When people come to trouble, it is better for both parties to come together without arms and talk it over and find some peaceful way to settle it.

—SPOTTED TAIL OF THE BRULÉ SIOUX

The Fetterman Massacre made a profound impression upon the United States government. It was the worst defeat the army had yet suffered in Indian warfare. Carrington was recalled from command, reinforcements were sent to the forts in the Powder River country, and a new peace commission was dispatched from Washington to Fort Laramie in 1867.

The new commission was headed by John Sanborn, an experienced negotiator with Indians and known to them as Black Whiskers. Sanborn and General Alfred Sully arrived at Fort Laramie in the Geese Laying Moon (April). Their mission was to persuade Red Cloud and the Sioux to give up their hunting grounds on the Powder River country and live on a reservation. As in the previous year, the Brulés were the first to arrive—Spotted Tail, Swift Bear, Standing Elk, and Iron Shell.

Little Wound and Pawnee Killer, Oglala leaders who had brought their bands down to the Platte River in hopes of finding buffalo, came to see what gifts the commissioners might be handing out. Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses arrived as a representative for Red Cloud. When the commissioners asked him if Red Cloud was coming to talk peace, Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses replied that the Oglala leader would not talk about peace until all soldiers were removed from the Powder River country.

A steam locomotive. [LOC, DIG-stereo-1s00612]

During these parleys, Sanborn asked Spotted Tail to address the assembled Indians. Spotted Tail advised his listeners to abandon warfare with the white men and live in peace and happiness. For this, he and the Brulés received enough ammunition to go on a buffalo hunt. The hostile Oglalas received nothing. Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses returned to join Red Cloud, who had already resumed raiding along the Bozeman Trail. Little Wound and Pawnee Killer followed the Brulés to the buffalo ranges. Black Whiskers Sanborn’s peace commission had accomplished nothing.

In their search for buffalo and antelope, the Oglalas and Cheyenne crossed railroad tracks several times that summer. Sometimes they saw Iron Horses (locomotives) dragging wooden houses on wheels at great speed along the tracks. They puzzled over what could be inside the houses, and one day a Cheyenne decided to rope one of the Iron Horses and pull it from the tracks. Instead, the Iron Horse jerked him off his pony and dragged him unmercifully before he could get loose.

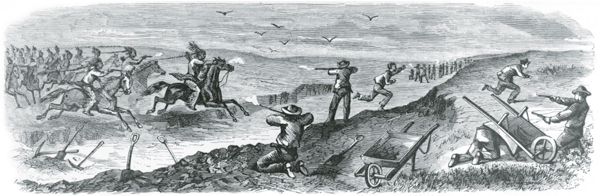

An 1867 Harper’s Weekly woodcut illustrating an attack by Cheyenne warriors on a work crew building a railroad track. Though war parties repeatedly attacked railroad work crews, they were unable to stop the construction of railroad lines through their land. [LOC, USZ62-115324]

One of the warriors in the group, Sleeping Rabbit, suggested they try another way to catch one of the Iron Horses. “If we could bend the track up and spread it out, the Iron Horse might fall off,” he said. “Then we could see what is in the wooden houses on wheels.” They did this and waited for the train. Eventually one arrived and, as Sleeping Rabbit said, once the locomotive ran over the section where the rails had been removed, it tumbled over onto its side. Huge clouds of smoke and steam poured out of the wrecked locomotive. Men came running from the train, and the Indians killed all but two, who escaped. Then the Indians broke open the houses on wheels and found sacks of flour, sugar, and coffee; boxes of shoes; and other items. After a while the Indians took hot coals from the wrecked engine and set the boxcars on fire. Then they rode away.

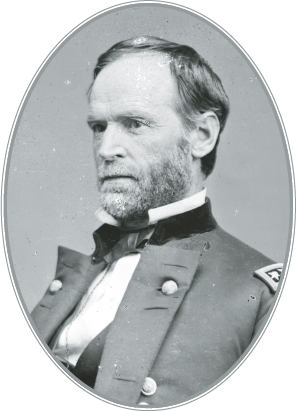

Incidents such as this, together with Red Cloud’s continuing war, brought travel by settlers and other civilians to an end through the Powder River country. The government was determined to protect the route of the Union Pacific Railroad. But even the chief army general William Tecumseh Sherman, called Great Warrior Sherman by the Indians, was beginning to wonder if it might not be advisable to leave the Powder River country to the Indians in exchange for peace along the Platte Valley.

Late in July 1867, after holding their Sun Dances and medicine-arrow religious ceremonies, the Sioux and Cheyenne decided to wipe out one of the forts on the Bozeman Trail. Red Cloud wanted to attack Fort Phil Kearny, but Dull Knife and Two Moon thought it would be easier to take Fort C. F. Smith because Cheyenne warriors had already killed or captured nearly all the soldiers’ horses there. Finally, after the chiefs could reach no agreement, the Sioux said they would attack Fort Phil Kearny, and the Cheyenne went north to Fort C. F. Smith.

