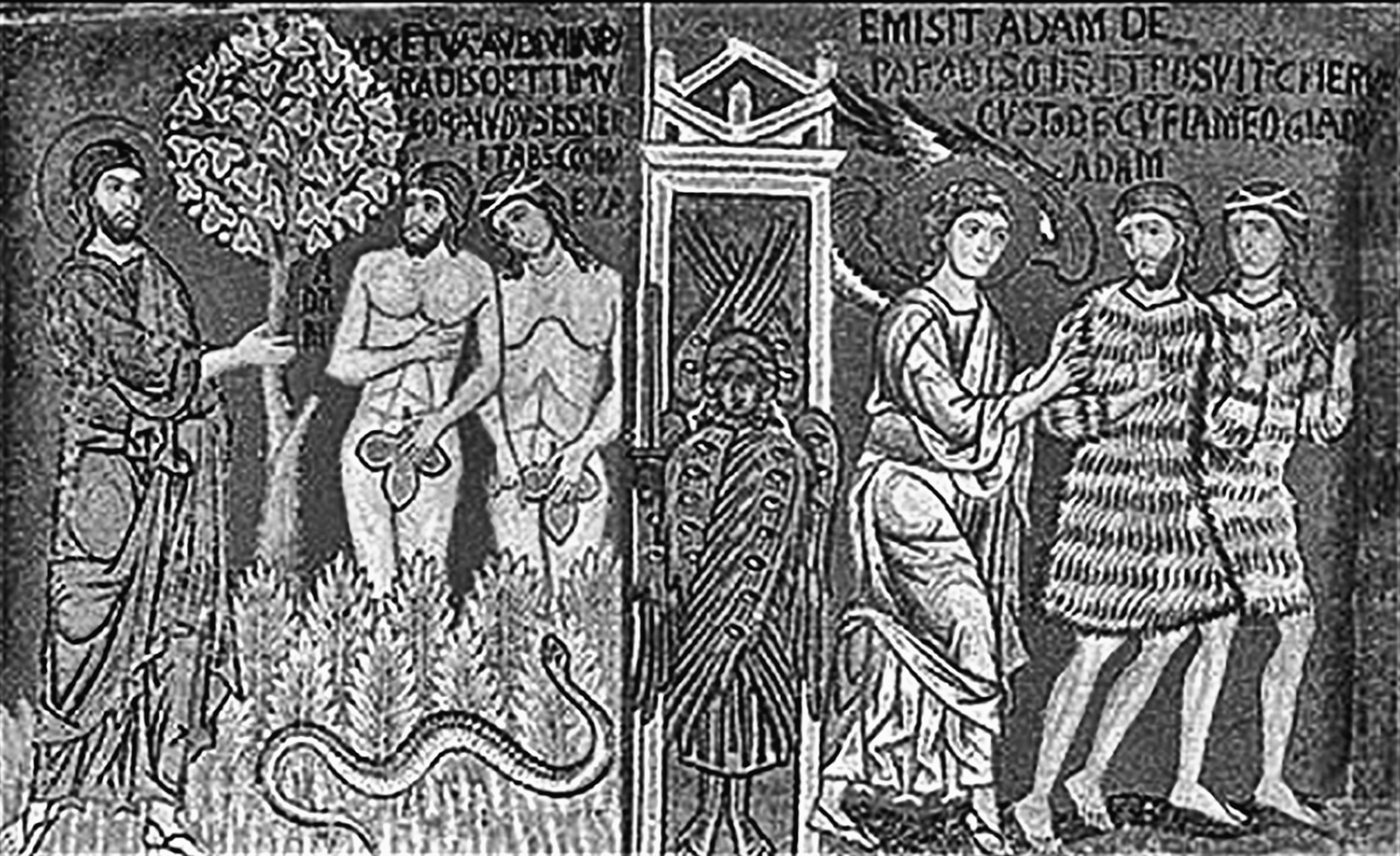

Adam and Eve, depicted in medieval imagery, being expelled from the Garden of Eden

Christianity, an offshoot of Judaism, is based on the teachings of Christ, Who was born around 4 B.C. and lived in Judaea and Galilee. Because the Middle East, where Christianity developed and spread, was essentially Greek in culture and mentality, the evolution of Christianity ended up assimilating many ideas derived from the Hellenistic heritage. We should remember that next to a pure Greek influence (Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, and so on), that heritage also included many traditions and ideas that the West acquired from the East when Alexander the Great stretched the boundaries of his empire as far as India. Many Mystery cults, like Orphism, were part of that enlarged Hellenistic horizon, as well as religions like the Persian Zoroastrianism and Manichaeanism. To the various influences that Christianity received in its complex development, we should also add ceremonial traditions (like chanting, the use of candles, incense, and holy water) and the institution of the priesthood, which probably derived from Syria, Egypt, Babylon, and Persia. Of course, of the myriad tightly woven threads that spun the doctrine and ritual of Christianity, none is more important than the one that it derived from the People of the Book—the Jews.

The Christian Bible is formed by the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, and the New Testament. Some parts of the Old Testament were composed almost a thousand years before the New Testament. The first five books of the Old Testament (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy), called the Torah in Hebrew and the Law in English, relate the story of creation, the sin and fall from paradise of Adam and Eve, the escape of the Hebrews, God’s chosen people, away from the foreign bondage in Egypt, and the conquest of the promised land. The New Testament, which scholars believe was originally written in Greek, revolves around the figure of Christ (who probably spoke Aramaic, the common tongue of Judaea). The New Testament includes the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles (which include the letters of Saint Paul), and the book of Revelation.

Contrary to the impersonal Demiurge that for Greek philosophers was behind the order of the cosmos, Christianity described the world as the loving expression of a Creator so invested in His creation as to honor the sanctity of every human being beyond any disparity of status, privilege, and fortune:

Blessed be ye poor: for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are ye that hunger now: for ye shall be filled. Blessed are ye that weep now: for ye shall laugh.

(LUKE 6:20, 21)

For the class-conscious society of pagan times, the change was revolutionary: all who had previously been rejected and forgotten (the dispossessed, the outcast, the slave, the oppressed, the prostitute) were now accepted and welcomed in the kingdom of God. The star of Bethlehem, which was said to have announced the birth of the Messiah to the mighty kings and the poor shepherds alike, was meant to mark the beginning of a universal ideal of justice unthinkable before, where all human beings were granted a similar level of importance under the common denominator of children of God, equally valued and equally respected.

The principle did not find an immediate application in reality. In fact, it took many more centuries to mitigate horrors such as slavery or the disparaging treatment of women. Nonetheless, the respect for the sacredness of human life that Christianity preached enormously influenced the cultural development of the West especially from a legal and juridical point of view.

The extraordinary value that Christianity attributed to human life found its origin in the Jewish narration of the biblical Genesis, where God, having called the world into existence, was said to have forged out of clay a creature made in His own “image and likeness.”

Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth. So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him.

In man God had selected a near replica of Himself: an interlocutor meant to share His eternity to become, next to Him, the master of all creation—a position of privilege that was confirmed when God assigned to man the power to name all the animals that populated His kingdom:

God…brought them [animals] unto Adam to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.

This spectacular bond with the divine raised to an unprecedented level the worth of the human creature. But everything came to a crashing end when Adam and Eve (whom God shaped out of Adam’s rib) ate the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge that, as God had commanded, was to remain beyond their reach.

When he tempted them, the serpent had promised Adam and Eve the acquisition of God’s knowledge. The falsity of that promise was revealed by the punishment that the first two humans received as soon as, plucked away from the sky, they were plunged into the earth, where their souls, stripped of their robes of light, remained buried, as in a tomb, in the corruptible tunic of flesh of the body.

With man’s subjective choice, God’s objective reality was lost forever: eternity was replaced by history with its unforgiving constraints of time and space. It was at that moment, the Bible says, that Adam and Eve realized they were naked. The nakedness symbolized the vulnerable poverty of their newly acquired condition: the frailty of the body, the insufficiency of the mind, the sweeping nature of time, the brutal finality of death.

Instead of a superior form of understanding, all that Adam and Eve gained with their transgression was ignorance, pain, and confusion within a shattered world marked by the struggle of all living creatures competing for dominance and survival. Thrown into that battle, the two humans were lowered to the level of animals over which they had previously ruled. To describe man’s newly acquired identity, religious writers often talked of a sort of animalization. The furry skins that in many medieval depictions cover the nudity of Adam and Eve were used to symbolize the animal-like condition that humanity had descended to after the Fall.

From that moment on, to exist became equivalent to living away from the place of one’s origin: in other words, living in exile like a stranger lost in a foreign and unforgiving land. (Etymologically, “to exist” comes from the Latin ex stare, which means “stay outside.”)

In describing the odious hyle of the terrestrial dimension—in Greek, hyle denoted the formless matter of chaos—Christian thinkers defined the world as a “region of unlikeness” or, echoing the Old Testament, an “Egypt of matter.” The disparaging terms were used to describe the world as a place of painful captivity in contrast with the blissful harmony experienced in the lost homeland of paradise.

Adam and Eve, depicted in medieval imagery, being expelled from the Garden of Eden

How could a creature so tightly enmeshed in the dull and dark consistency of matter regain the spiritual lightness necessary to soar back toward the kingdom of God?

The answer, for Christianity, resided in the compelling story of a forgiving God who, having assumed through Jesus Christ a corporeal form, made possible the restoration of man’s original state despite all the deficiencies and tribulations caused by sin.

