![]()

THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR demonstrated the value of offensive mine warfare. Before the war only Germany and Russia were enthusiastic proponents of mine warfare. During the war, a single Japanese mine sank the Russian flagship Petropavlovsk (13 April 1904) and killed Admiral Makarov, the only effective Russian naval commander. A Russian minefield sank two of the six Japanese battleships on one day, 15 May 1904.1 Both navies used mines extensively, both in enemy territorial waters and further offshore. Numerous mines broke their moorings and were recovered. The war also demonstrated that there was no existing method of quickly clearing mines. The textbook methods were countermining, sweeping, dragging and creeping, but all of them took time and could not be carried out under fire.2

A distinction was drawn between offensive and defensive mine warfare. Offensive warfare, such as that practiced by both the Japanese and the Russians, meant laying mines in an enemy’s waters in hopes that his fleet would encounter them. That might mean a surprise minelaying sortie or a concerted attempt to use mines to blockade an enemy fleet. It also might mean an attempt to prevent merchant ships from using a port or a sealane. Offensive mines were necessarily relatively indiscriminate and that in turn raised legal questions about their use in non-territorial waters.3 In 1914 it seems to have been generally agreed that any minefields should be announced and that mines which broke loose from their moorings should be made self-neutralising within an hour. In theory this last convention limited the life of a drifting mine.

In theory, a mine offensive could bottle up an enemy fleet, but in 1914 it seems to have been generally accepted that mines could be swept (as indeed many were during the Russo-Japanese War). Unless a minefield was defended, an enemy could regain freedom of action as soon as he was aware of its presence. It seems not to have been understood generally that sweeping would be difficult and slow. The main example of a defended minefield was the Turkish field in the Dardanelles, which sank several Allied battleships. Attempts to sweep this field were frustrated by the guns which commanded it.

Defensive mining was an attempt to deny the enemy access to a port or to an anchorage. In 1903–4 the Royal Navy convinced the British Government to abandon the mine defence of ports in favour of an offshore defence by submarines (the beginning of Admiral Fisher’s flotilla defence concept for the North Sea). The Admiralty argued that it would be dangerous to employ both submarines and mines and that submarines could carry coast defence considerably further to seaward. Admiral Fisher, not yet First Sea Lord, seems to have been particularly active in pressing the pro-submarine argument. At roughly the same time the Royal Navy ceased work on defensive controlled mines for the sort of anchorage it might have improvised to support a blockade. Remote control of the mines would, in theory, have allowed friendly ships to pass safely.

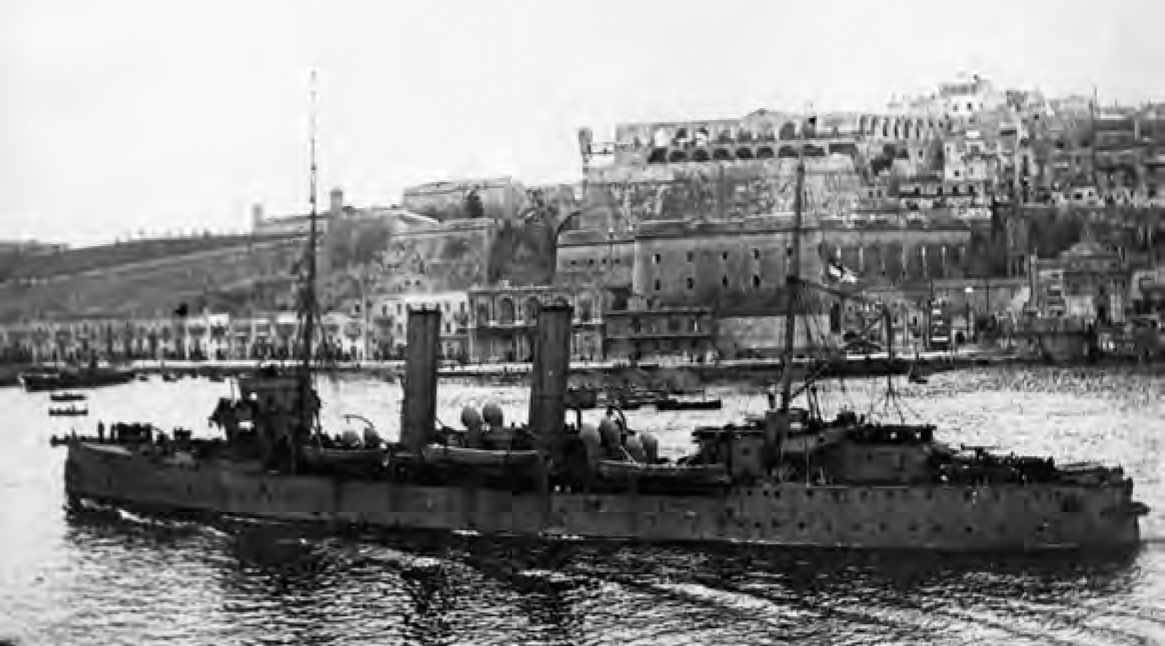

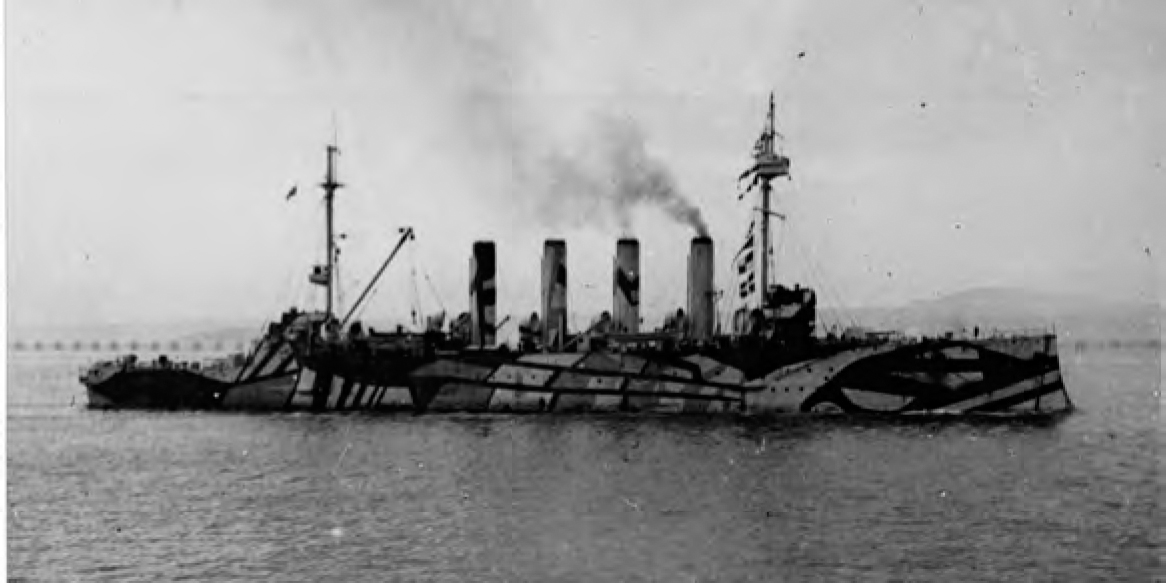

The first British reaction to the new importance of mines as demonstrated by the Russo-Japanese War was to convert seven obsolete Apollo class cruisers into minelayers. At the same time a new contact mine was developed; it was some time during the war before the Royal Navy to realise that it was less than reliable. Before that, mining policy was a matter of considerable debate. HMS Naiad is shown, newly converted.

Other navies continued to espouse controlled mines, particularly as an improvised defence for a forward anchorage. For example, before 1914 the main war scenario envisaged by the US Navy was defence of the Monroe Doctrine (which denied Europeans new colonies in the New World) against a European navy, most likely the Germans. The US fleet would rush down to, for example, the Caribbean to deal with the enemy incursion. It would improvise an advanced base, which would be defended by Marines ashore. The defence would include ‘naval defence mines’ laid by boats from the battleships.

The Russo-Japanese War dramatised an entirely different kind of offensive mine warfare, carried out by both sides using unprecedented numbers of mines. In its wake navies previously unenthusiastic about mining prepared to use it in wartime. The Royal Navy considered the use of mines on the most important lessons of the war.4 It decided to buy a supply of 10,000 contact mines and to convert seven old Apollo class cruisers into minelayers.5 It is not clear to what extent they were expected to penetrate enemy waters.

Pre-war British naval opinion opposed large-scale minelaying on the theory that it would limit the freedom of action of the fleet. Churchill absorbed the idea that blockade mining was pointless, because the enemy could always sweep up what the British laid. Mining would hinder British offensive operations such as his favoured attack on Borkum. Fisher took Jellicoe’s subtler point that mining the Heligoland Bight was the best way to force the Germans to disclose their intentions by minesweeping.6

The converted minelaying cruiser Latona is shown at Malta during the First World War. Transferred to the Mediterranean in August 1915, she was the only ship of her class to continue minelaying. She joined the converted Channel Islands ferry Gazelle, which laid minefields beginning in April 1915 intended to protect the fleet in the Dardanelles from Turkish submarines. The first were laid in the Gulf of Smyrna. During 1916 HMS Angora was transferred from the North Sea and the smaller merchant ship Perdita converted locally to minelaying duties. The Mediterranean ships laid large fields off the Dardanelles after Gallipoli was evacuated in January 1916, largely to bottle up the German Goeben and Breslau. One of these fields, periodically replanted, caught the German ships when they sortied in January 1918. (Dr David Stevens, SPC-A)

Minelaying was practicable in any depth of water in which a mine could float; the buoyant mine body had to support not only the contents of the mine but also the weight of its mooring chain (which is why mine operators have sometimes traded off mooring strength for more explosive content).

First World War experience showed that minelaying, particularly by submarine, could be extremely dangerous. Navigation in areas controlled by the enemy’s fleet was largely by dead reckoning. However, once a field had been laid, the enemy would inevitably try to sweep it, so the field had to be refreshed. Navigational error could easily bring a minelayer into an unswept part of the previously-laid minefield. This danger made it difficult for the Royal Navy to maintain an effective mine blockade in the Heligoland Bight, even after it acquired fully-effective mines. It also made for considerable casualties among submarine minelayers on both sides (these craft were also vulnerable to explosions among mines still on board).

As it happened, the mine adopted by the Royal Navy was badly flawed, so British minelaying was ineffective until 1917.7 However, early in the war the Royal Navy began a major effort to block the Straits of Dover against both German surface ships and submarines. This Dover Barrage employed a combination of mines and nets, the latter with mines. It was lit at night and patrolled by a variety of craft, the idea being that submarines would be forced to pass through the Straits on the surface at night. One of the unpleasant surprises of the war was that the weather in the Straits often swept away much of the barrage, requiring that it be replaced frequently. The Royal Navy also began work on minesweeping, converting six old torpedo gunboats into sweepers and also developing a reserve trawler sweep force.

