The plans of the opposing armies were quite naturally shaped by the natures of the commanding generals involved. Sherman, who had a firmer grasp of the realities of modern warfare than any of his contemporaries, contrasted sharply with Hood, still fond of the frontal assault and searching for military glory. The result was plans that literally marched their respective armies in different directions.

Sherman believed that the population of the South must bear responsibility for starting the war. Only by experiencing the realities of warfare would they come to realize the full horror of what they had unleashed. He would march his army of 60,000 men through Georgia, aiming for Savannah but going wherever it pleased them, and nobody would be able to resist, let alone stop them. In modern military parlance, Sherman would identify more with the term “shock and awe” than with “hearts and minds.”

The plan was simple, but that was its strength. Splitting the army into two wings, each of two corps, Sherman would be able to repeatedly threaten two targets at once. Confederate resistance, likely to be weak, would not be able to resist two movements at the same time and would have to choose where to defend. Sherman would then simply avoid the concentration of defensive strength and move on to threaten two more targets. The process would be repeated until he finally arrived at his destination, Savannah, where he would link up with US naval forces to resupply his army. The major military concern for Sherman was the cavalry force led by Wheeler, a highly capable commander. Sherman’s own cavalry, flamboyantly commanded by Kilpatrick, was tasked with screening the advancing columns and keeping Wheeler at bay.

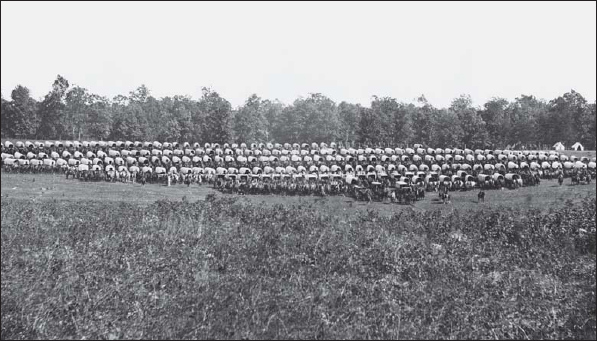

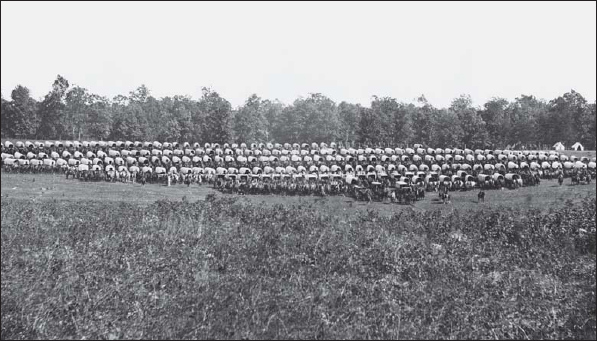

A park of about 200 wagons from the Eastern theater. Sherman’s army would march with 2,500 wagons for supplies, and a further 600 as ambulances. The intention was to keep the wagons stocked with food and live off the land, destroying anything the army did not need. (LOC, LC-B817-7268)

Equally important was the question of supplies. Sherman would take just 20 days’ rations with him in long, snaking wagon trains. His intention was to “forage liberally on the country,” with the dual aim of taking all his army needed and destroying all it did not. This destructive element of the march was at its very heart. Sherman had already admitted that he could keep his army under tight control and pay for whatever he needed, marching to the coast in an organized manner, but his offer to Governor Brown had been ignored. Now he would deliberately break the war-making ability of Georgia, and this included destroying buildings, livestock, and food supplies.

Each brigade on the march would provide organized foraging parties that would roam the flanks of the columns, meeting up again later in the day to unload their captured supplies. Inevitably, discipline could be lax in these parties and the “bummers” as they became known, would earn a reputation for vandalism and wanton destruction.

The possibility of the inhabitants of Georgia rising up against the invaders was a specter that haunted many in the North. It also had huge appeal for Southern leaders who had no other way of stopping the advance of Sherman’s men. Jefferson Davis referred to a “retreat from Moscow” scenario, which would see the Union invaders enjoy the same fate that befell Napoleon, but in warm, abundant Georgia this was never likely.

Sherman’s plans would undoubtedly have been complicated greatly had there been an enemy force of 40,000 threatening to fall on his rearguard at any moment. Hood had removed this element from the equation, but Sherman was still very much on his mind as he prepared to launch his invasion of Tennessee. Hood believed that he could take on the scattered Union forces in Tennessee one by one, eliminating them, taking the city of Nashville, and forcing Sherman to reverse course and pursue him. It was not entirely fanciful, because Union strength was dissipated in the state. Much would depend on the speed with which Hood moved and how quickly he could dispose of each section of the congregating forces. If Thomas managed to bring all his forces into Nashville he would have overwhelming strength.

After taking Nashville, Hood also had dreams of crossing the Ohio, spreading panic in the North and eventually linking up with Robert E. Lee in the East, combining to smash Grant and win the war for the South. Few military historians have seen any basis of reality in this scenario.