As Friday morning dawned and we began feeling the effects of the past several days of round-the-clock activity, the reality that there were still three more full days of Comic-Con ahead hit us. The event sprawls, not just over space, but over time as well.

On Friday, the crowds would be fortified by a new contingent of folks driving down from LA for the day or the weekend as we headed toward the peak turnout of more than 130,000. We had a few panels we wanted to attend, but we dreaded the likelihood of spending hours in lines. My plan was to spend most of the morning walking the exhibit hall talking to artists, particularly those in the independent, small-press, and alt.comics areas. In the late afternoon, we’d be called in for our volunteer duty as the setup crew for the Eisner Awards. The award ceremony itself would take up the rest of the evening.

We drew back the blinds and looked down at the street. The San Diego trolleys, on a special schedule for the Con, were making stops every couple of minutes to disgorge another few hundred fans to feed the growing mob scene. Clouds of people drifted across Harbor Drive, which separated downtown and the trolley line from the convention center. We sipped our coffee and took turns pointing out costumes.

Downstairs, the lobby of the Marriott was teeming. Professionals and cartoonists hauling portfolios jostled with women in chain-mail bikinis and dealers pushing dollies heaped with white boxes. The check-in line was out the door, and we spied someone at the counter having a meltdown over a lost reservation. Who could blame her? This is the worst-case scenario: to be without a hotel room despite months of planning, when every room within a 50-mile radius is full or marked up to 10 times the rack rate.

We passed by the makeshift snack bar and continued down the escalator to the ground floor, taking the back way to the convention center to avoid the crowds on the street.

By the time we arrived, the exhibit hall was open and already packed. We entered through the Hall A doors, at the end of the convention center nearest the hotel, made our rendezvous plans, and headed our separate ways.

I decided to begin my day at Artists’ Alley, the warren of tables where individual cartoonists and special guests of Comic-Con set up shop to meet fans, sell their original artwork and sketches, and sign copies of their books and comics. In accordance with old-time Comic-Con tradition, Artists’ Alley tables are free. Now that real estate in the exhibit hall is at such a premium, the artists have been moved to the far edge of the room in Hall G, several hundred very crowded yards from where I found myself.

The middle of the floor, where the big Hollywood and video-game companies had set up their enormous, imposing displays, was just about impassable. It took more than half an hour, admittedly with lots of distractions and detours, to get from one end of the room to the other. The crowd thinned out considerably past aisle 4500, where the megabooths gave way to fantasy illustrators, fashion designers, dealers in original art, and purveyors of collectible books. In Artists’ Alley against the far wall, it was merely the equivalent of the busiest day at any ordinary comics convention—which is to say, practically deserted by Comic-Con standards.

I was especially interested in seeing Jordi Bernet, a legendary European artist with a bold storytelling style that harkened back to classic 1940s American comic strips like Terry and the Pirates. He rarely made the trip from Spain, and he hadn’t been to Comic-Con since the mid-1990s. There was only one other person in line at Bernet’s table, a dealer who had brought all 55 issues of Jonah Hex to get them signed, thereby increasing their value as collectibles. The dealer looked on with indifference as Bernet robotically affixed his signature to cover after cover. No words were exchanged. No cash either, as far as I could tell.

While I was waiting, I browsed through the sketches for sale, ranging from pencil roughs to fully realized inked drawings and originals of published pages, each one slightly beyond my price range. Eventually, the dealer moved on. I had a brief conversation with Bernet through his son, who translated between my English and his father’s Spanish. I believe I remarked on a great sketch in the pile of the old pulp character The Shadow, leading to a brief conversation about Frank Robbins, an inspiration of Bernet’s who had once drawn the Shadow comic book. Such are the things that fans and artists talk about at Artists’ Alley tables.

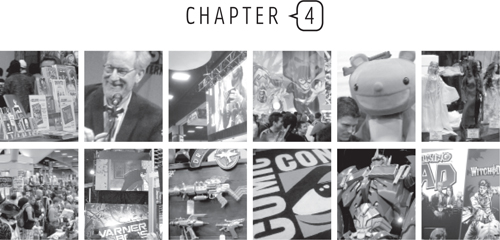

Photo by Henrik Andreasen

Artist Jordi Bernet displays a sketch for a fan at his table in Artists’ Alley.

In the next aisle, I saw British artist David Lloyd, best known for his work illustrating Alan Moore’s anarchist thriller V for Vendetta, sitting by himself trying to unload copies of an old graphic novel. As he paged through my sketchbook, he saw the last page, which had a quick drawing that Bernet had done for me while we were chatting. “Is this by Jordi Bernet?” he asked incredulously, putting the accent on the first syllable of Bernet’s last name. “Where on earth did you get that?”

I cocked my head to the left, and Lloyd noticed for the first time that Bernet was sitting not five feet over his shoulder. “Comic-Con,” he said with a sigh. No further explanation was necessary.

Less than five feet over Lloyd’s other shoulder from where these two distinguished European artists sat greeting a smattering of fans, on the other side of a wall that separated the main body of the exhibit floor (Halls A–G) from Hall H, two other masters of words and pictures were addressing a slightly larger audience.

Those two would be Peter Jackson and Steven Spielberg, kicking off the day’s program in the convention’s largest venue with an hour-long panel on their upcoming film adaptation of Europe’s most popular comic character, Tintin.

As much as I might have been interested in hearing these two gentlemen discuss their work and share some previews of the film in progress, getting into Hall H on a whim is a nonstarter. Not every event in Hall H draws Camp Breaking Dawn–magnitude fan intensity, but there is always a line, and unless you are at the very front of it, there is no guarantee that you will get in. Hall H is the 6,500-seat bedroom where the relationship between comics and Hollywood is consummated, in public, nine times a day over the long weekend. It draws a crowd.

People point to the popularity of Hall H programming as a sign that Comic-Con is not about comics anymore, but is just a big orgy of Hollywood marketing and hype. It’s certainly true that the hype is louder and the names are bigger than ever. Star power has undoubtedly played a role in Comic-Con’s off-the-charts attendance boom since the late 1990s, and it has contributed to the media-driven narrative that San Diego is the place to be for the entertainment industry.

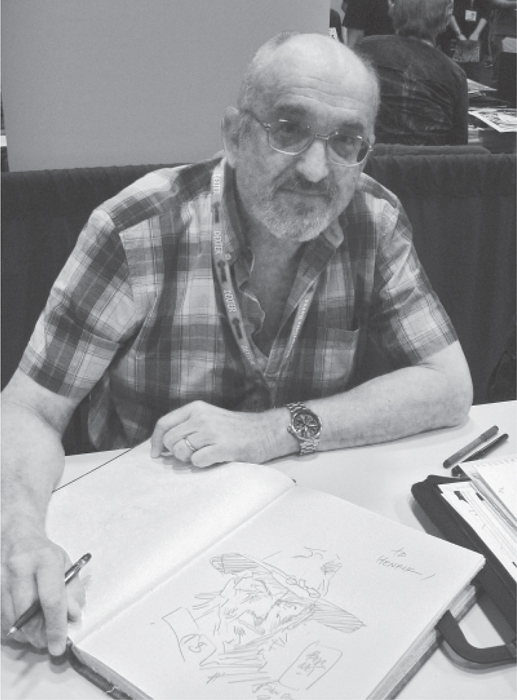

Photo by Doug Kline

Filmmaker Steven Spielberg talking TinTin with the Comic-Con faithful in Hall H.

