The Misplaced Head

Stockholm, April 6, 1821

Monsieur,

I have the honor of making to you a somewhat curious communication. In a meeting of your Academy of Sciences, where I was present during my sojourn in Paris, I heard the report made by members of the Academy who had been present at the transport of the bones of Descartes, I believe from the Church of Ste.-Geneviève to another place. It was announced that there were parts of the skeleton missing, and, if I am not mistaken, that the head was missing.

F THE SAGA OF DESCARTES’ BONES CAN SERVE AS a metaphor for modernity then it is doubly symbolic that during their peregrinations the head somehow got separated from the body and was to become, as it wound its way through the centuries, a source of mystery for various thinkers, artists, and scientists. For what does Descartes stand for today if not the cerebral over the material—the head over the body? Who bequeathed to us the mind-body problem?

F THE SAGA OF DESCARTES’ BONES CAN SERVE AS a metaphor for modernity then it is doubly symbolic that during their peregrinations the head somehow got separated from the body and was to become, as it wound its way through the centuries, a source of mystery for various thinkers, artists, and scientists. For what does Descartes stand for today if not the cerebral over the material—the head over the body? Who bequeathed to us the mind-body problem?

In the seventeenth century it was considered normal for thinkers to cover a fairly astonishing range of subjects in depth—all of reality, more or less. A Descartes or Hobbes or Leibniz might devote one major work to light and optics, another to geology, another to God, another to free will, another to the movement of the tides, another to that of the planets. As the 1700s went by such grandeur became less and less possible. A botanical treatise written in 1542 listed five hundred known plant varieties. By the end of the 1600s the catalog included ten thousand; in 1824 the Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle indexed fifty thousand plants. Specialization was by this time the only way to advance knowledge. Descartes and other natural explorers of his day believed that nature was a puzzle that just the right sequence of discoveries would unravel, leading to astounding changes that they could not even imagine. Of course, they were right about the astounding changes, but they were naïve in their appreciation of the puzzle’s complexity.

By the 1800s, there was much greater awareness of the complexity. The task of understanding the universe was in the process of being divided into different fields, and there was sometimes a geographic slant to the specialization. It so happened that the country in which Descartes had chosen to die was particularly rich in mineral deposits, making it a center of the newly emerging field of chemistry. Swedish chemists discovered a good portion of the sixty-eight elements known by the late nineteenth century, including oxygen, the elemental element, as it were (though since Carl Wilhelm Scheele’s discovery of oxygen in 1773 was beaten out for publication by Joseph Priestley, credit is often given to both men).

The greatest of these chemists—and one of the most prominent figures in the history of science—was Jöns Jacob Berzelius, the man who in 1821 sat down to compose the idiosyncratic letter whose opening is quoted above. He started life in rural Sweden, threshing hempseed and sleeping in the potato storage, launched himself in a career in medicine, but discovered that he loved experimentation and analysis more than healing. He found work at the School of Surgery in Stockholm under a revered professor of medicine and pharmacology named Anders Sparrman, lived in the house of a mine owner, and roomed with a physician who operated a spa where people went for its healing mineral waters—surrounding himself, in other words, with chemicals and chemistry. The young Berzelius was perennially short of cash and made a deal whereby in lieu of paying for his meals he would create new mineral water mixtures—seltzers, bitters, alkalines, “liver water”—for the spa goers’ pleasure.

Under Sparrman, Berzelius did some things—discovering the odd element—that today might merit a Nobel Prize, but when Sparrman retired Berzelius was passed over as his replacement. He was about to resign himself to a career as a country doctor but the young man who had been given Sparrman’s position died suddenly and Berzelius was granted one of the few jobs in chemistry that then existed in the world. He was a bluff, florid man with a capacity for enormous energy, and he went at his work with herculean intensity. One of the hurdles the field had to clear was determining the atomic weights of each element, which was necessary in order to know how elements could be combined with one another to form new compounds. In a feat of intellectual and physical labor that has become legendary among chemists, Berzelius set about fixing the weights of all the elements then known. He typically worked from six-thirty in the morning to ten at night; at one point he was nearly blinded in an explosion. The rewards were sweet. After fixing the combinations of silver chloride and sulfuric acid and barium hydroxide, he noted that “it is impossible to describe the bliss. . . . But to this end two years of ceaseless work had been given.” He published his results in what quickly became the standard textbook of chemistry. Meanwhile, hampered and annoyed, as others had been, by the chaotic terminology and symbols that various scientists had devised for the elements and their combinations—some looked like hieroglyphs or a child’s drawings—he invented what he thought was a clearer system, using letters from the beginning of the Latin terms for each element. He thus gave the periodic table—and the landscape of chemistry—the look that it has today.

Immediately following this burst of effort Berzelius suffered a nervous breakdown. Friends suggested travel as a way to recuperate, and he set out for the two capital cities of science. He was an international celebrity now and was received into the scientific inner circles in London and Paris. In London, this was the Royal Society; in Paris, it was the Academy of Sciences. These institutions reflected the different approach to science as it evolved in the two countries. The English were freelancers, and the Royal Society was something of a gentleman’s club. But if the top-down approach of the French retarded the growth of industry in France, it had an important benefit for the development of Western history. As an offshoot of the government, the Academy of Sciences was able to function with an authority that the Royal Society did not. As Maurice Crosland, a historian of science at the University of Kent in Canterbury, notes, this authority in defining what science was started with the word itself. The Royal Society had an approach to knowledge that was holistic and at times playful, one that hearkened back to the seventeenth-century natural philosophers. In the early nineteenth century its members still tended to use the word science in the broad medieval sense, so that theology could still be regarded as “the queen of the sciences.” Crosland argues that it was the French Revolution that nudged the members of the Academy of Sciences to begin restricting the use of the word to a particular type of secular investigation of the natural world, so that while in English science came into its current usage only in the 1830s, the Académie des sciences showed in its name that the French had long before moved in this regard in the direction of modernity.

The academy adopted an appropriately scientific approach to science, organizing itself into divisions, subdivisions, and sub-subdivisions, and in so doing helped define to this day the way knowledge is structured in university departments and research institutes. Astronomy, geography, chemistry, physics, mineralogy, botany, mechanics, agriculture—each branch had a department, and each department was tied to a school where that field was taught. Each held conferences, awarded prizes, funded research. When it was felt necessary, the members of the academy met to discuss whether to create a new subdivision, such as when the growing collections of fossils all over Europe led to the creation of a division of paleontology and then a subcategory of paleobotany.

Dating back to the period before the Revolution, the academy also defined what science was not. When Franz Mesmer came to Paris, having been run out of Vienna after causing an uproar with his “animal magnetism”—a precursor to hypnosis—members of the academy met in 1784 to consider whether “mesmerism,” as it also became known, had any scientific basis. Mesmer’s technique used magnets, long gazes, and pressure on the hands and arms to cause changes in patients; he argued that there was an unknown fluid, or “tide,” within the human body that could be shifted in this way to bring about healing. All of Europe was in a frenzy over whether animal magnetism was real or not. The Faculty of Medicine and the Academy of Sciences decided to weigh in. The committee of review they put together was something of an all-star team of eighteenth-century science, including Lavoisier, the father of modern chemistry, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, whose name was soon to become attached to the signature device of the Revolution, and, as visiting authority on electricity and other currents, Benjamin Franklin. In an early instance of the use of placebo and the single-blind trial, the scientists told some people they were being magnetized when in fact they were not, while others were magnetized without their knowing it. Those who had been told they were being magnetized, even when there was no actual magnet used, reported positive results; those who were magnetized without their knowing it showed no results. The scientists concluded that the evidence did not support the idea of the movement of tidal fluids within the body. Rather it demonstrated the effects of “the imagination.” The academy deemed that mesmerism was not science—and from that moment it was not. Mesmer left Paris the next year. Mesmerism went on to have a lively career in nineteenth-century America, but it eventually went the way of the wooly mammoth and ultimately history would demote Franz Mesmer’s immortal status from imposing noun to ephemeral adjective.

