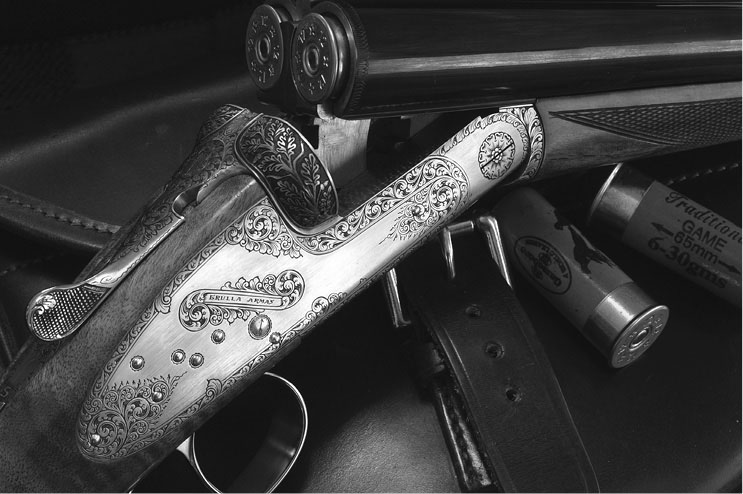

This is a Grulla Armas Windsor Woodcock, a light, 12-gauge game gun custom-made in the Basque Country of Spain.

This is a Grulla Armas Windsor Woodcock, a light, 12-gauge game gun custom-made in the Basque Country of Spain.

Over the past 500 years, shotguns have been made in every conceivable configuration. In addition to the early muzzleloading guns, there are single-shots, double-barrels (with barrels aligned either vertically or horizontally), multi-barreled and combination guns, and guns that are operated by levers, bolts, or slides, as well as semi-automatic actions that operate themselves, powered either by redirected gases or their own recoil.

In America today, we commonly use five types: singles, doubles (side-by-sides and over/unders), pumps, and semi-autos. Not surprisingly, some are favored for one type of shooting and some for another. Guns have specialties, just as shooters do.

Some guns are seen as cheap, others expensive. Some are traditional, others modern. Some are fast to use, some slow. As with most things to do with shotguns, however, every such statement ends with the word “but ….” There are exceptions to everything. The single-shot shotgun can be the cheapest (and most cheaply made) gun imaginable, yet some beautiful and very expensive trap guns are single-shots. Similarly, you can buy a knockabout side-by-side for $500, or spend $100,000 for a custom-built English gun.

This is an Ithaca Single-Barrel Trap Gun, circa 1921, the most famous and longest lived of the American single-barreled trap guns. It was produced in one form or another, until 1991.

A Holland & Holland side-by-side with detachable sidelocks. This is certainly at the higher end of the cost spectrum.

The famous Anson & Deeley boxlock, as used by P. Webley to create this classic English double.

Of the new guns you see at a shooting range today, the majority are either semi-automatics or over/unders, and either of these is a fine choice for an all-around gun. The side-by-side, once the dominant design throughout the world, has become largely a niche gun, displaced by over/unders in many applications, and America’s traditional favorite, the pump gun, is being increasingly crowded out by semi-autos.

The typical “farm boy” gun is a single-barreled single-shot that is hinged at the breech and breaks open for loading. In days gone by, many different makers produced such guns, and these firearms sold for a few dollars. They were inexpensive, simple to make, reliable in operation, and durable to a fault. They could be found in all gauges, in different barrel lengths, and with varying degrees of choke. Generally, such guns are light for their gauge, which means they kick like a mule, but, for a gun to keep behind the henhouse door, they were quite acceptable.

At the other end of the single-shot scale is the expensive trap gun. Trapshooting is a sport of breaking clay pigeons, a game that grew out of the original live-pigeon shooting, in which birds were released from actual traps. Betting was heavy in that sport, prize money was big, and serious trap shooters were prepared to pay a high price for a gun that helped them win. Out of this grew the single-barrel trap gun, highly refined and beautifully made. These were manufactured by every high-end gun maker in the world, from Italy to England to the United States. Here, the most famous (and the longest lived) was the Ithaca.

The demands on a single-shot are very simple. There is no need for selective ejection, and most trap guns do not have a safety. For this reason, gun makers can and have been very fanciful in their designs. The most far-out of all time was the Ljutic Space Gun, marketed in the 1980s. It threw out every theory of fit and shootability, and the result was a gun that looked like a crowbar with handles, but, by all accounts, shot quite well. Today, Ljutic makes a more conventional drop-down single-shot with a frame that resembles a modern semi-auto. There are other small trap gun makers still in business in the United States, and their guns typically sell in the range of $8,000 to $20,000.

Having said this about single-shots, there really isn’t much else to say. They are still made, although not in such great numbers as before, and the cheap models are exclusively utility guns. As for trap shooters, today they are more likely to go to the range with a good Italian over/under, since those are also usable for the game of doubles trap and can be fitted with a separate single barrel if that configuration is preferred.

The futuristic receiver of the Browning Cynergy over/under.

Single-shot guns have also been built on other actions, such as the W.W. Greener using the Martini-Henry, and there are some single-shot bolt-actions. These are rarely seen and no longer made. Some single-shot guns were even built on converted Mauser K98 military actions, but these were utilitarian, at best.

The side-by-side shotgun occupies a unique place in history, being directly descended from the flintlock and with an ancestry that stretches back centuries. The side-by-side was perfected before any of the other major styles were thought of and, for many years, it was the dominant gun in every country that made or used shotguns.

The over/under, pump, and semi-auto were not designed to improve on the side-by-side, so much as to allow mass production, reduced costs and, to a limited extent, increase firepower. (This last requirement is largely negated in wild game shooting today, with most jurisdictions having a capacity limit of three shots.) The major strike against the side-by-side today is that its unquestioned virtues — light weight, exquisite balance, and a mechanism that performs flawlessly and effortlessly — can only be achieved with a great deal of highly skilled hand labor.

