The intermittent series of conflicts that England and France engaged in from 1337 to 1453 is known as the Hundred Years’ War. The conflict was sparked by the death of the last king of the French Capetian dynasty, Charles IV, who left no male children and therefore no direct heir to the throne. The closest relative with right of succession was the son of his sister: the fifteen-year-old king of England, Edward III. Alarmed by the prospect that an Englishman could become their master, the French nobility elected as ruler King Philip VI of the Valois dynasty. Edward III promptly opposed the decision, but when the French threatened him with the confiscation of English holdings in the southern part of France (what remained of the vast fief that the English had acquired in the twelfth century, through Eleanor of Aquitaine), Edward III was forced to back down and reluctantly recognize Philip VI as the new king of France.

Tensions reemerged when Philip VI, taking advantage of the war between England and Scotland, moved to take hold of the English possessions in southern France and also gain control of Flanders (present-day Belgium). In the end, disappointed England lost its French fief and was unable to annex Scotland to its domain. France’s success in regaining its territorial unity was curbed by its failed campaign against Flanders, which maintained its independence. Flanders’s prosperity greatly increased with the English conquest of Calais in 1347, which allowed a collaborative trade between the two countries: England shipped wool to Flanders, where it was processed into fine cloth that was then turned into highly profitable merchandise. (The women who spun the wool into yarns were called “spinsters.” The term came to be associated with unmarried women who had to work because they did not have husbands who could provide for them.)

As the countries of Europe were beginning to stabilize their boundaries and political identities, and also develop more competent secular institutions, a collision with the church became inevitable. A significant moment occurred at the beginning of the fourteenth century when the king of France, Philip IV, imposed heavy taxes on all French citizens, clergy included. The pope, who at that time was Boniface VIII, angrily protested, saying that members of the church could not be taxed without papal approval. To retaliate against the pope, Philip IV blocked all monetary contributions to the Roman papacy. The jubilee of 1300, which was proclaimed by Boniface VIII, was in great part prompted by the need to compensate, with the contributions provided by the pilgrims who flocked to Rome, for the considerable loss of money that the church suffered from its feud with France.*1

The tremendous success of the jubilee, which saw the arrival in Rome of 200,000 pilgrims, was linked to the pope’s promise that all those who made the pilgrimage to the sacred city would have their sins forgiven.

The quarrel between Boniface VIII and Philip IV reached a dramatic climax when the French king, rejecting the idea that the clergy was to be considered immune from secular law, allowed his courts to put on trial and imprison a French bishop. In response, Boniface VIII excommunicated the French king and promulgated the papal bull (or decree) Unam sanctam (1302), in which, with extravagant imperiousness, he proclaimed the absolute temporal and spiritual supremacy of the pope over all human beings, kings included. “Every human creature is subject to the Roman Pontiff,” he stated with finality.

In reaction to that extreme statement, the exasperated king of France attacked the pope with a scathing list of accusations, which included simony, heresy, and immorality. Subsequently, he dispatched to Anagni, in central Italy, where the pope resided, a group of royal emissaries who arrested Boniface and threw him in prison. After three days with no food or water, the pope was finally released. But the humiliating experience proved too harsh for a man close to seventy. Boniface VIII never recovered and died shortly after. The brief pontificate of Benedict XI was followed by a clash between Italian and French cardinals fighting for the election of their own candidate. Eventually, the French cardinals prevailed, and Clement V was elected pope in 1305. Because he feared a vendetta on the part of the Roman aristocracy, Clement V decided to transfer the papal Curia to Avignon, in the southeastern part of France.

The sixty-seven years in which the papacy resided in Avignon is known as the Babylonian captivity. As described in the Old Testament, the exile of the Jews in Babylon had earned the city a very negative reputation as a hotbed of depravity and sin. In Apocalypse, that reputation was revived once again to describe Rome as the “mother of harlots and abominations of the earth.” When the Curia left Rome, the appellation was repurposed to criticize the worldliness of the huge and luxurious court of Avignon, where the popes enjoyed a princely existence surrounded by a multitude of assistants and servants paid with the money collected from ecclesiastical taxation. After visiting Avignon, a Spanish prelate wrote, “Whenever I entered the chambers of the ecclesiastics of the papal court, I found brokers and clergy engaged in weighing and reckoning the money that lay in heaps before them….Wolves are in control of the Church, and feed on the blood of the Christian flock.” The biting rhetoric and scathing words that the fourteenth-century Italian poet Petrarch employed to criticize the church’s betrayal of its apostolic origin went even further. The church, Petrarch wrote, is

the impious Babylon, the hell on earth, the sink of vice, the sewer of the world. There is in it neither faith nor charity nor religion nor the fear of God….All the filth and wickedness of the world have run together here….Old men plunge hot and headlong into the arms of Venus; forgetting their age, dignity, and powers, they rush into every shame, as if all their glory consisted not in the cross of Christ but in feasting, drunkenness, and un-chastity….Fornication, incest, rape, adultery are the lascivious delights of the pontifical games.

It took the supplicant appeals of people like Saint Catherine of Siena (1347–1380) to finally persuade Gregory XI to bring the papal Curia back to Rome in 1377. But it was not a smooth transition: after the death of Gregory XI, the clash of interests between French and Italian cardinals caused the election of a pope in Rome and a so-called antipope in Avignon. At one point the rift, which is known as the Great Schism, produced as many as three popes, each denouncing as invalid the appointment of the others.

Among the widespread criticism that the monarchical attitude of the church generated were many popular tales full of mockery toward the pope and the clergy. Authors such as Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375) and Geoffrey Chaucer (ca. 1340–1400) vividly captured in the Decameron and the Canterbury Tales the intensity of the anticlerical feelings that dominated the times. Among the amusing stories that Boccaccio wrote in his Decameron is the tale of a Jew by the name of Abraham. After having traveled to Rome, Abraham tells a friend that he found that the church dignitaries were “gluttons, winebibbers, and drunkards without exception, and that next to their lust they would rather attend to their bellies than to anything else, as though they were a pack of animals.” That terrible realization, Abraham concludes, firmly persuaded him to convert to Christianity. In response to the utter surprise of his friend, Abraham explains that the simple fact that Christianity has been able to survive despite all attempts of church dignitaries to destroy its reputation appears to him as a definite proof that it is a powerful religion with a mighty Holy Ghost as “foundation and support.”

The greatest threat that confronted the church in the fourteenth century came from dissident movements that, offended by the corrupted behavior of the papacy, preached a humble and apostolic faith based on an intimate relation with God that did not require the mediating intervention of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Among those movements, the two most influential were the one inspired by John Wycliffe (ca. 1320–1384) in England and the one led by Jan Hus (1369–1415) in Bohemia. Both men and their respective followers, the Lollards in England and the Hussites in Bohemia, took a firm position against the infractions committed by the church: the selling of indulgences, the laxity of clerics, and the papal meddling in secular and political affairs. Wycliffe rejected the pope’s claim that he was the vicar of God, arguing that the papal institution had been established by man, not God, and that the teaching of the Bible could be directly acquired without the intermediary help of priests. For that reason, he translated the Bible into English. After his death, the ecclesiastical authorities, concerned with his influence, condemned to destruction all the copies of Wycliffe’s Bible. The flames that destroyed piles of books also incinerated many people accused by the church of being heretics. Hus, who did not hesitate to publicly condemn the church for its moral depravity, its political ambition, and its indifference toward the needs of the poor, was accused of heresy. By condemning Hus to death and burning him at the stake, the church turned the Bohemian preacher into a hero and martyr with much greater influence in death than in life.

In 1347, the bubonic plague, also known as the Black Death, appeared in the West, carried by ships coming from the East. In only five years, twenty-five million people perished, one-third the overall population of Europe. The psychological scar left by the devastating epidemic caused the spreading of superstition, magic, and witchcraft, as well as the fanatical excesses of the flagellants who publicly whipped themselves as a way to expiate the sins that, they believed, had induced God to punish the world. Conspiracy theories were also fast to spread. As usual, the first to be accused were the Jews, who were charged with poisoning the water supplies in order to kill all Christians.

Yet, like a fire whose destruction ends up regenerating the soil, the dramatic loss of population that the plague caused ultimately benefited those who survived: the shortage of food that Europe had experienced the preceding century, due to the sharp increase in population, coupled with several years of adverse climate conditions, ceased to be a concern after the plague, while the diminished availability of people resulted in more job opportunities for a new generation of workers. As the demand for manpower grew, so did the leverage of a working class that now felt entitled to fight for better living conditions and wages. Class-based insurrections, such as the Jacquerie that occurred in France in 1358, the Peasants’ Revolt in England in 1381, and the revolt of the Ciompi or wool carders in Florence in 1378, were symptomatic of that gigantic shift in the attitudes and expectations of commoners and, in general, those belonging to the lower, working class. The cry for justice with which the poor confronted the abuses of the rich directly appealed to the values of Christianity that the English peasants, revolting in 1381, framed with these powerful words: “We are made men in the likeness of Christ, but you treat us like savage beasts.”

The events described above show that the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were certainly very turbulent times in the history of Europe. Yet despite the many setbacks, Europe had begun to undertake a course destined to provide significant improvements in the general well-being of all people.

THE ITALIAN CITY-STATES

After the eleventh-century emergence of the powerful maritime republics of Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa, and Venice, the Italian cities that began to experience a greater cultural development were those that, although nominally part of the German Empire, had been able to resist imperial and feudal control to become self-sufficient centers of industry and commerce. With the exception of Flanders and the Hanseatic towns, in northern Europe, the prosperity that those Italian cities enjoyed had no equal in the rest of Europe. That prosperity also rested on a wide range of accounting and banking techniques developed by Italian financiers, such as insurance contracts, credit, and double-entry bookkeeping. Lombard Street, in the financial district of London, owes its name to the Italian moneylenders who settled there in the thirteenth century.

The civic pride that the commercial middle class enjoyed, due to such successes, became one of the most prominent characteristics of those Italian municipalities, which were called communes because their government was based on the collaboration of assemblies formed by the representatives of the major guilds or trade unions, without any external interference from imperial and clerical control.*2

The freedom and independence that characterized those self-governing cities found an obvious comparison with the Greek city-states and especially the Roman Republic. In his book History of the Florentine People, the historian Leonardo Bruni (ca. 1370–1444) used classical references to law, order, and civic devotion to affirm that Florence was a place of justice where merit, rather than privilege, determined social status and where all citizens had an equal say in the management of the state. Contemporary scholars warn us not to take those optimistic claims too literally: in the Florentine Republic, as in the other Italian city-states, participation in government was limited to the members of the wealthy guilds to the exclusion of the less affluent citizens. In that sense, writes the historian John Larner, the equality that the humanists praised was a myth produced by a narrow class that had succeeded in equating its specific interest with the larger, common good. The oligarchic nature of Florence is confirmed by numbers: in a population of approximately 100,000, only 4,000 had the right to vote.

In Florence, the seven major guilds, which constituted the popolo grasso (the richest members of society), included Judges and Lawyers, Cloth and Wool Merchants, Doctors, Silk Weavers and Vendors, Furriers, Tanners, and, most important, Bankers. The lesser bourgeoisie, the popolo minuto, belonged to the minor guilds of Butchers, Cobblers, Blacksmiths, Locksmiths, Bakers, and Winemakers. The proletariat, which constituted the poorer strata of society, was mainly formed by peasants who had abandoned the countryside with the hope of finding better opportunities in the city but ended up performing the most menial work. What we should remember is that apart from a few interludes, like the Ciompi revolt mentioned earlier, political control in Florence remained firmly in the hands of the richest guilds. As the historian Alison Brown writes, “Apart from a few ‘radical interludes,’ as [the scholar Philip] Jones calls them, the policies of these communes remained conservative and restrictive, their outlook upper-class, not populist.”

