Metrical Translation: Nineteenth-Century Homers and the Hexameter Mania

YOPIE PRINS

The question of metrical translation—its history, theory, and practice—is not often posed in current translation studies, except perhaps by translators who confront “a choice between rhyme and reason,” as Nabokov asked himself in translating Pushkin: “Can a translation while rendering with absolute fidelity the whole text, and nothing but the text, keep the form of the original, its rhythm and its rhyme?”1 Like swearing an oath to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth before going on trial, the translator who vows to be true to “the whole text, and nothing but the text” must be faithful to its form as well as its content. Of course, because every translation falls somewhere between rhyme and reason, the vow of absolute fidelity will be broken, and the translator pronounced guilty. But what happens when the translator tries to do justice to a text by finding another way to tell rhyme’s reason, by re-telling the truth of its rhythm and its rhyme in another form? What happens when meter itself is being translated? Rather than assuming a transhistorical definition of meter as a fixed form that can be transported from source language to target language, we might look for the historical transformation of metrical forms through translation, and so bring into view the cultural function of metrical translation as a complex mediation and recirculation of literary forms at a particular moment within a particular culture.

I offer a case study by looking at various translations of Homer in Victorian England, where debates about translating dactylic hexameter—the metrical form associated with classical epic—were closely linked to the formation of a national literary culture. These hexameter debates went to great lengths to pronounce or denounce English imitations of Classical meter. Not only was this a trial of different systems of versification, ruled by “stress” vs. “length” and arbitrated by poetic justice; it was also a political effort to legislate an English literary idiom that would enable the sort of national identification described by Ernest Gellner in Nations and Nationalism. With the rise of the British empire, as England was struggling to accommodate foreignness both within and beyond its national borders, the consolidation of a common language out of heterogeneous elements seemed especially urgent. One example of this urgency was Matthew Arnold’s plea for hexameter translation in his famous lectures On Translating Homer (1861–62). In urging poets to translate Homer into English hexameters for the cultivation of English poetry and the future of English culture, Arnold anticipated the ideals of criticism and culture articulated in “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time” (1864) and “Culture and Anarchy” (1869). Indeed, as Arnold tried to persuade his contemporaries, the function of hexameter at the present time would be to measure the distance between culture and anarchy.

Arnold’s turn to English hexameters was not a return to the measures of antiquity, but an attempt to create a new measure for modernity that would give order to modern life in the modern nation. In England and Englishness, John Lucas follows Gellner in demonstrating how, as a nation develops, “it becomes increasingly necessary to produce a culture which, in its realization through a formalized common language, seeks to homogenize all members of the nation.”2 According to Lucas, Arnold in particular emphasized the role of poets in formalizing such a language: “Arnold had a very definite sense of what England ought to be, and it did not include the right to utterance by a wide variety of voices,” since he regarded “heteroglossia as a form of anarchy, the clamour of the barbarians at the gates” (9). But even while Arnold prescribed hexameters to hold off the barbarians at the gates, he also opened the gates to various metrical experiments that seemed “barbarous” to the very readers whose Englishness he sought to cultivate. As we shall see, the various hexameter translations that began to circulate in the decade after Arnold’s lectures point to contradictory patterns of reading voice: rather than imagining a unified voice for a unified nation, these English hexameters allowed different forms of Englishness to be performed more equivocally.

The central role played by poets in forming ideas about nation and empire in Victorian England has been elaborated by recent critics, including Matthew Reynolds in The Realms of Verse, 1830–1870: English Poetry in a Time of Nation-Building. The idea (or ideal) of a national literary culture emerged not only through the novel and the newspaper, as Benedict Anderson has argued in Imagined Communities,3 but through the circulation of poetry in print. Reynolds extends Anderson’s argument to show how Victorian poets worked to identify and address a community of English readers: their poems “explore consonances between aesthetic and political forms, so that readers who enter into their realms of verse experience restraints and liberties, and patterns of cohesion and disintegration.”4 Through various kinds of formal analysis, often metrical, Reynolds suggests that such poems recreated the difficulty of creating a coherent English nation, as a composite form with different parts, sometimes coming together and sometimes falling apart. Focusing more specifically on metrical translation, I argue that hexameter translations of Homer also allowed readers to enter into a realm of verse defined by patterns of cohesion and disintegration, and thus to experience forms of continuity and interruption associated with the modern nation. Like other print media, meter served as a medium for the creation of a national literature that could be called English, and although English hexameters may not have produced a homogeneous community of readers (quite the contrary), nevertheless the debates around hexameter served to produce a powerful metrical imaginary in Victorian England. For Arnold and his contemporaries, the nation was a form that might be transformed by acts of metrical translation, and the meter that allowed nineteenth-century poets, scholars, translators, critics, and readers to prescribe this idea of an English national literature was hexameter. Therefore much was at stake in the English hexameter mania: who would be able to legislate a perfect hexameter?

ARNOLD’S MEASURE FOR THE PRESENT TIME

In “The Modern Element in Literature,” his inaugural lecture for the Poetry Chair at Oxford in 1857, the newly appointed Professor Matthew Arnold professed the importance of “literatures which in their day and for their own nation have adequately comprehended, have adequately represented, the spectacle before them.”5 As Arnold defined it, the modern element in all literatures, past or present, is the ability to take the measure of their own time, and thus to give a comprehensive and adequate representation of the present “in their day and for their own nation.” Even ancient literatures have this modern element, especially ancient Greek poetry, for “in the poetry of that age we have a literature commensurate with its epoch” (31). The question for Arnold was, how might English literature achieve such commensurability, in its own day and for its own nation? “Our present age has around it a copious and complex present, and behind it a copious and complex past,” according to Arnold, and “it exhibits to the individual man who contemplates it the spectacle of a vast multitude of facts awaiting and inviting his comprehension” (20). The individual man—say, Arnold—needs a general law to comprehend this complex temporality and give order to the multitude of mental impressions “which we feel in presence of an immense, moving, confused spectacle.” But what kind of law would this be?

A few years later Arnold turned to metrical law, again via the example of Greek literature. In the meters of Homer (whose epic poetry was composed in dactylic hexameter, a line running rapidly in six feet, mostly dactyls), he discerned a movement that might adequately represent and comprehend the multiplicity of the modern age. His lectures On Translating Homer, delivered at Oxford in 1860–61, prescribed hexameter not only for future translators of Homer but also for the future of English poetry. “The hexameter, whether alone or with the pentameter, possesses a movement, an expression, which no metre hitherto in common use amongst us possesses, and which I am convinced English poetry, as our mental wants multiply, will not always be content to forego” (148). If, as Arnold implied, modernity was the demand for the right measure and if, as Arnold believed, England was a nation in need of measure, then perhaps, as Arnold hoped, hexameter would be a way to measure up to these modern times. Indeed English hexameter might even work to displace iambic pentameter with non-iambic measures, and so invent a new national meter. Mediating between continuity and contemporaneity, between the complex past and the complex present, hexameter became Arnold’s measure of, and for, the present time.

Arnold’s turn to hexameter was controversial by definition, returning to ancient Greek versification yet also turning it into modern English verse. His three lectures provoked a wide range of reactions, inspiring some translators and infuriating others, prompting scholarly articles and critical parodies, and fanning the flames of Victorian hexameter debates. What kind of hexameter was Arnold prescribing for English poetry? Quantitative meter, measured by length of syllables, like the dactylic hexameter of Homer or the stately measures of Virgil? Accentual meter, numbered in stressed syllables, like the (too) popular hexameters of Longfellow? Some combination or modification of the two? How would the new English hexameter be written, and by whom? How would it be read, and by whom? And what would it sound like?

In response to skeptics, Arnold gave a fourth lecture to defend the idea of metrical translation, and to define his ideal of hexameter. In “Last Words,” delivered November 30, 1861, he explained how hexameter translations of Homer might work to improve current English hexameters, and train the English ear to hear new rhythms: “In the task of translation, the hexameter may gradually be made familiar to the ear of the English public; at the same time that there arises, out of all these efforts, an improved type of this rhythm” (202). Step by step, placing one foot before the other, English poetry would gradually move toward a new and improved hexameter, conceived by Arnold and born through the labors of poets and translators. And this labor would not be in vain, according to Arnold, as it would give birth to the future of English poetry: “I am inclined to believe that all this travail will actually take place, because I believe that modern poetry is actually in want of such an instrument as the hexameter” (202).

