FIVE

Discerning Faithfulness in Exile

The challenge I feel every day pastoring in Portland, Oregon, is discerning what faithfulness to Jesus looks like now. Portland is a city that is proud of being progressive. Like those in many urban centers, people in Portland pride themselves on their liberal politics, biking through inches of rain to save the environment, and being spiritually open-minded but never religious, an open-mindedness that Ravi Zacharias would liken to the sewer rejecting nothing and accepting everything,1 everything but Christianity for the most part. Zacharias shows the implicit problem with being open to everything. Any coherent view of reality will automatically reject certain things.

Culture Makes Disciples

Portland is great at making disciples. All cultures that have defining characteristics are discipling cultures. The power of the cultural values leads people to conform to those values, and that can be seen in how they think, act, and believe. The TV show Portlandia, a spoof of Portlanders, is only somewhat of an exaggeration. A good portion of people in Portland don’t really get the joke, because in Portland the parody is the reality—at least in some places.

Portland is, in a way, my exile. It is my home, but it is not my home at the same time. Home for me is California, where the sun comes out and people don’t measure the yearly rainfall using fifty-gallon barrels. At nineteen, I left that sunny state, and I never went back. Since then, for all but a short stint in a small town to the east, Portland has been my home.

With its naked bike rides boasting over ten thousand participants yearly and people who are more pro-dog than pro-life, this is the place where God put me, and this is the place where thousands of Jesus followers are finding a way toward faithfulness even as a dominant culture remains unwelcoming of such an endeavor.

While not every city will go the way of Portland, the general ethos of my city is becoming the norm in urban centers. The famous bumper sticker “Keep Portland Weird” is losing its punch as weird becomes the new normal in most cities.

Finding Our Way to Faithfulness

Finding our way to faithfulness presents a challenge that we as the church in our city have not exactly figured out. But we have learned a lot in striving toward Christ and his calling to be the people of God who bear witness to Jesus in his life, death, resurrection, and present reign. That’s a mouthful, and the complexities of doing that are inherent in the sentence itself. The task is no small thing.

But this is the task that Jesus gave the church, and it is a discipling task. The question we are wrestling with in our cultural moment, How are we to be the people of God now? is one that Jesus’s followers in more progressively liberal cities have been wrestling with for a long time, and one God’s people have been working out since their inception in Abraham’s blessing. How did they do it? What can we learn from how they navigated their moment?

Contextualizing the Gospel

Lesslie Newbigin was a British theologian and missiologist who served most of his career as a missionary in India. Newbigin thought deeply about the interplay between the gospel, the church, and culture. When he returned to the United Kingdom, he was shocked by the ways in which the church of the West had embraced modernity, with its scientific rationalism, without questioning if modernity itself was a biblical worldview.

Newbigin made it his mission to recover the missionary identity of the church in the West, and his writings have influenced countless missionaries, theologians, and pastors over the last several decades.

One of Newbigin’s most profound contributions was rescuing the gospel from culture. Newbigin argued that the gospel is essentially a-cultural, meaning it does not exist with a culture tied to it but instead enters a given place and contextualizes itself to that culture. It is a living proclamation that when preached and lived out within a culture will critique and transform the people of that place. A new entity is then born and established—the church.

Ours is a time when the gospel is not new, and the church in America dates back to when the Pilgrims settled on our soil. This history is no small matter when trying to understand the current missionary task of the church. A familiarity with Christianity and the presence of church buildings in every community lead to the assumption that the church and its message have been here and done that. The problem with this assumption is that while the roots of the church have grown deep in the American soil, that soil has shifted, and the roots have lost their footing. As a result, we need a new way of being the people of God in this moment. The way, however, is as old as the message we offer. It is the way of mission. The church is always and everywhere tasked to bring the message of Jesus in fresh ways to the culture in which it finds itself. We must continue to try to understand our new place and understand what makes the message of Christ good news to those who are building their lives here.

This means the church must learn to navigate its relationship to the culture it finds itself in at this moment. There is no command for the church to recover yesterday or the day before. The gospel is public truth for this moment and every moment to come, and as a result, we must be a public people who embody this message in public spaces. We are in an interdependent relationship with the culture in which we live.

