CHAPTER 11

COMPUTER APPLICATIONS IN ETHNOBOTANY

ASHISH KUMAR PAL1 and BIR BAHADUR2

1Formulation Analytical Research Department, Aurobindo Pharma Limited and Research Centre, Survey No. 313, Bachupally Village, Quthubullapur Mandal, R.R. District 500090, Telangana, India, E-mail: ashishkumarhyd@gmail.com

2Department of Botany, Kakatiya University, Warangal 506008, Telangana, India, E-mail: birbahadur5april@gmail.com

CONTENTS

11.2Utilities of Computers in Ethnobotany

11.3Relevance of Computers in Current Ethnobotany Practices

11.5Types of Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis (CAQDA) Based on Their Function

11.6Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) General Approaches

11.7Systemization of Ethnobotanical Methods

11.8Steps and Basic Capabilities of CAQDA

11.9Types of Softwares Used in Ethnobotany

11.10Recent Developments in Computer Applications in Ethnobotany

11.11Quantitative Research in Ethnobotany

11.12Types of Quantitative Analysis Softwares

11.13Future Relevance of CAQDA in Ethnobotany

ABSTRACT

To date, many researchers have had to rely on was their memory of the data they collected and the meaning of those data in the context of their ethnobotanic study. However, the working of memory create two potential problems for researchers analyzing the field data. First, researchers may use those data that were most dramatic in the fieldwork and erroneously present them as being the most significant; second, they may use more data from the later stages of fieldwork and less of what happened in the middle or beginning because the later data are fresher and clearer in their minds. Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDA) can help the careful analyst avoid both these problems. Also, the volume of data and its compilation also presents a big challenge to modern ethnobotanist. Quantitative Computer Soft wares can help reduce these issues. The use of computers could stimulate team approaches in research that would generate a wealth of data and make important analytic contributions. Also in teams, the data are gathered by a number of researchers who in many cases have different degrees of training as well as different degrees of insight, there is no way to assure consistency in what each researcher thinks it important to record. Thus computer are of great help in ethnobotanical research. The present paper is an effort to bring forth several qualitative and quantitative softwares now available in market that offers the researcher the choice the optimum software depending upon both its advantages and limitation so that a suitable conclusion can be drawn for ethnobotanical research work.

11.1INTRODUCTION

Computer-assisted data analysis (CADAS) is associated with the analysis of aggregate data according to the tenets of logical positivism. There are more than twenty computer programs designed to assist researchers analyzing ethnographic data, and these programs may be used by researchers with a variety of epistemological orientations.

Computer-assisted analysis in sociology is currently associated with both categories of researches namely quantitative and qualitative research. Statistical procedures available in main stream software packages, such as statistical analysis system (SAS) and statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) helps the analysis of aggregate data, and thus computer-assisted analysis carries suggestions of hard data, computation, and objectivity.

Qualitative research aggregate data analysis using statistical procedures has many setbacks, as it either misses important sociological causes of social action or emphasizes at the expense of understanding. Software for the analysis of qualitative data has appeared relatively recently, because qualitative sociologists have been slow to adopt to softwares.

11.2UTILITIES OF COMPUTERS IN ETHNOBOTANY

Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDA) programs automate analysis procedures that have been used by ethnobotanists. This opens up new avenues through the use of linked coding schemes, hypertext, and case-based hypothesis testing. Just as it can with aggregate data, computer assistance can facilitate systematic computational research with qualitative data. In addition, CAQDA technologies can be useful to researchers who place themselves outside the positivistic research tradition.

CAQDA does not differ fundamentally, for the most part, from the no mechanical qualitative analysis traditions from which it has developed. Most computers ease the labor burden and broaden the scope of common analysis tasks, such as typing up field data and memos, searching for text, coding data, sorting and comparing codes. Hypermedia is an unique contribution of computer technology to the analysis of qualitative data. Linking text, analysis, and non-text materials (graphics, sound, and video) in a single analytical space outside the mind’s eye is not possible manually.

Such software helps to organize, manage and analyze information. The advantages of using this software include being freed from manual and clerical tasks, saving time, managing huge amounts of qualitative data, having increased flexibility, and having improved validity and auditability of qualitative research. Concerns include increasingly deterministic and rigid processes, privileging of coding, and retrieval methods, rectification of data, increased pressure on researchers to focus on volume and breadth rather than on depth and meaning, time and energy spent learning to use computer packages, increased commercialism, and distraction from the real work of analysis.

11.3RELEVANCE OF COMPUTERS IN CURRENT ETHNOBOTANY PRACTICES

The use of computer assisted data analysis is comparatively a newer concept in ethnobotany. Field notes have been transcribed into word processors and many ethnobotanist now carry portable lap-top computers to the field. The use of computers for the analysis (rather than the gathering) of ethnobotanical data is a comparatively recent development.

11.4TYPES OF SOFTWARES

Computers can be programmed to accomplish four different kinds of analysis: numerical/arithmetic analysis, writing and document processing, data organization, and symbolic manipulation. Ethnobotanists use computers for all these kinds of analysis.

11.5TYPES OF COMPUTER-ASSISTED QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS (CAQDA) BASED ON THEIR FUNCTION

CAQDA softwares are classified into the following types based on their function and their ability to analyze the data gathered (Weitzman and Miles, 1995).

11.5.1DOCUMENT PROCESSING: SEARCHING AND RETRIEVING

Word processing is the major feature of computer assistance for the ethnographer. Many ethnobotanist require computer assistance for searching with a word processor. Basic searches retrieve a text string from a single computer file. More advanced searches count the occurrences of “a string” and standalone search engines can search multiple files and produce extracts of search “hits” in context. Specialized programs developed for both CAQDA and commercial uses enhance the search and retrieval process. Many of these programs are designed for what Tesch (1990) called descriptive-interpretive work rather than theory building, see Tesch (1991). For searching and retrieving, packages including GOFER, Metamorph Orbis, Sonar Professional, The Text Collector, WordCruncher, ZyINDEX, and FYI3000PLUS expand on the capacities of word processors in several ways (Weaver and Atkinson, 1994).

First, these packages create and manage the ethnographic database. Some of these packages manage files off-line (data remain in separate, un-altered text files); others manipulate the data directly. Usually, document processors work on documents that have already been produced in a word-processing package. Orbis manages files produced in XyWrite or NotaBene; MetaMorph and WordCruncher are particularly adept with WordPerfect documents. Others read files produced by a variety of word-processing, database, spreadsheet, and even drawing programs. Nearly all can manage plain text files, and some packages require files to be in this format before they can work with them.

The second value-added feature of document processors is their search features. As part of their management of the qualitative dataset, document processors allow the analyst to specify a variety of computer files in which to conduct a single search. ZyIndex, for example, searches documents that remain in their native format off-line, allows the analyst to keep track of changes to documents through several revisions, and indexes files so they can be readily included or excluded from particular searches. Document processors can mount complex searches: combinations or sequences of text strings; strings within specified proximity of each other; word synonyms, stems, and roots; and searches defined through Boolean, fuzzy, or set logic. Some display the results of searches interactively so that analysts can see how the addition or deletion of certain search terms in a complex search affects the number of hits produced.

Document processors are designed to make it easy for ethnographers to investigate data they have collected. Compared to word processors, document processors do a better job of placing the complete ethnographic dataset in the hands of the analyst. They allow the ethnographer to search more easily for desired pieces of text and to investigate how the text can be arranged in the dataset.

11.5.2DATA ORGANIZATION

Searching and retrieving allows the analyst to inspect but not alter the ethnographic database. However, CAQDA packages, such as askSam, Folio Views, MAX, Tabletop, HyperQual2, Kwalitan, Martin, QUALPRO, and The Ethnograph allow the analyst to alter the form of the ethnographic database by organizing its text.

Organizers expand on document processors in two ways: (1) Organizers allow the ethnobotanist to attach a structure to the database. Some document processors can retrieve text chunks in context. Organizers create context by giving analysts control over the structure of the database, and this structure can be manipulated and analyzed by the researcher. Organizers can also structure the database by adding database fields for factual information and for memos that are produced during analysis; and (2) Addition of organizers is the ability to code data according to a theoretical scheme developed by the analyst. Organizers are designed to tag chunks of text with analytical codes and to retrieve codes and tagged text. Retrieval of codes frequently includes the ability to search for multiple codes, to retrieve the text associated with codes, or to count codes.

11.5.3ORGANIZING AND ANNOTATING

Organizing and annotating are two basic tasks of qualitative data analysis. Some computer applications are designed to translate these activities with fidelity from hard copy to electronic form. For example, HyperQual2 and Martin use note cards as an organizing metaphor. Like their hard-copy counterpart, the note cards of these CAQDA packages each contain a single chunk of text. Electronic cards can be replicated and sorted into stacks, and these stacks then provide the raw materials to write up memos, annotations, and the ethnographic report. Another way to organize a hard-copy database is to use database-like fields. Fields can contain a wide variety of information including factual information that situates the ethnographic text to which it is attached (data collector, date of interview or observation, information about the subject of the note) or analytical information about the text itself. CAQDA software, such as askSam facilitates the creation, insertion, and organization of these fields. Once organized, these CAQDA programs can quickly search and retrieve information from database fields and quickly count and tabulate the results of these searches.

