On December 17, 1917, Canadians went to the polls in the most notorious election in the country’s history. Borden’s Unionists had made the issue perfectly clear: support for Canada’s boys at the front. Those who failed to back the government were tarred with all the dirt the prime minister and his public relations teams could dig up. The outcome surprised no one: Union won a large majority in the House of Commons, taking fifty-eight percent of the civilian popular vote, ninety-two percent of the military vote and 153 of the 235 seats. The Liberals were reduced to a regional rump, holding sixty-three of Quebec’s sixty-five seats: only two of fifty-five in the West and eight of eighty-three in Ontario. Only one French Canadian, actually from an Ontario riding, won a seat for Union, while the Liberal party now had a francophone majority. Quebec and the rest of Canada had never been more divided.

The situation in the Maritimes was less clear. Nova Scotia’s Sydney Daily Post gleefully proclaimed the election to be the victory of “the trench vote” over “the French vote,” yet a third of the region’s seats — ten out of thirty-one — went Liberal. More importantly, without the support of overseas military voters, this number would have been seventeen out of thirty-one. Clearly, locally born Maritimers also had problems with conscription — a fact that has escaped the attention of scholarship on the First World War so far.

F.J. Robidoux, MP for Kent and a passionate advocate for the Military Service Act. Running for Union in 1917 cost him his seat and his deposit, and earned him the dubious distinction of suffering the worst defeat in the conscription election. CEA PB1- 83e

New Brunswick characterized this trend. The province returned eleven MPs in the December 1917 general election, seven for Union alongside four Liberals, with victories on both sides won by wide margins. The electorate became polarized: the Liberals were preserved by Acadian voters, the south went solidly pro-conscription and the military voters mainly increased the margin of already-assured Union victories. The races in each riding reveal a great deal about New Brunswickers’ complex responses to the conscription crisis.

Although Kent incumbent F.J. Robidoux ran as a Union candidate, he could not overcome massive Acadian support for the Liberals in his riding. Robidoux advocated for conscription in Parliament, on the hustings and through Le Moniteur Acadien, and was rewarded with the province’s largest per-capita electoral defeat and the loss of his own electoral deposit. But Robidoux’s fate was hardly a surprise: Kent was a traditional Liberal riding, and Robidoux’s 1911 victory for the Conservatives was a greater shock than his defeat in the conscription election. To make matters worse, the party to which he had devoted a decade of his life abandoned him. Robidoux understood his people’s opposition to conscription, writing to J.D. Hazen: “The French people are inclined to be opposed to the Military Service Act; it has been represented to them by interested parties wishing to make political capital that this act was designed to get at the French people; they are prompted to view with distrust the enforcement of the act.” When Robidoux requested changes to offset these legitimate concerns — such as more francophones on exemption tribunals, Frenchspeaking doctors on medical boards and conscription information in French — Unionists refused each time. Clearly, the powers in Ottawa were willing to abandon their Acadian supporters in order to preserve Union’s wider image as an anti-French and anti-slacker movement. Robidoux won only seven of twenty-three polls, all marginal victories in non-Acadian areas. Liberal Auguste T. Léger, whose son, Major Joseph Arthur Léger of the Canadian Forestry Corps, had publicly broken with his father and backed conscription, benefited from Union floundering, winning the Kent riding by more than 2,000 votes.

Cartoon urging women to vote in support of conscription. HIL, Sackville Post, December 4, 1917, p. 2

