SAMPLE ASSISTED OUTPATIENT TREATMENT (AOT) FORM

While activists push for care and cures, researchers advance the science, and politicians and thought leaders promote societal and policy change, today’s patients, health care providers, concerned citizens, and family members need immediate, practical answers. If a doctor diagnoses you with strep throat, the remedy—an antibiotic—is obvious, inexpensive, and easy to procure. When it comes to mental illness, solutions are not so clear-cut. The recommendations that follow are a compilation of the best I’ve heard from experts, mental health care consumers, and families. For more suggestions, please go to the websites and books of experts like Lloyd Sederer, MD, Xavier Amadour, PhD, and DJ Jaffe.

1. Connect with NAMI. For solidarity, education, advice, and to find knowledgeable service providers, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization. The HelpLine (800-950-6264), operated by NAMI staff and volunteers, and their website provide information and resources, including the following:

Symptoms of mental health conditions

Treatment options

Local support groups and services

Educational programs

Helping family members get treatment

Employment programs

Legal issues, including listings of attorneys with expertise and experience representing people living with mental health conditions

In addition to information and resources, NAMI provides opportunities for connecting with others coping with similar challenges. This solidarity can help us find the strength to shake off the stigma of mental illness and recognize it as a health condition that deserves the same respect, attention, and support, societal and otherwise, as any other. Support and advocacy groups for families can offer a stable base that fuels the resilience necessary to fight for the policy change that is so urgently needed in our time.

The burden on parents whose young or adult children develop SED or SMI is tremendous. The attempts they make to get them to go to school, get a job, see a therapist, or take medicine can wind up in fights that lead to violence or even suicide. If a parent decides not to push, their child may draw inward or self-medicate with street drugs. People blame these families for “enabling”—for having no backbone and setting no limits—but it is incumbent on the rest of us to quit the blame game and instead make sure that families have the resources and wherewithal to find proper treatment. NAMI is a great first step to helping families deal with self-doubt, blame, and second-guessing, and to find viable solutions.

Other excellent resources are available at Strong365 (https://strong365.org/), an empowering online community and resource hub for young people and their families seeking information and support for early stage psychosis.

2. Develop a crisis plan. Coping with SMI is like living in a city that’s under constant threat of terrorist attack. You need to plan for the worst. The first step is to research what resources are available in your community. Call the nearest psychiatric emergency room to see if they have a mobile crisis unit. These teams usually include mental health professionals who can perform a home visit for the purpose of evaluation, provide referrals to outpatient treatment, and, if necessary, hospitalize someone in immediate danger to self or others. The social worker, nurse, or doctor will be able to tell you what the mobile crisis team can provide and how to contact them. Now, before disaster hits, is the perfect time to write this number down on your emergency list.

3. Create a support team. Monte and his family provide an excellent model of how to build a support team around a loved one with SMI. Patrisse has learned how to manage what she can but also how to involve others, helping them to step into various roles: the person to take Monte to the hospital, the one to bring him food, and the friendly faces to rescue him when his psychosis escalates. Like me, Patrisse has found that sometimes as a sibling, you are too close to be helpful, too angry to engage, or simply too busy. It’s important to marshal outside resources for everyone’s well-being.

In 1980, the average hospital stay for someone with schizophrenia was forty-two days.1 Today it is seven days or less, and often just three to four days.2 Since aftercare is usually lacking, loved ones wind up filling in the gaps. Family members would do well to avail themselves of all the support they can get from friends and relatives. We know that what works best for people with SMI are unified teams of professionals where social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and vocational and housing specialists all work together under a team leader toward a unified cause of support. When outside resources like that aren’t available, loved ones banding together can keep the burden from falling on any one or two individuals.

4. Prioritize empathy and collaboration. People with SMI can quickly become marginalized and alienated from their own treatment. Collaboration is critical not only to preserving relationships but also to maintaining the human connection that is an essential element of healing. Striving for allegiance can go a long way toward fostering a team approach.

