[Time—Shortly after the revival of learning in Europe]

Text and publication

First publ. M & W, 10 Nov. 1855; repr. 1863, 18652, 1868, 1872, 1888. Our text is 1855. B.’s fair copy of ll. 137–48 (the last twelve lines of the poem) is in Berg. It is written on the first leaf of a four-sided sheet of notepaper, with B.’s crest; to the right of the crest is the heading ‘In memoriam | Johannis Conington’; at the bottom is a note: ‘(From “A Grammarian’s Funeral.”)’, followed by B.’s signature and the date, 1 Nov. 1869 (shortly after Conington’s funeral, according to the Berg catalogue entry). Conington (1825–1869) was an Oxford classical scholar whom B. may have met through his friendship with Benjamin Jowett, the Master of Balliol College; B. received an honorary degree from Oxford in 1868. Collections (E153) mistakenly records the extract as beginning at l. 135. B. probably copied the lines from 1863, not its revised reissue 1865: see ll. 137n., 143n.

Composition

DeVane (Handbook, 270) speculates that the poem may be the product of the Brownings’ period of residence in Rome during the winter of 1853–54; it is not, however, one of the poems identified by Sharp as belonging to this period.

Sources and contexts

(i) Time and place

The subtitle refers to ‘the revival of learning’, a phrase widely used in the early nineteenth century, but not with any exact chronological boundaries; see for instance Peacock’s Four Ages of Poetry (1820) and Shelley’s ‘Essay on the literature, the arts, and the manners of the Athenians’, publ. 1840. In James Montgomery’s A View of Modern English Literature (1843) the ‘revival of classic learning’ is linked to phenomena of the late 15th and early 16th centuries (the Reformation, the discovery of the New World and the invention of the printing press) as one of the harbingers of what later came to be called the Renaissance; on the nineteenth-century elaboration of this concept see headnote to Andrea (pp. 386–7). B. had described an earlier phase of this ‘revival’ in Sordello, that of the early 13th century (i 569–83, I 434), but the period of the Grammarian’s activity seems to belong to the 14th or 15th century, when the systematic study of Greek was taking hold in Italy and Germany. The nationality of the Grammarian is left deliberately unclear, as is the location of the city where he is buried, other than that it is in ‘Europe’. The hilltop location fits Tuscany or Lombardy, but might equally refer to the Rhineland. The contrast in the opening lines between the ‘common crofts, the vulgar thorpes’ and the ‘tall mountain, citied to the top’ does, however, suggest a positive revaluation of the dominance of mountain over plain which B. associates with Italy: in Sordello Ecelin’s tyranny is marked by castle-building in the mountains (i 257–68, I 412), and in England in Italy the mountains themselves are symbols of oppression (ll. 181–96, p. 264).

(ii) The character of the Grammarian

The jealousy, small-mindedness and ill-health of grammarians seem to have been proverbial; in Praise of Folly (1509; transl. John Wilson, 1668), Erasmus uses grammarians to illustrate the follies of the learned:

I knew in my time … one of many Arts, a Grecian, a Latinist, a Mathematician, a Philosopher, a Physitian … a Man master of ’em all, and sixty years of age, who laying by all the rest, perplext and tormented himself for above twenty years, in the study of Grammar, fully reckoning himself a Prince, if he might but live so long, till he could certainly determine, how the Eight parts of Speech were to be distinguisht, which none of the Greeks or Latines, had yet fully clear’d; as if it were a matter to be decided by the Sword, if a man made an Adverb of a Conjunction; and for this cause is it, that we have as many Grammars, as Grammarians; nay more, forasmuch as my friend Aldus, has giv’n us above five, not passing by any kind of Grammar, how barbarously, or tediously soever compil’d, which he has not turn’d over, and examin’d; envying every mans [sic] attempts in this kind, how foolish so ever, and desperately concern’d, for fear another should forestal him of his glory, and the labours of so many years perish … they that write learnedly, to the understanding of a few Scholers … seem to me, rather to be pitied, than happy, as persons that are ever tormenting themselves; Adding, Changing, Putting in, Blotting out, Revising, Reprinting, showing ’t to friends … and nine years in correcting, yet never fully satisfied; at so great a rate, do they purchase this vain reward, to wit Praise, and that too, of a very few, with so many watchings, so much sweat, so much vexation, and loss of sleep, the most pretious of all things: Add to this, the waste of health, spoil of complexion, weakness of eyes, or rather blindness, poverty, envie, abstinence from pleasure, over-hasty Old-age, untimely death, and the like; So highly does this Wise man value the approbation of one or two blear-ey’d fellows[.] (pp. 88–91)

