CHAPTER THREE

THE NEW FRONTIER

(1961–1963)

JOHN KENNEDY CONVEYED a sense of confidence and ease as he strode to the podium. The youngest man ever elected president, Kennedy had not yet been in office for three months. Seated before him in the large State Department auditorium were more than four hundred journalists. Present in the room as well were three very large TV cameras. Today’s presidential news conference would be broadcast on live network television, as had become the custom in this new administration. Never attempted in the Eisenhower years, these afternoon exchanges between the president and the press were a new attraction, occurring nearly every other week, preempting afternoon soap operas and game shows.

Kennedy’s apparent comfort before the cameras that afternoon gave little indication that the days ahead would define his presidency and greatly affect the course of the twentieth century. But April 12, 1961, had begun with extraordinary news. That morning the Soviet Union had announced the successful launch and return of the Vostok 1 spacecraft, carrying cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, the first human to enter outer space and orbit the Earth.

The news was electrifying yet not entirely unexpected. For the past few days American intelligence sources had been predicting that the Russians might attempt such a feat. A few hours before the news conference began, viewers in Europe had seen the first live television images ever broadcast from inside the Soviet Union. A somewhat blurry transmission from Moscow presented a carefully orchestrated display in which Gagarin stepped from an airplane and strode across a red carpet toward a jubilant and beaming Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. The two men were then seen proceeding in a motorcade to a massive celebration in Red Square.

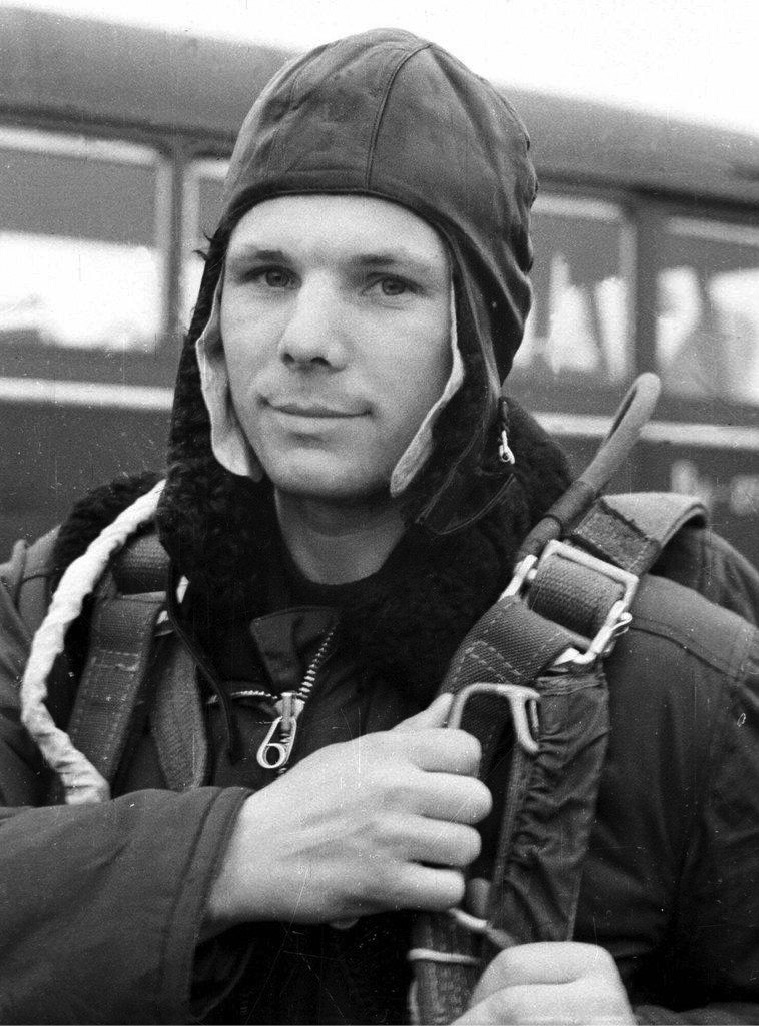

The face of Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin as reproduced on newspaper front pages around the world when he became the first human to travel into space on April 12, 1961. It was likely this photograph that caused Arthur C. Clarke to compare him to a modern-day Charles Lindbergh.

In Washington, however, journalists were even more concerned with another subject: Cuba. Following the revolution two years earlier that had overthrown dictator Fulgencio Batista, American relations with the government of Fidel Castro had deteriorated badly. The United States broke off all diplomatic ties with Cuba only days before Kennedy was inaugurated. In one of his first actions, the new president approved a CIA plan for an armed invasion of this island nation, which he was assured would be carried out in such a manner that American involvement would remain entirely hidden. But in early April, newspapers reported that the United States was training an anti-Castro military unit in a remote Guatemalan base. This prompted the first question from one of the assembled journalists, asking Kennedy not about the Soviet launch but rather how far the United States was willing to go to assist an anti-Castro invasion. Kennedy’s careful response attempted to define the current situation as a conflict between opposing Cuban factions, with added assurance that under no circumstance would any American armed forces intervene militarily in Cuba.

Considering the tension of the moment, the second question from the State Department auditorium, about Gagarin’s flight, was far easier to answer. Calling it “a most impressive scientific accomplishment,” Kennedy announced that he had sent his congratulations to the Soviet Union and reported that the United States had previously expected that Russia would be the first to orbit a human in space. But, he added, NASA had hopes of doing likewise within the year.

However, a few minutes later—after another question about Cuba—a journalist confronted the president, noting that members of Congress and other Americans “were tired of seeing the United States second to Russia in space.” He wanted to know if additional spending would result in the United States being able to catch up and surpass the Soviet Union.

“We are behind,” Kennedy conceded. “No one is more tired than I am.” And then, after alluding to von Braun’s Saturn rocket and other very expensive advanced space projects, he said, “We are, I hope, going to go in other areas where we can be first and which will bring perhaps more long-range benefits to mankind.” He went on to speak of the importance of developing technology to desalinate salt water to provide cheap fresh water to the developing world, something he admitted was not as spectacular as a man in space or Sputnik but an accomplishment that would dwarf any other scientific feat.

BUT THE LONG-TERM beneficial implications of Russia’s achievement were not what caught the world’s attention that afternoon. Photographs of the handsome twenty-seven-year-old Yuri Gagarin soon appeared on the front page of newspapers throughout the world. Readers learned that he was the son of a carpenter and a milkmaid from a collective farm. He was described as a modest, five-foot-two-inch, hardworking, fit, quick-witted elite jet pilot, well liked by his comrades. In Ceylon, where he was now living, Arthur C. Clarke saw the photographs of Gagarin and immediately compared him to a modern-day Charles Lindbergh.

The latest issues of Time, Newsweek, and Life, with Gagarin on the cover, were appearing on newsstands across the nation as the CIA’s collaboration with anti-Castro Cuba forces went into full swing. But the Bay of Pigs operation, as it came to be known, had an outcome far different from what Kennedy had been assured would happen. And when he failed to provide the necessary air support, the invasion turned into an unmitigated disaster. Instead of a rapid removal of the Castro regime, the Kennedy administration faced a diplomatic crisis and an international public-relations nightmare. Even worse, the Soviet Union’s leaders had begun to assume America’s photogenic new president was callow and weak.

It was in the wake of these two isolated events, separated by less than a week, that the promise of space suddenly arose as a way to dramatically alter the narrative about America’s future and its standing in the international arena.

A White House staffer heard Kennedy angrily complaining in the midst of the media frenzy about Gagarin. “If somebody can just tell me how to catch up. Let’s find somebody—anybody, I don’t care if it’s the janitor, if he knows how.”

Prior to this moment, human spaceflight had not played a significant role in Kennedy’s imaginative or political thinking. Unlike Clarke and von Braun, Kennedy read no science fiction during his childhood. His bookshelf contained the classics encountered by most upper-middle-class boys his age: The Jungle Book, Kidnapped, Treasure Island, The Arabian Knights, and The Story of King Arthur and His Knights. The American pulp magazines, such as those Clarke bought from the table at the back of Woolworth’s, were not what a boy from an elite school like Choate should be seen reading. Rather, during his prep school years, young John Kennedy carried a copy of The New York Times under his arm. Reading books about space travel would have marked him as an intellectual lightweight.

