Di più nei giovani scrittori venuti su con la “Voce” e con la “Ronda” c’era pure una bramosia di ritrovarsi di comunicarsi proposte e speranze tenendo l’occhio all’estero ma cercando proprio e oneste cammini.

What’s more among the young writers who grew up with la “Voce” and with la “Ronda” there was also a longing to find oneself communicating ideas and hopes keeping an eye abroad but also searching for the right and honest path.

▸ Carlo Linati, “Di un ritrovo della intelligenza e di una rivista letteraria”

I

IN ITALIA, ALL’ESTERO: in Italy, and abroad. This phrase is familiar enough to anyone who has had to navigate the Italian postal system, and it was one originally intended to distinguish between destinations for foreign and domestic mail. Little magazine editors at the beginning of the twentieth century were soon attaching this phrase to their subscription notices, and before long “all’estero” was a subtle way for them to advertise international range, taste, and connectivity. More than implying that a particular title was simply going to readers abroad, “all’estero” was there to signify that the transmission was also happening in reverse with foreign influences, ideas, and writers coming back in. For that reason, “in Italia” was paradoxically a way for some little magazines to acknowledge that they were benefiting from “un apertura,” or an opening, that made it impossible to close Italy off from within.

In the years immediately preceding World War I, there was enough sympathy among European nations to encourage dreams of a shared literary culture that could be effectively mediated by little magazines. All of that changed, however, once the war erupted, and by 1918, when a tentative peace was finally achieved, there was a sense that Italy had lost its way, its path to modernity blocked by years of senseless destruction. In 1919, Vincenzo Cardarelli founded

La ronda in Rome precisely to jumpstart the process of a “ritorno all’ordine” (return to order), and in the opening editorial, he gave readers a pretty bleak diagnosis of the situation: “Ritardata la nostra modernità di più di un mezzo secolo a causa di avvenimenti storici che non é il caso di discutere e rifatta l’Italia grettamente nazionalistica e provinciale nelle arti, la nostra letteratura intraducibile è poco valida ad attestare della nostra universalità tra le nazioni contemporanee, forse è giusto per noi il momento di uscire e di farci intendere in questo contagioso crepuscolo della civiltà moderna europea” (Having delayed our modernity by more than half a century because of historic events not worth discussing further and having remade an Italy narrowly nationalistic and provincial in the arts, our untranslatable literature is of little use to prove our universality between contemporary nations, perhaps it’s the right moment for us to leave and make ourselves understood in this contagious twilight of modern European civilization).

1 As Cardarelli and his more liberal-minded compatriots believed, the hypernationalization that began with unification and reached fever pitch during the war brought with it an increased provincialization and isolation of Italy’s culture. Any hope in the future for a more meaningful engagement with developments abroad, then, depended on the production of a modern literature and art that could be translated and exported elsewhere.

2So began what the Milanese critic, writer, and translator Carlo Linati described as a process of keeping “l’occhio all’estero” (an eye abroad). The ability and inability to keep an “eye abroad” defined a fraught Italian cultural field in the period between the world wars and came to include books and writers, which once seemed, as Enzo Ferrieri, the editor of

Il convegno put it, “troppo lontano da noi” (too far away from us).

3 In the “primo dopoguerra” (the first postwar period), different groups of artists, writers, and intellectuals, many of them organized by city or region, were eager to deprovincialize Italy, but it was a process that involved finding innovative ways to generate a national literature, art, and criticism capable of engaging with the best of what could be found in other European nations. The strategies, as I’ll explain in what follows, were varied, but together they marked a pivotal moment in a cultural awakening process driven by the desire to make Italian literature and culture both modern and European.

The years 1919 to 1921 represent a brief, utopian moment in the history of modern Italian literature, art, and criticism before the Fascist takeover marked by Mussolini’s March on Rome. Magazines like

La ronda and

Il convegno were started precisely in order to provide an outlet for international communication involving groups of solitary intellectuals “diffusa in tutte le provincie della nostra letteratura” (spread out across all the provinces of our literature).

4 By 1919, Italy already had an established magazine tradition that had witnessed the arrival of titles as varied as Benedetto Croce’s

La critica, Giuseppe Prezzolini’s

La voce, Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici’s

Lacerba, F. T. Marinetti’s

Poesia, and Piero Gobetti’s

Energie nove. But even in this abbreviated list, it’s possible to see just how elastic the category of the

rivista could be. The English phrase

little magazine, in fact, fails to define adequately the print medium that appeared in Italy during these years. In most cases, these “magazines” were not even “little” and could look more like newspapers, notebooks, or oversize exhibition catalogues than literary or general culture reviews.

Rivista, then, was the preferred term, and it could refer at once to the staid academic periodical, an avant-garde four-column folio, a monthly devoted entirely to poetry, and a political student newspaper.

Modern Italian culture before and during Fascism was radically defined by this “ventura delle riviste” (destiny of

riviste), and the cultural landscape was so littered with titles that the Italian twentieth century earned the designation “il secolo delle riviste” (the century of

riviste).5 What’s interesting about this particular history of the medium is not just the number of

riviste published in cities and towns across Italy: it was the way they were adapted by liberal democrats, academics, aesthetes, Futurists, Communists, and Fascists alike to generate and protect different versions of an Italian culture that was very much in flux. In spite of the many ideological programs around which these various groups coalesced, each of them believed that the

rivista would play an integral role in cultural production, a tool for communication with the power to consolidate groups by connecting individuals.

The effect of Fascism on the development of

riviste across Italy cannot be underestimated.

6 Fascist intellectuals and writers adapted it as a tool for propaganda, using it to continue defining a culture that was gradually developing alongside a political program.

7 Already by 1924 with Mussolini’s

decreto legge, the opportunity for explicit pofitical opposition in periodicals and newspapers through articles, notes, comments, titles, illustrations, or vignettes was prohibited.

8 For that reason, editors who did not pledge their allegiance to the Partito Nazionale Fascista, or PNF, had three choices: they could close down, self-censor, or face suppression. During the first phase of consolidation, the Fascists flaunted their power by openly crushing dissent in the press, and the suppression and violence that followed came to influence how the anti-Fascist

riviste would select, organize, omit, and conceal material in the following decades.

Gobetti’s

Il Baretti (named after the eighteenth-century author and model of free speech Giuseppe Baretti) was one of the most famous casualties in this early struggle against Fascism. First published in Turin in December 1924,

Il Baretti began as a four-page literary supplement to the political weekly

La rivoluzione liberale, and throughout its two-year run, it was intended to unite the liberal opposition (including Populists, Republicans, Socialists, Communists, and Unitarians) by connecting Italy with Europe. Considering that one of the most successful and longest running Fascist magazines had the title

Antieuropa (1929-1943), it’s easy to see that this was no easy task for Gobetti or anyone else. Europe was symbolic of an enduring liberal democratic ideal that many Fascists associated with antinationalism, and it was connected with a sickness that Marinetti called “esterofilia.”

9 But for Gobetti and his collaborators, any chance for cultural renewal required the direct engagement with a contemporary literary scene abroad, one that could provide a refreshing counterpoint to the more restrictive, and indeed more provincial, Fascist cultural program that was in the process of being formed at home.

Il Baretti’s political agenda was communicated more subtly through Gobetti’s choice of writers, critics, and translators. Within its fifty-three issues, there appeared reviews, essays, and translations of works by the Surrealists and Dadaists—James Joyce, Rainer Marie Rilke, Virginia Woolf, André Gide, Paul Valéry, Stephane Mallarmé, Marcel Proust, and Charles Baudelaire—with special issues dedicated to contemporary French literature and German theater. This embrace of current literary developments and critical conversations abroad was certainly intended as an antidote to a nationally defined program, but equally important, it enabled Italian writers and critics to position themselves within and against non-Fascist, European examples. In doing so, however, they were not automatically united across the country. In fact, Ferrieri argued that these scattered pockets of resistance, though certainly crucial to the loose formation of an anti-Fascist intellectual network, tended to have a more regional focus and lacked any significant national coordination.