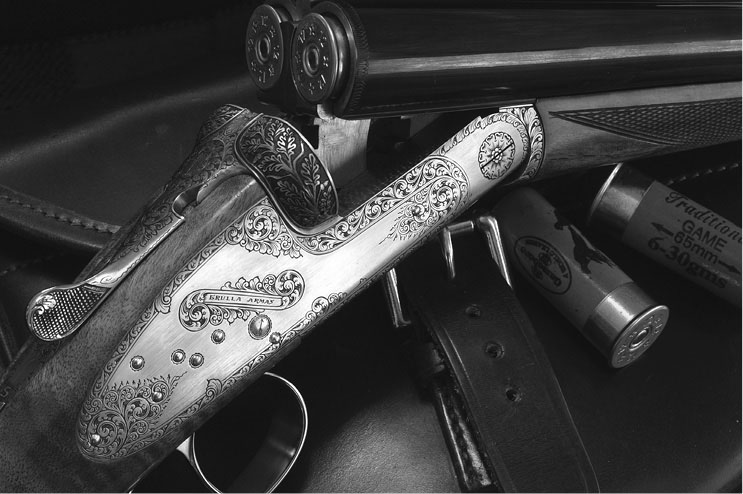

When carried “broken,” a double gun (either side-by-side or over/under), is seen to be safe even at a distance.

As the name implies, the side-by-side has two barrels aligned horizontally. Like the single-shot, it is hinged at the breech and breaks open for loading. A century ago, the side-by-side was the preferred gun of serious shotgunners, and the very best ones were made in London, by makers such as Holland & Holland, Purdey, and Boss. Fine side-by-sides were (and are) also made in Belgium, Italy, Germany, and Spain. European shotguns of this type were intended primarily for shooting driven game — birds that are flushed over a line of waiting guns by a group of beaters. Holland & Holland and Purdey are still in business, in London, and will make you a custom shotgun for $80,000 to $100,000. It will have the finest workmanship, inside and out, with a stock carved from stunning walnut, extensive engraving, and fit and finish second to none.

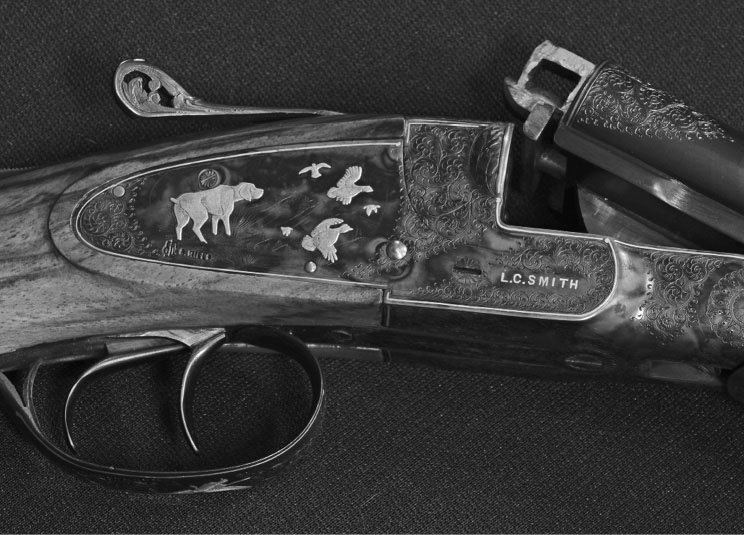

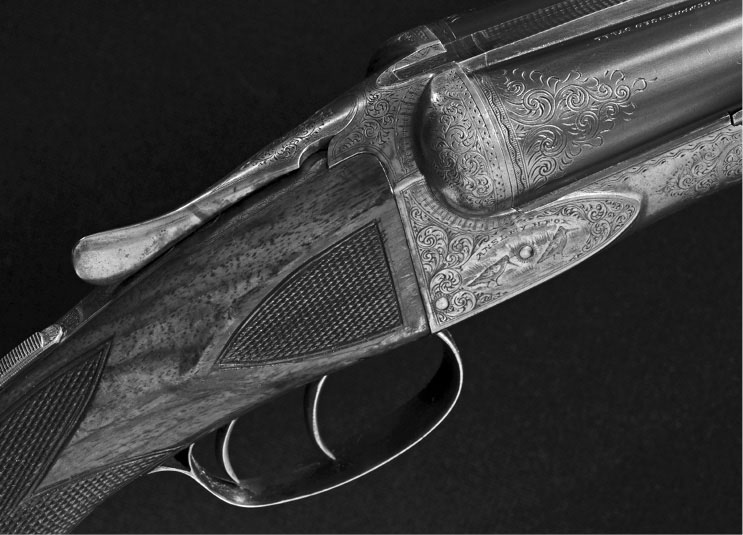

In the United States, famous names in double guns included Parker, Fox, Ithaca, L.C. Smith, and Winchester. Most of the great double-gun makers went under around the time of the Great Depression or just after the Second World War, driven out of business by rising costs and changing tastes. The undoubted virtues of a good double could not compete with the one overriding virtue of a pump gun: low cost.

Side-by-side doubles are light and carry comfortably either open or on the shoulder.

What are the advantages of a double? A traditional side-by-side, made to measure, offers exquisite balance combined with the weight and gauge desired and an instant choice of chokes from two barrels. Beyond that, arguments abound as to whether the over/under is better than the side-by-side, for whatever purpose, or whether you are really better off with a pump or semi-auto.

Much of this boils down to nothing more than individual taste, with everyone having biases and preferences. Generally, however, many expert shooters have concluded that the side-by-side has an edge, when it comes to reacting to the unexpected, as in wild-game shooting, while the over/under has an advantage shooting predictable targets, such as those found in trap or skeet.

Any break-action gun has one undeniable advantage, and that is safety. When the gun is broken, not only can it not be fired, it can also be seen to be safe from a distance. This is very desirable when shooting in a group, whether it is driven grouse in Scotland, or in a party of pheasant hunters in the Dakotas.

Another advantage of the double is its silent operation. A side-by-side double with extractors can be opened, loaded, closed, and pointed at a target in near absolute silence. It can also be opened and unloaded without making a sound, or carried open over the arm (and absolutely safe), then be closed and ready to fire in an instant, with almost no noise at all. This can be critical in hunting wary birds such as wild turkeys, and is even useful to avoid spooking well-educated, late-season pheasants.