Unfortunately the Royal Navy began the war with unreliable inertia mines, the mine exploding when a ship pushed a lever. The British mine development establishment, HMS Vernon, was well aware of the alternative electro-chemical (Hertz Horn) type used by the Germans, but considered it inherently unsafe. If that seems irrational, the reader should be aware that the Russians, the acknowledged leaders in mine technology at the time, who invented the horned contact mine, had recently decided to abandon it in favour of a more complex inertia mine. This French Breguet mine was an adaptation of the Vickers mine widely used by the Royal Navy. The ship activates the mine by pushing on the collar at right. It is in the Museé de la Marine, Paris. (Author’s collection)

German Minelaying

The Germans and the Russians both had effective mines in 1914 and both planned to use them extensively. The Germans completed two Nautilus class cruiser-minelayers in 1905 and 1907, to plans begun in 1904; each could carry 200 mines. Beginning with the Kolberg class (1906 programme), German light cruisers were designed to carry mines, typically 120 of them. After war broke out in 1914 and the machinery being built for the Russian battlecruiser Navarino became available, the fast cruiser-minelayers Brummer and Bremse were designed around it; each could carry 400 mines, twice the load of the earlier pair of cruiser-minelayers and each was fast enough (rated at 28 knots) for offensive sorties into enemy-controlled waters. Beginning with the V 1 class (1911–12 programme), many German destroyers were fitted to lay mines, although in practice only about a quarter of them carried them.8 None of these ships was used at the outset of war because they were considered integral with the High Seas Fleet, which was ordered maintained as a ‘fleet in being’. Only the two slow specially-built minelayers Albatross and Nautilus and ships taken up from trade could be used.

Probably the most effective wartime example of German mining was the blockage of the Dardanelles, using mines like this one in the Turkish naval museum, Istanbul. Mine clearance techniques which worked well in undefended waters failed badly under fire. (Author’s collection)

The most important impact of German destroyer minelaying seems to have been Admiral Jellicoe’s idea that they would probably be employed tactically.9 He repeatedly warned his fleet that if he met the Germans on opposing courses, he would avoid circling around and crossing their wake because he expected the Germans to lay mines as they steamed. This warning seems to have reflected earlier British ideas about how destroyer minelayers would be used in combat.10 It is not clear that the pre-war Royal Navy understood how well the Germans were equipped for mine warfare.11

Although at the outbreak of war the Germans had numerous warships suitable for minelaying, their first operation employed the converted liner Koningen Luise, which was well across the North Sea before the British declared war.12 She was seen by a trawler laying her mines on the night of 4/5 August 1914, she was reported and she was sunk by the cruiser Amphion – which soon hit one of the mines and sank.

The British identified two phases of German minelaying in Home Waters.13 The first began on the outbreak of war and continued spasmodically until the beginning of 1916. The second began early in 1916 and continued to the end of the war, the last six months of 1915 marking a transition. During the first phase surface ships laid large minefields intended mainly to sink warships trying to cut off or chase a raiding squadron. However, on 7 August the Germans announced that they would mine the approaches to British ports. The British protested that mining in the open sea was illegal; eventually the Germans replied that they were laying mines as close to the coast as possible. By the time the reply had been received, about twenty neutral ships had been sunk. German surface ships laid about a thousand mines during 1914, mostly in August and October.14

The Dardanelles fields were laid by the minelayer Nusret. This model is in the Turkish naval museum, Istanbul. (Author’s collection)

To the British, evidence that in this first phase the Germans were more interested in sinking warships than merchant ships was their shift in 1915 to increased mooring depths and also to open-sea mining in the North Sea that spring.15 The British believed that the Germans were soon aware that minefield locations were given away whenever a merchant ship or fishing boat of moderate draught was mined. Mooring mines deeper would minimise such contacts, whereas deep-draught warships, particularly capital ships, would still be mined.

By 1918 the Germans had torpedo-tube mines, so they could use any U-boat as a minelayer. That allowed them to mine the Canadian and US coasts. This one, recovered off Halifax, is in the Canadian military museum in Ottawa. (Author’s collection)

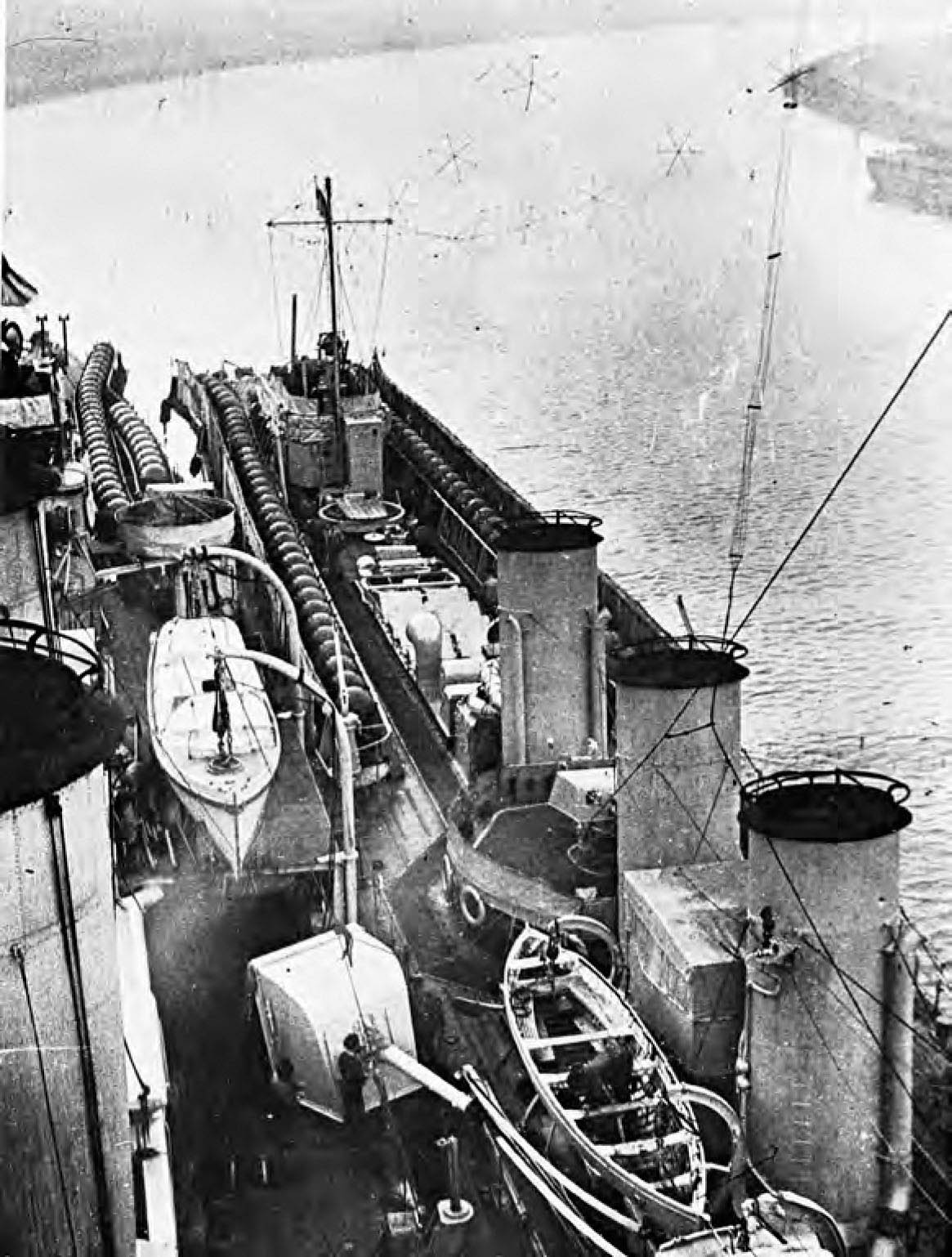

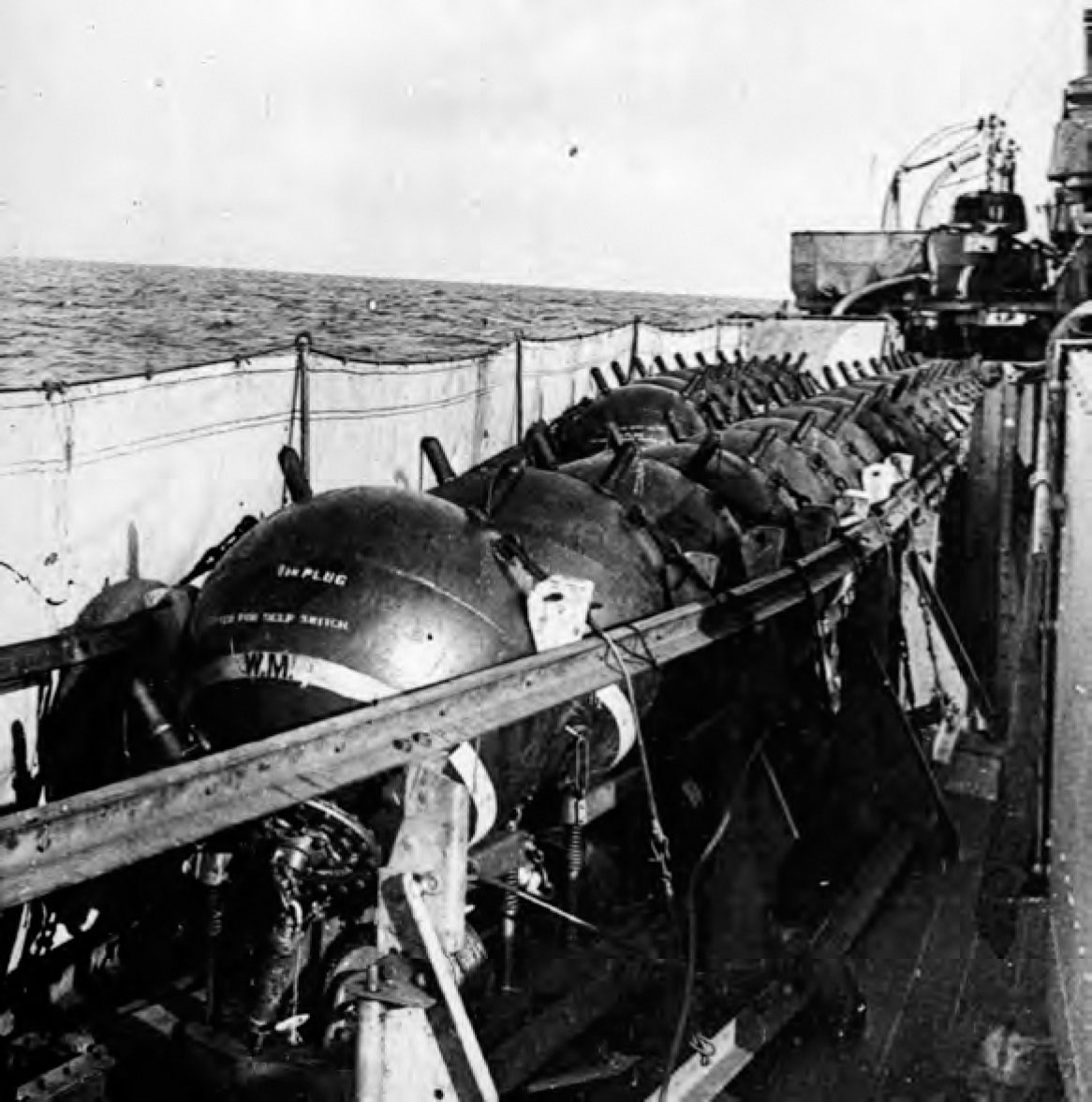

Further fast ships were soon converted into minelayers. Abdiel is shown alongside the light cruiser Aurora, at left. During 1917, eleven light cruisers and twelve destroyers were fitted as convertible minelayers. Note the canvas screens. The horned H type mines shown were fully effective. Once they became available, the Royal Navy began a massive mining campaign, principally against U-boats.