Other predominantly Acadian ridings produced similar results. In Gloucester, incumbent Onésiphore Turgeon, a staunch anti-conscriptionist, was acclaimed after the Unionist Édouard DeGrâce dropped out of the race just five days before the election. DeGrâce’s decision avoided an electoral annihilation that would have rivalled Robidoux’s, especially as the relatively unknown candidate received even less support from Unionists than the Kent incumbent. Similarly, in the contest in the combined riding of Restigouche and Madawaska, which pitted Liberal Pius Michaud against D.A. Stewart, the result was a foregone conclusion. Michaud complained throughout the campaign about the propaganda circulating against francophones in the area. He even raised the issue in the House of Commons, asking, “What is the trouble with the highly-paid political campaign writers in Ontario who are sending to New Brunswick literature similar to that which is being used against the province of Quebec? I ask my friends on the other side of the House to stop sending this seditious literature, for we want to continue to respect one another; we want to continue to work together for the one great purpose of winning the war.” Michaud’s appeal also failed to resonate. Stewart fared well in some areas, capturing all six polls in his Campbellton hometown and receiving strong support throughout Restigouche, but in Madawaska county he garnered only 124 total votes and never more than twenty-two in any one poll. Fully ninety-six percent of Madawaska’s voters preferred the Liberal candidate. The military vote could not save Stewart, and Michaud glided to an easy victory.

Unlike these one-sided contests, one northern riding produced an actual race. In Northumberland, the Miramichi’s always volatile rival newspapers reflected the close and nasty spirit of the competition. Newcastle’s North Shore Leader supported fur merchant, department store owner and regular North Shore Leader advertiser John Morrissy of the Liberals, while Union incumbent and Liberal defector W.S. Loggie had the backing of Chatham’s The Commercial and The World and Newcastle’s aptly named Union Advocate. The North Shore Leader accused Loggie, also a prominent merchant, of war profiteering just three days before the election. This came in response to the Advocate’s own claim that Morrissy, to avoid conscription, had proposed to hire “100,000 to 500,000 Chinese, Japanese, or East Indians to fight our battles for us.” Loggie captured most of the polls, but his success was offset by Morrissy’s large victories in working-class and Acadian areas, most notably in Rogersville, which Morrissy won 396 votes to nineteen. Loggie led by only eighty-six ballots when the civilian results came in, but the votes of Northumberland’s large military contingent, overwhelmingly in favour of the Unionists, gave the incumbent a comfortable margin of victory. The Commercial ecstatically announced the result by printing a large Union Jack on its first page.

Significantly, Westmorland, nearly forty percent of which was francophone, produced the only Liberal victory by an anglophone. The victorious incumbent, Sackville barrister Arthur Copp, also possessed partisan media support, which made him the envy of the province’s other Liberal candidates. Party loyalty remained incredibly strong in the riding as well, even among soldiers: Private Vincent Goodwin noted that he and his fellow Westmorland soldiers in the 2nd Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade voted Liberal, as they had always done, despite the creation of the Union government and the centrality of the conscription issue. Likewise, after the election, Private J. Ulric LeBlanc, 26th Battalion, from Cap Pelé, wrote home to his parents, “Conscription is passed although I won’t hide and say that I voted against it. The only way I would have voted for it was if they had conscripted the wealth of the Country first.”

The Sackville Post, one of the few press opponents of the Liberals in Westmorland, tried to erode support for Copp by publishing a fabricated letter from him to the soldiers. “Dear boys,” began the piece, “I am the Laurier candidate in Westmorland county and I hope to be elected largely because of the Acadian support I hope to get. I know I voted against sending reinforcements to you, but I could not help that Laurier wanted me to vote that way, so I did. I believe in carrying on the war to a successful conclusion, but how it is going to be carried on without more men I have not exactly figured out yet. But if you will elect me and Laurier is returned to power we will arrange it some way.” These Union tactics may have proved successful elsewhere, but they did not help in Westmorland. In fact, Copp even captured more of the surprisingly small military vote than did his opponent, Moncton dentist O.B. Price. Price’s only substantial poll victories came in Salisbury and some English-speaking parts of Moncton, while Copp handily captured the remainder, earning especially large majorities in Acadian areas. Copp became one of the few Protestant anglophones in Laurier’s caucus, and in May 1918 Westmorland’s representative was the first to accuse the Union government of electoral fraud.

