JACQUES LEZRA

[W]hat needeth a Dictionarie? Naie, if I offer service but to them that need it, with what face seek I a place with your excellent Ladiship (my most-most honored, because best-best adorned Madame) who by conceited industrie; or industrious conceite, in Italian as in French, in French as in Spanish, in all as in English, understand what you reade, write as you reade, and speake as you write; yet rather charge your minde with matter, then your memorie with words? And if this présent presènt so small profit, I must confesse it brings much lesse delight: for, what pleasure in a plot of simples, O non viste, o mal note, o mal gradate, Or not seene, or ill knowne, or ill accepted?

—John Florio, A Worlde of Wordes

The Manifesto, says The Manifesto in German, will be published in English, French, German, Italian, Flemish and Danish. Ghosts also speak different languages, national languages, like the money from which they are, as we shall see, inseparable. As circulating currency, money bears local and political character, it “uses different national languages and wears different national uniforms.”

—Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx1

Globalization has taken our tongues from us—local, autochthonous, idiomatic, ancestral tongues. Its clamorous internationalism hangs critics on a mute peg, with no common voice or general vocabulary on which to string alternative inter- or transnational forms of work, thought, and organization. And so the disarmed, heteroglot opposition takes shelter in various weak utopianisms, in weakly regulative images generally and understandably drawn from increasingly abstract domains (from reinvigorated notions of the “human” and of “humanism,” for instance or, most recently, from the sketchy descriptions of an antihegemonic Europe that Jürgen Habermas and Derrida erect against the depredations of the United States in Iraq and elsewhere). Consider for example these words from Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire, in which an active and complex ethic of circumstantial translation serves this sheltering, utopian function:

[T]here is no common language of struggles that could “translate” the particular language of each into a cosmopolitan language. Struggles in other parts of the world and even our own struggles seem to be written in an incomprehensible foreign language. This too points toward an important political task: to construct a new common language that facilitates communication, as the languages of anti-imperialism and proletarian internationalism did for the struggles of a previous era. Perhaps this needs to be a new type of communication that functions not on the basis of resemblances but on the basis of differences: a communication of singularities.2

Not a little pathos inflects these lines, in which Negri and Hardt seek to recast the grammar of organic, critical, intellectual discourse in the wake of the collapse of state socialism. Their acknowledgment that the global vocabularies of more or less orthodox, internationalist Marxisms disastrously ignored every struggle’s particularities quickly becomes a way of reflecting upon the increasing fragmentation of current critical idioms. For Negri and Hardt, the peculiarity of one or another circumstance requires—the injunction is distinctly an ethicopolitical one—an act of translation into a “new common language,” imagined here as a “communication of singularities” in both senses furnished by the genitive: communication between radically particular, circumstantial “struggles,” and the communication of that particularity across national, linguistic, political, and other frontiers. (The massive, coincident global protests against the war in Iraq surely furnish a vivid example of this double translation.)

Set aside the claims of novelty (the “new common language,” the “new type of communication” that Negri and Hardt describe). A part of the appeal of Empire (and of many of the most effective, weak-utopian critiques of globalization) is surely due to the odd familiarity of its prescriptions. Thus the concept that Empire seeks to furnish for weak-utopian “translation,” a vehicle for the “communication of singularities,” has the unmistakable shape of the general equivalent or index commodity value.3 (Empire shifts the equivalent’s indexing function from the general economic domain, to the critico-descriptive one.) So also the figure of the critic, whose new, singular “translations” retain the roughly Gramscian gusto for reasoned sabotage that Negri’s early writing provocatively displays. Even the notion of oppositional internationalism itself, one might argue, arises alongside the earliest understandings of the nation form, as Europe reached in the course of the sixteenth century for a cultural, economic, and political modernity whose defining description would not arrive until much later.

Say then that we seek useful, consequential discursive alternatives to globalization—a “tongue,” a cosmopolitan epistemology, a new international. We ask in this context what might be the genealogy of the recent turn to “translation,” of its “new” characterization as a communication of singularities, of its deployment as a weak-utopian concept on which a critique of economic and cultural globalization can be mounted. We understand these questions to be prefatory but necessary to considering the ethico-political demand made for contemporary intellectuals in works like Empire, or by critics like Edward Said, Homi Bhabha, Derrida, Habermas, and others. Even posing these roughly genealogical questions requires of us a peculiar set of historical translations among the contemporary moment, the defining and familiar nineteenth-century historiographic devices that continue to inform our postmodern vocabularies, and the early modern historical moment when technological, demographic, and other shifts bring the twin knots of incipient nationalization and linguistic translation to the fore, and into explicit contact with each other.4 So let’s open this wavy, genealogical avenue by observing that Ernest Renan’s own, famous question of 1882, “Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?” is already determined and over-determined by a fantastical voluntarism built about and against an earlier understanding of linguistic identity that is troublingly fluid, or fractious, or heteroglot. In a word, against an early modern form of collective and individual identity that cannot be translated into “national” or protonational collectivities. But as he moves famously toward his definition of the nation as “a soul, a spiritual principle,” Renan appears untroubled. He considers and sets aside the concept’s traditional vehicles: race, “ownership in common of a rich legacy of memories,” religion, common interests, and geography.5 Only when he takes up “le langage” will Renan’s most searching claim clearly emerge: “There is in man something superior to language: and that is the will” [Il y a dans l’homme quelque chose de supérieur à la langue: c’est la volonté].6 La volonté. For Renan, the notion braids together in time and act the juridical and the psychosocial domains, tidily gathered in this grammatical triplet: “current consent, a desire to live together, and the will to value the undivided heritage that one has received” [le consentement actuel, le désir de vivre ensemble, la volonté de continuer à faire valoir l’héritage qu’on a reçu indivis]. Note the distinctly pre-Nietzschean priority granted to the will over historical accidents, as well as the almost scholastic certainty “Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?” expresses that the faculty can be cleanly separated from contiguous faculties and concepts (memory, desire, interest). Renan’s earlier remarks “Des services rendus aux sciences historiques par la philologie” (1878) make the point again, starkly: “the nation is for us something absolutely separate from language” (chose absolument séparée de la langue). “There is something that we place above language and above race,” Renan continues, “and that is respect for man, understood as a moral being,” a “being” whose moral autonomy is manifested characteristically, as in Kant and in the ethico-political tradition that flows from the second Critique, as a “will to continue living together” (volonté de continuer à vivre ensemble).7

For Renan, as for his contemporary Jakob Burckhardt, the highest political example of the superceding of linguistic particularism is Switzerland; the highest historical examples of the autonomous acts of will that constitute the decision “to continue to live together” are to be found among the “great men of the Renaissance, who were neither French, nor Italian, nor German. They had rediscovered, by means of their traffic with antiquity, the secret of the human mind’s true education” [Ils avaient retrouvé, par leur commerce avec l’antiquité, le secret de l’éducation véritable de l’esprit humain].8 Both the location and the period are unsurprising choices. We know that England, Spain, and Italy saw a remarkable burst of published translations from the classical languages by the last quarter of the sixteenth century, but the emergence of what can fairly be called a European humanist lexical culture dates perhaps to the appearance of Nebrija’s influential 1499 Gramática, or to the publication in 1502 of Ambrosius Calepinus’s Cornucopiæ (later re-edited and better known as the Dictionarium or as the Calepino).9 By “lexical culture” I mean the loose subgroup of practices and ideologies that surround and concern the writing, copying, printing, and transmission of lexicons, grammars, hard-word books, and dictionaries, both monolingual and multilingual, in the new print culture of the European elite.10 What better evidence that language is imagined to serve the will, than that provided by these various texts, intended as linguistic instruments for teaching oneself, or others, different languages? And I intend the double stress on “Europe” and on the “human.” Pari passu with recognizable local or even (proto-)national forms of identification (you and I identify with each other as speakers of this or that distinct and historically discrete language, or as subject to the same autochthonous political and economic regimes), the Renaissance’s traveling books and manuscripts about words, calepinos, trésors, florilegia, gramáticas, primers on translation, and assorted other metalinguistic texts furnish spectacularly deterritorialized, polyglot identities.11 This for instance is from Sebastián de Covarrubias’s 1611 definition of lengua, “tongue”; remark the suturing work that the term “human,” humano, performs, as well as the characteristic stress on the pedagogical scene:

La noticia de muchas lenguas se puede tener por gran felicidad en la tierra, pues con ellas comunica el hombre diversas naciones, y suele ser de mucho fruto en casos de necessidad, refrenando el furor del enemigo, que hablándole en su propia lengua se reporta y concibe una cierta afinidad de parentesco que le obliga a ser humano y clemente…. Yo también me contentaría con que los professores de qualquiera facultad supiessen y aprendiessen juntamente con la lengua Latina la lengua Griega; pues para toda diciplina sería de grandíssima importancia.