Modern side-by-sides are divided into two main types, the sidelock and the boxlock. Of the two, the sidelock is the more aristocratic action, and certainly more expensive. There are both historical and technical reasons for this, and while the arguments have raged for almost 150 years as to which is better, the consensus is that the sidelock is superior overall by a number of measures. At the same time, it costs as much to produce an ultra-fine boxlock as it does a comparable sidelock. But most buyers are unwilling to pay as much for a boxlock as for a sidelock — or, to put it another way, if they are going to spend big money, they might as well get a sidelock. In modern terms, most “affordable” guns are boxlocks, while the “fine” guns are sidelocks.

The Galazan RBL, a modern boxlock side-by-side based on the English Anson & Deeley action and manufactured by the Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Company.

The sidelock is directly descended from the hammer gun. The only real difference is that a sidelock has its tumblers (hammers) on the inside of the lock plate, while the hammer gun has them on the outside. These lock plates can be readily removed for cleaning and adjustment. The plates themselves afford more metal surface for elaborate engraving, although that is strictly a secondary consideration, a side effect rather than cause. The Holland & Holland, Purdey, Boss, and Woodward actions, the most famous names in London gun making, all are sidelocks.

The London connection played no small part in the sidelock’s aristocratic image. When the centerfire cartridge was developed, in the 1860s, it became apparent to a number of English gun makers (and we are concentrating on England, because that is where the major developments took place), that there was really no need for conventional hammers at all. The first really successful attempt at a so-called “hammerless” design was by a gun maker named Theophilus Murcott. It was patented in 1871. I say so-called, because all side-by-sides have hammers, it’s just that some are internal and others external.

Murcott was from London, the home of the “bespoke” or custom-made, high-quality shotgun. In England, there were also military and mass-production gun makers, mostly in the industrial city of Birmingham. There was a great rivalry between London and Birmingham, a fact that played a prominent part in the relative images of sidelocks and boxlocks.

The detachable lock of the Galazan A-10 sidelock over/under.

One of the preeminent Birmingham firms, then as now, was Westley Richards. In 1875, two Westley Richards employees, William Anson and John Deeley, patented one of the most famous inventions of all time: patent #1756, the Anson & Deeley boxlock action. In this design, the entire lock mechanism was placed inside the gun’s frame. It was then given the name “boxlock,” because of the square, boxy appearance of the action. Since 1875, the Anson & Deeley action has been produced in the tens of millions and is by far the most common — and still the finest — boxlock action in existence. Westley Richards naturally specialized in boxlocks, thanks to its two employees, and the boxlock became associated with working-class Birmingham, while the sidelock held sway in aristocratic London.

That, of course, oversimplifies by a wide margin. Sidelocks were also made in Birmingham, and boxlocks in London, some good and some better in either case. Broadly speaking, the modern sidelock, in its perfected form, is slightly stronger than a boxlock, has a better trigger pull, and is, theoretically, safer, because it is fitted with a secondary safety sear. This is a mechanism to catch the tumbler if it is accidentally jarred loose. The standard Anson & Deeley has no safety sear, although the conventional safety mechanisms found on both types are essentially the same.

Another feature found on some sidelocks is the “self-opener.” This is an integral part of the Purdey action (designed by Frederick Beesley), as well as Beesley’s later patent, which was manufactured largely by Charles Lancaster. Holland & Holland developed a self-opening mechanism that is standard on its Royal. A self-opener uses spring power to assist in opening the gun and allow faster loading, but it is more than a convenience. A gun with a self-opener lasts longer, because the constant tension applied to the action reduces wear from jarring and recoil. This is one reason for the legendary durability of Purdey guns. While self-openers such as the separate H&H design can be fitted to boxlocks, it is not common any more than the fitting of safety sears.

The Galazan RBL, a modern boxlock double gun, manufactured by Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Co.

The Galazan A-10 sporting gun is equipped with auxiliary weights, for adjusting balance.

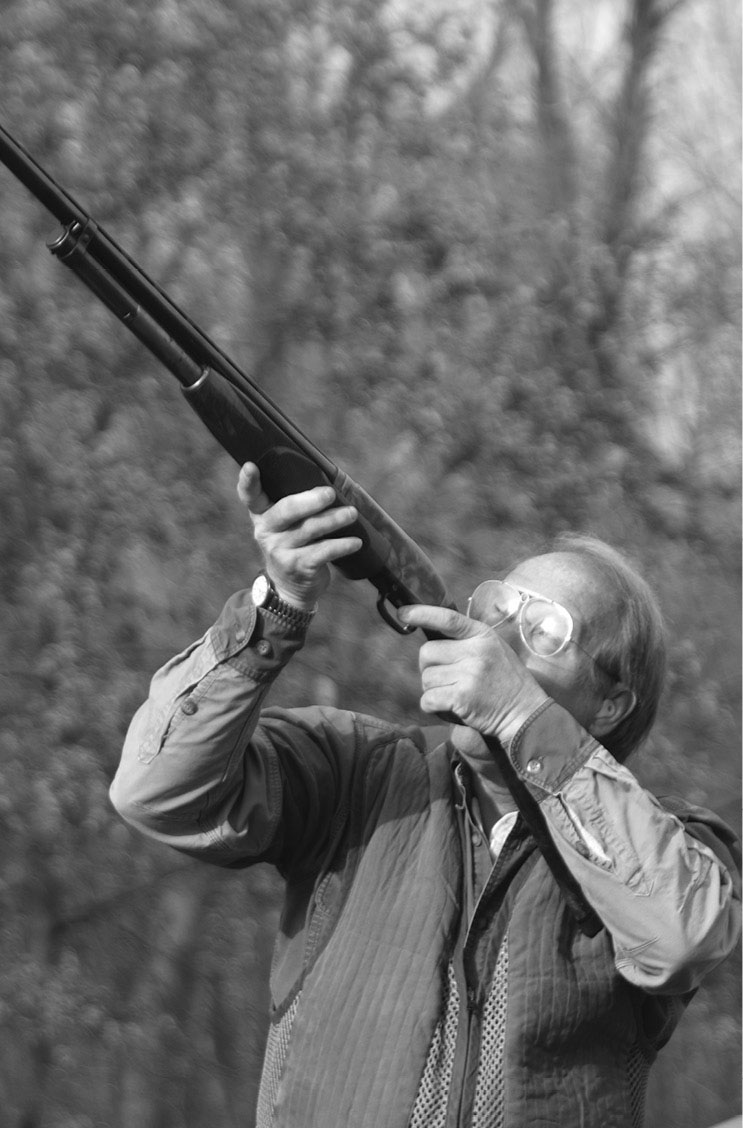

The author hunting quail in Alabama, shooting a Charles Lancaster sidelock double, circa 1907.