Not all soldiers died at the front: the funeral of Private William Darling, New Brunswick Military Hospital (Old Government House). NBM 190.11.24

While the Liberals took all but one seat in the north, New Brunswick’s southern counties unanimously declared for Union, with huge civilian and even greater military vote totals. With only a very small Acadian population, Liberal support in the south, including the candidates themselves, was largely rural: farmers, fishermen and labourers. Still, most farm and labour voters in the south supported the Unionists, thanks in large measure to the high numbers of enlistments from these groups, the farmers’ conscription exemption, nearly unanimous press support and the association of the Liberals with French slackers who opposed the war.

In Victoria and Carleton, despite his stunning defection from the Liberals, Frank Carvell had no difficulty retaining his seat — in fact, he had no opponents, and his acclamation, like Turgeon’s in Gloucester, simply allowed the opposition to avoid a humiliating defeat. In York and Sunbury, the Protestant vote was courted by Fredericton’s H.F. McLeod, a leading Orangeman who held the honour of riding the white horse during the capital’s annual marking of the Glorious Twelfth, celebrating the Protestant victory over Catholic King James at the Battle of the Boyne in 1692. Stanley parish farmer Daniel MacMillan recorded little about the election campaign in his otherwise faithful diary, only noting on December 18, 1917, “A new feature of yesterday’s election was the presence of ladies casting their votes for the first time in the history of this country.” McLeod’s Liberal rival, N.W. Brown, managed to win rural polls in Burton, Manners Sutton and Stanley, but barely registered in Fredericton itself; in the end, McLeod won by nearly 4,000 votes.

The riding of Royal, made up of Kings and Queens counties, produced more of the same. Hugh Havelock McLean, 62, was the quintessential Union candidate, an Orangeman, retired militia officer and former Liberal. His farmer opponent, F.E. Sharpe, stood little chance. Support for Sharpe came not from farmers, who abandoned their colleague for Union, but from labourers who remembered that McLean’s term as president of the Saint John Railway Company had coincided with the violent crackdown of the 1914 streetcar strike in the city. Nevertheless, McLean won all of the riding’s most important polls, including all eight in Sussex, while Sharpe conclusively captured only one Chipman poll. The result gave Union another seat by more than 3,000 votes.

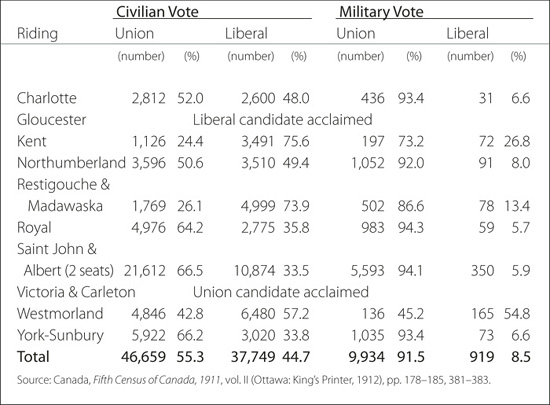

The remaining seats in Charlotte, Saint John and St. John and Albert counties also went Union, but against greater opposition, which was fended off only by military voters and no little distribution of patronage. In Charlotte, a rematch of the last election between Liberal W.F. Todd and Union’s T.A. Hartt, both of whose occupations were listed only as “gentlemen,” produced the closest race. Todd captured the fishermendominated island vote in the Passamaquoddy area, just as he had six years earlier, leaving Hartt a slim lead of 212 votes. The incumbent held on, thanks to the support of mainlanders and the riding’s five hundred military voters. The two Saint John ridings represented the opposite result, giving Union its largest margin of victory. R.W. Wigmore, the replacement for new provincial chief justice, J.D. Hazen, triumphed by thousands of votes. In the Saint John City riding, however, William Pugsley presented a problem for the Unionists. After missing the Military Service Act vote in the House, but voting in favour by proxy, Pugsley publicly declared his opposition to the measure. To avoid embarrassment, Union supporters convinced the veteran politician to accept the post of lieutenant-governor. Another Liberal defector, S.E. Elkin, captured Pugsley’s former seat in his stead. Liberal candidates W.P. Broderick and A.E. Emery, both Catholics and medical doctors, won polls in workingclass areas of Saint John, St. Martins and in rural Albert county, but the overall vote was solidly Union, as Table 2 shows.

