During the northern advance to the Yalu River in 1950, UN forces took control of numerous islands off both coasts of North Korea. A year later the Communists initiated concerted action against these positions, retaking half of them by the end of November. The Americans responded slowly to the Red offensive, deploying air and sea power and stationing a regiment of RoK marines on five of the islands in late 1951. By the end of 1952, the Air Force listed thirty-four islands under friendly control, fourteen of which it recommended for rescue purposes. At this point, the USAF had 9 officers and 150 airmen stationed on five islands off the west coast of Korea.1 The UN used these islands as listening posts, staging areas for raids and intelligence operations, radio relay stations, direction-finding stations, navigation beacons, radar sites, and bases for air-sea rescue services.

The importance of these positions to the UN increased as the war bogged down into a stalemate. In mid-February 1952, Fifth Air Force put early warning radar into operation on Cho-do, which was 40 miles north of the 38th parallel, 125 miles behind the front, and about 5 miles from the mainland. It could detect aircraft taking off and landing at the Chinese airfields near the Yalu when the aircraft climbed to altitude, but the radar had no coverage below ten thousand feet over China. Radio intercepts assisted in this early warning duty. In May 1952, Fifth Air Force directed that a small tactical control center be added, and lightweight equipment was airlifted to the island within weeks. In short order, operators on Cho-do began vectoring Sabres against MiGs.2

One function of the islands was to serve as a listening post for radio intelligence. America reorganized its intelligence services and communications intelligence (COMINT) prior to the Korean War, just as it reconfigured its armed forces. This led to the creation in 1949 of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Armed Forces Security Agency (AFSA). The USAF, newly created in 1947, converted what had been a portion of Army COMINT dedicated to Army Air Force’s (AAF) use to the Air Force Security Service.

The reorganization, however, could not overcome serious problems. In contrast to the great code-breaking successes of World War II, when the Allies could read both German and Japanese messages, the condition of American communications intelligence during the early years of the Cold War was dismal. One significant problem was lean budgets. Another major blow fell when the Soviets, having learned through an agent inside AFSA of U.S. penetrations of their ciphers, shut out American intelligence efforts. This resulted in a virtual blackout of information just before the Korean War in what some official intelligence historians have called “perhaps the most significant intelligence loss in U.S. history.”3 Because they had limited resources and focused primarily on the Soviet Union, intelligence agencies gave little or no attention to North Korea, except in connection with the Soviets.

In any event, radio intelligence gave no hint of the 25 June 1950 invasion, a failure that was only exceeded by the failure to warn of the Chinese intervention later that year. At the beginning of the war, AFSA had 3 individuals assigned to North Korean analysis, 2 half-time cryptanalysts and 1 linguist. Staffing increased to 87 by March 1953. In contrast, AFSA had 83 analysts assigned to China duties at the outset of the war, and that number was doubled to 156 by February 1951. Operations were also hampered by shortages of equipment, much of which was outmoded; inadequate numbers of linguists; and, in the field, by difficult terrain.4

The USAF had only two mobile units in 1950. The one in the Far East focused on the Soviet Union rather than Asia because American intelligence believed that the Soviets were more likely than the Chinese to intervene in Korea, since the Chinese were concentrating on a planned invasion of Taiwan. Although that unit quickly switched from monitoring early warning of war to tactical support, progress was slow. It was not until mid-September 1950 that the Americans began round-the-clock surveillance of Chinese communications, and not until December that U.S. personnel began to work on breaking Chinese codes and ciphers. It took the Army’s signals intelligence (SIGINT) unit until January 1951 to begin traffic analysis and until June 1951 to begin issuing daily traffic analysis reports.

The Air Force organized one SIGINT unit in late July 1950. USAF personnel in Seoul quickly made use of a South Korean COMINT unit because there were few Korean speakers in the U.S. military and even a shortage of Korean-American language dictionaries. The Americans provided the Koreans with U.S. rations, pay subsidies, and supplies—in one case medical care for a Korean officer—in exchange for Korean interception and translation work and, later, cryptologic efforts. It was not until mid-1951 that the Army Language School was able to provide Korean linguists in any number to the forces; even then, the shortage of Korean linguists continued to be a problem. The intelligence services later had similar difficulties in providing Chinese speakers, primarily because few were conversant in the Mandarin dialect used by the Chinese Communist radio operators. This situation forced the Army to employ Chinese Nationalist linguists, seventy-five of them by March 1951. Russian speakers were also in short supply.5

COMINT provided valuable information to the UN airmen. The operators intercepted Communist instructions to the MiG pilots and funneled that information in nearly real time to American pilots, using radar plots as a cover. The efficiency of this service improved when the USAF established a listening site on Paengnyong-do, an island behind enemy lines, in mid-1951. Its success and the Chinese shift from high frequency, longer range Morse code communications to very high frequency, shorter range voice communications led the Air Force to beef up the detachment on Paengnyong-do and establish another site on Cho-do in spring 1952.

