![]()

IT IS OFTEN SUGGESTED that most naval officers of the pre-1914 generation were obsessed with the new technology and hence neglected to think about how it would be used. Much the same was later said of US nuclear submarine officers. It certainly took considerable effort to master the technical aspects of new ships and weapons. However, there was lively interest in the tactical implications of the new technology. If anything, there seems to have been too much appreciation of where the technology might lead and too little of its current limitations. In Britain Admiral Fisher seems to have been the leading example of the problem. He could see the tactical implications of such new technologies as torpedoes and long-range wireless, but he grossly down-played current limitations. He seems to have had little or no interest in promoting exercises which might have highlighted steps needed to achieve what he expected the new technology to deliver. That is particularly obvious in hindsight in his approach to naval strategy using ocean surveillance via radio intelligence.

Lessons of the Russo-Japanese War

The most recent naval war, the Russo-Japanese War, was largely a fleet-on-fleet fight. Neither side had so many battleships that it could afford many losses and neither had any hope of adding them in wartime (the Russians tried but failed to buy several ships). Merchant shipping and blockade hardly figured in the war, but naval supremacy certainly did. At the outset, the Japanese considered the large Russian Pacific Fleet based in Port Arthur the single great obstacle to moving an invasion force across the Sea of Japan to Manchuria, the prize they sought. The Russians also had Baltic and Black Sea Fleets, which they could deploy (albeit laboriously) to reinforce the Port Arthur force. They could move troops, again somewhat laboriously, from European Russia to the Far East via the Trans-Siberian Railway.

In February 1904 Japanese destroyers successfully penetrated Port Arthur in an attempt to solve the problem at the outset. This attack was not very successful; torpedoes did not match their advertising. The idea of a surprise attack made a considerable impression on other navies and the Port Arthur attack may have inspired the attack on Pearl Harbor a quarter-century later. An initial fleet-on-fleet battle was also indecisive. Afterwards a Japanese mine sank the Russian Pacific Fleet flagship, killing its charismatic leader Admiral Makarov. His successor was a lot less aggressive, perhaps fearing that the Japanese had closed the mouth of Port Arthur with mines. The Japanese thus gained sufficient sea control to land their army. It seized enough ground to emplace heavy mortars on the heights above Port Arthur. They sank most of the ships inside the base during a lengthy siege. The Russians sought to lift the siege by bringing their more powerful Baltic Fleet halfway around the world into the Sea of Japan. By the time it arrived, Port Arthur had fallen. The Japanese destroyed the Baltic Fleet at the battle of Tsushima, which helped shape expectations for fleet battle in the next war.

The role of heavy guns was changing dramatically as the war was fought. Until very recently they had fired very slowly, the faster medium-calibre guns being considered decisive (the heavy guns were reserved to deal with the heaviest armour). Advances in turret design also made the heaviest guns far more usable. Experience at Tsushima in effect ratified a growing opinion that the heaviest guns were the weapons of the future. An increasing rate of fire was crucial, because it was assumed that the effect of shellfire would be cumulative. To disable or sink an opponent, a ship had to pour in a considerable volume of fire. That might mean fire by a numerous battery of large-calibre guns on a sustained basis. This perception was an important basis for the dreadnought revolution in capital ship design.

By way of contrast, it was understood that an underwater weapon – a torpedo or mine – could disable or sink a ship with a single hit. However, the chance of a hit by a slow-moving torpedo was considerably less than that with a fast-firing gun. In 1904 torpedo range was beginning to increase dramatically with the introduction of heaters, a simple form of internal combustion. At least in the Royal Navy, an important reason for extending heavy gun range was to keep British battleships out of torpedo range of enemy battleships. At least in theory, the art of successful naval battle was to combine guns and underwater weapons using new tactics.

Although torpedoes were relatively ineffective during the war, mines were quite the opposite. Their success led both the Royal Navy and the US Navy to convert cruisers to specialised minelayers (the Germans already had them). The Japanese revealed to the British that at Tsushima one of their destroyers sank a Russian battleship by laying a pair of connected floating mines in her path. By 1909 the floating-mine attack was a standard Japanese tactic. Destroyers passing 1000 to 2000m ahead of the enemy, on the same course, would drop mines, then steam away at maximum speed. Although analysis showed that such mines were not particularly effective, the idea made a considerable impact on Director of Naval Ordnance John Jellicoe. It almost certainly explains Jellicoe’s repeated wartime statements that the Germans planned to lay mines in the path of his fleet. Many German destroyers were fitted for minelaying, but of a more conventional sort. The floating-mine report appeared at about the same time the Royal Navy became interested in re-integrating destroyers into its battle fleet. On 24 April 1913 First Sea Lord ordered that all destroyers of ‘River’ and later classes should carry four mines each on the upper deck (each with 120lbs of TNT), the mines normally to be drifting but suitable for mooring. Little came of this idea, because the mines were never developed. However, ‘L’ class destroyers carried mine rails until 1915.

For naval thinkers in 1914, the great question was how to use guns and torpedoes in action. It was assumed that even a single underwater hit could be fatal – as when a single German mine sank the new dreadnought HMS Audacious in the Irish Sea on 27 October 1914. In fact it turned out that such ships could often survive multiple underwater hits. (Abrahams via Dr David Stevens, SPC-A)

The Japanese experience at Tsushima did not address other important questions. The most difficult was how to find the enemy at the outset. In the past, it was assumed that at the outset one fleet would blockade the other in its port. When the enemy tried to get to sea, the blockading fleet would attack and destroy it. During the late nineteenth century, that became less and less attractive because a blockading fleet made a good torpedo target. Initially that meant that the attacking fleet could not penetrate the enemy’s harbour, because it might be infested with small torpedo craft. Soon the torpedo boats grew to the point where they could operate well offshore and the area within sight of the enemy port became too hot to occupy. It might still be possible to station fast cruisers within sight of the enemy port. By 1904 early forms of radio had made it possible for such ships to provide an offshore fleet with sufficient warning. However, the trend was not good and the advent of seagoing submarines would make traditional forms of blockade altogether impossible.

At Tsushima the situation was simplified. The Russian fleet had to pass through a narrow strait (which gave its name to the battle). Japanese cruisers in the strait gave Admiral Togo sufficient indication of the approach path of the Russians for him to deploy appropriately. Once guns began to fire and coal-burning ships were steaming at high speed, no Admiral on his bridge could easily see (or communicate with) most of his fleet. Increasing gun range expanded the battle space, making it even more difficult for the Admiral even to visualise what was happening. No one said as much in 1904, but increasing numbers of ships also made it nearly impossible for an Admiral to maintain a mental picture of what was happening around him.

At Tsushima, Togo split his fleet into two squadrons because he doubted that a single officer could control more than eight ships. Later the choice was between such ‘divisional tactics’ and the tactics of a single concentrated fleet. Tsushima demonstrated both the potential of divisional tactics and their dangers. In theory one squadron was to support the other, but in fact the force split up. Togo was fortunate that one squadron did not fire on the other (it may have helped that the two fleets were very differently painted). The split offered the Russians valuable opportunities, which fortunately for Togo they wasted. In more modern terms, the issue was how to maintain both control and situational awareness on the part of the fleet commander.

Seapower and Seaborne Trade

In the popular mind, seapower in 1914 meant capital ships, or perhaps large cruisers standing in for them. Naval supremacy would be decided by a fight between the two opposing fleets. In fact the maritime prize was free use of the sea coupled with the ability to deny free use to the enemy. The capital ship fight was expected to determine who could use lesser warships to block enemy trade and to protect friendly trade. For example, it took large numbers of ships to stop numerous merchant ships. They could not possibly survive in the face of enemy capital ships. As a covering force, the Grand Fleet had to be able to fight and win a battle against the concentrated German High Seas Fleet, because if the High Seas Fleet broke out it could wipe out British shipping and also the British ships enforcing the blockade against Germany. Naval warfare was always about who could and who could not freely use the sea.

Despite much post-war talk to the contrary, the demands of trade protection shaped British naval policy – and even foreign policy – for decades prior to the war. The great charge against the Admiralty is that by the First World War it had lightly abandoned the successful trade protection policy of the past, convoy. Convoy Acts forced merchant ship owners to submit to Royal Navy orders and to join convoys with escorts. It was argued after the war that convoy had been abandoned because as a defensive strategy it was inferior to a more offensive form of protection, hunting down U-boats. The reality was considerably more complex.

