Shooting instructor Vicki Ash (right) demonstrating a shooting technique to the author.

Shooting instructor Vicki Ash (right) demonstrating a shooting technique to the author.

Everyone learns to shoot in some way. Learns. No one is born with the skill, although there is an element of natural talent. Everyone, however, must learn the mechanics of shooting before even the natural ability of the “born shot” can assert itself.

Some buy a gun and a box of shotshells and take it from there, for good or ill, acquiring bad habits along the way. Others are taught by a well-meaning relative. Some read books about shooting and try to apply the lessons, and others go to a local range and look for an instructor.

Shooting is a skill that requires a certain amount of theoretical knowledge and a great deal of practical application. Often, sitting around a gun club you will hear that “The best teacher is a case of shells!” This has some truth to it — certainly, you would learn from shooting a case of ammunition, which amounts to 250 shots, or about 10 rounds of skeet or trap. If that was all you did, however, you would be far more likely to acquire ingrained bad habits than to become a competent shot.

The author (shooting) and Vicki Ash, at the Ashes’ instruction ground near Houston.

For some reason, Americans especially have the belief that they are “natural” shots, born to carry a gun and hit what they aim at. For years, the very idea of a shooting school was anathema, an insult to their manhood. Yet handling a gun is as much a skill as that of driving a car, and no one questions the value of formal driving instruction before allowing a teenager out on the road at the wheel of a potentially lethal weapon.

Gil Ash and author, at the Ashes’ instruction grounds.

This attitude has changed somewhat and, in the United States today, there are many different levels of shooting instruction available. Almost every range has at least one member who offers shooting instruction on a formal or informal basis, and the NRA has a system of classifying and qualifying shooting instructors in every shooting discipline. In this way, the prospective student has at least an idea of the qualifications of the instructor, before paying a dime or firing a shot.

There are also formal shooting schools, where you can enroll for three or four days of concentrated instruction, working with several different instructors. This is an intense and sometimes expensive approach, but, for the beginner, such a school may turn out to be the best investment in the long run. As with any skilled activity, if you start by acquiring basic correct form and, at the same time, dodge bad habits that will be almost impossible to eliminate later, you will be a better shot for life.

The very first step for any shooter seeking instruction is to decide exactly what kind of a shotgunner he or she wants to be. Do you hope to become a pheasant hunter? An informal skeet shooter? An Olympic-class trap shooter? An all-around shooter who dusts clays to keep in form for hunting? A little bit of everything? Or maybe, having not yet done any of these things, you won’t know until you try them — in which case, you’d like to start by becoming safe and competent with a shotgun.

These are vital questions, and any instructor who does not ask about your goals as a shotgunner right at the start is not a very good instructor. Chances are, he intends to make you into the kind of shooter he is, regardless your preferences.

This chapter will include a good deal of anecdotal experience, the author having enjoyed years of seeing shooting instruction at its best and worst and having met some of the finest shooting instructors in the world, as well as some who may well be good with others, but were far from good with him. I will name names, of both instructors and establishments that offer instruction, but, generally, only if I can recommend them personally. The reason for this is the very first rule for the prospective student: what works for someone else may not work for you at all.

So, back to the first question. What kind of shooter do you want to be? Let’s assume the answer is that you want to be a good, all-around shotgunner — safe in the field, a good instinctive shooter who can react to the unexpected, someone who can hold his or her own on a sporting clays range, and one who is at home with flighting doves or flushing pheasants. For this type of shooter, the best possible instruction is what I would call the “English school.” English instruction is geared toward game shooting and has been for 150 years. It teaches the student to carry the gun safely, to mount the gun only when the bird appears, and to slip off the safety only as the gun comes to the shoulder. In the English style, the shooter looks relaxed, almost nonchalant. The best English shooters make shotgunning appear effortless.

We can contrast this to an extreme I call the “mid-Missouri skeet stance.” This is a style first encountered on a skeet range in Missouri (hence the name), and it was being generally taught to anyone who came to the range looking for instruction. This stance is exaggerated, feet wide apart, crouching like a sumo wrestler, the gun mounted, safety off, and neck, arms, and shoulders rigid. There is no flexibility for reacting to the unexpected, and the swing is as relentless as the pivoting of a naval gun. Workable for American skeet, perhaps, but useless for much else.

