The buttstock of a Galazan (CSMC) Model A-10 Sporting. Made for shooting from the “gun up,” or pre-mounted position, it is adjustable for comb height, length of pull, cast, and angle of butt plate.

Photo by John Giammatteo

Shotgun competition is one of the oldest of all sports still in existence. It began in Europe in the 1700s, and the first recorded events occurred in England, in 1792, almost 25 years before Wellington defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo.

The first competitions were live-pigeon shooting events, in which captured birds were released and shot under controlled conditions. From the beginning, pigeon shooting involved betting, and sometimes very substantial sums of money. Not coincidentally, this was the era of the Manton brothers, John and Joseph, who are credited with turning the fowling piece from a crude implement into a refined tool. This evolution was due in no small part to pigeon shooting.

Up until then, fine gun making had been limited to dueling pistols. Taking a cue from the importance of such firearms needing to be dependable in the heat of the moment, gun makers like Manton and, later, Lancaster and Purdey understood that, when hundreds of pounds were at stake, having a gun that was utterly dependable, fit properly, and was well balanced could be the difference between survival and bankruptcy. It was many years before other game guns caught up to pigeon guns in sophistication and workmanship.

The buttstock of a Galazan (CSMC) Model A-10 Sporting. Made for shooting from the “gun up,” or pre-mounted position, it is adjustable for comb height, length of pull, cast, and angle of butt plate.

Photo by John Giammatteo

A rarity in the modern world: A side-by-side made specifically for shooting sporting clays.

Photo by John Giammatteo

There are various types of pigeon shooting, but the two in existence today are “box pigeon” and columbaire.

In box-pigeon shooting, the birds are held in boxes (traps), five in a line and five yards apart from each other. The shooter stands 29 yards back from the center trap, calls for a bird, and one is released at random from one of the five traps. The bird then must be downed, “grassed” is the term, inside a fenced ring surrounding the field. Shooters are awarded handicaps that determine whether they stand at the 29-yard line or farther back in one-yard increments back to 35 yards.

In columbaire, the pigeon is thrown by hand, rather than released from a trap. Most widely practiced in South America, this is really a contest between the columbaire (thrower) and the shooter, much like a duel between a pitcher and a batter, in baseball. The throwing ring is square, outlined by a surrounding rope 10 feet above the ground. Another rope divides the square into two rectangles. The thrower is in one rectangle, the shooter in the other, and both can move within their respective rectangles. The bird must be thrown over the rope in any direction. As in box-pigeon shooting, the bird must be downed inside a fenced, circular ring, otherwise it is counted as lost.

In the early years in Europe, shooting clubs used starlings, sparrows, and other birds, when pigeons were not available. Pigeons were expensive, so pigeon shooting became a big-money competition in every way. Then, as pigeons became either too costly or unobtainable, various kinds of artificial targets were created. This is the origin of trap shooting, the oldest shooting game involving artificial targets.

Because of the need not only to kill the bird, but also to drop it within an enclosed area, pigeon guns have tight chokes and hard-hitting loads. Guns and loads for pigeon shooting eventually became standardized. Upper limits were placed on both shot loads and powder charges. Rules were also established that limited gauge sizes.

Box-pigeon guns are very high quality, and this is the root of the “pigeon grade” often associated with shotguns. Eventually, the standard charge for a pigeon load became “1⁄14 - 3⁄14” — that is, 11⁄4 ounces of shot, propelled by 3⁄14 drams of blackpowder. Pigeon guns were heavier than standard weight, to absorb recoil, and had long barrels and tight chokes. In England, they were chambered for 23⁄4-inch shotshells and often had heftier frames with features like third bites and side clips, for additional strength and stability.

Columbaire guns more closely resemble game guns. The first shot is generally at closer range, and the first barrel has a more open choke. These guns are still heavy, however, to absorb the recoil of the substantial load.

In both games, the shooter is allowed two shots at each bird and, in some instances, required by the rules to fire both barrels regardless. Pigeon guns are always doubles, traditionally side-by-sides, but, in more recent years, over/unders, as well.

The author in practice for the real thing, in this case, shooting clays coming at random off a hill top. He is working with a “stuffer.”