In fact English poets were less “in want” of hexameter than Arnold implied; he was more interested in telling them what kind of hexameter they would, or should, want. If anything, there were already too many English hexameters circulating in nineteenth-century England. In George Saintsbury’s History of English Prosody, for example, we find an entire chapter dedicated to “The Later English Hexameter and Discussions On It.” Surveying the “battle of the hexameter” that dominated Victorian metrical theory, Saintsbury called it “the hexameter mania.”6 Within this unruly proliferation of hexameters, Arnold’s call for new translations of Homer was an attempt to regulate the form of English hexameter, and transform it into an ordering principle for modern poetry. The rapid movement of Homeric hexameter, as Arnold understood it, would thus be “translated” into an English meter commensurate with modern times, not as nostalgia for the time of the ancients but as a way of comprehending the temporality of modernity and the modern nation.

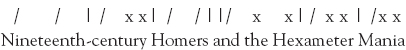

In the decade immediately following Arnold’s Lectures on Translating Homer, there was a proliferation of English hexameter translations.7 Although these Victorian experiments in metrical translation may seem antiquated to us now—a dead end for modern prosody—nevertheless it is worth exhuming some of the hexameter debates that proved so lively in the nineteenth century. Victorian hexameters often sound like a failure, enforcing an awkward pronunciation. This awkwardness is inscribed in the subtitle of my essay, which might be scanned as a line in hexameter as follows:

With a caesura after the third foot (where it never should fall) and a final foot that is not quite a spondee (unless “mania” is elided into two syllables), this line falls short of an ideal hexameter. Its movement is interrupted: the first three feet seem to limp along lamely in spondee, dactyl, spondee, and the last three feet gather dactylic momentum only if we stress “and”: “nineteenth-century Homers AND the hexameter mania.” Nevertheless I wish to stress the conjunction, not only to make the line scan but to mark a link between Victorian versions of Homer and the development of English hexameter. Instead of stressing what is lost in translation, we might see what is gained through metrical translation as a reversal of the relation between form and content: what is translated is not a “content” but the performance of form itself, and the possibility of its transformation.

These Victorian hexameter translations have been mostly forgotten, amidst the many versions of Homer circulating in England by the end of the nineteenth century.8 However in The Translator’s Invisibility, Lawrence Venuti argues that the Arnoldian approach to translating Homer has continued well into the twentieth century, demonstrating “Arnold’s continuing power in Anglo-American literary culture” and “the dominant tradition of English-language translation, fluent domestication.”9 Arnold’s “domesticating method,” as Venuti defines it, was “to produce familiar, fluent verse that respected bourgeois moral values” for the English nation, in contrast to the “foreignizing method” of Newman, who translated Homer into an archaic ballad form that Venuti associates with a more popular and democratic concept of English culture (130–31). Venuti’s chapter on “Nation” focuses on these different ideologies of translation in the Arnold-Newman debate and, according to Venuti, Arnold “won”: the idea of Homer in Arnold’s lectures served to consolidate a national ideal, enforced by a strategy of translation that sought to domesticate the foreign text. But while Venuti argues for the importance of making the material and historical conditions of translation visible, the material and historical form of hexameter translations remains invisible in his argument; he does not read the form itself to make its strangeness visible. Within the context of nineteenth-century hexameter debates it is difficult to read Arnold’s call for hexameter translations simply as a triumph of fluent domestication. Although Arnold admired the rapid flow of Homer, the work of translation that Arnold prescribed to invent “such an instrument as the hexameter” was slow, laborious, and strange; even while familiarizing the English ear, hexameter was also an instrument of defamiliarization, and anything but transparent.

TRUE TO THE ANCIENT FLOW

The viability of writing verse in classical meters was an obsession among poets and prosodists throughout the Victorian period, and what obsessed them most of all was the revival of hexameter. In addition to counting the number of accents and syllables in a line (as in the tradition of English accentual-syllabic verse), they tried to measure the length or duration of syllables by following the rules of quantity in classical Greek and Latin poetry. Not since the sixteenth century had there been as much interest in quantitative meter as a model for reading and writing English poetry. Elizabethan verse in classical meters was influenced by Latin prosody in grammar schools, where schoolboys learned to scan by marking the long and short syllables of the Latin text, dividing the lines into feet, and then reading this aloud according to the rules they had memorized. As Derek Attridge argues in Well-Weighed Syllables, such techniques of scansion emphasized the apprehension of durational patterns through the written rather than the spoken word, and led to a conception of meter removed from the rhythms of the vernacular.10 Elizabethan experiments in quantitative verse proved a failure, as iambic versification became increasingly normalized and indeed naturalized for English poetry as it was written, heard, and spoken. By the nineteenth century, however, poets were turning with renewed enthusiasm to experiments in classical meters, to explore alternatives to iambic pentameter and extend the idea of “English” verse in new directions.11

But if sixteenth-century quantitative experiments were attempts to classicize English verse by removing it from the rhythms of the vernacular, nineteenth-century experiments tried to naturalize classical verse by drawing it closer to the vernacular: its meter was scanned in written form, yet its rhythm was supposed to “flow” like the spoken word. In contrast to Elizabethan quantitative verse modeled primarily on Latin, Victorian prosody increasingly turned to ancient Greek as its ideal, as schoolboys were taught to memorize Homer in particular, and to admire the rhythmic flow of Homeric hexameter through oral recitation.12 Learning to read Homer out loud led to various controversies about the proper pronunciation of Greek, and in particular the problem of pronouncing quantitative verse, as it was easy to confuse, or conflate, Greek quantities with English accents. Eager to revive a dead language no longer spoken, classical scholars in England became preoccupied with the sound of Greek and although no one really knew how it sounded, they devised elaborate systems of accentuation in order to imagine its resonance.

Trying to understand the two languages—Greek and English, ancient and modern, dead and living—in relation to each other was a preoccupation for poets throughout the nineteenth century as well, already in the early work of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Reviewing a scholarly pamphlet, “On the Prosodies of the Greek and Latin Languages,” Coleridge agreed with the concern of classical scholars that “we indeed of this country read the Greek and Latin as we read the English” and thereby cause “metrical havoc.”13 Because English accentuation tended to distort the length of syllables in classical verse, it caused mispronunciation in the very attempt to pronounce Greek and Latin. Coleridge’s recommendation was “to reform this barbarous mode of reading, and to teach the way of giving accent, so as to be not destructive of quantity,” and he envisioned an educational system where recitation of Greek poetry would teach better pronunciation of English as well: “To read regularly a few lines of some Greek … would form … an amusing and useful exercise for the higher classes in our great school. The young men would at least acquire by it the habit of distinct pronunciation, so important in public speaking, but which so few of our public speakers possess.” Like many nineteenth-century men of letters, Coleridge (who had acquired a good “ear” for Greek during his early education at Christ’s Hospital) believed that reading Homer would create better English speakers, and perhaps even great orators.

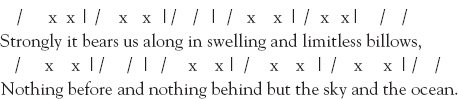

Homeric hexameter thus emerged as an idea of sound, circulating in a written form that readers were taught to hear. In his various meditations on hexameter—in notebooks, letters, reviews, and his own metrical experiments—Coleridge tried to reconstruct the sound of quantitative verse in Greek, and to describe its audible effect in English.14 His poetic imitation of hexameter, “Described and Exemplified,” was one attempt to recreate the experience of reading Homer’s Greek:

Here the Homeric epithet for “the many-sounding sea” is recycled to describe and exemplify the movement of the verse itself, as “strongly it bears us along” in the rise and fall of wave after wave.15 We are carried by this rhythmic cadence to an infinite horizon of sound, “nothing before and nothing behind” except the “limitless billows” of hexameter lines. Coleridge represented hexameter as a force of nature in another imitation of classical meter as well, an elegiac couplet (alternating lines in dactylic hexameter and pentameter):

Coleridge taught his reader to read the flow of the verse as a rising hexameter and a falling pentameter, seeming to overflow the caesura in the first line, while the second line pauses at the caesura in a momentary interruption of the melody. Like the endless waves of the sea or a fountain forever ascending, hexameter is associated with the perpetual flow of Homer’s verse: a metrical lesson taught to generation after generation of Victorian schoolboys.