I don’t want to minimize the difficulty of collaborating with someone with a brain disorder. Many people wind up living in an altered form of reality, and it can be difficult to find common ground. One thing I can say with certainty is that issuing “my way or the highway” ultimatums often backfires. Addiction specialists often encourage families to take a “tough love” approach that can include withdrawing financial support if the loved one won’t accept medical help. That message may be able to break through to people who are addicted to substances, but for someone who is experiencing a psychotic episode—who doesn’t ever “sober up” but instead remains “intoxicated” with their delusions, hallucinations, and irritable moods—this advice does not apply. My sister would sooner perish than accept medical intervention. That’s why most experts put at the top of their advice list to never deny health insurance, medical care, shelter, or food. What does help is offering up as much love as you can.

Norm Ornstein learned this painful lesson with Matthew. “For years I would try to reason and argue with Matthew based on my powers of logic,” he tells me, “but it was very clear that there was nothing that I was going to say that would shake him from his own beliefs.” Following his failed attempts to reason his son into treatment, it became clear that he needed to find a different approach. Dr. Xavier Amador’s seminal book I Am Not Sick: I Don’t Need Help offers a new model for communication: the Listen-Empathize-Agree-Partner (LEAP) method, which emphasizes the human connection above all else.

The core tools of LEAP, which is specifically geared toward gently nudging someone with SMI to accept treatment, are “Listening (using ‘reflective’ listening), Empathizing (strategically—especially about those feelings you’ve ignored during your previous arguments about your loved one being sick and needing treatment), Agreeing (on those things you can agree on and agreeing to disagree about the others), and ultimately Partnering (forming a partnership to achieve the goals you share).”3 This approach hinges on finding connection points, which fosters mutual respect.

What if a loved one refuses treatment because they are convinced they aren’t sick? The phenomenon, called anosognosia, or poor insight, is a symptom of the disordered thinking caused by the disease itself. It’s important to keep in mind that this lack of recognition is not a choice, but a part of the sickness.

You don’t have to agree with your loved one’s reality, Amador insists, “but you do need to listen and genuinely respect it.” Reflective listening, whereby you take in what the other person is saying with an open mind, without being reactive, and then restate what you’ve heard in order to “reflect” it back, is key. It sets the stage for the next steps of empathizing, agreeing, and partnering toward your shared goals. The first objective is to repair any damage to the relationship from your previous attempts at rational convincing. The second is to help the ill individual find their own motivations for accepting treatment by presenting medication or therapy as a means for them to fulfill their own wishes.4 This protocol not only makes common sense, it’s rooted in long-standing clinical practices that have been used successfully for generations. It remains one of our best defenses against engaging in a one-on-one power play in which all parties lose.

5. Get psychiatric help. If at all possible, it’s best to think through your options before a crisis arises. (See number 2.) But when trouble starts, trust your instincts and get help sooner rather than later. The resources available will depend on your location, but Dr. Amador recommends the following:

If an emergency room visit is needed, accompany your loved one. When dealing with hospitals and/or mental health providers who refuse to speak to you as a friend or family member, consider taking Norm’s advice not to let them use an overly wide interpretation of HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act). In his experience, “almost everybody tries to hide behind HIPAA to avoid the hassles or the potential lawsuits.” For many health care providers, particularly overburdened staff in the hospital, it often is more convenient to invoke privacy rules than to put effort into parsing out what information they might be able to share with families (which doctors may fear could risk backlash in the form of a lawsuit for privacy infraction or even evoking the patient’s anger). Norm urges family members to request a copy of the institution’s medical information privacy policy, read it, and point out any discrepancies between what is written and their blanket refusal to provide any information at all.

Ron Honberg, a lawyer with NAMI, explains that medical information can be shared with loved ones when the “health provider determines, based on professional judgment, that doing so is in the best interests of his/her patient” or “believes, based on professional judgment, that patient does not have capacity to agree or object, and sharing information is in his/her best interests.”

The Treatment Advocacy Center also points out that “providers are not precluded under HIPAA from accepting information from families or others who are knowledgeable about the individual and his or her treatment needs. [In other words, there is no law against the doctor hearing a family member’s concerns, history, or experiences with the ill individual.] A good medical provider will want to know all the relevant information available. If your loved one’s provider refuses to listen to your information, contact a supervisor such as the hospital administrator, insist that you be heard, and/or submit written information.”