The blatant discrepancy that separated reality from that idealistic narrative didn’t dim the citizens’ civic and political pride, as also shown by the many references to Roman architectural style with which they filled their urban environment. In his History of the Florentine People, Bruni, in a way that was evocative of Greek and Roman writers, asserted that the beauty of Florence revealed the nobility of spirit of its citizens.

In the past, the only structure that had dominated the landscape of the city was the cathedral. The relevance that grand and austere private buildings were now given, as well as the imposing presence of public town halls, reveals the enormous importance that the secular world had gained vis-à-vis the church. In Florence, the commanding presence of the massive Palazzo Vecchio was further enhanced by the nearby Loggia dei Lanzi: an open space framed by three wide arches topped by Corinthian capitals decorated by Agnolo Gaddi’s allegorical representation of the four cardinal virtues: Fortitude, Temperance, Justice, and Prudence. The space was built to display the statues whose symbolic meaning best conveyed the political ethos cherished by the city. Today the Loggia dei Lanzi contains masterpieces such as Perseus (with the severed head of the Medusa), executed by Benvenuto Cellini between 1545 and 1554, and Giambologna’s Hercules Beating the Centaur Nessus (1599). In 1353, the first mechanical clock, placed on the tower of the Palazzo Vecchio, secularized the sound of church bells that until that moment had marked the phases of the day. The precise measure that from then on the passing of the hours received gave an efficient but also accelerated quality to time: in a city so committed to business, time became money and as such a precious commodity that could not be wasted.

The paintings that Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290–1348) was hired to execute in the Palazzo Pubblico (town hall), which was the seat of Siena’s republican government, are helpful in understanding the pride that animated the republican spirit of the Italian city-states. Like Florence, the commune of Siena had become a rich economic enterprise: a city led by merchants and artisans who used art to commemorate their achievements and advertise the virtuous quality of their civic engagement. Lorenzetti’s four frescoes are an allegorical representation of the positive effects that Good Government had in the city and its surroundings, in contrast with the evil disunity produced by Bad Government (see this page).

The figure of the old man with a white beard, placed at the center of the first composition, is the allegorical personification of the Commune. Above his head are placed the three main theological virtues, Faith, Hope, and Charity, while at his side are the cardinal virtues of Temperance, Prudence, Fortitude, and Justice with two other figures representing Peace and Magnanimity. The figure on the right of the Commune, sitting on a throne, is Justice. Right below Justice is Concord, which is also the point of departure of a long cord held by a procession of twenty-four citizens (the representatives of the upper guilds that led the city government). The image symbolizes the spirit of collaboration that allowed the community to thrive, as shown in the portrait of the city buzzing with the activity of merchants, artisans, and labor workers. Against a background of imposing palaces, churches, towers, and shops, a dancing group of young and elegantly dressed women further enhances the harmony that exudes from that overall image of cheerful prosperity.

The frescoes of Lorenzetti in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena—allegories of the positive effects of Good Government

The bird’s-eye view of the Tuscan countryside, in the next image, delivers a similarly positive message: as in the city, Good Government assured safety and prosperity in the surrounding lands, as shown by the villas, the castles, and the rich abundance of the plowed fields. In stark opposition to Good Government, Bad Government is represented as a dark, satanic monster with horns and fangs accompanied by Tyranny, Greediness, Ambition, and Vanity.

The image of two little, naked children, placed at the center of the composition under the personification of the Commune, is a proud reminder of the Roman origin of Siena. The pedigree was used to validate the ethical link that connected Siena to the values of ancient Rome. Religion was not forgotten but rather fused with the concept of civic virtue that mixed Christian principles with the exemplary lessons of Rome’s heroic past.

A few years after Lorenzetti completed his work, the government of Siena asked Taddeo di Bartolo (ca. 1362–1422) to paint a cycle of frescoes, again for the town hall, dedicated to Roman republican heroes. A central inscription explained with these words the significance of those exemplary images: “Take Rome as your example if you wish to rule a thousand years; follow the common good and not selfish ends; and give just counsel like these men. If you only remain united, your power and fame will continue to grow as did that of the great people of Mars. Having subdued the world, they lost their liberty because they ceased to be united.”

Describing Lorenzetti’s frescoes, John Larner writes that they are a “document of singular importance” in that they highlight the contrast between past and present: whereas the city of medieval times was a random maze of tortuous streets and precarious houses, the commune was exalted as a model of rationality where beauty went hand in hand with efficiency and functionality. The need to trumpet, in such a forceful way, that greatness of the commune reflected the pride of an emerging bourgeoisie, which for centuries had been dismissed with contempt by the landed nobility as ignorant and vulgar nouveaux riches. The prejudice was reinforced by the church, which claimed that the pursuit of wealth was a corrupting practice because it encouraged self-promotion and the excessive attachment to luxury and riches. In contrast with that view, what the merchants who led the government of the commune were eager to convey was that their rule produced not simply wealth but also progress, peace, collaboration, justice, beauty, and civilization.

But the blissful atmosphere of communal happiness celebrated in Lorenzetti’s paintings didn’t fully reflect the actual events of history: with constant infighting among competing wealthy families and rivalries with neighboring powers, the city-states were perennially rocked by tremors that were as constant and unpredictable as the moods of a live volcano. In that sense, more than altruism and cooperation what prevailed in the Italian city-states was ambition and competition—the passionate desire to surpass and outshine all competing rivals in the quest for money, power, fame, and recognition. Contrary to the feudal Middle Ages, which were all about the solid immobility of authority and tradition, humanism and the Renaissance were all about the forward dynamic of an entrepreneurial and feisty mercantile society.

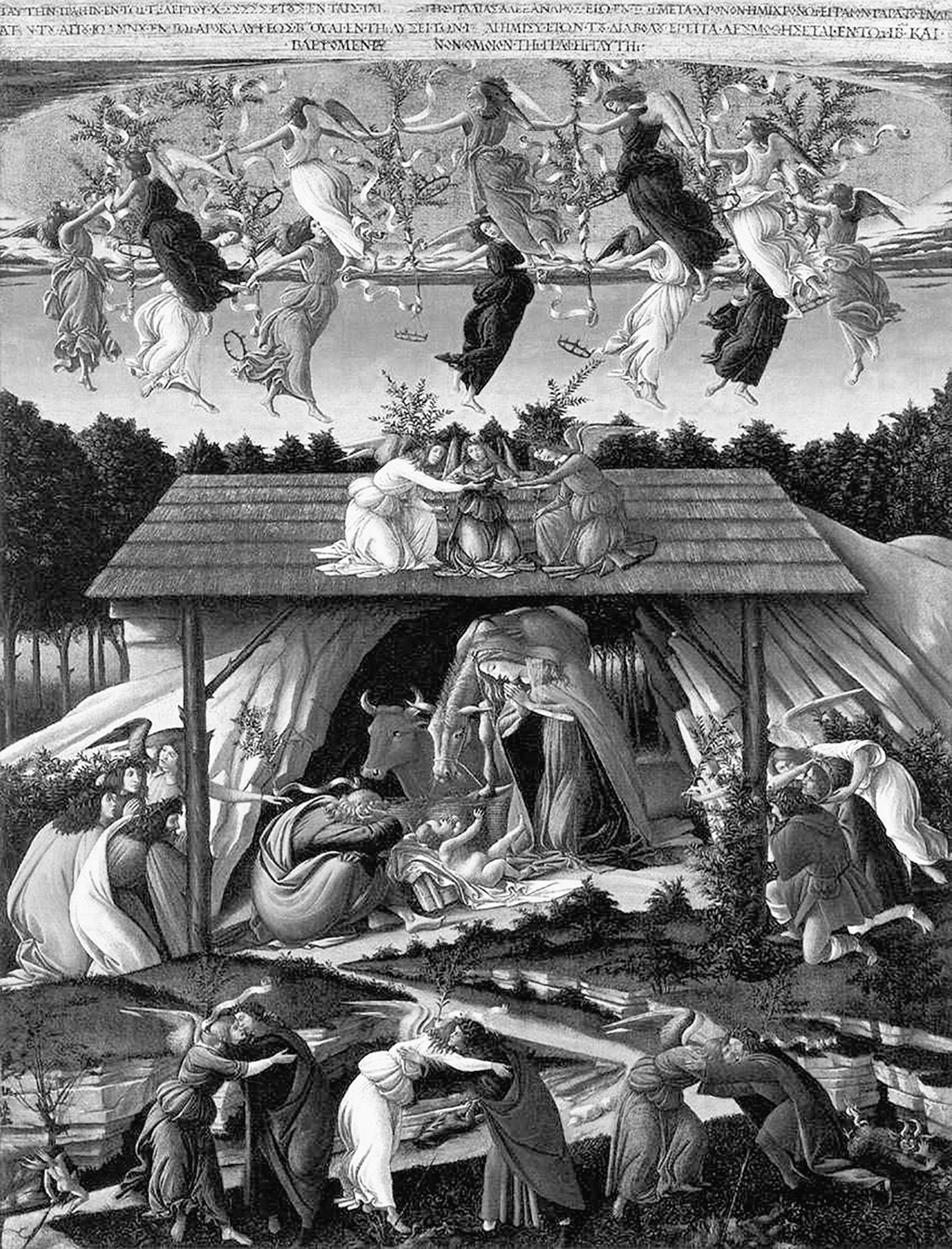

In time, the tug-of-war between the richest families led to the demise of the communes and the birth of the signorie, from signore, to indicate that a single ruler was in charge of the city-state. Among those ruling families were the Visconti in Milan, the Gonzaga in Mantua, the Bentivoglio in Bologna, the Montefeltro in Urbino, the Este in Ferrara, the Scaligeri in Verona, and most famously the Medici in Florence. As in previous times, martial activity remained a constant feature of the signorie, with bigger cities constantly striving to annex and control smaller ones. Florence, for example, ruled Pisa and Pistoia, Venice Padua and Verona, Milan Pavia and Lodi, and so on. The trait that most persistently seemed to link all those powerful rulers was the tenacity with which they worked at imitating, in manner and style, the snobbish attitudes that had belonged to the landed aristocracy. The enormous amount of art that the Renaissance produced was sponsored by a merchant class eager to use the splendor of the city as a testimony of its own greatness. In pursuit of that purpose, the court of Milan sponsored artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Bramante, while Mantua boasted Andrea Mantegna, Pietro Perugino, and Correggio, and Florence patronized Donatello, Brunelleschi, Verrocchio, Ghirlandaio, and Botticelli, to mention just a few.

The term “Renaissance,” which is based on the French word meaning “rebirth,” was first used by the French historian Jules Michelet in 1858. Shortly after, the term was given further popularity by the nineteenth-century Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, author of The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. Burckhardt’s claim that the Renaissance was a sudden explosion of talent and creativity after centuries of dull and ignorant darkness was largely influenced by fifteenth- and sixteenth-century authors—people like the philosopher Marsilio Ficino and the painter and author Giorgio Vasari, who in his 1550 book, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, described as “golden” the time that Florence was experiencing under the rule of the Medici family. Even if no one can deny the excellence and originality of the many artists whom Vasari’s book takes into consideration, to describe their activity as symptomatic of the birth of a new, free, and self-determined man, as Burckhardt and other scholars of his generation suggested, can be deceiving in that it does not take into consideration the fact that what those artists produced was not so much the expression of their free creativity, but the visual translation of what their rich patrons demanded. Furthermore, as many contemporary critics underline, the Renaissance was not a widespread phenomenon but the expression of a small and wealthy elite eager to declare its superiority in relation to an era (the Middle Ages) that they discarded as nothing more than an insignificant parenthesis placed in the middle of two extraordinary times: the classical past and the Renaissance.