The Christian idea of a compassionate Creator derived from the Jewish tradition, where God, expressing His love for the Israelites, His chosen people, earnestly assisted their journey, from the subjugation they suffered under Egyptian domination, to the conquest of a homeland where, in harmony with God’s divine will, Israel would finally rejoice in justice and freedom.

Despite so many similarities—each saw life as a journey from shackles to freedom—what distinguished Christianity from Judaism was the who and the where of the story. Whereas the Jews dreamed of a kingdom of justice on earth for the benefit of God’s chosen people, the Christians focused on a spiritual rather than an earthly kingdom: a superhistorical and superterrestrial promised land universally available to all of mankind.

To return to that celestial homeland, man had to retrieve the fragment of divinity that still shone, like a precious gem, within the fractured nature of his terrestrial reality.

Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! for, behold, the kingdom of God is within you.

(LUKE 17:21)

God’s glory resided in the deepest recesses of the human spirit, far removed from the bleakness of the earthly ordeal. As Paul stated in his Second Epistle to the Corinthians, “Whilst we are at home in the body, we are absent from the Lord.”

Because no escape from that exile was possible without the mediatory intervention of Christ, and because no knowledge of God could have taken place without the transformative action of His Word, the message that the New Testament contained principally focused on the life and teachings of Christ. Not what He wrote—Christ, like Socrates, did not leave any written testimony—but what was reported about Him in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Historians have established that, unlike what was believed in the past, the Gospels (meaning “good news”) were not written by people who personally met Christ but by authors who composed their account toward the end of the first century A.D. The Gospels were made part of the New Testament around the second century A.D.

The word “synoptic,” applied to the Gospels, refers to the similarities in narratives and themes that the texts contain, with the exception of the more complex and intellectually challenging Gospel of John, in whose mystical approach God’s kingdom is described as a crystalline triumph of light in contrast with the gloomy darkness of the world. Pivotal to John’s theological approach is the definition of God as Logos: a term that in Greek, as we have seen, simultaneously meant “word” and “reason,” and was used in the Hellenic tradition to indicate the ordering force of a divine Rational Mind. Adapting the term to Christianity, John, at the beginning of his Gospel, used “Logos” to define the creative power of God: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

The vein of Platonism that runs through the Gospel of John finds further echoes in the contribution of Paul (ca. A.D. 5–ca. 67): a cultivated Hellenistic Jew who took an active part in the persecution of early Christians until he underwent a sudden conversion while on his way to Damascus. In the Acts of the Apostles (9:3–6), Paul’s sudden illumination is described as follows:

And as he journeyed, he came near Damascus: and suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven: And he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, “Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?” And he said, “Who art thou, Lord?” And the Lord said, “I am Jesus whom thou persecutest: it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks.” And he trembling and astonished said, “Lord, what wilt thou have me to do?” And the Lord said unto him, “Arise, and go into the city, and it shall be told thee what thou must do.”

Paul—Saul was his name before the conversion—who, from that moment on, dedicated his life to the teaching of Christ, is believed to have died in Rome, in A.D. 67 during the persecutions against the Christians unleashed by Nero. In the Epistles he wrote to the Christian communities he founded, Paul brought to a whole new level of clarity the Christian idea of salvation.

To explain the essential meaning of Christ’s mission, Paul focused on the ritual of baptism:

Know ye not, that so many of us as were baptized into Jesus Christ were baptized into his death? Therefore we are buried with him by baptism into death: that like as Christ was raised up from the dead by the glory of the Father, even so we also should walk in newness of life.

(ROMANS 6:3–4)

Through the ritual of baptism, Paul preached, the initiate was encouraged to symbolically imitate Christ, who died on the cross to free the human soul from the prison of matter:

I am crucified with Christ: nevertheless I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me: and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself for me.

(GALATIANS 2:20)

As in the sacrifice of the cross, baptism simultaneously indicated the death of the flesh and the resurrection of the spirit: in other words, the replacement of the old Adam with the new one that Christ, as archetype of human perfection, embodied. Paul, who, more than once, called Christ the “new Adam,” wrote in the First Letter to the Corinthians, “For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.”

The aim of the believer was to humbly forsake selfhood in order to gradually advance toward the greater perfection of God. The transformation that God required was not confined to the body: as Paul explained, the mission of Christ also involved a drastic indictment of the excessive value given to the human mind.

Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato had all maintained that the soul was the seat of reason and that reason was the highest and noblest quality of human nature. For Christianity, on the other hand, reason possessed characteristics that, more than to the soul, belonged to the body with which it shared similar deficiencies and appetites. The point was addressed by Paul, who repeatedly insisted that God, Who transcended all things, also transcended human knowledge. To make his point, Paul dismissed with these words the arrogant confidence previously assigned to human reason: “The foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men.”

In contrast with the classical tradition, Paul rejected the importance attributed to the rational mind, affirming that it was an insufficient means toward a superior form of understanding unless assisted by the auxiliary help of Grace as represented by Christ. To stress the inadequacy of reason, Paul went as far as to compare humans to helpless, suckling babies, in need of the “milk” provided by the teachings of Christ, without which they would have been unable to absorb the food of true understanding:

And I, brethren, could not speak unto you as unto spiritual, but as unto carnal, even as unto babes in Christ. I have fed you with milk, and not with meat: for hitherto ye were not able to bear it, neither yet now are ye able.

(1 CORINTHIANS 3:1–2)

Christ’s frequent use of parables was justified in a similar way in the Gospel of Matthew (13:13):

Therefore speak I to them in parables: because they seeing see not; and hearing they hear not, neither do they understand.

Since the Fall of Adam and Eve, the Christian doctrine claimed, mental deficiencies had imprisoned humans on the surface of reality, unable to see, hear, or understand the innermost significance of things. To overcome the limit of man’s superficial and horizontal kind of perception, Christ used an enigmatic and indirect form of storytelling aimed at challenging mental habits and preconceptions, in order to spark a deeper and more refined form of understanding.

Augustine, in his On Religious Truth, addressed the teaching method of Christ with these words:

God did not disdain…to sport with our childish mentality by speaking in parables and similes and to cure with clay of this kind the interior eyes of our souls.

Because man’s crippled faculties would have been overwhelmed when confronted with God’s immensity, the use of an indirect idiom consisting of parables, symbols, metaphors, and similes became central in describing the message of the divine. Why? Because, Augustine asserted, just as fairy tales do when teaching moral principles to children, they reduced to an accessible level the complexity of the divine discourse.

Christ’s use of parables was aimed at stimulating man’s emotional and intuitive awareness through stories that encouraged new ways of thinking beyond the linear channels of logic and rationality. Accordingly, the third-century Christian apologist Clement of Alexandria (ca. A.D. 150–ca. 215) compared Christ to a pedagogue, a teacher who had come to assist the growth of man’s inner potentials beyond what the Christians considered the flat, prosaic, and ultimately ineffective syntax of all rational and empirical discourse.

Following those guidelines, the novice was taught that, just like the truth that lay deep beyond the surface of the world, the words of the Bible were to be not taken literally but rather used as clues constantly pointing toward something else—something that moved the spirit forward toward a meaning that, ultimately, could be alluded to only indirectly because it was irreducible to any earthly forms of comprehension.

To further explain the revelatory quality of the biblical message, Augustine compared the inner significance of the words to the soul within the body. The words of the Bible, Augustine wrote, were like “fleshy robes” covering the deeper meaning that waited to be unwrapped—a task that was achievable only by exploring the message of the Bible with the eyes of the spirit rather than the eyes of the flesh.

The view shows the influence of the Jewish tradition, where text and interpretation were considered not two separate entities but two connected aspects of revelation. George Steiner, in his book Real Presences, explains that the purpose of Jewish exegesis was to expand, as in an unending process of signification, the message contained in the book of God: “In Judaism, unending commentary and commentary upon commentary are elemental….The lamps of explication must burn unquenched before the tabernacle. Hermeneutic unendingness and survival in exile are, I believe, kindred.”

The dynamic by which each word and each image of the Bible was made to expand as with growing ripples of signification evoked the infinity of God’s metaphysical mystery: the unmeasurable, indescribable, unreachable Logos of the Father Who had given life and form to the entire universe.

The endless decoding that the mystery of the Bible demanded is described by Northrop Frye, in his book The Great Code, as “a single process growing in subtlety and comprehensiveness,” to express not “different senses, but different intensities or wider contexts of a continuous sense, unfolding like a plant out of a seed.”

The sentence echoes Matthew 13:23, where Christ compares his words to seeds: small on the outside but full of creative energy if planted in the appropriate kind of soil.

But he that received seed into the good ground is he that heareth the word, and understandeth it.

Just as a small seed produces an enormous tree, the humble words offered by the Bible were said to bloom into heavenly visions if placed in the nurturing terrain of a heart made appropriately fertile by the abundance of faith.

To affirm that faith was the only possible path to God, Augustine wrote, “Seek not to understand that you may believe but believe that you may understand.” What Augustine meant to express with that assertion was that faith was indispensable for the achievement of true knowledge. The value of human reason, which for so many centuries had remained supreme, was now surpassed by a faith placed directly at odds with tangible certitudes, rational argumentations, and logical conclusions. More than the intelligence of the mind, what was needed to reach God was the intelligence of the heart—the faith that Christ demanded when He asked humanity to plunge with Him into a depth that, just as in the ritual of baptism, was a paradoxical unity of annihilation and fulfillment, darkness and light, blindness and vision, death and life.

The transformative quality attributed to Christ’s supernatural intervention was also stressed to support a written religious tradition among a population that, being in great part of pagan descent, was accustomed to attributing the validation of its creed to a purely oral exercise. The historian Charles Freeman, in The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason, writes that it was not until A.D. 135 that the first Christians, of pagan background, finally started to accept the value of the biblical written text, acknowledging its authority over the oral tradition that for centuries had been considered the only legitimate vehicle of religious transmission.