I can hear the protest going on in some of your minds. We are not a part of the culture. We have been saved out of the culture. There is no interdependence between the church and the culture.

Let me ask you this: Where did you buy your groceries this week? What did you use to purchase them? How did you get to the grocery store? How did you get the money for the groceries? Where did you bring the groceries once you bought them?

Everything we do happens within the culture in which we live. From the way we dress to the jobs we go to, everything in our lives takes place within a given space on the map. This is also the place we practice our faith in Christ. Any other understanding is an illusion. If you work and take a paycheck, you shop and buy the culture’s wares, how can you honestly believe you don’t have an interdependent relationship with the culture?

We all live within culture, and therefore we must pay attention to how we as the community of God’s people understand our place within culture. We also need a fresh perspective of how to take the gospel into this place we call home.

The problems Newbigin saw upon his return were many. In his estimation, the church was losing or had lost the true sense of what it means to be the people of God and in doing so was at risk of replacing the gospel with its own culturally shaped understandings of God, the Scriptures, the church, and faith. He called this a new form of gnosticism.

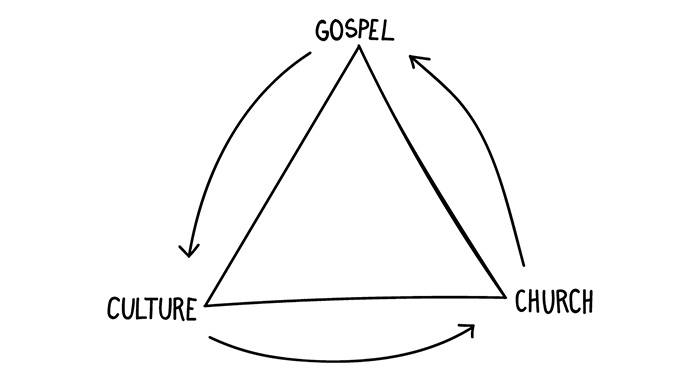

In his attempt to define the interplay between the gospel, the church, and culture, Newbigin and those who followed him, such as the Church Between Gospel and Culture Network, created what has become known as the Newbigin Triangle (see the figure on the next page). As we examine it, we can see how the church is meant to interact with the gospel and culture in a way that allows it to remain faithful to the gospel and redemptive in its relationship to the place in which it lives.

If we follow the arrows, they help us understand how the gospel travels. As the gospel is preached and displayed in a given culture, people contextualize it for that culture. In doing this, Jesus’s life, death, resurrection, and ascension are communicated in word and deed through the power of the Holy Spirit.

Contextualization looks different in each culture in which the gospel is announced, or at least it should. We see this in the book of Acts. After Jesus’s ascension, Peter, full of the Holy Spirit, stood up and preached his first message to a mostly Jewish audience. Using the Psalms and the Prophets, Peter communicated the gospel in the language and the cultural context of the Jewish people. While they listened and the Spirit worked on their hearts, they heard that Jesus was the fulfillment of the Davidic promise and that the prophets of old foretold his coming (Acts 2).

Fast-forward to Acts 17, and we find Paul in Athens on Mars Hill. The Athenians were a very different crowd, both in their understanding of themselves and in their faith and concepts of God. Paul didn’t take them back to the Old Testament and lead them down a path through the Prophets. Instead, he found an idol to an unknown God. The city was full of idols, and Paul took note of that. He told them that he could see they were very religious/spiritual people. He quoted Cretan poetry to them, which they were familiar with. Then he told them who the unknown God was: the risen Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

Think about the radical difference between Peter’s preaching and Paul’s. Paul used an idol to lead people to Jesus. If Peter had done that, the crowd would have rioted. The Jewish people were well versed in the sin of idolatry and idol worship. To make a leap from an idol to the Messiah would have seemed to them like heresy.