In contrast with those views, modern scholars argue that the Renaissance did not burst out of nothing but was the result of a long process of maturation (which, as we have seen, started in the twelfth century), without which the new era would never have borne its fruits.

Bearing this in mind, we will continue to use the practical term “humanism” to name the first part of the period called the Renaissance, whose overall dates are generally set between 1300 and 1550. As we will see, humanism was characterized by scholars who, following the example set by Petrarch, crisscrossed Europe in search of old manuscripts. From the lesson of the illustrious forebears that those old manuscripts brought to light, the humanists derived new models with which to improve art and also the basic principles concerning politics, ethics, and philosophy. The discussion that follows will focus on (a) the literary quality that humanism assumed under the influence of Petrarch and (b) the change that occurred a generation later, when, with the rediscovery of authors such as Livy and Cicero, writers and intellectuals switched their interest from literature to politics.

PETRARCH’S LITERARY HUMANISM

After Thomas Aquinas, the Scholastic method of learning with its rigorous, logical analysis had slowly exhausted itself by turning into an ever more abstract and arid intellectual exercise. (The common question “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?” is meant to mock the extremes of Scholastic inquiry.) The cultural revival that followed the waning of Scholasticism was called humanism. The term “humanism” is a nineteenth-century expression used to describe a new generation of scholars who, placing aside the concerns of theology and metaphysics, passionately dedicated themselves to the revival of what Bruni called the studia humanitatis, meaning the study of endeavors, specifically human, whose qualities made them valuable for the forward progress of civilization.

The beginning of humanism coincides with the work of two major Tuscan authors: Giovanni Boccaccio and Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374). Boccaccio’s most famous work was the collection of novellas, written in Italian vernacular, called the Decameron. The protagonists of the Decameron are a group of seven young women and three young men who leave Florence for the countryside when the city is struck by the plague. The stories that they tell during ten days of their sojourn constitute the one hundred tales of the Decameron. Boccaccio’s tendency to focus on everyday life, his irony, his loose morality, and the witty and irreverent way with which he addresses the church and the clergy show the secularized mentality that the new urban culture had introduced.

After the Decameron, the other influential book by Boccaccio is the Genealogy of the Pagan Gods, a compendium of pagan mythology that became a rich source of inspiration for writers and visual artists eager to find fresh images and ideas with which to replace the by then stale language of the old Christian devotion.

Petrarch, who is commonly considered the father of humanism, was born in Arezzo in Tuscany in 1304. Compelled by his father, he initially studied law in Montpellier and Bologna. But he soon abandoned those studies to dedicate himself to his literary passion, in particular the study of the classics. Petrarch’s father, who was a very traditional man, did not take lightly his son’s change of heart. To express his disdain toward pagan culture, he burned many of what he considered his son’s “heretical books.” Undeterred, Petrarch continued to follow his literary calling for the rest of his life. Most of his literary activity took place in Avignon, where he held different clerical positions at the papal court, and then in the Vaucluse in Provence, where he pursued his work under the patronage of rich sponsors. The echo of the troubadours who had once thrived in Provence is strongly audible in the Neoplatonic celebration of love and beauty that Petrarch expresses in his verses.

Because he was a fervent admirer of the classics, Petrarch traveled all over Europe in search of old manuscripts kept in remote monastic libraries. Cicero’s oration called Pro Archia and his Letters to Atticus, which Petrarch found in Liège, were among his most valuable discoveries. Petrarch, who died in Arquà, in the Veneto region, in 1374, left his vast collection of books to the city of Venice.

Petrarch’s passion for antiquity was so vivid that he kept up an imaginary conversation with his favorite classical authors—people like Cicero, Virgil, Homer, and Horace—to whom he wrote fictional letters. Petrarch was a devout Christian, but that did not prevent him from criticizing the cultural poverty that, in his view, had dominated the Christian Middle Ages: an age, he claimed, that was responsible for the gross distortion of the classical heritage that the Christians had labeled sinful and dark because not illuminated by the grace of God. Petrarch used the same attribute to condemn as “dark” the Middle Ages, saying that it had been a period dominated by ignorance, prejudice, and superstition. The definition of the Renaissance as a rebirth derived in large part from Petrarch’s belief that the cultural achievements that the classical era had bequeathed humanity were a precious reservoir of wisdom that could have helped, rather than hindered, the progression of the Christian world.

Dante had advocated the re-creation of the Holy Roman Empire, with the emperor in charge of temporal matters and the pope of spiritual ones. Petrarch, who lived in an epoch when the ideal of the empire was rapidly declining, sided with Cicero and Livy, who praised instead the virtues of the Roman Republic. To those values Petrarch dedicated his books Africa (about Scipio Africanus, the famous Roman general who defeated Hannibal during the Punic War) and De viris illustribus (On illustrious men): a book, inspired by Livy, that was an attempt to establish a continuity between pagan and Christian wisdom by pairing exemplary characters equally drawn from ancient history, mythology, and the Old Testament.

Petrarch’s fame was so great that in 1340 he was asked to choose between Paris and Rome as his favored setting for a ceremony to award him the title of poet laureate (a recognition comparable to the prestige of today’s Nobel Prize). Petrarch, who chose Rome, was crowned on the Capitol, April 8, 1341. On that occasion, he visited the Forum, the Colosseum, and other ancient ruins and lamented the indifference that had allowed such majestic splendor to rot in dirt and neglect. His hope to revive the ancient romanitas made him welcome, a few years later, the rise of a flamboyant character, named Cola di Rienzo, who used a skillful rhetoric to advocate the restoration of Rome’s antique glory. Touched by that nostalgic dream, the Roman populace, who just a few years before had seen the papacy move to Avignon, put their trust in that self-proclaimed “tribune of the people” and did not oppose the coup d’état that he staged to take control of the city. For a short period of time, Cola’s rule maintained a relative level of stability, but when the delusional promoter of that alleged revolution, theatrically dressed with a white toga trimmed in gold, declared that as a restorer of the Holy Roman Empire he had the authority to free all the Italian cities from their rulers and then become emperor thanks to their support, people understood that they had fallen for a charlatan and chased him out of the city.

Despite his many talents, Petrarch’s incapacity to recognize Cola’s shortcomings is revealing of his lack of acuity when it came to practical and political matters. Petrarch might have been aware of that: except for his short-lived enthusiasm for Cola, he never got involved in politics, praising instead the value of a solitary life. Petrarch was a moralist who bitterly criticized the corruption and hypocrisy of his times but never questioned his own aristocratic refusal to engage in the political arena nor his opportunistic association with wealthy patrons for purely convenient and self-serving purposes. By his own admission, his greatest concern was his own reputation. He was unapologetic about it: true genius, he believed, deserved recognition and the imperishable glory of eternal fame.

Petrarch was a bundle of contradictions. Like Dante, he was a man torn between the excitement for the new and the fear of change that his time was experiencing. The poet laureate was at his best when, in the Canzoniere (Book of songs, also known as Rime Sparse, “scattered verses”), as his vernacular collection of poems was called, he acknowledged those fears and hesitations and confessed the doubts that tormented his Christian consciousness. Similar to the tradition of the Dolce Stil Novo, from which Dante also had emerged, Petrarch modeled his Canzoniere on the Neoplatonic fashion of describing love as a purely mental exercise: because the woman remains unapproachable, the lover withdraws to contemplate within the image of beauty created by the power of his own imagination. His idealized love object, Laura, who like Beatrice is married to someone else and dies at a very young age, is a symbol of beauty and purity rather than a real woman. The male speaker, who laments her perennial absence, uses that absence as a springboard of poetic inspiration. Petrarch reminds us of that connection by persistently associating the name Laura with the lauro, or “laurel”: the tree of poetry and eternal fame.

In the first sonnet of the Canzoniere, Petrarch directly addresses his audience to affirm that the “scattered verses” they are about to hear represent an “error” of youth: the futile hopes and sorrows of a painful love experience for which the poet desires to receive pity and forgiveness. The beginning of the Canzoniere is disconcerting: Why does the poet ask us to listen to his verses if he is the first to reject, as an illusion, the value of his passion and that of his poetry? Rather than providing an answer, the sonnet that follows further confuses the reader’s expectations. His first encounter with the beloved, Petrarch says, occurred the day of Christ’s death (Good Friday), when the sun withdrew its rays from the world. The darkening of the scene audaciously acknowledges the sinful violation implicit in the amorous experience: the passion that the poet describes in his verses is placed in direct opposition to the all-absorbing devotion that a Christian was expected to pursue. That ambiguous tone is maintained throughout the Canzoniere: while a melodious style delivers images of Laura that are as transfixing as heavenly visions, Petrarch continues to remind himself, and the reader, of the danger that the poetic illusion poses to the spiritual clarity required by religious engagement.

Unlike the fictional Beatrice, whom Dante transforms into a celestial vessel of salvation, Petrarch’s Laura represents a poetry that, like the laurel she evokes, remains inextricably rooted within the poet’s human and secular reality. That does not mean that Petrarch’s verses aim at describing a real woman. On the contrary, the image of Laura that Petrarch conjures up from the most delicate aspects of nature (a murmuring brook, a whispering breeze, a perfumed shower of flowers) is an enchanting yet completely ephemeral symbol of beauty that is abstract and poetic rather than tangible and concrete. What fascinated the author of the Canzoniere was not an actual woman but the visionary power of his own creative imagination, explored from an angle that was emotional, artistic, and psychological rather than spiritual and religious.

The fact that the idealized image of the woman conveyed by poetry did not necessarily improve the way women were regarded in real life emerges in a letter where Petrarch, writing to a friend, uses these chauvinistic words to describe his feelings toward the opposite sex: “The woman is the embodiment of the devil, the enemy of peace, the cause of impatience, the source of discords and disputes, and man should try to avoid her if he wants to find tranquility in life.”

The moral dilemma that in the Canzoniere divides the poet’s earthly and spiritual concerns is explored by Petrarch in a prose book called the Secretum, which is a fictional dialogue between himself and Augustine—the personification of the Christian dogma that Petrarch fears and respects, even when he desperately tries to bend the rigid rules of its dictate to grant a greater legitimacy to his passion and ambition. To convince Augustine that his literary pursuit is not inappropriate, Petrarch says that as a muse of love and poetry Laura has filled his mind with lofty thoughts and virtuous desires. Augustine remains untouched by the poet’s argument: as an inflexible judge and a severe alter ego, he tells Petrarch that all those who prove incapable of leaving behind the cupiditas, or desire for earthly attachments (beauty, poetry, and fame), fall into error, because nothing besides God is worthy of human interest and attention.

After a long discussion, Petrarch is forced to concede that Augustine is right. The dialogue ends with the poet promising Augustine that he will abandon his illicit pursuit, but not before the completion of his Canzoniere, on which he had pinned his hope for eternal fame.

The religious anguish that torments Petrarch is completely medieval, but the stubbornness with which, despite his sense of guilt, he refuses to give up the devotion toward his literary endeavor announces the beginning of a new era in which religion is not so much dismissed as reshaped into a faith less austere and dogmatic; in other words, a faith capable of accepting man’s accomplishments as concordant with rather than antithetical to the values of Christianity.

