Writer Garry James with a sharptail grouse, taken with his vintage Westley Richards hammer gun.

Blackpowder shotguns come in all forms and configurations, from muzzleloader and pinfires to centerfire cartridge guns. Joseph Manton’s masterpieces from the early 1800s were first flintlock muzzleloaders and, later, caplock (or percussion) muzzleloaders. These established the form and principles of the modern fowling piece. Muzzleloaders are outside the scope of this book, but they are the starting point from which everything else flows. Today, many shotgunners enjoy hunting and shooting with all kinds of blackpowder shotguns, some old, others new reproductions of old designs.

Although blackpowder might be considered old fashioned or outdated, it can be almost as effective today as it was in the 1800s — and that was very effective indeed. In fact, in the early days of smokeless powder, there were many who clung to blackpowder for certain uses in which it was actually more effective than smokeless.

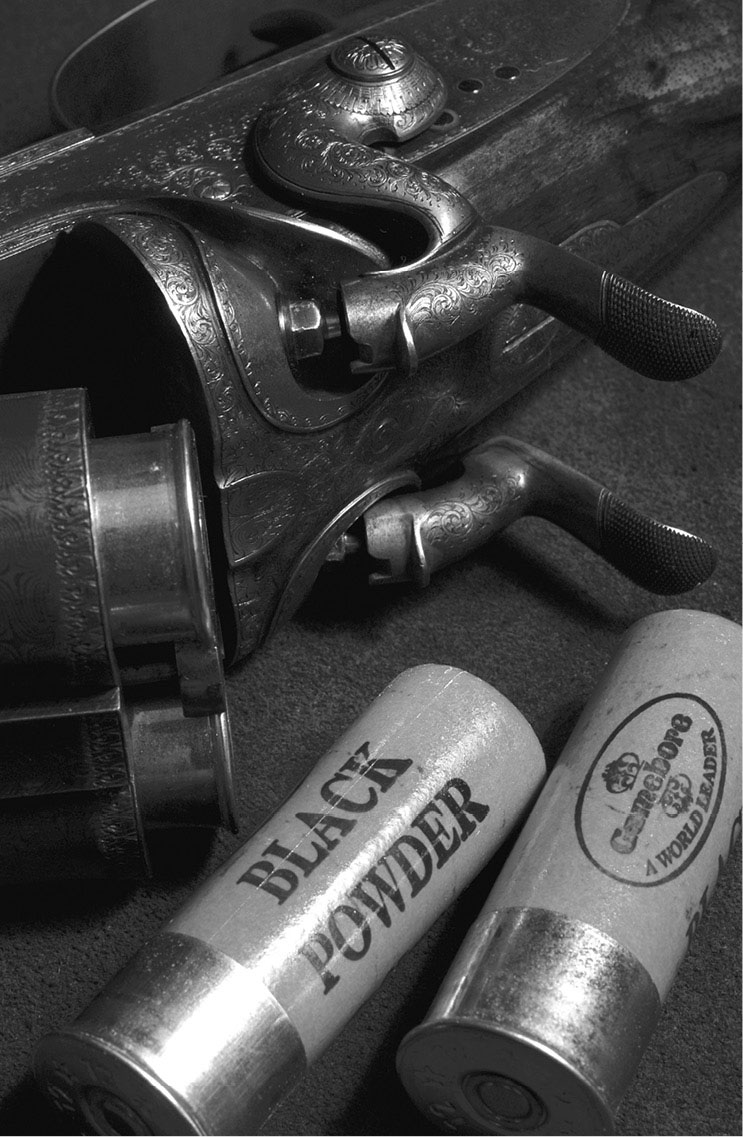

The transition from blackpowder to smokeless was not instant; with shotguns in England, it took place over the course of 20 to 30 years. Smokeless shotgun powders preceded smokeless rifle powders by a good number of years, but even by the 1890s, when smokeless powder was taking over in military rifles and cartridges, and smokeless shotgun powders had been largely perfected, many still preferred blackpowder and used it for one purpose, smokeless for another. Today, blackpowder cartridges are still loaded commercially and lend themselves admirably to the art of wingshooting, where high velocity is not required and ranges are reasonable.