In January 1951, the USAF used a C-47 to collect Communist radio signals on twelve missions and to drop agents behind Communist lines. In February 1953, the USAF installed COMINT equipment and one operator aboard a C-47, which flew about twenty miles behind enemy lines, serving as a radio relay aircraft. This intelligence was automatically relayed to a ground station on Cho-do and then passed on to the GCI (ground control intercept) site next door. While there is some confusion as to exactly what transpired, the aircraft apparently flew twenty-six missions by mid-March 1953. Beginning in December 1952, RB-50G aircraft equipped with electronic gear and manned by a Chinese or Russian linguist who listened for Communist ground-to-air communications were mixed in with the B-29 bomber formations. In April 1953, the USAF flew RB-50Gs over North Korea and orbited over the Yellow Sea for five hours as they collected COMINT.6

Two incidents dramatically brought together the elements of friendly islands and radio intercepts. At 0900 on 19 June 1951, the Americans intercepted a message from Beijing to a Chinese air unit ordering prop-powered Il-10s to attack Sinmi-do, a relatively large island under UN control located about forty miles southeast of the mouth of the Yalu River. These air attacks were to support a Communist ground assault against Korean forces on the island. The message was quickly decoded, and the information rapidly passed through the Air Force chain of command. The next day, a flight of F-51s spotted and then engaged eight of the Communist bombers, destroying two and damaging three others. The battle escalated as another flight of Mustangs battled six Yak-9 fighters and downed one. In short order, MiG-15s appeared and engaged a third flight of F-51s and its F-86 cover. In the ensuing battle, four MiGs were damaged and one F-51 destroyed.7

Four months later, the Sabre pilots had even greater success. In late October 1951, the Communists issued orders to take over UN occupied islands close to the mouth of the Yalu. The most significant of these was Taehwa-do, an island defended by twelve hundred troops and located forty miles southeast of the mouth of the Yalu and sixty miles north of Cho-do. On the night of 5 November, the Reds attacked the adjacent island of Ka-do. To support their attack, nine twin-tail, twin-engine, prop-powered Tu-2s, escorted by sixteen prop-driven La-11 fighters covered by MiG-15s, attacked Taehwa-do early the next morning. On 14 November, the Reds used Yak fighters to strafe UN forces on Ka-do and quickly captured the island. The next day the Communists hit Taehwa-do in a daylight assault by eleven bombers and then began launching almost nightly bombing raids of both islands. The attack was devastating, killing 60 UN troops and wounding another 122. Just before midnight on 29 November, Communist forces landed on Taehwa-do; an hour and half later, six bombers attacked UN positions. On the afternoon of 30 November, the Communists launched another air assault consisting of Tu-2s, escorted by La-9s and MiG-15s, toward the island.8 It was the same pattern that had worked before, but this time the Red airmen would meet airborne opposition.

The American airmen had prior knowledge of the attack, and on the morning of 30 November, pilots of the 4th Fighter Group were briefed that their mission was to intercept and destroy a group of Tu-2s escorted by La-9s and MiG-15s. The best pilots in the Sabre unit manned all available aircraft. Col. Ben Preston, the group commander, led the thirty-one F-86s and employed unusual tactics. Instead of climbing slowly in loose formation from their base to the Yalu River, as they normally did to save fuel, the Americans flew east of their normal route behind the North Korean mountains, staying low and maintaining radio silence to shield their approach from the Communists. Their efforts were rewarded; they achieved both surprise and success.9

Near the Yalu, the Sabres climbed to altitude, headed west, and took up a combat formation. They spotted the twelve Tu-2s flying at about 180 kts fifty miles from Taehwa-do closely escorted by sixteen La-9s at eight thousand feet.10 However, the Red plan went slightly askew because the Red bombers arrived at the rendezvous five minutes early, throwing off the timing of the planned MiG cover. Preston led the charge, diving on the bomber formation with F-86s from the 334th and 336th fighter squadrons while the Sabres from the 335th remained at altitude to deal with the expected arrival of the MiGs. In short order, Preston radioed Maj. Winton Marshall, leader of the 335th Sabres on this mission, “Bones, come on down and get ’em.”11 Sabres fired, bombers burned, fighters maneuvered, and crews bailed out during the chaotic dogfight. “Everybody was going wild,” one F-86 pilot observed. “Planes were just missing each other, and bullets were literally flying in all directions from both sides. The sky must have been chock-full of lead. Planes were smoking, there were splashes below, and radio fight talk was intense. It was the damnedest violent action I ever saw—kill-or-be-killed destruction.”12 Another American pilot later wrote, “There were parachutes absolutely everywhere, like a mass airdrop of the 82nd Airborne.”13 It was a slaughter: the prop-powered aircraft did not have a chance against the Sabres. According to American accounts, the remaining damaged bombers turned for home before reaching Taehwa-do, dropping their bombs short, according to Chinese accounts. Meanwhile, eighteen of the approximately fifty MiG-15s aloft during the encounter engaged the Sabres. The MiGs could not prevent the debacle and for their efforts lost one fighter to the F-86s.

Two American pilots became the fifth and sixth American aces of the war in the action that day: Maj. George Davis (334FS) claimed four aircraft, three Tu-2s and one MiG; and Maj. Winton (“Bones”) Marshall (335FS), a Tu-2 and an La-9. Davis’s four kills on one mission established a Korean War record.14 Davis’s accomplishment pointed out both the vulnerability of the prop-powered bombers and his excellent marksmanship: he did not exhaust his ammunition, firing only twelve thousand rounds even though he employed the older, less sophisticated Mk 18 gunsight.15 As usual, the two sides differ over the results of the action: the Chinese admit losing four Tu-2s, two La-11s, and one MiG-15, while the USAF credited the 4th’s pilots with destroying eight bombers, three prop-powered fighters, and a MiG-15. This was the highest score the USAF had racked up in the war thus far, exceeded only four times.16 Whatever the true number of losses, this was the last daytime Communist bombing effort. The Reds planned assaults on UN airfields in South Korea on two occasions in 1952 but, fearing reprisals, did not launch them.