The truth is that comics fandom has been obsessed with movies from the very earliest days. Forrest J. Ackerman, publisher of the seminal genre-film zine Famous Monsters of Filmland, was a guest at the first San Diego Con in 1970 and attended regularly until his death in 2008, helping to cross-pollinate interest between comics and horror and science fiction films. Pioneering special effects director Ray Harryhausen, animator Ralph Bakshi, and B-movie king Lloyd Kaufman may be marginal figures in the film industry, but they are honored guests whenever they turn up at Comic-Con. Star Wars famously gave fans a preview at Comic-Con in 1976, and many other movies since then have followed suit.

Death Stars, ghouls, and stop-action sea monsters are all good fun, but nothing turns the crank of comics fans more than big-budget movies that faithfully and respectfully bring superheroes to life on screen. The sense of emotional investment in the popular and artistic success of these movies is hard to fathom if you have not experienced the sense of being an outsider, a nerd, or a loser because of your choice in reading matter. A great superhero film provides much more than an afternoon’s entertainment for the long-time comics fan; it validates all those hours spent indulging in a disreputable passion by showing the world that there are some amazing, entertaining, and very lucrative ideas packed into those weird little pamphlets. For fans of a certain age, it’s hard to top the experience of Christopher Reeve making you—and all your non-comics-reading friends—believe a man can fly.

Those moments of glee were few and far between in the 1970s and 1980s, when special effects technology was not quite good enough to sell the whole men-in-tights thing, screenwriters didn’t get the comics mindset very well, and filmmakers tended to treat the whole genre as a “(Zap! Bam! Pow!)” campy joke. As recently as the mid-1990s, costumed characters were considered box office poison. The Batman franchise, launched so promisingly by Tim Burton in 1989, came to a grisly end with Batman & Robin, a neutron bomb of a movie that left the idea of the superhero film intact but destroyed all life within it.

Then came the summers of 2000 and 2001, with the twin peaks of X-Men and Spider-Man: well-realized, faithfully executed comic book adaptations that worked well as movies and did boffo box office. Around this same time, a new generation that had been raised not just with comics, but with the sophisticated comics fan culture of the 1970s and 1980s, started coming to power in Hollywood studios. They did get it, and the box office receipts helped them convince their bosses that the public was ready for superheroes to go mainstream. Thus began the torrid stage of the romance between Comic-Con and Hollywood, which continues to this day.

It’s not surprising that Hollywood would turn to comics for inspiration. Comics, like film, are a visual medium, and there are decades’ worth of great material, largely unknown to the wider public, buried in those long white boxes of back issues. Comics fans have been saying for years that “they oughta make a movie” of nearly every title on the shelves.

It is also not a shocker that Hollywood has taken a shine to Comic-Con. Let’s see: 130,000 pop culture fanatics to market to, all in one place, teeming with press. What’s not to like? The advent of social media has only accelerated and amplified the effect that studios hope to achieve—word-of-mouth buzz from trusted, authoritative, and authentic voices, urging their millions of Facebook friends, Twitter followers, blog readers, and online gaming partners to check out this amazingly awesome new thing they saw at the coolest event in the freakin’ universe, Comic-Con!

Note that this doesn’t always work. In 2010, Eunice and I wanted to see the panel featuring the entire cast of the much-buzzed Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, based on the million-selling graphic novel series by Bryan Lee O’Malley and beloved by hipsters everywhere—occupying the prime timeslot of Saturday evening on the Hall H schedule. The panel was fantastic; the clips brought roars of laughter and standing ovations; the filmmakers were clearly simpatico with the source material; the celebrity cast, present in its entirety, was funny and unpredictable (diminutive star Michael Cera was wearing a Captain America costume, complete with padded muscles); and everyone in the hall was probably tweeting, Facebooking, and skywriting at the top of their lungs to tell the world how much they couldn’t wait to see the movie.

Funny thing: Scott Pilgrim vs. the World came out a few weeks later and went straight to the pet cemetery. The Comic-Con buzz generated in Hall H that year was as loud and positive as any I’ve heard about any media property in the 12 years I’ve attended the Con, and it still couldn’t save this offbeat, genre-crossing movie at the box office.

So far, studios have stuck with the comics formula, despite the hit-or-miss quality of the marketing payoff and the spotty track record of comics properties in both critical and commercial terms, because when movies of this kind hit, they hit big. And they spin off sequels and create the coveted “franchise,” a moneymaking machine that brings in bigger audiences with reduced marketing costs each time out.

The result has been a windfall for intellectual property owners (either creators or publishers). For most cartoonists, the money they get just to option a title for development is a big paycheck, even if the film never gets close to being made. Entire comics publishing enterprises now exist to harvest Hollywood dollars, with the comics themselves serving as little more than slick marketing flyers for potential blockbuster franchises. When Disney paid $4 billion for Marvel Comics in 2009, it seemed unlikely that it was all that interested in getting into the comic book business, given that Disney has licensed its own characters to other comics publishers for decades. But Marvel had demonstrated two important strengths: its content was a magnet for tween- and teenage boys, filling a long-time gap in Disney’s market reach; and it had demonstrated the unique ability to bring its entire universe of interrelated characters and stories to the screen in a potentially endless franchise featuring the most popular comic book properties in the world. If Disney even comes close to pulling it off, $4 billion will seem like the bargain of the century.

The snag in this money conveyor belt is all those pesky comics fans. Comics fans take a proprietary interest in the characters and the story lines. Having been burned by bad, campy, or ill-conceived renditions of comics in the mass media that made their enthusiasm seem ridiculous to outsiders, they greet each new announced comics-related project by scrutinizing the creative team, the cast, and the production details, closely tracking the development of the script and publicly debating every breadcrumb of evidence across the Internet. Though the volume of their commentaries vastly exceeds their numbers, studio marketing departments can’t afford to ignore these early influencers. The difference between good buzz and bad buzz leading up to a release can mean the difference between winning the all-important opening weekend and coming in second.

Comic-Con is the Iowa caucus for comics and genre movies: the early barometer that can make or break a campaign. And like the folks who turn out every four years in Iowa to vet their party’s presidential field before the general election, those in the Comic-Con crowd are as unrepresentative of the wider world as they are committed to their particular ideologies. But they are very important, especially because the lights of the media blaze down on San Diego like the Eye of Sauron. Consequently, an amusing asymmetry has emerged in the relationship between the studios and the Comic-Con audience.

Even the biggest film stars who come to San Diego now act as if they are casual comics fans, as steeped in esoteric trivia as the guy in the third row wearing the Ambush Bug costume. I recall the stately Helen Mirren appearing on a panel in 2010 sporting a T-shirt honoring the plainspoken comics memoirist Harvey Pekar, who had died several weeks previously (a very sophisticated choice on the part of her PR staff, I must say). The burden of having to seem geek-tolerant and totally not the kind of popular girl that dissed nerds in high school falls especially heavily on the shoulders of the hot young actresses cast in comics-oriented action movies. Luckily, it doesn’t take much work for them to win over most comics fans. If every star who professed fandom from the stage at Comic-Con actually bought comics, there wouldn’t be a sales problem. But, you know, they’re actors. They can pull it off.

Directors of comics-related properties who come to the Con to discuss their works in progress must go a step further. They are obliged to pay obsequious homage to their source material or face the wrath of the crowd. “We loved [comic creator X, famous only within the comics community]’s vision and want to make sure we get as close to that as possible” is a guaranteed applause line in Hall H, and promises of this sort follow filmmakers through the production process as stills from the movie leak out and are splayed out on dissection plates across the comicsphere. The Con audience is famously fickle, not to mention picky and literal about story details in ways far beyond those of ordinary mortals. Poorly designed costumes, scenes that don’t look right, or evidence of miscast actors can put a comics-related project behind the eight ball with the only audience that’s paying attention years before a film is released.