10 Antonio Gramsci held a similar opinion. The regional dispersal of

riviste was problematic, he believed, because it reduced the possibility of establishing any unified front and would not allow for the broader organization within the nation-based cultural institutions, the kind that could move beyond the “quadri chiusi” (closed cadres) to the masses.

11

Nevertheless, as the Fascist regime became more repressive throughout the 1920s, including the beating of Gobetti by Mussolini’s thugs, ending with his death in exile, these anti-Fascist

riviste kept appearing. Ferrieri’s

Il convegno, though often excluded from the histories of the

riviste, was one of the more resilient titles, and it managed to last for two decades.

12 Part of

Il convegno’s success stemmed from Ferrieri’s ability to adapt, organizing cultural activities in Milan, while refusing to become part of the state’s cultural apparatus. In fact, the writers and critics who appeared in its pages and frequented the events organized by the “Circolo del Convegno” counted on the fact that the regime was largely ignorant about contemporary literary and artistic developments abroad. Had they known just who was coming into Italy via Milan, Ferrieri was convinced that his entire operation would have been “immediatamente stroncata” (immediately crushed).

13Still, it wasn’t just who was crossing the border into Italy that mattered; it was how. Editors like Gobetti, Ferrieri, and Alberto Carocci realized that the

rivista was incredibly effective as an oppositional medium precisely because it could assume the form of an “anthology.” In the 1920s, in particular, the production of the so-called

rivista-antologia represented a more coded refusal to follow a single, and indeed less tolerant, cultural program. Instead of editors using the manifesto to announce their intentions, they tacked on open-ended statements about who and what would appear in their pages. Using the

antologia as an anti-Fascist device was Gobetti’s idea. Though warned by Edoardo Persico that the absence of an explicit editorial program would make

Il Baretti “un invertebrato, incapace di tener stretti perfino i redattori” (spineless, unable even to keep the editors in line), Gobetti refused to give in. By doing so, he created an inclusive space capable of combining not just different national literatures but also critical works that were often ideologically opposed to one another. With carefully curated eclecticism,

Il Baretti became, as Gobetti explained in an advertisement for the first issue, “il centro di raccolta della nuova letteratura e darà un bell’esempio di rivista indipendente aperta agli spiriti più nuovi e più audaci, europea nei risultati e nell’ ispirazione” (the collection center of the new literature, and it will offer a perfect example of an independent

rivista open to newer and bolder spirits, European in its accomplishments and inspiration).

14Open, independent, new, bold, European in spirit and inspiration: these were the adjectives associated with so many of the

riviste that chose to oppose Fascism. Ferrieri did not originally conceive of this so-called

forma antologica as a tool for political or cultural resistance.

Il convegno began more simply as an expression of its cosmopolitanism in the immediate postwar years before the Fascists were even in power. At the time, though, there was always the risk that by accommodating different writers and critics, old and new, with a mix of criticism, prose, and poetry,

Il convegno would be interpreted by supporters and detractors alike as lacking any clear direction. “Non avevamo nessun fatto personale contro la parola antologia,” Ferrieri explains in an unpublished introduction, “però successe, con l’andare del tempo, che questa definizione ‘antologia,’ che in fondo per noi era un pretesto per contrabbandare un preciso programma (come si vide nei fatti) e che non sceglieva nel vecchio, ma addirittura ne produceva del nuovo, ci fu affibbiato come un marchio d’infamia, da parte di quelle consorterie riunite dai loro interessi creati, per escluderci dai loro elenchi di candidati all posterità!” (We didn’t have anything personal against the word anthology, but it happened with the passage of time that this definition of “antologia,” which was basically a pretext for us to sneak in a specific program [as evident in the facts] and that was choosing not what was old, but was rather producing something new, and was attached to us like a mark of infamy, by those cliques held together by shared interests, in order to exclude us from their lists of candidates for posterity).

15 The inherent eclecticism of the anthology was eventually adapted as a sign of protest, and though it is certainly true that this form can be more local or regional, by bringing in foreign writers from abroad and providing the space for a new generation of Italian critics who could communicate with their European counterparts, Ferrieri was able to generate a cultural model for modern Italy that capitalized on the exchange in both directions into and out of Europe.

By 1926, when

Solaria first started appearing in Florence, Carocci had no illusions about what the form of the anthology meant. By this time, Gobetti was dead, Gramsci was in jail, and the struggle over the direction of Italian culture was very much under way. But instead of using the anthology as a vehicle for oblique political engagement (through editorials about literary figures and topics or through the choice of foreign writers and reviews), it was there to provide, as much as possible, an autonomous space in an increasingly politicized cultural sphere.

16 Critical essays and reviews appeared in its pages, among them Leo Ferrero’s provocative “Perche l’Italia abbia una letteratura europea,” but

Solaria (like

Il convegno) devoted itself primarily to bringing out works by modern Italian writers (Svevo, Montale, Saba) along with translations of American and Anglo-European modernists (Woolf, Hemingway, Faulkner, Joyce, Eliot, Proust, Rilke, Kafka, and Mann among them).

17 But

Solaria, a title inspired by Tommaso Campanella’s novel

La città del sole (1692) describing a utopian society, did not achieve its autonomy through content alone. It was transmitted through the form of the anthology itself, one that provided a panoramic view of the contemporary literary scene, bringing together collections of writers who were increasingly identified by their national affiliations. Up until 1936, when

Solaria was officially shut down, it never stopped reminding readers that being Italian did not have to mean severing European connections.

The decision to keep “un occhio all’estero” was a fraught one, indeed, but it influenced not just what would appear in riviste during the primo dopoguerra but also what forms they could take along the way. Instead of trying to follow the direction of every current or trace the configuration of every network, I limit myself in this chapter to one city (Milan), tracing the development of four riviste (Poesia, Il convegno, Pegaso, and Corrente di vita giovanile) over the course of thirty years. I chose Milan, in part, because of its geography. As an industrialized, metropolitan city positioned so close to the northern border, Milan was historically one of the primary sites for European cultural exchange in Italy. Not only was it widely considered Italy’s most modern city, which explains why it was the first home of the Futurists, but it was also one with the greatest concentration of wealth and cultural influence, second only to Rome, which was the seat of government and the Catholic Church.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Milan quickly evolved into a powerful publishing center, which allowed writers and intellectuals, many of them uninterested in the commercial literary marketplace, to track down printers who could publish their work cheaply. Milan, like Florence, Rome, and Turin during these years, was undergoing a series of seismic cultural and political transformations, and the

rivista was a barometer that effectively registered the shocks. When Marinetti founded

Poesia in 1905, Milan was as cosmopolitan as it ever had been, but when World War I erupted, Italy closed its borders. In the postwar years, the

rivista was effectively called on to access Europe, allowing for literary and critical conversations that could contribute to the formation of an Italian cultural scene on par with the capital cities of Paris, New York, and Berlin.

It wasn’t always easy being modern in Milan. Tracing a line of development within this city from F. T. Marinetti’s

Poesia (1905-1909) through Enzo Ferrieri’s

Il convegno (1920-1940) to Ugo Ojetti’s

Pan (1933-1935) and Ernesto Treccani’s

Corrente di vita giovanile (1938-1940), we can understand just how the

rivista was on the front line of this battle over the future of Italian culture. There are some revealing differences between them, but together they share in common a desire to transform an increasingly modern print medium into what Giuseppe Langella has called “un luogo di cultura” (a place of culture).

18 It was a “place” that was always taking Milan as a point of departure and deciding whether it would become a gateway into Europe or a gate that could keep Europe and the rest of the world out.