CAQDA packages that accommodate organizing and annotating the database are useful in a variety of situations, but they are particularly useful in research projects as they expand in size and scope. Multisite or multi-year ethnobotanical projects generate a plethora of notes that beg for efficient organization. Flexible annotations are particularly valuable in multire-searcher projects in that each researcher provides his/her own analysis and commentary.

11.5.4CODING, RETRIEVING AND COUNTING

Coding and retrieving is one of the central tasks of CAQDA software packages. Many of the software packages discussed above can code textual data, retrieve text based on applied codes, and tabulate which codes have been applied to which text. Most packages discussed in this section and below use coding and retrieving as their primary method of analysis or as a preface to other kinds of analysis. There are many ways to apply codes to text. Software, such as Kwalitan, QUALPRO, or The ethnograph number each line in the ethnographic database and apply codes to specific lines. Some packages encourage coding on the computer screen, whereas others encourage the analyst to code a numbered print-out of the text for later entry.

Once the codes are applied to the database, CAQDA software greatly accelerates analysis based on retrieving codes. Code-and-retrievers find codes using the same powerful features that document processors applied to the raw database. Multiple codes may be searched for at once. Hierarchies of codes can be established so that searches for higher-order terms also retrieve instances of lower-order terms. Complex searches can be formulated using Boolean, sequential, and proximity logic. Retrieval may yield a display of text associated with a code or a union of codes, or it may yield counts where those codes were applied. A number of CAQDA packages support cross-tabular displays of counts.

Organizing with CAQDA alters the ethnographic database in two ways. First, the database can be organized using database fields, hierarchical levels, or annotations so that the analyst has an easier time placing data in context and moving about in large ethnographic databases. Second, the database can be organized by applying codes to the text of the database so that the analyst can retrieve information from the database based on a theoretical mark-up of the text. CAQDA software facilitates the administration of both of these activities, but it does little to guide the intellectual work involved.

11.5.5SYMBOLIC MANIPULATION

There are three kinds of CAQDA software for symbol manipulation. Some symbol manipulators begin where code-and-retrievers leave off. These packages focus analysts’ attention on the coding process, encouraging them to create positive links between codes and to develop theory as they create a coding scheme. A second form of symbol manipulation is done by theory-building software. These packages take material that has been abstracted from the database through coding or other means and analyze relationships between codes or concepts. The final kind of CAQDA software that facilitates symbolic manipulation is hypothesis testers. These packages facilitate the advancement and testing of causal statements about relationships between codes or concepts in multiple cases in the database.

11.5.6VALUE-ADDED CODERS

The coding process already contains the seeds of symbol manipulation. Value-added coders add additional coding and analysis features to allow the analyst to move closer to the manipulation of concepts usually by moving further from the ethnographic text. Software packages, such as AQUAD allow the analyst to search purposefully through the ethnographic database for combinations of codes. The analyst can look for theoretically significant combinations of codes, tabulate the number of instances, and compare them to counts for combinations of codes that represent competing theories. Value-added coders consider the ethnographic database on a case-by-case basis so the counts and cross-tabulations they produce are a case-based numerical summary in contrast to the variable-based summaries provided by quantitative analysis.

A second way of transforming coding into symbol manipulation is to involve the computer in the construction of the coding scheme. Other value-added coders involve the computer in the coding process without imposing hierarchical constraints on the coding scheme. In ATLAS.ti, for example, the coding scheme is not constrained by the software but is retained to manipulate and analyze on its own. Text, codes, and memos can be linked in the program and these links later inspected and manipulated in conjunction with the original ethnographic text. Maps of relationships between elements in the database provide an analytical metaphor distinct from quantitative summary statistics or cross-tabulations.

11.5.7THEORY BUILDERS

Compared to value-added coders, theory-building CAQDA software moves the analyst a step further from the ethnographic text. Software packages, such as ETHNO, Inspiration, MECA, and MetaDesign are designed to facilitate the conceptual manipulation of ethnographic data. Theory-building CAQDA software packages do not actually construct theory, of course. They construct a graphical map (node and links) of data. Nodes represent data (field notes, memos, codes, etc.), and links represent relationships between data. Maps may help the analyst picture the project’s theoretical shape, the concepts in use, the relationship between those concepts, and the ethnographic data that have been collected regarding each of those concepts and links. Theory-building software facilitates experiments with different concepts and links within the research project.

But theory-building CAQDA packages need not be reserved for the armchair ethnographer idly speculating on abstract relationships in field data. Theory builders can also incorporate links to the original text that encourage grounding in the original data and checks on concept validity. In addition, theory builders need not be reserved for analyzes of a nearly finished research project (nor need they be the exclusive province of the principal investigator). Theory builders can aid researchers who are mapping complex empirical concepts or events during the course of fieldwork.

11.5.8HYPOTHESIS TESTING

Some value-added coders, such as HyperRESEARCH and AQUAD as well as stand-alone packages, such as QCA use hypothesis testing, the third form of symbol manipulation. Hypothesis-testing software bridges the gap between qualitative and quantitative analysis by facilitating case-based analysis of qualitative data. These packages allow the analyst to specify hypotheses based on codes applied to text (in HyperRESEARCH and AQUAD) or based on a descriptive matrix of cases (in QCA). Hypothesis testers determine how causally antecedent features of cases are related to outcomes. Boolean algebra is used to define the antecedent conditions for each case in the database. CAQDA software reduces large numbers of cases into statements that identify under what conditions the outcome of interest prevails.

Qualitative hypothesis testing determines what qualities of cases are crucial for a specified outcome. In contrast, quantitative hypothesis testing focuses on the contribution of different variables to the outcome. Apart from this difference, CAQDA packages that include hypothesis-testing features are similar to statistics software that dominates computer-assisted analysis of quantitative data. Hypothesis testers encourage the analyst to develop ideas in the form of equations (Boolean rather than arithmetic) and to investigate how different terms (binary codes rather than multivalve variables) in the equation affect its ability to accurately explain outcomes.

Stand-alone hypothesis testers remove the analyst from the original database. These software packages are useful in the analysis of data from a variety of sources and not only from ethnobotanical field studies. Hypothesis testers that include search-and-retrievers or data organizers may encourage the analyst to remain in contact with the database even as analysis proceeds along more abstract and quasi-quantitative avenues. Ideally, hypothesis-testing software allows the analyst to ensure reliability through hypothesis checking and to maintain validity by returning frequently to re-examine the original database and the codes, memos, and annotations that have accumulated over the course of the research project.

Symbol manipulation includes a variety of techniques for analyzing ethnographic data in ways that take advantage of microcomputers. Value-added coders encourage the analyst to develop explicit links between codes and data as the analysis proceeds. The software keeps track of the relationships between codes as they develop and then makes them available for later re-inspection and analysis. Theory builders facilitate exploration of concepts in research projects through graphical displays and the ability to quickly move between different levels of detail. Finally, hypothesis testers move CAQDA closer to the practices of quantitative research by embracing the goals of reliability and explanation. Hypothesis-testing packages may even allow analysts to strive for reliability and causal explanation without losing the traditional advantages of qualitative data with respect to validity.

11.6QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS (QDA) GENERAL APPROACHES

Many CAQDA software packages facilitate data analysis from the grounded-theory perspective. Grounded theorists advocate close contact with raw data, the emergence of analytical categories from the data through memo writing, and comparison as the primary analytical tool. Elements of grounded theory are common in CAQDA in part because Glaser and Strauss are explicit about the principles and procedures involved in this kind of analysis as stated by Straus (1987).

11.7SYSTEMIZATION OF ETHNOBOTANICAL METHODS

The use of CAQDA software makes explicit the methods of analysis used in converting ethnobotanical data into meaningful ethnobotanical reports. The explicit discussion of methods of analysis in the grounded-theory school midwifed the development of much CAQDA software. Computer-assisted analysis goes beyond discussion, however, by allowing researchers to share details of their analysis process. Even when ethical concerns prevent the sharing of raw data, the use of CAQDA may increase reliability by making explicit the concrete steps taken in moving from data to conclusion.

Secondly, the use of computers fosters increased reliability and general-izability by expanding the amount of data that can be managed and exhaustively analyzed within a single ethnographic project. Data expand rapidly in ethnographies involving multiple sites or multiple researchers.

CAQDA software may allow researchers to access large ethnobotanical databases directly without the theoretical intermediary of a single intellectual vision or research goal. The computer can accommodate data collected by multiple fieldworkers and facilitate coding, re-coding, linking, and re-linking by multiple investigators. Within this analytical space, differing understandings of the same database can be produced and compared, and analysts can examine the procedures undertaken to produce each account.

QDA that is consistent with grounded theory uses a sequential style of analysis that is highly data-intensive. Advocates of these methods urge the analyst to begin data analysis while collection is under way, to reduce the data using codes or categories, to shuttle between data and codes, and to compare coded and raw data to make tentative and ultimate conclusions. This analytical strategy returns the analyst to the database over and over again, and each step of analysis is readily translated into computer modules and procedures.

11.8STEPS AND BASIC CAPABILITIES OF CAQDA

11.8.1ENTERING DATA

Entering data into the computer is an important decision with enormous consequences. Which data are entered into the computer, how they are entered, and which remain outside the computer shape all further analyzes of the data. Data can enter a computer in a myriad of forms, from the “beginning” methods of text processing on a word processor to “advanced” methods of digital signal processing of videotape. Primary consideration for researchers entering text data into the personal computer is the size of the textual unit of analysis. Notes entered into a dedicated CAQDA package are divided into analysis “key words” which can be single words, lines of text, paragraphs, hypertext note cards, or larger files.