The English stance, on the other hand, is loose and relaxed, feet not too close together, but also not too far apart. The shooter is on the balls of their feet, leaning slightly forward with the weight on the leading foot. The head is slightly forward with the “predator’s look” in the eyes, the result of focus and concentration. The body can pivot in any direction — left, right, up, down — responding instantly to whatever target is presented, from a low crossing shot to a screaming incomer. Because the gun is not at the shoulder, the eye has an unobstructed view of whatever comes along, from whatever angle.

At the Holland & Holland shooting ground, teaching teenagers proper shooting technique.

At the Holland & Holland shooting grounds near London, instructor Roland Wild works with a teenage shooter on gun mounting.

The human body has a natural athletic or defensive posture that is used in a wide range of activities: boxing, batting and throwing in baseball, shooting a pistol using the Weaver combat stance, or shooting a rifle offhand. All these employ essentially the same position, and for the same reason: It is the most flexible stance for both offense and defense, allowing you to respond to the unexpected, including an attack. A flushing pheasant, a 95-mile per hour fastball, an incoming clay, or an opponent’s left jab all amount to much the same thing, in athletic terms. At the same time, this is a very relaxed position, with no tense muscles to start shaking. Combined with this relaxed physical stance, the shooter must have laser-like concentration.

The real purpose of this chapter is not to instruct in shooting, but to show how to find a good instructor. It is important, however, for the prospective student to have some idea of what to look for. An initial few sessions with a bad instructor can be very destructive, not only to your shooting style, but to your outlook and desire to continue shooting.

In 1994, I attended a five-day course of instruction in Vale, Colorado, put on by Holland & Holland. There were 10 instructors and 40 participants. Divided into groups of four, we rotated through one instructor after another. We had two days of shooting, then a day off, followed by the final two days of shooting. It was June, and it was hot, dry, and draining. The day off in between was most welcome, because you can only take so much intensive instruction before you need a break.

Sometimes closing one eye helps eliminate a “master eye” problem. A good instructor can recognize this and help correct it.

Some of the instructors were from Holland’s own shooting grounds outside London, others were freelance English instructors, and about half were Americans. This allowed the extreme range of instructing theories and styles. What I learned most from that course was not so much any shooting style, but rather the fact that I respond well to some instructors but not to others. From some I learned one specific thing well. Others left me confused, and a few even seemed to erase whatever skill I had. Perhaps the most valuable lesson was that the student’s personal relationship with an instructor has nothing to do with whether you will learn well from him or her. You can actively dislike your instructor yet gain a great deal, while another person you would cheerfully spend days with seems unable to impart any meaningful knowledge. Strange, but true.

For example, Dan Carlisle, an American Olympian who has won medals in both trap and skeet and who has a shooting ground in South Carolina, is one of the most intense individuals I have ever met. A very nice guy, but 15 minutes with Dan will turn you into a quivering wreck. What I did learn from him, however, was the value of concentration. And I mean concentration! A 45-minute session with Carlisle is draining, to say the least, but, when you finish, you are seeing the printing on the raised edge of the clay as it flies. Another instructor, Keith Lupton, an Englishman transplanted to America, was able to get me shooting to the point where he could tell me which edge of the clay he wanted me to dust, and I could usually do it.

Then there were others, who shall remain nameless only because I no longer remember their names. I gained nothing and was lucky to be able to hit anything after a session with them. This was where I learned the value of finding the right instructor and then working with that person on a regular basis. Good shooting is not learned in a weekend, nor even over a year or two. It is a lifelong pursuit, and trying to do it with a poor instructor is a frustrating waste of time and money.

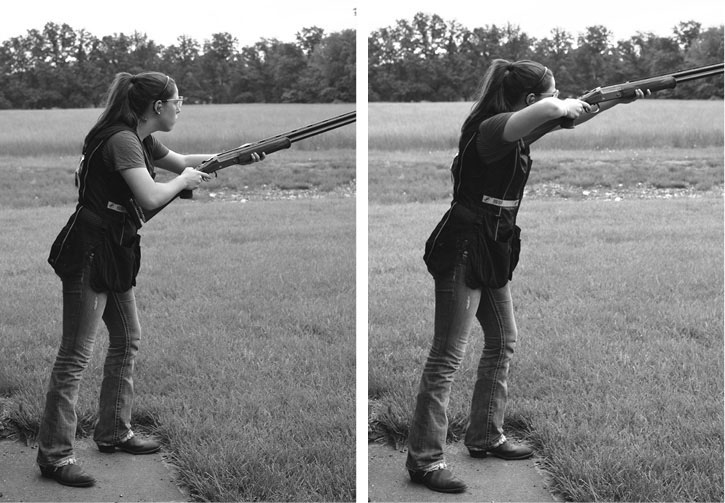

In her early 20s, Alison Caselman is a very accomplished competitive shot. She learned proper technique from the beginning, and is now with the University of Missouri shooting team.