Berzelius arrived in Paris in 1818 as a guest of the academy. He was awed by Paris and the great houses where he was entertained and was fascinated both by the egalitarian nature of the salons (“In conversation there is no distinction between those of high station and other good folk. Titles such as Prince, Count etc. are never used in speech”) and by how highly evolved his field had become in the city (“I believe that there are here more than 100 laboratories devoted to research, and there are several dealers specializing in chemical glassware whose stock is a source of astonishment to a poor Stockholmer who, when he needs a simple retort, cannot obtain it in less than three months”). Salons may have displayed a democratic sensibility but the academy itself, the inner sanctum of European science, impressed Berzelius with its grandeur. The members even wore a specially designed costume, green with frilly gold trim (they were French, after all), which amounted to a scientific uniform. Berzelius’s trip was meant for recuperation, but he now felt rejuvenated enough to settle into a furious round of activity. With Claude-Louis Berthollet and Pierre-Louis Dulong, two of the great chemists of the day, he devised a way to further refine his calculation of the atomic weight of hydrogen. He met the discoverer of fatty acids and the discoverer of hydrogen peroxide, whom he admired (though the chemical had not yet evolved into a fashion statement), and he worked on a French translation of his book.

As it happened, Berzelius was in Paris when the third burial of Descartes’ bones took place. One of those who had been invited to the burial ceremony was Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre, the leading astronomer of the day and one of the two permanent secretaries of the academy, who functioned as codirectors. Delambre had a passion not only for science but for its history. His devotion to the ideals of precision and accuracy resulted in an achievement that has shaped the world to this day. Nearly thirty years before—in the midst of the Revolution—he had opened up a whole front of modernity by directing the project that led to the creation of the metric system. Throughout the centuries of the Middle Ages European localities had devised hundreds of different units of weight and measurement, which varied from village to village, and even those with the same name varied, so that a pound of bread or a pint of beer meant different quantities in different places. This nonsystem maintained local traditions but inhibited trade—on a very practical level it kept Europe medieval. The new, modern idea was to give everyone in the world one system, which would be based not on custom or legend or ancient myth but on nature—to be precise, on the scientific calculation of a natural standard.

The Revolution was a fitting milieu for such an idea to arise in, but it was also a dangerous one. A committee of the revolutionary government—the Commission on Weights and Measures—decided that the new base unit, the meter, should be related to the size of the globe, specifically that it should equal one ten-millionth of the meridian passing from the equator through Paris to the North Pole. Calculating this distance meant traversing a portion of it—basically the length of France—with sophisticated equipment for sighting and triangulating in order to obtain accurate measurements of individual stretches of the distance. This was the work that Delambre had undertaken as a younger man, and it was treacherous going. With a war on, he and his team of scientists and assistants—peering through scopes, adjusting sights, scribbling notes—appeared to the roving bands of revolutionaries and counterrevolutionaries as spies, and Delambre had dodged bullets and suffered imprisonment in fulfilling his mission. It would be some time before the metric system would be generally adopted (the first countries to accept it, the Netherlands and Belgium, would adopt the system just two years after the 1819 reburial of Descartes’ bones, and France itself would not do so until 1840), but Delambre had long since achieved international fame for it in the scientific community in addition to his accomplishments in astronomy when he agreed to participate in what he thought would be a pro forma ceremony to rebury the bones of the founder of modernity.

The old astronomer, then, duly oversaw the removal of a wooden casket from the porphyry sarcophagus in which Lenoir had placed the remains of Descartes, then marched in procession the few blocks up the hill from the garden of Lenoir’s former museum to the church, where, amid the stony medieval chill, the interior box was opened. What was found inside was remarkable enough that Delambre took notes and even included an account of the burial and contents of the coffin in his History of Astronomy, which he was just completing. “On an interior cask was attached a lead plaque,” he wrote, “on which, having cleaned it off, we could read a very simple inscription, carrying the name of Descartes, the date of his birth and that of his death.” Other than this, the officials were surprised to find only a few bones of recognizable shape; the rest was bone fragments and powder. The man who did the unpacking, Delambre added, “took some handfuls of powder to show us.” The assembly then watched as these meager remains were placed in the vault that had been opened to receive them and were sealed behind a heavy stone.

Others who were about to become caught up in the puzzle of Descartes’ bones would use words like “religious” and “precious relics” to describe the remains, but Delambre’s interest was different. At seventy, he was an old-guard atheist from the heyday of the Revolution and the Enlightenment; he had no truck with religious or spiritual sentiment. His interest was in science and historical accuracy. The contents of the coffin that had been in Alexandre Lenoir’s keeping seemed to tell a different story from the one that had been presented to Delambre and others. If the bones had been buried properly they would surely have survived the 169 years since Descartes’ death in a better state of preservation. Were these Descartes’ bones at all? Had he and the others solemnly buried the wrong remains? If they were in fact Descartes’, how did they come to be in such a condition?

But while Delambre’s interest was piqued, he didn’t pursue the matter further but only went back to his home and jotted down what he had witnessed. He did, however, discuss these observations with some of his fellow scientists, either before or after a meeting of the academy. Several other of these men had also been at the reburial, and as they talked they came back again and again to the skull. A human skull would survive relatively intact even under somewhat adverse conditions. It seemed inconceivable that it would be reduced to powder. The only conclusion was that it had been separated from the rest of the body. Apparently one of the scientists had done some investigating, and he reported hearing a suspicion that the skull had never been among the remains in France—that it had never left Sweden.

Berzelius, the Swede, was party to this learned gossip. He expressed indignation. If, somehow, one of his countrymen had separated the skull of the great Descartes from the rest of the bones—Berzelius didn’t shy from religious terminology and called it “certainly a precious relic”—then all Swedes should be reproached for such a “sacrilege.”

And there the matter ended. What else was there to do but remark on the strange facts and then leave them to molder along with the remains? Delambre attended to his duties as permanent secretary of the academy. Berzelius—his period of recuperation over—returned home and took up new duties that mirrored those of Delambre, as the new secretary of the Swedish Academy of Science.

Two years passed. Then one day in March 1821, Berzelius opened a Stockholm newspaper and found his attention caught by an article on the estate of the late Professor Anders Sparrman—the man whom Berzelius had first worked under at the School of Surgery, and whose position he had eventually taken. “Something curious has been noted recently,” the article read. “At the auction following the death of professor and medical doctor Sparrman, the skull of the famous Cartesius was sold. It is said to have been purchased for 17 or 18 riksdaler.”