Although one Chinese pilot claimed to have destroyed a Sabre, none was lost on this mission.17 The Communists did damage four F-86s in the battle and gave at least two Sabre pilots close calls. Capt. Ray Barton (334FS), flying as an element leader, made a classic gunnery pass on the Red bombers but missed his target. He then came around again, closed onto the tail of a Tu-2, fired a long burst, observed strikes over the entire aircraft, and watched the bomber explode. As he chandelled to make a third run, he looked to his rear and saw a jet following him that he assumed was his wingman, John Burke.

Barton flew through what was left of the Chinese bomber formation without scoring any hits and was headed for home when an orange fireball passed over the top of his canopy. The jet behind him was not a Sabre; it was a MiG!18 Barton turned as hard as he could, circled, and outmaneuvered his attacker, who broke off his attack. Then four MiGs, followed a bit later by two others, attacked Barton. The F-86 pilot was able to shake off his pursuers by climbing into the sun. Now at ten thousand feet he headed south and passed over Taehwa-do, where two more MiGs bounced him. Barton maneuvered desperately while radioing for help. Fortunately, George Davis heard his call and, although already short of fuel and south of Taehwa-do, flew to the rescue. Davis spotted a MiG at three thousand feet and smoked him. After seeing the MiG crash into the sea, Davis joined up with Barton and the two headed for home, Barton with one credit, and Davis, with four victories in the engagement, now an ace. The USAF awarded Davis the Silver Star for his actions.19

“Bones” Marshall was another Sabre pilot who almost didn’t make it home. After scoring two victories, he was observing the dogfight when his wingman, John Honoker, called “break hard.” Marshall lost consciousness as shells from an La-9 attacking head-on tore through the Sabre’s canopy and hit the armored headrest. Honoker latched onto the Red fighter, covered it with hits, and watched it explode and fall in three sections into the sea. Meanwhile, Marshall was in trouble, wounded in the head, neck, and hands, and his aircraft was damaged. Marshall’s helmet was split open, forcing him to hold his oxygen mask to his face. Cold and injured, he managed to fly his Sabre back to base. But the saga was not over, for in the landing pattern he was forced to go around to allow another F-86 to land first. This was George Davis, who—landing without power—had the right-of-way over Marshall’s plane, which was only damaged. Marshall landed safely, flew again, and rose to flag rank in the Air Force.20

The Communists continued to press the UN forces on the islands. In early December, UN forces evacuated two hundred partisans from Taehwa-do after the Chinese landed on the island. The Reds were well aware of the activities on Cho-do and attacked it with both artillery and aircraft. On 5 September 1952, three Communist guns on the mainland fired about 100 to 120 shells at the island, injuring six civilians but no UN personnel. One Royal navy and three U.S. Navy ships responded, as did UN aircraft.21 Shortly after midnight on 13 October 1952, Cho-do radar observed six aircraft headed toward the island. About half an hour later a USAF crash boat spotted four aircraft orbiting north of the island at about one thousand feet. From the sound of the engines, their low air speed of 80–85 kts, whistling sounds consistent with guy wires on a biplane, and light bomb load, the USAF concluded the attackers were probably PO-2 biplanes. The Red aircraft made seven separate bomb runs to deliver fourteen bombs. Two American antiaircraft gunners were wounded and four Korean civilians were killed and five wounded in a nearby village.22 The Communists launched a similar attack on Paengnyong-do on 12 November without any physical military effect. Two weeks later, on 26 November, Cho-do radar tracked six aircraft, which attacked in two waves of three aircraft. U.S. forces observed explosions from about four to five bombs from the first wave and six from the second, none of which caused any casualties or damage. There were further air attacks on 5 and 10 December.23 By this time the UN had beefed up the defenses of the islands with more antiaircraft guns and some searchlights.

The airmen also attempted to intercept the raiders with night fighters. The major problem was that the fabric-covered Communist aircraft gave faint radar returns, were small, and flew slow and low. The airmen called these aircraft, “Bed Check Charlie.” The Soviets had used these tactics during World War II against the Germans, who noted that the attacks “caused considerable discomfiture and not a few losses.”24 USAF F-94 night fighters established radar contacts a half dozen times, as did a Marine F4U on one occasion, but all without success. Finally, a Marine F3D Skynight downed one of the night raiders on 10 December 1952. The Communist air attacks on the islands stopped for a number of months; but then, shortly after midnight on 15 April 1953, they returned to Cho-do, killing two antiaircraft gunners and destroying one gun. On 6 May, Cho-do gunners may have destroyed an attacking aircraft, although no wreckage was found to confirm that claim. The airmen were increasingly frustrated by these attacks and tried all sorts of efforts to foil them: Marine ADs, B-26s, armed T-6s, flare-dropping transports along with the F-94s, and revised rules of engagement for antiaircraft guns. Although the USAF credited the F-94s with two kills, two were lost in the low-speed, low-altitude, night engagements.

The nighttime heckling raids extended beyond the islands and scored successes. On 17 June 1951, a Communist raider bombed the Kimpo airfield, home of the 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing, destroying one F-86 and damaging two others. Two years later the attacks were still hitting installations in South Korea. Two were notable, one that jarred the mansion of the RoK President on 15/16 June 1953 and another the next night that destroyed five million gallons of fuel at Inchon. The most successful defensive effort was turned in by Navy Lt. Guy Bordelon, borrowed from the carrier Princeton, who claimed five of the night raiders during June and July 1953 in his F4U and became the only American ace of the war who did not fly an F-86. In addition to the two USAF and five Navy credits, the Marines claimed four of the night raiders.25

