CHAPTER 5

THE SHOTSHELL

Shotguns are made today in six basic gauges: 10, 12, 16, 20, and 28, and .410-bore. As with most things to do with shotguns, the conventions and terminology are rooted in the practices of more than a century ago. Essentially, the guns and shotshells we use today were developed and perfected by 1900, and those now in use are merely refinements of very old designs.

SORTING OUT THE GAUGES

We should begin with the term “gauge” itself or, as it is called in Europe, “bore.” Unlike rifles and handguns, whose calibers are the measurement of actual bore diameter, shotguns use terminology descended from early cannons. In the Napoleonic era, cannons were sized by the weight of the round ball they threw. Hence, the famous British 12-pounder hurled a 12-pound projectile.

Handheld firearms were identified by the number of lead balls of equal size, making up a pound, that would fit the bore. Using the earlier terminology, if a pound of lead were divided into 12 equal parts, and each twelfth was formed into a perfect sphere, it would be .729-inch in diameter and the gun called a “one-twelfth-of-a-pounder.” This was awkward, so it was shortened to 12-bore or, in America, 12-gauge. In a 16-gauge, there would be 16 balls to the pound, in a 20-gauge, 20, and so on. The exception is the .410, which is an actual caliber. In terms of gauge, a .410 is about 68-gauge. So, we have the somewhat confusing situation in which the smaller the number, the larger the gun.

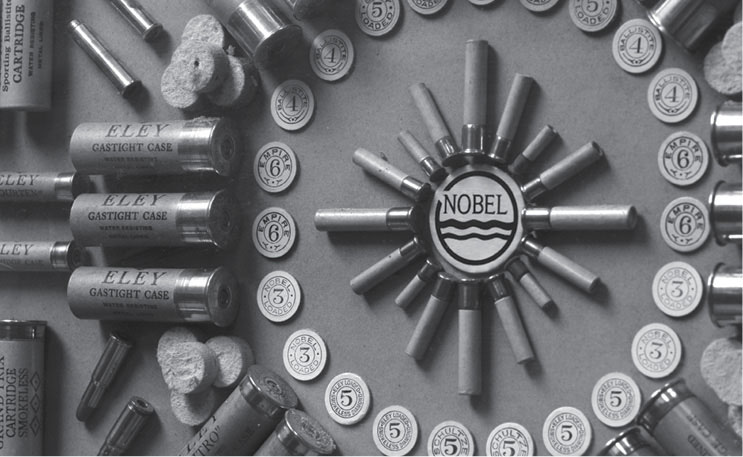

In the muzzleloading era, bore diameter could be anything the maker or shooter wanted, since powder and shot were poured down the bore from the muzzle end; the only part of the ammunition that was sized was the wad, and those were usually cut by the shooter. With the advent of breechloading and self-contained ammunition, gauges were standardized. In the blackpowder era, there were 2-, 3-, 4-, 6-, 8-, 10-, 12-, 13-, 14-, 16-, 20-, 24-, 28-, and 32-gauge. As blackpowder gave way to smokeless, the number of gauges was reduced, with only the most efficient and popular retained.

• • •

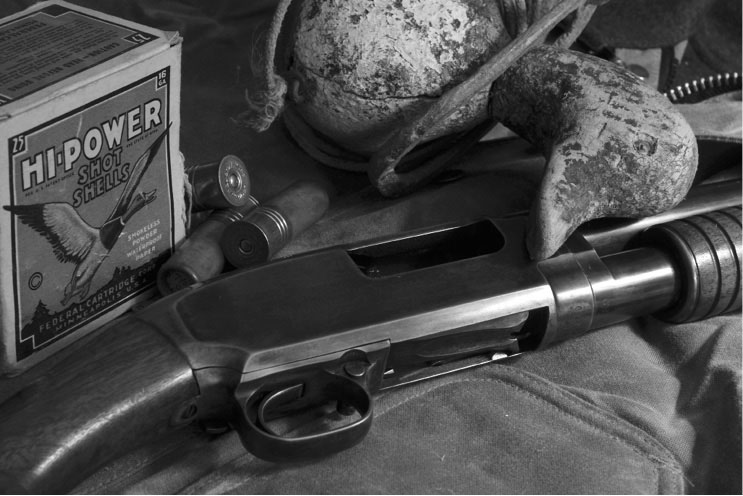

A modern shotshell’s internal components are essentially the same as in muzzleloading days. There was gunpowder, an over-powder wad, a charge of shot pellets, and a wad to hold the pellets in place.

In today’s standard plastic shotshell, the over-powder wad is a plastic shot cup that not only provides a gas seal, but cradles the shot as it goes up the barrel; in place of the over-shot wad there is the mouth of the shell, which is folded into a pie crimp. Modern shot cups tend to tighten patterns, which is not always desirable.