Unlike trap and skeet, where hundreds of shots are fired in a day of competition, pigeon shooting involves much smaller numbers. A 30-bird “race” is typical for a day’s shoot, with 15 birds in the morning and 15 in the afternoon. A two-day shoot would total 60 birds. This means there is much more care and deliberation taken with each shot, and the pace is much slower. Pigeon shooting is much more difficult, shot for shot, than trap. Even the very finest pigeon shooters rarely kill 30 birds in a row and, in a 60-bird match, the winning score is very likely to be 56 or 57 grassed birds.

An interesting aspect of pigeon shooting is that the shooters are absolutely top-flight. Many turn to pigeon shooting, because they had conquered all the fields that trap had to offer. At the same time, and although there are substantial purses on the line, the atmosphere is unfailingly friendly and congenial, unlike the cutthroat (and sometimes neurotic), world of trap.

The modern sport of trap shooting came about for two reasons, the expense of live-pigeon shooting and objections to it on humanitarian grounds.

The development that made trap shooting possible was the invention of the round clay disc, in 1880, patented by the American George Ligowsky. Until that time, various types of targets had been tried, including glass balls, balls filled with feathers, and wooden cubes. All had drawbacks. Some didn’t present enough of a challenge, others created too much litter. The clay target was the breakthrough that made trap shooting possible.

Trap’s layout, procedures, rules, and terminology all flow from box-pigeon shooting, with the exception of the fact that, instead of competitors shooting individually, one at a time, shooters compete in squads of five, each firing one shot in turn and rotating back through the line, in turn, until all have fired the full game.

Blaser gun maker Andre Gorjup adjusting the stock of competitor Alison Caselman’s Blaser F3 tournament gun.

The term “trap” comes from pigeon shooting, as does the clay “pigeon.” (In England, trap shooting is called “down the line” or DTL, to differentiate it from pigeon shooting.)

The traditional call of “Pull!” originated with pulling a cord to open a trap and release a bird, and the machine that launches clay pigeons is called a “trap.” The trademark Blue Rock of some clays actually comes from blue rock pigeons, the favored species for live-pigeon shooting.

In trap shooting, the trap itself is housed in a sunken building 16 yards in front of the line of shooters. The trap oscillates from side to side, out of sight of the guns. When the shooter calls “Pull!” the trap releases the bird at whatever angle the oscillating trap is pointing at the time, which gives a variety of shots ranging from hard lefts to straightaways to hard rights, and these angles change as shooters rotate from station No. 1 through station No. 5. Each shooter gets five shots at each station, then moves to the next, to shoot a total of 25 for the match.

As an interesting side note, our own famous Grand American trap shooting championship originally used live pigeons. The last live-pigeon competition was held in 1902. Since then, the Grand has been clay pigeon only.

Trap guns are the most specialized of all shotguns, and the game itself has been referred to as rifle shooting with a shotgun. Trap is shot with 12-gauge guns; while there is no rule against using a smaller gauge, there are no special classes, and no allowance is given for using one.

The clays are broken at anywhere from 32 to 45 yards, depending how quickly the gun gets on the bird, and, so, trap guns are long-barreled, heavy, and tightly choked. Because 16-yard trap is shot one clay at a time, the single-barrel trap gun became an American specialty, with superb guns produced by Parker, L.C. Smith and, most famous of all, Ithaca. The legendary Ithaca Single remained on the market right up until the 1980s, in production long after Ithaca doubles had been abandoned. Today, fine single-barrel trap guns are produced by Browning and Perazzi.

In trap, the gun is mounted to the shoulder, with the safety off, before the shooter calls for the bird. Because of this, trap guns have long, straight stocks, with Monte Carlo (raised) combs, and beavertail or oversized fore-ends that provide a firm grip. The guns are heavy, typically nine to 9⁄12 pounds. Traditionally, single-barrel dedicated trap guns have no safety, because they are never loaded until it is the shooter’s turn.

By game gun standards, trap loads are relatively light — no more than 11⁄8 ounces of shot at moderate velocities — and trap guns themselves are heavy. The damaging effects of recoil, especially the development of a flinch, is cumulative, with many light loads having as bad an effect as a few heavy loads. Trap shooters fear a flinch above all things, because hesitation in pulling the trigger inevitably means a lost bird. This is a game where runs of 100 straight are common, and the loss of even one bird means an early exit from competition.

