“They beat me and pulled out my fingernails.”

—KO KING HUN,

TESTIMONY, OCTOBER 5, 1945

AROUND EIGHT-THIRTY ON THE MORNING OF FEBRUARY 6—just two hours after MacArthur announced to the world the fall of Manila—Japanese troops under Colonel Noguchi’s command ordered all males over the age of fourteen to line up in the aisles of the Manila Cathedral. Many of the refugees who crowded the cavernous sanctuary this Tuesday morning felt exhausted after a restless night atop pews or stretched out on the stone floor. Fear and uncertainty only added to the stress. Though the Americans had reached Manila, thousands of civilian refugees in Intramuros remained prisoners of the Japanese, who had sealed the gates to the Walled City. No one knew what the enemy planned. The men queued up two abreast. Women and children watched as the troops marched an estimated one thousand males out the wooden doors with one armed guard for every ten men. The refugees were headed to the one place no one in Manila ever wanted to go: Fort Santiago.

For almost four centuries, Fort Santiago had served as Manila’s epicenter of evil. Originally constructed as a primitive palisade on the banks of the Pasig River, the twenty-acre citadel had long ago traded its palm and earthen defenses for more than two thousand feet of stone walls, towering more than twenty feet high. Over the years the triangular-shaped fortress that anchored the northwestern corner of Intramuros had grown to include a labyrinth of dungeons that had played a starring role in the Spanish Inquisition. Associated Press reporter Raymond Cronin toured the fort’s ancient cells before the war. “The ceilings and the walls dripped, since they were below the river bed,” the journalist wrote. “The clay floors were wet and slippery. From rocks in the walls hung rusty chains in which the victims of other years, manacled by neck, leg and arms, dangled without food or water until the spirit was crushed or life departed.”

Workers sealed the dungeons during America’s administration, transforming the fort into the staid offices of the Army’s Philippine Department. But the fall of Manila saw the resurrection of Fort Santiago’s frightful origins as the headquarters of the dreaded Kempeitai, a place the Japanese sent captured guerrillas and other suspected enemies of the empire. “It is alive again. Fort Santiago,” Pacita Pestaño-Jacinto wrote in her diary in March 1942. “People don’t say its name aloud. They whisper it.” Over the course of the war, the Japanese expanded the prison, packing inmates, as one witness later attested, like “slaves in the Spanish galleons.” The Japanese used starvation as a weapon, triggering beriberi in many of the captives and leaving others blind. “In a period of twenty-five days,” recalled Frank Bacon, an American mining engineer, “I had only two bowel movements.” Chinese prisoner Ko King Hun dropped from 118 pounds to just sixty-eight in two months in 1943. “I was so thin,” he said, “that I could form a ring around my leg by putting my thumb and index finger together.”

Starvation proved only part of the horror.

Fort Santiago served as an interrogation and torture center. Guards pummeled prisoners with everything from swords to shovels until most lost consciousness, vomited, or spat up blood. Teeth proved a common casualty. American prisoner Margaret Morgan saw interrogators beat a pregnant captive so severely that she later miscarried in her cell. Waterboarding was another frequent torture as guards tied victims down, forced a hose in their mouth, and turned on the spigot. Filipino Jose Lichauco endured three rounds. “Each time,” he recalled, “I lost consciousness.” If the fear of drowning failed to make captives talk, interrogators resorted to electricity, forcing victims to sit on an electrically wired chair in a basin filled with water. “The shock would be so terrific,” remembered Filipino Generoso Provido, “that the victims would shout like mad men and plead to be killed.” Chinese merchant Jose Syyonping personally experienced that agony. “I felt so bad,” he later testified, “that I urinated and I was forced to defecate.”

Interrogators grew increasingly cruel and creative as the war progressed. “I was given the nail treatment,” recalled Swedish prisoner Erik Friman. “This consisted of hammering slivers of bamboo under the finger nails until the nails pulled up at the root so they could be pulled out with dirty pliers.” Other tortures were sexually sadistic. The Japanese burned testicles and jammed matchsticks into men’s penises and cigarettes into women’s vaginas. Interrogators hung a Chinese prisoner upside down then ran a wire deep into his body via his anus. “When they put him down,” one witness recalled, “he was already dead.” The Japanese at times even tortured the wives of suspected guerrillas, forcing their husbands to watch. Provido recalled one such occasion when guards stripped the spouse of a captive naked, burned off her pubic hair, and probed her with a large stick until she begged her husband to admit guilt. “This was the most revolting torture imaginable,” Provido said. “It made me sick in mind and body.”

The Japanese liked to show prisoners the bodies of murdered captives to frighten them into cooperating, including Filipino Ladislao Joya, who was forced to view two headless corpses. “I saw men with intestines taken out while living,” he later testified. Interrogators went so far as to force prisoners to hurt other captives. That was the case for American Richard Beck, to whom the Japanese handed a baseball bat and demanded he strike an elderly Filipino prisoner. Beck’s half-hearted swing prompted the investigator to demand he either hit harder or be shot. “After that,” Beck said, “I beat the old man.” One of the worst such atrocities happened to Joya, whom guards marched outside with other prisoners. Guards made two of the prisoners kneel before fresh graves. An officer handed Joya a sabre and ordered him to decapitate them. One of the men began to cry. Joya felt he had no choice but obey if he wanted to live. He raised the sword and swung it at the first man, hitting him just below the neck but failing to decapitate him.

“Come on,” the officer barked.

And again.

“It took me two strikes to behead each victim,” Joya would later tell war crimes officials. “After beheading, my investigator took the sabre from me and wiped the blood off by drawing the sabre over the shoulder of my coat.” The Japanese then ordered Joya to lower the bodies into the graves and go retrieve the heads, which had rolled off to the side. “It was horrible,” Joya recalled, “to see the head.”

The American airstrikes on Manila in late 1944—foreshadowing America’s return to the Philippines—prompted Fort Santiago to evolve from a torture center into a slaughterhouse. The work of disposing of the bodies was so intense that gravediggers at the North Cemetery labored one day in December 1944 without breaks from eight a.m. until ten p.m., burying truckloads of the dead. Santiago Nadonga estimated that he helped bury seven hundred people that day, many covered in cuts and bruises. “Some of them had wires around their necks and their hands tied behind their backs,” Nadonga recalled of the corpses. “Their bones stuck out very prominent, as if they had been starved.”

The men who marched out of the Manila Cathedral this February 6, one after the other as wives and children watched, would share a similar fate. “Don’t worry,” one of guards assured the spouses, “men will come back in three days.”

Few believed him.

Thirty-one-year-old Rosa Calalang saw her husband Jesus march north. He suddenly broke out of line and ran back, embracing her and the couple’s children one last time. He slipped her his wallet with his picture. “We watched them as they filed away,” she would later testify. “That was the last I’ve seen of him.”

