Instituto Superior de Engenharia do Porto, Instituto Politécnico do Porto, Portugal

Instituto Superior de Engenharia do Porto, Instituto Politécnico do Porto, Portugal

Model-Driven Engineering Approaches

Gamification has been applied in diverse areas to encourage participation, improve engagement, and even modify behaviors. However, many gamified applications have failed to meet their objectives, and poor gamification design has been pointed out as a recurrent problem, despite a growing number of gamification frameworks and their valuable guidelines. Model-driven engineering approaches have been proposed as possible solutions to the deficient, and incoherent, inclusion of several dynamics and mechanics. They allow achieving a formalism that can avoid many errors and inconsistencies in the process. Moreover, these efforts are necessary to achieve a conceptualization of gamification that facilitates its inclusion in applications. Three proposals are analyzed, all based on domain-specific languages (DSL), which allows users to design complex gamification strategies without requiring programming skills. The MDE approach can be used to enrich gamification design by providing a platform that involves various concepts and the necessary connections between them to ensure harmonious designs.

Games are not just about entertainment, not now, nor over the years. America’s Army game series, for instance, included the AA game (Land & Wilson, 2006). It was designed to increase recruiting and values such as loyalty, and honor, and was “the first successful and well-executed serious game that gained total public awareness” (Djaouti, Alvarez, Jessel, & Rampnoux, 2011). Soon game aspects attracted the attention of developers in an attempt to have its benefits in other applications as well. The classic definition of gamification is the use of design elements characteristic of games in non-game contexts (Deterding, Dixon, Khaled, & Nacke, 2011).

This chapter addresses gamification, introducing its various definitions provided by different authors, as well as comparing and contrasting the views reflected in each of them. The problem of gamification not achieving certain established goals due to poor design is also analyzed along with some possibilities to address it, such as gamification-related guidelines provided by many frameworks.

The solutions present in this chapter follow a Model-Driven Engineering (MDE) approach in combination with Domain-Specific Languages (DSLs), providing domain experts a platform to develop gamification strategies. The following section contains background information about what gamification is, relevant frameworks for the development of gamification in systems, and an introduction to MDE and DSL.

The main objective of this chapter is to discuss and disseminate an alternative, and less widely used, method of formalizing gamification strategies. Through this method, domain experts can aggregate various factors present in a DSL to develop harmonious solutions that can later be integrated into the desired system.

In the remainder of this chapter, gamification concepts and applications are explored in its second section (“Background”). In the third section, an analysis is performed on some of the researched frameworks, followed by a section dedicated to MDE approaches in gamification. The final section explores the future of gamified applications and the role of MDE.

Gamification has been explored by various authors, and thus different definitions have been provided. These definitions are presented and compared in this section. Furthermore, to showcase what gamification can offer, some examples of successful applications are analyzed within this section, as well as examples of applications that did not produce the expected results.

The first definition to be analyzed is: “Gamification is the use of game design elements in non-game contexts” (Deterding et al., 2011). The authors justify their definition by emphasizing the following words:

For the keyword “game”, the authors began by clarifying that gamification was related to games, but not related to “play”. The concept of games being a subcategory of the broader category “play”. Then the authors proceed to explain that games are defined by explicit rule systems and competition between actors of those systems towards goals or outcomes. The concept of gamefulness is described as a “systematic complement” to playfulness. Furthermore, this is due to gamefulness relating to the qualities of gaming over the qualities of playing.

As for the keyword “element”, the authors point out the difference between a serious game and a gamified application. The design of the former is of a full-fledged game, while the latter aggregates game elements. Game elements were defined as features that are characteristic of games, as in features that are common and significant when it comes to gameplay.

When it comes to the keyword “design”, it was first stated that, in this context, the concept of “gamification” is reserved for the usage of game design and not the usage of game-based technologies. As a result of their research, game design elements were categorized through different levels of abstraction:

Lastly, for “non-game contexts” the authors consider that the overall context is what separates gamification from a meta-game. Gamification makes use of game design elements that do not follow a specific game dynamic, while the meta-game maintains the context, consequentially remaining game design.

A second definition for gamification considers gamification as “a process of enhancing a service with affordances for gameful experiences in order to support user's overall value creation” (Huotari & Hamari, 2012). This definition focuses on the goal of gamification and not the methods used. Furthermore, this is due to what the authors concluded in their research about game elements and how they do not implicitly create gameful experiences. As such, gamification was defined as a process of enhancing a service with specific qualities to provide gameful experiences. The list below contains both systemic and experiential conditions the authors found necessary when defining games or gamification, each condition belonging to a specific level of abstraction:

Lastly, the author of a gamification framework known as Octalysis proposed the following definition for gamification: “the craft of deriving all the fun and engaging elements found in games and applying them to real-world or productive activities” (Chou, 2015). Furthermore, the author defines gamification as a type of design designated as “Human-Focused Design”, which optimizes human motivation in a system. However, “Function-Focused Design” focuses on optimizing system efficiency. This definition of gamification emphasizes fun and engagement factors.