If you need emergency intervention at home, call the local crisis intervention team (CIT). To find out if one is in your community, call any psychiatric emergency room or your local police department. Members of these teams, which often include some combination of a doctor, nurse, social worker, and case manager, are trained to deal with people in mental health crises and therefore better equipped to interpret behavior as a symptom of SMI rather than of criminal intent.

As Dr. Amador explains, if a mobile crisis team judges “that hospitalization is warranted, they will try to convince your loved one to accompany them to the hospital. If he refuses, they can initiate the commitment process immediately.”5

Assertive community treatment programs are another resource. Lloyd Sederer, MD, chief medical officer of the New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH), the nation’s largest state mental health system, calls ACT teams “the most intensive and most expensive form of ambulatory care.” They travel to wherever a person with SMI is, usually several times a week for a year or two, until their mental health is stabilized. Mobile teams can also provide an evaluation on the spot.

If you have to call the police because no mobile crisis team is available, explain to the dispatcher that your loved one has mental illness so that responding officers will be clear about the situation before they arrive. If possible, meet officers at the door, explaining where the person in crisis is, what behaviors they are exhibiting, and the cause for your concern. It’s crucial to tell officers whether the person has access to anything that might be construed as a weapon. And here’s another tip from Dr. Amador: “If your loved one has thrown or broken anything, don’t try to clean up before the police come. Whatever damage your loved one has caused may be the only overt sign of illness the officers can see.” Try to keep the interactions as cool and levelheaded as possible.

As a clinical psychiatrist, I understand how hard it is to find a doctor, clinic, or hospital that you trust. Picking a provider is no easy task. Here are a few parameters to consider:

Treatment must be affordable: Throwing money at the problems of SMI will not quickly resolve them. Mental illness is a war, not a battle. Although an expensive hospitalization may offer a diagnosis and be money well spent, it’s important to conserve funds for long-term outpatient and inpatient care. Parity laws have enabled people with psychiatric conditions to receive benefits for outpatient and inpatient care comparable to folks with other medical issues. Even if you are dependent on state or federal health insurance plans, these are now legally required to offer psychiatric care in ways similar to medical care. We are far from realizing that goal of mental health parity for all Americans, but don’t be deterred if your health care plan does not seem adequate. You can appeal any denials of care. For those who can afford it, policies that offer out-of-network coverage offer the most options. But whatever plan or coverage you have, think ahead to make sure that you can afford treatment for the long haul.

Find a provider with whom you have good chemistry: Because of the lack of uniform treatment protocols, choosing the right psychiatrist, medical doctor, or nurse practitioner for medications and a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or nurse for talk therapy may take some due diligence. Aside from making sure that your provider is affordable and convenient, you want someone who is well regarded by their peers and patients (as per word of mouth or in online reviews), is honest and ethical, and employs evidence-based best practices. You may want someone who works within a medical school or university setting and has colleagues looking over their shoulder. But most of all, as in any relationship, you want someone you can trust. You want good chemistry: an interpersonal fit, someone you can get along with, someone you can tell your truth to, to whom you can say nearly anything, and someone whose opinions you can respect.

Pick the treatment with the fewest side effects, but be open to all evidence-based options: With all mental illnesses, from mild to the most severe, psychotherapy, or talk therapy, can change your brain for the better. Individual therapy, family therapy, group therapy, and self-help groups can make a world of difference. And unlike meds, no side effects!

Medications are often required. Always seek the lowest dose and the least invasive treatment first as prescribed by a reputable, licensed clinician. Then, if lower medication doses are not sufficient or your talk therapy needs to be more intense and frequent, be ready to increase the level of care.

Many of us make up our minds about what is acceptable and unacceptable without seeking out the latest scientific data. For instance, clozapine, an effective antipsychotic, is underused because of fears about its side effects. These concerns aren’t unfounded, but such risks can be monitored and dosages moderated to find a balance for many patients who would otherwise suffer without the drug.