II

Milan and modernity went hand in hand. At the beginning of the twentieth century, it was one of Europe’s cultural capitals and a model for other, less industrialized Italian cities to follow. That’s what the Italian Futurists, of course, believed when they arrived en masse to stage their takeover of the city in 1909. They adopted Milan as a base of operations and depended on the sounds and sights of the crowds, trams, trains, electricity, and airplanes to jump-start an outmoded art and culture. In order to become a Futurist city, Milan could not remain isolated from metropolitan centers around the globe. Instead, it needed to act as “the puffing locomotive of the peninsula-train”

(la locomotiva sbuffante della penisola-treno), as the Futurist painter and sculptor Umberto Boccioni put it, one that could carry Italy to the rest of the world and back.

19Milan, as I already noted, did have a magazine culture in place long before the Futurists arrived to lead the peninsula-train out of the station, but its modern transformation in the first few decades of the twentieth century cannot be fully understood without taking a brief detour through fin-de-siècle Alexandria, Egypt, where Marinetti first learned how magazines could be printed, posted, and sent. At the time, poets in Alexandria were heavily influenced by French Symbolism and Decadentism, and if their eye was on the French capital, their hands were turning the pages of the French

revues to keep up with current trends. Born and raised in Alexandria, Marinetti was captivated by the modern literary experiments being conducted abroad, but instead of relying entirely on them for information, he did what any enterprising young writer with a budget might do: he founded his own French-language magazine in February 1894 and called it

Le papyrus (

figure 3.1).

3.1 Cover of Le papyrus (1894), first version. Permission to reprint from Oxford University Press.

Claudia Salaris argues that this early experience for Marinetti represented “the first step in a long initiation that would develop into futurism, the first symptom of a rupture with the present world”

(il primo passo di una lunga iniziazione destinata a sfociare nel futurismo, il primo sintomo di una rottura col mondo presente).20 Indeed,

Le papyrus, which belongs to the prehistory of Futurism, was instrumental in Marinetti’s development as a cultural mediator, giving the young editor-poet-publicist the chance to participate in an emerging international magazine network in and between France and Egypt. In its original incarnation,

Le papyrus was pretty conventional. Individual issues were printed on thin paper with block lettering on the cover (a different color for every issue), which contained information about subscriptions and the relevant editorial addresses along with a copyright notice protecting the rights of its contributors. No one knows for sure about the scope of

Le papyrus’s transnational distribution, but the line beneath the subscription rates indicates that some arrangement was made with French bookstores and, quite possibly, newsstands.

21 After the first six issues,

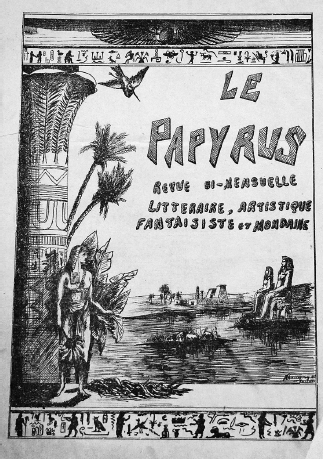

Le papyrus underwent a serious makeover: the format was enlarged so that it looked more like a newspaper than a periodical; it changed color, turning a washed-out clay red that remained consistent from issue to issue; a hastily drawn sketch of palm trees, seated pharaohs, and sand with a border of hieroglyphs was added to the cover; and all the editorial, copyright, and subscription information was placed inside (

figure 3.2).

These two covers reveal, among other things, a shift in tone. The sketch is more amateurish and looks as if it was dashed off in a hurry. But this transformation makes sense if you want to advertise the youthfulness of your magazine, which Marinetti, who was only eighteen years old at the time, did. Lest his readers miss the point, a new slogan was placed beneath the masthead: “Rédigeé par une société de jeunes-gens” (Directed by a group of young people). Le papyrus was not simply another revue in the French circuit: it was made by and for the “jeunes-gens” of Alexandria and provided the space where creative and critical work could be exchanged. Le papyrus was not to be confused with a museum that hangs up old masters on the wall. Rather, Marinetti and his collaborators imagined it more as a studio where poets could test their work on an audience while the paint was still drying.

Le papyrus in its original format could hardly be distinguished from the literary

revues published in Paris. In fact, anyone who came across it on a newsstand in Alexandria was likely to see

Le papyrus as a Parisian import. And that is precisely what makes the reformatting so significant: it signifies a break with the magazine model already in place, making it less derivative and, for that reason, more modern. But if

Le papyrus emerged as another satellite for channeling French literary culture, it soon began to identify itself with the local context and the historical conditions that set it apart. Reformatting, then, was a sophisticated maneuver that made Marinetti’s first magazine less of a colony in the French literary-critical circuit and more of an autonomous agent tied to an Egyptian culture that existed long before Napoleon’s arrival.

3.2 Cover of Le papyrus (Spring 1894), second version. Copyright © Artist Rights Society.

Le papyrus was Marinetti’s crash course in magazine production and distribution. Moving to Milan in 1902, he collaborated with

La plume, La revue blanche, La rénovation esthétique, La vogue, and

Verse et prose, working for one magazine as a foreign editor

(Anthologie revue). By 1904, however, he decided that it was time to put Italy on the map of modern literature and asked Carlo Linati to codirect the enterprise. The plan, Linati reflected later, did not make any sense: why would anyone publish “una rivista di poesia” at a time when the Italian literary field was becoming more and more commercialized?

22 It didn’t make any sense to him at the time, but Linati soon discovered that it was the adversity of the marketplace that spurred Marinetti on. He wasn’t interested in making a

rivista that reaffirmed current cultural trends. Quite the opposite: Marinetti wanted to change the direction entirely by showing a wide audience of readers just how modern and relevant poetry could be. The print run of the penultimate issue of thirty thousand and the final one of forty thousand clearly demonstrated his enormous success.

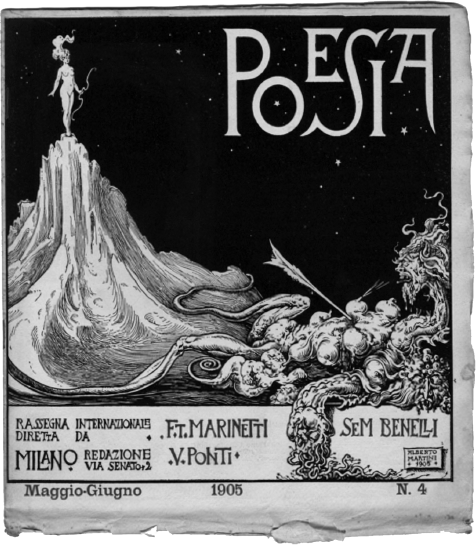

Marinetti christened his second magazine with the most generic title of all:

Poesia.23 That, of course, was the trick. Provocation was slyly concealed beneath a generic signifier. Marinetti’s

Poesia (thirty-one issues in all) was designed to promote modern poetry from dozens of countries, and yet, instead of arguing for the autonomy of the literary field, he employed many of the editorial and marketing strategies that belonged to the mass marketplace. Contests were staged asking readers to participate, free copies of individual issues were sent to entice bookshops and newsstands, and letters of praise from well-known writers and critics were frequently reproduced in excerpted form. Marinetti’s most inventive promotional scheme involved the

panettone, a popular Milanese sweet bread loaf, wrapped in a cover from

Poesia that would be sent as a token of appreciation to esteemed contributors.

Poesia, in other words, was not going to remove serious literature from the commercial sphere. Rather, it was going to plow right through it and wake up anyone who might think that poetry should be detached from mass culture. Marinetti knew that it was a “crazy act”

(gesto da pazzi), but he still firmly believed that

Poesia could “surprise”

(epater) Italy “barbogia and carducciana.”