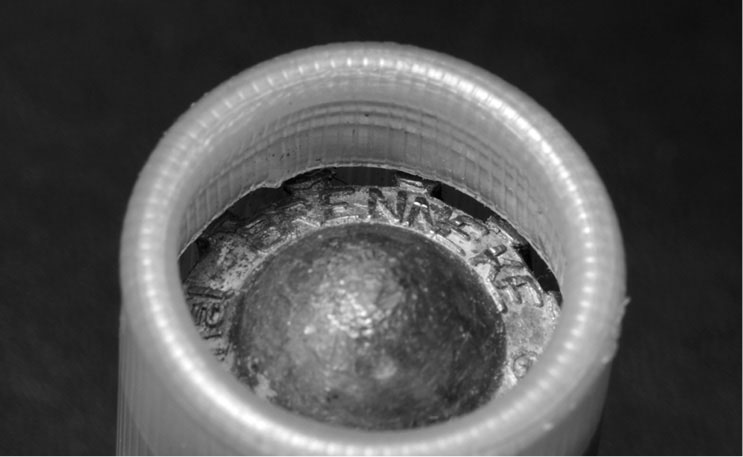

Each component serves a vital purpose, some more than just one. For example, the primary purpose of the over-powder wad in a blackpowder shotgun is to keep the powder packed firmly, the shot charge separate from the powder, and to act as a gas-sealing piston. It also cushions the shot from the initial pressure spike, thus preventing deformation of the pellets.

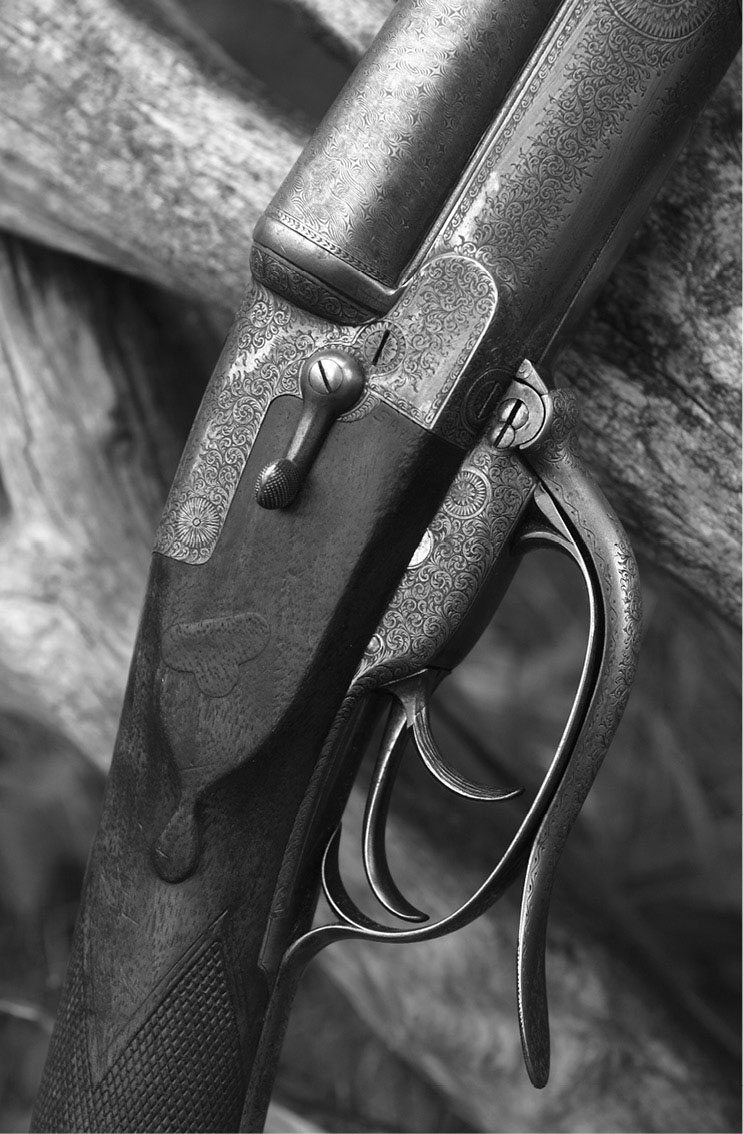

The shotshell evolved gradually, beginning around 1850, with the first breechloading guns. The idea of loading a gun from the rear had been a goal of gun makers for years. Having achieved a method of opening guns and fastening them closed, they then needed a convenient way to pack the powder and shot into the breech. The theory of the self-contained cartridge (from the French cartouche), had been around for some years, with the military issuing rolled paper packets that contained powder and ball, the paper serving as the wad.

From this basic idea emerged the pinfire cartridges used by the first breechloading guns. Instead of the hammer striking a cap perched on a nipple and sending a streak of flame into the gun to ignite the powder, a pinfire cartridge had a pin that extended into a cartridge. The hammer struck the pin, the pin struck an internal cap, and the cap detonated the powder. The cartridge case, complete with pin, was then pulled out of the chamber and replaced with a new one.

The pinfire cartridge case was made of rolled paper and brass. For the next 50 years, ammunition makers experimented with rolled- and drawn-brass cases, paper, combinations of them, and even aluminum cups wrapped in paper. The goal was to create a shotshell that was efficient, consistent, and powerful, as well as resistant to moisture. Eventually, the paper case — rolled, multi-layered, waxed paper, set in a brass cup — emerged as the most cost-effective pattern, remaining so until the 1960s, when plastic cases made their appearance.