Berzelius was stunned by the coincidence—that he had been in Paris when it was discovered that the skull of Descartes was missing and that, apparently, it had been in the possession of a man he himself had known. He immediately went to work. He contacted the auction house, and found that the skull had been bought by a casino owner—and evidently a fairly infamous figure—named Arngren. The vogue for maintaining a “cabinet of curiosities”—bones, tusks, fossils, carved artifacts, feathered headdresses, seed pods, fertility charms, butterflies, dried dung: a microcosmic attempt to make order out of the teeming chaos of the natural and anthropological worlds—was then at its height, and Arngren seemed to have thought the skull of the great thinker would make a nice addition to the one on display at his casino. Berzelius went to him, outlined the history of the bones of Descartes, and explained that it had recently been discovered in Paris that the head was missing. To Berzelius’s surprise, Arngren agreed to give the object to Berzelius for what he had paid for it.

Berzelius then sat down to write the letter quoted at the start of the chapter, which accompanied the remarkable object itself, the skull of Descartes. His closest associate at the academy in Paris was Berthollet, his fellow chemist, but he thought it best to write to the biologist Georges Cuvier, both because Cuvier had also taken a keen interest in Descartes’ bones and because he served alongside Delambre as the second permanent secretary. On receiving the skull, Cuvier decided it would be kept in the Museum of Comparative Anatomy, which was part of the Museum of Natural History. But he wasn’t about to store it away just yet. It merited special attention.

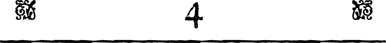

The skull of Descartes. Across the forehead, in Swedish, is an accusation of a theft in 1666 that began the skull’s peregrinations. Above it is a poem in Latin celebrating Descartes’ genius and mourning the scattering of his remains.

An eighteenth-century depiction of the court of Queen Christina in Stockholm by Pierre Louis Dumesnil. Descartes is standing to the right; the Queen is seated opposite him.

A seventeenth-century image showing The Dam, the central square in Amsterdam, shortly after the time Descartes lived there.

Anatomical drawings by Descartes illustrating mind and body interactions from his book Tractatus de Homine.

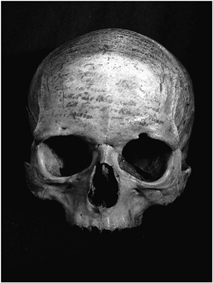

Title page of the first edition of Descartes’ epoch-making work.

Drawings of Henricus Regius (left), Descartes’ first “disciple,“ and Gysbert Voetius, who led the attack on Descartes in the Netherlands in the 1630s.

The location of Descartes’ home in the Dutch city of Utrecht, as it was in the 1640s.

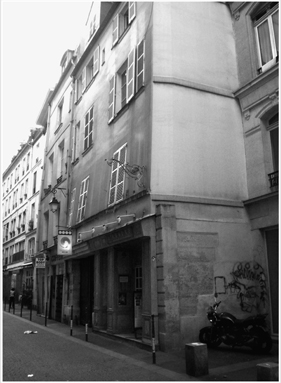

The building in Paris that was the site of Jacques Rohault’s weekly Cartesian salon in the mid-1600s. Today it houses a karaoke bar.

A meticulous eighteenth-century rendering of coffins and remains found in the old Church of St. Geneviève. It includes no indication of the coffin of Descartes.

The Church of St. Geneviève in Paris, on the right, was the second resting place of Descartes’ bones, from which Alexandre Lenoir supposedly retrieved the remains during the upheaval of the Revolution. The church no longer exists.

Alexandre Lenoir, in a print showing him protecting tombs and monuments from the depredations of revolutionaries.

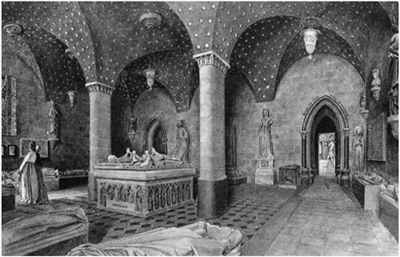

An eighteenth-century drawing depicting the interior of Alexandre Lenoir’s Museum of French Monuments, which Napoleon said reminded him of Syria.

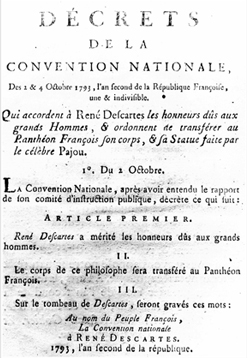

The decree of the revolutionary National Convention in Paris, dated October 1793, which gave Descartes, and his remains, special honors.

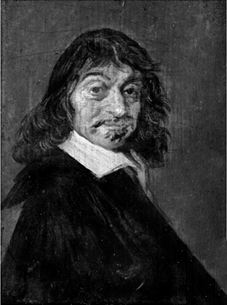

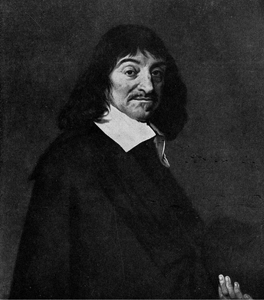

The portrait of Descartes now credited to Frans Hals.

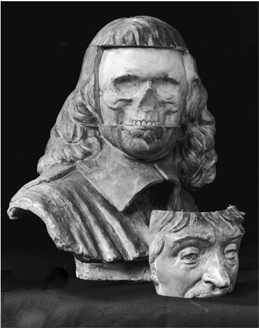

The bust of Descartes created by Paul Richer in 1913, with its breakaway face.

The classic portrait of Descartes in the Louvre, which was long thought to be by Frans Hals.

Paul Richer’s analysis of the skull of Descartes hit the New York Times on January 26, 1913.

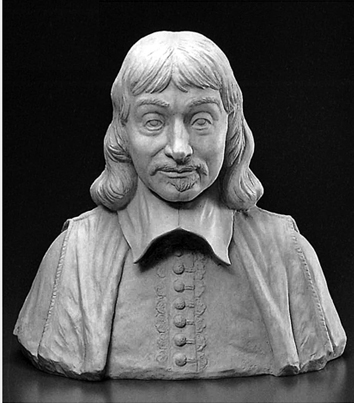

The bust of Descartes, based on the skull, created for the 2000 Great Exhibition of the Face in Tokyo.

AT LEAST AS MUCH as others who would be associated with Descartes’ bones—Rohault, Condorcet, Alexandre Lenoir, Delambre, Berzelius himself—Georges Cuvier personified a major aspect of modernity. Indeed, all three of the men who involved themselves with the bones at this stage made their names in association with what was the principal scientific concern of the day: classification and measurement of the overwhelming amount of data that was coming in from all quarters. Delambre brought into being what would become the global standard of measurement. Berzelius developed the modern method of representing the chemical elements and ascertained how they combine to form virtually every substance on earth. The situation in biology was particularly complex. Biologists craved the sort of base principles that Newton had developed for physics. Trying to classify life-forms begged the question of what overall purpose you had in mind. The system that was still largely in effect in the early nineteenth century was the “teleological taxonomy” created by Aristotle and refined by the Scholastic philosophers: the “scale of beings” system, which the French called the série, or series, and which is popularly known as the “great chain of being.” As with the medieval system of bodily humors, it was far more complex and useful than its popular stereotype suggests, but it had a serious limitation, which was its teleological basis. Teleology refers to an end or ultimate purpose and typically means a religious purpose, as in God’s plan. Aristotle’s orientation of knowledge was teleological, which made it easy for the Scholastics to adapt it to conform with a Christian view of creation, so that as the chain of life-forms proceeded from the simplest organisms to more complex ones it also reflected a spiritual hierarchy. In the eighteenth century this system began to lose its usefulness. By the early nineteenth century biologists and botanists had a frank case of “physics envy”—a yearning for a Newton-like figure to create underlying laws to ground their science. Cuvier argued for a completely new system that ignored teleology and instead grounded itself in observation of bodily parts and their functions. In coming up with his system, he helped invent modern zoology and comparative anatomy.