MACARTHUR’S STAFF CAR SLOWED to a stop at the Balintawak Monument on the northern edge of Manila on the morning of February 7. The general had finally returned to the Philippine capital, four days after American troops first entered the city. Dressed in a khaki uniform, hat, and Ray Bans, MacArthur was accompanied by General Fellers and colonels Lloyd Lehrbas, Roger Egeberg, and Andres Soriano. A circle of generals awaited him this morning at the monument, including XIV Corps commander Oscar Griswold, Robert Beightler of the Thirty-Seventh Infantry Division, the First Cavalry’s Verne Mudge, and William Chase, who had led the flying columns into the city. Chase couldn’t help but sense that Griswold and Beightler felt sour this morning that he had beat them into Manila, a fact likely exacerbated when MacArthur exited his staff car and strode straight over to Chase, placing his hands on his shoulders.

“Chase,” MacArthur began. “Well done! I have recommended you for promotion to Major General and have ordered you over to take command of the 38th Infantry Division which is bogged down in the Zig-Zag Pass east of Subic Bay.”

Chase had a present of his own for MacArthur. On the first night in Manila, Chase’s aide, Capt. Henry Freidinger—known simply as Friday—had found a pristine black limousine. Chase had instructed Friday to drive the car over this morning, where he presented it to MacArthur. The general was stunned. “This is my old car,” MacArthur declared. “Thank you! I am glad to have it back again.” So excited was MacArthur that he noted the car’s return in his diary: “Retrieved own Cadillac automobile left on Corregidor and since driven by Jap commanding officer in Manila.”

MacArthur was eager to visit the liberated internees and prisoners of war. He loaded up in a caravan and stopped first at Bilibid Prison. The army had moved the internees, who were initially evacuated because of the threat of fire, back into the prison after the conflagration spared Bilibid, which was better set up to care for the nearly thirteen hundred men, women, and children.

Senior medical officer Maj. Warren Wilson greeted the general and his aides. Roger Egeberg, MacArthur’s physician, thought Wilson was the thinnest man he had ever seen who was not bedridden. The former prisoner stood erect and saluted.

“Welcome to Bilibid, sir,” Wilson said, his voice hoarse.

“I am glad to be back,” MacArthur said, grabbing his hand.

The general entered the wards to find many of the men atop cots. “Some eyes remained vacant, others smiled, many wept, and the sitting tried to stand—many couldn’t,” Egeberg recalled. “Those lying tried to sit up, and most failed.”

MacArthur could not escape the fact that these were some of the same men he had left behind 1,064 days earlier when he climbed into the torpedo boat and fled Corregidor; the robust and healthy young soldiers were now hollowed out by years of starvation. One of the veterans would later tell Associated Press reporter James Halsema, who recorded the conversation in his private diary, that before his capture he had watched several soldiers on the march down from Topside leap from Corregidor’s cliffs, preferring death to prison. “If I’d known then what I know now,” the soldier said, “I would’ve jumped too.”

Those who were well enough climbed to their feet and stood at attention alongside their cots. “They remained silent, as though at inspection,” MacArthur later wrote. “I looked down the lines of men bearded and soiled, with hair that often reached below their shoulders, with ripped and soiled shirts and trousers, with toes sticking out of such shoes as remained, with suffering and torture written on their gaunt faces. Here was all that was left of my men of Bataan and Corregidor. The only sound was the occasional sniffle of a grown man who could not fight back the tears.”

The general shook hands with some and touched the shoulders of others.

“I never thought I’d see you, sir,” one dark-haired young American said.

“Dear God,” another said between sobs. “Dear God.”

“You’re back,” others whispered. “You made it.”

“I’m long overdue,” MacArthur repeated, his voice gravelly from emotion. “I’m long overdue.”

The general wandered from ward to ward, where Egeberg heard him mumbling. “My boys, my men—it’s been so long—so long.”

An officer who had fought on Bataan approached the general, dressed only in a torn undershirt and filthy long underwear.

“Awfully glad to see you, sir,” he said. “Sorry I’m so unpresentable.”

“Major,” MacArthur said, shaking his hand, “you never looked so good to me.”

Not all the former prisoners remembered the general’s visit so kindly. For some, both at Bilibid and Santo Tomas, the anger over his escape from Corregidor years earlier still burned, a sentiment Elizabeth Vaughn confided in her diary. “To those in the P.I.,” she wrote, “there is nothing glorious about MacArthur except the brass of his uniform.”

The general struggled over the horrible condition of his troops. “I will never know how the 800 prisoners there survived for three long years,” he later wrote. “The men who greeted me were scarcely more than skeletons.” The affect it had on MacArthur was obvious to those around him. “The general walked up and down through the prison wards with tears in his eyes,” Chase recalled. “I have never seen him so moved.”

Internees on the civilian side had fared little better. Malnutrition had left Natalie Crouter exhausted and mentally strained, unable to comprehend the excitement MacArthur’s visit sparked in others. She looked up at one point to find MacArthur standing in front of her bunk. “He grabbed my hand and shook it, over and over, up and down,” she wrote in her diary. “I was utterly dumb. I felt and looked more miserable and wretched every second. I could not say a word and just looked back at him speechless as we pumped our arms up and down, up and down. All of the last three years was in my mind and face, and at this actual, concrete moment of release, this biggest moment of my life, I felt no joy or relief, only deep sadness which could not come into words.”

MacArthur did not say anything either but simply shook Crouter’s hand before moving on down the line. “He must have sensed that no active spark of any kind existed in me,” she concluded. “The lights had almost gone out.”

Another woman with tears in her eyes held up her son so MacArthur could touch him. “Hello, sonny,” he said. “I’ve got a boy at home just your size.”

After his brief tour, MacArthur prepared to leave. “Arrangements are being made for food, hospitalization, and whatever else these men need?” he asked.

“Yes sir,” Wilson replied. “Medical care and food are on the way.”

“Good—you have done well through these years. Goodbye, and thank you.”

MacArthur and his aides departed, pausing for a final survey of Bilibid. “I passed on out of the barracks compound and looked around at the debris that was no longer important to those inside; the tin cans they had eaten from; the dirty old bottles they had drunk from,” he wrote. “It made me ill just to look at them.”

The general climbed into his car, confiding in Egeberg that the brief visit to Bilibid had emotionally exhausted him. The car pulled away and headed toward Santo Tomas, taking alleys to avoid fighting in front of Far Eastern University. The fires north of the river had largely died down, but homeless residents wandered about the flame-blackened streets, calling out to American troops: “Burn Tokyo!”