A significant factor in shotshell design and manufacturing was the powder. Blackpowder was the early propellant. It occupies considerably more space than the various smokeless and semi-smokeless powders that began to replace it, in the 1880s. Since the sizes of bores and cases were already established — and since an ounce of lead shot occupied the same space regardless the propellant and, so, could not be altered — manufacturers had to find some way to take up the excess space in the case. They did this by filling up the space between the powder and shot with more wads, usually made of cushioning wool felt. After 1960, such wads were replaced by plastic shot cups of varying design, some simple, some bizarre, some patented and exclusive. Shotshell manufacturers guard their shot cup designs jealously and make claims for them ranging from improved patterns to reduced recoil.

The one great truth that emerged from all the research and development of shotshells, from 1850 to 1960, is that the laws of physics governing the behavior of a round lead pellet flying through the air dictate shotshell performance, and these laws of physics do not change. The corollary is that optimal shotshell performance is achieved by avoiding extremes, whether of shot size, charge weight, powder charge, or velocity. Moderation delivers the best results.

• • •

Of all the gauges, in theory, the 16 should be the most useful and popular, for both ballistic and practical reasons. Each 16-gauge lead ball is exactly one ounce, and an ounce of birdshot, in a 16-gauge, forms a shot column about as tall as it is wide. Again, in theory, such a shot column should deliver the best pattern.

Using the “rule of 96,” which states that, for tolerable recoil and for the well-being of the gun itself, a gun should weigh 96 times the shot charge, a 16-gauge gun would weigh exactly six pounds — the Utopian game gun weight.

While the 16-gauge has always been very popular in continental Europe, the 12-bore became dominant in England and the United States. Today, in the U.S., the 16-gauge is the least popular of the three common larger gauges. The 12 still dominates, but the 20 is closing fast and the 16 is a distant third. The 16’s also-ran status is usually blamed on the inventors of skeet, who decreed that the game would be officially played with only four gauges — 12, 20, 28, and .410. Why the 16 was left out, who knows? It was very popular at the time and widely regarded as the “gentleman’s gun,” to differentiate it from the market gunners’ 12- and 10-gauge shotguns. Whatever the reason for its omission, as skeet spread like wildfire, it resulted in a general neglect of both 16-gauge guns and ammunition, a situation that continues to this day.

• • •

Another factor to be considered when choosing a gauge is the length of the cartridge. Three of the gauges (12, 20, and .410) have a three-inch “magnum” version, which holds more powder and shot than standard lengths and delivers more lead downrange at higher velocities. We will go into greater detail about the cartridge lengths available in each gauge, as we look at them in turn. There is, however, a general observation that can be made about all of them, and that is that a shotgun’s effectiveness is determined by the quality of the patterns it throws, not by the number or size of the pellets, nor by their velocity.

Traditionally, the ideal pattern is described as resembling an expanding beach ball, as high and wide as it is deep, with pellets evenly distributed within this sphere. The shot charge begins to expand about 10 yards from the muzzle of the gun and continues to change shape until, 200 to 300 yards distant, the last pellet drops to earth. Because the pattern is dynamic and constantly changing and cannot be seen while it is in the air, pattern definition is a source of endless fascination and endless argument.

As we saw in the discussion of chokes, the degree of choke plays an important role in determining the shape of a pattern, but pattern quality also depends on a number of other factors.

The 16-gauge is, again, theoretically ideal, because its ounce of shot forms a shot column of the right dimensions to translate into the perfect pattern. Excessively long shot columns create problems that inevitably affect pattern quality. This is the reason that 11⁄4 ounces of shot in a 10-bore is better than in a 12, and the 12-bore delivers better patterns with 11⁄4 ounces than the same amount of shot in a 20-bore. Similarly, packing a full ounce of shot into a 28-bore does not give you the equivalent of a 16. This is not to say that longer cartridges and heavier loads do not have their uses, only that, in shotgunning, there is no free lunch. What you get over here you will have to pay for over there. Long shot columns result in strung-out patterns, like the tail of a comet, with the badly trailing pellets performing no useful function beyond the odd fluke kill or broken clay. The occurrence of such flukes does not begin to make up for the loss of overall pattern effectiveness.

To visualize why shot stringing occurs, imagine a large crowd of people jostling and shoving to get through a narrow theater door, pursued by smoke and flames. Inevitably, many end up crushed and trampled on the floor. Much the same thing happens when a long shot charge is pushed by expanding powder gases. The pellets closest to the pressure are crushed against the pellets ahead, becoming deformed either a little or a lot. Being no longer perfectly round, when they leave the muzzle, they lose velocity more quickly and tend to veer off to the side. Either way, they accomplish nothing for the shooter.

Tests have repeatedly shown that the best pattern quality is achieved with velocities from 1,050 to 1,200 fps at the muzzle. Anything less and the shot won’t spread properly, which is why the early low recoil, low noise loads from the mid-1990s delivered a pattern the size of a grapefruit. If velocities go too high, on the other hand, they tend to “blow” patterns, giving the shot charge a violent shove as it leaves the muzzle and either scattering or blowing large holes in the pattern.