Life magazine’s White House correspondent observed that the new president had a weak understanding of space policy. His science adviser, MIT professor Jerome Wiesner, recalled that Kennedy hadn’t thought much about the issue during his first few weeks in office. While von Braun had voted for JFK, hoping that he might push the United States toward an ambitious spacefaring policy, those who knew Kennedy well had never heard him discuss such thoughts.

By the time of Inauguration Day, 1961, there had already been eleven unpiloted flights to test hardware for the Mercury program—and the success rate was not good. The first flight of the Mercury Redstone the previous November had reached an altitude of four inches before the rocket settled back onto the launchpad. Kennedy’s one mention of space during his inaugural address was to suggest that “together we explore the stars,” framing such endeavors as a possible area of cooperation rather than competition. At the celebrity-studded inauguration gala, held the night before, John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson watched from their boxes as the American space program was satirized by comedians Milton Berle and Bill Dana, the latter in character as reluctant astronaut José Jiménez, a skit that became wildly popular a few months later.

Attending the gala was a thirty-four-year-old Chicago lawyer who had arrived in the capital by train a few hours earlier. Newton Minow had worked on Adlai Stevenson’s two presidential campaigns and had clerked at the Supreme Court in the early 1950s. Kennedy had asked him to serve as the administration’s new chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, an agency in need of reform after a pair of highly publicized scandals.

Like most who joined the new administration, Minow was a war veteran. He had enlisted in the Army at age seventeen and served in the Pacific during World War II. That experience had forced him to grow up quickly under unusual circumstances, a tempering that forged sobering realism with a sense of idealism and a desire to make a better world for coming generations. John Kennedy once spoke of himself as “an idealist without illusions,” a description that Minow thought succinctly summarized the generation that came to Washington to work with the new president.

Television was still a young medium, but Kennedy was aware of its power and potential. He told his new FCC commissioner that he wouldn’t have been elected without it, echoing the widely held belief that the 1960 televised debates with Vice President Nixon were a decisive factor in his victory. But television was still evolving; broadcast journalism was primarily headlines read from wire-services reports, occasionally supplemented with filmed images. The three commercial networks’ national newscasts were only fifteen minutes in length, with reception for ABC available in only about half the country.

On his first day on the job at the FCC, Minow met a senior commissioner on his new staff, an older man named T.A.M. (“Tam”) Craven, who was an engineer.

“Do you know what a communications satellite is?” the older man asked.

“No, I don’t,” Minow replied somewhat sheepishly.

Craven groaned. “I was afraid of that.” He had been trying to get Washington interested in them. “It’s the one place where we are ahead of the Russians in space,” he explained, “but I can’t get anybody to do anything about it.”

“I’ll tell you what,” Minow replied. “If you teach me, and if you are right, I promise you I’ll get on it.”

As someone who’d practically flunked physics in college, Minow was a bit daunted by this new area of study. But he sensed that it might be something important.

Craven suggested Minow read two books by Arthur C. Clarke, The Exploration of Space and The Making of a Moon: The Story of the Earth Satellite Program. He also told his boss to take a trip to Bell Labs in New Jersey to see the prototype of something they were working on called Telstar, an experimental communications satellite developed with ATT in conjunction with the national post offices of the U.K. and France. The plan was to place it in orbit over the Atlantic Ocean to relay television pictures, telephone calls, and telegraph images from one continent to the other. Minow soon learned that everything Craven had told him was indeed correct and that the Russians weren’t working on anything remotely like this. At the height of the Cold War, communications satellites were a technology that had the potential to actually bring countries closer together, providing a dramatic demonstration of how the United States could use space for peaceful purposes.

In the immediate aftermath of Gagarin’s flight and the Bay of Pigs fiasco, President Kennedy sent an April 20 memo to Vice President Johnson, directing him to recommend the best long-range American space initiative that would a) decisively surpass the Soviet Union, and b) demonstrably increase the United States’s standing in the eyes of the world. Kennedy said he was open to possible options including the construction of a space laboratory, a trip around the Moon, and an actual crewed moon landing. But weighing heavily on the fiscally conservative president was the expense of such an initiative. Estimates of between 20 and 40 billion dollars were being mentioned in the press that week. (Half a century later, this would be the modern equivalent of 140 to 280 billion dollars.)

Even before the news of the Bay of Pigs invasion broke, pressure had been building on Kennedy to counter the Soviet advances in space. NASA associate administrator Robert Seamans told the House’s Committee on Science and Astronautics only two days after Gagarin’s flight that NASA believed an emergency all-out national effort could get men to the Moon by the end of the decade, maybe as soon as 1967. But Seamans also criticized the Kennedy White House for its recent decision to cut 200 million dollars from the NASA budget for America’s piloted space program. News of Gagarin’s flight had come as a blow to others at NASA too. Robert Gilruth, the director of the Space Task Group assigned to putting the first American in space, had hoped to schedule the first piloted suborbital Mercury flight for March 1961, which would have beaten Gagarin into space. However, in this instance Gilruth had run into opposition from Wernher von Braun, who wanted one last unpiloted test of the combined Mercury Redstone before an astronaut was aboard. The missed opportunity felt like Sputnik all over again, although this time von Braun had been the voice of caution.

The press also revealed that, despite assurances that von Braun’s powerful Saturn rocket had been deemed a national priority, the government was refusing to approve paying any overtime on the project. “If we are going to get to the Moon first, then we are going to have to allow for some moonlighting,” an irritated congressman told reporters.

Questions about overtime on the Saturn project arose as Kennedy returned to face journalists at his next televised press conference, during the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs debacle. In contrast to his performance nine days earlier, the president’s delivery was defensive and uncertain. Even though he hoped to dramatically challenge the Soviet Union in space, he could make no announcement until Johnson gave him a solid recommendation and the expense could be justified.

The reporters began hammering him: “Mr. President, you don’t seem to be pushing the space program as energetically now as you suggested during the campaign. In view of the feelings of many people in this country that we must do everything we can to catch up with the Russians as soon as possible, do you anticipate applying any sort of crash program?”

“Mr. President, don’t you think we should try to get to the Moon before the Russians, if we can?”

Newspaper columnists were no less forgiving. The Pulitzer Prize–winning military editor of The New York Times declared in an opinion piece that there was an essential flaw in the nation’s space policy: a lack of urgency. He bemoaned that Kennedy appeared to be just as complacent as the Eisenhower administration had been. “So far, apparently, no one has been able to persuade President Kennedy of the tremendous political, psychological, and prestige importance, entirely apart from scientific and military results, of an impressive space achievement,” he pointed out, asserting that Soviet space accomplishments had damaged the image of American power abroad. “Only a decision at the top level that the United States will win this race [to the Moon]; only Presidential emphasis and direction will chart an American pathway to the stars.”

After receiving Kennedy’s memo, Johnson had spent three days in meetings with business leaders, Capitol Hill politicians, generals, and NASA officials to assess the feasibility of political, military, and corporate support for such a huge national undertaking. Notable among the trio of corporate businessmen Johnson had invited to these meetings was the president of CBS, the network that was to become most closely associated with television coverage of America’s space missions during the next decade.

Present, but largely silent, was the usually gregarious new administrator of NASA, James E. Webb. Webb’s appointment had been one of the last major administration positions announced by the Kennedy administration. Having little formal scientific or engineering training, Webb did not consider himself an ideal candidate for the administrator’s job. A veteran New Deal Democrat, he had been absent from Washington during the Eisenhower years, working for the oil industry in Oklahoma. By the time his name was suggested for the NASA post, it was rumored that seventeen candidates had already declined the job.