Each of the analyzed definitions focuses on different aspects of gamification, although they all seem to have in common that it provides a game-like experience. In sum, gamification can augment user interactions (Deterding, 2015). Moreover, to produce gameful experiences, design elements that can be found within the game industry are used to motivate users to perform specific actions. These game design elements consist of every feature that is both common and impactful within the game context. For instance, the use of rewards is standard in most (if not all) designs of gamification due to its effect of motivating users to keep performing a requested action. However, the reward needs to be meaningful for the user in question.

The following are two examples of companies who have successfully deployed gamified services:

Not well-defined objectives are among the usual explanations for failure in gamification design (Mora, Riera, González, & Arnedo-Moreno, 2017). An inadequate understanding of what motivates target users can also cause some problems. Some companies failed to meet their business objectives, for instance:

In summary, many companies attempted to implement gamification on their services, with varied outcomes. In 2012, Gartner predicted that, by 2014, 80% of gamified applications would fail to meet business objectives due to poor design (Burke, 2014) and since then, there have been many attempts to mitigate the issue presented (Morschheuser, Hamari, Werder, & Abe, 2017; Morschheuser, Hassan, Werder, & Hamari, 2018; Walz & Deterding, 2015).

A study about the gamification effects on systems was performed to assess the overall value a gamified system can offer (Hamari, Koivisto, & Sarsa, 2014). This research was conducted around the definition proposed by Huotari & Hamari (2012) regarding gamification. Furthermore, this definition consists of a three-step process starting with the implemented motivational affordances causing psychological outcomes, which will, in turn, produce the desired behavioral outcomes. The results about gamification usefulness varied depending on the motivational affordances used and the expected psychological outcomes which would develop behavior changes on the target audience.

The study revealed that points, leaderboards, and badges were the most prominent types of motivational affordances used in gamified systems, as well as the prominence of behavioral analysis over psychological analysis about the effects of gamified applications on its respective user base. The overall result of the research conducted is that gamification does provide benefits, should it be implemented under the correct circumstances, two of the main factors to consider before adding a gamified application would be the role of the context to be gamified and the types of users who would engage with the application.

A recent study examined 40 frameworks (Mora et al., 2017). It is beyond the purpose of this chapter to perform such extensive analysis. This section introduces some frameworks widely used in gamification design. They are all broadly recognized, but they also have detailed descriptions and available support. Moreover, they do not only provide guidelines but align them to users and their possible motivations.

The Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics framework is not directly related to gamification, but the information it provides regarding game elements and strategies should not be neglected.

Octalysis

According to Yu-Kai Chou, who proposed Octalysis (Chou, 2015), a game’s purpose is only to please the individual playing it by appealing to several specific “Core Drives”, which, in turn, motivate them to continue playing (see Table 1). Yu-kai Chou defines “White Hat Gamification” and “Black Hat Gamification”, the former encompasses positive motivators, while the latter includes the negative motivators. However, Chou (2015) reassures that “Black Hat Gamification” is not necessarily bad since it can motivate people to take either beneficial or harmful actions.

The Octalysis framework is visually divided vertically, having the drives on the left associated with logic, calculations, and ownership, and on the right associated with creativity, self-expression, and social aspects.

Table 1. The Octalysis framework adapted by Chou (2015)

| Core Drive | Examples | Associated Side | Gamification Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epic Meaning and Calling | • Narrative • Elitism • Creationist • Destiny Child |

• Left Brain • Right Brain |

• White Hat |

| Development and Accomplishment | • Quest Lists • Progress Bar • Status Points • Boss Fights |

• Left Brain | • White Hat |

| Empowerment of Creativity and Feedback | • Milestone Unlocks • Instant Feedback • Boosters • Real-Time Control |

• Right Brain | • White Hat |

| Ownership and Possession | • Exchangeable Points • Virtual Goods • Collection Sets • Avatar |

• Left Brain | • Black Hat • White Hat |

| Social Influence and Relatedness | • Friending • Gifting • Mentorship • Brag Button |

• Right Brain | • Black Hat • White Hat |

| Scarcity and Impatience | • Prize Pacing • Countdown Timer • Appointment Dynamics • Options Pacing |

• Left Brain | • Black Hat |

| Unpredictability and Curiosity | • Random Rewards • Easter Egg • Sudden Rewards • Rolling Rewards |

• Right Brain | • Black Hat |

| Loss and Avoidance | • Progress Loss • Rightful Heritage • Status Quo Sloth • Visual Grave |

• Left Brain • Right Brain |

• Black Hat |

The following list contains detailed information about the 8 Core Drives:

The “Six steps to gamification” (Werbach & Hunter, 2012), or 6D Framework, is based on six different steps:

Related to the step “Describe your players”, it is relevant to know who the system’s users are, since what can motivate one user, may not motivate another, and if the developed motivators are not fit for the current user-base, the gamified system will fail. Thus, creating several different groups of users, and using various kinds of motivators, can be efficient in dealing with the issue. Furthermore, to assist with what may motivate specific player-bases, Werbach & Hunter (2012) refer to the taxonomy of player types introduced by Bartle (1996), consequently presenting the following player categories: achievers, explorers, socializers, and killers.