These general principles of shotshell performance have been proven repeatedly since the 1880s, but shotshell manufacturers still go to great lengths in attempting to circumvent them. They have tried buffering shot with other materials and using different shapes and styles of plastic shotcups. They have tried, in so-called non-toxic loads, different metals and compounds for shot. With some of these, notably the irregularly shaped Hevi-Shot, stringing and patchy patterns became a fact of life. The manufacturer tried turning a vice into a virtue by insisting that a long, strung-out pattern allowed you to shoot badly and still hit a bird with the tail of the string. This is grasping at straws on a grand scale — then again, shotshell manufacturers have a genius for selling us things we don’t need.

An interesting tidbit is the fact that today, with plastic shot cups, the diameter of the 12-gauge shot load is about what the 16 was in the days of muzzleloaders. This means that the theoretical ideal, with modern shotshells, is a one-ounce 12-gauge load, not a one-ounce 16.

The standard method of patterning a shotgun is to erect a sheet of paper at 40 yards, fire a shot at it, draw a 30-inch circle around the main concentration of pellets, and count the holes. The number of holes inside the circle, as a percentage of the entire shot charge, defines the choke. What a patterning sheet fails to tell you is the front-to-back shape of the pattern itself, nor does it tell you when each pellet struck the sheet. What looks like a nice, even pattern with no gaps could be the result of a pattern that was strung out 15 or 20 feet in the air, with many of the pellets performing no useful function. But, on paper, it looks pretty good.

12-GAUGE

The 12-gauge is the most popular and versatile of all the shotgun gauges in use today. It has been the standard for all wingshooting in England for 150 years, and in America for a century. The 12 is the only gauge used for trap shooting and big money box-pigeon matches, and it dominates sporting clays competition. In hunting, the 12 is the usual waterfowl and turkey load; in areas where deer hunting is allowed only with shotguns, most hunters use a 12.

Twelve-gauge guns have been made in every imaginable configuration, including hunting, competition, and tactical guns, with chambers ranging in length from 2 inches to 31⁄2 inches. The 2-inch 12-gauge originated in England, in the late 1800s, and was intended for very light guns. Chambers of 25⁄8 inches were common in England until the early 1900s, when the length was standardized at 21⁄2 inches for game guns; English live-pigeon guns were often chambered for more powerful 23⁄4-inch cartridges, and waterfowl guns for 3-inch rounds. In America, length was standardized at 23⁄4-inch, with 3-inch shotshells coming around 1930, and the huge 31⁄2-inch in 1987.

In America, today, the usual 12-gauge cartridge has a 23⁄4-inch hull. This is the length from the rim to the lip of the case when the case has been fired. A loaded 23⁄4-inch shotshell with its lip folded over and crimped is only about 21⁄4 inches. Length is important because, while you can safely fire a shorter cartridge in a longer chamber, you should avoid doing the reverse.

A chamber is bored the length of its shotshell when that shotshell is fully opened. On firing, the case opens to its full length and should then completely seal the chamber. This being the case, since a 23⁄4-inch cartridge measures only 21⁄4 inches when loaded, you can easily slip one into a 21⁄2-inch chamber. The problem is that it will not be able to open fully, which means the shot and plastic shot cup must be forced through a smaller opening. This raises pressures and potentially plays all sorts of havoc.

There are conflicting opinions as to just how damaging or dangerous this is. Some authorities would have you believe you are taking your life in your hands, or at least endangering your shotgun. One ammunition company, however, is reported to have run a series of tests and found no increase in pressures from the practice. This author is personally familiar with one instance in which a Gibbs & Pitt’s-patent English game gun from the 1870s, with a 25⁄5-inch chamber was subjected to a steady diet of Canadian 23⁄4-inch ammunition, including magnum duck loads, over the course of about 40 years. When the gun went in for a cosmetic restoration, the action was still tight as a drum. That could be merely a testimonial to the strength of that action. Having said that, it is impossible for the author to believe that subjecting any gun to such regular pressure spikes is not bad for it in the long term. At the very least, it cannot be good for it.

After 1945, as more and more English guns were brought into the United States, many of them had their chambers lengthened to 23⁄4 inches. For most, this is perfectly safe, though, on some very light guns, it could result in excessively thin barrel walls at the end of the chamber. Lengthening a chamber is an operation that should only be undertaken by a skilled gunsmith who understands the idiosyncrasies of double-gun barrels.

If you encounter such a gun and find that it does not pattern very well, or that the two barrels do not pattern together as they should, try shooting the original 21⁄2-inch load. That, after all, was what it was regulated with. In one case, I found that an erratic gun became as sweet as honey, when I went back to the load for which it was originally chambered and regulated.

As with chambers, commercial 12-gauge ammunition is made in lengths from 2 inches to 31⁄2 inches. Each has its purpose.