Writer Garry James with a sharptail grouse, taken with his vintage Westley Richards hammer gun.

A muzzleloader is charged by pouring powder down the barrel, following it with a wad to keep it in place, pouring a charge of shot on top of the wad, and following that with another wad to keep the shot firmly in place. Generally, barrels were long, 30 inches at least, and often longer. This length was required to fully exploit the power of the powder charge.

The idea of creating a gun that would load from the breech, rather than the muzzle, dates back at least to the 1700s. From 1800 to 1850, a wide variety of methods were attempted. Some were dead ends, while others led to further developments. There were a number of interrelated problems. These included perfecting a usable mechanism for opening and closing the gun, a design for a self-contained cartridge, a means of ignition, and some way of sealing the breech against escaping gases.

Trimming paper cases to length for use in guns with shorter chambers.

Some of the fibre wads used for loading blackpowder shotshells.

Swiss gun maker Samuel Johannes Pauly patented a breechloading gun with a self-contained cartridge, in 1812. French gun makers seized on the concept and, from there, the pursuit of a practical, usable breechloading mechanism continued in France, while the more conservative British gun makers stuck with muzzleloading percussion guns and brought their manufacture to a level of high art.

A number of patents taken out through the 1830s and ’40s covered the major aspects of a workable shotgun with a self-contained cartridge. By 1851, Paris gun maker Casimir Lefaucheux had developed the break-action gun, in which the barrels pivoted to open the breech and employing a pinfire cartridge in which an expanding base wad sealed the breech against escaping gas. These were not all Lefaucheux’s inventions and patents, but Lefaucheux put it all together and exhibited two of his creations at London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. This watershed event set off the breechloading era in English shotguns.

The pinfire was the first truly successful breechloading shotgun. The pinfire shotshell resembles a modern cartridge, except that, instead of an external primer, there is an internal one with a long pin extending at a right angle out of the base. The cartridge is inserted with the pin pointing up; a tiny notch in the barrel face accommodates the pin, and the breech cannot be closed with the pin out of position. This pin is struck by the falling hammer, much like the cap on a caplock. The pin detonates the internal cap charged with priming compound, and this, in turn, ignites the blackpowder in the case.

The pinfire era in England lasted from the mid-1850s into the 1870s and established the form of the classic side-by-side shotgun. Pinfire cartridges were almost always reloaded, and brass pinfire cases last indefinitely, if not abused.

Turning the crimp on paper hulls, using a nineteenth-century “turn-over” tool.

The step from the pinfire to the centerfire shotshell, also a French development (like the break-action shotgun itself), which was introduced to England by gun maker George Daw, took place in the 1860s. Since it was easy to convert a gun from pinfire to centerfire, many owners of Lancaster, Woodward, Purdey, and other fine pinfires had them converted, rather than buy a new gun. Partly for this reason, there are relatively few pinfires for sale compared to early centerfires.

Like blackpowder itself, pinfires hung on long after they had been displaced by centerfires for everyday use. Pinfire guns are very durable, so there was a continuing demand for ammunition, and pinfire shotshells were available until at least the 1930s. The guns themselves, being considered obsolete by mainstream shooters, sold for pennies on the pound. English shotgun writer G.T. Garwood (Gough Thomas), wrote about beginning his shooting career, in the 1920s, with an old pinfire shotgun. It was all he could afford with an engineering student’s available cash, but it taught him a great deal about shotguns and shooting, and he retained great affection for them. The other small contingent of shooting gentlemen with pinfire guns who refused to convert them continued to shoot them for years, because the loads were effective and the guns handled to perfection.

In 1872, Sir Frederick Milbank, Bart., delivered one of the most astonishing wingshooting performances of all time. On August 20, on Wemmergill Moor, he downed 728 red grouse in eight drives. He was shooting a trio of Westley Richards pinfire guns and employed two loaders. His load was 7⁄8-ounce of No. 6 (American No. 7) shot over 21⁄2 drams of blackpowder. Muzzle velocity was 1,100 feet per second.