A good instructor asks what you want to accomplish. They do not immediately try to change your entire shooting style to suit their own ideas, at least not without justifying it beyond a simple “I prefer it this way.” Most important, a good instructor does not insist that they have found “The Way” and that every other shooting instructor in the world is wrong.

Everyone wants a simple answer, the key to good shooting, the one little thing they are doing wrong that, if corrected, will turn them into Lord Ripon on pheasants or a gold medal trap shooter. Some instructors offer such a magic solution. One instructor who advertises widely insists that, for a right-handed shooter, the proper stance is right foot forward. Every other instructor in the history of the world insists on leading with the left foot, in the natural fighting stance described above. So who’s correct?

Then there are the instructors who want you to stand square on to the target, rather than at 45 degrees, and insist you need to chop an inch off your length of pull to accommodate this odd stance. Fine to try, if you have an adjustable stock, but not so great if it means shortening a piece of expensive walnut on an $80,000 Holland & Holland. Now that could be an expensive lesson!

Prospective students should look askance at such claims on the part of any instructor. Self-appointed messiahs may get decent results occasionally, but anyone who says they will have a beginner consistently breaking 25 straight after one morning’s instruction is selling snake oil.

Finally, be aware of the instructors who specialize in skeet, trap, or sporting clays and who will usually insist on a rigid stance with the student beginning their shooting with the gun at the shoulder, the eye aligned down the rib, and the safety off. This is all fine if you intend to shoot American trap or skeet and nothing else. The problem is that anyone who learns to shoot this way will have great difficulty later adapting to any other method. Just as a driver who learns to drive with an automatic transmission never seems able to adapt to a stick shift and a clutch, so learning to shoot “gun up, safety off” becomes so ingrained, you can never comfortably shoot “gun down, safety on.” For a game shooter or anyone who wants to shoot game at some later date, this can be fatal. You do not walk in on a point with the gun at your shoulder and the safety off, nor do you stand in a shooting butt like that, waiting for driven grouse. For this reason, one of the most important motions in shooting is the smooth, efficient gun mount, while watching the target in the air. Learning to shoot gun-down teaches this mount and becomes the cornerstone of all your shooting.

• • •

The first recorded formal shooting school was set up near London, England, in the 1860s. By the 1880s, all the major London gun makers had shooting grounds of their own, where they tested and finished their guns and rifles and allowed clients to practice. When gun fitting became common, clients would go to the grounds to be fitted, using a try-gun (a fully functional shotgun with a stock that can be adjusted in every direction).

Gradually, courses of fire were set up, employing various types of thrown artificial targets, as well as the use of live birds. The final step was the formal course of instruction, with qualified instructors teaching newcomers how to use a shotgun, or working with experienced shooters to perfect their technique or solve problems. Just as even the best professional golfers realize they can always improve and take regular lessons, so the best shots continue to work with qualified instructors to improve their style.