Various suggestions have been made about the identity of the poem’s ‘grammarian’, including Erasmus’s contemporary Thomas Linacre (1460–1524) and Isaac Casaubon (1559–1614), but as DeVane puts it ‘[the] probability is that B. had several scholars of the early Renaissance in mind, and drew a composite figure’ (Handbook 270). James F. Loucks (‘Browning’s Grammarian and “Herr Buttmann”, SBC ii.3 [1974] 79–83) has noted some similarities between the poem’s portrait and the description of the German grammarian Philip Charles Buttman (1764–1829) in Edward Robinson’s 1839 translation of his work. Buttman was, according to Robinson, ‘embittered by severe physical suffering’ during his final years:

His body was racked by rheumatic affections [sic], which deprived him in great measure of the use of his limbs, and finally terminated his days, Jan. 21, 1829. For several preceding winters he had been confined to his house. The writer of these lines had the pleasure of an interview with him about a year before his death. He was seated before a table in a large armed chair, bolstered up with cushions, and with his feet on pillows; before him was a book, the leaves of which his swollen and torpid hands were just able to turn over; while a member of his family acted as amanuensis. That book was his earliest work, the intermediate Grammar.

(cited Loucks, pp. 81–2)

As Loucks points out, B. mentions Buttman by name in the late poem Development (Asolando, 1889), and cites him as an authority when defending his account of the ‘doctrine of the enclitic De’ (see ll. 131–2n.). B. was questioned on this matter by Tennyson, as a letter of 2 July 1863 (first publ. by Christopher Ricks, TLS, 3 June 1965, p. 464) makes clear:

My dear Tennyson,

There are tritons among minnows, even—and so I wanted the grammarian ‘dead from the waist down’—(or ‘feeling middling,’ as you said last night)— to spend his last breath on the biggest of the littlenesses: such an one is the ‘enclitic δε,’ the ‘inseparable,’ just because it may be confounded with δέ , ‘but’, which keeps its accent … See Buttman on these points. It was just this pinpoint of a puzzle that gave ‘de’ its worth rather than the heaps of obvious rhymes to ‘he’—in all the oblique cases, for instance, of personal pronouns … to which I beg you to add, in a guffaw, ‘he-he-he!’ Only, you would have it!

Erasmus’s view of the grammarian is echoed by EBB. in The Greek Christian Poets (1842; rpt. Poetical Works [1907] 613):

How many are there from Psellus to Bayle, bound hand and foot intellectually with the rolls of their own papyrus—men whose erudition has grown stronger than their souls! How many whom we would gladly see washed in the clean waters of a little ignorance, and take our own part in their refreshment! Not that knowledge is bad, but that wisdom is better; and that it is better and wiser in the sight of the angels of knowledge to think out one true thought with a thrush’s song and a green light for all lexicon (or to think it without the light and without the song—because truth is beautiful, where they are not seen or heard)—than to mummy our benumbed soul with the circumvolutions of twenty thousand books. And so Michael Psellus was a learned man.

Similarly, Emerson in ‘Intellect’ (Essays [1841] 187–8) argues that when a man ‘[fastens] his attention on a single aspect of truth, and [applies] himself to that alone for a long time, the truth becomes distorted and not itself, but falsehood … How wearisome the grammarian, the phrenologist, the political or religious fanatic, or indeed any possessed mortal, whose balance is lost by the exaggeration of a single topic. It is incipient insanity’.