Photo by J. Guthrie

The author with a James Woodward hammer gun and bobwhite quail.

Photo by J. Guthrie

A lock plate from a Charles Lancaster sidelock. The tumbler, spring, and related mechanism are all fastened to the plate, which can be removed for cleaning and adjustment.

If one can apply a general rule to sidelocks and boxlocks, it is this: A good boxlock is better than a mediocre sidelock, because the advantages of either, slight to begin with, depend to a great extent on the quality of the workmanship. Some very poor sidelocks have been produced, as have some extraordinarily fine boxlocks.

In America, the high-quality side-by-sides were, with one major exception, boxlocks, although none were built on the Anson & Deeley design. The hammerless Parker, Fox, Ithaca, and Winchester 21 were all boxlocks; only the L.C. Smith was a sidelock. The Smith sidelock lacks a safety sear and is, by English standards, a rather crude and inelegant mechanism overall. The other designs came about largely from a desire to circumvent the Anson & Deeley patent.

If the “not invented here” bias affected the exchange of technology between London and Birmingham, it was an even greater factor in relations between England and America. Through the 1870s, America’s demand for high-quality shotguns was filled largely by English companies, notably W&C Scott and Sons, and W.W. Greener, both of Birmingham. Exporting to the U.S. was a major source of revenue, and patents were filed and enforced on both sides of the Atlantic. American gun makers sprang up to compete with the English guns that had such a sterling reputation, and patent infringement or the paying of licensing fees was a significant concern.

It is sometimes forgotten that there was a great deal of back and forth between the English and American gun trades through the mid-1800s, from Samuel Colt and the revolver to Greener supplying shotguns to Wells Fargo. Industrialists visited each others’ factories and studied methods and designs; at one point, the English purchased American gun making machinery to modernize their own production. No wonder the design and production of side-by-side guns in the two countries are so closely related!

In the 1980s, as interest in double guns revived, attempts were made to resurrect some of the best of the old names. The Parker Reproduction was manufactured in Japan, and, later, Galazan began making the A.H. Fox guns once again. Ithaca also came back, in a short-lived venture called Ithaca Classic Doubles. For years, the only surviving original was the Winchester 21. As Winchester went through cycles of corporate financial grief, the 21 hung on by its teeth, retained purely as a prestige item.

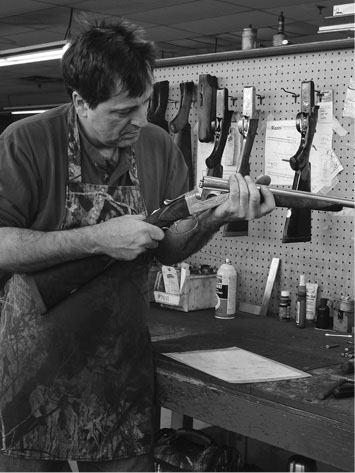

While the English double gun survives in both London and Birmingham, the American double survives in Connecticut, with Tony Galazan’s Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Company (CSMC). The Parker, Fox, and Winchester 21 are all manufactured by CSMC, at Galazan’s factory in New Britain. There he employs a hundred workers, including some of the country’s most skilled craftsman, and they work with advanced, computerized machinery. Galazan also makes his own boxlock shotgun, the RBL, in a wide variety of configurations, from a short-barreled slug gun with rifle sights to a long-barreled, heavy sporting clays guns and everything in between.

A Winchester Model 12 pump shotgun, this one in 16-gauge. The Model 12 is considered by many to be the finest pump gun ever made.

None of these guns is cheap — far from it. You could buy 10 pump guns for the price of a new double, and while the used gun market for doubles has its ups and downs, the general, inexorable trend is up. To an extent, the double shotgun today is a prestige item. It is also a connoisseur’s gun, with clubs and organizations devoted to the study and use of older guns. If you consider them in terms of a lifetime investment, these guns actually need not be expensive, a the best doubles were made to be shot a lot and last a long time.

Jack O’Connor, long-time shooting editor of Outdoor Life, was a great double-gun admirer and owned, among others, several Winchester 21s and five or six custom-built AYA and Eusebio Arizaga guns from Spain. Writing in the 1960s, a time when doubles were at a low ebb, O’Connor noted their ease of handling, their light weight, the sheer joy of operating a fine mechanism, and the certain indefinable something that comes with handling a fine double. He once wrote wryly, as only he could, “The side-by-side double is seen as the ‘gentleman’s gun’ — although I doubt that’s the only requirement.”

• • •

There is a distinct subdivision of the side-by-side: the hammer gun. The hammerless side-by-side as we know it today grew out of the hammer gun, which, in turn, is descended directly from pinfires, percussion guns, and flintlocks. Although the hammer gun was largely superseded by hammerless designs, starting in the 1870s, gun makers continued to produce them until the 1920s. A few are still made today.

The Ruger Red Label in 28-gauge is a light, handy game gun.

A collector’s rack of Winchester Model 12 pump guns.

In the 1990s, hammer guns enjoyed a revival of interest in the United States, and prices for vintage guns shot up. Today, the peak has passed, although there is still a steady demand for hammer guns from competitors in such period-specific competitions as Cowboy Action shooting and the Order of Edwardian Gunners (known as “Vintagers”). There is also a small coterie of devotees who simply enjoy using hammer guns for both game shooting and clays.

The hammer gun has some distinct advantages even over hammerless doubles, and this is the reason they hung on long after they were obsolescent. One is that they are extremely rugged, reliable, and safe. They can be manufactured more cheaply than a hammerless gun, and tens of thousands were produced in England, for export to India, Africa, and the other colonies. The mechanism itself is considerably simpler than a hammerless gun and, therefore, less likely to malfunction; if it does malfunction, it is easier to repair.