The problem is, faithfulness to source material is not always the path to box office gold. Many fan-favorite comics are grandiose, bombastic, and slightly ridiculous; it’s part of their appeal. Translating these epics to a live-action medium requires a deft touch. Dialogue that sparkles on the page can die in the mouth of a live actor. Manipulations of reality that a comics artist can accomplish with the flick of a brush might take millions of dollars of computer-generated imagery (CGI) to realize on-screen and still ring false. Most of all, the shift in context can be fatal. Like a goth band playing an outdoor concert on a sunny day, the music may sound the same, but the vibe just isn’t right.

Watchmen (2009) is perhaps the signal example of filmmaking designed to cater to Comic-Con fundamentalism. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s classic 12-issue miniseries came out in 1986 and was later collected into a bestselling graphic novel. It is considered by many to be the literary peak of the superhero genre and a masterpiece of graphic storytelling. Deliberately paced, ornately constructed, and permeated with Reagan/Thatcher-era political paranoia, it was optioned for development almost immediately after its publication, but it languished for a quarter century because no one could figure out how to film it. When the latest project was announced in the mid-2000s, expectations were skyhigh.

Director Zack Snyder, who’d proven his bona fides by bringing Frank Miller’s testosterone-fueled, visually impactful, one-dimensional graphic novel 300 to the screen as a testosterone-fueled, visually impactful, one-dimensional film that looked like Miller’s drawings had come to life, had a couple of ways to go. He could have reimagined Watchmen in cinematic terms by making some changes to the story and narrative to fit the strengths of the film medium. But doing so would have meant tampering with a Sacred Text and courting the wrath of the Comic-Con faithful. Instead, he took the Hall H pledge: change nothing; be true to the literal word and image; recreate the 1986 graphic novel down to the last detail, sparing no expense or CGI trick.

When Watchmen was released to massive hype in the spring of 2009, the wider audience might have wished that he had changed a few things to make the story accessible to people who were just in the theater to see a good movie. Snyder made the film so earnestly reverential that he didn’t correct for flaws in the original or consider how some of Moore’s cold war concerns and 1980s storytelling techniques might fall flat with a postmillennial audience. The visual framing of every shot was adapted almost verbatim from artist Dave Gibbons’s pages and realized with state-of-the-art digital effects, but on the big screen, the costumes just looked silly. The result was a movie that pleased no one: not the mass audience, which found it inexplicably pretentious and confusing; not the comics fans, who found it embarrassing; and not Moore himself, whose work has been particularly ill served in film adaptations over the years.

I don’t mean to pick on Watchmen specifically; Snyder took on a tough challenge and succeeded in some important ways, despite the film’s flaws. But it’s telling that bad comic book movies are often bad in this same overliteral way. With Watchmen, Snyder held a mirror up to the face of the Comic-Con tastemaking crowd and revealed to the world the limitations of the originalist instincts of hard-core comics fans when it comes to making movie blockbusters.

When we talk about the transmedia future, we’re talking about getting this balance right. Comics is a medium unto itself. Watchmen works supremely well as sequential art, where readers can linger over the details, go back and reread different sections, identify with visual and narrative allusions to the history of comics themselves, and savor the buildup of the long story line. All that goodness can be undone by uprooting the property from its native medium. If you try to film a story that was created for comics—whether one as elaborate as Watchmen or as straightforward as The Fantastic Four—without thinking deeply about what parts of the experience carry over into the motion picture medium and which don’t, you end up with a very low-resolution version of the creative concept. That can end up hurting your brand or property with everyone, not extending it to a new audience.

The same problem can sometimes go the other way, when properties licensed from other media are brought into comics. Comic book adaptations of films, TV shows, and cartoons are common, but they have always had a spotty history. Because nearly every reader starts with a fixed mental picture of the original movie or TV show, the sequential art medium has a hard time matching up to live action—particularly when artists are required to capture the likeness of the actors portraying the characters rather than just drawing original characters who fit the story. Even the most successful movie property in comics, Star Wars, fares much better when the creative teams can improvise on the broader themes and tease out dangling plot threads rather than adapting the movies themselves.

Finding the balance for telling satisfying stories across multiple media is the key to the future of comics and pop culture properties as we move from a world of siloed audiences and media types to a global mashup of styles and formats. Sometimes the success or failure of a transmedia project comes down to one brilliant decision (casting Robert Downey Jr. as likably arrogant Tony Stark in Iron Man) or one boneheaded one (thinking Frank Miller was the right guy to adapt Will Eisner’s The Spirit for the big screen), from which all good and bad things about the project then flow. Most of the time, it is more complex.

Hall H is the test lab where these experiments are first exposed to the light of day. It’s not a natural environment, and the peculiarities of the setting and the crowd can introduce some distortions into both the creative and the marketing processes.

So far, Hollywood has been willing to tolerate the distortions and indulge the demanding tastes of the Comic-Con audience in exchange for access to the mother lode of franchise-worthy content from the comics universe and the built-in fan base. As long as this relationship continues, it’s endless summer for the comics industry. All the problems of sales and distribution vanish in a cloud of movie money, and everyone can keep flooding the market with thousands of titles. Comics, movies, video games, toys, and fashion will continue to fuse into “branded transmedia content,” capitalizing on the mind share of familiar names and logos to keep a global audience coming back for more.

Inevitably, however, even long, hot summers give way to the cool and dark of autumn. Big-time disappointments like Watchmen, Scott Pilgrim, and Green Lantern did not kill the comics-movie buzz as thoroughly as Batman & Robin did back in the 1990s, but there may soon come a time when the superhero genre loses its charm for the mass audience. At the ICv2 conference, there were rumblings that the day of reckoning is at hand and that studios might not be so ready to say yes to new projects. In that scenario, what is the value of DC to Warner Brothers, or Marvel to Disney? Where is the path to profits that help BOOM! Studios and IDW and the others repay their investors and keep their creative talent engaged?

“Mainstream comics” have lashed themselves to the mast of the entertainment industry. Their future is now in the hands of studio executives and marketing teams, who see them, and the comics audience, as useful but ultimately disposable pieces in a much bigger game. Waiting in the three-hour line to get into Hall H on the weekend, it’s easy to imagine the future of comics with the transmedia winds at their back. It’s also chilling to consider what might happen if the gales ever subside.

Despite the encroachments of Hollywood, there remains a part of Comic-Con that is still fundamentally about comics and the people who make them, many of whom have no interest in superheroes, movies, or video games. For decades, this “comics-as-art” strain has coexisted with the superhero mainstream, united by a common medium of expression. “It’s all just comics!” has been a rallying cry across the diverse tribes at San Diego for decades. Lately it’s taken on an ironic inflection as serious artists fight with their louder, gaudier, and better-resourced cousins for space and recognition, and you can see the contrasts play out during the five days of the Con.

If you are interested in checking out the variety of personal and independent voices working in comics at Comic-Con, you’d best bring a comfortable pair of walking shoes. The distinction between being a working professional cartoonist, a self-published independent, a small press, or an alternative publisher can be purely semantic, as any one of those terms could translate to “one guy (or gal) doing his (or her) own comics.” But at Comic-Con, the working cartoonists who take free tables in Artists’ Alley are marooned at the far end of Hall G, independents have prime real estate at the front of Hall C, the small press area is in the back by the snack bar, and the alternative publishers like Last Gasp, Fantagraphics, and Drawn and Quarterly occupy a relatively sedate zone between the booths of the collectible comics dealers and the bigger imprints like DC and Marvel.

The scale of these individual publishing enterprises doesn’t necessarily tell you anything about their subject matter. Some ground-level creators are doing superhero or genre-type material in very small print runs or on the web, hoping to get noticed by editors higher up on the food chain; some fine artists are using comics as a medium for visual experimentation and have no interest in traditional comic book subject matter at all; others are working in literary genres, principally autobiography or magical realism, taking advantage of the broader palette of sequential art to add a new dimension to their storytelling.