[Knowledge of many tongues can be a matter of great happiness on earth, for with them man can communicate with diverse nations, which can be of great profit in case of need, as it dampens the fury of the enemy, for, speaking to him in his own tongue, he moderates himself and conceives a certain familial affinity that obliges him to be human and merciful…. And I too would be satisfied if teachers of any subject knew and learned the Greek language alongside Latin, for this would be of great importance for all disciplines.]12

For the historiography of the late Enlightenment, then, the Humanistic internationalism one glimpses here is both an effect and the primary source of early modern, European lexical culture. The knotted, fiercely overdetermined concept takes shape in association with the loose origins of modern disciplinarity, in hand with the work of (linguistic, cultural, and historical) translation, inseparably from post-Tridentine philosophico-religious debates concerning the nature and attributes of the will, and braided with an ethico-organic “conception of familial affinity” among “humans” from which flow distinctly political forms of identity, association, and obligation. Recall, too, in this sketch of the discursive thicket embrambling lexical culture with protonational identification in early modern Europe, and in its defining historiographies, the double work that Renan’s term “commerce” carries out. The emergence of protonational formations coincides not just with the rise of a speculative class of “grands hommes” belonging properly to no particular nation (“ils n’étaient ni français, ni italiens, ni allemands,” writes Renan), but also with the consolidation of a commercial, merchant class equipped (financially, technically, culturally) to negotiate the diverse requirements of different trading circumstances. More forcefully: the circulations of lexical culture and the earliest construction of an international commercial regime (inter-European, pan-Mediterranean, or trans-Atlantic) cannot be separated from each other. Internationalist, lexical humanism arises with, conditions and enables (is conditioned and enabled by) commercial flows based in and profiting from increasingly differentiated commodity and labor markets—hence the peculiar ambivalence of all recent appeals to a “humanist” alternative to the encroachment of globalization under information-capitalism.13

Or put it like this. After Renan, Burckhardt, and Marx, after the aestheticopolitical concepts of the “nation” and the “civilization of the Renaissance” assume their well-known organizing function in the historical epistemologies of the middle nineteenth century, as the notion that a “new mercantilism” characterizing European trade from between 1570 and 1620 comes to form the basis of “modern,” labor-based economics, we are free to derive from texts like Covarrubias’s the determining image of a network of “grands hommes” and great educators linked in a reciprocal commerce with antiquity when not with each other, a baggy network of scholars, merchants, and courtiers trading texts, commodities, and ideas across and against the grain of religious, linguistic, and protonational differences. This translating figure (it can be many-headed: think of Pico, Erasmus, Covarrubias, Marguerite de Navarre, More, and others) represents the shadow-form of a conciliar orthodoxy with equally internationalist reach and desires: indeed, the institutional history of the Counter-Reformation Church after Trent cannot be understood except in light of the uncomfortable propinquity between conciliar ecumenicism and humanist internationalism.

Think again of the heroic shape that the ethico-political demand takes in Negri and Hardt’s Empire. For them, as for the great nineteenth-century historiographies that they seek to renew, the modern subject’s movement beyond a local, native language, beyond a received legs de souvenirs or a limiting autochthony, is achieved just as the genuine “spirit of a nation” must be for Renan: as a communitarian form of identification deliberately and repeatedly elected. The humanist internationalism that their work recalls thus preserves as a core, determining value the labor of deliberate and informed choice: The archaic function of the will, in its articulation with language and education, is the minimum that differentiates it from conciliar, corporatist internationalism, both in early modernity and in the mediatized postmodernity we inhabit. But the articulation of pedagogy, will and translation at the heart of humanist internationalism considerably precedes the formation of modern “nations” that Renan’s stress on the Renaissance’s “grands hommes” helped to diagnose and to codify. And in certain respects, the translating figure we derive in light of modern historiographies, from Renan to Empire, considerably misconstrues the much more fluid shape that lexical culture furnishes to early modern humanism. The print industry in the time of the grands hommes is still not consolidated, ideologically or technically; easier communication has not yet meant a standardized pedagogy or a conventional “commerce” with antiquity or with religious protocol; the definition of the will’s freedom or servitude in the pedagogical, doctrinal and philosophical domains is sharply and explicitly divided). Impressed decisively into the academic resistance to the ideologies of economic liberalization, the contemporary construction of Humanist internationalism obscures a characteristic troubling of the relation between “will” and “language” to be found at work in the lexical culture of early modern Europe—may, indeed, arise so as to displace or evade it. One might risk a new, rather different return to the “grands hommes de la Renaissance,” to the weakest, that is, to the least “grand” aspects of their thought. In the hesitant translations, in the linguistic troubles we encounter in the work of Covarrubias, Ascham, Minsheu, Verstegan—to say nothing of Machiavelli, Bruno, or Shakespeare—we come across the rough concept for a “common language” for communicating singularities and for “electing” thereby to identify with one or another communicative commonality. The cost we pay for learning this language, for trading in this rough concept, will be high, for in the lexical culture of Early Modern Europe the “will” is invested elsewhere than in individuals: in accidents, contingencies, and “cases” both linguistic and historical. The “communication of singularities” on which early modern lexical culture turns blocks the articulation of individualism, the close cousin (to stay within Covarrubias’s familial metaphor) of humanist internationalism, with will that comes to support the ethico-political project of the Enlightenment.

Here are two useful ways of approaching the matter. The first comes from the series of definitions that Covarrubias provides for the term “translation” in his Tesoro de la lengua castellana. Glossing the hoary etymology that links traducción and “translation” to the Latin trans- and ducere, to carry over or across, the Spanish lexicographer and seeming translator writes: “lleuar de vn lugar a otro alguna cosa, o encaminarla … el boluer la sentencia de vna lengua en otra, como traduzir de Italiano, o de Francés algún libro en Castellano” [To take something from one place to another, or to set it on a path … to change the phrase from one language into another, as when one translates a book from Italian, or French, into Castilian”].14 The geographical vehicle is traditional: linguistic translation—traducción—resembles for Covarrubias merely carrying or returning, llevar or bolver alguna cosa (a national language or idiom, say), from one spot to another. That this alguna cosa remains the same from one language to another simply reflects the underlying ontological stability of things, irrespective of the various names they may carry (a stone is a stone, whether it is called piedra or pierre: only our certainty that this is so allows us to identify “pierre” as a translation of “piedra,” and either as a suitable version of “stone”). The speakers of these different languages borrow from the logically necessary stability of the referent a companion sense that they too are at heart the same—very much, in other words, as one’s capacity to speak another language suggests to an enemy “a certain familial affinity that obliges him to be human.” But linguistic translation also resembles, as the definition’s odd, pseudoappositive shape suggests, just setting something (an idiom, language, cosa) on the road, en and caminar—with no sense that one follows that road oneself, or concerns oneself to ensure that alguna cosa safely reaches the end of the road, or has any stake in how, after all, alguna cosa (a national language, again) might “move” along this or any other road. One might make the point more forcefully by stressing the disjunctive aspect of Covarrubias’s definition: translation is either a way for a subject to carry a particular, identifiable thing from one location in which it has one name, to another in which it has a different one; or it is the gesture of releasing a thing from its name, placing it as it were underway, upon the road, for any one to take. The stakes of this rather recondite grammatical point become clearer if we recall the explicitly political function of the conjunction “o” in the title of Covarrubias’s dictionary: Tesoro de la lengua castellana, o española. The project of national centralization initiated in Spain under the Hapsburgs, as well as the history of local and regional resistance to that project, might be said to hang on the status of this slight “o,” disagreements over different efforts to make lo castellano synonymous with rather than alternative to lo español showing no signs of abating to this day.

