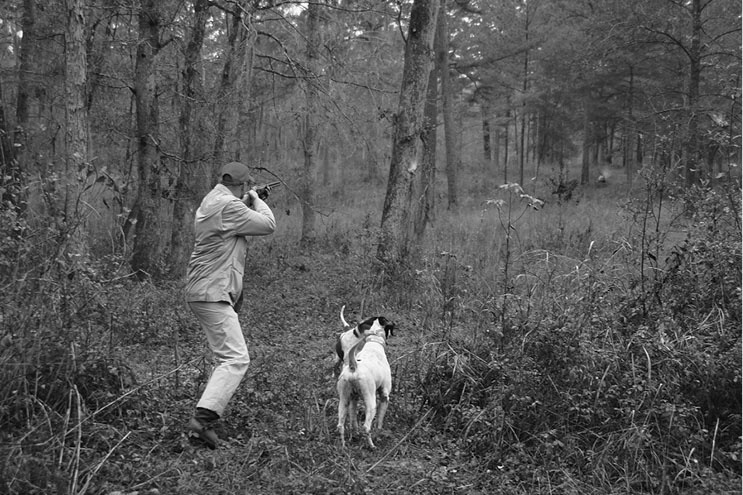

Dynamic motion: Three quail in the air, and the gun and the shooter in motion. Only the pointer is frozen.

Dynamic motion: Three quail in the air, and the gun and the shooter in motion. Only the pointer is frozen.

In order to know what kind of shotgun will work best for you, it is important to understand how a shotgun is normally used. The most important single fact is that a shotgun is used primarily for shooting moving targets. It is a dynamic weapon and, in use, the target, the gun, and the shooter are all in motion.

A shotgun does not have fixed sights. Although there may be various arrangements of beads and ribs along the barrel that are intended as sighting aids, the shooter does not consciously align them with the target before pulling the trigger. Instead, the eyes watch the target while the hands guide the shotgun to it, just as you might point your finger at a flying bird.

As with most things to do with shotguns these days, there are exceptions. Tactical guns often have rifle-like sights, as do shotguns intended for big-game hunting and that use slugs. Historically, however, and this is still the case today, most shotguns are used for moving targets, whether they are game birds, running rabbits, or clay pigeons.

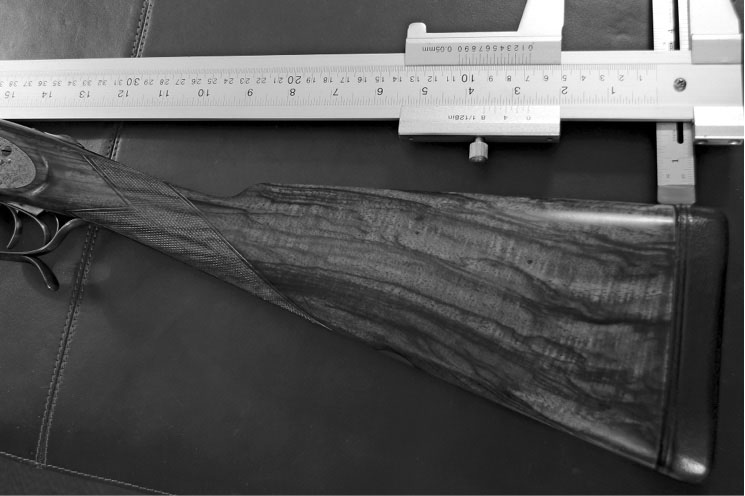

The stock of this Galazan A-10 Sporting Gun is adjustable for drop at comb, as well as length of pull.

Photo by John Giammatteo

The use of shotguns with slugs or buckshot, either for self-defense or specialized hunting as for deer, is more akin to rifle shooting than it is to conventional shotgun use. Since most people starting out with a shotgun want to shoot some sort of flying target, it is important to understand this, in order to know what to look for in a shotgun.

The English, who have taken both wingshooting and the making of shotguns to the level of fine art, place great emphasis on “fit.” They believe a shotgun should fit the shooter in a manner that ensures the eyes, hands, and gun barrel are aligned properly in order to hit a flying target consistently. Obviously, a gun that is the right size for a stout, six-foot man with long arms will not fit a thin, five-foot woman with shorter arms and small hands.