Conditions at Santo Tomas had improved in the four days since American forces first arrived. Barely twenty-four hours earlier, a convoy of fifteen trucks and nine trailers with the 893rd Medical Clearing Company tore through the front gates of the camp. The company’s thirteen officers and ninety-eight enlisted men, who had dodged fires and mines in the dash to reach Santo Tomas, had immediately relieved the camp’s exhausted medical personnel. The starved and lousy prisoners rescued at Cabanatuan had spurred medics to ramp up the company’s supply of vitamins, calcium, and vermifuges. “Every available vitamin tablet and ampoule was procured,” recalled Maj. Frederick Martin. The staff had since toiled to convert the first floor of the Education Building into a 287-bed temporary hospital. “The litter and rubble strewn lobby and corridors of the building were eloquent evidence of the recent fighting that had taken place there,” the company’s report noted. “Many hours and much hard labor were expended clearing up the mess but by noon we had the main floor cleared and were set up and had already passed 97 patients through Admission.”

The medical company’s doctors noted the rough shape of many of the internees, even after several days of improved food. Many suffered from edema in the lower extremities while foot and wrist drop plagued others. Few of the women had menstruated in months, and many of the internees struggled with frequent or uncontrollable urination. Some suffered rises and falls in body weight of as much as eight pounds in twenty-four hours, suggesting problems with water metabolism. “These pathetic people were gaunt, pallid, suffered from breathlessness and weakness, pains in the extremities and swollen bellies and ankles,” the company’s report noted. “These cases of severe nutritional deficiency were what we took care of the first few days but in spite of endeavors six or eight of the more serious ones died in half that number of days.” On top of the internees, civilian battle casualties flooded the hospital. “The surgical theater,” the report noted, “was in use day and nite almost without interruption for the first week.”

In addition to medical care, troops worked to clear the camp, hauling away twenty-six 2.5-ton truckloads of garbage and debris from around the Education Building during the first three days. Others carried well water to help make the existing toilets flush and brought in box latrines. The clearing company likewise cooked food, serving 320 meals that first night. Even though it was designed to feed just the hospital, Red Cross workers, journalists, and others showed up for a bite, all handled by just eight kitchen workers. “For the first week our mere clearing company kitchen served an average of 1800 meals a day,” the report noted. “The internees, starved for so long, had ravenous appetites and would get into the mess line for seconds and thirds and more if we would let them. Indigestion and diarrheas became rampant but the starvelings continued gorging themselves reinforcing their diet with soda, bismuth and paregoric.”

Word had spread throughout Santo Tomas that MacArthur would visit. Even the Japanese shelling that morning, which hit the camp gardens, shanty area, and Education Building, failed to dampen the excitement. Internees crowded around the windows for a view, while others tried to secure a spot out on the main plaza.

The general’s staff car pulled up in front of Santo Tomas at ten a.m. MacArthur stepped out and saluted the honor guard before facing the flag-draped balcony.

“There’s MacArthur,” internees shouted. “He’s back.”

Reporter Frank Robertson captured the scene. “People ran from all directions as they caught sight of his famous gold-embroidered cap and the glistening five stars on his collar,” he wrote. “With joyous eagerness they pressed close, to shake his hands or just to touch him, almost with reverence.” Walter Simmons with the Chicago Tribune marveled at the excitement. “He received a riotous demonstration—one girl even kissed him.”

The general made his way into the lobby of the Main Building, mobbed by old friends so emaciated he struggled to recognize them. “At nearly every step MacArthur was halted while internees reintroduced themselves and told him they knew he would come back,” wrote Associated Press reporter Russell Brines. “Several women grasped the general’s hand and reminded him of the former social days in Manila.”

One of those MacArthur encountered was Margaret Seals, whom General Fellers had run into days earlier on his visit. “Oh, General, I’m so glad to see you and your troops,” Seals declared. “You and they were magnificent.”

“I’m glad to be here,” MacArthur replied. “I’m a little late, but we finally came.”

The general embraced her frail and emaciated body.

“Well, Margaret, you look fine,” he said. “A little thin—but fine.”

Seals was far from fine—she would die three months later in Walter Reed Hospital, just one week after her return to the United States.

MacArthur saw Eda Knowlting of Pennsylvania, who kissed him on the cheek. “General,” she cried, “we can’t tell you how glad we are to see you.”

“Mrs. Knowlting, I can’t tell you how glad I am to be here,” the general replied. “I wish I could have made it sooner.”

Another internee begged for his autograph, but MacArthur demurred. “I would have to sign hundreds,” he told the woman. “Please send your paper to me at my headquarters and I’ll see that it is returned to you with my signature.”

Eleven-year-old Robin Prising, never one to miss out, elbowed his way up close to watch. So, too, did camp historian Hartendorp, who took pride in the fact that MacArthur remembered him. “In the lobby of the Main Building,” Hartendorp later wrote, “surrounded by a press of wildly cheering people, he caught sight of me, called me by name, grasped my hand, and said he was glad to see me.”

The internees pressed in tighter. A woman dressed in rags passed her son over the heads of others so MacArthur might hold him. The general grasped the boy, stunned to see how starvation had left a vacant look in his eyes. Another internee buried his face in MacArthur’s chest and cried. Others, in contrast, laughed uncontrollably. “In their ragged, filthy clothes, with tears streaming down their faces they seemed to be using their last strength to fight their way close enough to grasp my hand,” MacArthur later wrote. “I was grabbed by the jacket. I was kissed. I was hugged. It was a wonderful and never-to-be-forgotten moment—to be a life-saver, not a life-taker.”

The general made his way to the foot of the main staircase. His aides hoped to usher him into the nearby broadcasting room so he could give a brief speech to the camp, but the throngs of internees blocked his passage. MacArthur instead cut through the library and out a side door. From there he reentered the rear of the building, but the crowed continued to follow him. He managed to make it up a rear staircase to the quarters of the army nurses from Bataan. There he nearly collided with Edith Shacklette, who described the scene in her diary. “I ran out in my robe nude as a jaybird,” the nurse wrote. “I up & kissed the general (hadn’t combed my hair or washed my teeth as water is off). Photographers flocked around me! Oh gosh. Always was impulsive.”

MacArthur then returned to the main stairs, where the internees down below in the lobby again erupted in applause. “His five stars were quite in evidence,” Margaret Bayer wrote in her diary. “He was given a good ovation. People are beginning to realize he is a great man—it was hard to see the forest and not the trees for a time.”

MacArthur was overwhelmed by the experience, a sentiment he described in a personal letter he wrote later that day. “My visit with those mistreated, starving comrades was something I shall never forget,” he wrote. “It touched me deeply.” Griswold noted in his diary afterward the obvious impact the visit made on MacArthur. “He was much affected by pitiful sights and utter thankfulness of our starved people at Santo Tomas and Bilibid who were literally being starved to death by the despicable Japs.”

The general confided in Egeberg that he was ready to leave. “This has been a bit too emotional for me,” he told his doctor. “I want to get out and I want to go forward until I am stopped by fire—and I don’t mean sniper fire.”

MacArthur’s aides ushered him back to the camp’s gates, but before he left, he slipped seven-year-old Elaine Solomon of California a chocolate bar.