Another maligned treatment is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) because of its 1950s reputation. But, as used today, it’s one of the safer and more effective treatments for entrenched depression that hasn’t responded to other modalities. ECT helps up to 90 percent of patients with mood disorders.6 Part of its bad reputation has to do with the nature of the treatment itself, and part with its sordid history. Until the 1960s, ECT was performed with electrodes placed on both sides of the head (making it more likely to cause memory problems) and without anesthesia (causing broken bones when patients flailed their bodies around during the therapeutic grand mal seizures that the treatment induced). Now, ECT is always done with anesthesia and is most often performed unilaterally, on one side of the head, on the nondominant hemisphere. No one would call the treatment pleasant, but it’s nothing like the depiction in the 1975 film One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which showed fictionalized versions of procedures conducted in the 1950s.

Self-care: Too often we rely on the hour or so a week we may see a doctor or therapist, without thinking about what we can do in between appointments. Proper medical care is an essential piece of the puzzle, but it’s no substitute for healthy living. Good nutrition, exercise, meditation, time with friends, proper sleep habits, laughter, cultivating a religious or spiritual life, and meaningful work and play can make a world of difference. Conversely, excessive alcohol use, taking recreational and unprescribed drugs, gambling, and other risky behaviors, as well as engaging in dysfunctional relationships—all of these may mess with your mind. Whether you are a patient or family member, self-care is crucial for your well-being.