There are many variations on trap. Handicap trap moves shooters back as far as 27 yards from the trap house, to increase difficulty, and handicap loads are more powerful than standard shells. A shooter’s handicap is determined by his record in registered competition. Doubles trap follows the same basic format, except two birds are thrown each time. The doubles trap does not oscillate. Instead, variation in the targets is achieved by the shooters rotating through the five stations, thereby seeing the targets from different angles. A standard round of doubles trap is 50 shots, instead of 25.

Alison Caselman at low house No. 7 on the skeet range. The other members of the team are watching where the clay will break. Alison’s gun is pre-mounted and pointed to where the clay will be, not where it is.

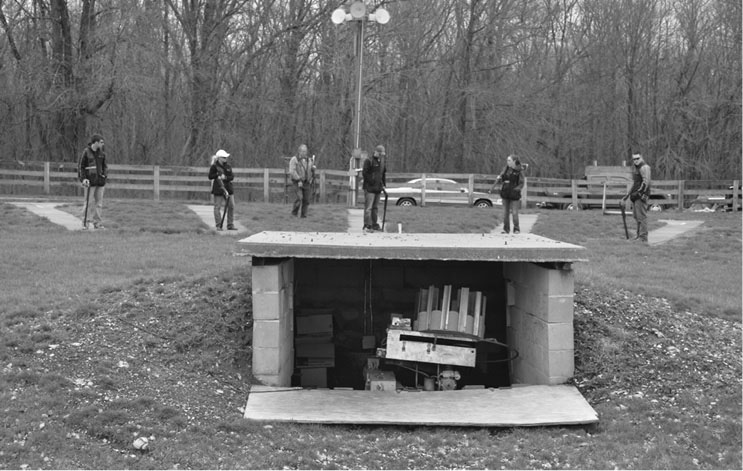

Trap shooting from the 16-yard line, as seen from beyond the trap.

Another angle on a trap-shooting layout.

Yet another angle on trap. Most trap layouts overlay a skeet field, allowing the club to make maximum use of available space, hence the view of the skeet high house, although the team is preparing to shoot trap.

Preparing to shoot trap. The view from behind the shooters.

• • •

During the 1980s and ’90s, as sporting clays roared to popularity, trap shooting saw a decline in interest. Partly this was due to the intense regulation of every aspect of it, and partly it was due to the fact that perfect scores had become the norm and many high-level matches had become endurance contests, as much as anything. Sporting clays offered variety, a change of pace, and new challenges for shooters.

A side effect of this decline in interest in the game of trap was that very high-quality used trap guns became available at bargain prices. This was particularly true in the state of Arizona, because legend had it that Arizona was where old trap shooters went to die. For many years, you could hardly give away the old classic single-barrel trap guns. Today, the pendulum has swung back in the other direction, largely because of collegiate shooting. For college teams and young shooters, trap is the perfect game. Fields are available, they are identical, a score shot on one corresponds to another, it lends itself to team participation, and competitors can see exactly where they stand in intercollegiate competition. As a result of this renewed interest, there has also been an upsurge in new trap guns. Almost all are over/under doubles, although some also offer an interchangeable single-barrel.

Another view of trap.

Not surprisingly, with a game as old as trap — it has been an Olympic event since 1900 — there are variations found in different parts of the world, and even from club to club. One is known as “wobble trap,” a game in which the trap oscillates up and down, as well as side to side. Others include allowing two shots at each bird and scoring more (or less) for each break, depending on whether it was hit with the first or second shot. Anyone shooting trap at a new club should check for any local rules or peculiarities, especially as they regard guns, safeties, allowed shots, and chambering cartridges.

International, Olympic, or bunker trap is the usual game shot outside the U.S., and, until in very recent years, there was only one true international setup in the entire country. Today there are several, as well as modified 16-yard trap fields that allow for a simulation of international competition. While Olympic trap has the same origins as American trap, it has grown into quite a different game and is generally considered to be much more difficult and demanding than 16-yard trap.

An international field has five stations for shooters and employs five sets of three traps each. There is a set of traps below each station, one pointing left, one right, and one straight. Instead of shooting five birds at each station before moving, each shooter in this game moves after each shot. To save time, a squad consists of six shooters, with the sixth moving from station No. 5 back to behind station No. 1 after each shot. This keeps the game moving.