There is another point about hammer guns, and that is that even after the arrival of boxlocks and sidelocks, some of the finest game shooters in the world continued to favor external hammers. Both Lord Ripon (considered the best game shot the world has ever seen), and King George V (generally conceded to be one of the top four or five shots in England) used Purdey hammer guns to the end of their days.

A gun with rebounding hammers (patented by John Stanton, in England, in 1867), requires no safety mechanism and can be seen instantly to be cocked or not. As well, there is no internal cocking mechanism required. One should hasten to add that hammer guns have been made with both safeties and internal cocking mechanisms, but these are the rare exceptions.

As with any gun, using a hammer gun safely and effectively requires education and practice. Once acquired, however, facility with a hammer gun becomes second nature, and many enthusiasts refuse to use anything else. They become accustomed to thumbing back one or both hammers as required, breaking the gun with the hammers cocked for safe carrying, and letting the hammers down with the gun broken, absolutely the safest method. The hammer gun offers the option of carrying a gun with rounds in the chambers and the hammers safely at half cock. Altogether, the hammer gun requires not only a few different skills, but a distinctly different attitude than a modern conventional gun of any description. In operation, it is also the quietest gun ever designed, anywhere.

Remington Model 31 pump guns.

A Model 12 lover, this is Ralph Gates, of Missouri, with his favorite competition Model 12.

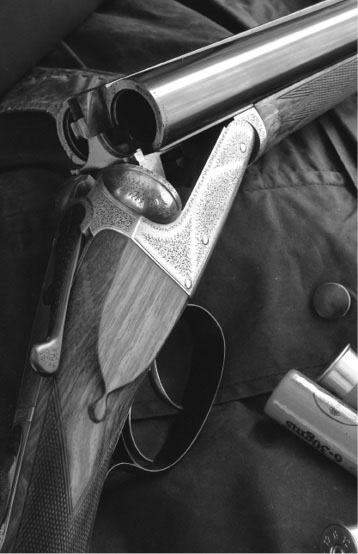

The author shooting a Winchester Model 12 (16-gauge). A pump can be operated more quickly than a semi-auto.

Photo by Ralph Gates

While the over/under is usually considered more modern than the side-by-side, in fact, the first doubles were over/unders. The side-by-side became dominant largely because it was easier to configure a hammer mechanism to fire left and right barrels than it was upper and lower.

When guns went hammerless, beginning in the 1870s, makers became interested in over/under designs once again. These gained favor for a number of reasons, one of which was the fact that the shooter looking down the barrel sees only one barrel. Makers like Browning, inventor of the famous Superposed, pushed this idea until it became an article of faith.

Regardless the reasons, the over/under is, today, by far the dominant form of the modern double shotgun, with very fine ones made in England, Germany, the United States, and Italy. The over/under owns the trap, skeet, and sporting clays world and has made serious inroads with live-pigeon shooting.

It is possible to buy a Fabbri over/under from Italy, made to measure for $200,000, or an off-the-shelf American Ruger Red Label for $2,000. There are good Italian over/unders (and some very poor ones), selling for $3,000 to $30,000 and up. In other words, there is something for almost any serious shotgunner, regardless the bank account.

Like the side-by-side, the over/under has the great advantage, when used in groups of shooters, of being instantly seen as “safe” when broken open and carried over the arm. With two barrels, you can have two different chokes and an instant choice of which one to use. The guns can be light or heavy, depending on the use, and well balanced. Over/unders also lend themselves to having multiple barrel sets — different lengths, chokes, configurations, even different gauges — which can be fitted to the same frame. Indeed, a person desiring to own just one gun but shoot a wide variety of disciplines is better off with a good over/under than with any other type of shotgun.

Doves in Argentina, where they are so numerous they are a serious agricultural pest, and where they are shot by the thousands. The favorite gun used by visiting shooters in the ultra-dependable Benelli 20-gauge semi-auto.

Argentine secretario Angel Mameli, a skilled loader and gun handler, keeps his Benelli 20-gauge guns functioning flawlessly through thousands of shots fired in each day.

The modern era of the over/under began, in 1909, when John Robertson, then the owner of Boss & Co., one of London’s preeminent gun makers and designers, patented his design. Boss’ great rival at the top of the London gun making tree, James Woodward & Sons, followed, in 1913, with an over/under of its own.

Prior to Boss and Woodward, one of the greatest strikes against the popularity of the over/under had been the depth required of the frame to stack two barrels atop one another, plus the lugs beneath for pivoting and room to accommodate a locking mechanism. Boss solved this by rotating the barrels on a wide radius milled into the sides of the frame, while Woodward used a system of trunnions similar to the age-old artillery pattern. Today, every modern over/under uses one or the other or a variation thereof.

The other major problem with over/unders was the extreme angles at which the strikers needed to be placed in order to be struck by conventional tumblers. This led to soft, glancing blows and chronic misfires (a problem that exists to this day, in some designs). The German company Blaser solved this on its superb, current day F3 shotgun by eliminating tumblers altogether, instead using parallel, spring-powered strikers. These strikers are tripped by a trigger mechanism that is the best in the world, one combining a perfect trigger pull with lightning-quick lock time.

Blaser was not the first to do this — Rottweil used a similar system on its short-lived over/under in the 1980s — but Blaser perfected it. The company, which employs the finest computerized machinery at its plant in Isny, in the Bavarian Alps, has also perfected the concept of complete interchangeability among parts, allowing the owner of an F3 to buy additional barrel sets, buttstocks, and fore-ends and interchange them without gunsmithing or special fitting. This is a goal that had eluded fine gun makers for more than a century. Although parts can certainly be made interchangeable, in the past, it could only be achieved by allowing excessive tolerances, which gave sloppy fits and short service lives.

The dominant competition over/under today is the Italian Perazzi, which initially made its name, in 1968, with gold medal wins at the Mexico City Olympics. Its guns have crowded the winner’s circle ever since. Other great names in over/unders include Beretta, grandfather of them all, and Antonio Zoli, in Italy, as well as Krieghoff, in Germany. The Krieghoff is a German adaptation of the only great, early, American-made over/under, the Remington Model 32.

While Italian and German over/unders dominate the field, Tony Galazan’s Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Company is fighting back with two recent models, the A-10 sidelock and the Inverness boxlock. These guns begin in the $5,000 to $10,000 range. Galazan still offers its own Galazan over/under, first produced in the early 1990s and patterned on the Boss. It is a gorgeous gun, with a price to match.