As we have seen, the distrust toward the written word goes back to the Greeks. In the Phaedrus, Plato, using his alter ego Socrates, attacked the stiff and static quality of the written word, claiming that by immobilizing the dynamic of the oral exchange, it induced a dangerous state of mental atrophy. Plato’s use of dialogues to develop his philosophical ideas was consciously selected with the intention of preserving the lively ebb and flow of the oral argument without which, Plato believed, the progress of knowledge would not occur.

With the passing of the centuries, the animus toward the written word subsided. But when Christianity, following Judaism, introduced itself as a religion based on the authority of a written text, old concerns about the lifeless quality of the written word inevitably resurfaced. To ward off any possible criticism, the Christians, in agreement with the Jewish lesson, evoked the power of the symbolic discourse.

The etymology of the word “symbol,” as derivative of symballo, which in Greek meant “to gather,” or “to reunite,” can help us understand what’s at the heart of that amazing process of signification. In Greek antiquity, when an agreement between two parties was contracted, an object was broken in two in order to guarantee, until the later reunion of the two partners, the promise of the stipulated accord. The object, which was going to return whole with the reunion of the two parties, was called “symbol.” A similar interpretation was connected to the divine Word, as expressed in the Bible: a sign or symbol that, by constantly pointing past itself, solicited an engaging response on the part of a fully involved reader/believer.

In contrast with the passive acquisition induced by the dead written word that the Greeks had feared so much, the symbolic discourse of the Bible came to be seen as a living process that, by soliciting a dialogue between reader and text, led to further and further depths of understanding man’s awareness of the divine. Failing to go beyond the surface of one’s own immediate experience meant to remain trapped within the literal, and therefore external and superficial, meaning of things—the letter that kills, which, for Paul, was the secular Logos of all the non-Christians.

To exalt the superior knowledge that the Bible imparted, the Christians used the image of Christ: the Logos Who, by dying as a man and resurrecting as a god, lifted the human condition above its physical, mental, and verbal limitations. Christ was the force that freed the soul from the mortal flesh (soma, in Greek) and in so doing liberated the human idiom (sema) from constraints of its mortal tomb (sema). Christ, the divine Logos, represented the transit of the visible into the invisible, which meant the metamorphosis of the ordinary events of life into the extraordinary mystery of God.

The effect that the mediating intervention of Christ produced in bringing together the human and the divine dimensions corresponded to the function of the biblical symbol that restored the cosmic dialogue between God and man that sin had interrupted and that the Word of Christ, as the ultimate symbol of God’s love, had come to heal and restore. Contrary to the healing action that the Word of God represented, the diabolic force of evil (in Greek, the opposite of symbolon was diabolos) indicated disunity and division: the dramatic rift that, since the sin of Adam and Eve, had come to separate humanity from God.

THE SYMBOLIC DISCOURSE OF ART

Could art, which had traditionally been concerned with the tangible appearance of things, be turned into a vehicle of higher contemplation? In other words, could art be placed at the service of the invisible reality of the spirit? The dilemma was further complicated by the suspicion that Jewish tradition had always cultivated against the sin of idolatry intrinsic in the creation of any graven image, as expressed in Exodus 20:4–6:

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

The Jewish belief that the mystery of God could not be contained within any terrestrial form also extended to the verbal domain. The rule was so strict that originally “Yahweh,” the Hebrew word for “God,” was written “YHVH” to make impossible, without vowels, the actual pronunciation of His name.

The ban on images had an enormous impact on early Christians, as attested by the approximately two hundred years that preceded the hesitant beginning of religious art. What overcame that initial reluctance was the pressure of necessity: in a world in which most people were illiterate, the use of a visual narrative offered a unique opportunity to teach the message of the new religion.

The first steps toward a Christian visual language can be found in the catacombs, the underground passages used as burial places by the early Christians. The most notable aspect of those early wall paintings is the hasty and crude style that characterizes them. Some scholars warn us not to dismiss as naive those early Christian representations: if those visual testimonies appear humble and unadorned, they say, it is not because the Christian artists were incompetent and inexperienced but because they consciously chose to be simple.

Because the Christian artists wanted to address the superior reality of the spirit, they deliberately eschewed the likeness of naturalism to pursue a coded narrative meant to suggest, albeit in an oblique manner, something that was believed to remain beyond what the formal appearance of things described. The extremely simple yet highly significant images we see in the catacombs are indicative of that shift of priorities. Instead of a realistic and aesthetically pleasing depiction of characters and events that could have dangerously trapped the eyes on the external and the superficial, a rough and often clumsy use of images was strategically adopted to stimulate the creative imagination of the viewer. The more the images appeared sparse and incomplete, the more the catechumen was forced to look for a meaning that was deeper than what was immediately apparent.

To stimulate a deeper form of understanding, Christians often probed the Old Testament to find allusions to the mission of Christ. Paul addressed the point in the Epistle to the Galatians (3:23–24):

But before faith came, we were kept under the law, shut up unto the faith which should afterwards be revealed. Wherefore the law was our schoolmaster to bring us unto Christ, that we might be justified by faith. But after that faith is come, we are no longer under a schoolmaster.

As explained by Paul, the Old Testament had served an important role of preparation and maturation. But that initial tutorial phase would have remained a dead letter without the life-giving message of Christ, through Whom man’s journey had finally found a coherent and all-encompassing conclusion.

With these notions in mind, let’s look at an image in the Catacomb of Saint Priscilla, where a minimal, sketchy number of details are used to represent a shepherd and his lambs. Asked to interpret the image, an early convert might at first have recalled passages from the Old Testament, or the animal sacrifice that accompanied most religious practices, Judaism included. Even if valid—a Christian teacher would have noted—those interpretations would have remained insufficient without the deeper meaning offered by the New Testament, where Christ was simultaneously described as a divine Shepherd (in the Gospels of Luke 15:3–7 and John 10:11–16) Who had come to guide humanity, represented by the flock of lambs, back to the green pastures of paradise, and also as the supreme Lamb sacrificed to redeem the sins of the world. As Paul wrote in Hebrews 9:12–14,

Christ the Shepherd, as drawn in the Catacomb of Saint Priscilla

Neither by the blood of goats and calves, but by his own blood he entered in once into the holy place, having obtained eternal redemption for us. For if the blood of bulls and of goats, and the ashes of an heifer sprinkling the unclean, sanctifieth to the purifying of the flesh: How much more shall the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without spot to God, purge your conscience from dead works to serve the living God?

With Christ, the Lamb of God, the old rituals of animal sacrifice had become superfluous and obsolete, as John the Baptist had also declared when he said, “Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world.”

To show that Christ was God’s ultimate revelation, images from the Old Testament were repeatedly used as prophecies of the New. The stories most often alluded to with that intent were Isaac saved from the sacrificial knife of his father, Abraham; Jonah swallowed and then spit out by the whale; Daniel in the pit surrounded by lions that were magically tamed; and the three youngsters miraculously spared by the flames that surrounded them in the fiery furnace.

As different tributary streams empty their waters into a primary river, all those narratives were repurposed as anticipations and prefigurations of a future culminating event: the death and miraculous resurrection of Christ, which, as a synthesis and completion of all past narratives, represented the final triumph of good over evil, spirit over matter, life over death.

The sense of awe needed to sustain such an intense kind of faith is well described by Abraham Joshua Heschel in God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism: “Among the many things that religious tradition holds in store for us is a legacy of wonder. The surest way to suppress our ability to understand the meaning of God and the importance of worship is to take things for granted.” Loss of wonder, as well as the belief that all mysteries could be fully explained, is considered by Heschel the biggest threat to religion.

Jonah being swallowed by the whale, also in the Catacomb of Saint Priscilla

Three children being spared in the fiery furnace

He then continues, “Awareness of the divine begins with wonder. It is the result of what man does with his higher incomprehension. The greatest hindrance to such awareness is our adjustment to conventional notions, to mental clichés. Wonder or radical amazement, the state of maladjustment to words and notions, is therefore a prerequisite for an authentic awareness of that which is.”

For a Jew or a Christian of antiquity, the galvanizing passion conveyed by these words would have strongly resonated. The reason was that training the mind to coexist with the uneasiness caused by the enigma of life was considered essential for the development of a higher form of understanding. The corollary idea was that faith was not a peaceful and passive experience but a daring and radical one. Faith required passion and determination: the audacious willingness to push forward one’s quest even if the final destination remained shrouded in mystery.

Faith, for the Christians, was not an act of intellectual comprehension but a rapture and an awakening: a state of emotional fulfillment that occurred when the I, filled with love, merged with and dissolved in the infinity of the divine You.

In contrast with the trust in human reason that the pagan world had so proudly advertised, Christian salvation promised not intellectual satiation but the unquenchable passion for a God who was to remain elusive and unknowable to all earthly attempts to pinpoint in words, thoughts, or images the vastness of His mystery.