Especially important is the size of these key words as they are de-contextualized and re-contextualized during the analysis process. Larger and more elaborate key words of text are more likely to contain data falling into several analytical categories, and this may complicate analysis.

On the contrary for those interested in context-dependence, smaller key words may prove worthless unless to the CAQDA software as it contains elaborate coding or linking procedures. Practical issues also arise at the data-entry stage. Specialized and non-relevant field notes, interview transcripts, and memos can create many user-based confusions leading to greater errors in the final outcome.

11.8.2ORGANIZING DATA

The organization of data depends upon the research and its objectives. The number of researchers involved in the project, the number of field sites, the variety of data types, and the theoretical orientation of the researchers all influence how the dataset is organized. The end users, for example, the researchers have to familiarize themselves with basic and software use.

11.8.3SEARCHING FOR AND RETRIEVING DATA

Another axillary use of CAQDA is that it enhances the researcher’s ability to search for and retrieve text. Search and retrieval surely does not mean the end of the computer’s usefulness as a qualitative data analyst though several CAQDA packages are designed for this kind of analysis. CAQDA software usually allows researchers to search for root forms of words or synonyms, use combination searches, such as those based on word proximity or word order. Retrieval of searched-for items is usually dependent on the keywords.

11.8.4CODING OR INDEXING DATA

Coding is a most important feature of CAQDA. The use of the computer does not affect the fundamentals of data coding. The field notes has to be manually coded before entering the data into their CAQDA package. Since coding is more of a mechanical process and require less intellect of the researcher, CAQDA are best useful in this step.

The disadvantage of computer assistance is that it can impose limitations on the coding process creating problems for ethnographers. Analysts must be confident that using the computer facilitates their work.

11.8.5ANALYZING CODES

Analysis of codes starts simultaneously as the first data are coded. Codes are defined in relationship to each other, so their application to a set of data implies theory. CAQDA software can make this implicit theory explicit by generating a list or map of codes and their relationships. Some packages constrain the development of a coding scheme to encourage the analyst to make positive connections between codes, such as hierarchical connections between more and less inclusive ones or sequential connections between coded events.

Once sufficient data have been coded, other analytical possibilities develop. In most CAQDA packages, analysts search for codes as easily as they explore raw data. Packages that retrieve text associated with particular codes or conjunctions of code may be useful for analysts interested in interpreta-tional analysis.

Apart from data entry, the analysis of codes is the area of the computer’s greatest influence on theory and methods. Software design may force the analyst to consider the previously unexamined relationship between concepts in the research project. The flip side of the coin is that software may limit the ability of the analyst to develop theory in desired directions. The ability to mount comprehensive searches for codes /sets of codes means that the ethnographic analysis may benefit from less bias. But large-scale searches can also bury the analyst in chaotic results. In short, the computer-assisted analysis of codes has theoretical and methodological implications surpassed only by those taken during the first steps of data entry.

11.8.6LINKING DATA

Software available during the last decade permit analysts to create hypertext links between combinations of data, codes, memos, and research reports. Graphics, sound, and video may also be incorporated into “ hyperspace” databases as sited by Weaver and Atkinson (1994).

Analysis based on data linking is most useful for ethnobotanists who collect non-textual data, especially if hypertext moves out of the researcher’s office and becomes a medium for the distribution of research reports. For researchers working outside of the positivistic tradition, linking data may be particularly valuable. Hyperlinks concretize nonlinear data-analysis techniques and free the researcher from reliance on computation. Reports that incorporate graphics sound, and video can more readily make the case for the significance of context.

But hypertext technology also imposes special limitations on analysts. At present, the incorporation of text into hypertext “spaces” is inevitably fraught with more burdensome formatting limitations than those imposed by traditional text databases. Integrating sound or video into an ethnographic database involves technological expertise beyond the use of the word processor. In addition, the publication of materials using sound or video technology may introduce new ethical considerations, such as the protection of research subjects’ confidentiality.

11.8.7ANALYZING LINKS

Analyzing links within the database is a more general form of analyzing codes. Links may be analyzed only after a certain number have been established in the data. Once established, the links may be abstracted from the original data and analyzed as a system or network of their own. Compared to the analysis of codes, the analysis of links is more flexible and general. Greater complexity is possible in hypertext links than in coding schemes, so the representation of linked data may consequently be more complicated.

11.9TYPES OF SOFTWARES USED IN ETHNOBOTANY

11.9.1AQUAD

The first version of Analysis of Qualitative Data (AQUAD) was developed in Germany in 1987 to compensate for a shortage of manpower in research projects. At this time several programs for qualitative analysis had been in existence for a number of years. Simpler types of software tools were using the search function of available word processors or database programs. Some were already designed for the special demands of qualitative analysis, although they did not offer more than simple counting and retrieval functions. This program made use of the rich potential of so called “ logical programming”, and it was the stimulus and model for AQUAD.

In all qualitative analyzes following the “coding paradigm” the main task is to reduce the usually wordy and redundant descriptions, explanations, justifications, field notes, protocols of observations, etc., that comprise the researcher’s data texts to some kind of systematic description of the meaning of the data.

AQUAD is a program for the generation of theory on the basis of qualitative data. Since theory-building and hypothesis-testing have been traditionally the domain of researchers who work with quantitative data, theoretical notions based on qualitative data are easily distrusted. Although we acknowledge (and have no desire to claim otherwise) that qualitatively developed statements do not achieve the same degree of generalization as sta-tistically tested statements, it is important to make sure qualitatively developed conclusions are based on as rigorous a verification process as possible. Therefore, special emphasis is placed in AQUAD on objectivity, reliability, and validity. The researcher is encouraged to use procedures, such as the repeated interpretation of the same text by the same analyst or by different analysts over time, or to pay attention to issues of internal validity, such as whether the categories have been used consistently, whether their defined range of meaning has been maintained, whether the meanings represented by specific categories indeed correspond to the content of the text passages that are sorted into them, etc.

More information about these issues will be presented later in this paper. Finally, two more attributes of AQUAD deserve attention. Unlike many other qualitative analysis programs, AQUAD supports some versions of conventional content analysis or linguistic analysis by allowing the user not only searching for words and phrases that occur in the data text and examine their frequency, but the program can extract words together with their context (key word in context – KWIC – indexes).

Furthermore, AQUAD provides for the attachment of researcher memos to text segments. Principally empirical research follows a path towards discovery that starts from descriptive or categorical analyzes and leads via postulating or observing regularities to statements, which explain these connections at least tentatively. No matter whether an analysis results in a taxonomic, correlative or causal order of the phenomena under study, the process of research is focused on reduction that is reducing concrete details and moving to higher levels of abstraction and generalization. That will enable one to see the essentials. AQUAD tries to contribute to this goal, but at the same time able to keep open the way back to the manifold, concrete, and colorful details of the original database.

11.9.1.1UTILITIES OF AQUAD (SEE, HTTP://WWW.AQUAD.DE/EN/)

AQUAD facilitates the tools of content analysis as under:

•Text searching: AQUADs basic utility is looking for segments in texts. Keywords can be entered and the AQUAD search engine can be used to search related results.

•Retrieving by file name, code, keyword, or parts of memo texts: Retrieving segments according to criteria.

•Coding: Labeling segments in texts, audios, photos, or videos can also be done in AQUAD

•Annotation: Inserting annotations linked to parts or whole texts, audios, photos, or videos. This facilitates in easy analysis of the data and thus developing a theory.

•Construction of linkage hypotheses: Linking data to reach a conclusion is most important feature for any analysis tool. AQUAD looks for relationships among codes.

•Comparison of cases/files: contrasting coding among files.

•Word analysis: Counting words according to criteria can also be accomplished using AQUAD.