Petrarch’s dedication to the classics shows the unorthodox approach he maintained in regard to culture. Art, for Petrarch, was an expression of freedom and, as such, deserved a respect that was to remain free from prejudiced views dictated by doctrine or ideology. Eugenio Garin writes that Petrarch and his fellow humanists truly “discovered” the classics not just because they brought to light old manuscripts buried in dusty and secluded monasteries but because they learned to appreciate them as unique expressions of singular talents belonging to a specific historical time. Rabanus Maurus, who lived between the ninth and the tenth centuries, had characterized the medieval handling of past knowledge this way: “When we find something useful we convert it to our faith,” and when we find “superfluous things, that concern the idols, love or the preoccupation with things of this world, we eliminate them.”

In total contrast with the medieval habit of channeling all past accomplishments within the narrow parameters fixed by Christianity, the humanists were the first scholars to teach that the classics had to be appreciated for their own unique merits, free from the shackles imposed upon them by ideology and religion.

Following the moral imperative of rescuing the classics, many humanistic scholars spent years combing all corners of Europe in search of manuscripts “held captive” (to use the expression of the humanist scholar Poggio Bracciolini) in monastic and cathedral libraries. The great number of manuscripts that were assembled, of authors such as Cicero, Tacitus, Seneca, Ovid, Lucretius, and Vitruvius, were used by the humanists to undertake a major work of philological restoration aimed at bringing back the original integrity of the texts. At the core of the humanistic approach was the view that, as in classical time, virtue was to be expressed in action rather than contemplation and that education was essential to assure man’s moral and intellectual maturation, without which the stability of society could not be guaranteed.

POLITICAL HUMANISM

After Petrarch, the majority of humanists abandoned the poet’s solitary striving toward literary perfection to emphasize matters that were more specifically related to the civic and political life of the city-state. Mostly inspired by the rediscovery of Cicero, the creed that animated this new generation of scholars was that the highest and noblest way of life was the one placed at the service of the state. This mental attitude ushered in once again the secular belief that history was a process shaped and put in motion by human work and aspirations. Aristotle’s statement that “he who is not a citizen is not a man” was at the root of that conviction and with it the corollary belief that a free state was essential for the realization of man’s destiny as prime agent of civilization.

To promote the knowledge of the classics, Coluccio Salutati, who was chancellor of Florence from 1375 to 1406, persuaded the city government to invite the Byzantine scholar Manuel Chrysoloras to teach the Greek language in Florence. (Unlike Boccaccio, neither Dante nor Petrarch could master Greek.) The importance that Salutati and his followers attributed to Greek and Latin culture alike was based on the belief that the study of ancient authors was necessary to build man’s moral character, without which a just and strong society could not be created. The studia humanitatis, which replaced the medieval emphasis on the trivium and quadrivium, included rhetoric, eloquence, history, and moral philosophy: in other words, disciplines that had to do, primarily, with the moral and rational strengthening of the human personality for the sake of an active and engaged political existence. In a similar way, the term artes liberales (liberal arts), which was made complementary to the definition of studia humanitatis, indicated that culture assured the freedom of the human spirit. Eugenio Garin summarizes with these words the essence of that new mentality:

The humanistic culture that flourished in the cities of Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries manifested itself above all in the field of the moral disciplines by means of a new access to ancient authors. It took concrete shape in new educational methods practiced in the schools of grammar and rhetoric. It became a reality in the formation of a new class of administrators of the city-state to whom it offered more refined political techniques. It was used not only in order to compose more efficient official letters but also to formulate programs, to compose treaties and define ideals, to elaborate a conception of life and the meaning of man in society.

Despite the optimism that humanists placed in republican virtues, many communes were short-lived, soon replaced by the signorie.

Salutati’s confidence that as a civically engaged city Florence would have avoided the destiny of other city-states was put to the test during the clash with Milan, which had fallen under the rule of the Visconti family at the end of the thirteenth century. The power that the Visconti gained when they became sole rulers of the city made them similar to monarchs, but the fact that as businesspeople they lacked a proper title was often a source of profound insecurity. For that reason, the Visconti family paid 100,000 florins to the king of France to buy the title of dukes. The same thing was done by the Gonzaga, the ruling family of Mantua, who, having acquired the title of marquises in 1433, sported their right to wear the English royal livery, which featured proudly in an Arthurian fresco cycle they commissioned from the artist Pisanello.

Gian Galeazzo Visconti, who assumed full control of Milan after the brutal murder of his uncle with whom he had initially co-ruled, was an extremely ruthless and ambitious man, determined to extend the Milanese possessions throughout the northern territories of Italy. The official justification for that expansion was that Italy would have benefited by being unified under a single ruler. After conquering Padua, Verona, and Vicenza, Gian Galeazzo turned his interest toward Bologna and Florence. Fearing an imminent attack, Salutati rallied the patriotic spirit of the Florentines with a powerful speech that denounced the evils of tyranny. As the city, pressed by Salutati, prepared to resist the enemy’s attack, news arrived that Gian Galeazzo had suddenly fallen sick and died in 1402. Salutati chose not to diminish the symbolic importance of the moment: by praising the Florentines’ courageous determination to defend their liberty, the eloquent chancellor greatly contributed (just as Pericles had done so many centuries before) to the optimistic belief that against the threat of tyranny nothing was more powerful than people’s love for freedom and independence.

The historian Leonardo Bruni, who like Salutati was a passionate supporter of the republican system, believed that the example of social and political rectitude provided by Florence represented a universal principle valid for all of humanity. To understand how the humanists considered ideal a society that, in essence, was led by a small oligarchy of rich and influential families, we have to remember how still ingrained was the notion that the universe was a hierarchically ordered system. The metaphor most commonly applied to society was that it was comparable to the human body: a unity of different parts each contributing, in its own specific way, to the overall well-being of the organism. What differentiated the new era from the medieval past was social mobility: whereas in the Middle Ages class status was considered an unalterable trait inherited at birth, those in charge of the republic believed that they had gained access to government through skill, wit, and ingenuity. Discussing the positive effects produced by the republican system, Bruni wrote,

The hope of winning public honors and ascending is the same for all, provided they possess industry and natural gifts and lead a serious-minded and respected way of life….Whoever has these qualifications is thought to be of sufficiently noble birth to participate in the government of the republic….But now it is marvelous to see how powerful this access to public office, once it is offered to a free people, proves to be in awakening the talents of the citizens. For where men are given the hope of attaining honor in the state, they take courage and raise themselves to a higher plane; where they are deprived of that hope, they grow idle and lose their strength. Therefore, since such hope and opportunity are held out in our commonwealth, we need not be surprised that talent and industry distinguish themselves in the highest degree.

Bruni’s assertion that nobility was not a hereditary trait but an outcome of virtue and that competition within a free society was the best way to assure the blossoming of the human personality formed the core of an ideal that influenced political thinkers for many generations to come. In his Panegyric of the City of Florence, Bruni painted this idealized portrait of Florence and its people: “The men of Florence especially enjoy perfect freedom and are the greatest enemies of tyrants. So I believe that from its very founding Florence conceived such hatred for the destroyers of the Roman state and underminers of the Roman Republic that it has never forgotten to this very day….Fired by a desire for freedom, the Florentines adopted their penchant for fighting and their zeal for the republican side, and this attitude has persisted down to the present day.”

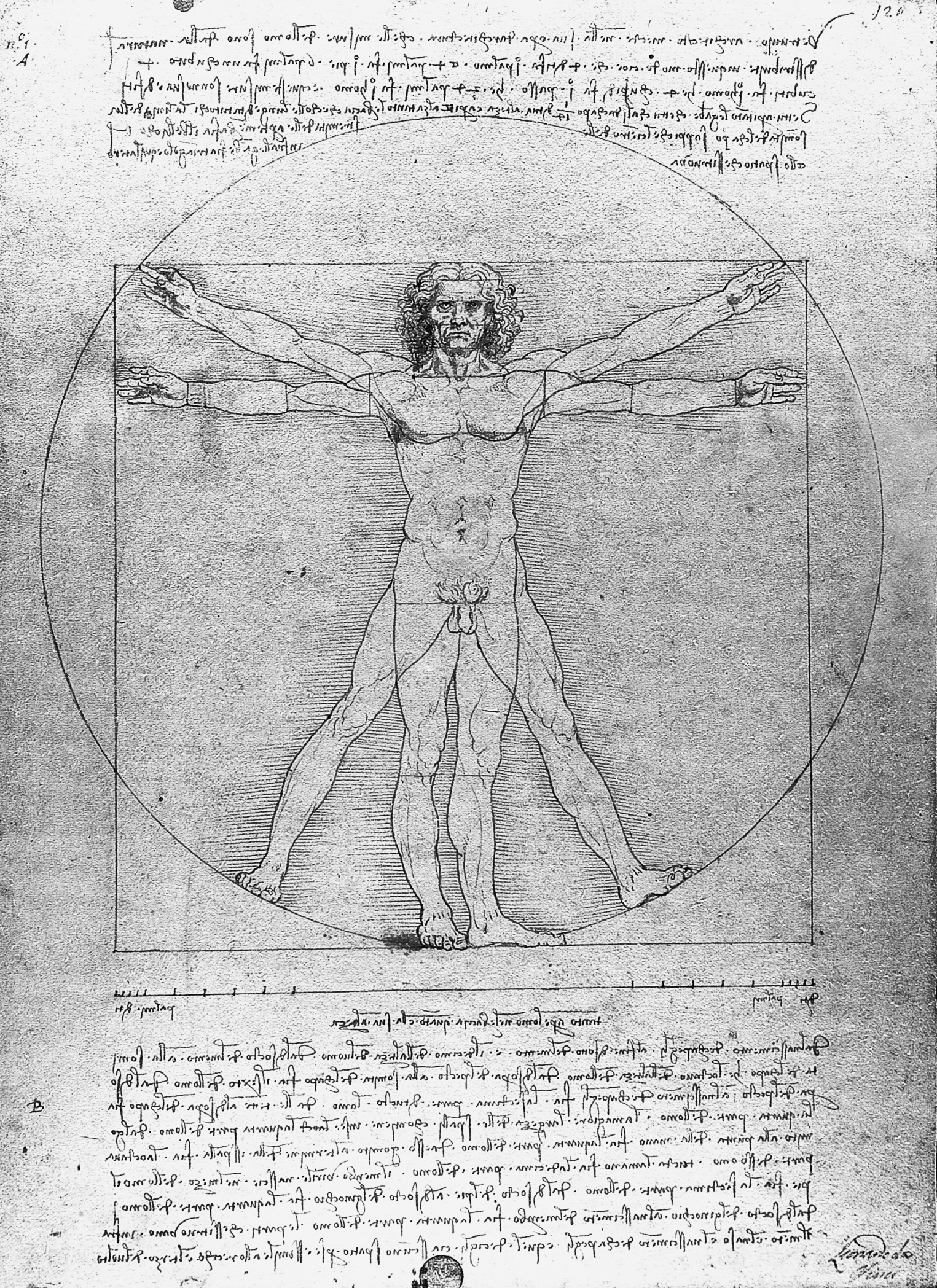

The notion that civic engagement was a moral imperative that allowed man to express his better self and, in doing so, also favorably sway to his advantage the course of destiny was shared by the humanist Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), who epitomized the concept of “Renaissance man”: the multitalented and broadly learned individual who also came to be embodied by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Alberti, who was fond of saying that “men can do all things if they will” and was known for his boundless energy, was a master of archery, an excellent rider, and an intellectual who could juggle with equal ability a conversation about literature, law, linguistics, mathematics, astronomy, music, and geometry. Additionally, he was a great architect—the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, the facade of Santa Maria Novella, and the Palazzo Rucellai are among his most famous achievements—and a skilled painter. In his treatise On the Art of Building, Alberti used the precepts of the newly rediscovered De architectura, written in the mid-20s B.C. by the Roman architect and author Vitruvius, to conclude that to produce a beautiful building, the architect was to reproduce the same geometrical and arithmetical proportions that God, the supreme Architect, had imposed on the body of man. This belief, which derived from the Greeks, who had first linked the harmony of the human body to the harmony of the cosmos, was re-proposed by Leonardo da Vinci in his Vitruvian Man (ca. 1490)—a perfectly proportionate male body with extended arms and legs, enclosed within a square (symbol of earthly reality) and a circle (symbol of God’s eternity) to indicate that man represented a scaled-down version of the divinely infused universe.

Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man (ca. 1490)—the human body in perfect harmony with the cosmos

Alberti, who also wrote the books On Painting and On Sculpture, was among the first writers to elevate to a higher status the role of the artist, who in the past had simply been defined as a craftsman, meaning a manual worker dealing with the manipulation of matter—an activity felt to be vastly inferior to the disciplines that had to do with the world of ideas. Challenging that prejudice, Alberti affirmed that the ingenuity displayed in the work of painters and architects made their crafts deserving of being placed among the liberal arts. For Alberti, as for Leonardo in later years, an artist was not simply an “artisan, but rather an intellectual prepared in all disciplines and all fields.”

In the treatise On the Family (1443), Alberti stressed the important role that family and education had in the creation of a well-rounded personality. Unfortunately, the harmonic equilibrium between different social forces that Alberti so passionately advocated did not include women. By enforcing the old belief in the absolute authority of the father figure, Alberti, like most men of his age, kept women relegated to the same secondary role they were assigned to since antiquity.

Despite that stubborn prejudice, many women of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were able to distinguish themselves by becoming scholars, writers, and poets in their own right. The majority of these women, like Isotta Nogarola, Veronica Gàmbara, Gaspara Stampa, and Vittoria Colonna, came from wealthy families, but others, like the Venetian Veronica Franco, were courtesans whose cultural sophistication earned them the respectful title of cortigiana onesta to distinguish them from lower-class prostitutes.

The celebration of man as a uniquely endowed creature was also articulated by the humanist Giannozzo Manetti (1396–1459), who wrote a book titled On the Dignity and Excellence of Man in Four Books. The work was written in response to the pessimistic ideas that Pope Innocent III had expressed, almost two hundred years earlier, in his On the Misery of Man. The scholar Charles G. Nauert writes that whereas the pope in order to exalt the soul had focused “on the putrefying decay and the excrement of the body as symbols of true human nature, Manetti lauded the harmony and beauty of the human body, reflecting man’s creation by God in his own image.”

The humanists had good reason to be optimistic, especially in a place like Florence whose cloth and textile industry had allowed it to become the richest city in Europe. One of Florence’s great advantages was a secret dye derived from a lichen, brought home from the East by the Florentine merchant Federico Oricellari, that added a beautiful violet pigment to the high-quality wool that was shipped to Italy from England, Scotland, and North Africa. Another factor that allowed Florence to become a superpower was its banking activity, which was conducted by major Florentine families, like the Bardi, the Peruzzi, the Strozzi, the Albizzi, and especially the Medici, who turned the fiorino into the strongest currency of Europe.

As prosperity grew, the guilds became increasingly engaged in the improvement of the city. The Arte della Lana (Wool Guild) and the Arte della Calimala (Cloth Guild) contributed funds for the building of the duomo, the Gothic-style church designed by Arnolfo di Cambio, which was built in 1296, as well as for the nearby baptistery, the bell tower designed by Giotto, and the oratory and grain market called Orsanmichele.

The great amount of money that the secular and business-dominated government of Florence assigned to artistic projects that in most cases were religiously inspired tells us that even if the reputation of the church as an institution had been devalued, religion, albeit often tinted with superstitious feelings, was still prominent just as the fear of God’s ultimate judgment. As we have seen, bankers who practiced usury in violation of the church’s ban often invested great sums of money in family chapels as a way to seek forgiveness for the “sin” they committed. The Florentine family of the Bardi and Peruzzi, for example, spent a huge amount of money for the decoration of the two chapels they owned in the Franciscan Church of Santa Croce, one dedicated to the life of Saint Francis and a second one to John the Baptist and John the Evangelist. Knowing that Saint Francis had repudiated the wealth of his merchant family for a life of poverty makes the choice quite odd—unless, of course, we conclude that the Bardi-Peruzzi did so as a means of penitential contrivance, which, they hoped, would have gained them God’s forgiveness for the transgressions committed in their professional activity. Additionally, Saint Francis might have been a convenient way to hide behind a mask of humility the enormous ambition that fueled their success—a necessary requirement in a city so sensitive to the danger of tyrannical aspirations. (The Bardi-Peruzzi eventually suffered a major blow from England: when King Edward III, who had received substantial loans from the Florentine family to finance his war against France, failed to repay those loans, he caused the disastrous demise of the Bardi-Peruzzi bank.)

FLORENCE: THE CITY OF SPLENDOR

Among the many wealthy members of Florentine society, a particular place of prominence was occupied by the Medici family, whose banking activity was initiated by Giovanni, a smart businessman who managed to become the official banker of the pope. The charitable benefactions on behalf of the city, like his contribution to the Ospedale degli Innocenti, an orphanage sponsored by the Silk Guild and designed by Filippo Brunelleschi (the building, with its classical references, is considered the first example of Renaissance architecture), were used by Giovanni to gain the benevolence of his fellow Florentines. When he died in 1429, Giovanni was succeeded by his son Cosimo (1389–1464), who, like his father, was not only a clever businessman but also an astute politician, keenly aware of the importance that cultivating a good reputation had for the family’s success. To present himself as fair and balanced, Cosimo always made sure to keep a low and unassuming profile. When the architect Brunelleschi, whom he had asked to design a project for the family residence, presented him with a plan for a palazzo that was extremely grand and lavish, Cosimo prudently refused, turning to the architect Michelozzo Michelozzi, who came up with a much less showy design.

Jealous of the high regard in which the head of the Medici family was held, a competitor, Rinaldo degli Albizzi, spread the rumor that Cosimo intended to take over the Florentine Republic. As a result, Cosimo was pushed into exile. But only for a very brief time: when Rinaldo degli Albizzi tried to assign to himself a position of political preeminence within the city, Cosimo was promptly called back and elected chief magistrate, or gonfaloniere, which was the highest executive office of the republic. Confirming his cautious approach to politics, Cosimo in the years that followed was able to gradually amass greater and greater power, but always with moves carefully conducted behind the scenes, such as briberies and political maneuverings that left intact the illusion that Florence was still a republic when in reality it was slowly morphing into a signoria. Cosimo’s capacity to mute his critics and sway in his favor the political winds without ever acknowledging, in an official fashion, the fact that the city was gradually becoming his own private princedom shows a deep affinity with the emperor Augustus, who did not hesitate to corrupt the electoral system to rise to power while astutely presenting himself as savior, rather than usurper, of the republic. The impression is confirmed by the title assigned to Cosimo, who, just like Augustus, was called pater patriae (father of the nation) by his fellow Florentines.

Among the many qualities that made Cosimo popular was his diplomatic ability. For example, to keep Florence safe from Milan’s expansionist ambition, Cosimo funneled a great amount of money to Francesco Sforza, the Milanese condottiere (military leader) who was eventually able to snatch control of Milan away from the Visconti. The alliance that Cosimo forged with the new ruler of Milan gave Florence leverage against Venice, the ambitious Queen of the Sea whose aggressive politics were a constant threat to the rest of Italy.

Cosimo’s approval was also kept high by his generous contributions to the city of Florence, whose fame and prestige he enhanced through the work of the many artists he sponsored, like Ghiberti, Paolo Uccello, Luca Della Robbia, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Filippo Lippi, Brunelleschi, and Donatello. Because, like other super-wealthy people, he feared the judgment of God, he never neglected to invest a lot of money in pious enterprises, like the reconstruction of the monastery of San Marco that became famous for the magnificent mystical frescoes executed by Fra Angelico. Influenced by humanist scholars, like the rich Niccolò Niccoli, Cosimo also established in San Marco the first public library. Thanks to the great resources that Cosimo deployed for the search and purchase of manuscripts, the library of Florence became the largest collection of books in all of Europe. That precious repository of culture was later moved to a building originally designed by Michelangelo in 1523, the Biblioteca Laurenziana. The cult of books that the humanistic movement fostered was greatly facilitated in the middle of the fifteenth century by the invention of the printing press by the German Johannes Gutenberg, which rapidly transformed the privilege of culture that once belonged to a few into a tool widely available to many.

While many European cities thrived, Byzantium continued to experience a slow decline, despite the efforts of the emperor Michael VII Palaiologos, who tried to restore the city’s old prestige after the dramatic events that had occurred in the Fourth Crusade. But Byzantium’s frail condition, which was worsened by the constant threat of the Muslims, remained problematic. To find a solution, new diplomatic contacts were developed to attempt a reconciliation between the Latin and the Greek churches. Among the people who came to Italy to explore the possibility of some sort of entente between West and East was George Gemistus Plethon, a highly regarded Byzantine intellectual whom Cosimo befriended and invited to Florence for a series of lectures on Plato. At that time, Plato was still largely unknown in the West because, as indicated before, apart from indirect references from authors such as Cicero and Augustine, the only book that the Middle Ages possessed of the Athenian philosopher was the Timaeus, which had been translated into Latin by Calcidius in the fourth century A.D. The lectures on Plato that Gemistus Plethon gave in Florence set humanists, scholars, and intellectuals aflame with enthusiasm. Caught by the wave of interest that Plato’s mystical philosophy prompted, Cosimo decided to invest money in the creation of a Platonic Academy, which was founded in 1445. At the helm of the Academy, Cosimo placed the philosopher Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), who went on to translate from Greek to Latin all of Plato’s and Plotinus’s work and also the writing of Hermes Trismegistus, a mythical figure who was erroneously believed to be an Egyptian wise man who had lived shortly after Moses (scholars now believe that the Hermetic writings belong to an unknown group of Greek authors who lived between A.D. 100 and 300). The work of Ficino and that of the humanists who attended the Platonic Academy were essential for making Plato central to the interests of most Renaissance scholars, thus bringing to an end the Scholastic passion for Aristotle that had dominated the Western mind for almost four hundred years.

Ficino’s most important work was the Theologia Platonica. The work that Will Durant defines as a “confusing medley of orthodoxy, occultism, and Hellenism” exalted Plato as an enlightened philosopher whose prophetic ideas anticipated truths eventually validated by Christianity. The pivotal concept of Ficino’s Neoplatonic philosophy was that by being a point of encounter between matter and spirit, man was an exceptional creature capable of recognizing in love and beauty the conduits necessary to reach higher forms of feeling and understanding. By exalting the Golden Age of Florence, Ficino wanted to exalt the makers of art who, as the critic Arthur Herman explains, had been moved by the desire to achieve virtue through creativity using the beauty of their work to draw themselves and their viewers closer to the divine creator of the universe—God.