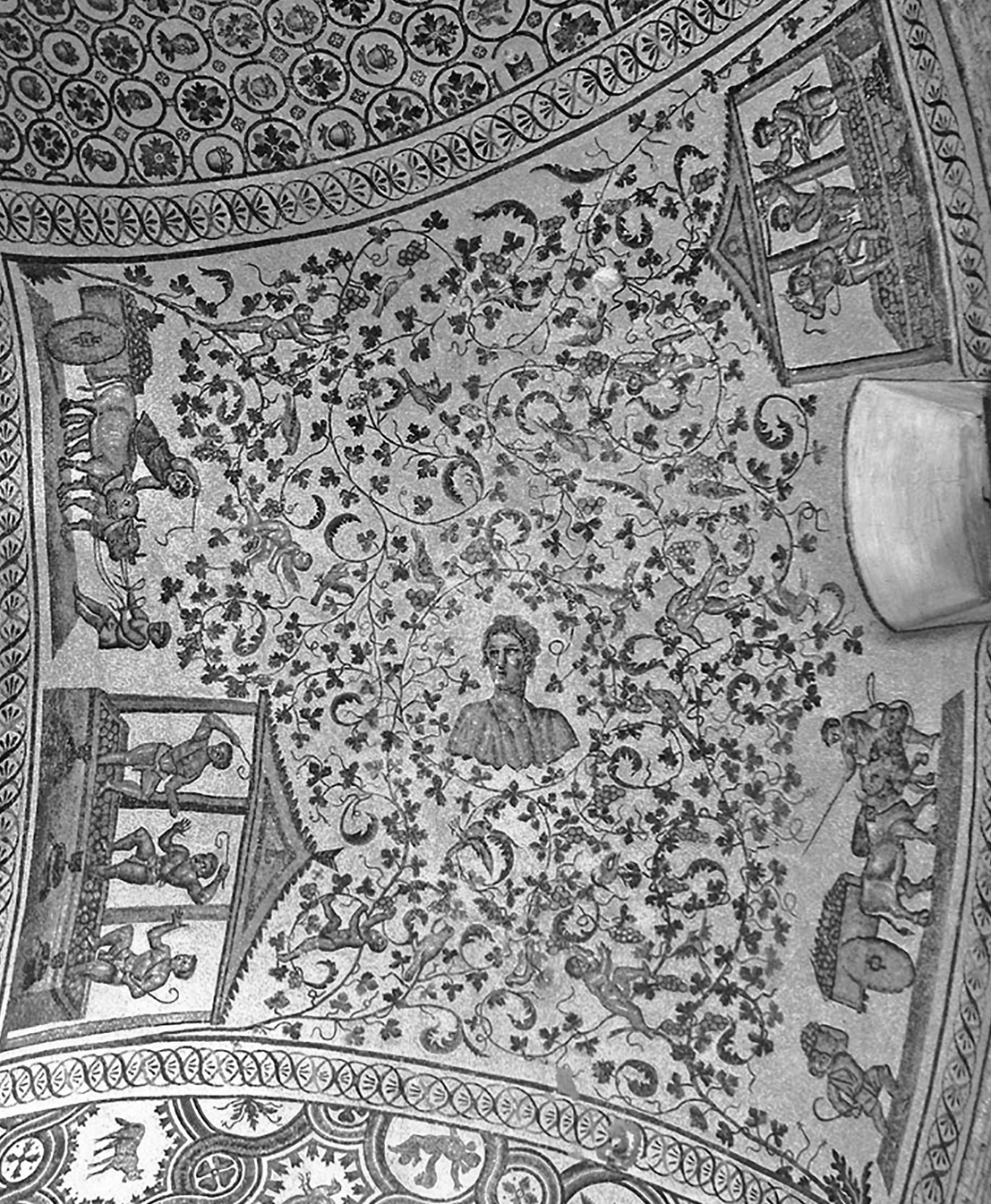

To stress that God surpassed all earthly horizons, Christian artists made sure to never describe the heavenly Father, using, in His place, only the image of Christ: the living icon through which the invisible God had chosen to reveal Himself to the world (“He that hath seen me hath seen the Father” [John 14: 9; 12:45].)

In line with that principle, the only feature of the Father that the artists of the Middle Ages ever dared to depict was a hand barely appearing from the sky. Aside from that reference, the unknowable and indescribable God was only made manifest through the mediating image of Christ, Who had come on earth to reshape humanity in God’s image and likeness. What’s interesting to note is that despite the enormous relevance given to the image of Christ, the gruesome depiction of the body hanging on the cross (which became common many centuries later) was consciously avoided in early religious art.

To understand the reason behind that choice, we have to remember the sharp contrast that separated the Christian Messiah from the Messiah expected by the Jews: a man who, as the prophets had announced, was going to be a strong and powerful military leader and who would have finally assured the triumph of Israel for the benefit of God’s Chosen People. The difference between that Messiah and the meek and apolitical Jesus could not have been starker: far from assuring the triumph of an earthly kingdom, the land promised by the Christian Messiah was a place of spiritual freedom available to all who humbly abandoned all tangible and material claims. The radical view proposed by Christianity also transpired in the death on the cross suffered by Christ—a death that was considered the most degrading and repulsive form of execution, a punishment traditionally assigned to criminals, slaves, and, in general, people of destitute condition. How, pagans and Jews alike contended, could someone who claimed to be the Son of a heavenly King accept such a terrible humiliation? The scorn and disbelief with which many derided the idea are crudely expressed in a graffito discovered on the Palatine Hill in Rome, which, in order to sarcastically mock someone by the name of Alexamenos who had recently converted to Christianity, depicts a crucified man with a donkey’s head with an inscription that says “Alexamenos worships his god.” In the cruel satire, Christ’s gentle meekness is compared to the stupidity of a donkey. Because of such hostile attitudes, for many centuries Christians preferred to depict the cross as a banner of victory—one where the tortured body of Christ was persistently missing.

All of God the Father that was ever allowed to be rendered in early medieval Christianity was His hand.

A Roman graffito mocking Christ as a crucified beast of burden

The Lamb of God with the cross as a banner of victory. Basilica of Cosma and Damiano, Rome, seventh century A.D. Credit 5

THE NEW VOCABULARY OF FAITH AND SPIRITUALITY

As we have seen, one of the thorniest aspects that confronted Christianity was how to justify Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. To push back on the accusations of those who claimed that such a humiliating death was incompatible with a divine being, the early Christian apologist Tertullian (ca. A.D. 155–ca. 240) resorted to a highly emotional form of rhetorical discourse: “The son of God died; it must be believed because it is absurd. He was buried and rose again; it is certain because it is impossible.”

By using a technique called ad absurdum because it denied the safe ground of logic, Tertullian wanted to prompt in his readers the same kind of mental spark that Paul demanded when he wrote in 1 Corinthians 1:19, “For it is written, I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and will bring to nothing the understanding of the prudent.”

Using a paradox to praise the value of ignorance over the intellectual pride of pagan philosophers, Tertullian went on to compare the wisdom of faith to a fresh flower spontaneously blooming at the margin of a country road, far from the useless chatter of urban schools, academies, and libraries. He wrote, “I don’t appeal to the soul that has been formed in schools, educated in libraries and made full of itself by the wisdom of Greek academies. I rather appeal to the simple, rough, ignorant, primitive soul…the one that one can find along crossroads and deserted country roads.”

The idea that reason unguided by faith was to be distrusted as one of the most dangerous instruments of satanic seduction derived from Genesis, where the selection of Eve as the first sinner (having been the first to pick the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge) implicitly gave a sexual connotation to the excessive desire for intellectual knowledge. Aside from the traditional misogyny, so similar to the feeling expressed by the myth of Pandora, what’s fascinating about that association is that due to its organic nature the craving for knowledge was somehow made comparable to all other human instincts and functions.

Why would God condemn the urge that humans had to know and understand if that instinct appeared to be as natural and necessary as breathing, eating, and reproducing? Although ambiguous, the answer provided by Christian dogma remained unabashed: the goal of man was not to understand the secret ways of God but to submit to His will by responding to His call in view of a restored dialogue between heaven and earth. This attitude, which marked the end of all worldly disciplines deemed incompatible with the approach demanded by faith, such as philosophy and science, gave way to cultural models that ostensibly condemned all forms of critical thinking. Within this new context, the epitome of the upright man became Abraham, who blindly obeyed God’s command to kill his son Isaac, even if the heavenly Father gave him no reason for such a cruel action.

Salvation belonged to the obedient man who didn’t question the will of God nor dare to doubt His intention. Asking for better evidence was definitely unacceptable from a Christian point of view. “What has Jerusalem in common with Athens?” Tertullian famously asked, and then added, “For ourselves there is no need or any wish to learn, except of Jesus Christ.”

With similar fervor, another early church father, Irenaeus (A.D. 130–202), said, “It’s better to know nothing but believe in God and remain in His love, rather than risk to lose Him with subtle questions.”

To vent the distrust toward the mind and its analytical tools, some early Christian preachers went as far as calling philosophy a despicable abomination, while others derided the subtle elaborations of Plato and Aristotle, dismissing them as useless and ridiculous blabber.

In developing such arguments, many Christians of the first centuries were influenced by the belief that the Second Coming of Christ was imminent. When that cataclysmic event failed to occur, the urgency to negate the value of previous intellectual accomplishments slowly waned, leaving room for more inclusive views in regard to the classical heritage. Among those who argued that philosophy was to be considered an asset rather than an obstacle were some Greek theologians belonging to the school of Alexandria, like Clement of Alexandria and Origen. In an effort to rehabilitate past cultural contributions, these Christian thinkers came up with the concept of gradual redemption. The scholar Nicola Abbagnano explains that this interpretation gained particular traction when the hope in the imminent return of Christ began to fade away. As a consequence, the concept of an instantaneous regeneration of the world was replaced by “the idea of a gradual regeneration occurring along the centuries through the progressive understanding and assimilation of the lesson of Christ.”

