When the white man comes in my country, he leaves a trail of blood behind him.

—RED CLOUD OF THE OGLALA SIOUX

IN JULY 1865, unaware that the Civil War had ended four months earlier, the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho began preparing for their usual summer medicine ceremonies along the Powder River in what is now northeast Wyoming.

By late August, the tribes were scattered from the Bighorn Mountains on the west to the Black Hills on the east. They were so sure that the region was beyond the reach of the Bluecoats that most of them were skeptical when they heard rumors of soldiers coming at them from four directions.

But the rumors were true.

Brigadier General Patrick E. Connor had announced in July that the Indians north of the Platte River “must be hunted like wolves.” He organized three columns of soldiers for an invasion of the Powder River country. One column, commanded by Colonel Nelson Cole, would march from Nebraska to the Black Hills of Dakota. A second column, under Colonel Samuel Walker, would move straight north from Fort Laramie to link up with Cole in the Black Hills. The third column, with Connor himself in command, would head in a northwesterly direction along the Bozeman Trail toward Montana. General Connor thus hoped to trap the Indians between his column and the combined forces of Cole and Walker. He warned his officers to accept no offers of peace from the Indians, and ordered bluntly, “Attack and kill every male Indian over twelve years of age.”

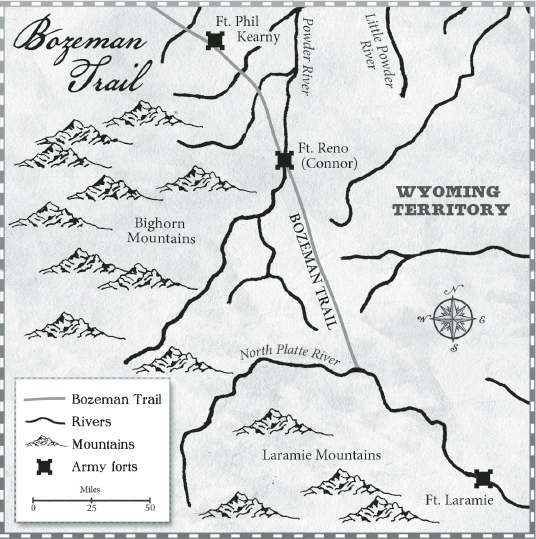

This map of the Powder River basin shows the Bozeman Trail and the two forts, Reno (built in 1865) and Phil Kearny (built in 1866), that were the cause of Red Cloud’s War.

In the beginning of August, the three columns set off. If everything went according to plan, they would rendezvous about September 1 on the Rosebud River in the heart of hostile Indian country.

A fourth group, which had no connection with Connor’s plans, was also approaching the Powder River country from the east. Organized by a civilian, James A. Sawyers, to open a new overland route, this expedition had no other objective than to reach the Montana gold fields. Because Sawyers knew he would be trespassing on Indian treaty lands, he expected resistance and therefore had obtained two companies of infantrymen to escort his group of 73 gold seekers and 80 wagons of supplies.

It was mid-August when the Sioux and Cheyenne who were camped along the Powder River learned of Sawyers’s approaching wagon train. The son of a Cheyenne mother and a white father, George Bent, who chose to live among his mother’s people, recalled afterward, “Our village crier, a man named Bull Bear, mounted and rode about our camp, crying that soldiers were coming…. Everybody ran for ponies.”

About 500 Sioux and Cheyenne were in the war party. Leading the Sioux was an Oglala chief who would become famous for his war against the Bluecoats. His name was Mahpiua-luta, but he was known to the whites as Red Cloud. Leading the Cheyenne was their great chief Tamilapesni, or Dull Knife. The chiefs were very angry that soldiers had come into their country without asking permission.

Brigadier General Patrick E. Connor would try to blame subordinates for his failures during the Powder River campaign. [LOC, DIG-cwpb-06318]

An undated photograph of Red Cloud in ceremonial dress. Red Cloud is considered one of the greatest American Indian diplomats. [LOC, USZ62-91032]

When they sighted the wagon train, it was moving along between two hills with a herd of about 300 cattle following behind. The Indians divided and spread out along opposite ridges and, at a signal, began firing upon the soldier escorts. In a few minutes the train formed a circular corral with the cattle herded inside.

For two or three hours, the warriors harassed the soldiers by creeping down gullies and suddenly opening fire at close range. A few of the more daring riders galloped in close, circled the wagons, and then swept out of range. After the soldiers started firing their two howitzers, the warriors kept behind hillocks, uttering war cries and shouting insults.