As with side-by-sides, over/unders can be made with either sidelocks or boxlock designs, although most of the so-called boxlocks are really trigger-plate mechanisms. The Woodward and Boss over/unders are both sidelocks. The original notable German design, the Merkel, uses a trigger-plate action called the “Blitz,” which established a worldwide reputation.

The Perazzi MX28B, a superb new over/under 28-gauge game gun, introduced in 2012. At $14,000, this “basic” gun is not inexpensive, but it is a beautiful shooting tool.

Recognizing the need to introduce American shooters to the joys of double guns at an affordable price, in 1977, Sturm, Ruger & Company introduced the Red Label over/under. It was styled on the Boss, in appearance at least, although it is a boxlock design. Two generations of American shotgunners have made their start with Red Labels. Many have graduated to more expensive doubles, while others have seen no reason to change.

John M. Browning’s last gun design was the Superposed over/under, a gun that was made in Belgium, from its beginning, in 1928, to its end, in the 1970s. With this gun, Browning undertook a marketing campaign that some describe as brilliant, others as cynical and misleading; everyone agrees it was effective. The campaign revolved around the concept of the “single sighting plane” as an alleged advantage in shooting. The idea was that, since the shooter could see only the top barrel, it is easier to aim that type of gun than it is a side-by-side. Catalog illustrations showed the single barrel alongside a double with wide, sharply defined, dark muzzles.

This campaign worked so well that the term “single sighting plane” is now chorused endlessly by proponents of single-barrel guns of all types, and many shooters who claim not to be able to shoot a side-by-side cite its lack of a “single sighting plane” as the reason. In truth, this makes no sense, for a number of reasons. First, in shooting a shotgun, you look at the target, not at the barrels. One barrel or two, the muzzle of your gun is a vague blur. Second, Browning’s sharply defined illustrations were inaccurate. When you look down the barrels of a double, even if you focus your eyes on the barrels themselves, they almost disappear because of light reflection off the radius of the polished steel. You do see the converging lines on each side of the rib, directing your eye to a very prominent bead that stands out like the Washington Monument. This is true even if the bead itself is the tiny, discreet brass pellet favored by London gun makers. Ignore the bead (as you should), and your eye is directed naturally out to where the target is. Conversely, a broad, cross-hatched or serrated rib atop a single barrel does not direct your eye anywhere in particular.

Leaving aside the question of sighting planes, how do over/unders compare with side-by-sides in other ways?

There are two practical features to consider. One is the distance an over/under must open to allow ejection and loading. This is called the “gape,” in gun making parlance, and, with an over/under, it is obviously much greater. This not only slows down the process, it can make loading awkward in confined spaces such as duck blinds, duck boats, and shooting butts. The long rotation required adds to the resistance, and it is much more difficult to make an over/under operate smoothly and effortlessly than it is a side-by-side.

The very best side-by-sides like the Holland & Holland or Purdey magnify this advantage with self-opening mechanisms or “assisted” openers. The Lancaster self-opening action, built on the 1884 Beesley patent, allows the shooter to hold two cartridges in his left hand and operate the top lever with his right thumb; the barrels spring open and eject the cartridges, two new ones are popped in, and the gun is snapped shut, ready to shoot again. No over/under is equipped with a self-opener that completely eliminates the use of the left hand to open them, something that is an enormous advantage, when you need to reload quickly.

Then we come to the various gauges and how well they adapt to either pattern. Broadly speaking, a 12-gauge side-by-side is much more sleek and graceful than any 12-gauge over/under. The most graceful over/under is the 20-gauge and, for a considerable number of shooters, their dream gun is a finely engraved Italian 20-gauge over/under. In 28-gauge, either style can be lovely, always provided they are built on scaled-down frames and are not merely 20-gauge guns fitted with 28-gauge barrels. The same is true of the .410.

In skeet shooting, where four gauges are used in registered competition, the over/under has cornered the market. As far back as the 1960s, over/under guns were offered with four sets of barrels, one in each gauge, allowing the competitor the enormous advantage of having one gun with one familiar action and trigger pull. Today, guns like the Blaser F3 take it several steps further, balancing the smaller gauge barrels with adjustable weights so that the gun feels almost identical regardless which gauge is being shot.

This is something no side-by-side has ever done or even attempted to do (although multi-barrel sets are common, and sometimes in different gauges). If you are game shooting with a 28-gauge, you want it to feel like a 28-gauge, otherwise what’s the point? But in competition, where weight is not an issue (and more weight is even desirable, for damping recoil), the over/under with multiple barrels wins hands down over every other type of shotgun.

A new Holland & Holland over/under.

The trunnions that were used to elevate cannon since time immemorial were the basis for the operation of the modern over/under. The idea was first used by J. Woodward & Sons, in 1913.

In American trap, the over/under can be used with a single barrel for 16-yard shoots, and an over/under barrel for doubles, again allowing the use of just one gun for two different disciplines. This ability of the modern over/under has all but killed the traditional single-barrel trap gun, although Browning’s BT-99, introduced in 1969, is still available and continues to have a loyal following.

The final point to consider with over/unders is weight. The average over/under weighs one to two pounds more than a comparable side-by-side. While a good 12-gauge English game gun weighs 61⁄2 to seven pounds, it is not unusual to find an over/under game gun at eight or 8⁄12. There are a number of reasons for this. One is that over/under buttstocks almost all have pistol grips — actually, they are bulkier in every way. They also employ a stock bolt to fasten the stock to the action, which adds ounces. The frames are heavier and fore-ends considerably bulkier, because of the need to wrap lots of wood around the barrels.

Holland & Holland over/unders incorporate its barrel selector in its safety catch. This is the most common design today.

Perhaps the major reason for the additional weight of an over/under is that their makers (except for Woodward and Boss, which were catering to a different market), have never had any need to try to reduce weight. They never needed to shave barrel walls meticulously, by hand striking, to perfect the weight and balance. Since it is easier and cheaper to leave parts bulky, and since engineers perceive that this will reduce breakage and make them safer, many over/unders have a bulky, clumsy feel to them. Still, a 20-gauge over/under can easily be built to weigh in the neighborhood of 61⁄2 pounds, ideal for a gun to be carried in the field and regardless of gauge.