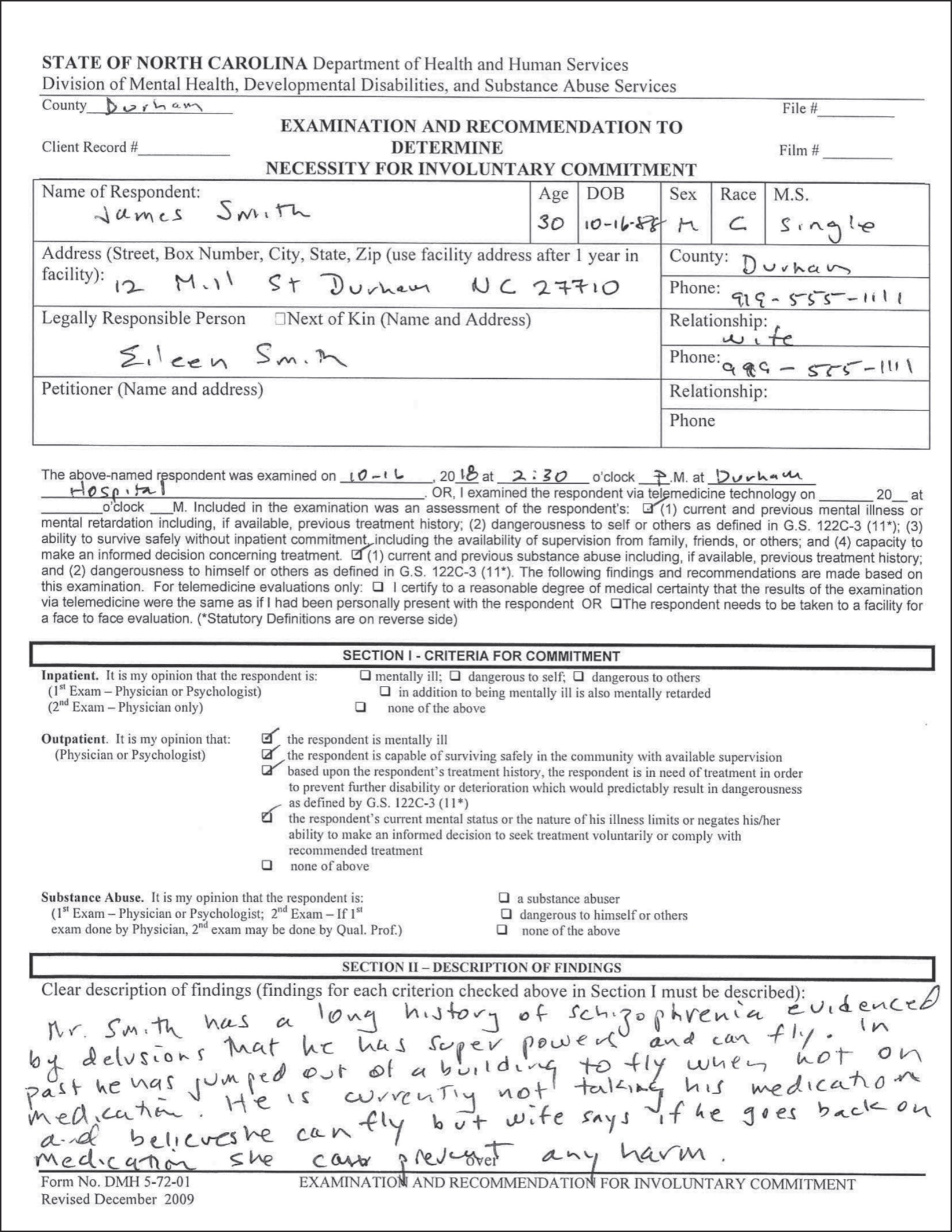

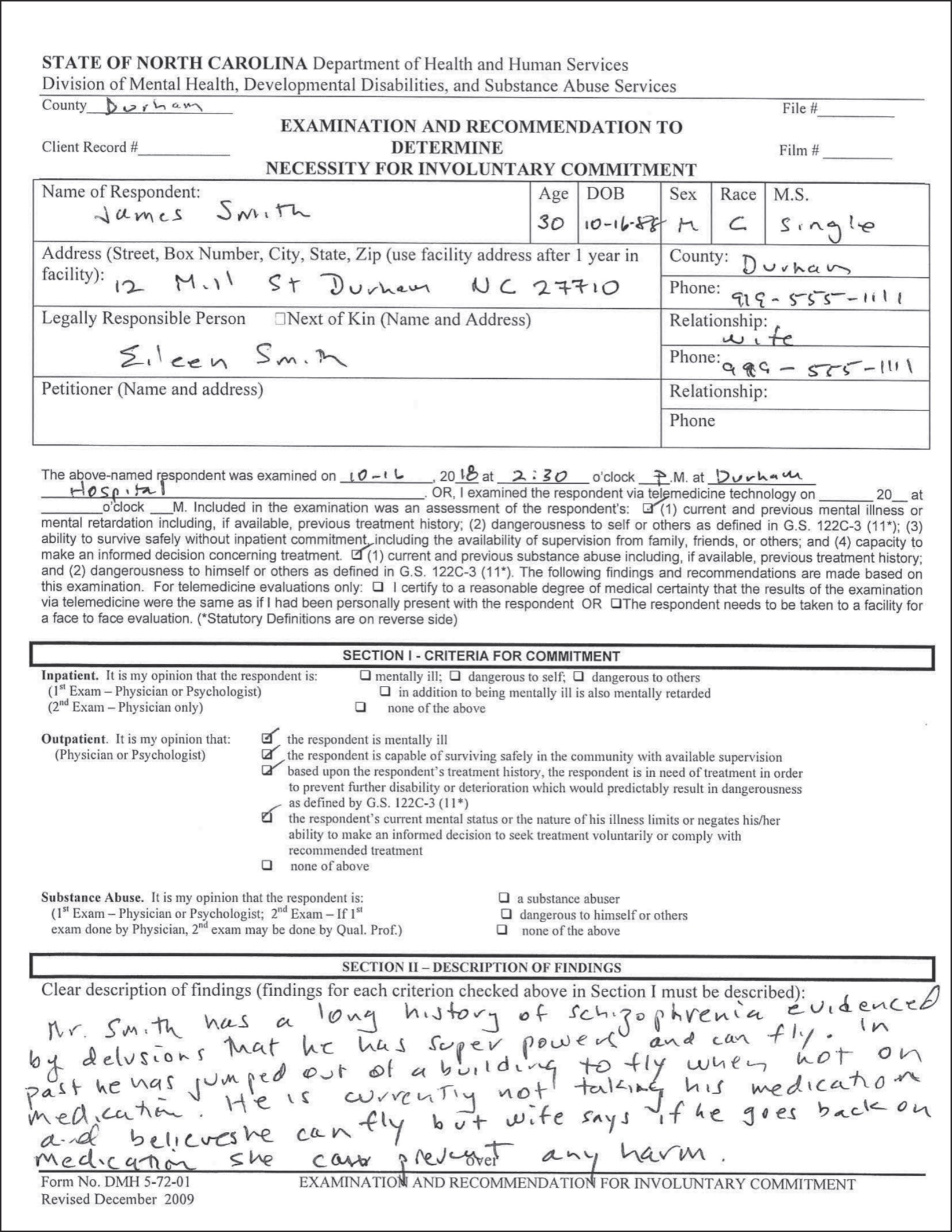

We have discussed mental health courts (MHC), assisted outpatient treatment (AOT), and psychiatric advance directives (PAD)—all legal instruments to get the needed treatment. Each state and jurisdiction has its own forms, and these need to be filed through your local magistrate with the help of legal counsel.

Using the NAMI HelpLine and the listings on the Treatment Advocacy Center website (http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org), learn what legal resources are available in your state to pursue MHC, AOT, PAD, or health care powers of attorney. In many states, a PAD includes instructions about what a patient will consent to or refuse, while a power of attorney grants authority to a trusted loved one to make care decisions for someone who is incapable of doing so for themselves.

If you’re the patient, a PAD specifies exactly what you want to have happen if you become psychotic or too impaired to make decisions. For family members, these directives can be particularly useful for fostering a sense of collaboration. Not only does one provide a crisis plan, it ensures the autonomy of the patient because they have put in writing how they want to be treated in the case of an emergency. This mitigates the alienation that many people with SMI experience both as a result of their own disordered thinking and by how they’re treated by medical staff during a break with reality.

Although the experts I consulted confirmed the difficulty of enforcing such directives, they still recommended them as a valuable step in a constructive and collaborative conversation about care when one is in the throes of a psychotic episode. State-by-state guidelines and downloadable forms are available on the website of the National Resource Center on Psychiatric Advance Directives (https://www.nrc-pad.org).

SAMPLE ASSISTED OUTPATIENT TREATMENT (AOT) FORM