Achievers are interested in rewards such as badges, explorers look for new content to enjoy, socializers tend to engage with friends, and lastly, killers desire to overwhelm others. Each specific individual has elements of the previously mentioned archetypes. As such, it is essential not only to identify these archetypes within the player-base but also to have a system prepared for changes since the players may have a shift in their motivations over time.

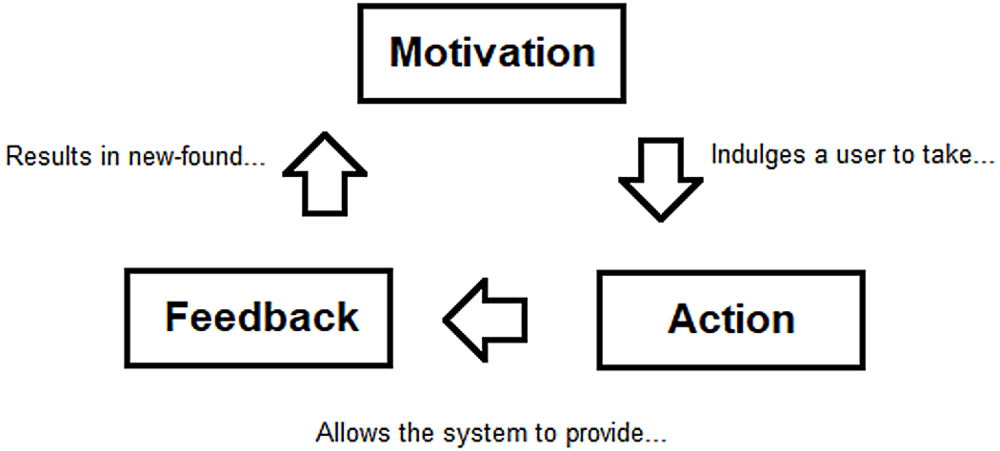

| Figure 1. Activity cycle adapted from Werbach & Hunter (2012) |

|---|

|

Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics

The Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics (MDA) framework is an approach to related to understanding games, instead of gamification, which attempts to connect game design with development, game criticism, and technical game research (Hunicke et al., 2004).

This framework is not directly related to gamification, but it is essential in the current context due to the information it provides regarding game design strategies, which in turn enhances the overall understanding of gamification strategies by breaking down the consumption of games and game design into concrete components.

A game is consumed like any other entertainment product, but its consumption is comparatively unpredictable. To better assist designers with design decisions regarding a specific game, this framework considers games as artifacts. Thus, indicating “that the content of a game is its behavior - not the media that streams out of it towards the player” (Hunicke et al., 2004).

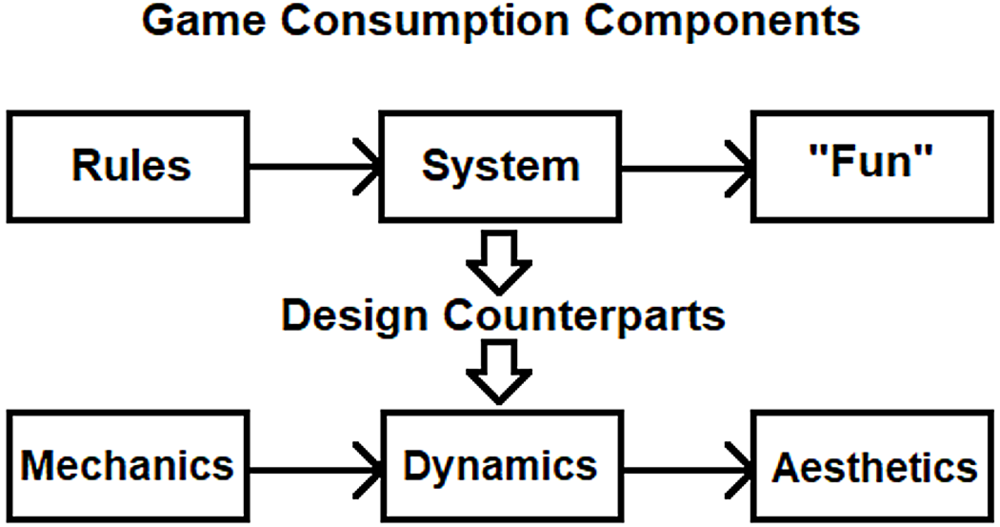

To clarify the consumption process of games, the MDA framework formalizes it through a sequence of distinct components as represented in Figure 2 as well as their respective design counterparts.