The two islands also served as a base and position for rescue operations. Prior to World War II, the Germans pioneered in this area and the Luftwaffe was thus the best prepared of the warring air forces when air operations took place over water. In contrast, the British got a late start, not coordinating RAF and Royal Navy rescue operations until August 1940. In a similar manner, the AAF was late in preparing for rescue operations. In Western Europe, the Americans initially depended on the British for rescue services and only began their own air sea rescue service through the Eighth Air Force in May 1944. British and Americans, mostly the British, rescued 36 percent of almost 4,600 Eighth Air Force airmen who were reported to have ditched or bailed out over water. A much greater percentage of AAF operations against the Japanese were over water. In the B-29 campaign, the AAF rescued 42 to 48 percent of about 1,424 men, in 129 aircraft, who went down at sea. In the entire war, approximately 5,000 AAF aircrew were rescued. In March 1946, the AAF established Air Rescue Service and the next month assigned it to Air Transport Command.26

When the Korean War erupted, the USAF had two rescue units stationed in the Far East, the Second Air Rescue Squadron, based on the Philippines and later at Okinawa, and the Third Air Rescue Squadron, on Japan. The USAF had organized the latter in February 1944 for operations in the Pacific theater, where it made 220 saves. Within a month, the Air Force dispatched rescue L-5 single engine liaison aircraft and H-5 helicopters to Korea and then, late in July, sent four SA-16 amphibians to the Third. In March 1951, two test YH-19s manned by Air Proving Ground Command personnel arrived in the theater. These two helicopter types and the SA-16 were the rescue workhorses of our story.

Grumman designed the twin-engine, prop-powered SA-16, the Albatross, for the Navy. It first flew in October 1947, and the manufacturer delivered 297 to the Air Force. The Albatross carried a crew of as many as seven, as well as six passengers. It could fly 3,220 statute miles and as long as twenty-three hours; fitted with Jet Assisted Takeoff (JATO) bottles and reversible propellers, it could take off and land in short distances.

The Sikorsky H-5 made its maiden flight in August 1943. Manned by a crew of two, it could lift two others in external litters. It was limited in flying performance, with a top air speed of 106 mph and designed maximum range of 360 statute miles although the USAF put its effective radius at a mere 85 miles.

Sikorsky’s H-19 had a gross weight of 7,900 pounds, compared with the H-5’s 4,800 pounds. First flying in November 1949, it had a three-man crew and could carry up to ten others. The H-19 had a maximum speed of 112 mph and a 360-statute mile range, although the USAF put the radius at 120 miles. In addition to its improved performance, it brought a significant innovation to rescue operations: a one-hundred-foot cable with a sling that was powered by a hydraulic motor. With it, rescues could be accomplished without setting down.27

During the Korean War, Air Force rescue units recovered 170 of 1,690 USAF aircrew who went down in enemy territory. Helicopters accounted for 102 men, or 60 percent, of those rescued; SA-16s, for 66, or 39 percent; and liaison aircraft, the remaining 2 men. The Air Force also rescued 84 other UN airmen, in all bringing out 996 UN servicemen from enemy territory. Because of the excellent rescue services available, the pilots’ chances of rescue were good, despite the fact that they lacked survival training, if—and of course this was a big if—they could make it to the sea. For the UN had not only air, but also sea, superiority.28

In November 1951, the USAF ordered that three SA-16s be kept in commission at Seoul. That fall, SA-16s would orbit north of Cho-do when the UN launched air attacks against positions in northwest Korea. But the winter weather hindered the amphibious rescue aircraft (it could not operate in seas with waves greater than five feet and had problems with icing), so the Air Force began to use helicopters in December. Because the USAF did not initially consider Cho-do secure, the USAF dispatched two H-5s from Paengnyong-do to the island for daytime alerts in good weather. The USAF later established a detachment of two helicopters there in January 1952. The next month the rescue unit began to convert from the smaller, more limited H-5s to the larger H-19s. Eventually the Air Force stationed two choppers on Cho-do and a third on Paengnyong-do. The USAF also stationed a number of crash boats at these islands along with the aircraft.29 This small force proved very effective.

Cho-do was an excellent rescue position, located halfway between the Yalu River and friendly airfields in South Korea. In many ways it served the same function for the F-86s in Korea as Iwo Jima had served for the B-29s during World War II, except that the jet fighters could not land at Cho-do. However, at least three landed on the beach at Paengnyong-do, about thirty-five miles south of Cho-do, and returned to their Korean bases after refueling.30

The Sabre, flying at high speed for combat purposes, had limited endurance and the American fighter pilots attempted to get every moment they could in MiG Alley. Fortunately for the pilots, the F-86 had a very good fuel counter. It was not uncommon for the Sabre pilots when returning to base to shut down their engines to conserve fuel and restart them as they neared the airfield. Dead stick (unpowered) landings were frequent; Harrison Thyng, commander of the 4th in 1951 and 1952, states that his unit averaged ten to twelve such landings a week but lost only one aircraft as a result. Two factors aided this technique. First, the F-86 was a very streamlined aircraft and could glide clean (landing gear and flaps up, speed brakes retracted) for an amazing distance, 70 nm (nautical miles) from thirty thousand feet in no-wind conditions. Usually a westerly wind, sometimes a stiff jet stream, extended that distance.31 A number of pilots tell of running out of fuel, taxiing in after landing or shutting down after a mission with less than one hundred pounds of fuel remaining. On many occasions there was more than one fighter approaching the Korean airfield in an unpowered glide.