Or we might simply read on in the Tesoro’s definition of translation, where it becomes increasingly clear that Covarrubias isn’t quite sure which road a translation actually “takes,” or who or what, for that matter, is taking that road:

TRADVCION … Si esto no se haze con primor y prudencia, sabiendo igualmente las dos lenguas, y trasladando en algunas partes, no conforme a la letra, pero según el sentido sería lo que dixo vn hombre sabio y crítico, que aquello era verter, tomándolo en sinificación de derramar y echar a perder. Esto aduirtió bien Horacio en su Arte poética diziendo, “Nec verbum verbo curabis reddere fidus Interpres.”15

[TRANSLATION … If it is not carried out with care and prudence, knowing both languages equally, and translating in some places, not as the letter demands, but according to the sense, it would be what a wise and acute man once said, that this was to spill, meaning by this to overturn, or waste or spoil something. Horace noted this clearly in his Ars poetica when he wrote: “Nec verbum verbo curabis reddere fidus Interpres.”] (As a true translator you will take care not to translate word for word.)

This seems in most respects perfectly anodyne, even hackneyed. Just what it is that gets “spilled” or “wasted” or “spoiled” when one translates “as the letter demands” remains unclear, however: is it the original’s “sense,” sentido? Manifestly, though not quite, for it is hard to say just what sense Covarrubias intends to give the term sentido in this brief definition, in which the “sense” of “translation” is translated as “overturning” or “knocking something over,” but only if one “means by these” latter terms some “sense” stipulated by the faithful interpreter. “To overturn” or “knock over,” verter, can be rendered as both “to spill,” derramar, and “to waste or to spoil,” echar a perder”: but are “spilling” and “wasting” quite the same? Are they equally good translations of verter? (They are at least not synonyms: things go to waste without being spilled, and vice versa.) The “sense” even of a “wise man’s” phrases requires a gloss, a faithful interpreter, a very inward of the “wise man,” an adviser who already knows the “sense” of his “sense,” the meaning of his meaning. It is not unreasonable to imagine the Spanish lexicographer and pedagogue stepping into this consular role, not just here, where he translates the “sense” of another’s “translation” for his readers, but throughout his Tesoro …, whose definitions set the sense of the Castilian tongue for its users, native and not. And say that we accept the adviser’s gloss, his sense of how the “wise man” intended to render the translation of “translation” as “spilling” or “spoiling,” verter as derramar or echar a perder. Matters get tricky again as we reflect more closely on the three-fold means that Covarrubias suggests for avoiding this wasteful “spillage” (of sense, in whichever sense we take it). In order to translate truly or faithfully, he writes, we must know both languages equally, proceed with prudence and care, and at moments translate “according to the sense” rather than “as the letter demands.” Here the crossing of Horatian poetics with a Pauline hermeneutics (the letters of Mosaic law giving way to the sense or spirit of the new law, as mere obedience gives way to faith) proves less than stable. For just as the “sense” of sentido and of verter turns muddy just where it should be clearest, where it bears the greatest weight, so too does the “faith” or “faithfulness” that guides the interpres lose its sole sense just where it should least require interpreting. The translator’s faithfulness to the original, whether of the plodding, word-for-word sort or of the more delicately interpretive kind, flows not only from his great and equal acquaintance with the languages in translation, but also from his enjoying two distinct affective dispositions (primor and prudencia). These dispositions, Covarrubias’s text makes clear, turn out to be almost incompatible sociologically, and they are aligned throughout the Tesoro with two quite different class positions. “Primor,” which the Tesoro uses (under primo) to describe artisans who do work expertly, is again not only a partial synonym, but also a contrastive term to prudencia, a term associated with “wise and acute or critical” hierophants, and that will notoriously come to characterize no less a figure than Philip II (remembered to this day as el rey prudente). Recall for instance how the distinction between craft and art in treatments of Velázquez’s work supports descriptions, ranging from the psychological to the materialist, of the painter’s ambitions at court (his painting “Las hilanderas,” for example, has appeared to many an allegory of the relation between the material craft of tapestry-making, and the higher art of dramatic representation that true painting strives to capture): in the Tesoro, we might conclude, the translator, both craftsman and “prudent” man, also works both as lengua, Covarrubias’s term for a primarily spoken, mechanical “intervention” (“lengua, el intérprete que declara una lengua con otra, interviniendo entre dos de diferentes lenguas”) and as the intérprete, who works characteristically in writing, with the “alusiones y términos metafóricos” of diverse languages (Covarrubias’s example of bad interpretación is a droll mistranslation from the Spanish of La Celestina into overly literal Italian). But Covarrrubias’s brief descriptions of the work of translation cannot proceed with the schematic hygiene one would expect, given all that seems to hang upon the term. “Care and prudence,” we understand, are needed not only in carrying-over the sense of a phrase, whether “according to the letter” or following the sense of the sentence, but also in distinguishing those moments when one needs to vary from conformity to the letter in the first place. We are not free, in short, to align plain, workaday translation (conforme a la letra) with an inflexible commitment to the letter or the old Law of the text, and the looser, “prudential” translation según el sentido with a new, Pauline attention to its spirit. Merely knowing two languages is not enough; to achieve the intérprete’s prudential understanding of the “sense” of a text, and in order to distinguish when its translation is to be carried out conforme a la letra or según el sentido, is a matter of education, of faith, and of the will.

Now consider how Roger Ascham’s very different Schole-Master (1570) treats the articulation of translation and education in the production of what we are calling lexical culture. Ascham’s concern in The Schole-Master is how best to teach “children, to understand, write, and speake, the Latin tong, but specially purposed for the private bringing up of youth in Ientlemen and Noble mens houses.”16 The Schole-Master’s argument against wholesale “beating” has been a staple of progressive educational theory, in particular these lines that bear on the formation of the child’s will: “Beate a child, if he daunce not well, & cherish him, though he learne not well, ye shall have him unwilling to go to daunce, & glad to go to his booke … And thus, will in children, wisely wrought withal, may easely be wonne to be very well willing to learne. And witte in children, by nature, namely memory, the onely key and keeper of all lerning, is rediest to receive, and surest to keepe, any maner of thing, that is learned when we were yong” (10v–11r). Ascham further warns that the schoolmaster must be gentle in order “wisely” to work the young scholar’s will toward learning, and offers as the practical means and best example of this gentle work what he refers to, classically, as double translation. This is how Ascham puts it:

Translate [some portion of Tullie] you yourself, into plaine naturall Englishe, and then geve it him to translate into Latin againe: allowing him good space and time to do it, both with diligent heede, & good visement. Here his witte shall be new set on worke: his iudgement, for right choice, trewlie tried: his memorie, for sure retaining, better exercised, than by learning any thing without the booke: and here, how much he hath profited, shall plainlie appeare. When he bringeth it translated unto you, bring forth the place of Tullie: lay them together: compare the one with the other: commend his good choice, & right placing of wordes: shew his faultes iently, but blame them not over sharply: for, of such missings, ientlie admonished of, procedeth glad & good heed taking: of good heed taking, springeth chiefly knowledge. (31v–32r)

Ascham’s strategy is a particularly humane one (note the palliative expressions: “good space and time,” “commend his good choice, & right placing,” show faults “iently,” do not blame “sharply,” admonish again “iently”), though it turns on a rather problematical pivot: the supposition that the schoolmaster’s first translation—into “plaine naturall English”—will as it were vanish into Tully’s text on being translated (back) into Latin. The schoolmaster’s “comparison,” “commending,” “showing” and so on depend upon his furnishing a “plaine naturall English” version of the original from which the student can fairly derive an approximate re-translation, an ideal circuit closely reminiscent of the closed geographies we first found in Covarrubias (lleuar de vn lugar a otro alguna cosa, o encaminarla, [to take something from one place to another]). As to the possibility that the schoolmaster may have lost his way, or that his translation may merely have set the Latin text as it were under way, en camino, or that he may have sacrificed sense or “right placing” of words in his desire to produce “plaine naturall English”: in brief, as to the possibility that the first translation should also be the subject of “comparison” with the original (and with the student’s second translation), that the humane authority of the pedagogue, lengua, or intérprete hangs in the balance here as well, Ascham’s work is entirely silent.

