A statue of Cincinnatus, who epitomized the selfless virtues of the early Roman Republic, in his namesake city of Cincinnati, Ohio.

The Battle of Actium, in 31 B.C., in which Antony and his lover, Cleopatra, ruler of Egypt, were defeated, marked a seminal moment in the life of the victorious Octavian (63 B.C.–A.D. 14), Julius Caesar’s grandnephew, who, having avenged the assassination of his great-uncle, became the most powerful man in Rome with the consent of the Senate, which bestowed upon him the honorific title of Augustus, an adjective transformed into a noun meaning “the most venerable one.” This event, which coincided with Rome’s rise to world superpower, also marked the end of the republic (established around 509 B.C.) and the beginning of the empire. The peace and stability that Rome experienced under Augustus’s imperial rule ushered in a long period of peace and prosperity, known as the Pax Romana, that lasted almost two hundred years.

The image of the empire orbiting like an awesome solar system around the brilliant accomplishments of Rome has always maintained a very special place within the mythical realm of Western culture. That luster, however, becomes much more problematic when one considers the critical voices that, wary of the empire, nostalgically mourned the passing of the virtuous republican ethos that had governed the city for nearly five hundred years.

One of the most notable supporters of the Roman Republic was Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 B.C.), the moral philosopher, lawyer, and brilliant orator whose blistering words of admonition left a long shadow of prophetic doubt over the glittering glamour of the newly established empire. Cicero was born in Arpinum, a small town south of Rome, into a well-to-do family. It is believed that his ancestors became wealthy by cultivating chickpeas—cicer, in Latin, from which his cognomen, or last name, might have originated. Cicero was an ambitious man who tirelessly worked at gaining political prominence in Rome. His marriage to Tullia, who was a very wealthy woman, was apparently dictated by the opportunistic realization that her wealth could be an asset in advancing his political career. Cicero’s true love was his daughter Tullia. When she died at a very young age, Cicero became inconsolable. To try to cope with his sorrow, he turned to the writing of Greek philosophers, but he was forced to admit that “grief defeats all consolation.”

Throughout his life, which was punctuated by years of civil unrest in Rome, Cicero never relinquished his faith in the republican system and therefore never accepted the ascent to power of Julius Caesar, the general who, after challenging the authority of the Senate, defeated his rival Pompey and went on to become dictator. In Caesar’s arrogance and ambition, the moral philosopher perceived the insidious threats to society against which he had long warned his compatriots. The target of Cicero’s severe indictment was Caesar’s ruthless dismissal of the selfless commitment of those who, during the republican years, had served the city’s grand destiny without any demand for personal power and recognition.

As with most educated men of his times, Cicero learned Greek at a very young age. After being exposed to the vast well of Greek knowledge (which, as we will discuss in depth later, Rome acquired when it conquered the Hellenistic kingdoms), he became particularly taken by the teachings of the Stoics, whose wisdom he weaved into and adapted to his own political thinking. The point deserves to be stressed: Cicero’s Stoicism was a distinct, Romanized version of the Hellenistic philosophical school founded by Zeno of Citium (not to be confused with Zeno of Elea) in the early part of the third century B.C. As we have seen, according to the Stoics the universe was an animated entity organized by a divine Intelligence. Because man was endowed with reason, he had the capacity to recognize the superior order that sustained the perfect organization of the cosmos. To live in agreement with that intrinsic harmony, man had to emancipate himself from the disorderly interference of passions (such as ambition, greed, envy, and fear) to reach a calm and detached state of mind called apatheia, meaning “without pathos.” Contrary to our modern interpretation of the word “apathy,” apatheia for the Stoics indicated the steady and calm attitude of those who succeeded in purifying the mind of the enslaving and misguided effects of passion. The belief that beyond the apparent confusion and contradictions of the world a divine Reason had preordained the destiny of all living things armed the Stoics with a great amount of patience and resilience. Even the death of a loved one did not upset a true Stoic, for whom the adjective “tragic” was applicable only to the failure to accept, with virtuous fortitude, whatever the divine wisdom had established, no matter how incongruous with man’s reason the divine motifs might have appeared.

Zeno’s inward attitude and his excessive tendency toward acceptance and resignation were profoundly revised by Cicero, who gave Stoicism a much more pronounced and engaging public and political spin. Cicero’s main concern was the defense of the Roman Republic. With that purpose in mind, Cicero used the Stoics’ emphasis on courage, endurance, and self-discipline to affirm that virtue occurred when man, in agreement with the orderly laws of the universe, chose reason as the driving force of life and society. In his Laws, Cicero wrote, “Since, then, there is nothing better than reason, and reason is present in both man and God, there is a primordial partnership in reason between man and God.” As a divine-instilled talent, the development of reason represented man’s greatest accomplishment and the highest form of virtue: “Moral excellence is reason fully developed.”

As we have seen, Aristotle had optimistically believed that nature had organized everything for the best. That truth, he argued, was apparent in the gift of reason that had given man an instinctive urge to live with others. In agreement with Aristotle, Cicero, in his book On Duties, maintained that true humanness occurred when man developed to his utmost the social talents for which he was created. “We are not born for ourselves alone,…but our country claims for itself one part of our birth.”

Because reason was man’s most ennobling characteristic, creating a good and orderly society was the best way to conform to the ethical principles that the divine intelligence had encoded in the harmonic workings of nature. The idea fostered the long-lasting belief in a fixed, eternal, and self-evident natural law universally valid for all people in the world. As Cicero stated in his Republic, “Law in the proper sense is right reason in harmony with nature. It is spread through the whole human community, unchanging and eternal….This law cannot be countermanded, nor can it be in any way amended, nor can it be totally rescinded. We cannot be exempted from this law by any decree of the Senate or of the people; nor do we need anyone else to expound or explain it. There will not be such law in Rome and another in Athens, one now and another one in the future, but all the peoples at all times will be embraced by a single and eternal and unchangeable law….Whoever refuses to obey it will be turning his back on himself.”

Because for Cicero the political collaboration that had animated Rome’s res publica (“public affairs,” from which derives the word “republic”) had best represented the wisdom of a fully developed reason, he was fond of saying that Rome had been “the most religious of all nations.” As used by Cicero, the term “religion” involved not a spiritual and metaphysical detachment from reality but rather the bond of trust, discipline, and responsibility that had denoted the patriotic spirit of the early citizens of Rome. If the Roman Republic had been an example of religiosity, Cicero held, it was because the lawful concordance that had animated its civic spirit had faithfully mirrored the harmonious concordance that ruled, at a universal level, all other aspects of nature.

Even though the republic, as conceived by Cicero, did not survive the test of time, his ideas remained a powerful point of reference for Western culture for many centuries to come. On the subject, Neal Wood in Cicero’s Social and Political Thought writes, “American constitutionalists, no less than French revolutionaries a decade later, thought of themselves as heirs to the Roman republicans and most appropriately looked to their greatest political thinker [Cicero], the cultural statesman and pater patriae, for tutelage in the colossal task of founding a new order.” To better understand these ideas, we must briefly review the history of Rome.

Rome was founded on the banks of the river Tiber in 753 B.C. Initially, the city was ruled by Etruscan kings, but that dominion came to an end in the sixth century B.C. with a rebellion of a group of Latin tribes who defeated the Etruscan kings and replaced them with a republic led by two consuls, appointed for one year, and a senate whose members served for life.

The distribution of power that the system assured was aimed at minimizing the risk that a monarchical rule of one would ever return—a prospect that the Romans vehemently opposed, just as the Greeks of classical times had done before Alexander the Great brought to an end the era of the polis.

Even though being an aristocrat (meaning a member of one of the old families that could link their origin to the very beginning of the city) was a basic requirement to enter politics, having an illustrious name was not sufficient to gain political office. Merit was equally important, as indicated by the long list of offices, called the cursus honorum, that one had to perform before being eligible for the prestigious position of consul, which included executive and military powers. The cursus honorum comprised ten years of military service, plus an ascending series of posts: quaestor (an administrative job), aedile (appointed to review and control public works and the organization of games and festivals), censor (assigned to monitor the honorable behavior of the citizens, including their duty to pay taxes and serve in the military), praetor (which involved a judicial post), and finally consul.

To forestall any excessive accumulation of power, each consul, besides having a term limit of one year, could enforce a veto with which, if needed, he could block or overturn the decision of the other. That rule was modifiable only in moments of particular danger when, with the approval of the Senate, extraordinary military powers were granted to a single individual (a temporary yet absolute dictatorial authority called imperium) that were to be revoked immediately after the crisis ended.