Prior to the unrestricted U-boat campaign, the threat was cruisers, which combined high performance with endurance and firepower. With the advent of large fast liners, there was considerable pre-war speculation that they might represent a new kind of threat, but in practice armed liners were ineffective.1 In 1915 the Germans commissioned a new kind of auxiliary cruiser, a merchant ship operating in disguise (it was called an auxiliary cruiser [‘Hilfskreuzer’]). Similar ships were used during the next war. In neither case did they contribute seriously to commerce destruction.

Convoy died by the 1870s because with the advent of steam the Royal Navy had fewer and fewer ships which could match modern merchant ship performance (endurance at speed).2 Late nineteenth-century British war plans envisaged attacking French convoys and Russian outposts, at which commerce-raiding cruisers would be based. Troopships sent out for this purpose would be convoyed, but there was no hope of providing enough fast long-range cruisers to convoy most merchant ships. The only option was somehow to hunt raiding cruisers down. In December 1874 First Naval Lord Admiral Milne wrote an analysis of trade protection which shaped future policy. He argued that a commerce raider would be drawn into the areas where the great sea routes were concentrated – what were later called focal areas. Raiders would find themselves drawn into the focal areas, where they would meet British cruisers which would destroy them. Milne identified eighteen such areas. Even a focal area defence required numerous cruisers, which the British built.

It happened that the British enjoyed an important advantage. By far the best steaming coal in the world came from Wales and was controlled by British companies. Protecting overseas stores of this coal, which were mainly in British-controlled harbours, would go a long way towards immobilising raiders. In this sense the direct defence of British colonial harbours was a means of trade protection.

The focal area strategy was never made public, because implicit in it was acceptance of heavy early losses in exchange for the destruction of the enemy raiders. The problem would be solved in the first months of the war. This may seem bizarre. In fact in 1960 the US Navy’s position on trade protection was that it would be compelled to accept losses of about 100 merchant ships per month for the first three months of a naval war against the Soviet submarine force, during which time the Soviet force would be destroyed. The US strategy involved some convoying, but it was assumed that convoy would be ineffective against modern submarines. The emphasis was on blocking choke points and hunting using long-range detection. This was very much reminiscent of pre-First World War thinking about trade protection.

Pre-dreadnoughts were much more vulnerable to underwater damage. HMS King Edward VII sinks after being mined off Cape Wrath on 6 January 1916. In much the same way, the German pre-dreadnought Pommern was lost to a single torpedo hit the night after Jutland, but German dreadnoughts survived multiple torpedoes. (SPC-A)

Unfortunately an attacker did not have to match the Royal Navy’s numbers; it could build a few cruisers which could overmatch the focal-point ships. In the 1890s new lightweight steels made it possible to build fast armoured cruisers. Focal-point cruisers had to deal with whatever came their way. Armoured cruisers had other roles, too, such as fleet scouts and screens, but probably trade protection was the most punishing financially for the Royal Navy. By 1904 the British policy of maintaining a sufficient edge over the next two naval powers (France and Russia) meant maintaining a 2 to 1 advantage in armoured cruisers, presumably meaning roughly equal numbers as fleet scouts and as trade protection ships. To fill the focal areas the Royal Navy needed about as many armoured cruisers as it had battleships. Unfortunately a big armoured cruiser cost about as much as a battleship.

The Royal Navy was the single largest item in the British budget and the budget exploded with the rise of armoured cruisers. In 1896–7, before the British began building such ships, the British national budget was £101.5 million, of which £23.8 million (23.4 per cent) went to the Royal Navy. In 1904–5 it was £142 million, of which £41 million (28.8 per cent) went to the Royal Navy.3 The 1904–5 figure was worse than it looked, because the total budget was still swollen by increased army expenses related to the Boer War. The British sought an ally for the first time in their peacetime history at just this time, surely to balance off part of the Franco-Russian cruiser threat to British trade, the lifeblood of the Empire. The British first approached the Germans (as a counter to France), but found their terms unacceptable.4 The alternative was Japan, which could neutralise the Russians in the Far East. The Russian Far East threat was not so much to important British possessions (mainly Australia and New Zealand at this time), but to Far Eastern, including Indian, trade using large long-range cruisers.

Even with the Japanese alliance, the British faced a large French cruiser force, which could be based outside European waters the Admiralty might hope to control. The financial crisis was not quite as bad, but it still loomed. ‘Jacky’ Fisher was brought to the Admiralty in 1904 to solve it. He realised that if there could never be enough cruisers to fill out the focal areas, then enemy raiders would have to be hunted down. However, if the Admiralty kept track of British trade it would also be keeping track of losses to enemy cruisers. On that basis it could direct cruisers to hunt down the raiders. The new W/T technology would make direction more efficient. Fisher reorganised the Trade Division formed in 1901 as a trade tracking centre, the forerunner of a related ocean surveillance operation. These initiatives built on Fisher’s experience as Mediterranean C-in-C, using code-breaking to predict the movements of the French and Russian fleets he faced.

As long as the Germans relied on cruisers (including armed merchant cruisers), the policy Fisher had developed worked. It took enormous effort to hunt down some of the cruisers, but they did not last long. The Germans later enjoyed some success with disguised armed merchant cruisers like SMS Moewe, because even when spotted they could not necessarily be identified as warships by the cruisers hunting them. As an immediate defence while the German cruisers were hunted down, the naval war college recommended dispersal, as raiders relied on known trade routes to find their quarry. Dispersal might be the best protection. When war broke out in 1914, among the first Admiralty instructions to merchant ship owners was to shift away from the established routes.5

The great surprise of the First World War was that a particular kind of raider, the submarine, could pass right through any barrier created by surface forces. For U-boats, British supremacy on the surface of the sea was irrelevant – unless, as at Zeebrugge, it translated into an ability to destroy the submarines in their base. At the outset submarines were not counted as viable commerce raiders because they could not be used effectively without violating internationally-understood rules of war.

It proved possible to protect a ship against underwater damage by bulging, building protective structures outside her hull. Four Edgar class cruisers were the first British warships to be blistered (they were the only cruisers so modified). This is the bulge built onto HMS Endymion. The bowsprit was part of a bow protection device against mines, a predecessor of the paravane. The four modified Edgars went to the Dardanelles, where they were considerably more survivable than the pre-dreadnoughts previously sent there. None of the pre-dreadnoughts were bulged and the shipyard effort involved was too great to allow installation on board existing Grand Fleet capital ships. However, in May 1915 permission was given to bulge the incomplete Ramillies. Her sister-ships Revenge and Resolution were later fitted (in, respectively, October 1917 – February 1918 and late 1917 – May 1918). Surprisingly, the bulges in these ships did not cost speed. The Renowns and the ‘large light cruisers’ were all built with ‘internal’ bulges which did not cost speed.

Tactics: Gun and Torpedo

In the 1890s tactics often meant fleet manoeuvring in elaborate patterns (a well-known photograph of the time showed the British Mediterranean Fleet battleships executing the ‘gridiron’, in which lines of ships passed through other lines). By 1914 tactics meant how to manoeuvre a fleet so as to destroy or evade another fleet. The large numbers of the past had given way to smaller numbers of individually much more powerful ships.

Gun and torpedo ranges both expanded enormously during the pre-war decade. Fleets spread out. As a result, the battle space expanded to the point where an Admiral on his bridge could no longer easily see or understand what was happening. Even if he could have seen all of his ships under good conditions, in combat his vision was badly compromised by the combination of funnel smoke (inevitable for coal-burning warships) and gunsmoke. That combination was first really experienced at Tsushima in 1904.

In 1914 only the Royal Navy had the slightest idea of how to solve the problem. Commanding the Grand Fleet, Admiral Jellicoe adopted a suggestion by his fleet gunnery officer Captain Frederic Dreyer that he use a plot to visualise the positions of his own and enemy ships. In effect it was a small-scale equivalent to the strategic plot being developed at the Admiralty, first to visualise trade patterns (and find raiders) and then to control a fleet operating in the North Sea.6 Plotting had an unsuspected consequence. It was impossible to reproduce the flagship’s plot precisely, even if all the ships in the fleet were maintaining their own plots. Only the fleet commander, looking at his plot, could draw the implications needed for command. The plot did make it possible for the commander to assign, for example, a fast division where it might be needed, but it did not provide for him to devolve command to divisional commanders – who would not have sufficient plots of their own. The plot, moreover, made the C-in-C hostage to the accuracy of the information provided by his ships, which acted as his sensors.