The new narrative that the Christians developed after the Second Coming failed to occur was that salvation, rather than a short and dazzling drama, was a long and slow process of maturation in which different expressions of culture could be accepted as initial stages of God’s revelation. The view allowed the inclusion of all sorts of past cultural contributions on the basis that they were preparatory steps toward the ultimate knowledge of God. Lactantius (A.D. 240–320) addressed the issue when he affirmed that despite their incompleteness the works of Socrates, Plato, and the Stoics were to be considered useful “fragments” of the ultimate Truth.

As the concept of history became intertwined with Providence, Christianity came to be perceived as the most glorious bloom of a mighty evolution aimed at bringing to maturity the spiritual readiness of the world. The idea that history was the fulfillment of God’s divine plan gave license to the assumption that everything of value produced in the past belonged to Christianity. The view reflected what Justin Martyr had already stated in the second century: “Everything beautiful that has been said belongs to the Christians.”

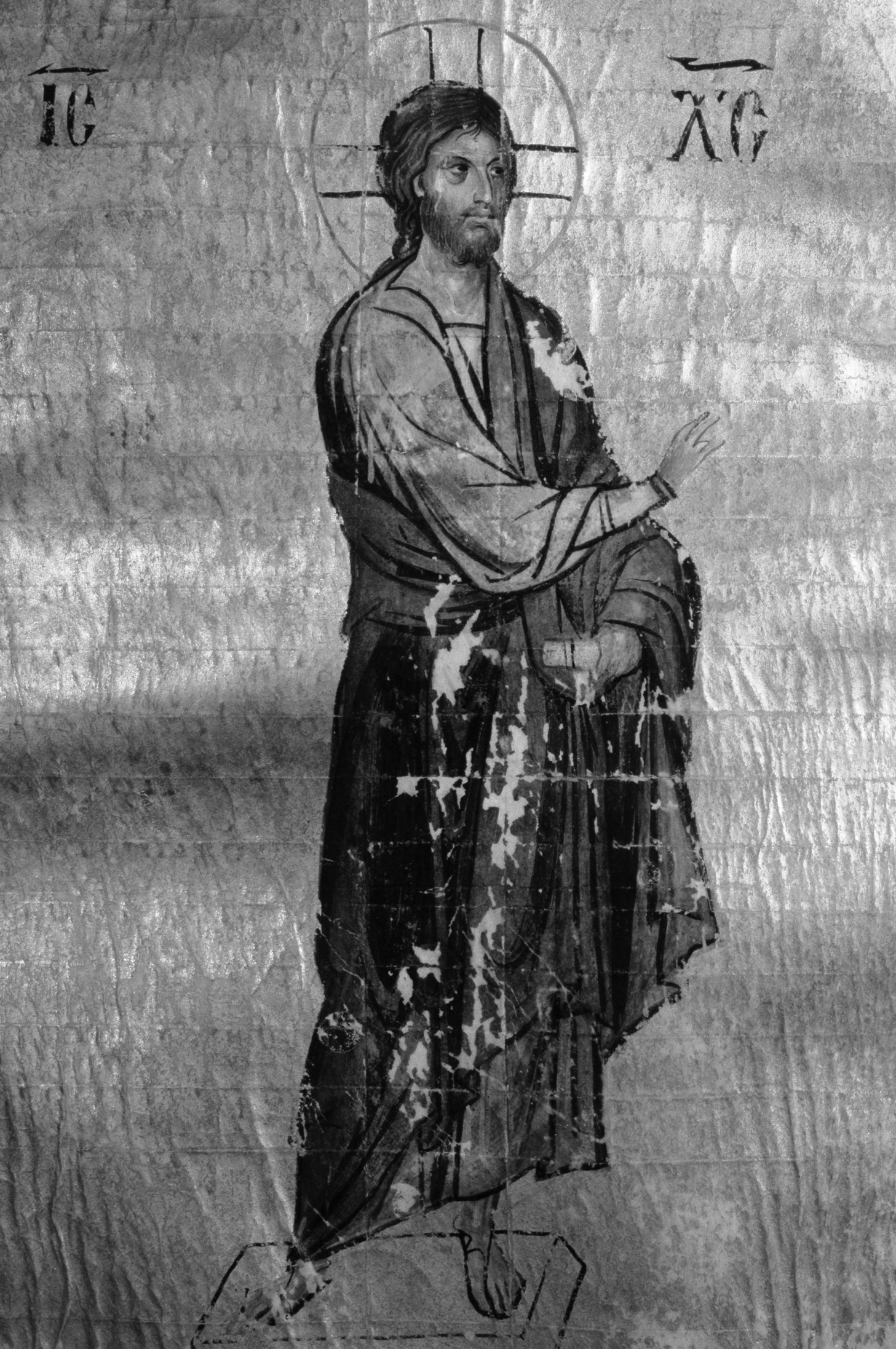

Guided by that principle, freely borrowing from the pagan heritage came to be seen as a fully acceptable practice if useful to the message of Christianity. The attitude proved particularly handy for Christian artists, who often tapped the well-tested reservoir of past mythology and folklore to advertise the content and meaning of the new religion. Examples include the parallel established between Christ and Apollo, the Greek god of light and reason, and between Christ and the Sol Invictus that many Roman emperors had used to celebrate the superior quality of their heavenly derived authority. (In Pagan art, the principal reminder of that connection was the golden halo placed behind the emperor’s head.) In a third-century mosaic, found in the Mausoleum of the Julii under the Basilica of Saint Peter in Rome, references to Apollo and to the Sol Invictus are applied to the image of a resurrected Christ triumphantly rising toward the sky in a manner that appears wholly compatible with the apotheosis of an emperor.

In the Mausoleum of the Julii, images of Christ and Apollo the sun god were conflated. Credit 6

Another famous myth frequently employed to describe the mission of Christ was that of Orpheus: the magic musician who tamed all the animals with the sound of his lyre, just as Christ did when, as the Christian Clement of Alexandria wrote, he came to “tame men, the most intractable of animals.” Using a similar parallel, Eusebius wrote that the Son of God was the healer Who had come to retune man’s discordant instrument:

The Greek myth tells us that Orpheus had the power to charm ferocious beasts. He could tame their savage spirit by striking the chords of his instrument with a master hand. This story is celebrated by the Greeks. They generally believe that the power of melody, from an unconscious instrument, could subdue the savage beast and draw the trees from their places. But the author of the perfect harmony is the Word of God, and He wanted to apply every remedy to the many afflictions of human souls. So He employed human nature—the workmanship of His own wisdom—as an instrument, and by its melodious strains he soothed, not merely the brute creation, but savage endowed with reason, healing each furious temper, each fierce and angry passion of the soul, both in civilized and barbarous nations, by the remedial power of His Divine doctrine.

Christ as Orpheus, the supreme musician

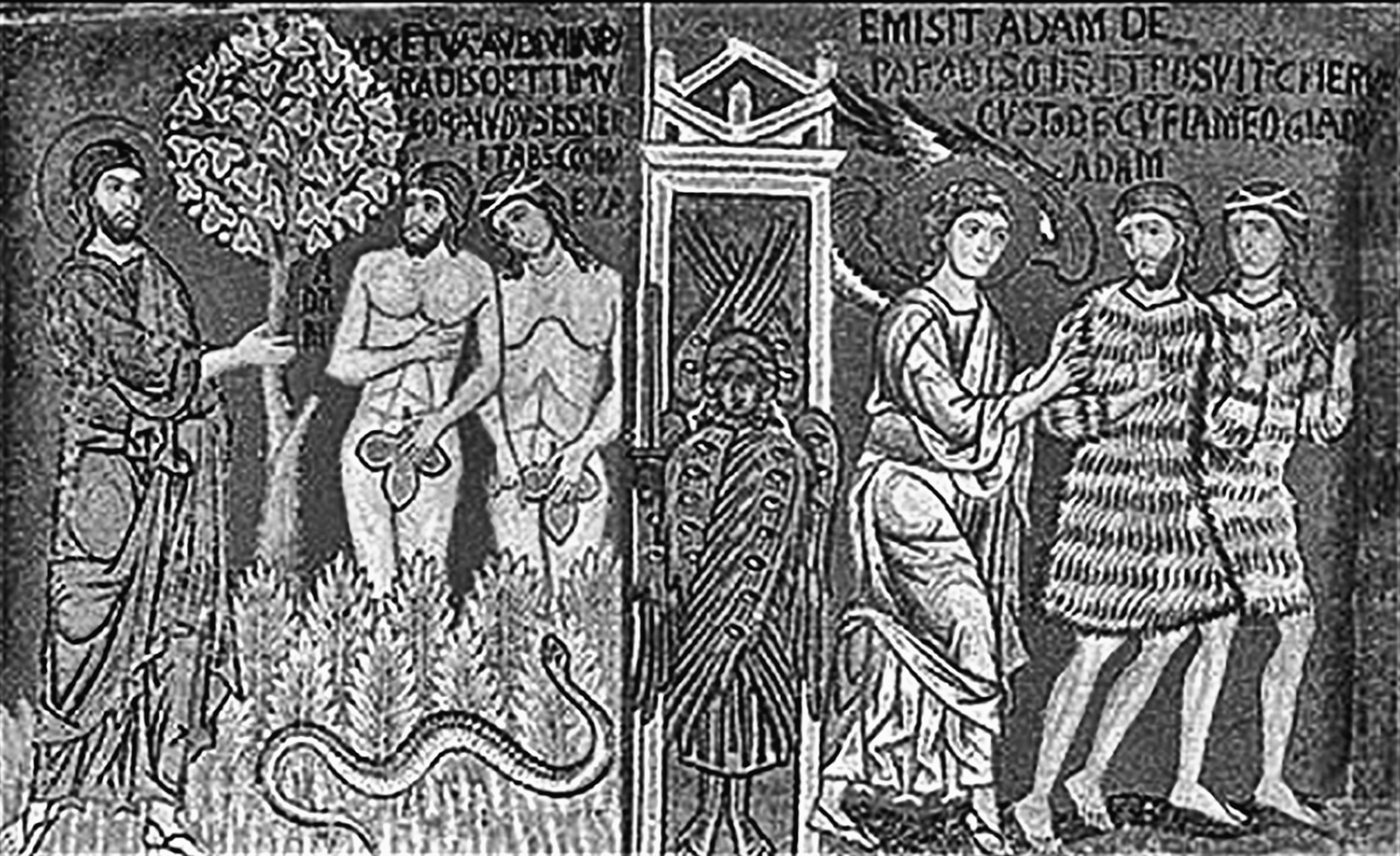

In other instances—for example, in the Roman mausoleum of Saint Costanza, daughter of the emperor Constantine—the essence of Christ’s mission is conveyed through the symbolism of the vine that the pagans had consistently associated with Dionysus or Bacchus.