Coleridge’s lesson was learned by his nephew Henry Nelson Coleridge, who turned it into a principle of pedagogy in Introduction to the Study of the Greek Classic Poets, Designed Principally for the Use of Young Persons at School and College (1830). This popular schoolbook explained that young persons must be taught to read hexameter according to the rules, but they must also feel the rhythm that moves beneath and beyond the rules of the meter: “The verse of the Iliad seems the musical efflux of a minstrel whose unpremeditated songs are borne on the breeze-like tunings of a lyre. It is idle to attempt to lay down rules for the rhythm of the Iliad; those who have read the poem, know and feel, though cannot understand or imitate, its incomparable melody.”16 The fluency of this rhythm influenced the reading of hexameter throughout the century as an idealized and naturalized metrical form, frequently compared to the influx of water in streams and oceans or the efflux of air in breezes and human breath. Indeed, because Homeric hexameter was no longer spoken it could be imagined by both of the Coleridges and their Victorian successors as more resonant, more melodious, and more flowing than their own spoken language. The “incomparable melody” of Greek could only be felt, and never fully heard or understood in English, let alone imitated.

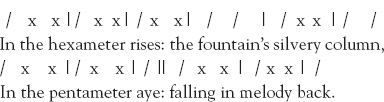

Nevertheless various efforts to imitate hexameter were collected in an influential 1847 anthology, English Hexameter Translations, prefaced by elegiac couplets that asked the “lover of Song” to read these hexameters as if they appealed naturally to the listening ear:

In a curious reversal of vernacular and classical languages, the contemporary language that is spoken is figured as “lines” to be read, while the ancient language that is written is figured as a song to be heard: the “ancient flow” of hexameters conveys “the tones of the heart” more musically than the “lines of our rhymesters.” Rather than attending to the passing “fashions of speech” inscribed in the rhyming lines of English verse, the reader’s “ear” and “voice” must be attuned to a song that flows over time in another kind of line: the meter of this elegiac couplet, as it alternates between full and abbreviated lines in dactylic hexameter. The (over)flow of this rhythm is measured by the enjambment between the first and second line (“found it / true”) and in the reiteration of “true” across the caesura in the second line: “true to the ancient flow, // true to the tones of the heart.” And in the fourth line, we cross the caesura again in a musical movement from “ear” to “voice,” as if the melody survives uninterrupted in our hearing and then our voicing of the meter: “Lend us thy listening ear; // lend us thy favouring voice.”

One reader who did indeed lend his “listening ear” and his “favouring voice” to these imitations was Matthew Arnold. In his lectures, On Translating Homer, delivered a decade after the publication of English Hexameter Translations, he mentioned this book as example of what might be achieved in hexameter. “The most successful attempt hitherto made at rendering Homer into English, the attempt in which Homer’s general effect has been best retained, is an attempt made in the hexameter measure,” Arnold wrote in praise of one of the translators, “the accomplished Provost of Eton, Dr. Hawtrey” (149). Hawtrey had published a passage from the Iliad in a section of English Hexameter Translations, entitled “From Homer,” where the poet is introduced as “Time-Honour’d Bard” who “roll’st into ages to come the sounding strain of the Epos / Here may its echo revive, here on Cimmerian shores!”18 This introductory verse, followed by Hawtrey’s translation, implied that English hexameters are at best an echo of the original: when the waves of Homeric hexameter wash up on English shores, what we hear is not Homer’s “sounding strain” but its resonance: the revival of an echo as an effect of reading.

Arnold’s ear was attuned to this difference. While he praised Hawtrey’s Homer because “it reproduces for me the original effect of Homer: it is the best, and it is in hexameters” (150), he did not claim that Hawtrey had actually reproduced the original sound of Homer; rather, the Provost of Eton had reproduced the “effect” of Homer, the experience of reading Greek as it was taught at schools like Eton (or in Arnold’s case, Rugby) and at the universities. In calling for more hexameter translations of Homer, Arnold was not advocating a revival of this meter as it was heard in ancient Greece, but remembering how it was read in modern England. Arnold made this point emphatically throughout his lectures On Translating Homer, which began by acknowledging that “we cannot possibly tell how the Iliad affected its natural hearers” (98), and insisting repeatedly that the task of the translator was not to recreate the sound of Homeric hexameter but rather to imitate its effect upon the reader: “All we are here concerned with is the imitation, by the English hexameter, of the ancient hexameter in its effect upon us moderns” (195) and again, “the modern hexameter is merely an attempt to imitate the effect of the ancient hexameter, as read by us moderns” (198). Turning himself into an example of “us moderns,” Arnold famously went on to define the four features of Homer’s “grand style” in terms of “what is the general effect which Homer makes upon me,—that of a most rapidly moving poet, that of a poet most plain and direct in his style, that of a poet most plain and direct in his ideas, that of a poet eminently noble” (119).

Arnold’s definition of the “grand style”—hovering between prescription (how Homer should impress everyone) and description (the impression of Homer “upon me”)—was an early articulation of his aesthetic theory, increasingly concerned with poetry’s effects on its audience.19 What the translator had to recreate was the “effect” of the Greek text, to show how “Homer’s rapidity is a flowing rapidity,” as Arnold repeatedly insisted (136): “Homer’s movement, I have said again and again, is a flowing, rapid movement…. In reading Homer you never lose the sense of flowing and abounding ease” (145). But he understood this movement to be produced by the modern mind in reading Homer, and reproduced by the translator to achieve a similar rapidity in English. For this reason he criticized translations that seemed antiquated, such as a recent version by Charles Ichabod Wright in the Miltonic manner of Cowper, “entirely alien to the flowing rapidity of Homer,” and a version by William Sotheby in “Pope’s literary artificial manner” (103), or antiquarian, such as the “slip-shod” or “jog-trot and humdrum” ballad-manner in versions by William Maginn and, most notoriously Francis Newman (124, 128). Moving either too slow or too fast, these translations had not found a way to recreate the flowing ease of Homer as experienced by a modern reader in modern times.

To be “true to the ancient flow” English translators would have to modernize hexameter, perhaps along the lines of a modern poet like Arthur Hugh Clough, who had left classical scholarship at Oxford and turned to poetry and politics. According to Arnold, “Mr. Clough’s hexameters are excessively, needlessly rough; still, owing to the native rapidity of this measure … his composition produces a sense in the reader which Homer’s composition also produces, and which Homer’s translator ought to reproduce” (151). Clough had made hexameter “current” in both senses: a contemporary, rapid form that reproduced the effect of ancient Greek on the English reader. Although Clough’s meter was “rough” at times, interrupting the flow of the reading, Arnold considered his poetry the best example of hexameter in English. He finished the last of his lectures with a eulogy for his friend, whose hexameters “come back now to my ear with the true Homeric ring” (216): not the original sound, but a resounding echo that reproduced “a sense in the reader which Homer’s composition also produces.”

Of course the poet who had contributed most to the currency of hexameter in the nineteenth century was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, but Arnold went out of his way in his lectures to emphasize that the translator “must not follow the model offered by Mr. Longfellow in his pleasing and popular poem of Evangeline” (151). He considered these hexameters “much too dactylic,” a debasement of English hexameter by an American poet who had been parodied in the press as “Professor Long-and-short-fellow.”20 Arnold was ambivalent about the success of Evangeline, simultaneously admiring and criticizing its popular appeal: “If a version of the Iliad in English hexameters were made by a poet who, like Mr. Longfellow, has that indefinable quality which renders him popular … it would have great success among the general public,” he admitted, but not without qualification: “Yet a version of Homer in hexameters of the Evangeline type would not satisfy the judicious, nor is the definite establishment of this type to be desired” (202). Arnold as much as warned Longfellow not to take up the task of translating Homer: “One would regret that Mr. Longfellow should, even to popularize the hexameter, give the immense labour required for a translation of Homer, when one could not wish his work to stand.” An American Homer would and should not influence the future of English hexameters, or so Arnold believed.