Since the thirteenth century, Florence had indeed become the stage of an enormous amount of astounding artistic achievements. The thread that linked all those innovations was based on a revived interest in everything that the classical world could offer. But studying the models of the past had not been easy, given that Rome, the main showcase of antiquity, lay shattered in ruins, with most of its ancient treasures neglected and half buried in dirt. Brunelleschi and Donatello, who for ten years repeatedly returned to Rome to draw sketches of statues and reliefs and to measure the proportions of old buildings, would have been quite aware of those difficulties. The names Monte Caprino (Goat Hill) and Campo Vaccino (Field of Cows), which were given to the Capitoline Hill and the Forum because of the cows, goats, sheep, and pigs that were brought there to graze, give us a sense of the dilapidated condition into which the Roman antiquities had fallen.

Despite that widespread squalor, Rome had remained a popular destination for many Christian pilgrims who came to visit the city carrying with them a guide called Mirabilia urbis Romae (The marvels of Rome). But the wondrous remains that attracted those travelers were religious rather than secular, like the holy finger of Saint Thomas in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme; the arm of Saint Anne, mother of Mary; or the head of the Samaritan woman converted by Christ, which was kept in the Church of San Paolo Fuori le Mura. The fact that Brunelleschi and Donatello were not part of those pious crowds must have greatly puzzled the people of Rome: What were those two men doing wandering among the Roman ruins, and what were they looking for with their endless diggings? Maybe, people thought, they were treasure hunters in search of golden coins or some other precious object from the past. Superstition told them that men like that had to be avoided at all cost: disturbing the pagan spirits was a dangerous venture, and no one wanted to be part of it. Little did they know it was that very activity that would inspire the masterpieces that initiated the great artistic revolution known as the Renaissance.

In Brunelleschi’s case, the trip to Rome had come after his defeat by the artist Lorenzo Ghiberti, who won the competition that the city of Florence had organized to select the artist assigned to produce the bronze doors that were to decorate the baptistery. Losing to Ghiberti—who went on to produce those magnificent doors, which Michelangelo honored by naming them the Gates of Paradise—had been a painful disappointment for Brunelleschi, but vindication came when he was later chosen for the design of the cupola that was to be placed on top of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Brunelleschi, who brought that amazing task to completion in 1434, used as inspiration the Roman Pantheon. The cupola he designed was conceived as a double shell supported by a strong internal framework made of brick and stone that rested on an octagonal drum. The beauty of the massive dome rising effortlessly above Santa Maria del Fiore came to be praised as one of the major wonders of the world fated to inspire, for centuries to come, legions of future architects. In later years, while planning the cupola of Saint Peter in Rome, Michelangelo paid tribute to Brunelleschi’s masterpiece by saying, “I will do a bigger one but not more beautiful than that of the Duomo.”

Brunelleschi also became famous for his studies on linear perspective. As we have seen, because they favored God’s infinity over man’s relativity, medieval artists had consciously neglected the realism of three-dimensionality in favor of abstract and alogical visions of the divine, seen as complete otherness from the world of matter. In a radical reversal of that optical and mental perspective, Brunelleschi developed the mathematical and geometrical rules necessary to master the vanishing point that Renaissance painters used to prioritize the human subject’s point of view, thus making man, once again, the measure of all things.

Brunelleschi’s cupola of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, 1434—the duomo

With Donatello, the influence of classical times was translated into a vigorous realism that forever revolutionized the art of sculpture. We see this, for example, in the biblical figure of Habakkuk, which the Florentines named the Zuccone (dialect for “big head”), destined for one of the niches placed on top of Giotto’s bell tower. In contrast to the idealized serenity that Gothic artists had invariably attributed to biblical figures, Donatello’s Habakkuk is given a completely true-to-life likeness: an unflattering and odd-shaped bold head, a harsh face, and a strong body covered with a shapeless cloak that, less than a prophet, makes him look like a Roman senator unafraid of throwing himself into the messy affairs of the world (see this page). In his pursuit of realism, Donatello, who mastered all sorts of materials (stucco, marble, bronze, wood), was able to convey in an unprecedented way the drama of human life. Among his other powerful images are the bronze statue of John the Baptist that he produced for the Cathedral of Siena and the shockingly emaciated wooden-carved image of the penitent Mary Magdalene, who, as a medieval legend believed, had searched for salvation in the wilderness and in loneliness (see this page).

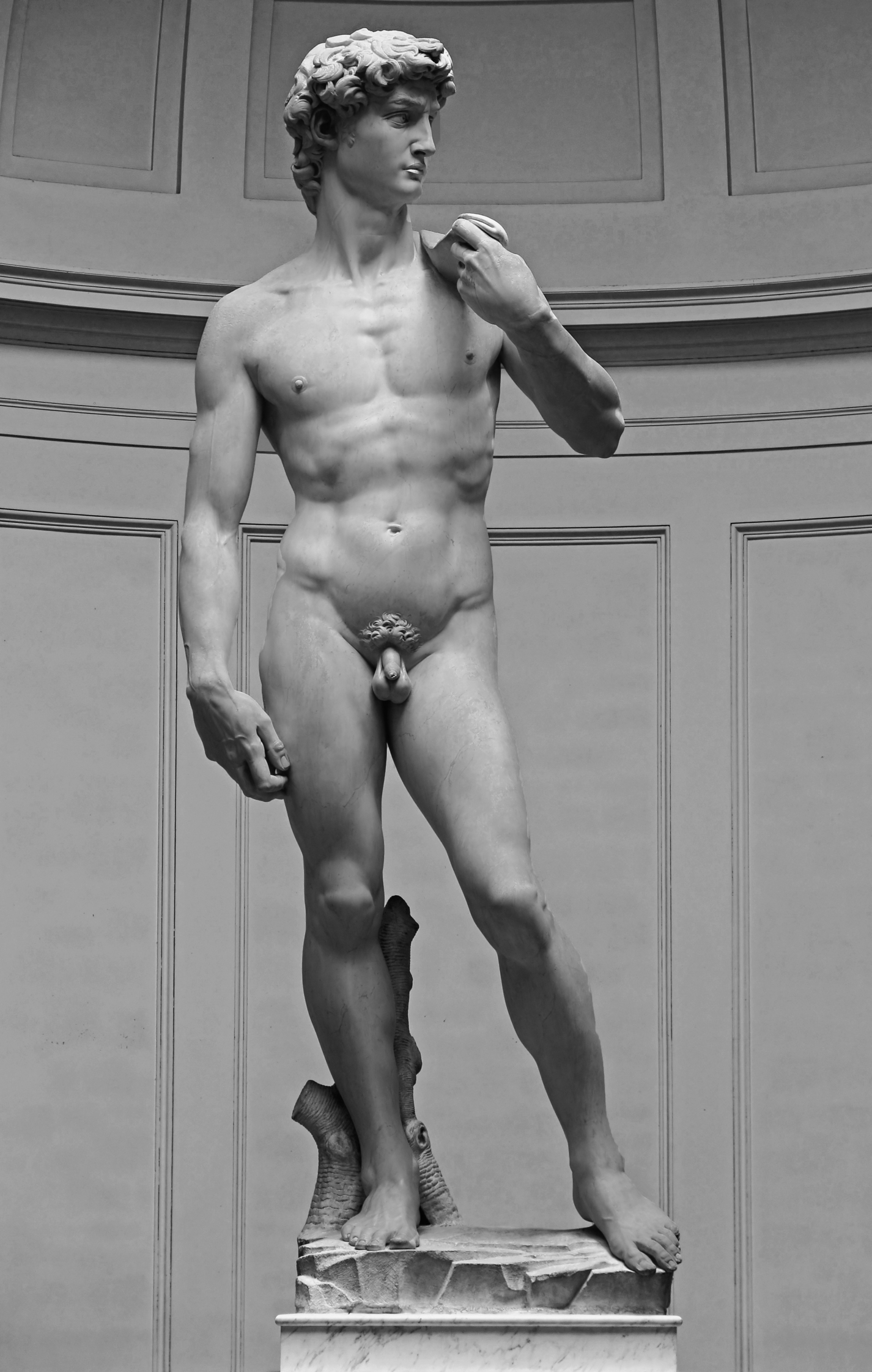

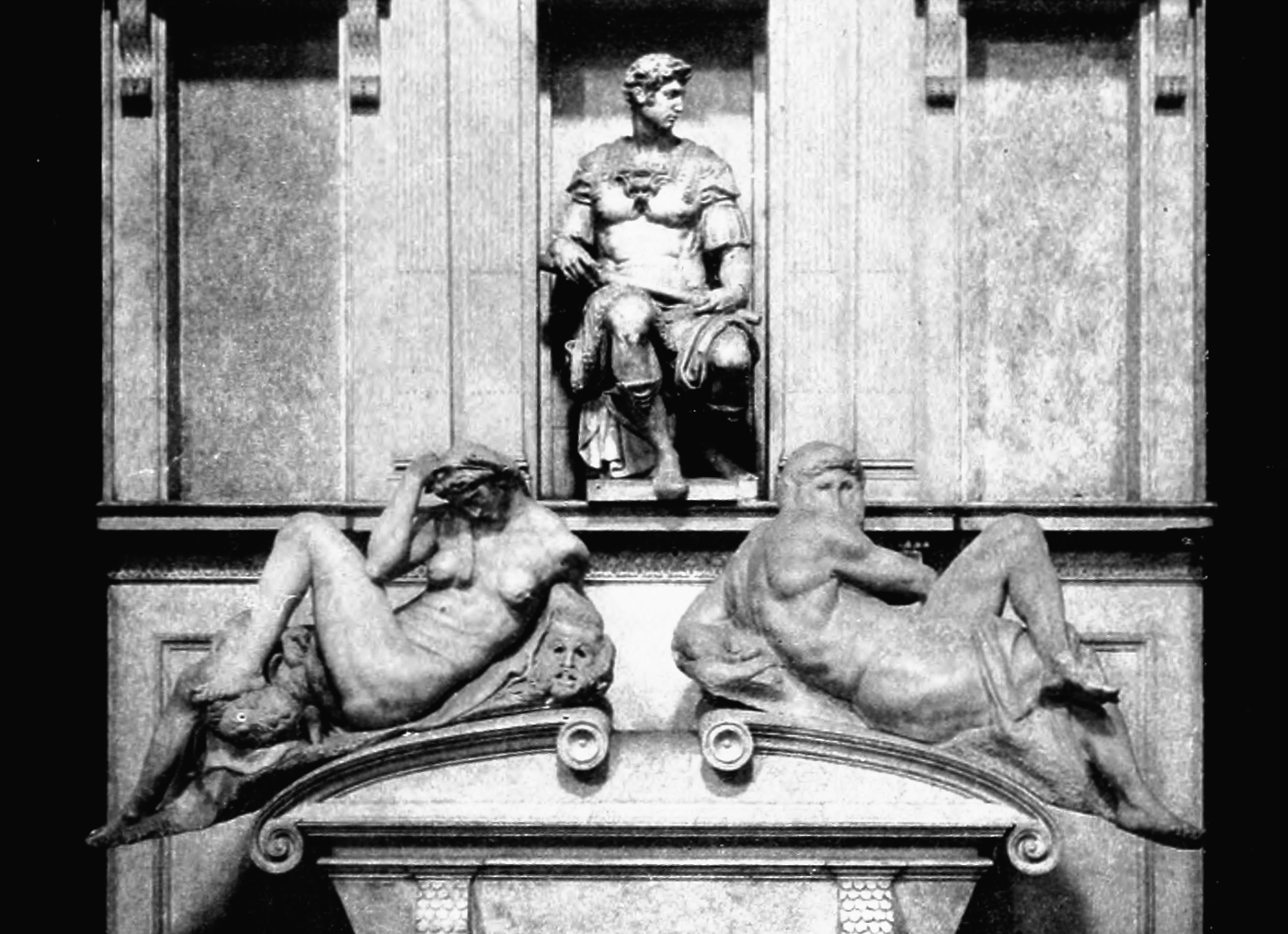

It seems fitting that it was such an extraordinary man who finally emancipated sculpture from the subordinate position it had been relegated to for more than a thousand years as a mere appendix of religious architecture. Besides the bronze equestrian statue of the military leader Gattamelata, the first statue that Donatello conceived outside the context of a church was the David—the first freestanding statue on the round to reappear in the West since the fall of the Roman Empire (see this page).