| Figure 2. Game consumption components and their respective design counterparts Adapted from Hunicke et al. (2004) |

|---|

|

The design components can be described by the following:

Problems With Current Frameworks

Deterding (2015) reviewed some of the current gamification frameworks (Burke, 2014; Kapp, 2012; Kumar, 2013; Paharia, 2013; Werbach & Hunter, 2012; Zichermann & Cunningham, 2011), analyzing specific characteristics. The following list consists of the common issues found in the study:

Mora et al. (2017) analyzed a wide array of gamification frameworks, categorizing each one of them (and their respective issues) regarding their main sectors of application: business, generic, health, and learning. The study revealed the most common context for gamification frameworks was the business environment, as well as the predominance of user-centered designs, along with the overall disregard of business-related issues, such as risk, feasibility, and investment. Deterding (2015) stated that the psychological factor is recognized in most frameworks, but the respective preferences of each user type are generally not considered. Further details regarding the frameworks reviewed can be consulted in both of the presented studies (Deterding, 2015; Mora et al., 2017).

Model-Driven Engineering is an approach that uses models as the main artifacts for the software development process (Brambilla, Cabot, & Wimmer, 2017). It avoids the implicit complexity of application development (Schmidt, 2006). A Domain-Specific Language facilitates the use of the concepts in question.

In this context, models implement, at least, two roles through abstraction:

Models additionally attend to different purposes when developing software through an MDE approach. They can be used for descriptive purposes, such as describing a system or a context. Models can also be used for prescriptive purposes, permitting the development of a method to study a problem, and lastly, to specify how the system should be implemented.

To follow the MDE approach, appropriate tools are necessary to define both models and transformations during the implementation phase. Suitable compilers or interpreters are also required to execute and produce the desired software artifacts. As MDE is based around models, the specification of the modeling language is realized through a model. This procedure is designated as metamodeling, and it can have different levels of abstraction. A meta-metamodel is the result of specifying a modeling language using a metamodel.

A DSL is a possible approach when it is required for a language to efficiently define a specific set of tasks (Gronback, 2009).

A DSL determines the base structure, behavior, and requirements related to a particular domain. Metamodels can be used to set relationships between concepts in a domain and to specify the key semantics/constraints related to each of these concepts. DSLs are typically used to simplify development processes, but they can also be used to validate what has been specified within the domain context. Once the design of the DSL is complete, code generators can be used to produce source code or other artifacts, such as model representations.

Figure 3 represents several significant steps when developing a gamification instance for a system. It contains both the traditional and the MDE approach. It is essential to recognize that the step “Gamification instance” (see Figure 3) is not final and that it is always necessary the assistance of an IT expert to link the generated gamification application with the system to be gamified as well as providing required increments. For instance, authentication services may be one of the increments to be considered. However, by having the gamification expert formalizing the gamification design through an MDE approach, the application’s code is directly connected to the model. Thus, there is no loss of information between the gamification expert and the IT professional in the implementation phase.

Solutions that use the MDE approach have emerged to ease the inclusion of game elements in non-game applications. Three solutions are described in detail in the following sections: GaML, MEdit4CEP, and Gamify. However, even though these solutions are intended to assist with the development of successful gamification strategies, they do not bypass the need to define concrete business objectives, nor they are means to disregard valuable information regarding the user base of the system to be gamified. Each of the solutions to be analyzed follows a similar design process to the MDE approach shown in Figure 3.

| Figure 3. Usual and MDE approach |

|---|

|

GaML is a “language for modeling gamification concepts” (Herzig, Jugel, Momm, Ameling, & Schill, 2013) with the primary objective of developing a readable language to non-technical gamification experts.

To develop the intended language, the developers of GaML structured gamification concepts using the taxonomy of game design elements provided by Deterding et al. (2011), classifying the concepts as game design elements with five different levels of abstraction, as previously described. The language itself focuses only on the first two levels (what “visual concepts exist and how these elements relate to each other” (Herzig et al., 2013)), while the other levels are related to the creation of a compelling gamification design, which is associated with the conceptualization of a specific design and not with the language.

For the first level of abstraction (game design patterns), basic visual gamification elements are pointed out, as well as possible synonyms in the specific context instance and its subtypes.

The second level of abstraction in the taxonomy of game design elements, defined as “Game Design patterns and mechanics” (Deterding et al., 2011), determines the gameplay factors of gamification, for instance, rules and conditions, since these elements insert logic into the gamification context. Further information about the approach adopted and the game design elements chosen for each level of abstraction can be consulted on the paper in question (Herzig et al., 2013).

