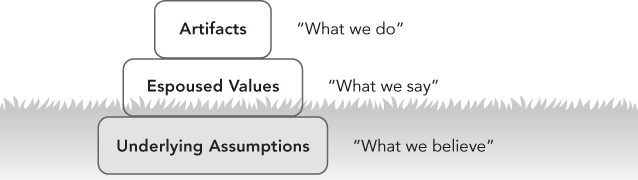

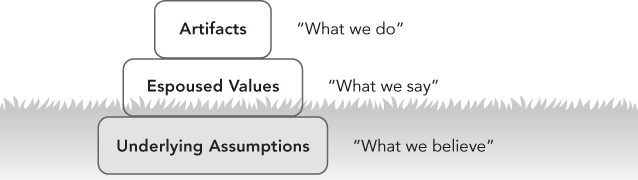

Figure 14.1 The Three Levels of Organizational Culture.

Things don't change. You change your way of looking, that's all.

—Carlos Castaneda

By now you've probably begun thinking differently about how your business intersects with society and are looking to find ways to improve your profitability while doing the right thing for your stakeholders. That's a great start. But becoming a sustainable enterprise isn't just a matter of placing an overlay on top of your conventional business thinking. It entails making a shift from an old way of thinking to a new one—a new set of beliefs and attitudes that subtly or dramatically alter everything you see and do.

Here's an analogy. At a certain point in the last two decades, many managers learned to see fellow employees as their customers. One day, your colleague was bothering you for something he needed to do his job, not yours; the next, that same person's satisfaction with you was part of your performance evaluation—so meeting his needs became part of your job, and rightly so. Seeing and treating your colleague as a customer required a change in your underlying attitude about his or her relative importance—perhaps from “She doesn't matter, so I'll get to it when I can,” to “I want her to be a satisfied customer, so I'd better do this right now and as well as I can.”

This change in viewpoint was a foundation of the quality movement, a transformation that vastly improved performance within companies. Similarly, the sustainability movement is now changing the way that executives, managers, and line employees relate to their jobs and to those inside and outside the organization, with consequences that will be even more far reaching. Sustainability demands a new perspective, one that is embedded in the culture of your company.

When conducting the organizational self-assessment we described in Chapter 7, you may have begun to notice aspects of the business that resist easy classification according to our “who you are, what you do, and how you do it” system. These are likely to include certain deep-rooted psychological and social realities that embody what is often called corporate culture.

Many business leaders talk about culture, but few have a systematic way of thinking about it, understanding it, or measuring it, let alone managing and changing it. The fact is that organizational culture is intangible, difficult to define precisely, and often resistant to change. Yet it is a vitally important influence on the health of the entire organization. Thus, understanding the role of corporate culture and the challenge of changing it is crucial for any leader who hopes to support an organization's movement toward greater sustainability. Any attempt to make your company more sustainable is likely to stall if it doesn't take into account your cultural strengths and weaknesses.

Yet if you are successful, the payoff can be great. Research has shown that a company with a culture that promotes sustainability is also more likely to be profitable, particularly in the long term. For example, the study by Eccles, Ioannou, and Serafeim that we cited in Chapter 2 as evidence of the stock market advantage enjoyed by sustainable businesses focused specifically on companies with a sustainability culture.1 So a lively awareness of the impact of your culture is a crucial element in launching any sustainability initiative.

Unfortunately, many companies have cultures that resist the transformation to sustainability. There are understandable reasons why this should be so.

Most successful companies were started before sustainability began to gain acceptance as an operating principle. The need to comply with laws and regulations has existed for a long time, but the idea that companies have an obligation to preserve and nurture the world has not. Almost all companies in the United States and other free-market countries were founded with the primary goal of maximizing profits while operating within the law. The measure of success was based on generally accepted accounting principles that measured financial gains in narrow terms based on a snapshot in time, which encouraged short-term profit maximization. Thus it's only natural that corporate culture at most companies has evolved to support profit maximization as the central objective. Sustainability, though growing rapidly in importance, is not yet accepted by many companies as essential to the pursuit of profit.