This last tradition is what cordons off “alt.comics” from other independent and small press activity. These folks take their cues from the underground comics of the 1960s, which themselves descended from comics’ playful, satiric, or absurdist veins, typified by the work of creators like Basil Wolverton, Harvey Kurtzman, and Walt Kelly. In modern times, the influence of Robert Crumb looms large as the inspiration for at least two generations of confessional, explicit, autobiographical stories, illustrated in a deliberately “smaller-than-life” style to contrast with the bombastic affectations of the “mainstream” superhero books.

The undergrounds livened up the medium by introducing adult themes, but the novelty of comics with sex and drugs soon wore thin, and the distribution channel (head shops) collapsed as the war on drugs intensified through the 1970s. Still, the floodgates of creative experimentation were open, and the Baby Boom generation of readers and creators was ready to push the boundaries. The alternative comics movement in North America grew increasingly self-conscious and art-oriented during the 1980s under the editorial leadership of three pugnacious Baby Boomers who will probably cringe at being mentioned in the same sentence: Denis Kitchen (Kitchen Sink Press), Art Spiegelman (RAW), and Gary Groth (Fantagraphics).

Kitchen Sink, from its humble beginnings in 1969, carried the torch of the underground into the 1970s and 1980s, mixing adventurous newcomers like Chester Brown, Joe Matt, Charles Burns, Reed Waller, and Kate Worley with past masters Will Eisner, Milton Caniff, and Al Capp; 1960s-era standouts Jack Jackson, Rand Holmes, Crumb, and Kitchen himself; and up-and-coming talents with a more mainstream bent like Mark Schultz (Cadillacs and Dinosaurs), Don Simpson (Megaton Man), and James O’Barr (The Crow). This blend of old and new helped bring more challenging and personal work to the attention of traditional comics fans without the confrontational edge that fueled others in the movement.

Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly, launched RAW, an audacious oversized magazine in the style of Andy Warhol’s Interview, in 1980, and for most of the decade, it embodied the avant-garde sensibilities pouring out of the downtown New York art scene. Featuring the primitivist stylings of Gary Panter, early work by Charles Burns, and the grotesque pointillist caricatures of Drew Friedman, RAW pushed the aesthetics of comics far beyond anything that had come before. Spiegelman himself carried the ball over the goal line for comics’ first and arguably biggest literary triumph when his Holocaust memoir Maus, told in graphic novel form using animals to depict Nazis and their Jewish victims, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1986.

Groth, along with then-partner Mike Catron (and eventually copublisher Kim Thompson), acquired an old-time comics fanzine called the Nostalgia Journal in 1976 and turned it into The Comics Journal, a fire-breathing news and opinion organ that tried to bring higher standards to comics and comics criticism. In the 1980s, Fantagraphics began publishing some of the most important work by a new generation of U.S. and European alternative comics creators, starting with the magnificent Love and Rockets by Los Bros Hernandez (Jaime, Gilbert, and Mario), and eventually including top talent like Peter Bagge (Hate), Dan Clowes (Eightball, Ghost World), Jim Woodring, and many others. Fantagraphics remains a publishing force to this day; it has recently focused on bringing out deluxe editions of archival material (Peanuts, Krazy Kat) and critical works rather than periodicals.

Through the 1990s, more and better serious work from this movement began appearing, challenging and eventually demolishing old critical prejudices that presumed that any drawn stories were necessarily aimed at children or illiterates. The stylists who got their start in the 1980s and 1990s now produce graphic novels that get respectful reviews in highbrow publications and rank with some of the most interesting literary works of the new century.

The alt.comics booths at Comic-Con are piled high with beautifully designed editions of thoughtful works of fiction, comment, and personal narrative. Some of the most accomplished creators working in any medium are on hand to sign, sketch, and converse. In 2011, Chester Brown, author of a controversial graphic memoir Paying for It (about his personal experiences patronizing prostitutes) that was currently climbing the bestseller charts, was a frequent presence at the Drawn and Quarterly booth, engaging interested parties in discussions about the morality of the sex industry or whatever else was on their minds.

The atmosphere in their section of the exhibit hall is so different from that of its big-media neighbors that it is sometimes hard to believe that you are in the same room. At any other kind of show, these serious artists and authors would be the center of attention. In any other medium, their works would be considered “mainstream,” while costumed superheroes would be shelved in the children’s section. But at Comic-Con, the bestselling authors and serious artists are “alternative,” and they stand watching crowds of adults in spandex costumes bustling off to have their photos taken with Lou “The Hulk” Ferrigno.

The presence of the “alternative” publishers and creators may seem out of place in the circus atmosphere of Comic-Con in the 2010s, but the leading contemporary publishers of literary comics and graphic novels—Top Shelf, Drawn and Quarterly, First Second, NBM, Fantagraphics, and a handful of others—are as important to the artistic future of the comics medium as Hollywood and the video-game industry are to its commercial future.

It should also be noted that the development of comics as a medium for the exploration of serious literary and artistic topics occurred in parallel with the exploitation of comics genres and comics properties in the mass media. Though these are often viewed as interrelated by those outside the industry, including critics and cultural gatekeepers, they are actually two distinct phenomena.

A prime contributor to the confusion between the commercial and artistic successes of comics is the rise of the term graphic novel, originally popularized by Will Eisner in 1977 to distinguish his long-form collection of Depression-era stories, A Contract with God, from other kinds of work that were then being produced in hopes of attracting a mass-market publisher. In the 1990s, as the big comics companies sought to expand their markets through the bookstore channels, any bound collection of work in comics format, from original long-form works to reprinted superhero stories, was designated a “graphic novel” for marketing and categorization purposes. The distinction between comics and graphic novels, which Eisner and his ambitious progeny once hoped might separate artistic and literary efforts from commercial ones, crumbled.

Photo by Henrik Andreasen

Acclaimed graphic novelist Chester Brown promotes his latest work at the booth of his publisher, Drawn and Quarterly.

The commercial end of the spectrum benefits from this confusion because the existence of critically recognized, serious work in the sequential art medium, such as the graphic novels of Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis) or Robert Crumb (Genesis), confers a penumbra of artistic respectability over all comics—particularly those sold in bookstores. This is an ironic reversal from earlier times, when artists working in the industry told friends that they drew greeting cards rather than admit that they did comics. Now even the most commercial-minded purveyors of superheroics and zombie tales can claim the impressive title “graphic novelist”—never mind if their work is any good. In this way, the critically acclaimed work of the serious artists serves as air cover for the colonization of popular culture by the more commercial end of the comics industry.

The process also works in reverse, causing a lot of agita among the literary comics crowd. Critics have come a long way in their ability to discuss works in the sequential art medium intelligently, but there is still a lingering perception that the shared visual language of comics equates to a shared sensibility among all cartoonists, regardless of obvious differences in their styles and interests. The creators of graphic novels, drawn books, and sequential art memoirs are thus presumed to have some kind of inherent affinity with the purveyors of Spawn and Spider-Man just because they are working in the same medium. After all, it’s just comics.

There are some who believe that the presence of serious alt.comics creators and publishers at Comic-Con just muddies the waters. Writer/artist Eddie Campbell, who has given quite a bit of thought to the medium of comics and its history in addition to creating deep and personal work, was absent from San Diego because he did not feel that his current material benefited from association with the more pop culture aspects of the show. Literary comics share an aesthetic heritage with other work in the comics medium (which was quite diverse in terms of subject matter prior to the 1970s), but at this point in the medium’s development, many people feel that the market should move beyond the “Zap! Bam! Pow! Comics Aren’t Just for Kids Anymore” headlines that have topped trend stories on graphic novels in the media for decades. Events like Comic-Con, with their prominent emphasis on superheroes and Hollywood, reinforce old prejudices and do not help promote broader awareness of the potential of the art form beyond the obvious.