In addition to marking a distinction between English and American hexameters, Arnold was anxious to distinguish English from German hexameters as well. Although English poets had been influenced by German hexameter experiments, and although German poets might have been more successful in achieving the effects of quantitative verse, Arnold insisted that the English language was better suited to recreating the “rapidity” of Homer. Even the most successful translator of Homer in nineteenth-century Germany was at a disadvantage, according to Arnold, because that language seemed so slow and ponderous in comparison to English: “In Voss’s well-known translation of Homer, it is precisely the qualities of his German language itself, something heavy and trailing both in the structure of its sentences and in the words of which it is composed, which prevent his translation, in spite of the hexameters, in spite of the fidelity, from creating in us the impression created by the Greek” (101). Arnold believed that the transformation of quantitative into accentual hexameter by English poets was unique to England, because “by this hexameter the English ear, the genius of the English language, have, in their own way, adopted, have translated for themselves the Homeric hexameter” (196). The native genius of the English language could be made manifest by translating hexameter into a form quite distinct from other languages, both ancient and modern.

After surveying the long history of translating Homer in various English verse forms (fourteen-syllable lines, blank verse, heroic couplets, Spenserian stanzas, ballad measure), Arnold therefore predicted that “the task of translating Homer into English verse both will be re-attempted, and may be re-attempted successfully” (167) by “a poetical translator so gifted and so trained” (168) as to produce perfect hexameters in English. More than one meter among many, hexameter was invoked by Arnold as a metrical imaginary, an ideal form that he tried to illustrate with his own translation of selected passages from Homer into hexameter. However he was quick to admit that his attempts—“somewhat too strenuous and severe, by comparison with that lovely ease” of Homer (167)—fell short of his own ideal. In his rather stilted translations, he found it difficult to follow “the fundamental rule for English hexameters,—that they be such as to read themselves without necessitating, on the reader’s part, any non-natural putting-on or taking-off of accent” (197). It would take “some man of genius” (202) to find a middle ground between the rough hexameters of Clough and the too-smooth dactyls of Professor Long-and-short-fellow, so instead of ending with his own translations, Arnold’s lectures were ultimately addressed to “the future translator of Homer” (213). “It is for the future translator that one must work” (215), he concluded: someone who could mediate between ancient quantities and modern accents to create hexameters that would naturally “read themselves.” Like the second coming, “our old friend, the coming translator of Homer” (170) might redeem the confusion of the present time by making hexameter into an English form, and a perfect form of Englishness.

NESTOR’S ELOQUENCE

Not long after the publication of Arnold’s lectures, hexameter translations of Homer sprang up like native plants in English soil. Among the scholarly poets and poetic scholars who turned to translating Homer was C. B. Cayley. In an article entitled “Remarks and Experiments On English Hexameters” (1862), Cayley agreed with Arnold that hexameter has “pleased cultivated nations through many generations” and might be cultivated to grow naturally in England as well: “each literature has its own accustomed measures: but from time to time many such are found to bear transplantation into foreign languages.”21 Since hexameters had been successfully transplanted from Greek to Latin verse, Cayley wondered, “is there not a chance of their being adapted to a language of intermediate cadence, like the English, which has many words accented after the Greek model … and many, of course, after the Latin model?” (75). He believed the English language, being composite, could combine different accentual structures with some sense of duration in syllables; he pointed out the persistence of primary and secondary accents in English and, while “the Greeks no doubt, had elocutional habits more lively than ours” (79), he argued that it was indeed possible for English poets to recreate some of the complex accents and cadences of classical hexameter, especially around the caesura: “as in English we certainly have weak syllables and primary accents and secondary, so in an hexameter formed on classical principles, one caesura, at least—and if possible, one of the principal caesuras should be preceded by a weak syllable, or at worst by a secondary accent, or if there is such a thing in English, by a circumflexed syllable” (78). Even if quantities of syllables (“circumflexed” or otherwise) could not be consistently measured in English, nevertheless English hexameters could achieve a musical cadence by manipulating stronger and weaker syllables.

Rallying around Arnold’s call for hexameters, Cayley offered a more detailed explanation of how this meter might be made to work in English. He began his article by disclaiming what “is commonly said that modern versification depends on accent only, as the ancient depended on quantity,” and proclaiming instead that “we cannot banish all the feeling of time even from the modern cadences” (67). And to illustrate his “suggested method in hexameters” (84), he ended his article with a sample translation from Book I of the Iliad: a speech by made Nestor, who exercises authority over generations of heroes through the power of persuasive speech. The role of Nestor in Homeric epic is to weigh his words carefully and teach others to do the same, as he says in Cayley’s English translation: “Yet did they meditate my words, they obey’d my counsels” (85). This line is also carefully weighed to teach Cayley’s method in hexameters, with a caesura after “meditate” (preceded by a weak syllable, as Cayley prescribed) and another caesura after “words,” to create a pause for meditation on the cadence of these words. Placed at the end of Cayley’s long explanation of hexameters, his translation turns the content of Nestor’s speech into a performance of its form, as if Cayley were instructing other translators to meditate on this example and (if they obey’d his counsels) turn it into a model for English hexameters.

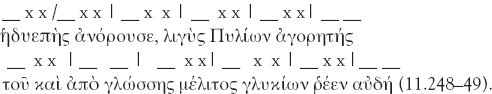

As Homer’s veteran orator and master of performative speech, Nestor was a strategic choice for such a self-reflexive rhetorical performance. In The Language of Heroes, Richard Martin shows how Nestor is a heroic performer of words who has mastered the genre of memory speeches, recalling the past in order to authorize himself in the present.22 Nestor’s ability to remember and remind is embedded in the etymology of his name (connected to mnestis, memory), and closely linked to the power of epic narrative (inspired by Mnemosyne, the muse of memory); indeed the Homeric epithet used for Nestor “refers to divine speech within Greek archaic poetry,” according to Martin: heduepes, “having sweet words” (102). Nestor’s speech in Book I of the Iliad is introduced by two lines in Greek that describe how “sweet-speaking Nestor, the clear-voiced orator from Pylos arose, from whose tongue flowed speech sweeter than honey”:

Nestor is a “sweet” and “clear” speaker, whose words stream (ῥέεν, from the verb “to flow”) like honey from his tongue. This description of Nestor’s eloquence appealed to many nineteenth-century readers, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge who meditated on “the flowing Line of the epic” in one of his notebooks by quoting the same line about Nestor: “ ‘Pήμα. ῥέω, fluo. Stream of words. Flow of eloquence. Hence perhaps the German, ich rede, the old English, I areed, & our Read it to me, doubtless first used by those who could not read. = Make it flow for me. τοῦ χαὶ ἀπὸ γλώσσης μέλιτος γλυχίων ῥέεν αὐδή.”23 Coleridge associated the ancient flow of Homeric epic with Nestor’s flowing speech, and (by speculative etymologizing) used the example of Nestor to imagine how a literary culture might be formed around this idea of an oral tradition.

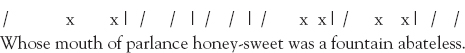

Cayley had a similar purpose in ending his article with the example of Nestor, as the embodiment of an oral tradition perpetuated in written form; through Nestor’s stream of words, readers might be taught to “hear” the flow of hexameters in English. For his complete version of the Iliad, published in 1877, Cayley framed his earlier translation of Nestor’s speech with a description of “Softspoken Nestor, Pylos’s clear-toned haranguer, / Whose mouth of parlance honey-sweet was a fountain abateless.”24 The adjectives “soft-spoken” and “clear-toned” used to describe Nestor’s address to his audience might also serve to address the reader of this translation, in accents softly spoken and quantities clear in tone: a combination of accentual and quantitative verse, with primary and secondary accents and carefully-timed caesuras, as prescribed by Cayley in his article. But it is difficult to scan this line as hexameter, since by English pronunciation it falls into five feet:

Only if we scan “soft-spoken Nestor” rather awkwardly into spondees (lengthening the vowels because they are followed by double consonants, according to classical rules of quantity) can we prolong the line into hexameter. And although the next line does fall into six feet, the tendency for an English reader to start scanning in iambs must be overruled by stressing (again rather awkwardly) the long vowel in the first syllable to produce a dactyl:

Although Cayley’s hexameters did not exactly “read themselves” as Arnold might have wished, nevertheless they found in the “parlance honey-sweet” of Nestor a “fountain abateless” of inspiration for the English translator: the orator as figure for the perfection of metrical translation, and embodiment of its persuasive effects.