24 His ambitions, in fact, went far beyond modernizing Italy and the Italians. “Marinetti,” as Paolo Buzzi remembered, “wanted to found a review capable of including the newest products from all modern poets in all the languages of humanity” (

volle fondare una rassegna destinata ad accogliere il prodotto nuovissimo di tutti i poeti moderni in tutti gli idiomi dell umanità).25 More than one reviewer was struck by the irony that the editorial offices, typesetters, and printers were based in and around Milan, “the most apoetic city in Italy”

(la più apoetica d’Italia) but one capable of providing “the machines, the industry, and the traffic”

(delle macchine, delle industrie, e dei traffic).26Poesia was an unexpected triumph. In the global history of the modernist magazine, it occupies a distinguished position not only because it eventually became an important platform for the foundation of Futurism (publishing the Italian translation of the first manifesto in 1909 and adding the words “Il Futurismo” to the bottom of the cover in the last few issues) but also because it revolutionized the medium itself and served as a powerful example of how a more global form of literary transmission could work in the first half of the twentieth century. And it’s worth remembering that when Marinetti founded Poesia, he was still regarded as a foreign transplant in Italy, a doubly displaced expatriate, who arrived in Milan from Alexandria speaking and writing in French. Indeed, some people have even suggested that his naïve distance from the realities of post-Risorgimento Italy, fueled by his deracinated identity, actually gave him the necessary detachment to embark on such a bold venture.

Poesia’s internationalism, though modeled after the French Symbolists of the 1890s, was much wider in scope and extended to dozens of countries in western, central, and eastern Europe, South Asia, and into South America. From the first issue in 1905,

Poesia advertised itself as a “rassegna internazionale” (international review), a qualifying term that referred as much to the contents of each issue as it did to its zones of distribution (

figure 3.3). In the opening pages, readers would regularly come across snippets from enthusiastic reviews and private letters, which proved, in every case, that

Poesia (and by extension Marinetti) was attracting admirers as far afield as Cairo, Berlin, Buenos Aires, and London. This self-promotion was certainly a way to attract new readers, and it was based on a simple strategy for making the internationalism concrete, flaunting the modernity of Marinetti’s enterprise precisely by advertising an expansive geographical terrain. Marinetti developed other tactics as well. He frequently announced a new “inquest”

(inchiesta) on topics as varied as the beauty of Italian women, free verse, and the search for an unpublished Italian novel. The number of responses always exceeded the available space in the magazine, so the list of respondents, many of them famous writers, artists, and critics, was regularly printed alongside carefully chosen excerpts.

3.3 Cover of Poesia 2 (May-June 1905). Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Permission to reprint from Oxford University Press.

Because of Marinetti’s earlier experience with

Le papyrus, he understood how magazines could generate a community of like-minded readers at home and abroad. What made

Poesia different from its predecessor, however, was the scale. The production was much larger, the audience more widely dispersed; it was importing poets as much as it was exporting them and establishing points of contact with writers and critics interested in “making it new.” The global ambition of

Poesia, then, was not dependent on a pass-along readership, as was the case for so many other magazines. Issues, of course, would move through informal networks, but Marinetti was beginning to experiment with what Salaris has termed a finely tuned “communication system”

(una sistema di comunicazione).27First, to distribute a large number of magazines, they need to be beautiful objects. Marinetti spared no expense in the production of Poesia, helped from 1907 by money inherited from his father. Every issue was printed on thick, uncut paper with a stunning cover designed by Alberto Martini that changed color every month. The high-quality paper, the modern design of the poetic muse on the jagged rock, and the brilliant colors increased the production costs, but they also alerted reader-consumers to the fact that they were making a worthwhile investment. The magazine they were buying was as beautiful and well made as any modern book, and with Marinetti supplementing the production costs, issues could be had for a reasonable price: one lira per issue within Italy, one lira fifty abroad. Poesia, then, was unlike anything else on the newsstands and in the bookshops. In fact, in an age of mass-produced magazines intended for quick consumption, it was an oddity of sorts: an anthology of contemporary world poetry meant to be preserved on shelves and saved for the future.

Second, a magazine worth buying and selling requires distribution sites. On this point, Marinetti was a visionary. Even before the official launch of

Poesia, he assembled a list of bookshops within Italy and abroad willing to receive issues on the twentieth of every month. Instead of keeping this information off the record, however, Marinetti included it as promotional material. Every issue, then, contained “un elenco delle librerie” (a directory of bookstores) on the back inside cover, with the Italian cities assembled alphabetically in a box at the top and the non-Italian cities below. It was also during Marinetti’s tenure as editor of

Poesia that he recognized how effective free copies could be for enticing distribution sites and potential contributors, and it was a ploy he continued to rely on after establishing a separate publishing house (Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia) for the production of high-quality books.

28Third, alliances are a must. For this, Marinetti adapted a strategy that magazine editors had long relied on; he published an inventory of like-minded reviews on the back page, broken down not by field or genre but by city. Looking closely, however, it’s clear that even here, Marinetti was modifying conventions. To the two dozen or so French magazines, most of them with Symbolist associations, has been added a small collection that includes Moscow, Bruges, Madrid, and Budapest. Whatever the location, the titles are all in French, with the implication that if this is the lingua franca of modern poets and poetry its lexicon, then the magazine is its voice box. The list of reviews on its own would not actually do much. But combined with all the other details, it demonstrated how internationalism was actively inscribed within the pages of

Poesia itself. The lists, inventories, and snippets of letters and reviews functioned like passport stamps that readers could show off whenever they wanted to advertise their own literary worldliness. And, indeed, that’s what Marinetti would do himself whenever he had the chance to write the words “la mia rivista internazionale

Poesia” (my international review

Poesia).29By the time

Poesia reached its fifth year, Marinetti was ready to move on. Though his audience had grown accustomed to surprises, the most pivotal one arrived in the first issue of 1909. Here, the manifesto of Futurism, which originally appeared in

Le Figaro, was published in French and Italian, signaling a dramatic change in direction. Once the home for modern world poetry,

Poesia was making space for manifestoes and an Italian literary movement. By the final two issues published that year, “Organe de Futurisme” (Organ of Futurism) appeared below the title on the cover page, marking the end of

Poesia and the beginning of Marinetti’s lifelong role as Futurism’s ringleader. What may have begun as a “gesto da pazzi” ended as a wild success story involving an editor who managed to transform Milan, and by default Italy, into an international hub for modern literature. It put Marinetti on the radar of many poets, critics, and writers, allowing him, in the process, to assemble faithful allies for the global reception of Futurism.

If Futurism grew out of

Poesia, it also outgrew

Poesia. By 1909, Marinetti was taking his literary and editorial experiments in other directions, and just as it was inconceivable that a single genre should be privileged, so too was it inconceivable that a single

rivista could carry the burden. Throughout the 1910s, Marinetti turned his attention to book publishing, the promotion of Futurism, and the Italian war effort, though he continued to edit from afar, mostly by working through other editors. When

Poesia was resuscitated in April 1920, lasting five issues until the end of that year, the young and energetic Mario Dessy stepped in as the editor. Marinetti, of course, sanctioned (and funded) the entire venture in the hope that it could help jump-start Futurism at a time when Italy seemed lost. Futurists would continue to find a home here, but Dessy also opened up the pages of

Poesia to developments in world poetry beyond Marinetti’s usual orbit and actively sought to engage with other avant-garde movements, including Dadaism, Ultraism, and “l’espirit nouveau.”

30Under Dessy,

Poesia experienced an intense, albeit brief, second life. Salaris suspects that its closure in 1920 had to do with divisions between the various factions within the Futurist party itself. The glory days of the first phase were officially over, and no one was sure what place Futurism or modern art in general would have in postwar Italy. But it’s also crucial to recognize that Marinetti did something that ran contrary to his own Futurist beliefs: he looked backward. Already by 1909,

Poesia belonged to a different age, a pre-Futurist moment when Marinetti was still figuring out how to internationalize modern poetry. He continued to assemble followers in the 1920s, but a new generation raised on the avant-garde militarism of the 1910s was looking for something different, and it was not going to be found in a

rivista from the past no matter how successful or modern it might have been.