Table 2: Results of the 1917 Federal Election, New Brunswick

The often-vicious 1917 federal election revealed clear trends. The most important of these, which grew out of the military stalemate on the Western Front, the recruiting shortfalls and the growth of anti-French feeling, was the glaring difference between northern and southern New Brunswick’s views of conscription. Four of the five northern ridings, all with large Acadian populations, went Liberal. In the south, however, no real opposition to the Unionists existed. On the other hand, the military backed conscription in even greater numbers than did civilian Union supporters, with provincial soldiers giving 9,934 votes to Union against only 919 for the Liberals. Unionist tactics, especially blatant anti-French propaganda, produced landslide victories in the south at the cost of deeply dividing the province. Union’s leaders may have understood that Acadians opposed not the war, but conscription — they just did not care. Winning the election meant dividing the country and tarring all French Canadians, a central Canadian euphemism for Quebecers, as slackers. New Brunswick and its large Acadian population could not escape this slander, which had severe long-term implications for the province’s social harmony.

Nevertheless, the election at least seemed at last to have decided the reinforcement issue, and Canada entered 1918 prepared to help win the war. Unfortunately for those who supported this plan, there was not much else they could do. The voters had spoken, but not all of them faced the prospect of compulsory military service. After consulting with their families and friends, struggling with whether they might still be needed on the farm or in the factory and reporting to the exemption tribunal, individuals decided whether or not they wished to be conscripted. Most chose not to be.

In early 1918, those who had been classed Military Prospects 1A by the exemption tribunals received their decisions. Nationally, 21,568 had reported for service, while 310,376 had applied for exemption. Nearly seventy percent of those men received it, including more than 5,000 New Brunswickers, among the last of the physically fit young men left in the province. The local tribunals were especially considerate of the descendants of many generations of farmers and fishermen in northern New Brunswick and Charlotte county. Anselme M. Léger, an exemption tribunal judge in the Shediac region, privately noted that he saw thirtynine cases, mostly children of subsistence farmers in May 1918, “et on les a tous exemptés jusqu’au premier novembre.” Union supporters predictably claimed that a number of the excuses and disabilities brought before the tribunals had been fabricated, but they had little evidence to support these claims and failed to overturn the decisions.

The first conscripts began training, but they would not be able to reinforce the troops overseas for months, if the example of Private Goodwin — who enlisted voluntarily in 1916 but arrived in France only on March 25, 1918 — was any indication. But troops were still urgently needed to face the resurgent German army. When communist Russia withdrew from the war in March 1918, the Germans began moving hundreds of thousands of troops from the Eastern Front to the West. The German high command believed these troops would break the stalemate and help defeat the Allies before the United States could decisively enter the war. The Allies knew an attack was coming, but they still were not fully prepared for it. On March 21, the Germans launched a massive offensive against the British lines south of Arras. The attack broke through, destroyed or dispersed British and Allied divisions and captured large amounts of French territory. Over the next three months, additional German attacks put the Allies firmly on the defensive, with each one threatening to fulfill the German plan for victory. Fortunately for Canada, the Canadian Corps was secure atop Vimy Ridge and remained out of the action during the German onslaught of March to May 1918.

Meanwhile, problems on the homefront worsened. On March 30, a rally protesting the police detention of a man exempted from conscription in Quebec City saw other young men burn their registration cards in public. The number of marchers increased, and the small rally soon grew into a thousands-strong anti-conscription riot, with protesters hurling projectiles at police and soldiers. Ottawa decided to call out partially trained Ontario battalions to disperse the rioters. On April 1, the English-speaking troops lost control of the situation and opened fire on the crowd. Four civilian bystanders were killed and the nation teetered on the brink of civil conflict. Young men fearfully took to the woods to escape the authorities, but the Borden government backed down. The fear of additional violence paralyzed attempts to call up Quebec conscripts for the rest of the war.