The next step in developing GaML was the language specification, which was distributed into the three following phases:

In short, GaML assists with both the conceptualization and implementation of gamification. “Stop Smoking” (Matallaoui, Herzig, & Zarnekow, 2015) is a serious game developed in the Unity Engine with an achievement system implemented by GaML. Its users are rewarded with badges by performing the system's designated actions. Further information regarding the case studies developed to showcase the language in question can be found in both of the examined papers (Herzig et al., 2013; Matallaoui et al., 2015). Even though one of the primary objectives was to create a language that could be partially writable by domain experts, it was stated that domain experts could not develop a model with complicated gamification strategies.

MEdit4CEP-Gam

MEdit4CEP-Gam (Calderón, Boubeta-Puig, & Ruiz, 2018) is a model-driven solution that can also be used by non-technical gamification experts, but unlike GaML (Herzig et al., 2013), graphical DSLs are used to allow gamification design graphically. This approach can successfully hide the implementation details when defining the desired model, which will later be transformed into the code to be executed by their system, designed with an Event-Driven Service-Oriented Architecture.

The procedure of MEdit4CEP-Gam approach can be described by the following:

To define the domain-specific elements of the gamification context, the developers of MEdit3CEP (Calderón et al., 2018) used the first level of abstraction in the taxonomy of game design elements (Deterding et al., 2011) and proposed the definition of its domain to be separated by the components category and the mechanics category. The following list contains a small description of each category and its elements:

With these categories and elements in mind, Calderón et al. (2018) proceeded to develop the metamodel through the usage of software such as the Eclipse Modeling Framework (EMF). The finished result of the metamodel in question is an extended version of the Model4CEP metamodel with both the gamification elements previously described and the components related to the CEP engine.

More information about how the gamification components interact with the CEP setup, as well as the evaluation involving the user’s experience regarding the modeling editor, can be consulted in the article by Calderón et al. (2018).

This solution provides a reliable tool for conceptualizing and implementing gamification while being user-friendly for domain-experts. Moreover, due to the usage of an MDE approach, it can transform the models developed by domain-experts into code, to later be monitored and controlled by their event-driven service-oriented architecture system. But, due to it having such a high-level graphical design, it fails to assist with the development of intricate gamification strategies.

Gamify

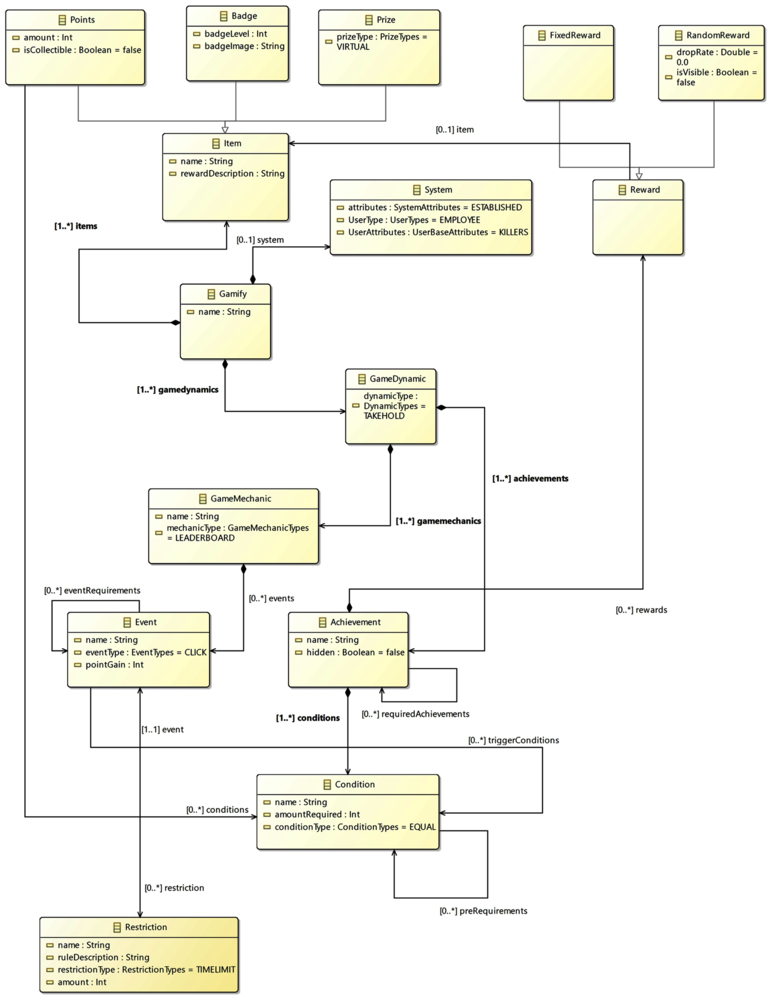

Gamify (Aguiar, 2019) provides a textual-based DSL like GaML, but it can also generate guidelines depending on the domain expert's choices while designing the gamification strategies. Figure 4 represents the base metamodel, which includes various entities:

| Figure 4. Gamify metamodel |

|---|

|

| Figure 5. Other gamify concepts |

|---|

|

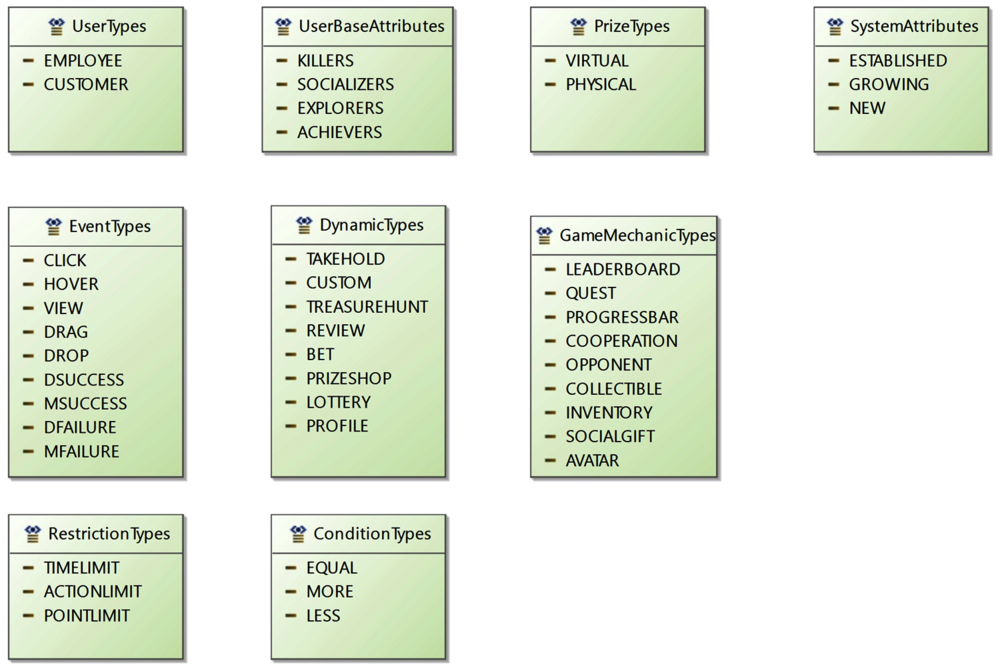

General details about the various types and presets available to the user when designing a gamification strategy are the following (see Figure 5):

Tables 2 and 3 contain information about each of the elements that reside in the metamodel. However, Table 4 provides information about the various reward strategies that the metamodel is prepared to replicate. The strategies in question are based on the Octalysis Framework (Chou, 2015).

Table 2. Basic visual game mechanics

| Game Design Element | Synonyms | Subtypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| System | • Service • Application |

- | (Chou, 2015; Werbach & Hunter, 2012) |

| Event | • Dynamic Event • Mechanic Event • User Action |

- | (Hunicke et al., 2004) |

| Condition | • Requirement | - | (Chou, 2015; Werbach & Hunter, 2012) |

| Restriction | • Regulation • Limit |

- | (Deterding et al., 2011; Hunicke et al., 2004) |

| Item | • Goods • Collectible • Currency |

• Badge • Points • Prize |

(Chou, 2015; Deterding et al., 2011) |

| Reward | Earned: • Goods • Collectible • Currency |

• Random Reward • Fixed Reward |

(Chou, 2015; Deterding et al., 2011) |

Table 3. Aggregated visual game mechanics

| Game Design Element | Synonyms | Aggregates | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gamify | • Context | • Item • System • GameDynamic |

- |

| GameDynamic | - | • GameMechanic • Achievement |

(Hunicke et al., 2004) |

| GameMechanic | - | • Event • Restriction |

(Hunicke et al., 2004) |

| Achievement | • Quest • Mission |

• Condition • Reward |

(Chou, 2015) |

Table 4. Gamification reward strategies

| Strategies | Core Drives | Experiential Effects | Examples | Situations that make rewards visible | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Action Rewards | 2;4;6 | • Increases engagement • Builds loyalty |

• Virtual or physical goods • Points • Collectibles • Currency |

System notifies the user about the actions required to get a specific reward. | (1) |

| Random Rewards | 2;4;6;7 | • Builds loyalty • Can enhance engagement of veteran users |

Randomized: • Virtual or physical goods • Collectibles • Amount of currency |

After successfully overcoming a previously set challenge or spending currency on a box of random goods. | (2) |

| Sudden Rewards | 1;3;4;5;7 | • Augments socialization within user base • Increases engagement |