The wagon train could not move, but neither could the Indians get at it. About midday, to end the stalemate, the chiefs ordered that a white flag be raised.

A meeting was quickly arranged. George Bent and his brother Charlie were the interpreters for Red Cloud and Dull Knife. Colonel Sawyers and Captain George Williford came out with a small escort. (Colonel Sawyers’s rank was honorary, but he considered himself in command of the wagon train. Captain Williford’s rank was genuine.)

When Red Cloud demanded an explanation for the presence of soldiers in the Indians’ country, Captain Williford replied by asking why the Indians had attacked peaceful white men. Sawyers protested that he had not come to fight Indians. He was seeking a short route to the Montana gold fields and wanted only to pass through the country.

George Bent said afterward, “Red Cloud replied if the whites would go clear out of his country and make no roads it was all right. Dull Knife said the same for the Cheyenne; then both chiefs said for the officer [Williford] to take the [wagon] train due west from this place, then turn north, and when he had passed the Bighorn Mountains, he would be out of their country.”

Sawyers again protested. To follow such a route would take him too far out of his way. He said he wanted to move north along the Powder River valley to find a fort that General Connor was building there.

This was the first that Red Cloud and Dull Knife had heard of General Connor and his invasion. They expressed surprise and anger that soldiers would dare build a fort in the heart of their hunting grounds. Seeing that the chiefs were growing hostile, Sawyers quickly offered them a wagonload of goods. Red Cloud suggested that gunpowder and ammunition be added to the list, but Captain Williford objected strongly. In fact, he was opposed to giving the Indians anything.

Finally the chiefs agreed to accept the goods in exchange for granting permission for the wagon train to pass through. After this had been done, the wagon train went on its way. It was later harassed for several days by a second band of Sioux that also demanded goods but was refused.

Meanwhile, Red Cloud and Dull Knife and their warriors had left to confirm the rumors of soldiers building a fort on the Powder River.

In fact, Star Chief Connor had already started construction of a stockade about sixty miles south of the Crazy Woman Fork and named it in honor of himself, Fort Connor.

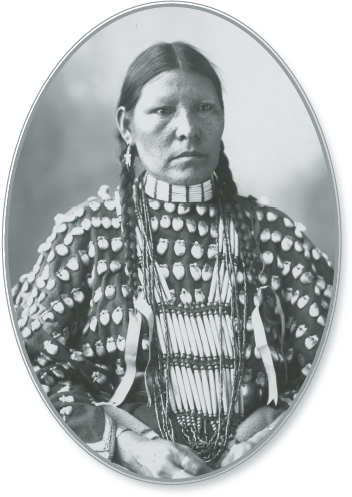

An Edward Curtis photograph taken in 1910 of a young Arapaho woman. [LOC, USZ62-97843]

On August 22, General Connor decided that the stockade on the Powder River was strong enough to be held by one cavalry company. Leaving most of his supplies there, he led the rest of his men on a forced march, a rapid advance with little rest. They moved northwest toward the Tongue River valley in order to find as quickly as possible any large concentrations of Indian lodges. This group included a number of Pawnee scouts, since the Pawnee were longtime enemies of the Sioux and Arapaho. Had General Connor moved north along the Powder River, he would have found thousands of Red Cloud’s and Dull Knife’s warriors searching for Connor’s soldiers and eager for a fight.

About a week after Connor’s column left the Powder River, a Cheyenne warrior named Little Horse was traveling through this same area with his wife and young son. Little Horse’s wife was an Arapaho woman, and they were making a summer visit to see her relatives at Black Bear’s Arapaho camp on the Tongue River. One day, a pack on his wife’s horse got loose. When she dismounted to tighten it, she happened to glance back across a ridge. A line of mounted men was coming along the trail far behind them.

An 1898 Frank A. Rinehart photograph of an Arapaho woman named Freckled Face in ceremonial dress. [LOC, DIG-ppmsca-15854]

“Look over there,” she called to Little Horse.

“They’re soldiers!” Little Horse cried. “Hurry!”

As soon as they were over the next hill and out of view of the soldiers, they turned off the trail. Little Horse cut loose from a packhorse the poles of the travois on which his young son was riding, took the boy on behind him, and they rode fast—straight for Black Bear’s camp. They came galloping in, disturbing the peaceful village of 250 lodges pitched on a mesa above the river. The Arapaho were rich in ponies that year. Three thousand were corralled along the stream.

