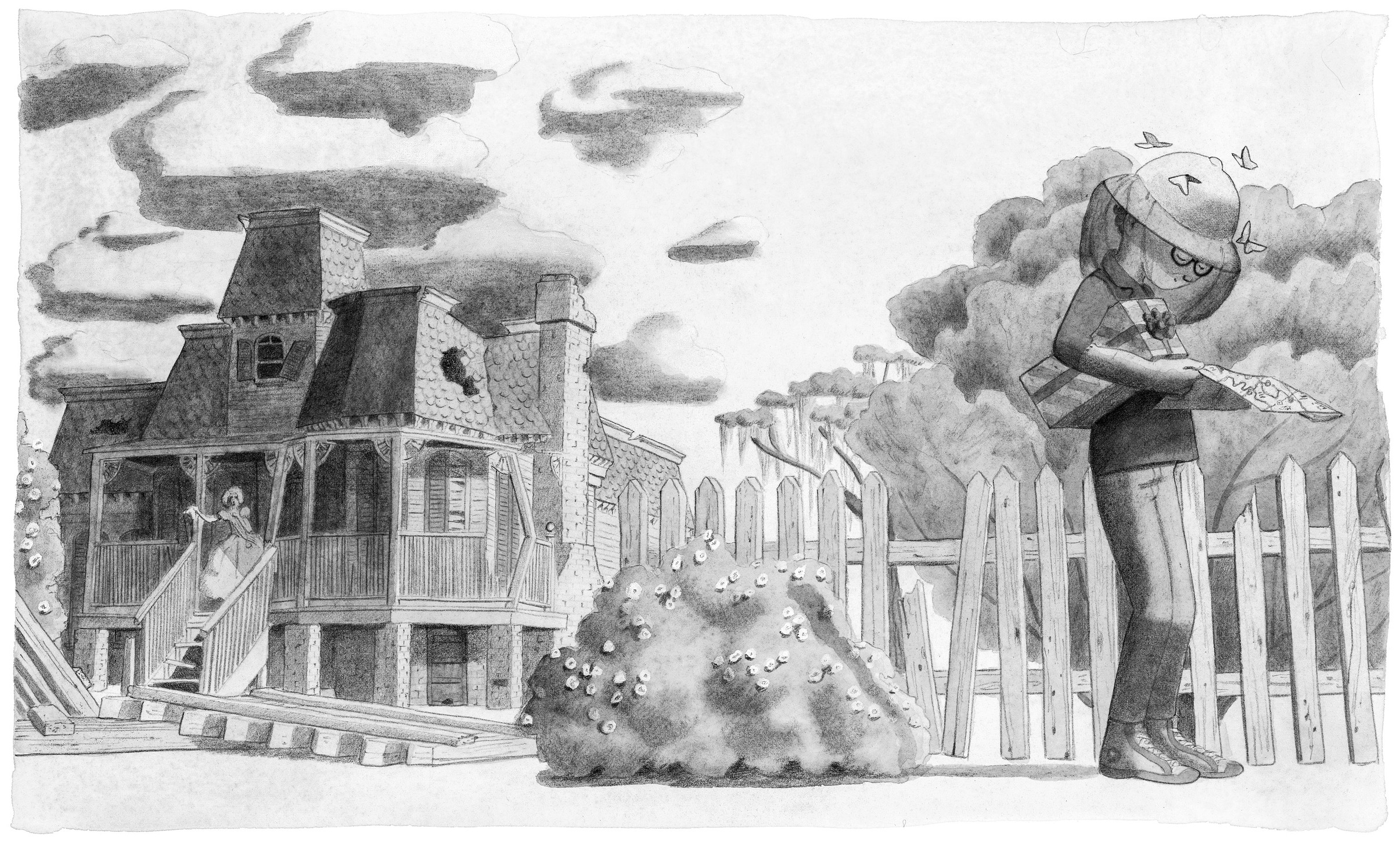

At three o’clock on Thursday, August passed through the gate into the lane. He paused to unfold the tattered driving map that Hydrangea had handed him at the front door. The wrapped box under his arm—a gift for Aunt Orchid—made the process rather awkward, and he was further hampered by the bulky beekeeper’s gloves and netted helmet his aunt had insisted that he wear.