Webb noted that from the very first hour of the meetings with Johnson, the vice president was pressing to reach a consensus for a dramatic decision that he could give to Kennedy. The space-station idea was quickly eliminated, since there was a reasonable possibility that the final result would never live up to the exalted original concept; budgetary and technical constraints would likely produce something far less impressive than the initial proposal. On the other hand, the moon landing offered no possibility for half measures—either the country accomplished it or it did not. And if it could be achieved, America would demonstrate to the world it could do nearly anything in space.

Landing a man on the Moon would require an ambitious integration of the United States’s economy, educational community, and industry. It would be such a massive national undertaking that Johnson’s group of business and military advisers believed it was unlikely that the Russians could get there first. Moreover, since getting men to the Moon would require that both the Soviet Union and the United States develop an entirely new generation of heavy boosters, such an undertaking would nullify the Soviets’ earlier advantage in missile development. With von Braun’s Saturn already under way, this time the Soviets would be forced to play catch up. Von Braun’s rocket, coupled with the country’s superior industrial base and advanced technology, looked to set the stage for a realistic triumph.

On the third and final day of meetings, Johnson turned to the new NASA administrator and put him on the spot.

“Are you willing to undertake this?” Once again Webb’s response was silence. And then Johnson asked him a second time, “Are you ready to undertake it?”

Webb wasn’t concerned about developing the engineering and technology to land a man on the Moon. Rather, he was worried that the national uproar surrounding Gagarin’s flight would subside and the public’s interest would move elsewhere.

“Yes, sir,” Webb finally replied. “But there’s got to be political support over a long period of time. Like ten years. And you and the president have to recognize that we can’t do this kind of thing without that continuing support. The one factor that’s come out of all the studies we’ve made of the large systems development since World War II is that support is the most important element in success. If the people who are doing it really feel they have strong support, you have a much better chance of getting it done.”

Leaving the meeting that afternoon, Webb and his associate administrator, Robert Seamans, walked through a parking lot and across Lafayette Square to the Dolley Madison House, the temporary home of NASA’s headquarters.

Stopping for a moment in the parking lot, Webb looked at Seamans. “Are you ready to take a contract to land a man on the Moon?”

Seamans thought about it briefly and then nodded. That was it.

Within a few hours Webb got back to Johnson. “I want you to know I’m all for this. I’m ready to go. But I must repeat to you that this will require the long-term support of you and President Kennedy. Otherwise, you will find [Defense Secretary] McNamara and me running like two foxes in front of two packs of hounds—the press and Congress—and we’ll surely be pulled down!”

At the same time as these decisive meetings of Lyndon Johnson’s group were taking place, the final launch preparations for the first piloted Mercury mission were playing out at Cape Canaveral. Important details about the mission remained shrouded from journalists covering the flight, particularly the identity of the first American to rocket into space. Weeks earlier NASA had announced that the pilot would be either John Glenn, Virgil “Gus” Grissom, or Alan Shepard. Since the introductory astronaut press conference two years earlier, John Glenn had been the media’s favorite. However, on the morning of the first launch attempt, the man in the silver pressure suit and helmet was revealed to be Alan Shepard. Glenn was his backup.

The sting of Gagarin’s flight, the humiliation of the Bay of Pigs invasion, and memories of the Vanguard disaster three and a half years earlier had the Kennedy White House worrying about risking further embarrassment. At home in Ceylon, Arthur Clarke had the same dark thoughts. “If they kill one of the U.S. astronauts, it will be just like the Vanguard situation again,” he remarked.

Specific details about Yuri Gagarin’s flight remained scarce. Even in Russia, news of the flight had been kept entirely secret until its success was assured. No film or television footage of the launch had been released, nor did anyone outside of Russia have a clear idea what the Vostok 1 spacecraft even looked like. Such information was guarded under a veil of military secrecy for years following the flight. Instead of pictures of hardware, photographs of Gagarin’s smiling face told the visual story of the Soviet space program to the rest of the world.

For the preceding two years, NASA’s public-affairs officer, Paul Haney, had pushed to open press access to launch information, including allowing for live television broadcasts of the liftoffs. Military policy prohibited the distribution of any information unless it had been approved, and current protocol embargoed the release of launch information until the event had occurred. This led to embarrassing situations such as journalists witnessing the explosion of an unpiloted missile followed by press officers releasing previously approved statements that flew in the face of what they all had just seen. Haney had been arguing that this policy made the public-affairs officers look like idiots and fostered cynicism and derision.

Under NASA’s previous administrator, Haney had gotten nowhere when trying to change the policy. But once Webb arrived, Haney had been told to take it up with the White House, which he did. The week of Shepard’s flight, Haney picked up a ringing phone in the makeshift office of his Florida motel room. The voice on the other end of the line was the president’s secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, calling from outside Kennedy’s Oval Office.

White House press secretary Pierre Salinger then got on the line. “Paul, the president’s wondering about the escape rocket on the Mercury capsule.” Kennedy wanted to know what were the odds, in the event of an aborted launch, that Shepard might die as the nation watched the live broadcast on television. Haney told Salinger the solid-fuel escape rockets had a success rate of close to 98 percent. There was a pause, and a few seconds later Salinger said, “The president says go ahead. Give it a go. See if it works.”

Haney threw the telephone up in the air in jubilation and dinged a ceiling tile. The launch would be televised live to the nation. He later credited that moment as the phone call that put the NASA public-information program in business. There was never a signed policy document. When he later tried to obtain one, Salinger told him, “Oh, shit, we don’t sign this stuff. You did the right thing.”

With that single phone call, the president of the United States had given the green light to the world’s first space-age reality-television series. NASA immediately began working with the national television networks to allow live broadcasts of launches from Cape Canaveral, accompanied by audio commentary from the public-affairs office. The networks were unprepared. The mobile units were operating out of cars and campers parked among the coastal flora in the new press area. Camera tripods had been secured on the roofs of the stationary vehicles, and massive cables snaked through the grass.

The morning of Salinger’s and Haney’s phone call, a tiny one-line item appeared at the bottom of page 30 of The New York Times: “MOSCOW, April 30 (UPI)—M. Bobrov, research director of the Astronomical Council of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, hinted today that Russian astronauts had begun training to rocket around the Moon.” Lyndon Johnson was compiling his recommendation for the president while someone in the Soviet Union was attempting to give a clear indication that they were already training for a lunar mission. In the panic of that moment in Washington, few wanted to concede that this might be another Soviet bluff, while those pushing for a stepped-up space program saw little reason to voice any skepticism.

Five days later, on May 5, the three American television networks interrupted their morning game shows to broadcast live America’s first human space adventure. When CBS, NBC, and ABC broke into programming at 10:22 A.M., Alan Shepard was already lying on his back in Freedom 7, situated atop the Redstone rocket where he had been waiting for nearly four hours.

At 10:34 Eastern Daylight Time, the Redstone was seen lifting off the launchpad on live television. On CBS, correspondent Walter Cronkite was providing audio commentary from a station wagon parked in the press area.

In Evelyn Lincoln’s White House secretarial office, a portable black-and-white television with extended rabbit-ear antennae had been turned on. As the time of the launch approached, Lincoln interrupted a National Security Council meeting and a group of approximately twelve filed into her office, congregating near the doorway. Closest to Lincoln’s desk were President Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson. To the side stood historian and special assistant to the president Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., assistant special counsel to the president Richard Goodwin, and assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs Paul Nitze, a ring of pipe smoke surrounding his head. Briefly dropping by was the president’s brother Robert, who was carrying a sheaf of papers and had a pencil tucked behind his ear.

On the television broadcast, the commentary was provided by “the voice of Mercury Control,” Air Force lieutenant colonel John “Shorty” Powers, whose nickname came from his five-foot-six-inch height. Usually seen wearing a radio headset and holding a clipboard, Powers delivered his public-affairs announcements with a sharp staccato inflection that implied that what he had to say was almost as vital to the mission as was the astronaut riding in the space capsule.

As the Redstone lifted off, the three national networks relied on the image from their pool television camera, which shakily attempted to follow the rocket into the sky. In the background could be heard the sound of muted applause. Viewers watching on CBS heard Walter Cronkite shout, “The Redstone got away all right!…Go, go!”