Some pilots, however, could not get all the way home because of lack of fuel, combat damage, or mechanical problems. During the course of the war, forty-two Sabre pilots were recovered from the sea or from behind enemy lines. SA-16s made about one third of these rescues; helicopters, most of the rest. The first of these occurred on 13 September 1951, when an SA-16 plucked 2nd Lt. Joseph Burke out of the Yellow Sea following his ejection after his engine blew up.32 Sabre pilots had a much better chance of rescue than did other USAF airmen: in all, one out of four Sabre pilots was rescued, compared with one out of ten AF aircrew. The Sabre’s higher operating altitude, coupled with the UN sea supremacy and the proximity of MiG Alley to the water, bolstered the Sabre pilot’s chances of rescue. Other factors were the technology provided by the SA-16s and helicopters; bases that put the rescue aircraft within range of the downed pilots; an organization of rescue; and, perhaps most of all, rescue personnel willing to go into harm’s way to truly operate in the spirit of the organization’s motto: “That Others May Live.”

Among the forty-two F-86 pilots rescued, sixteen had registered, or would register, victory claims. Nine had scored prior to their rescue mission (24 credits), nine scored on the day of the rescue (10.5 credits), and eight scored on succeeding missions (29 credits). Two, Frederick Blesse (334FS) and Joe McConnell (39FS), were already aces; and two more, Clifford Jolley (335FS) and Lonnie Moore (335FS), would go on to become aces. To put this into a broader perspective, the USAF lists a total of about 220 F-86s lost on both combat and non-combat missions in the Far East during the Korean War. The USAF put total Sabre pilot casualties at forty-seven killed, sixty-five missing, and six wounded.33 The recovery of these pilots was quite an accomplishment.

It is not necessary to relate every rescue, but a few accounts are in order. Enemy fire damaged Lt. James Bonini’s (16FS) Sabre on 8 August 1952. He made it to the vicinity of Cho-do and ejected. Within a minute and ten seconds, an SA-16 crew pulled him from the sea. This certainly was one of the fastest rescues on record.34

Joe McConnell had seven credits when he took off on 12 April 1953, leading a flight of four F-86s.35 The Communists were up in force at that moment, and four MiGs engaged the four Sabres. McConnell chased the MiGs toward the Yalu and then maneuvered onto the tail of one and was just lining up to fire when another Communist fighter latched onto his tail. McConnell’s wingman radioed “BREAK!” McConnell looked rearward, did not see the MiG that was low and behind him, and continued to pursue the MiG to his front. The Red fighter fired and hit McConnell’s aircraft. The F-86 shuddered and slowed down. In McConnell’s words, he looked back to see “the sky was full of MiGs.” The American ace immediately executed a barrel roll, got behind his assailant, fired, and destroyed the MiG. (Prior to nailing McConnell, Semen Fedorets had scored his fifth victory, downing 1st Lt. Robert Niemann, 334FS.)36

McConnell’s aircraft was emitting heavy smoke and, with a smashed radio and engine power at 50 to 70 percent, was in serious trouble. McConnell headed south as his number three man, 1st Lt. Harold Chitwood, notified Air Sea Rescue of the situation. He spotted a chopper heading north that turned around and paralleled the fighters’ southward course. McConnell ejected and was pulled from the water in less than two minutes by an H-19 helicopter piloted by Bob Sullivan and Don Crabb. McConnell later told his sister, “I barely got wet.”37

The Air Force released a photo to the public of an H-19 with rescue markings hovering above the water’s surface with a man in a rescue hoist and a caption crediting Sullivan with McConnell’s rescue. This photo was widely published, appearing within days in papers across the country. It also appeared in the USAF’s official history of the Korean War with the caption “Capt. Joseph McConnell was picked up within minutes after bailing out of his damaged Sabre.”38 In fact, the helicopter that pulled the ace from the sea did not carry the rescue markings, as it was not from the rescue unit but a special operations outfit also using Cho-do as a base. This staged photo was probably a USAF attempt to celebrate the rescue abilities of the Air Force without exposing this clandestine unit.39

The rescue pilot, Bob Sullivan, relates that on 12 April two choppers were scrambled when they got a call that F-86s were heading south from MiG Alley with two in bad shape. One helicopter, piloted by Dick Kirkland from the rescue unit, and one from special operations flew north toward the fighters. First Lt. Norman Green (335FS) went into the sea north of the helicopters and was rescued by an SA-16 crew. Meanwhile, the F-86 pilots reported that McConnell had ejected just north of Cho-do and had a good chute. Sullivan saw McConnell’s fighter go into the water about three miles west of his position and then spotted McConnell’s chute just off to his right, three hundred to four hundred yards away. As he recalls, “The weather was great, the sea was fairly calm, and the rest is about a school book pick-up, maybe better!”40 Sullivan directed the chopper’s medic, Arthur Gillespie, to run out about twenty feet of cable and approached the downed pilot in a sideways, crab-like movement, so that he could keep him in sight through the side window. Gillespie quickly pulled the Sabre ace aboard the H-19. McConnell’s first words to his rescuers after “thanks” were that he had a mission at 1530, and he asked Sullivan if he could make that, either a sign of bravado or his lack of concern over his recent experience. We may assume that Sullivan replied that he did not think McConnell would be back in time for that one.41

McConnell was back at his base that night. The next day McConnell made a low pass down the valley on Cho-do just as Sullivan was coming up it in the opposite direction. In Sullivan’s words the “’86 pitched up off the valley floor, looking like it was moving at the speed of light.”42 Four days later McConnell scored his ninth victory and finished the war with sixteen credits as the top American ace of the Korean War.43

For all the praise the USAF Air Sea Rescue Service deserves, it was not 100 percent successful. One of its embarrassing moments was “one that got away,” or perhaps more accurately, one that Air Force rescue services did not rescue. Col. Albert Schniz’s story is an outstanding survival effort that reflects well on him, but not on the USAF. However, perhaps most of all, it again demonstrates the role luck and individual effort plays in human affairs.