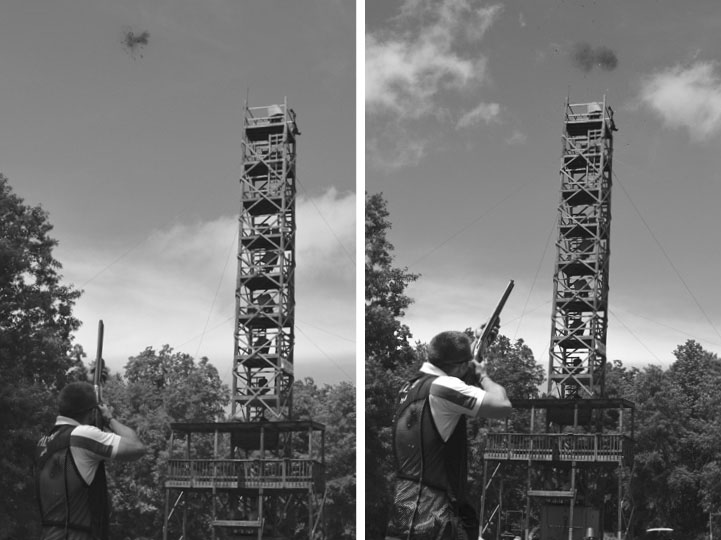

The bird is in the air, approximately 32 yards out (and fleeing fast).

The traps do not move. They are computer-programmed to throw each shooter a total of 25 birds — 10 right, 10 left, five straight-away — but in a random sequence. The computer keeps track of which shooter is at which station and which birds he or she has already seen. A standard round is 125 shots for men, 75 for women. The targets are thrown at a much higher speed than in American trap (62 miles per hour, versus 40). Originally, the gun was held below the shoulder, rather than mounted, and two shots were allowed at each bird. Olympic competition now allows only one shot. The maximum shot charge is also regulated, with 24 grams (7⁄8-ounce) the maximum allowed, but at higher velocities of 1,400 to 1,500 fps.

International trap layouts are very expensive and, until relatively recently, only one existed in the entire United States. Even today they are rare. To provide practice for aspiring Olympic shooters, some trap clubs have created simulated international fields, allowing two shots per clay, setting the traps to throw harder targets, and rearranging stations and trap houses so the shooter is above the trap. Because international trap shooters fire two shots in rapid succession, there is a premium on speed and reduced recoil. Emphasis is placed on getting the shot out to the fleeing target as quickly as possible.

From its beginnings, trap shooting was intended to simulate live-pigeon shooting and had no relation whatever to game shooting. As trap became more and more formal and rigid and its guns more specialized, hunters began looking for an alternative that would provide practice in the off-season for hunting grouse, pheasants, and other game birds later in the fall.

The answer was skeet, a game formalized in the U.S., in 1926, and named for the Norse word for “shoot.” The moniker was suggested in a national name-the-game contest won by a lady named Gertrude Hurlbutt. Miss Hurlbutt went on to become one of the foremost female skeet shooters of her day.

Skeet is quite unlike trap in every way except the clay pigeons themselves. There are eight shooting stations laid out in a semicircle, numbered from one to seven. There are two trap houses, one throwing a high bird, the other throwing a low bird. Station No. 1 is directly beneath the high-house trap, station No. 7 beside the low house. Station No. 8, the last shooting station, is halfway between the two houses, on the straight line between them.

The traps themselves are fixed in position and do not move at all, throwing each bird exactly the same. Ideally, every bird thrown from each trap will be identical in flight. The only variety is the angle provided by the movement of the shooter from station to station. Birds are shot in singles and doubles, depending on the station, and a round of skeet is 25 shots. On the double stations, one high bird and one low bird cross in the air.

The low house at skeet, with the team on station No. 7.

In skeet, the average bird is broken around 22 yards, so skeet guns have little or no choke. A typical skeet gun might have 26- or 28-inch barrels, choked Skeet No. 1 and Skeet No. 2, both of which are close to Improved Cylinder. Unlike trap, which is strictly a 12-gauge game, skeet is shot with 12-, 20-, and 28-gauge, and .410-bore guns, and a registered match includes rounds shot with all four.