At the White House, Jacqueline Kennedy, dressed for a formal event in white gloves and a pillbox hat, was in a room near Evelyn Lincoln’s office. Through the open doorway her husband suddenly called to her, “Come in and watch this!” She joined the group and looked on, leaning against one of the secretarial desks.

About one minute into the flight, Powers announced, “Freedom 7 reports the mission is A-OK, full go,” and he made reference to members of the control team also signaling “A-OK.” In fact, neither Shepard nor the control team had used the phrase. It was Powers’s own invention, which he employed at least ten times during the fifteen-minute flight. Over the course of the next few years, the expression became ubiquitous in American households and in advertising copy, with many erroneously believing it to be insider astronaut lingo.

Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Special Assistant to the President Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Admiral Arleigh Burke, President John F. Kennedy, and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy watch live television coverage of Alan Shepard’s Mercury flight in the president’s secretary’s office in the White House.

The brief flight of Freedom 7 sent the Mercury capsule on an arced path that brought Shepard 116 miles above the Earth, before heading back to a splashdown 302 miles from Cape Canaveral. Shepard was weightless for approximately five minutes, but in that time he completed a brief test of the spacecraft’s systems.

The three television networks interrupted scheduled programming for fourteen different special telecasts that day, including extended thirty-minute recaps in the evening. British television viewers saw a few brief seconds of the liftoff, sent slowly, frame-by-frame, via telephone cable about an hour later. The BBC also had a mobile unit standing by at New York’s international airport, where the American television network pool feed of the launch was recorded on videotape and then immediately placed on a commercial jet headed to London.

On America’s third-place, also-ran network, ABC, the man on the beat was a new science reporter, thirty-two-year-old Jules Bergman, who during the next quarter century would cover every American crewed space mission for the broadcaster. Along with Cronkite, Bergman became the TV journalist most often associated with the American space program during the 1960s and early 1970s.

Cronkite’s patriotic enthusiasm for his nation’s first piloted spaceflight was evident. At the moment Shepard took manual control of Freedom 7, Cronkite emphasized that this was something Gagarin had not done. And in truth, Cronkite was noting an important distinction between the two programs: As early as 1959, NASA officials had determined that its astronauts would be active pilots of the spacecraft, as it was conceivable that their individual skills would be needed to successfully execute a mission. In contrast, the Soviet designers favored automated systems that prevented the first Russian cosmonauts from taking dynamic control of their spacecraft. Their primary role was as propaganda; there was little for them to do in space other than return home alive.

When reporting on Shepard’s flight, Soviet newscasts took pains to emphasize that the United States had only performed a brief suborbital mission, while Gagarin had completed a full orbit of the Earth. But the public response in the United States was anything but subdued. The flight of Freedom 7 sparked an outpouring of national pride not seen in years. Neither the television networks nor the White House was prepared for the overwhelming reaction. And the White House’s new resident was taking notice.

On a sunny morning three days after Shepard’s flight, a trio of Marine helicopters landed on the White House lawn. Emerging from the last helicopter were Alan Shepard, his wife, and Lieutenant Colonel Powers, who were greeted by the president and Mrs. Kennedy and Vice President Johnson. As James Webb, the other astronauts, and assorted congressmen looked on in the Rose Garden ceremony, the president awarded Shepard the civilian NASA Distinguished Service Medal.

A few minutes later Kennedy was due to address the annual convention of the National Association of Broadcasters. Newton Minow, who had been actively working to make the first telecommunications satellite a reality, had received a call from the White House, asking him to accompany the president to the event.

While waiting outside the Oval Office, Minow saw Kennedy gesture to him. “I’ve got Commander Shepard and Mrs. Shepard in my office. What do you think about taking him to the broadcasters’ convention?”

“That would be absolutely perfect,” Minow told him.

Kennedy then told the Shepards the plan and said to Minow, “You come with me. I want to change my shirt.”

In the White House living quarters, Kennedy proceeded to do just that, all the while engaging in conversation with Minow, who was feeling a bit awkward.

“So, what do you think I should say to the broadcasters?” the president asked.

Fumbling a bit and somewhat intimidated, Minow suggested he might want to talk about the difference between the way the United States conducted its missions in the open and the way they were done in the Soviet Union. “In the United States we invite radio and television broadcasters to be there and to provide the American people with an account of what is going on. In the Soviet Union, nobody really knows what happened—whether it was a success or a failure. Everything is hidden. You should thank the broadcasters for carrying the entire story of Shepard’s flight.”

On the way to the Sheraton Park Hotel, Minow noticed that the president was in an ebullient mood. He was basking in the moment, which had come after weeks of criticism for the Bay of Pigs and Gagarin’s flight. The president and the country suddenly felt good about something they had accomplished.

At the hotel there were rousing cheers and applause as Kennedy introduced the nation’s broadcasters to someone he described as the country’s “number-one television performer…[with] the largest rating of any performer on a morning show in recent history.”

The station owners and network executives loved it. And then, in an address that Minow believes was almost entirely improvised, Kennedy artfully enlisted the broadcasters as partners in America’s space program by using emotion to meld their innate patriotism with their responsibility as the electronic gatekeepers of a free and open society.

“There were many members of our community who felt we should not take that chance,” Kennedy told the audience. He was not only answering those who disagreed with his decision to broadcast the launch on live TV but also subtly countering critics of the piloted space program itself, such as former president Eisenhower, academic scientists, and his own science adviser, Jerome Wiesner. “But I see no way out of it,” Kennedy continued. “The essence of free communication must be that our failures as well as our successes will be broadcast around the world. And therefore we take double pride in our successes.”

Kennedy then asked his audience, whom he praised as the “guardians of the most powerful and effective means of communication ever designed,” to fulfill their national responsibility when promoting the country’s defense of freedom. As Shepard stood by his side, Kennedy made an emotional appeal to enlist the broadcasters’ partnership. Just what he had in mind would be revealed to the nation two weeks later.

Ironically, Kennedy’s well-received speech to the National Association of Broadcasters was quickly overshadowed by the address Minow delivered the next day, an open challenge to television executives to deliver on the medium’s enormous promise rather than merely providing “a vast wasteland” of entertainment. He urged the broadcasters to expand their offerings by calling upon a wider array of existing American talent, creativity, and imagination and to have the courage to experiment and include diverse voices and points of view. Minow’s speech was subsequently called “the Gettysburg Address of Broadcasting.”

Along with the famous images of the young president and his family, a number of the most idealistic and visionary speeches ever delivered—like Minow’s—define the Kennedy era and continue to stir the emotions of listeners more than half a century later. Kennedy gave only a handful of speeches about space exploration, but in them he captured the essential aspirational vision that served to explain America’s space program of the 1960s. And no speech was as pivotal as the one he delivered to an open session of the U.S. Congress on May 25, 1961, which was titled a “Special Message on Urgent National Needs” but was later known as “the moon-shot speech.”

Prior to this address, there had been no groundswell of public interest for a dramatic, expensive space venture. In a Gallup poll conducted shortly beforehand, nearly 60 percent of the respondents were opposed to spending billions from the national treasury to put an American on the Moon. Rather, Kennedy was exercising a leadership initiative. He delivered his speech when his approval rating was at an extraordinarily high 77 percent. Kennedy’s address was carried on live television at 12:30 P.M., in spite of grumbles from the networks about keeping it under an hour.

Framing the situation of the lagging American space program in terms of competing ideologies—democracy versus communism—President Kennedy requested an additional 7 to 9 billion dollars over the next five years to fulfill the dream that the space advocates had been urging since the early 1930s. “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.” Geopolitics established the agenda and the goal; science and exploration were secondary.

Despite the huge projected expense to the national economy, little vocal opposition followed it. Republican newsletters published the following week were far more critical of the president’s other domestic programs. Gagarin and Shepard had ushered in the age of human spaceflight, and in the emotion of the moment the inevitable destiny of the species in the stars went unquestioned.