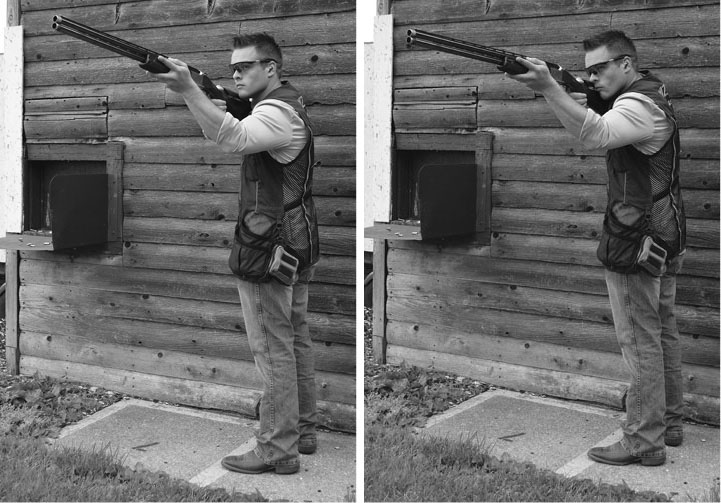

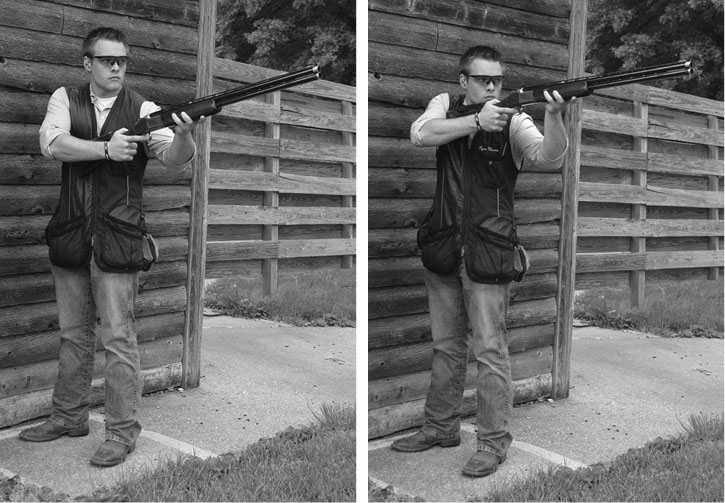

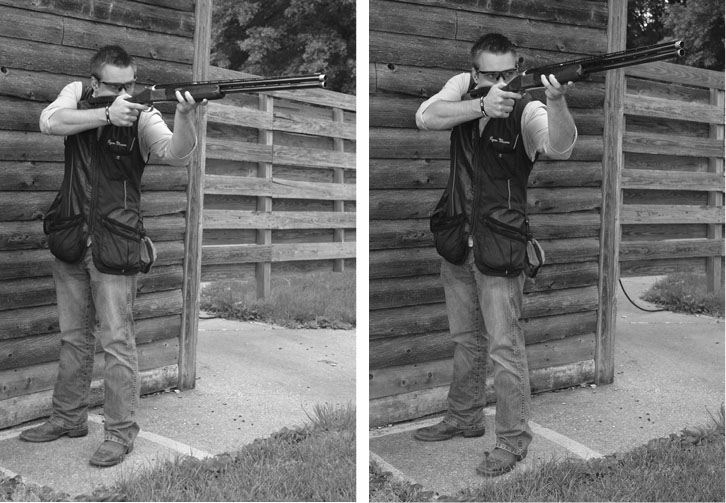

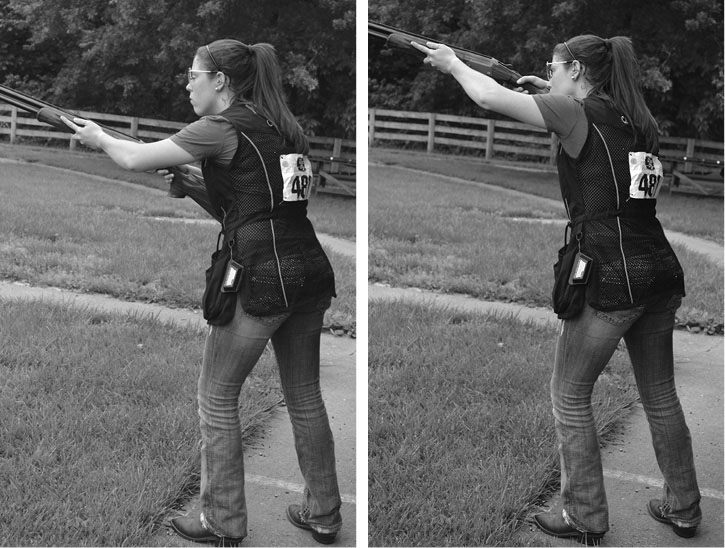

Ryan Mason demonstrating proper stance and gun mounting. Ryan is an international skeet shooter, and the rules demand the gun be down until the bird is called for. Proper mounting is essential. Ryan likes to have his feet a little closer to 90 degrees to the target, rather than the usual 45 degrees. Weight is on the leading foot, and the gun comes up to the face. Notice that there’s not a lot of change in his body from unmounted gun to mounted.