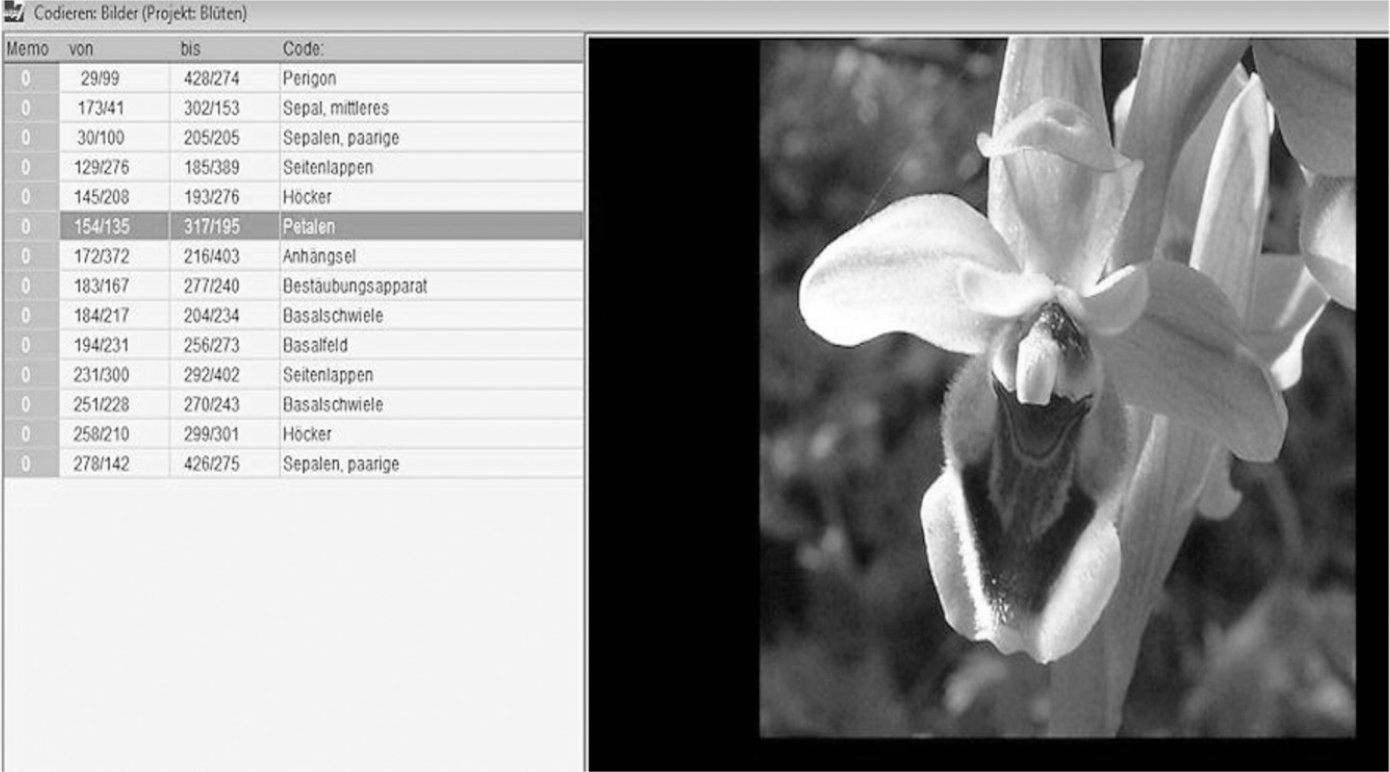

FIGURE 11.1Constructing tables combining criteria and arranging data in rows (Source: http://www.aquad.de/en/; used with permission.)

11.9.2CODING ANALYSIS TOOLKIT

Coding Analysis Toolkit (CAT) (see, http://cat.ucsur.pitt.edu/) is a free service of the Qualitative Data Analysis Program (QDAP), and hosted by the University Centre for Social and Urban Research, at the University of Pittsburgh, USA and QDAP-UMass, in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, USA. CAT was the 2008 winner of the “Best Research Software” award from the organized section on Information Technology and Politics in the American Political Science Association. It is a web-based suite of CAQDAS tools.

CAT is able to import ATLAS.ti, which is a computer program used mostly, but not exclusively, in qualitative research or qualitative data analysis.data, but also has an internal coding module. It was designed to use keystrokes and automation as opposed to mouse clicks, to speed up CAQDAS tasks.

11.9.3.COMPENDIUM

Compendium is open source like those latter products but it is driven by an academic institute rather than commercial or hobby interest. From a practical point of view Compendium is more than a mind mapping product, something larger and more ambitious a framework for capturing the connections between information and ideas.

Compendium (see, http://www.graphic.org/mind-mapping-software/compendium-review.html) is developed in KMi, in collaboration with various US partners, and funded from externally secured research grants.

The builders of Compendium have provided a number of screen cast movies on their website which take us through the initial concepts contained within the program. They are well worth viewing as a quick way to get to know the software.

11.9.3.1DATABASE DRIVEN (SEE, HTTP://COMPENDIUM.OPEN.AC.UK/INDEX.HTML)

The program starts up with an invitation to create a user account and then an initial mind map. This is the first sign that Compendium is built from the ground up using a database to provide a multi-faceted collaborative tool. Most mind mapping software has had collaboration capability bolted on as the internet has become faster and more reliable but this is not the case with Compendium.

11.9.3.2MAP CREATION

After following the initial screencasts one will be able to create maps. These are completely freeform and there are a number of different types of nodes (node appears to be the chosen term for an item in most mind mapping programs). As Compendium is a tool for mapping ideas, discussions and problems the nodes are more specialist than in pure mind mapping tools. You can add a node that asks a question, answers it or ascribes positive or negative attributes to another node. There are also decision making and argument nodes.

11.9.3.3CONTEXT CLICK CONSISTENCY

There is some inconsistency as to when an area or a node is in focus (in terms of the mouse) This means one sometimes fail to get response to a mouse click and have to repeat it after waiting to realize that nothing’s going to happen. This is the sort of minor irritation that open source users have to live with which wouldn’t happen with a commercial product. Having said that there is a full and comprehensive set of keyboard shortcuts for almost any task and they are all listed in sections in the Help file.

11.9.3.4CONNECTING LINKS

One difference with Compendium over other mind mapping products is that lines connecting the nodes aren’t drawn in automatically as nodes are created. They are dragged into place with a right-click (ALT+mouse button for Mac users) once the nodes are in place. This makes map creation slightly slower than with a package like XMind, which connects nodes at creation, but allows complete and absolute freedom as to where lines should go, with multiple end and starting points no problem at all.

11.9.3.5NODE PROPERTIES

The nodes can have all properties ascribed to them, comments, tags, etc. Tags show some of the power that Compendium has behind the maps that can be drawn. There is a group of pre-assigned tags provided with the package but also the ability to add your own. Once items have been assigned relevant tags, or perhaps updated after a project meeting, you can search on those tags (as well as other properties) to find all nodes with that tag, not only in the current mind map but across however many maps you can get access to.

11.9.3.6BELLS AND WHISTLES

Compendium has some neat tricks as well. One can overlay a map on top of an image to add notes and graphics to it. This allows one to, for example, annotate satellite maps or highlight items on a picture of a circuit board. These tasks normally need knowledge of a complex graphics program but with Compendium it is straightforward. Setting Text on mouse over is very useful too. If care is taken over the text chosen this can be used effectively so that people looking at a mind map can get the overall picture before delving down into the layers that will specifically interest them.

11.9.3.7COMPENDIUM CONCLUSIONS

Compendium has the mind mapping concept at its heart is much more than a tool to draw and update mind maps. Many people use Compendium as an organizer for research projects or even their lives and its ability to link to almost any object certainly lends itself to this. The downside is that one need to use Compendium as the link between all activities. Compendium visually represents thoughts and illustrates the various interconnections between different ideas and arguments. The creation of “issue maps” graphically represents the relations between issues and questions and facilitates the understanding of interconnected topics through pictorial representation.

It can be used by a group of people in a collaborative manner to convey ideas to each other using visual images.

11.9.4ELAN AND ANNEX

ELAN is written in the Java programming language as a local tool and stores the transcription data in a specialized XML format, EAF (ELAN Annotation Format). It is available for Windows, MacOS X and Linux. On Windows and Mac it dele- gates the media playback to an available high performance native media framework: DirectX/DirectShow or QuickTime on Windows and QuickTime on Mac. On Linux JMF is used. Due to its reliance on native media solutions it can provide frame-accuracy in particular on Windows systems.

ANNEX is written as an ELAN compliant server-based tool relying on streaming media via the combination Darwin media streamer and Quicktime client. Due to the used Internet protocol ANNEX cannot provide the same high timing accuracy as ELAN. While ELAN creates a local index for content searches on physical directory structures, ANNEX works with an index created for a whole Language Achieve Management and Upload System (LAMUS) archive using the Postgres database system. ELAN and ANNEX have the following major features (see, https://tla.mpi.nl/tools/tla-tools/annex/attachment/annex-elan_flyer_2006-05-11/):

•Association of up to 4 videos to a transcription document and synchronized viewing;

•Accurate alignment of annotations to the media, with maximum pre-cision of 1 millisecond;

•Creation of unlimited number of tiers (layers) and unlimited number of annotations;

•Free selection by the researcher of the tier structure and the values to be used on these tiers;

•Tiers can be grouped hierarchically; different types of dependencies between tiers can be defined;

•Multiple, customizable views on tiers and annotations;

•Specialized viewer for time series data, such as from cyber gloves;

•Creation and use of controlled vocabularies;

•Import modules for Shoe-box/Toolbox, Transcriber, and CHAT, export to Toolbox and CHAT, tab-delimited text and interlinear text;

•Highly customizable, inter-linear-style printing of the transcript;

•Versatile structured and unstructured search options;

•Productivity enhancements, such as semi-automatic segmentation, to kenizing, copying of tiers, keyboard shortcuts;

•Multiple undo and redo;

•Support for templates;

•Input methods for different character sets, such as IPA, Chinese, Hebrew, Arabic, etc.

•Multilingual user interface;

•Adheres to standards like XML and Unicode.

11.9.5TAMS ANALYZER

TAMS stand for Text Analysis Markup System. It is a convention for identifying themes in texts (web pages, interviews, field notes). It was designed for use in ethnographic and discourse research.TAMS Analyzer is a program that works with TAMS assigns ethnographic codes to passages of a text just by selecting the relevant text and double clicking the name of the code on a list. It then allows extracting, analyzing and saving coded information. TAMS Analyzer is open source; it is released under GPL v2. The Macintosh version of the program also includes full support for transcription (back space, insert time code, jump to time code, etc.) when working with data on sound files (Figure 11.2).