Form and metre

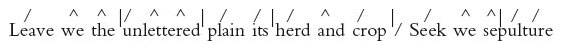

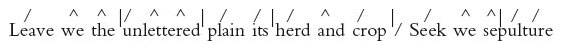

DeVane (Handbook 270) describes the poem as ‘alternating five-measure iambic and two-measure dactylic’. This is clearly wrong: each line of the poem begins with a stressed syllable, and the shorter lines always contain five syllables rather than six. The metre can be better understood as an imitation of the classical hexameter, divided into two parts (eg ll. 21–2):

Cp. the transformation of short lines into long ones in the completed Saul (see headnote, III 491), and in the versions of Cristina and England in Italy published in the 1872 Selections, for which see I 774 and II 341 respectively. The dactylic quality of the shorter lines is more immediately apparent because a dactyl is obligatory in the fifth foot of a hexameter, but can be substituted by a spondee (or more usually in English a trochee) in any of the other feet. In addition, the metre is emphasized by the use of alliteration as a marker of accent in the shorter lines. B. makes one significant departure from the usual accentual hexameter; the line break after the fourth foot leads him to make it a ‘cretic’ (/ ^ /) rather than a dactyl. This imparts an awkward rising intonation to the end of the long lines which may be intended to imitate the mourners’ laborious procession up the mountain.

The use of an English equivalent to the metre of classical Greek poetry has an obvious relevance to the subject of the poem, a point reinforced by the use of terms such as ‘measures’ and ‘feet’ (l. 39) and ‘accents’ (l. 54) even where the primary sense is not that of metrical language. The question of the English hexameter was, moreover, topical during the late 1840s and early 1850s. Some of B.’s contemporaries, most notably Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (in Evangeline, 1847) and Arthur Hugh Clough (in The Bothie of Toper-na-Fuosich, 1848) wrote narrative poems in English hexameters, in part to refute the idea that the metre was not suited to the English language. The Brownings read Clough’s poem on first publication, with EBB. noting in a letter of 1 Dec. 1849 to Mary Russell Mitford that the poem is ‘written in loose & more-than-need-be unmusical hexa-meters, but full of vigour & freshness, & with passages & indeed whole scenes of great beauty & eloquence’ (EBB to MRM iii 286). For the background to the hexameter debate, see J. Phelan, ‘Radical Metre: The English Hexameter in Clough’s Bothie of Toper-na-Fuosich’, RES n.s. 1 (1999) 166–87.

Criticism and parallels in B.

The main precursor for the Grammarian in B.’s work is ‘Sibrandus Schafnaburgensis’, the pedant who gives his name to the second section of Garden Fancies (see p. 216). As Oxford suggests, EBB.’s admiration for the poem was expressed in a phrase which may have stuck in B.’s memory: ‘I like your burial of the pedant so much!’ (21 July 1845, Correspondence x 315). Debate on the poem has centred on whether or not it is a satire on the Grammarian. Is he a hero of obscure but valuable labour, or someone who has lost sight of the ends of life? There are a number of poems in which B. seems to criticize the attitude represented by the Grammarian; see Martin J. Svaglic, VP v (1967) 93–104, in which contrasts with Paracelsus are highlighted. Festus warns Paracelsus of the consequences of making the acquisition of knowledge the main aim of human life: ‘How can that course be safe which from the first / Produces carelessness to human love?’ (i 626–7, I 142); and Paracelsus himself recognizes that ‘men have oft grown old among their books / And died, case-harden’d in their ignorance, / Whose careless youth had promised what long years / Of unremitted labour ne’er perform’d’ (i 757–60, I 147). Svaglic also notes the relevance of a passage in Cleon (ll. 225–50, pp. 579–80); and it might be added that the Grammarian’s painful and laborious old age contrasts with the joyful old age depicted in some of B.’s other poems, most notably Rabbi Ben Ezra (p. 649).