The 2-inch was an English development that received some attention in the late 1800s. W.W. Greener marketed it as “Greener’s Dwarf,” and guns so chambered were lighter than a standard 12 — six pounds or less, as opposed to 61⁄2 pounds. Charles Lancaster’s version, the “Pygmy,” caused considerable controversy with the editor of Land and Water, because of allegations of “shot balling.” When shot “balls up,” the pellets bond under pressure to become a single, highly hazardous projectile, endangering beaters (in driven shooting) and bystanders. Although the phenomenon was never proven, such short cartridges never enjoyed great popularity, probably because they were, to all intents, a 20-gauge charge in a 12-gauge shell. Such guns still appear for sale periodically, and you can order one from the English and Spanish custom gun makers.

You might wonder why anyone would go to that trouble and not simply buy a 20-gauge. The answer lies in the question of shot patterns, as discussed above. A 7⁄8-ounce load in a 12-gauge gives a shorter shot column than it does in a 20-gauge, with theoretical improvements in pattern. We should say, however, that too short a shot column is no better than one that is too long. Each gauge has its ideal range of charge weights, and 3⁄4-ounce is about the smallest practical in a 12-gauge.

Up until 1914, many guns were made with chambers measuring 25⁄8 inches; in America, this was later standardized at 23⁄4 inches, while the U.K. settled on 21⁄2 inches. Then came development of the 3-inch magnum, followed, in 1987, by the mammoth 31⁄2-inch. The 3-inch cartridge can take a charge load up to two ounces, while the 31⁄2-inch, generally reserved for waterfowling or turkey loads, has a capacity of up to 21⁄2 ounces.

With the advent of so-called “non-toxic” shot for waterfowl, in the 1980s, various lead substitutes were employed as shot material, including steel, bismuth, and different tungsten-based pellets. Since steel is less dense than lead, larger pellets are required to achieve the same killing power. At the same time, two ounces of steel occupy a larger space than two ounces of lead. The additional room in the longer case can be put to good use.

With many guns and a great deal of ammunition now being imported from Europe, chamber and cartridge lengths and charge weights are often given in metric measurement. For the record, a 21⁄2-inch cartridge is 65mm, 23⁄4-inch is 70mm, and 3-inch is 76mm.

20-GAUGE

The 20-gauge is the second-most popular gauge in use today, and for good reason. A 20-gauge gun, with its .612-inch bore diameter, is sleeker and less bulky than a 12 and can be built to weigh six pounds or even less. A pocketful of 20-gauge cartridges weighs noticeably less than the same number of 12s.

There are three cartridge lengths for the 20-gauge: The English standard 21⁄2-inch, the American standard 23⁄4-inch, and the 3-inch magnum. Most mass-produced 20-gauge guns made today have 3-inch chambers.

While standard 20s are delightful to carry and pleasant to shoot, the 3-inch cartridge turns them into monsters. The magnum load is 11⁄4 ounces of shot, the same as a heavy 12-gauge game load. Most emphatically, however, this does not make the 20 the equal of the 12. A 11⁄4-ounce load in a 20 creates a long shot column, with all the negatives such a thing implies for patterns. Because you are forcing the same weight load through a smaller opening, higher pressures are required to achieve the same velocities. Combine all that with a 20-gauge gun weighing six pounds, and you have a nasty-kicking little beast that will induce a flinch in no time. The late Michael McIntosh was of the opinion that we would all have been better off if the 3-inch 20-gauge had never been thought of, and this author agrees wholeheartedly.

Having the 3-inch chamber but using only 23⁄4-inch loads does not give you something for nothing. If you order a 20-gauge gun with a magnum chamber from a European custom maker, it will be heavier and bulkier than a standard 20, because their proof laws demand it. So, you will be carrying around more gun than necessary, even if you plan never to shoot anything but 23⁄4-inch loads; you will have ordered the longer chamber only to enhance resale value. And outside of waterfowling, the 23⁄4-inch 20 with either 7⁄8- or one ounce of shot will do anything desired, provided you are shooting within reasonable distances and put the shot in the right place.

In South America’s high-volume dove shooting, the standard gun is a Benelli 20-gauge semi-auto, using 23⁄4-inch cartridges and either 3⁄4- or 7⁄8-ounce loads. Those shooters routinely fire two thousand shots in a day and, if you think such light loads don’t hurt, you try shooting in such numbers. Everything becomes a factor, from the weight of the gun to the effects on your shoulder, arms, and face. Semi-autos are favored, because they offer more shots before reloading, and also because they further tame even the mild recoil of a 20.

Contrary to popular belief, even the wildest of wild pheasants in the Dakotas will fall to a standard 20, if you place your shot correctly. One of the finest shots the author ever witnessed took place in North Dakota, on a day when the pheasants were riding a 60 mile per hour wind. Artist C.D. Clarke took a high pheasant at full speed, with a shot from his Arrieta 20, using B&P 15⁄16-ounce ammunition. The wind carried the dead bird more than 60 yards in a long arc, with C.D.’s Brittany, Chess, coursing it all the way.

16-GAUGE

The 16 is the most logical of all the gauges. Its bore diameter is .662-inch, almost exactly two-thirds of an inch. A 16-gauge lead ball weighs exactly an ounce. An ounce of shot in a true 16-gauge bore creates a shot column of perfect dimensions for a good pattern.