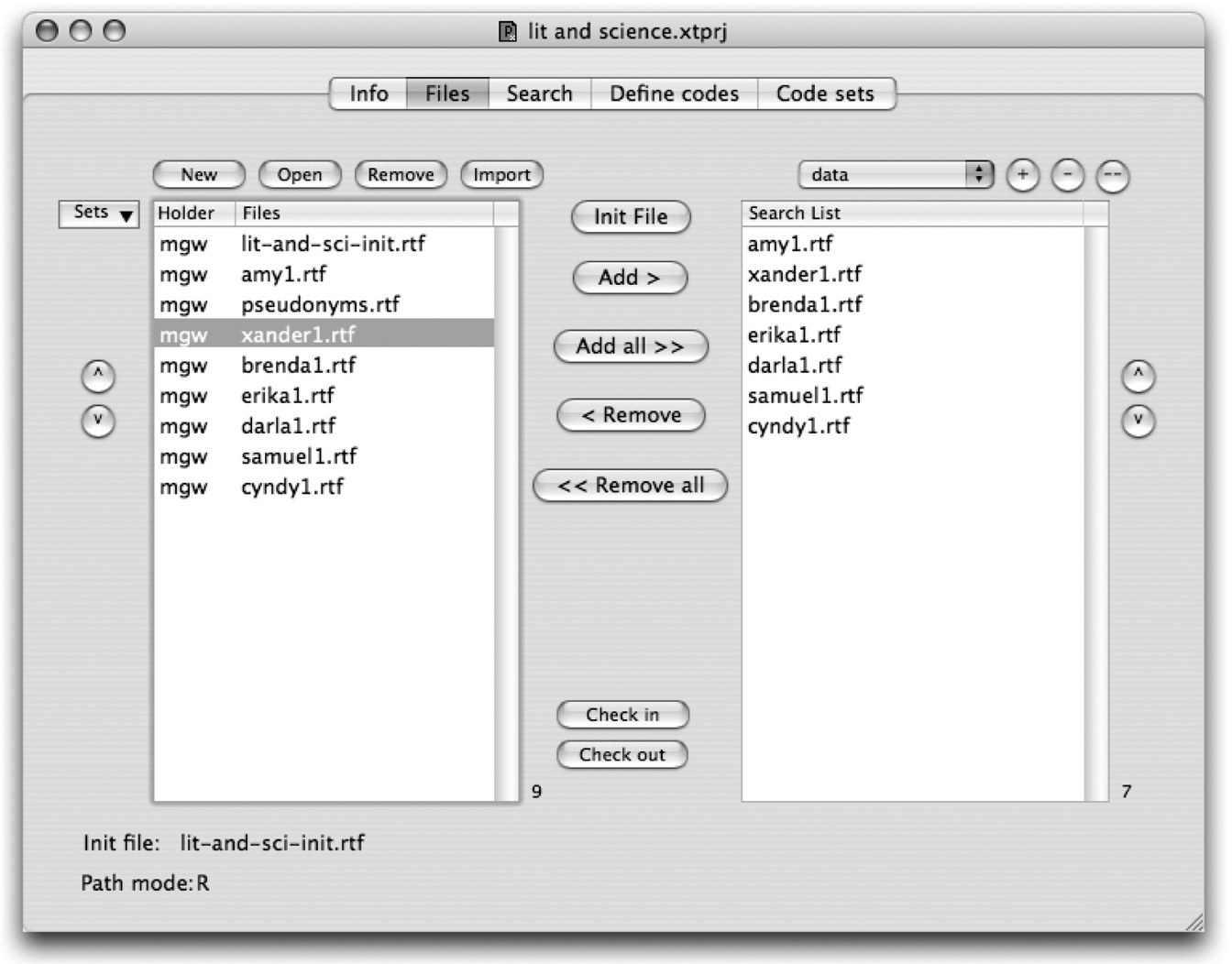

FIGURE 11.2Project window (source: http://tamsys.sourceforge.net/).

11.9.6QDA MINER

QDA Miner is a mixed methods and qualitative data analysis software developed by Provalis Research. The program was designed to assist researchers in managing, coding and analyzing qualitative data QDA Miner was first released in 2004 after being developed by Normand Peladeau. The latest version-4 was released in December 2011. QDA Miner is widely used software for qualitative research and used by market researchers, survey companies, government, education researchers, crime, fraud detection experts, journalists, etc.

Structure of work in QDA Miner QDA Miner functions using an ‘Internal Database Structure’ so that the documents are imported into the database and all the workings are held in about six project files. This will vary according to the types of data being stored. Being designed for the management of mixed-methods projects, QDA Miner and its sister programs can handle large amounts of data in a variety of formats. Data can be imported or a project file can originate and be structured directly from spreadsheet applications, when for example analyzing open-ended survey questions. The ability to archive and compress the project file facilitates the backing up and movement of projects. The compression reduces file size to between 15% and 20% of the original. The QDA Miner interface is divided up into resizable areas, with lists of variables, documents and codes and the main document window (with coded margin) are viewable simultaneously throughout.

11.9.6.1VARIABLES STRUCTURE

QDA Miner operates using a cases and variables structure which is unusual amongst CAQDAS packages. The variable values of the currently selected case are displayed adjacent to the data along with the case from which the data derives and the main codes list. A new project can be created in number of different ways, for example, from a list of documents; from a database/spreadsheet containing quantitative variables; using a document converter, etc.

Variables act as holders for different types of qualitative/categorical and quantitative information. New document type variables can be added at any time to handle additional types of data, for example, notes for each case.

Variables of various types (e.g., numeric, nominal, ordinal, Boolean, string) are used for case filtering and comparison. This information can be imported from a spreadsheet.

Structure of work in QDA Miner QDA Miner functions using an ‘internal database structure’ so documents are imported into the database and all the workings are held in about six project files. This will vary according to the types of data being stored. Being designed for the management of mixed-methods projects, QDA Miner and its sister programs can handle large amounts of data in a variety of formats

Data can be imported or a project file can originate and be structured directly from spreadsheet applications, when for example analyzing open-ended survey questions. The ability to archive and compress the project file facilitates the backing up and movement of projects. The compression reduces file size to between 15% and 20% of the original. The QDA Miner interface is divided up into resizable areas, with lists of variables, documents and codes and the main document window (with coded margin) are viewable simultaneously throughout.

Data types and format in QDA Miner Textual formats: QDA Miner directly stores text saved as ‘rich text format’ (rtf) and ASCII (txt). However, the Document Conversion Wizard can convert various file formats, such as MS Word, WordPerfect, HTML, Adobe Acrobat to work with inside the software. Textual data is fully editable using standard Windows formatting toolbars. Objects, such as tables and graphic elements can be embedded into rtf documents

QDA Miner can also convert projects created in other CAQDAS packages, including ATLAS.ti, HyperRESEARCH and NVivo.

11.9.6.2DATABASE FORMATS

Several database and spreadsheet file formats (including MS Access, Excel, dBase, Paradox) and any data file with an ODBC driver (Oracle, MS SQL, etc.) can also be imported.

11.9.6.3CODING PROCESSES IN QDA

Miner Codes can be assigned to any segment of text, to one or several table cells, or a whole graphic or another embedded object. Drag and drop codes on to text or double click on a code to assign it to selection. Codes can be applied to whole paragraphs without manual text selection by drag and drop.

11.9.6.4DATA ORGANIZATION IN QDA MINER

Documents are organized by Cases for filtering purposes. Cases can be grouped and ordered according to selected variable values, and these order-ings follow through to generated outputs. Any numerical, categorical, logical and date data may be used to categorize cases, which can be automatically assigned upon data import. QDA Miner can handle more than 2000 variables and several million cases.

11.9.6.5OUTPUT IN QDA MINER

Tabular outputs can be printed or exported to Excel, HTML, comma or tab-delimited files. Coding retrieval results may also be exported as a new QDA Miner project. Text reports may be saved to disk in Rich Text, MS Word™, ASCII or HTML format. Various graphical displays can be generated and exported, for example, cluster plots, heat maps, etc. Export to BMP, WMF, PNG and JPG format. Whole project export to spreadsheet and database file formats, for example, Quattro Pro, Lotus, Excel, Paradox, dBase.

11.9.7HyperRESEARCH

HyperRESEARCH is used by qualitative researchers in areas, such as health care, legal, sociology, anthropology, music, geography, geology, education, theology, philosophy, history, market research, focus group analysis and most other fields using qualitative research approaches. This is designed to assist with any research project involving analysis of qualitative data. It’s easy to use and works with both Mac and Windows computers. So when collaborating with multiple researchers, everyone gets to use their preferred computer. HyperRESEARCH is powerful, and flexible, which means that no matter how the data is approached, the software allows one to “do it your way.”

HyperRESEARCH helps analyze almost any kind of qualitative data, whether it’s audio, video, graphical or textual. The intuitive interface and well-written documentation – and especially the step-by-step tutorials – help get you up and running with your own data quickly and easily (see, http://www.researchware.com/).

HyperRESEARCH enables coding and retrieval of source material, theory building, and analyzes of data. With its multimedia capabilities, HyperRESEARCH allows to work with text, graphics, audio, and video sources. HyperRESEARCH has been in use by qualitative researchers since it was first introduced in 1991 by Researchware, Inc./rHyperRESEARCH is fully cross-platform. The overviews of various features are given below (see, http://www.researchware.com/):

•Easy-to-use interface: offers the same intuitive case-based interface on all supported platforms. It provides a turnkey solution by employing a built-in help system and several tutorials with step-by-step instructions.