The end of this phase was apparently the Whiten Bank Minefield to the west of the Orkneys laid by the disguised surface raider Moewe between 31 December 1915 and 2 January 1916. The object was to catch the fleet in its exercise area, but the tidal set and water depth were such that mines usually dipped below the draught of the ships. The victims were the battleship King Edward VII and two neutral merchant ships.

The second phase was part of the larger war against shipping, consisting of small minefields laid by submarines. To the British, the fields were placed as part of a systematic attack on the tracks of merchant ships which could be fixed using landmarks ashore, light-vessels and channel buoys.

From a tactical point of view, numerous small fields laid by submarines presented a much worse minesweeping problem than a few large ones, each laid by one or two surface ships. Once the Germans gained the Belgian ports, they made Bruges a mine depot and deployed twelve UC class minelaying submarines, each armed with twelve mines in vertical tubes. They began operations in the summer of 1915. Given a limited radius of operation, they were confined to the approaches to the Thames Estuary, Harwich and Dover. They may have laid a field off the Belgian coast in March, but the first UC-laid mines the British encountered were off the South Foreland on 2 June 1915.16 Initially submarines took care never to lay mines twice in the same area, for fear of being mined themselves; later in the war the Germans assumed the British would soon sweep up their fields and were willing to revisit after ten days.17 The campaign did not become serious until August 1915. The Germans later reported that the UC-boats had laid 648 mines between Dover and Grimsby during 1915. Two of the minelaying boats were lost, one in the Harwich area and one off Lowestoft, of which one was sunk by her own mine. A third ran aground on the Dutch coast and was interned. The following year another was sunk in the Mediterranean by her own mine.18

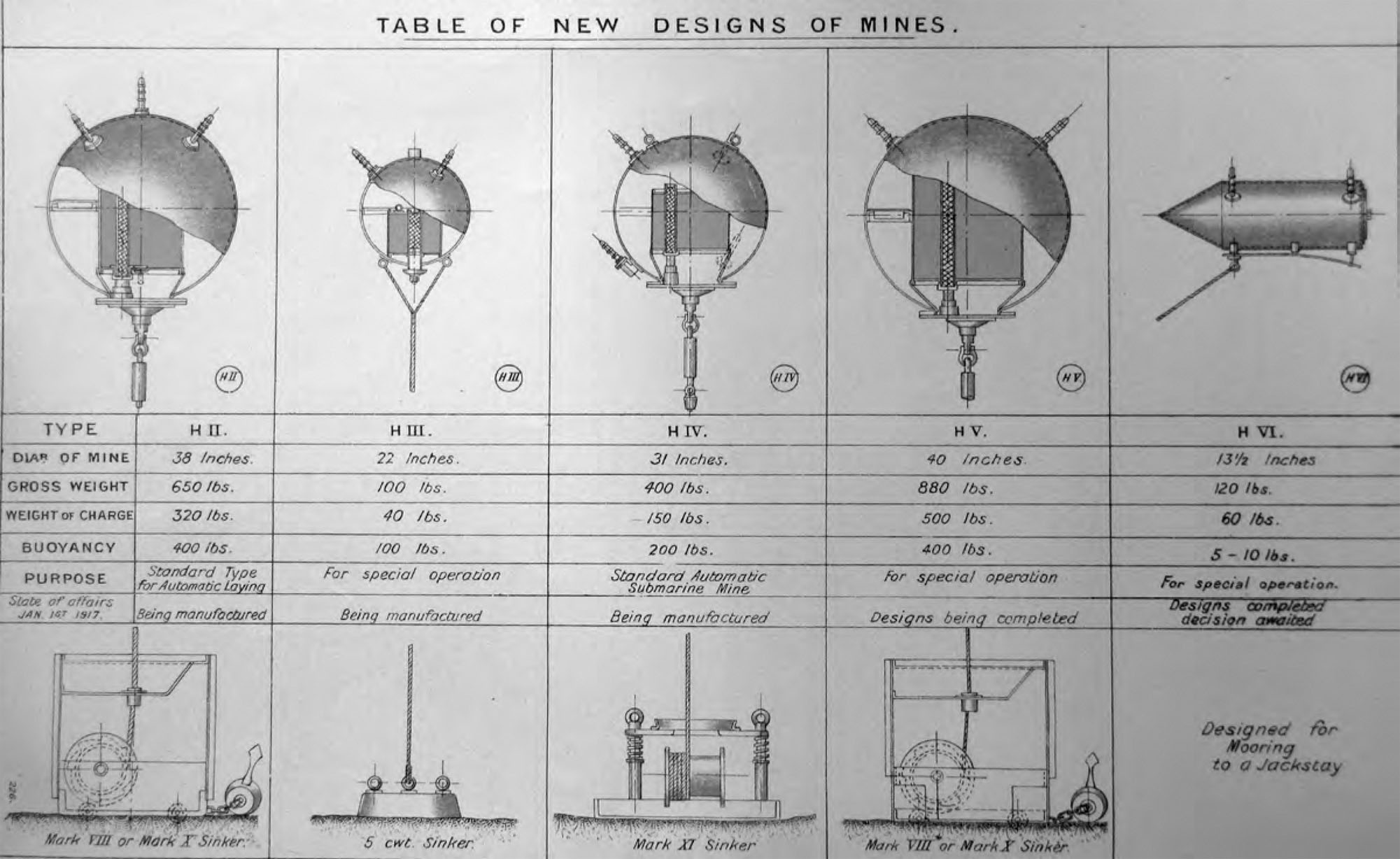

The British horned mines which made the late-war mine offensive effective, from a contemporary diagram. The most important type was H.II. These mines came into production at roughly the same time that the Germans began their campaign of unrestricted U-boat warfare which caused the British to contemplate a much larger mining campaign against the U-boats.

During 1916 the UC boats were supplemented by large ocean-going U-boat minelayers with more sophisticated dry stowage for thirty-four to thirty-six mines. The Germans created two separate minelaying flotillas, one based on Ostend and Zeebrugge (Flanders Flotilla), the other on the Elbe (High Seas Fleet Flotilla). Given their greater radius of action, the High Seas Fleet boats were allocated all waters other than the southern area from Flamborough Head to Land’s End (later extended westward).19 As the number of minelaying U-boats increased, the British were forced to allocate more and more ships to minesweeping, reducing their patrol strength. Through 1916 the Flanders and High Seas Fleet U-boats laid a total of 195 groups of mines, mostly on the East Coast of England.

Although at this time most minefields were designed mainly to sink merchant ships, at the end of May a U-boat was sent specifically to mine the channels used by the Grand Fleet. The British Staff History associates this mining operation with the plans for the German fleet sortie which culminated in the battle of Jutland (on her homeward journey the U-boat passed through the wreckage left by the battle). This field sank HMS Hampshire, which was then carrying Lord Kitchener to Russia. Another U-boat laid a similar field in the Whiten Head Channel; other U-boats of the High Seas Fleet Flotilla mined the Moray Firth and the entrance to the Firth of Forth, another fleet base.20

In 1916 the Germans began to assist the Austrians in mine warfare, transferring some UC-boats to them. They mined both the Italian and French ports, Malta the areas which could support Dardanelles operations (including the Piraeus in Greece, Crete and Mudros), Port Said, Alexandria and also the Russian Black Sea ports.

During 1916 the Germans built minelaying submarines, both the ten large U 71 class and additional UC-boats. They began a new mine offensive in January 1917. Before the spring the number of mines the British destroyed each month was more than double the figure of any previous record. In 1917 the total number of groups of mines laid by U-boats in British waters rose from the 195 of 1916 to 536 and the mines were more widely distributed, with as many on the south and west coasts as off the Nore or Dover. Through the year an average of one submarine-load of mines was laid every 30 hours, many of them being set shallow to sink minesweepers. In the last fortnight of April 1917 the Royal Navy was losing on average one sweeper each day. The situation was complicated by numerous mines which broke from their moorings and drifted. They included mines the Germans laid in defensive fields off the Scheldt and in the Heligoland Bight.21

H-type mines on board the light cruiser Aurora, which had a capacity of seventy-four.

Submarine minelayers typically laid mines on the observed track of merchant ships and then laid off to seaward, waiting for traffic to be diverted so that it could be attacked by torpedo (all the large U-minelayers and later UC-boats had torpedo tubes, whereas the original UCs lacked them).22 British policy was to minimise the mined area so that traffic could be moved shorewards, placing mines between ships and U-boats. U-boats also laid fields in the Mediterranean during 1917, including 108 mines off Malta and many in French areas of responsibility.

The only German surface minelayer active outside home waters in 1917 was the disguised raider Wolf, which broke out of the North Sea in the latter part of 1916 carrying 458 mines. She began with a 25-mine field off the Cape on 16 January 1917 and another on 18 January. She also transferred twenty-five mines to one of her prizes, the steamer Turritella, which laid them off Aden, at the mouth of the Red Sea. Wolf laid further fields off Colombo (Cape Cormorin), Bombay, Australia (Cook and Bass Straits), Three King’s Island in New Zealand and then a large field (110 mines) near the Andaman Islands in the South China Sea.23

The British found that in 1918 the German minelaying effort declined noticeably, as anti-submarine operations were destroying many of the minelayers. They had to operate in coastal waters where they were particularly exposed to air reconnaissance and to hunting flotillas and the new controlled minefields also made it difficult for the submarines to operate off headlands where there was a concentrated traffic flow. Except for the area around Harwich (where the Flanders flotilla operated), the Germans seemed to be sparing mines for more definite objectives, such as certain important convoys (particularly to neutrals) and to the transit of American troops. The British speculated that the loss of trained U-boat personnel was probably a worse problem than the loss of submarines.

The old Apollo class cruisers proved inadequate, so early in 1915 six merchant ships were taken up from trade for conversion, including the two big (5934 GRT) fast (23-knot) new Canadian ferries Princess Irene and Princess Margaret. Each could carry 500 mines. Armament was two 4.7in, two 12pdr and two 6pdr high-angle guns. The merchant ships relieved the old cruisers in March 1915 and laid the first minefield in the Heligoland Bight. The new ships laid the initial field in May 1915. On 27 May Princess Irene blew up, probably due to a mine pistol going off as mines were prepared for laying. As she and Princess Margaret were considered by far the best of the conversions, this was a serious blow. The other initial merchant ship conversions were Paris, Orvieto (replaced in 1916 by the smaller Wahine), Biarritz and Angora, of which only Biarritz (23 knots) and Paris (25 knots) were comparably fast, but neither had even a third of the capacity of the two Canadian ships.