But this was not the case for Paul. Paul was free to contextualize the gospel to this very different crowd. He discerned who they were, what they valued, and how best to tell them about Jesus. He was a rabbi turned disciple who had been raised on the Jewish Scriptures. He knew what he was doing, and at the same time, he had the freedom in the Spirit to communicate to the people in their cultural moment the timeless message of Christ that is never owned by any one culture.

Using Windows of Redemption and Opposition

Every culture on earth has what I call windows of redemption and windows of opposition. Every culture values things that are good, true, and beautiful, and through these windows of redemption, we can find ways to talk about Jesus. For Peter, the window was the Jewish crowd’s religious history and familiarity with the poets and the prophets of the Old Testament. For Paul, it was the religious climate of Athens. Even though the religious climate had resulted in idol worship, Paul could tap into the people’s hunger for transcendence to tell them about the true God.

In Portland, a redemptive window may be the arts, where people place a deep value on creativity. By engaging the arts as the people of God, we can join a conversation on creativity but motivated by our faith and theology. We create not simply for self-expression but because we were created by a God who is endlessly creative.

Another window may be environmental advocacy. People in Portland care about the environment, and as followers of Jesus, we believe that we have been commissioned by God to steward his creation. This value that we hold in common for very different reasons may be a way for us to begin a conversation about God.

Portland also has many vulnerable people, from victims of sex trafficking to foster children to homeless families and individuals living on our streets. When we follow Jesus’s command to care for the widows and the orphans and the least of these, we often work shoulder to shoulder with civic leaders and other individuals who have an equal concern for these populations in our city. As a result, we find ourselves in relationships with people who, though they have different motives, care about the things God cares about. As the church enters these spaces, we have a powerful ministry of presence and can use the open doors of proclamation given to us.

Every culture values something that God calls good or true or beautiful, and those are the places where that culture is open to the redemptive possibilities that Jesus brings. No culture lacks these windows of redemption. We all have been created in the image of God, and because of that image-bearing reality, we are wired on the inside for the good and true and beautiful because those things reflect the nature and character of God. They get twisted, marred, and perverted, but they are there underneath the surface if we just take the time to look.

Through these windows of redemption, we can engage the culture in its own space and through its own language and values. We can establish relationships while we follow the Holy Spirit into his work of making Jesus known. We are participants and mouthpieces seeking to live lives congruent to what we say we believe.

There are also windows of opposition in every culture. These are the values, beliefs, and practices that are at odds with Jesus and the gospel. Seeing them requires that we discern good and evil. Then we must thoughtfully engage our neighbors concerning issues that we disagree on. Both Peter and Paul, though differing in their presentation of the gospel, called for people to repent. That word means “to turn.” The turn required in every culture is from self to Jesus as King over all things.

As we try to discern what the windows of opposition are, we also need to identify what they are not. We must be careful to separate what is opposed to Jesus and the gospel and what is simply opposed to our church culture or rules that exist within the larger culture. An example of this can be seen in the Western missionary movement. When the church in the West sent missionaries into the world a hundred or so years ago, they often brought their cultural values with them, and too often they imposed those values on native cultures. Those values included manifest destiny, which claimed that God wanted to give Westerners the land of the Native Americans. It also involved teaching African children to sing hymns in Latin, dress in Western fashions of the day, and play the violin. Those were cultural impositions, not gospel contextualization.

If we look closer at these two examples, we can learn how things got muddled. In manifest destiny, the desire to conquer the new world was inextricably tied to God, who was believed to be granting white Americans the authority to take land and convert those whom they considered savages—the Native Americans. The call to proclaim the good news was mixed with the imperial call to conquer new lands, which perverted the first calling. By wedding God and country into one overarching belief system or worldview, Christians opened the door to committing atrocities in the name of God for the sake of country. If they had seen the New World through the lens of biblical missionary mandates, it’s possible that the connection between gospel proclamation and conquering land would have been broken and the native people’s way of life preserved. The gospel could have fit into Native American culture, and Jesus could have been worshiped and proclaimed in the language, music, and customs of the native peoples, though some of those customs would have needed to be transformed to reflect faith in Christ. In short, the church could have grown in its diversity and understanding of God through the expression of faith practiced by native cultures in their own cultural traditions. The church would have seen a reflection of Jesus redeeming and transforming people as they were in their culture, not as another culture demanded them to be.