Indeed, when Cayley finished his translation of Homer, it was dedicated to one of the great orators of the Victorian period: The Iliad of Homer, Homometrically Translated, With Permission Dedicated to the Right Honourable Gladstone (1877). With this dedication, Cayley associated the eloquence of Nestor and other Homeric orators with William Ewart Gladstone, an eloquent politician, British prime minister, and scholar of Homer. In his 1857 essay “On the Place of Homer in Classical Education and Historical Inquiry,” Gladstone had emphasized the need for boys and men to learn about “the faculty of high oratory” by reading Homer,25 and in Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age (1858) Gladstone wrote at length about the variety of orators and orations in Homer, in order to demonstrate “how and why it was, that the great Bard of that time has also placed himself in the foremost rank of oratory for all time.”26 In Achilles and Odysseus he found “specimens of transcendent eloquence which have never been surpassed” (107), and he mentioned Nestor as another specimen: “Then we have Nestor the soft and silvery, whose tones of happy and benevolent egotism flowed sweeter than a stream of honey” (105). This sentence is virtually a translation of Homer’s description of Nestor: the movement of the poetry is transferred to Gladstone’s dactylic prose, whose “tones” come close to recreating the effects of Homeric hexameter. The same lines from Homer are paraphrased by Gladstone again later in his Studies on Homer, when he alludes to the famous description that “the Poet has given of the elocution of Nestor”: “To Nestor (Il. I. 248,9) he seems to assign a soft continuous flow indefinitely prolonged” (III, 240–341). Here too the “continuous flow” of Nestor, “indefinitely prolonged” by Gladstone, seems to have influenced his own style of writing.

Gladstone’s fascination with the power of Homeric oratory was reflected not only in his writing, but even more in his speaking. He had been quick to learn Greek as a schoolboy at Eton, where his knack for versifying and speechifying on classical models drew the attention of Dr. Hawtrey himself (who later became headmaster of Eton and the translator of Homer, singled out by Arnold for praise). Richard Shannon’s biography notes that Gladstone’s classical education at Eton was important in “providing him with a forum for expression in speech and print,” and in giving him a sense of vocation through studies in Homer that inspired him at the university and for the rest of his life. His vocation as a politician was quite literally the discovery of a voice for Gladstone, who was celebrated as a great debator at Oxford and throughout his long political career. His contemporaries remarked that he had “a very fine voice” and “the deepest-toned voice I ever heard,”27 and Carlyle famously called Gladstone “the man with immeasurable power of vocables.”28 But it was through Homer in particular that Gladstone made this claim to voice, as he wrote in a letter: “Most of my time is taken up with Homer and Homeric literature, in which I am immersed with great delight up to my ears.”29 He represented his virtuosity in speaking as an effect of reading Homer, an appeal to the English ear that he had learned because of his immersion in ancient Greek. He engaged in conversations about Homer at every opportunity, including more than one occasion with Tennyson who did his best to find Gladstone “very pleasant and very interesting … even when he discoursed on Homer, where most people think him a little hobby-horsical.”30

It was not surprising, then, that Cayley’s translation associated Gladstone with Homer (and perhaps with the long-winded Nestor in particular). The fluency of Gladstone’s speeches was another way to imagine the cadences of Homeric epic in English, reviving the ancient flow of Homer in a modern tongue. Like Nestor he was a heroic performer of words, recalling the past in order to speak to the present and perhaps even to the future, as Gladstone was chosen by Edison to record his voice on wax cylinder. When Gladstone’s contemporaries heard this recording they were amazed by “the marvellous carrying-power of the most eloquent voice of our time … with all its compass of persuasive intonation,” and indeed from the 1888 recording it is possible to imagine the smooth metrical flow of his speech, as Gladstone almost seems to speak in dactyls:

I lament to say that the voice which I transmit to you is only the relic of an organ, the employment of which has been overstrained. Yet I offer you as much as I possess and so much as old age has left me, with the utmost satisfaction as being, at least, a testimony to the instruction and delight that I have received from your marvelous invention.31

In the recording this voice is indeed a relic of a past age, “overstrained” by old age and difficult to hear. Yet this voice also speaks to future ages, by giving testimony to the means of its own transmission through a “marvelous invention” that would preserve it for posterity, not unlike the marvelous invention of English hexameter that would preserve the voice of Homeric epic in Victorian England. Gladstone was the modern version of an ancient orator, who could be heard (and read) as the voice of his age, especially in retrospect. In the monumentalizing biography published in 1903 by John Morley, for example, the life of Gladstone is narrated in an epic strain (sometimes even in dactylic rhythm, like Gladstone’s prose) that recalls the beginning of Homer’s Iliad or Odyssey: “how can we tell the story of his works and days without reference … to the course of events, over whose unrolling he presided, and out of which he made history?”32 Because he made history through his speeches in particular, Gladstone gave shape to the unruly course of events during “an agitated and expectant age” according to Morley (4), who presented Gladstone as heroic representative figure for the Victorian period and the very embodiment of its historical rhythm.

Arnold also associated Gladstone with Homer, especially at a time when the place of Homer in the classics curriculum and the purpose of Greek studies in general were being debated at schools and universities.33 In his lecture “On the Modern Element in Literature” Arnold referred to Gladstone as “a distinguished person, who has lately been occupying himself with Homer” (31) and his lectures On Translating Homer followed on the heel of Gladstone’s Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age. For both men this turn to Homer was a response to times of rapid change in Victorian England, and an attempt to shape the temporal experience of modernity. Gladstone was not so sure, however, that hexameter would be the best modern form for translating Homer or that it could serve to carry the reader into the future of English poetry. He wrote a letter to Arnold after his lectures, confessing “when asked to believe that Homer can … be rendered into English hexameters, I stop short.”34 Gladstone’s experiments in translating Homer were mostly trochaic, in alternating tetrameter and trimeter lines that slowed down the rapid movement of Homer as Arnold imagined it. In contrast to his flowing eloquence as an orator, Gladstone’s translations moved in stops and starts that fell short of Homeric hexameter. Despite the dedication of Cayley’s Homer “homometrically translated” to Gladstone, Gladstone’s own version of Homer did not quite achieve this epic effect: Gladstone was famous for his prose, not his prosody.35

Even among the prosodists there was no clear consensus about the sound of hexameters in Victorian England. Translators who tried to write in English hexameter, as prescribed by Arnold, struggled and failed. In the preface to Homer’s Iliad, Translated from the Original Greek into English Hexameters, published in 1865, the translator Edwin Simcox wrote apologetically about his attempt to “place before the English reader a close, and, as it were, a photographic view of the poem, so far as the English language, in his humble hands, can produce this result; but it must be remembered that the Greek surpasses the English, in sound, as far as the organ does the pianoforte.”36 According to Simcox, the best a translator could give his reader was a “photographic view” derived from a negative image of the original: a graphic representation of sound in writing that faded away (like notes struck on a pianoforte) and could not be sustained (like the tones played on an organ). Rather than prolonging the duration of syllables, Simcox depended on the percussive effects of accentual verse, as performed in his translation of Homer’s description of Nestor:

As a self-reflexive performance of metrical translation, these lines were skillfully arranged by Simcox into dactylic hexameter, but without trying to recreate classical quantities as Cayley had recommended. Simcox readily substituted trochees for spondees, allowing the second syllable of a foot to be read simply as an unaccentuated syllable, and the caesuras in the first line (after “Nestor arose”) and the second line (after “skilful tongue”) allowed the hexameters to be read almost as double trimeters in English. Thus the words that “fell” from Nestor’s tongue also served to demonstrate the cadence of English hexameters, falling away from the sound of Greek.