The Senate, which initially included three hundred members, directly evolved from the council of elders that had once advised the king, as explicitly indicated by the word “senator,” which originated from senior, meaning “elder.” Eventually, the Senate became the most important organ of government: it was the Senate that controlled the election of the magistrates, monitored the finances of the state, set the course of foreign policy, and had the last word in the passing of laws.

The high esteem that senators enjoyed was based on the assumption that only noble, rich, and therefore educated and vastly experienced people possessed the necessary wisdom to deal with public and political matters in a way unmarred by the petty trappings of personal and private ambitions. For that reason, all senators were expected to maintain exemplary conduct, respectful of the ideals of honesty, loyalty, frugality, and modesty that constituted the ethos of the republic.

The superior role that the patricians, as representatives of the oldest landed families, maintained over the lower classes, the plebeians, exemplified the patriarchal structure of Roman society. The patricians were respected because they were seen as father figures of the nation (the word “patrician” derives from pater, meaning “father”): wise and learned individuals committed like no one else to the success and prosperity of the nation. Once again, at the center of that mentality rested the old faith in reason: the aristocrats could exercise greater political power because they were considered more rational than those who, lacking status and education, were more likely to fall prey to irrational impulses and passions.

The fact that political positions were not compensated further assured that only the rich patricians, who benefited from the wealth produced by their vast estates, had the time and financial means necessary to compete for governmental offices. The aristocrats’ monopoly over religious and priestly functions further implied that their authority enjoyed the approval and blessings of the gods. The highest religious office was that of the pontifex maximus, who made sure that the gods were respected and that they were kept content through propitiatory rituals performed on behalf of the state. To interpret the moods and wishes of the heavenly regents, the pontifex maximus studied revelatory signs, such as the flight of birds or the entrails of a sacrificed animal. The vestal virgins, who were under the control of the pontifex maximus, were young, unmarried priestesses assigned to different rituals, among which was the tending of the perennial fire that symbolized the very survival of the state. If a vestal virgin betrayed the oath of chastity, she was condemned to die by being buried alive.

The respect that surrounded the patricians was symbolized by the outfit of the senators, consisting of a white toga decorated with a single purple band meant to express the moral purity that those individuals were believed to embody—a concept that is still traceable today in the word “candidate” (from candidus, meaning “candid”), which evokes the stain-free honesty and integrity that, allegedly, characterizes all those who hold public and political positions. Until the nineteenth century, statesmen and politicians, both in Europe and in America, were very often depicted, in sculptures and paintings, wearing Roman togas, as a symbol of the gravitas and moral excellence that distinguished them.

To illustrate the noble civility that had pervaded the early republican years, many exemplary stories were invoked. One of the most memorable involved the patrician Cincinnatus (519–430 B.C.), who promptly responded to the request of the Roman Senate to put aside the plow with which he was working his land to assume the imperium—the absolute military authority he was granted to combat the incoming threat of a neighboring population. As soon as victory was achieved, Cincinnatus, a model of integrity and modesty, didn’t hesitate to renounce the power with which he had been invested to return to the simple anonymity of his previous existence. Cincinnatus’s refusal to take advantage of his position and his willingness to relinquish fame and adulation in favor of the humble yet authentic dignity that tradition assigned to the cultivation of one’s ancestral lot catapulted his legacy into the firmament of the republic’s most admired and beloved heroes. A statue of Cincinnatus, in the Ohio city of Cincinnati that bears his name, shows the Roman leader returning the fasces to the Senate (the fasces being the bundle of rods that had initially symbolized the power of the king and then represented the briefly held dictatorship of the imperium), while the other hand holds the plow with which he is about to resume his old work. In that simple gesture, the essence of the republican spirit was strongly conveyed: without the exemplary patriotism of people like Cincinnatus, willing to place the interest of the community above self, Rome would never have become the ruler of the world and, most important, the greatest example of human civilization.

A statue of Cincinnatus, who epitomized the selfless virtues of the early Roman Republic, in his namesake city of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Americans, steeped in Roman history and mythos, applied the example of Cincinnatus to the “father of our country,” George Washington.

The story of Cincinnatus gained popularity with the American Revolution, when George Washington, like the Roman hero, having fulfilled his duty on behalf of the country, humbly returned to the cultivation of his land in Virginia. The parallel between Washington and Cincinnatus was also stressed to praise the virtuous simplicity of the Americans in contrast with the pretentiousness of the British oppressors.

Ennobling stories like that of Cincinnatus represented, for the Romans, the embodiment of what they called the mos maiorum: the “old ways” through which the forefathers had expressed their unconditional devotion to family and state. For the Romans, who did not possess a written constitution, the mos maiorum represented a fundamental point of reference: an unwritten code of conduct upon which were based the civic and moral norms that animated the republican system. The connection between mos and “morality” still evokes the moral value that the past associated with tradition.

In time, the aristocrats’ greatest challenge came from the entrepreneurial class, called the equites (the name equites had originally indicated those who could afford a horse to go to war). This class had amassed substantial wealth through trade, an activity that the senators were forbidden, by law, to engage in, because commerce was believed to be a breeding ground for vulgar and selfish pursuits incompatible with the high moral standards that the nobility was expected to possess. The prejudice ended up hurting the aristocracy in unforeseen ways. When the pressure from the ever more rich equites could no longer be ignored, the blue-blooded elite were forced to accept those nouveaux riches as political equals within the government of the city. The term optimates included all those who belonged to that new and extended definition of the upper class.

More problematic was the situation of the commoners, or plebeians, who were denied access to relevant political positions. The problem was exacerbated by Rome’s military organization, which was based on the physical and financial contribution of all the citizens of Rome. The system’s inequity was evident: the aristocrats who could afford the best weapons and armor assumed commanding posts, while the small farmers and artisans filled the less prestigious ranks of foot soldiers. The heavy demand placed on the lower ranks, coupled with the risk of being reduced to a serf’s condition if one incurred a debt that could not be repaid (which was often the case, especially when, to serve the country at war, a farmer was forced to leave his land unattended for many months at a time), pushed the situation to an inevitable rupture point. In 494 B.C., the plebeian population, exasperated by the abuses of the upper class, seceded by withdrawing to a hill near Rome. The threat of having the army depleted of its soldiers forced the nobles to grant two important concessions: the institution of two tribunes of the plebs to protect the interests of ordinary citizens and the issuing of the Twelve Tables that represented the first written code of Roman law concerning basic legal rights.

Although the exact content of the Twelve Tables is unknown because only a few fragments have survived, scholars agree that the document represented an important first step toward Rome’s most important contributions—the development of law and the establishment of civil rights. Those rights, which along with familial regulations and juridical issues were essentially aimed at the protection of private property, should not be confused with our modern concept of universal rights based on the moral recognition that there is no difference of worth between human beings. This egalitarian concept took two more millennia to be formulated.

As we have seen, finding an ideal form of government had been an issue of central importance for the Greeks. But all the political systems they had conceived had proven problematic, Athens’s democracy included. Reflecting on the issue, Cicero claimed that the only ones who had come up with a truly durable solution were the early Romans, whose republican system, being a mix of different forms of government, had been able to balance, in harmonic equilibrium, the interests of the various social classes. Cicero’s view derived from the Greek historian Polybius (203–121 B.C.), who had described the Roman Republic as an ideal constitution formed by the perfect blend of three forms of government: monarchy (as represented by the consuls), aristocracy (senate), and democracy (popular assemblies).

For thinkers like Polybius and Cicero, the most important aspect of Rome’s mixed constitution consisted of its capacity to prevent the monarchical tyranny of one, the oligarchic tyranny of few (essentially formed by the wealthy elite), and the tyranny of many, which, in their view, democracy, as the rule of an uneducated, excitable, and often irrational mob, represented.*1

Despite the praise it received, the concordia ordinum, meaning the peaceful collaboration between the different social strata that Cicero attributed to the republic, appears more an ideal than a reality, particularly when we consider the dissatisfaction of the lower classes, whose repeated attempts to gain greater rights were regularly thwarted by the maneuvering of the rich, who always managed to keep the system slanted in their favor.

This endemic disparity among citizens gives the Roman Republic a connotation that, ultimately, is very different from our contemporary understanding. Today the terms “republic” and “democracy” are nearly interchangeable. The same thing cannot be said about the Roman Republic: a system that was based not on the absolute equality of all people but on the different privileges that wealth and gender conferred. (Even if women were called citizens, they were considered inferior to men and denied an equal status within society.) A radical disparity also existed among men: even if liberty was assured to all citizens, having a share in the government of the city was not the same for all, in that political participation varied according to the class to which, by birth, each individual belonged.