But even in companies that have found their sweet spots, opposition exists in terms of a resistant culture. Evidence of this can be seen when leaders require internal advocates to “prove” the business case for sustainability beyond a shadow of a doubt or demonstrate that it will produce a return on investment far higher than that required to justify other kinds of investments. In other cases, employees may not openly reject such goals as environmental stewardship or social responsibility—they may even pay lip service to them—but they quietly, perhaps even unconsciously, sabotage any efforts to change their business behaviors in order to pursue these goals.

In the long run, no company can continue to be profitable without becoming more sustainable, and no company can become sustainable without changing its culture to support sustainability. Of course, corporate culture change—though essential—is easier to describe than to create. Here are some of the most important principles to consider when you need to mount an effort to change your company's culture.

Edgar H. Schein, professor emeritus at the MIT Sloan School of Management and an authority on corporate culture, defines organizational culture as “a pattern of assumptions, values, and beliefs that shape individual and organizational behavior.”2

He goes on to identify three levels of culture, all of which must be examined if you hope to truly understand the factors that influence your organization's behavior.

The first level includes what Schein calls artifacts—a company's visible behaviors, organization, programs, processes, activities, and rituals. It's possible for a thoughtful observer to study these artifacts as they appear in the daily life of an organization and deduce from them certain basic conclusions about the corporate culture—the things it emphasizes or disregards, the ways resources are invested, the behaviors that are rewarded or discouraged, and so on.

The second level is made up of espoused values. These are revealed through explicit organizational messages (such as slogans, speeches, presentations, posters, and ads) as well as strategies, goals, and plans that embody values and serve to guide the organization. For example, when a company announces a program designed to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 30 percent, it is expressing the espoused value of minimizing environmental damage and helping to slow climate change.

The third level of culture is that of underlying assumptions, which Schein describes as “unconscious, taken for granted beliefs, perceptions, thoughts and feelings . . . [that are] the ultimate source of values and actions.” Because these assumptions are impossible to observe directly, they often go unrecognized, even by those within the organization.

You might summarize these three levels as doing, thinking, and believing, or, as your employees might say it, “what we do,” “what we say,” and “what we believe” (see Figure 14.1). For culture to change, all three levels need to change in a consistent, mutually supportive fashion.

Figure 14.1 The Three Levels of Organizational Culture.

To formulate a plan for shaping a company culture that is aligned with your sustainability efforts, you need to understand the current situation. Begin by asking, What is our organization's existing culture, and how well can it support an effort to make sustainability a high priority? Answering this question may require an in-depth analysis of the explicit and implicit values, goals, attitudes, and worldview that shape the behavior of employees, based on input from people throughout the organization.

Then ask: What are the gaps or impediments between our existing culture and the sustainable culture we want to attain? In particular, try to examine the unspoken assumptions about business, work, and the company mission that underlie your daily decision-making processes and those of the people you work with most closely. You may want to consider using employee focus groups, surveys, and informal conversations to reveal the kinds of hidden beliefs employees are harboring around sustainability.

Finally ask: How does our culture need to be changed to support a move toward greater sustainability? What must we do to alter our behaviors, activities, and programs (artifacts of corporate culture), our statements of espoused values, and, above all, the underlying assumptions we take for granted every day?

As we'll see, when corporate culture is resistant, even the best-intentioned and most heartfelt commitment to change is likely to prove ineffective. So any organization that is serious about traveling the path toward sustainability needs to study the cultural barriers that may stand in the way, and develop a meaningful plan for overcoming them.

Underlying assumptions that conflict with the values of sustainability are often the crucial factors that impede progress on environmental and social goals. A change initiative of any kind is unlikely to succeed if employees cling to conflicting underlying beliefs—and this is emphatically true of a change program aimed at movement toward sustainability. In our experience, identifying and systematically addressing underlying beliefs that impede progress is often the single most crucial step required in organizations that are trying to become more sustainable.

How do you go about uncovering and then challenging the underlying assumptions that impede your sustainability initiatives? This can be a challenging task. Employee surveys, focus groups, informal gatherings, one-on-one interviews—all can be helpful in ferreting out widespread beliefs that conflict with sustainability values.

When the leaders at American Electric Power (AEP) decided to transform their corporate culture into one that made worker safety the number-one priority, they first had to expose the underlying assumptions that hindered them. Through countless conversations with employees at every level, they gradually discovered that while workers heard the management speeches and “pep talks” urging adherence to safety procedures, they also believed that the company's real priority was to maximize speed and production. At the same time, workers also believed that safety was up to the individual and that accidents were inevitable—a matter more of luck than of safety rules violated. Assumptions like these were found to underlie many of the unsafe behaviors that AEP workers practiced.