A multitude of frantically laborious putti compete with birds to pick the mature grapes that fill a fecund and abundant vineyard. As we have seen in Roman times, the references to Bacchus that often decorated the dining rooms of the patricians were used to symbolize the worldly pleasures, including the consoling oblivion of wine. Absorbed and metabolized by the Christian doctrine, the altered-mind condition provoked by wine inebriation was symbolically fermented anew to indicate the transformative experience of Christ’s True Vine, as expressed in the Eucharistic ritual. Within that new frame of reference, the “sober drunkenness,” produced by the wine-blood of Christ, was used to signify the enhanced state of awareness that man was granted when he opened himself to Christ’s saving action.

The first people who had converted to Christianity had come, for the most part, from the lower and poorer strata of society. But when Christianity became legal, many prominent members of the upper classes were added to those early converts (interestingly, the word “pagan,” from paganus, meaning “rustic” in Latin, was used by the Christians from the fourth century on to define the uncultivated country people who still worshipped many gods). The demographic change is made evident by the appearance, around the fourth century, of expensive sarcophagi, beautifully decorated with Christian themes, that the members of the upper class began to sponsor. One of the best examples of this kind of funerary art is the sarcophagus of the Roman prefect Junius Bassus.

A Christianized version of the Dionysian realm of grapes and wine

The affinity that the reliefs seem to share with the naturalistic approach of Roman style is challenged as soon as we realize that what binds together the episodes that the columns frame and separate is not a consequential progression but the unfolding of a symbolic order that emphasizes the mystery of eternity over the linear narrative of secular temporality.

The sarcophagus of the prefect Junius Bassus demonstrates the spread of Christianity to the Roman upper classes.

In the lower register, two stories are presented: on the right, the arrest of Peter and Paul, and Daniel in the lions’ den, on the left, Job, and Adam and Eve. In the center, the victorious but also humble Messiah enters Jerusalem on the back of a donkey or an ass—a symbol that the Christian iconography frequently used to allegorically signify the return of the redeemed soul into the city of God.

The scenes in the upper register represent the sacrifice of Isaac, the arrest of Christ, and his encounter with Pontius Pilate. Even though all those events allude to the sacrifice on the cross, the gruesome depiction of the Passion is avoided. In its place, we see the resurrected and enthroned Christ handing the Law to Peter and Paul while triumphantly resting his feet on the vault of the firmament (represented in a pagan-like manner by a male figure holding a veil over his head).

Eventually, the use of privately sponsored art came to be strongly discouraged by the church, especially when, having acquired more prominence between the fifth and the sixth centuries, the ecclesiastical leadership tightened its control over all religious matters. As a consequence, works of art disappeared from private use to be reassigned to the sole decoration of the House of God. The implicit message was that the only legitimate purpose of art was the collective celebration of God, as expressed by the church, which was at the head of the Christian family.

When the Christian religion became legal, the need to create a temple capable of accommodating the large congregations assembled for the Mass became of primary importance. Using the plan of pagan temples proved useless, because the inner shrine was nothing more than a small room designed to contain a statue of the god. The brilliant solution that Constantine’s architects eventually came up with was to apply to churches the plan of the Roman basilicas—the spacious assembly halls that had once been used as courts of law. The semicircular apse, where in the past stood the seat of the judge, became the place for the altar, which was the fulcrum of the church. To reach the altar, people had to traverse the long stretch of the central hall (later flanked by two additional lateral aisles). The nautical term given to that central hall, “nave,” perfectly fit the Christian narrative that claimed that by entering the ark of Christ’s salvation, the believer initiated a whole new odyssey toward the homeland of paradise.

Once the structure of the church was completed, what remained to be decided was what kind of art was most appropriate for the decoration of the temple. Eventually, it was determined that paintings and mosaics were to be used because they were best suited to the spiritual and visionary nature of the religious message, while high reliefs (like the ones placed on early sarcophagi), and especially statues, were to be strictly avoided. The fear was that the realism of statuary and stone carving might induce the sin of idolatry.

In the Bible, the prophet Isaiah had denounced, with biting sarcasm, the stupidity of idol worshippers who bowed with reverence in front of images of which they forgot that they were themselves the authors: “They lavish gold out of the bag, and weigh silver in the balance, and hire a goldsmith; and he maketh it a god: they fall down, yea, they worship” (Isaiah 46:6).

The power of seduction associated with the art of sculpture had also been addressed in pagan times, most famously in the tale of Pygmalion, who fell in love with the marble figure of Galatea, which he had sculpted, as if it were a real woman. If Galatea had awakened the desire of Pygmalion, it was because his masterly touch had given her cold and stony flesh the softness of a real woman’s body. As a consequence, the artist, blinded by erotic passion, ended up idolizing the object of his own creation.

The fear of delusional passions that the realism of statues could elicit strongly resonated among Christians, as Cyprian, the third-century bishop of Carthage, confirmed when he urged, “When you see a statue, lower your eyes and divert your sight!”

The trepidation that the early Christians felt in regard to the art of statuary also had much to do with the belief that those stony images were not just lifeless objects but hiding places of ghosts and spirits. The fear was compounded by the Christians’ assumption that the pagan gods were in reality demons fond of taking shelter in the stony images erected in their honor.

Considering the great number of statues that filled the cities of antiquity, the Christians certainly had a lot to worry about. A list compiled during Constantine’s time mentions the presence, just in Rome, of at least thirty-five hundred statues. As we have seen, many of those statues represented local and foreign divinities that through war or commerce had found their way into the melting pot of Rome, as well as portraits of emperors, military leaders, and mythological figures. Among the many statues placed in stadiums or bath complexes were also the images of athletes, depicted in the nude, that were meant to celebrate, in a Greek-like fashion, the beauty and strength of the human body.

The most prestigious statues stood on large bases or were raised on top of splendid columns made of marble, jasper, porphyry, or alabaster. Except for the tutelary home divinities, which were represented by small figurines often made of simple materials like wood, clay, or wax, the majority of statues were made of marble or bronze, while a smaller number of more costly examples included silver, ivory, and gold. All marble statues were decorated with brilliant colors, with particular emphasis on the eyes, which were considered windows to the soul.

The alarming feelings that such a profusion of stony presences must have produced among the first Christians, so intensely aware of the seductive power of images, are easy to imagine. From the private to the public sphere—homes, markets, theaters, public baths, forums—the silent stares of a multitude of statues stood at every corner, mingling reality and fiction in an extraordinary and rather surreal coexistence.

In many popular legends, statues were said to have talked, moved, and even stepped down from their pedestals to walk in the streets, disguised among the multitudes of people who crowded the cities of the empire. To counteract the power of those ghostly presences, nothing was considered more effective than the power of sanctity. A Christian legend described Saint Peter crumbling to pieces the statues that stood in the temple of Neptune in Naples by simply calling them down from their exalted position. Another story, concerning Pope Gregory the Great (A.D. 540–604), claimed that just by staring at those hideous works of art, the saintly man caused the heads and limbs of various statues to shake and fall to the ground, shattering them into many pieces.

Terms such as “mad,” “laughable,” “loathsome,” “disgusting,” “abhorrent,” “wicked,” and “ignorant” were used to legitimize the zeal with which the Christians condemned to destruction thousands of statues. If the demolition of a huge statue proved too difficult, ground burial was recommended. The decimation that Western art suffered during those fanatical and puritanical years of Christian righteousness was immense. The proof is that the only statue that survived the great campaign of destruction that took place in Rome was that of Marcus Aurelius, which the Christians erroneously took as a depiction of Constantine.

The fear that by seducing the viewer, sculptures could become blasphemous idols always remained a concern among the Christians. After all, the pious Christians asked themselves, wasn’t disguise what Satan so often used to enslave his human victims? Addressing the argument, Christian theologians had no doubt: if not closely monitored by the church, nothing could have been more dangerous than an art that appealed to the seductive power of false beauty.

The famous statue of Marcus Aurelius was spared only because he was mistaken for Constantine, the first Christian emperor.

Further articulating the argument, Clement of Alexandria contended that the greatest risk that man incurred when he crafted copies of reality was to fall into the prideful belief that he could somehow compete with God’s creative talent.

How deeply those feelings resonated is proven by the total lack of ego that characterized the anonymity of the medieval artists. Art, in those profoundly religious times, was considered a collective effort: a tribute to God that categorically excluded the praise of any single artist. The medieval craftsman thought of himself not as an independent creator but simply as an artisan, the fashioner of images whose symbolism and style completely depended on the religious dogma decreed by the ecclesiastical authorities.