In America, most shotguns are mass produced in standard sizes, and shooters have adapted themselves to whatever gun they happen to have. At various times, however, some manufacturers have produced what are called “women” and “youth” models. These guns will be lighter, with shorter stocks and barrels.

The most important dimension in shotgun fit is the length of the stock. Measured straight back from the center of the trigger to the center of the butt, this is called “length of pull” (LOP). Typically, a gun will have a LOP of 14 to 14⁄12 inches.

The next important dimension is “drop.” If you lay a straight edge along the barrel and extending out over the buttstock, and measure the distance down from the straight edge to the upper edge of the stock at the butt, you determine the drop. How much or little drop a stock has determines whether the eyes are high or low and, as a result, whether the gun shoots high or low in relation to where the shooter is looking. There are further refinements of measurement, including bend to left or right (cast-on or cast-off), according to whether the shooter is left- or right-handed, but pull and drop are the two most important. Anyone buying a new gun can expect to get more or less standard dimensions to which the average person can adapt, but the buyer of a used gun should be careful to ensure the stock has not been altered (cut off, lengthened, or bent to any degree), thereby making it unsuitable for him.

At the upper levels of pricing, guns costing $10,000 and more are usually made to the custom dimensions of the buyer. These dimensions are determined by having measurements taken by a qualified shotgun fitter. Like a tailor measuring you for a suit of clothes, a shotgun fitter uses a gun with an adjustable stock (called a “try gun”), and watches as you shoot, making adjustments here and there to move the pattern to where it is desired. When you are shooting well with it, he measures the stock, writes down the dimensions, and there you have the ideal dimensions for a gunstock fit to you.

You cannot be measured for a gun in any meaningful way by someone in a gun shop with a tape measure, nor by filling in the blanks on a chart of body measurements, nor by employing such folk lore methods as seeing if a gun held in one hand will fit into the crook of your arm. A proper shotgun measurement takes a couple hours on a range, requires a hundred shots, and costs anywhere from $250 to $400. If you are spending thousands on a gun, this is a good investment; in fact, it hardly makes sense not to do it.

Even if you have no plans to order a custom-fitted gun, knowing your ideal shotgun dimensions will help in buying a used gun or adapting an existing gun to your requirements. This can be done by bending the stock, adding a recoil pad, or moving the trigger. If you have a competition gun with an adjustable stock, you can easily alter it to your own measurements.

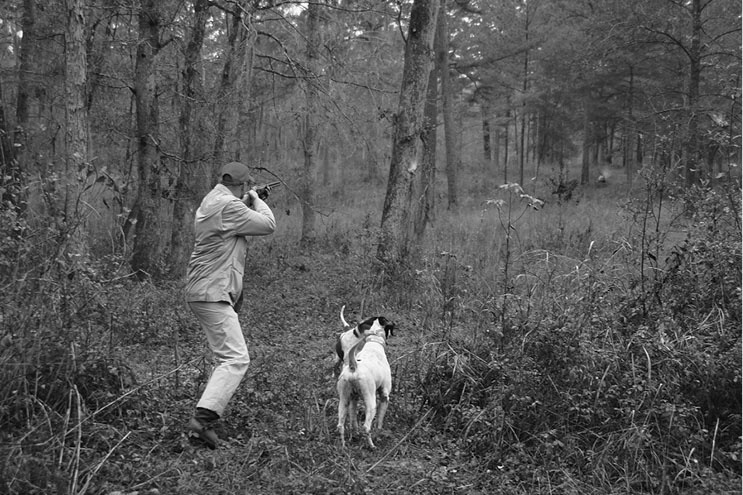

A collection of stock-measuring tools at the Holland & Holland shooting grounds outside London. Some are a century old.

In the early days, London’s fine gunmakers often made their own tools and instruments, to the same quality as their guns. This is a gauge for measuring length of pull.

The interesting thing about shotgun fit is that you need to learn to shoot reasonably well before you can really be fitted for a gun. This means most of us will start out with a gun of standard dimensions — and the vast majority will shoot nothing else throughout their lives. Many will do so quite happily, downing birds and dusting clays. The truth about shotgun fit is that it is not quite so important as its proponents would have us believe, but it is far more important than we are told by those who say it simply doesn’t matter.