Schniz downed four Zeroes in World War II and half of a MiG on thirty-eight missions in Korea. On 1 May 1952, the 51st Wing operations officer led a flight of F-86s into MiG Alley. Schniz’s aircraft was hit in a dogfight, perhaps by friendlies, damaging the hydraulic controls and starting a fire in the tail pipe. For unexplained reasons, his attacker allowed him to slip away, but the Sabre was badly damaged and barely under control. Schniz could only adjust his altitude by changing engine power to create a porpoising action. He headed southward toward Cho-do, but knew he could not make it because he was losing altitude with each porpoising cycle. As he descended below 1,500 feet, he spied a large island below with a village at the north end and two apparently deserted reefs at the south end. He radioed his position to rescue forces and stated his intention to bail out over the south end of the island. He was told to spend the night there and wait for pickup the next day.

Schniz ejected at a low altitude (below one thousand feet) and barely survived. Although he had not had any escape, evasion, or survival training, the colonel had seen an escape and evasion training film only a week before and prepared to put what he had seen into practice. He hit the water about one hundred feet offshore, between the two reefs. After inflating his life preserver, the pilot attempted to apply a technique shown in the movie: using the partially inflated chute as a parasail to get him to dry land. This attempt almost killed him. Schniz got ensnarled in the parachute risers and the chute collapsed and began to sink, threatening to take him down with it. After a number of dunkings, he was able to inflate his one-man dinghy and get free of the chute. (He was very lucky not to have drowned, and to have gotten rid of the chute for, unlike other pilots, he did not carry a knife.) After a number of attempts, Schniz made it into the raft. He tried to use his survival radio, but it was inoperative. He then attempted to make it to shore, but he could not find any paddles, and his efforts to use his hands to propel the raft proved futile. The tide carried him out to sea. The exhausted pilot fell asleep and awoke seven hours later to the sound of breakers; the tide was now moving him shoreward. At this point, a low-flying USAF B-26 flew overhead, and Schniz attempted to light one of his flares, but it fizzled out. It took him five more hours to reach shore.

Schniz now began the land phase of his survival effort. A journalist who wrote of it was not too far afield when he titled his story, “Robinson Crusoe of MiG Alley.” Although the downed pilot lacked matches, he did have a Zippo lighter that worked, allowing him to start a fire and dry his clothes. Pushing inland, Schniz found a small settlement of four houses in a clearing. After observing the huts for a time and circling them to ensure they were uninhabited, he entered and found them filthy and littered with debris, suggesting that UN troops had been there weeks earlier. Schniz also discovered a stream that provided water, which the pilot boiled before drinking. Scavaging around the area, he found a few ears of unharvested corn, a patch of dandelion greens, and a few spring onions. These provided his first meal in twenty-four hours.

The next day he pushed toward the village and, after observing it for three hours, found that it, too, was deserted. The next night, hearing a B-26 fly over the hut where he slept, Schniz fired his second and last flare, but the aircraft’s crew apparently did not see it. The next day he constructed an “SOS” signal in a clearing, the first of a number of signals he built to attract the attention of UN airmen. That night, when another aircraft flew over, he lit the signal; it fizzled out. Schniz continued to explore and found some tools and a bag of dried beans. By this time, he was losing both weight and strength. After about two weeks, Schniz decided to move into the village where he found twenty-five bags of rice, a fresh-water well, and two drums of fuel. The next day he built a signal fire fueled by the diesel oil, which attracted a F-51. He waved wildly, but apparently the pilot mistook the bedraggled aviator for a Korean. On another occasion, Schniz spotted a junk sailing just off the beach, yelled at the one man aboard, and ran toward him waving his arms. The boat turned around and sailed off. He built more signals, this time “MAYDAY,” the international distress signal, and signal fires. Although aircraft flew over the island, rescue did not follow. Schniz finally built a signal consisting of three rows with the letters “I M” “U S A F” “P” which he meant to signal, “I am a USAF pilot.”

At this point, he almost made a fatal mistake. Schniz had found some trip flares; when a B-26 flew over the island, he attempted to fire the flares, which failed to ignite. As Schniz picked one up, it exploded in his face, burning, blinding, and deafening him. Fortunately, he recovered both his sight and hearing. Using boiling water, he sterilized some needles he had found and took shrapnel out of his injured hands.

After this scrape with disaster, events took a dramatic turn on the night of 9 June 1952. Around 0230 he was jarred awake by a bright light in his eyes. Someone grabbed him and he heard voices speaking in Korean. After one of his visitors saw his colonel’s eagles he heard in broken English “American. American colonel.” Schniz responded, “I surrender. I surrender.” But the Koreans patted him on the back and shouted “OK, OK.” They were friendly Korean partisans, sent onto Taehwa-do by Lt. James Mapp after he saw an F-51 go down nearby. A secondary account provides more detail but not necessarily more accuracy. It claims that a routine sea patrol saw Schniz’s fire and investigated. It goes on to state that the downed pilot had reported his position in error, and thus the search for him was misdirected. Further, the rescue people had seen the activity on the island but concluded that since no airmen were reported down in that area, it was a Communist attempt to ambush a rescue effort. The Americans put together and launched a commando team to check the island out just as Schniz was found. In any event, after thirty-seven days, the F-86 pilot was back in friendly hands.44

An L-5 liaison aircraft brought Schniz back to the 51st’s base at K-13, happy, rather thin, and bug bitten. One observer noted that “he looks and acts a little strange, as might be expected after what he has gone through, and still seems to be in a state of semi-shock.”45 The next night, he attended a drunken party to celebrate his safe return and the departure of Gabreski. After talking to a number of individual officers about his ordeal, he addressed the entire group of about 150 officers for about an hour and a half. He ended by relating how, on more than one occasion, he was saved by breaks that he attributed to God. So this epic survival story ended successfully, marred by numerous mistakes and errors by the pilot and the USAF, but certainly a testament to Schniz’s determination and luck.46