Successful plotting involved not simply the location (at some particular time) of an enemy force, but its course and speed, so that it could be projected ahead and appropriate action taken. At Jutland, as Beatty’s Battlecruiser Fleet fell back on the supporting Grand Fleet, Jelicoe’s signalman asked for the enemy’s course and speed. Beatty, who seems not to have understood how important that might be, could signal only the direction to the enemy, which did not really help. Jellicoe managed to learn enough, probably from the smoke of the German fleet on the horizon, to estimate their course and speed and his simple plot made it possible for him to deploy his fleet on the appropriate course. The achievement was not only that he crossed the enemy’s T, but also that he avoided the entirely possible head-on approach which would have been so dangerous, at least in his eyes.

Jellicoe certainly realised that plotting required that his ships, particularly his scouts, report regularly and that they give the positions of the enemy ships they spotted. His wartime orders emphasise the need for including their own positions when reporting. However, plotting as a tactical information system appears not to have been tested before Jutland. Jellicoe seems not to have understood how much testing tactical plotting demanded. Perhaps the great surprise was that without precise navigation plotting could not be effective. As early as 1906 a British cruiser admiral pointed out that using W/T for scouting (i.e., abandoning chains of ships repeating back to the flagship) carried risks because reported positions might well be several miles off. That might not matter too much, because in a coal-burning era all ships smoked (though the Royal Navy’s Welsh steaming coal smoked less than most), hence could be seen beyond the horizon. However, ultimately what mattered was a series of reports on the same enemy ships by different scouts. The plot made it possible to combine such data to deduce the course and speed of the enemy. The results made sense only if enemy positions were indicated consistently. Otherwise the plotter would deduce an altogether wrong course and speed. Unfortunately the point of the plot was to predict where the enemy was going, which depended on his course and speed. The most famous aspect of Jellicoe’s plot at Jutland was its use to estimate the threat posed by enemy torpedoes. Several officers were detailed specifically to plot torpedo tracks and Jellicoe kept their plot within sight. Later it was suggested that errors in plotting made him overestimate the threat.

Failure always teaches more than success and Jellicoe learned a great deal from the failure of the attempt to intercept the German fleet after their Scarborough Raid in November 1914. The British light cruisers – the fleet’s scouts – made contact but failed to report it properly. Cruiser commander Commodore Goodenough disengaged due to a poorly-drafted signal sent by Admiral Beatty, who wanted to detach one of his cruisers to screen him against German destroyers he might encounter. Scarborough was the first success of British signals intelligence and Jellicoe, Beatty and Churchill thought it might well be the single golden opportunity to destroy the German fleet. Jellicoe and Beatty fastened on the cruiser failure, because had the cruisers held contact the battleships could have followed up. In one way the problem was the peacetime assumption that the force commander knew all and had to be obeyed. In another it was poor understanding of the full role of a scout, the most important part of which was full reporting of the enemy’s position, course, speed and composition. Commanding the British battlecruisers, Admiral Beatty was all for dismissing cruiser commander Commodore Goodenough in favour of one of his battlecruiser captains. Fortunately Goodenough survived to render excellent scouting service at Jutland. His failure at Scarborough explains numerous injunctions in Jellicoe’s fleet orders demanding reliable reporting by scouts.

Before Jutland, Admiral Jellicoe did his best to ensure that his scouting captains would report enemy positions and courses, so that he could form a full tactical picture. All Grand Fleet warships were required to maintain plots, on the basis of which they could (and should) report. However, the system was apparently not tested during fleet exercises, so Jellicoe was unaware of the dramatic effects serious navigational errors could have. Given bad data, the plot on his flagship could easily show ships doing impossible things – appearing to make 60 knots, say, or no more than 3 knots. Jellicoe may have suffered particularly badly from slapdash navigation on the part of ships of the Battlecruiser Fleet. After Jutland ships were required to maintain plots in terms of distance and bearing from the flagship, rather than in absolute terms of position. The use of relative positions largely solved the problem, except for ships, such as distant scouts, reporting from beyond the horizon.

Contemporary documents reveal no discussion of plotting or its profound implications and historians of Jutland have mentioned it only in passing. However, the Grand Fleet analyses of fleet exercises in 1918 always included a section on Navigation and Plotting, evaluating ships’ performance in this vital subject. For all the navies allied to the British, tactical plotting must have been a revelation. All of them adopted plotting post-war and it proved key to the night battle tactics used successfully by the British and the Japanese during the Second World War.7 The Germans had no equivalent. A neglected aspect of the battle of Jutland was that German commander Admiral Scheer continuously felt confused as he tried to extricate his fleet from the British. He had, it appears, very little sense of where ships were.

British wargame rules indicate what heavy guns were expected to do. British officers were familiar with them because they were used to evaluate success in frequent tactical (PZ) exercises. As of 1912 British exercise rules (quoted in instructions Admiral Jellicoe issued for tactical experiments) assumed that at 10,000 yds it would take 75 minutes for a modern battleship (like HMS Hercules) to disable another such ship. At 15,000 yds, it would take 300 minutes – five hours, an unimaginably long time. Yet 10,000 yds was the sort of range sought to keep battleships out of torpedo range of each other. It is no surprise that the Royal Navy became interested in concentrating the fire of several ships. Admiral Jellicoe credited torpedoes with 10,000 yds range at 30 knots – a distance they would cover in ten minutes. It must have seemed impossible that any battleship, or even any pair of battleships, could deal with her opposite in line that quickly. These figures are enough to explain why the Royal Navy adopted heavier guns. Official wargame rules issued in July 1913 took 12,000 yds as the maximum range for 12in and 13.5in guns.8 According to these rules it would take about 20 minutes for one King George V to neutralise another at 7000 yds and about 26.5 minutes at 10,000 yds. These rules reflected what British naval officers thought would happen in battle. The rules imply that even at 7000 yds it would take a long time to destroy an enemy battleship. The great wartime surprise, particularly at Jutland, was that gunfire did not have to be cumulative to be effective. The destruction of three British battlecruisers by what appeared to be single hits shocked not only the British but also the Germans. Later it turned out that horribly flawed British magazine practices had made these hits as effective as they were.

During the period after 1904, the Royal Navy sought longer and longer gun ranges so that its battleships could fight outside the range of torpedoes fired by enemy battleships. Ultimately North Sea weather limited gun range most of the time, but torpedoes kept improving. Trials in 1908 showed that a lengthened 21in torpedo could reach 10,000 yds at 30 knots and Jellicoe assumed this performance in tactical trials he conducted in 1912. The 21in Mk II which equipped British battleships in 1914 had a range of 10,000 yds at 28 knots. The German G7 was credited with 10,000m at 27 knots.

It proved difficult to keep increasing gunnery range whatever the weather. British fleet performance in 1911 was so disappointing that a special gunnery conference was called. In 1912 Battle Practice range was decreased from 9000 to 8000 yds. No explanation was given, but shorter ranges would have been consistent with the belief that North Sea conditions would make longer ones irrelevant. Partly as a result of reducing range, the eight best ships made better than 30 per cent hits in 1912, whereas in 1909 the fleet average had been about 20 per cent. Apparently existing gunnery techniques had reached their limit. It would take considerable investment in new technology to maintain the hitting rate while much raising Battle Practice range – which measured the fleet’s capability. The fleet would usually fight at or inside typical Battle Practice ranges. That was not to deny that, under good visibility, it might open fire at greater ranges.

One of the great wartime surprises was that the battles were fought at long ranges because fleets were unlikely to get into contact except when visibility was excellent. The failure to engage after the Scarborough Raid is a case in point: contact was lost partly due to poor weather (and partly, it should be added, due to a gross signalling blunder on Admiral Beatty’s part). That ships could and would engage at great ranges particularly surprised the Germans, who had justified a policy of using smaller-calibre higher-velocity guns on the basis of expected short North Sea ranges.