It would be anachronistic, not to say absurd, to expect a pedagogy of the oppressed from Ascham, however “progressive” or modern his tone may appear to us. My point is a different one. Note the genuinely remarkable lines with which Ascham closes his description of the pedagogy of double translation: “of such missings, ientlie admonished of, procedeth glad & good heed taking: of good heed taking, springeth chiefly knowledge.” Here Ascham proceeds with great subtlety, combining registers that stress on the one hand the schoolmaster’s disciplinary and monitory role (he “compares,” he “admonishes”), while on the other hand they acknowledge that the pupil’s knowledge itself “springs” from other, mediating and consequent habits that the schoolmaster may have encouraged, but does not directly control. Just as the schoolmaster’s “plaine naturall English” vanishes in the circuit of double translation, so too does Ascham’s pedagogy itself seem to fade from an active, monitory role, becoming merely the occasion for the springing-forth of the pupil’s knowledge. One is inclined to approve this almost Rousseauian account—with the sharp reservation that this double vanishing, of the translation and the translator, lesson and teacher, into the apparent knowledge and the spontaneous will of the pupil finally shelters the schoolmaster (and The Schole-Master) from “comparison,” from “blame,” from admonishment, and from judgments, however gentle, concerning his and the work’s “faultes” and “missings.” In the humane scene in which the pupil’s knowledge and will are fashioned, the technique of double translation vanishingly establishes and then protectively erases from view the school’s mastery and its invisible persistence as the will and very language of the pupil.

My purpose is not to make Ascham and Covarrubias out as precursors of Althusser on ideological apparatuses (a grotesque but appealing thought), but to suggest the nature of the overdeterminations that the concept of translation suffers in early modern articulations of identity. Covarrubias and Ascham embed in their different, complementary descriptions of the translator and of the techniques and purposes of translation local anxieties concerning the translator’s socioeconomic status, concerning the stability of the translated work and the original, the legitimacy of the pedagogical enterprise to which translation seems intimately tied, concerning finally the “freedom” of a will constituted in and by means of this pedagogical-linguistic enterprise. It lies much beyond the scope of this essay to convey a full sense of the economic, ethico-political registers in which these “local anxieties” operate in early modern Europe. We might productively complicate matters, though, by considering briefly two roughly complementary, roughly contemporaneous works, John Minsheu’s 1599 A Dictionarie in Spanish and English, adapted from Richard Perceval’s 1591 dictionary, and Richard Verstegan’s odd and influential A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence in Antiquities; concerning the most noble and renowmed English nation (1605), that more directly link the figure of translation to the consolidation of national identities and trading regimes.

The Restitution opens with a dedication to King James I, followed by an “Epistle to our Nation” in which Verstegan, after noting “the very naturall affection which generally is in all men to heare of the woorthynesse of their anceters” and “seeing how divers nations did labor to revyve the old honour and glorie of their own beginings and anceters, and how in so dooing they shewed themselves the moste kynd lovers of their naturall friends and countrimen,” deplores the prevailing confusion among both “our English wryters” and “divers forreyn writers” (Jean Bodin is Verstegan’s example) between “the antiquities of the Britans” and the “offsprings and descents” of the English.17 The balance of the Restitution … will be devoted to recovering the “true originall and honorable antiquitie” of the English nation, a project animated in seemingly equal parts by the wish to set “the reverend antiquaries” of England straight and by “the greatnes of my Love,” Verstegan says, “unto my most noble nation; most deere unto mee of any nation in the world, and which with all my best endevours I desire to gratify.” It is rather difficult to assess the value that these fulsome expressions of national pride and nostalgia might have had at the time of the work’s publication. The dedication to James, whose Scots and Catholic roots placed him aslant of the dominant British tradition and in particular of Elizabeth’s harshly repressive measures against English recusants, suggests Verstegan’s quite understandable effort to enlist to his cause a monarch whose background seemed briefly to promise much to Catholics. The extent of Verstegan’s own interest in recusant politics, both within and without England, is still obscure—though it was by no means negligible.18 Verstegan was the agent in Antwerp of the exiled English Jesuit leader, Robert Person [Parsons], and was charged by Person with translating and publishing Person’s important Responsio ad Edictum of 1592; animated no doubt by a zeal no less commercial than religious, Verstegan also wrote two pamphlets serving in some measure to preface and advertise the Responsio or Philopater, as it came to be known (after Person’s pseudonym: Andreas Philopater). The Philopater represented the most vigorous and consequential Jesuit response to the 1591 proclamation of Jesuit “sedition,” and more generally to the religious politics of Elizabeth I’s treasurer, Lord William Cecil.19 Verstegan’s two pamphlets, published anonymously in Antwerp in 1591 and 1592, came in the shape first of a Declaration … and then of An Advertisement written to a Secretarie of my L. Treasurers of Ingland, by an Inglishe Intelligencer as he passed through Germanie towards Italie.

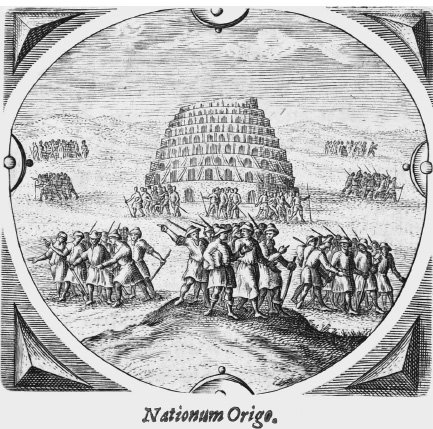

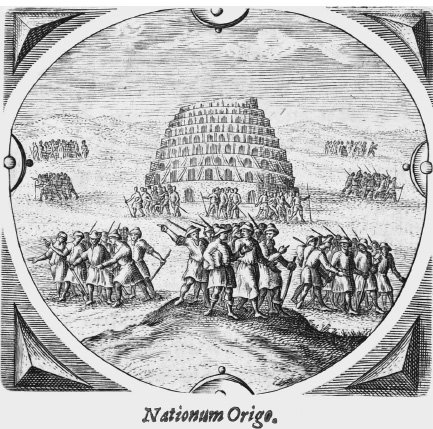

Verstegan illustrates the opening page of the Restitution with an emblem of his own devising, showing the tower of Babel and the dispersal of its builders into different linguistic nations. The emblem’s lemma reads “Nationum origo.”

Image from the opening page of the Restitution, showing the Tower of Babel. Nationum origio, the title vignette from Richard Verstagan’s A restitution of decayed intelligence (London: Iohn Bill, 1628). Reproduced courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, General Library System, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

At the time, and reflecting the influence of Josephus’s interpretation of Genesis 11, the story of Babel was understood as a parable of hubris, and as the origin of linguistic variation from a common tongue.20 The choice of image is of considerable interest, the emblem of Babel conceivably serving in 1605 as a sort of double warning to the new King—against provoking divisiveness within his kingdom, but also, perhaps more interestingly, as a comment on the policies of his predecessor Elizabeth, represented compactly both by the aspiring and quarreling masses hubristically raising the tower of Anglicanism against the Roman church, and as the source of European and national division, of the edicts that provoke England’s division into different (religious and linguistic) “nations.” It is not I think farfetched to imagine the distinctly physiognomic composition of the woodcut (a nasal, phallicoid tower, distant armies resolving into eyes and brows, a cluster of foregrounded squadrons in the triangular formation of a mouth and two cheeks) as a sort of landscaped portrait of the King, a looking-glass emblem of James in the manner of the various chorographic portraits of Elizabeth associating her with her kingdom. Nor can it be discounted, given the peculiarly personal turn that the “Epistle to our nation” takes, that this Babel-faced frontispiece also serves, fascinatingly, as Verstegan’s effort at a self-portrait. Here is how the “Epistle” continues:

For albeit my grandfather Theodore Rowland Verstegan was borne in the duchie of Geldres (and there descended of an ancient and woorshipful familie) whence by reason of the warres and losse of his freindes hee (beeing a young man) came into England about the end of the raign of king Henry the seaventh, and there maried, & soone after dyed; leaving my father at his death but nyne monethes old, which gave cause of making his fortune meaner than els it might have bin: yet can I accompt my self of no other but of the English nation, aswel for that England hath bin my sweet birth-place, as also for that I needs must pas in the self descent and ofspring of that thryce noble nation; unto the which with all dutifull respect and kynd affection I present this my labor.