Another perennial question examined in this poem concerns the relation between this life and the next. The Grammarian’s attitude derives from his certainty that the ‘heavenly period’ will ‘[perfect] the earthen’ (ll. 103–4); cp. the choice of the speaker in ED, who makes the opposite decision to ignore the possibility of the life to come and focus exclusively on this life (III 123). In this sense the Grammarian’s ‘sacred thirst’ for knowledge (l. 95) makes him into a kind of holy fool, since although he is searching for human wisdom he is doing so in a way which points beyond ‘the world’ (l. 121), in conformity with, e.g., 1 Corinthians iii 18–19: ‘If any man among you seemeth to be wise in this world, let him become a fool, that he may be wise. For the wisdom of this world is foolishness with God.’ B. himself suggests this in a letter to James Kenward of 11 March 1867 in which he praises the ‘self-denying zeal’ of ‘your Ap Ithel’, adding that ‘Purely disinterested scholarship always seemed to me to have far more important bearings, moral and intellectual, than are commonly recognized’ (Checklist 67:33); see also Sordello iv 573–89n. (I 628). The balance between ‘The petty Done [and] the Undone vast’, and between ‘bliss here’ and ‘life beyond’ is the central theme of Last Ride Together (III 291), where, however, the lover fantasizes that heaven may lie not in a compensatory future but in infinite prolongation of the present moment.

Let us begin and carry up this corpse,

Singing together.

Leave we the common crofts, the vulgar thorpes,

Each in its tether

5 Sleeping safe on the bosom of the plain,

Cared-for till cock-crow.

Look out if yonder’s not the day again

Rimming the rock-row!

That’s the appropriate country—there, man’s thought,

10 Rarer, intenser,

Self-gathered for an outbreak, as it ought,

Chafes in the censer!

Leave we the unlettered plain its herd and crop;

Seek we sepulture

15 On a tall mountain, citied to the top,

All the peaks soar, but one the rest excels;

Clouds overcome it;

No, yonder sparkle is the citadel’s

20 Circling its summit!

Thither our path lies—wind we up the heights—

Wait ye the warning?

Our low life was the level’s and the night’s;

He’s for the morning!

25 Step to a tune, square chests, erect the head,

’Ware the beholders!

This is our master, famous, calm, and dead,

Borne on our shoulders.

Sleep, crop and herd! sleep, darkling thorpe and croft,

30 Safe from the weather!

He, whom we convey to his grave aloft,

Singing together,

He was a man born with thy face and throat,

Lyric Apollo!

35 Long he lived nameless: how should spring take note

Winter would follow?

Till lo, the little touch, and youth was gone!

Moaned he, “New measures, other feet anon!

40 My dance is finished?”

No, that’s the world’s way! (keep the mountain-side,

Make for the city.)

He knew the signal, and stepped on with pride

Over men’s pity;

45 Left play for work, and grappled with the world

Bent on escaping:

“What’s in the scroll,” quoth he, “thou keepest furled?

Shew me their shaping,

Theirs, who most studied man, the bard and sage,—

50 Give!”—So he gowned him,

Straight got by heart that book to its last page:

Learned, we found him!

Yea, but we found him bald too—eyes like lead,

Accents uncertain:

55 “Time to taste life,” another would have said,

“Up with the curtain!”

This man said rather, “Actual life comes next?

Patience a moment!

Grant I have mastered learning’s crabbed text,

60 Still, there’s the comment.

Let me know all. Prate not of most or least,

Painful or easy:

Even to the crumbs I’d fain eat up the feast,

Ay, nor feel queasy!”

65 Oh, such a life as he resolved to live,

When he had learned it,

When he had gathered all books had to give;

Sooner, he spurned it!

Image the whole, then execute the parts—

70 Fancy the fabric

Quite, ere you build, ere steel strike fire from quartz,

Ere mortar dab brick!

(Here’s the town-gate reached: there’s the market-place

Gaping before us.)