The underlining assumption, which Cicero shared with Aristotle, was that natural justice meant not universal equality but a proportionate equality. “Proportionate equality,” writes Neal Wood in Cicero’s Social and Political Thought, “occurs in a state where citizens are divided by worth (dignitas) from the lowest to the highest into a hierarchy of legal orders. Each citizen belongs to a distinct station or rank (status) in the hierarchy.” Institutionalized within the mixed constitution of the Roman Republic, that difference of status was consistently used to favor “the privileged few to the detriment of the underprivileged majority.” Birth and wealth gave greater worth to the individual by making him naturally superior to those who, lacking money or property, could only contribute to society by breeding children, as the meaning of the word proletarius suggests (proles means “offspring” in Latin).

In that sense, contrary to what the symbol SPQR, meaning Senatus Populusque Romanus, or “the Senate and the people of Rome,” seems to suggest, the people who truly mattered within the Roman Republic were a restricted oligarchy of men belonging to the old nobility and the rich equites. Within that context, a less affluent plebeian would seldom have reached the top of the political ladder. A plebeian who managed to succeed was given the title of novus homo, meaning “new man” (Cicero, who after being quaestor, aedile, and praetor was granted consulship for the year 63 B.C., was called a novus homo, which meant that none of his ancestors had ever held any political office before).

From its beginning, Rome distinguished itself by the strength of its military. Except for the setback it received from the northern Gauls, who attacked the city in 390 B.C., Rome from the fourth century B.C. on enjoyed a long series of victories that assured its quick expansion throughout the Italian peninsula. A new phase occurred when the city turned its predatory interest toward the rich and powerful North African city of Carthage that had dominated the Mediterranean basin since the eighth century B.C. The term “Punic Wars,” referring to the one hundred years of military engagement between Rome and Carthage, evokes the Phoenician origin of the African city (punicus was the Latin word for “Phoenician”). The first war against Carthage, which lasted twenty years, gave Rome control over Sicily, to which was later added Sardinia and Corsica (all territories previously belonging to the African city). Less favorable was the Second Punic War, in which Rome suffered a devastating defeat in Cannae, in southern Italy (216 B.C.). The Carthaginian general who inflicted such a humiliating blow to the Roman legions was Hannibal, who famously entered Italy by crossing the Alps with fifty thousand troops and forty elephants. It took the brilliant leadership of the Roman general Scipio Africanus to avenge the humiliating defeat of Cannae with the decisive victory of Zama in 202 B.C. Rome’s supremacy over the Mediterranean was completed in 146 B.C., when it finally crushed and razed to the ground its legendary enemy. The Roman ritual that followed, which consisted in sowing salt in the enemy’s land, symbolically denied any future growth to the city that the Romans had condemned to death. The vehement demand delivered by one of Rome’s most stern statesmen, Cato the Elder (234–149 B.C.), “delenda est Carthago” (Carthage must be destroyed), has remained emblematic of the ruthless attitude that Rome maintained toward its fierce adversary.

With the threat of Carthage removed, Rome’s centrifugal power became literally unstoppable. Within a few years, its orbit of influence grew to include, next to the parts of the Iberian Peninsula that had previously belonged to Carthage, all of North Africa. Subsequently, Rome conquered Macedonia in 148 B.C. and, by 133 B.C., all the rest of the Greek territories. The many other countries that one by one were taken over by Rome included Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Persia, and part of what is today Pakistan, as well as the Levantine countries of modern Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine.

Military power created the Roman Empire, but that power would not have survived without the extraordinary political and administrative skills with which the Romans organized the gigantic expanse of their dominion. Governors and military officials, who were deployed in the various provinces, assured peace as well as the political and administrative cohesion of the empire, while tax collectors gathered the money needed to sustain that complex organization.

Rome’s ascent to power had indeed been spectacular, but that success didn’t come without challenges and complications. The most dramatic came from the impoverished small farmers who, after shouldering the military burden, ended up outnumbered by the legions of slaves, captured in war, whose work was now exploited in the immense stretches of land (the latifundia) controlled by the ever-richer upper class. As a consequence, Roman society became increasingly polarized, with the rich shamelessly exploiting their position of power while the disenfranchised farmers, unable to overcome the competition of the latifundia, sold or abandoned their lots to join the ranks of the dispossessed (to which also many immigrants from the conquered lands belonged) who had begun to occupy the urban environment. The situation gave way to a populist movement led by the Gracchus brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, who, on behalf of the populares, demanded a general redistribution of the land to alleviate the desperate condition into which so many had fallen.

Galvanized by the violent deaths of the two Gracchus brothers, the populist movement gained a major victory in 107 B.C., when a general named Marius introduced a new method of military recruitment. Because small farmers had become so scarce, Marius enticed landless people to fill the ranks of the army by joining as volunteers. Besides being provided with training and weapons, these volunteer soldiers were given the assurance of a bonus of land to be received at the end of their deployment. The appeal of Marius’s reform was enormous, but so were the unexpected consequences that occurred when the troops, having become more loyal to their generals than to the nation, allowed their leaders to prolong their imperium in open defiance of the authority of the Senate.

The situation degenerated when a number of generals, who had amassed wealth through war plunder and looting, started to compete with one another, showering with gifts and favors their soldiers and supporters with the intention of increasing their influence in Rome’s political world.

The enormous enthusiasm that surrounded a winning general was displayed in the triumphs: the boisterous processions that took place at the end of a victorious campaign, which were architecturally commemorated with triumphal arches placed at different points of entrance to the city. With the consent of the Senate, a general who had killed at least five thousand enemies could request the privilege of parading his troops beyond the sacred limit, or pomerium, of the city (a general who could not claim the same amount of enemy deaths only received an ovation, meaning a smaller celebration in which only ovis, or “sheep,” were sacrificed). While the proud soldiers displayed the war booty and the prisoners of war to the cheering crowds, the general, crowned with a laurel wreath, stood on a chariot pompously accepting the adulation of the public, whom he made sure to please with the dispensation of generous gifts meant to show the largesse of his noble spirit. The twelve lictors, who preceded the triumph, carried the bundle of rods called fasces (from which Mussolini derived the term “fascism”) that symbolized the general’s power to dispense life and death.

The red paint that covered the general’s face was meant to evoke the vitality of Jupiter, the most powerful of the gods. The detail is important because, just as with the classical Greek heroes, the aura surrounding the winner elevated him to godlike status. But that display of pride was not allowed to go on forever: when the procession reached the temple of Jupiter, the general removed his laurel crown and placed it at the feet of the god’s statue. That act of submission was reinforced by the presence of a slave who, throughout the ceremony, kept whispering in the general’s ear, “Remember that you are only a mortal man.” The warning was meant to curtail any possible burst of hubris: though praised as a god, the general had to remember that his triumph would last only one day.

One of the most memorable triumphs took place when the general Lucius Aemilius Paullus returned home from the victorious campaign in Macedonia (168 B.C.), which marked the end of the hegemonic power of the Greeks in the eastern part of the Mediterranean. The biographer Plutarch, in his Life of Aemilius Paullus, describes the great crowd who came to witness the event. To welcome the returning troops, all temples were open; garlands of flowers filled the air with colors and perfume, while trumpeters accompanied 250 wagons full of looted statues and paintings. Right behind them came more wagons filled with armor, helmets, shields, swords—all the gold, silver, and bronze that belonged to the defeated warriors. Among the many captives led in shackles through the Roman crowds was the humiliated king of Macedon. To describe the shocked expression of the Macedonian king, Plutarch wrote that he appeared “deprived of reason” because of “the greatness of his misfortunes.”

The snobbish disdain that the Romans expressed vis-à-vis the Greeks appears much less convincing when one considers the extraordinary gift of culture that the captives provided to the winners. When they initially made their appearance on the stage of history, the Romans proved to possess courage, endurance, and discipline—qualities characteristic of strong yet rugged soldiers who had neither the talent nor the inclination for higher intellectual pursuits. Things drastically changed when, having conquered the Hellenistic world, the predatory instinct of Rome was unexpectedly transformed by the cultural richness of its prey. As the poet Horace (65–8 B.C.) famously stated, “Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit,” which means “when Greece was taken she enslaved her rough conqueror.”

Greek influence had initially filtered into Rome through the neighboring Etruscans, who had come in contact with the colonies established by the Greeks in the southern part of the peninsula and on the island of Sicily. But that initial rivulet was transformed into a full inundation when the Hellenistic world, in the second century B.C., fell under Roman domination. “For it was no tiny stream that flowed into this city from Greece, but rather a rich flood of moral and artistic teaching,” as Cicero stated in his Republic.