On August 1, some 500 or 600 Cheyenne warriors caught 30 soldiers and civilians in a hayfield about two miles from Fort C. F. Smith. The defenders were armed with new Springfield repeating rifles, which the Cheyenne had not yet seen. When the warriors charged the soldiers’ log corral, they met such a heavy barrage of rifle fire that only one warrior was able to penetrate the fortifications, and he was killed. The Cheyenne then set ablaze the high dry grass around the corral.

This was enough for the Cheyenne that day. Many warriors sustained bad wounds from the rapidly firing guns, and about 20 were dead. They started back south to see if the Sioux had had any better luck at Fort Phil Kearny.

The Sioux had not. After making several fake attacks around the fort, Red Cloud decided to use the decoy trick that had worked so well with Captain Fetterman. Crazy Horse would attack the woodcutters’ camp, and when the soldiers came out of the fort, High Back Bone would swarm down on them with 800 warriors. Crazy Horse and his decoys carried out their assignment perfectly, but for some reason, several hundred warriors rushed out of concealment too soon, warning the soldiers of their presence.

To salvage something from the fight, Red Cloud turned the attack against the woodcutters, who had taken cover behind a corral of 14 wagon beds reinforced with logs. Several hundred mounted warriors made a circling approach, but these defenders were also armed with Springfields. Faced with rapid and continuous fire from the new weapons, the Sioux quickly pulled their ponies out of range.

The Indians considered neither the Hayfield nor the Wagon Box battles, as they were later called, a defeat. Although some soldiers may have thought of the fights as victories, the United States government did not. Only a few weeks later, General Sherman himself was traveling westward with a new peace council. This time the military authorities were determined to end Red Cloud’s war by any means short of surrender.

In the late summer of 1867, Spotted Tail received a message from Nathaniel Taylor, the commissioner responsible for negotiating a treaty with the warring tribes. The Brulés had been roaming peacefully below the Platte, and the commissioner asked Spotted Tail to inform as many Plains chiefs as possible that ammunition would be issued to all friendly Indians sometime during the Drying Grass Moon (September). The chiefs were to assemble at the end of the Union Pacific Railroad track, which was then in western Nebraska. Great Warrior Sherman and six new peace commissioners would come there on the Iron Horse to parley with the chiefs and discuss how to end Red Cloud’s war.

Spotted Tail sent for Red Cloud, but the Oglala chief again declined, sending Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses to represent him. Though not a chief, the respected Oglala warrior Pawnee Killer agreed to go. The Cheyenne chief Turkey Leg said he would attend. The two Brulé chiefs, Swift Bear and Standing Elk, as well as Big Mouth and other Laramie Loafers also made the trip. Several other Brulé chiefs responded to the invitation as well.

On September 19, a shiny railroad car arrived at Platte City station, and Great Warrior Sherman, Commissioner Taylor, Major General William S. Harney, known to the Indians as White Whiskers Harney, Black Whiskers Sanborn, and others stepped out.

Commissioner Taylor began the proceedings. “We are sent out here to inquire and find out what has been the trouble. We want to hear from your own lips your grievances and complaints. My friends, speak fully, speak freely, and speak the whole truth…. War is bad, peace is good. We must choose the good and not the bad…. I await what you have to say.”

Spotted Tail replied, “The Great Father has made roads stretching east and west. Those roads are the cause of all our troubles…. The country where we live is overrun by whites. All our game is gone. This is the cause of great trouble. I have been a friend of the whites, and am now…. If you stop your roads, we can get our game. That Powder River country belongs to the Sioux…. My friends, help us; take pity on us.”

On the following day, Sherman addressed the chiefs, blandly assuring them that he had thought of their words all night and was ready to give a reply. “The Powder River road was built to furnish our men with provisions,” he said. “The Great Father thought that you consented to give permission for that road at Laramie last spring, but it seems that some of the Indians were not there and have gone to war.”

Subdued laughter from the chiefs may have surprised Sherman, but he went on, his voice taking a harsher tone. “While the Indians continue to make war upon the road, it will not be given up. But if, on examination, at Laramie in November, we find that the road hurts you, we will give it up or pay for it. If you have any claims, present them to us at Laramie.”

Sherman launched into a discussion of the Indians’ need for land of their own, advised them to give up their dependence upon wild game, and then he dropped a thunderbolt: “We therefore propose to let the whole Sioux nation select their country up the Missouri River, embracing the White Earth and Cheyenne rivers, to have their lands like the white people, forever, and we propose to keep all white men away except such agents and traders as you may choose.”

General William Tecumseh Sherman, commander in chief of the U.S. Army during the Sioux wars. Sherman was born and raised in Ohio, not far from where the Shawnee chief Tecumseh was born. Sherman’s father was a great admirer of Tecumseh and, out of respect for the Shawnee leader, made Tecumseh his son’s middle name. [LOC, DIG-cwpbh-00593]

As these words were translated, the Indians expressed surprise. So this was what the new commissioners wanted them to do—pack up and move far away to the Missouri River! For years the Teton Sioux had been following wild game westward; why should they go back to the Missouri to starve? Why could they not live in peace where game could still be found? Had the greedy eyes of the white men already chosen these bountiful lands for their own?