Although newspapers had already published front-page intimations of the president’s moon-program proposal, some at NASA were caught off guard by Kennedy’s speech. Robert Gilruth, who had visited the White House after Shepard’s flight, first heard news of the speech when he arrived in Tulsa to attend a space conference. He was aghast at what NASA was facing. At their meeting a few days earlier, Gilruth had told Kennedy, “I’m not sure we can do it, but I’m not sure we can’t.” But Gilruth, only four years older than the president, sensed in Kennedy a youthful recklessness that might have been a factor in his decision. “He was a young man. He didn’t have all the wisdom he would have had if he’d been older. [Otherwise] he probably never would have done it.”

Cornered by a journalist at the Tulsa conference, Wernher von Braun provided a quotation crafted for American readers: The United States is “back in the solar ball park. We may not be leading the league, but at least we are out of the cellar.”

The singular importance of Kennedy’s May 25, 1961, speech may appear to place it as an isolated incident. However, it coincided with another major story unfolding at the time. The day before Shepard’s flight, the first Greyhound bus carrying thirteen Freedom Riders into the American South left Washington, D.C., destined for Louisiana. Most of them were college-age students motivated by Kennedy’s call to service, volunteering to challenge the existing racial-segregation laws.

The Greyhound bus never arrived in Louisiana. Eleven days into its journey, a mob of people—many of them members of the Ku Klux Klan—attacked and burned the bus in Anniston, Alabama, one hundred miles south of Huntsville. The attackers assaulted many of the students, even attempting to burn them alive inside the bus. On May 20, a crowd armed with baseball bats, broken bottles, and lead pipes attacked another Freedom Rider bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Besides proving to be a decisive moment in the emerging American civil rights movement, the attacks on the Freedom Riders attracted network journalists equipped with the new lightweight 16mm news cameras that had become available only in the past year. The great news stories of the 1960s would be covered differently than before. Portable 16mm film cameras were taken into space, to the jungles of Southeast Asia, and to the streets of Selma, Alabama, to tell the news with an immediacy and emotional impact that previous generations had never seen.

Had it not been for television, many contend, the civil rights revolution would not have occurred when it did. “When television viewers saw dogs being unleashed against kids who were marching for freedom and saw the violence on their screens, the conscience of America was awakened,” explained Newton Minow. “And that had a lot to do with changing public opinion.” The images from the South were also affecting America’s reputation as a beacon of freedom for the rest of the world. This proved particularly problematic in the newly independent, non-aligned countries of Africa, Latin America, and Asia, which after decades of colonialism were becoming of strategic and economic interest to the two opposing Cold War superpowers.

An addition to the Kennedy administration roster was a government outsider recognized by most American television viewers: journalist Edward R. Murrow, who for more than two decades served as the voice and conscience of CBS News. By 1960, Murrow had grown increasingly disaffected with his relationship with the network and its chairman, William Paley. The CBS chairman’s chilly reaction to a Murrow speech criticizing television’s failure to deliver on its potential, and Murrow’s rivalry with the younger Walter Cronkite, prompted the veteran newsman to accept Kennedy’s invitation to oversee the United States Information Agency (USIA), charged with shaping America’s public image abroad.

During mid-1961, as the images from Cape Canaveral and Alabama filled newspapers and newsreels, Murrow wondered if negative stories of racial prejudice might be countered by a more inspiring space-related story that would appeal to foreign readers. Murrow typed out a quick memo to his fellow Carolinian James Webb, which asked: “Why don’t we put the first non-white man in space? If your boys were to enroll and train a qualified Negro and then fly him in whatever vehicle is available, we could retell our whole space effort to the whole non-white world, which is most of it.”

And then he sent a second copy to Robert Kennedy. At the bottom Murrow added, “Hope you think well of the attached idea. It is practically an orphan.”

Webb had also been thinking about how powerfully space-age imagery might affect public opinion and support. While he agreed that positive benefits might result from Murrow’s proposal, he thought it difficult to implement. It could also enrage some of the staunch segregationist congressmen representing the Southern states that had NASA centers. Nevertheless, Webb added that he would keep it in mind, likely hoping this would be the last he would hear of the matter. It was not.

ALMOST IMMEDIATELY AFTER Kennedy made his landmark address to Congress, he began having second thoughts. The expense was enormous. And after flying a single astronaut on a fifteen-minute flight, no one at NASA had a clear idea how they would get a crew all the way to the Moon and back.

In early June, less than a month after his announcement, Kennedy flew to Vienna for his first—and what proved to be only—meeting with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. There was no formal agenda, but the discussions did not go well. By their conclusion Khrushchev left the meeting convinced that his Western adversary was as naïve and reckless as his recent actions had suggested. But largely overshadowed by subsequent events was a brief discussion about space that had taken place between the two leaders. Kennedy had made a bold and unexpected overture to Khrushchev, proposing that in a public gesture of cooperation the two superpowers combine their resources and venture to the Moon jointly.

At first it appeared that Khrushchev was open to the idea, but the next day he rejected it. When he returned from the summit, Khrushchev explained to his son Sergei that if the two superpowers worked together, keeping Soviet secrets would be impossible. The United States would discover that the Russian ICBMs were far less efficient than they had claimed. Kennedy’s proposal went nowhere, but he refused to abandon the idea.

The president’s request for more than a half billion dollars for accelerated space exploration was approved by Congress and signed into law the day of the second Mercury Redstone mission, piloted by Gus Grissom, on July 21, 1961. Within days of its passage, advertisements began to appear in trade publications. The defense and aerospace contractor General Dynamics enticed engineers and scientists “just a cut above the average” to consider relocating to San Diego. The ad featured an illustrated montage showing a smiling middle-class couple engaged in water-skiing, tennis, swimming, and golf, promising the immeasurable rewards of working on the country’s space program while raising a family in Southern California’s resort-like climate.

After President Kennedy’s space budget was approved by Congress in mid-1961, American aerospace contractors ran trade advertisements to lure additional engineers and scientists. Honeywell touts the coming Apollo program with an early visual conception of the three-man moon ship.

Far more difficult tasks faced the leaders at NASA. Specifically, they needed to determine the best method for successfully accomplishing Kennedy’s challenge on time and on budget. NASA had previously undertaken a long-term study of a moon landing as a thought experiment, but the details of how to accomplish Project Apollo—as it had been named in mid-1960—were still very much up for debate.

A decade earlier, in his Collier’s article, Wernher von Braun had proposed a landing on the Moon using multiple large vehicles assembled near a revolving space station in low earth orbit. A few years later he proposed launching men from the Earth to the Moon in a single gigantic rocket. After jettisoning the large stages that boosted it into space, a single piloted vehicle would then proceed to the lunar surface and subsequently return to Earth, much like the British Interplanetary Society’s moon-ship scenario of 1939. In contrast to the “earth-orbital rendezvous” approach utilizing the space station, this straight-line approach became known as “direct ascent.” In fact, neither method was practical given the current state of technology in the early 1960s. Additionally, both plans required that hundreds of pounds of fuel and provisions needed only for the final return journey travel to and from the lunar surface with the astronauts.

With Kennedy’s 1970 deadline hanging over everyone’s head, building von Braun’s massive spinning space station for the earth-orbital-rendezvous scenario was too complicated to be a viable option. And while few doubted that von Braun’s Saturn rocket could eventually get men to the Moon, the trick of landing on its surface and then launching from lunar gravity to return to Earth added another order of magnitude of complexity. NASA’s brain trust next gravitated toward accepting an earth-orbital-rendezvous plan in which a moon vehicle would be assembled in earth orbit from components launched on multiple rockets.

Gradually a third option, which had been dismissed in earlier discussions, was given another look. It was a risky scenario but offered strategic advantages. Known as “lunar-orbit rendezvous,” it was championed by John Houbolt, a young aerospace engineer from NASA’s Langley Research Center. It proposed launching together on a single rocket two individual small spacecraft—the Apollo and a lunar-landing bug. They would then separate during lunar orbit. The bug would descend to the Moon, land, and then return to lunar orbit. The two craft would rejoin in lunar orbit, the empty bug would be jettisoned, and the entire crew would return to Earth in the Apollo spacecraft. It was an unorthodox proposal as it required multiple rendezvous and dockings far from the Earth, something no one was certain could be routinely accomplished in the weightlessness of space. It also entailed designing separate guidance, environmental, and propulsion systems for both spacecraft, a redundancy many believed would add unnecessary complications.