Campbell’s point is important, but the boundaries are not so clean. Graphic novels offer a continuum of content ranging from pure pop culture (such as superheroes and fantasy) to realistic genre work (mystery, horror, and so on) to traditional literary topics like general fiction, autobiography, and political commentary. Artists often use the visual dimension of graphic storytelling to make allusions to parts of the comic heritage that are very fan-oriented and pop culture–specific, even in the context of more serious work. The reality is that despite enormous progress in broadening the audience, many consumers of graphic novels are grown-up comic book readers. They understand the visual language and connect to the author’s intentions because of their insider knowledge, just like mainstream fans of superhero comics.

There is also a lot of crossover among the creative talent, partly because few alt.comics publishers can match the paychecks of the mainstream. Matt Kindt, creator of the delightful graphic novel Super Spy, has done work for Marvel and DC; David Mazzucchelli drew Daredevil and Batman in the 1980s before he produced his 2010 tour de force Asterios Polyp. Even the mostly independent Campbell has done the odd job for DC and Vertigo. This does not make these creators less serious by any means, but it does end up creating some cross-pollination of readership.

Though its audience and talent pool may overlap with that of the commercial comics industry to a larger degree than it might want to admit, the alt.comics scene is largely self-contained and pursues its own aesthetic. Most of the time, this crowd gathers at indie-oriented comics shows like The MoCCA Festival, sponsored by New York’s Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art, the Small Press Expo (SPX), the Alternative Press Expo (APE), and Portland’s Stumptown Comics Show, where its revels are undiluted by the presence of costumed fans and professional wrestlers.

Because the direct market has not exactly been kind to nonmainstream comics over the years, many creators and publishers have tried to develop separate distribution channels to avoid the fist-sized knot of traditional comics stores. Alt titles have found homes in music shops, art galleries, specialty stores, and independent bookstores (though their distribution prospects have lately dimmed in tandem with the general decline of independent retail). Many top talents are published by traditional book imprints like Norton or Random House, and avoid the direct market almost entirely. Some top creators took to the Internet much earlier than the larger players (usually in the form of advertising-supported or syndicated webcomics or comic/blog hybrids rather than as digital downloads). As we will see, a lot of the most successful online comics creators fit more neatly into the “alternative” or “new mainstream” modes than they do into the popular print genres, and these are the folks who have figured out how to make a living completely outside the old publisher/distribution model.

Their transmedia model works differently as well. When alt.comics properties make it to the big screen, as in the case of Ghost World, Persepolis, and American Splendor in recent years, they look and behave more like adaptations of books than like adaptations of comics. It’s hard to imagine anything in the alt.comics space becoming a “tentpole franchise” or summer blockbuster material, and it’s even harder to imagine the work of, say, Chris Ware or Alison Bechdel being made into a video game.

The continued artistic development and critical reception of alt.comics seems assured. Their access to their audience is not as problematic as that of comics sold exclusively through the direct market, and the barriers to digital adoption are not as profound. In September 2011, the alt.comics publisher Top Shelf started making complete graphic novels available in digital format through various channels at appealing price points, and others are likely to follow suit. Graphic novels figured heavily in the launch strategies of Amazon’s and Barnes & Noble’s competing tablet products that debuted in late 2011. It stands to reason that literary-oriented graphic novels with appeal beyond the superhero fan base are a killer app for hardware and content vendors selling to the affluent, literate, and tech-savvy early adopters who will decide the first round of their competition.

The publishers who specialize in graphic novels and reprints are also likely to hang on to whatever market remains for high-end, well-designed print books, because the design of graphic publications frequently adds a lot to the content, and the packaging is part of the total creative conception. Their audience is not just the Wednesday comics shop crowd but book buyers: people who do not mind shelling out for a handsome edition that sits proudly on the shelf or the coffee table.

What is uncertain is whether literary comics and graphic novels will continue to remain a part of popular culture just because they share a graphic vocabulary and heritage with mainstream comics. As DC, Marvel, Image, and the others form closer connections with other media and the commercial entertainment industry, alt.comics will continue to push the aesthetic and storytelling boundaries of the medium. Their talent pools and audience may diverge even further as new generations of creators emerge who owe less to the common comics ancestry and more to their immediate influences in art and literature. The continued presence of the alt.comics community at venues like Comic-Con will serve as a test to determine whether the world of popular culture still has a place for the artistic and the experimental.

If it turns out that the big comics publishers can’t survive the current market challenges—if digital distribution leads to the demise of the direct market, or if the relationship with Hollywood sours—the future of comics may belong exclusively to the individual voices and the small presses. In that scenario, the entire perception of comics within the culture would shift away from spectacular superheroics and genre work, and be seen increasingly as the province of idiosyncratic artists working in a medium of words and pictures. In this “Ghost World” of high artistic achievement but low cultural salience, the industry, the vocation, and the hobbyist aspects of comics would be much diminished in economic viability, but the respect accorded to top creators and prestigious editions of their work would be at an all-time high. Comics as popular culture would fade away, replaced by a more exclusive and niche-oriented art form.

There is precedent for this kind of rapid marginalization of a mass entertainment medium. In the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, jazz was American popular music. When the economics of the postwar period made it hard for the big bands to maintain their audience through touring, smaller groups turned to styles like bebop, which emphasized individual voices and challenging harmonics. This appealed to critics and serious listeners, but it alienated the mass audience that wanted accessible dance music. By the 1960s, jazz listeners consisted primarily of connoisseurs and fellow musicians, and jazz had been supplanted in the popular music vernacular by rock and roll.

A future in which American comics have transcended popular culture, for better or worse, is hard to imagine when walking the Comic-Con exhibit hall in 2011—a place that savors more of Ozzy Ozbourne than Thelonious Monk. But then again, it was probably hard to imagine the intimate jazz clubs and cultural festivals of today from the packed dance floor of the Savoy Ballroom in 1941.

After spending the morning hanging out with creators whose individual visions are pushing comics into the future, I planned to spend the afternoon basking in comics’ glorious past. Buried deep in the Comic-Con Events Guide is a programming track dedicated to interviews and discussions with the art form’s most illustrious living creators and historical figures, or tributes to ones who are no longer around.

These panels were the centerpiece of Comic-Con in the old days, before the Hollywood-transmedia deluge. Motivated by a desire to recognize the neglected heroes of the early days of comics, fans would get together to talk about, or with, Jack Kirby, Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman, and other pioneers. Because the American comic book industry traces its roots only as far back as the 1930s, a great many of the most important figures were active into the 1970s, 1980s, and beyond. Some had moved on to other pursuits and had no idea that anyone took their comic work seriously until they trundled out onto the Comic-Con stage to peals of applause. Attending these panels was the equivalent of going to the Constitution Center in Philadelphia to hear the Founding Fathers themselves debate the fine points of federalism: super cool if you happen to be into that kind of thing (and worse than watching your grandmother clean her dentures if you are not). For longtime attendees, this track of programming is Comic-Con; everything else is just noise.

The sentimentality and nostalgia that inspired the early fans are woven into the DNA of the institutions they created, including Comic-Con. Vestiges of the old ways have persisted even as Comic-Con mutated into the pop culture monstrosity it has become in the 2010s. Heidi MacDonald calls these atavistic relics “ancient Pictish rituals,” equating them to the mysterious folkways of rural Britain that survived succeeding waves of foreign conquerors. Their antiquity confers authenticity, a commodity that is more valuable at Comic-Con because of its short supply. Panels featuring old-timers are lightly attended, but they are real. They anchor comics fandom and comics conventions in something other than consumerism and spectacle.