The 1911 Admiralty conference did not mention it, but by that time the Royal Navy was developing a new kind of analogue computer fire control under contract to Anthony Hungerford Pollen. Pollen’s Argo Clock modelled the firing situation to predict the range and bearing to which shells should be fired. Although Pollen had a monopoly contract, the Admiralty was also supporting an analogous system under development by its rangefinder firm, Barr & Stroud. Gunnery officer Frederic Dreyer was promoting a much simpler device which used a geometric approximation to predict range, without any modelling. In 1912 plans called for comparative trials of the Argo Clock and the Dreyer Table, but they were never carried out. Instead, the simpler and far less expensive Dreyer Table equipped most British ships during the First World War. It was a variation on the device most navies used to predict range: a ‘clock’ fed with the measured or estimated rate at which the range was changing. If the rate itself did not change very rapidly, using a constant rate was not too bad an approximation. The more sophisticated analogue computer was more flexible and it could allow for manoeuvres by the firing ship. During the war the US Navy adopted the modelling technique in the form of the Ford Rangekeeper, which seems to have been derived from the Argo Clock. The Germans used a simpler range clock fed with an estimated range rate.

Jellicoe seems to have opted for longer range despite reduced effectiveness. As commander of the Second Division of the Home Fleet in 1910–12, he issued war orders: if weather permitted he would open fire at 15,000 yds and develop maximum fire at 12,000 to 13,000 yds. He expressly cautioned against going inside 7000 yds, for fear of torpedoes. Apart from his 13.5in superdreadnoughts, Jellicoe’s fleet could not achieve much very rapidly at 10,000 yds.9

In October 1913 Home Fleet commander Admiral Sir George A Callaghan issued war orders envisaging opening fire at 15,000 yds (if weather permitted), closing to a ‘decisive range’ of 8000 to 10,000 yds where superiority of fire might be established.10 Ships might press home attacks at shorter ranges. No one had yet tried really long-range firing. Callaghan called for experiments to determine maximum effective range. The only ones he was able to run before the war were at about 14,000 yds. This figure is interesting because explicit war orders seem to have assumed that the fleet could fight at much greater ranges – as in fact it did during the war.

Both Callaghan and his successor Jellicoe planned to open fire at a range beyond that it which many shells would hit in order to establish ‘fire supremacy’. Having done that, they would close in to fire at a more practicable range. It would take a storm of shells to have the desired effect at that range. In order to allow for the wasted long-range shots, ships had to carry much more ammunition. To be able to fire steadily at long range, in 1913 Admiral Callaghan ordered ammunition added well beyond the usual eighty rounds per gun. In half an hour a gun might well fire sixty rounds and enough had to be left for the short-range action. Once war began, this likelihood that shells would be expended before ships closed to effective range became worrisome: surviving orders issued in 1914–15 explicitly warn against such waste. It must have been difficult both to urge gunners to open fire and not to waste. Yet there was no way to expand magazines.

Overloading magazines made for congestion at the bottoms of ammunition hoists. Extra cordite would crowd the spaces at the bottoms of the powder hoists. Supply to the guns would be anything but fast enough. Comments by German survivors of the Falklands battle must have encouraged attempts to fire faster. They said that slow British fire had made their gunnery easier. If a German ship was smothered in splashes, her gunlayers might well fail to hit altogether. Thus rapid fire was both an offensive and a defensive measure. Experience at Dogger Bank reinforced this view. Orders issued early in 1915 emphasised the need for rapid fire. Admiral Beatty sanctioned attempts to overcome congestion by drastically relaxing safety measures, with horrific effects at Jutland.

All of this left open the question of what to do if visibility precluded long-range firing. In that case the battleships would be within torpedo range and they would have only a few minutes of firing time until enemy torpedoes reached them. A battle line in close order was a perfect target for long-range torpedoes, because the ships in it filled so much of the line. These were ‘browning’ tactics. On land long-range guns fired, not at individuals, but ‘into the brown’, meaning into the mass of enemy troops. An enemy battle line could be imagined as an extended target. In order to concentrate its fire, its ships had to steam fairly close together – much closer than modern naval officers would consider safe. Perhaps 30 per cent of the total length of the battle line consisted of ships, which suggested that 30 per cent of ‘browning’ shots by long-range torpedoes would hit. Unlike shells, individual torpedo hits were expected to sink ships. ‘Browning’ shots figured in British destroyer instructions drafted in 1913.11

In The World Crisis Winston Churchill remembered that in November 1912 Second Sea Lord Admiral Lord Louis Battenberg warned of the threat of ‘browning’ shots from the German battle line. About a year later the danger had apparently receded.12 In Vol III of his history (1927) Churchill summarised what he remembered of pre-war expectations: first the British would smash the German fleet, then they would evade any torpedoes the Germans had launched. Evasion meant following a standardised signal, a blue pennant which ordered each ship to turn away from the enemy line. Ships’ fire-control solutions would inevitably be ruined by so radical a turn. Whatever damage they would do would have to be done during the ten minutes or less between coming into torpedo range and turning away.

Churchill’s account probably reflects what he was told when serving as First Lord before the war. Smashing means neutralisation. Even at 10,000 yd range, it would take a German torpedo only about ten minutes to reach the British line. Churchill associated the tactics he described with a half-hour engagement. The half hour could well mean a battle opening at much longer range, including an approach phase lasting as much as twenty minutes. During that time the British would try to achieve the ‘fire superiority’ Jellicoe sought. However, they would not begin to do devastating damage until the Germans came much closer. To do that they had to fire far more rapidly and more effectively than in the past, which suggests that they expected to use some new technique. A section hurriedly inserted in the wartime edition of the official Gunnery Manual describes a new means of rapid-fire control for medium ranges.13 It was not discussed after the war, as war experience emphasised long-range fire.14 An exercise Jellicoe conducted in October 1916 shows that by that time he was well aware of the battleship-to-battleship torpedo problem and that he did not consider it solved. The reason was the advent of really long-range torpedoes (15,000 yds or beyond).

When war broke out, the British lacked any proven capability to control guns at long range. That placed Jellicoe in a very different position when he took over the Grand Fleet. The fleet had been trained to fight at 8000 yds or less, well within torpedo range. Effective rapid fire at medium ranges was a future rather than a current proposition. In his initial Grand Fleet Battle Orders Jellicoe told the fleet that it would fight at long range. The British had long (correctly) believed that the Germans wanted to fight at much shorter ranges, where their heavy secondary batteries would be effective. Short range would also favour their favourite manoeuvre of passing torpedo craft through their line to attack the enemy during a gun engagement, not least to break up the enemy line. After the war it seemed that Jellicoe had concluded that since the Germans wanted to fight a close action, it would be advantageous to fight at longer-range, to ‘develop and practise the game of long bowls’. It also seemed that Jellicoe had decided to concentrate completely on gunnery.15 Jellicoe’s avoidance of torpedo range made sense. His pre-war experience as DNO and then Third and Second Sea Lords made him painfully aware of the failure of British attempts to develop underwater protection. He believed, again correctly, that the Germans had done much better. His only superiority over the Germans was in long-range heavy gunnery. He was also aware that gunnery, particularly at long range, could not give decisive results in the time available.

Jellicoe had no particular reason to imagine that ships and materiel which had struggled to hit targets at 9000 yds could suddenly hit at 50 per cent greater ranges. His August 1914 draft tactical orders envisaged deploying at 16,000 yds, but opening range was dropped from Callaghan’s 15,000 yds to 9000–12,000 yds (which he described as long range).16 Jellicoe expected to benefit heavily from British gunnery superiority at such ranges. These orders suggest that Callaghan’s longer-range test firings were less than successful and, moreover, that Jellicoe expected decisive range to be something like 6000 to 8000 yds (no decisive range was cited in the draft orders). A few weeks later Jellicoe issued a radically different Addendum No. 1 to Grand Fleet Battle Orders envisaging opening with 13.5in guns at 15,000 yds and with 12in guns at 13,000 and at even greater ranges should the enemy fire first. Ships would shift to rapid fire at about 10,000 yds. The orders were extraordinary. Almost nothing had been done to practice such firing.

The blister could be badly torn up without endangering the ship. This is damage to HMS Endymion.