Von Braun had been a vocal opponent of the lunar-orbit-rendezvous idea when it was first proposed, as it would reduce the role of his group at the Marshall Center. However, he surprised his colleagues at a meeting in mid-1962 when he unexpectedly endorsed the plan. He believed it would balance managerial coordination between Robert Gilruth’s group, his group in Huntsville, and those at the Cape, along with the primary contractors, which would eventually include Boeing, North American Aviation, Grumman, and Douglas Aircraft. It was a politically savvy compromise as well, since it deflected some of the rivalry that had been building between the NASA centers.

Simultaneously, another group of engineers from Gilruth’s group began considering ways to expand upon Project Mercury, with a second crewed program that would serve as a developmental bridge to Apollo. They coordinated with technicians at McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, the contractor for the Mercury spacecraft, to conceive a larger spacecraft similar to Mercury, dubbed the Mercury Mark II. This soon evolved into a far more complex two-man vehicle renamed Gemini, which would take astronauts on earth-orbital flights for as long as two weeks. These longer missions would pioneer the development of independent electricity-generating fuel cells rather than relying exclusively on batteries and, it was hoped, perfect a method of returning to dry land with the use of a delta-shaped paraglider, forgoing the need of expensive U.S. Navy ocean recoveries.

Few of NASA’s debates and long-term decisions about how America would get to the Moon garnered a fraction of the media attention given the immediate human drama of Project Mercury. The genuine popular curiosity and enthusiasm about Alan Shepard’s achievement foreshadowed the next chapter in the escalating international competition between the two superpowers: America’s attempt to place a human in orbit. Realizing this moment would likely generate even greater interest, the network news divisions and their counterparts in the print media spent the months prior to the first U.S. orbital mission conceiving how to best tell the story.

Experienced journalists covering America’s piloted space program realized there was an additional aspect to this flight that was markedly different from the earlier Mercury flights: the astronaut. John Glenn had neither the laconic wariness of Gus Grissom nor the steely arrogance of Alan Shepard. Glenn’s wholesome yet mature smiling freckled face was perfect for the television age. He was an articulate, clean-cut example of American masculinity and seemed the ideal personification of the nation’s dominant culture. A genuine war hero, who had flown sixty-three combat missions in Korea, Colonel Glenn was already a minor celebrity for pioneering the first supersonic transcontinental flight in 1957.

In fact, Glenn had been scheduled to fly a third suborbital mission. But when the Soviet Union orbited cosmonaut Gherman Titov seventeen times a few days after America’s second Mercury suborbital flight, Glenn’s mission plan was changed to an earth orbital trajectory. He would also be the first human to ride an Atlas, the Air Force’s ICBM missile with a well-known history of launch problems and explosions.

During the early days of the Mercury program, when an actual emergency occurred it wasn’t fully evident to viewers watching at home. Gus Grissom nearly drowned during the second Mercury flight while Marine helicopters were attempting to recover his sinking capsule from the Atlantic Ocean, but television viewers were largely unaware of the drama as there was no live television from the recovery site. A pool journalist on the recovery ship USS Randolph transmitted a live audio report merely relaying the news that Grissom was in the water but “the concern at the present time is with the capsule.” Unknown to the reporter, Grissom had been forced to abandon Liberty Bell 7 as it began to sink, and once in the ocean his flight suit had begun to fill with water. After four minutes struggling to keep his head above the waves, Grissom was hoisted aboard the helicopter, but his capsule was lost.

Once a rocket disappeared from visual sight after launch, the television networks were forced to resort to their own creative alternatives to visually tell the story of the early space missions. The Mercury orbital flights involved hours of live television coverage, but with no television camera in the spacecraft, producers relied on images of oscilloscopes, console displays, radio antennae, and prerecorded videos of tense flight directors working in the control center. The audio of Shorty Powers’s reports from Mercury Control was matched with crude animated images showing the rocket speeding into space and a clock that indicated the elapsed time since launch. It then fell to the network correspondents to convey any sense of actual excitement, since there was nothing to see.

The launch of Glenn’s Friendship 7 was postponed ten separate times before it was finally on its way, and as a result the networks expended hours of valuable airtime in the days leading up to the February 20, 1962, launch. This not only increased suspense but panicked the network accountants. Days before the launch, Glenn’s flight was already being referred to as television’s “most extensively and expensively reported single news story.” Even live gavel-to-gavel broadcasts of the national political conventions required less expense and labor. By early 1962, Walter Cronkite was no longer required to sit in a car while providing his audio commentary. CBS assembled a semi-permanent structure, referred to as its “Cape Canaveral Control Center,” from which Cronkite could report, seated at a desk with the launchpad visible behind him.

In the White House, John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson watched the launch of Friendship 7 on television, surrounded by a few members of Congress. While the room was quiet with the tension of the moment, Johnson turned to Kennedy and said regretfully, “If Glenn were only a Negro.”

The country spent the entire day transfixed by the news of Glenn’s odyssey as he circled the globe, and by late afternoon millions were following reports of his return. The final minutes of his flight were not without additional suspense: A faulty signal erroneously indicated that the spacecraft’s heat shield had detached prematurely. The voice of the otherwise very cool Glenn sounded concerned when he was asked not to jettison the retro-rocket package, an unexpected request added as a safeguard to keep his spacecraft’s heat shield secured. Luckily, Friendship 7’s fiery reentry was over in minutes and word was soon broadcast that Glenn and his capsule were in the process of being recovered in the Atlantic.

Summing up the nation’s psyche on NBC News that evening was Frank McGee, a journalist typically far less prone to showing personal emotion on air than Cronkite. “We have by this time, it seems to me, reached the point of something bordering on hypnosis—irresistibly drawn to the event, and at the same time repelled by our fears of what might happen.”

The nation’s emotional reaction to Glenn’s flight only confirmed what President Kennedy had sensed immediately after Shepard’s mission a few months earlier: that television would transform America’s attitude toward spaceflight as it had toward politics. And the television networks realized it too, despite the lack of live images from space. When delivering his evening special report recapping that day’s landmark flight, NBC’s McGee regretfully informed viewers that the network was not yet able to obtain motion-picture film showing the astronaut’s recovery from the Atlantic Ocean. At that moment the 16mm film magazine containing that footage was traveling by air to a facility in Florida, where it would be hastily developed and then transmitted to the nation through NBC’s New York network feed. Instead, the only image McGee could offer viewers was a grainy black-and-white photo of Glenn on board the recovery ship, which had been transmitted via wirephoto equipment, a technology in use since the 1930s. However, within months, and with little advance warning, television news broadcasting would take a startling leap forward.

FOLLOWING HIS CONTROVERSIAL address to the broadcasters, Newton Minow had become one of the Kennedy administration’s most public figures. But more quietly, Minow had been working to circumvent the legal issues surrounding placing the first commercial communications satellite in space and had prevailed upon the president to institute a program for the satellite that would benefit everyone on Earth. NASA would play the role of transportation provider for what would be the first privately sponsored space mission.

Concurrent with Minow’s actions, Arthur C. Clarke delivered a paper in Washington on “The Social Consequences of the Communications Satellites.” He then traveled to the American Rocket Society’s annual conference in New York. During a public panel discussion that included von Braun, Clarke pointed out that if a synchronous television satellite were operational by 1964, it might be possible for everyone around the world to watch the Tokyo Summer Olympic Games. William Pickering, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s director, was sitting in the audience and was so taken with the idea that he mentioned it to Lyndon Johnson. The next day, when Johnson delivered his keynote address, Clarke’s proposal about broadcasting the 1964 Olympics had been inserted into the prepared text.