These days, the ranks of the Golden Age greats have thinned to nearly bare, but even into the current day it is possible to make a human connection to the very beginnings of the industry. Jerry Robinson, an artist who worked on the first Batman stories in the late 1930s (he created the Joker) and remained a vocal advocate for creators’ rights throughout his long career, was signing, sketching, and greeting fans in Artists’ Alley between panel appearances and interviews at the 2011 convention. (He passed away the following December at age 89.) A few others from this era are still around if you know where to look. But time marches on, and soon we will say goodbye to the last of the founding fathers.

We may also soon be saying goodbye to the first generation of fans who cared about them, and that is arguably an even greater break from the past for comics, Comic-Con, and the widening world of pop culture in which comics play a part. All popular art forms and hobbies have fans, but comics fandom is unique in the way it combines nostalgia, scholarship, amateur creativity, advocacy, community, and performance. Fandom has traced its own arc in parallel with that of the comics industry and the comics art form, and has been influenced by the same dynamics present in the wider culture, including technology and the procession of generations.

In today’s social-media-driven, always-connected world, it’s trendy to talk about “co-creation of content” and “crowdsourcing your brand” to customers. Comics fandom has embodied this principle for more than 50 years. To be a comics fan, it is rarely enough to simply “like” comics; you need to know them inside and out, and to express opinions that reflect your well-developed tastes. Sometimes this takes the form of creating original works in beloved genres or using familiar characters and scenarios.

Comics fans were early adopters of “fan fiction” (independent and unlicensed stories featuring characters from popular comics, films, and TV shows like Star Trek), which has proved to be a bane to litigious-minded corporate IP owners. As software and networks lowered the barriers to publishing and media creation, fan fiction extended to digital media and community sites with wide reach, forcing content owners to either reach an accommodation with fans or confront them more directly with cease-and-desist letters (a strategy that usually comes with disastrous PR blowback).

Fan-produced Star Wars films, screened annually at Comic-Con, feature stunning production values and special effects in addition to story lines that build on the mythos. Lucasfilm offers awards, and sometimes jobs, for the winners. Original works like the web series The Guild have added a layer of professionalism to the fan-fiction tradition, creating a revolutionary new channel for the creation and distribution of video content. Production companies in the 2010s are paying close attention to this trend, and original web-produced series are likely to play a very big part in the media mix as the decade unfolds.

Today, businesses in a wide variety of industries are investing billions to generate the kind of fan engagement that comics have had since their earliest days. The comics industry anticipated, sometimes by decades, best practices around customer relationship management, at least with readers and fans. As far back as the 1960s, editors engaged in dialogues with readers in the letter pages of the magazines. DC editor Julius Schwartz printed the addresses of his correspondents, encouraging fans to form connections with one another in a postcard-driven social network. These connections laid the groundwork for the fandom that eventually snowballed into comics culture and Comic-Con.

Marvel editor-in-chief Stan Lee established a clear voice for the Marvel brand in his house ads and “Stan’s Soap Box” columns, giving birth to the catchphrases that follow him around half a century later (“Face front, true believers!” “Nuff Said!”). These little touches made readers feel special, and they provided differentiated value to the content of Marvel comics that was obvious to anyone who was paying attention at the time. The brand loyalty of “Marvel Zombies” is legendary, and in some cases it persisted well into adulthood.

DC Comics even conducted an early experiment in crowdsourcing in the late 1980s, asking fans to determine the fate of an annoying new version of Batman’s sidekick Robin as his life hung in the balance. Bloodthirsty readers gave the new Robin (Jason Todd) the thumbs down, and the creative team dutifully had him killed in an explosion. Companies looking to the wisdom of crowds for product development guidance might want to keep this example in mind.

When the Internet came along, comics publishers were among the first to set up organized sites and chat rooms to engage fans online. Though these often degenerated into pools of rancor and invective, they clearly ignited the passions of the audience and created a sense of intrigue and anticipation around every new story line, every change in creative teams, and any rumors of upcoming developments. The convention panel appearances of Marvel chief creative officer (formerly editor-in-chief) Joe Quesada or his DC counterpart Dan DiDio took on the atmosphere of Pentagon briefings, with closed-mouthed executives and sworn-to-secrecy creative teams sparring with fans and bloggers digging for details.

The intensity of dedicated fans can be a bit overwhelming to ordinary people. Though nerds have broken through to achieve greater recognition and a modicum of respect in the mainstream culture, portrayals such as those on CBS’s popular comedy The Big Bang Theory are funny because they are kind of true. Marketing professionals like to talk about consumer influencers and opinion leaders. These folks have plenty of opinions, highly refined taste in their fields of interest, and a great love of sharing their views. Because they clearly do not court popularity in the conventional sense, their voices are highly credible—and they know it.

The high level and changing nature of fan engagement since the early 1960s has influenced the development of the medium, both commercially and artistically. Crossover between fans and professionals is common; the letter columns of 1960s DC and Marvel comics are studded with missives from future writers, artists, and editors. Today a lot of the top fan-oriented publications are edited by ex-pros. Companies shape their plot lines and “event” story lines to suit the tastes of fans, and go to great lengths to create intrigue in the fan community around the most picayune details of story and art.

The close attention to the content of comics, their history and development, and the importance of individual styles give comics fandom its coherence and keeps fans engaged, because the conversation never ends. The reverence for the past is conservative in the best and truest sense of the word; it is the glue that binds all the tribes of Comic-Con together after 40 years. But it is also fundamentally backward-looking, and at its worst, it draws current-day comics continuously back to tropes, story lines, and formats that are well past their sell-by date.

The contributions of the early comics fans was the subject of the panel I attended on Friday afternoon. One of the themes of the 2011 Comic-Con was the fiftieth anniversary of fandom (the first amateur-published writing about comics history dates to 1961). A dozen of the most illustrious veterans of those days were invited as special guests, with events and celebrations sprinkled throughout the weekend. I was a few minutes late for the start, but this was not a panel where you had to worry about getting into the venue. It was in one of the smaller meeting rooms, and the room was less than half full when I arrived.

On stage, the panel’s moderator, Mark Evanier (himself an early fan-turned-professional and a member of the exclusive San Diego “lifers” club, attending every show since 1970) was encouraging the participants to tell stories about how they went from being people who were interested in old comics to the progenitors of a subculture. The panel was an interesting assortment. Dick Lupoff, an accomplished science fiction author, and his wife, Pat, have bragging rights to not only being the first fans to publish a comics-oriented column in their SF zine Xero back in the early 1960s, but being the first fans to dress up in superhero costumes (as Captain and Mary Marvel). Maggie Thompson and her late husband, Don, followed shortly thereafter, and later achieved success with the professionally published Comic Buyers Guide. Writers Roy Thomas and Paul Levitz not only made the leap from fans to comics professionals, but climbed to the highest pinnacles of the industry. Thomas succeeded Stan Lee as editor in chief at Marvel in the mid-1970s; Levitz is the immediate past publisher (and previously editor in chief) for DC, stepping down in 2010.

All these folks got their start publishing mimeographed newsletters and amateur comics in the 1960s, in print runs of several hundred at most. Their project was to gain appreciation for the medium of comics and recognition for the talents of their creators. Typical of the pre-Baby Boom “Silent Generation,” these early fans brought diligence, attention to detail, and a sense of moral purpose to their efforts. The first zines were infused with a sense of discovery and nostalgia, but also a kind of missionary zeal to make readers understand the true genius of Carl Barks (the uncredited artist who drew the best-loved Disney duck stories) or the epic grandeur inspired by the nearly forgotten heroes of DC’s Justice Society of America.