Because most paintings from that time have disappeared, the only way for us to see how the Christians of the first centuries developed their visual language is through the mosaics that best withstood the ravages of time. The Greeks and the Romans had mostly used mosaics for surfaces that would have been unsuitable for paintings, such as floors or the inside of fountains. Although a new use of mosaics had developed in the late empire, it was mainly with Christianity that the technique reached its climax, also thanks to the influence of Byzantine art. Mosaics were made of a multitude of little cubic stones, called tesserae, whose color, brilliance, and iridescence were enhanced by the addition of pieces of glass masterfully tilted at different angles. Intensified by the flickering light of the candles that illuminated churches, the dazzling sparks produced by the irregular refractions of color and light gave a transcendental quality to those glow-saturated forms. Overwhelmed by the dematerialized magic of the vision, the spectator would have been led to perceive, in those images, the intangible world of the spirit.

The mosaic in the apse of the Church of Santa Pudenziana in Rome, executed toward the end of the fifth century, is a good example of the confidence that the church acquired once it morphed from a small, persecuted set of devotees to a large and influential institution enjoying a position of full prominence within society.

Instead of a young shepherd placed in a simple, pastoral setting, what is presented here is a bearded and mature Christ whose authority has been raised to an imperial status by means of iconographic association—from the gravitas of His expression, also evocative of the intense look of a philosopher, to the halo that shines behind His head, to the jewel-studded throne that elevates Him above the apostles clothed with white togas, just like senators of ancient Roman times. In a position of prominence, Peter and Paul are crowned by two women with laurel wreaths.

Behind the figures, an encircling wall defines the perimeter of a city that looks like Rome but in reality is the celestial Jerusalem. Above, as if emerging from the sky that surrounds the hill of Golgotha, we see the symbolic representations of the four evangelists, portrayed as mysterious creatures: a winged man (Matthew), a lion (Mark), an ox (Luke), and an eagle (John). Derived from the visionary prophecy of Ezekiel and from the Apocalypse, the images are used to represent the evangelists as portentous figures endowed with the gift of divine prophecy. Within that symbolic representation, the message of Christ is evoked over and over: the winged man indicates Christ’s incarnation, the lion His majesty, the ox His sacrifice, the eagle His ascension.

The mosaic of the apse of the Church of Santa Pudenziana in Rome, fifth century

In a popular passage by Augustine, John is described as follows: “John…soars like an eagle above the clouds of human weakness, and gazes upon the light of permanent truth with the keenest and steadiest eyes of the heart.” In ancient folktales, the eagle was believed to be a magical bird capable of flying as high as the sun, at whose light it could directly stare with its powerful eyes. Through the Christianization of the myth, the eagle became a perfect equivalent of John’s prophetic capacity to look, deeper and stronger than anyone else, into the blazing light of God’s mystery.

In the fifth-century mosaics in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, the use of art as a thought-provoking instrument of meditation finds particularly interesting solutions. See, for example, the scene of the Nativity.

Choosing the abstraction of symbolism over a factual narrative, the mosaic presents Jesus not as a baby resting in a manger but as a small adult sitting like a king on a triumphal throne decorated with a great abundance of precious gems. Shining behind the throne is the star of Bethlehem, surrounded by four angels dressed in white. To the left of Christ, on an elevated throne, the figure of Mary is portrayed as a queen mother proudly looking at her royal son. The sumptuously dressed figures approaching from the right represent the Magi bringing presents to the divine baby.

The lack of realism and factual chronology was used to suggest that the advent of Christ was to be considered not a transient moment that had occurred once in time but an eternal miracle happening, each time anew, in the heart of the true believer, as Gregory of Nyssa in the fourth century wrote in his treatise De virginitate: “What happens to the immaculate Virgin, when the divinity shined through her virginity, happens to each soul that spiritually delivers Christ.”

The disregard of the temporal dimension is echoed in the incongruous depiction of space, where the proportion between the figures and the environment is consciously altered to stress a vision that is metaphysical rather than realistic and spatially coherent—a vision that addresses the “eyes of the spirit” rather than the “eyes of the flesh,” as Paul indicated in 2 Corinthians 4:18, “For the things which are seen are temporal; but the things which are not seen are eternal.”

The Nativity, as rendered in a fifth-century mosaic in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome

One of the most striking techniques used by the early Christians to express the ineffable nature of the divine was the reverse perspective. An example of reverse perspective is contained in the scene representing Abraham and Sarah (also in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, in Rome) offering a meal to the three mysterious guests who, as the upper register reveals, are personifications of the divine (Genesis 18:1–8).

According to the rules of perspective, which were known since classical times, the frontal line of a depicted object is always longer than the back one. The reverse perspective that the mosaic adopts (with the frontal line shorter than the back one) completely changes that dynamic: instead of receding backward toward the wall, the image extends forward as if reaching toward the viewer. As a result, the viewer gets the impression that he or she has suddenly become the object rather than the subject of observation. The aim of that reversal was to give the Christian viewer the impression that he or she was looked upon by the sacred images and not vice versa.

Abraham and Sarah and the three mysterious guests, rendered in reverse perspective in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore Credit 7

What the image essentially demanded was a correspondence: an invitation to enter into an encounter/dialogue with the divine. As an ongoing conversation with God, faith also involved a process of soul-searching and self-exploration—that particular conversion of attention that occurred when, reawakened by the message of the divine, the individual returned to contemplate the inner meaning of life and self.

LATIN WEST VERSUS GREEK EAST

As we have seen, the turmoil that shook Europe gained particular momentum between the fourth and the fifth centuries, when, in order to flee the violent Huns coming from the East, many barbarian tribes migrated toward the West. The Goths, who were divided between Visigoths and Ostrogoths, invaded Italy and Spain; the Vandals took over northern Africa and southern Spain (the name “Andalusia” was initially “Vandalusia”); the Franks and the Burgundians (from which derives the regional name of Burgundy) invaded Gaul, modern France, while the Anglo-Saxons settled in Britain in the fifth century.

The moment that sealed the end of the Western Empire occurred in A.D. 476, when the barbarian Odoacer, a Germanic soldier serving in the Roman army, forced the abdication of the last Roman emperor, Romolo Augustolo. To criticize the rough ways of the barbarians and their lack of appreciation of Roman culture and law, many writers of the time described them with terms more suited to animals than humans, like the poet Prudentius (348–ca. 413) did when he wrote, “But Romans and barbarians stand as far apart as biped from quadruped.”

Some barbarian habits contributed to those derogatory views. The Huns, for example, spent so much time on the backs of horses that they were seen as strange creatures almost fused with the animals they rode. The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus reported that riding was also used by the Huns for preparing the raw meat they ate, which they made tender by placing it under their rears tightly glued to the saddle!

Such rough portrayals ended up giving all barbarians a similar reputation. In reality, they were not all the same: if the brutal Huns were principally interested in raids and looting, others, like the Ostrogoths, felt a profound sense of reverence toward Rome. Theodoric, king of the Ostrogoths, who got rid of the German chieftain Odoacer and ruled Italy from Ravenna, expressed his profound admiration of Roman civilization when he declared to the Eastern emperor Zeno that he wanted to make his kingdom “a copy of yours without any rivalry.”

Theodoric’s aspiration was to become a custodian of what was left of the Western Empire (which, at that point, only included the Italian territories) and also a promoter of the cultural process of reconciliation that, he hoped, would have taken place between Ostrogoths and Romans. To show his peaceful intentions, Theodoric ordered that only one-third of the occupied territories be assigned to the Ostrogoths, while the rest of the land was to be left under the control of its previous owners. Theodoric also passed laws that forbade the destruction of Roman monuments, which he made sure to preserve by assigning money to their maintenance and restoration.

Like other barbarians, the Goths, early on, had been converted to Arianism by an apostle by the name of Ulfilas (Arianism was the Christian dissident sect that, as we have seen, the Council of Nicaea had declared heretical). Despite that religious difference, Theodoric continued to assure freedom to all Christians and to the Jews, whom he protected against all acts of harassment. As an admirer of Rome, Theodoric often surrounded himself with Roman advisers. Among them was the philosopher Boethius (ca. A.D. 475–524), whose contribution to culture consisted of a number of important translations of major Greek authors.

During the heyday of the Roman Empire, all educated people were bilingual, meaning that besides Latin they also spoke Greek—the language used in the Eastern provinces of the empire from where the Romans had gained access to Hellenistic philosophy, poetry, and literature. As education disappeared amid the chaos produced by the barbarian invasion, the Greek language was also forgotten. The reason Boethius is considered so important is that, being one of the very last intellectuals who still had knowledge of the Greek language, he was able to provide to the West the Latin translation of important Greek texts by authors such as Euclid, Archimedes, and Ptolemy that otherwise would have been forgotten. Among the works that Boethius saved from oblivion was Aristotle’s Organon, which included six treatises on logic. That work remained the only Latin source of the Greek philosopher until the cultural revival that took place in Europe between the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries.

The relation between the barbarian king and the Roman emperor dramatically deteriorated when the new Byzantine ruler, Justin I, abandoning the tolerant policy of his predecessor, enforced laws against all dissenting sects of Christianity, Arianism included. As a result, Theodoric became increasingly suspicious about a Byzantine conspiracy aimed at removing him from the Italian territories he controlled. The most prominent victim of that sudden turn of events was Boethius, who, unjustly accused of treason, was imprisoned for one year and eventually killed. In the book he wrote in prison, The Consolation of Philosophy, Boethius imagines a fictional dialogue between himself and Lady Philosophy. After talking about the randomness of Fortune, Lady Philosophy, in a way that appears to be a blend of Platonism and Stoicism, reminds Boethius that consolation can be found only in the permanence of virtue and in the beauty that the mind finds in its intellectual pursuits. Although religion is not directly mentioned, the book gained the admiration of many future generations of Christian thinkers because it showed that the Platonic ideas could be harmoniously linked with the principles of Christianity.