“Chase,” the general said as his staff car drove through the university’s gates, “I want to go to Malacañan Palace and see your troops in the front lines.”

Several of MacArthur’s senior officers immediately attempted to talk him out of it, arguing that enemy troops and snipers still populated the streets.

General Chase sat in silence through the debate. When it ended, MacArthur addressed him again directly. “Chase, you will take me down, I am sure.”

“Yes Sir,” Chase replied. “Let’s go.”

Gunfire rattled in the distance, and smoke from the many fires hung on the horizon. Egeberg stared out the window. “Turning a corner on a broad street,” he wrote, “we encountered a stationary open truck full of Japanese soldiers—some with guns in their hands standing up leaning over the sides, others sitting, all dead.”

The convoy rolled through the front gate of the presidential palace, a colonial Spanish mansion constructed two centuries earlier as the summer home of a wealthy merchant. Over the years the two-story white palace, where MacArthur’s father had lived when he served as governor general, had grown to include a social hall, chapel, and gardens. Chase had radioed ahead, and the troops were lined up. MacArthur complimented them before he strode through the front door, welcomed by former servants whom he remembered from his days as field marshal of the Philippine Army. MacArthur embraced several and asked for a tour. Soriano, Chase, and the brigadier general’s aide Friday—armed with a machine gun—accompanied MacArthur as he explored the lower floor, surprised to find it empty and in decent shape. The group climbed the stairs to former president Manuel Quezon’s office. “Here he stopped, took off his hat, and lowered his head in what must have been a silent prayer,” Chase recalled. “He then said that he had worked for several years in close association with the late president and wished to be alone in the room for a while. We left in respect of his wishes.”

MacArthur had shared a long history with Quezon, who had invited him to the Philippines to help build the nation’s army and later served as the godfather of his son, Arthur. Quezon had evacuated Manila for Corregidor on Christmas Eve 1941, spending eight weeks on the Rock with MacArthur before slipping out one night on the submarine Swordfish. MacArthur had embraced Quezon the evening he left.

“Manuel, you will see it through,” MacArthur had told his friend. “You are the Father of your Country and God will preserve you.”

At that time, before Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to evacuate Corregidor, the general had planned to stay on the Rock and fight to the end. Quezon understood, removing his signet ring and slipping it on MacArthur’s finger. “When they find your body,” he told him, “I want them to know you fought for my country.”

Quezon had spent the war in exile, his goal always to return to home. But the Philippine president’s long battle with tuberculosis had ended just six months earlier when he died in a Saranac Lake hospital in upstate New York. Until his death he had tracked MacArthur’s progress back to the Philippines. “Aurora,” Quezon had cried out to his wife moments before he died, “he is only 300 miles away!”

MacArthur emerged from Quezon’s office a few moments later and walked out onto a porch that overlooked the Pasig. Chase grew nervous, as the river served as the front line. With the bridges destroyed, American troops had yet to cross but would do so later that afternoon. At this moment, MacArthur was barely a mile and a half from his old home atop the Manila Hotel, the house he had vacated in such a hurry three years earlier that his family did not have time to even take down the Christmas tree.

The general’s eyes gazed south across the river, where tangles of green lily pads floated upon the muddy waters bound for the bay. Across the river he could see the palace gardens, and to the west, like giant chess pieces, sat the General Post Office, City Hall, and the Legislature, Finance, and Agricultural buildings—the grand public structures that had long symbolized America’s influence in the Philippine capital. Even as MacArthur soaked up the view, Japanese marines rushed to fortify those buildings, all part of Admiral Iwabuchi’s plan to turn Manila into an urban quagmire. MacArthur at this very moment stood on the sidelines of a coming fight that the Thirty-Seventh Infantry’s report would later call “the bitterest and bloodiest battle that Jap fanaticism could conjure.”

Yet at this moment MacArthur failed to grasp the magnitude of the battle ahead, even though he had seen first-hand the city’s destroyed northern districts. As Beightler remembered, MacArthur said that it was so quiet that the XIV Corps could jump the river and seize the rest of the Philippine capital with just a single platoon. Griswold recalled the same. “He seemed to think the enemy had little force here,” he wrote in his diary. “Was quite impatient that more rapid progress was not being made.”

An American mortar platoon a block down the street opened fire on the Japanese positions south of the river, interrupting MacArthur’s solemn moment.

“I want to visit your front line platoons in action,” he told Chase.

Chase agreed, and the men departed the palace. Word had spread throughout the neighborhoods that MacArthur was in Manila, and local men, women and children, cheering and waving flags, now crowded the sidewalks and streets.

“Viva MacArthur!” many shouted.

The general soaked it up. “Obviously much pleased and entirely oblivious to the always present danger,” Chase observed, “he walked down the middle of the street.” Adjacent to the presidential palace stood the San Miguel Pale Pilsen Brewery, owned by Col. Andres Soriano. At Chase and Soriano’s urging, MacArthur visited the brewery at eleven a.m. This would be the last stop on his visit to Manila this morning. Chase was particularly parched and wanted a cold drink. “My tongue was hanging out a foot,” he recalled. “The general drank a bottle and I drank a large pitcher.”

SECOND LT. JOHN HANLEY reached the Dy Pac Lumberyard at about the same time MacArthur downed his bottle of beer with General Chase. The night before, American intelligence had received reports of a possible massacre of civilians at the site. Hanley’s job that morning was to investigate. The seasoned infantrymen had grown accustomed to violence on the battlefield. But there amid the towering weeds, the troops found that the dead did not wear camouflage fatigues but rather flower-print dresses, nightgowns, and even infant sleep suits. Of the more than one hundred men, women, and children brought to the site in the middle of the night on February 3–4, only four are known to have survived, including Ricardo San Juan, who watched the Japanese kill his pregnant wife and three children. The horror the troops discovered in a field less than three miles from the presidential palace would prove only the first of dozens of atrocities that would befall the Philippine capital, a window into the days ahead as American forces fought street to street through southern Manila.

The reports of that morning filed by Hanley and his men not only captured the brutality but also made clear that the civilians had been executed.

“On the adult bodies,” Hanley noted, “the hands were tied.”

“These were the cut and mangled bodies of men, women, and children,” Sgt. Paul Smith testified in his affidavit. “They were scattered through the area, lying singly and in piles.”

“It appeared,” added Pvt. First Class Claude Higdon, Jr., “whole families had been killed.”

American troops set up a perimeter, blocking curious residents from straying too close. In reality, the soldiers were the last to arrive. Locals in the days before had already visited the lumberyard as word of the slaughter had spread. Many had come in search of relatives, who had been dragged off by the Japanese in the middle of the night. Others had wanted to recover cash and valuables from the dead. Mutilation of the bodies made identification difficult at times, including one woman found sliced open from her vagina to her chest. Tondo teenager Manuel Mendoza made the gruesome discovery of his twelve-year-old cousin Greta. “Her head,” the youth later told American war crimes investigators, “was nearly cut off and was hanging by the skin.” In other cases, the Japanese had lopped the hair off of women, leaving it in piles several meters away. “Many had wounds of the abdomen,” observed an American medical officer who visited later that day, “through which the intestines were protruding.”