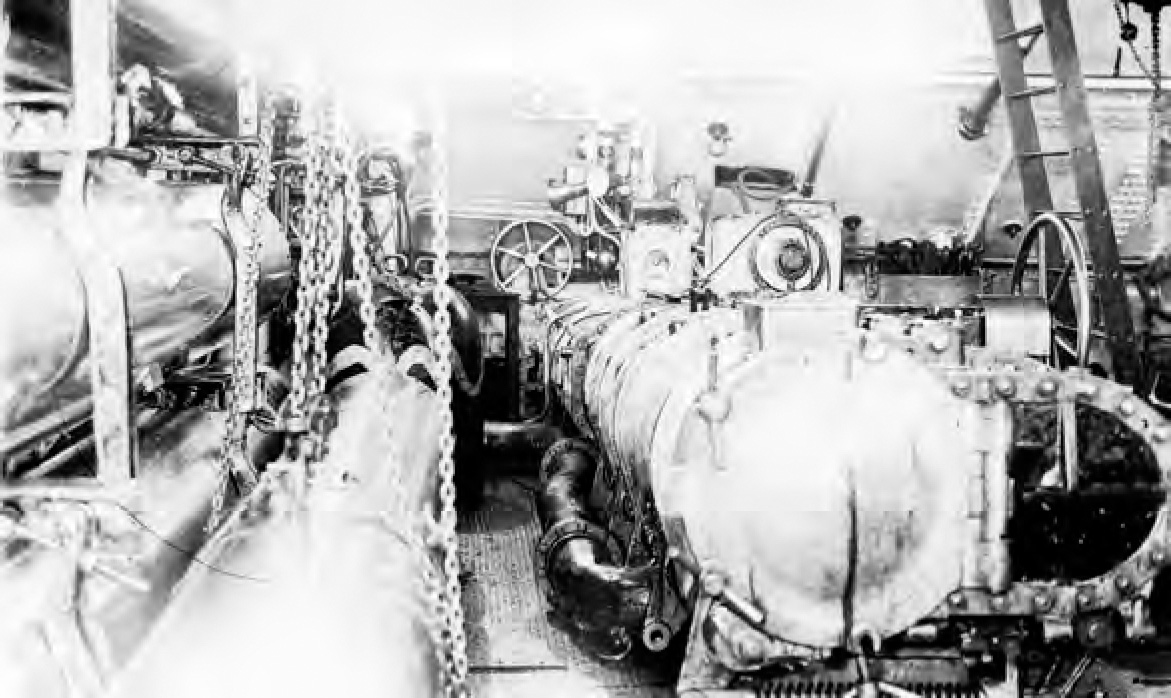

Torpedoes armed many kinds of ships, from capital ships down. Pre-war tacticians had to take into account both torpedo fire from an enemy battle line and possible torpedo fire from enemy destroyers and light cruisers. This is the torpedo room of HMAS Australia. (Josef Straczek)

Jellicoe did not intend to open fire beyond 18,000 yds unless the enemy did so, or the conditions required it – as in a chase, which occurred at Dogger Bank. Ships must always be ready to fight at extreme ranges. Jellicoe’s April 1915 gunnery orders show that to do that he relied on the pre-war technique of bracketing to find the range, which meant not firing the next salvo until the first had splashed and been spotted. Thus at 18,000 yds a 13.5in ship could fire salvos at 50-second intervals (at 12,000 yds, 40 seconds). Once the range had been found, ships would shift to ‘rapid salvos’, the next salvo being fired as soon as guns were ready. Any spotting corrections would be applied to a later salvo. Heavy guns could fire at least two such salvos each minute. Jellicoe’s April 1915 instructions envisaged accelerating to a salvo every 20 seconds once spotting could be discounted (as in rangefinder control). The maximum range envisaged was at least twice pre-war range. Except for directors, nothing had been added to improve performance. Jellicoe later wrote about how hard he had worked the fleet to improve its long-range performance. He was fortunate in having the Moray Firth in which to fire (Beatty’s battlecruisers had no such practice area). In 1915 they fired at least twice at 16,000 to 17,000 yds.

Jellicoe’s most significant change to Callaghan’s battle orders was to assign the two leading pairs of British battleships to concentrate on the two leading German ships (if the fleets were on opposite courses, the two rear pairs would attack the German van). The idea that concentrated fire could break up the German formation became more important after Jutland and was an important post-war theme in British naval tactics. It backfired to some extent at Dogger Bank, when the captain of HMS Tiger interpreted it to mean that he should fire on the leading German ship instead of on the ship opposite him. Post-Jutland British fire-control developers accepted that hits would be few and involved new types of salvo firing and spotting designed to make the most of whatever opportunities arose. Pre-war concepts involving rate measurement were abandoned.

After the war many British naval officers expressed their disappointment in Jellicoe’s performance at Jutland: why had he failed to come to grips with the Germans? Surely he could have achieved more at shorter ranges. In fact it did not much matter what ranges Jellicoe wanted to adopt. He fired as soon as he could, as the Germans approached and his fleet did not have all that long to fire before the Germans tried to disengage. Jellicoe could have chosen the range only if he had much faster ships.

Soon after war broke out, Jellicoe wrote in his battle orders that he sought action on parallel courses because he thought it would give the most decisive results and because it would avoid the danger of German minelaying: the Germans would not run their own fleet (alongside the British) into a minefield they had laid.17 This was striking because the object of deployment as developed as early as 1901 (and as practised by Jellicoe at Jutland) was to lay the fleet athwart the path of the enemy fleet, crossing his ‘T’. Jellicoe’s preference for parallel courses may have been tied to his fire-control capability. The closer the enemy course paralleled his, the lower (and less variable) the range rate and the simpler the fire-control problem. Jellicoe almost certainly associated a low range rate with a high hitting rate. One of the nightmares considered by his officers just before the war was a German reversal of course, which would greatly increase the range rate.18 Not only that but a fleet on the opposite course would enjoy greater effective torpedo range, because the opposing fleet would be running towards its torpedoes as they ran through the water.

The Germans apparently expected to fight at much shorter ranges. It was generally understood that the Germans considered their gunnery most effective at medium range, about 6000 yds. Evidence included the fact that they had retained medium-calibre (5.9in) guns on board their dreadnoughts, at a cost in weight (for armour or for main-battery guns), on the theory that the smaller faster-firing guns could contribute usefully in a fleet action. As if to confirm British guesses, in his 1915 tactical orders (which the British obtained) German fleet commander von Ingenohl announced that he expected to fight at 6600 to 8800 yds (presumably a translation of 6000 to 8000m).

The Germans had to get to their preferred battle range while the British shelled them from greater ranges. They adopted a tactic of evasive action (zig-zagging) while closing the range, on the theory that it would defeat any British attempt at measuring rates. German comments on British tactics strongly suggest that they were aware of British reliance on plotting to measure rates Because their rate estimates did not involve sustained plotting, the Germans could still exercise effective fire control while manoeuvring Zig-zagging frustrated British fire control, particularly at Jutland and after that battle the British changed their fire-control practices to deal with it. Ironically, a British officer proposing tactics pre-war had suggested exactly this technique, pointing out that fire control would still be possible from a ship moderately zig-zagging, whereas her manoeuvres would frustrate conventional fire control used against her.19

Torpedoes could turn a small ship into a giant-killer. Before the war, that meant destroyers and submarines. During the war, the advent of powerful aircraft engines made it possible to build very fast torpedo boats. The first were built in Austria-Hungary, but the British CMBs (Coastal Motor Boats) saw much more action. CMB 3, a 40-footer of the initial batch, runs trials. Her hard-chine hull form was based on that of pre-war racing boats. (Dr David Stevens, SPC-A)

Until about 1911 the Germans seem to have thought that by adopting high range rates as they approached the British, they could avoid almost all damage. Then they realised that might not be sufficient protection. If they could fire on the way in, while the range was changing, they might make British fire control ineffective. Observing the Germans, in 1914 the Russians noted that the Germans emphasised radical changes of course and high range rates in their exercises. After Jutland, the Germans told the Austrian Naval Attaché that in their exercises they had always worked with big and rapid alterations of range and exercise firing while turning. They thought the British relied too much on range clocks and hence on measured range rates, which required that they maintain a steady course. In the autumn of 1914 British naval intelligence published the secret German report of gunnery practice for 1912–13.20 The Germans had recently begun practicing long-range firing under ‘difficult conditions’, at ranges of 11,000 yds and above. The longest range for any of the capital ships was 15,000 yds. For example, the recent battleship SMS Kaiser had fired at 14,000 yds down to 13,500 yds at a closing rate of 43 yds/min. Typical results for heavy ships were 9.2 per cent hits at 12,000 yds.