Cuvier’s work built on that of his predecessor, the Swede Carl Linnaeus, who had ranked living creatures into kingdom, class, order, genus, and species. Linnaeus had looked to the parts of the reproductive system as a basis for classifying and differentiating creatures, but while reproduction was undeniably elemental, it was not necessarily the most useful organizing principle. Cuvier based his system instead on the correlation of parts and how those parts worked together and in a creature’s environment (an animal with sharp claws also tended to have teeth appropriate for tearing into the prey it captured). He divided animals into four categories based on body structure—vertebrates, mollusks, articulates (for example, insects), and radiates (for example, starfish)—a system that remained basic to biology for most of the modern era. Cuvier applied his system with an almost mathematical logic. A ruminant animal, by definition, had to have a forestomach in which it partially digested its food, so if you found an animal with such an internal arrangement you knew it was a ruminant, and conversely if you found an animal without a forestomach it could not possibly be one that digested its food in two stages. A perhaps apocryphal story has some of Cuvier’s students wrapping one of their number in a cowhide and challenging their teacher to identify the beast. As the master entered the room, the student cried, “Cuvier, I am the devil, I’ve come to eat you!” Whereupon Cuvier is supposed to have replied something to the effect of “Don’t be ridiculous. You have a divided hoof, therefore you eat grain.”

Comparative anatomy was only one of the fields that Cuvier pioneered. His interest in bones led directly to the study of fossils. Comparing skeletons of extinct animals of different geological eras led him to conclude that the earth had endured several prehistoric cataclysms, resulting in mass extinctions. He noted, of course, the slight alterations in skeletons of seemingly related creatures but did not argue in favor of a theory of evolution. It was in the air at the time; his countryman and colleague at the academy Jean-Baptiste Lamarck had recently advanced an evolution argument. But, to the contrary, despite his many groundbreaking accomplishments, Cuvier is best known today for retarding the advance of evolution in the scientific community, keeping it from serious consideration until the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859. Technically, scientifically, Cuvier’s objection was based on his theory of the correlation of parts. Nature, he wrote, “has realized all those combinations which are not repugnant and it is these repugnancies, these incompatibilities, this impossibility of the coexistence of one modification with another which establish between the diverse groups of organisms those separations, those gaps, which mark their necessary limits and which create the natural embranchements, classes, orders, and families.” That is, every species that exists, or that ever did exist, was a functional whole that needed all of its parts to be just the way they were. A slight mutation in one part would collapse the whole system. Evolution based on small changes over generations was thus impossible. Instead, Cuvier argued for the opposite—“fixity of the species”—and did everything in his power as permanent secretary of the Academy of Sciences to advance that view.

There was a less scientific aspect to Cuvier’s views on evolution. He was a devout Christian, and the early nineteenth century was a time when Christians were using science to undergird the Bible. Such efforts, of course, went back to Descartes himself, who believed that his mechanistic theory of nature was in fact a defense of Christianity—that it “bracketed” the material world, making it the domain of science and leaving theology free to treat the human soul. Belief in science had grown enough by the early nineteenth century that even quite literal-minded Christians tended to look to science for evidence to support, for example, the biblical account of creation or the flood that Noah navigated.

Cuvier was a rigorous scientist and he didn’t overtly manipulate data to support Christian accounts. However, he was interested in showing that science and faith were compatible, and his approach to biology and paleontology reflected that. The problem was that scientific evidence seeming to contradict basic parts of the Bible had become mountainous. He took account of the same evidence that Darwin would use to argue for changes in species over time based on natural selection but made it serve the opposite theory, one that squared with biblical views of creation. In a way, his argument has a curiously modern sound. He believed in God unquestioningly—in fact regarded it as a misuse of reason to question God—and his belief underlay his science, including his views about the “repugnance” that nature had for changes to its design. For Cuvier, in other words, nature showed the intelligence of the Creator, and the idea of species evolving over time, buffeted by random forces, was repellent both to this larger intelligence and to human intelligence. Beneath his science, then, is a nineteenth-century variant of the very current “intelligent design” theory put forth by Christian thinkers who, like Cuvier, believe that the theory of evolution does harm to the Christian account of the world.

Cuvier was nevertheless one of the models of a nineteenth-century scientist, and as such he had a love of his field’s development, its increasing complexity, and also its beginnings. When, in May 1821, he received, from the hands of the Swedish ambassador to France, a package sent by Berzelius from Stockholm along with the letter describing his serendipitous discovery, he opened it with something approaching awe. Like Delambre, he had been dismayed by the discovery of the sorry state of the remains during the reburial two years before and by the absence of a skull. Now here was an object that seemed to deepen that mystery and to open another.

To be sure, the skull was no ordinary object—it wasn’t even an ordinary skull. In the world of art and old paintings, provenance—a paper trail, authenticating proof of a chain of past ownership—is everything. This skull seemingly arrived with its own provenance, which deepened Cuvier’s interest. He contacted Delambre at once, and the two put the subject on the agenda at the academy.

On April 30, 1821, the Academy of Sciences met at its home on the banks of the Seine. The members included some of the most famous names in the history of science, among them Berthollet, who helped create the language of modern chemistry; Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, he of the evolution theory; Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac, who formulated several laws of physics, codiscovered the actual chemical composition of water, and did the underlying work that led to the “alcohol by volume” calculation that is found on every bottle of wine, beer, and spirits; Pierre-Simon Laplace, who extended the work of Newton in mathematical physics and theorized on the origin of the solar system; and André-Marie Ampère, a discoverer of electromagnetism, for whom one of the basic units of electrical measurement is named. They heard a report on the inflammation of the membranes of the central nervous system. A member named Poyet presented some examples of new methods of bridge construction he had developed. There was a report on the medicinal properties of flowers of the Antilles. Then the assembled luminaries gathered around the object that Cuvier placed before them and studied it with, as the chemist Berthollet said, “a religious reverence.” Cuvier read Berzelius’s letter recounting how he came to be in Paris at the time Descartes was reburied and heard of the absence of a skull among the remains and how, only a month earlier, he discovered that a skull purported to be Descartes’ had come up for auction. “Our minister in Paris, M. le comte de Löwenhjelm, who left here the day before yesterday, was kind enough to take charge of the transport of this relic,” Berzelius’s letter said, “of which I pray you, Monsieur, to make use that you judge reasonable.”

The skull was missing its lower jaw but was otherwise intact. With its empty black sockets it gazed back at this historic collection of wise men as if chiding them for whatever smugness they may have accumulated in their quest to advance knowledge, forcing them to ponder the hard limit they all faced, the remorseless indifference of death.

