“It’s the correct address.” August looked up at the shop front, then down at the receipt in his hands. “But Black River Tattoo,” he observed to Claudette, “doesn’t sound much like a jewelry store.”

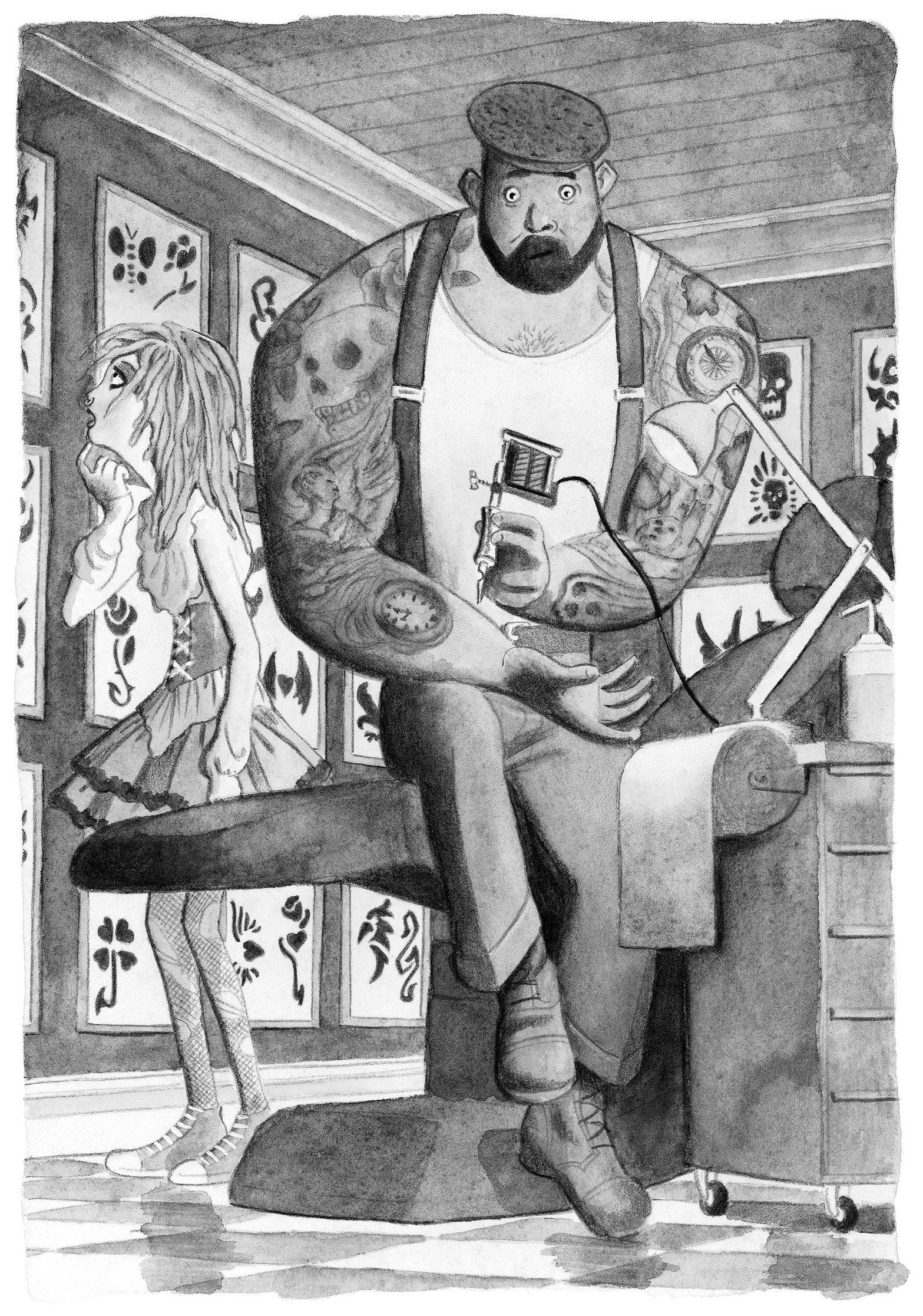

The boutique’s interior was compact, a feature enhanced by the entire place being painted dark purple and by the presence of an enormous, bushy-bearded man who consumed much of the available space.

He was perched upon a reclining seat, not unlike a dentist’s chair, and brow furrowed, he was applying a buzzing pen-like device to his own (already heavily tattooed) forearm. His head was slightly narrower than his giant neck, and his flat nose had the air of one that had been broken more than once.

A limp, poorly postured young woman stood nearby. She had pink dreadlocks that hung in all directions from the top of her head, even over her face, and her scrawny knees poked through ripped stockings. She was perusing the many framed pictures that smothered the walls, which, on closer inspection, were revealed to represent a vast catalog of tattoo designs.

“What do you reckon, Buford?” the young woman was saying as August and Claudette entered the store. “A crow? No, a scorpion!” She tilted her head, examining her options. “I know! How about a giant white alligator, like the one everyone’s been talking—”

She abruptly stopped midsentence upon spotting the newcomers. Beneath the ring dangling from her nose, an awestruck smile spread across her black-painted lips.