•Flexible methodologies: supports Case-base or Source-based qualitative methodologies or combinations. With flexible organization of codes from any source to any case, support for code frequencies and other code statistics, HyperRESEARCH is well suited for mix-method approaches to qualitative research.

•Fully Cross-Platform: designed from the ground up to work well on Microsoft Windows and Apple’s OS X. The HyperRESEARCH study file format and all of the various media types supported will work across operating systems.

•Multi-Media capabilities: allows you to work with text, graphics, audio, and video source material in many popular formats.

11.9.8MAXQDA

MAXQDA is professional software for qualitative and mixed methods data analysis for Windows and Mac, which are used by thousands of people worldwide (see, http://www.maxqda.com/products/maxqda).

Released in 1989 it has a long history of providing researchers with powerful, innovative and easy to use analytical tools that help make a research project successful.

11.9.8.1ORGANIZE AND CATEGORIZE YOUR DATA

The clearly structured user interface of MAXQDA is divided into four windows, which reflect essential work areas in the process of qualitative data analysis and allow intuitive handling.

Data can be imported from interviews, focus groups, online surveys, web pages, images, audio and video files, spreadsheets, and RIS data easily. Attach post-it like notes (memos) and sort your data into groups.

a.Code and Retrieve

Mark important information in your data with different codes by using regular codes, colors, symbols, or emoticons.

Organize your thoughts and theories in memos and stick them to any element of your project.

Retrieve coded segments quickly and efficiently and make use of powerful search tools with automatic coding options.

bCode and Transcribe Audio and Video Files

The MAXQDA Multimedia Browser enables to code audio and video files directly without having to create a transcript. The coded segments are treated like any other segments in MAXQDA. You can retrieve, com-ment and assign a weight to these segments in the same way as with other segments. Advantage: MAXQDA-11 has extended transcription functions with which you can adapt the speed or the sound volume of your audio and video files.

c.Mixed Methods

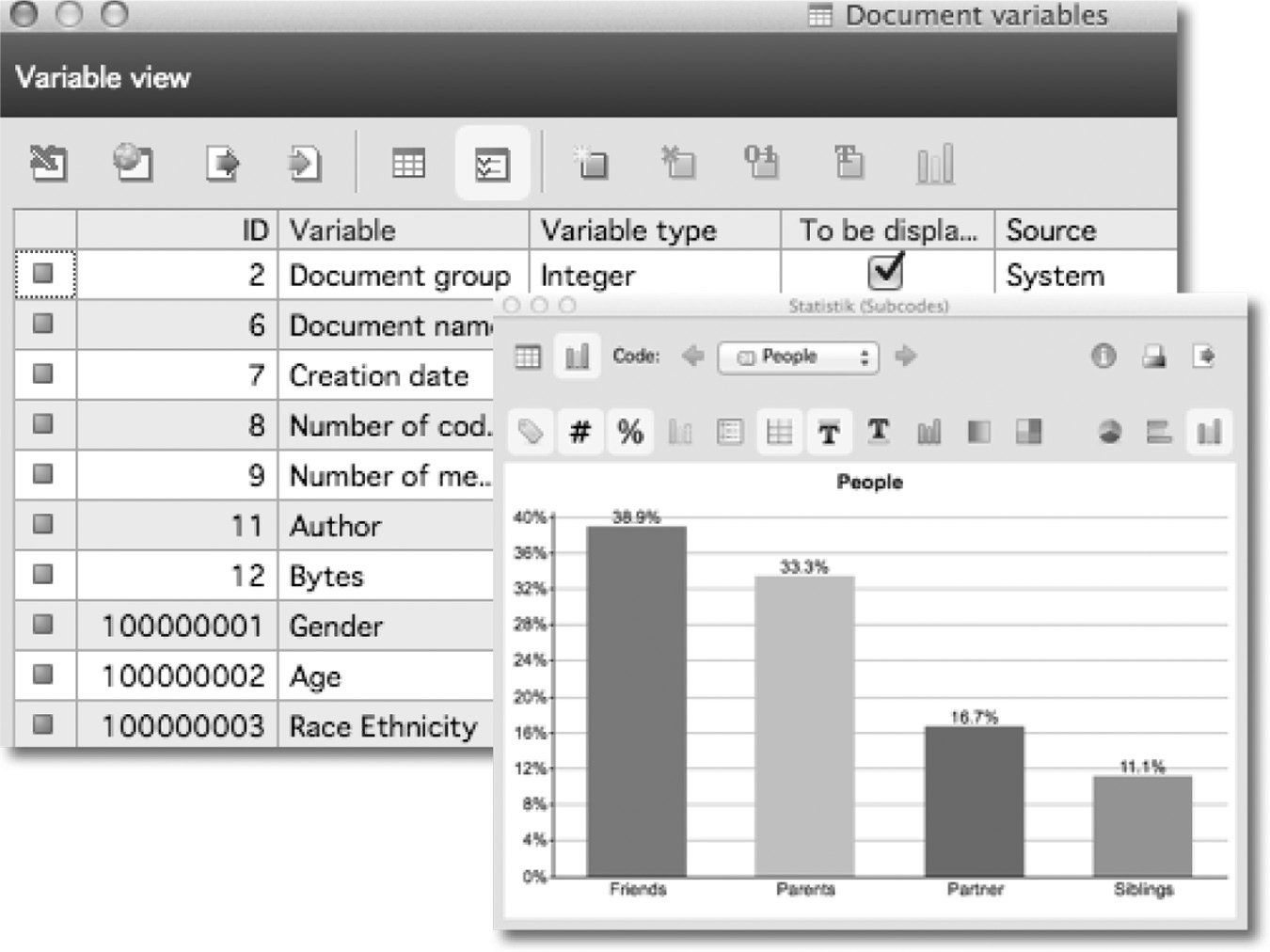

MAXQDA offers a lot of helpful Mixed Methods functions to complete your data analysis Integrate quantitative methods or data into your project. MAXQDA offers excellent Mixed Methods features to include variables or to quantify the results of your qualitative analysis (Figure 11.3).

11.9.9NVIVO

NVivo is software that helps you easily organize and analyze unstructured information, so that you can ultimately make better decisions (see, http://www.qsrinternational.com/products_nvivo.aspx).

FIGURE 11.3Database interface of MAXQDA (Source: http://www.maxqda.com/products/maxqda; used with permission.)

Whatever the materials, whatever the field, whatever the approach, NVivo provides a workspace to help at every stage of project – from organizing your material, through to analysis, and then sharing and reporting.

NVivo is a qualitative data analysis (QDA) computer software package produced by QSR International. It has been designed for qualitative researchers working with very rich text-based and/or multimedia information, where deep levels of analysis on small or large volumes of data are required.

NVivo is used predominantly by academic, government, health and commercial researchers across a diverse range of fields, including social sciences, such as anthropology, psychology, communication, sociology, as well as fields, such as forensics, tourism, criminology and marketing uses (see, http://www.qsrinternational.com/products_nvivo.aspx).

From health research and program evaluation, to customer care, human resources and product development – NVivo is used in virtually every field. Yale University, USA, World Vision Australia, the UK Policy Studies Institute and Progressive Sports Technologies all use NVivo to harness information and insight.

For individuals use NVivo to:

•Spend more time on analysis and discovery, not administrative tasks.

•Work systematically and ensure don’t miss anything in data.

•Interrogate information and uncover subtle connections in ways that simply aren’t possible manually.

•Rigorously justify findings with evidence.

•Manage all material in one project file.

•Easily work with material in own language.

•Effortlessly share work with others.

For organizations use NVivo to:

•Get the most out of your data – from customer and employee feedback to information about product performance – to make new discoveries and ultimately, better decisions.

•Easily manage your information and enhance internal workflow and reporting processes.

•Deliver quality outputs backed by a transparent discovery and analysis process.

•Justify decision making with sound findings and evidence-based recommendations.

•Revisit data easily. Build up the big picture over time.

•Increase productivity and reduce project timeframes.

NVivo is intended to help users organize and analyze non-numerical or unstructured data. The software allows users to classify, sort and arrange information; examine relationships in the data; and combine analysis with linking, shaping, searching and modeling. The researcher or analyst can test theories, identify trends and cross-examine information in a multitude of ways using its search engine and query functions. They can make observations in the software and build a body of evidence to support their case or project.

NVivo accommodates a wide range of research methods, including network and organizational analysis, action or evidence-based research, discourse analysis, grounded theory, conversation analysis, ethnography, literature reviews, phenomenology, mixed methods research and the Framework methodology. NVivo supports data formats, such as audio files, videos, digital photos, Word, PDF, spreadsheets, rich text, plain text and web and social media data. Users can interchange data with applications like Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Word, IBM SPSS Statistics, EndNote, Microsoft OneNote, SurveyMonkey and Evernote; and order transcripts from within NVivo projects, using TranscribeMe.

9.9.10QIQQA

Qiqqa (pronounced “Quicker”) is a freeware and freemium reference management software that allows researchers to work with thousands of PDFs. It combines PDF reference management tools, a citation manager and a mind map-brainstorming tool. It integrates with Microsoft Word XP, 2003, 2007 and 2010 and BibTeX/LaTeX to automatically produce citations and bibliographies in thousands of styles. Researchers and research groups can store, synchronize and collaborate on their PDF documents, annotations, tags and comments using the internet cloud-based Qiqqa Web Libraries.