Union Party advertisement. HIL, Sackville Post, December 11, 1917, p. 6

Higher employment rates, often in high-paying wartime jobs such as the production of artillery shells at the MacAvity Foundry, Saint John, discouraged voluntary enlistment by the middle of the war. PANB P49/1-26

Faced with the German offensives in France and desperate to do whatever they could to help prevent disaster in Europe, on April 12 the Canadian government passed an Order-in-Council cancelling all previous exemptions, overturning the findings of the local exemption tribunals and immediately placing all physically fit single men ages twenty to twenty-two in the military. Farmers reacted angrily, believing the government had broken its promise to them. On May 15, five thousand of them marched on Ottawa to demand the government keep its agricultural exemption policy regardless of the state of the fighting. The government refused to back down, arrogantly urging farmers to be less selfish instead. In June, the government began a national registration of women, some of whom would find themselves in “nontraditional” manufacturing and labour positions because of the severe shortage of male workers that had been exacerbated by conscription.

Newspaper report of the death of Lorenzo Sawyer. HIL, Carleton Sentinel, May 24, 1918, p. 1

Resentment in New Brunswick during 1918 mirrored national events. Other factors also made conscripting and training difficult. In April, an outbreak of smallpox, joined a few months later by Spanish influenza, resulted in a temporary enlistment ban for Gloucester, Kent, Northumberland and Restigouche counties. According to the North Shore Leader, men from elsewhere in the province broke the quarantine and risked contracting a highly contagious and often fatal illness by migrating to the northern counties to avoid conscription. Although nothing like the violence of the Quebec City riots occurred in New Brunswick, anecdotal evidence suggests that groups of young men dodged conscription by hiding together in fortified camps in the woods, especially in Kent county and other rural areas. The worst incident between the authorities and a deserter occurred on May 20. Newly married Lorenzo Sawyer, twenty-four, could not make up his mind about military service. He had previously enlisted in the 165th Acadian Battalion, but deserted before the unit went overseas. When served with a conscription notice by his local exemption tribunal nearly two years later, Sawyer took to the woods. The Dominion Police, a new federal force created solely to enforce the Military Service Act, pursued him. When cornered outside Bouctouche, Sawyer resisted arrest and the police shot him. Despite the valiant efforts of a local doctor, the young man died from his wounds. This unfortunate incident only increased Acadian criticism of the government and hardly encouraged trust in the conscription authorities. Nonetheless, Le Moniteur moved even further into the political wilderness by continuing to urge Acadians to embrace the “justice égale” of compulsory service.

Provincial farmers joined their national leaders in denouncing the broken exemption promise. Frank Carvell, now the federal minister of public works, defended the government’s drastic move, but even normally supportive newspapers like his own Carleton Sentinel disagreed with him. In the streets and fields of Woodstock, Hartland and Perth-Andover, people began to mutter, just as they had already been doing for some time in Caraquet, St-Louis-de-Kent and Jacquet River, that Carvell and all the rest of the politicians in Ottawa had betrayed them.

Carvell, however, was right about one thing: reinforcements were needed even more than ever. The British, who had been conscripting men for more than two years, handled their own reinforcement problem by reducing their brigades from four battalions to three, to bring the remaining units up to strength. The Canadian Corps had already resorted to breaking up the 5th Division, sending its soldiers, including the 104th (New Brunswick) Battalion, to France as general reinforcements. This increase greatly improved the fighting strength of the already-feared Canadian Corps. Safe on Vimy Ridge from the attacks that surged around them, the corps absorbed the reinforcements, and trained and prepared itself to lead the counterattack when the German effort was spent.