It took time and consistent effort for AEP executives to gradually change these worker assumptions. One effective strategy was sharing the stories of individual AEP employees who had held risky jobs for decades without experiencing a single accident. The real-life examples set by these safety-minded individuals began to change the underlying belief that accidents are inevitable. The company started a program called My Brother's Keeper, which began to break down the assumption that safety was a personal matter. AEP leaders seized every opportunity to talk about the new assumptions about safety that they wanted to inculcate, and they publicly praised and rewarded employees who exemplified the changed approach. Employee training programs, evaluation systems, and financial incentives were aligned with the new emphasis on safety. Little by little, employee attitudes and the culture they supported began to change.

Over time, the effect of all these culture-shifting efforts has been significant. The number of accidents has fallen dramatically. As a result, AEP has saved over $30 million in worker's compensation and other costs between 2004 and 2011. It has also moved from the lowest quarter of the electric utility industry in safety to the top quarter, with the goal of reaching the top 10 percent by 2015.3

When you tackle culture change patiently and systematically, changes in underlying assumptions, values, and behavior will begin to reinforce one another. At AEP, as workers began to accept the assumption that accidents were not inevitable, some of them began to behave differently—for example, they started pointing out unsafe actions by their peers. As behaviors changed and safety results improved, an upward cycle of positive reinforcement was established. This kind of cycle is essential to a successful program of culture change. Doing, thinking, and believing are intimately related; the more energy you can bring to creating change at each of these levels, the greater your chances of shifting the entire culture to new ground.

Above all, accept the reality that culture change is complex, difficult, and slow. Don't expect the process to be completed in a matter of weeks or months. More often it involves change over years, or even generational evolution driven in part by the gradual process of employee turnover. Try not to be discouraged. Keep “working the culture” at every opportunity you get, expect resistance, and learn to celebrate small signs of improvement. Eventually you'll reach a tipping point at which positive changes begin to reinforce one another. Then and only then is it safe to anticipate victory in your company's version of “culture wars.”

In addition to a supportive culture, a number of specific supporting capabilities seem to be important for companies that hope to enjoy a prolonged period of sustainable growth. Capabilities are talents that are widely shared among the employees of the organization and have become integrated into the daily thinking, decision making, and behavior of the company. Many of the capabilities we refer to here are widely recognized as important tools for success for almost any twenty-first-century business. They include innovation, collaboration, long-term orientation, outward focus, interdependent thinking, learning, and adaptability.4

We could easily dedicate an entire book to discussing each of these valuable capabilities (and some fine books have been written on each of them). However, in the remainder of this chapter, we'll focus on just four capabilities that we view as particularly crucial in relationship to sustainability: collaboration, long-term orientation, interdependent thinking, and adaptability. All of these characteristics have appeared in the stories we've shared, but they're important enough to bear further emphasis and explanation.

Many of today's biggest business challenges are too complicated to be met by any one person or even a single team, no matter how talented. Instead, they require the shared efforts of many people and teams with a variety of experience, knowledge, skills, and tool sets—often from multiple departments or divisions and, in many cases, from outside the organization. And this applies particularly to sustainability, which often requires multiple disciplines and perspectives.

Consider, for example, the social challenge faced by packaged goods companies accused of promoting snacks that are exacerbating the childhood obesity crisis. Fixing this problem isn't a simple matter that can be handed off to a single department within a company. Instead, it will require the combined efforts of numerous professionals: chefs, cooks, nutritionists, flavor and texture specialists, and others capable of designing new, healthier products with the taste appeal of traditional snacks; manufacturing, packaging, and shipping experts who will know how to adapt existing processes to meet new requirements (such as maintaining freshness with less use of preservatives); and perhaps most of all, marketing and advertising experts—including psychologists and anthropologists of food—who can devise ways of convincing kids to fall in love with the new goodies.

This irreducible complexity is one reason that sustainability is highly focused on working cooperatively with often demanding stakeholders: customers, suppliers, advocacy organizations, regulators, potential litigants, the news media—and your own employees, of course. The ability and willingness to learn from anyone who may be able to help address a crucial challenge are essential elements in any sustainability program.