At the time they were writing, comics were seen as disposable entertainment for children at best, and as fiendish corruptors of young morals at worst. No one, not even most people involved in the industry, took much pride in the work. Only a few audacious voices, like that of Will Eisner, had ever claimed that comics could be anything approaching art or literature. A few dedicated fans set out to change that, and half a century later, the entire world has come around to their view. It’s a rather remarkable achievement.

The first generation of fans made its case with an optimism and earnestness characteristic of the pre-Vietnam 1960s. Before long, the Baby Boomers arrived, supplementing the nostalgic appreciation of the pioneers with an enthusiasm for the current crop of comics (primarily the groundbreaking work being done by Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, and Steve Ditko at Marvel), a strident agenda of social, political, and aesthetic concerns, and a self-conscious sense of being part of a movement.

Newcomers like Gary Groth, the fiery young publisher of the Comics Journal starting in the 1970s, grew increasingly disgusted with the sentimentality and lack of rigorous critical approaches that pervaded old-school fandom. Groth brought a righteous tone of Boomer activism and real-world engagement to comics criticism, even if the Journal’s intellectual reach sometimes exceeded its grasp. Still, the sense of higher purpose was empowering and sometimes effective: in the mid-1980s, Groth took on a fellow precocious and pugnacious boomer, Marvel’s then editor in chief Jim Shooter, over Marvel’s shameful treatment of Jack Kirby when the old master was in failing health. Eventually Marvel blinked and Kirby got a decent settlement for the return of his original art.

Trina Robbins, who started out in the 1960s underground movement, brought the values of 1970s-era feminism to comics scholarship as she began a lifelong project to discover and celebrate the voices of great women creators who contributed to comics history, though it was a Generation Xer, Heidi MacDonald, who formed the first important fan group to recognize women in the comics industry, Friends of Lulu, in the early 1990s. Publisher and cartoonist Denis Kitchen, another veteran of the underground, helped move fandom toward political action, founding the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF) in 1986 to support retailers that were being persecuted by local authorities.

By the mid-1990s, the leading edge of Generation X was approaching age 30 and starting to rediscover the comics of its youth, the 1970s, which Boomers disdained as inferior to those of their own cherished childhood. Comics in the 1970s were hastily produced and cheaply printed, and they reflected the shrill social attitudes of the young Boomer creators who were coming into the industry, which mature Boomers found vaguely embarrassing by the 1990s.

John and Pam Morrow, who ran an advertising agency in North Carolina, launched The Jack Kirby Collector in 1994 to cultivate appreciation of the classic comic book artist/writer, whose reputation had suffered at the hands of Boomers who were disappointed with his later work. The Morrows’ detailed and professional fanzine soon attracted the interest of the crowd of aging “superfans,” some of whom had worked in comics during the 1970s and 1980s, as well as a rising crop of Generation X fans who were creating their own communities through e-mail listservs like Kirby-L and ComicArt-L in the early days of the Internet. Today, the TwoMorrows enterprise offers a huge assortment of magazines, monographs, how-to books, biographies, and indexes of comics, mainly focusing on the 1970s to 1980s era. The TwoMorrows booth at Comic-Con, near the front of the hall in the section dominated by old comics dealers, is a popular hub and meeting spot for this cohort of fans. The obsessive detail and pervasive nostalgia of the TwoMorrows publications represent the logical end point of the fannish scholarship pioneered by the first generation. Unfortunately, the attention to detail sometimes veers into a self-parody of kitschy Generation X trivia-mongering that the rising generation of Millennials finds peculiar and offputting.

As we move deeper into the digital era, twenty-first-century fandom is no longer curated and managed by a clique of mandarins with mimeographs. Today’s online comicsphere is immediate, interactive, social, and collaborative, and it stretches across thousands of Facebook groups, blogs, news sites, chat rooms, and Twitter hashtags, brimming with conversation, commentary, rumors, gossip, snark, misinformation, amazing amateur and semiprofessional work, and communities for every conceivable subculture. It is also focused on the here and now of the industry much more than on its illustrious and overexcavated history. Reviews and essays are posted on hundreds of blogs. Opinions are shared in chat rooms and community forums. Hundreds of comics-centric “weblebrities” publish weekly video feeds and podcasts. Some, like “The Nerdist” Chris Hardwick, have parleyed this into a larger media footprint. Plenty of comics creators maintain an online presence and often engage in heated give and take with fans. Many are driven mad. Twitter has kicked things up yet another level by providing a level of personal connection between pros and fans. Comics writer turned award-winning fantasy author Neil Gaiman (@neilhimself) was among the first to break a million followers on the service.

The changing taste and behavior of fans is critical to an industry where fans may be the only ones paying attention, and fan influence has affected the efforts of publishers to reach a wider audience. The affection of the 1960s-era fans for 1940s-era comics resulted in the revival of many of these characters, most famously the old DC superhero team, the Justice Society of America. The narrative contrivance that made this possible, involving the creation of alternative dimensions and timelines, ended up burdening the DC universe with newbie-unfriendly plot complications that ripple down to the present day.

Boomer demands for social relevance, maturity, and “realistic” story lines was manifested in the “grim and gritty” style of the mid-1980s, kicking off auspiciously with Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen, but soon leading comics into a very dark dead end. The classic revivalism of Generation X fans led to a boom in “retro comics” in the late 1990s, typified by Kurt Busiek’s Astro City and Mark Waid and Alex Ross’s Kingdom Come, which championed traditional themes and styles above the exhausted postmodernism of the previous period. Frank Miller once derisively referred to this trend as “nostalgia with a nose ring.”

Today, the ahistorical, media-influenced perspective of Millennials is competing with the legacy of older fans who remain active and vocal. The two different polarities seem to be confusing the hell out of the industry and making it more difficult for it to move forward with confidence. The desire, or perhaps requirement, to cater to old fans with long memories leads publishers to endlessly recycle properties that have no relevance to the current day, while at the same time doing away with decades of history in a desperate attempt to bring in young readers who don’t know or care about continuity with the past.

Fandom is both the rudder that helps all pop culture media steer toward the future and the anchor that keeps them bound to the past. Resolving the competing agendas of fans can be a bit like negotiating a trade agreement between warring countries. But the future of comics within pop culture uniquely depends on its ability to balance respect for its heritage with an awareness of the here and now.

At 5:00, we skipped out of the end of our last panel and headed back to our hotel to rest up a bit before our brief stint as on-duty event staff. Each year, Eunice and I work with Jackie Estrada and her team to help put on the Eisner Awards—the comic industry’s version of the Oscars. The awards open to the public at 8:15 p.m. and go on for nearly three hours, but prior to the public event, there is a buffet dinner served to nominees, publishers, guests, and sponsors. The room decorations, the registration area, and the stage all need to be set up in advance of that. That task falls to a core group of five or six veteran badged event staff members, including ourselves, and a small army of volunteers.

By 6:00, we’d made our way to the Hilton Bayfront hotel, on the other side of the convention center from the Marriott. Jackie and her assistant were already there with their clipboard and box of materials. Eunice grabbed the stack of labels and table tents indicating which of the nearly 40 tables at the front of the room had been reserved for each group of sponsors and nominees.

Vicky Gunter, Jackie’s no-nonsense lieutenant in charge of getting the tables ready, gave instructions to the crew of volunteers. The placement of decorations, name tags, and gift bags is handled with the protocol of a diplomatic summit. Once the setup was complete, Eunice and Vicky stepped outside into the lobby to man the registration table. VIP access is strictly controlled and reserved for invitees and paid sponsors only. Jackie goes to great lengths to determine exactly who is coming and how many guests each is bringing, but each year there are some inevitable misunderstandings, and some Very Important Person storms off with feathers ruffled when she discovers that there is no accommodation for her eight-person entourage of unannounced guests. On one memorable occasion, Eunice turned away the editor in chief of Marvel Comics because he was not on the list (he later got in as the guest of one of his writers).