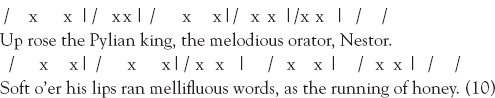

Other translations attempted in response to Arnold’s call for hexameters included: The Iliad of Homer in English Hexameter Verse, by J. Henry Dart (1865); Homer’s Iliad, Translated into English Hexameters, by James Inglis Cochrane (1867); and The Iliad of Homer, Translated into English Accentuated Hexameters, by John F. W. Herschel (1866). Dart had previously published the first half of his translation in 1862, praised by Arnold as a “meritorious version” but also criticized for the “blemish” of forcing accents; according to Arnold, his rule that hexameters must “read themselves” in English was occasionally violated by Dart.37 When Dart completed his translations three years later, he agreed with Arnold that certain kinds of accentuation (especially the Greek pronunciation of proper names) might be “unpleasing to an English ear” and that “further consideration, aided by the light of criticism” had prompted him to eliminate this blemish from his translation.38 But in final consideration of “the vexed question of metre,” Dart saw “no reason to regret having selected the Hexameter,” as he believed along with Arnold that “in it, and in it alone, is it possible … to combine adequate fidelity to the original, with that vigor and rapidity of movement.” He further argued, like Arnold, that “very many of those who now entertain a sense of dislike to the metre, would feel differently if their ears were but habituated to its use” (vii–viii). An apt example of Dart’s approach to metrical translation is, again, the description of Nestor:

Dart’s interest in recreating Homer’s “rapidity of movement” is exemplified in the verbs “ran” and “running” (his translation of the Greek verb “to flow”), and in the momentum of uninterrupted dactyls, moving almost too rapidly for Arnold’s taste: Dart’s version came close to the relentless dactyls of Longfellow, depending perhaps too much on the American poet for the habituation of the English ear to the use of hexameter.

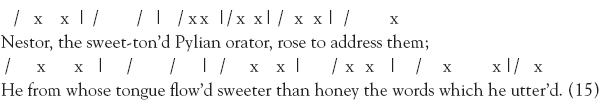

The translation of the Iliad by Cochrane also turned to foreign models in the effort to define English hexameter. Like other translators, he used the preface to justify his method of translation, explaining that “he prepared himself for the task by translating from the German ten or twelve thousand verses; for, although he was always of opinion that the measure was quite as well adapted as any other to the English language, yet, there were so many conflicting opinions on the subject, that he had in a considerable degree to grope his way, and ascertain for himself what the English language was capable of.”39 Cochrane emphasized that poets were still looking for a clear articulation of English metrical law: “Every hexameter writer had his own particular theory, and there were no definite and acknowledged rules to guide one.” But this irregularity proved in some respects an advantage for Cochrane, who combined different theories of hexameter to achieve greater variation in his hexameter lines. Thus, in his translation of Nestor, we find a combination of accentual and quantitative verse:

While “sweet-ton’d” and “tongue flow’d” can be scanned as spondees according to classical rules of quantity, the final feet of both lines are closer to trochees according to the principles of English accentuation. Indeed Cochrane suggested that Nestor’s speech is heard in accents, as his translation went on to describe Nestor, “counseling wisely, in these kind accents he spake, and address’d them.” The utterance of Nestor could thus be read simultaneously in quantities and accents, but without a “particular theory” or “acknowledged rules” for integrating the two systems of versification as Cayley had proposed.

Another translator who embraced accents even more fully was Herschel, as announced by the title of his Homer, Translated in English Accentuated Hexameters. The translator’s preface (again a strategic piece of rhetoric) defended Herschel’s decision to translate quantitative into accentual verse, and appealed to readers to give it a “fair hearing”:

The Hexameter metre is on its trial in this country. It is therefore entitled at all events to a fair hearing. It may at least claim to be read as any other of our received metres is read; with no deliberate intention to caricature it, or to spoil it in the reading: without sing-song or affectation, and according to the ordinary usages of English pronunciation. So tried, if it fail to please and to make its way, it stands condemned. But in the perusal of so long a poem it must be borne in mind, in common candour, that all our ordinary forms of verse have a certain elasticity,—admit a certain latitude of accommodation between the accent proper to the verse—its dead form—and that which constitutes its living spirit and interprets its melody to the hearer.40

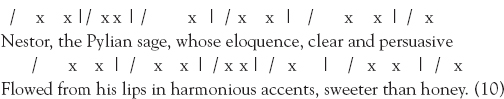

Herschel asked readers to conflate legal and aesthetic judgment—to give this trial of hexameters a “fair hearing” and also in “hearing” to find them “fair”—and in their exercise of English metrical law, to decide by the rules “in this country” and according to “usages of English pronunciation.” However he added some special pleading: the readers who judged his translation would have to be sufficiently lenient to “admit a certain latitude of accommodation” between the “dead form” of the verse and its “living spirit.” To breathe new life into Homeric hexameter and revive its spirit would take an act of inspiration, a translator who could “interpret the melody to the hearer” by giving it a living form. Herschel was inspired to interpret the melody of Nestor’s speech as “harmonious accents” in his translation:

Rather than attempting quantitative verse (as in Cayley’s “clear-toned” or Cochrane’s “sweet-ton’d” versions of Nestor), Herschel presented the speech of Nestor in accentuated hexameter, freely alternating dactyls and trochees. To emphasize the harmonious flow of his translation, the verb “to flow” has been placed at the beginning of a line, and the placement of caesuras at variable points within each line creates a sense of overflow rather than interruption. Thus Nestor is made to speak, “clear and persuasive,” in English accents.

As Poet Laureate, Tennyson did not think much of the hexameter experiments inspired by Arnold’s Lectures on Translating Homer. In 1863 Tennyson criticized attempts by Herschel and others to revive a dead form and interpret its melody: “Some, and among these one at least of our best and greatest, have endeavoured to give us the Iliad in English hexameters, and by what appears to me their failure, have gone far to prove the impossibility of the task.”41 To go even further in proving the impossibility of the task, Tennyson’s skeptical headnote introduced a parody of hexameter, written by himself in elegiac couplets and entitled, “On Translations of Homer. Hexameters and Pentameters”:

Tennyson’s verse is deliberately awkward, prompting us to read “these lame hexameters” not only as a description of Homeric translations but as a performance of its own mock-versification. The parody begins lamely with a spondee, ironically contrasting “these lame” feet in English with the “strong-winged music of Homer,” getting stronger in dactyls but disrupted by the dissonance in the following line: “No, but a most burlesque, barbarous experiment.” The harsh sound of plosives in “but,” “burlesque,” and “barbarous” is amplified into the “harsher sound” of croaking, in a line that is made more difficult to pronounce by forcing the accentuation of an unaccented syllable; “When did a frog coarser croak?” The penultimate line makes a mockery of German hexameters by lengthening the feet into ponderous spondees and (as if to illustrate the failure of the meter) falling short of a beat at the end: what “daring Germany gave” requires an extra syllable and is nothing but an empty form.

Thus any attempt to recreate the music of Homer in English hexameters was made to sound like a “barbarous experiment,” a strenuous combination of stresses repeated twice by Tennyson for comic effect, in the second line and again at the end. To add insult to injury, the scansion of the last phrase is so ridiculous that it sounds almost like “barbarous hexameters” are written by “barbarous hexamateurs.” Translators of Homer, we might conclude, are amateur poets who threatened to turn English into the language of barbarians, according to the Greek etymology of the word: in trying to recreate Greek hexameters, English syllables are reduced to the meaningless iteration of “barbar … barbar,” like the stuttering repetition of “barbarous” in the final line. Furthermore, the caesura between “barbarous experiment // barbarous hexameters” draws another double bar, disrupting the flow of Homeric rhythm. Instead of melodious song, we hear harsher sounds that are measured by their own interruption and disruption. Derived from a dead language that is neither heard nor spoken by the Muses in England, these hexameters are abstracted into a series of metrical bars that barbarize English and make it sound foreign.

In his History of English Prosody, Saintsbury’s diatribe against “the hexameter mania” came to a similar conclusion. Quoting Tennyson’s parody, he commented on the final line that “the syllables must be forced into improper pronunciation to make the quantities audible … you have to pronounce, in a quite unnatural way, ‘experimennnnnnt,’ ‘hexameterrrrr” (III.421). Of course the poetic success of Tennyson’s hexameters was measured precisely by that failure of pronunciation, but Saintsbury took Tennyson at his word. His chapter on “The Later English Hexameter” became a tirade against “English Quantity-Mongers” (411) and “classicalisers” (422) who introduced quantities difficult to measure or hear in English: “With the self-styled quantitative hexameter you must either have a new pronunciation, or a mere ruinous and arrhythmic heap of words,” Saintsbury concluded (400). He worried that the spoken language would be regulated (or rather, deregulated) by rules that make English unpronounceable: far from melodious, the ideal of Homeric rhythm might have the contrary effect of making English poetry “arrhythmic.” He therefore dismissed the prescription of classical rules for English hexameter as an experiment “reinforcing lack of ear” and “foredoomed to failure” (415).