A hammer gun by J. Woodward & Sons, circa 1900, with a wild South Dakota pheasant taken with blackpowder. It was highly effective then, and it’s highly effective now.

Blackpowder has its own charms.

Factory ammunition loaded with blackpowder is still available from some manufacturers, such as this Gamebore ammunition from England. The gun (also on the previous page) is a Woodward.

The red grouse is a big, wild, hard-flying bird, and shooting driven red grouse is the toughest assignment in wingshooting. By 1872, centerfire cartridges had largely crowded out pinfires. In fact, both hammerless centerfire guns and the early smokeless powders were already looming on the horizon. Yet Sir Frederick stuck to his Westley Richards pinfires and blackpowder cartridges, because they were so effective for him and he was so effective shooting them.

This is a good place to deal with the question of drams (or drachms) and gunpowder measurement. The dram is most famously used in connection with blackpowder and Scotch whisky (“a wee dram”), and outside of certain apothecary shops, that is where it is found today. The dram hung on long after smokeless powder displaced blackpowder in most applications, and it appears on shotshell boxes today in the words “dram equivalent” or “Dr. Eq.,” as explained in the previous chapter. For a century, shotshell velocities were indicated by this term, which denotes an amount of smokeless powder that is the equivalent of a dram of blackpowder. The dram itself is a unit of both mass (weight) and volume, and there is a liquid dram as well (hence the Scotch). In weight, a dram is 1⁄16-ounce, or 27 grains.

It should be obvious that one dram of blackpowder will propel a lighter load of shot at a higher velocity than it will a heavier one, so the term is less an indication of actual velocity than it is relative power. Even today, when many shotshell boxes display measured muzzle velocity, they still include dram equivalent, because it means something to many shooters. Eventually it will disappear, but, when it does, an interesting facet of shotgun shooting will disappear with it.

Blackpowder shooters today measure powder either by grains or bulk measurement. With blackpowder, it is more important to fill available space, leaving no air pockets, than it is to get the exact weight of powder. In this regard, blackpowder is much more forgiving than the faster-burning smokeless shotshell powders.

Components for loading a blackpowder ball for a 20-bore hammer gun.

Seating the over-powder wad in a 20-bore brass hull.

Crimping the mouth using a vintage (and rare) bronze Kynoch crimping tool.

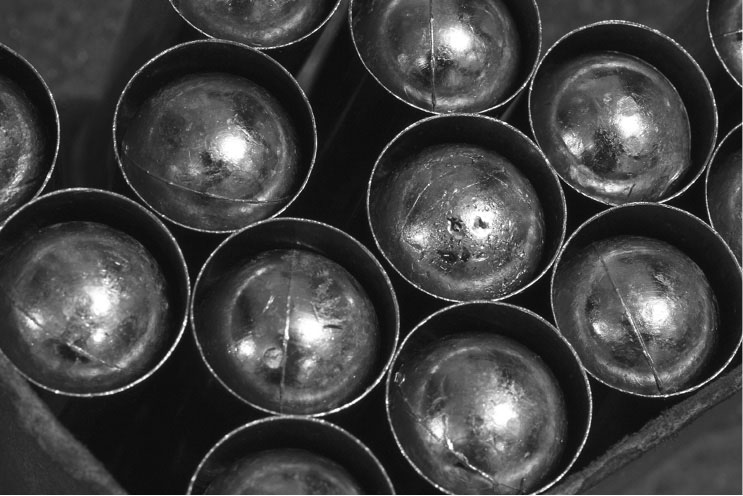

Twenty-bore ball loads ready for crimping.

Pinfire cases are still available in different shotshell sizes, and reloading kits can be purchased for them. Centerfire blackpowder cartridges are commonly reloaded, because factory ammunition is expensive. Added to that, since blackpowder is classed as an explosive by the U.S. government, the ammunition is more expensive to ship. If you have a vintage shotgun, it is fun to load for it, using paper or brass cases and equally vintage loading equipment.

One caution must be added for anyone intending to load blackpowder cartridges and hoping to duplicate performances from years past. The blackpowder available today is not as good as the powder used in the 1880s. The powder acknowledged to be the best available in the 1880s was Curtis’s & Harvey’s No. 6 (Extra Strength). Cartridges loaded with it were tested using the first chronographs, which were very accurate, as well as various penetration tests that were popular in England. Results from modern reloads using Goex and imported blackpowders simply don’t attain those velocities.