The most famous American exhibition shooter of all time was Annie Oakley, the petite trick shot who performed with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Oakley dazzled audiences across Europe with her rifle shooting skills; when the show reached London, all of England was soon at her feet. While Oakley was deadly with a rifle, however, she was not so good with a shotgun. During her stay in London, she paid a visit to Charles Lancaster & Co., on New Bond Street, where she met its proprietor, H.A.A. Thorn. Thorn was one of the leading figures in the London gun trade, a gun maker, inventor, shooting instructor, and author who liked to be called “Mr. Lancaster.” As a result, Thorn’s name does not have the renown it deserves.

Thorn undertook to fit Miss Oakley for a pair of shotguns, then gave her a series of lessons at his shooting ground. A natural shot, she was soon as devastating with a shotgun as with a rifle. She defeated her future husband in a box-pigeon match, and even gave lessons herself to English women who wanted to shoot, not just watch. For England in that era, this was a remarkable thing to do and the beginning of active participation by women in English shooting that endures to this day.

H.A.A. Thorn wrote a book called The Art of Shooting, which appeared in 1889, has gone through more than a dozen editions, and has been in print ever since. It is one of shooting’s all-time best sellers, and deservedly so. Charles Lancaster & Co. built several guns for Annie Oakley and was her London gun maker from that point on. Oakley herself became an American heroine, and inspired movies, books, and a Broadway musical. Throughout her life, she was a strong advocate of women learning to shoot, for both sport and self-defense, and gave shooting instruction to an estimated 15,000 women during her lifetime.

The example of Annie Oakley illustrates a couple important points. One, most instructors agree that women are better shooting students than men. They accept both instruction and criticism better, because they have nothing to prove. The second is that women can also be better instructors than men, and for both male and female students. Shooting truly is a unisex sport; on any given day, a good female shooter can whip a good male shooter, and vice versa. The playing field is exactly level in that respect — and you could also argue that women have an advantage in that they are not burdened with the male ego, when it comes to shooting prowess.

• • •

In days gone by, the accepted way for a young person to learn to shoot was to be introduced to guns at an early age, receive some instruction from a relative, be watched like a hawk and, if he made the grade, be gradually accepted into the company of hunters and shooters that made up his family. Robert Ruark’s The Old Man and the Boy portrays this culture in an admittedly idealized way. Alas, that way of life is gone forever. Many people now grow up with no one in their family to impart the knowledge and skills of shooting. Others live in cities and have no local farmland where they can learn to shoot and practice in an informal way. Still others come to shooting later in life and attempt to acquire skills that, while easy for a young person, are much more difficult for an adult.

Today, on a shooting range, you will encounter self-taught adults who are completely unaware of the fundamentals of shooting etiquette, and some who are certifiably dangerous with a gun. What’s worse is finding yourself with such a person in a group, hunting pheasants or doves or shooting a round of skeet, activities where safety is a paramount concern, and there is no easy escape.

While we talk about learning to shoot well as a separate activity, we should really emphasize that what is important is learning to shoot safely. Indeed, the aspects of skill and safety should never be considered in isolation. Safe shotgun handling should go hand in hand with skillful shotgun handling, and the former should never, ever, under any circumstances, be sacrificed to the latter.

Professional shotgun instructors incorporate safe gun handling and proper etiquette into every aspect of their curriculum. This is not necessarily true of fathers, uncles, brothers, and boyfriends, even if they are safe gun handlers themselves. Some simply take it for granted or think the issue is self-evident. Self-taught shooters, who learned their technique from a book, often skip the chapter on safety and etiquette (if there is one).

There are a few simple rules of shotgun courtesy:

One point to make regarding “where you are missing.” It is possible to see a charge of shot in the air, and many experienced instructors can do so. It is best described as a “disturbance,” a brief shimmer in the air, and can be seen better in some light conditions than others. Surprisingly, it is most often seen under “cloudy bright” conditions than it is in open sunlight.

At various times, shotshell manufacturers have offered “tracer” rounds that, theoretically, allow the shooter to see where their shot went. This has never worked very well, because, if you are looking to see where your shot goes, you are sure to miss. Instructors never found it particularly helpful either, and the fact that it set fire to dry grass was a definite drawback in hot climates. Being able to see conventional shot in the air, however, is almost a status symbol for would-be instructors, and many people claim to see it when, in fact, they don’t. As for people who start loudly telling you your shot was behind or high or low, they are usually basing the assessment on the flight of the wad. Since a wad opens like a flower and flies like a demented frisbee, where it flew bears no relation to where your shot charge went. Such information, well meaning or not, is not helpful to the shooter, and onlookers would do better to just keep quiet, unless they are asked.