Originally, skeet was shot with the gun down and the safety on. After the call “Pull!” the gun was brought to the shoulder and the safety slipped off as the gun was raised. Today, American skeet is shot, like trap, with the gun mounted and the safety off. As a result, new skeet guns more closely resemble trap guns than game guns, with long barrels, thick fore-ends, and Monte Carlo stocks.

Ryan Mason on a simulated ruffed-grouse station of a sporting clays range. Sporting clays offers a virtually unlimited variety of conditions and terrain.

Sporting clays can be varied by adding different levels to the shooting platform. Here, Alison Caselman shoots a flushing grouse from the high platform.

Just as trap and skeet are quite unlike one another, so, too, are trap shooters different than skeet shooters. Arguments continue as to which game is the more difficult. Trap has the element of the unexpected built into each target by its oscillating trap, and this factor gives trap the edge on difficulty. In skeet, while there are eight stations, two traps, and 20 different presentations, in the end, they are exactly alike, without deviation, time after time. Trap rounds are like snowflakes, whereas every skeet round is exactly like every other skeet round.

Originating in the Northeast, stations in skeet were intended to simulate the various flight patterns of the ruffed grouse, and the first skeet guns were typical grouse guns. As the rules became more defined, shooting more formalized, and national associations began to keep records and regulate tournaments, skeet guns became more specialized. Particularly, because of the requirement to shoot four gauges in registered tournaments, skeet guns were produced with interchangeable barrels in the four gauges. Today, the skeet gun is as specialized as the trap or pigeon gun.

Looking back at the flushing-grouse shooting platform. It offers a variety of shooting angles, both horizontal and vertical.

Skeet loads closely resemble trap loads, the main difference being the pellet size. In trap, No. 71⁄2 is standard, while skeet shooters use No. 9s.

International skeet is similar to international trap in that the birds fly faster, the regulations call for the gun to be held off the shoulder until the bird is called for, and the presentations at each station are more difficult. Anyone shooting international skeet for the first time is likely to be caught flat-footed on the first few targets. Reaction time is all important. As with international trap loads, special ammunition for international skeet uses a smaller charge of shot at higher velocities.

Alison on a simulated duck station, overlooking a pond with cattails and surrounding trees.

The game we now call sporting clays originated in England, in the 1920s, although informal variations existed at different shooting grounds well before that. It was developed as an artificial target game to give practice for game shooting.

The English shooting grounds, complete with practice targets and professional instruction, dates back to the 1870s. Different grounds installed target stations that simulated the various shots you were likely to see in the field while hunting game, everything from bounding rabbits and incoming grouse to high pheasants launched off a tower. Some shooting grounds put in “grouse butts,” actual shooting butts sunk into the ground, with clays thrown at them in twos, threes, and packs, completely at random. Today, these are run by computer programs and offer 50- or 100-shot flurries. With a loader and two guns, it is more fun than can be imagined.

It was a short step from these practice stations to entire courses, stringing together eight or 10 stations, shooting 50 to 100 cartridges per round. Originally, they were to be shot with standard game guns, which were held gun down, safety on, exactly as one would approach a point over a dog or wait for an incoming grouse.

Ryan Mason, shooting birds off the high tower at Prairie Grove Shooting Sports, near Columbia, Missouri. The tower is 90 feet high, with more than a dozen traps throwing birds in every direction from 10 different levels. Although towers have been common in England for many years, they have only really made an appearance in the U.S. in the last 25 years or so. They offer a tremendous variety of shots at all heights and angles, including incoming, crossing, and outgoing.

The first sporting clays course in the U.S. was set up near Houston, in 1984, by Bryan Bilinski, who then worked for Orvis and now has a gun shop in Traverse City, Michigan. By 1984, both trap and skeet were losing popularity. Trap was seen as an old man’s game, shot with archaic guns, a game repetitive and formal, with little or no relevance to game shooting. Skeet wasn’t much better, shot by rote, with runs of consecutive breaks into the thousands. Shooters were bored.

Americans took to sporting clays with joyous cries, and new clays courses spread throughout the country like dandelions in spring. By the mid-1990s, everyone seemed to be shooting sporting, and the first dedicated sporting clays guns were coming onto the market. The popularity of sporting clays was credited with keeping the gun manufacturers solvent for more than a decade, and there was a vigorous revival in the shotgun market, as a result.