During 1918 the Flanders Flotilla concentrated mainly on particular British ports. The High Seas Flotilla had three objectives: attacks on the Dutch coast to disrupt Dutch convoys; an attack on the inner waters of the Firth of Forth, which were used by the Grand Fleet; and the creation of a huge circular barrage (43-mile radius) centred on the Bell Rock, intended specifically against the exit used by the Grand Fleet. Despite German attempts to maintain security, the British deduced the purpose and scope of the big barrage shortly after it had been completed and they proceeded to sweep it up. The big barrage seems to have been associated with German plans for a final battle against the Grand Fleet. In October 1918 the Germans assembled every non-minelaying U-boat they had available and placed them in a large square to seaward of the barrage. Their plan was for the High Seas Fleet to sortie to attract the Grand Fleet into battle. The Grand Fleet would have steamed through the combination mine and submarine trap. For their part, the Germans were never aware that their barrage had been completely swept.24

The Germans introduced ocean-going U-boat minelayers which brought the mine war to the other side of the Atlantic. The mined the Canadian, Portuguese, US and Sierra Leone coasts, the Portuguese coast particularly heavily (as it was accessible to the earlier type of minelaying submarine). The first mine was found off Sierra Leone on 10 April 1918, the U-boat first having shelled the Liberian coast. The first mine damage on the US coast was to a tanker near the Overfalls Light Vessel, on 3 June 1918. The most spectacular victim was the cruiser San Diego. The first mines were laid off Halifax, in the approach to the swept channel, on 16 October 1918. Among other things, the overseas mine campaign forced the Royal Navy to begin building a much more global mine countermeasures force.25

The battleship HMS London was also converted into a minelayer, at Rosyth (completed 18 May 1918). She was armed with three 6in, one 4in high-angle gun and 240 mines. (Abrahams via Dr David Stevens, SPC-A)

From 1915 on the Germans laid defensive minefields off the Belgian coast, which had to be cleared by sweepers operating at night so that bombardment ships could move in. This was not too different from the experience at Gallipoli. As part of their campaign to protect their Belgian coastal bases at Zeebrugge and Ostend, the Germans tried to make the French ports of Calais and Cherbourg unusable by mining them (Dunkirk was first mined on 20 August 1915, followed by Boulogne and then by Calais on 2 September).

British Minelaying26

The first major British wartime minelaying effort was intended to protect the passage of troop transports to France in mid-September 1914. At first the transports were covered by patrols, on which duty the three armoured cruisers Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy were sunk by U 9. Mines then became a preferable alternative and on successive nights four of the minelaying cruisers laid 1064 mines. Much of this field had to be swept to allow access to the port of Zeebrugge, then relaid once the Germans captured that port. By the end of 1914 the Royal Navy had laid 3064 mines off Zeebrugge and in the Strait of Dover and the initial Dover barrage had sunk two U-boats (U 5 and U 11).

In January 1915 the British laid their first field (440 mines) in the Heligoland Bight to block known German routes and thus to complicate German fleet operations. By the end of the year, 4538 mines had been laid in the Heligoland Bight. At the same time they kept refreshing the Dover Barrage: 4390 mines in February, protected in part by sweep obstructors called Destructors, plus another 1471 in July. At the same time deep anti-U-boat fields were laid around the British coast (1328 mines). The converted ferry Gazelle laid forty to fifty French Breguet mines off Turkish ports in support of the Dardanelles operation. In the following year the German Flanders Flotilla of small U-boats became a major problem; Flag Officer Flanders proposed a large minefield (the Belgian ‘Zareba’) to contain them. It included 5077 mines, some of them deep to destroy submerged U-boats. The barrage also included nets.

Once the British had an effective horned contact mine in 1917, they needed large numbers of minelayers, but the mounting U-boat campaign made it impractical to convert more large merchant ships. The Royal Navy therefore turned to obsolete warships such as HMS Amphitrite, shown here. The large cruiser Ariadne was also converted. At the end of the war HMS Euryalus was under conversion at Hong Kong. As a minelayer, Amphitrite was armed with four 6in guns, one 4in high-angle gun and 354 mines. She was completed at Portsmouth, 9 August 1917.

The Royal Navy became more interested in offensive minelaying, for which it needed minelayers which could penetrate enemy-controlled waters: in 1916 it commissioned its first destroyer minelayer (Abdiel) and its first submarine minelayers. In May 1916 Abdiel laid a unique tactical field off the Horns Reef intended to support a Grand Fleet operation, but the battle of Jutland intervened. This field damaged the German battleship Ostfriesland as she returned from the 1916 battle. During 1916 the British laid 13,280 mines in northwest European waters and additional mines in the Mediterranean.

British minelaying activity accelerated considerably during 1917, as a reliable mine (the horned H2) finally became available. Many ships were converted to lay mines, including both fast cruisers and destroyers, the old cruisers Ariadne and Amphitrite and CMBs. The Dover barrage was reinforced and measures were taken to replace mines and nets of the Belgian Zareba removed by the Germans. Coastal fields were laid around the British Isles (8609 mines on the south and east coasts) to trap U-boats in their operational areas. First Sea Lord Admiral Jellicoe proposed a U-boat barrier field in the Heligoland Bight, but the 60,000 mines required were not available. However, the bulk of mines laid in 1917 were in the Bight (15,686 mines). Another 2573 mines were laid in the Mediterranean, plus 334 as part of a project to close the Straits of Otranto, the access between the Mediterranean and Austro-Hungarian naval bases on the Adriatic.

A mine is released by a motor launch, operating as an inshore minelayer. There were also minelaying trawlers.

The most spectacular and also perhaps the most controversial, minelaying operation of the war was the huge Northern Barrage, which was mainly a US Navy operation. The US Navy converted a fleet of merchant ships, including train ferries, to lay the barrage. Here the fleet is in minelaying formation, with eight ships in line abreast and two in advance waiting their turn. The British Minelaying Squadron is in the left distance. Six destroyers are visible near the horizon. The US Minelaying Squadron would steam in this formation, planting five or six lines of mines at one time, for a distance of 46 to 55 miles at 12 knots. Ships were 500 yds apart. On board the minelayers, steam winches hauled trains or fleets of twenty to forty mines each, aft to the feeding section, where they were seized by gangs of four men each and pushed into the traps at the stern from which they were released. Marker buoys were laid at the end of each field so that the squadron could later resume laying. (US Army Signal Corps via US Navy Historical and Heritage Command).

By this time mines were considered a primary anti-submarine weapon and their use accelerated again in 1918. An average of 6200 mines was laid each month up to October 1918. Overall, the British claimed that their mines laid in northwestern European waters definitely sank forty-three U-boats (and probably sank four more); mines also accounted for another two U-boats (one in a field across the Straits of Otranto laid by France and Italy) and three more probables.

The Royal Navy was unique during the First World War in developing non-contact (influence) mines, beginning with February 1916 trials of mines fitted with magnetophones (microphones), inspired by earlier work on submarine detection by hydrophone. At this stage the magnetophone was to have been the detector for a group of controlled mines. Magnetophone-controlled minefields were laid at Cromarty and at Scapa Flow for defence against submarines and that at Scapa (Hoxa) attacked a submarine on 12 April 1917. An alternative low-frequency acoustic sensor was tested some time before the summer of 1918 and the A attachment (acoustic sensor) for mines was ready for service at the end of the war.

A magnetic mine actually entered service. Development began in July 1917 and a concrete (i.e., non-magnetic) case was used. In September 1917 orders for 10,000 magnetic mines were placed; the mine became available in July 1918 as the ‘M Sinker’. Although unreliable (in one trial, 60 per cent exploded shortly after having been laid), the M mine was laid off the Belgian coast and it seems to have accounted for several U-boats whose loss was otherwise unexplained.

In 1918 there was also a controlled L (loop) mine using a magnetic loop as a sensor for a field of controlled mines; the loop indicated that a U-boat or ship had passed overhead. The first test field was laid in December 1917 and at the Armistice a special field, controlled by towers sunk into the seabed, was being laid in the Dover Strait. By the end of the war about 100 Royal Navy ships and craft could lay mines and others were being converted.27

The Northern Barrage28

When it entered the war, the United States brought with it huge industrial resources which made it possible to propose large projects. One of the more spectacular was the Northern Barrage, a belt of mines extending from northern Scotland to Norway, to close off the Atlantic to U-boats. On 15 April 1917 (i.e., less than two weeks after the United States entered the war) the US Navy Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) mine section submitted a memorandum proposing mine barrages to close off the North Sea and the Adriatic to U-boats. It suggested that even partially-effective barrages would be decisive. These barrages were alternatives to the existing British policy of close-in mining, which had not yet been successful (the British did not yet have a reliable mine; it would enter service later in 1917). This was an enormous project; the 250 mile North Sea barrier would require an unprecedented number of mines and it would cost $200 to $400 million, an enormous sum at the time. In May 1917 the US Navy Office of Operations (OpNav) proposed the idea to the British. It assumed that the barrier would resemble that off Dover: nets and moored and floating mines, effective at depths of 35 to 200ft, hence safe for surface ships. Patrols would deal with submarines trying to cross the barrage on the surface. Given problems maintaining the short Dover Barrage, the idea must have seemed ludicrous.29 Moreover, minefields had to be patrolled to be effective and the barrage would absorb far too many patrol vessels.

The key to the Northern Barrage was the US Mk VI antenna mine. Extending well above and below the mine, the antennas would (at least in theory) allow the mine to destroy any U-boat passing at any safe depth. This Mk VI, photographed at Inverness, shows its characteristic wire antenna in stowed position on its left side.

BuOrd persisted. It conceived a new type of mine mechanism (the K-pistol) by means of which a mine could destroy a U-boat floating well above or below it. A K-mine had an antenna which floated above it (another could be suspended below). It was fired by electromagnetic action between antenna and the steel hull of a submarine which touched it (similar methods were used in trailing wire devices intended to detect bottomed U-boats). The concept was discovered in April 1917 and brought to the point at which it was worth producing in July.30 Initially it was offered not only as a mine but also as an ASW sweep. A mine with a 300lb charge could destroy a U-boat 100ft away, so nominal antenna length was set at 100ft. An incidental advantage was that the mine could be planted deep enough to be immune to wave action.

US Atlantic Fleet commander Admiral T H Mayo pressed the project on First Sea Lord Admiral Jellicoe during his visit to England. Jellicoe in turn raised the idea at the Allied naval conference held in London on 4–5 September 1917.31 He offered it as a preferable alternative to a closer-in barrage, one advantage being that it was so far from Germany that the Germans could not possibly sweep it. When he returned to the United States, Mayo sold the idea to OpNav. CNO Admiral Benson directed BuOrd to procure 100,000 mines. By this time the K-pistol and the mine case had been designed, but normally a new mine would have taken a year from concept to prototype, let alone to mass production. To simplify the project, BuOrd adopted a modular approach, in which components were designed so that changes in one would have minimal impact on others (in fact very few changes were needed). The anchor was based on the current British design. The first contract for K-1 pistols was let as early as 9 August 1917, with a follow-up for 90,000 more on 3 October – about a month before the barrage project was officially adopted.

The initial BuOrd proposal called for 72,000 mines to fill a 300-mile barrier, plus mines for US coast defence (say 25,000), hence for a total of 100,000 mines. This estimate was intentionally high, but it was retained. A later BuOrd proposal added 28,000 replacements and reserves to the 72,000 barrier mines. Once the Northern Barrage project had been accepted, Adriatic and Dardanelles (Aegean) barrages (15,000 mines to cover 30 miles) were projected. In July 1917 the estimated cost of 125,000 mines for all these projects was $140 million, considerably under the original estimate using more conventional mines.