75 Yea, this in him was the peculiar grace

(Hearten our chorus)

Still before living he’d learn how to live—

No end to learning.

Earn the means first—God surely will contrive

Others mistrust and say—“But time escapes,—

Live now or never!”

He said, “What’s Time? leave Now for dogs and apes!

Man has For ever.”

85 Back to his book then: deeper dropped his head;

Calculus racked him:

Leaden before, his eyes grew dross of lead;

Tussis attacked him.

“Now, Master, take a little rest”—not he!

90 (Caution redoubled!

Step two a-breast, the way winds narrowly.)

Not a whit troubled,

Back to his studies, fresher than at first,

Fierce as a dragon

95 He, (soul-hydroptic with a sacred thirst)

Oh, if we draw a circle premature,

Heedless of far gain,

Greedy for quick returns of profit, sure,

100 Bad is our bargain!

Was it not great? did not he throw on God,

(He loves the burthen)—

God’s task to make the heavenly period

Perfect the earthen?

105 Did not he magnify the mind, shew clear

Just what it all meant?

He would not discount life, as fools do here,

Paid by instalment!

He ventured neck or nothing—heaven’s success

110 Found, or earth’s failure:

“Wilt thou trust death or not?” he answered “Yes.

Hence with life’s pale lure!”

That low man seeks a little thing to do,

Sees it and does it:

115 This high man, with a great thing to pursue,

Dies ere he knows it.

That low man goes on adding one to one,

His hundred’s soon hit:

This high man, aiming at a million,

120 Misses an unit.

That, has the world here—should he need the next,

Let the world mind him!

This, throws himself on God, and unperplext

Seeking shall find Him.

125 So, with the throttling hands of Death at strife,

Ground he at grammar;

Still, thro’ the rattle, parts of speech were rife.

While he could stammer

He settled Hoti’s business—let it be!—

130 Properly based Oun—

Gave us the doctrine of the enclitic De,

Well, here’s the platform, here’s the proper place.

Hail to your purlieus

135 All ye highfliers of the feathered race,

Swallows and curlews!

Here’s the top-peak! the multitude below

Live, for they can there.

This man decided not to Live but Know—

140 Bury this man there?

Here—here’s his place, where meteors shoot, clouds form,

Lightnings are loosened,

Stars come and go! let joy break with the storm—

Peace let the dew send!

145 Lofty designs must close in like effects:

Loftily lying,

Leave him—still loftier than the world suspects,

Living and dying.

![]()

Title and subtitle.] A Grammarian’s Funeral, | shortly after the revival of learning in Europe. (1865–88). On the time and place of the poem, see above.

1–2. The poem is either a collective chant by the students, or the utterance of one of them speaking on behalf of all.

3. crofts: a croft is ‘[a] little close joining to a house that is used for corn or pasture’ ( J.). thorpes: J. lists various spellings (although not this one), and glosses as ‘a village’. B.’s spelling occurs in a footnote to Thomas Warton’s summary of Lydgate’s Storie of Thebes (1561); see The History of English Poetry (1774–81) ii 74.

5. on the bosom] i’ the bosom (1872).

7. yonder’s not the day] yonder be not day (1863–88).

8. Rimming: bordering; OED cites Tennyson, ‘The Gardener’s Daughter’ (1842) 177: ‘A length of bright horizon rimm’d the dark’. the rock-row! the line of mountain peaks in the distance.

9–12. man’s thought … censer: ‘Thought requires concentration, when it is enclosed in the brain, like incense in a censer; but as it takes fire, it must break out (be expressed) in words’ (Turner 381).

12. the censer: ‘The pan or vessel in which incense is burned’ ( J.)

13–16. A. D. Nuttall suggests that the elevated burial place to which the ‘grammarian’ is taken ‘entails a deft allusion to humanist values. Lucan’s words Caelo tegitur qui non habet urnam, “He is covered by the sky, who has no funeral urn” (De Bello Civili, vii 819) was the favourite proverb of humanist [Sir Thomas] More’s traveller, Hythloday’ (‘Browning’s Grammarian: Accents Uncertain?’, Essays in Criticism li [2001] 88).