This largely explains the great and growing popularity of the 20-gauge over/under. Combined with a three-inch chamber and the possibility of “duplicating” 12-gauge loads via the use of three-inch magnum 20-gauge shells, on paper, you have what appears to be a perfect compromise. It isn’t, of course, because no 20-gauge shotshell, regardless load and choke, can match the 12-gauge ballistically or for pattern quality. It’s those immutable laws of physics again. And the magnum 20 in a gun of that weight kicks like the very devil, which is why most people stick to standard 20-gauge shotshells, except for extreme circumstances.

Overall, the over/under looks set to continue edging the side-by-side out of the picture, except in the hands of some devotees. Today, there is even a perception that the side-by-side cannot hold its own in competition and, so, there are separate side-by-side categories set up in everything from “vintage skeet” to pigeon matches and sporting clays, just as there are small-gauge divisions.

Another view of the trunions that inspired the likes of the over/under shotgun. It was first used by Boss & Co., in 1909, and a variation by J. Woodward & Sons was brought to life in 1913.

There is also a perception that an over/under is somehow more durable than a side-by-side, and you will hear gun salesmen, trying to sell something else, condemning London side-by-sides as finicky or delicate. Nothing could be further from the truth. London guns are made to endure thousands of shots in a day, tens of thousands over a season, without malfunction and only regular cleaning and a once a year trip to the gun maker for a strip and clean. That is the reality of life in driven shooting, and Boss, Purdey, and H&H realize that very well. As an example, there is one documented case of a Boss side-by-side game gun used at the old Eley ammunition factory for routine testing. With nothing more than an occasional cleaning, the gun had fired an estimated 1.5 million rounds, when the factory closed down. That is durability. It is also the reason why hundred-year-old Hollands and Woodwards are in regular use today. There is a thriving market in century-old English side-by-sides, and the interest in them is for use in the field, not for collecting or wall-hanging.

For many years, the pump could lay claim to being the all-American gun. From the early models in the 1890s until today, every major manufacturer made one, and they were refined into guns that were handy, durable, and dependable.

Pump guns were used to win big-money trap matches, to shoot ducks and geese in rainy salt marshes, and to knock off foxes threatening the henhouse. They were used as trench guns in the Great War, and by police and prison guards. There is no use to which a shotgun can be put that the pump gun cannot handle.

Pump guns, many and varied. In the middle of a rack of Remington Model 31 game and competition guns rests an Ithaca Model 37 trench gun, identified by its quite short barrel and its ventilated cover. The versatility of the American pump gun is nearly unlimited.

The pump is a single-barreled repeater with its cartridges held in a tubular magazine under the barrel. Operated by the forward hand, the fore-end slides back and forth, using the magazine as a rail. It opens and closes the bolt, ejecting the empty hull and chambering a fresh round. Although pump guns have been made everywhere from Japan to Italy and Brazil, the design is predominantly American, as are the most famous models. These include the Winchester Model 12 (lamented in its discontinuation and highly collectible), and the current production champion, the Remington Model 870. The Model 870 replaced an earlier Remington design, the Model 31. Since 1949, the 870 has become the single most produced civilian firearm in history, with more than 10 million made by Remington and still going strong.

The third great American pump is the Ithaca Model 37. It is named for the year of its introduction, 1937, and was derived from a Remington patent of a Browning design that had expired. The Ithaca Model 37 thrived, even as Ithaca’s famous double guns were losing ground, and it is still in production today. The 37 loads and ejects through the bottom of the action, allowing a solid frame that is both strong and weatherproof. Its solid mechanism feels as if it is running on ball bearings.

Like the underlever on some double guns or the mechanism on a lever-action rifle, the basic pump mechanism is both intuitive and ergonomic. For a shooter, it is a natural movement. In effect, the shooter becomes part of the mechanism, which is activated by a combination of recoil and the natural retraction of the shooter’s forward hand, gripping the slide, after a shot is fired. As the slide is then pushed forward to chamber a new round, the leading hand is pushed toward the target, bringing the gun instantly into line for an accurate second shot.

This movement can be extremely fast. Tests have proven that a skilled shooter can fire more rounds, more quickly, from a pump gun than a semi-auto. Pumps are also simpler and more reliable, as well as extremely rugged, which makes them the ideal tactical and defense weapon.

The L.C. Smith was one of very few sidelock side-by-side guns made in the United States, and the most famous. It was manufactured in some very fancy grades.

The A.H. Fox double is an American boxlock gun.

Comparing the hinge system of two of the finest English over/unders. The Woodward (top) and the Boss. Both employ the trunnions first found on cannon, and variations on this method are used on virtually all modern over/unders.

The Browning Auto-5, shown both above and below, is one of the oldest, and certainly the most famous, semi-auto designs. It was introduced in 1900, and uses a long-recoil mechanism. In operation, there is the feeling of many parts moving, but devotees love them.

Just as a shotgunner who grew up shooting double guns prefers them for life, so, too, do pump gunners cling to their favorites and resist any pressure to move to more sophisticated or expensive designs. The great American pump gun is still in production, led by the Remington 870 (for sales) and the Ithaca 37 (for longevity). Combined with this, there are millions and millions of good used pump guns available for just a few hundred dollars. These guns represent the greatest single bargain in the world of shooting. A person shooting a well-made Winchester Model 12 from the 1960s need make no apologies to anyone.

A semi-automatic shotgun is one whose mechanism functions independently of the shooter. Such an action will chamber a round, eject an empty hull, and then chamber a new round, with no overt motion required from the shooter except pulling the trigger. The power to do all this work is provided either by the force of recoil, as in the very earliest semi-automatic designs, or by utilizing expanding powder gases to push a piston rod and move the breechblock.

Hand-fitting a new Winchester Model 21, at CSMC in Connecticut.

Over/under barrel sets, in progress at Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Company. Over/under designs lend themselves to machine production better than side-by-sides.

At CSMC, fine checkering is done by hand, but time is saved by laying out the pattern using a laser machine.

Although semi-automatics have been available for more than a century, they only really took hold after 1945. Since 1980, they have become the most common design found in a wide variety of applications. Semi-autos are available in every shotgun configuration, from tactical models and high-end trap guns to heavy, extra-long-chambered guns for wildfowl and turkey hunting. They are available in every modern gauge and chamber length.