To sell the project, BuOrd had to show that the huge barrage could be laid in a reasonable length of time. In July 1917 it estimated that the British had eighteen minelayers and that the United States could furnish another four, for a total of twenty-two, each laying 200 mines per day. With one day for reloading, this force could lay 2200 mines per day. Alternatively, forty destroyers could each lay 50 per day, for a combined total of 4200 mines per day. In the end the British furnished the mine bases but the US Navy converted the eight ships which, with the cruiser minelayers Baltimore and San Francisco, laid the mines. Minelaying began in June 1918 (the British had begun laying their own mines in March). Critical to the project was the enthusiastic support of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D Roosevelt, in charge of naval procurement (and described in contemporary US Navy correspondence as the ‘go-to’ man for urgent programmes).32

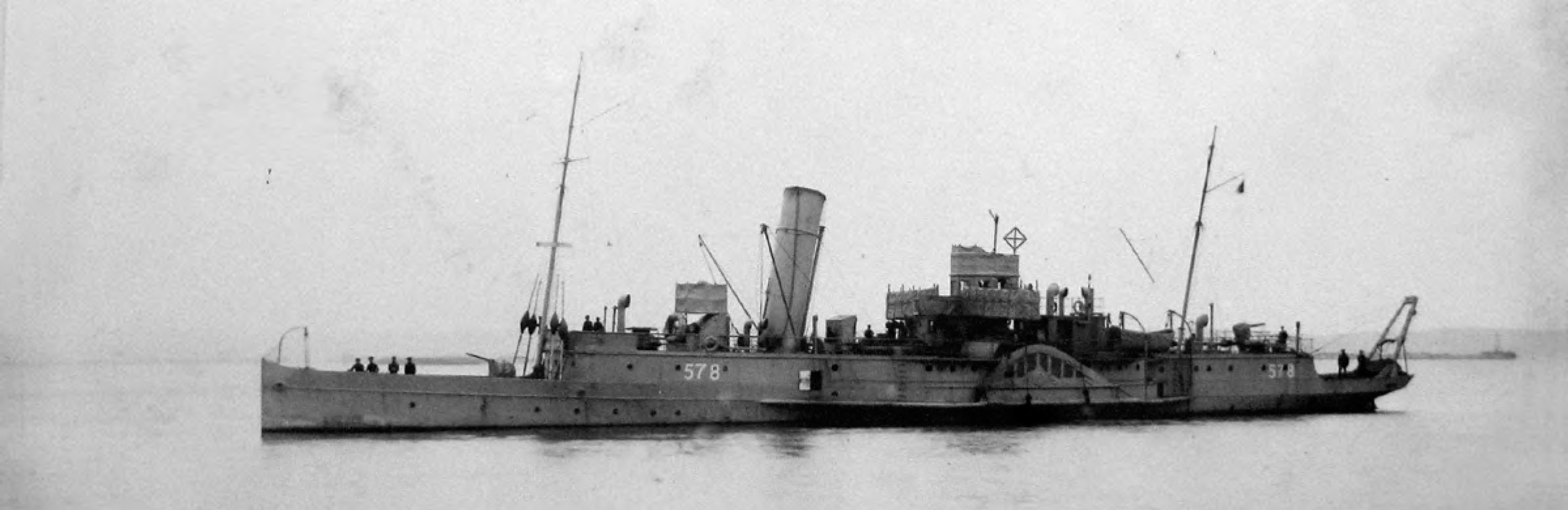

The first British fleet sweepers were converted torpedo gunboats like HMS Circe, shown. Visible mine countermeasures features are the gallows on her bow for a protection device and the A-frame on her stern to handle one side of a two-ship sweep. The torpedo gunboats were backed by trawlers, which conducted most early Royal Navy sweeping. The ‘Flower’ class sloops were intended partly to replace the torpedo gunboats.

To produce so many mines, BuOrd became the first navy agency to take advantage of the huge capacity of the US auto industry. Plans initially called for producing 1000 mines per day, but that was easily exceeded. The first mines became available in March 1918, by which time production was already well underway. Meanwhile the US automobile industry became available for war production, BuOrd apparently being the first navy agency to take advantage of its huge capacity. BuOrd chose to have the elements of the mines produced separately and to assemble mines only just before they were to be laid, at British bases supporting the barrage. The bureau hoped that in this way it could maintain the secrecy of the K-pistol.

Initially the barrage was a way of keeping U-boats out of the sea lanes from the United States to England. When the Royal Navy presented a review of the ASW war to the War Cabinet in January 1918, it added the argument that U-boat hunting was nearly impossible outside once a U-boat reached the broad waters of the Atlantic. Convoy might same merchant ships in the Atlantic, but it was essential to cut down the U-boat force.

The Royal Navy took up many civilian paddle steamers as minesweepers. This is HMS Mercury, built in 1892. She was armed with two 6pdrs. this photograph was taken in Weymouth in 1917.

British experience to date showed that to be effective a minefield had to consist of three lines of mines. Mines did not have to be effective below 200ft, because U-boats would not willingly dive below that. The total barrier length of 280 miles, most in water less than 300ft deep, was divided into three areas. The central (notified) area A would block both surface ships and submarines. It was deliberately limited because it affected the Grand Fleet and also neutral shipping. Area A was 56 miles wide, mines being laid 40 yds apart, with mines at two depths (total six lines of mines). That required 56,500 mines.

The flanking areas B (to the Scottish coast) and C (to Norwegian waters) employed deep mines covered by air and surface patrols, to force submarines to dive. Area B was a British responsibility. Because the mines used contact pistols, they had to be laid at multiple depths: 63ft, 96ft, 128ft, 133ft and 156ft, a total of 67,500 mines. Area C employed American mines (two depths), over a length of 60 miles (18,000 mines). The number of British mines could be substantially reduced by using the acoustic mechanism (X mechanism, early in 1918) then under development, but it was not ready in time.

By the Armistice, 56,611 US mines (and 13,652 British mines) had been laid in the Northern Barrage. Area A, originally the US portion, was complete except for 6400 mines (10 days’ laying). The US Navy also laid some mines in Areas B and C, originally allocated to the Royal Navy (the British had been unable to mine down to 200ft depth, as planned). The massive projected barrier patrol force was never assembled.

After two U-boats were damaged trying to pass through Area C in July 1918, the Germans re-routed U-boats through Area B (not yet proclaimed as mined) and through Norwegian waters; eventually the Norwegians were convinced to mine their waters against such incursions. Surprise mining in Area B in September 1918 damaged two U-boats and sank another. It appeared that at least six U-boats had been sunk by the barrage and another six severely damaged. It is not clear to what extent the existence of the Barrier convinced U-boat commanders not to pass through the mined area (Admiral Sims claimed after the war that there was evidence that some had hesitated before entering).

The Germans never understood how the mine worked. After the war, US officers in Berlin met former U-boat officers, who thought that the barrage consisted of small mines because their submarines had triggered mines well below or above them.

Russian Minelaying

In 1914 the Russians were probably the greatest proponents of mine warfare. Much of their fleet had been destroyed in the Russo-Japanese War and the replacements were not yet in service in great numbers. Even then the Russian Baltic fleet could hardly match the German High Seas Fleet. In November 1906, therefore, the Russians began to plan large mine barrages to deny the Germans access to the Gulf of Bothnia and to their capital, St Petersburg.33 By 1914 the Russians had already laid down the world’s first submarine minelayer (Krab), which would be completed in 1915, after the first German minelaying U-boats. The Baltic Fleet strategy approved by the Tsar in 1912 envisaged offensive minelaying off the German coast plus a defence, involving heavy minefields, of the Central Position defending the capital. In 1914 the Russians had 7000 mines in the Baltic, 4500 in the Black Sea and 4000 at Vladivostok (1000 of which were later given to the Royal Navy). The first field of 2129 mines was laid in a single day in July 1914 to protect the Central Position; later minesweepers and torpedo boats added 871 and 290 mines, respectively, to guard the flanks of the main minefield. After a German feint attack on Windau, destroyers laid 100 mines to protect that port. Later in 1914 the Russians began to lay mines off German ports to immobilise the German fleet in the Baltic, beginning with 295 mines laid in three barriers off Memel.

The Baltic Fleet laid 3648 mines in offensive barriers and 34,943 mines in defensive barriers, the latter beginning with the 2995 mines laid to protect the Central Position in 1914 (plus another 2165 in 1916 and another 4342 between May and September 1917). The Black Sea Fleet laid a total of 6385 mines in defensive fields (1750 mines off Sevastopol, 3513 off Odessa, 550 in the Kerch Straits and 572 off Batumi/Poti). Offensive mining amounted to 5238 mines in the Bosporus, 440 off Anatolia (to disrupt Turkish sea traffic supporting army operations) and 1370 off Varna/Constanta.

The Ascot class paddle sweeper Eridge on her trials. The two cranes abeam her after funnel were intended to handle seaplanes, which it was hoped would intercept Zeppelins spotted while the ships were sweeping mines. They were never embarked.

In the Baltic, mines sank the armoured cruiser Friedrich Carl on 17 November 1914 and the light cruiser Bremen on 17 December 1915. The light cruiser Augsburg was mined (but not sunk) on a Russian barrier on 24/25 January 1915 and the old cruiser Gazelle was so badly damaged that she was towed home but not repaired. During the German attack on the Åland islands in 1917 (12 October 1917), the battleship Bayern was seriously damaged but not sunk by a mine. Seven of eleven German destroyers were mined and sunk during a night raid in the Baltic on 10 November 1916 (S 57, S 58, S 59, V 72, V 75, V 76 and G 90). Other modern German destroyers mined in the Baltic were S 31 (19 August 1915), V 99 (17 August 1915), V 162 (13 August 1916) and S 64 (18 October 1917). In addition, during the British intervention in Russia, the cruiser Cassandra (5 December 1918) and the destroyer Verulam (4 September 1919) were mined. There were also lesser craft. In addition, mines seem to have claimed three U-boats (U 26 about 31 August 1915, U 10 about 26 May 1916 and UC 57 about 18 November 1917). In the Black Sea, the Turkish cruiser Medjidieh was sunk off Odessa (3 April 1915). Mines also sank the gunboat Berk (2 January 1915); the smaller gunboats Duruk Reis, Hizir Reis and Issa Reis (all in 1915); and the submarines UB 45, UC 15 and UB 46 (1916), plus lesser craft.

British Minesweeping

Minesweeping required massive numbers of vessels, because all forms of sweeping were slow and cleared a narrow path. For the Royal Navy, the industrial effort involved produced ships some of which (sloops) turned out to be well-adapted to the anti-submarine campaign of 1917–18, including convoy work. Had these ships not been conceived for minesweeping, the numbers required for convoy would have been considerably more difficult to assemble.

The official British post-war minesweeping history dates the beginning of systematic Royal Navy sweeping experiments to 1907, as the lessons of the Russo-Japanese War were being assimilated.34 Annual Vernon reports show earlier sweeping experiments, but they were generally intended to recover exercise mines. In 1907 a high-speed explosive sweep (also applied to anti-submarine work, as is explained separately) was invented. It employed a sliding charge which could be fired electrically from a ship when it contacted a mine. It worked, but it required skilled operators and even then it was not reliable. The need for skilled operators insured that it could not be deployed in sufficient numbers in wartime.