14. sepulture: ‘Interment; burial’ ( J.).

16. culture: punning on the etymology of the word: the students leave the ‘herd’ on the ‘unlettered plain’ behind in their search for intellectual ‘culture’.

19. No, yonder: contradicting the first impression that the clouds ‘overcome’ the summit of the mountain (and so obscure the citadel). citadel’s: the fortress which crowns the city, as the city the mountain: the highest and innermost structure.

22. ‘Are you waiting for the signal?’ Cp. Robert Southey, A Vision of Judgement (1821): ‘Thus as I stood, the bell which awhile from its warning had rested, / Sent forth its note again, toll, toll, through the silence of evening’ (i 22–3).

25. the head] each head (1865–88).

26. ’Ware: ‘Be aware of ’.

33–4. Apollo is the god both of male beauty and of poetry: the Grammarian in his youth possesses both physical beauty (‘face’) and poetic power (‘throat’ is itself a poeticism for ‘voice’). In Sordello Apollo is the type of perfection in life and art, the ‘antique bliss’ that Sordello covets but cannot in fact attain: see i 893–7 (I 454).

35–6. Inverting the sequence in the last line of Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind: ‘If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?’

35. nameless: unknown to the wider world.

38–40. ‘When he found himself cramped and diminished, did he accept that his youth had gone and that he had to make way for others?’

39. measures … feet: the primary sense refers to the ‘dance’ of life, but there is a ‘submerged’ allusion to the poem’s own prosody: see headnote. anon! soon.

47. scroll: a roll of paper or parchment, often associated with sacred texts: cp. Revelation vi 14: ‘And the heaven departed as a scroll when it is rolled together; and every mountain and island were moved out of their places.’ Nuttall (see ll. 13–16n.) suggests both Dickens’s A Christmas Carol and The Merchant of Venice, II vii 63–4 as possible sources for this image.

48. their shaping: ‘what they made’, ‘their accomplishments’. ‘Shape’ as a verb originally meant ‘to create, to give form’, and until the 16th century was applied to God as creator; it retained strong associations with both physical and imaginative creation. OED cites Tennyson, ‘Lady Godiva’: ‘And there I shaped / The city’s ancient legend into this’ (ll. 3–4).

49. the bard and sage: generic terms for poet and philosopher.

50. gowned him: enrolled as a student (from the academic gowns worn at ancient universities).

54. Accents: the primary sense is the ‘accent’ of the voice, but its use here evokes the marks used to indicate stress in Greek prosody; see headnote.

60. comment: commentary.

61. know all: cp. the ‘principle of restlessness / Which would be all, have, see, know, taste, feel, all’ which characterizes the speaker of Pauline (ll. 277–8,

p. 26); see also l. 65n.

63–4. Cp. Karshish’s description of himself as ‘the picker-up of learning’s crumbs’ (An Epistle 1, p. 511).

65. Cp. Pauline 426–7: ‘And I—ah! what a life was mine to be, / My whole soul rose to meet it’ (p. 35).

68. ‘He spurned the possibility of living his life before he had completed his training for it.’ spurned it!] spurned it. (1863–88).

71. ere steel … quartz: the image is of dressing sandstone, which is composed of quartz, for use in building. In a letter to EBB. of 13 July 1845, B. used the image of a building site for work in progress, breaking down the absolute distinction between planning and execution which he maintains here: ‘when I try and build a great building I shall want you to come with me and judge it and counsel me before the scaffolding is taken down, and while you have to make your way over hods of mortar & heaps of lime, and trembling tubs of size, and those thin broad whitewashing brushes I always had a desire to take up and bespatter with’ (Correspondence x 306).