It is not clear why, without a much higher speed than the British, the Germans thought they could ever close the range, whatever damage the British could or could not do. During the inter-war period, the Royal Navy considered medium range (about 15,000 yds) best and had to solve the Germans’ problem, of how to survive while closing an enemy which could hit at much greater range. Among other things, it hoped to use mass destroyer torpedo attacks to help force an enemy into position. The one problem it could not solve was that its battle line was significantly slower than that of its most likely enemy, Japan (this particular problem was unsuspected, as the British did not realise that the Japanese had greatly increased the speeds of their battleships during reconstruction).

Once war broke out, the Germans concentrated on the tactics they had developed to minimise their chances of being hit; their mind-set was fundamentally defensive. They employed the tactics they had designed to get them into fighting range without being destroyed on the way, then stopped closing well before getting there. Thus battle ranges were almost always much longer than the Royal Navy had practiced before the war. The Germans had never expected to achieve much en route to decisive range. The destruction they wrought at Jutland was a surprise as much to them as to the British.

The torpedo was radically different from the gun. Each shot was much more lethal, but at long range hitting was far less likely, because the torpedo took so long to reach its target. The navies of the First World War dealt with two dramatic changes in the torpedo. One was the gyro, which ensured that a long-range torpedo would run more or less straight. The gyro could also be set to turn the torpedo away onto a pre-set angled course. Navies differed as to how valuable this feature was, because it required more sophisticated fire control and also because it might make for reduced reliability. The other was the ‘heater’, a form of internal combustion which dramatically increased torpedo range. By 1914 ‘heaters’ had boosted maximum range from perhaps 1000 yds (1900) to about 10,000 yds or more. Even well before 1910 navies were taking the torpedo seriously as a complement to or even an alternative to guns. The US and Russian Navies and possibly others, seriously considered capital ships whose main batteries would be large numbers of torpedoes. Some British ordnance experts suggested that now the torpedo might be used alongside the gun in a fleet action. It was, however, generally accepted that even a gyro torpedo had limited accuracy at full range.

The torpedo turned a destroyer or even a motor boat into a giant-killer – as the Italians demonstrated when they sank the Austrian battleship Szent Istvan in 1918. During the run-up to 1914 admirals had to take into account torpedoes on board both battleships and destroyers (designated torpedo boats in the German navy). The British Mediterranean Fleet integrated torpedo-firing destroyers into its formations beginning about 1900, but as First Sea Lord Admiral Fisher (who had originated the Mediterranean tactics) argued that destroyers should be used independently to dominate the narrow North Sea. The British imagined, wrongly, that the Germans planned to use their destroyers similarly.

Pre-1914 navies treated destroyers not too differently from the way later navies treated aircraft. Discussing fleet torpedo boat tactics, a US Admiral later wrote that of course any battleship which spotted an approaching torpedo boat (or destroyer) would open fire. Waiting for a positive identification would be too dangerous. The surface torpedo firing zone grew rapidly in the years between 1904 and 1914, making the identification problem less and less tractable.

The situation changed after Fisher left the Admiralty and reports that the Germans were integrating their destroyers into the Grand Fleet gained currency. The Germans practiced a showy manoeuvre in which destroyers on the unengaged side of their battle line passed between their battleships to attack the enemy battle line during the gun action between the two lines. Initially the British reaction was derisory. It would be far more efficient to attach destroyers to the van or the rear of the fleet, to disrupt the enemy line by concentrated attacks on his van or rear. Destroyers venturing into the space between the two fleets would make few hits and would probably be wiped out. However, the German attacks could disrupt the British formation, ruining its gunnery: the German torpedo tactic could be read as a tactical gunnery countermeasure. Until this point, the British saw destroyers as a threat entirely separate from a day gun battle, so their capital ships had their anti-destroyer guns atop their turrets. They switched to protected positions and new capital ships, beginning with the Iron Duke class battleships and their battlecruiser equivalent, HMS Tiger, had more powerful anti-destroyer guns.

To see what the Royal Navy should do, in 1909–10 Home Fleet commander Admiral William H May conducted exercises.21 As in the past, he was interested mainly in using destroyers to finish off enemy ships crippled during a gun action, as Admiral Togo had planned to use his own destroyers at Tsushima. Only if weather was misty (visibility less than 8000 yds) could they get close enough to an undamaged and unengaged enemy fleet to attack it before the gun action. However, May did take account of the new long-range torpedoes, which could be used in ‘browning’ shots against the enemy line rather than against individual ships. In his exercises, destroyers suddenly emerging from the mist made ‘browning’ shots at 3000 yds.

An exercise seems to have demonstrated the value of ‘browning’ rather than close-range aimed attacks. White’s destroyers emerged from the mist and attacked as Black’s fleet began to form battle line out of cruising columns. During that manoeuvre the enemy fleet could not turn away to evade ‘browning’ shots by the attackers. He would have to rely either on counter-attack by his own destroyers or on his battleships’ fire – in which case the battleships might be unable to engage the opposing British battleships. At the least, dreadnoughts would have to assign one turret to anti-destroyer fire, reducing their effective broadsides.

The destroyers could have made a successful ‘browning’ attack, but in order to hit particular ships they came too close to Black’s ships. Black would have been unable to form his battle line unless he had light cruisers to beat off this attack. There would be no time to call the cruisers forward if they were not already present on the wings of the battle fleet. May concluded that in misty weather the destroyers should be well up on both wings of the battle fleet.

If a fleet had already formed, its battleships could turn away together – but that might well lead to great confusion. Once the fleets were engaged, the enemy battleships would be concentrating their efforts on the British battle line. Small ships might not even be too visible in a haze of gun and funnel smoke. Running at maximum speed, destroyers might well survive until they fired. Again, May envisaged ‘browning’ rather than short-range aimed shots. To avoid being sunk (wasting their torpedoes), destroyers should be able to fire as soon as they came under enemy fire.

Once the battle had begun, destroyers approaching the enemy fleet had to pass through a danger zone extending from 1000 yds in front of the British line to 2000 yds beyond it, but they would be fairly safe from attacks by enemy light cruisers. A run from the end of the British line would place destroyers in the danger zone for longer (nine minutes in the worst case), but it would hamper the British line far less than the pass-through.

CMB 4 is preserved at the Imperial War Museum at Duxford to remember the great successes CMBs achieved in the Baltic during the British intervention against the Bolsheviks in 1919. The single 18in torpedo was stowed in the trough, head first. A piston, which has not survived, pushed it into the water tail first to launch it. The boat swerved out of the way of the accelerating torpedo. This arrangement made it possible to aim the torpedo (by aiming the boat). Although the cockpit appears to be nearly in the bow, it was actually well astern (abaft the step of the hull) and there was a machine gun position forward. The boat had a single aircraft-type engine driving one propeller. In February 1919 the British Secret Service asked Lieutenant Augustus Agar RN to run agents into St Petersburg. In June, Agar made the small harbour of Terrioki, three miles from the Russo-Finnish border, his base. It was 35 miles from St Petersburg. His two 40-footers were towed from Abo, Finland to Terrioki by the destroyer HMS Voyager. As Agar was setting up his base, the fortress of Krasnaya Gorka rebelled against the Bolsheviks and Agar decided to attack the Bolshevik cruiser Oleg. His CMB 4 sank the cruiser on the night of 17/18 June after having to stop for twenty minutes to replace the torpedo-launching cartridge. This was much the kind of attack the Harwich Force planned against the German fleet from 1916 on. Between 10 June and 26 August 1919, Agar made nine trips to St Petersburg to insert or pick up agents. Of his two boats, CMB 7 was seriously damaged on the last trip and had to be scuttled. Agar’s success led Baltic commander Rear Admiral Sir Walter Cowan to ask for more CMBs to attack the two battleships and one submarine depot ship in St. Petersburg. He received a small flotilla of 55-footers. On the night of 17/18 August Agar in CMB 4 led six 55-footers through the forts to the entrance to Kronstadt. They were preceded by an air attack intended to distract the defenders. Two of the boats were lost to enemy fire and a third to a collision, but the others destroyed the enemy fleet, sinking the battleships Petropavlovsk (hit by three torpedoes from CMB 31 and CMB 88) and Andrei Pervosvenni (one torpedo from CMB 88). Petropavlovsk was later raised and returned to service, but Andrei Pervosvenni saw no further service. In a further operation in September, CMB 4 and two 55-foot CMBs laid mines in the channel leading to the naval base of Kronstadt. Agar received the VC and the DSO. (Dr Raymond Cheung)