Recognizing this reality, many companies have started their sustainability initiatives by creating committees near the top of the organization to steer and coordinate the effort. A committee structure creates an immediate need to collaborate, at least among the members; to share ideas and information; and, often, to establish common objectives, a vision, and a shared purpose. Getting committee members from various departments who may not regularly work together to discuss the company's activities in terms of the TBL can be a powerful catalyst, not only for creative and innovative thinking but for focused and effective collaboration.

Unfortunately, impediments to collaboration exist in many organizations; strong-willed departmental managers intent on building fiefdoms, defending turf, or maintaining what they consider necessary levels of autonomy and independence may resist efforts to encourage openness and teamwork. Managers engaged in intense feuds or rivalries with their peers in other divisions are unlikely to reform their behavior merely in response to calls for collaboration. Recognizing the existence of such impediments to collaboration and patiently, painstakingly working to reform the underlying attitudes that produce them will be a crucial element in the culture change program of many companies.

Understanding sustainability means seeing how the corporate world—and your industry and company in particular—works within the larger social and natural world. This is big-picture thinking: How is the world enriched or diminished by your products or services? What are your major impacts on society, and how does your overall business strategy reflect those impacts? How are stakeholders included in your decision making, and how are the costs and benefits of what you do shared among them? How do you take into account the needs of society and of future generations? Leaders of sustainable businesses will be able to answer future-oriented questions like these, and doing so requires the ability to think beyond the next quarter or two and instead to articulate a vision for the long-term future of your company.

Many companies find it useful to summarize their sustainability vision or mission in a sentence or two. DuPont's vision, for example, is to be “the world's most dynamic science company, creating sustainable solutions essential to a better, safer, and healthier life for people everywhere.” PepsiCo's is to “continually improve all aspects of the world in which we operate—environmental, social, economic—creating a better tomorrow than today.” Caterpillar envisions “a world in which all people's basic requirements—such as shelter, clean water, sanitation and reliable power—are fulfilled in a way that sustains our environment,” and the company has taken as its mission “to enable economic growth through infrastructure and energy development, and to provide solutions that protect people and preserve the planet.”

It's valuable to put your vision down on paper. A brief, well-crafted statement provides employees and stakeholders with a set of clear, broadly stated principles against which your efforts can be measured and that can be used to develop more specific guidelines, including your strategy, goals, and key performance indicators.

But developing a vision that includes sustainability is more than catchy words. It requires you to see how to incorporate the TBL and its emphasis on long-term environmental, social, and economic prosperity into every decision made throughout the organization, and to think about how it takes hold at the operating level.

Many of the stories we've told in this book involve trade-offs between short-term costs and long-term benefits. The word sustainability itself implies long-term thinking, because it focuses on how your company can survive and thrive in the long term, and includes consideration of future generations. It's a time frame that most American businesses—unlike many of their counterparts in Asia and Europe—aren't used to, but one that is increasingly important to businesses today.

In recent years, millions of people in the United States and around the world have been gradually coming to recognize that we live in an age and on a planet of genuine limits, and that as world population approaches nine billion, there are some problems we simply can't solve fast enough. And as this happens, the wisdom of longer-term thinking is becoming more apparent.

Much will have to change for long-term thinking to supplant quarter-by-quarter thinking in American business. U.S. business leaders need to learn from their counterparts in Asia and Europe the wisdom of planning for decades in the future, not just the next three months. Wall Street will need to learn to reward long-term growth, not just beating expectations for a quarter or a year. This will take time—but it will happen. We want to be living together here on planet Earth for a long time, and to do so, we will eventually have to change our way of looking at things.

A natural corollary of the capabilities we've already described is interdependent thinking—the ability to consider the direct and indirect results of your actions and how those might cause consequences for others. Working closely with stakeholders is one way to help see and understand more of the nonobvious connections and linkages. Without stakeholder feedback, it's often far easier, for individuals and for organizations, to see the positive consequences of their actions and to overlook or ignore the negative ones.