Cicero was right: whatever Rome produced from 200 B.C. onward contained, at its deepest core, a fertile fragment of Greek genius and creativity. In that vast process of assimilation, religion also became a mix of Greek and Roman gods: Zeus came to be identified with Jupiter, Athena with Minerva, Aphrodite with Venus, Dionysus with Bacchus, and so on.

Besides religion, the Romans drew heavily from Greek philosophy, which, through their pragmatic approach, became an exploration of how to translate abstract notions, like the Platonic ideals of Justice, Beauty, and Good, into actual rules and laws. Commenting on the difference between the Greeks and the Romans, Edith Hamilton, in her book The Roman Way, correctly concludes, “The Greeks theorized; the Romans translated their theories into action.”

But the Greek cultural input was not appreciated by all. Cato the Elder, the famous senator, consul, and censor whom Cicero called “the prince of all virtues,” relentlessly scorned the Greeks, whom he considered a wretched, frivolous, and ostentatious people, in love with nudity as well as abstract and useless mental exercises. By sinking too deep in the quicksand of those decadent characteristics, Cato maintained, Rome’s discipline and virtue would dissolve with devastating consequences for the future of the city.

In a letter addressed to his son, Cato wrote, “In due course, my son Marcus, I shall explain what I found out in Athens about these Greeks, and demonstrate what advantage there may be in looking into their writings (while not taking them too seriously). They are a worthless and unruly tribe. Take this as a prophecy: when those folk give us their writings they will corrupt everything.”

More than anything else, Cato’s burning indignation was aimed at the feminine qualities that, in his view, characterized the Greeks, who were known for their love of beauty and their sexual freedom. What Cato was trying to insinuate was that an excessive exposure to Greek taste and mentality would have potentially sapped what had been the Romans’ most precious characteristic—their legendary manliness.

Those negative views were mostly influenced by the changes that Greek culture underwent once Alexander’s conquest gave way to the Hellenistic experience. Alexander, as we have seen, was a great admirer of Greek tradition and values. He venerated Homer and liked to think of himself as a new Achilles. But as his military successes grew, his young mind failed to retain the lesson of humility imparted by his beloved Homer. As a consequence, Alexander, violating the rule of moderation that the Greeks respected more than anything else, assumed absolute power, claiming that he possessed a divine nature.

Emulating Alexander’s indulgence in pompousness and grandeur, all the Hellenistic monarchs who followed him openly betrayed the old classical ethos of measure and restraint to engage in rich and ostentatious habits. It was mainly from the example set by Ptolemy, Alexander’s general who was given control of Egypt and who established a pharaoh-like cult of himself, that the Romans derived their view of the Greeks as irrational, decadent, and “effeminate” lovers of all sorts of extravagant excesses. As we will see, the prejudice substantially grew when the Egyptian queen Cleopatra appeared on the stage of Roman history as the lover of two famous Roman generals, Julius Caesar and Marc Antony.

For the austere, Spartan-like mentality that had characterized the early Romans, nothing could be worse: if man’s mental and physical hardiness was to be sapped by decadence and luxury, mighty Rome would certainly crumble and fade away.

Despite the alarm of moralists like Cato, the fascination that Greek culture, style, and taste exercised on the Roman mind appeared as magnetic and irresistible as a lunar tide upon the ocean. The cultural fusion that ensued was facilitated by the presence of many Greeks brought to Rome as slaves. Some were used for humble works, but many, especially those who possessed cultural and/or creative talents, were placed in very respectful positions, such as tutors hired by the rich to educate their children.

It is in this period that many Romans, enriched by the wealth that poured into the city from all the corners of its sprawling empire, started to violate the traditional norms of acceptable behavior, taking time away from public life to pursue personal and private affairs. The most glaring symbols of that new trend were the grand villas that the members of the upper classes built in the countryside outside what had once been the inviolable boundary of the city. The relation between the life of leisure enjoyed in the villa and the life of duty carried on in the city was epitomized in the concepts of otium and negotium. The villa was the place where the individual, through his otium, or “time of leisure,” could express his private and individual interest apart from the negotium, or “time of duty,” that the city demanded. The contrast with the past was dramatic: the individual, who had once perceived his identity as indivisible from the state, was now emerging as a private entity interested in personal and private matters that were often completely at odds with the larger concerns of society.

The pursuit of luxury that the early generations had so vehemently condemned soon became the most tangible proof of that change in mentality, as shown in the large and elegant villas that began to mushroom throughout the Italian territory. Everything in those opulent and fancy mansions exuded the flavor of Greek style and fashion: from the central, open courtyard called the atrium, to the porticoes and loggias decorated with long rows of beautiful marble pillars, to the interiors filled with a great amount of costly objects and furniture inlaid with gold, silver, and ivory. To be recognized as someone of stature within society, a person would dispense a tremendous quantity of money. The demand for silks, linens, jewels, perfumes, and cosmetics soared among rich women, while their men offered elegant dinner parties put together by chefs hired from different parts of the empire. Among the most extravagant culinary delicacies were boars’ heads, sows’ udders, peacock roasts, donkey stew, and a great variety of songbirds.

Because everything Greek was considered elegant and refined and because the wealthy were eager to show the sophistication of their taste, a dramatic increase in the import of art occurred. When the spoils of war became insufficient to match the vast demand, legions of talented Greek slaves were brought to Rome to adorn the showy abodes of the rich. Thousands of Greek-looking sculptures were manufactured (which, in many cases, were copies of famous classical or Hellenistic models), as well as frescoes made with a great variety of vivid pigments. The themes of those frescoes were various: some consisted of mythical and allegorical decorations evocative of Greek practices and beliefs; others depicted idyllic landscapes in which the boundary of the ordinary dissolved in fantastic visions full of dreamy and fairy-tale magic.

Sensual and even erotic overtones were frequent, especially in the matrimonial room where the procreative power belonging to the genius of the paterfamilias was believed to reside. The word domus, which in Latin means “house,” also evoked the uncontested dominium of the paterfamilias, whose rule, as in the Greek tradition, was deemed absolute within the family.

The names given to the rooms of the villas stressed the admiration accorded to everything Greek: the lyceum was the place where books were collected adjacent to busts of poets, philosophers, and orators; the pinacotheca was the area dedicated to the family art collection; the triclinium indicated the dining space, which was often guarded by a statue of Dionysus; the lararium was the space dedicated to the household gods.

The elaborate and colorful frescoes in the cubiculum, or “bedroom,” in the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