Most CMBs were 55-footers, as depicted by this model. Only the 40-footers could be transported on the davits of a light cruiser. A 55-footer could deliver two 18in torpedoes (or, in theory, one 21in) and it had a substantial anti-aircraft battery of two twin Lewis guns. This model also shows four depth charges. Note the twin rudders and twin propellers and the hard-chine hull form. Not visible is the step under the steering position. (Dr Raymond Cheung)

In wartime, given their limited endurance, destroyers could operate with the fleet if they returned to base every two or three days or if action were imminent. The limit would be strain on their crews. Destroyers could be replenished at sea, particularly with oil in ordinary weather.

The great problem was identification: because destroyers were potentially so deadly, battleship doctrine was usually to fire at any that were not positively identified as friendly. The only effective means of identification was to confine them to a no-fire sector. In cruising formation that might be the rear of the fleet. With action imminent, a squadron of destroyers could be stationed on either flank of the battleships (beam or quarter), with orders not to hamper the main fleet when it changed from cruising to battle formation. The best position would depend on whether the commander wanted an early or late attack, based on weather. To reserve destroyers for attacks once the action was fully developed, destroyers should occupy unexposed positions, for example on the unengaged side of the battle line, 2000 yds off. May envisaged them passing through gaps between divisions (the Germans passed between ships) or they might attack from the head or tail of the British line. In the latter case a well-placed cruiser at one end of the enemy line could pour fire into the destroyers as they approached.

Given the new heaters, battleship torpedo range now roughly equalled effective gun range. May wondered whether it would be worthwhile to risk destroyers in a day action when the battleships themselves offered more torpedo firepower. He concluded that the role of destroyers working with a fleet was first to attack with torpedoes and only then to frustrate enemy destroyer attacks. Cruisers and scouts were better anti-destroyer weapons in a fleet context. Given long torpedo range, destroyers should never fire towards their own fleet. Once separated, they should not close the British fleet, as the battleships would fire at them. They should return to their bases after attacking. Destroyers should never stay with the battleships after dark, as the battleships would fire indiscriminately.

It followed that destroyers operating with the fleet needed heavier torpedo armament, at the least twin tubes rather than single tubes plus single stowed torpedoes. It could even be argued that guns should be traded for more torpedoes. May’s successor Admiral Callaghan argued that torpedo attack supporting the fleet was the single most important destroyer mission, hence that torpedo armament should be emphasised over guns. Like May, he considered light cruisers his best defence against enemy torpedo attack. The Board initially swatted him down. In line with earlier thinking, it held that the primary British destroyer role was to kill enemy destroyers in the North Sea while operating independently off German destroyer bases. The German fleet might take some short-endurance destroyers to sea with it, but they would have to return to port quite soon for reliefs. British destroyers off the German coast would pick them off as they came and went, much as, four decades later, NATO envisaged submarines in choke points picking off Soviet submarines as they returned to their bases for fuel and torpedoes.

Callaghan was unconvinced. In the 1913 manoeuvres destroyers were unable to find each other at night; the entire concept of hunting in the North Sea was disproved. Thus Callaghan’s 1913 fleet orders envisaged deploying his fleet destroyers on the unengaged side of his line, half ahead on the beam and other half astern on the quarter. Whichever way the enemy line approached, half would be in position to attack. For Callaghan, light cruisers were the antidote to enemy torpedo attack. Destroyers should be used against the enemy’s battle line.22 New destroyers should be armed more heavily with torpedoes, their designs placing less emphasis on guns. This position was controversial for a time, but the destroyers planned for the 1914–15 programme would have had a heavier torpedo armament and lighter guns (because of the outbreak of war, the previous year’s more conventional class was repeated).

It was generally agreed that at sea light cruisers were the best antidotes to destroyers. The original torpedo-boat destroyers had been stationed off French ports in hopes that they could sight emerging enemy torpedo boats and run them down, all the while firing at them. Although they were poor gun platforms, they were the only warships which could stay long enough with a fast target to disable it. By way of contrast, any ship opposing an enemy torpedo attack would have only a brief chance to do so. A light cruiser was a far better gun platform than a lively destroyer. That is why Jellicoe’s predecessor Admiral Callaghan preferred to emphasise the offensive role of his destroyers. Jellicoe understood why, but he never felt that he had enough light cruisers. He therefore used his destroyers, which were very much second-best as defensive assets, to make up the numbers and his tactics did not involve mass destroyer attacks against the German battle line.

Battleships could also fire ‘browning’ shots, but the British emphasised attacks by other craft within a battle fleet. The same gunnery personnel were used either for gun fire control or for torpedo control on board capital ships. During his tenure with the Grand Fleet, Jellicoe pressed for increased torpedo range, mainly in hopes of giving his battleships a better ‘browning shot’ weapon. In the spring of 1916 the British provided battleships with a 15,000 yd setting. Until the end of 1915 the settings were 10,000 yds at 28 knots and 4000 at 44 knots. Readjustment responded to reports of longer German torpedo ranges (at Jutland, however, British torpedoes considerably outranged German ones).

Pre-1914 British knowledge of evolving German tactics was limited at best; the British tended to mirror-image. As the British developed the ‘browning’ concept, they assumed the Germans would do the same. The German tactical publications which fell into British hands after the outbreak of war showed, among other things, that the Germans regarded torpedoes as far too valuable to waste in ‘browning’ shots. Presumably that was because pre-war German naval economics, shaped by the Navy Laws, had precluded providing them in great quantities.

In practice torpedoes were much less accurate and reliable than they seemed to be in pre-war exercises. The theory of ‘browning’ shots was still valid, but it took many more torpedoes to execute them. ‘Browning-shot’ tactics were never used, although they were still destroyer attack doctrine in both the Royal Navy and the US Navy at the end of the war. The British never provided enough torpedoes on board their destroyers and cruisers to make effective browning shots. A major wartime surprise was that at long ranges torpedoes were so ineffective.

Torpedoes had other unsuspected limitations. Before the war it was assumed, at least by the Royal Navy, that submarines would close to 500 yds to fire, so as to be sure of hitting. In pre-war exercises, torpedoes were set to run somewhat deep so as pass under their targets. That hid the reality that a torpedo launched by a submarine submerged to periscope depth had to climb to reach its set depth and the climb took some time, hence distance. To hit a shallow-draught ship such as a destroyer, a submarine had to back off to something more like 1000 yds. The faster the target, the better the chance that she would miss at that range. Much the same might be said of a British submarine lying in wait to torpedo a surfaced submarine passing at fairly high speed.

Capital ships turned out to be tougher than expected. A pre-dreadnought might well sink after a single torpedo hit. Dreadnoughts and their successors were more difficult to sink. The Royal Navy lost a single such ship, HMS Audacious, to an underwater hit and she took a long time to sink – so long that it seems likely that better damage control and some minor improvements would have saved her. HMS Marlborough survived a torpedo at Jutland, although it can be argued that she was lucky in where it struck. German ships proved remarkably resistant to underwater damage. Multiple torpedoes eventually did sink the battlecruiser Lützow, but she had been pounded so badly that they were only part of the problem. During the war, DNC discovered a way of protecting ships against torpedo hits by blistering, but no Grand Fleet capital ship could be taken out of service long enough for that and the speed penalty due to blistering would have been unacceptable in a battlecruiser. The only Grand Fleet capital ships properly protected against torpedo hits were the two Renowns.