The bronze statue, which was probably commissioned by the Medici for the courtyard of their palace, portrays the young shepherd David as a naked adolescent proudly placing his foot on the head of the giant Goliath, the massive warrior who, as the Bible narrates, had spread fear among the Israelites during their war against the Philistines and was eventually killed by the rock flung from David’s sling. The intense eroticism that the statue exudes is accentuated by the long feather attached to Goliath’s helmet, which seems to caress the inner part of the boy’s right leg while reaching up to his groin. Nothing ethereal and spiritual can be found in this image: drastically severing the ties with tradition, Donatello not only gives the statue autonomy from the religious context but also makes the sensual and purely organic reality of the body a subject worthy of the admiration and celebration of art.

Donatello’s biblical Habakkuk, or Zuccone (Big Head)

Donatello’s emaciated Mary Magdalene

Donatello’s bronze David, the first freestanding statue in the West since the Roman Empire collapsed

As the works mentioned show, the spirit that moved Brunelleschi and Donatello was not to reproduce old models but to use them as inspiration for the creation of something completely new and unique. This principle had been advocated by Petrarch, who said that culture consisted not of arid erudition but of an active process of assimilation in view of a new, original synthesis. To explain that principle, Petrarch used as metaphor the work of bees that pick pollen from different flowers to then create their own unique honey.