Not all of the F-86 experiences ended successfully. On 11 March 1952, MiGs damaged 1st Lt. John Arnold’s (16FS) Sabre. Arnold headed for Cho-do but flamed out en route due to a lack of fuel. He attempted to make a dead-stick landing on a short emergency strip on the island but overshot, crashed, and died. Apparently, he did not bailout over the island because he could not swim. Arnold was one of at least four Sabre pilots killed attempting to reach Cho-do.47

Other failed rescues demand attention. On 3 February 1952, enemy fire damaged 1st Lt. Charles Spath’s (334FS) F-86. Spath made a successful bailout and radioed that he had broken his leg and was unable to walk. A nearby force of guerrillas heard the transmission and was able to move the downed aviator before the Communists arrived. Fifth Air Force intelligence personnel planned to pick up the Sabre pilot with a rescue H-19 helicopter. It took several weeks to plan the operation due to the danger presented by the Reds, the distant location, and high altitude of the area.

Capt. Gail Poulton was assigned the mission and noted a number of inconsistencies in the situation that raised his concern that the mission had been compromised. On 22 May 1952, Poulton approached the pickup point and talked with Spath. When asked how many people were with him, Spath answered that he did not know. This increased Poulton’s suspicions, and he then asked several more questions that Spath answered with ambiguous replies. At this point, Poulton laid out the situation: “We are here to pick you up, if everything down there is OK. You are giving me uncooperative, and unclear answers, . . . I have leveled off and discontinued my approach . . . and we’ll abort this rescue attempt if you don’t answer my questions fully . . . in the next 15 seconds.” Spath responded “you can chalk me off for saying this, but get the hell out of here; it’s a trap.” Spath died in captivity a few weeks later.

On 27 March 1953, another H-19 attempted a pickup of a downed F-86 pilot, most likely squadron leader Graham Hulse, an RAF exchange pilot who was believed to be either evading capture or with friendly guerrillas. Hulse, who already had 1.5 credits, shared another MiG with his wingman when he was downed on 13 March 1953. After damaging a MiG, Hulse overshot his target, who proceeded to shoot off Hulse’s wing. The location was only twenty-six miles from Antung, China, one of the deepest helicopter penetrations of Red territory during the war. Escorted by a rescue SA-16, a special operations chopper that was piloted by Capt. Frank Westerman and Lt. Robert Sullivan did not find the pilot but did encounter a number of well-armed hostiles in the designated area.48 This probably was a Communist trap because the Communists used downed American airmen to lure in and capture rescue helicopters, as they apparently did to one or two navy choppers on 2 and 8 February 1952. Interrogations of Communist prisoners in the first half of 1952 revealed that the Reds trained fourteen men to lure UN helicopters with cloth and hand signals.49

The islands clearly were an asset to UN forces and the F-86 pilots in particular. Cho-do and Paengnyong-do provided radar and radio intercept coverage that aided the airmen in the air battle. Most of all, these islands were very valuable in getting F-86 pilots home, either directly through radar services and radio relays or indirectly by rescue operations.

The Sabre started out as a straight-winged aircraft as this North American model illustrates. Boeing Company Archives

North American trucked the XP-86 from Los Angeles to Muroc Field. It arrived for its flight tests on 10 September and made its maiden, 50-minute flight on 1 October 1947. Boeing Company Archives

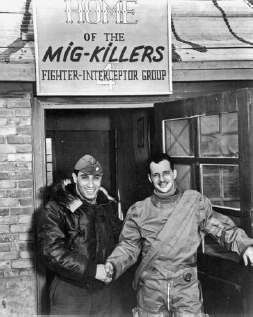

George Welch (on left) was the chief test pilot associated with the F-86; Francis Gabreski (on right) commanded the 51st Fighter Group and downed 6.5 MiGs in Korea. Welch had 16 credits and Gabreski 28 in World War II. They both were at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, where Welch downed 4 Japanese aircraft. Boeing Company Archives

Aircraft number 597 was the first of three experimental XF-86s built and tested by North American. They flew it for 98 hours before turning it over to the Air Force in December 1948. Note the wing slats and the lack of armament. Boeing Company Archives

The Air Force combat tested 20-mm cannon on the F-86 in a project codenamed GunVal. While the tests went well in the United States, firing the guns at high altitude in combat over Korea caused the engine to stall, resulting in the loss of two aircraft. Boeing Company Archives

North American tested aerial refueling with a hose system and, as shown here, a flying boom from a KB 29. Boeing Company Archives

The USAF used both aircraft carriers and merchant ships to transport Sabres to Japan. HRA

More Sabres were lost to accidents than to MiGs. Capt. Clifford Thompson crashed on 7 September 1951 after his engine failed as he attempted a go-around. He suffered minor injuries; the Sabre was wrecked. HRA

51st Fighter Group F-86 taking off in June 1953. HRA

The checkerboard tail pattern indicates aircraft of the 51st Fighter Group in this photo from October 1952. NARA

After damaging a MiG, the Sabre overshot his smoking victim. The MiG then fired on the F-86 and scored a hit that blew off the Sabre’s wing (frames 4 through 6). The wingman, whose gun camera took these pictures, then dispatched the Communist fighter. NARA