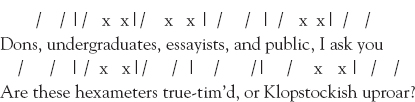

Cayley’s translation of Homer was singled out by Saintsbury as a particularly ruinous and arrhythmic heap of words. In a prefatory verse to his Iliad, Cayley had asked readers to listen carefully to the length of the syllables in his “homometric” hexameters, without simply counting the accents:

Although the pronunciation of these lines might seem odd at first, Cayley claimed his translation was nothing like the noisy German hexameters of Klopstock, but a more subtle appeal to the English ear in “true-tim’d” quantitative verse. Saintsbury made a mockery of Cayley’s “homometric” hexameters. To emphasize that scanning ancient Greek was not the same as reading English verse, Saintsbury tried to scan “dons, undergraduates” in Cayley’s couplet and pointed out the difficulty of pronouncing “underrrgraduayte” according to antiquated rules of quantity—an instructive academic exercise for dons and undergraduates, perhaps, but too artificial for English readers ready to graduate from pedantic metrical instruction. “Our business is with English,” Saintsbury insisted, “And I repeat that, in English, there are practically no metrical fictions, and that metre follows, though it may sometimes slightly force, pronunciation” (435).

But since, as Saintsbury conceded, pronunciation may (and even must) be forced by the meter “sometimes,” the new wave of hexameter translations in the wake of Arnold’s lectures tried to show how a metrical fiction might be naturalized and nationalized in English poetry. The next chapter in this metrical fiction was written by James Spedding, who argued that English hexameter should resist accent altogether.42 Arnold distanced himself from Spedding’s radical theories: in “Last Words” he worried that Spedding “proposes radically to subvert the constitution of this hexameter,” and instead Arnold proposed an approach to the form more conservative than Spedding, who “can comprehend revolution in this metre, but not reform” (197). Nevertheless by the end of the century, the revolution was well underway in the work of prosodists like William Johnson Stone and Robert Bridges, who were experimenting with quantitative hexameter to change the history of English versification and redefine English national meter. For example Stone’s pamphlet “On the Use of Classical Metres in English” (first published in 1899 and reprinted by Bridges) concluded that “accentuated verse” had become “too easy and too monotonous” and it was time to displace traditional blank verse with English verse in classical meters.43 To illustrate his theory of hexameter, Stone included his metrical translation of a passage from Homer’s Odyssey, beginning with the lines: “When they came to the fair-flowing river and to the places / Where stood pools in plenty prepared, and water abundant, / Gushed up, a cure for things manifold uncleanly …” These lines redirected the ancient flow of Homer into a “fair-flowing river” of verse that might cure, cleanse, and purify English poetry, and lead it to new places, perhaps in the next century.

Given the ongoing controversies about many possible forms of English hexameter, the Arnoldian legacy in metrical translation is (clearly) not as transparent a discourse as Venuti would claim. Even in the late twentieth century, in Rhyme’s Reason: A Guide to English Verse, John Hollander poses the problem of “putatively ‘quantitative’ dactylic hexameters” in a self-reflexive metrical performance that cannot answer its own question:

All such syllables arrang’d in the classical order

Can’t be audible to English ears that are tun’d to an accent

Mark’d by a pattern of stress, not by a quantitative scrawl.

As Hollander remarks on (and in) his poem, “these lines ‘scan’ only if we show that the pattern of ‘long’ and ‘short’ syllables falls into the classical ‘feet,’ or musical measures.”44 The inaudibility of this music makes classical hexameter a graphic effect rather than a vocal phenomenon, something seen and not heard, something read and not spoken. The difference between the poem in the eye and the poem in the ear is further explored in Vision and Resonance: Two Senses of Poetic Form, where Hollander devotes a chapter to experiments in quantitative meter as “a written code” haunted by our desire to hear it spoken. Looking beyond Elizabethan and Victorian experiments he discerns “the last ghost of quantitative hankering in English and American poetry” where “specters continue to appear” (70) to confuse our two senses of poetic form in a weird extrasensory perception, as if eyes could hear, and ears see. Hollander is skeptical (as Tennyson was, and Saintsbury too) of “the rebarbative air of the crank,” by which he means, “the quantitative crank, someone with Classical training who for complex reasons fancies he hears true quantity in English.”45

Yet for Arnold, hexameter was not rebarbative; to the contrary, it exemplified the civilizing measures of meter and a measured response to modern times. In the decade leading up to his lectures, Arnold had already been calling for such measures to give order to the chaos of the present. In the 1853 preface to his Poems he wrote that “commerce with the ancients” such as Homer would produce “in those who constantly practise it, a steadying and composing effect” (493), and he explained why he turned to Greek models in his own poems: “I seemed to myself to find the only sure guidance, the only solid footing, among the ancients” (494). Although in 1853 Arnold had not yet discovered a “steadying effect” and “solid footing” in the feet of dactylic hexameter, he took the next step as Professor of Poetry at Oxford, when he recommended hexameter translation for the future of English poetry and the orderly progression of English national culture. But even as Arnold called upon English hexameters as a form of and for national identification, he also detached meter from the traditions of versification identified as “English.” In The Powers of Distance, Anderson dedicates a chapter to “the range of forms of detachment to be found in Arnold’s work,” and in his critical writing from the 1850s and 1860s she observes a tendency toward “transcendence of constraining Englishness” and “an implicit ideal of cosmopolitan cultivation.”46 Hexameter, I would add, served as another form of detachment for Arnold, precisely because it could cultivated as a form. In “Culture and Anarchy” Arnold stressed the need for the English critic to “dwell much on foreign thought” and imagine how “the ideas of Europe steal gradually and amicably in, and mingle, though in infinitesimally small quantities at a time, with our own notions.”47 To define national identity through hexameter, Arnold also had to identify its international origins. Dwelling on the “foreign” thought of Homer, Arnold hoped that English forms could be transformed, “small quantities at a time,” by the ideas of Europe.

Contrary to his hopes, Arnold did not find consensus in England. In The Saturday Review he was accused of turning to foreign models to define “what is no English metre at all,” and readers were informed that Arnold’s hexameter translations were too strange, too distant, too remote from English utterance: “We hold it to be an utter mistake to try to reproduce the Greek hexameter … in a language like English.”48 The reviewer emphasized that Homer’s poetry was removed from speech even in Greek (“It was such Greek as nobody spoke,” [96]) and therefore its literary effect would always be an estrangement of the common language. Ultimately the article was an ad hominem attack on Arnold, as the embodiment of a professor alienated from the culture to which he wanted to give form. “The whole of the lectures are one constant I—I—I—Dass grosse ich reigns from one end to the other…. But it is not the mere number of I’s in Mr. Arnold’s lectures, it is the way in which ‘I’ always comes in—an authoritative, oracular way, something akin, we venture to guess, to ‘the grand style’ ” (96). Arnold’s oratory was conflated with the style of Homer, as a written form that was no longer spoken, and therefore must remain strange—perhaps even barbarous—to English audiences.

Arnold’s grand style was also lampooned by Charles Ichabod Wright (whose translation of Homer in blank verse had been curtly dismissed by Arnold’s lectures). In a pamphlet, Wright took revenge on the “Poetry-Professor” who had led a generation of translators into oblivion: “By the sanction of his name as the representative of Poetry, Professor Arnold has led on a number of men to pursue a phantom, in the hope that they might nationalize the Hexameter.” But Wright insisted, “our language is incapable of giving a naturalization to a metre in which rules of quantity are indispensable.”49 Wright believed that English could not be quantified, and so, in a wicked parody of bad hexameter verse, he imagined “the Professor” professing the rise and fall of his aspirations. “It perhaps may be allowed me to imagine the feelings which animated the Professor on the occasion, and to express them in verses somewhat akin to his own famed hexameters,” he wrote, ventriloquising Arnold:

‘Aye, surely are vanished the host of Translators of Homer!

My spear—it hath swept them like leaves of the forest in Autumn.

I only remain. My glory it never shall perish;

And Oxford shall triumph in me her redoubted Professor.’

