyers any access to their client, causing Ricketts to bang his fists on the door to the detective bureau where Snook was being questioned. The prosecutor relented a bit and allowed Ricketts and Seidel to speak with Snook with police officers present.

For Ricketts, an emotional and capable criminal defense lawyer, fiveminute meetings with a client in the presence of the police were insufficient. When a sheriff’s deputy refused to allow them access to Snook, the defense team was forced to get a mandatory injunction from Common Pleas Court judge Dana F. Reynolds.

By modern standards, Chester’s actions seem outrageous and a violation of Snook’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel. But in 1929, the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only applied to federal criminal matters. It would not be until 1961 that the Supreme Court held that the Sixth Amendment applied to state criminal trials, and even then the Sixth Amendment only factored into courtroom proceedings, not custodial interrogations. The Ohio Constitution was silent on the idea of a suspect’s right to legal counsel. As far as the law was concerned, suspects like Snook were on their own.

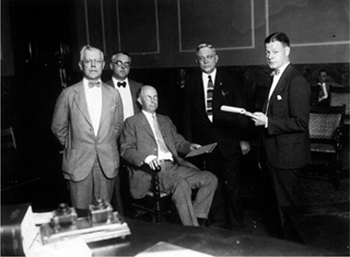

Dr. Snook (seated) surrounded by Sheriff Harry Paul, John Seidel, E.O. Ricketts and Prosecutor John J. Chester Jr. Courtesy of the Columbus Dispatch.

Too late for the morning Citizen but timed perfectly for the Dispatch’s early edition, Detective Lavely took Snook on a trip to the love nest and the murder scene. At this point, Snook had been spared the ordeal suffered by Baldy Meyers in being forced to view Theora’s remains at the mortuary. The papers reported that Snook was cool at the murder scene, “except for a slight shudder when he looked upon the blood-stained grass where the body of the girl was found.” Reporters were not allowed to accompany the group into the apartment, so what happened there remains a secret.

Also on Monday, Ohio State University president George Washington Rightmire dismissed Snook from the university faculty. Meyers and Snook were not the only OSU employees to be terminated over the Hix murder. When an investigation and audit criticized the Ohio State University Veterinary School, Dean David White was held responsible and forced to resign.

A sketch of Dr. Snook that appeared in the Columbus Citizen.

White was collateral damage in the excitement surrounding the first days of the Theora Hix case. When Snook falsely alleged that Theora was a drug addict who hounded him for cocaine and marijuana, the federal narcotics bureau briefly got involved in the investigation and found that the controls over the drugs in the vet school were lax. The university could not let such a lapse go unpunished, and White, despite a stellar career in building the veterinary school into one of the nation’s top programs, was chosen as the sacrificial lamb and pushed into retirement.