The years that followed left little hope for a reconciliation between Goths and Byzantines. In 535, the new emperor, Justinian (to whom we will return more extensively later), determined to reclaim the western territories of the old Roman Empire, initiated a war against the Goths that lasted eighteen disastrous years, during which the degradation of Italy reached a new, dramatic climax. The Byzantines came out of the conflict victorious. But when, fifteen years later, a new wave of tough and determined barbarians called Lombards or Longobards descended from Pannonia (modern Hungary), the Byzantines were forced to retreat toward the south, leaving control of northern Italy to the Lombard occupants, who kept their rule for the next two hundred years. (The Italian region called Lombardy derives its name from the Lombard barbarians.)

The worst consequence of those violent years was the collapse of cities and the destruction of farmlands, which caused famine, poverty, disease, and the consequent decrease of the overall population of Europe. As the great network of Roman roads fell into disrepair, commerce and trade came to a halt, as did culture and the exchange of ideas and traditions. While wilderness reclaimed large pieces of land once tamed by human work and ingenuity, the West turned into a loose conglomerate of small and self-sufficient villages isolated from one another, while the remains of Roman theaters, baths, arenas, aqueducts, temples, and bridges gradually crumbled amid the indifference of an ever-increasing poor and ignorant population.

In 543, a devastating plague arriving from the East ravaged even further the blighted condition that so many suffered. Like the wild animals that prowled in the darkness, the constant proximity of death filled the minds of people with fear, superstition, and nightmare visions. Pope Gregory I mourned in dismay, “What remains that is pleasant in the world? Everywhere we look we see pain, everywhere we hear cries. Cities are destroyed, the fortified places are ruined, the land abandoned and left to solitude. Few people are left in the countryside and the cities.”

What Augustine predicted seemed to have come true: human sin had provoked the fury of God, precipitating the final destruction of the world. “Mundus senescit,” prophets of doom cried, meaning that the world, having grown old, was drawing closer and closer to its last and final chapter.

In view of that fast-approaching end, religious preachers advocated the need to repent while committing their souls to the only possible means of salvation, the church that Saint Ambrose, in the fourth century, had described as follows: “Amid the agitations of the world, the Church remains unmoved; the waves cannot shake her. While around her everything is in a horrible chaos, she offers to all the shipwrecked a tranquil port where they will find safety.”

In those years of uncertainty and confusion, the image of the church floating like a safe ark above the deluge of misery brought a great amount of hope and consolation—at a spiritual level but also at the practical one. Will Durant explains that because the barbarians knew very little of social and political organization, it was left to the church, the “Foster Mother of Civilization,” to assure some sort of stability and continuity in the functioning of society. The tasks that the church performed, especially through its provincial organizations presided over by bishops, included administrative functions, the management of churches and hospitals, the sponsorship of religious art, the organization of tribunals where the clerical representatives presided over judicial matters, and all sorts of charitable initiatives created to alleviate the difficult conditions of the less fortunate. Even if the mechanism might have been somehow rudimentary, during the most troubled years of the early Middle Ages the organization of the church remained the only institution capable of keeping in place some level of order and civility among the disrupted communities of the old Roman Empire.

The church’s center of power was Rome. The bishop of Rome, the pope, was considered the successor of Saint Peter, whom Jesus called the “rock” upon which his church was to be built. Commenting on the symbolic transformation that Rome underwent, from persecutor to defender of Christianity and seat of the papacy, Richard Tarnas writes, “As the Roman Empire became Christian, Christianity became Roman.” As such, the church gradually became the ideal counterpart of the empire, while the Pax Romana was transformed into the triumph of the Pax Christiana.

Initially, the patriarchs, who were the bishops of the great cities of Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Rome, had been recognized as equal in authority. With Leo I (400–461), who assumed the title of pontifex maximus that had previously belonged to the emperor, the prestige of the Roman papacy grew to an unprecedented level. The event that lifted the reputation of the pope to a legendary status took place when Attila, the king of the Huns, having ravaged the northern city of Aquileia—Venice was founded by the fleeing population that took shelter on the islands of the nearby lagoon—began to proceed south toward Rome. Leo I, who, in legend and possibly fact, persuaded the ferocious Attila to give up his plan and withdraw from Italy, gave the papacy an authority that appeared to be, at the same time, religious, moral, and political.

The other pope who, like Leo, was granted a superlative was Gregory the Great, who during his pontificate (590–604) vastly contributed to the spreading of Christianity, which he accomplished by personally converting the Arian Lombards and by sending missionaries to Spain, Britain, and Ireland. Gregory, who like Leo came from an aristocratic family, abandoned all privileges to lead a life of humble austerity filled with penance, prayer, and the care of the poor and the needy. Gregory’s prolific activity as a writer included a manual called Pastoral Care, which applied the image of the Good Shepherd, traditionally associated with Christ, to all church representatives—namely, popes, bishops, and parish priests. Besides an important commentary on the book of Job, Gregory wrote the Dialogues, a collection of four books, of which the second one was entirely dedicated to the life of Saint Benedict, who, as we will see, was the founder of the first monastic rule in the West. Widely read, Gregory’s book was filled with fantastic stories of the medieval imagination: ghosts and evil spirits persistently looking for ways to gain control of the human soul, amid a great variety of wondrous miracles—holy men rejecting Satan with the sign of the cross, or healing the sick using a holy object, or moving rocks with the simple power of prayer. Gregory was also the protagonist of many popular medieval legends. One of them took place during the plague that had devastated the city of Rome. When Gregory, the legend reported, saw the archangel Michael putting away his sword on top of Hadrian’s mausoleum, he understood that the plague had finally come to an end. The statue of an angel on top of the mausoleum, which from then on was renamed Castel Sant’Angelo, evokes to this day the wondrous magic of Gregory’s time.

Gregory made a history-shaping claim when he affirmed that the pope, as a direct successor of Saint Peter, held a primary authority within the Christian world. The assertion could be compared to a declaration of independence of the Western Church from its Eastern counterpart, which was under the direct control of the emperor, who, in a way that was reminiscent of Roman imperial practices, arrogated to himself a power that was secular and religious at the same time. Just as in Constantine’s time, the argument used by the Byzantine emperor was that he was directly anointed by God as His vicar and representative on earth. The aura of holiness that such status granted gave the emperor absolute power over state and church: it was the emperor who chose the chief officer of the Eastern Church, the patriarch, and it was the emperor who summoned councils, issued doctrinal edicts, and reviewed the liturgy.

After Constantine, Byzantium’s most ambitious emperor was Justinian (A.D. 482–565), who, as we have seen, sought to re-create the unity of the old empire. To do so, he waged war against the Goths in Italy, the Vandals in North Africa, and the Visigoths in southern Spain. The victorious outcome gained Justinian the title of “last Roman emperor.” The title is fitting also because Justinian was the last Eastern ruler to use Latin as the official language of the empire—a policy that was reversed by the emperor Heraclius (575–641), who asked to be called Basileus (“king” in Greek) rather than Augustus and decreed that Greek, the language used by the people, replace Latin as the official language of government.

During Justinian’s time, the multiethnic and multicultural Byzantium reached a population of almost one million. The wealth that the city enjoyed derived from its active port, whose mercantile activities reached as far as Africa and Asia. When silkworms, smuggled from China by two monks, were brought to Byzantium, the city became the capital of silk weaving: a prestigious and lucrative position that the city maintained until the disastrous events of the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

During his reign, Justinian dedicated himself to the aggrandizement and beautification of Byzantium, which he filled with palaces, porticoes, monuments, promenades, and public baths. His greatest accomplishment was the magnificent church of Hagia Sophia (Greek for “Holy Wisdom”), in which the Roman style was mixed with features clearly borrowed from Persia, like the gigantic dome supported by four arches springing from pillars placed at each corner of the rectangular base. Commenting on the engineering wonder that had made possible the creation of a dome 183 feet tall, the sixth-century historian Procopius exclaimed, “It does not appear to rest upon a solid foundation, but to cover the place beneath as though it were suspended from heaven by a fabled golden chain.”

With its silver throne reserved for the patriarch, Hagia Sophia was a tribute to the power of Christianity, but also to an emperor who aspired to give biblical proportions to his memory and legacy. Procopius wrote that when Justinian inaugurated the grandiose church, filled with glittering mosaics and its colorful marbles, he uttered with pride, “Solomon, I have outdone thee!”

Right opposite Hagia Sophia, across a big and open colonnaded forum, was the monumental palace of the emperor. In front of the palace stood a bronze-covered column almost as high as the dome of the church; on top of it stood the equestrian statue of Justinian holding a globe in his left hand, while his right one pointed toward the east to symbolize the never-setting glory of his power.

To strengthen the Christian identity of his empire, Justinian started a vigorous campaign of suppression of all remaining pagan practices. Those who did not undergo the compulsory ritual of baptism were punished with imprisonment, torture, and even death. To erase the most emblematic trace of the pagan past, the emperor ordered the closing of the famous Academy that Plato had founded nine hundred years earlier, and rededicated to Mary, the mother of Christ, the Athenian Parthenon.

Hagia Sophia, the emperor Justinian’s most magnificent and lasting achievement