SAMPLE PSYCHIATRIC ADVANCED DIRECTIVE (PAD) FORM

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA

ADVANCE INSTRUCTION FOR MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT

COUNTY OF Durham

(NOTICE TO PERSON MAKING AN INSTRUCTION FOR MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT)

This is an important legal document. It creates an instruction for mental health treatment. You should consider filing it with the Advanced Health Care Directive Registry maintained by the North Carolina Secretary of State: http://www.secretary.state.nc.us/ahcdr/thepage.aspx [inactive]

Before signing this document you should know these important facts:

This document allows you to make decisions in advance about certain types of mental health treatment. The instructions you include in this declaration will be followed if a physician or eligible psychologist determines that you are incapable of making and communicating treatment decisions. Otherwise, you will be considered capable to give or withhold consent for the treatments. Your instructions may be overridden if you are being held in accordance with civil commitment law. Under the Health Care Power of Attorney you may also appoint a person as your health care agent to make treatment decisions for you if you become incapable. You have the right to revoke this document at any time you have not been determined to be incapable. YOU MAY NOT REVOKE THIS ADVANCE INSTRUCTION WHEN YOU ARE FOUND INCAPABLE BY A PHYSICIAN OR OTHER AUTHORIZED MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT PROVIDER. A revocation is effective when it is communicated to your attending physician or other provider. The physician or other provider shall note the revocation in your medical record. To be valid, this advance instruction must be signed by two qualified witnesses, personally known to you, who are present when you sign or acknowledge your signature. It must also be acknowledged before a notary public.