At the same time, it offered a challenge. For these were all men who had devoted their lives to solving nature’s puzzles, for whom method had become second nature, and here was a puzzle about the man who was arguably the father of all their varied disciplines, the very originator of “the method.” The tantalizing thing was that the skull was covered with intricate pen marks. Many were signatures, marks of ownership. But splayed across the top, in fl owing Latin cursive, was a poem that fairly shouted at the observers:

This small skull once belonged to the great Cartesius,

The rest of his remains are hidden far away in the land of France;

But all around the circle of the globe his genius is praised,

And his spirit still rejoices in the sphere of heaven.*

The questions piled up. Who had written this, and when? What did “hidden” mean? Was it possible that the bones they had reburied in St.-Germain-des-Prés were not Descartes’? Was this indeed Descartes’ skull, and if so how had it gotten separated from the body? What exactly had happened to the remains of René Descartes in the 171 years since his death?

A further clue—seemingly a fairly massive one—also offered itself on the skull. This one was right in front, scrawled across the forehead. It was written in Swedish, but Berzelius had provided a translation:

The skull of Descartes, taken by J. Fr. Planström, the year 1666, at the time when the body was being returned to France.

Cuvier had done some investigative work and was inclined to support the authenticity of the skull. For corroboration, he placed alongside it an engraved portrait of Descartes and pointed out for the savants what he took to be similarities in cranial features. But more work needed to be done. There were all sorts of oddities; for one, above the sentence about the mysterious Planström were some barely legible words—a name that was hard to make out, “1666” again, and once more the Swedish “tagen,” which Berzelius told them meant “taken.” Cuvier wanted further information about “this precious relic.” The members agreed that someone should continue the research. Then they moved on to other business, perhaps no less of interest, with a Monsieur Virey rising to present his paper on “The Membrane of the Hymen.”

IT WAS DELAMBRE who took up the matter of investigating the skull. Delambre revered Descartes as a father of science. Delambre also knew that his own major work in the service of science was behind him. He was seventy-two years old and not in good health; the odd little task he was about to undertake could become a coda to his scientific career.

At the meeting of the academy on May 14, 1821, he presented his findings in a report that ran to three thousand words; his reading of it took up nearly the entire session. He titled it “Skull coming from Sweden said to be that of Descartes: Facts and Reflections,” and indeed it was organized into a series of “Facts” each followed by a section labeled “Remarks.”

But if his colleague Cuvier was anticipating an exhaustive confirmation of his own speculations, he was to be disappointed. Having completed his investigation, Delambre felt strongly enough about the matter that he deemed it necessary to assume the role of opposing attorney. Across the top of his report he scrawled his conclusion: “M. Cuvier . . . believes that the skull is that of Descartes, because he finds great conformities with the engraving, and I believe the opposite.”

He began reading aloud. He gave his colleagues a history of the pertinent events associated with the bones of Descartes, culminating with the third burial ceremony, two years earlier, at which he and others were shown the contents of the coffin, whose meagerness he characterized as “really a bit remarkable.”

Then he turned his attention to the object before them. The marks tattooing its surface were intriguing, he admitted. “But,” he said, “what proof have we from elsewhere regarding its authenticity? Some inscriptions, more or less effaced, that one makes out on the convexity, which are the names of the successive owners, with some dates and nothing more.” True, there was what seemed to be a testimonial of some sort on the skull. But who was to say who this Planström was? And what information could be had about the presumed accuser who had written this barely legible sentence about him? One could infer almost anything from it. Even if Planström had indeed taken the skull in 1666, it didn’t indicate when the skull was actually separated from the body. That could have been done “either at the home of Ambassador Chanut, immediately after the death, or in the provisional grave of 1650, or in the tomb of stone, or in the presence of Terlon in 1666, or finally at Peronne when the cask was opened by the customs officials.” It was even possible, Delambre added, that it had been removed for a particular purpose that was part of the historical record. It was known that Chanut had had a death mask made of Descartes, from which a French artist named Valary who had been a regular of Christina’s court had sculpted a bust (both the death mask and the bust subsequently went missing). Could it not have been that the sculptor “separated the head from the trunk in order to cast it at his ease and that he then neglected to return it?” Delambre asked his colleagues. “One at least has to admit that it has some plausibility.” That would mean there was a gap of sixteen years from the time the head was separated from the body until this novel record on the forehead of the skull indicating that Planström had “taken” it. How did one know that someone early on, knowing of the fuss over the unburying of Descartes’ bones, had not had the notion to adorn a random skull with writing in order to perpetrate a prank or deception, perhaps to make money? And once the first owner was deceived, all the others would have accepted the provenance as genuine. All they had, Delambre insisted, was “one assertion lacking proof” that the brain inside this skull had once thought “I think, therefore I am.”

All in all, Delambre considered it most likely that the skull had never left the body. The remains Delambre had seen in the coffin were mostly fragments, which, on consideration, suggested to him that the body had suffered severe exposure, and it was logical to suppose the skull had been treated similarly and had been reduced to a similar state: “It is not impossible that it is very well the same with the skull after 169 years.” Delambre concluded with a request that his report be included in the register of the academy “in order that someone may respond to my objections or clarify my doubts.”

It didn’t take long for a response. Cuvier seems to have sat listening to his illustrious colleague with mounting bewilderment. Delambre’s report was a stew of contradictions and irrelevancies. Cuvier rose to address his colleagues. In any analysis, Cuvier believed, common sense had a part to play in one’s reflections. Why imagine, for instance, that the head might have been sawed from the body immediately after death in order for the bust to be created? What possible basis was there for so grisly a supposition? Cuvier chided his fellow secretary for manufacturing elaborate scenarios and suspicions. The “principle of parsimony,” a tenet of science, says that it is better to prefer simpler explanations to more convoluted ones. Surely it was more sensible to suppose that this Planström had taken the skull than to imagine someone not taking Descartes’ skull but using another man’s head and inventing a fiction around it. Especially considering what had launched this investigation: the fact that when the coffin was opened two years earlier there was no skull found with the remains.

Besides, Cuvier asserted, the skull itself indicated when it had been taken from the rest of the bones: in 1666. That meant the year the remains were unearthed in Stockholm, at or around the time of the ceremony in the residence of the French ambassador. It seemed clear to Cuvier that “the moment when this head would have been removed must be when the bones were packed up to be taken to France.” As to who took it, there was clear evidence to that as well—not conclusive but compelling: “Planström.” Find that man, and the mystery would begin to unravel.

Cuvier might have wondered about his colleague. Physically, Delambre, as he laid out his views on Descartes’ skull, probably presented to his fellow scientists a reduced figure from what he had been even a few years before. He was ill enough that he was making arrangements for his own death (he would be dead the following year). Could senility or some weakening ailment have affected his reasoning powers? Every member of the academy knew of Delambre’s tremendous tenacity and determination, which either stemmed from or was exemplified by a childhood incident. When very young, he had been stricken by smallpox, which partially blinded him and, to boot, left him without eyelashes, giving him, for the rest of his life, a naked, preternaturally defenseless aspect, simultaneously intense and wan. Imperfect eyesight had led him to overcompensate: he read voraciously in his youth, willing his vision to improve, and it did. Then, like someone struck by a muscular disorder who vows to become a professional athlete, he developed a desire to peer into the tiny aperture of a telescope, to squint at points of light hundreds of thousands of miles away and see new things in them. He subdued his distinct handicap to the point of becoming the leading astronomer of the day, not to mention devising the standard of measurement that would revolutionize science.