These are accepted courtesies, not hard rules, but, as you can see, most are merely adaptations of the Golden Rule: Do unto others, as you would have them do unto you.

• • •

There are instructors who also need a few lessons in good manners. Some come from military backgrounds and think every flat surface is a parade ground. Others believe the best way to spur effort is to humiliate someone, in a loud voice. Still others, finding themselves in a position of authority for the first time in their lives, immediately forget that they do not know everything there is to know.

In my observation, these afflictions never seem to apply to female instructors, most of whom believe you catch more flies with honey than vinegar and, so, take a very soft-spoken approach. One of the best all-around shooting instructors I have ever met is a diminutive lady named Il Ling New, who works as both a freelance and a staff instructor at Gunsite, in Arizona. Miss New specializes in tactical work, but also teaches hunting skills with rifles large and small, and tactical shotgun skills. Working with her on many occasions, I have never once heard her raise her voice. Then again, being as good with a gun as she is, she doesn’t need to.

Loud and abusive behavior rarely gets good long-term results, but even a short-term acquaintance with such an instructor can be damaging. Before signing on for a series of lessons, it is beneficial to watch an instructor at work with someone else, or at least talk with a former student about his or her methods. Your choice of a shooting instructor could be the single most important decision you make on the road to becoming good with a shotgun.

This leads to one last point. Some instructors have an affinity for a particular type of shotgun. If they happen to prefer over/unders and you show up with a side-by-side, you do not want them to immediately start denigrating your choice of gun or blaming it for every miss. Assuming the dimensions are acceptable, it is possible to shoot very well with any decent gun, whether it is a brand-new semi-auto, your father’s 50-year-old pump gun, or a century-old side-by-side.

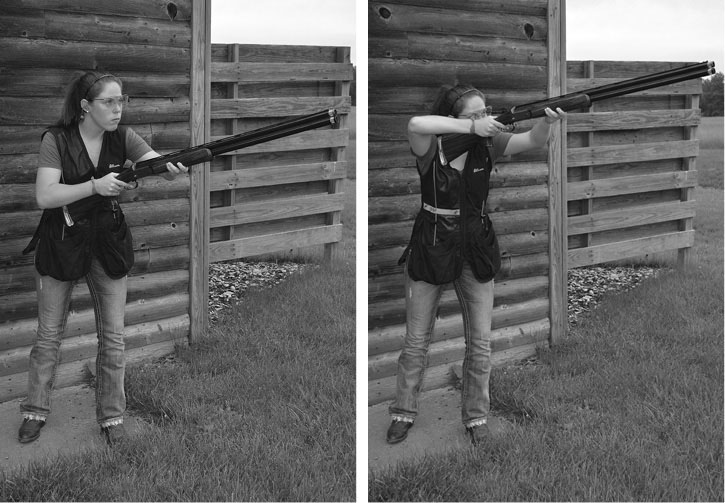

Alison Caselman demonstrating stance and gun mounting. Alison keeps her feet closer to 45 degrees and holds her right elbow higher than Ryan does. Her stance and technique are excellent, with her weight well forward, her body relaxed, and, so, she is able to respond to any target. Alison has the most piercing “predator’s gaze” when she mounts her gun, a sure sign of concentration, an essential element in shotgun shooting.

One time, I spent a couple days with a prominent instructor who was a good guy overall, a very fine shot, and a dedicated student of the shotgun. He and his wife both shot heavy sporting over/unders. I was carrying a Grulla Armas side-by-side that I’d had made in Spain; it is a 12-bore built on a 20-gauge frame and weighs six pounds, five ounces. In it, I shoot very light loads. For two days, every time I missed a clay, I heard that it was the fault of that “girlie gun” I was shooting, followed by a suggestion that he could get me a deal on a “real” gun like a Browning.

A good instructor will work with the gun you bring, unless it is so completely unsuitable by weight, dimensions, or choke that the student is at a real disadvantage. Some shooting grounds have shotguns available for loan. But know that, while you might appear with a perfectly nice over/under 28-gauge, there are some instructors who will immediately insist you switch to a 12- or 20-gauge semi-auto. To me, any semi-auto is a poor gun with which to learn, because it is mechanically more complicated, inherently less safe (especially in the hands of someone not very familiar with guns), and more prone to difficulties such as jams or failures to eject. Generally, the safety is not in the most convenient spot for shooting safety-on. The reduced recoil of a semi-auto, which is really its only virtue for a beginner, does not begin to compensate for the drawbacks.