72. mortar: with a possible pun on the ‘mortar board’ hats worn by academics. 75. peculiar grace: a term drawn from Protestant theology describing the quality which sets the ‘elect’ apart; cp. Isaac Watts’s version of Psalm cxlviii: ‘God is our sun and shield, / Our light and our defence; / With gifts his hands are filled, / We draw our blessings thence: / He shall bestow / On Jacob’s race / Peculiar grace / And glory too.’

77. Still before] That before (1863–88).

81. time escapes,—] escapes! (1863–65, 1872); escapes: (1868, 1888). This is a rare example of B. changing his mind three times in the course of successive editions. 83. dogs and apes: cp. Milton’s sonnet on Tetrachordon: ‘owls and cuckoos, asses, apes and dogs’ (l. 4). B. could have found the exact phrase in a satirical topo-graphical poem by Charles Cotton, The Wonders of the Peake (1681), in which the ascent up a mountain is described as anything but civilized: ‘Propt round with Peasants, on you trembling go, / Whilst, every step you take, your Guides do show / In the uneven Rock the uncouth shapes / Of Men, of Lions, Horses, Dogs, and Apes: / But so resembling each the fancied shape, / The Man might be the Horse, the Dog the Ape’ (ll. 109–14). ‘Dogs and apes’ also appear in ‘The Ass and Brock’, a fable by Allan Ramsay (1686–1758): ‘The Ass … Pour’d out a Deluge of dull Phrases, / While Dogs and Apes leugh [i.e. laughed], and made Faces’ (ll. 33, 37–8).

86. Calculus: ‘The stone in the bladder’ ( J.); J. M. Ariail (PMLA xlviii [1933] 955) suggests an allusion to the other meaning of mathematical computation. 87. dross of lead: technically the scum of the metal left after boiling; the term ‘dross’ also connotes ‘dregs’, ‘impurity’, ‘worthlessness’. OED cites Milton, Paradise Regained iii 23: ‘All treasures and all gain esteem as dross’.

88. Tussis: a cough; Ariail (see l. 85n.) notes that ‘tussis’ is the paradigm of ‘disyllabic i-stems of the third declension in Latin’, with the suggestion that it therefore represents a particularly significant example of this class of noun.

95. soul-hydroptic: ‘hydroptic’ is an incorrect popular form of ‘hydropic’ ( J. has ‘hydropick’), from the medical condition known as ‘dropsy’, the morbid accumulation of fluid in the body; OED cites a suggestive use by Donne (Letters [1651] 51): ‘An hydroptique immoderate desire of humane learning and languages’. The term ‘soul-hydroptic’ is B.’s coinage, and his positive valuation of a ‘sacred thirst’ is unusual; most instances of dropsy as an image of excessive thirst are negative (OED cites Shenstone, 1763: ‘Thy voice, hydropic fancy! calls aloud / For costly draughts’).

97–100. Cp. the mistrust of material rewards in Pictor Ignotus (ll. 46-56, p. 230), and the circle metaphor in Old Pictures 133–6 (pp. 419-20).

101–4. ‘Did he not give God the chance to show that the life to come supersedes and perfects this life?’ See headnote, Criticism.

103–4. The primary sense is that the next life represents the completion, or consummation, of this life. B. plays on the fact that ‘period’ can mean both a course of time, and the point of completion or consummation of such a course; he almost certainly had in mind other connotations of the word, esp. in grammar and rhetoric (‘a complete sentence’, usually made up of several clauses), and ancient prosody (‘a metrical group or series of verses’), as well as more specialized uses such as those belonging to artistic or geological ‘periods’. Cp. Abt Vogler 72 (p. 768): ‘On the earth the broken arcs; in the heaven, a perfect round’.

104. Perfect] Complete (H proof, but not H proof2). The accent falls on the first syllable: Pérfect.

105. magnify the mind] make the most of mind (H proof, but not H proof2).

107–8. This metaphor is drawn from the world of finance, and so continues the mercantile analogy of ll. 99–100. The comparison is with a bond or promissory note which can be ‘discounted’ or sold for its present worth before the full sum becomes payable; ‘fools’ who opt for this arrangement receive their payment ‘by instalment’ rather than all at once.