At 8:15, the doors open to regular attendees, who sit in the back of the room. There is capacity for six or seven hundred, but the event generally draws about a third of that. Over the years, Jackie and the Comic-Con staff have tried to make the ceremony more fan-friendly, adding celebrity guests and presenters, music, stand-up comics, and voice actors as emcees and, for the first time in 2011, using a professional event production company to tighten up the timings and music cues. Despite everyone’s best efforts, the Eisners rarely wrap up before 11 p.m.

I returned to the staff table as the setup was just about complete. An unassuming-looking bearded fellow was seated alone at the table, flipping through a program. He was not part of the setup crew and his badge was not visible, so I introduced myself and politely asked him what he was doing there.

“It’s OK, I’m convention staff,” he said.

“What do you do?”

“I’m John Rogers. I’m the president of Comic-Con.” That sounded fairly important.

“Really? I had no idea. We’ve been coming here 13 years and have been helping with the Eisners for about 8. It’s amazing we’ve never seen you.”

“That’s good,” he said. “Usually the only time you see someone like me is if something goes wrong.” He said the organizers like himself, longtime Comic-Con executive director Fae Desmond, and the rest of the management try to stay in the background during the show, letting the spotlight fall on the attendees, celebrities, and festivities.

One can hardly blame them. Coordinating all the moving parts for a show as gargantuan and all-consuming as Comic-Con would be a full-time job for a company of military logistics specialists. Yet Desmond manages only a small full-time staff and Rogers himself holds down an outside job as a network security specialist. I can see how they must have little time to eat, sleep, and bathe, much less court any kind of attention, when things are in motion. Still, for all the enormous number of things that could possibly go wrong in the weeks and months beforehand, let alone the five-day window when Hurricane Comic-Con actually hits San Diego, there have been remarkably few blemishes on any front over the show’s 41-year history. Love Comic-Con or hate it, you have to respect the mad skills of the folks who run what is, remarkably, a nonprofit operation.

As we were talking, Jackie Estrada, who had left to change into her evening attire, swept into the room in a glittering dress, accompanied by her husband, Batton, and trailed by several frantic staff people waving papers. On the podium, emcee Bill Morrison (Futurama, The Simpsons) and his wife, Kayre, were going over a few last-minute details on staging and delivery. A few guests began filtering in and filling their plates at the buffet line. Almost everyone was at least a little bit dressed up, a small victory in the long twilight struggle against the “Comic-Con look”—large bearded men in baggy shorts and sneakers, popularized by director Kevin Smith—that Jackie and Batton have been waging in an attempt to class up the Eisner ceremony.

Details like that are critical. Nearly everything surrounding the Eisner Awards involves some degree of intrigue. Though they are the oldest surviving comics industry award, and carry the name and blessing of Will Eisner, one of the most important figures in comics history, they struggle for prestige and visibility even within the universe of comics fandom. A competing set of awards, the Harveys (named for Mad magazine creator Harvey Kurtzman), are handed out later in the summer at the Baltimore Comic Con in many of the same categories. There are also the Ignatz Awards (mostly for independent comics), the Shusters (for Canadian creators, named for Canadian-born Superman artist Joe Shuster), the Shel Dorf Awards (named, ironically, for the founder of San Diego Comic-Con, but presented at the Detroit Fan Fair), and the winners of various reader polls.

Every so often, an unexpected title will get nominated or win, but there is rarely much controversy over nominations because so little is really at stake. There is no evidence that winning an Eisner or any other award makes any difference to sales or to the rates commanded by creative talent; it probably won’t help you get your title turned into a movie if there hasn’t already been some interest from studios. It is even sometimes a struggle to get publishers to include the award logo on the covers of winning publications.

The honor of association with Will Eisner remains the award’s biggest asset. Each year up until his death in 2005 at age 89, Eisner himself would stand on stage through the entire ceremony, presenting the statues to the winners. As one recipient remarked in his acceptance speech, “How cool is this? You don’t get an Oscar Award from a guy named Oscar!” Eisner himself even won occasionally, which made for some amusing moments. Now that the master is gone, the Eisner Awards must find ways to up the ante in terms of relevance, especially in the pop culture media beyond the world of comics fans and bloggers. That is Estrada’s single-minded focus as she shepherds the awards from nomination to judging to the big Friday night ceremony.

In recent years, Estrada has brought in a grab bag of celebrities, including Samuel L. Jackson, the cast of the film Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, Tom Lennon and Ben Garant of the Comedy Central series Reno 911, superstar comics creator and film director Frank Miller, Go-Gos guitarist Jane Weidlin, and others to liven things up. A high-water mark of sorts was achieved in 2008, when British comedy host Jonathan Ross left his copresenter, Comic-Con deity Neil Gaiman, speechless after a rapid-fire burst of hilarious innuendo capped with a full-on kiss on the lips.

The timing of the gala has given Estrada yet another battle to fight. The tradition of handing out the Eisners on Friday nights goes back a long way in Comic-Con history, but Friday has become party central, and in the megamedia era, that means that all the big players tend to host their exclusive, fancy blowouts at the same time. Even some creators who don’t have golden tickets to these shindigs regard the three-plus-hour awards ceremony as a chore. Much of the U.K. contingent, usually including at least a few nominees, goes for an epic pub crawl on Fridays and can scarcely be “arsed” to make an appearance to claim their hardware.

Gaining wider attention for events like the Eisner Awards is important to the future of comics because they provide institutional legitimacy to an art form that is still on the margins. The Eisners are one of the few venues that do not distinguish between “mainstream” superhero comics and the “alternatives”—a dynamic that helps traditional comics by associating them with books that are already recognized as high quality in the wider world. There are categories for everything under the sun, including more than a dozen creative categories (best penciller, best inker, best colorist, best letterer, and so on) and some very specific content categories (best U.S. edition of foreign material—Asia, Best Limited Series, Best Collection of Archival Material) where even being nominated can draw attention to overlooked work.

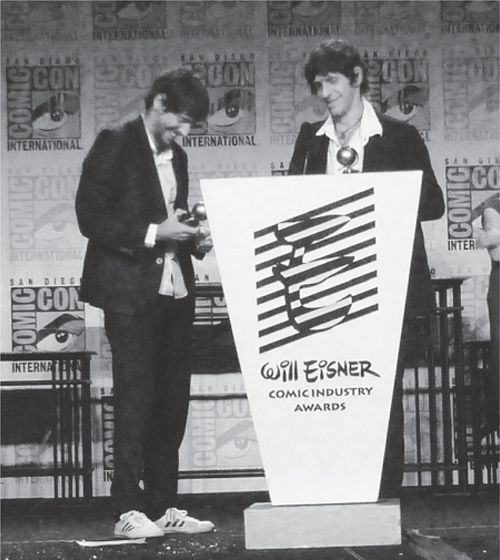

Photo by Jackie Estrada

Brazilian artists Gabriel Bá and Fabio Moon accept their Eisner Awards.

The efforts have paid off to a certain extent. It may be a while before the Eisner ceremony is broadcast live, but in a relatively short time, the awards have gone from a homemade, industry-insider banquet to a gala worthy of coverage by the likes of Publisher’s Weekly, USA Today, Entertainment Weekly, and other big-time outlets. Every time an Eisner winner is announced on the on-screen crawl on G4 Network, another clump of pop culture fans gets exposed to this forgotten corner of the entertainment world, or is reintroduced to the source of content that they enjoy in other media. These are the steps by which a marginal industry claws its way back to the center of the wider cultural conversation.