In the United States, in the early years of the twentieth century, the 16 was known as the “gentleman’s gauge.” This differentiated it from the down-market 12, which was used by market gunners, farmers, and deer hunters. The romantic ideal of a 16 was a sleek double — a Parker, perhaps, or an Ansley Fox — intended for hunting upland birds like bobwhite quail and ruffed grouse.

The 16 comes by this patrician image honestly. Its antecedents go back centuries. In the era of blackpowder cartridge shotguns and rifles, 16-bores were made for hunting big game with solid ball, as well as for fowling. As we have already noted, on paper, the 16 is the perfect shotgun, the right size load creating the optimum shot column for delivering the perfect pattern from a gun weighing exactly six pounds. So what went wrong?

In Europe, nothing. There, the 16 is still very popular and was widely used in making combination guns like drillings. In England, the 16 was never as popular as the 12, but there were always a few around, and there still are. In fact, the last year or two has seen a fad for 16s; during a visit to Holland & Holland’s Bruton Street shop, in late 2012, I saw a rack with a half-dozen 16-bore doubles just waiting for new homes.

In the United States, the 16’s loss of popularity is generally blamed on the originators of skeet. When the rules for skeet were drawn up, in 1926, it was decreed that the game would be officially shot with four gauges — 12, 20, 28, and .410 — and that left the 16 an orphan. You might think this would have had a minimal effect, but the course of events went roughly as follows.

With a widespread decline in game bird numbers and strict bag limits, shooters were left with trap and skeet, if they wanted to do much shooting. Trap, of course, is a 12-gauge game. Skeet spread rapidly, and soon manufacturers were making guns and ammunition tailored to its requirements.

Competition shooting eats up huge amounts of ammunition, and there was intense rivalry among Federal, Winchester, and Remington, and several other companies no longer with us, to produce winning loads. Research money was poured into improving 12, 20, 28, and .410 ammunition, while the 16, which was no longer selling in anywhere near the volumes of the 12 or 20, was left to languish. Even the hulls were not as good; where a 12-gauge man could shoot Federal Gold Medal, Winchester AA, or Remington Premier STS and reload his own, 16-gauge shotshells used old technology and could not be reloaded nearly as well. When it comes to volume shooting, you need to be either independently wealthy or load your own, and successful reloading is dependent on components. Not only were good 16-gauge hulls hard to find, shooters were limited in their choices of plastic wads and shot cups. As well, lacking the volume-production savings of the 12 or 20, 16-gauge components were relatively expensive.

As for factory ammunition, manufacturers seemed determined to make the 16 the ballistic equivalent of the 12, presumably believing no one would shoot a 16 otherwise. Sixteen-gauge “heavy field” loads were hot and threw 11⁄8 or 11⁄4 ounces of lead. In a standard-weight 16, they kicked badly, never patterned particularly well, and were expensive. Is it any wonder the 16 went into a steady, sad decline?

Today, there are essentially two cartridge lengths in 16-gauge, the English and European 21⁄2-inch and the American 23⁄4-inch. Up until about 1914, there was also a 25⁄8-inch on both sides of the Atlantic, and while you’ll still see old guns with that chamber length, ammunition is no longer made. Fortunately, no one ever saddled the 16 with a 3-inch magnum version.

RST, the boutique ammunition company that supplies lovely, light loads in all different gauges and case lengths to keep old guns shooting and provide comfortable shooting even for new guns, makes 16-gauge ammunition to suit any gun ever made. More components are available today from reloading supply firms like Ballistic Products, and there is an increasing amount of reloading data for everything from low-pressure loads for vintage guns to hefty waterfowl loads using non-lead shot.

Ballistically, the 16 lies between the 20 and 12. It is at its best with shot charges of 7⁄8-ounce to 11⁄8 ounces. A 16-gauge double weighing 61⁄4 pounds, with 30-inch barrels, is the kind of upland gun that grouse and woodcock hunters rhapsodize about (or bobwhite quail and dove hunters, for that matter). You can carry it all day and hardly feel it, then shoot a hundred rounds and be ready for more. Unfortunately, in this era of non-lead shot for migratory birds, the standard 16 really doesn’t have the case capacity to accommodate the bulkier steel-shot charges required, so it is best relegated to upland status.

The aura of the “gentleman’s gauge” has crept into the limelight once again. America’s classic doubles in 16-gauge, such as the Parker, Ithaca, Fox, and L.C. Smith, are in great demand on the used gun market and their prices are high. Still, if there is a bargain to be had in guns, it is in the 16-gauge pumps from years past — the Winchester Model 12, the Remington Model 31, and the Ithaca Model 37. In 16-gauge, these guns are a pleasure to carry and shoot, and they generally sell for considerably less than a 20 or 28 in comparable condition. And, if you can find a Belgian-made Browning in 16, whether it is a Superposed or an Auto-5, grab it. Those don’t sell for peanuts by any means, but think of it as a lifetime investment in pleasant shooting.

Generally speaking, German and Austrian 16s from days past range from technically very fine to rather crude. What most have in common, alas, is that they are really not made for wingshooting as we know it. They are either combined with a rifle barrel or have excessive drop in a rifle-style stock.