The tropical sun only further hindered identification, helping balloon the bodies as an army of flies attacked the corpses. The stench turned away all but the most determined. “I saw eight piles of dead bodies, the largest pile had about 15 bodies, another pile had about 12 bodies in it and the remaining piles had five or six bodies in them,” recalled teenager Antonio Lamotan, who came at the request of neighbor and survivor Ricardo Mendoza. “I also saw other bodies scattered in the tall weeds.”

Daniel Simon picked through the tangle of bodies, searching for the valuables of the slain family members of Faustino Fajardo, his godfather. He removed the gold earrings, bracelet, and ring from Fajardo’s wife, Lourdes, still dressed in the nightgown she wore when the Japanese seized her. From nine-year-old Florencia Fajardo, he took a pair of earrings along with the engagement ring from the left third finger of twenty-eight-year-old Leonora Fajardo Pimentel, dressed in a yellow dress with red flowers. Amid the dead Simon spotted two-month-old Celia Fajardo, still swaddled in a flannel baby suit. He struggled with four-year-old Melita Fajardo’s earrings. “It was fastened through,” he recalled, “and when I took it part of the flesh went with the earrings.”

As decomposition disfigured the dead, residents looked for telltale ways to identify loved ones. Manuel Mendoza recognized his friend Manuel Calinog from his blue sharkskin polo shirt and long gray pants. He confirmed Calinog’s identify when he fished his Japanese-issued residence certificate from his right pants pocket. Several noted the “FFF” monogram on the left pant leg of Faustino Fajardo. Others recognized Agapita Mendoza from her employer’s name on her apron, Dalisay Theater. “Her neck,” recalled friend Benjamin Chome, “was half cut.” Other witnesses identified thirty-five-year-old Antonio Dominador—the twentieth man in line that night next to San Juan—from his amputated right hand. Dominador’s twenty-five-year-old wife Cecilia, even in death, still clung to the couple’s slain nine-month-old baby, Arturo.

Maj. David Binkley, the Thirty-Seventh Infantry Division’s sanitary inspector, arrived at the lumberyard on the afternoon of February 7. In a city without running water and sewer, public health was a major concern—and dead bodies served as insect breeding grounds. Binkley swept the area with brothers Francisco and Mariano del Rosario, undertakers for the city of Manila. The men counted 115 bodies, including many women and children; the blood proved so voluminous that it had run off in streams. Amid the weeds, Mariano del Rosario spotted one woman whom he surmised to be seven or eight months pregnant. The inferno that swept through Tondo in the following days had burned several dozen bodies beyond recognition, but investigators would still identity fifty-one of the deceased; the other sixty-four would be buried unknown.

The undertakers arranged for trucks to haul the remains to the North Cemetery, where burial squads would use a bulldozer to dig a mass grave. The last lorry loaded with the dead rolled out of the lumberyard that evening around six. An American war crimes report would later attempt to summarize what happened at the Dy Pac Lumberyard. “Whole families were indiscriminately murdered on mere suspicion that some one member was a guerrilla,” the report concluded. “No one was too old or too young to escape attention; babies of two or three months, pregnant women, and an old woman of eighty, all suffered the same fate.”

AMERICAN INFANTRYMEN PREPARED to cross the Pasig on the afternoon of February 7. In recent days, intelligence regarding Japanese plans in Manila had begun to solidify, debunking the earlier hopes that the enemy would abandon the capital and instead confirming the guerrilla reports that had detailed preparations for an urban siege. That same day, in fact, troops found stashed in a grave in the Chinese Cemetery several charred records, including a copy of Admiral Iwabuchi’s January 21 operational orders. This intelligence windfall not only detailed the breakdown of the admiral’s North, Central, and Southern forces but also spelled out his mandate that his men hold the city at all costs, even identifying designated fortresses, like the Paco Railroad Station and Fort McKinley. “In general,” stated a First Cavalry Division intelligence report, “the defense plan appears to have projected a tenacious delaying action.” Analysts were quick to seize on a critical omission in Iwabuchi’s plan. “Neither the sketch nor the orders,” the cavalry’s report noted, “provide for an eventual withdrawal from Manila.”

This would be a fight to the death.