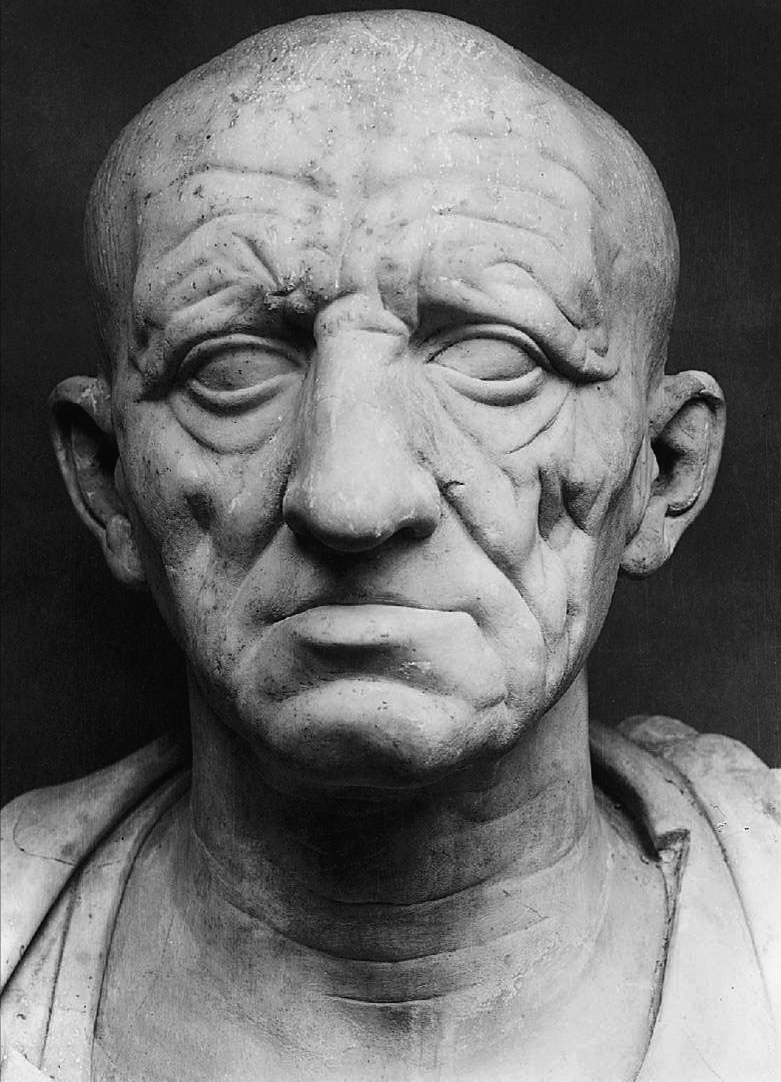

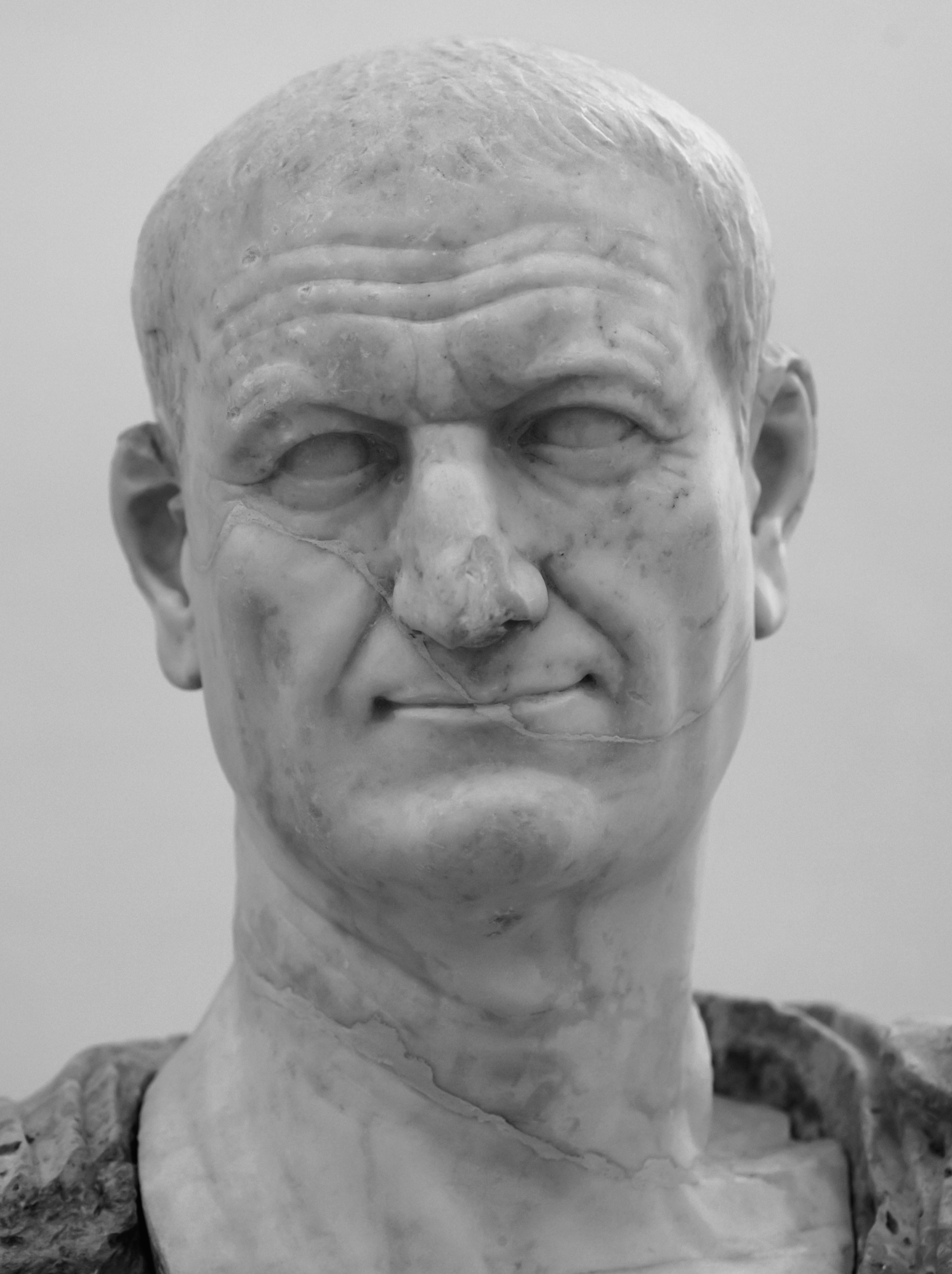

To prove their worth, many rich magnates got into the habit of ordering sculptural portraits of themselves: some of these effigies were displayed in private homes; others were reserved for the grand funerary mausoleums that every respectable family possessed. The famous realism of Roman art owes a lot to the vanity of those rich, pretentious people. Young, old, fat, thin, beautiful, ugly, toothless, wrinkly, bald: besides a dignified air of Roman gravitas, what those rich Romans demanded from the artists were effigies that could be immediately recognized by the circle of friends whom they were trying so hard to impress.

Initially, the art of portraiture had been limited only to the cult of the ancestors whose wax masks were kept at the entrance of private homes. The right to possess such masks only belonged to those who had attained at least one position of relevance within the Roman state. The funeral procession of a notable individual was accompanied by actors wearing the masks of his ancestors, of whom they repeated the most famous sayings.

Within the ever more frivolous atmosphere that began to dominate the later years of the republic, busts and portraits of the rich became a commonplace even among the living. Some wealthy sponsors, overcoming the initial adversity toward Greek nudity, went as far as ordering unclothed representations of themselves. The muscular nakedness of lawyers and officials boasting a perfectly idealized body was meant to be reminiscent of the heroic ideal of Greek classical times.

Politics was not spared this new kind of open and blunt ambition. Because acquiring prestigious political position had become an obsession among the rich families, bribery, corruption, and intrigue became the rule of the day in the capital of the empire. Commenting on the poisonous effect that money had on his fellow countrymen, Cicero sadly concluded that in Rome everything was “for sale.”

When Rome was still a relatively small city-state, the authority of the senate had been sufficient to assure the functioning of government. However, as the city grew to become the head of a huge and rich empire, the senate lost much of its capacity to maintain unity within a much larger society, increasingly vexed by the contrasting interests of different classes and competing political factions. Instability allowed the rise of several strongmen who shrewdly exploited the chaos to gain political influence. After Sulla, who appointed himself dictator, and Catiline, who tried to overthrow the republic, came the alliance of three prominent military commanders known as the First Triumvirate (60 B.C.).

Roman sculptural effigies tended far more toward realism than idealism. Credit 2

The men who formed the First Triumvirate were the vastly ambitious Julius Caesar, the immensely rich Crassus (who died prematurely fighting the Parthians), and the powerful Pompey, who had acquired great prestige during his campaigns in Spain, Syria, and Palestine, as well as in the Mediterranean, where he freed the sea from the raids of marauding pirates. Initially, the starring role was held by Pompey, who, after his conquests in Africa, was awarded the title of Magnus, just like Alexander the Great. To suggest that Pompey was a Roman version of Alexander, his sculptural portraits were given the same leonine hairstyle that Alexander had sported (as in the marble busts produced in the fourth century by the sculptor Lysippus shown above). The enormous prestige that the detail conferred is almost impossible for us to comprehend: those curls parted in the middle to frame the face like the mane of a lion represented not just a style but the mark of destiny of a man whom many considered the deserving successor of Alexander the Great.

The hairstyle of Pompey in this bust consciously matches that of Alexander the Great—a mark of destiny.

Among the many acts that had turned Pompey into a darling of the Roman people was the gift of an enormous theater—the first built in stone rather than wood. To make sure that the Romans would never forget his legacy and generosity, Pompey placed an imposing statue of himself at the entrance of the theater, surrounded by other statues that personified the various nations that he had subdued for the benefit of Rome.

Although great, Pompey’s reputation was soon overshadowed by that of Caesar, who, having become governor of northern Italy and southern France, led his troops into Gaul (modern France) to conquer, on behalf of Rome, a territory that was two times the size of Italy. The conquest, which pushed the Roman boundaries up to the English Channel, marked a historical turning point: not only for the stunning victory over the fierce Gallic tribes, but also because, from then on, the center of gravity of the empire was forever switched from the Mediterranean to continental Europe. (Britain, which Caesar was the first to invade, was annexed to the empire only one hundred years later during the reign of the emperor Claudius.)