NOTICE TO PHYSICIAN OR OTHER MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT PROVIDER

Under North Carolina law, a person may use this advance instruction to provide consent for future mental health treatment if the person later becomes incapable of making those decisions. Under the Health Care Power of Attorney the person may also appoint a health care agent to make mental health treatment decisions for the person when incapable. A person is “incapable”

Page 1 of 8

when in the opinion of a physician or eligible psychologist the person currently lacks sufficient understanding or capacity to make and communicate mental health treatment decisions. This document becomes effective upon its proper execution and remains valid unless revoked. Upon being presented with this advance instruction, the physician or other provider must make it a part of the person’s medical record. The attending physician or other mental health treatment provider must act in accordance with the statements expressed in the advance instruction when the person is determined to be incapable, unless compliance is not consistent with G.S. 122C-74(g). The physician or other mental health treatment provider shall promptly notify the principal and, if applicable, the health care agent, and document noncompliance with any part of an advance instruction in the principal’s medical record. The physician or other mental health treatment provider may rely upon the authority of a signed, witnessed, dated and notarized advance instruction, as provided in G.S. 122C-75.

I, John Smith, being an adult of sound mind, willfully and voluntarily make this advance instruction for mental health treatment to be followed if it is determined by a physician or eligible psychologist that my ability to receive and evaluate information effectively or communicate decisions is impaired to such an extent that I lack the capacity to refuse or consent to mental health treatment. “Mental health treatment” means the process of providing for the physical, emotional, psychological, and social needs of the principal. “Mental health treatment” includes electroconvulsive treatment (ECT), commonly referred to as “shock treatment,” treatment of mental illness with psychotropic medication, and admission to and retention in a facility for care or treatment of mental illness.

I understand that under G.S. 122C-57, other than for specific exceptions stated there, mental health treatment may not be administered without my express and informed written consent or, if I am incapable of giving my informed consent, the express and informed consent of my legally responsible person, my health care agent named pursuant to a valid health care power of attorney, or my consent expressed in this advance instruction for mental health treatment. I understand that I may become incapable of giving or withholding informed consent for mental treatment due to the symptoms of a diagnosed mental disorder. These symptoms may include: speaking very quickly, moving non-stop, not sleeping, not eating, expressing grandiose thoughts,

Page 2 of 8

believing I have special powers, irritability, irrational beliefs—such as that I am a powerful politician.

Page 3 of 8

PSYCHOACTIVE MEDICATIONS

If I become incapable of giving or withholding informed consent for mental health treatment, my instructions regarding psychoactive medications are as follows: (Place initials beside choice.)

JS I consent to the administration of the following medications: lithium, Depakote, aripiprazole,

JS I do not consent to the administration of the following medications: haloperidol

Conditions or limitations: haloperidol makes me restless and stiff

ADMISSION TO AND RETENTION IN FACILITY

If I become incapable of giving or withholding informed consent for mental health treatment, my instructions regarding admission to and retention in a health care facility for mental health treatment are as follows: (Place initials beside choice.)

JS I consent to being admitted to a health care facility for mental health treatment. My facility preference is Durham Hospital. Sandford Hospital

I do not consent to being admitted to a health care facility for mental health treatment.

This advance instruction cannot, by law, provide consent to retain me in a facility for more than ten (10) days.

Conditions or limitations: I do not want to go to a hospital more than an hour from my home.

ADDITIONAL INSTRUCTIONS

These instructions shall apply during the entire length of my incapacity. In case of mental health crisis, please contact:

Name: Jill Smith

Home Address: 11 Smith Guest Road, Durham, NC

Home Telephone Number: 919-555-0303

Work Telephone Number: 919-555-0303

Relationship to Me: wife

Name: Bob Smith

Home Address: 11 Smith Guest Road, Durham NC

Home Telephone Number: 919-555-0303

Page 4 of 8

Work Telephone Number: 919-555-0303

Relationship to Me: son

My Physician:

Name: Ralph Brown, MD

Telephone Number: 919-555-6767

My Therapist:

Name: same

Telephone Number: same

The following may cause me to experience a mental health crisis: Losing my job, not sleeping, fighting with my family, not taking my medications.

The following help me avoid a hospitalization: Taking my medications, scheduling extra sessions with my doctor with my wife. Getting exercise when stressed out.

I generally react to being hospitalized as follows: I can be very cooperative and calm as long as my wife accompanies me and the nurses and doctors treat me respectfully.