By August 1, thanks to the supreme efforts of other Allied troops, the front stabilized again. The Germans had made the furthest advances since the initial invasions in 1914, pushing to the Marne River while recapturing the ground the Allies had suffered so terribly to seize at the Somme and Passchendaele. But the cost had been unbelievable: roughly a million Germans killed, wounded and missing in three months of brutal fighting. Like Canada, Germany now had no more reinforcements, and the Americans now had sufficient forces on the Western Front to tip the balance in the Allies’ favour. The Allies knew they would have to try an all-out attack to break the enemy if they were to end the war in 1918.

The Canadian Corps led these final attacks. Indeed, the corps had become such a skilled and powerful instrument that tremendous efforts were made to prevent the Germans from learning its whereabouts. Initially, the Allies announced the Canadians would be moving from the Vimy front northwards to Ypres, but instead covertly transported them to the Somme area — where the attack would actually begin. Officers and NCOs ordered their men to keep quiet while they carried out vital training behind the Allied lines.

On August 8, the Canadians, with Australians and New Zealanders, decisively defeated the Germans at the Battle of Amiens. The 26th Battalion, again going into action with their trusty comrades from Montreal, the 24th Victoria Rifles, led the second phase of the attack. Supported by tanks, cavalry, mobile machine gunners and artillery, the two battalions spearheaded the 2nd Division’s thrust through the German trenches and into the open fields beyond, to a penetration of thirteen kilometres. The Germans were stunned by the speed and the depth of the assaults, losing 30,000 men and forced to fall back on the defensive Hindenburg Line. Their commander-in-chief, General Erich von Ludendorff, described the attack on 8 August as “der Schwarze Tag,” the Black Day of the German army.

Black it may have been, but it did not end the war. The Germans still had defensive positions in depth and remained committed to defending their gains. Normally, the Canadian Corps would have rested and recuperated after playing such a central role in battle. Yet suddenly the war seemed winnable, so every attack had to be launched without delay — and now virtually every major offensive included the Canadians.

New Brunswickers fired their share of the province’s shell production. In addition to No. 4 Siege Battery from Saint John, men from New Brunswick also served in No. 6 Siege Battery, seen here firing in support of the final offensives during October 1918. NBM Humphrey, F5-36

The main German defences that comprised the Hindenburg Line had been built and fortified over nearly two years, and many, including senior Allied officers, considered it impregnable. The Canadian Corps nevertheless began its scheduled assault on the line east of Arras on August 26, just three weeks after Amiens, which launched the Hundred Days campaign that was to win the war. In the first hours of the offensive, the 26th Battalion forded the Sensée stream, but met strong German resistance and could not continue. Further feats were needed to breach the line, including a dashing Canadian crossing of the Canal du Nord on September 18. By October 5, costly attacks allowed the Allies, again led by the Canadians, to batter through the Hindenburg defences. Three days later, the 5th Brigade entered Cambrai, forcing the surprised Germans to quicken the pace of their now continuous withdrawal.

Despite the gains, the fighting was fiercer than ever, and it continued to take its toll on New Brunswick. By the start of the Hundred Days campaign, there were finally two New Brunswick infantry battalions on the Western Front. After years of having provincial recruits augment battalions from elsewhere in Canada, the 44th Manitoba Battalion was renamed the 44th New Brunswick Battalion, mainly due to the influx of conscripts from the province. Individual soldiers of both battalions, including Privates Stephen Pike and J. Ulric LeBlanc, along with reinforcements like Bathurst’s George Gould and his cousin Tom DesRoches, played a key role in shattering previously invincible German positions and pushing the invaders out of northern France.

Their efforts, however, meant that the casualties never stopped coming in the late summer of 1918. In breaking the subsidiary Drocourt Quéant Line in late August and early September, the 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion and its large Acadian component — supported, as ever, by the 26th Battalion in the 5th Brigade — lost five hundred men, including every one of its officers. Only thirty-nine of the battalion’s troops came through the fighting unscathed.