For the beginner, a gun that is close to a proper fit is good enough to learn with. A gun that obviously does not fit, however, is a problem. Such a gun will be difficult to shoot, tough to learn with, and may impart a flinch or bad habits that will later be almost impossible to shake. For this reason, anyone setting out to learn to shoot a shotgun should seek the assistance of a good instructor, who will make sure he or she starts out with a suitable gun that fits, at least well enough, and learns to use it properly.

This is the aspect of shotgun shooting that is impossible to over-emphasize. Like driving a car, it is best to learn from a qualified expert. No matter how good a shot your father or brother may be, that does not mean he knows how to teach his skills to someone else. For girls and women especially, learning from a stranger is almost always easier and more productive than learning from a husband or relative.

Shooting a shotgun is an art more than a science, although science certainly enters into it. Unlike rifle shooting, where factors like bullet drop and target distance can easily be measured and allowances for bullet flight and distance defined in pure numbers, shooting a shotgun is a matter of feel — and no small degree of instinct.

Take three top-notch shotgunners and ask them how they do it, what they see when they pull the trigger, and you may get three widely differing views. On a crossing bird at 30 yards, one may say he leads the bird by six feet, another will say three, and the third may insist he shoots straight at it with no lead at all. Yet all three drop the bird. How can this be? The answer is that what we think we see and how we think we react may be quite different than what we actually see and do with a shotgun in our hands.

Shooting a shotgun is a dynamic process of movement: The target, the shooter, the gun, and the shot charge are all moving.

In England, shooting instruction begins at an early age. The gun is scaled down to properly fit these very young shooters, a very important consideration in learning to shoot.

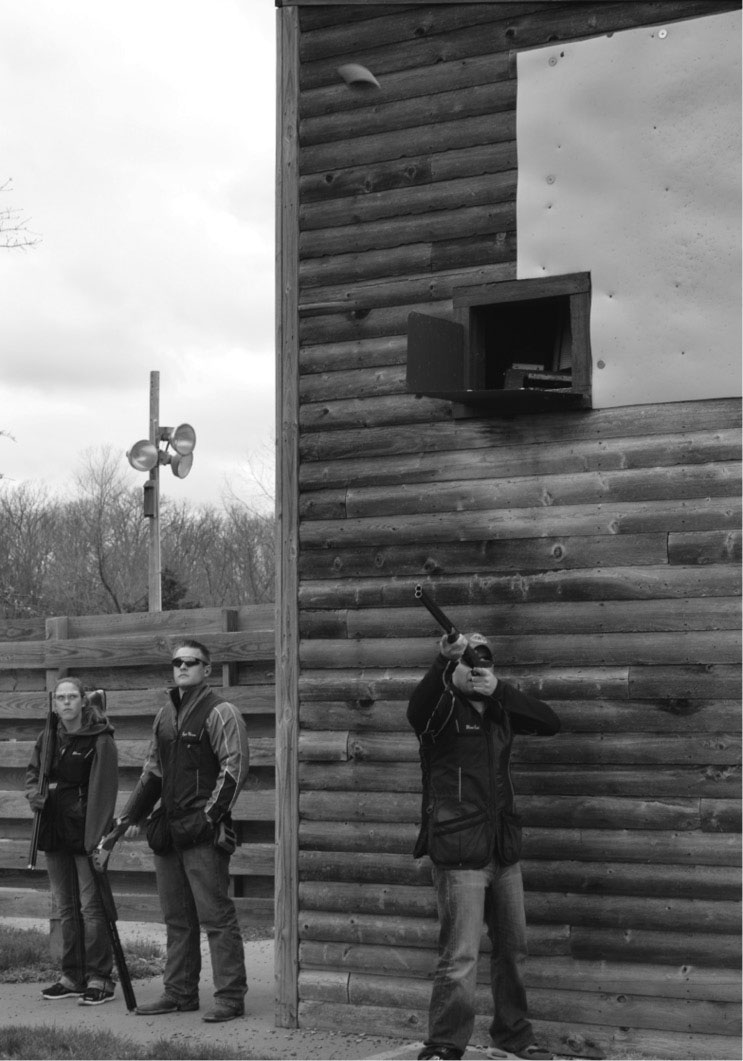

Good form with a shotgun, demonstrated by competitive shooter Alison Caselman. Both eyes are open, gun is properly mounted, her leading hand is well forward, and she’s leaning into the shot but is well balanced. The stock of her Blaser F3 is adjustable to give a perfect fit.