None of the Arapaho believed that soldiers could be within hundreds of miles. When Little Horse’s wife tried to get the crier to warn the people, he said, “Little Horse has made a mistake; he just saw some Indians coming over the trail, and nothing more.” Certain that the horsemen they had seen were soldiers, Little Horse and his wife hurried to find her relatives. Her brother, Panther, was resting in front of his tepee. They told him that soldiers were coming. “Pack up whatever you wish to take along,” Little Horse said. “We must go tonight.”

Panther laughed. “You’re always getting frightened and making mistakes about things,” he said. “You saw nothing but some buffalo.”

“Very well,” Little Horse replied, “you need not go unless you want to, but we shall go tonight.” His wife managed to persuade some of her other relatives, and before nightfall they left the village and moved several miles down the Tongue River.

Meanwhile, some Pawnee scouts under the command of General Connor’s subordinate, Captain Frank North, found the Arapaho camp and reported it to Connor. Early the next morning, Star Chief Connor’s soldiers prepared to attack. By chance, a warrior who had taken one of his racehorses out for a run happened to see the troops assembling behind a ridge. He galloped back to camp as fast as he could and raised a warning.

A 1908 Edward Curtis photograph of an Atsina Indian on a horse pulling a travois. The Atsinas, also called the Gros Ventre, lived in north-central Montana and were distant neighbors of the Sioux. The travois was the system Plains Indians used to carry their possessions. [LOC, USZ62-97842]

Moments later, at the sound of a bugle and the blast of a howitzer, 80 Pawnee scouts and 250 of Connor’s cavalrymen charged the village from two sides. The village suddenly became a scene of fearsome activity—horses rearing and whinnying, dogs barking, women screaming, children crying, warriors and soldiers yelling and cursing. The Pawnee swerved toward the 3,000 ponies, which the Arapaho herders were desperately trying to scatter along the river valley.

As quickly as they could, the Arapaho mounted ponies and retreated up Wolf Creek, the soldiers chasing them. For 10 miles the Arapaho retreated. When the soldiers’ horses tired, the warriors turned on them, shooting their old muskets and bows and arrows. By early afternoon Black Bear and his warriors had pushed Connor’s cavalrymen back to the village. But artillerymen had mounted two howitzers there, and the big-talking guns filled the air with whistling pieces of metal, forcing the Arapaho to stop.

While the Arapaho watched from the nearby hills, the soldiers tore down all the lodges in the village. They heaped poles, tepee covers, buffalo robes, blankets, furs, and piles of dried meat called pemmican into great mounds and set fire to them. Everything the Arapaho owned went up in smoke. Then the soldiers and the Pawnee mounted up and went away with 1,000 Arapaho ponies they had captured.

The Arapaho had nothing left except the ponies they had saved from capture, a few old guns, their bows and arrows, and the clothing they were wearing when the soldiers charged into the village. This was the Battle of Tongue River that happened in the Moon When the Geese Shed Their Feathers (August).

Star Chief Connor then marched on toward the Rosebud River, searching for more Indian villages to destroy. As he neared the rendezvous point on the Rosebud, he sent scouts out in all directions to look for the other two columns of his expedition. No trace could be found of either one, and they were a week overdue. On September 9, Connor ordered Captain North to lead his Pawnee mercenaries in a forced march to the Powder River in hopes of intercepting the columns. On the second day the group ran into a blinding sleet storm. Two days later, they found where Cole and Walker had recently camped. The ground was covered with 900 dead horses. Nearby were charred pieces of metal buckles, stirrups, and rings—the remains of saddles and harnesses. Captain North was uncertain what to make of this evidence of a disaster. He immediately turned back to report to General Connor.

Later they learned what had happened.

On August 18 the two columns under Cole and Walker had joined along the Belle Fourche River in the Black Hills. Though the 2,000-man force was strong in numbers, in almost every other respect, it was weak. The soldiers’ spirits were low. Before leaving Fort Laramie, the men in one of Walker’s regiments mutinied. Only after they were threatened with cannon fire did they agree to march. In addition, the troops had not brought enough food. By late August, rations for the combined columns were so short that they began slaughtering mules for meat. A disease called scurvy broke out among the men. Because of the shortage of grass and water, their horses grew weaker and weaker. With men and horses in such condition, neither Cole nor Walker had any desire to fight Indians. They only wanted to reach the Rosebud River and rendezvous with General Connor.