Here's a striking example. In 2011, Oxfam America, the anti-poverty NGO, worked with beverage makers Coca-Cola and SABMiller to examine the impact of their operations on poverty in Zambia and El Salvador. Although most companies understand the connection between their organizations and economic growth, far fewer realize that they can inadvertently create poverty through their actions. A small detail from the Oxfam America study illustrates the point:

For a number of years, a pipe on the outside of the Zambian Breweries plant [a subsidiary of SABMiller] was leaking treated wastewater. Community members began to use this water on their subsistence farm plots. When Zambian Breweries later installed upgrades to its water efficiency processes, it repaired the pipe and the water supply was shut off. As a result of the repair, the community no longer had access to the water that they had been using from the leaking pipe. Many community members had depended on this water to grow maize and bananas for their families. A community leader interviewed for this study stated that Zambian Breweries did not consult with the local community prior to fixing the pipe, thereby inadvertently depriving the community of an important water supply.5

In creating more wealth for the company (and protecting the environment), Zambian Breweries unintentionally caused economic harm to many specific members of the community.

Developing the habit of interdependent thinking empowers organizations to identify unknown but potentially important cause-and-effect relationships—positive and negative—between their behaviors and the communities in which they operate. And this is a habit that can be learned. As we saw in Chapter 11, Gap's employee training program now includes a deliberate effort to encourage purchasing managers to anticipate and plan for the unintended consequences of their decisions. The goal is to minimize the social and environmental harms—and maximize the benefits—caused by the interdependent relationships in which Gap is inextricably bound.

Interdependent thinking is closely linked to the reality that sustainable businesses must recognize and respond to the demands of multiple stakeholders, somehow balancing the needs and wants of shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, communities, interest groups, and others with a legitimate interest in the organization's impacts, even if those impacts turn out to be indirect. Thus the capacity for interdependent thinking is close to the heart of sustainability. In fact, it's difficult to imagine one without the other.

The sustainable organization is, above all, an adaptive and agile one—one that recognizes, understands, prioritizes, and responds quickly to changes in its natural, social, and economic environment. When an organization loses the ability to adapt, it can't stay healthy for long.

Working on being able to thrive under future environmental and social conditions, while at the same time trying to optimize their own impacts today, is a high priority for sustainable organizations. Many are already dealing with such future-oriented challenges as climate change, eventual limits on the use of fossil fuels, population growth, and urbanization of the developing world.

Companies that lack the capacity for adaptability often develop sustainability programs only when a dramatic event forces them to act—and even then, they are often slow to respond effectively. Consider, for example, the relatively long reaction time of Google and Yahoo to the emergence of political censorship issues in China as key concerns of human rights activists.

Nike, for another example, first reacted to news reports about the abuse of child labor in their supplier factories with a dismissive, “Those aren't Nike facilities or Nike employees, so that isn't our problem.” The resulting firestorm was exacerbated by Nike's lack of nimbleness. (As we've seen, Nike awoke in time to make the necessary adjustments and has, to its credit, worked hard to become a leader in managing the social and environmental challenges of a global supply chain.)

In a world where outside circumstances are constantly evolving in ways that are difficult to predict, companies should strive to operate according to the maxim, “Change before you get changed.” Adaptability and agility give you the capacity to do just that.

Modifying your company's culture and working to develop or strengthen specific organizational capabilities represent two essential systemic responses to the challenges of sustainability. But there are signs that future trends in the relationship among business, the environment, and society may demand even more far-reaching changes than these—changes that may affect the very nature of the corporation. In the final chapter of this book, we'll examine these changes.

1 Robert G. Eccles, Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim, “The Impact of a Corporate Culture of Sustainability on Corporate Behavior and Performance,” Harvard Business School Working Paper no. 12-035, Working Knowledge, November 14, 2011.

2 Edgar H. Schein, The Corporate Culture Survival Guide, New and Revised Edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009), p. 4.

3 Andrew W. Savitz and Karl Weber, Talent, Transformation, and the Triple Bottom Line: How Companies Can Leverage Human Resources to Achieve Sustainable Growth (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2013).

4 For a more detailed discussion of capabilities that underlie sustainability, see Talent, Transformation, and the Triple Bottom Line, ch. 8, from which the discussion in this chapter is, in part, adapted.

5 Oxfam America, Coca-Cola Company, and SABMiller, Exploring the Links Between International Business and Poverty Reduction: The Coca-Cola/SABMiller Value Chain Impacts in Zambia and El Salvador, December 2011, http://www.oxfamamerica.org/files/coca-cola-sab-miller-poverty-footprint-dec-2011.pdf. p. 68.