But were his powers still intact? Cuvier must have wondered. Delambre seemed to have gone to great lengths to create difficulties in his analysis of the skull. It might be worth noting another possible explanation for Delambre’s refusal to allow informed speculation into his thinking. He had a particular and highly unusual reason for sensitivity toward anything that smacked of uncertainty in scientific investigation—one that neither Cuvier nor any of his other colleagues in the academy could have known and that, if it had been known, would have caused a scandal.

Thirty years before, when Delambre led the team that did the calculations from which to derive the length of the meter relative to the circumference of the earth, by measuring the arc from Dunkirk to Barcelona, he had had a partner named Pierre-François-André Méchain. The two astronomers had divided the work, Delambre starting in Paris and going north and Méchain heading south. Late in the game, after years of toil, thousands of miles of travel, and untold calculations, and with the final result established, Delambre had made a devastating discovery. His partner had miscalculated, then covered up the error in his work. Delambre had made this discovery in 1810, eleven years before his encounter with Descartes’ skull. He then made what Ken Alder, author of The Measure of All Things (2002), considers a fateful personal and professional decision. He covered up the cover-up. In the archives of the Observatory of Paris Alder found Delambre’s handwritten notes, which had apparently lain unseen since he wrote them: “I have not told the public what it does not need to know. I have suppressed all those details which might diminish its confidence in such an important mission. . . . I have carefully silenced anything which might alter in the least the good reputation which Monsieur Méchain rightly enjoyed.” Yet Delambre had preserved the logbooks with their errors, along with the acknowledgment of his own discovery. He had anguished over the issues of truth, error, and certainty and had made an allowance for error and uncertainty. Now, at the end of his life, working on a project of little real-world significance but a certain symbolic importance, Delambre was struck by a need either to have absolute certainty or else to dismiss entirely the skull’s legitimacy. There’s no way of connecting this need to the discovery of a scientific error and his decision to hide it, but Alder’s own thesis is that Méchain’s error and Delambre’s discovery of it are important in the history of science because these twin facts show the dawning realization on the part of “hard” scientists that certainty is impossible, that error and inaccuracy are a component of their work. If Delambre’s willingness to bury his partner’s error indicates an awareness of the very modern notions of probability and error as facts of life, then his refusal to consider circumstantial evidence in support of the authenticity of Descartes’ skull was perhaps a tug in the other direction—a reflexive urge to eradicate uncertainty, to purify.

Cuvier, meanwhile, thought the evidence regarding the skull strong enough that he took over the investigation. More needed to be known about the circumstances of the disinterment in Stockholm. He contacted a man named Alexandre-Maurice Blanc de Lanautte, comte d’Hauterive, who held the government position of archivist in the office of foreign affairs. Hauterive had had an exotic career, serving in Constantinople as part of the French diplomatic mission to the Ottoman Empire and in New York as consul to the newly founded United States before settling into a research position. Cuvier told him the particulars of Descartes’ life and death and the names of the officials who had been involved in the transport of the remains. Perhaps an answer would be found in the official correspondence of the time.

Cuvier, Delambre, and Hauterive had access to the same early source on Descartes’ life that we have today: the biography by the seventeenth-century priest Adrien Baillet. Cuvier noted that Baillet indicates in his biography that he had available to him letters from Terlon to d’Alibert, the treasurer of France, and a written note by Simon Arnaud, the marquis de Pomponne, who was in the process of succeeding Terlon as ambassador to Sweden and who attended the 1666 exhumation and the ceremony at the ambassador’s residence.

Hauterive, however, was unable to find any relevant documents in the government files. “The correspondence of M. le Chevalier de Terlon, minister from France to Sweden in the years 1666 and 1667, makes not a single mention of the transport to France of the remains of Descartes,” Hauterive reported to Cuvier.

But he did find something. He went on to add that “one had the idea to consult various printed works, one of which presented curious information on the object in question.” Hauterive had discovered a Swedish work from the mid-1700s citing a chain of ownership of the purported skull of Descartes. There was an originating name and a story to go with it. The man who had taken the skull, according to this source, had played a role in the events surrounding the first disinterment. The source gave this man’s name: “Is. Planström.”

AND SO WE GO BACK to the beginning, which is to say the end—the dead of night in the dead of winter in the year 1650. In an upper-floor room of a building in central Stockholm, an ailing man breathes his last. After some dispute, it is decided to bury him in a forlorn cemetery a mile away, on the outskirts of the city. The suns of sixteen summers warm the earth in which the remains lie, and the deep cold of sixteen winters freezes it. Within the first 128 days—according to estimates of modern forensic anthropology and based on an average temperature of 50°F—the soft tissue would have decomposed. The bones would likely have begun to bleach in the first year. Before ten years had passed the bones would have started to exfoliate and crack. If the coffin was weak (it was described as “porous”), roots, rodents, and worms would hasten the decay.

Sixteen years after burial, then, the remains are dug up and hauled back to the same building in which the man had spent his final hours. There, in the chapel of the French ambassador’s residence, a ceremony is held, presided over by officials of the Catholic Church in Sweden. The bones—which have become separated—are transferred to a copper coffin that is two and a half feet long. Hugues de Terlon, knight of St. John and French ambassador to Sweden, who is in the process of assuming his new post in Denmark, asks permission to take, as a personal relic, a bone of the right index finger. The coffin is kept, until the time of departure for Paris by way of Copenhagen, at the residence of Terlon, where it is watched over by members of the Stockholm city guard.

Isaak Planström was the captain of this guard contingent. The details of his involvement came via Hauterive’s information. Hauterive discovered that in 1750 a school headmaster named Sven Hof, from the town of Skara, wrote of traveling some years earlier to Stockholm to visit a friend and colleague named Jonas Olofsson Bång, who proudly showed him the skull of René Descartes. With the object came a story. The skull had come down to Bång from his father, a brewer and merchant named Olof Bång who had told him how he came by it. A man who had owed him money had died, and the elder Bång collected some of his property in lieu of payment. Among the items was the skull of Descartes. Bång told his son that the deceased, Planström, had had the job of watching over the remains of Descartes before they were to be shipped to France. Planström had explained his act by saying he felt that Sweden should not “lose completely the remains of such a famous person.” Bång said that the guardsman kept the skull for the rest of his life as “a rare relic of a philosophical saint.” Bång in turn kept it for the rest of his life and passed it to his son.

The younger Bång told this story to his friend Hof, then apparently said something to the effect that he would like to find appropriate words with which to adorn the object, whereupon Hof wrote out a few commemorative verses in Latin, and Bång later inscribed them onto the top of the skull. Hof’s account included the Latin lines, which were identical to those on the skull that was now in the possession of the academy.