As for the Indians, most were busy in the sacred places of Paha Sapa, the Black Hills, with their Sun Dances and other religious ceremonies. A few kept watch over the soldiers and reported the Bluecoats’ movements. All were angry with the soldiers who trespassed on the sacred soil. But because they were busy with their ceremonies, at first they did not send out any war parties. That soon changed.

An Edward Curtis photograph of Cheyennes constructing a Sun Dance lodge in 1910. The Sun Dance is the most important religious ceremony conducted by the Plains Indians and is held during the summer. [LOC, USZ62-106279]

On August 28, when Cole and Walker reached the Powder River, they sent scouts to the Tongue and Rosebud rivers to find General Connor, but he was still far to the south. After their scouts returned, the two commanders put their men on half rations and decided to start moving south before starvation brought disaster. What they did not know was that they were being followed. By September 1, nearly 400 Hunkpapa and Minneconjou Sioux warriors were shadowing them. With them was the Hunkpapa leader, Sitting Bull.

When the Sioux war party discovered the soldiers camped in the woods along the Powder, several of the young men wanted to ride in under a truce flag and see if they could persuade the Bluecoats to give them a peace offering. Sitting Bull did not trust white men and was opposed to such begging, but he let the others send a truce party.

The soldiers waited until the Sioux truce party came within easy rifle range and then fired, killing and wounding several before they could escape. On their way back, the survivors made off with several horses from the soldiers’ herd.

After looking at the gaunt horses, Sitting Bull decided that 400 Sioux on their fleet-footed mustangs should be an equal match for 2,000 soldiers on such half-starved Army mounts. Most of the other warriors agreed.

Riding down to the camp single file, the Sioux encircled the soldiers guarding the horse herd and began picking them off one by one until a company of cavalrymen came charging up the bank of the Powder. The Sioux quickly withdrew on their fast ponies, keeping out of range until the Bluecoats’ bony mounts began to falter. Then they turned on their pursuers.

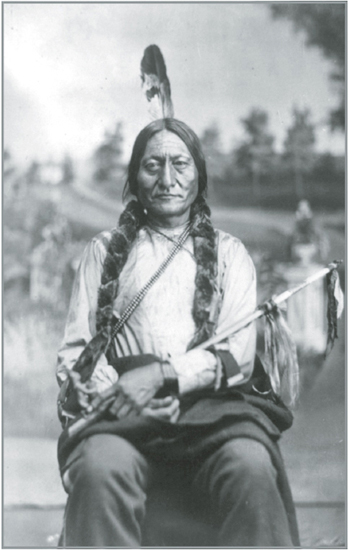

This photograph by Orlando Scott Goff shows Sitting Bull in 1881. Goff became famous for his many photographic portraits of Sitting Bull. [LOC, USZ62-12277]

After a few minutes, the soldiers re-formed their ranks, and at the sound of a bugle came charging after the Sioux again. Once more the swift mustangs carried the Sioux warriors out of range. The Indians then scattered, causing the frustrated soldiers to halt. This time the Sioux turned and attacked from all sides. Sitting Bull captured a black stallion.

Alarmed by the Indian attack and fearing worse, the Eagle Chiefs Cole and Walker formed their columns for a forced march southward along the Powder River. For a few days the Sioux followed the soldiers, scaring them by appearing suddenly on ridgetops or making little attacks against the rear guard. Sitting Bull and the other leaders laughed at how frightened the Bluecoats became.

When a big sleet storm struck, the Indians took shelter for two days. At one point they heard scattered firing from the direction of the soldiers’ camp. The next day they found the soldiers’ abandoned camp. Dead horses were everywhere. The soldiers had shot them because they could not make them go any farther.

Since many of the frightened Bluecoats were now on foot, the Sioux decided to keep following them and drive them so crazy with fear they would never return to the Black Hills. Along the way, these Hunkpapas and Minneconjous began meeting small scouting parties of Oglala Sioux and Cheyennes who were looking for Star Chief Connor’s column. There was great excitement in these meetings. Only a few miles south was a large Cheyenne village, and as runners brought the leaders of the bands together, they began planning a big ambush for the soldiers.

The Cheyenne warrior Woqini, known to whites as Roman Nose, was never a chief. But he was regarded by both Indians and whites as one of the greatest warriors of the Plains tribes. Like Red Cloud and Sitting Bull, he was determined to fight for his country. Roman Nose also believed he had powerful protection in battle. It was a warbonnet filled with so many eagle feathers that when he was mounted, the warbonnet trailed almost to the ground. As long as Roman Nose also did not touch anything made by white men or eat anything cooked with white men’s utensils before he went into battle, when he wore this warbonnet, the white man’s bullets would not touch him.