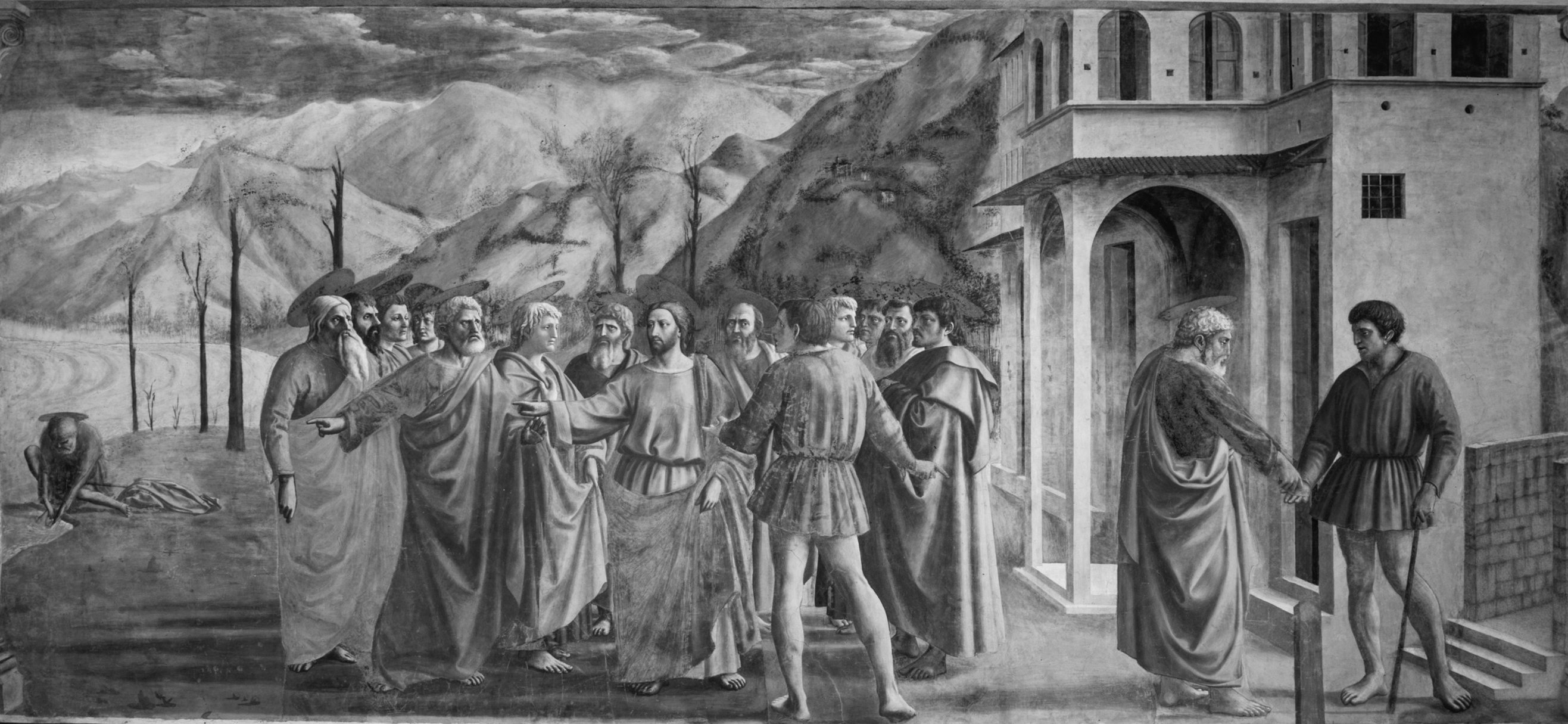

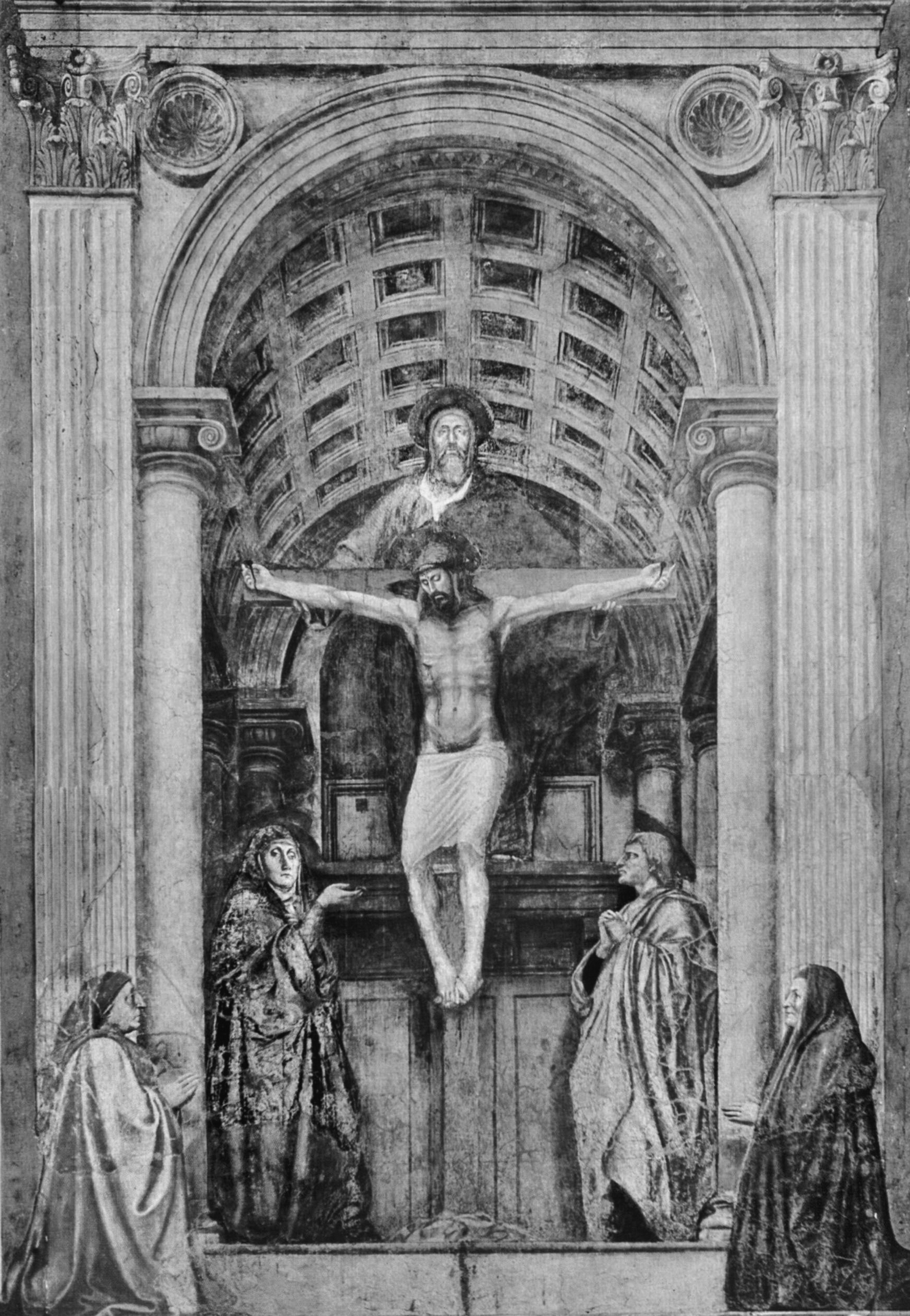

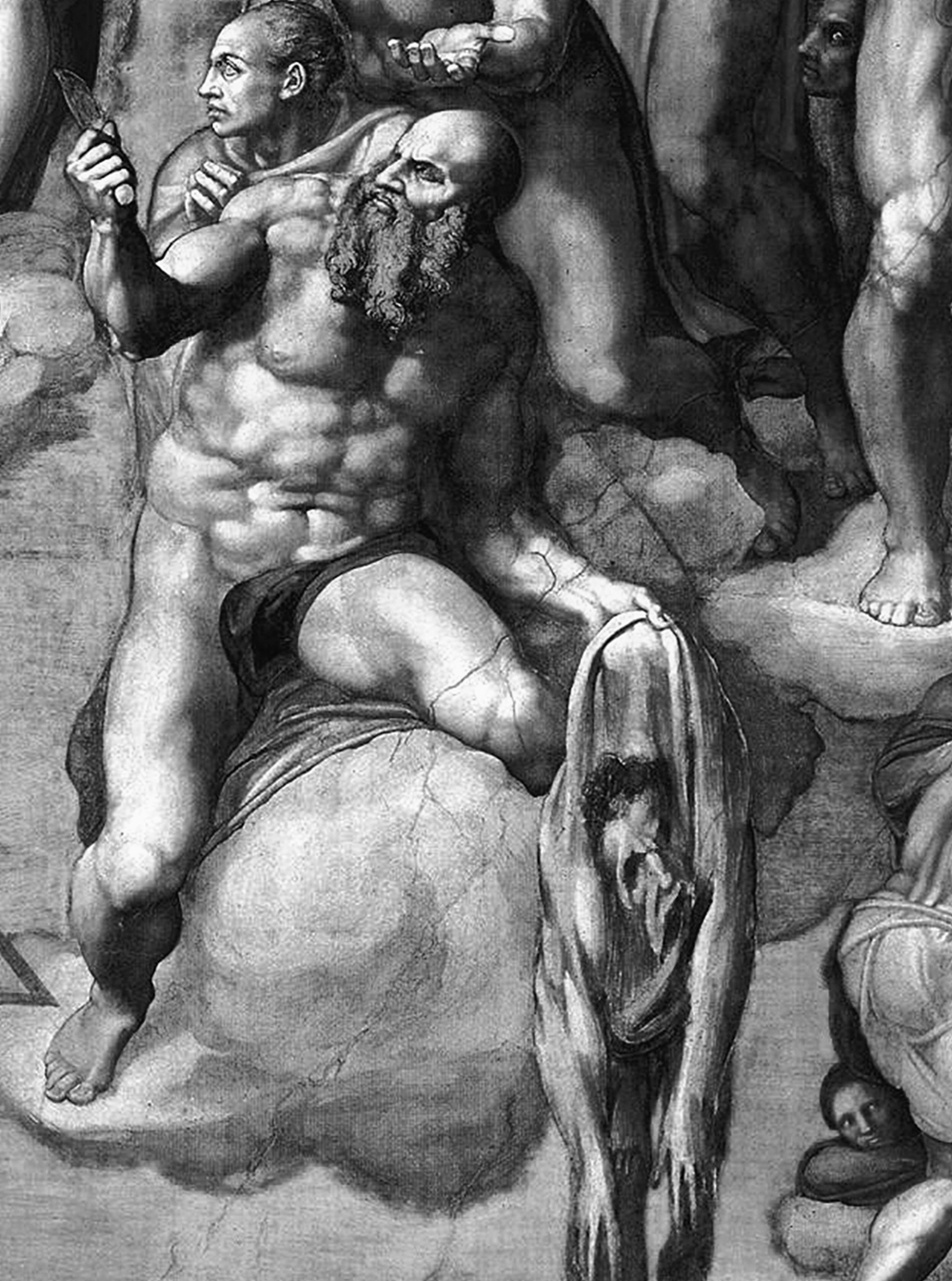

As Brunelleschi did in architecture and Donatello in sculpture, the first painter who, after Giotto, articulated, in his own original way, the classical lesson was Masaccio (1401–1428). Masaccio, who died when he was only twenty-six years old, is essentially remembered for two main works: the Holy Trinity in the Church of Santa Maria Novella, which profoundly impressed his contemporaries for his skillful use of perspective (we will return to it later), and the frescoes he did for the Brancacci Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, in Florence. A sense of Masaccio’s style can be ascertained from the famous scene called The Tribute Money.

The scene visualizes the story told in the Gospel of Matthew: a tax collector stops Christ and His disciples to demand money for the state. The range of meticulously choreographed gestures, movements, and expressions performed by the solidly built figures (so evocative of Roman senators) conveys the variety of thoughts and emotions described in the story: assertiveness, surprise, hesitation, and indignation, all rotating around the calm presence of Christ, Who tells Peter to go to the lake to catch a fish and find a coin in its mouth. (Peter executing Christ’s command is seen in the rear of the picture.) The spatial depth, which demonstrates Masaccio’s familiarity with the rules of perspective, adds realism to the representation, as does the depiction of the natural light (which, as we have seen, had been abandoned for more than a thousand years) that the painter underlines through the long shadows that appear on the ground to indicate the afternoon hours of a cold winter day.

Masaccio’s The Tribute Money, the Brancacci Chapel, Florence Credit 11

The masterly technique used by Masaccio to enhance Christ’s humanity and immerse His presence in a completely realistic context was met with a chorus of praise by his contemporaries. Those compliments must have greatly pleased the silk merchant Felice Brancacci, who, like many other wealthy citizens, sponsored that work not only for devotional purposes but also to enhance his worldly status by showing that money and success had in no way diminished his sense of responsibility and commitment to civic duty. The money theme that Felice Brancacci chose for the painting is in itself an evident wink to his fellow citizens, who, pressed by the high expenses that the war with Milan required, had been discussing a possible increase in taxes, which Brancacci, who wanted to show off his civic virtue, was positively advocating.

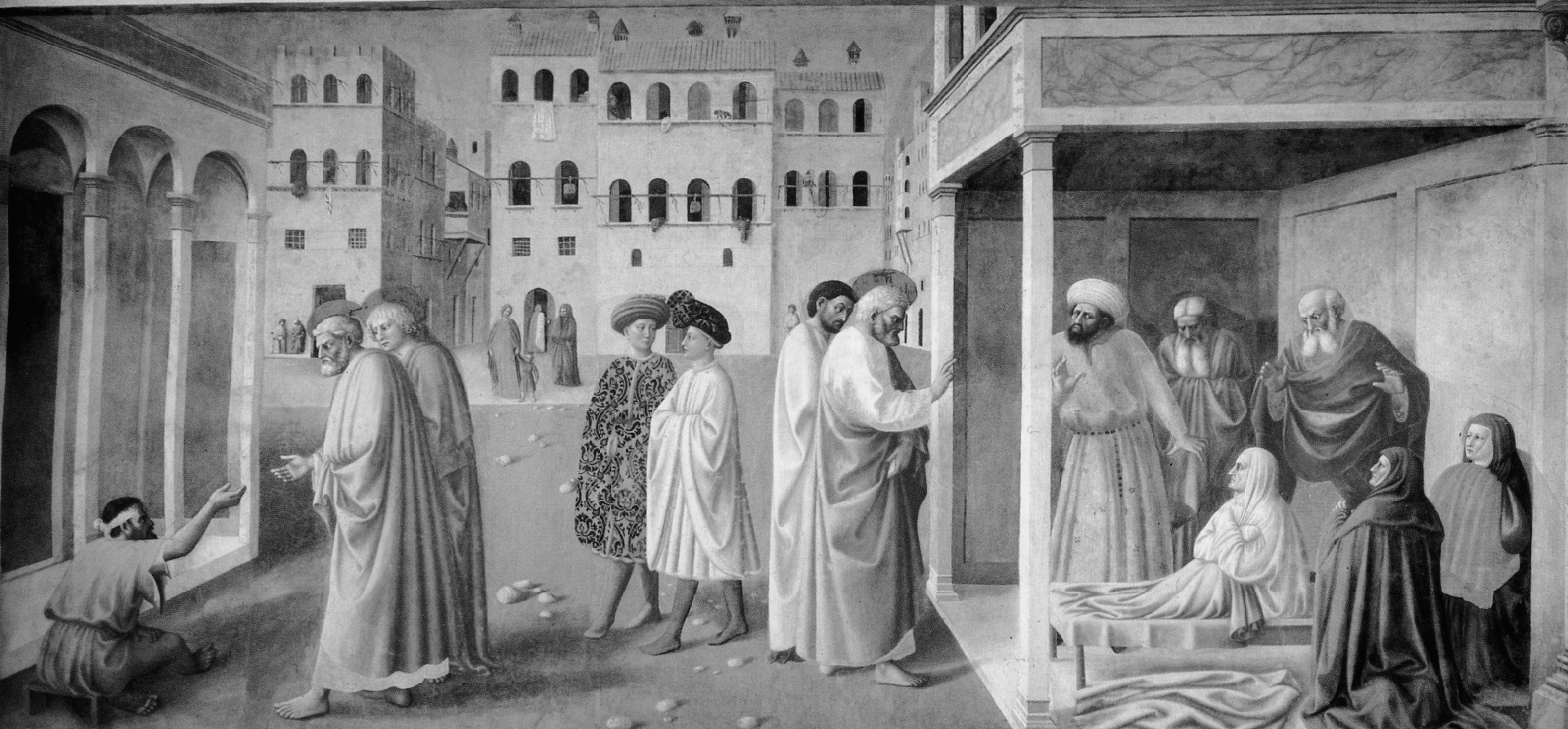

Masaccio’s use of a religious theme to disguise secular intentions is also present in the work of his teacher Masolino (1383–ca. 1440), whose painting appears in the same chapel. The well-known scene, shown on this page, puts together two events separately narrated in the New Testament: Saint Peter miraculously raising the dead Tabitha and Saint Peter healing a crippled man.

The background that connects the two scenes depicts a sunny open space lined by an elegant group of pastel-colored houses, typical of the fifteenth-century Florence in which Masaccio and Masolino lived and operated. Placing biblical scenes in familiar contemporary surroundings was a fashion developed in Bruges, Ghent, and Brussels by fifteenth-century artists such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Robert Campin. In a similar manner, Masolino seems to take pleasure in lingering on details of everyday life: from the blankets hanging out of windows to be dusted off, to flowerpots, birdcages, and even an exotic pet monkey brought from some faraway land that we see on the ledge of one of the buildings. The calm routine of the beautiful morning is further animated by the presence of people going about their business in the streets of the city. Particularly relevant is the image of two men, clad with fancy Renaissance hats and garments, placed in the middle of the scene who appear so absorbed in their conversation as to remain completely unaware of Saint Peter’s miraculous actions that are occurring right next to them. The feeling that the viewer gets is of two completely independent and unrelated planes of reality: a secular plane and a religious one running on parallel tracks, with no evident connection to each other. How are we supposed to interpret that enigmatic choice? A comparison between the fancy richness of the city and the particularity of the two miracles is the key to the enigma: the crippled man and the dead woman restored to a healthy life were probably intended as a clever, indirect praise of the city of Florence, which, resurrected by the mercantile activity, had gained an unprecedented level of splendor and prosperity.

Masolino’s rendering of Saint Peter’s dual miracles, also in the Brancacci Chapel, with detail, above

Using religious themes to praise secular achievements reached a whole new level of audacity in the work of the famous painter Gentile da Fabriano (ca. 1370–1427), who was hired by the banker Palla Strozzi, the great rival of the Medici family, to produce an altarpiece titled The Adoration of the Magi, to be placed in the family chapel located in the sacristy of Santa Trinità in Florence.

Gentile da Fabriano’s altarpiece The Adoration of the Magi, in the sacristy of Santa Trinità, in Florence

What appears unique in this painting is where and how the sponsors of the artwork are depicted within the scene. In the mature phase of the Middle Ages, placing sponsors within a religious composition had become a common practice. But when it happened, two strict rules were maintained: the sponsor, who was always given a secondary position vis-à-vis the religious figures, had to show a humble and respectful deference toward the holy event. What makes this painting so strikingly different is the almost defiant way with which Gentile da Fabriano gives the members of the Strozzi family a size comparable to that of the Magi, while assigning them a place of enormous importance right next to the three kings. Behind them is the great procession of elegantly dressed people who represent the Strozzi’s fancy entourage.

But there is more: according to Christian tradition, Mother and Child were to be assigned a prominence that no other figure or event could overshadow. By placing the scene of the Nativity as the final destination of the long procession, Gentile da Fabriano at first seems to respect that rule. But what we realize, as soon as we linger a little longer on the image, is that the lively crowd, the colorful costumes, the exotic monkey, the hunting falcons, the restless horses, and the purebred dogs keep pulling our eyes away from the contemplation of that sacred moment. Our distraction appears shared by the characters portrayed in the painting: except for Palla Strozzi (recognizable by the falcon he holds on his left arm), none of the people who accompany him appear to pay attention to the Nativity scene. Even the big star glowing on top of the manger fails to attract their curiosity: caught by the excitement of the hunting day from which they have just returned, people look at each other as if sharing stories or simply marveling at two birds fighting right above their heads. Their eyes wander everywhere, except in the direction of baby Jesus. Such irreverence, in less permissive times, would have been condemned as an appalling sacrilege, only good to feed the flames of hell.

In spite of the morally ennobling claims of people like Alberti and Ficino who insisted that virtue was behind man’s celebration of beauty, what seemed to consume the rich Florentines were mainly temporal and political concerns. To prove the point, one need only look at the frescoes that Benozzo Gozzoli did for the Medici between 1459 and 1461 in the chapel situated in the family palace.