Berzelius, in his letter to Cuvier, noted the various names adorning the skull, some of which were illegible or only partly legible, and suggested that it should be possible to work out from them a history of the skull’s career in Sweden. In the 1860s and 1870s, a man named Peter Liljewalch did that. Liljewalch was born in the Swedish city of Lund, became a medical doctor and specialist in infectious diseases, joined the army and traveled to Denmark, Germany, and Russia, and eventually became court physician to Desideria, queen of Sweden and Norway from 1829 to 1860. Sometime thereafter, Liljewalch returned to Lund and settled into the curious retirement project of charting the Swedish owners of the skull of René Descartes.

In the summer of 2006 I traveled to the manuscript division of the Lund University library, where a librarian laid before me the collection marked “Liljewalch.” I opened folders filled with delicate sheets covered with notes in an elegant nineteenth-century hand. Liljewalch had followed trails backward in time, pursuing the lives and deeds of the men who, for one reason or another, had come into possession of the skull. Somehow the cranium made its way from the younger Bång to a military man named Johan Axel Hägerflycht, who kept it until he died in 1740. When his goods were dispersed the skull fell into the hands of a government official named Anders Anton Stiernman. His is one of the names still visible on the skull, on the right side, along with a year, 1751. When Stiernman died his son-in-law, Olof Celsius, found himself its owner and promptly placed his own signature on the occipital bone, at the lower back. This Celsius was a man of the cloth who became the bishop of Lund. His interest in the head of Descartes must have been as a scientific charm or talisman, for science was in the family. His father was a botanist, other elder relatives were astronomers or mathematicians, and his cousin Anders Celsius was the astronomer for whom the temperature scale is named.

At first blush Johan Fischerström, the next owner, an “economic superintendent” in Stockholm, does not seem to have satisfied the skull’s penchant for finding its way to people who had pointed associations with one or another of the main features of modernity. But Fischerström was evidently a man of passion, and the notable aspect of his life turns out to have been not his career but his love interests. He became the object of affection of Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht, who is sometimes referred to as Sweden’s first feminist. She was a serious student of philosophy and the doyenne of Stockholm’s leading Enlightenment-era literary society, the excellently named Order of the Mind Builders. Nordenflycht became renowned for her mix of philosophical moodiness—over issues such as the role of reason in shaping moral decisions—and lovesickness. Her fame came from her poetry, in which she explored themes of nature and loss. She met Fischerström at a Mind Builders gathering sometime in the early 1760s, when she was in her early forties and he was in his late twenties, and fell for him. He left her for a younger friend of hers, and legend has it that she drowned herself as a consequence. The cad Fischerström lived on and procured the skull of Descartes sometime after to add it to his cabinet of curiosities.

Fischerström kept the skull until he died in 1796, and when his property was auctioned off it was bought by a tax assessor named Ahlgren, whose signature can today barely be made out behind where the left ear would be.

In the 1760s, while Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht was suffering the inattention of Fischerström in Stockholm, another Swedish devotee of eighteenth-century philosophy, named Anders Sparrman, was getting the best possible scientific education, under the tutelage of the great botanist Carl Linnaeus. On completion of his study Sparrman signed on as a ship’s surgeon in order to travel to Asia. He returned after two years in China laden with samples of the country’s flora and fauna, which formed the start of his own cabinet of curiosities. In 1772, fueled by a passion for collecting specimens of the natural world, he ventured to Africa, where he supported his collecting habit by dispensing medical advice and teaching the children of an official of the Cape Colony. One day late in the year an Englishman named John Forster showed up, off a ship that was anchored in Table Bay. Forster was himself a naturalist, and the two instantly became fast friends. Forster avowed that there was no better place for an enthusiastic young naturalist such as Sparrman than on board the ship on which Forster was at that moment serving. Its captain, James Cook, was then in the midst of his second voyage of discovery, and Forster convinced Cook that the Swedish naturalist would be a valuable addition.

Having thus hitchhiked his way into history, Sparrman spent the next three years at sea with Cook, skirting the pack ice of Antarctica and rounding the Antarctic Circle, circumnavigating New Zealand and exploring Tahiti and other islands of the South Pacific. One part of Cook’s mission was a modern challenge to received wisdom much as William Harvey’s theory of the circulation of the blood was a challenge to the older system of bodily humors—or indeed as Descartes’ philosophy represented a confrontation with the medieval system of knowledge developed by the Scholastic philosophers. The Royal Society had charged Cook with finding the continent of Terra Australis, which had been theorized by Aristotle and later writers to lie at the southern pole. The ancient thinking was that a giant land mass must exist at the bottom of the earth to counter those at the northerly extremes. Many members of the Royal Society remained convinced of the logic of this, though Cook himself had all but concluded, based on his first voyage, that it was not so.

Besides assisting in the voyage that would disprove the existence of Terra Australis—and that would in several other ways broaden knowledge of the world—Sparrman took copious notes and from them wrote A Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope, which became one of the classics of eighteenth-century naturalism and a standard source on Cook’s career. Later, after mounting an inland expedition of his own into South Africa, Sparrman returned home to Sweden laden with specimens. He then made a trip to London to visit what were widely considered the greatest cabinets of natural objects.

By the time he settled down again in Stockholm he had been showered with honors as one of Sweden’s great scientists. He took up a position as professor at the School of Surgery in the 1790s. In 1802, the young Berzelius won a position as his unpaid assistant. Three years later, Sparrman retired, and Berzelius eventually assumed his professorship. About that same time, Ahlgren, the tax official, apparently communicated to his friend Sparrman that he had come into possession of an object that he thought might interest the professor. The poignancy could not have been lost on Sparrman. He had traveled the globe gathering skulls and femurs, fibulas and fossils from every variety of creature. The skull that had given birth to modern philosophy would crown his collection.

So it was that while Alexandre Lenoir was tending to what were purportedly the rest of the bodily remains of Descartes in the garden of his Museum of French Monuments in Paris, the skull was in Stockholm in the collection of Berzelius’s former mentor. Berzelius, who happened to be in Paris when the remains were removed for burial, thus became the link that reconnected mind and body, so to speak.

Or was he? Could the savants at the French Academy of Sciences conclude that the skull was authentic? None of them knew much of this history of the skull’s life in Sweden, but the information from Hof supported the case. Cuvier and Delambre held a follow-up meeting at the academy five months after the first viewing of the skull, and Delambre presented a supplemental report in which he commented on the new information provided by Hauterive. It had its compelling features, Delambre admitted, but he remained skeptical, and he had some justifications for skepticism, for new difficulties came with the evidence of headmaster Hof. Hof asserted that “Isaac Planström, officer of the guard for the city of Stockholm, removed the skull from the bier of Descartes, for which he substituted another.” If that was true, it would explain why those who dealt with the remains later—the customs officials who opened the coffin at the French border in 1666, among others—did not report anything amiss. But it added a new mystery: what became of this second skull, the ersatz head of Descartes?

While the French scientists were puzzling over these questions, Berzelius happened to write to a Swedish friend telling him of the strange circumstances surrounding the skull of René Descartes and what he believed to be his satisfactory resolution of them. The reply he got may have incited a groan. The story sounded quite fascinating, wrote Hans Gabriel Trolle-Wachtmeister, a nobleman and government official with an amateur interest in chemistry, “but are you completely sure it’s the right skull?” In Lund, Trolle-Wachtmeister informed Berzelius, was another skull of Descartes, “to whose authenticity the rector and council are prepared to swear.” He added drily that in the scheme of things it wouldn’t be unjust if it turned out the great Descartes had had two heads since “we see how many fools have one.”