During the remainder of the discussions, the Indians were uneasy. Swift Bear and Pawnee Killer made friendly speeches in which they asked for ammunition, but the meeting ended in an uproar when Great Warrior Sherman proposed that only the Brulés should receive ammunition. When Commissioner Taylor and White Whiskers Harney pointed out that all the chiefs had been invited to the council with the promise of hunting ammunition, Sherman withdrew his opposition, and small amounts of ammunition were given to the Indians.

Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses wasted no time in returning to Red Cloud’s camp on the Powder River. If Red Cloud had had any intention of meeting the new peace commissioners at Laramie during the Moon of Falling Leaves (November), he changed his mind after hearing his representative’s report.

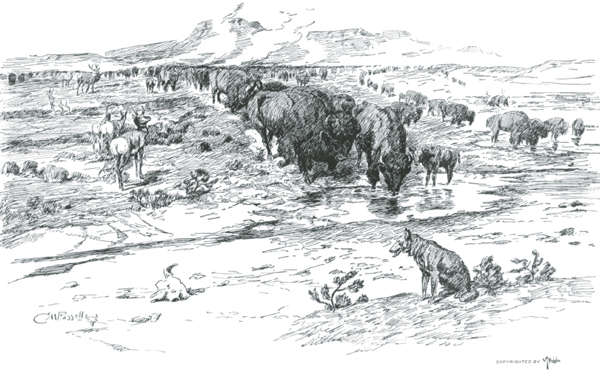

On November 9, when the commissioners arrived at Fort Laramie, they found only a few Crow chiefs waiting to meet with them. The Crows were friendly, but one of them—Bear Tooth—made a surprising speech in which he condemned all white men for their reckless destruction of wildlife and the natural environment:

Fathers, your young men have devastated the country and killed my animals, the elk, the deer, the antelope, my buffalo. They do not kill them to eat them; they leave them to rot where they fall. Fathers, if I went into your country to kill your animals, what would you say? Should I not be wrong, and would you not make war on me?

Nature’s Cattle, an 1899 illustration of buffalo and antelope by Charles M. Russell. Millions of buffalo roamed the prairie for centuries. Between 1868 and 1881, white hunters killed about 31 million. By 1890, buffalo were almost extinct. [LOC, USZ62-115203]

A few days after the commissioners’ meeting with the Crows, messengers arrived from Red Cloud. He would come to Laramie to talk peace, he informed the commissioners, as soon as the soldiers withdrew from the forts on the Powder River road. The war, he repeated, was being fought for one purpose—to save the valley of the Powder, the only hunting ground left his nation, from intrusion by white men.

For the third time in two years, a peace commission had failed. Before the commissioners returned to Washington, however, they sent Red Cloud a shipment of goods with another plea to come to Laramie as soon as the winter snows melted in the spring. Red Cloud politely replied that he had received the peace offering and that he would come to Laramie as soon as the soldiers left his country.

In the spring of 1868, Great Warrior Sherman and the same peace commission returned to Fort Laramie. This time they had firm orders from an impatient government to abandon the forts on the Powder River road and obtain a peace treaty with Red Cloud. This time they sent a special agent from the Office of Indian Affairs to personally invite the Oglala leader to a peace signing. Red Cloud told the agent he would need about 10 days to consult with his allies and would probably come to Laramie during May, the Moon When the Ponies Shed.

Only a few days after the agent returned to Laramie, however, a message arrived from Red Cloud: “We are on the mountains looking down on the soldiers and the forts. When we see the soldiers moving away and the forts abandoned, then I will come down and talk.”

This was all very humiliating to Great Warrior Sherman and the commissioners. They managed to obtain the signatures of a few minor chiefs who came in for presents, but as the days passed, the frustrated commissioners quietly departed one by one for the East. By late spring, only Black Whiskers Sanborn and White Whiskers Harney were left to negotiate. Red Cloud and his allies remained on the Powder through the summer, keeping a close watch on the forts and the road to Montana.

At last the reluctant War Department issued orders for the abandonment of the Powder River forts. On July 29, the troops at Fort C. F. Smith packed their gear and started marching southward. Early the next morning, Red Cloud led a band of celebrating warriors into the post, and they set fire to every building. Fort Phil Kearny was abandoned a month later, and the honor of burning it was given to the Cheyenne under Little Wolf. A few days after that, the last soldier departed from Fort Reno, and the Powder River road was officially closed.

After two years of resistance, Red Cloud had won his war. For a few more weeks, he kept the treaty makers waiting, and then on November 6, surrounded by an escort of triumphant warriors, he came riding into Fort Laramie. Now a conquering hero, he would sign the treaty: “From this day forward all war between the parties to this agreement shall forever cease. The government of the United States desires peace, and its honor is hereby pledged to keep it. The Indians desire peace, and they now pledge their honor to maintain it.”

That peace, and the respect for Sioux and Cheyenne land, would last only four years.