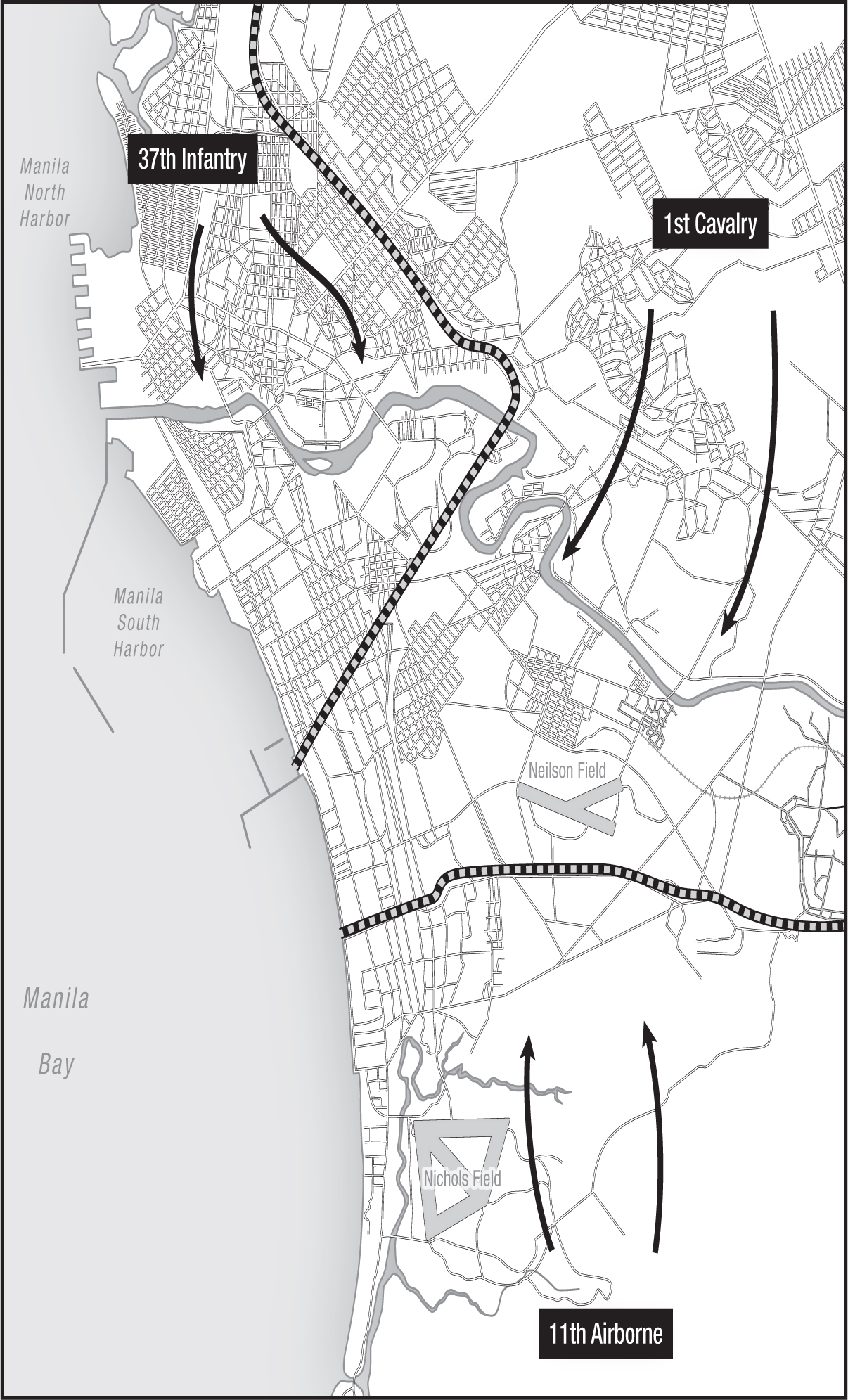

Colonel Noguchi’s forces had avoided a battle in northern Manila, instead torching the city’s commercial and financial districts before falling back across the river and blowing up the bridges. Those soldiers who made it out of the inferno prepared for a final stand in the Walled City. Iwabuchi’s marines, meanwhile, fortified the surrounding government buildings and residential areas while Capt. Takesue Furuse’s Southern Force fought to repel General Eichelberger’s Eighth Army. MacArthur’s troops would now have to cross the river and hunt down the enemy in the capital’s populous south side. To do so, American forces carved up the city. The Thirty-Seventh Infantry would cross the Pasig near Malacañan Palace and then turn west and drive toward Intramuros and the waterfront. The First Cavalry would envelop Manila from the east, crossing the river farther south before turning toward the bay, a thrust that would parallel the infantry. The Eleventh Airborne would close the city’s southern door.

With the bridges all sitting on the bottom of the river, troops would have no choice but to cross the Pasig in assault boats, a slow and perilous feat that exposed them to attack by the more than eight hundred Japanese marines deployed in that area as part of Iwabuchi’s Central Force. Plans called for the 148th Infantry to paddle across, secure the districts of Pandacan and Paco, and then drive southwest toward the Walled City and Manila Bay. The 129th Infantry would follow, hook immediately west, and seize Provisor Island, a roughly ten-acre island in the Pasig that housed a vital steam power plant. Officers had selected four departure points a few hundred yards east of Malacañan, a move that would allow them to float with the river’s current and land in the palace’s expansive gardens that ran along the river’s south bank.

War planners carved up Manila between the Thirty-Seventh Infantry Division, the First Cavalry Division, and the Eleventh Airborne. The dividing boundaries between these forces illustrate how the Americans encircled the Japanese and drove them west toward Manila Bay.

To shield the crossing locations from the enemy, infantrymen gathered that afternoon a couple blocks north of the river, awaiting the arrival of thirty assault boats and amphibious tractors, better known to the troops simply as alligators. Once the equipment arrived, platoons moved through the stacks of wooden boats, grabbing them and marching down to the Pasig to climb aboard. The first assault wave prepared to depart at three-fifteen p.m. Maj. Chuck Henne, who controlled the flow of infantrymen at the river’s bank, joined the others to watch, all anxiously waiting for the enemy guns to open fire. “Quietly,” Henne recalled, “the long line of boats pushed out beyond a jetty down stream into the main current which bent the formation into a long crescent.”

Five minutes passed.

Then ten.

The infantrymen in the boats focused on the approaching riverbank, paddling amid the swift-moving brown water filled with clumps of lily pads.

The first wave hit the south bank at three-thirty p.m., just as the Japanese guns finally opened fire. The infantrymen scrambled up the bank and into the gardens. “Any idea of an unopposed landing,” said Lt. Jimmy Falls, “was forgotten.”

Henne summoned the other company commanders to instruct them how to cross. Tensions soared, as the Japanese were sure to target each subsequent wave. The major felt someone hovering over him as he studied the map on the ground. Irritated, he wheeled around to find General Krueger, commander of the Sixth Army. Henne politely asked if the general had any questions.

“No, Major,” Krueger replied. “You’re doing fine. Carry on.”

The second wave pushed out into the river’s current. No sooner had the first boats rounded the jetty than the Japanese opened fire with a mix of machine guns, mortars, and artillery. “The fire slashed down, blanketing the banks and churning the river to a brown froth,” Henne remembered. “It built to a crescendo and clouded the river with dense smoke through which only the flash of exploding rounds could be seen.”

The enemy machine guns and cannons proved the worst, shredding the wooden boats. “When we were hit we could only go forward,” recalled Capt. Gus Hauser. “The current in the river was shoving us that way making the far bank closer, but minutes seemed hours.” Reaching the south bank, troops poured over the sides, abandoning some of the wrecked craft to drift downriver toward the Walled City and the bay. Amphibious tractors meanwhile motored out into the water to retrieve boats for the next wave, drawing fierce enemy fire. Rounds ripped through the metal skin, leaving the wounded tractors to gasp as the air escaped, and the slain alligators sank to the muddy bottom. Henne marveled at the chaos of the combat before him. “Hollywood could not have staged the smoke, flash and bang more dramatically,” he later wrote. “It was spellbinding to watch pieces of paddles and splintered chunks of boat plywood fly through the air while men paddled with shattered oars and rifles to work their boats to the far bank, seemingly oblivious to what was happening to them.”

Over on the front lawn of Malacañan Palace, battalion surgeon Capt. Lew Mintz had set up his aid station to treat any casualties from the crossing when Japanese artillery suddenly rained down. “With only the rush of shells to warn us, the area around us erupted with high explosives,” he said. “Many of the men were caught in the open and hit. By actual count eighteen men were on the ground requiring attention.”

In the regimental headquarters inside the palace, Maj. Stanley Frankel worked with his assistant, Sayre Shulter, preparing orders for an assault the next day when the artillery blasted the lawn.

Moments later a soldier appeared at the door. “Lots of guys have been hit by Japanese shelling in the courtyard,” he announced. “We need litter bearers to get them back to the aid station.”

Shulter, a fastidious secretary who had spent much of the war shackled to his typewriter, darted outside with his boss reluctantly in tow. The shelling stopped, allowing the soldiers to retrieve the wounded. But the lull proved short-lived and the Japanese attacks resumed, one of which knocked Shulter to the ground. “I’m hit,” he hollered.