In the summer of 1907 the new C-in-C Home Fleet Admiral Lord Beresford warned that in wartime mines might well immobilise his fleet. He doubted that small warships would be available for sweeping, so he proposed experiments with Grimsby trawlers, using their sweep gear. He hired two of them (Andes and Algoma) for experiments at Portland, using their regular fishing crews. The ordinary fishing trawl was unsuccessful, but a wire could be towed between the two, its depth controlled by a wooden water kite. It could entangle or cut the mooring wire of a mine, but unlike the explosive sweep it could not destroy the mine directly. In wartime sweeps which dragged mines were sometimes a problem and sometimes special mine dumping areas had to be designated.35

This sweep (initially the ‘fixed wire sweep’) was adopted as the ‘A’ Sweep, which became the wartime British standard.36 The sweep could be extended over a width of two cables (200 yds) and towed at 5 to 6 knots. Its depth was maintained by a pair of ‘water kites’, one towed by each sweeper. There were initially two types, one with 2in or 2½in wire and 12ft kites and one with 1in wire and 6ft kites. Later experience showed that this tow speed could not be exceeded in practice, although the sweep itself would survive at much higher speed. It also turned out that the sweep could not be relied upon to indicate the presence of a mine, which in theory might have been indicated by the strain on the wire. A dynamometer (strain indicator) was added before the war, but in practice it showed fluctuating strains when ships manoeuvred, or when they encountered heavy weather (which did not prevent sweeping). In 1916 the AMS asked Messrs. Bullivant, who made torpedo nets, to try a serrated wire which could improve the sweep’s ability to cut mine moorings. It proved very successful; the Staff History of British sweeping accounted it one of the greatest technical improvements in sweeping. British sweepers used gallows rather than davits to handle their gear, because they kept the kite under better control when it was lifted out of the water.

The ‘Hunts’ were more conventional minesweepers intended to replace the paddlers and also to function as fleet sweepers. HMS Cattistock is shown running trials in May 1917, her gun not yet having been mounted.

The smallest of the purpose-built wartime sweepers were the shallow-draught tunnel sweepers built as Mesopotamian river tugs for the War Office, then taken over by the navy. Launched in September 1917, Quadrille was turned over to the Royal Navy (and named) that December.

The Royal Navy liked the ‘A’ Sweep for clearing minefields, but it demanded accurate station-keeping and in rough weather it often parted. Nor was it recommended for marked War Channels which were infested with wrecks. The Royal Navy also used a single-ship paravane sweep for what it called searching sweeps, to define a minefield. It did not require accurate station-keeping and because it was independent the sweeper could zig-zag at will to evade submarine attack (a pair ‘A’ Sweeping had to be guarded by two others).

In contrast to the ‘A’ Sweep, the French and Russian navies used a single-ship sweep, a ship trailing sweep wires on each side. Mechanical cutters were attached to the wires. The British designated the French sweep the ‘B’ Sweep and by 1917 their sweeping handbook described it as obsolete. However, when the US Navy entered the war it found the French sweep more attractive and adopted it (however, the post-war clearance of the Northern Barrage was done with ‘A’ Sweeps).37 The Royal Navy later discarded the ‘A’ Sweep in favour of a single-ship sweep.

To provide the fleet with a mobile sweeping force, six old torpedo gunboats were converted into minesweepers (to parallel the seven old cruisers converted into minelayers). The first entered service in 1908. Conversion entailed fitting double drum steam trawler winches (typically forward of the engine room casing on the upper deck, slightly to port) and gallows for the water kite. All torpedo tubes and supporting equipment were removed. The ex-gunboats were manned on a nucleus basis and were intended to develop sweep methods and to train the reservists for the trawlers. They were worked as a flotilla in conjunction with the fleet or with a single capital ship representing the fleet. Fleet sweepers were also exercised with minelayers, partly to arouse a healthy rivalry. The four torpedo gunboats assigned to fishery protection were also fitted for sweeping and were occasionally released from fishery protection duties for that purpose. Two other torpedo gunboats were retained at the technical schools at this time. The gunboats became a permanent part of the Home Fleet in the summer of 1912, conducting fleet exercises.38

Exercises by the Gunboat Flotilla showed the great advantage of high sweep speed, that sweeping was possible even in moderately bad weather, the absolute need to keep accurate station and the need for accuracy in the amount of sweep and kite wire veered.39 It also turned out that anti-sweep devices did not work. However, pre-war exercises failed to show the need for absolutely accurate navigation and for accurate estimates of tidal effect.40 Experiments with ‘River’ class destroyers showed that they would be adequate replacements for the gunboats; approval to fit sweep gear (1912) was revoked because it appeared that they would be needed for patrol work.

At the same time a trawler (sweeping) reserve was formed; during a pre-war period of strained relations, 100 were to be mobilised.41 The policy laid down before the war was to maintain a force of fairly fast fleet sweepers for open water (in sheltered waters fleet picket boats might be used), trawlers to defend home ports and local authorities at commercial ports to be encouraged to keep their entrances free by using suitable local vessels.42 Conferences to arrange these last arrangements proved unsuccessful. The sweeps devised to deal with mines were clearly closely related to sweeps devised to destroy submarines (described in Chapter 13). It is not altogether clear which came first.

Despite successful mobilisation of trawlers, in 1914 the Royal Navy had nothing like the minesweeping force it would soon need. The Staff History prepared in 1920 blamed that on two detrimental factors: a belief that somehow the Great Powers would come to an understanding limiting mine warfare and a belief that the appropriate counter to a minelaying campaign was patrols to find and destroy minelayers (the initial mining operation by the German Koningen Luise showed that this was wrong). It was also difficult to arrange peacetime co-operation with commercial and dominion authorities. The replacement of the gunboats was postponed and the claims of the patrol flotillas and the trawlers took precedence. Even so, it was clear that the Admiralty understood the importance of minesweeping. It established a Minesweeping Section in 1911 under an Inspecting Captain of Minesweeping Vessels, much as the submarine service had its own Inspecting Captain. In 1912 the Inspecting Captain came under the authority of the Admiral of Patrols. In 1914 he had the six gunboats and eighty-six trawlers, most of them assigned to specific ports. Six, which were available for reallocation by C-in-C Home Fleet, were transferred almost immediately to Scapa Flow.43

Shortly after the sinking of HMS Amphion, news from a source regarded as reliable reached the fleet that the minefield involved had been part of a much larger operation and about 29 August another fifty trawlers (in addition to the 200 already taken up) were mobilised as part of a ‘special reserve’. However, no enemy mines had yet been recovered and the efficiency of the ‘A’ Sweep had not yet been demonstrated. Trawler crews were largely raw. It was clear that the ‘A’ Sweep would be slow, so a naval officer suggested instead drifter nets of the type used for fishing. A trial showed that the nets were both unreliable and dangerous.44 Due to their low speed, drifters tended to drag mines rather than to cut their mooring wires so that they could be sunk by gunfire.

Fortunately after a sortie by the minelayer Albatross late in August the Germans did not lay further minefields until the end of October, providing the nascent minesweeping force time to train.45 By 1 September, six sweepers had been lost and only thirty mines destroyed; confidence in the ‘A’ Sweep was nearly gone. Each trawler sunk carried with it half its crew. The situation was so bad that sweeping had been temporarily suspended in favour of aerial reconnaissance of suspected minefields.46

The crisis in September 1914 led to appointment of an operational commander for East Coast Minesweeping, Admiral Mine Sweeping (AMS), who also became responsible for developing and fitting mine countermeasures. He was not, however, responsible for building minesweepers. As part of the reorganisation of the Admiralty in 1917, the new post of Director of Torpedoes and Mines (DTM) was created (previously this would have been part of the organisation headed by the Director of Naval Ordnance). He now took over responsibility for mine protection and sweep gear and also for the production of sweepers. Operations and training were delegated to a Captain of Mine Sweeping (CMS) who headed a section under the Director of the Anti-Submarine Division (DASD) of the Naval Staff; later CMS became Superintendent of Minesweeping (SMS). Under a further reorganisation (October 1917) the minesweeping section became a division of the Naval Staff under a Director responsible for all sweeping in Home Waters. The rise in stature of the minesweeping function gives some idea of the increasing scope of the mine problem.

In addition to sweeps of various types (mainly the ‘A’ Sweep), the Royal Navy tried to spot mines from the air as early as the autumn of 1914. That turned out to be difficult in the North Sea, but it was quite successful in the Mediterranean. For example, late 1917 aircraft flying over the Gulf of Ruphani spotted suspected mines and dropped buoys so that motor launches could be directed to them. During 1918 kite (towed) balloons were used for mine spotting.47

By December 1914, the British minesweeping force was becoming far more competent. After the Germans laid a minefield during the Scarborough raid, a mixed force of fleet sweepers and trawlers managed to define the extent of the field (for the first time) and then clear it. The first German mine was recovered during this operation. During 1914, the Germans laid 840 mines in British waters, accounting for over fifty merchant ships and fishing boats, roughly one for every seventeen mines. Three hundred had been neutralised. Initially many in the Royal Navy saw merchant ships as, in effect, mine sentries: mining one indicated the location of a new minefield. However, losses of merchant ships were becoming less and less acceptable.

Initially the Germans laid large minefields and the British established a swept War Channel. Once the Germans began laying very small fields using submarines, it became vital to inform ships at sea when minefields were discovered. The Admiralty Signal Division began a systematic series of such messages in January 1916, using the designating letter Q. They were sent by wire to bases and by W/T from Cleethorpes, all ships being instructed to look out for such messages every two hours. The ‘Q’ designation later came to indicate a cleared route (a ‘Q route’) and that designation became standard in Allied mine countermeasures in later years (‘Q’ routes were, for example, to be maintained in the 1980s in US harbour areas).

Losses peaked in 1917, the German submarine mining campaign paralleling the unrestricted submarine attack campaign. Overall, the German campaign extended submarine mining well beyond the original East Coast area, so that by the summer of 1917 every part of the coasts of Great Britain and Ireland was being mined. Quite apart from making up for losses, that greater extent demanded many more sweepers. In some cases the same large trawlers could be used either to attack submarines or to sweep any mines they laid. Thus the Admiralty was forced to choose between assigning much the same ships to either sweeping or to anti-submarine work. The author of the British Staff History of minesweeping argued that the Germans expanded submarine mining specifically to force the withdrawal of anti-submarine craft and thus to help their submarine torpedo campaign. For their part the British laid out the swept war channel specifically to limit both torpedo and mine attacks by placing it in the shallowest possible water.48

Up to early 1917 standard British practice was to close a port whenever mines were reported, keeping it closed until it seemed certain that the entrance had been thoroughly cleared. That left merchant ships bound for the port had to stand off, making them easy targets for U-boats offshore. The British learned to reopen ports as soon as the fairway had been swept once. Once the convoy system was introduced, there could be no question of closing a port, so sweepers had to operate ahead of all inbound and outbound convoys to sweep them through the danger area. This new practice began with the Tyne paddle sweepers.

Minesweeping was finally considered effective in 1918. That year only twelve ships were sunk by mines in areas for which the Royal Navy was responsible, which made for an average of eighty-five mines laid per ship sunk, a dramatic improvement over previous figures. The British were, however, uncomfortably aware that the Dominions and overseas governments were not nearly as well-prepared for mine warfare as they were in home waters, so the offensive by minelaying U-cruisers could have been far more effective.