Audiences didn’t have to wait until the 1964 Olympics to see the first live intercontinental satellite television broadcast. It happened only nine months later, while those living in the eastern United States were enjoying a hazy summer afternoon. Viewers who tuned in for the regularly scheduled broadcasts of the soap opera The Edge of Night or the game show To Tell the Truth discovered that both had been preempted by a special news report. NBC’s Chet Huntley, CBS’s Walter Cronkite, and ABC’s Howard K. Smith alternated hosting duties from studios in New York for a transmission seen not only all over America but in sixteen European countries as well. Two weeks earlier a Thor-Delta rocket had lifted off from Cape Canaveral to place Bell Labs’s Telstar 1 in a non-synchronous orbit three thousand miles above the Earth. Cronkite told viewers at the opening of the broadcast, “The plain facts of electronic life are that Washington and the Kremlin are now no farther apart than the speed of light—at least technically,” a statement that failed to mention the broadcast was not being seen in Russia. Huntley then introduced a transition to one of President Kennedy’s news conferences, already in progress at the State Department’s auditorium. With apologies, Huntley cut away two minutes later to introduce John Glenn. Sitting in the Mercury control room at Cape Canaveral, Glenn spoke to the camera about projects Gemini and Apollo before introducing astronaut Wally Schirra, dressed in his silver flight suit.

Unable to view the historic Telstar broadcast was one person who had worked for years to make it happen. During the summer of 1962, Arthur C. Clarke was in Ceylon, though in a nursing home, slowly recovering from a mysterious near-fatal paralysis. His doctors assumed he had suffered a spinal injury as a result of an accidental blow to his head, but decades later, when he was in his seventies, was it determined that Clarke had actually contracted poliomyelitis.

The summer of Telstar, Kennedy was facing a series of difficult decisions regarding NASA’s projected 1964 budget. There was a faction within NASA pushing him to increase spending, to eliminate any possibility that the Russians might get to the Moon first, though James Webb was not among them. The president’s advisers suggested he conduct a fact-finding tour of NASA facilities and prime contractors to see how all the money was being spent. In St. Louis, the president addressed five thousand workers in a huge assembly room at McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, the prime contractor for both the Mercury and soon-to-be-delivered two-man Gemini spacecraft. He praised their part in “the most important and significant adventure that any man has been able to participate in [in] the history of the world.”

A few minutes later, Kennedy looked across the crowd and saw the face of Newton Minow, who had traveled on the vice president’s plane.

Kennedy crooked his finger and motioned for his celebrity FCC commissioner to come over, then addressed him privately.

“I understand why Jim Webb and the NASA people are here, but what are you doing here?” he asked.

“Well, Mr. President, space exploration isn’t only the manned program. I think communications satellites are more important than sending a man into space.”

“And just why do you say that?” Kennedy asked.

“Because,” Minow continued, “communications satellites will send ideas into space, and ideas last longer than people.”

Kennedy didn’t respond, but his reflective gaze conveyed to Minow that he had made his point.

NASA Administrator James Webb looks on as President John F. Kennedy speaks to journalists during a September 1962 visit to the space agency’s new facility in Houston, Texas. Towering behind them is a preliminary design of the lunar module, the vehicle the United States intends to land on the moon before the end of the decade.

Earlier that day, before arriving in St. Louis, the president had addressed a crowd of forty thousand Texans seated in Rice University’s football stadium in Houston. Speaking in the blazing sun in ninety-degree heat, he gave a speech that morning that, along with his address to Congress a year earlier, would become one of the most often-quoted pieces of space-advocacy rhetoric in history. It was here that he asked his fellow Americans, and the rest of the world:

But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, “Why climb the highest mountain? Why, thirty-five years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?”

We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things not because they are easy but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others too.

Rice University had been chosen as the site of the address because, the previous autumn, Houston had been selected as the home of the new NASA Manned Spacecraft Center, to succeed the facility overseen by Robert Gilruth at the Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. A long list of potential sites in the southern half of the United States had been discussed. However, it was the lobbying effort of Congressman Albert Thomas that managed to make his home district of Houston the winning location for the world’s most renowned space-mission control center. Congressman Thomas not only represented Houston and was a Rice University alumnus, but he chaired the powerful House Appropriations Committee, which oversaw NASA’s budget. Using his network of connections in Texas business and real estate and at Rice—plus a bit of Washington wheeling and dealing—Thomas arranged that one thousand acres of cattle-grazing land previously donated to Rice by the Humble Oil Company for a federal academic research facility be designated as the location for NASA’s new center.

On the day of Kennedy’s speech, Rice University was still segregated, in accordance with the wishes of its original founder, who in 1891 established the Rice Institute for the free instruction of white Texans. But if, as planned, Rice University was to partner with NASA’s new facility and obtain federal-government funding to create a nearby department of space science, problems lay ahead.

Under the intense Texas sun, Kennedy enticed his listeners with the promise of the future. “Houston, your city of Houston, with its Manned Spacecraft Center, will become the heart of a large scientific and engineering community.” What he well knew but didn’t mention that day was that his brother, as attorney general, could call upon the Department of Justice to deny any federal money from going to a segregated public institution.

Two weeks after Kennedy spoke at Rice, the university’s board of trustees voted unanimously to give the thousand acres to NASA and in a second unanimous vote approved a motion to file a lawsuit to change Rice’s charter to admit black students. The trustees’ vote was not without controversy; Rice alumni protested, and it wasn’t until February 1964 that a jury trial resolved the situation in favor of the trustees.

Kennedy’s aspirational rhetoric was not only calling for personal sacrifice to further democracy and freedom and explore the heavens; he was also asking the country to enact social change in order to resolve the effects of the sins of the past. It had only been a year since the pictures of the Freedom Riders’ burning bus were seen on television.

As the three-year reign of the seven Mercury space celebrities was nearing an end, NASA held a press conference at the University of Houston to introduce the world to the nine new astronauts slated to fly on the upcoming Gemini and Apollo missions. One of these men might even become the first human to set foot upon the Moon. They were not only younger than their Mercury predecessors, Astronaut Group Two—or “the New Nine,” as they came to be known—included the first two civilian astronauts. NASA wanted to make the public aware of this distinction and did so in a savvy and memorable moment of media history. CBS coordinated with NASA to transport a modest middle-aged couple from Ohio to New York, where they appeared as contestants on the prime-time game show I’ve Got a Secret. As the cameras focused on the faces of Viola and Stephen Armstrong, their secret was superimposed onscreen, revealing to television viewers: “Our son became an ASTRONAUT today.”

After the secret was guessed correctly following an interrogation by the panel of celebrities, host Garry Moore emphasized that the couple’s son, Neil Armstrong, was a civilian pilot, albeit one who had already flown to the edge of space in NASA’s experimental X-15 rocket plane. Moore then asked a logical yet prescient question: “Now, how would you feel, Mrs. Armstrong, if it turned out—of course, nobody knows—but if it turns out that your son is the first man to land on the Moon? How would you feel?”

Armstrong was unable to see the program or hear his mother’s understated response wishing him “the best of all good luck,” his selection having been announced only hours earlier at the press conference. NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center director Robert Gilruth revealed that women had been among the 253 applicants, but “none were qualified.” At the long front table with Armstrong were Frank Borman and Ed White, who had attended West Point; James Lovell and Thomas Stafford, who had gone to the Naval Academy; two additional former naval aviators, John Young and Elliot See; James McDivitt, an Air Force pilot who had graduated from the University of Michigan; and Charles “Pete” Conrad, the only astronaut of his generation with an Ivy League education. Conrad, a prep-school dropout with dyslexia (then little known and undiagnosed), went on to graduate from Princeton University with a full Navy ROTC scholarship. Eight of the New Nine would make history in outer space before they were in their early forties.

AFTER A SILENCE of a few months, Edward R. Murrow decided to revive his suggestion that NASA integrate the astronaut corps. He had been repeatedly told that all astronaut candidates must be experienced test pilots, prompting Murrow to write President Kennedy a memo asking whether the United States shouldn’t begin training black test pilots now. He added, “The first colored man to enter outer space will, in the eyes of the world, be the first to have done so. I see no reason why our efforts in outer space should reflect with such fidelity the discrimination that exists on this minor planet.”