During the Gallic campaigns, Caesar had consistently maintained that the only thing that truly mattered for him was the success of Rome, but the senate remained suspicious about his true intentions. The mistrust was well placed: as a response to the senate that had ordered him to disband his troops before reaching Rome, Caesar in 49 B.C. defiantly crossed the Rubicon, the small stream that marked the southern border of his provincial command. A state of emergency was immediately declared. Pompey, asked by the senate to mount a counterattack, went to Greece to gather more manpower. The clash between Pompey and Caesar—the two enormously successful and egotistical generals who had long aspired to become the sole masters of Rome—culminated in Pharsalus in 48 B.C. with the victory of Caesar. Pompey, who was able to flee, sought refuge in Alexandria, where the young pharaoh Ptolemy XIII, who was only thirteen years old, reigned with his sister-wife Cleopatra (marriage between siblings was customary among Egyptian rulers).

The pharaoh’s promise to protect Pompey was suddenly broken when, to please Caesar so that Rome, in return, could recognize Egypt as an ally, Ptolemy had Pompey killed and beheaded. To the pharaoh’s great surprise, Caesar’s reaction ran exactly contrary to his expectation: furious that a foreign leader had dared to kill a Roman general, Caesar immediately seized control of Egypt. Cleopatra, who aspired to get rid of her younger brother, turned the situation to her favor when she became Caesar’s mistress and eventually gave him a child by the name of Caesarion. After Ptolemy died by drowning in the Battle of the Nile, Cleopatra became the sole leader of her country.*2

When he returned to Rome, Caesar, emboldened by his amazing victories, violated the fundamental rule of the republic by electing himself supreme commander of the army and dictator for life. The triumph he sponsored to celebrate his campaign was a powerful propagandistic tool: the civil disorder that for so long had divided Rome would come to an end, Caesar’s triumphal festivities implied, only if a strong leader took control of the nation.

The ability with which Caesar trampled down the opposition and the mischievous machinations he used to gain the respect of the public speak volumes about his charisma and his political cunning. Pondering the amazing ability of a man who could sway legions to his side as easily as he tamed his curls back to hide his receding hairline, Plutarch, evoking Cicero’s thoughts, wrote, “When I see his hair so carefully arranged and observe him adjusting it with one finger, I cannot imagine it should enter such a man’s thoughts to subvert the Roman state.”

As soon as he assumed control of Rome, Caesar started a program of social and political reforms, which also included the creation of the Julian calendar—a solar calendar made of 365 days that replaced the old lunar calendar. (The Julian calendar was replaced in 1582 by the Gregorian calendar, from Pope Gregory XIII, which is still in use today.) The month of July was named after Julius Caesar, who was born in that month. Later, the month of August took its name from Augustus.

The first thing that Caesar did to solidify his position was to envelop his authority with the same mythical aura typical of Eastern leaders. With that purpose in mind, Caesar, in a way that was evocative of Alexander’s style, started to insinuate that his leadership directly derived from the gods, who had chosen in him a leader worthy of Rome’s legendary destiny. From then on, his image began to appear on coins—an honor that, previously, had been assigned only to the gods.

One of the most symbolic acts with which Caesar sanctioned his newly acquired power was the construction of a new forum, placed right next to the one that since the beginning of Rome had been the only commercial, administrative, or religious center of the city. The main temple that Caesar built in his Forum was the one dedicated to Venus, the goddess from whom he claimed to directly descend. It was reported that, shortly before his assassination, Caesar asked the Senate to meet him in front of the temple of Venus Genetrix (Venus Mother). When the venerable assembly approached him, Caesar, with insolent truculence, remained seated, refusing to stand up as tradition prescribed—an incredible act of defiance toward the sanctity of a political entity that for centuries had enjoyed an undisputed respect among all the citizens of Rome.

It all ended in 44 B.C. when a group of conspirators, led by Brutus and Cassius, killed Caesar in the name of the libertas that the city had lost when his dictatorship brought to an end the republic. Despite their intentions, the conspirators’ action did not provoke its intended consequences. Describing the funerary pyre that consumed Caesar’s mortal body, the art historian Georgina Masson observes, “In that fire the Republic perished and Caesar emerged from it as something more than human. A column was erected on the spot, the first monument to a mortal man to be built within the sacred precincts of the Forum; during Augustus’s reign Caesar’s altar and temple replaced the column and he was officially deified.”

During the games held as funerary tributes to Julius Caesar, a comet appeared in the sky for seven days. The comet was interpreted as a prodigious proof that Caesar had reached the heavens, where he was now residing among the immortal gods. From then on, the iconography concerning Caesar almost always included the star (the Sidus Iulium) that had announced his deification.

AUGUSTUS AND THE EMPIRE:

THE THEATER OF POLITICS AND POWER

The next thirteen years witnessed the conflict between Marc Antony, who had once been Caesar’s friend and protégé, and the young Octavian, Caesar’s grandnephew, both wrestling to be recognized as the legitimate heir of the murdered dictator. Initially, the two men had established a triumvirate that also included Lepidus. The first act of this Second Triumvirate was to go after the conspirators who had murdered Caesar. That mission was accomplished when Brutus and Cassius, defeated in the Battle of Philippi in 42 B.C., committed suicide. With the excuse of avenging Caesar, a vast campaign of repression was begun. In the bloodshed, at least three hundred senators found a violent death as well as two thousand equestrians. Among the victims was Cicero, who had branded Antony an enemy of the state. As a trophy and a warning to all others who would have dared to oppose him, Antony ordered his men to expose in the Forum the decapitated head and cutoff hands of Cicero—a brutal end to the most eloquent voice speaking in defense of the republic.

In the following years, the two main members of the Second Triumvirate (Lepidus having been pushed aside) divided the empire between themselves: Octavian took control of the West, Marc Antony of the East. Plutarch describes the festivities that Marc Antony received upon his arrival in Ephesus (in today’s modern Turkey), when he was honored as Dionysus. Women welcomed him dressed as bacchantes, while men and boys dressed as satyrs and fauns danced to the music of harps and flutes. The pompous way in which Eastern leaders were worshipped immediately seduced Marc Antony. The coup de grâce occurred when he met the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. The theatrical way with which Cleopatra staged her arrival, when she officially came to meet Marc Antony, is described with these words by Plutarch: “She came sailing the river Cydnus, in a barge with gilded stern and outspread sails of purple, while oars of silver beat time to the music of flutes and fifes and harps. She herself lay all along, under a canopy of cloth of gold, dressed as Venus in a picture, and beautiful young boys, like painted Cupids, stood on each side to fan her. Her maids were dressed like Sea Nymphs….The perfumes diffused themselves from the vessel to the shore.”

Captivated by that mesmerizing sight, Marc Antony immediately fell in love with Cleopatra. As soon as the news of the love affair reached Rome, Octavian began to rally the people against him. Marc Antony, Octavian said, not only had abandoned his Roman wife, Fulvia, for the sensual Egyptian queen but also was now flamboyantly equating himself with Dionysus while his mistress acted like the personification of Isis. The thought of a Roman general corrupted and rendered “effeminate” by the witchlike powers of a promiscuous Eastern queen left the Romans dumbfounded and horrified. Disbelief was replaced by outright anger when alarming rumors spread the news that Marc Antony was planning to hand Rome to Cleopatra and move the Roman government to Alexandria. The fear that the two lovers were plotting a coup d’état sparked a conflict. Octavian, who was put in charge of the mission, swiftly confronted and defeated the two lovers and their army at Actium in 31 B.C. Both Marc Antony and Cleopatra avoided the humiliation of being dragged along the streets of Rome as traitors and prisoners by committing suicide.

The grandiose triumph that followed Octavian/Augustus’s victorious campaigns lasted for three uninterrupted days—a record never enjoyed by any other general before. The excitement produced by the lavish festivities electrified the crowds, who were treated with lots of free food and wine and a great variety of athletic events. The most cherished ones were chariot races and animal hunts, which were made particularly thrilling by the presence of many exotic species brought to Rome from different parts of the empire, such as tigers, lions, rhinoceroses, and hippopotamuses that were carelessly slaughtered to please the bloodthirsty frenzy of the Roman people. To further enhance his public image, Augustus also awarded land to his soldiers and generously distributed gifts and money to the citizens of Rome.

To avoid the accusation of impropriety, Augustus also made sure to promptly disband his troops before entering the city. His subtle calculation was to act as if, after valiantly defending the reputation of Rome, he was now going to surrender all powers and, like a humble Cincinnatus, retire to private life. Augustus, of course, knew perfectly well that an act of abdication on his part was never going to be accepted. He was right: because everybody feared that without a strongman the city would immediately relapse into civic unrest, the Senate begged Augustus to renew his consulship. With his usual flair for showmanship, Augustus initially displayed hesitation and reluctance but then graciously accepted the Senate’s offer as if to prove that nothing, not even the prospect of a peaceful retirement, mattered more to him than the safety and well-being of the state. The extension that the Senate offered each time the appointment elapsed allowed the gradual yet inevitable rise of Octavian/Augustus to the pinnacle of power.