Victor Houliston has suggested that both Verstegan and Person conceive of the Elizabethan repression of the Jesuit order (and of related events, like the foundation of the Jesuit colleges in Valladolid) on two competing models, a Providential and a consequentialist one (Providential, because divinely sanctioned, motivated and understood; consequentialist, because flowing from freely chosen human actions).21 Houliston has in mind Person and Verstegan’s pamphlets in response to the 1591 edict of expulsion, but a similar hesitation between historiographic models is at work in the Restitution … as well. Here, the story of the origin of nations that Verstegan tells accounts for linguistic variation, and for subsequent scholarly and doctrinal disagreements concerning that variation, by making the unexpected destruction of the original language parallel both to a form of cultural forgetting (nations and national languages drift apart “naturally,” forgetting an original tongue into which they can no longer translate their words); and to the effect of persuasion (by means of untruths, violence, coercion: nations and natural languages are separated by an act or acts of will, divine or human, from each other and from their common tongue). Verstegan’s exile, we infer, is both a bit of Providence and a deplorable human act; he both can and cannot hold Elizabeth (and then James) to account for the repudiation of the Jesuits and for his own circumstances; nations originate in a catastrophic decision, or grow apart gradually, consequentially, without the direct intervention of any human or other agency. The “Epistle’s” autobiographical turn, as well as the odd compounding (if that is what it is) of the figures of James, Verstegan, the Biblical landscape and Verstegan’s “sweet birth-place,” England, would seem to sit uneasily upon this double stool. And perhaps necessarily so: for the Restitution envisions a mythico-religious model of linguistic and national identity characterized by the very exilic insecurity that Babel inaugurates and that Elizabeth later imposes, a model of individual and collective agency built upon the same unresolved hesitation between Providential and consequential accounts of an event’s origins (and of a person’s: Verstegan’s own genealogy, for instance, syntactically atwitch between “albeit” and “and yet,” the two grammatical horns of the providentialist and consequentialist dilemma). The practice, history and theory of translation are for Verstegan the record of this insecure subjectivity.

Minsheu’s situation is on its face much different from Verstegan’s. A teacher of languages in London, he is not directly associated with the Catholic cause. There is some evidence that he was of Jewish origin (a significant detail, Jesuits and Jews being in different ways marginal populations under Elizabeth and James, and more than many others interested for obvious reasons in the economics and cultural-religious politics of translation). Minsheu seems to have led a rather hard-scrabble life, moving at one point to Cambridge so as to finish work on his 1599 Dictionarie … For so minor a figure he is not uncontroversial: the scale and audacity of his scholarly borrowings were such that to this day he is routinely referred to as an arch-plagiarist (Ben Jonson succinctly calls him a “rogue”), though one with a famously enterprising and famously persistent side.22 Finding it hard to scare up a publisher for his Ductor in linguas (1617), Minsheu sold subscriptions to the volume, which he then published himself—the first subscription publication in England; nonetheless, he is remembered by Edward Phillips, in the New World of English Words of 1658, as “Mr. Minshaw that spent his life and estate in scrutinizing into Languages, still remaines obnoxious to the misconstructions of many … invading censurers.”23 His Dictionarie and more obviously still his later and much better known Ductor in linguas, seem oriented toward a coherent articulation of the social sphere, based (like the project of subscription and the enterprise of teaching languages) on the tricky juncture between commercial and linguistic interests.24

Minsheu’s Spanish-English lexicon appeared bound together with a collection of “Pleasant and delightfull dialogues in Spanish and English,” which became strikingly popular on their own, were re-edited by Minsheu in 1623, and translated into French (by César Oudin) and edited separately in Spain as the Diálogos apacibles. …25 The seven “dialogues” bound with the Dictionarie (Oudin adds an eighth, which then becomes part of the tradition of these stories’ reception) are models of language pedagogy, and take their form from Noel de Barlement’s [Berlaimont] Colloquia cum dictonariolo linguarum of 1536, a compendium of polyglot dialogues arranged in parallel columns.26 A sort of precursor to Berlitz’s dialogues, Minsheu’s little exchanges are set in different useful venues: a hidalgo wakes and calls to his waiting-man for his clothes, sword, and dress; yet another hidalgo and his wife shop for silver and jewels; five gentlemen dine together, comment on their food and drink, then play at cards; two travelers, a muleteer and an innkeeper keep company and discuss travel and lodging in Spain; three pages meet after a trip to Court and tell tales; four friends, two English and two Spanish, meet and contrast the customs and language of their countries; and a Sergeant and a soldier discuss the qualities that make a good soldier. The motives of the didactic enterprise are clear, and appear, on the surface, distinctly different from the purpose that Roger Ascham’s Schole-master advanced, some fifty years earlier, for learning Latin: for Minsheu, one learns English or Spanish in order to facilitate economic and social exchange, and his works’ readership is drawn from a merchant or a military class newly able to trade internationally, seeking every advancement in its trade with Holland, Spain, France, Italy, and the Turkish empire and the Mahgrebi monarchies.

It comes as no surprise to us that Minsheu’s dialogues all concern sites of exchange and merchandising, for in his dialogues what Covarrubias calls “La noticia de muchas lenguas” (knowledge of many tongues), not only facilitates travel, the exchange of goods, and social mobility; it is also understood to be a commodity itself, both the means for facilitating exchange and an “object” with value to be exchanged. The duplicity of the language in translation thus makes these dialogues peculiarly reflexive, perhaps even allegorical: Minsheu teaches translation in dialogues that are in part about translation; that make of translation a place-holder for economic value and for economic exchange; and that thus reflect throughout on the economics of translation (its value, its costs, its materials). Take the first two of the “Pleasant and delightfull dialogues.” The first opens domestically; ostensive designations abound as the characters call for the odds and ends to hand in any house. The scene then moves outdoors. In the second dialogue, a hidalgo and his wife go to purchase plate (“In nothing I spend money with a better will than in plate,” opines Thomas, the hidalgo; “That which is laid out in plate is not wasted, but to change small peeces for great peeces,” answers Margaret, his wife) and then jewels (“Now let us go to the place where they sell Iewells,” suggests Margaret. “This is a way that I goe unwillingly,” says Thomas. “What is the reason?” “Because these Iewels are as maidens, that while they are maids, and kept in, they are of much value, and in taking them abroad they loose all, and are worth nothing”). Both the vocabulary and the nature of the objects named has changed. Minsheu’s readers are no longer learning the names of things familiar from the domestic setting, the highly instrumental objects described in the first dialogue—the clothes, shoes, hats, chairs, and other useful matter of day-to-day trade. Between the first and second dialogue, and between the scene in the silversmith’s shop and the scene in the jeweler’s shop, the squire and his wife move not only geographically, as it were, but also in increasing order of economic and linguistic complexity, calling for this or that instrument representing (as even in Augustine) the first order of linguistic acquisition, trading in substitutes (one bit of plate for another, just different sizes) representing a second order of linguistic complexity (in which words retain a substantial, material identity with each other), and trading in jewels representing a third, dangerously public, uprooted and exposed order of linguistic complexity (like a maiden’s worth, the value of a jewel depends, as Thomas wrily notes, on another bauble, reputation). The risks of the market are here the risks to which the new speaker of another tongue also exposes himself: a loss of value, of sense, dignity, “maidenhood,” and of a private, linguistic, and domestic domain in which to “keep” them safe. It is no surprise that one requires a guide, a pedagogue or a ductor, as one ventures into the exile of the streets, of the market, of another language. The pedagogical value of Minsheu’s lesson is largely established in the content of his dialogues, which set on stage not just the benefits of language acquisition, but also and as critically the risks it entails, and thus make clear (as in Ascham and in Covarrubias) the value of the school master, lexicographer, fidus interpres or pedagogue in guiding the exposed pupil through these shoals.

Or so it would appear. For Minsheu’s first dialogue expresses rather more hesitation about the socioeconomics of value (and about the value of the pedagogy of translation) than we might expect. The dialogue concludes with this exchange between the two servants, in which the virtue of knowledge finds a kind of check:

ALONSO: O quanto polvo tiene esta capa!

AMA: Sacude la primero con una vara.

ALONSO: Ama, más que vien hechos están estos calçones.

AMA: Tan bien entiendo yo de esso, como puerca de freno.

ALONSO: Pues qué entiende?

AMA: A lo que a mí me importa si tu preguntáras por una basquiña, una sáya entera, una ropa, un manto o un cuerpo, una gorguera, de una toca y cosas semejantes, supiérate yo responder.

ALONSO: De manera que no sabe léer, mas de por el libro de su aldea.