Because a shotgun does not have conventional sights like a rifle, whether it delivers its pattern where you want it to depends largely on how well the gun fits you.

As mentioned before, gun fit is more important than some would have us believe, but not as important as others insist. A good shot can do quite well with a poorly fitting gun, and a bad shot will miss even if the gun fits perfectly. In the former case, however, the good shot knows where the gun falls short and compensates for it. This requires awareness and conscious effort. At the end of a long day of shooting, whether at trap, driven birds, or flighting doves, when every muscle is tired and the mind is weary, having a properly fitted gun that allows good shooting without extraneous effort pays dividends. Proper fit is at its most valuable in game shooting, particularly in reacting to the totally unexpected.

The concept of gun fit originated in the 1860s, as shotguns became more refined. At first, a buyer would try several different guns off the shelf, pick the one that seemed most comfortable, measure the dimensions, and proceed accordingly. Then came the idea of shooting several different guns at targets. Eventually, William Jones of Birmingham patented the first adjustable “try gun,” a working firearm with a stock that was adjustable for length, drop, and cast. With a try gun, the client accompanies the gun fitter to a shooting range and proceeds to fire a hundred shots or more, with the fitter adjusting each aspect of the stock until he arrives at the perfect fit for the client’s needs.

Like shooting, gun fitting is a skill. Anyone can claim to be a gun fitter — and many do — but really competent gun fitters are few and far between. To be properly measured, you need a fitter with several different try guns; you also need several hours on a range, a few hundred rounds of ammunition, a proper patterning plate, a variety of moving and stationary targets, and three or four hundred dollars in your pocket. There is no way you can obtain anything but a rudimentary idea of your measurements with a tape measure in a gun shop, or by filling out a chart of body measurements, or by standing at some gun maker’s booth at a show and stretching out your arms.

There are several aspects to gun fit above and beyond your body size. First is whether you are right- or left-handed, as well as whether your right or left eye is your “master” eye. Many books and articles have attempted to show an easy way of determining eye domination. A simple way is to put your hands together to form a triangular opening at arm’s length, center an object in the opening with both eyes open, then slowly pull your hands toward you. You hands will naturally come back to your master eye.

This is helpful, but not absolute. Your master eye can shift permanently as you age, and eye dominance can even change back and forth in the course of a day, because of fatigue. Sometimes, it will shift temporarily because of an irritation. Anyone with shifting eye dominance can solve the problem by simply shutting one eye. This eliminates depth perception, however, and narrows your field of vision, neither of which help your shooting — but, then, neither of these effects is as outright damaging to accurate shooting as a complete change of eye dominance. A good gun fitter will pay close attention to eye dominance, and a competent instructor can even identify eye dominance issues from watching a series of shots.

• • •

Standard shotgun dimensions today are roughly as follows: The length of pull is 14 inches, drop at comb 11⁄2 inches, drop at heel 21⁄2 inches, with no cast (bend to left or right) either way. Almost anyone can adapt to these dimensions and shoot pretty well. Some very good shots go through their entire lives shooting factory guns with standard dimensions and, especially if they stick to just one gun, can reach a point where it would be hard to improve very much.

Not everyone is average, however, and, for the very short, very tall, those with extra long arms, and those with some sort of physical abnormality, stock alterations can be made — most of them fairly easily and cheaply. It is not necessary to spend $5,000 to have a gun restocked in order to get dimensions close to what you need. The key, however, is first determining what exactly you do need. Money spent on a proper gun fitting is never wasted, especially if you intend to buy a custom-built shotgun. Too, if you can find a shooting club with a good instructor who knows shotguns and has a selection of different guns to try — different gauges, actions, and dimensions — then you can experiment a little before making a decision about which gun to buy or whether to change from what you already have.

Although it was mentioned before, it bears saying again: No one can get measured in any meaningful way unless they already know how to shoot reasonably well. Sometimes an instructor will take a new student, even a complete beginner, and start padding the stock with foam rubber and tape to build it into “proper” dimensions, this before the student fires more than a dozen shots. Sometimes this is justified — if the gun in question is far off normal dimensions, for example — but often, it is just an exercise in the instructor showing how much he knows. Personally, I would think twice before allowing a total stranger to start taping up the nice walnut stock on my father’s old gun, and for sure he’s not going to go at it with a saw or a rasp.