Even though he was directly responsible for his dictatorial consolidation of power, Augustus, with strategic acumen, always managed to appear in keeping with the rules of the republic. Unlike his brusque, impatient, and less politically astute great-uncle, he prudently morphed into a dictator without ruffling any feathers: in other words, without ever losing the mark of legitimacy, despite the illegitimate quality of his acts. Augustus’s brilliance was to understand that even though the Senate had become practically insignificant, the too-obvious gathering of power in the hands of a single man would have rubbed the wrong way the antimonarchical feelings that the Romans had fiercely cultivated since the beginning of their history. For that reason, Augustus chose to disguise his real intentions behind the benign mask of savior and protector, instead of usurper, of the old republic, whose power, he proclaimed, he was determined to restore and revive.

The complacency with which people went along can easily be understood: as the exhausted citizens of Rome, tired of so many years of external and internal conflicts, chose to transfer onto the emperor the responsibility of the now-immense empire, the grateful emperor returned the favor by assuaging the bad consciences of his fellow citizens by using the unthreatening term of principate to describe his imperial rule (the full title was princeps senatus, “first among senators”). By pretending that he was not an absolute monarch but just the leader of the Senate, the emperor gave his fellow citizens the excuse they needed to convince themselves that they were still free agents of a free and self-determined society. Within that fictional narrative, Augustus’s role became that of an illuminated leader: a princeps who, by governing in collaboration with the institutions of the state, led a government that was a further elaboration rather than a subversion of the old republican system. The complaisant senators continued to debate, the magistrates to deliberate, but behind the artifice the unspoken truth remained: in all political matters, the only voice that counted was that of Augustus. The rest was only fiction and travesty: the subtle web of psychological persuasion brilliantly weaved by an ambitious and astute man fully conscious of the power of his political propaganda.

When the grateful Senate attributed to Octavian the title of Augustus, he was shrewd enough to accept it but with a certain amount of reservation, as if to imply that given his humble disposition he would have preferred the title of “first citizen” or, more poignantly, that of pater patriae, meaning “father of the nation.”

Notwithstanding that unassuming attitude, Augustus never missed the opportunity to stress the Olympian origin of his family—an origin that made him, just like Caesar, a direct descendant of Venus. To promote the cult of his persona, Augustus often made references to the deification that Caesar had received after death, which, consequently, made him a direct “son of the divine Julius.”

But that lofty title was also carefully leveled by a populist attitude that favored all the citizens of Rome, independently from the class to which they belonged. In years of food shortages, Augustus provided free grain to the poor while building bridges and an awesome network of roads to facilitate trade and commerce for the benefit of an ever-growing middle class. To mitigate the fear that a shift in favor of the middle class would have erased the last semblance of the old elitist regime, Augustus continued to stage an attitude of deference toward the snobbish aristocrats, knowing full well that the most powerful way to draw them to his side was to continue to shower them with the most irresistible of all trappings: flattery and adulation.

Building on this firm coalition of consent, Augustus introduced many reforms, among them the creation of an imperial army that for the first time was composed of professional soldiers paid in money rather than land. To strengthen the state, Augustus also convinced his followers that to repair the social fabric, a moral reform was imperative. What was needed in order to achieve that goal, Augustus believed, in agreement with authors such as Sallust (86–ca. 35 B.C.), Livy (59 B.C.–A.D. 17), and Cicero, was a revival of the old mos maiorum: the decorum, modesty, gravity, and above all loyalty to civic duty of the old republican years that wealth and competition had so dangerously undermined. To reverse that dangerous trend, Augustus encouraged the Senate to pass laws directed at revamping decency and modesty among the rich and unruly optimates, who were now threatened to be sanctioned for any vulgar and excessive display of wealth. To assure a dignified level of decorum, he imposed the wearing of the toga on all those admitted to the Forum. Augustus also used his power to revive and protect the sanctity of the Roman family, which he tried to turn again into the bastion of discipline it had represented in the early years of the republic. The Julian laws, which he passed in A.D. 17–18, included all sorts of legal consequences for people who failed to get married and have children and also for those who divorced or indulged in adultery, prostitution, and fornication. It must have been a shock and a great embarrassment for Augustus to have to ban from the city his own daughter and granddaughter, both named Julia, and punish them because of their obscene and adulterous sexual practices. It seems that even Ovid (43 B.C.–ca. A.D. 17 or 18), the famous author of the Metamorphoses, was forced into exile for writing the Ars amatoria: a book considered morally inappropriate because it was about the pleasures of love.

To revitalize patriotism, Augustus also decided to invest a lot of money in the aesthetic appearance of the city. To that aim, he invested a great amount of his personal fortune, next to public funds that the city easily drew from the wealth accumulated through commerce and trade—activities that had become particularly vigorous thanks to the immense web of roads that were increasingly linking the lands of the empire.

The reason Augustus worked so hard at improving the appearance of the city derived from his belief that what the citizens needed most was a highly charged visual narrative—a narrative that, in glamorizing the role of Rome as capital of the world, would reignite people’s love for their nation and with it the desire to redirect toward civic purposes their interest, passion, and monetary contributions. Many centuries later, the same concept was spelled out by another famous dictator who greatly admired Augustus, Napoleon, who said, “When you want to arouse enthusiasm in the masses, you must appeal to their eyes.” In other words, dazzle the eyes in order to influence the mind.

The Egyptians, with their imposing architecture and arresting sculptures, had understood that truth very early, as did Pericles, in the fifth century B.C., when he skillfully used art as an essential tool of political propaganda—a choice that ushered in Athens’s Golden Age that Rome, in a similar way, was now reproducing in Augustus’s Golden Age. The historian Suetonius (ca. A.D. 69–after 130), the author of The Lives of the Caesars, reported that before dying, Augustus uttered these words: “I found Rome built in bricks; I leave it clothed in marble.”

When Julius Caesar died, Rome was already a relatively developed urban center. But the toll inflicted by the long years of civil unrest, combined with an overall lack of urban planning and the squalid quarters in which many poor plebeians lived, kept the living conditions of Rome far below the standards that characterized many Eastern cities. To address the problem and give Rome the appearance it deserved, Augustus took many important steps. The first one was to pour a lot of money into upgrading and repairing the basic infrastructure of the city, like roads, canals, bridges, and sewers. He placed armed policemen in bandit-ridden areas and even instituted the first rudimentary fire brigades that serviced the city during the night hours. In addition, Augustus greatly upgraded Rome’s water supply through the repair or building of new aqueducts. The project favored the rich, who could now afford fancy heated bathhouses in their private homes, but also the greater population, who, for the first time, could enjoy the amenities offered by the solace of the many refreshing fountains that began to dot the city and also the pleasure of public baths, or thermae—the imposing structures decorated with a great amount of statues, marble-covered walls, and mosaic floors that contained pools and also massage rooms and sweating rooms.

Claiming that the gods had taken offense at the scandalous deterioration that so many shrines suffered, Augustus also promoted the restoration of a great amount of temples. His aim was to rekindle the religious devotion of the citizens in view of an increased respect for the state. For that reason, just as Julius Caesar had done before, Augustus assumed the title of pontifex maximus (A.D. 12), who, just like the father within the microcosm of the household, was assigned to perform the rituals that assured the peaceful concordance between the patron divinities and the state. Exploiting the lofty prestige that the position of pontifex maximus embodied, Augustus was able to convince his fellow citizens that his leadership had been directly chosen by the gods, who, like a father within the family, had assigned to him the guardianship of the city.

To bestow upon Rome a mantle of munificence, Augustus’s architects closely followed the guidelines developed in Greek classical times: from the use of columns (with Corinthian, Ionian, or Doric capitals, to which the Romans added a hybrid form known as Composite), to the design of elegant temples and basilicas—the elongated halls framed by side colonnades that were used as law and business courts.

To add color to that great scenario, a polychrome variety of stones and marbles (which were also used as a reminder of the amazing geographic expansion of the empire) was deployed: yellow and ocher marble from Numidia, deep-red porphyry from Egypt, translucent alabaster from the Near East, pure-white marble from the island of Poros in Greece or the Luna quarries in Italy, besides all the hues of pink, gray, or red derived from different kinds of granite.

To further bolster the reputation of Rome, Augustus’s propaganda used the city as a showcase for the most prestigious trophies of war—like those pillaged from Egypt, a country that always fired up the Roman imagination with the mysterious beauty of its old and legendary civilization. Among the most striking spoils was the magnificent obelisk from Heliopolis, a huge phallic symbol that represented the god of light and fertility, Osiris. Once in Rome, the obelisk was rededicated to Apollo and placed on the central spina of the old arena, called Circus Maximus, which was used for popular sports, especially chariot races.