Checking shotgun fit: The height of the comb determines the height of the shooter’s cheek and eye in relation to the gun and impacts where the shotgun shoots versus what the handler is seeing (either too high or too low).

Simple arithmetic dictates that, if a charge of shot leaves the muzzle at 1,200 feet per second (fps), it will take a thirteenth of a second to travel 30 yards. If a pheasant is crossing in front at 30 yards, flying at 30 miles an hour (about 44 fps), then the pheasant will have travelled about 31⁄2 feet between the pulling of the trigger and the time the shot reaches him.

Since a shot pattern comprised of an ounce of shot and fired from a Full-choke barrel is only about 30 inches in diameter at 33 yards, the shooter has some leeway, but not much. The shooter needs to lead the bird by at least 31⁄2 feet if he hopes to center the bird in his pattern. Yet some shooters say they lead by twice that amount, while others say they give no lead at all.

The explanation for this anomaly lies in the mysterious epicenter of shotgun shooting known as “swing.” Like a batter in baseball swinging a bat to hit a moving ball, the shotgunner is swinging the gun in order to release the shot to intercept a moving target. If the swing stops or slows or speeds up too much, the result is a miss.

Swing, with a shotgun, depends on many factors, of which fit is just one. Another is weight and a third is balance. Experienced shotgunners take all of these into consideration, when choosing a new gun. Like fit itself, though, the exact weight and balance that are right for you cannot really be determined until you have some experience as a shooter.

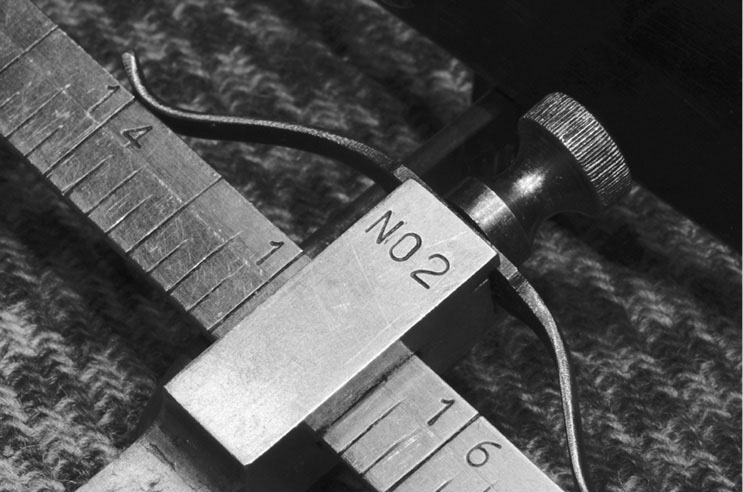

Skeet shooting: At station seven, Alison is positioned to take the bird, which has just left the low house. The other shooters are watching where they expect the bird to be broken.

Still at station seven, Alison has swung around to intercept the incoming bird from released from the high house and crossing the field to her right. Her relaxed stance allows her to pivot at the hips and swing comfortably.

The blur at the top of the wood clay house is a clay pigeon leaving the high house at skeet station No. 1 and moving nearly straight away from the shooter. The shooter has a good, relaxed stance, his weight on his leading foot.

Measuring the drop of a stock at heel. This combination gauge also measures length of pull, as well as drop.

Length of pull is the distance from the trigger (front trigger, in the case of double-trigger guns) to the center of the butt. This is the single most important dimension in shotgun fit.

A good instructor will ensure that you start out with a gun that is appropriate to your size, shape, and strength, whose recoil will not hurt you, and with which you can reasonably expect to hit something, if your eyes are in the right place, your hands follow your eyes, and your body and arms swing through. That’s all it takes.

Sounds easy, doesn’t it?