Once they had broken through the line and into the open, however, the Allies pursued the retreating Germans mercilessly. Private Goodwin of the 2nd Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade saw extensive action during this fighting. He and his comrades were constantly moved along the line to provide additional firepower for the attacking troops, their machine guns often making the difference between success and failure. On Armistice Day, November 11, the Canadian Corps liberated Mons, Belgium, where the British had suffered their first defeat of the war four years earlier. At 11 o’clock that morning, the Canadian-led attacks on the Western Front came to an end: the intense fighting since August had driven Germany to the brink of collapse. The Allies had won the war.

The cost to Canada during this final push was staggering: twenty percent of the Canadian Corps’ entire wartime casualties occurred in just ninety-six days: 45,830 men killed, wounded or missing. Deaths during the final days of the conflict hit some already-grieving families particularly hard. Private Frederic W. Fullarton, from tiny Williamsburg, near Stanley, serving with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, was killed in action near Mons on November 8, 1918; the Fullartons had lost another son at Lens in 1917.

The names of the fallen filled Canadian and New Brunswick newspapers for many weeks after November 11. At war’s end, 61,000 Canadians, including 2,347 New Brunswickers, had died on active service. The remains of most of them lie scattered in hundreds of cemeteries from Amiens to Ypres; the names of the missing appear on memorials at Vimy and the Menin Gate. Another 212,000 Canadians had been wounded in the fighting, many of them maimed or suffering from exposure to gas for life, others scarred with psychological problems that were untreatable by the standards of the day.

Ironically, despite the urgent need for reinforcements and the bitterness of the battle over the Military Service Act, few conscripts played a role in the final fighting: only 24,000 ever reached France, and many never got to the front before the war ended. Yet this boost proved just enough to keep the Canadian Corps close to full strength in the last days despite its exertions. In contrast, the Australians, who did not adopt conscription and whose troops also spearheaded the final Allied attacks, ground to a halt on October 5; for better or worse, the Canadian Corps ended the war fighting hard.

Despite the issue of exemptions, outbreaks of disease and backwoods deserters, fears of violence or other serious problems between volunteers and conscripts proved unfounded, although the hardened veterans did not always welcome conscripts. Private Goodwin from Baie Verte remembered, “the conscripts that I knew who got sent over were not much good anyway.” Considering the division the issue had caused and the little training conscripts received before reaching the front, this should not have been a surprise. The case of the Crouse brothers from the village of Zealand Station, York county, illustrates both where conscripts were most needed and where they were most likely to become casualties. Conscripted in January 1918, Howard Crouse was undergoing specialized engineering training in Wales, far from the fighting, on November 11. His brother Ellsworth, conscripted as an infantry private and assigned to the 25th (Nova Scotia Rifles) Battalion, died of wounds received in the fighting to breach the Hindenburg Line on October 2, less than a month after his arrival on the Western Front and just weeks before the end of the war.

In all, 27,000 New Brunswickers served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the Great War. Some 20,000 of these were volunteers, representing 4.2 percent of the total of troops mobilized by Canada between 1914 and 1918. The other 7,000 New Brunswickers were conscripts, representing 5.6 percent of the national total conscripted for service — the second-highest per capita conscript rate, trailing only that of Quebec. Since New Brunswick’s population represented only four percent of Canada’s eligible military manpower, the province was slightly overrepresented in the armed forces during the war.

In the opinion of the government and much of the country, both conscription and the sacrifices of families like the Fullartons and the Crouses had been necessary. Prime Minister Borden realized that if Canada wished to live up to its promises and assert the national identity it had won so heroically at Vimy Ridge, the country had to maintain a military force equal to those responsibilities. There is no doubt that Canadians proved themselves excellent soldiers and that they played a role out of all proportion to their size in defeating the Germans. For Unionists and their supporters, this trumped all considerations of domestic protest and even justified dividing the country.

Dedication of the Soldiers’ Monument, Shediac, July 26, 1924. NBM 1989.103.298