As the British built more and more battleships, a key question was how to use them en masse. By the 1890s they expected to fight in line ahead, so they devoted much attention to the problem of deploying from cruising formation (columns) into the line best oriented to the enemy – preferably athwart his course (crossing his ‘T’). When the President of the US Naval War College visited his British equivalent in 1909, he observed that this was the main problem addressed in its tactical game.23 The normal fleet cruising formation was three columns, the C-in-C heading the centre column. Cruisers were normally thrown out well ahead and on the flanks and the rear. A key factor was visibility range, which in 1909 at the War College was taken as about four miles (8000 yds) by day under average North Sea and Channel conditions, about ten miles in West Indies by day and two miles at night.

Fleet manoeuvre required extensive signalling and by 1900 the Royal Navy had a very elaborate signal book. In effect it was the vocabulary an Admiral could use to manoeuvre his fleet. The role of the Admiral’s flag lieutenant was to translate his commands into the language of the signal book. There was internal debate as to whether even the best signalmen could help an Admiral control a fleet in combat. In the 1880s Admiral Tryon argued that the fleet could not effectively fight because its signalling system would fail when stressed. He pressed for a radically simpler system which amounted to ‘follow the leader’ manoeuvres. The Admiral would simply indicate whether or not the fleet was to conform to his movements. It did not help that Tryon died when his flagship HMS Victoria was rammed while the Mediterranean Fleet manoeuvred to anchor in 1893. Contrary to his teaching, Tryon was attempting a particularly elaborate, if elegant, manoeuvre and he seems to have miscalculated the distance between columns of ships. Jellicoe, at that time a Commander, narrowly avoided drowning as Victoria sank. Presumably he was being given a particularly graphic lesson in the dangers of complex manoeuvring.

The British came to understand that the simpler the formation, the better the chance that it would work – in more modern terms, ‘keep it simple, stupid’. The simplest and most supple formation, it turned out, was line ahead, because maintaining it required little signalling. Although the Signal Book remained as elaborate as ever, line ahead was very much the kind of tactic Tryon envisaged. Line ahead had a long history under sail, but with the advent of steam navies tried many alternatives, including line abreast and line of bearing. Under sail, line ahead made for simplicity, but given short gun range it was impossible to concentrate fire on any one enemy ship. Each side in a line-ahead battle would deliver roughly the same weight of fire. Nelson broke the enemy line at Trafalgar specifically so that he could concentrate fire on particular enemy ships, breaking up their formation. He accepted the risk that they might be cut off and overwhelmed by an alert enemy. Was there a battleship-age equivalent to Nelson’s tactic?

Having tried alternatives, by the 1890s the Royal Navy returned to line-ahead close-order tactics, a position not shared by some other major navies. The British found that line-ahead tactics much simplified station-keeping and the line was less liable to be thrown into disorder. In any other formation, course could not safely be altered without any signal – at a time when signalling was likely to be slow and uncertain, if not impossible. Perhaps as importantly, a line-ahead formation seemed to solve the problem of distinguishing friend from foe. Anyone in line was a friend, anyone outside a foe. Problems would arise only if the line kinked (as during the night action off Guadalcanal in 1942), so that some captains thought they were watching an enemy breaking through. That was unlikely in daylight.

In 1914 the heavy gun was the dominant weapon, but it was assumed that its effect would be cumulative. Gunfire would pound ships but only rarely sink them. The British liked Lyddite shells because it appeared that the fumes they generated would incapacitate crews. No one imagined sudden explosions like those which sank three British battlecruisers at Jutland. Slow destruction, as of Graf Spee’s big cruisers at Coronel, or Blücher at Dogger Bank, conformed much more closely to expectation. Thus fleet tactics envisaged night attacks by destroyers after a day gunnery action, largely to finish off cripples. This fleet battle practice target gives some idea of the area over which shells were expected to hit (shells falling outside were not counted as hits). At about 8000 yds the Royal Navy expected better than 50 per cent hits and even then it did not expect to knock out modern battleships very quickly. This target was photographed on 29 September 1912. (Dr David Stevens, SPC-A).

This was logic, not fetishistic devotion to the traditions of the age of sail. When he conducted tactical experiments in 1910–11, Admiral May sought an alternative to line ahead, which he considered basically defensive. In his view a fleet in rigid line-ahead formation could not readily counter-attack. The alternative divisional organisation was inherently flexible and, it seemed, relatively easy to command. May saw it as inherently offensive. Also, it was far easier to exploit ships’ speeds when they were organised in divisions (no more than eight ships, preferably four). From a theoretical point of view (Admiral May’s phrase) divisional tactics were extremely attractive.24

The rub was what Togo had found at Tsushima: individual divisions had to be kept under sufficient control that they reinforced each other but did not accidentally fire at each other. The fleet C-in-C had to know a lot more about what was happening in the battle in order to do that. Devolving control to the commanders of the divisions was risky in a world filled with smoke. Jellicoe’s experience of tactical experiments in 1912 seems to have convinced him that it was too easy for the divisions to tangle and even to engage each other instead of the enemy. These exercises revealed another problem as well. The British believed that a modern battleship could survive under fire for a considerable time. In the 1912 manoeuvres enemy ships were not exposed to fire for long enough. The fleet needed some way of laying down sustained fire for much longer. To do that it had to remain in formation, shelling an enemy fleet which would presumably also remain in formation.

Jellicoe, and probably other British officers, came to see rigid control as insurance against a dangerous melee punctuated by torpedo hits. When he came to write his Grand Fleet Battle Orders, Jellicoe abandoned his earlier acceptance of decentralised command once battle began. He sought to maintain control throughout. Divisional tactics might be the best way to concentrate fire on parts of the enemy’s fleet, hence to achieve results in a reasonable length of time. Jellicoe later said that he would have adopted divisional tactics if he could have, but that he did not have enough time to train his fleet in them.

Divisional tactics were not quite the same as accepting that once battle began a C-in-C might no longer be able to exert full control and much would have to be done by those commanding the fleet’s divisions. That begged a question. Who would control fleet resources such as massed destroyers? Who would direct them so that they attacked only the enemy’s fleet and not a hapless division of one’s own fleet?

Deploying across the enemy’s path was the best possibility. The worst, which seemed entirely possible, was that the British and German fleets would approach head-on, both fleets being in line ahead. In that case the battle might well open with a salvo of German torpedoes fired towards the British fleet. Because the British would be running towards the torpedoes, their effective range would be increased considerably. A quick run past the Germans on parallel courses would never provide enough time for gunfire to be effective. Jellicoe believed that it also presented dangers. He wanted to get onto a parallel course steaming in the same direction, because only then would he have enough time to pour enough shells into the German ships. Having run past the Germans, he could turn behind them and pass through their wake. However, Jellicoe was aware of the Japanese use of floating mines and he had sponsored its British equivalent. What if the Germans had the same idea? The wake of the German fleet was the last place he wanted to be. What sort of manoeuvre would bring his battle line onto the desired parallel course, in the same direction, without exposing it to floating mines?

Jellicoe’s predecessor Admiral Callaghan, who championed offensive destroyer operations in a fleet context, wrote in his March 1914 battle orders that the tactics of a fleet consisting of three or more battle squadrons plus battlecruisers and many other ships were fundamentally different from those of a fleet of one or two battle squadrons.25 Probably a single officer could command the smaller fleet for much longer than a larger one. Surely the larger the fleet, the greater the need to decentralise. Callaghan thought that he could control approach and deployment, but once firing began he would have to devolve to squadron commanders, subject to general instructions. He hoped to be able to deploy quickly enough to establish superiority of fire. The objective would normally be the enemy’s rear, a departure from the earlier idea of deploying across the enemy’s ‘T’. Callaghan cautioned against ships being drawn off by an enemy fast division, which could break up his line. Presumably he had the German battlecruisers in mind.

Overall, the British tactical problem was simple to state but difficult to solve. If the British fleet were far more numerous than its German enemy, how could its apparently crushing numerical superiority be translated into tactical superiority? How could targets in the enemy battle line be designated so that all were covered and how could multiple ships concentrate their fire on the enemy? The more numerous the fleet, the longer the line. A very long line steaming more or less parallel to a shorter enemy line would overlap it, the ships at the end too far from the enemy to fire. British experiments in longer-range fire may have been intended specifically to solve the tactical problem presented by the ships at the ends of the British line. Breaking up the fleet into mutually supporting units (‘divisional tactics’) could solve the geometric problem, but not the tactical one.