Frankel charged over and pulled him to his feet. A quick inspection revealed no bleeding or obvious wounds. Frankel asked if he could walk.

“I can run,” Shulter assured him.

The two trotted over to the aid station, where to Frankel’s shock Shulter collapsed face down. The doctor grabbed him and rolled him over to check his pulse.

Frankel stared.

“This man is dead,” the doctor announced.

“He can’t be,” the major cried.

The doctor turned back to Shulter. He opened his eyes and checked the pulse on both his wrist and neck. “Dead, dead, dead,” he confirmed.

Frankel would later learn that the concussion blast felled him, adding the gentle secretary Sayre Shulter to the list of fourteen dead and 101 wounded that day. “He was,” Frankel later lamented, “killed 200 yards from his typewriter.”

THE JAPANESE BEGAN SHELLING Santo Tomas again soon after MacArthur’s departure that Wednesday morning. Many of the internees proved slow to grasp the danger; a few even hunted for pieces of shrapnel to keep as a souvenir.

Eva Anna Nixon was in her room when a fragment hit the window. “Look,” one of her roommates said. “Our window has a shrapnel wound.”

Many of the internees migrated into the building corridors for protection. “While we sat in the hall exchanging stories that afternoon, there was a buzz over our heads, a loud crash, and then cement, glass, and dirt came tumbling down around us,” Nixon wrote in her diary. “We ducked our heads and huddled close together. As soon as the dust settled, we looked out the window into the patio where water was pouring from the roof tanks through a shell hole over cracked and crumbled stones.”

Evelyn Witthoff charged downstairs.

“Did you hear that?” she asked. “It buzzed right over our heads up there, and you should have seen us hit the floor! No siesta for me!”

“I don’t have any shrapnel to take home, and I’m going to see if I can find some,” one of the women announced. “There ought to be some around after that blast.”

Another shell hit and exploded.

“Stay away from the windows,” an American soldier shouted. “Get back against the wall and stay low. Don’t go back into your rooms.”

The women obeyed as the Japanese shellfire worsened. “We huddled against the wall and silently clung to each other. Another blast shook the building, and everything became hazy and dark. We covered our faces and braced ourselves,” Nixon wrote. “A nurse, the color drained from her face, ran down the hall followed by two soldiers carrying a stretcher bearing two children dripping blood.”

The reality of the attack now dawned on them.

“We huddled together like hunted animals, realizing that the next moment might bring death,” Nixon wrote. “I was too stunned to pray.”

Instead an old hymn came to mind:

Our God, our Help in ages past,

Our Hope for years to come,

Be Thou our Guide while life shall last,

And our eternal Home!

Internee Margaret Bayer suffered a similar experience that morning. She had stopped off in the lobby to retrieve message blanks while her sister Helen continued on upstairs at the moment one artillery attack began. “Immediately the first shell was followed by another in the plaza just outside the door where I was standing. I bit the dust under a table!” Bayer wrote in her diary. “Then they kept hitting and hitting. I could not get upstairs and Helen could not get down.” Bayer grew frantic, picturing her sister trapped upstairs on her bed with shattered glass raining down on her. “Stretchers began coming down stairs bearing the most gruesome and bloody sights. No one looked like her!” she wrote. “Bodies were brought in from the front plaza and I hope I never see anything so awful. I finally raced for the stairs in a lull and to the second floor. Helen was there watching the stairs just as terrified and worried as I.”

The experience traumatized Bayer. “The stairs and halls had lots of HOT shrapnel on the floor,” she concluded, “but I was no longer interested in getting a souvenir.”

The late morning attacks delayed the noon meal more than an hour. During a reprieve, the kitchen staff scrambled to prepare a lunch of bully beef and string beans, part of a posted menu that simply read: “Hot American chow—plenty for everybody.” The break did not last as the Japanese began shelling the camp again in the afternoon, scoring several direct hits between three and four p.m. on the Main Building. At one point during that interval, troops recorded two bursts every three minutes.

One shell hit in Room 3 on the southwest corner of the Main Building’s first floor. Teenager Terry Meyers was holding hands with fifteen-year-old Marjorie Ann Davis when the shell exploded. Disoriented, she crawled out of the destroyed room and ran into Paul Davis, who begged to know where his sister was.

“She should be right behind me,” Meyers replied.

But she was not. Davis had been killed instantly. “I was holding her hand when one of the shells exploded,” Meyers recalled. “I was just lucky.”

“You’re hit,” someone told Meyers.

The teen looked down and saw blood coming out of her knee where shrapnel had torn into her leg. “I remember I was throwing up,” she said. “All over myself.”

Seconds before the shell hit Room 3, Mary Foley had ducked inside to retrieve some of her belongings accompanied by her husband, the Reverend Dr. Walter Foley, who before the war had served as pastor of Manila’s Union Church. He had continued his work inside Santo Tomas, chairing the internee religious committee while his wife was known as one of the best singers in the camp. The two were well liked among the camp’s medical department for volunteering to help. The explosion that afternoon killed the reverend and ripped the left arm off of his wife just below the shoulder.

Nurse Sally Blaine had heard about Dr. Foley’s death when she reached the emergency room that afternoon. “There was a woman on a stretcher whose left arm was off,” she remembered. “I didn’t want to recognize her.” Blaine approached her friend, but words suddenly failed her. “I was going to ask her could I do anything for her,” she recalled. “I looked at her, I saw the arm was off, and I couldn’t speak.”

“Sally, you know me, I’m Mrs. Foley.”

“Of course, I know you,” Blaine replied, regaining her composure.

“Where’s Frances Helen?” she asked, inquiring about the couple’s twenty-year-old daughter.

“She’s over there,” Blaine replied.

“Could I speak to her?”

Blaine had not yet talked to the Foley’s daughter and did not know if she was aware that her father had been killed.

The daughter came over. “How is daddy?” Mary Foley asked.

“Daddy is all right, don’t you worry about daddy one minute, he is all right now,” she assured her mother. “You just think about yourself and take care of yourself.”

Frances Helen walked back over to Blaine, who estimated that she could not weigh more than ninety pounds. “Do you really know about your father?”

“Yes, I know,” the daughter replied. “I know he’s dead, but I didn’t want mother to know it yet.”

“I nearly died,” Blaine recalled years later. “Oh God. The things that these little girls had to endure.”

Another time that day, Blaine encountered her best friend, who was screaming. “Jane, Jane,” she called out. “Get a hold of yourself. What’s wrong?”

Between her sobs and shouts, Blaine learned that her friend had been walking with two others when a shell hit one of the women in the chest. “Jane was wild, hysterical and I tried to calm her down. I couldn’t,” Blaine recalled. “So I slapped her on each side of the face as hard as I could slap and then she stopped crying.”