III

In May 1923, Marinetti delivered a series of three lectures at the “Circolo del Convegno” on modern French poets. This particular event, sponsored by

Il convegno, a

rivista for contemporary literature and criticism based in Milan, was not as unusual as it might at first seem. Marinetti still lived in his adopted Italian city, not far from the “Circolo del Convegno,” and he had just completed an Italian translation of Mallarmé. He arrived, in this instance, not as a Futurist or a Fascist (or both) but as a poetry lover, one willing to entertain an audience of nonspecialists, the kind of general readers who were rapidly emerging in cities like Milan in these postwar years.

31 And that, indeed, was the purpose for such an event: not a political rally or a bombastic performance but a lecture about literature to an audience largely unfamiliar with the material. The “Circolo” was founded a year earlier to provide a forum for discussions about art, literature, and music, many of them ending up in printed form as articles, making it possible for others who were not there to follow along. In this way,

Il convegno was unique. At a time of dramatic political, social, and cultural upheaval in Milan (and across Italy), it was transformed into a cultural center complete with a library and bookshop (1921), a publishing house (1921), a lecture hall (1922), and a theater (1924).

Enzo Ferrieri, the thirty-year-old editor, first started

Il convegno in 1920 to combat the widespread Milanese ignorance about literary developments abroad. In his mind, he was continuing a process that began before World War I with the founding of

La voce and

Lacerba, both based in Florence, and in the postwar years, his

rivista became part of an interurban network that included

La ronda (1919-1923),

Il Baretti (1924-1928), and

Solaria (1926-1934). All of these magazines had different agendas, but together they shared the belief that Italian culture could be rebuilt only by establishing contact with writers from Europe and elsewhere. Ferrieri was lucky, then, to have an older guide like Linati by his side, someone who was not only more experienced with Italian

riviste (collaborating, most notably, with

La voce, La Diana [published in Naples between 1915 and 1917], and

La ronda) but also better connected to Italian and European writers, critics, and their magazines. By 1920, Linati had translated William Butler Yeats and John Millington Synge into Italian, begun collaborating with James Joyce on a translation of

Exiles, and received a commission from Ezra Pound to write a few letters about Italian literature for the

Dial. Not long after the first issue was published, Linati advised Ferrieri against a strictly regional focus and, inadvertently, ensured a longevity and internationalism that was matched only by Alberto Carocci’s

Solaria in Florence six years later.

Linati, who by this time would have realized how misguided he had been about Marinetti’s “gesto da pazzi,” provided Ferrieri with a simple formula for success: “continue to do your Review with the best Italian and foreign names; that is the best way to do it and the public will desire nothing better.”

32 Il convegno would not become the foundation for an exclusive literary or artistic movement or program. Rather, it would provide for an open and ongoing literary conversation that included criticism, translations, essays, and reviews from an international ensemble of critics and writers. The title, in place from the very beginning, was entirely appropriate for defining the mission at hand.

Il convegno would be the place for the informal rendezvous, one where texts, critics, and writers could be thrown together in unexpected ways from issue to issue: Franz Kafka to Isaac Babel, D. H. Lawrence to Umberto Saba, Luigi Pirandello to Marcel Proust, Rainer Maria Rilke to Anna Akhmatova, Albert Thibaudet to Carlo Carrà.

Il convegno avoided any dogmatic editorial program, searching only for examples of modern literature wherever they could be found.

33The original cover (February 1920), designed by the architect and graphic designer Giò Ponti, had the title stamped in large red block letters at the top with a summary of the contents, the name of the editor, the editorial address, and the price listed at the bottom. The industrial typeface and minimalist layout certainly signified the modern turn

Il convegno was taking, but together they conveyed a timelessness meant to assure readers that these writers, many of them unknown in Italy at the time, belonged to an emerging pantheon of world writers in the process of making literary history. There was another message encoded in this new cover design, one that most readers would have recognized immediately. It was modeled after the

Nouvelle revue française (NRF), the celebrated French review then under the editorship of Jacques Rivière, later Jean Paulhan. If ever there was a cosmopolitan magazine, the

NRF was it, and in Italy, every writer, critic, and translator with the slightest interest in contemporary literature followed each issue.

34 This was the place where the “consecration” of modern writers was happening in the 1920s, and any positive attention from the

NRF was enough to launch an international career.

35 Il convegno’s identification with the

NRF, however, went far beyond the cover design. Throughout the 1920s especially, the two magazines swapped critics, exchanged advertisements, moved writers between Milan and Paris, published essays simultaneously, and swapped books for review.

36 There were Italian critics at the time who interpreted this exchange as another symptom of Milan’s long-standing Francophilia, but Ferrieri saw things differently. Both magazines in these postwar years were developing strategies for cultural renewal dependent on the construction of collaborative networks that would allow nations to communicate with one another. And they both had something to gain: the

NRF picked up a sympathetic Italian ally, while

Il convegno earned cultural prestige.

Il convegno’s distance from Fascism’s cultural and political program could have been interpreted as flagrant dissent, and yet throughout the 1920s, it was not. Even the “Circolo del Convegno” managed to avoid paying the obligatory subscription to the “circolo fascista di cultura,” and the many public events, which included musical performances by Sergei Prokofiev and Béla Bartók, never attracted negative attention, though it would for other

riviste after 1937 when the Fascists issued their “Manifesto della Razza” (Manifesto of Race). Whatever noble intentions Ferrieri had from the beginning, he still needed to solve some very basic problems. How, for instance, do you open up your

rivista to Europe and the world? How much translation would be involved and in what languages? What standards are in place to measure the quality of a particular literary work? What makes a literary work translatable from one national culture to another? And who decides what gets in and what stays out? The last question, the most pressing of all in the process of literary transmission, allows us to work backward through all of the others: who decides what to import and export? In the case of

Il convegno, it was less a single personality than a collective body of critics, translators, and writers with different specializations. Stationed at the borders between Italy and the rest of Europe was a team of mediators charged with finding original literary works to translate, books to review, foreign magazines to set up exchanges, and critics—all of them well known—ready to chart developments in their respective national literatures. Giacomo Prampolini was put in charge of German, Scandinavian, and Slavic literature, Giuseppe Prezzolini (and later Eugenio Montale) the French, Eugenio Levi and Cesare Angelini the Italian, and Linati (later Emilio Cecchi) the American and British.

Linati was a reliable ally from the beginning to the end of Il convegno’s reign. In fact, he agreed to break with the Rome-based La ronda in order to offer his services exclusively to Il convegno for 350 lire per month. Because of his connections with Pound and Joyce, he was put in charge of British, Irish, and American literature. As much as mediators like Linati were working behind the scenes to assemble material for future issues, they were also required to be on-site for readers in need of guidance, who were attending the lectures of the “Circolo” and visiting the library with an impressive collection of over one hundred literary magazines from Italy and abroad. That contact between mediators and the reading public helped to establish an intimate bond with the rivista itself. They were, in a sense, a physical link between Italy and the world outside, specialists with a secret knowledge that they were willing to share with others.

Mediating the literary field in real time can be a lot like gambling: betting on a future that may or may not bring rewards. In some cases, the odds were not very formidable, especially when a writer already had an established reputation. Bringing Dostoevsky, for instance, into Italy in 1925 was less about gauging his greatness than about announcing his existence to a wider audience. There were also the search and rescue efforts of magazines across western Europe, many of them crafting the posthumous reputations of writers like Franz Kafka, Isaac Babel, and Rainier Maria Rilke. Italo Svevo was a unique case because he was an Italian writer “discovered” by the French before being imported back into Italy, in large part because of Eugenio Montale’s enthusiastic review of

Senilità in

L’esame (1925).