Aside from sweepers, the Royal Navy developed a form of self-defence in the form of paravanes, which towed mine-cutting cables from a ship (at the least, the cable could deflect a mine about to swing into a ship). Paravanes were produced both for warships and for merchant ship self-protection (under the cover name ‘otter’). The paravane secret was given to the US Navy when it entered the war. This is a US Navy paravane. (Kadel and Herbert via US Navy Historical and Heritage Command)

The battleship Emperor of India displays her port paravane ready to stream. The great achievement of paravane development was that the paravane could maintain a set depth and offset from the ship. Paravanes only became obsolete when large numbers of influence mines were brought into service. Otherwise they offered ships valuable self-defence whenever they had to cross areas shallow enough to be minable.

In 1914, the Royal Navy was developing a new sweeper to replace the converted torpedo gunboats, but construction had not yet been approved. First Lord Winston Churchill preferred to convert existing merchant ships and eight cross-Channel or cross-North Sea steamers were taken up, despite their deep draught, as ‘auxiliary sweepers’. The first pair arrived in December 1914; one sank by collision soon after arrival. These ships were soon relegated to ferry and other services during the Gallipoli campaign. No further suitable ships were available, so Churchill reluctantly approved construction of initial ‘Flower’ class sloops.

It was clear in 1914 that a special shallow-draught sweeper with good seakeeping qualities was needed, ideally with a draught less than the tidal range. The Admiralty sought fast shallow- draught ships. At the end of October it seemed that a paddle excursion steamer might be ideal and the Brighton Queen was commissioned, the first of a large number of such ships. After trials of the first six, the Admiralty decided to take up as many as possible, while laying down further ships. Compared to a trawler, the paddler offered shallower draught (6½ft vs 14ft) and higher sweep speed (10 knots vs 6 knots). Over seventy paddlers were hired, average dimensions being 227 × 47 × 6ft 5in (the largest was 280 × 65 × 7ft, the smallest 177 × 48 × 12ft). It was initially imagined that the paddlers would not be good seaboats, but that was not the case. Ships were fitted with a gallows, winch, minesweeping stores, guns, ammunition and increased coal and water stowage; as fitted some could keep the sea for four to six days. The great advantage of the paddler was that she had no screw to foul the sweep or kite war, so that when an obstruction was found she could instantly reverse. On the other hand, in rough weather it was dangerous for two of them to approach each other closely.

In May 1915 the Admiral of Minesweeping reported that the paddlers were far better than other minesweepers, so he asked for an Admiralty-built class of them. The main requirements were a sea speed of 15 knots (sweep speed 12 knots), one week endurance at sea, strengthened bows and good watertight subdivision, a small crew, wireless and draught not to exceed 7ft forward or aft. Based on reports from sea, the Ailsa-built Glen Usk was chosen as the basis of the Admiralty design. Larger bunkers were provided and two boilers, so that they could be placed fore and aft of the engines, for better subdivision. Shell plating was thickened and carried up to the upper deck. That greatly increased reserve buoyancy. Armament was two 12pdr 12 cwt guns. While the first batch was being built, it was decided to provide them with seaplanes so that they could maintain a patrol 70nm from the coast, to intercept Zeppelins offshore. Provision was made, but because construction was so urgent the seaplanes were never fitted. In service it turned out that even a slight heel greatly affected speed, as it lifted the paddles on one side out of the water. Ships therefore had special anti-heel tanks in their sponsons. Designed speed was 15 knots, but owing to underpowering the average speed was 14 knots; sweep speed was 9 knots. The initial group comprised twenty-four ships (seventeen ordered September 1915, another four in October and three in January 1916), followed by another eight in January 1917. Five more paddle sweepers, named after sea birds, were ordered in 1918 but cancelled on 10 December. Two more may have been planned but were not ordered.

Royal Navy sailors adjust a paravane.

The paddlers were not entirely satisfactory, as mines could get under the paddles. Moreover, paddlers were inefficient in anything like heavy weather. Early in 1916, therefore, DNC designed a more conventional twin-screw sweeper, the ‘Hunt’ class, for a sweep speed of 12 knots. Because these ships were much faster than the paddlers, they were suited to Grand Fleet service and could replace the ‘Flowers’. They had much the same draught as the paddlers, but were faster (16 knots, typically 17 knots on trials). They were smaller than the Admiralty paddlers (730 tons vs 810 tons, 230 × 28 × 7ft vs 245 × 58 × 6ft 9in). There was some fear that due to their shallow draught they would race their propellers in any sea, but in fact they raced less than either the gunboats or the sloops and could easily sweep in all weather. Like the paddlers, they were armed with a pair of 12pdr guns; they also had two 2pdr pompom anti-aircraft guns.

Twenty were initially ordered. All twelve initially completed were assigned to the Grand Fleet. The first joined at Rosyth during the last month of 1916. The first repeat order was for fifty-six, but by November 1918, 131 ships were either built or building or had been ordered. On 17 December, thirty-five of them were cancelled, followed later by HMS Bolton.

In addition to sweepers designed by DNC Department, the Royal Navy took over a series of shallow-draught Mesopotamia. They had their screws in tunnels to minimise draught and they were given ‘Dance’ names. The first six were transferred in October 1917, the next four in December 1917 and the last four in April 1919. Some were transferred upon completion. Also in 1915, Elco motor launches at Dover, Harwich and the Nore were fitted for local sweeping, using special light gear. They proved fairly successful.

As the Germans mounted their major mining offensive in the spring of 1917, many of their mines were inadvertently moored at shallower than intended depths, causing such casualties to British minesweeping forces in the early part of 1917 that a large building programme had to be mounted. Until it took effect, civilian craft once more had to be taken up. By this time all available paddlers had been taken as sweepers. It proved possible to use a lighter form of ‘A’ Sweep, hence a lighter ship, once the serrated wire had been adopted.49 That brought drifters back into the sweep force. German mines initially sat on the bottom until a timer released them to rise to their set depth. The British therefore became interested in bottom sweeps. During 1917 they developed an otter board bottom sweep worked by drifters. The sweeper force grew from 523 on 1 January 1917 to 643 on 1 July and then declined slightly to 631 on 1 January 1918, in each case including numerous units which might otherwise have been devoted to anti-submarine work.50

Late in 1914 work was underway on a bow protection mechanism. Deflecting wires towed from the forefoot were tried on board the ex-gunboat Skipjack and this equipment was being fitted to the new sloops. The wires were deployed using minesweeping-type kites and booms. However, it proved useless when tried on a larger scale on the battleship Emperor of India. Trials continued using deflecting devices. In 1915 they finally succeeded with the invention of the Burney paravane.

The paravane was a float which could maintain the far end of a wire well outboard of the ship towing it, at a suitable constant set depth. Normally a ship passed a mine rather than collide with it. Her bow wave would push the mine away, but the mine would then swing back and hit the ship. The effect of the deflector bow protection was to prevent the mine from swinging back until the ship passed. It seems to have been generally assumed that the paravane wire would cut the mine mooring, so the effectiveness of the device was often, incorrectly, assessed in terms of the number of mine moorings cut. The British came to see paravane protection not as an alternative to minesweeping, but as an invaluable complement. The usual search methods could not be used effectively against minefields laid well offshore. In some cases ships trailing paravanes were the first to discover new minefields. During 1915 paravanes were fitted to all British warships drawing more than 12ft of water.51 A simplified paravane, given the intentionally deceptive name Otter, was supplied to some merchant ships and the steamship Accrington fitted as an instructional ship at Portsmouth. The success of the paravane led to another application, a high-speed sweep by means of which destroyers could detect or clear mines ahead of a fleet. Like the French ‘B’ Sweep, this one was streamed from either quarter, in this case held down at its inner end by a ‘Tadpole’ kite.52

Soon after the Germans began their submarine mining campaign, the senior officer of the Sheerness Torpedo School (HMS Actaeon), who was responsible for patrolling the Thames Estuary, introduced a new Actaeon sweep based on the French and Russian types. It consisted of a light wire, a small kite and a diving spar with outward thrust carrying an explosive grapnel.53 A patrol boat such as destroyer or torpedo boat towed one from each quarter at a speed of up to or over 12 knots. When the wire hit a mine, its mooring wire slid down and hit the explosive, which parted the mooring and often also exploded the mine. The Actaeon sweep was considered a means of exploring a potential minefield rather than a means of clearing it. The main objections were limited spread and depth and the Actaeon sweep was not widely accepted until much later in the war. It had the great advantage that it was suitable for night work, because there was no need for two sweepers working together to keep station with each other.

German Minesweeping

Like the Royal Navy, the German navy created minesweeping units before the war, organising its first Minensuche (Mine-Seeking) Division in 1905. It consisted of old torpedo boats adapted for the task. These boats they were used both to detect mines and to detect submarines, their mine detection gear either in use or not. They were criticised as too slow and unable to work in a Sea State over 3 or 4. On mobilisation auxiliary divisions were formed using trawlers and drifters. They were far more seaworthy than the old torpedo boats, but they were slower and their draught was greater (as in the British case). As in the Royal Navy, pre-war calls for specialised sweepers had gone unheeded. Once war broke out in 1914, a standard tug-type 450-ton minesweeper (‘M’ class) was designed. The first unit, M 1, was commissioned on 17 July 1915.54 At that time at least three serviceable divisions were considered necessary to open the fairways to the North Sea bases on short notice. The small new ‘A’ class torpedo boats were also used as sweepers.

Once the British began to mine the Heligoland Bight in earnest in 1917, more sweepers were needed, so a 170-ton shallow-water sweeper (FM-Boot, flachgehende M-Boot) was designed; sixty-six were built. Unlike the M-boats the FM-boats were not seaworthy enough for the open North Sea. The Germans also experimented with motorboats (18-ton F-boats drawing about 1m, compared to 1.7m for an FM-boat). UZ-boats conceived as sub-chasers were also used for sweeping (forty-seven built); they were the forerunners of the Second World War R-boats. Finally, most High Seas Fleet torpedo boats (destroyers) could sweep.

At the outset the Germans used a two-ship ‘search sweep’ (minensuchgerät) developed in 1913 by Carbonit, which also developed the navy’s mines. Sweepers were 165 yds abreast, the 275 yd sweep wire being 550 yds astern.55 The sweep was dropped at 7 knots and could be worked at 13 knots, with a maximum towing speed of 18 knots. It could be used at a depth as shallow as 39.3ft (12m), but in order to avoid false alarms when the gear touched bottom, effective minimum depth for sweeping was 50ft. At minimum depth the kite would maintain a depth of 32.1ft and mines would be swept at a depth of 27.2ft (they would still be caught if their upper edges were 22.3ft below the surface). Speed had to be reduced to 11 knots for kite depth to be changed.56 Up to four sweepers could work abreast. The sweep was held down by a kite suspended from a float, a second kite spreading the sweep line away from the sweeper. Note that the sweep was called a search device (suchgerät). At the outset German sweep gear used a grapnel which gripped the mine underwater when it cut the mooring. In the process many mines exploded. Explosive cutters were introduced during the war.