Making Apollo the patron of the circus was a fitting choice because, in the myth, the sun god daily drove his four-horse chariot across the sky. The celebration of Apollo was also an indirect way to praise the leader of the empire, who had elected Apollo as his patron-god. Significantly, the imperial image that was placed on Augustus’s triumphal arch (and on his enormous mausoleum) was that of the sun god Apollo proudly riding his golden chariot. The connection with the god was also used to reinforce a popular rumor that claimed that Augustus’s mother had been impregnated by Apollo, who appeared as a snake while she was asleep in his temple. Augustus never addressed the story, but the simple fact that he never openly denied it seemed an indirect acknowledgment of the veracity of the rumor. Mystery and magic did the rest: the emperor was soon revered as a mythical figure by the highly impressionable people of Rome.

Although full of Greek references, the architectural style that prevailed during Augustus’s age followed the Roman preference for the massive and the imposing in contrast with the more restrained sense of balance and measure that had characterized the simple elegance of Greek classical times—a tendency that was further elaborated by the brilliance of Roman engineers who also perfected the use of the arch and the vault.

Even if larger and somehow more grand and showy, the austere solidity that Rome’s architecture radiated expressed the same tendency toward clarity, proportion, and rationality made popular by the Greeks. Vitruvius (ca. 80/70–ca. 15 B.C.), the famous architect and engineer who lived during Augustus’s time, wrote in his treatise On Architecture that an architect was to be an educated man with knowledge of arithmetic, geometry, philosophy, history, law, astronomy, and music. Vitruvius’s stress on a well-rounded personality shows the affinity with the Greek concept of paideia, according to which education, more than a simple accumulation of knowledge, involved an overall process of mental and spiritual growth and maturation.

If the architect, Vitruvius stated, wanted to express beauty, he had to first understand the timeless quality of beauty as it transpired in the symmetry and proportion that, for the Romans as for the Greeks, pervaded all natural things. Following a well-established philosophical tradition, Vitruvius attributed an ethical and pedagogical intention to the beauty of art—a beauty that, just like the verbal refinement of rhetoric, was expected to inflame the heart and mind of the viewers toward greater and nobler thoughts and ideals. (Rome’s urban plan became a model for all other cities of the empire, which, besides a central forum, had theaters, temples, and baths.)

Among the architectural initiatives that Augustus undertook, none was more important than the new Forum bearing his name, which was built in the center of the city, adjacent to the Forum of Caesar. The Forum was a square flanked by two long lines of colonnades.

In the many niches that appeared between the columns stood the statues of the most famous republican personalities—all the heroic and larger-than-life characters (like Cincinnatus) whose stoic and selfless devotion had sprinkled with the golden dust of eternal glory the history of the early republic. Naturally, the model of perfection that stood at the top of that mighty pyramid of virtues was embodied by the father of the nation: Augustus, whose forty-six-foot-high marble image was kept in an ornate cell at the end of one of the colonnades. The association with the founding fathers of the republic was an implicit way to affirm that the history of Rome had reached its pinnacle with Augustus, the ultimate champion of Roman greatness.

The new Forum built by Augustus associated the emperor in every way with the virtuous and heroic old republic. Credit 3

Within the Forum was also the temple of Mars Ultor (Mars the Avenger) that Augustus built to celebrate the famous great-uncle whom he had promised to avenge. Paul Zanker, the author of an important book about Augustus’s use of images, explains that the choice was also meant to recall the mythical origin of Rome. According to legend, the god Mars, in one of his many escapades into the world, had managed to impregnate the vestal virgin Rea Silvia, daughter of Numitor, king of Alba Longa, who had been displaced by his brother Amulius. When Rea Silvia gave birth to the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, Amulius, to eliminate the possibility that one day the boys might threaten his rule, tried to kill them by throwing them in the river Tiber. But the babies survived, saved by a she-wolf that nursed them with her milk and then by a shepherd who took care of them as if they were his own children. When they grew, the twin brothers decided to found a new city near the banks of the Tiber. While they were choosing the exact location for the future city, a dispute arose between the two brothers. Following an old tradition, Romulus plowed a furrow to mark the perimeter of the future city. When Remus dared to jump over that limit, Romulus killed him, thus marking with brotherly blood the beginning of Rome. The bottom line of that complex use of mythology was that while Mars seeded the martial virility of Rome, Venus (from whom the Julian family derived) was the guarantor of its formidable prosperity.

To celebrate the inauguration of the Forum, the emperor financed many popular events: athletic contests, acrobatic shows, chariot races, plus a great amount of animal hunts. (It seems that just for the inauguration of the Forum, 260 lions were slaughtered to amuse the people of Rome.)

To avoid any undesired comparisons with the grandiose pretentiousness pursued by the Hellenistic monarchs, Augustus made sure to always maintain a very low-key demeanor in his daily life. He lived in a simple house decorated with plain furniture, ate coarse food, and wore a homespun woolen tunic that was said to have been woven by his wife and his niece instead of by a slave. Skillfully performed, that humble conduct was designed to portray the emperor as an unflappable leader who had gained authority by moral prestige rather than by ambition, cunning, and intrigue. The fact that his house stood right next to the temple of Apollo had an important symbolic meaning: in contrast with Marc Antony, who, driven by moral flabbiness, had compared himself to Dionysus, Augustus always presented himself as a faithful follower of Apollo—the god of rationality, measure, balance, and restraint.

The most important sculptural image of the emperor is known as Augustus of Prima Porta. In a way that is strikingly reminiscent of Polycleitus’s Doryphorus, the greatness of the emperor is expressed through a godlike beauty that is at the same time physical and mental, as indicated by Augustus’s firm yet calm and confident demeanor—a demeanor to which a special touch has been added: the raised arm typical of an orator. Why is the detail so important? To answer, we have to turn again to the Greeks, who, since the time of Homer, had always deemed oratory a political necessity, especially among military leaders, who, in order to encourage their soldiers to face death with dignity, had to remind them of the eternal glory that their sacrifice would earn them. Later, as we have seen, the art of oratory was given a dangerous twist by the Sophists, who argued that a beautifully crafted speech was an ideal tool to gain influence on the political stage. The Sophists’ position was vehemently opposed by Socrates and Plato as well as by Aristotle, who, in his Rhetoric, claimed that to maintain words free from the malevolent spin of demagogy, the orator was to firmly weld the Logos of eloquence with the Logos of reason and morality. The immense resonance that Aristotle’s lesson produced informed the solemnity attributed to the propagandistic image of Augustus—the man whose just actions and just words were equally trustworthy for their honesty and integrity. To support that claim, Augustus always applied to his words the same simplicity he kept in his personal demeanor. Suetonius said that the emperor willingly avoided any forced and affected verbal embellishments, which he called “the stink of far-fetched phrases.” His ambition was not to impress the audience with a sonorous speech but to gain the trust of the people through the clarity and transparency of a few direct and honest words. (Americans will ascribe a similar verbal ability to the greatest of presidents, Abraham Lincoln.)

The famous Augustus of Prima Porta—every inch a confident leader and close to a god

The clear conviction that the calm composure of Augustus’s statue conveyed was also a way to address the emperor’s role as pacifier interested in bringing law, peace, and unity to the great racial, cultural, and religious diversity that constituted the Roman commonwealth. Those who had resisted Roman power were described as treacherous people, like the uncivilized Parthians depicted on the cuirass, or breastplate, of the statue. The event evoked the recovery of the military standards that the foe Parthians had snatched away from the Romans during a battle along the eastern frontiers of the empire. (The Parthians, who occupied a region that more or less coincides with today’s Iran, were the most formidable enemies that Rome had in the East.) The episode was chosen to show how the uncivilized easterners had been put to shame by the superior nobility of the Roman race.

What is interesting to notice is that to increase the mythical aura that surrounded Augustus, his image, in contrast with the crude realism so congenial to the Romans, always bore the idealized traits of a handsome, strong, and eternally young man. Indeed it was a very flattering portrait for a man who, in reality, seems to have been quite frail (Suetonius tells us that he often suffered from colds, diarrhea, bladder problems, and rheumatism) and unattractive (to conceal his modest height, Augustus would wear shoes designed to elevate him a few inches). The fact that time transformed the appearance of everyone, except that of the eternally young and beautiful emperor, was a way to elevate him to a super-mundane status—a reference underlined by a small Cupid riding a dolphin that was used as a reminder of his divine lineage as a descendant of Venus (Cupid was Venus’s son). The detail was also meant to confirm that Augustus’s ascent to power had not occurred by chance but been directly foreordained by the gods.