Modern semi-autos, like the famous Benelli, are renowned for their durability and dependability. High-volume wingshooting operations in Central and South America, where hunters shoot thousands of doves in a day, customarily use semi-autos, with Benelli 20-gauge guns being almost the standard.

Hand-filing the interior of a Francotte sidelock at CSMC.

At CSMC, every gun is taken to the range for extensive test-firing. No gun is shipped until it comes back from the range with every function perfect.

The many faces of the Benelli semi-auto, from left: a Duca di Montefeltro 20-gauge game gun, a 12-gauge M2 Tactical, and a Super Vinci 12-gauge waterfowl gun. The Super Vinci will accept up to 31⁄2”-inch shotshells.

The Browning Auto-5 is one of the most famous of all semi-autos, being a John M. Browning design that was made for many years at the Fabrique National (FN) arms factory in Liège, Belgium. It was patented in 1898, production began in 1900, and it continued (discounting interruptions due to the World Wars), for almost exactly a century. The last special, commemorative guns were made by FN, in 1999. The design has been produced by several other gun makers, as well, including Remington and Franchi. The “humpback” Browning has many fans and is loved both for its dependability and pointability. However, with its square-backed receiver, it is a disconcerting gun to shoot for anyone accustomed to a double or a pump. The Auto-5 also uses a “long-recoil” design that results in a great deal of movement, to which many shooters find it hard to become accustomed.

Above and below are two extremes in game guns, both by Benelli. The 20-gauge (on the left above), is a nicely appointed upland gun, while the 12-gauge Super Vinci is the latest in a camouflaged, high-powered waterfowl and turkey gun.

One undoubted advantage of semi-automatic shotguns is reduced recoil. The Remington 1100, introduced in 1963, was the first semi-auto to really demonstrate this. The gun has remained in production ever since and, with more than four million guns produced, is the best-selling semi-auto in history. Recoil reduction is a result of diverting some of the shotshell’s energy to operate the action. For this reason, the semi-auto is often recommended for beginners, especially if a 12-gauge is needed for a particular application. A 20-gauge semi-auto, the favorite for doves in South America, has very gentle recoil, when used with standard 23⁄4-inch cartridges and light shot loads.

There are disadvantages. One is safety. Because the gun reloads itself almost instantly, it is always ready to fire, whether you want it to be or not. With beginners, this can be a problem. Even the pump gun can be rendered safe, simply by pulling back the slide. With a semi-auto, the shooter needs to withdraw the breechblock and lock it in place.

In parts of the world where driven shooting of game birds is common (beaters in the fields drive flocks of birds to lines of waiting guns, those shooters usually positioned in berms), safety is a paramount concern. Many shoots prohibit semi-autos because, unlike doubles, they cannot be broken open and be seen to be safe at a distance. This practice is even followed by some pheasant-hunting operations in the Dakotas.

Trap clubs are another place that often don’t welcome semi-autos because, shooting on a line, the gun flings its empty hull to one side. This can annoy the shooter next to you, if the hull bounces off him or his shotgun. Some clubs require a net over your ejection port that will catch the empties.

Finally, there are legal restrictions in some countries. Anyone travelling abroad to shoot needs to pay close attention to local laws, before attempting to import a semi-auto. Even if the gun itself is legal, there may be restrictions on magazine capacity.

We have covered the main types of shotgun actions, but there are others. In the late 1800s, as American gun makers perfected the lever-action rifle, they tried to adapt the lever mechanism to shotguns. The same occurred with bolt-actions. In Germany, shotguns were often combined with rifle barrels in myriad designs to create multi-purpose guns.

Top and above is Ryan Mason, of Missouri, with his Beretta semi-auto competition gun decked out in the colors of the University of Missouri Tigers.

The lever-action shotgun was an early design that lost out quickly to the pump gun. Lever shotguns were heavy, clumsy, and slow. The same was true of the bolt-action shotgun, which, in reality, was a scaled-up .22 rimfire single-shot rifle with the simplest (and one of the strongest) of mechanisms. It had its points, mainly cheapness and durability, which is why it hung on long after the lever shotgun was dead.

Several manufacturers, including Mossberg and Marlin, have made bolt-action shotguns with box magazines that hang down below the action. These are strictly utility guns and really unsuited to wingshooting.

One action that should probably have been included with either pumps or semi-autos is the combination pump/semi-auto. The most famous example is the SPAS-12, an Italian gun made by Franchi and immortalized by Arnold Schwarzenegger in The Terminator. The SPAS-12 has made every gun-ban wish list since 1983, largely on the image it projected in that movie. For practical use, it is heavy and clumsy.

Another real oddball is the Street Sweeper, a design that borrows from both revolvers and the old Thompson submachine gun. It originated in South Africa, and it is rarely seen in the United States, but it shows just how fanciful shotgun designs can be and how far they can stray from the original concept of a gun for shooting birds on the wing. The Street Sweeper has a short barrel and 12-round drum magazine. The drum is loaded, then powered by a wind-up spring. It rotates like a revolver cylinder and employs a double-action trigger similar to a revolver. Like the SPAS-12, it is on every gun-ban list, mostly because of its fearsome appearance and intimidating name.

Here’s Ryan again, this time with the Benelli Super Vinci, a gun with superb ergonomics to go with its futuristic appearance.

• • •

Today, visiting a trap, skeet, and sporting-clays range, you might see any of the above designs in use. Each has its adherents.

In shotgunning, there are exceptions to every rule, but, generally speaking, the semi-auto has emerged as the most common all-around shotgun. Over/unders predominate in higher-level skeet, trap, and sporting clays competitions. Pump guns are found anywhere and everywhere (but rarely, these days, in the winner’s circle), and side-by-sides are niche guns preferred by upland hunters or used in designated side-by-side competitions.

These divisions are not based solely, or even mostly, on what is best for a particular application. Cost plays a part, as does availability. The fact that the pump gun did not kill off the side-by-side, nor the semi-auto the pump, proves that each type of gun has enough of an edge somewhere to ensure each will be around for a long, long time.

Alison Caselman, demonstrating good form with the Benelli 20-gauge semi-auto.