Il convegno was one of the first

riviste to lend its support to Svevo’s cause, including critical essays on his novels, invited talks, and after his death, an entire special issue assembling personal memories and critical evaluations from leading French and Italian critics. Proust, Joyce, and Thomas Mann were regular fixtures in these pages, for instance, but there is a conspicuous absence of avant-garde writers and movements. Considering that 40 percent of the articles, reviews, and translations involved foreign writers,

37 it is easy to see how some contemporary Italian critics would complain of an unapologetic Eurocentrism. Striking a balance between foreign and domestic literature is always a tricky process, and it involves, as Paul Valéry put it in a letter to Ferrieri, “the most delicate balance between tradition and invention. To grow without shrinking” (

un delicatissimo equilibrio della tradizione e della invenzione. Crescere senza diminuire).38 In the case of

Il convegno, importing was a strategy for modernizing Italian literature. Instead of devaluing Italian writers and critics, this foreign presence had just the opposite effect, and in the process of expanding the frame of reference,

Il convegno was not only educating a small reading public but also making it possible to imagine where Italian writers would fit into a much wider cultural universe.

Though Ferrieri repeatedly advertised

Il convegno as a vehicle for exporting Italian literature, there is little evidence of any significant international distribution.

39 It was more active as an importer of mostly European literature, a window into a world “beyond Chiasso”

(oltre chiasso), the border crossing between Italy and Switzerland. The distinction, in fact, is crucial, because it forces us to think about the politics of “literary exchange” within Milan during these years. Whatever the global ambitions of a

rivista like

Il convegno, it was not entirely democratic. It had to choose which currents to follow, creating networks of circulation that privileged some regions over others. And no matter how prescient the mediators were in this process, they were never acting alone. Their decisions were based on the judgment of critics from the respective nations of the writers in question. Cases like Svevo were extremely rare. It was more common to find writers in

Il convegno with preestablished national reputations, many of them receiving an added boost from the French critical circuit.

Il convegno wanted to access a wider literary system in the wake of a world war, but this meant that writers and critics were selected on the basis of universal moral and intellectual values. Indeed, specific national and regional contexts and literary traditions were acknowledged but only insofar as they contributed to the idea of a Universal Europe that was itself just as ideological. Throughout the 1920s, Il convegno was one of a handful of Italian riviste manufacturing the figure of the modern European writer, someone opposed to nation-based provincialism and open to modes of literary communication that emphasized cross-cultural, transhistorical connections. James Joyce was an ideal example of this enlightened European figure. He was first introduced to Il convegno’s readers through Linati’s Italian translation of Exiles in 1920. Linati considered an Italian translation of Ulysses, but with an authoritative French version on the horizon (complete with Joyce’s imprimatur), he decided against it. Instead, he agreed to translate a series of six excerpts from Ulysses, all of them selected by Ezra Pound and presented in a single issue under the title “Da l’Ulysses di James Joyce.” When making the case to Ferrieri, Linati explained that a special issue could be a publishing event for Il convegno. Best of all, Joyce was a writer Il convegno gambled on long before he had international celebrity status—a triumph sporadically reported on the inside cover.

Il convegno, then, was worldly by association. And embracing Joyce ended up validating a program of “deprovincialization” that was in place from the very beginning. In the first half of the 1930s, sporadic efforts were made to establish contact with other national literatures—Russian, Scandinavian, and Icelandic among them—but Ferrieri, like so many others, began to turn his attention to film and radio. In 1931,

Il convegno sponsored a conference that asked writers and critics to consider the impact of radio on mass culture. It published the findings in a special issue and two years later began a supplement,

Cine-convegno, devoted entirely to film criticism (it lasted only a year). This focus on new media was generated, in part, by genuine curiosity, but considering Ferrieri’s editorial prowess, it was also his way of accommodating the political restrictions that were shrinking the literary field. Once double and triple issues began appearing in 1933, the death rattle of

Il convegno was officially under way.

40 Though a new generation of Italian writers started to appear in these pages—Guido Piovene, Leonardo Borgese, Mario Robertazzi—there were not enough of them, and the imported material became so sparse that twelve issues a year at sixty pages each were too many to fill.

41 Ferrieri, however, refused to let his magazine become part of the Fascist propaganda machine or dwindle into obsolescence. But even if the contents took a decidedly muted, Italocentric turn, Ferrieri saved his most overt political message for 1936, when he published

Il convegno as a bimonthly with a white cover designed by Leonardo Borgese, one of several anti-Fascist Jewish contributors who had the greatest difficulty with the censors.

The whiteness of the cover symbolized opposition to the

camicie nere, or black shirts, the militant branch of Mussolini’s Fascist Party. The red letters were replaced by smaller black ones (offset to the right); the summary of the contents and office address were removed; and the date, once indicated by month and year on the top left-hand side of the cover (January 1921), was replaced by Roman numerals. That last detail, like the color, was another anti-Fascist jab. The practice of marking the passing year with Roman numerals was adopted for the new Fascist calendar, beginning with October 1922 to mark Mussolini’s March on Rome. At first, Borghese kept the Fascist year off (and the year of

Il convegno on), but when it was added, careful readers would discover that the calculation on the cover corresponded not with Mussolini’s rise to power but with the appearance of

Il convegno’s first issue.

42 The correct Fascist date was, however, placed on the inside cover page as protection against attentive censors.

In the editorial note, Ferrieri explained that the color change reflected a new

realtà across Italy, one he refused to define, choosing instead to revisit the original objectives outlined sixteen years earlier.

“Il convegno,” he said, “does not follow any fashion”; its lasting ambition had been “the will to understand, to stimulate interest in moral, literary, and artistic problems and distribute this awareness to a relatively large public. This is the reason that has kept

Il convegno, after seventeen years of life, without contradictions, one of the youngest Italian reviews.”

43 In 1936, readers would have been acutely aware that Ferrieri was describing a world that no longer existed, one where writers spoke the same language, making it possible to “have a conversation”

(dare convegno) in the pages of a single

rivista. In fact, by the time this note was written, the Fascist censors had already begun to cut, modify, and on one occasion, seize individual issues of

Il convegno—bringing the autonomy of the 1920s to an abrupt end.

The cover, which Ferrieri described as “white like a dove”

(candida come colomba) could mean a lot of things: the nostalgia for cultural autonomy, the desire for oblivion, or an expression of political resistance. But in this instance, it also could, like the white flag, be taken as a sign of surrender. Issues continued to come out sporadically until January 1939, but like so many other intellectuals across Italy, Ferrieri realized he was fighting against a totalitarian regime that was becoming only more powerful over time. In the final issue, there was no formal farewell, which suggested that the entire operation was shut down rather abruptly.

44 As Ferrieri looked back on his experience, he reaffirmed his belief that

Il convegno helped protect Italy from “the total enslavement, from superficiality, and from cultural ignorance”

(totale asservimento, dalla superficialità e dall’ incultura) of Fascism.

45 Maybe that wasn’t enough to alter the course of history, but at a time when the horizon looked bleak,

Il convegno provided a peek across the Alps just before Europe became, once again, a battlefield.

IV

If Marinetti wanted to make Milan the literary capital of the twentieth century, Ferrieri was happy enough to fashion it as a port of call for literary travelers. But in the late 1920s and early 1930s especially, Fascism was changing the rules for cultural production, and the repressive laws against print publications began to influence everything from their content to their design and layout.

46 Ferrieri made the most of an increasingly dire situation, refusing to close down, but even he knew that the original plan to deprovincialize Italy through alliances with the United States, western Europe, central Europe, and Scandinavia was breaking down. From 1933 onward, there was a dramatic drop in the number of foreign writers published in the pages of

Il convegno, and it was accompanied immediately by a complete break with the magazine exchanges it once depended on for its perspective on the contemporary scene.

While

Il convegno was lamenting its decline, there were other

riviste in Milan that actually thrived in such a repressive environment. Ojetti’s

Pan (1933-1935, twenty-five issues) was one of them.