Key Features (see, http://www.qiqqa.com/)

•Rich PDF viewer supporting annotating, tagging, notes, searching and cross-referencing.

•Filtering and reporting against your tags, autoTags and aiTags.

•A full-text search across your entire PDF library.

•The tagging of text annotations and the associated annotation report features enables Qualitative research and Grounded theory methodologies against your PDF documents and scans.

•Automatic extraction of paper metadata and integration with GoogleScholar to automatically build the rest of your citation metadata.

•Sync your documents, metadata and annotations across multiple computers and to a private online Web Library.

•Integration with web browsers to support searching of the internet for new PDFs to add to your document library.

•Optical character recognition (OCR) of PDF documents to support text searching of scanned PDFs.

•Text and image export text export for PDFs (including scanned PDFs)

•Automatically generate your citations and bibliographies in Microsoft Word XP, 2003, 2007 and 2010 with support of thousands of Citation Style Language (CSL) styles.

•BibTeX export to allow researchers using LaTeX to format their lists of references in a consistent manner, for example, using LyX.

•Integrates with the built-in Microsoft Word 2007 and 2010 reference management systems.

•A brainstorming tool allowing you to incorporate your ideas, PDF documents, annotations and information on the internet.

•Import your PDFs and metadata from other reference managers.

11.9.11f4ANALYZE

f4ANALYZE supports you in analyzing your textual data. You can develop codes, write memos, code (manually or automatically), and you can analyze cases and topics. The program is slim and easy to learn – you’ll greatly speed up your work. f4analyze is an inexpensive, easy-to-learn QDA software for research projects with up to 30 texts. It supports your analysis of word processing files by providing functions for coding, memoing, retrievals, and frequency analyzes. Our reference manual is only 12 pages long because f4analyze focuses on core functions. This is a guarantee for an easy start. We have put emphasis on user-friendliness on all operating systems. (see, http://www.audiotranskription.de/english/f4-analyze)

Coding Text

Codes help to structure your texts. No matter if codes are developed inductively or deductively, you can effortlessly create and organize your code system in f4analyze. Different colors can be assigned to the codes – if a segment of text is coded, it will appear in the same color as the respective code. Clicking on a code in the code list retrieves all coded passages in a well-arranged list.

Text filter and retrieval

With a few clicks one can start a word search in both texts and comments. To retrieve certain statements or segments in texts, simply click on the desired codes and the texts that should be searched. One can further bundle your texts in text groups – for example, if one specifically wants to search through statements by academics from Wisconsin (as opposed to searching through statements from academics all over the US). Everything can be exported to RTF.

Code distribution

In the code distribution table, you can display the coding frequency in total numbers. The segments of text assigned to the respective codes can also be directly displayed in the table. Frequency numbers as well as text segments can be exported as a CSV file.

Open software tool

Your data is stored in a single project file – you can export everything from this file in case you want to work in Word, MAXQDA or ATLAS.ti at a later point. f4analyze supports export as text file and as a table for parts of the project. The whole project can be exported as an XML-file. f4analyze runs on Windows & Linux machines, as well as on Macs, and is available in English and German. In f4analyze, YOU decide where and how you want to work.

11.9.12XSIGHT

XSight was released in 2006 and supported until January 2014. Developed by QSR International for qualitative data analysis (QDA), it is a tool for researchers or individuals who are undertaking short-term qualitative research analysis on projects involving non-numerical data. Qualitative research can encompass business intelligence, marketing research or data analysis. (see, http://students.pugh.co.uk/index.php?nID=productDetail&manu=63&prodID=1079).

This was superseded by NVivo 10 for Windows, which offers equivalent functionality with greater flexibility and enables researchers to work with more data types likes PDFs, surveys, images, video, audio, web and social media content. XSight software assists researchers or other professionals working with non-numerical or unstructured data to compile, compare and make sense of their information. It provides a range of analysis frameworks for importing, classifying and arranging data; tools for testing theories and relationships between items; and the ability to visually map and report thoughts and findings.

Designed for rapid analysis, XSight can handle small or large volumes of data and search and query tools support the review and reflection process and users can look for patterns, make comparisons, and interrogate the data in seconds. XSight is used predominantly by commercial market researchers, but also by professionals and students in a diverse range of areas, from health and law to telecommunications and tourism. It is useful for evaluating a variety of information to review results and draw conclusions. Some examples of uses include tracking customer satisfaction, testing an advertising campaign, researching new packaging or even evaluating information garnered in research, such as community consultation projects.

11.9.13ATLAS.TI

ATLAS.ti is a powerful software package for the visual qualitative analysis of large bodies of textual, graphical and audio or video material. It offers a variety of tools for accomplishing the tasks associated with any systematic approach to fieldwork material. ATLAS.ti helps you to uncover the complex phenomena hidden in your qualitative data, offer a powerful and intuitive environment for coping with the inherent complexity of tasks and data, and keeps you focused on the data under analysis. For a comparison between ATLAS.ti and N6, the reader may refer the paper by Barry (1998).

11.9.14THE ETHNOGRAPH

The Ethnograph v5.0 is a versatile computer program designed to make the analysis of fieldwork material easier, more efficient, and effective. It is possible to import text-based qualitative material, typed up in any word processor, straight into the program. The Ethnograph helps to search and note segments of interest within fieldwork material mark them with code words and run analyzes which can be retrieved for inclusion in reports or for further analysis.

11.9.15N6 BY QSR

N6 is the latest version of the NUDIST software. It combines efficient management of fieldwork material with powerful processes of Indexing Searching and Theorizing.

Designed for researchers making sense of complex material, N6 offers a complete toolkit for rapid coding, thorough exploration and rigorous management and analysis. With a full command language for automating coding and searching, and a Command Assistant that formats the command for you, N6 powerfully supports a wide range of methods. Its command files and import procedures make project set up very rapid, and link qualitative and quantitative data. Tolerant of large data sets, it ships with QSR Merge, which seamlessly merges two or more projects (N4, N5 or N6) for teams or multi-site research.

For a comparison between ATLAS.ti and N6, the reader may refer the work of Barry (1998).

11.10RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN COMPUTER APPLICATIONS IN ETHNOBOTANY

Many ethnobotanists are using more unconventional methods to create a database. The FLAAR staff utilizing a special 3D scanner training course at Z Corp learned how to handle the portable ZScanner 800 and how to process the data from it.

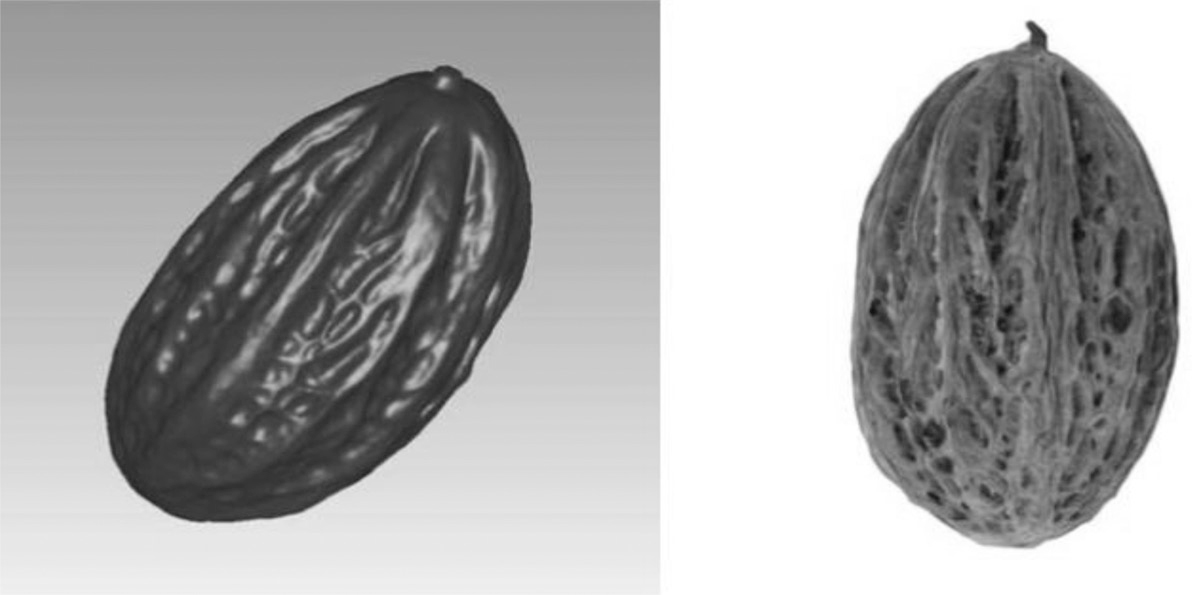

The report shows the processing of two pataxte pods. The pataxte is what is left after removing the cacao, which is the fruit from where the chocolate is made. Using the leftover pataxte pods, they tried to reconstruct the entire fruit using 3D scanning (Figures 11.4 and 11.5).

FIGURE 11.4Figure showing the morphological closeness of the 3D scan generated and real Cacao shells. (Photos courtesy of Nicholas Hellmuth, FLAAR Reports 3D research programs. http://www.maya-ethnobotany.org.)