In a world where we are accustomed to looking at modern products and proclaiming their superiority, this may sound surprising, but it’s true. When you consider it, it should not be. In those days, there were many types of blackpowder on the market, it was in common use, and competition was fierce among powder manufacturers to have their products loaded by both famous commercial ammunition makers and gun makers, as well as by home loaders. As with any field where there is intense competition, products improved and losers fell by the wayside.

Today, we are forced to make do with what we can get. In fairness to Goex, Elephant, Graf’s Schuetzen, and various other European powders, they deliver good performance and are readily available. Too, powder quality is not the only factor affecting today’s performance of blackpowder, compared to that of 120 years ago. Primers are different, cases and case capacity are not the same, and wads are often made up from whatever we can find, rather than cut from prime feltine or natural cork.

The Kynoch crimping tool and finished round (20-bore ball).

Paper hulls are by far the best (and some consider the only) hulls to use with blackpowder. These 20-gauge paper hulls are not easy to come by.

Cast slugs for the 20-bore.

The author shooting an E.M. Reilly 20-bore hammer gun from the 1870s that began life as a .577 Snider double rifle, travelled the world for more than a century, and was later bored out to become a 20-gauge shotgun. At close range, it is deadly with ball, buck-, or birdshot.

If there is one serious problem with blackpowder, it is cleaning and corrosion. Blackpowder is unapologetically messy. It leaves hands black and bores coated in a greasy residue. When you get home from shooting, you need to clean your gun immediately or risk corrosion. The same is true of brass shotshells. Left uncleaned, brass shotshells deteriorate and become brittle, while blackpowder residue left in the bore or coating the standing breech may lead to rust and pitting.

The problem as it exists today is not exactly what it was in the 1860s, because the chemical compounds used for priming are not the same as they were then. The major concern now is chemical reactions among these different compounds. Since no one can predict exactly what will happen when primer “A” ignites powder “B,” the safest course is to clean immediately and clean thoroughly. Fortunately, the main cleaning agent for blackpowder is soap and water, which, together, takes care of both grease and salt compounds. A fouled bore can be rendered clean as a whistle with little more than a basin of hot water, some dish detergent, and a cleaning rod and mop. You do not need to buy expensive blackpowder solvents, which seem to consist mostly of detergent anyway. Once the black grime is out of the barrel, ensure that it is absolutely dry and then apply a thin coat of oil. Much the same process will do for brass cartridge cases (except for applying oil, of course). Paper cases do not need to be cleaned, because the powder residue does not come into contact with anything that can corrode, and paper cases are generally worn out after two or three firings anyway.

Blackpowder 20-bore loads for a variety of purposes, some sporting, some not.

A German pinfire gun with ammunition made by Bob Hayley (Hayley’s Custom Ammunition), from modern centerfire brass hulls. Pinfires are always loaded with blackpowder.

Entire books have been devoted to the care and feeding of blackpowder firearms of all kinds, and anyone interested in shooting blackpowder should acquire one and read it carefully. The Lyman Blackpowder Handbook is a comprehensive guide to every facet of loading and shooting blackpowder. The main thing to remember, even if you are an experienced handloader accustomed to using smokeless powder, is that blackpowder is an explosive. Although it creates lower pressures and is more forgiving in the gun itself, blackpowder outside the gun — in canisters, powder measures, or open cartridges — is more volatile and hazardous than smokeless. Makers of old loading implements avoided the use of steel wherever possible, because of the possibility of sparks. The main materials used were brass and German silver. Static electricity is an equal hazard, to say nothing of cigarette ash.