47 Like

Pègaso, which he coedited in Florence between 1929 and 1933,

Pan was a general literature and culture magazine that set out to define

Italianità, an Italian identity, by bringing a classical past in line with the ideology of a modern, Fascist present. Unlike Ferrieri, Ojetti was a Fascist supporter, though, with the exception of a few direct references to current events and one article devoted explicitly to Mussolini (“Scritti e discorsi di Benito Mussolini”; Writings and speeches of Benito Mussolini), he tended to avoid direct political discussion. Instead,

Pan was devoted to a form of Fascist cultural renewal, looking back to Italy’s glorious past in order to imagine the future.

At 160 pages a month,

Pan looked more like an academic quarterly from the previous century than a contemporary review.

48 But it was also true that Ojetti’s latest venture, published by Rizzoli, was motivated by the commercial desire to assemble an audience of general readers ready to consume Italian culture. For this reason,

Pan, in spite of its rather staid appearance, had more in common with the glossy magazines of the 1930s than with the smaller and edgier reviews, which had all but disappeared. Its ideal reader was someone who might enjoy

Lei (a woman’s illustrated weekly),

Piccola (a weekly with short stories), or

Il secolo illustrato (a photography magazine)—all of them owned by Rizzoli—and the advertisements at the back covered everything from tourist bureaus and newly printed editions of the classics to the latest Fiat.

Even with this commercial apparatus built into

Pan’s pages, it was designed to resemble an academic periodical (

figure 3.4). On a yellow back-ground, the title was written in oversized letters with an image of the Greek god, holding a pipe in one hand and a doting

putto in the other. Ojetti’s name is inscribed below in large type, followed by the name and location of the publishing house, “Rizzoli e C.” The layout of the cover suggests that the identity of

Pan was very much tied up with the personality of its editor, who was well known in Italy as a journalist, art critic, and novelist. Whereas Ferrieri had a team of mediators to assemble each issue, Ojetti had Giuseppe de Robertis, an established literary critic based in Florence who directed

La voce between 1914 and 1916.

3.4 Cover of Pan 2, no. 1 (January 1934). Courtesy of the New York Public Library. Permission to reprint from Oxford University Press.

For Ojetti and de Robertis, the Fascist culture they were helping to shape did not depend on chaos, violence, and revolution, and there was no need to look beyond Italy for guidance. Instead, the newness of Fascist culture, what Ojetti called

novità, could be generated through a contemporary critical engagement with art, literature, and music. In his one and only editorial for

Pan, Ojetti wrote, “Therefore, this will be a

rivista of the humanities and culture…. This consensus we intend to obtain by continuing here with dignity the most useful [usati] studies of history, art, criticism, other ideas, and trying to bring clarity, order, and Italian honesty in every area of original intelligence.”

49 A note of this sort makes it sound as if the

Pan of 1933 had a lot in common with

Il convegno: two Milan-based magazines with an eye on Europe and dreams of creating a modern Italian culture. They did not, however, mostly because

Pan and

Il convegno had very different ideas about Italy’s future: the one looking back on the cultural achievements of a narrowly defined Italian past to shape the present, the other looking outside Italy to imagine a modern culture that could be Italian

and European.

Instead of establishing lines of communication between Italy and the rest of the world, this critical work helped to reinforce an Italian exceptionalism being articulated at the same time by the PNF. Italy, in other words, was a modern nation whose greatness could be traced back to its glorious past as an empire and cradle of civilization. The editorial offices of Pan, then, may have been based in Milan, but the rules for any exchange in Italia, all’estero had changed dramatically since the immediate postwar years. Establishing global literary and critical circulation was less necessary than generating a form of cultural self-sufficiency.

News about foreign literature and culture trickled in, some of it in the form of book reviews, some as a stray advertisement from a foreign publisher. Most of it, however, could be found in “Notizie” (Notices), a section at the back of

Pan devoted entirely to gossip about everything from art exhibitions, book publications, and contests to actors and the film industry. Readers of the February 1934 issue, for instance, would have found out about the sculpture contest in Milan, the goings-on of Kurt Weill (who fled Germany for Paris), and the giant hand of King Kong. While it is tempting to see “Notizie” as Ojetti’s acknowledgment of a wider cultural world, it should not be confused with the kind of critical engagement found in the pages of

Il convegno or

Poesia. “Notizie” was not created to generate any substantial dialogue between nations or to hold Italy up for comparison. Instead, it was a place where readers could consume bits of book-related information quickly. But this increased exclusivity was also fueled by the financial dependence of

Pan on Rizzoli, a commercial publishing house eager to entice reader-consumers to buy from its catalogue. Unlike so many other Italian

riviste that founded publishing houses to print books that would not otherwise see the light of day

(Poesia and

Il convegno among them), this process worked in reverse: Rizzoli published

Pan to steer its literary-minded readers toward “I Rizzoli Classici,” high-quality, reasonably priced copies of the classics edited by none other than Ojetti himself.

The last issue of

Pan was published in December 1935 without any farewell. Readers, however, might have had some premonition of what was to come when they stumbled across this note in the October issue: “In adherence to the orders of the Ministry of Print and Propaganda, from this month onward

Pan will be published in reduced format by a quarter”

(In ottemperanza alle disposizioni del Ministero della Stampa e Propaganda, da questo mese “Pan” esce in fascicoli ridotti di un quarto).50 Far from being a punishment, this “reduction” was a chance for

Pan to support the Fascist cause just at the moment when the Italians were invading Ethiopia. The Italian propaganda machine needed paper, among other things, for spreading its message both within Italy and abroad. It was the current political climate, no doubt, that influenced Ojetti’s decision to close down

Pan for good. Maybe his decision had something to do with the new paper restrictions, but I suspect that it was also motivated by the realization that the Fascists were entering their imperial phase, and the cultural machine would have to adapt accordingly.

Pan was noticeably thinner in the final issues, with the most conspicuous reduction made to “Notizie,” where the usual eight categories were cut down, without any editorial comment, to three.

V

“This newspaper was born two years or so ago to fill a lack: that of not having in Milan a place for new cultural activity to converge”

(Questo foglio è nato due anni or sono per colmare una mancanza: quella di non avere a Milano ove convergere le nuove attività culturali).51 This is the kind of generic editorial announcement found in any

rivista that looks back on its own beginning. There is an absence in the cultural field that only this particular medium can fill. But in 1939, when this line appeared on the front page of

Vita giovanile (later changed to

Corrente di vita giovanile and then to

Corrente with the

vita giovanile much reduced in size), Milan was flooded with cultural activity, much of it organized by the Fascist Ministry of Popular Culture, which had effectively taken control of the mass media since 1937. By the end of the 1930s, the

rivista was already an older technology in Italy, but it was being mobilized both by the Fascist government ready to enlist a new generation and by a young population that was disillusioned by its increasing intellectual isolation.

52Corrente was made by and for the youth of Italy.

53 “We maintain that our journal can give young people a place to test their strength, a springboard from which they can be better equipped to take a leap toward a particular reality, and not into the emptiness of illusions.”

54 It was a bimonthly (fifty-three issues) with a national readership of five thousand, and its founding editor, Ernesto Treccani, who was eighteen years old when it began (like Marinetti with

Le papyrus), helped to transform

Corrente into a lively intellectual forum where competing ideologies and personalities could battle it out. The first page was reserved for Italian political life, but the subjects that followed ranged everywhere from urbanism and the economy to film and figurative art. This interdisciplinary eclecticism was what made

Corrente so effective as a cultural force. Instead of separating art from politics, or from social life more generally, as so many other

riviste had done, it combined them, thereby allowing for a dialectical engagement that exposed the tensions, contradictions, and incompatibilities within Italian culture. Art (visual, plastic, literary) could not simply be judged in accordance with its adherence to the party line. In fact, it was often the case that the opposite effect was produced. The “subversive eclecticism”

(eclettismo presovversivo) of

Corrente, as Giansiro Ferrata called it years later,

55 challenged readers to think about the restrictive political logic that would, to take one example, try to ban the poems of Federico García Lorca.