As a game, sporting clays was supposed to present realistic game-shooting situations, from incoming to outgoing to crossing birds, in various combinations. There were bounding rabbits and springing teal, and each station was given a fanciful name and natural features like ponds, thickets, and heavily wooded shooting alleys were employed to add realism. A day at sporting clays was like a nature walk with a shotgun.

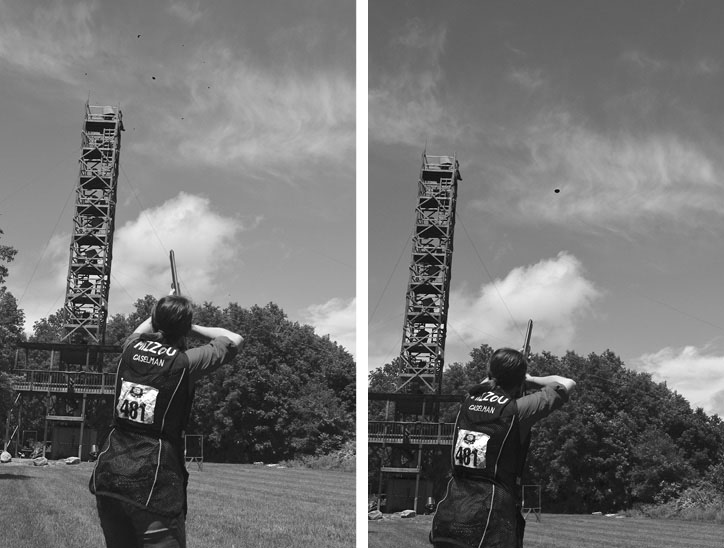

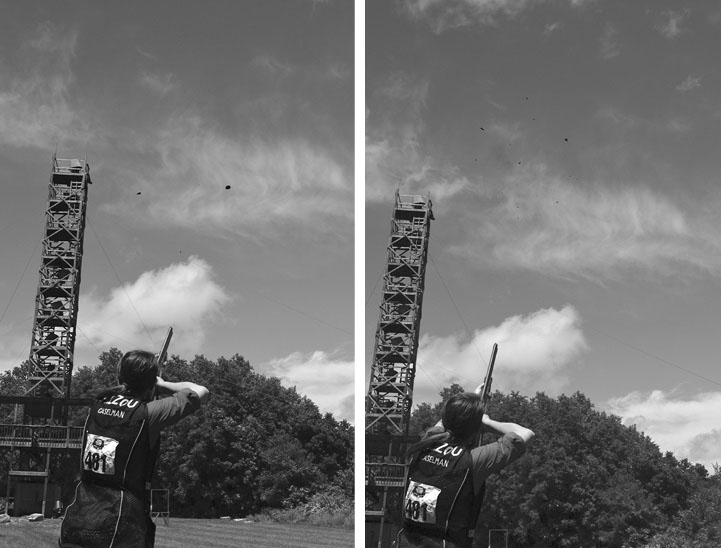

Alison Caselman shooting clays from the high tower.

As well as the standard trap or skeet clay pigeon, clay targets were developed in new sizes and shapes. There were smaller, faster ones, mid-sized standard clays, and ultra-hard disc-shaped clays to bound along the ground like rabbits. Some are thrown upside-down to give a looping arc.

It was not long before the American mania for standardization, score keeping, and national rankings led to fundamental changes in the game of sporting clays, something that guided it, at least in part, down the same path skeet had trodden 75 years earlier. Every skeet range, by regulation, is exactly the same as every other, making national rankings possible. Sporting clays ranges, however, are like golf courses. Some are more difficult than others.

The first major change to sporting clays was to allow shooters to call for the bird with the gun already mounted and the safety off. This simple change set in motion a train of events. Suddenly, some targets were too easy. So, they were made more difficult, and this, in turn, led to the development of harder-hitting, faster loads. These firecrackers required heavier guns to tame the recoil, while birds thrown at greater distances demanded longer barrels. Pretty soon, the average “sporting gun” was as elaborately specialized as any trap gun, complete with 34-inch ported barrels, Monte Carlo stocks, an array of interchangeable choke tubes you’d need a computer to keep track of, and golf carts to carry it all between the stations. The sporting clays shooter who still wanted to use his hunting gun and get in some fun and practice in the off-season suddenly found himself faced with targets that bore no resemblance to any shot you would see in the field, and ones you’d never dream of shooting at if you did. Sporting clays became a game for the obsessively competitive, complete with scorecards, lifetime records, and national rankings, just like trap and skeet. Now, at many shooting clubs today, you find different sporting clays courses, ranked by difficulty of targets, which allow the average hunter with a pump gun to get in some realistic practice, while across the way the dedicated sporting shooters with their $10,000 over/unders can compete against each other to their hearts’ content.