AMA: Quieres tu, que sea yo, como el ymbidióso, que su ciudado es en lo que no le va ni le viéne.

ALONSO: Siempre es virtúd savér, aunque sean cósas que parece que no nos ympórtan.

AMA: Bien sé yo, que tu sabrás hazér una bellaquería, y ésta no es virtúd…. A ora hermano dexate de retóricas y has lo que tu ámo te mandó.

ALONSO: Sí haré aunque bien créo que no por esso me tengo de asentár con el a la mesa.

[ALONSO: Oh what a deale of dust hath this cloke?

Nurse. Beat it out first with a wand.

A. Nurse, how exceeding well are these breeches made.

N. I have as good knowledge therein as a sow in a bridle.

A. What have you knowledge in then?

N. In what belongeth unto me, if thou hadst asked of a peticoate, a womans cassocke, a womans gowne, a mantell, a paire of bodies, a gorget, or a womans bead attire, and like matter, I could have answered thee.

A. So then the Priest cannot say Masse but in his owne booke.

N. Wilt thou, that I should be as the envious person which setteth his mind on that which belongs not unto him.

A. Yet alwaies is it a vertue to know, although they be things which seeme not to appertaine unto us.

N. I know well, that thou knowest well how to play the knave, and that I am sure is no vertue…. Now Brother, leave your Rhetoricke, and doe that thy Master commanded thee.

A. So will I doe, although I beleeve, for all that I am not to sit at table with him.]

The dialogue’s brief turn at the end, the wry observation on the part of Alonso that he will not sit at the table with his master, has the effect of placing in question much of the value that the dialogue has rested on the transportability of knowledge—what the Spanish renders as “sabe leer, por el libro de su aldea,” and the English, rather more polemically, as “the Priest, cannot say Masse but in his own booke.” Doing what the master commands will not bring one to the table, Minsheu’s character says—but perhaps, we are left to think, a little bit of “envy” will manage to do so.

What is the nature of this “envy”? And why does envy, rather than any of the cardinal virtues, prove to be the ground for social mobility? In what ways are envy and translation related? Set these questions aside for the moment. Minsheu seems to have been entirely aware of the provoking duplicity of his dialogues; indeed, he seems to take a particular pleasure in showing how translations suddenly acquire quite searching ethico-political implications. Take his Spanish dedication to the suspiciously Shandean figure of Don Eduardo Hobby.27 The queer mixture of bombast and flattery veils, none too thickly, a fable moralized politically, and bearing on a topic much in the air as Elizabeth’s reign drew to a close, and in the months following the deaths of her Spanish rival and near-consort, Philip II. It is, precisely, an argument against the social function of envy, a passion excited but also regulated by the artist. Minsheu opens his dedication relating a well-known story about Apelles,

que aviendo acabado de pintar una hermosa tabla, teniendola colgada en parte publica, inumerable gente de todas suertes combidada de la lindeza della … entre los de mas, se acerto a llegar un rustico labrador, y como todos alabassen grandemente el ingenio del artificio, iuntamente con la pintura: el villano, con boz roonca y mal compuesta, dixo, una gran falta tiene esta tabla; lo qual como oyesse Apeles, le pregunto qual fuesse esta? El respondio, aquella espiga sobre la qual esta aquel paxaro sentado, deviera estar mas inclinada, porque conforme al peso que presuppone el paxaro y la flaqueza de la caña, no podia sustentarle sin doblarse mas, oydo esto por el pintor, vio que tenia razon el villano; y tomando el pincel, emendo luego alla falta, siguiendo su parecer; soberbio pues el rústico con ver que se uviesse tomado su voto, passó mas adelante, y dixo, aquellos çapatos que aquella figura tiene no estám nuennos, a esto le respondió Apeles, Hermano, cura de tu arte, y dexa a cada uno el suyo. Esta figura, muy ilustre señor, he querido traer, por dezir, que si todos los hombres se conformassen con lo que saven y que su ingenio alcança, no quisiessen passar adelante, a saber lo que no es de su profession ny les toca, ni ellos quedarian corridos, como este villano, ni el labrador se entremeterría a tratar de la guerra, ny el mercader de la cavallería … sino que tratando cada uno aquello a que su capacidad se estiende, y no mas, seria un concierto maravilloso, que resultaria en grande utilidad de toda la republica, y para esto devriamos tomar ejemplo de las cosas naturales, las quales perpetuamente guardan su orden y concierto, sin entremeterse las unas a hazer el oficio de las otras…. Pues aviendose de guardar éste concierto y órden, a v.m. conviene y toca el juzgar de esta mi obra …

[[Apelles] who, having completed a lovely painting, hung it in a public spot, where numberless people flocked, attracted by its beauty … among these, a rustic peasant happened by, and as all those present were praising greatly the ingenuity of the artifice, as well as the painting: the villain, with a hoarse and ill-formed voice, said: this piece has a great flaw. When Apelles heard this he asked what the flaw was. The peasant answered, that sprig of wheat on which that bird is sitting, should be bent further, because if one takes into account the weight of the bird and the thinness of the stalk, it could not hold the bird without bending further. When Apelles heard this he realized that the villain was right; and taking up his brush, he corrected the mistake, as he saw fit. The peasant, swollen with pride because his advice had been taken, went a step further, and said, those shose that that figure is wearing are not [correct]. Apelles answered him, Brother, stick to your art [arte], and let each mind his own. I have adduced this figure, most illustrious sire, so as to say, that if all men confined themselves to what they know and to the reach of their native wit [ingenio], they would not want to go beyond, and seek to know what is not of their profession [professión] and doesn’t concern them, and they wouldn’t be offended, as this peasant was, nor would the peasant intrude with opinions concerning the war, nor would the merchant opine about cavalry … but rather as each would treat only that matter to which his capacity extends, and none other, a marvelous concert or harmony would ensue, which would be of the greatest utility for the whole republic, and to this end we should take our example from natural things, which keep their order and arrangement perfectly, and none of them interrupts another seeking to do the other’s job…. And since this order and harmony must be maintained, it is your honor’s part to judge this my work …]

The anecdote finds its way to Minsheu from Pliny, and by the time the English lexicographer and cultural entrepreneur employs it the proverb embedded within the anecdote–Ne sutor supra crepidam, roughly “let not the cobbler aspire above his last,” or in Spanish Zapatero a tus zapatos—has acquired a most respectable Humanist pedigree, having been collected and moralized in Erasmus’s Adagia and largely glossed by his followers. The “Dialogues” follow a variant reading that if anything tightens the slight conceptual knot in the scene.28 What Minsheu’s dedication refers to as “concierto,” something like social harmony, effectively excludes the figure of Apelles himself (he conceals himself, provokes comment in the street, functions as a sort of permanent threat of duplicity and surveillance—a whiff of Platonic indignation at the social role of art seems patent). This exclusion assumes a nearly paradoxical shape, however, when the dedication’s device is unpacked according to Minsheu’s loose prescription: Minsheu, the work’s hidden Apelles, presents his tableau to the patron, his judge (“And since this order and harmony must be maintained, it is your honor’s part to judge this my work”), who is now under Pliny (and Minsheu’s) warning not to overstep his competency. The entire edifice of social “order and harmony” hangs upon the appropriateness, one might say, of the patron’s experience and past knowledge to his current judgment: Ne sutor supra crepidam. The dedication appears in this way to anticipate the conclusion to Minsheu’s first dialogue, in which the Ama’s satisfaction with her own (social and other) limitations serves to contain the rather more subversive “envy” expressed by Alonso, the page.