This doesn’t mean that certain values and customs should not be critiqued and challenged. How does a person love their neighbor in a culture that teaches them it’s okay to eat their neighbor? Cannibals need to be converted to neighborly love in their culture. And in a consumer culture, we have our own ways of cannibalizing our neighbors instead of loving them. The gospel has a strong critique of every culture because every culture in some way is a godless culture that requires Jesus’s redemption and transformation.

Confronting windows of opposition within a culture can be very challenging. If we go to war against the people who believe certain things are not sin, we misrepresent Jesus’s love and compassion to them. But if we just ignore those issues, we misrepresent Jesus’s truth and authority to them. It is the tightrope we walk. How do we do both faithfully?

This is why being faithful to Jesus requires discernment, because Jesus loves people enough to die for them, and he is the hope of the world. We hold this truth carefully and seek to carry it faithfully, so that those who hear and see the gospel that we announce, see and hear it accurately represented as “Good News.” So how do we do this well? First, we need to understand how the gospel interacts with the church and culture.

Church Culture Is Not the Gospel

For too long, we have held up the culture of the church, instead of the gospel of Jesus, as the plumb line for what is good or bad.

Once I led a group of rural students on a trip to the city for a concert. Along the way, we stopped at a movie, and in the evening, a group of us played cards. After the trip, one of the leaders confronted me, and I found out that he had been raised to believe that both going to the movies and playing cards were taboo for anyone who follows Jesus. I was not raised in the church. I had never even heard of those rules. The kids who were with us hadn’t either. The card game could hardly have been referred to as gambling, and the movie was definitely not R rated. The clash that was occurring was over what a Christian can and cannot do.

The process we had to work through was a matter of discernment. What was it about Jesus and his gospel, or the whole of Scripture for that matter, that would make rules like that necessary? After a few meetings and several conversations, we identified that those rules that he felt were being broken were not Jesus’s rules. They were a part of the church culture he had been raised in and had been given a type of divine authority by the leaders of his church. But they had no basis in the gospel.

If anyone from my family heard that Jesus loved them and never wanted them to play cards or go to the movies again, only part of that would sound like good news.

We have built walls of self-protection around us that are man-made, not God ordained. The mistake here is believing that sin comes from outside of us when Jesus told us that it comes from inside of us. We can’t build fences tall enough to keep sin from showing up in our own hearts (see Mark 7:20). The example above is from church culture of the late 1950s and ’60s. The types of rules have changed in terms of the actual dos and don’ts, but they are still values of the church’s moralistic culture, not the gospel of Jesus.

Today the rules might be different. In some places, like Portland, the pendulum has swung. If you’re a “liberated” Christian, then drinking a microbrewed IPA is a freedom second only to salvation! The idea that you would give that up to help a person who has struggled with alcoholism might feel like an infringement on your right to imbibe. The freedom to drink can become a sign we wave to show we aren’t stuffy, old-school fundamentalists, assuming anyone who doesn’t share that freedom is less free, less spiritual, just less than . . . us.

The sad reality is that most followers of Jesus don’t know how to discern what is sin and what is life-giving because so much of their discipling has been focused on personal conduct and not spiritual discernment.

One man who came to Christ in his midtwenties described it this way: “After I met Jesus, most people I met were really worried about who I was sleeping with, but no one asked me about my money and how I spent it.” He recognized that in the culture of the church, sexual sin is at the top of the list, but the sins of greed and overconsumption rarely get mentioned. Jesus wants our entire lives. This means he wants not only our sexual fidelity but also our generosity as we use our money for his kingdom instead of to serve ourselves.

To navigate the road of faithfulness, we need to be ruthless with ourselves and allow the whole of Jesus’s teaching, not just what a certain church deems good or bad, to bring us to conviction and transformation. We need to hear the gospel in a fresh way for ourselves. The gospel is as much for the church as it is for the world. If we are going to be faithful in exile, then we will need ongoing conversion. That is what I want to talk about next.