Unlike the British, the Germans had a separate requirement for barrage breakers (sperrbrecher), which were conceived as fast and effectively unsinkable ships which could create paths through minefields by deliberately exploding mines (a testimony to the inefficiency of conventional sweeping). On the outbreak of war the German navy took up steamers from trade and ballasted them down (to trigger mines) with sand or cement ballast. They had special bow mine protection (projecting wires, not paravanes, which were called spreading boom C), but no other mine countermeasures. In 1918 a net catching gear was being tested. A list of mine countermeasures dated March 1918 included an Otter mine clearer which could be towed at 4 to 9 knots and was presumably intended as a replacement for the boom. They were considered too slow and too vulnerable, the ballast having reduced their buoyancy. The sperrbrechers seem to have been conceived particularly to lead the fleet through supposed minefields in the German Bight.

During the war the Germans developed a considerable variety of minesweeping devices, which they grouped either as mine-seeking (MS) or mine-clearing (MR), or mine-protective (self-protection) gear (G).57 MS gear was intended for accurate mine search up to Sea State 4, route searching up to Sea State 5 and single-ship operation up to Sea State 6. SMS was rapid (Schnell) search gear for destroyers (fleet torpedo boats). MR gear was intended for use up to Sea State 4, with light or heavy kite. Sea State limits were imposed by the ability of the kite to maintain depth.

The pre-war type was probably the light kite MS (a type with 2/3 kite was used only on board mine-clearing divisions). There was also a 300m MS (300m swept path [328 yds]), which could be set to sweep mines at depths of 4 to 7.1 fathoms at a speed of 10 knots. Single-ship sweep gear was introduced during the war, initially using a grapnel. It could be towed at up to 11 knots and path width was 120 yds; depth limits were 3.3 and 8.2 fathoms. The M-boats alone had a single-ship sweep with explosive cutters, presumably similar to the French sweep.

For mine clearance there were light kite sweeps with either a fork grapnel or explosive cutters, designed to clear a 49.2 yd (45m) path at a minimum depth of 3.3 fathoms (maximum 8.5 fathoms), at a maximum sweep speed of 8 knots. Alternatives were a light kite seeking sweep with explosive cutter (164 yd path) and a single-ship seeking sweep with explosive cutter (120 yd path). There was also a clearing sweep using a heavy kite, which could clear the widest path (328 to 546 yds [300 to 500m]).58

Mine-seeking flotillas typically had light MSG, MS 300 (except for the 4th Flotilla), a light MSG with grapnel, light MR with fork grapnel, light MSG with cutter and heavy MSG (with light MSG with explosive cutter planned). The mine-clearing divisions had a light MSG with 2/3 kite and light MR with fork grapnel. M-boats had single-ship sweep gear with explosive cutters. UZ-boats had light MSG. In March 1918 single-ship mine-seeking gear with grapnels was being fitted to sprerrbrechers.

The Germans may have been alone in using aircraft successfully to spot mines. Their official history is replete with examples of such searches, though clearly they were not always successful.59

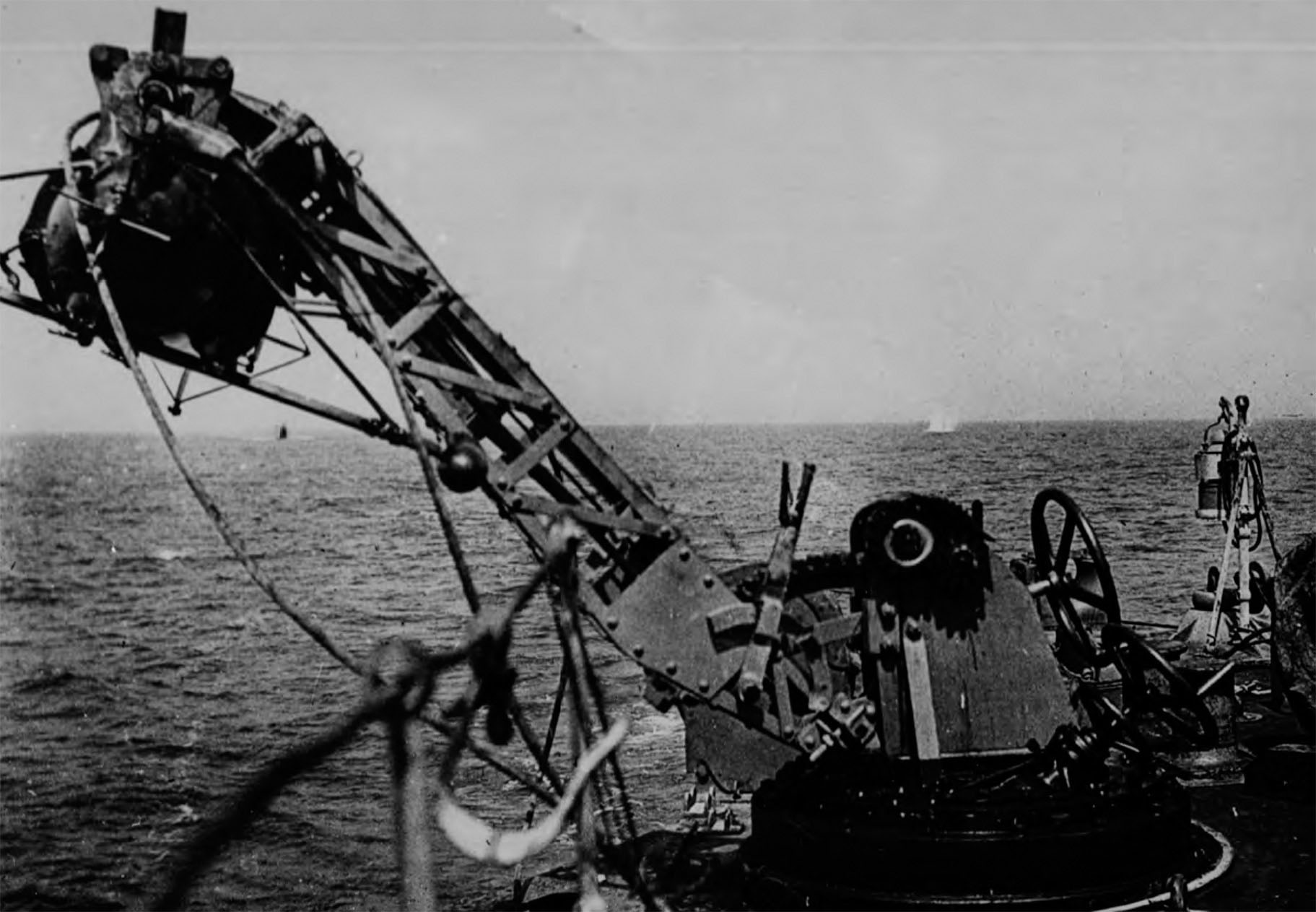

Although the Royal Navy used a two-ship sweep to clear minefields, it fitted destroyers with single-ship paravane sweeps. They would steam ahead of battleships, using these sweeps to ensure that the immediate path ahead was clear. The paravane sweep was called the High Speed Mine Sweep. The destroyer function of keeping the path of the battleships clear of mines – and submarines – remained between the wars and into the Second World War. This is a typical destroyer paravane crane, right aft.

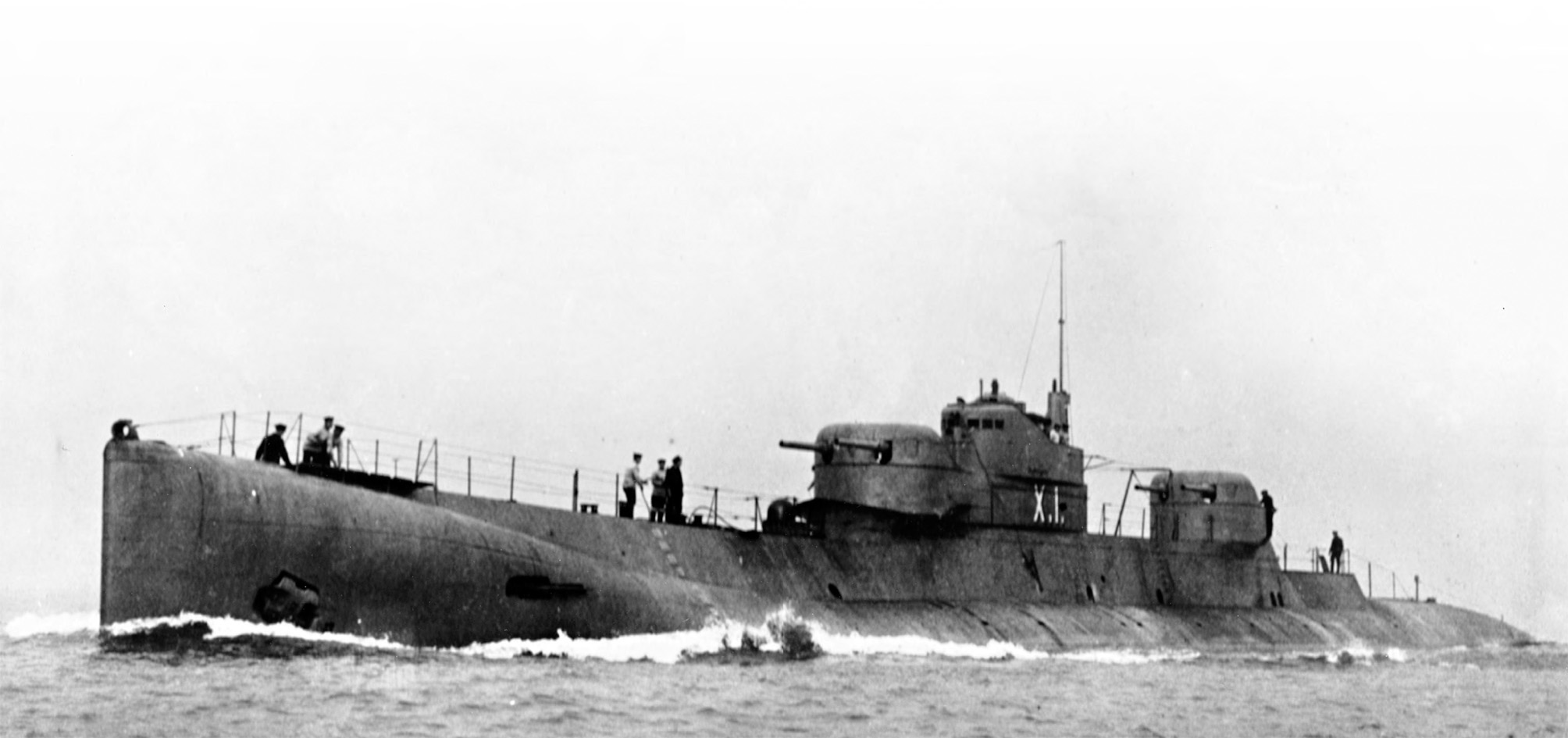

How do you exploit the advantages of the submarine without bringing neutrals into a war? One answer was the submarine cruiser – a submarine designed to surface and deal with merchant ships one by one. HMS X 1 was the British version (the French built Surcouf). She was armed with a pair of twin 5.2in guns (the design originally called for twin 4in guns). The Naval Staff had sought permission to lay down such a submarine in 1918, but they were turned down because the project was not considered sufficiently important. The project was revived in 1920.