• • •

There are mixed views on blackpowder and plastic, whether used in hulls, shot cups, or wads. Some say they work perfectly well, others that the ignition of blackpowder will melt or soften plastic, leading to serious plastic fouling in the bore. Unless you have no choice in your use of components, my suggestion would be to avoid the use of plastic, and not just because of the possibility of fouling. Garry James, former editor of Guns & Ammo and a serious devotee of blackpowder, is of the opinion that any gun or rifle made for blackpowder should be shot only with blackpowder, not with any equivalent smokeless propellant or blackpowder substitute. This is partly a matter of correct form and the rightness of things (which, of course, is a personal matter for everyone), but also because that was what they were made to shoot and shooting anything else raises the risk of damaging the gun or altering its shooting qualities.

Modern blackpowders, from Germany (left, imported by Graf & Sons) and America. Goex is part of the Hodgdon Powders conglomerate.

Vintage loading tools, still eminently useful today.

With English or European guns, which have been specifically proofed with blackpowder and not with any nitro (smokeless) powder, it is certainly safer to stick with blackpowder. By the way, the normal term for smokeless powder proof is “nitro proof,” and the word “nitro” stamped on the barrel or action flats is an indication of this. Just because a gun has been proofed with blackpowder only does not mean it is not safe to use smokeless powders in prudent loads, only that the proof house has not said it is.

During the transition from blackpowder to smokeless, both rifle and shotgun ammunition were produced that were termed “smokeless for black.” These were cartridges loaded with certain smokeless powders to blackpowder pressures and intended for guns proofed only for blackpowder. In the United States, some early smokeless powders were produced that were intended for the same purpose and were measured by their bulk, not by weight. The use of “bulk shotgun” powders continued until well into the twentieth century and, as late as the 1960s, shotgun writers referred to loads using bulk powders.

As you can see, there are many grey areas between the use of blackpowder and smokeless, and this is ground that must be trod carefully if you have an old shotgun and want to shoot it. There are tens of thousands of perfectly good guns, ranging in age from 100 to 150 years old, that can be shot, hunted with, and generally enjoyed in perfect safety and with very satisfying performance, provided they are given the right loads. This is, of course, also provided the owner does not fall prey to the modern disease of seeking to push performance to the limit, packing in more powder and shot and trying hotter primers to get more velocity in an effort to show up the other guy and his old gun.

This old powder measure can be set to measure powder from 21⁄2 to 5 drams.

It is good to keep in mind that, with a shotgun, pattern is everything. Some fine old blackpowder shotguns were carefully bored and choked to deliver exemplary patterns with a particular load and a specified number of blackpowder drams. Load them accordingly, and you will get lovely performance. Try to step outside those boundaries and you run the risk of ruining patterns or worse. Perhaps, though, this is not really a problem, since the big challenge for modern blackpowder shotgunners is merely equaling the wonderful performance of these guns in 1880, rather than exceeding it.

• • •

In 1905, one of the less well-known British shooting writers, Alexander Innes Shand, wrote about the transition from muzzleloaders to breechloading shotguns, regretting the fact that modern shooters were relatively ignorant about their firearms. In the days of blackpowder, when it was necessary to dismantle a gun every time you returned home to check its mechanism and clean and oil the bore, every shooter, whether lord or gamekeeper or vicar, knew a great deal about his gun and how it worked. In modern times, with its non-fouling ammunition, Shand wrote that too many shooters ignore their gun as much as possible and, as a result, really know very little about them.

In the intervening 108 years, this situation has become a thousand times worse. Because modern powders and primers are non-corrosive and newer steels and alloys used in shotguns are either rust-free or corrosion-proof, it is hardly necessary ever to clean a shotgun and, so, many do not.

You must know, though, that, when you take up blackpowder shooting, it requires a complete change of attitude, one from regarding your gun as an inanimate object that requires little or no attention nearly to the status of a pet that requires daily care and constant observation. Left to themselves, old blackpowder guns seem almost to attract rust and fouling. If you cannot afford the time or don’t want to make gun care a labor of love and an adjunct pleasurable activity to the shooting itself, then perhaps blackpowder is not for you. If, on the other hand, you love to sit by a fire and read about the great shoots of the nineteenth century, to sip a little single malt and reflect on life as a laird, to take a quiet hour to spend with your gun and a bottle of Rangoon oil, then very likely you would find yourself right at home in the world of blackpowder shotguns.

Blackpowder paper, from Gamebore, in glossy hulls of rifle green.