One benefit of all this, aside from enriching the shotgun and ammunition makers, has been a proliferation of imaginative shooting stations and presentations. High towers that throw clays from 30 yards up and everything in between are now to be found in every state, and some of them rival the towers used to simulate high pheasants in England. This makes top-level shotgun practice widely available where it never was before.

As for guns, shotgun makers have been frantically producing dedicated sporting guns. Almost all are over/unders, with a scattering of semi-autos and pumps. Someone wanting to shoot all the competition disciplines can buy a gun like the Blaser F3 and get interchangeable buttstocks and fore-ends and a wide variety of barrels in every gauge, and use one gun for everything, merely changing the configuration according to what they want to shoot that day. A state-of-the-art sporting gun with 34-inch barrels can change into an international trap gun, from there into a .410 skeet gun, and from there to a game gun to shoot quail over dogs, using nothing but a hex wrench.

The games just described are the most widely practiced of the shotgun sports, but there are several others, with new ones appearing, it seems, all the time.

Alison and Prairie Grove owner Ralph Gates.

Cowboy Action is easily the most colorful. Competitors dress in Old West clothing, give themselves names like “Rattlesnake Rick,” and shoot blackpowder revolvers, lever-action rifles, and hammer shotguns. Everything possible is done to make the competitions realistic, from the configuration of the guns involved to the loads allowed. Cowboy Action enthusiasts can become as deeply involved as Civil War re-enactors, in getting every period detail exactly right. The shotgun side, shot mostly with reproduction hammer guns, involves blackpowder, buckshot, and stationary targets. The gunfight at the OK Corral, in which Doc Holliday is believed to have used a double-barrel 10-gauge hammer gun, is a favorite theme.

At the other end of the scale, in gentility, if not moderation, are the Vintagers, formally known as the Order of Edwardian Gunners. These are enthusiasts of the English shotgun, the great driven shoots at Sandringham and Holkham, and the exploits of Lords Ripon and Walsingham. Participants dress in Edwardian suits and gowns and use vintage Lancasters, Woodwards, and Purdeys, with and without hammers, in a variety of competitions using clay targets. The proceedings usually include an Edwardian lunch or evening gala.

Devotees of the black guns have their own modern discipline, 3-Gun shooting. Like Cowboy Action, 3-Gun uses handguns, rifles, and shotguns. These firearms, however, are ultra-modern. A dedicated 3-Gun shotgun will have an extended magazine, collapsible stock, red-dot sights, and flashlight under the muzzle. The shooting simulates combat or self-defense situations. While the Vintagers shoot at clays in the air, shotgun targets with both Cowboy Action and 3-Gun are more likely to be stationary, representing bad guys shooting back at you, rather than driven grouse in flight.

Ryan Mason and Alison Caselman shooting doubles off the high tower.

The high tower also has a shooting platform for shooting out-going birds at all heights.

On the live game side of things, there is a worldwide pig scourge, with feral hogs of all kinds, from domestic pigs gone wild to genuine wild boar and various crossbreeds in between, overrunning plantations and farm fields from Texas to Germany. Shooting driven wild boar has been a staple of European hunting for centuries. In America, hunting the many hogs that are devastating agriculture and destroying other species is becoming both a hunting activity and an exercise in survival.

While most hog hunting is done with rifles, driven boar can be taken with shotguns loaded with buckshot, and some shooting clubs have created simulated driven boar games, with the role of the pigs played by everything from trash-can lids to five-gallon buckets and, in one immortal instance, pumpkins. Buckshot is the preferred ammunition but, depending on the range, birdshot also works well.

The tactical shotgun in competition use. This is Brittany Workman, of the Top Gun indoor shooting range, in Missouri, shooting bowling pins with a Benelli. While this gun is outfitted for 3-Gun competition, it is an equally good working tactical gun for home- and self-defense.