• Virtual or physical goods • Points • Collectibles • Currency |

Completing a hidden set of actions, or by finding an Easter Egg. | (3) |

| Rolling Rewards | 1;2;4;5;6;7 | • Can enhance user engagement substantially | All types of rewards are eligible, from minimum to significant value. | Interacting with a lottery-like mechanic. | (4) |

| Social Treasure | 3;4;5;6 | • Augments socialization | Points, currency, collectibles which cannot be obtained by other means. | Sending in-game gifts to friends; Inviting friends to join the platform. | (5) |

| Prize Pacing | 2;4;5;6;7;8 | • Augments engagement | Collection of categorized shards, which turn into specific rewards once all shards are collected. |

System informs the user about the obtainable reward after collecting a full set of shards. | (6) |

The following list contains information related to the column “Major Findings” of Table 4:

When designing the reward strategies for a gamification design, the variables “requiredAchievements” (Achievement) and “preRequirements” (Condition) can be used to either create a sequence of achievements (e.g., To obtain a level 2 badge, it is necessary to obtain the level 1 badge), each having their specific reward, or to create a complex condition for a particular achievement, effectively developing a challenge (e.g., a user needs to succeed on a set dynamic 10 times while using less than 10 total actions).

This current solution aims to succeed in being user-friendly for domain-experts, even when developing complex gamification strategies, due to the use of guidelines that adapt to the domain expert's choices. However, the solution currently lacks in available game dynamics, game mechanics and events, possibly hindering specific designs.

Solutions Comparison

This section focuses on relating various details of the analyzed solutions. Table 5 contains several benefits from each of the solutions examined. Benefits implicitly provided through the MDE approach are not included.

Table 5. Solutions specifics

| Solution | DSL Type | Benefits | Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| GaML | • Textual | • Provides a mature achievement-based system | • Readable but only partially writable by domain experts |

| MEdit4CEP | • Graphical | • User-friendly • Controls and monitors gamification strategies through the CEP engine |

• Does not allow complex gamification strategies |

| Gamify | • Textual | • Provides design guidelines • Allows complex gamification strategies • User-friendly • Can generate text |

• Limited number of available mechanics, and dynamics |

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

MDE is an approach to software development that is especially useful when the problem in question envelops complex domain concepts (Schmidt, 2006). Through the usage of the appropriate tools, DSLs, transformations, and code generation, MDE can effectively address platform complexity.

Gamification is a moderately new concept, and thus the appearance of new strategies for gamified applications and new tools to implement them are bound to happen in the future.

Though flawed, each of the proposed solutions is in the right direction of addressing the problem of poor gamification design. And this is due to the implicit guidance provided by these solutions to domain-experts whenever they design new gamification strategies. The added assistance provided results in the avoidance of common design pitfalls. Even so, domain-experts will require knowledge about developing appropriate gamification strategies before utilizing any of the previously analyzed solutions, though both MEdit4CEP-Gam and Gamify attempt to assist with the strategy design. The studied frameworks provide invaluable information about the subject. Even though the Octalysis Framework and the Six Steps to Gamification were intended to assist with gamification, the MDA framework presents general information about games that can augment a domain expert's overall understanding of game elements. Nonetheless, these gamification frameworks are not flawless. Although they supply general information about how to implement gamification, they do not assist domain-experts with specific situations. The following list of actions consist of suggestions to mitigate some of the issues previously discussed regarding the studied frameworks:

MDE is a suitable approach when dealing with several problems, including the introduction to gamification and the model-code gap (Fairbanks, 2010), ultimately simplifying the development process and preventing inadvertent introduction of errors. In this context, MDE can also encourage Agile software development since, should the need arise to change or add entities to the gamification strategy, it is possible to quickly implement these changes to the respective DSL resulting in newly generated code that can be easily integrated into the desired system. By performing this process, both the model representing the strategy adopted remains updated, as well as its corresponding generated code.

Regardless of how gamification design is achieved, a formal gathering of user necessities is imperative to avoid problems that would otherwise remain undetected. Additionally, no gamification approach will succeed without the proper identification of the objectives, or without knowledge about the user base in question.

AguiarP. (2019, March 22). Gamify. Retrieved from: https://bitbucket.org/1140459/gamify/src/master/

Bartle, R. (1996). Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit MUDs. Journal of MUD Research , 1(1), 19. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/directory/publications

Brambilla, M., Cabot, J., & Wimmer, M. (2017). Model-Driven Software Engineering in Practice (2nd ed.). San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

Brathwaite, B., & Schreiber, I. (2008). Challenges for Game Designers (1st ed.). Rockland, MA: Charles River Media, Inc.