At about the same time that Murrow wrote the president, an advisory committee investigating equal opportunity in the military focused its gaze on the nation’s most celebrated pilot training school, at California’s Edwards Air Force Base. Colonel Chuck Yeager, the man who in 1947 first flew a plane faster than the sound barrier and served as the idol of every jet-fighter pilot in the United States, had just been named commandant of the Air Force’s Aerospace Research Pilot School, a new addition at Edwards. When a White House aide inquired whether there were any African American pilots enrolled in the ARPS, the answer was a curt “no.”

At the request of the White House, the Pentagon began a search to find a qualified minority candidate for ARPS, ideally a black Air Force pilot with extensive flight experience and a technical degree. The name that quickly rose to the top of the relatively short list was a twenty-eight-year-old Air Force captain named Edward Dwight, who had a combined total of 2,200 hours of jet-flying time, an outstanding service record, and a degree in aeronautical engineering.

Opening his office mail on a routine afternoon, Dwight encountered a letter that was unlike anything he had seen. It proposed he enroll in the test-pilot school at Edwards as part of a program to be the first African American astronaut. Well aware of the Kennedy administration’s commitment to enforcing desegregation and equal opportunity, Dwight realized this could be his chance to play an important part in moving the country forward. But he was mindful that a tremendous risk accompanied the proposal: If he was successful, he would make history and a promotion was assured; if he failed, there was likely no coming back.

Ed Dwight had been fascinated with aircraft since watching P-39 Airacobra fighters fly out of an Army Air Force field in Kansas City during World War II. As early as junior high school, he was borrowing books from the local library to learn the math and physics required to pass pilot training exams, study that proved invaluable when he took an Air Force pilot’s exam. After graduating from college he joined the Air Force, where he learned to fly jets, became a flight instructor, and earned his degree in aeronautical engineering at Arizona State University.

He was a married father of two children, stationed at Travis Air Force Base in California, when he followed up on the letter and submitted his Edwards application. Typically after submitting such paperwork months of silence would elapse, but Dwight received an immediate response, ordering him to Edwards a few days later. He had expected to be among other African American candidates but discovered he was the only one. Initially, he and the other members of the new class bonded, unified by their fledging test-pilot status. However, it wasn’t long before alpha-male behavior prevailed, with every candidate engaged in a competition of survival of the fittest. Dwight got along well with the other pilots but was also viewed with suspicion. There were rumors that due to his friends in the White House, Dwight had an unfair advantage, and that his success would only come at the expense of his fellow classmates.

Chuck Yeager, Edwards’s feisty and notoriously stubborn commandant, did nothing to make Dwight’s situation any easier. Yeager had been pressured by Air Force chief of staff General Curtis LeMay to admit Dwight, a request that LeMay told Yeager came directly from Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Believing his school was being used to further the administration’s political agenda, Yeager did nothing to hide his resentment. By the early 1960s, Yeager’s own fame was being eclipsed by the attention accorded the Mercury astronauts, an elite club Yeager couldn’t have joined even if he had wanted to. He lacked both a college education and an engineering degree.

Prior to coming to Edwards, Dwight had idolized Yeager. Once there, however, he encountered a man who exerted strict control over his school and who didn’t appreciate outside interference—especially when it originated in the White House. A confidant at the school told Dwight that Yeager had assembled his entire staff of instructors to inform them that the White House had forced him to enroll Ed Dwight in ARPS in an attempt to promote racial equality. Dwight was told Yeager then suggested that if they all failed to speak, drink, or fraternize with him, Dwight would be gone in six months.

Dwight was mindful of the legacy of Major General Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., who endured four years of near-complete social isolation as a member of the West Point class of 1936. Davis, the first African American to graduate from the U.S. Military Academy in the twentieth century, was also legendary as the first commander of the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II. Like Davis, Dwight refused to drop out.

Yeager felt as if his elite school was under siege, especially when lawyers from Robert Kennedy’s Department of Justice arrived to investigate claims of racism and discrimination in the Air Force’s treatment of Dwight, making an uncomfortable situation even worse. In his autobiography written more than two decades later, Yeager likened the experience to being “caught in a buzz saw of controversy…[as] the White House, Congress, and civil rights groups came at me with meat cleavers.” He explained that if any discrimination was involved, it was based on his conviction that Dwight was not qualified to be in the school.

After Captain Edward Dwight was named a candidate at Edwards Air Force Base’s elite aerospace pilot school in 1963, many in the press thought it inevitable he would be named America’s first black astronaut later that year. However, despite some progress in civil rights made during the 1960s, NASA did not select the first African American astronaut until 1978.

Despite the adversarial situation at Edwards, Dwight’s hard work and determination to persevere paid off, and he graduated sixteenth in his class. But Yeager would only advance his top ten students to the ARPS postgraduate school for astronaut training. When it became apparent that Dwight’s name would not be on the list of astronaut trainees, General Curtis LeMay interceded at the behest of the White House. He made a deal with Yeager to enroll Dwight in the ARPS astronaut school by expanding the number of students from ten to sixteen, a move intended to appease the White House without giving the appearance that Dwight had received any preferential treatment.

Viewers watching a March 1963 NBC Sunday evening newscast heard reporter Robert Goralski announce to the nation that “A twenty-nine-year-old Negro says he is anxious to go into space. He is Edward Dwight of the Air Force, selected to be an astronaut, the first of his race to be so designated. Captain Dwight and his family got the news at his home at Edwards Air Force Base in California.”

The press assumed that anyone who finished the ARPS was likely to go into space either as a NASA or Air Force astronaut; however, the manner in which astronauts were chosen remained opaque, rules were often bent and requirements adjusted. Being chosen to attend ARPS did not guarantee future selection on a space mission, but at the time this detail was lost on most journalists not covering the space program.

The national struggle for civil rights was entering a new phase. Alabama’s new governor, George Wallace, had been sworn into office with a defiant address proclaiming, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Reverend Ralph Abernathy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were jailed on Good Friday during a campaign in Birmingham to apply pressure on local merchants who practiced segregation. Subsequently, the city’s police commissioner approved the arrest of nearly one thousand children during a demonstration and moved against protesters with dogs and fire hoses, producing disturbing images that were printed on newspaper front pages and seen on the national news broadcasts.

In response, entertainers in Hollywood threw their support behind a “Freedom Rally,” where Paul Newman and Sammy Davis, Jr., joined Dr. King and a crowd of more than forty thousand at the largest civil rights gathering ever held on the West Coast. Comedian Dick Gregory, who appeared on the stage next to Dr. King, referenced the news about Ed Dwight’s selection in his comedy monologue: “I read in the paper not too long ago, they picked the first Negro astronaut. That shows you so much pressure is being put on Washington. These cats just reach back and they trying to pacify us real quickly. A lot of people was happy that they had the first Negro astronaut. Well, I’ll be honest with you, not myself. I was kind of hoping we’d get a Negro airline pilot first. They didn’t give us a Negro airline pilot. They gave us a Negro astronaut. You realize that we can jump from back of the bus to the Moon?” Gregory also did a riff about landing on Mars and meeting an alien with “twenty-seven heads, fifty-nine jaws, nineteen lips, and forty-seven legs,” whose first words to him were “I don’t want you marrying my daughter neither.”

King laughed along with the crowd at Wrigley Field, but unlike the African American press, which was publishing features about Dwight and his family, King, like Gregory, was no fan of the push for a black astronaut. He saw it as the equivalent of promoting the achievement of an exceptional black athlete on a box of Wheaties. Both did little to further African Americans struggling for advancement. In fact, he thought it could be detrimental, leading those in power to assuage their larger responsibility. “Well, you got an astronaut. What more do you want?”

Shortly before Dwight was to begin the ARPS graduate course, another jet pilot, then an engineer and instructor at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, New Mexico, was driving his Volkswagen bus through the New Mexico desert while listening to the car radio. Bill Anders, a twenty-nine-year-old Air Force captain with more than 1,500 hours flying time, had been twice thwarted when trying to gain admission to the Edwards Aerospace Research Pilot School, yet he remained determined to get in.