I have strayed somewhat from discussion of the gauge itself into the guns that use it, but conversations about the 16 tend to do that. The reason? The 16 can be built into the ideal upland game gun, whether it in a double, pump, or semi-auto. The big ammunition makers are starting — tentatively, hesitantly, seemingly reluctantly — to offer some 16-gauge loads that are civilized in punch and recoil and still suitable for dove shooting or for an informal round of skeet. Magazine articles proclaiming the rebirth of the 16 are almost as numerous as those mourning its death. Here, in this book, we are doing nothing except announcing improving signs of life in a lovely old gauge that deserves to be embraced by all.

28-GAUGE

Contrary to popular belief, the 28-gauge was not invented by Parker. Parker may well have been the first American gun company to chamber it, but it did not invent it. Like the 16, it is a very old bore size, one dating from the days of muzzleloaders.

When blackpowder cartridges replaced muzzleloaders, the 28-bore’s career split, and it became the 28-gauge shotshell we know today, as well as the basis for the many .577-caliber rifle cartridges, including Holland & Holland’s .577 Baker and the legendary .577 Nitro Express. England’s military .577 Snider rifle was the 28-bore Enfield military musket converted to a breechloading brass cartridge. As late as the 1870s, .577 rifles sent to the London or Birmingham proof house for proofing were stamped “28” by the proof master, because that was the bore’s gauge.

Just as the 16-gauge owes its shaky status to its exclusion from skeet, so, too, does the 28-gauge probably owe it current popularity, if not its very existence, to its inclusion on that list.

The 28-gauge has two cartridge lengths, the usual 21⁄2-inch in England, and the 23⁄4-inch in America. Mercifully, there has never been a 3-inch 28-gauge. The very idea of attempting to convert the mild 28 into a 20-gauge equivalent with an ounce of shot, turning its five-pound guns into nasty little beasts, makes the blood run cold.

The 28 has a bore diameter of .550-inch, and standard loads range from 5⁄8-ounce to one ounce of shot. Because of the small bore, any shot size larger than No. 6 sits uneasily in the shot column; for game shooting, No. 71⁄2 is probably best. Ballistically speaking, once you have a 3⁄4-ounce of No. 71⁄2s in the air, flying at 1,100 feet per second, it doesn’t matter if they were launched by an overloaded .410 or an under-loaded 10-gauge, but one writer after another has rhapsodized about “killing power out of all proportion” in a 28-gauge.

This idea has given rise to several rather contradictory beliefs. One of these is the notion that it is somehow “more sporting” to use a 28, if you happen to be such an expert shot that you simply can’t miss with a 12. The other is that the 3⁄4-ounce of shot from a 28 is somehow more deadly than the same shot charge from a 12. Neither of these beliefs stands up to scrutiny.

Since the question of what is sporting and what is not arises most frequently in connection with the 28-gauge, this is a good place to deal with it. In wingshooting, the concept of a “sporting chance” is at odds with the goal of any ethical hunter, which is to kill game cleanly and without suffering. A 28-gauge gun with open chokes throws a pattern that covers the same area and is governed by the same percentages as a 20 or 12. But because the shot charge contains fewer pellets, you have a less dense pattern and, hence, a better chance that, even if you center your target, it will be struck by fewer pellets, thereby increasing the chance of wounding and losing the bird. If, however, you tighten the chokes on a 28 to increase the density, thereby reducing the overall size of the pattern, it does demand greater shooting skill to eliminate increasing the chance of wounding. But how many 28-gauge fans do this? Not many. Most 28s I have seen in the hands of hunters have had Improved Cylinder chokes.

The second belief illustrates the strange disconnect that can occur in the minds of people when promoting a cause. A few years ago, I encountered a 28-gauge proponent in North Dakota. His car stickers proclaimed his allegiances to the NRA, the Navy, and nuclear submarines and, in retirement, he’d become a gun writer for the local weekly. He used a 28, he said, because a 12 was just too easy. “If you put the shot in the right place, three-quarters of an ounce will do the job,” he said, even on North Dakota’s wild pheasants.

No argument there. But then he went on to explain why, for wild pheasants with a 12-gauge, you need at least 11⁄2 ounces of shot, preferably No. 4s, at 1,500 fps — a load that makes any gun under nine pounds a vicious mule. These two points of view are completely contradictory, unless you have a religious belief in the magical qualities of a bore that is .550-inch, instead of .729.

Many 28-gauge guns are too light and outfitted with barrels that are too short. As a result, they are very whippy. Hitting anything, for the average shooter, becomes extremely difficult. In recent years, the trend in 28-gauge barrels has been back toward 30 inches or even longer, with guns weighing right around six pounds. For a gun to shoot, this is about the ideal for most people. Combine this with Modified chokes and 3⁄4-ounce loads, and you have a gun that will challenge any good shooter, yet kill cleanly and break clays. Recoil will be almost nonexistent. If I were told I would have only that gun to shoot for the rest of my life, I would not feel particularly handicapped. In fact, it would be fun.

Because the 28 is a skeet gauge, there are excellent hulls and a generous variety of reloading components available. This is good because, if you want to shoot 28 in any quantity, the price of loaded ammunition will cause you to swoon. How something half as big as a 12-gauge can cost twice as much is an abiding mystery.