FIGURE 11.5Figure showing the morphological closeness of the 3D scan generated and real Papaya fruit. (Photos courtesy of Nicholas Hellmuth, FLAAR Reports 3D research programs. http://www.maya-ethnobotany.org.)

Similarly, FLAAR staff use the same 3D scanning for papaya. McGrath (2011) in collaboration with the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), developed the paper work book with inexpensive Augmented Reality, to create a “magic book” effect through which the plants can be seen to “pop up” in three dimensions off the page. Augmented Reality (AR) is a technology that allows content creators to merge two media for the purpose of an enhanced reading experience: traditional printed material and 3D computer graphics. The physical book’s location and orientation are tracked by a low cost camera, such as a webcam or the camera of a cell phone, so the graphics move as the physical object is manipulated.

For the ethnobotanical work book, Rober McGrath created 3D renditions of the 15 plant species in the book, along with a software application that recognize 15 unique markers, which displays one of the plants floating atop each marker. These markers can be printed out (e.g., on sticky paper), and affixed to the appropriate pages of the workbook. The workbook will look almost the same with the addition of the markers, and can be used just as before. But with AR application and an inexpensive web camera, the plants will pop off the page in 3D on the computer screen. The software package will be available for inexpensive computers that can be used in a classroom, nature center or at home.

11.11QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH IN ETHNOBOTANY

The concept of quantitative ethnobotany is relatively new and the term itself was coined only in 1987 by Prance and coworkers (Prance, 1991).

Quantitative ethnobotany may be defined as “the application of quantitative techniques to the direct analysis of contemporary plant use data”. Quantification and associated hypothesis-testing help to generate quality information, which in turn contributes substantially to resource conservation and development. Further, the application of quantitative techniques to data analysis necessitates refinement of methodologies for data collection.

Quantitative research is often contrasted with qualitative research, which is the examination, analysis and interpretation of observations for the purpose of discovering underlying meanings and patterns of relationships, including classifications of types of phenomena and entities not involving mathematical models.

Quantitative research is generally made using scientific methods, which includes:

1.the generation of models, theories and hypotheses;

2.the development of instruments and methods for measurement;

3.experimental control and manipulation of variables;

4.collection of empirical data;

5.modeling and analysis of data.

Generally, multivariate and statistical methods aim at making large data sets mentally accessible, structures recognizable and patterns explicable, if not predictable. Johnson and Wichern give five basic applications for these methods (Johnson and Wichern, 1988):

1.Data reduction or structural simplification: The phenomenon being studied is represented as simply as possible with reduced number of dimensions but without sacrificing valuable information. This makes interpretation easier.

2.Sorting and grouping: Groups of similar objects or variables are created.

3.Examining relationships among variables: Variables are investigated for mutual interdependency. If interdependencies are found the pattern of dependency is determined.

4.Prediction: Relationships between variables are determined for predicting the values of one or more variables on the basis of observations on the other variables.

5.Testing of hypothesis: Specific statistical hypotheses formulated in terms of the parameters of multivariate populations are tested. This may be done to validate or reject assumptions.

11.12TYPES OF QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS SOFTWARES

There are many computer packages available for analysis of multivariate data sets. Some of them are discussed as follows:

11.12.1BIOMEDICAL PACKAGE (BMDP) (see, http://www.statsols.com/?pageid=6)

A statistical language and library of over forty statistical routines developed in 1961 at UCLA, Health Sciences Computing Facility under Dr.Wilford Dixon. BMDP was first implemented in Fortran for the IBM 7090. Tapes of the original source were distributed for free all over the world.

BMDP is the second iteration of the original BIMED programs. It was developed at UCLA Health Sciences Computing facility, with NIH funding. The “P” in BMDP originally stood for “parameter” but was later changed to “package”. BMDP used keyword parameters to define what was to be done rather than the fixed card format used by original BIMED programs.

BMDP supports many statistical functions like:

•simple data description,

•survival analysis,

•ANOVA,

•multivariate analyzes,

•regression analysis, and

•time series analysis.

11.12.2CANOCO

Canoco is one of the most popular programs for multivariate statistical analysis using ordination methods in the field of ecology and related fields. User’s Guides of the recent Canoco versions (4.0 and 4.5) were cited more than 6900 times in the past 16 years (1999–2014, ISI Web of Knowledge).

Canoco 5 is the new, much re-worked version of the Canoco software, released in October 2012. This site offers one access to additional resources for the effective use of the software, as well as a brief overview of Canoco 5 new features. Use the menu at the right side of this page to access these resources. (see, http://www.wageningenur.nl/en/Expertise-Services/Research-Institutes/plant-research-international/show/Canoco-for-visualization-of-multivariate-data.htm).

In Canoco 5, data import, analyzes and making graphs are integrated in a single Canoco 5 project. The Canoco Adviser helps in choosing data transformations and methods of analysis. Numerical analyzes that used to take many runs, are now available through a single analysis template and the Analysis Notebook concisely summarizes the results and allows access to the full results. All analyzes done on a set of data tables are now collected within Canoco 5 projects, sharing the analytical and graphing settings. Canoco 5 helps to make even better publication-quality ordination diagrams. The manual has been largely re-written and the large set of real-life examples is updated and extended to show new ways of working with multivariate data. (see, http://www.canoco5.com/index.php/canoco5-overview).

All statistical methods offered by Canoco for Windows 4.5 are available, such as DCCA method – including their partial variants, with Monte Carlo permutation tests for constrained ordination methods, offering appropriate permutation setup for data coming from non-trivial sampling designs

Principal coordinates of neighbor matrices (PCNM) method is available within the variation partitioning framework. Present implementation matches the suggestions described in Legendre and Legendre (2012) under an alternative method name (dbMEM).

11.12.3NTSYSpc

NTSYSpc can be used to discover pattern and structure in multivariate data. For example, one may wish to discover that a sample of data points suggests that the samples may have come from two or more distinct populations or to estimate a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining or UPGMA methods for constructing dendrograms. Of equal interest is the discovery that the variations in some subsets of variables are highly inter-correlated (clustered). The program originated as NTSYS in the 1960s but over the years is has been completely redesigned and greatly extended for use on PCs.

The input can be descriptive information about collections of objects or directly measured similarities or dissimilarities between all pairs of objects. The kinds of descriptors and objects used depend upon the applicational morphological characters, abundances of species, presence and absence of properties, etc. NTSYSpc can transform data, estimate dis/similarities among objects, and prepare summaries of the relationships using cluster analysis, ordination, and multiple factor analyzes. Many of the results can be shown both numerically and graphically. The software is designed for both classroom and research.

Version 2.2 (see: http://www.exetersoftware.com/cat/ntsyspc/ntsyspc.html) for Windows is easy to use yet still has the speed and functionality of the previous versions. There is an interactive mode and a batch mode with a simple command language (useful for analysis of simulations and multiple datasets). The program takes advantage of the Windows environment and allows long file names and the processing of large datasets. Plot options windows allows you to customize the plots (specify titles, fonts, sizes, colors, scales, line widths, background colors, margins, and many other aspects of what is plotted). There is also a print preview mode. NTS data files are ASCII files that can be shared with other programs. Long input lines are supported. A spreadsheet-like data editor is included that makes it easy to create and edit data files. It can be also used as an ASCII text editor for very large files. Matrices can be read from Excel XLS and CSV files and trees can be read from one type of nexus files. An option is provided to output to MATLAB M files.

11.12.4TWINSPAN FOR WINDOWS (see, http://www.canodraw.com/wintwins.htm)

This software, written by Mark O. Hill and Petr Smilauer (with contribution of CajoTerBraak and John Birks), is available free of charge for any non-commercial or commercial purposes and can be installed and used even if you do not have a license for Canoco for Windows. It implements divisive classification method named TWINSPAN (Two-way Indicator Species Analysis) and analyzes datasets provided in one of the data formats accepted by Canoco (Cornell condensed format, full format or free format). TWINSPAN for Windows is distributed using an independent installation program.

11.13FUTURE RELEVANCE OF CAQDA IN ETHNOBOTANY

Ethnobotanists interested in computer assistance in their work must acquaint themselves with the variety of capabilities and programs available because no one program dominates the CAQDA field.

The analytical principles of these context-dependent methods are more difficult to codify than those of grounded theory. So, while grounded theorists may find themselves able to take advantage of a wide variety of computer resources as they move from QDA to CAQDA, researchers working in other traditions may find that computer assistance limits their analyzes unless they limit the extent to which they make use of computers.

The large number of CAQDA software programs available suggests that these software packages are in a preliminary stage of computer entry into the qualitative field. With time, the computer will do for qualitative data analysis what it has done in the quantitative realm: reduce labor, regularize procedures for data gathering and analysis, and establish conventions for the reporting of results. Moreover, the diversity of program options will allow these advances to occur along parallel methodological lines so that regularizing data-handling procedures will not require homogeneous epistemological stances. On the other hand, the still infrequent mention of CAQDA in ethnobotanical writing means that the expansion of software choices has not yet influenced the course of ethnographic research. CAQDA may be a significant advance for positivist researchers, but its potential for regularizing analysis in the qualitative field has not been reached.

The computer offers three ways of facilitating qualitative analysis that may lead to, but are no guarantee of, the enthronement of a CAQDA killer app.