Burke, B. (2014). Gamify: How Gamification Motivates People to Do Extraordinary Things . Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Calderón, A., Boubeta-Puig, J., & Ruiz, M. (2018). MEdit4CEP-Gam: A model-driven approach for user-friendly gamification design, monitoring and code generation in CEP-based systems. Information and Software Technology , 95, 238–264. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2017.11.009

Chou, Y. (2015). Actionable gamification: Beyond points, badges, and leaderboards . Fremont, CA: Octalysis Media.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation, 85–107. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0006

Deterding, S. (2015). The Lens of Intrinsic Skill Atoms: A Method for Gameful Design. Human-Computer Interaction , 30(3-4), 294–335. doi:10.1080/07370024.2014.993471

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011, September 28). From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness. Defining Gamification, 11, 9–15.

Djaouti, D., Alvarez, J., Jessel, J.-P., & Rampnoux, O. (2011). Origins of serious games . In Serious games and edutainment applications (pp. 25–43). New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2161-9_3

Fairbanks, G. (2010). Just enough software architecture: A risk-driven approach . Boulder, CO: Marshall & Brainerd.

Gronback, R. C. (2009). Eclipse modeling project: A domain-specific language (DSL) toolkit . London, UK: Pearson Education.

Hamari, J., & Koivisto, J. (2015). Why do people use gamification services? International Journal of Information Management , 35(4), 419–431. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.04.006

HamariJ.KoivistoJ.SarsaH. (2014). Does Gamification Work? - A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 14, 3025–3034. 10.1109/HICSS.2014.377

Herzig, P., Jugel, K., Momm, C., Ameling, M., & Schill, A. (2013). GaML-A modeling language for gamification. 2013 IEEE/ACM 6th International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing, 494–499.

HunickeR.LeblancM.ZubekR. (2004). MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research. AAAI Workshop - Technical Report, 1.

HuotariK.HamariJ. (2012). Defining gamification: A service marketing perspective. In Proceeding of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Conference, (pp. 17–22). New York, NY: ACM. 10.1145/2393132.2393137

Huynh, D., Zuo, L., & Iida, H. (2018). An Assessment of Game Elements in Language-Learning Platform Duolingo. In 2018 4th International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCOINS), (pp. 1–4). Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction . San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

KumarJ. (2013). Gamification at work: Designing engaging business software. In International Conference of Design, User Experience, and Usability, (pp. 528–537). New York, NY: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-642-39241-2_58

Land, S. K., & Wilson, B. (2006). Using IEEE standards to support America’s Army gaming development. Computer , 39(11), 105–107. doi:10.1109/MC.2006.405

Matallaoui, A., Herzig, P., & Zarnekow, R. (2015). Model-Driven Serious Game Development Integration of the Gamification Modeling Language GaML with Unity. 2015 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 643–651. 10.1109/HICSS.2015.84

Mora, A., Riera, D., González, C., & Arnedo-Moreno, J. (2017). Gamification: A systematic review of design frameworks. Journal of Computing in Higher Education , 29(3), 516–548. doi:10.1007/s12528-017-9150-4

MorschheuserB.HamariJ.WerderK.AbeJ. (2017). How to gamify? A method for designing gamification. Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2017. 10.24251/HICSS.2017.155

Morschheuser, B., Hassan, L., Werder, K., & Hamari, J. (2018). How to design gamification? A method for engineering gamified software. Information and Software Technology , 95, 219–237. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2017.10.015

Paharia, R. (2013). Loyalty 3.0: How to revolutionize customer and employee engagement with big data and gamification . New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional.

Robson, K., Plangger, K., Kietzmann, J. H., McCarthy, I., & Pitt, L. (2016). Game on: Engaging customers and employees through gamification. Business Horizons , 59(1), 29–36. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2015.08.002

Schmidt, D. C. (2006). Model-Driven Engineering. IEEE Computer, 39(2), 9. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/

Walz, S. P., & Deterding, S. (2015). The gameful world: Approaches, issues, applications . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9788.001.0001

Werbach, K., & Hunter, D. (2012). For the Win: How Game Thinking can Revolutionize your Business . Philadelphia, PA: Wharton School Press.

Zichermann, G., & Cunningham, C. (2011). Gamification by design: Implementing game mechanics in web and mobile apps. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Domain-Specific Language (DSL): A custom computer language specialized to a particular application domain.

Gamification: Concept with different definitions, but it is generally known as the use of game design elements in non-game contexts.

Gamify: An MDE solution based on a textual DSL that provides both gamification strategy guidelines, as well as language-related guidelines to assist domain experts in developing successful gamification strategies.

GaML: MDE solution based on a textual DSL that provides a structure for modeling gamification concepts.

Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics (MDA): A framework related to game development, seeking to combine game design with development, game critique, and technical game research to achieve a better general understanding of games.

MEdit4CEP-Gam: MDE solution with a graphical DSL that is appropriate for non-technical gamification experts to formalize their gamification designs.

Model-Driven Engineering (MDE): An approach that uses models as the main artifacts for the software development process. Furthermore, it relies on both code transformations and code generation to successfully produce software.