Corrente was a strange hybrid in Milan. It looked like a newspaper (six oversized pages), but it read like an academic quarterly that combined literary analysis and poetry (in translation when necessary) with political, economic, and social critique. The newspaper format had associations with the more militant line of riviste that included Lacerba and Il Baretti, and the academic quarterly for general readers was very much linked with the postwar model established by La ronda, Il convegno, and Solaria. Treccani was not always sure himself what to call Corrente, referring to it on some occasions as a foglio (paper) and others as a giornale (newspaper), periodico (periodical), or rivista (review). The generic tag would change to accommodate whatever cultural function Corrente was serving at the time: on occasion, acting more like a newspaper issuing a call to action to a wide range of readers or, when necessary, encouraging the need for intellectual reflection from young and old alike. But the youthful exuberance, which combined a love of tradition and an embrace of foreign and domestic innovation, was really what made this entire enterprise reminiscent of Marinetti’s Poesia, a model for how the young and old in Italy could be mobilized around a rivista for a common cause.

Looking at the cover page of an early issue, with its six columns of newsprint, a quotation from Mussolini at the top (“We want our young people to pick up the torch” [

Noi vogliamo che i giovani raccolgano la nostra fiaccola]), and the title in bold letters superimposed on a red, green, and white banner, between two

fasci littori, the Fascist symbol, it’s tempting to conclude that

Corrente was just another cog in the propagandistic machine. And yet, once you learn that Mussolini closed down the offices of

Corrente in June 1940, you realize just how complicated the cultural politics of Fascism could be in these years. But instead of racing to

Corrente’s end, I want first to consider what made it such a lively intellectual space, one where Catholics, Socialists, and Communists could jockey for a few columns amid literary reviews, cultural essays, and poems from contemporary Italian and foreign authors.

56To get a sense of

Corrente’s complicated literary politics, it’s worth looking at a single quantitative statistic: in its two-and-a-half-year run, 9 percent of the literary essays were devoted exclusively to contemporary non-Italian writers, with another 6 percent of the overall content reserved for poetry translations. When combined, the “foreign” presence might not seem significant, but it is worth considering it in light of the political situation. Unlike

Il convegno, which did a bulk of its foreign importing in the 1920s,

Corrente was active at a time when the Ministry of Popular Culture, formally established a year earlier, was reaching its most repressive phase, and the “Manifesto of Race” made importing foreign writers, especially Jews and anti-Fascists, even more dangerous than ever before. And yet in spite of the repressive mechanisms the Fascists set in place,

Corrente continued to keep its eye on European literary developments, and instead of cutting down the number of foreign writers from year to year, it actually increased them, doubling the number of translated poems, for instance, between 1939 and 1940.

57Corrente managed to survive, in part, by adopting the Fascist codes of behavior, including, for a time at least, the ceremonial bow to Mussolini on the cover and the political articles on the first page. And some of it, especially in the first year or so, was genuine. But it didn’t take long for this “palestra di giovane” (gym for the young) to morph into a refuge for artists and intellectuals of all ages, many of them dissatisfied with the political direction of the Fascist Party, especially its increased antagonism toward foreign literature and art. This desire for ideological distance became visible on the cover when the

fasci littori were taken off the masthead (by March 31, 1938), followed shortly thereafter by the removal of Mussolini’s quotation (October 15, 1938). By March 1939, the subtitle,

vita giovanile, was shrunken down, becoming barely legible, and the title, now larger, took up the entire masthead (

figure 3.5). The design shifts on the cover were part of a more unified process:

Corrente was gradually composing a farewell to youth, refusing to pick up the Fascist Party’s torch or blindly carry out its ideological program.

58 And as this dissatisfaction grew, the political first page functioned more like a screen that could distract censors from the more subversive contents hidden inside.

59 This included articles about the Jewish composers Béla Bartók and Arnold Schoenberg (now banned by the Racial Laws in Italy); poems by García Lorca, Antonio Machado, Sergei Yesenin, and Paul Éluard (who participated in the Congress of Anti-Fascist writers in 1935); and editorials critical of the Premi Cremona, a Fascist-sponsored art exhibit, and the aggressive militarism of modern nations.

60 It was this final editorial by Carlo Cattaneo, appearing in the same issue as García Lorca’s “Oda a Salvator Dalí,” that earned

Corrente a note from

il duce himself: “Basta, ora basta!” (Enough, that’s enough!).

61 That same day, Italy declared war on England and France, and the closure of

Corrente, as with so many other

riviste across Italy, signaled a new phase in Fascism’s takeover of the cultural field. By this time, no one was surprised by the closure of

Corrente. The Fascists had been implementing restrictions on cultural production throughout the late 1930s, and the noose was only getting tighter, making it a matter of time before the floor was kicked out from below. The last issue appeared on May 31, 1940.

3.5 Cover of Il corrente di vita giovanile 2, no. 23 (December 31, 1939). Private collection.

That same year, Giuseppe Bottai, minister of education, launched

Primato in Rome as an attempt to unite Italian writers and intellectuals (including historians and philosophers) regardless of their political affiliations.

62 Bottai was still serving as coeditor of

La critica fascista, which he started in 1923, but with this particular title, he wanted to generate a more inclusive discussion about Fascist culture (still excluding Jews and women), one that would actively challenge the increased Nazi hegemony across Europe. In an effort to attract Linati to his cause, Bottai, in fact, explained that

Primato “intende riunire tutte le forze vive e operanti della cultura italiana, offrendo quindicinalmente a un largo pubblico un quadro armonico di tutte le attività intelletuali,

in Italia e all’ estero” (wants to reunite all the living and active forces of Italian culture, giving every other week to a large public a harmonious picture of all the intellectual activities, in Italy and abroad).

63 By this point in time, Linati would have known that this definition of a “cultura italiana” worked by exclusion, so that even the promise of a look “all’estero” would come with serious restrictions. And even if a few lively debates unfolded in the pages of

Primato, Luisa Mangoni has pointed out that they were all adapted to fit the restrictive ideological framework provided by the anonymous editorials. In this sense, she explains,

Primato was caught between “un vecchio modo di fare riviste letterarie” (an old way of making literary

riviste) and “una nuova realtà” (a new reality), one that put all culture in the service of politics.

64 Like Linati, Ferrieri was never convinced by Bottai’s promise of a “liberal” Fascist culture. And having lived in Milan during these tumultuous decades, he came to believe that it was precisely by keeping his eye abroad that he was able to survive: “L’importante era di uscire dalle clausure fasciste,” he later reflected, “dimenticare un falso stile d’accatto, sempre più lontano dalla realtà e incompatibile con la nostra formazione, riprendere antiche consuetudini, amicizie interrotte, ravvivare curiosità insoddisfatte, ridare vigoria a tante domande, alle quali, l’Europa aveva, fin da quando avevamo imparato a leggere, risposto” (It was important to get out of the Fascist stranglehold, to forget a false borrowed style, always more and more distant from reality and incompatible with our plan, to recover old customs, interrupted friendships, to revive unsatisfied curiosities, to reinvigorate so many questions, to which Europe had been answering ever since we had learned to read).

65The world had changed since Marinetti’s arrival in Milan. What is so compelling about the

rivista in these decades, and in this city, was its stubborn resilience and its capacity to respond to concrete conditions in the cultural field, sometimes in support of the dominant political machine and other times as a site of resistance. Indeed,

Poesia, Il convegno, Pan, and

Corrente provide different windows onto the intellectual life of Milan between 1905 and 1940, but reading them together allows us to understand the complex negotiations of an Italian literary field that was trying to reconcile the freedom of international exchange with the restrictions of national politics. The

rivista was a technology that promised to open the lines of communication between intellectuals isolated from one another, effectively shrinking real geographical distances and providing connections for cultural transmission that had never existed before on such a scale. When World War II erupted, Italy retreated into the hypernationalism and isolated regionalism that so many writers, critics, and readers had fought against for two decades. At least this time around, there was a model in place, and a medium, for a form of cultural renewal that could bring Italy back into Europe and the world beyond.