109. neck or nothing: a proverbial expression deriving from horse-riding and meaning ‘all or nothing’; cp. Byron, Don Juan viii 355.

112. pale: paltry, inadequate.

116. knows: ‘achieves’.

117–20. Cp. Bishop Blougram 544–54 n. (p. 315); and cp. B.’s letter to EBB. (cited in headnote to Popularity, p. 446) on the subject of the painter Benjamin Haydon’s inconsistent response to critical neglect: ‘now with the high aim in view, now with the low aim’.

120. Misses an unit: either ‘falls short by one’ or ‘fails to accomplish anything at all’; the latter reading is more consistent with the general sense of the passage.

121–2. ‘Let the world (which he has chosen) take care of him.’ Cp. Matthew vi 2, 5, 16, where those who do things for worldly reasons are said to ‘have their reward’ in this life (i.e. they have sacrificed their chance of salvation).

121. That: ‘That one’ (i.e. the ‘low man’).

123. This: ‘This one’ (i.e. the ‘high man’).

124. Cp. Matthew vii 7: ‘Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you.’

127. rattle: the ‘death-rattle’, the sound caused by laborious or obstructed breathing in a dying person’s throat. parts of speech: both ‘incomplete utterances’ and grammatical particles of the kind described in the next few lines.

129. Hoti’s business] Oti’s business (H proof ). Nuttall (see ll. 13–16n.) states that ‘hoti’ is not a particle, but most commentators agree that it is a conjunction meaning ‘that’.

130. Oun: a conjunction denoting inference, like ‘therefore’.

131–2. The ‘enclitic De’ required several attempts at explanation by B.; see the letter to Tennyson (headnote, Sources) and another published in the Daily News on 21 November 1874: ‘In a clever article this morning you speak of “the doctrine of the enclitic De”—“which, with all deference to Mr. Browning, in point of fact does not exist.” No, not to Mr. Browning: but pray defer to Herr Buttmann, whose fifth list of “enclitics” ends “with the inseparable De”—or to Curtius, whose fifth list ends also with “De (meaning towards, and as a demonstrative appendage)”. That this is not to be confounded with the accentuated “De, meaning but”, was the “doctrine” which the Grammarian bequeathed to those capable of receiving it.’ Maynard (p. 271) notes that T. H. Key, one of B.’s tutors at the University of London, introduced the term ‘enclitic’ into his Latin Grammar.

134. purlieus: used here in the general sense of ‘a place where one has the right to range at large; a place where one is free to come and go, or which one habitually frequents; a haunt’ (OED 2); since the location is at the highest and most central point of the city, B. may have been aware of, and deliberately reversed, the sense of ‘purlieu’ as an outlying district or suburb, esp. ‘a mean, squalid, or disreputable street or quarter’ (OED 4).

139. Cp. Paracelsus ii 578–81 (I 187).

141–4. Cp. the opening of Shelley’s ‘Fragment: Supposed to be an Epithalamium of Francis Ravaillac and Charlotte Corday’: ‘’Tis midnight now—athwart the murky air, / Dank lurid meteors shoot a livid gleam; / From the dark storm-clouds flashes a fearful glare, / It shows the bending oak, the roaring stream’.

142. loosened: freed from restraint ( J.).

143. let] Let (1865–88). storm—] storm, (1863–88). We record these minor variants because they bear on the text of Berg MS (see headnote); this extract does not have the first reading, but does have the second, making it almost certain that B. was copying it from 1863.

145. Either ‘The grandeur of his conceptions must be matched by the setting for his burial’, or ‘The grandeur of his conceptions must have an outcome as spectacular as the “effects” of weather just described’.

148–9. still loftier … dying: either ‘He was loftier than the world knew, both in his life and in his death’, or ‘He is loftier than the world realizes, in that he is perpetually presenting us with a supreme example of human aspiration’.