“Well, check out the little Goth,” she said with unchecked admiration. “That is an awesome look, girl! How’d you come by that sickly pallor? You look deader than a pork chop! I just love the dark eye circles. And are those”—she moved in to examine Claudette’s arm more closely—“oh, so cool: stitches?!”

Claudette lifted her hand to cover a sort of gurgling, simpering giggle.

“Good afternoon,” said August, nudging the zombie into silence and removing his helmet. “We’re looking for Juneau’s Jewel Box.”

“Gone, bro!” said the huge, bearded man without looking up. “Years ago.” He spoke in a kind of high-pitched, husky wheeze, almost as if he’d run out of voice. “It was my pawpaw’s place. We Juneaus have been jewelers for generations. The old coot gave me the business after he came down with that Peruvian flu; knew he was done for, I reckon.”

His eyes swiveled upward to engage August, although his head remained unmoved.

“And I tried to keep the place going. Really, I did. Honest!”

August wasn’t sure why he should warrant such an apologetic explanation.

“Even got myself a degree in gemology, I did.” Buford sat up now and, turning off the tattoo machine, placed it on an adjacent steel cabinet. “But I’m an artist, bro. Got to create. The ink, it’s in my blood; you know?”

August didn’t know in the least, but he nodded sympathetically.

“We still got some nice swag, though,” wheezed Buford Juneau, standing up so that his flat wool cap was merely inches from the ceiling.

He beckoned, and obediently August followed him to the back of the store, where beneath a row of horned cattle skulls, the cash register sat on a display case. Under the glass, resting on black velvet, was an exhibit of very particular jewelry: rings, pendants, and bracelets of silver, ornately cast in the shape of serpents, bats, and other grotesque designs. Some were set with colored gems that formed the eyes of dragons or were gripped in the talons of some disembodied monster.

“How about a little something in green,” suggested Buford brightly, “to complement the young lady’s complexion?”

August spread out the receipt that he’d found, as Hydrangea had suggested he might, stuffed in a drawer of his desk. It was obviously very old, one corner torn away altogether. At the top was a business letterhead, that of Juneau’s Jewel Box. Below, the paper was printed with faint green horizontal lines. Vertical lines of faded red and blue formed columns at left and right. The itemized entries were handwritten. The ink was faded but mostly legible.

“Actually,” said August, pointing at the document, “this family heirloom was sold to Juneau’s many years ago.” He gazed up at the tattooed gemologist. “I was wondering if you still have records of what happened to it…of who bought it from you.”

Buford unearthed a pair of glasses from his pocket. They had unexpected, bright blue frames.

“ ‘Raw Cadaverite. C and P,’ ” he read, peering down at August’s fingertip. “ ‘One hundred thirty-five dollars.’ ”

He straightened, rubbed his palms on his thighs, and glanced toward a narrow door in the corner. August could see, for the door was ajar, some boxes and toilet paper in the storage space beyond.

“Why, sure,” mused Buford, “we got records that go way back. But we don’t need those.” He returned to the receipt. “We didn’t buy this item from your family. See, this is the credit column. The one hundred thirty-five dollars isn’t a payment from us to the customer, but from the customer to us.”

August was puzzled.

“Why would someone pay you for their own property?”

“It’s not a sale, bro. This is a charge for services rendered. C and P; that’s shorthand for cut and polish—”

“Buford!” interrupted the dreadlocked young woman excitedly. “I know what I want!” She jiggled up and down, clapping her hands like a small child. “I want this girl, right here.” She jerked her thumb at Claudette, who grinned sheepishly. “On my left shoulder. Can you do her?”

Buford glanced at August and rolled his eyes.

“Sure, Destiny. If that’s all right with the little girl.” Claudette nodded with great enthusiasm. “Take a picture with your phone, okay?”

“What’s the meaning of ‘cut and polish’?” asked August, tilting his head to pointedly reclaim Buford’s attention.

“Well,” replied Buford, scratching the scalp beneath his cap. “Says here it’s raw Cadaverite, right? Means it’s still in its natural state. Most gemstones are pretty rough and ugly when they first get dug out of the ground. See these raw garnets?”

Buford withdrew a small cardboard box from a drawer beneath the register and removed the lid. Inside rattled a group of brownish, pea-sized stones, scuffed and dull, not unlike common gravel.

“Pretty drab, yes? Now, cut and polished.” He reached into the display case and placed a ring on the counter for August’s inspection. The bauble was formed in the shape of a pair of skeleton hands. They gripped a glowing, translucent gemstone of dark and lustrous red. “Unrecognizable, right? You’d never know it was the same stone.”

August stared at the ring, thinking.

“So, what,” he said quietly, “would cut-and-polished Cadaverite look like?”

“Oh. Now, that’s a rare one,” mused Buford. “Don’t see those often; most of them are locked up in museums, I reckon. But Cadaverite shines up to a swank sort of amber color. Real vivid. Lots of light refraction.” He took the garnet ring and returned it to the case.

“The best, and rarest, Cadaverites have this layer of compressed carbon at the center. Shows up like a swirl of black. Those specimens are usually cut into a perfect sphere. Like a marble, I guess.”

August’s jaw fell. His mind spun.

It couldn’t be.

Could it?

“A large, vivid amber marble,” he repeated, “with a swirl of black at the center?”

“That’s right, bro.” Buford nodded. “They look so like them that in the business, they’re known as alligator eyes.”