Staff of the hospital or crisis unit can help me by doing the following: Give me my medications as needed. Find a quiet place for me. Keep me away from agitated patients. Speak quietly and respectfully to me.

I give permission for the following person or people to visit me: Any member of my family or others that my wife suggests.

Instructions concerning any other medical interventions, such as electroconvulsive (ECT) treatment (commonly referred to as “shock treatment”): If my outpatient doctor and wife recommend ECT I give my permission to administer it. ECT team must be well experienced.

Other instructions: Please make sure my wife gives consent to any medications, tests, or procedures and that she has consulted with my outpatient doctor.

_____ (Initial if applicable) I have attached an additional sheet of instructions to be followed and considered part of this advance instruction.

Page 5 of 8

SHARING OF INFORMATION BY PROVIDERS

I understand that the information in this document may be shared by my mental health treatment provider with any other mental health treatment provider who may serve me when necessary to provide treatment in accordance with this advance instruction.

Other instructions about sharing of information: Please share this information with my primary care physician.

SIGNATURE OF PRINCIPAL

By signing here, I indicate that I am mentally alert and competent, fully informed as to the contents of this document, and understand the full impact of having made this advance instruction for mental health treatment.

10-16-18

Date

XXX

Signature of Principal

NATURE OF WITNESSES

I hereby state that the principal is personally known to me, that the principal signed or acknowledged the principal’s signature on this advance instruction for mental health treatment in my presence, that the principal appears to be of sound mind and not under duress, fraud, or undue influence, and that I am not:

The attending physician or mental health service provider or an employee of the physician or mental health treatment provider;

An owner, operator, or employee of an owner or operator of a health care facility in which the principal is a patient or resident; or

Related within the third degree to the principal or to the principal’s spouse.

Page 6 of 8

AFFIRMATION OF WITNESS

We affirm that the principal is personally known to us, that the principal signed or acknowledged the principal’s signature on this advance instruction for mental health treatment in our presence, that the principal appears to be of sound mind and not under duress, fraud, or undue influence, and that neither of us is:

A person appointed as an attorney-in-fact by this document;

The principal’s attending physician or mental health service provider or a relative of the physician or provider;

The owner, operator, or relative of an owner or operator of a facility in which the principal is a patient or resident; or

A person related to the principal by blood, marriage, or adoption.

Witnessed by:

Liz Apple

Witness

10-16-18

Date

Steve Moon

Witness

10-16-18

Date

Page 7 of 8

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA

COUNTY OF Durham

CERTIFICATION OF NOTARY PUBLIC

I, Ron Brown, a Notary Public for the County cited above in the State of North Carolina, hereby certify that John Smith appeared before me and swore or affirmed to me and to the witnesses in my presence that this instrument is an advance instruction for mental health treatment, and that he/she willingly and voluntarily made and executed it as his/her free act and deed for the purposes expressed in it.

I further certify that Liz Apple and Steve Moon, witnesses, appeared before me and swore or affirmed that they witnessed John Smith sign the attached advance instruction for mental health treatment, believing him/her to be of sound mind; and also swore that at the time they witnessed the signing they were not (i) the attending physician or mental health treatment provider or an employee of the physician or mental health treatment provider and (ii) they were not an owner, operator, or employee of an owner or operator of a health care facility in which the principal is a patient or resident, and (iii) they were not related within the third degree to the principal or to the principal’s spouse. I further certify that I am satisfied as to the genuineness and due execution of the instrument.

This the 16 day of 10, 2018.

Ron Brown

Notary Public

My Commission Expires:10-16-2020

Page 8 of 8

These sample documents were supplied by one of the nation’s leading experts on PAD and AOT, Dr. Marvin Swartz. They should not be construed as legal or medical advice, which you should seek before embarking on any patient plan, particularly one that involves directives for medical care. Dr. Swartz also filled out sample forms on a hypothetical patient for assisted outpatient treatment (AOT).

If you’re interested in reading publications about social policy issues, please see: https://www.scattergoodfoundation.org/think/publications/policy-paper-series/.