Maj. Gen. Albert Boyd (on right), commander of Wright Air Development Center, was one of five USAF pilots who flew the defecting MiG-15 during the initial American tests over Okinawa. Note the MiG’s USAF markings, wing fence, and high horizontal stabilizer. USAF

MiG taking off with an F-86 chase aircraft in background. The USAF ran extensive tests on the defecting North Korean MiG-15. HRA

The photo shows B-26s flying over Cho-do toward North Korea (seen in the background). This island, well behind Communist lines and just off the coast of North Korea, provided intelligence and rescue services and served as a base for guerrilla and agent activities. HRA

Five F-86As of the 4th Fighter Group in mid-1951. Note the extended wing slats. HRA

Capt. Dolph Overton set a record by downing five MiGs in four days. But when the ace admitted crossing the Yalu to accomplish this feat, he was sent back to the States under a dark cloud. HRA

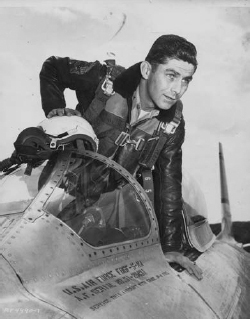

Capt. Joseph McConnell was the leading American ace of the war, with sixteen credits. Midway in his tour, he survived a bailout into the Yellow Sea. USAF

Capt. Joseph McConnell, America’s top ace of the Korean War, looks on as President Dwight Eisenhower shakes hands with Capt. Manuel Fernandez, the number three ace. National Museum of the USAF

Maj. James Jabara (on left) had 6 credits and was flying his second tour when Capt. Manuel Fernandez (on right) downed his fifth and sixth MiG on 18 February 1953. Jabara ran his score up to 15, the second highest, and Fernandez to 14.5, the third highest. NARA

Clockwise from lower left are some of the aces of the 4th Fighter Group: Maj. Winton Marshall (6.5 credits), Col. Benjamin Preston (group commander, 4 credits), Maj. George Davis (14 credits), Maj. Richard Creighton (5 credits), Col. Harrison Thyng (5 credits), and Capt. Kenneth Chandler (1 credit). Davis, who was killed in action, had downed seven Japanese aircraft; Thyng, five aircraft; and Creighton, two German aircraft in World War II. HRA

These six 335th Squadron (4FG) pilots scored at least one victory during August 1952. Standing from left to right: Maj. Edward Ballinger (1 credit), Maj. Frederick Bleese (10 total credits), Maj. Richard Ayersman (2 credits), and Capt. Leonard Lilley (7 credits). Kneeling left to right: Lt. Charles Cleveland (4 credits), Lt. Gene Rogge (1 credit). HRA

Five of the eleven American aces with 10 or more victories. From left to right: Capt. Lonnie Moore (11 credits), Col. Vermont Garrison (10 credits), Col. James Johnson (10 credits), Capt. Ralph Parr (10 credits), and Maj. James Jabara (15 credits). Jabara was the first ace of the war and ended the conflict as the second highest scoring American ace. Parr downed the last Communist aircraft in the war. NARA

This 4th Fighter Group F-86E sustained battle damage on 24 June 1952 and was written off. HRA

Maj. John Bolt was the only non-USAF jet ace of the War. The Marine claimed six Japanese aircraft in World War II and six Communist jets in the Korean War. Department of Defense

Lt. Simpson Evans (on left) was one of the few naval aviators who flew F-86s in Korea. The USAF credited him with one MiG destroyed. Air Force Lt. Col. Bruce Hinton (center) scored the first Sabre victory. He went on to claim one more. Lt. Paul Bryce is on the right. NARA

Maj. John Glenn, shown here after his first victory, was another Marine who flew F-86s in Korea. He claimed three MiGs over a ten-day period in July 1953 and probably would have been an ace had the war not ended first. USMC

Maj. Thomas Sellers was a Marine exchange pilot who flew with the 4th Fighter Group. Just days before the war ended, he downed two MiGs, but in turn was shot down and killed. Sharon Sellers McDonald

The USAF credited Maj. Felix Asla with four MiGs destroyed before he was killed in combat. HRA

Nine of the twenty-five pilots who were aces at the time attended a conference in Washington in early 1953. Seated on floor, left to right: Col. Francis Gabreski (6.5 credits), Lt. Iven Kincheloe (5 credits), Maj. William Wescott (5 credits), Lt. James Kasler (6 credits), Maj. William Whisner (5.5 credits). Second row left to right: Lt. Col. John England, Capt. Robert Latshaw (5 credits), Capt. Ralph Gibson (5 credits), Gen. Nathan Twining (Vice Chief of Staff), Secretary of the Air Force Harold Talbott, Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg (Chief of Staff), Capt. Frederick Blesse (10 credits), Col. John Meyer (2 credits), Col. Harrison Thyng (5 credits). Standing left to right: Col. Donald Rodawald and Col. Clay Tice. NARA

Lt. Dayton Ragland was one of the few African-American pilots who flew F-86s in combat in Korea. He was the only black USAF pilot to claim a victory. He survived Korean captivity but was killed in action in Vietnam. HRA

Lt. Col. Glenn Eagleston’s Sabre was badly damaged in a dogfight in June 1951. The port guns absorbed the impact of one of three cannon hits and protected the pilot. HRA

F-86F in flight. USAF

The F-86D’s prominent nose housed a radar antenna that gave it a distinctive appearance. Instead of guns, it was armed with twenty-four 2.75-inch unguided rockets housed in a retractable tray. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

More FJ-3 s were built than any other of the naval versions, 47 percent of the 1,148 Furies manufactured. It served with both the Navy and Marine Corps, operating from both land and carrier bases. Note the refueling probe near the right wing tip. Boeing Company Archives