For a variety of reasons, 28-bore guns have never existed in great numbers. Those that do tend to be of higher grades and more expensive, whether old or new. Finding one the size and shape you want, at a price you can afford, is not easy. Many 28s made today are simply 28-gauge barrels stuck on a 20-gauge frame. This reduces costs, but does nothing for the shooter who is looking for a genuine 28-gauge. As well, the quest for an “all gauge” skeet gun that weighs exactly the same no matter what discipline you are shooting leads to 28s that are relatively heavy.

Every so often, a magazine article will appear touting the 28-gauge as some sort of “super bore” that can kill efficiently at ranges out of all proportion to its size. Generally, such articles are not written by professional shotgun writers, but by individuals who are riding their pet hobbyhorse. This is an important distinction to make, not to denigrate individuals, but to point out that professional shotgun writers, having been exposed to may different guns and loads, tend to be more restrained and moderate in their views on particular combinations.

Bob Brister, who was shotgun editor of Field & Stream for decades and wrote a very valuable book called Shotgunning: The Art and the Science, noted that the one-ounce load in the 28-gauge shared a characteristic with the classic live-pigeon load, which is 11⁄4 ounces of shot with 3⁄14 drams-equivalent of powder; that is, both seemed to be extraordinarily efficient. He even quoted one of Remington’s shotshell ballisticians as being baffled as to why this should be, but insisting that it really was.

Given the time and effort Brister devoted to testing, especially patterning loads and trying to understand pattern shape, I am not about to argue with him. His explanation was that each seemed to achieve “balance.” To Brister’s duo, I would add the 12-gauge load of one ounce of shot and three drams-equivalent powder, which is a superb game load for almost anything that flies.

Balance is a very valuable concept in evaluating any shotshell load, and the subject has been espoused by every reputable shotgun writer from J.H. Walsh, in the 1880s, through Sir Gerald Burrard, in the 1930s, Gough Thomas, in the 1960s, and Brister, McIntosh, and others to the present day. Going to any extreme, whether it is shotshell length, charge weight, powder, velocity, or pellet size, tends to degrade patterns and performance and lessen efficiency and killing power. The 28-gauge is no exception. With the right ammunition and chokes, it’s a great gauge, but it is not a magic wand.

.410-BORE

Without question, the .410 is the most controversial of all the bore sizes. Some experts believe it is not even a real shotgun round and has no place in any type of hunting. Others, including some very fine shots, insist it is “the expert’s gun.” They carry a .410 choked Full, their 3-inch shells are loaded with 11⁄16-ounce of shot, and they shoot them with rifle-like precision.

For the average shooter, there is a slight perception problem with the .410. In terms of actual numerals, there is not much difference between 20, 28, and .410; if the .410 were numbered as a gauge, however, it would, in fact, be a 68. Maybe if we called it a 68-gauge, shooters would not give it more credit than it is due.

In truth, the .410-bore should be approached in a completely different way than with any of the other gauges. This has long been acknowledged by the convention of patterning the .410 at a different distance than the others. Choke designations for the .410 are defined by patterning at 25 yards, rather than 40. So, even with tight chokes, the .410 is a distinctly shorter range proposition than even a 28-gauge. In a way, the .410 is to shotguns what the .22 Long Rifle is to rifles and handguns: useful for certain purposes, a lot of fun to shoot, but a gun with limitations that need to be recognized.

Having said that, there is a great deal of interest in the .410. An entire book was devoted to the subject of .410s on both sides of the Atlantic, past and present, and there are gun collectors who buy nothing else. To the best of my knowledge, this is not the case with any other single gauge.

In America today, the most beloved .410 is the Winchester Model 42 pump gun — the Model 12 scaled down and chambered only in .410. It has achieved cult status, and prices are in an upward spiral. What sets serious .410 users apart from the 28-gauge crowd is that they are not judgemental, perhaps because they are so busy defending their own choice that they don’t have time to deprecate others.

Aside from this small minority, the .410’s most common application is as a “boy’s” gun, and .410s are found in every configuration, from the cheapest of cheap doubles to Holland & Holland masterpieces. The average .410 is very light and has a barrel of 26 or, at the most, 28 inches. On a Model 42, such a short barrel is not a huge handicap, although longer would be better, but on a double it certainly is. The guns are so light and whippy, it is difficult to hit anything, even if you have an adequate shot charge.

Because of the difficulty of hitting anything, starting a child off with a .410, with any idea of turning him into a wingshot, is not doing him any favors. Repeated missing will discourage a kid faster than anything else. Yes, subjecting a child to excessive recoil is just as bad. The days in which you could give your son an Iver Johnson .410 and turn him loose with a pocketful of ammunition to roam the farm, shoot at whatever, and get the feel of it, are long gone for most of us and, with it, much use of a .410 as a training tool.

Of course, the .410 is one of the skeet gauges and, so, .410 barrels are available for any good skeet gun. They are longer, relatively heavy, and there is absolutely no recoil. They have a good swing, so if a child can handle the weight, they are useful for teaching. As with the 28-gauge, hunting with a .410 is a game of tight chokes, short ranges, and rifle-like precision of shot placement.