Note to the Reader

Note to the Reader Note to the Reader

Note to the ReaderWHEN EXPLORER CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS landed on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola in 1492, he thought he had succeeded in reaching his goal of India. As a result, he called the natives he met “Indians.” Even after he and other explorers discovered that they had actually found a new continent, the name stuck. In the late 20th century, the term Native Americans became a popular replacement in an effort to help correct this historical wrong. Today both names are used, a practice that is repeated here in Saga of the Sioux.

Misnaming errors also extended to the names of tribes and people. Two common reasons for this were the varied skills of the translators, and the prejudices of the people receiving the translation. For instance, Sioux is an English corruption of a French word based on a name used by the Sioux’s old enemies the Ojibwa (you’ll learn more about this here). The most famous example of an individual being misnamed is the Sioux chief Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses. He was not afraid of his own horses. A more accurate translation would have been They-Fear-Even-His-Horses—meaning he was so dangerous in battle that just the sight of his horse inspired fear in his enemies. Perhaps if the original translator had recorded his name as Men-Afraid-of-His-Horses, he would have avoided creating such a misimpression.

Spellings of Native American names may also differ among sources due to the challenge of documenting nonwritten languages.

Undoing the errors of centuries is beyond the power of this one book. For the sake of clarity and comprehension, the well-known names such as Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses and others are used in this text, and their spellings follow Dee Brown’s original book.

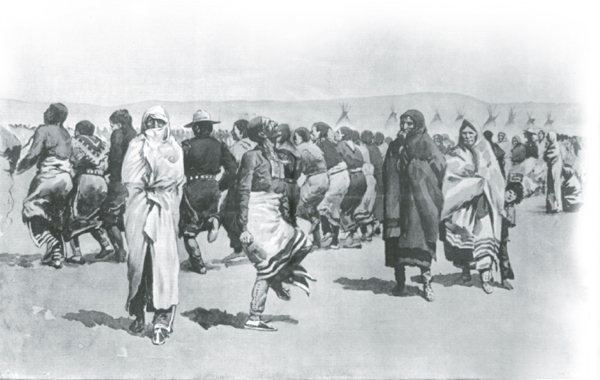

A Ghost Dance ceremony. [LOC, USZ62-3726]