Two aspects of the scene disturb its sense of “concert.” Would one need to warn one’s patron, as it were to prompt him not to stray above his shoes, if there were no danger that his judgment might not, after all, quite fit with his experience? Or say that one accepts this aesthetic “concert” as a model of social and economic harmony, status and experience in perfect accord, the soothing fantasy of an entirely saturated, transparent polity whose “parts” marry organically, working each with each. (One thinks here of Hardt and Negri’s “communication of singularities,” or of a Habermasian ideal-speech situation a bit avant la lettre.) Where in this aristocratic fantasy would the marginal, scrabbly figure of the pedagogue, of the translator, of the enterprising salesman of subscriptions belong? More particularly, What would didactic texts like the “Pleasant and delightfull dialogues” and the Ductor in linguas actually teach? The linguistic economy of Minsheu’s dictionaries and dialogues turns on an altogether different sense of the relation between experience, knowledge, class, and judgment than his “Dedication” advances—and they furnish a radically different account of the mobile, “envious” political economy of the early market. From its very opening, then, the work accosts the reader. Either the dialogues have no didactic function, or have only the function of conveying the exact translation of an existing state of affairs (the rustic voice of the laborer remains just that, unimproved by works he cannot judge, or understand); and the figure that Minsheu brings to bear in the “Dedication” only “teaches” Edward Hobby to recognize himself (in the warned figure of a “judge” who must not stray outside what he already knows); and the “Pleasant and delightfull dialogues in Spanish and English” themselves “please” and “delight” without in any way facilitating social, commercial, or international mobility (of the sort that would allow a “villein” to become a “shoemaker,” or a shoemaker to “set[ ] his mind on that which belongs not unto him,” move beyond a local market, change his tongue, export his wares, eventually aspire to “sit at the table” of an Edward Hobby). Or else the “figure” that Minsheu employs in his dedication is entirely improper to the “Dialogues,” slily open to correction, calling for a figure—a humanist, a trader in cultural translations, a figure with a mobility of intelligence and experience to match the political-economic instability and disconcerting he will come to represent—able to understand the bent or veiled critique of aristocratic functionalism that the appeal to Sir Edward Hobby embeds.

Nothing in Minsheu’s work serves to teach us which of these characterizations of his project, and of his readers, Minsheu advocates. But neither are his readers expected to experience the absence of this lesson as a painful lack. Quite the opposite. The stories that the “Pleasant and delightfull dialogues” tell embed scenes in which mistranslation and rhetorical misunderstanding flowing from the absence of criteria for making judgments do not result in disaster of one or another monitory sort. They are prized and enjoyed instead, and work as alternatives to “doing what thy M[aster] commands thee”: the “pleasantness” and “delightfulness” of the dialogues, in short, comes into conflict with their explicit pedagogical role. I’ve mentioned in brief Alonso’s resistance, in the first dialogue, to the Nurse’s fulsome praise of knowledge. By the time that the seven dialogues conclude, what seemed a monitory hesitation has become hinged explicitly with the dialogues’ pedagogical and linguistic project—as though the subtle articulation of reading with the priest’s saying Mass, that occurs in the commerce between the Spanish and the English texts, has become the structuring principle of the dialogues. One learns from these “Dialogues” because of their errors (in and about translation)—but what one learns can no longer in the same way be learned; one cannot, for instance, “learn” from them whether one should aspire to occupy the position of Edward Hobby, of Apelles, or of the sly Alonso, the new figure for mercantilist, envious mobility. To put it more polemically than a brief description can support: what one learns from the “Dialogues’ ” “errors” and paradoxes is no longer the object of the reader’s, or of the writer’s, will.

Like Richard Verstegan, Minsheu thus lights upon a highly unstable account of social and economic “concert,” from which the aristocratic figure of judgment emerges dramatically changed. For Minsheu’s project is not only, and not primarily a critical one (he has many projects, after all). The English lexicographer, translator, and pedagogue is also modestly a political philosopher with an affirmative program to complement a sharply critical one. Minsheu’s radical pedagogy of translation washes the Enlightenment’s fantastical construction of the early modern subject’s political will in revealing acids: the irreducibility of envy; the noncorrespondence between judgment, “taste,” and experience; the provocative vulnerability of one’s linguistic “home” or “nation” as one’s language steps translated into the market. One can get a slightly clearer sense of the disconcerting political philosophy that emerges from early modern lexical culture by returning very briefly to another scene of origins, where “letters,” “ground,” “culture” and their various translations mythically meet. When Covarrubias defines the word “letter” he reminds us that:

Otros sienten auerse dicho à lite, porque de las letras como de los primeros elementos se forman las sílabas, y las dicciones: y para juntarse entre si tienen vna manera de contienda hiriéndose vnas a otras. Y esta es la común moralidad en que se fundó la fábula de Cadmo, que auiendo muerto la serpiente, Minerua le mandó sembrar los dientes della: y dellos nacieron hombres armados, que peleando entre sí se mataron, hasta quedar en cinco. Estas se entienden las letras vocales, que son el origen y vida de las demás, y assi le dan por autor de las letras.

[Others believe it to come from lite, because syllables and statements are formed from letters, as from primary elements: and in order to assemble amongst themselves they have a sort of battle, wounding one another. And on this common moral the fable of Cadmus is based. When he killed the serpent, Minerva ordered him to sow its teeth, and from those teeth were born armed men, who fought amongst themelves and killed each other off, until only five remained. These are taken to be the vowels, which are the life and origin of all others, and hence Cadmus is taken to be the author of all the letters.]

This depiction of a primal battle set in the very cradle of the letter also “kills off” the genteel claims of lexical humanism that Covarrubias advances in defining “tongue,” lengua: the hidden claim that the stability of the referent guarantees the “humanity” shared by speakers of different languages, and the consequent claim that speaking in another tongue “dampens the fury of the enemy, for, speaking to him in his own tongue, he moderates himself and conceives a certain familial affinity that obliges him to be human and merciful.” At the heart of the word, embedded in the letter itself, lies not the “concert” and aristocratic harmony of rhyming “judgment,” “experience,” “familial affinity,” self-identity, and the sort of mutual obligation that turns upon the restraint of the will, but fratricidal conflict, envy, murder, warfare. Not natural law, but the claim of jus naturale or natural right, to turn to Hobbes’s crucial and polemical distinction, makes up the matter of linguistic exchange.29 Not national fantasies, or the deliberate assumption of culturally sanctioned, fantasmatic, and aristocratic genealogies (such as Verstegan and Minsheu’s works glancingly provide their authors and readers), but quarreling, envious, inconstant forms of partial and conflicted linguistic—exical—identification make up the matter of early modern communitarian, political thought. The fidus interpres, the pedagogue, the lexicographer, all charged seemingly with regulating the “world of wordes,” to evoke John Florio’s lovely title, succeed only in telling over Cadmus’s story; their words, syllables or statements (in different languages) about words (that is to say, dictionaries, hard-word books, translation guides, calepinos, florilegia, various “tesoros”) sow serpents’ teeth. Upon this torn lexical ground, this broken, translated culture, competing early modern internationalisms flourish.

Or put it like this: Minsheu and Verstegan (and Covarrubias in Spain) share an understanding of the relation between “will” and “language” that places them closer to Nietzsche and Hobbes than to Renan: for them, translation marks the spot where language paradoxically least lends itself to the will’s use. And in both cases, as in Covarrubias’s enigmatic Tesoro, this torn spot is where a particular social freedom can be located: for Verstegan, the freedom of a certain kind of recusancy, of an exilic, compensatory and riven identity; for Minsheu, a political-economic freedom derived from the disharmony between economic and epistemological interest. In a broader sense, the politico-historiographic tradition that so lionizes the Renaissance’s “grands hommes,” so compellingly holds them up as the models of a modern, Machiavellian, individual autonomy—this tradition arises so as to bypass these two arenas of social freedom—precisely because these “freedoms” cannot be squared with the model of Kantian autonomy on which Renan’s and Burckhardt’s thought rests, and on which the discipline of modern Renaissance studies depends. Likewise, the utopian moment of intellectual internationalism that structures recent work as distant in spirit and argument as that of Derrida, or Negri and Hardt, or Bhabha, or Balibar cannot today be understood without reference to its hidden link with this reactive definition of early modern humanist internationalism. For at the moment of the emergence of the nation form, the lexical culture of translation designates a specifically non-subjectivist form of cultural (self) resistance with consequences so radical as to have generated a whole subdiscipline dedicated to evading it, and a contemporary weak utopianism dedicated to reproducing it.

NOTES

1. My epigraphs are from John Florio, A Worlde of Wordes (better known, in its second, 1611 edition, as Queen Anna’s New Worlde of Wordes), printed in London, by Arnold Hatfield for Edw. Blount, 1598 (n.p.); and from Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, & the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf (London: Routledge, 1994), 104. Derrida is citing from Marx’s Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, trans. by S. W. Ryazanskaya, ed. Maurice Dobb (New York: International Publishers, 1970), p. 107. Except where indicated, the translations throughout this essay are mine. I’d like to express my gratitude to Jason Cohen for his careful help and keen advice at every stage in the preparation of this essay.

2. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), p. 57.

3. The same is achieved, to some extent, by Ernesto Laclau’s call for a “constructed universal.” See Ernesto Laclau, “Constructing Universality,” in Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left, Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau, and Slavoj Žižek (London and New York: Verso, 2000).

4. Much of the recent, fine work discussing the formation of “national” identity in early English modernity draws from Richard Helgerson’s careful and searching Forms of Nationhood: The Elizabethan Writing of England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). I have also found especially intriguing Peter Sahlins’s studies of border communities, especially his Boundaries: The Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989). I hope that my debt to the work of Ben Anderson, Homi Bhabha, and others will be clear throughout.

5. Renan, “Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?” (Conference faite en Sorbonne 11 Mars, 1882), in Ernest Renan, Œuvres complètes, ed. Henriette Psichari (Paris: Corbeil Press, Calmann-Levy, 1947), vol. 1, p. 903.

6. Ibid., p. 899.

7. Renan, “Des services rendus aux sciences historiques par la philologie,” in Renan, Œuvres complètes, vol. 8, pp. 1231–32.

8. Renan, “Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?”, pp. 899–900.

9. One might also list the dictionaries of Estienne (in the 1530s), Plantin (beginning in the 1560s), Florio (1598 and 1611), Perceval, Cawdrey (1604), and Covarrubias (1611 and 1613).

10. Jürgen Schäfer has written of the “insecurity of many speakers” at this time, and of the “socio-linguistic” problem posed in England “at the beginning of the seventeenth century [by] the influx of new words derived from Latin and the Romance languages.” He maintains that “at this critical juncture in the development of the English language a new genre of books … began to appear, the lists of hard words” (in his “The Hard Word Dictionaries: A Re-Assessment,” Leeds Studies in English n.s. 4, 1970, p. 31). This assessment of the lexical “insecurity” prevalent in early modern Europe, and in England in particular, has a different valence in Noel Osselton’s Branded Words in English Dictionaries before Johnson: “To the purist’s protest that the ale-wife cannot know Latin, the dictionary provides the answer: she need not—she need only have access to a dictionary, and then she may understand and speak as finely powdered a language as any” (9). And: “In the early dictionaries … this intention is clearly an educational one first and foremost. The object was to instruct those who did not understand…. Up to 1656 the dictionary was undoubtedly intended for the guidance of those people who were in difficulties among the host of new words; and these included—notably—foreigners, the ladies and the young.” In Noel E. Osselton, Branded Words in English Dictionaries before Johnson (Groningen: J. B. Wolters, 1958), pp. 11–13.

11. In the middle to late sixteenth century the study of the “antiquities” of England—Saxon customs, artifacts and language—was used to assert that the English Reformation was nothing less than a return to earlier forms of Christian worship, a triple articulation of linguistic, “nationalist,” and religious idioms that effectively delegitimates the importation of “foreign” or “Popish” translations of the Gospel. In an early article, Rosemond Tuve linked this well-known historical thesis to contemporary, twentieth-century protocols of research and critical professionalization, briefly opening a fascinating line of inquiry that circumstances—mobilization for a European and American war—soon closed down. See her “Ancients, Moderns, and Saxons,” ELH 6(3), 1939, 165–90. Tuve remembers that William L’Isle calls “ ‘the Saxons a people most devout’ who have left us not only all these monasteries and churches but also ‘in our Libraries so goodly monuments of reverend antiquitie, divine handwritings” (169–70), and she dates the articulation of “nationalist,” religious, and lexical idioms to John Bale and John Leland’s The Laboryouse Journey & serche of John Leylande, for Englands Antiquitees … with declaracyons enlarged, by Iohan Bale (London, 1549). She cites these remarkable lines from the Laboryouse Journey. Addressing the “cyties of Englande,” Bale-Leland cries: “steppe you fourth … and shewe your naturall noble hartes to your nacyon. As ye fynde a notable Antyquyte … lete them anon be imprented … both to their and your owne perpetuall fame” (Cv–C2r).

12. Sebastián de Covarrubias Horozco, Tesoro de la lengua castellana, o española (Madrid: Luis Sánchez, 1611). I have lightly modernized the text.

13. This “increasing differentiation” refers not only to increased technical specialization (on the manufacturing side), or to progressively more specific demands (on the side of consumption), but also to the waning of what Marx calls (but only “approximatively”!) the mythic, early modern “co-operative form” of the capitalist mode of production, the “handicraft-like beginnings of manufacture” [handwerksmäßigen Anfängen der Manufaktur]; see Capital I, 4, ch. 13–14, trans. Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling (New York: International Publishers, 1967), pp. 317–18. For the tradition associating translation with economic value, see Doug Robinson’s “Translation and the Repayment of Debt,” Delos 7(1–2), April 1997, pp. 10–22; and Anthony Pym’s work, especially “Translation as a Transaction Cost,” Meta 40(4), 1995, pp. 594–605.

14. A seeming translator, or perhaps better, a translator barely manqué: at the end of his life Covarrubias was completing a translation into Spanish of Horace’s Odes; the Royal license to print “un libro intitulado Las Sátiras, Epístolas y Arte poético de Quinto Oracio Flaco” was granted a month after the lexicographer’s death.

15. Covarrubias is remembering these lines attributed to Horace: “Publica materies privati iuris erit, si / non circa vilem patulumque moraberis orbem; / nec verbum verbo curabis reddere fidus / interpres, nec desilies imitator in artum, / unde pedem proferre pudor vetet aut operis lex.” Ben Jonson’s 1640 translation, in Q. Horatius Flaccus: his Art of poetry. Englished by Ben Jonson. With other workes of the author, never printed before (London: Printed by I. Okes, for Iohn Benson, 1640, p. 10; reprinted in Edward Blakeney, ed., Horace on the Art of Poetry (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1970, p. 114), reads as follows: “For, being a Poet, thou maist feigne, create, / Not care, as thou wouldst faithfully translate, / To render word for word …”

16. Roger Ascham, The Schole-Master (London), printed by John Daye, 1570 [–71], n.p.

17. Richard Verstegan [a.k.a Verstegen], A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence: In antiquities. Concerning the most noble and renowmed English nation. By the studie and travaile of R.V. Dedicated unto the Kings most excellent Maiestie. Printed at Antwerp by Robert Bruney, 1605; And to be sold at London in Paules-Churchyard, by Iohn Norton and Iohn Bull.

18. For a recent account of Verstegan’s role in the pamphlet debacle that followed the 1591 edict, see Victor Houliston, “The Lord Treasurer and the Jesuit: Robert Person’s Satirical Responsio to the 1591 Proclamation,” Sixteenth Century Journal 32(2), 2001, pp. 383–401, especially 384–93. Anthony G. Petti’s “Richard Verstegan and Catholic Martyrologies of the later Elizabethan Period,” Recusant History 5(2), 1959–60, pp. 64–90, has a fuller account of Verstegan’s role in publicizing the persecution of Catholic dissenters under Elizabeth, in works like Verstegan’s Briefve Description des diverses Cruautez que les Catholiques endurent en Angleterre pour la foy (Paris, 1584) and most importantly in the Theatrum crudelitatum haereticorum nostri temporis (Anvers, 1587). A full account of the impact of Verstegan’s Theater of cruelties may be found in Frank Lestringant’s edition of the work’s first French translation, Le Théâtre des cruautés des hérétiques de nostre temps (Anvers, 1588; Paris: Éditions Chandeigne, 1995).

19. And to his linguistic policies as well: note that Randall Cotgrave, like Ascham before him, dedicates his 1611 Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues (London: Printed by Adam Islip, 1611) to Cecil; clearly Cecil’s circle perceived that the wars of “sedition” were carried out in the domain of the lexical as well. Cotgrave’s Dictionarie addresses to Cecil the following, rather heavily veiled complaint: “My desires have aimed at more substantial markes [than “so meane a Peece” as the Dictionarie]; but mine eyes failed them, and forced me to spend much of their vigour on this Bundle of words; which though it may be unworthie of your Lordships great patience, and perhaps ill sorted to the expectation of others, yet is it the best I can at this time make it, and were, how perfect soever, no more then due to your Lordship, to whom I owe, for what I have beene many yeres, whatsoever I am now, or looke to be hereafter.”