Frederick Stevens witnessed a similar scene after a shell hit Room 19.

“Where is she, where is she?” cried an older gentleman, stumbling over the debris in search of his wife.

Stevens knew what the panicked husband refused to accept; that she was gone. “He saw a high-explosive shell hit against human flesh and then dust, debris mixed with human arms, legs and bodies that were twisted and torn under. Where there were men and women, living and breathing, now only blood, bones, quivering flesh.”

“Oh Lord,” he cried. “Not my loved one, no, Oh Lord, not her.”

A soldier seized the distraught gentleman and pulled him out of the room. “He came back as a stretcher-bearer,” Stevens noted, “still looking, still hoping.”

The afternoon shelling ended only to resume again around seven-thirty p.m. One round tore into the gymnasium, seriously wounding an internee who would die from his injuries the following day. Another shell destroyed a men’s bathroom in the Main Building. Others continued to pound against the university’s south facades, causing concrete to rain down and filling the air with dust as internees huddled in corridors. Doctors moved 150 patients from the hospital in the bottom of the Education Building to the yard out back. “The Educational Building suffered two direct hits and two officers and five enlisted men of this company were injured,” the 893rd Medical Clearing Company’s report noted. “There were many severe casualties among the civilian internees living in the Main Building of the University. These cases were immediately brought into our surgery and from this time on the surgical service was kept busy day and night.”

The shelling prompted approximately eighty of the one hundred Filipino laborers the Civilian Affairs forces had hired to help clean the camp to vanish. Gone too were a dozen Filipino doctors. Tressa Roka gave up working in the children’s hospital to volunteer to help the injured. “Stunned and weeping relatives walked through the narrow aisles to identify their dead and wounded, while doctors and nurses tried to do their work,” she wrote in her diary that day. “I saw many of my fellow-members badly wounded. Many were dying. Moving from bed to bed in a daze, I did what I had to, and I was indifferent to the shells that whistled over the building.”

Roka paused over the bed of an internee. Despite a horrific head wound, she recognized John McFie, Jr., a prominent Manila attorney and close friend. The fifty-five-year-old McFie was born in New Mexico, where his father had served as a justice on the New Mexico Territorial Supreme Court. The younger McFie had fought in World War I at Verdun. He had met his wife Dorothy in Hawaii, where she worked as a schoolteacher. The couple later married in 1928 in the Japanese city of Kobe.

“I knew a good thing when I saw it!” she told Roka one time.

Roka had grown close to the couple over the years of internment. She fondly referred to them in her diary as the Macks and had marveled at their obvious intimacy, which was reflected in simple gestures, like holding hands. “They seemed closer than ever,” Roka wrote one day in May 1943 after chatting with the couple for an hour in the plaza. “Their devotion to each other was beautiful to see.”

Roka had watched the way starvation had hollowed them out, turning John’s hair bright white and sallowing Dorothy’s skin. Despite the couple’s failing health, the two remained forever upbeat. “They had never once lost their faith and optimism,” Roka confided in her diary less than a year earlier. “From their cheerful manner, one gathered that the American forces were just outside the gates of the camp.”

Now, just days after those forces tore down the camp’s gate, she stood over John McFie, his head bloodied after a Japanese shell caught him unawares in the first-floor bathroom of the Main Building. “His breathing was stertorous, his pulse thready, and I knew that he had only a few minutes to live. But where was Mrs. Mack?” Roka wrote. “She must see him before he died. Bitterness overwhelmed me. It was not fair, not right that he should go like this! He above all, with his optimism and faith.”

“Where’s Mrs. Mack?” Roka asked one of the doctors.

“In Catalina Hospital with beri-beri,” he replied. “Will you tell her?”

Roka’s heart sank. There was no way she could deliver this awful news to her friend. “Please don’t ask me to do that!” she begged, her voice a “frightened plea.”

The doctor sensed Roka’s distress. “All right,” he said, patting her shoulder. “I’ll do it.”

Others witnessed similar tragedies as shrapnel tore open the bodies of men, women, and even children. “There was one beautiful girl, only 17, I’ll never forget her,” remembered nurse Beatrice Chambers. “Half her face was taken off.”

Nurse Edith Shacklette, who only hours earlier had impulsively kissed MacArthur while wearing just a robe, vented her anguish in her diary. “We all worked all nite,” she wrote. “War is hell.” Roka echoed her. “This day had been a nightmare!” she added. “We were stunned and almost in a state of shock as we went about our work cleaning up the rubble and caring for the wounded and dying. What a pity! we kept thinking as we went about our duties. After surviving starvation, and then having to go like this!”

Those not working battled fear. “In bombing raids, you had time to run for shelter,” recalled Frederick Stevens. “Being under shell fire was a new and terrible experience.” That experience only further rattled the already fragile internees. “To be shelled when every internee had that feeling of exaltation of being freed, petrified the minds of all,” Stevens wrote. “They were dazed, and absolutely helpless from physical or nervous shock. The horrors they had suffered in the past faded into insignificance and were beyond comprehension. Each shell had a sound all its own.”

“Nobody is brave under shell fire, they just take it,” said one internee who had served in the army in France during World War I.

That fear only intensified as the afternoon faded to evening. “Night shelling was especially exhausting and nerve-shattering,” recalled Emily Van Sickle. “Straining ears in the darkness to catch sound rhythms of the next shell, we sometimes heard both sides fire simultaneously with a confusing irregularity of booms and swishes.”

Internees dragged mattresses into the corridors, listening as American observation planes buzzed overhead, searching out the Japanese artillery. Others retreated outside. “We spent the entire night out under the stars,” Bayer wrote in her diary. “The ground was hard and the night long and the mosquitos terrific, but with the help of some chocolate bars and crackers, we made it. We even slept a bit.”

Dawn brought a much-needed reprieve from the fear and uncertainty that had gripped many. According to figures compiled by camp historian Hartendorp, the February 7 shelling killed twenty-two people, including twelve internees, eight Filipino and Chinese workers, and two American soldiers. Shrapnel seriously injured another twenty-seven internees, eleven workers, and one soldier.

Like many others who survived, Eva Anna Nixon reflected on the random nature of who lived and who died. “I picked up a piece of a Japanese shell, still hot which fell at my feet as I talked with Dr. Walter B. Foley that morning. Could I know I would never talk with him again?” she wrote in her diary. “I stood in lunch line with the intelligent lawyer, Mr. McFie, and we had discussed the future of the Philippines and China. A few hours later he was dying with his brains blown out. When I last saw Mildred Harper get into bed and heard her laughter ring through the blackout, I didn’t know that shell fragments would put a stop forever to her merry laughter. And when Gladys Archer stopped me in the hall, I had no idea that in minutes her head would be severed from her body. And there was beautiful Veda—but they gave her blood plasma and she will live, even though her eye and ear are gone.”