“To safeguard you from those tiny monsters,” Hydrangea had said, delivering an enthusiastic grin that did little to conceal her terror.

And indeed, the “protective” clothing seemed to mask August’s unique scent sufficiently that his entourage of butterflies was reduced to two or three.

The boy waved the insects away so he might locate Château Malveau on the map. Having established the route, he lifted his head and, for the first time, got a good look at Locust Hole from the outside.

At some point, largely from watching television, August had come to understand that his home was unusually shabby and worn. But it was only upon regarding the building’s exterior from a distance that August came to appreciate its true level of decay.

It had been a finely built, handsome old house, with a broad, shady porch. Typical of that low-lying region, it was built on raised foundations, to spare the main floor from flooding and provide a half basement for storing the pepper barrels.

But the roof was balding, and it sagged where one of the slender posts supporting it had splintered. Shutters that weren’t nailed closed hung at crazy angles from one hinge. Most of the pretty blue paint had peeled away, and the clapboards beneath had been bleached to pale gray. Unchecked vines snaked through the railings, and the squat basement doors beneath the porch were rotting and green with moss.

Another decade, and Locust Hole would likely qualify as an actual ruin.

Aunt Hydrangea stood outside the front door. August knew she would venture no farther. From the gate she looked much smaller. Vulnerable. She raised her arm and weakly waved her handkerchief.

August returned her salute with a confident thumbs-up, turned, and walked away.

It didn’t take very long for the heat to catch up with him.

The boy had been too absorbed with his map and giddy with adrenaline to notice it immediately. But as he crossed the rusty local bridge that spanned Black River, August found his breathing labored and rivulets of sweat trickling across his ribs. You see, in summer months, towering banks of air from the Pirates’ Sea would roll across that place, smothering it with a blanket of thick, salty humidity.

Locust Hole, punctured as it was by patched-up holes, still largely sheltered those within from the sultry climate without. Now beyond its thick old walls, August felt like he was wading through a vapor of hot broth.

He pressed onward, to the main road (such as it was, for as mentioned, this was an out-of-the-way sort of place, and passing vehicles were few). The Old French Highway led into Pepperville, hugging the river’s winding passage. But any view of the water was obscured by the fields of blazing pepper plants that flanked the narrow ribbon of asphalt.

Field followed field. Nailed to the fences, sign followed sign, each informing passersby that all they observed belonged to Malveau Industries. How many signs had August passed? How much land did the Malveaus own? How long had he been walking?

He began to feel dizzy. It was too much. Too much at once. The heat. The bombardment of unfamiliar smells, sounds, and sensations. The boy felt overcome and limply slumped onto a large rock at the side of the road, knees weak, head spinning.

He lifted the net of his helmet and covered his ears. He closed his eyes and spent a minute inside himself, recovering in the darkly glowing nothingness.

When he was ready, August took a deep breath. He focused on the faint, flowery fragrance of water hyacinths and the earthy, dank smell of the roadside ditch they sprang from.

Slowly he unplugged his ears, gradually admitting the chorus of the cicadas. Time slowed, and within the insects’ buzzing, he heard something rhythmic and melodic, almost like a chant.

He heard the feather-soft flapping of a low-flying ibis headed toward the swamp. He heard the rustling clusters of flame-colored chilis, a million crimson fingers clutching at the tropical breeze.

The warmth of the yellow dirt penetrated the soles of his shoes. The ground seemed to press itself against his feet. Or was gravity pressing him into the ground? Could he feel a dull, distant throb, perhaps the very heartbeat of the earth?

Suddenly someone whispered in August’s ear.

His eyes snapped open, and he leaped up in alarm, spinning around to confront…whomever he was about to confront.

But there was no one there.

He was alone.

He was, however, facing a sizable clearing, some leafy interruption to the lengthy string of Malveau pepper fields; he could glimpse the twinkling river at the far end. A strange stillness hung about the place, where a cluster of large white stone boxes hunkered in the weeds and unkempt shrubbery. August had been sitting not on a rock but on the broken remnants of a tomb.

He was standing at the edge of a small cemetery.