In September, when the Cheyenne camp first heard about the soldiers fleeing south up the Powder River, Roman Nose asked for the privilege of leading a charge against the Bluecoats. A day or two later, the soldiers were camped in a bend of the river, with high bluffs and thick timber on both sides. Deciding that this was an excellent place for an attack, the chiefs brought several hundred warriors into position all around the camp. They began the fight by sending small decoy parties in to draw the soldiers out of their wagon corral. But the soldiers would not come out.

In 1907, Sioux chief High Hawk was photographed in ceremonial dress by Edward Curtis. He is wearing a warbonnet and holding a coup stick. French fur traders gave the coup stick its name. The word coup is French for “blow” or “strike.” For Native Americans, going to war was a major test of manhood. One way a young warrior demonstrated his courage was by “counting coup”—using a coup stick to hit an enemy. This was a highly respected act of bravery because it meant you were close enough to your enemy to risk capture. [LOC, USZ62-48426]

Then Roman Nose rode up on his white pony, his warbonnet trailing behind him, his face painted for battle. He called to the Cheyenne warriors not to fight singly as they had always done but to fight together as the soldiers did. The warriors maneuvered their ponies into a line facing the soldiers, who were standing in formation before their wagons. Roman Nose danced his white pony in front of his warriors, telling them to hold fast until he had emptied the soldiers’ guns. Then he slapped the pony into a run and rode straight as an arrow toward one end of the line of soldiers. When he was close enough to see their faces clearly, he turned and rode fast along the length of the soldiers’ line. They emptied their guns at him all along the way. At the end of the line, he wheeled the white pony and rode back along the soldiers’ front again.

“He made three, or perhaps four, rushes from one end of the line to the other,” said George Bent, the half-breed Cheyenne. “And then his pony was shot and fell under him. On seeing this, the warriors set up a yell and charged. They attacked the troops all along the line, but could not break through anywhere.”

Roman Nose had lost his horse, but his protective medicine saved his life. He also learned some things that day about fighting Bluecoats—and so did Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Dull Knife, and the other leaders. Bravery, numbers, massive charges—they all meant nothing if the warriors were armed only with bows, lances, clubs, and old trade muskets. The soldiers had modern repeating rifles and the support of howitzers.

For several days after the fight—which would be remembered by the Indians as Roman Nose’s Fight—the Cheyenne and Sioux continued to harass the soldiers. The Bluecoats were now barefoot and in rags, and they had nothing left to eat but their bony horses, which they devoured raw because the Indians gave them no time to stop and build fires. At last toward the end of the Drying Grass Moon (September), Star Chief Connor’s returning column arrived to rescue Cole’s and Walker’s beaten soldiers. The soldiers all camped together around the stockade at Fort Connor on the Powder River until messengers from Fort Laramie arrived with orders recalling all troops except for two companies, which were to remain at Fort Connor, renamed Fort Reno in November 1865.

General Connor had left the companies six howitzers to help defend their stockade. Red Cloud and the other leaders studied the fort from a distance. They knew they had enough warriors to storm the stockade, but too many would die under the showers of shot hurled by the big guns. They finally agreed upon a strategy of holding the soldiers prisoners in their fort all winter and cutting off their supplies from Fort Laramie.

Before that winter ended, half the luckless troops in the fort were dead or dying of scurvy, malnutrition, and pneumonia. Many slipped away and deserted, taking their chances with the Indians outside.

As for the Indians, all except the small bands of warriors needed to watch the fort moved over to the Black Hills, where plentiful herds of antelope and buffalo kept them well fed and comfortable in their warm lodges. Through the long winter evenings, the chiefs recounted the events of Star Chief Connor’s invasion. Because the Arapaho had been overconfident and careless, they had lost a village, many lives, and part of their rich pony herd. The other tribes had lost a few lives but no horses or lodges. They had captured horses and mules carrying U.S. brands. They had taken cavalry rifles, saddles, and other equipment from the soldiers. Above all, they had gained a new confidence in their ability to drive the Bluecoat soldiers from their land.

“If white men come into my country again, I will punish them again,” Red Cloud said, but he knew that unless he could somehow obtain many new guns like the ones they had captured from the soldiers, and plenty of ammunition for the guns, the Indians could not go on punishing the soldiers forever.