Was this, then, the second skull? Were there indeed two skulls of Descartes in circulation, one genuine, the other a placeholder slipped by Planström into the copper coffin? But if so, how was it that both had remained in Sweden? Wouldn’t one of them have ventured to Paris with Terlon’s party?

The complications were only beginning. In Paris, the savants were puzzling over another item. The information about Sven Hof was embedded in a four-volume biography of Queen Christina by a man named Johan Arckenholtz; it was in the first volume, which was published in 1751, that he included Hof ’s account of the encounter with Descartes’ skull. By volume 4, which appeared in 1760, Arckenholtz had himself entered this exotic subplot: he reported that in 1754 he had “made the acquisition of a part of this skull that is attested to be genuine and of which the other part rests in the cabinet of the late M. Hägerflycht.” So it seemed that there were now four skulls or skull pieces that had supposedly once belonged to Descartes. The situation was beginning to mirror the relic trade of early Christianity, when saints’ bones proliferated and, as John Calvin wrote with Protestant scorn, there were enough pieces of the “true cross” circulating around Europe to fill a ship’s cargo.

It’s possible, though, to wade through at least some of the cranial debris. Trolle-Wachtmeister was correct about Lund University’s possessing an object its keepers took to be a piece of Descartes. This object was probably what spurred Liljewalch to track the skull’s owners in the 1860s. In fact, the object is still there. In common with many other historical museums around Europe, the Historiska Museet in Lund is built around a long-ago bequest of somebody’s cabinet of curiosities. The museum has its touches of twenty-first-century museum studies—some breezy labeling and interactivity—but mainly it preserves its reassuringly old-fashioned origins. Kilian Stobaeus, a scientist who left his collection to Lund University in 1735 and in so doing founded what would become Europe’s first archaeological museum, had a particular fancy for tribal objects from all over the globe. It’s pleasantly jarring to encounter a sweeping collection of American Indian artifacts—arrows, baskets, jewelry, whole birch canoes—in the middle of Sweden. Hampus Cinthio, the historian on the staff who guided me through the collection, told me that American museums lust after these objects dating from decades before the American colonies fought their revolution, most of which are in an excellent state of preservation.

In the same room as the American Indian collection is a glass case that contains, among many other items, a portion of a human skull labeled in an antique hand “Cartesi döskalla 1691 N.6.” In a juxtaposition surely not coincidental, it sits beside a pair of embroidered purple slippers, so small they look like they would fit a doll, that once covered the feet of Queen Christina. The curved piece of bone, about the size of a cupped hand, is the object to which Trolle-Wachtmeister referred. It is also what Arckenholtz had referred to sixty years earlier as the “part [that] rests in the cabinet of the late M. Hägerflycht.” Liljewalch’s work showed that this bone had a history of its own, which closely parallels the history of the skull in Paris. The problem is that this skull portion—the left parietal bone, which forms the left side of the crown of the head—is not missing from the skull in Paris. Both cannot be relics of René Descartes.

In 1983, the curved parietal bone in the display case in Lund caught the attention of C. G. Ahlström, a professor of pathology at the university, and together with two colleagues, he conducted a detailed scientific and historical investigation of it. Besides reporting anatomical particularities—measurements, coloring, a slight indentation on the frontal part of the sutura sagittalis (the joint between the two parietal bones)—they noted the fact that the bone is whole, which is suggestive. The human skull is not a single mass but comprised of twenty-three separate bones, which are connected by the ridged joints called sutures. The Lund bone is complete, including its intricate sutures, which means it was not sawed off or broken. “The totally intact character of the bone indicates that it has been extracted from the cranium very carefully, probably by using the so-called blast method,” Ahlström and his colleagues reported. “With this method the cranium cavity is filled with dried peas or millet and is then filled with water and left to swell, whereby the various cranial bones slowly separate from each other through the increased intercranial pressure. The method, which is still in use, has been applied for a very long time and was used when preparing skulls from both humans and animals for natural cabinets during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.”

The curious picture that emerges, then, is of someone painstakingly pulling a skull apart in order to spread pieces around—to multiply relics. Presumably what Arckenholtz got was another piece of the same skull, which is now lost. Equally curious is the fact that, beginning with Hägerflycht in the mid-1700s, several of the successive owners of the complete skull also owned the skull piece. The records of Lund University indicate that the parietal bone entered its collection in 1780, as a gift from a woman whose maiden name was Stiernman. Stiernman was also the name of one of the owners of the complete skull, and it turns out that the donor was the wife of Bishop Olof Celsius and daughter of Anders Anton Stiernman. This together with the information from Arckenholtz—that in 1754 Hägerflycht had owned the skull piece—means that three successive owners of the complete skull (Hägerflycht, Stiernman, Celsius) also owned the separate parietal bone. There’s no telling what they might have had in mind. Perhaps the first, Hägerflycht, obtained one, which he took to be genuine, then happened upon the other, which he bought out of amusement, since one or the other piece was obviously not what it was purported to be. Or, since each by this time came with a pedigree, maybe he was hedging his bets in owning both, embellishing his cabinet of curiosities with a double curiosity. His collection, then, with its Descartes anomaly, would have passed in toto to Stiernman, and from him to Celsius. Then Celsius’s wife—who maybe was creeped out by the whole business—gave the parietal bone to the university, while the skull went to the paramour Fischerström and so onward.

In the original 1780 entry recording the parietal bone in the Lund collection its authenticity was taken for granted, but very quickly doubts crept in. If it had spent years beneath the ground, why was it so pearly white and unblemished? How could the skull of a man nearly fifty-four years of age be so papery thin? Keepers of the Lund collection gradually distanced themselves from claims that it had actually been part of Descartes’ skull. Hampus Cinthio, who gave me a tour of the collection, only chuckled at the notion.

A succession of Swedes ranging across the first century and a half of the modern era had, apparently, been taken in. Was it Planström’s doing? Or was he guilty only of swiping the true head and holding on to it as a personal charm? The parietal bone doesn’t appear in the historical record until a century after Descartes’ death. One hundred years is too big a curtain even to guess what may have gone on behind its heavy drape.

IN 1821, THE ACADEMY OF SCIENCES in Paris—which was by now used to voting up or down on the legitimacy of whole branches of science—had taken considerable time over a single skull, and there seemed to be a consensus. The chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet wrote to his friend Berzelius in Stockholm after the first meeting over the skull, telling him that “the Academy of Sciences received last Monday with a religious reverence and a vivid sensibility the present that you sent. We compared the skull with the portrait of Descartes and recognized a correspondence between them that, together with the proof that you have brought together, leaves no doubt of the personage to whom this head belonged.”

Berzelius wrote back thanking him for the information and then launching into a lengthy discussion of his work with alkaline sulfur and whether “in alkaline sulfur liquids the sulfuric acid forms before or after the addition of water.” In his reply, Berthollet noted that at a follow-up meeting of the academy, Delambre had done his best to discredit the skull as being that of Descartes. But “his observations seemed not well founded,” Berthollet observed.

The world’s greatest assembly of scientists had reached a conclusion, one that rested not on an ideal of certainty but on the modern notion of probability. They had applied their doubts to the very head that had introduced doubt as a tool for advancing knowledge. And in the end they gave the head a nod.