Although Arnold seems to be reveling here in the triumph of his hexameter mania, none of the lines achieve full hexameter: they are missing a syllable in the first foot, turning the initial word of each line into an anacrusis or “upbeat” for the dactyls that follow. This is especially dramatic in “I only remain,” where the stress on “I” virtually reduces the pronoun to a metrical mark (not unlike the I—I—I of dass grosse ich). All that remains, in other words, is a failed metrical form.

Arnold’s triumph turns out to be failure, as Wright went on to imagine Arnold in despair: “Allow me once more to indulge my fancy in an imaginary soliloquy, reminding us of the reverses incident to humanity, from which even a Professor is not exempt.” In the following verse, Arnold apostrophizes his own hexameters as a dead and deadly form, unable to reanimate the poetry of Homer:

O cursed Hexameters—ye, upon whom I once counted

To wake up immortal, unique Translator of Homer,

I would ye had never been cherished and nursed in my bosom!

Ye vipers, ye sting me! Disgraced is the chair that I sit in;

And Oxford laments that her Muses have lost their protector.

In the transition from the first verse (celebratory) to the second verse (elegiac), Arnold seemed to suffer the “reverses” of poetic fate: in the attempt to re-verse the relationship between form and content, to find content in the performance of the form itself, his versification proved a failure.

Nevertheless if we linger long enough in this dead end of Victorian prosody, we might see how the pursuit of a phantom—the revival of Homeric hexameter as an empty form—haunts modernity. Rather than regulating the unruly time of national culture, Arnold’s call for English hexameters was already an articulation of the temporal disjunction upon which the modern nation is predicated: a double temporality that is an equivocal movement, a present that is both continuous and discontinuous with the past, simultaneously historical and contemporaneous, progressive and repetitive. Metrical translations of Homer failed to achieve the fluency to which they aspired, as their flow was disrupted by misplaced accents and displaced caesuras. But this fluency defined by interruption was prefigured and indeed prescribed by Arnold’s reading of Homer; it was the caesura of the modern, played out in the metrical form of the double bar of those barbarous hexameters.

NOTES

1. Vladimir Nabokov, “Problems in Translation: ‘Onegin’ in English,” Partisan Review 22, 1955: 496–512. Reprinted in The Translation Studies Reader, ed. Lawrence Venuti (London: Routledge, 2000), p. 77.

2. John Lucas, England and Englishness: Ideas of Nationhood in English Poetry, 1688–1900 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1990), p. 184.

3. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983 and 1991), pp. 24–25.

4. Matthew Reynolds, The Realms of Verse 1830–1870: English Poetry in a Time of Nation-Building (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 274.

5. Matthew Arnold, On the Classical Tradition, ed. R. H. Super (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1960), p. 21. Unless otherwise noted, all references to Arnold will be cited in the main text from this edition.

6. George Saintsbury, A History of English Prosody, from the Twelfth Century to the Present Day, first edition 1906–1910. Page numbers (cited in the main text) are from vol. III of the 2d ed. (London: Macmillan, 1923).

7. In the 1860s at least six hexameter translations were published in England by C. B. Cailey (1862), J.T.B. Landon (1862), J. Dart (1862), James Inglis Cochrane (1867), Edwin Simcox (1865), and John F. W. Herschel (1866). In America, William Cullen Bryan experimented with hexameter before publishing his translation of The Odyssey in blank verse (1872); see also the American response to Arnold in The North American Review (1862).

8. From between 1860–1900 more than fifty British and American translations of Homer appeared, as listed by F.M.K. Foster in English Translations from the Greek, A Bibiographical Survey (New York: Columbia University Press, 1918), pp. 67–76. Various English translations (including excerpts from Victorian versions) are collected in Homer in English, edited by George Steiner with Aminadav Dykman (London: Penguin Books, 1996). On nineteenth-century ideas about Homer, see James Porter, “Homer: The Very Idea,” Arion, 10.2 (Fall 2002), 57–86.

9. Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility, pp. 144–45.

10. In Well-Weighed Syllables: Elizabethan Verse in Classical Metres (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974), Derek Attridge shows how Elizabethan experiments in quantitative verse moved “away from any conception of metre as a rhythmic succession of sounds, akin to the beat of the ballad-monger or the thumping of a drum” and toward an abstract, mathematized order “where words are anatomised and charted with a precision and a certainty unknown in the crude vernacular” (pp. 77–78). I am grateful to Derek Attridge for his feedback on metrical experiments in the Victorian period.

11. On the proliferation of metrical forms toward the end of the nineteenth century, see Yopie Prins, “Victorian Meters,” in The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Poetry, ed. Joseph Bristow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). On nineteenth-century experiments with hexameter in particular, see also Kenneth Haynes, English Literature and Ancient Languages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 131–33; Erik Gray, “Clough and His Discontents: Amours de Voyage and the English Hexameter,” in Literary Imagination: The Review of the Association of Literary Scholars and Critics 6(2) 2004, pp. 195–210; Christopher Matthews, “A Relation, Oh Bliss! unto Others”: Heterosexuality and the Ordered Liberties of The Bothie of Toper-Na-Fuosich,” Nineteenth-Century Literature 58.4 (March 2004), pp. 474–505.

12. See for example popular accounts in Victorian school stories of boys learning to read Homer (as in Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s Schooldays from 1857) and having the lesson (rhythmically) beaten into them (as in F. W. Farrar’s Eric, or, Little by Little from 1857 and St. Winifred’s from 1862). The practice of memorizing Homer was part of Victorian metrical education.

13. George Whalley, “Coleridge on Classical Prosody: an Unidentified Review of 1797,” Review of English Studies 2(7), 1951, p. 244. Whalley reprints S. T. Coleridge’s anonymous review of Samuel Horsley, On the Prosodies of the Greek and Latin Languages (1796), and notes that Coleridge also refers to John Foster, An Essay On the Different Nature of Accent and Quantity With Their Use and Application in the English, Latin, and Greek Languages (1763), and Henry Gally, A Dissertation against pronouncing the Greek Language according to accents (1754). Whalley further notes that Coleridge’s review coincided with yet another pamphlet published by Dr. Warner in 1797, Metronariston: or a new pleasure recommended, in a dissertation upon a part of greek and latin prosody (1797), but does not speculate further” what had aroused this sudden interest in Greek prosody and pronunciation” (p. 241).

14. In Romanticism at the End of History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), Jerome Christensen describes how the notebooks of Coleridge dedicated many pages to “notations of a staggering array of poetic meters, clouds of diacritical marks combined and arranged into the phantom of verse” (p. 99). According to Christenson, Coleridge discovered in his analysis of German and English hexameter how “each language falls afoul of the Homeric antecedent in its own way,” and therefore in his own experiments with English hexameter Coleridge “concentrated on the cadence, the modulation or fall of voice that accents poetic language.” See also Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch, “ ‘When Klopstock England Defied’: Coleridge, Southey and the German/English Hexamter,” in Comparative Literature 55(2), Spring 2003, pp. 130–63.

15. The comparison of Homer’s verse to the sea has a long history that continues in “Dactylic Meter: A Many-Sounding Sea,” a recent essay by Annie Finch who claims “the dactylic meter has rolled through Western literature like a ‘polyphlosboiou thalassa’ (many-sounding sea), to use a phrase of Homer’s.” In An Exaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of their Art, eds. Annie Finch and Kathrine Varnes (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002), p. 66.

16. Henry Nelson Coleridge, Introduction to the Study of the Greek Classic Poets, Designed Principally for the Use of Young Persons at School and College, Part I (1st ed. 1830; 2nd ed., London: John Murray, 1834). Coleridge writes, “In noticing the Versification of the Iliad, it may be truly said that its Meter is the best, and its Rhythm the least, understood of any in use amongst the ancients … not one ever maintained, for twenty lines together, the Homeric modulation of the Hexameter…. The variety of the rhythm of the Homeric Hexameter is endless … and all the learning in the world on the subject of Caesura and Arsis has no more enabled posterity to approach to the Homeric flow (American edition, Boston: James Munroe, 1842), p. 125.

17. Preface, English Hexameter Translations from Schiller, Goethe, Homer, Callimachus, and Meleager, by J.F.W. Herschel, W. W. Lewell, J. C. Hobhouse, E. C. Hawtrey, J.G.L. Lockhart (London: John Murray, 1847).